For the seventh use of the world’s famous name “dreadnought” UK saw its most fitting application could only be its first nuclear-powered submarine. The fruit of long R&D started in Britain postwar, HMS Dreadnought (S101) was a design worked on from 1954 -with opposition from Hyman Rickover at first- until the latest US S5W reactor was obtained via the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement. All other systems, from top to bottom, were provided by British yards and companies, chief of which was Vickers Armstrongs, Barrow-in-Furness on which converged all systems and sub-assemblies. As a result the largely experimental HMS Dreadnought was built between 1958 and 1963. Commissioned on April 1963, she stayed in service until 1980, bringing a first stepstone for the development of future classes, the Valiant, Churchill of the 1960s, Swiftsure in the 1970s, Trafalgar in the 1980s to the contemporary Astute.

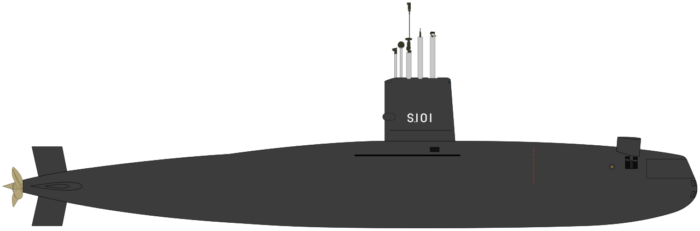

Rendition of HMS Dreadnought (pinterest)

Development

At the same times the Oberon and even the earlier late Porpoise class conventional submarines were built, the Royal Navy was working on a global nuclear program, both for civilian applications and nuclear deterrence, but also propulsion.

Seeing what’s was going on the other side of the pond, the launch of USS Nautilus in 1957 was not really a surprise. It was understood that the USN was working on nuclear propulsion already in the early 1950s. Let’s recall that the first “nuclear reactor”, the Chicago Pile-1 was a simple assembly already working in the US back in 1942. British scientists concentrated on nuclear propulsion (general utility) already in 1946, with tests made on a plant until the program was terminated by October 1952 for various reasons, notably some underfunding (and perceived lack of results).

In 1955 indeed the design of the USS Nautilus, world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, was completed and construction started. During post-commission exercises with the Royal Navy, USS Nautilus showed its immense the advantage while deployed against ASW frigates and even destroyers and despite their experience and extensive techniques developed during the Battle of the Atlantic. Thus spurred the First Sea Lord, Admiral The Earl Mountbatten, and the Flag Officer Submarines Sir Wilfred Woods to relaunch British plans nuclear-powered submarines.

It was soon believed that convincing the USA to release their tech would save considerable expenses. After all, propulsion was not nuclear deterrence and by that time, the British Forces already had a park of nuclear bombs carried by the famous “V-bombers” program. Albeit less sensitive it was to encounter some resistance, and not surprisingly from the top. Indeed relations between Admiral Mountbatten and US Navy CNO Arleigh Burke were excellent. Opposition came from Rear Admiral Hyman Rickover in charge of the US naval nuclear power programme which argued this was such an advantage as to deny transfer of technology. He also argued of dubious commeercial practices and porosity to spying as shown in recent affairs and the Rolls Royce Nene engine sold to the Soviets which resulted in the Mig-15 encountered in Korea (this was more complicated but you got the idea).

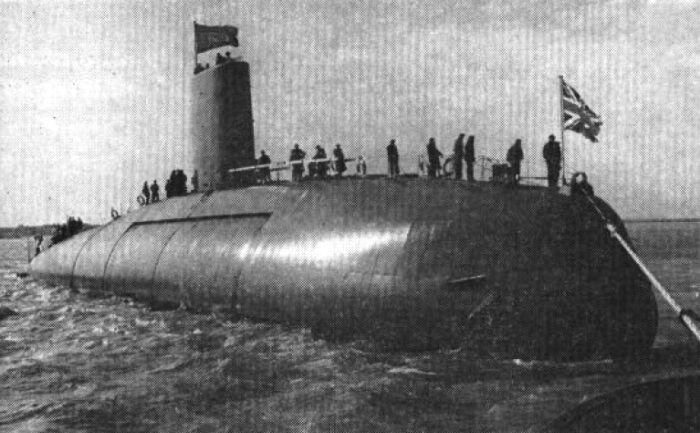

Pinterest photo.

Rickover prevented Mountbatten inspecting USS Nautilus. Whe he came eventually to Britain in 1956 to see British advances and guarantee that he changed his mind and eventually, withdrew his objections. Still, he insisted to only allowed access to the third generation S3W reactor, in order to keep some advance. On his side, Mountbatten wanted to obtain, not only the core, but the entire powerplant of a Skipjack-class. The latter in addition had a S5W reactor. Rickover again, objected, but he was passed over by the top brass and Burke through the “American Sector” and 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement.

The name “Dreadnought” signified still at the time a land-mark in naval history and revolutionary design, causing little discussion. She was laid down at Vickers, Barrow in Funess on 12 June 1959.and had at the time the largest pressure hull ever built in Europe made of QT35 steel (QT standing for Quenched and Tempered) to reach far greater depths than the Oberons. Same standards of quietness were also looked upon.

Design of HMS Dreadnought

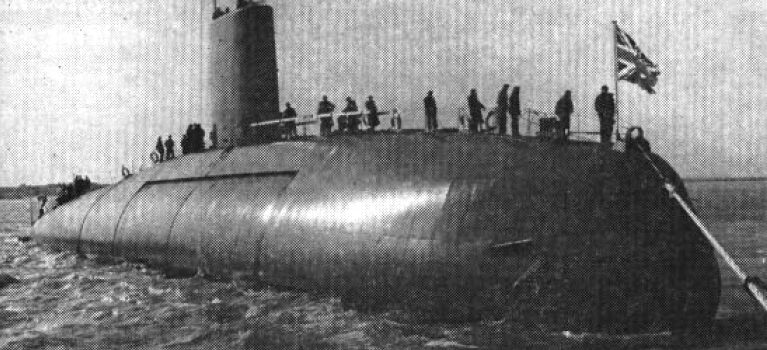

HMS Ocelot by comparison (pinterest). A brand new design with a different type of streamlining.

Hull and general design

The first British SSN certainly integrated some of the work done in the US on USS Albacore and teardrop shapes. She was indeed completely different from the Oberons/Porpoise, far more classic in their approaches, with a fully separate outer hull/deck and twin shafts aft. The sonar was placed on a fattened bow in a faired dome. On HMS Dreadnought, the lower hull was practically a constant ellipse from bow to stern, and the upper outer hull was a but less streamlined, with a diustinctive hump for 2/3 of the hull, and a quite distinctive bow shape, not cylindrical but with an inverted bow and flared sides. The bow itself was almost flat and vaguely resembled a ram. The two diving planes were installed just aft of the bow. There was a narrow and tall sail, not ublike the one used on the Skipjacks and quite different from the Oberons. Overall her design was much more “cleaner” and streamline than any submarine made in Britain to that point. Just 20 years after the arguably ugly and complicated T class this was a breath of fresh air. She could also dive down to 230 m operation depht with a 300+ meters emergency reserve and crush depth probably around 350 m.

In terms of size, HMS Dreadnought was, without surprise absolutely massive, at least in bulk and displacement. She was rated for 3,500 tons surfaced (3,556 tonnes) indeed, and 4,000 tons submerged (4,064 tonnes), double that of the Oberons (2,030 t, Submerged 2,410 t). Yet, she was shorter at 265.7 ft (81 m) versus 295.2 ft (90 m). But she had one more deck in the internal hull, which made all the difference, with 31.2 ft (9.5 m) in beam and 25.9 ft (7.9 m) in draught (versus 26.5 x 18 ft or 8.1 x 5.5 m). No doubt she felt still roomier to its crew of 113, far more than the 69-77 of the Oberons. Automation was still not a thing and her powerplant and monitoring was apparently still human-intensive. She also carried more torpedoes than the Oberons (24 versus 20), but had no stern tubes. Like the Oberons she also had six bow tubes, but they were faired differently. Yet, to gain time in design, the same safety and opening systems and procedures were taken in account.

Powerplant

Pinterest photo.

HMS Dreadnough of course parted away from noisy, vibrationg diesels and embraced the solution of a jointly made Westinghouse/Rolls-Royce S5W nuclear reactor. It was placed for stability and balanced in its lead-based main shielding in the center of the boat. The sail was thus placed ahead of it to house all the command center below. The reactor was then connected behind to two

sets of English Electric geared steam turbines, mated to a single geared crankhaft to a single shaft. Thus powerplant was rated for 15,000 hp for a top speed of 15 knots surfaced and 28 knots underwater, which were less than the 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) of the Skipjacks. The latter however applied the teardrop formular to the core, which probably helped and that speeed was not “practical” in that they made for a noisy boat. The British approach was different and privileged a noise level that was to be not greater than the Oberons. This was still almost way more than the Oberons, including surfaced as the latter were only capable of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).

Range was ubnimited except from the crew’s endurance and food reserves on board.

Armament

It is likely the bulk of her torpedo complement of 24 vectors was made of the old but trusted Mark 8 mod 4, a wet-heater model, straight course, capable of 5,000 yards at 45 knots. However more modern models were also probably carried and at least tested. The Mk 24 Tigerfish arrived was adopted just as Dreadnought was decommissioned in 1980. This was the most advanced torpedo ever designed for submarines in UK, entering service from 1979.

Mark 20C Torpedo

An improvement of the Mark 20S Torpedo, first British passive homing torpedo entering service in 1955. The Mark 20C was developed in the early 1960s, susperseded by the Tigerfish in the 1980s.

They were “short” torpedoes and used notably in the Oberon’s rear tubes.

⚙ specifications Mark 20C

Weight 1,810 lbs. (821 kg)

Dimensions: 254.5 in (6.464 m)

Propulsion: Battery

Range/speed setting: 7,000 yards (6,600 m)/23 knots

Warhead: 196 lbs. (89 kg)

Guidance: Homing, active/passive

Mark 23 Grog

A wire-guided version of the Mark 20 with dual-speed mode, tested from 1955 and worked on further aftere “Mackle” project was cancelled in 1956. The first were delivered in 1959 but it entered service in 1966, and considered already obsolescent, not operational until 1971. But they were never popular as thir control system was failing at extreme range.

⚙ Specifications Mark 22 Grog

Weight: 2,000 lb (907 kg)

Dimensions: 14.9 ft (4.54 m) x 21 in (530 mm)

Propulsion: Battery (perchloric acid)

Range/speed setting: 12,000 yd (11,000m)@20 knots, 8,900 yd (8,100 m)@ 28 knots

Warhead: 89 kg (196 lb) Torpex

Guidance: Wire-guided to point, passive sonar acquisition for terminal guidance

Sensors

Type 1002 radar: Operating in X-band, surface+air warning and ranging. Type AKU(3) or AKS(2) antenae for 360° or sector mode. Displays on a PPI scope and A-scope for range finding. FRQ 9 650 MHz ± 50 MHz (X-band), pulse repetition frequency (PRF): 400 to500 Hz or 2 000 to 2 500 Hz, pulsewidth 1 µs or 0.2 µs, peak power 30 kW.

Type 2001 sonar: Hull-mounted, low-frequency, detection sonar designed for nuclear-propelled submarines. Active and passive with an array of 24 flat panels carrying 56 transducers. producing 24 active search beams with a beam tilts down 20 degrees. Sonar type developed specifically for HMS Dreanought.

Type 2007 sonar: Hull mounted long-range passive sonar, upgraded from the Oberon class.

Type 2019 sonar: Underwater acoustic recognition system.

UAH ECM suite: Designed by L3Harris, no more data.

“3D” rendition, original by Mike1979Russia, wikimedia CC.

⚙ specs. |

|

| Displacement | 3,500 tons surfaced (3,556 tonnes), 4,000 tons submerged (4,064 tonnes) |

| Dimensions | 265.7 x 31.2 x 25.9 ft (81 x 9.5 x 7.9 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft Westinghouse S5W reactor, 2 geared steam turbines, 15,000 shp (11,000 kW) |

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) surfaced, 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) submerged |

| Range | Unlimited but Food for 60 days at sea |

| Armament | 6 x bow tubes for 21 inch (533 mm) torpedoes, 24 rounds carried |

| Sensors | Type 1002 radar, type 2001, type 2007, type 2019 sonars, UAA ECM suite, DCA CCS |

| Crew | 113 |

Towards a fully british SSN

Meanwhile, the British industry managed to design and produce a completed hull and combat systems and eventually, British access to the Electric Boat Yard, which made these SSNs, had some influence in the way the hull was shaped, as well as construction methods. Rolls-Royce collaborated for this with the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority for full integration of the powerplant and internal insulation and shielding as well as the Admiralty Research Station, HMS Vulcan, Dounreay. They were working already when Rickover came in a properly British nuclear propulsion system, which superseded the Skipjack’s own installation. On 31 August 1960, order at last came at Vickers Armstrong yard for a new submarine, S102 submarine -still unnamed at that point- was to be fitted with the Rolls-Royce’s PWR1 nuclear plant, and became the first all-British nuclear submarine, HMS Valiant, laid down on 22 January 1962 and launched on 3 December 1963, commissioned on 18 July 1966, three years after Dreadnought.

Career of the HMS Dreadnought SSN

HMS Dreadnought was launched by Queen Elizabeth II in person, in a grand ceremony attended by heads of the commons and Lords, all the admiralty, on Trafalgar Day, 21 October 1960. She was fitted out at a nearby floating dock with the reactor installed on 8 July 1962, tested until critical in November 1962. Sea-trials started by mid-December 1962 in the Irish Sea an,d she amde a first diveat Ramsden Dock on 10 January 1963. She was eventually commissioned on 17 April 1963.

In 1964 she trained extensively for her new systems, and visited Norfolk in Virginia as well as Bermuda, Rotterdam, and Kiel for the Kiel week, drawing thousands of visitors. In October 1964 she took part in a joint maritime exercise with the USN and RCN in the north of Scotland. All along they were shadowed by three Soviet submarines and three Soviet ships. She made trips also to the Mediterranean, in Gibraltar in 1965, 1966, and 1967. On 19 September 1967 she left Rosyth for Singapore making along the way a high-speed run over 4,640 miles surfaced, 26,545 miles submerged, stting British records.

Profile of HMS Dreadnought by Mike1979Russia

Part of her missions were classified. On 24 June 1967 she was diverted to sink the wrecked and drifting German ship Essberger Chemist, evacuated and now a hazard to navigation. Three torpedoes did not sent her to the bottom. The gunners of the Frigate HMS Salisbury did, piercing her floatation tanks. Being built with a brand new steel for her hull she still experienced minor hull-cracking problems. But overall she was considered reliable and her vast internal spaces made her popular with the crews. On 10 September 1970, she had the major overhaul of her career major refit at Rosyth in Scotland. Her nuclear core was refuelled, her ballast tank valves changed by new models improved to reduce noise signature when used.

In early 1971, HMS Dreadnought took part in the Arctic exercise, codenamed “Sniff” under command of CO Alan Kennedy. On 3 March 1971 she became the first British SSN to surface at the North Pole.While inspected back in Faslane, the hull was inspected and minor damage was caused by the ice on her propeller as her bow and fins.

In 1973 she took part in this year’s Group Deployment, and worked out fleet exercises.

In November 1977, while under command Captain High Mitchell, her 8-month deployment to Australia was cancelled and she was rerouted via Gibraltar to the South Atlantic to join the frigates HMS Alacrity and Phoebe for Operation Journeyman off the Falklands to deter Argentine announced plans of invasion. HMS Dreadnought then started covert surveillance in Argentine waters and close to the shores.

Due to age, and lack of refit facilities for nuclear fleet submarines at the time, HMS Dreadnought was decommissioned in 1980, but not scrapped. She had been maintained afloat at Rosyth Dockyard in long term storage until safely disposed under the MOD’s Submarine Dismantling Project with her nuclear fuel long removed but interior still intact. In 2012 her periodic hull inspection led to measure for re-preservation and many in Barrow wich to purchase her and be returned to the town as a museum ship.

Read More/Src

Books

Vanguard to Trident; British Naval Policy since World War II, Eric J. Grove, The Bodley Head, 1987

Warships of the Royal Navy, Captain John E. Moore RN, Jane’s Publishing, 1979

James Jinks; Peter Hennessy (29 October 2015). The Silent Deep: The Royal Navy Submarine Service Since 1945.

Defence Estimates, 1964–65, page 72, 31st March 1964

Dreadnought: Britain’s First Nuclear Powered Submarine Feb. 2003 by Patrick Boniface.

Gardiner, Robert Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1947–1995

James Jinks; Peter Hennessy (29 October 2015). The Silent Deep: The Royal Navy Submarine Service Since 1945. Penguin

Links

rnsubs.co.uk/

The Silent Deep: The Royal Navy Submarine Service Since 1945 Couverture James Jinks, Peter Hennessy

Hopes Barrow built nuclear sub could go on display

/navypedia.org/

rmg.co.uk/

on en.wikipedia.org/

Videos

Pathe archives live aboard a nuclear sub 1969

Model Kits

HMS Dreadnought OKB Grigorov | No. 700104 | 1:700

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign