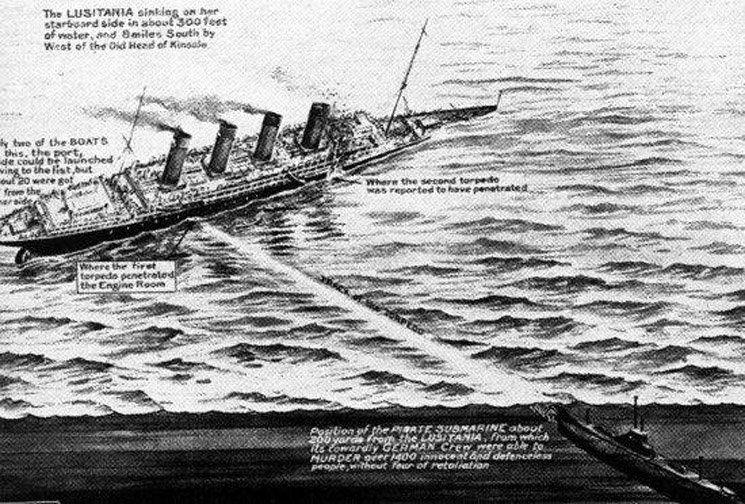

Above: The position of Lusitania during its sinking

Above: The position of Lusitania during its sinking

After the famous Titanic, sunk in peacetime, the sinking of the Lusitania remains one of the greatest maritime tragedies in history, whose consequences have been decisive as a triggering factor of the entry into the United States in the first world war war alongside the entente powers. Ten years ago, it was Europe’s golden age, “La Belle Epoque”. Large transatlantic companies competed with prestige and luxury ships, technical prowesses, and millions of pounds sterling in luxury items and accomodations worthy of a the most pretigious hotels, all under the incredulous gaze of the press. Of these, two giant shines in passenger transport, the Cunard and the White Star Line. If the latter remains famous for having commissioned in 1911-12 three huge ships, the Britannic, the Olympic, and the Titanic, whose history is no longer told, its great historical rival had eclipsed these in the newspapers by the triumph of a new challenger, the Mauretania, from 1907. The latter came out three months after the Lusitania, taking the title of the world’s largest ship, and adding the title of the fastest liner in the world, taking the legendary Blue ribbon and retaining it for 20 years, not a small feat. The Cunard wishing to keep three ships on its Atlantic line, like the White Star line, later launched the Aquitania.

In 1914, the three giants were not requisitioned for future tasks (troop transport and auxiliary cruisers) but kept in their original role on the transatlantic line. On the other hand, later, the Mauretania was converted indeed as a troop transport. For economical and safety reasons, the ship saw her scheduling going from one trip per week to one per month and two boilers closed, her speed falling to 21 knots. From February 15, 1915, the Kaiser authorized unrestricted submarine warfare: His U-Bootes could now roam freely along the English islands, and off the coast of Ireland in the North Atlantic. The new models of oceanic submersibles built also allowed such range. On 18 February, this decision came into force and from then on all neutral ships likely to supply Great Britain would be torpedoed without warning. However, German commanders had two restrictions, concerning certain neutral ships, and concerning ships not carrying arms or ammunition.

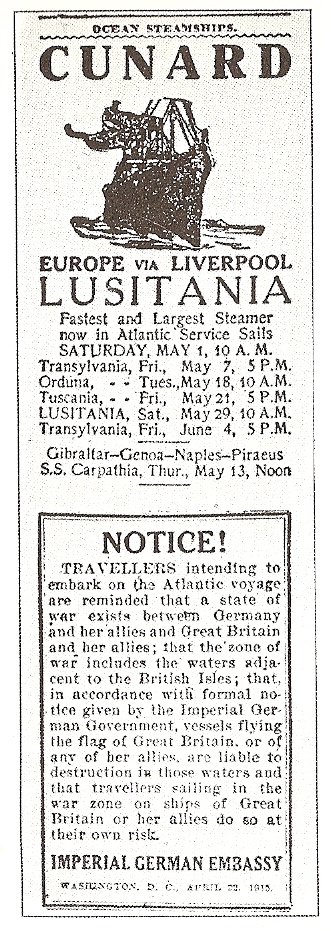

From February 17 to 24, 1915, from Liverpool, the Lusitania made her 101st crossing to New York, which was celebrated as it should be. She stayed a week at the dock before leaving. In doing so, passengers with dual nationality (German and American) who were to board her consulted the German Embassy which advised against them to make the trip. The Embassy also made a note in English explaining that taking place on board could be done only at his/her own “risk and peril”:

From February 17 to 24, 1915, from Liverpool, the Lusitania made her 101st crossing to New York, which was celebrated as it should be. She stayed a week at the dock before leaving. In doing so, passengers with dual nationality (German and American) who were to board her consulted the German Embassy which advised against them to make the trip. The Embassy also made a note in English explaining that taking place on board could be done only at his/her own “risk and peril”:

“NOTICE: TRAVELERS intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Official notices given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of its allies, are bound to be destroyed in those waters and up to the United States of America, at their own risk.

IMPERIAL GERMAN EMBASSY, Washington, DC April 22, 1915.”

The press got wind of this note and the agitation began to cause some cancellations. Confident however, Captain William “Bower Bill” Turner, continued to say that his ship was too fast for U-Bootes and “safer than a New York trolley”. At noon, the ship cast off the moorings and retrieved SS Cameronia passengers and crew. Three German spies were discovered shortly after departure and sent to the bottom of the hold. 1257 passengers had taken their seats aboard, including – as was customary on the big transatlantic – celebrities and businessmen of the time like the millionaire Alfred G. Vanderbilt, the genealogist Whitington, the engineer Frederick Stark Pearson, the pianist Charles H. Knight, theater actors Julius Miles Forman and Charles Klein, impresario Charles Frohman, writer Ian Holbourn, architect T. Pope, a wealthy art collector…

During her return voyage, far from the golden comfort of the lounges, the Admiralty offices received a dispatch from the coast stations intercepting a UFO radio message from Commander Walter Schwieger’s U-20 who was operating west of Ireland and headed south. On the 5th and 6th of May, the latter was sinking three ships in the vicinity of the Fastnet, the final point of the line followed by the Lusitania. As a result, on the 6th, the Royal Navy issued a warning to all ships present that a U-Boote was prowling on the south-west coast of Ireland. The Lusitania received the message twice and Commander Turner decided to proceed with security measures: Closing the watertight doors, unlocking the canoes on the davits to launch them more quickly, partial extinction of the lights, and doubling the watchers.

During her return voyage, far from the golden comfort of the lounges, the Admiralty offices received a dispatch from the coast stations intercepting a UFO radio message from Commander Walter Schwieger’s U-20 who was operating west of Ireland and headed south. On the 5th and 6th of May, the latter was sinking three ships in the vicinity of the Fastnet, the final point of the line followed by the Lusitania. As a result, on the 6th, the Royal Navy issued a warning to all ships present that a U-Boote was prowling on the south-west coast of Ireland. The Lusitania received the message twice and Commander Turner decided to proceed with security measures: Closing the watertight doors, unlocking the canoes on the davits to launch them more quickly, partial extinction of the lights, and doubling the watchers.

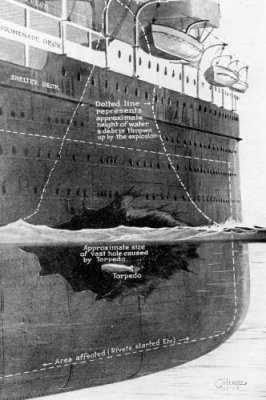

On May 7 at 11 am he caught a new message from the Admiralty, and then decided to get closer to the coast rather than stay in the open sea, where he hoped to be safer. Commander Schwieger was running out of oil fast, but he still had three torpedoes left. He finally decided to return, and was sailing at full speed on the surface. The weather was clear. Suddenly, around 13:00, one of the watchmen reported a smoke on the horizon. The Lusitania was 70 km off the village of Old Head of Kinsale on the coast when it crossed the submarine path. Schwieger could not believe how lucky he was to be able to cross the liner, which was coming to the west, facing him. He could very well intercept her, but not pursue the ship as he would have been quickly out of reach. Around 14:10, at a good distance, he dives to avoid being seen, and orders the tube 1 to fire. The torpedo goes straight to the side, at the front of the huge black mass…

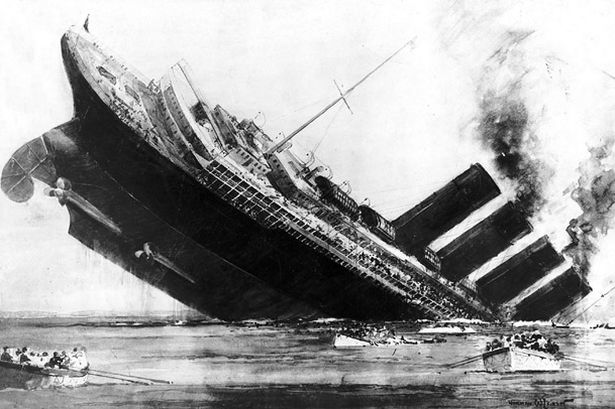

As a result of the opening immediately to port in the hull, a second explosion tore the latter over a great length. Testimonies spoke later of two torpedoes, but the official reports and the number of torpedoes remaining on board pleaded the opposite. Be that as it may, the giant offered a gaping wound at the bow, gushing tens of tons of seawater, sailing at full speed. Turner immediately knew what he was doing and launched an SOS while steps were being taken to have the passengers board the rowboats asap. But the list increased at high speed, including the pitch, because quickly, as the bow played a “plow share” effect, she still sank further as the ship plunged. Unfortunately her compartmentation technology dated before the Titanic, and she could not claim to be unsinkable. From then on, her fate was sealed much faster than the former (18 minutes). Turner, however, decided to try to go down the nearby coast to beach her giant ship. But the steamer was now too heavily loaded, and no longer answered. He ordered the speed to be reduced, and the trimmers began to evacuate the flooded rooms.

On the deck Turner and his crew could not stop the panic that had taken hold of the passengers, as the launching of the boats, though this time in sufficient numbers, was a nightmare: The Lusitania had been assembled with salient rivets, and with the important list, most of the lifeboats heavily loaded, scraped the hull down and consequently, arrived at the water with leaks provoked by these rivets. The handling of the davits proved difficult for the crew members, many of whom came from the Cameronia (an ironic timewarp wink at James Cameron?). By feverishness and lack of coordination, turned, either downhill, either with the water, still others fell brutally and crashed on passengers, were broken… In the end, out of 48 boats, only 6 managed to stay afloat, laden with women and children. The end of the giant was terrible and reminiscent of the Titanic, her bow twisted, the rear lifted, then the hull broke from the front. One of the chimneys exploded, and fell on the swimming survivors, followed by the other three. Finally, she capsized and sank, belly in the air at 2:28 pm, just 8 miles off the coast of Ireland.

In total there were 1198 victims, including 128 Americans. The shock was considerable, but it was only the first trigger that led the United States into the war. The question of whether the Lusitania carried arms and ammunition (the British fiercely denied this fact, and described Schwieger as a war criminal) remains controversial. Some believe that “cheese” stamped ammunition was on board, smuggled, and caused the second explosion on the torpedo impact. It remains that the famous undersea explorator Robert Ballard visited the wreckage during a campaign and found nothing convincing. For him, the “ammunition” was stored too far from the impact, but it was the coal dust residue of the affected compartment that would have detonated.

In total there were 1198 victims, including 128 Americans. The shock was considerable, but it was only the first trigger that led the United States into the war. The question of whether the Lusitania carried arms and ammunition (the British fiercely denied this fact, and described Schwieger as a war criminal) remains controversial. Some believe that “cheese” stamped ammunition was on board, smuggled, and caused the second explosion on the torpedo impact. It remains that the famous undersea explorator Robert Ballard visited the wreckage during a campaign and found nothing convincing. For him, the “ammunition” was stored too far from the impact, but it was the coal dust residue of the affected compartment that would have detonated.

In any case, faced with the scandal provoked by this affair, the Kaiser ordered a “truce” for the big steamers, until September. A satirical medal was melted in Munich commemorating the sinking of the ship and the propaganda seized the case, reinforcing the hatred of the British against the “barbarians”, and cultivating some deep resentment in the Americans press, which was added to German secret operations on US soil (like a fifth column trying to blew up ammo depots) and a secret cable to the Mexicans promising rewards if they attacked the border, intercepted by the British. For all what was wrote about it, books, movies, documentaries anc conspiracy theories which followed for 100 years, the sinking of the Lusitania was an historical event of first magnitude, staying well above the mass of unnamed freighters, coasters, ferries and tall ships that disappeared in this war in similar circumstances.

Sources, read more:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinking_of_the_RMS_Lusitania

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Lusitania

Documentaries:

https://youtu.be/k1d2zxek7zU

The Lusitania (World War 1 Documentary) | Timeline

Terror At Sea Sinking Of The Lusitania Documentary

https://youtu.be/Go_n1HSPz-k

Dark Secrets of the Lusitania – Documentary movie

The Sinking of the Lusitania

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign