US Navy Submersibles, USS Mackerel, Marlin SS-198-211 (1939-48)

US Navy Submersibles, USS Mackerel, Marlin SS-198-211 (1939-48)WW2 US submarines:

O class | R class | S class | T class | Barracuda class | USS Argonaut | Narwhal class | USS Dolphin | Cachalot class | Porpoise class | Salmon class | Sargo class | Tambor class | Mackerel class | Gato class | Balao class | Tench classThe Mackerel-class submarines were two prototype submarines laid down before the war and launched in 1940-1941 on roughly similar designs. They were completely different from the US submarine trend and much smaller in size, envisioned as successors to the S-class submarines of late World War I. They had been ordered by Admiral Hart, in charge of the US sub force, as a reaction to large, costly fleet submarines and to test the feasibility of using mass production techniques to deliver small submarines for coastal defence, as were the S-class. Until 1940 it was thought that mass production of fleet submarines was impractical and only small submarines would be suited, providing in case of war, an area defense for submarine bases. But mass production of the standardized Gato-class soon proved these assumptions false and no mor of that types were ordered as they had little utility in the Pacific threater, as reflected by their unglamorous career. The Mackerels (“M class”) indeed operated in the Atlantic for training and research. On 12 April 1942 Mackerel counter-attacked and sunk an U-boat and they were decommissioned in November 1945.

Development

Admiral Hart’s Oddball

The immediate “succession” of the Tambor was the Gato class but in reality a competitor project was ordered for the Navy by the most vical opponents of the stretching of US subs, as they wanted a return to the coastal S-Boats for home defence only. These were the Mackerel class. These two small submarines were built largely at the instance of Admiral T.C.Hart, the General Board’s submarine expert, fearing these new ‘fleet boats’, were becoming too large, and who looked forward to replacements for the many ‘S’ class boats about to become over-age.

They were justified as ‘patrol’ or coast; defence units, but met very great resistance on the part of the submariners, who felt that a 1500-ton ‘fleet boat’ could do quite as much, but could also function in the all-important Western Pacific. Ultimately two boats were built under the FY39 programme, one (SS204) to an Electric Boat Company design, and the other to a Navy in-house design; after the war Electric Boat built six modified Mackerels for Peru, with ‘guppy’ sails and a deck gun. Mackerel had direct drive, Marlin diesel-electric through motor-generators. Designed depth was 250ft, and there were 6 TT and 12 torpedoes. Although the Board of Inspection and Survey was very favourably impressed with these small submarines, neither saw effective war service and both were discarded. The need which Hart forsaw for large numbers of boats to protect the Hawaiian Islands, the US coast and the Canal Zone never really materialised. Aftr Pearl Harbor the need for new large submarines to bring war to Japanese home waters overruled all previous considerations.

Design of the class

The Mackerels stemmed from design studies of the General Board going back to 1936 under Admiral Thomas C. Hart. Dubious of the cost and size of fleet subs he instead milited for a return to the late WWI mass-built S-class formula notably in case of wartime as it was believed fleet subs were ill-adapted for mass production, as well as to replaced the WWI era aging S, R, and O-class submarines which reached their service limit, and finally to defend local submarine bases, operate in coastal waters. Since that new class voted FY1939 was experimental, the Mackerel or “M” class led to the design of two two somewhat different designs produced respectively by the Electric Boat and Portsmouth NyD, the usual renown private pioneer of Groton, Connecticut, and the state-sponsored of Kittery, Maine. Both Mackerel and Marlin are placed in the same class for practicality but were near-sisters with significant design differences.

In propulsion, one of the main experimental stage at the time, Mackerel was given a direct drive propulsion arrangement while Marlin had direct a diesel-electric drive (for most sources). Mackerel use the usual Electric Boat diesel design and arrangement but Marlin used an ALCO locomotive design, which was pretty unique but well suited for mass production. They were completed in March and August 1941, performed battery of tests and trials, but already by the time, mass production of Gato class fleet subs was well underway and they appeared redundent.

That is until early 1942, interest was revived with the examination of the captured U-570 (a Type VII) captured by the British and loaned to the US for examination and evaluation. Admiral Hart, in charge of the US submarine fleet in the defence of the Philippines returned to the General Board in late 1942 and, constant in his beliefs, underlined that no other navy abandoned small submarines and pressed the board to resume work on an alternative type, at least for the Atlantic. However Admiral Frederick J. Horne, recently appointed as Vice Chief of Naval Operations stated that given the nees of the Pacific, production of nes smaller subs would be only authorized if they did not interfere with fleet submarine production. The concept returned to the drawing board and stayed there until postwar, when new small types influenced by the Type XXI design appeared, such as the Barracuda class in 1951, and again, with mass production in mind.

Hull and general design

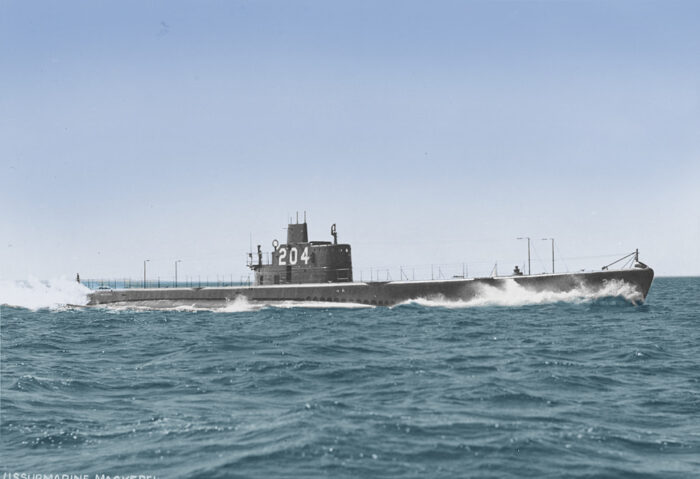

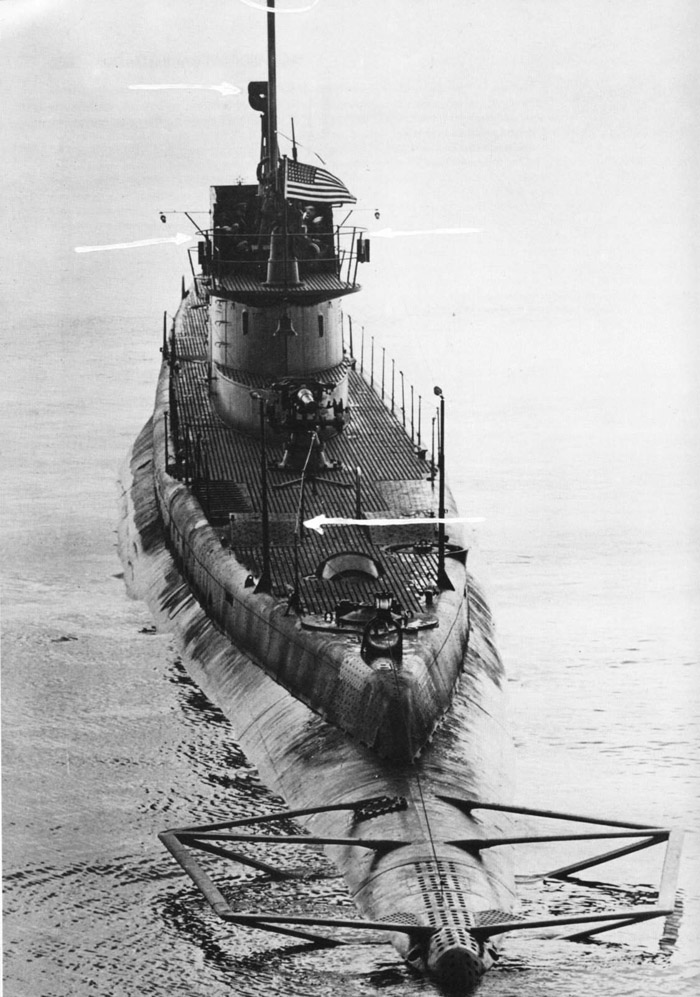

The USS Mackerel from Electric Boat displaced 825 tons (838 t) surfaced and 1,190 tons (1,209 t) submerged. She measured 243 ft 1 in (74.09 m) in overall lenght for a beam of 22 ft 1 in (6.73 m) and a draft of 13 ft 0+1⁄4 in (3.969 m). Her near-sister Marlin from Portsmouth was slighty smaller, displacing 800 tons (813 t) standard, surfaced and 1,165 tons (1184 t) submerged for an shorter overall length of 238 ft 11 in (72.82 m), but a slightly higher beam of 21 ft 7+1⁄4 in (6.585 m) but the same draft of 13 ft 0+1⁄4 in (3.969 m). She was supposed to be a bit more agile than fast so better suited for restricted waters.

Powerplant

Propulsion-wise, they differed a lot:

USS Mackerel was provided two Electric Boat direct drive diesel engines as main propulsion for surface action, 1,680 bhp (1,250 kW) in total and a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h). Underwater she was given two Electro Dynamic electric motors rated for 1,500 bhp (1,100 kW) for submerged action, with her underwater range by two 60-cell Sargo batteries, half the provision of a Sargo class. This enabled a still good underwater speed at 11 knots (20 km/h) for short runs. Trials shows she was capable of a range, surfaced, of 6,500 nautical miles (12,000 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h).

Her sister USS Marlin had two ALCO diesel engines driving electrical generators, so an indirect drive, producing a little more than EB’s Mackerel’s home diesels, at 1,700 bhp (1,300 kW) surfaced for 14.5 knots (27 km/h) so noticeably less than her sister. Submerged, she counted on two General Electric motors rated for 1,500 bhp (1,100 kW) for 9 knots (17 km/h) submerged and the same 60-cell Sargo batteries. Marlin had the better range of the two, measured as 7,400 nautical miles (13,700 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h).

Armament

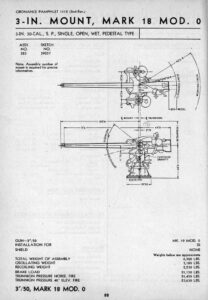

Both were armed as standar like S-class submarines, with a small 3-in/50 deck gun, two heavy machine guns for close AA defence and six torpedo tubes, four forward and two aft, like most European small submarines. This changed udring the war (see later).

3-inch/50-caliber gun Mk.21

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Mark 21 … Image: 3-in/50 Mark 18 specs and sheet, src HNSA via navweaps.

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Mark 21 … Image: 3-in/50 Mark 18 specs and sheet, src HNSA via navweaps.

⚙ specifications 3-in/50 Mark 18 |

|

| Weight | 6,500 Ibs |

| Barrel length | 120 inches |

| Elevation/Traverse | -15/+40 degrees |

| Loading system | Manual, vertical sliding wedge type breech |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,700 fps (823 mps) |

| Range | 14,000 yards (12,802 m) at 33° |

| Guidance | Optical |

| Crew | 6 |

| Round | 24 lbs. (10.9 kg) AP, HC, AA, Illum. |

| Rate of Fire | 15 – 20 rounds per minute |

Mark 10 Torpedoes

These boats were capable of firing the 21-inches Mark 10 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark 10, a 1917 design entering service in 1918. From 1927 these were the Mod 3, last designed by Bliss and manufactured by the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport. They equipped the WWI R and S boats, still soldiering as a backup, as a trusted straight course in replacement for the infamous Mark 14. Before the latter had its defaults ironed out in 1942-43, the Mark 10 was in high demand and stocks starting to dwindle down rapidly. Thus, production was maintained until 1943.

⚙ specifications Mark 10 Mod 3

Weight: 2,215 lbs. (1,005 kg)

Dimensions: 183 in (4.953 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater

Range/speed setting: 3,500 yards (3,200 m) / 36 knots

Warhead: 497 lbs. (225 kg) TNT or 485 lbs. (220 kg) Torpex

Guidance: Mark 13 Mod 1 gyro

Mark 14 Torpedoes

In 1941 as completed they carried the Mark 14. Unfortunately the model was infamous for its legendary unreliability, explaining the poor results obtained in 1942 and until mid to late 1943; Long story short, the Mark 14 was a revolutionary new model that was tailored to use a gyroscope combined with a magnetic pistol. The principle was not to detonate on impact, but use magnetoc proximity of the enemy hull to explode ideally under the hull of the target. This way, it was easier to break its hull instead of just making contact below the waterline. These torpedoes were designed at the Naval Torpedo Station Newport, Rhode Island from 1930 and considered state of the art, benefiting from a $143,000 budget for its development.

Production was pushed forward after testings, and at 20 ft 6 in (6.25 m), it was incompatible with older submarines’ 15 ft 3 in (4.65 m) torpedo tubes, like the R and O classes. It was also the best performer, capable of 4,500 yards (4.1 km) at 46 knots (85 km/h). Lots of promises, but the war proved that testings had not been thorough and the rate of misses compared to the Mark 10 became obvious in reports in 1942, this infuriated many captains that disabled the magnetic pistol, but did not solve the problem as it was proved later that their too fragile impact fuse was also faulty.

Responsibility lied with the Bureau of Ordnance, which specified an unrealistically rigid magnetic exploder sensitivity setting while not providing enough funding to a feeble testing program. BuOrd had a hard time later accepting it and enable a new serie of tests, which were mostly from private initiatives.

Only by late 1943 and early 1944 most problems had been allegedly fixed, so that the 1944 Mark 14 at least allowed captains to claim far more kills. The “mark 14 affair” sparkled a lot of controversy postwar and it’s not over.

⚙ specifications Mark 14 TORPEDO

Weight: Mod 0: 3,000 lbs. (1,361 kg), Mod 3: 3,061 lbs. (1,388 kg)

Dimensions: 20 ft 6 in (6.248 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater steam turbine

Range/speed setting: 4,500 yards (4,100 m)/46 knots, 9,000 yards (8,200 m)/31 knots or 30.5 knots

Warhead Mod 0: 507 lbs. (230 kg) TNT, Mod 3: 668 lbs. (303 kg) TPX

Guidance: Mark 12 Mod 3 gyro

Sensors

QCC sonar: The QC/JK gear was located in the Conning Tower, companion units with the QC gear as active/passive sonar and JK gear (passive only). Raides and lowered by a hydraulic system, training by electric motor controlled by handle in the operating station. QCC: No data.

JK sonar: The JK/QC combination projector is mounted portside. The JK face is just like QB. The QC face contains small nickel tubes, which change size when a sound wave strikes this face. (The NM projector, mounted on the hull centerline in the forward trim tank, is used only for echo sounding.)

Se the full reference here

Modernization

In 1942-1943, both subs were rebuilt with the new wartime standard CT which allowed them to submerge quicker. Their puny 3-in/50 deck gun was retired as well as the new obsolete two liquid-cooled browning cal.05/90 heavy machine guns. Instead the deck gun was a more massive 5-in/25 Mk 17, and two 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk 4 were installed on forward and aft CT platforms. They also mounted the SD and SJ radars.

⚙ Mackerel class specs *marlin |

|

| Displacement | 825(800*) tons surfaced/ 1,190(1165*) tons submerged |

| Dimensions | 243 ft 1 in x 22 ft 1 in x 13 ft 0+1⁄4 in (74.09 x 6.73 x 3.969 m) |

| Dimensions* | 238 ft 11 in x 21 ft 7+1⁄4 in x 13 ft 0+1⁄4 in (72.82 x 6.585 x 3.969 m) |

| Propulsion | 2× EBDD diesels 1,680 bhp, 2× EDEM 1,500 bhp sub, 2× 60-cell Sargo batteries |

| Propulsion* | 2× ALCO diesel 1,700 bhp (1,300 kW), 2x GE EM 1,500 bhp (1,100 kW), 2 × 60-cell Sargo batt. |

| Speed | 16 kts surfaced/ 11 kts sub. |

| Speed* | 14.5 knots (27 km/h)/9 knots (17 km/h) |

| Range | 6,500 nautical miles (12,000 km) at 10 knots |

| Range* | 7,400 nautical miles (13,700 km) at 10 knots |

| Max service depth | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Armament | 6x 21-in TTs (4 fwd, 2 aft, 12 torpedoes), 1×3-in/50 gun, 2x 12.7mm/90 AA |

| Sensors | QCC-JK suite, SD-SJ radars 1942-43 |

| Test Depth | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Crew | 4 officers and 33/34 ratings |

General Evaluation

Both “M-class” spent their careers from Submarine Base New London in Connecticut alternating with Portsmouth Navy Yard. They were used for training and research and so contributed to the development of submarine and ASW in wartime. They saw little action if any, but during the brief “second happy time” of Dönitz when U-Boats were sent close to US shores, still with little safety measures taken by Admirakl King (convoys, blackout, etc). On 12 April 1942 as Mackerel was underway to Norfolk, she was attacked by a German U-boat, which missed. Eager for action, her captain counter-attacked and but was unsuccessful. Apart Marlin performing as “Corsair” in the 1943 movie “Crash Dive” at Submarine Base New London there is nothing really notable in their peaceful career, unlike their pacific fleet subs counterparts. They served their purpose dutifully and were decommissioned in November 1945, scrapped in 1946-47. They closed the concept of classic coastal submarines, as the 1950s leaned towards new tech already, albeit the core principle was the same. The next Barracuda class were small “ambushers” for restricted waters that could be mass-produced. Reminds something ?

The Mackerel class in Action

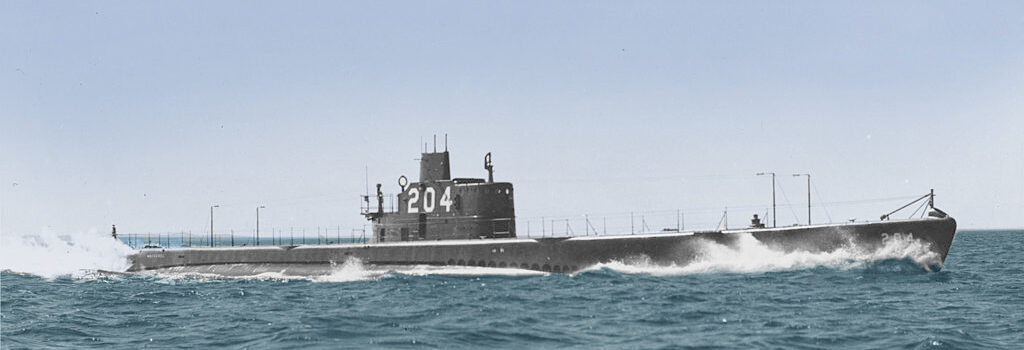

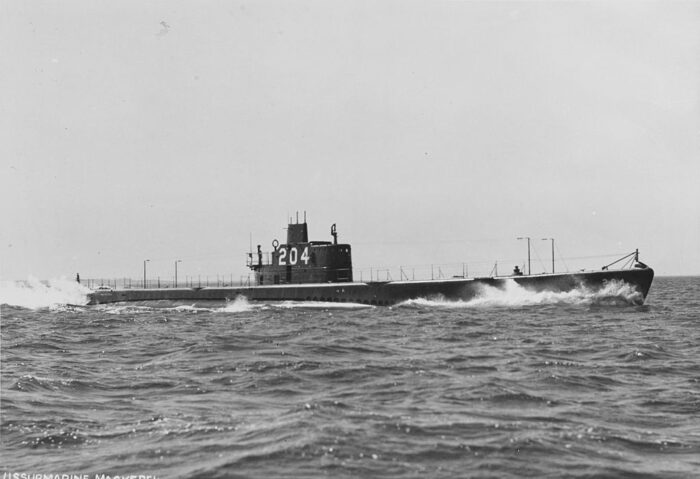

USS Mackerel (SS 204)

USS Mackerel (SS 204)

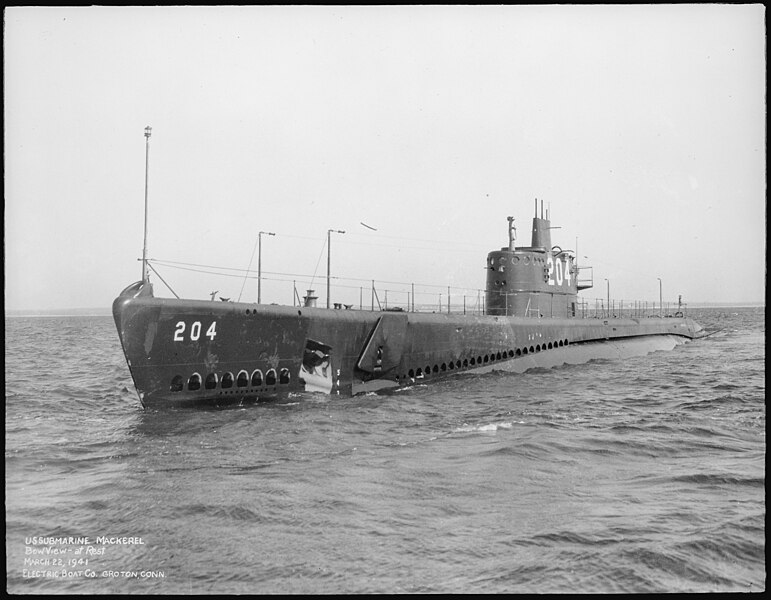

USS Mackerel’s keel was laid down on 6 October 1939 at Electric Boat Company, Groton, Connecticut. She was launched on 28 September 1940, sponsored by Mrs. Cora Furlong, wife of Rear Admiral William R. Furlong the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance (and in part responsible for the infamous Mark 14 torpedo). Mackerel was commissioned on 31 March 1941 as the lead boat of a class of near-sisters.

FromMarch to May she had trials and shakedown, from Louisiana and Panama to Canada and trained until the war broke up in December. During the war she remained assigned to Submarine Squadron 1 at the submarine base of New London, Connecticut (east coast) to participate in training and improvement of the submarine force. Some features were tailored to bring support services to the Underwater Sound Laboratory as well as for the the Prospective Commanding Officers Schools, also at New London. She was also planned to train Allied surface vessels and aircraft in antisubmarine warfare in the Atlantic given her size was close to axis subs.

While in regular yearly exercises she ventured north to Casco Bay and south to Chesapeake Bay in ASW. While in the New London-Narragansett Bay area, she joined Task Group 28.4. This was the USN antisubmarine development detachment. She was also regularly detached to the Underwater Sound Laboratory helping to improve current sonars and new hydroacoustic solutions. She helped develop new detection tactics as well.

On 8 April 1942 there was a near-fatal friendly fire incident: Given her small size and unusual shape (only two were built after all) she was mistook for a probably Type VII U-boat by a USAAF P-38 Lightning fighter. The latter dropped four bombs, straddling her poop during submerged exercises while training with the patrol vessel USS Sapphire (PYc-2). It happened just 3 nautical miles (5.6 km; 3.5 mi) south of the Watch Hill buoy in Rhode Island. At least two bombs were accurate and would have probably badly damaged her. But they ricocheted 100 feet (30 m) off the water and became duds, probably because of the bouncing schock. Sapphire witnessed this, signalled the aircraft in vain. She was just 1,000 yards (910 m) away off Mackerel′s starboard quarter.

On 12 April 1942, there was another incident, as she was underway Norfolk, Virginia. While 100 nautical miles (185 km; 115 mi) off Cape Charles, Virginia, on 14 April, USCGC Legare (WSC-144) sighted her at 20:30. Her captain was unaware of her presence in the area (miscommunication between the USN and USGC) and believed she was a German U-boat. He closed fast, signalled general quarters, but managed to establish her identity before it was too late, probably also thanks to the good weather. Sorry for the error and fright she gave to Mackerekl’s crew, her offered to escort her all the way to Norfolk, also avoiding more mis-identifications along the way. They entered Norfolk at 21:30.

However by 23:15, USCGC Legare stayed 2,000 yards (1,830 m) astern of her, when the submarine made two unannounced quick course alterations and she changed course herself to match these. Mackerel’s spotters in between sighted two torpedo trailed, heading for her. Her capatin manage to evade these and sighted what they believed was a German U-boat surfaced further our. They soon observed a new torpedo trail, this time in direction of USCGC Legare. Mackerel then had prepared her tubes, took the right angle and fired two torpedoes at the U-boat. But the latter just managed to leave the area and disappeared into the darkness. USCGC Legare sighted the torpedo and initially thought Mackerel had fired by error. They took evasive action, and it missed frm 20 yards (18 m). Legare lost contact with Mackerel and spent two hours looking for the U-Boat signalled by Mackerel. Further reports concluded that Mackerel had mistakenly fired a torpedo at Legare.

However the same night, before noon at 05:08 on 15 April 1942, she spotted the same probable U-Boat surfaced near the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay laying in ambush. She fired a torpedo at the U-boat, no hit. The U-boat saw the torpeod trail and evaded at high speed. Depending on the modets they were capable of 17-18 knots, more than Mackerel. Again she was outdistanced but signaled the U-Boat to USS Tourmaline (PY-20) on patrol nearby. She joined Mackerel in the search, but they found nothing. This was the only encounter of USS Mackerel (or the class at large) with the enemy during the war.

Later she worked woth the 5th Naval District for ASW maneuvers in the Chesapeake Bay, coordinated with the U.S. Army Air Forces and U.S. Navy planes and returned to New London. At 09:50 on 4 May 1942 while off Rhode Island she was mistook by the tanker El Lago and its USN Armed Guard detachment opened gunfire from 4 nm (7.4 km; 4.6 mi) south of Watch Hill Light. She made a crash dive, there was no damage.

In September 1945 as the war was over, she was ordered to Boston to be decommissioned, which was done on 9 November 1945. Stricken on 28 November 1945 she was kept in mothball for two years, and sold for scrap to the North American Smelting Company (Philadelphia) on 24 April 1947. She had won no battle stars like her sister, but instead the American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal and World War II Victory Medal.

USS Marlin (SS 205)

USS Marlin (SS 205)

USS Marlin (SS-205) was also the first to be named after the large game fish. She was laid down by Portsmouth Navy Yard on 23 May 1940, launched on 29 January 1941 and commissioned on 1 August 1941. After usual trials, training and shakedown, the war broke out. She was based at New London like her sister for half a year, bur departed on 21 March 1942 for Casco Bay in Maine, joining TG 27.1, to train newly commissioned escorts in ASW tactics. She was bac at the submarine base on 18 April, operating off Long Island Sound in 1942.

On 7 January 1943 she was in Casco Bay with TG 27.1 until 16 January. Until the end of the war, she kept alteranting war patrols on the eastern seaboard and and training escorts off New London and Portsmouth. She was featured also in the 1943 “crash dive” with Tyrone Power as “USS Corsair” with a modifed CT.

By 26 July 1945 she was starting a submerged approach on Chaffee (DE-230) when colliding with the sub-chaser SC-642. Damage was light on both. In September 1945 she was escorted by Chetco (AT-99) from Portsmouth to New London.

On 20 October she left New London with USS Skipjack (SS-184) for Bridgeport and continued to Boston until 31 October to be decommissioned on 9 November. She was mothballed for a short time, sold 29 March 1946 to the Boston Metals Company in Baltimore.

Books

Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis NIP

Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990 Greenwood Press.

Alden, John D., Commander, USN (retired). The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy Annapolis NIP 1979

Johnston, “No More Heads or Tails”, pp. 53–54

Blair, Clay, Jr. Silent Victory. New York: Bantam, 1976

Lenton, H. T. American Submarines (Navies of the Second World War) Doubleday, 1973

Silverstone, Paul H. U.S. Warships of World War II Ian Allan, 1965

Schlesman, Bruce and Roberts, Stephen S., “Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants” Greenwood Press, 1991

Campbell, John Naval Weapons of World War Two. Naval Institute Press, 1985

The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy: Design and Construction History Hardcover 1979 by John D. Alden.

Gardiner, Robert, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946, Conway Maritime Press, 1980.

Alden, John D., Commander (USN, Ret). The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy: A Design and Construction History. NIP

Blair, Clay, Jr. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. New York: Bantam, 1976. ISBN 0-553-01050-6.

Campbell, John Naval Weapons of World War Two (Naval Institute Press, 1985)

Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. NIP

Lenton, H. T. American Submarines (Navies of the Second World War) (Doubleday, 1973)

Roscoe, Theodore. United States Submarine Operations in World War II. NIP

Links

on navypedia.org/

navsource.org

The Submarine Has No Friends: Friendly Fire Incidents Involving U. S. Subs

on navsource.org

on en.wikipedia.org/ Mackerel class submarine

on oneternalpatrol.com

on theleansubmariner.com/

on pigboats.com/

web.mit.edu/ Newell analog computers

on pwencycl.kgbudge.com

on navsource.org

on uboat.net/

on navsource.org

on uboat.net

on shipcamouflage.com

Model Kit

USS Mackerel SS-204/Marlin SS-205 circa 1942 – Iron Shipwrights 1:350

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign