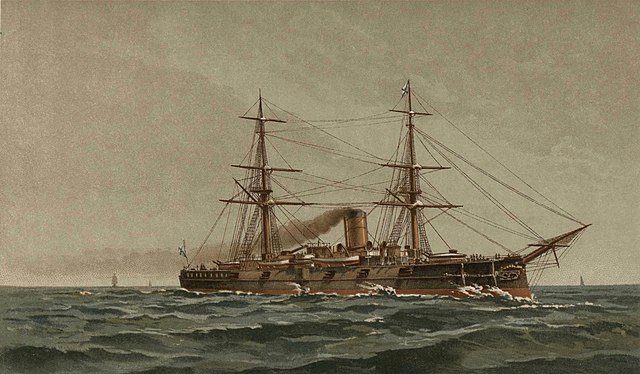

Armoured Cruiser Ryurik (1892)

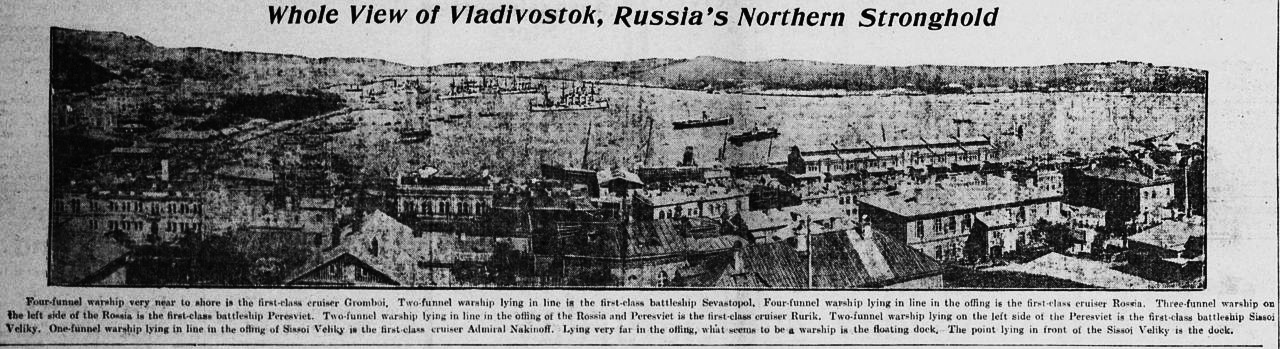

Imperial Russian Navy, 1890-1904

Imperial Russian Navy, 1890-1904

The Russian pacific cruisers

In 1881, the 20-year shipbuilding program, notably for the creation of the Pacific cruiser fleet, went along with the creation of squadrons of seagoing battleships. In grand total, Russia wanted a fleet 30 cruisers strong, with twenty-one light ones, classed as corvettes, nine “medium and large” ranked as frigates. These cruisers took into account expected tactical tasks to determine their design preferrences. The implementation of this program conducted logically to the creation of modern armored cruisers, characterized by the creation of more powerful seaworthy steam and fully rigged cruisers, all-metal, providing a significant reduction dislacement, using modern consruction techniques.

The development of cruisers of that kind was largely stimulated by the rivalry between Russia and England. The latter needed ways to reliably protecting its sea communications from any Russian attack in far-flung colonies. Tactical requirements of the Russian side was the ability to act independently (like frigates of old), in the absence of supply bases, and to deliver quick, powerful strikes without support, achieved an overall psychological effect greater than its actual consequences, and without looking for close combat with enemy ships.

The Russian objective by deploying these was to achieve panic, a threat to the enemy sea trade, which would have badly hurt British trade exchange market, causing a large inflation or market crash. Until 1895, they determined the main characteristics for Russian cruisers, which needed increased seaworthiness, high speed, autonomy as it as said, as well comfortable living conditions in “tropical” areas, saving the crew’s strength in a long voyage. Of course for combat, they needed a powerful armament and a decent protection calculated to provide them immunity against most cruisers of the time. The British indeed in 1890 deployed most of their second to third rate cruisers to distant station, taking place of former gunboats, keeping the best for the home fleet.

Going to the Pacific to conduct hostilities at a moment notice in waters known for typhoons, exhausting temperature (From 50°C and 90% moist to dropping icy cold in the north), rare supply depots or friendly ports, the impossibility of large repairs, all called also for extreme human stress. These cruisers therefore an extremely reliable technological package. Russian cruisers in addition could not count on numbers to make a difference when facing the Royal Navy, only intrinsict qualities to make a difference.

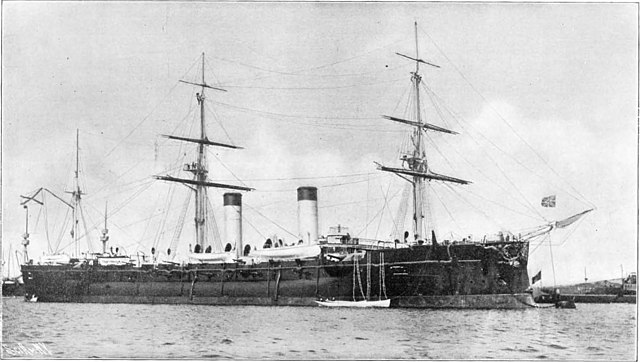

The vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean provided the Russians a tactical advantage, of elusiveness (contrary to the Baltic) and authorized efficient hit-and-run attacks. In turn specialists of the Russian Maritime Technical Committee (MTK) formed the tactical and technical requirements for armored cruisers, for this predefined “frigate rank”, mainly taking into account British experience in creating similar ships. The later armored cruiser Admiral Nakhimov (Baltic Shipyard) was built on instructions of the MTK following British armored cruisers. One result of the paraoia of 1890 was the prospect for British yards to fulfil exceptionally lucrative orders, and deliberately underestimated their capabilities to sell their most advanced models. The Royal Navy cruisers had better powerplants and offered more in power density, efficiency, weight and dimensions and were helped by the presence of several bases for replenishment and repairs, whereas the Russian were limited to Vladivostok.

The Russo-British naval rivalry enable the creation of large oceanic cruisers, with high speed and large autonomy, a trend already started in mid-1880s, in connection with the creation of the first-class transatlantic commercial steamers displacing 12,000 tons with long hulls and capable of 18.5-19 knots. At this speed and length of the hull, they represented 1-1.5 the average length of the ocean wave and having a refined hydrodynamic profile, large elongation with unloaded ends, closed forecastle up to amidships allowed to cut the wave rather than riding over it. If it was good for passengers, it was equally good for large cruisers, which benefited from a better stability as gunnery platforms and no loss of speed when trying to catch merchant vessels in heavy weather.

At the same time, the newest oceanic armored cruisers of the Nakhimov class (101.5 m, 16.38 knots) as opposed to the British Orlando class (91.44 m, 18.5 knots) could develop design speeds only on calm water and in heavy weather these relatively short wide and drafty vessels hopelessly lost speed, down to a mere 5 knots, unable to catch merchants steamers or sailing cutters. The British admiralty, having well studied the peculiarities of ocean-going steamers construction still resised E. Reed’s calls to use transatlantic steamers as examples to built cruisers, but the Russian came to different conclusions.

Design development

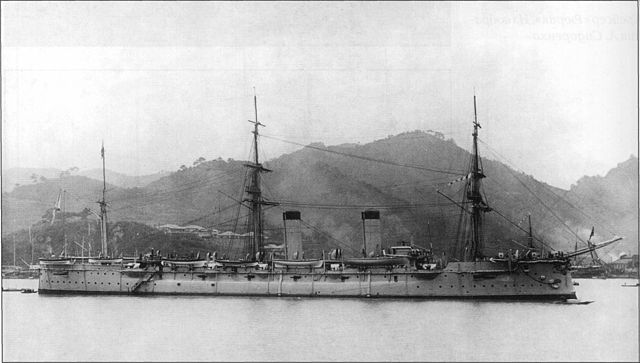

Russian armoured cruiser Admiral Nakhimov

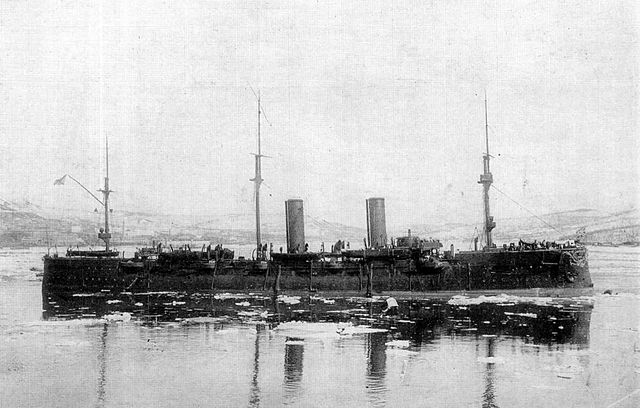

Pamiat Azova

Late 1880s Russian cruiser development

Recognizing the unsatisfactory seaworthiness and speed of Admiral Nakhimov in terms of the hull elongation, making her more akin a “battleship with cruiser armament”, Russian shipbuilders of the Baltic Shipyard workout several designs to take car of both seaworthiness and speed, while maintaining a sufficient level of armor protection. They looked at the French experience in armored cruisers, notably the brand new Dupuy de Lôme, and worked on a “semi-armored frigate”, the Pamiat Azova in the late 1880s.

In terms of displacement and firpower, the Pamiat was a “medium cruiser of frigate rank”. She surpassed Admiral Nakhimov in absolute length with an extra 14 meters of hull (45 feets) and lengthening of the hull with a more favourable ratio of 7.57 versus 5.46. This new project still assumed a significantly lower displacement of just 6,000 tons versus 8,500. Due to this elongation she was supposed to use an even less powerful powerplant, rated at 4000 shp versus 8000 shp, lighter and more economical, yet still provding a speed increase, even in stormy conditions, and up to 18 knots. There was also a minimal coal supply of 1,000 tons, making for a 3,000 nautical miles range.

However, at that design stage actual displacement still significantly exceeded design prospects, largely due to unknown size and weight of the power plant ordered in England, exceeding established figures. In this regard when completing Pamyat Azova it was concluded that by keeping her onboard armor protection, ensuring high speed and long cruising range obliged to further increase the absolute length of the hull, leading in turn to a larger displacement and then accordingly, a larger power plant.

In 1889, the British managed to create a powerful yet economical and compact steam engine, using vertical tubes (VTE), opening up new opportunities but at the price of side armor. Taking these into account, the designers of the world’s longest armored cruisers, the Blake class (design displacement 9,000 tons, 13,000 hp) quickstarted a new race. With 20,000 hp in forced draft, designed speed promised to reach 20-22 knots still with a cruising range of 10,000 miles at 10 knots. The British Admiralty considered this class so successful that construction of 1st class armored cruisers was completely stopped, at least until 1900, and the largest armoured cruisers in british service, before ending for good with the advent of the dreadnought. But this happened as Rurik was already in development.

A new cruiser for the east

The Imperial Russian Navy wanted a cruiser for the far east, specifically dedicated to act in case of a war between Russia and the United Kingdom. Russian admiral Ivan Shestakov was instrumental in this, submitting the design of Rurik to the Baltic Works at St. Petersburg, directly for construction, instead of following the normal procedure in use by the admiralty, to gain time. Indeed, the practice was to submit the design to the Naval Technical Committee (MTK) first, for technical evaluation, before being submitted to various yards in a comemtitive manner after funding was secured.

The Baltic Shipyard as a result started work without receiving technical assignment from the MTK just on the personal sanction of the head of the Marine Ministry, Admiral N. M. Chikhachev. it was developed by the ship engineer and senior assistant to the shipbuilder, N. Ye. Rodionov. The result was in contrast to the construction of the contemporary Blake class started in England. it was a constructive development of the Pamyat Azova.

The original specifications submitted by Shestakov no longer exist but most authors and historians today assumed Shestakov intended a very large ship (carrying a lot of coal), enough to travel from “the Baltic to Vladivostok without recoaling” This was ludicrous and the only vessel ever targeting such role was Brunel’s Atlantic-only “Great Western”. The giant ship was built around cavernous holds carrying untold quantities or unrefined coal for a one-way travel. Since the 1850s, steam technology went ahead and fortunately, modern VTE steam engine were dozens of times more effcicient than anything built prior, significantly lowering the quantity of coal needed to travel great distances.

It also appears Shestakov wanted something closer to Pamiat Azova, also to gain time, so basically an upcaled version of the latter, submitted via a constructor from the Baltic Works to the MTK. but that initial design of a 9,000-ton cruiser protected by a 8 inch thick belt armor was rejected by the MTK as impractical, although tensions between Shestakov and the MTK, as well as the General Admiral of the Navy, still Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich at this point, were probably more to point out than pure technical issues.

Features were determined as the following: Ths new ship had to be given an armored deck with only partial side armor over 85 m of hull’s lenght, and 8 inches (203 mm) thick, the citadel ending 20% short to both ends in order to save wieght, a first in Russian shipbuilding practice in order have a light hull at both ends. Still, the hull internals were protected by cofferdams filled with cellulose, whicha also increased side height and closing the extended forecastle. The initial design displacement was estimated to be 9000 tons standard for an ideal total length of 131 m at the waterline, which still surpassed all warships existing at that time. There were to be also two steam engines developed by the Baltic plant, with total output estimated to be over 12,600 shp to ensure a design speed of 18.5 knots, and 2,000 tons of coal supply (20,000 nautical miles at 9 knots). The armament came last and only comprised sixteen 6-inches (152 mm) and a lighter battery of 47 and 37 mm QF guns.

The initial design was further modified by Shestakov, calling a very long warship, over 400 feet (130 m), which was beyond the capacity of any Yard in Russia at the time, and with the same design endurance of 20,000 nautical miles (37,000 km), something completely unheard of for a warship. However his author died in December 1888 and could not argue for his design, which fell through.

Shestakov’s successor, Chikhachev, however had excellent relations with the MTK board: The return Baltic Works design was rejected. Chikhachev submitted his own project to the Yard on June 14, 1888, and to the MTK in July. The MTK proposed this time its own design, larger, 10,000-ton vessel, fitted with an ever better armored belt, 10 inch thick, but operational top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h). It was still much better than any battleship in existence at the time and most cruisers, while still capable of 10,000 nautical miles (20,000 km). The latter helped creating a more balanced design, and still counted on a realistic network of coal depots or support along the way to the east, a range helped by a complete barque rig that could help sparing coal along the way.

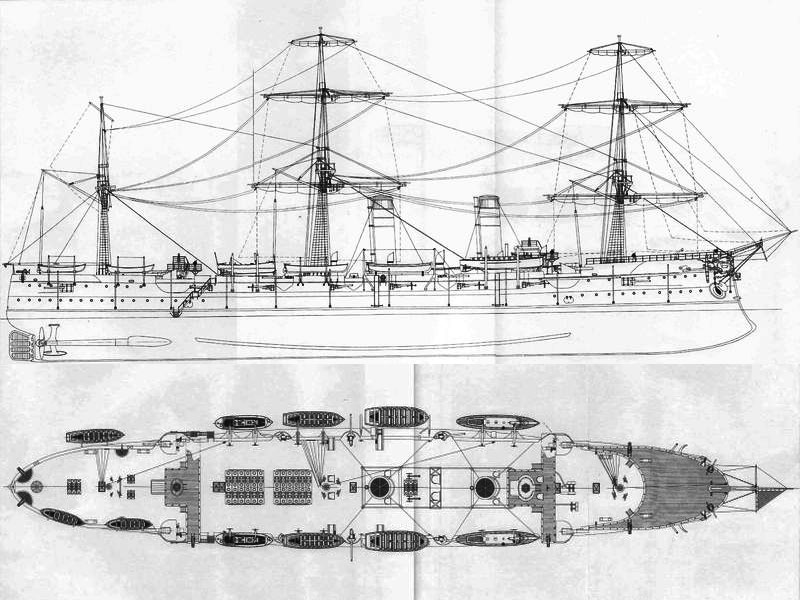

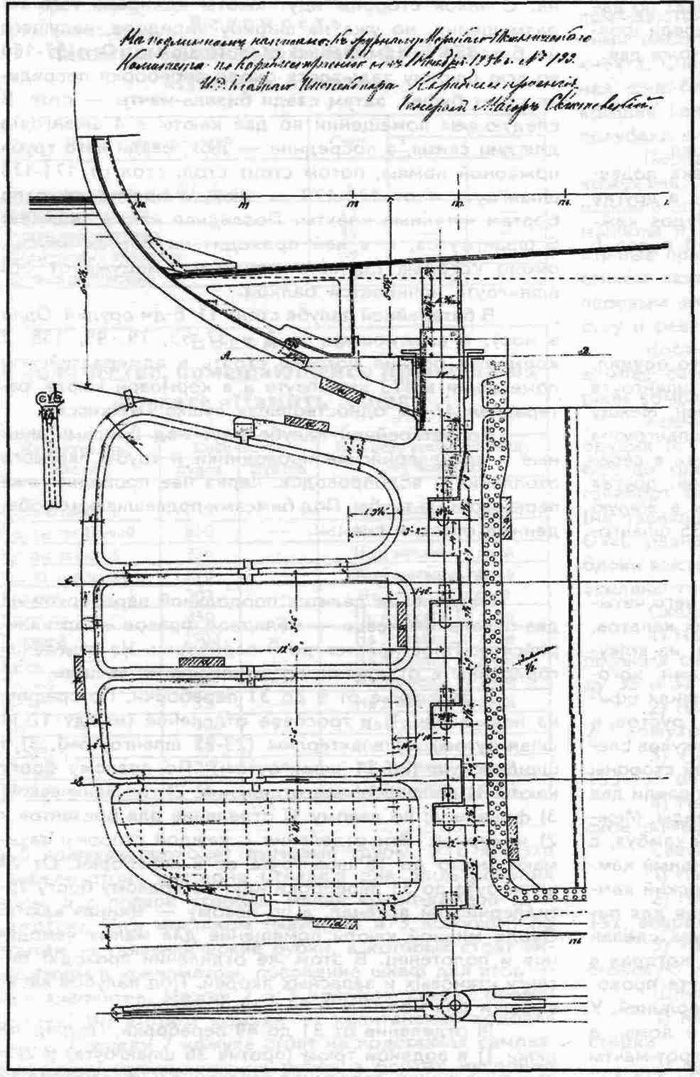

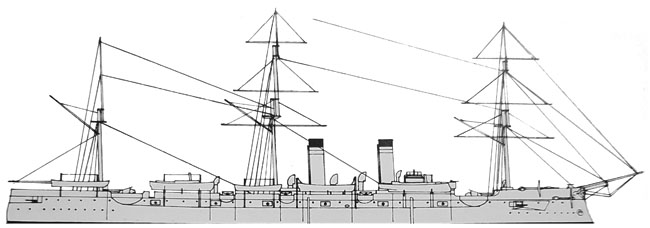

Rurik’s plan

Conclusion of the MTK was based on the opinion of the acting chief ship engineer of St. Petersburg port, N. A. Subbotin. He positively assessed favorably all high design characteristics of the cruiser, writing it as “really desirable for the Russian fleet”, but at the same time referred to contemporary British cruiser building in its excessive increase in the length and hull elongation, in need of significant strengthening of the structure and, therefore mass, to the detriment of combat characteristics like top speed. The MTK specialists also argue there were limited docking capabilities in Asia for a 130-meter cruiser, the only drydock nearby being at Yokohama, but also cramped roadsteads. It was also argued that cofferdam compartments flooded increased frictional resistance, provoked excessive roll and insufficient stability on this tight waist design. MTK pointed out the inevitability of an increase in armor weight also due to the longer hull. MTK proposed another design, still comprised within displacement limits of 9,000 tons.

Ship engineers from the Baltic yard present at the meeting object MTK, and N. Ye. Titov associated with N. Ye. Rodionov, the author of the project, as well as M.I. Kazi, Baltic shipyard director. The latter adressed a letter to the MTK chairman in November 18, 1888, arguing that, with the construction of Pamyat Azova, the shipbuilding department of the MTK ignored British statistics and missed the proposal of the Baltic Shipyard to dramatically increase the hull’s absolute length. Calculation carried out by the Baltic Shipyard showed the Rurik’s hull was equal in strength to HMS Duke of Edinburgh, 27% stronger than the Admiral Nakhimov, drawings and specifications of which were entirely the product of MTK. According to data obtained from the British Imperieuse and Warspite, strength calculations should not be in doubt.

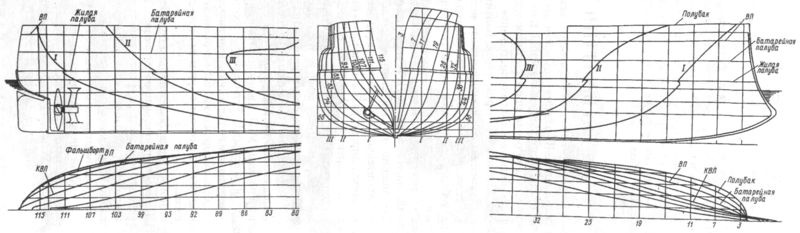

Hull’s water lines

The experience of creating ocean-going mixed steamers confirmed that only lenghty steam vessels were capable ocean crossings with high average speeds. They also argued that the MTK were wrong in their assessment about load distribution for commercial steamers for strength was very different from warships, overloaded at the ends with artillery and armor. Civilian ship’s loads for example was way more unstable than on warships, causing even higher hull stresses. Lloyd’s Register rules even stipulate more robust hulls for commercial steamers. In conclusion, M.I. Kazi, proposed to the MTK to develop new Strength standards for Russian military ships, more accurate due to the nature of their purpose.

MTK in the end however left all Kazi’s arguments unanswered. The i=office, in their publication No. 149, November 28, 1888, repeated all their objections to elongation of hull, taking as an aexample Pamyat Azova’s own completion which did not yet proved its strength in practical sailing. They warned the admiralty that if they nevertheless agree with Baltic Shipyard’s own scheme, the hull’s practical displacement with all fittings and fully loaded, would increase by 42% instead of the Yard’s own figure of 34%, so reaching 10,000 tons. As a result, Admiral-General Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich proposed the Baltic plant project being rejected, development now being completely entrusted to the MTK.

For the name, Rurik soon made unanimity, as the founder of the Kingdom of Kiev and of the Rus’. Plans were approved in 1889 by Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich and submitted back to the admiralty works. Construction started in 1890 at Baltic works, just completing its new drydock. Powerplant issues proved to be the toughest point, but were ultimately solved by technical designers at the Baltic Works.

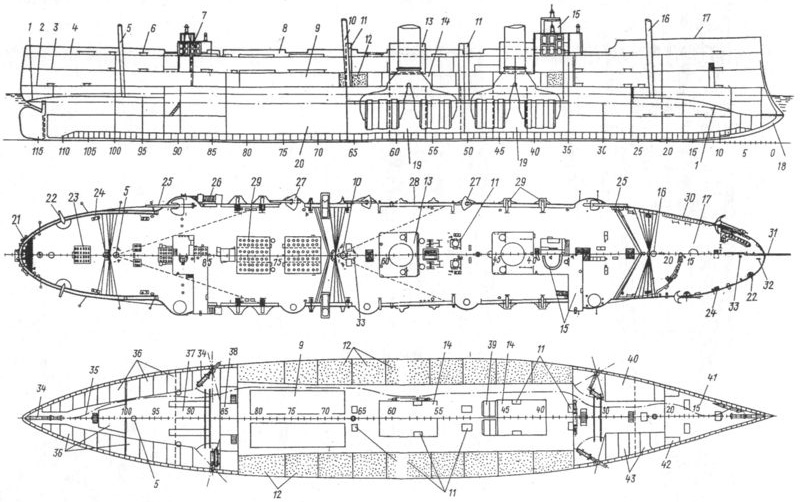

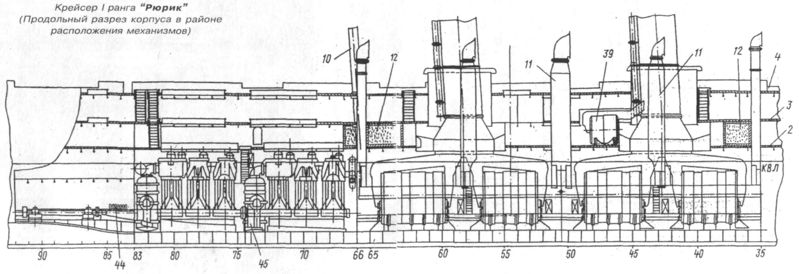

Final design of Rurik (Summer 1888)

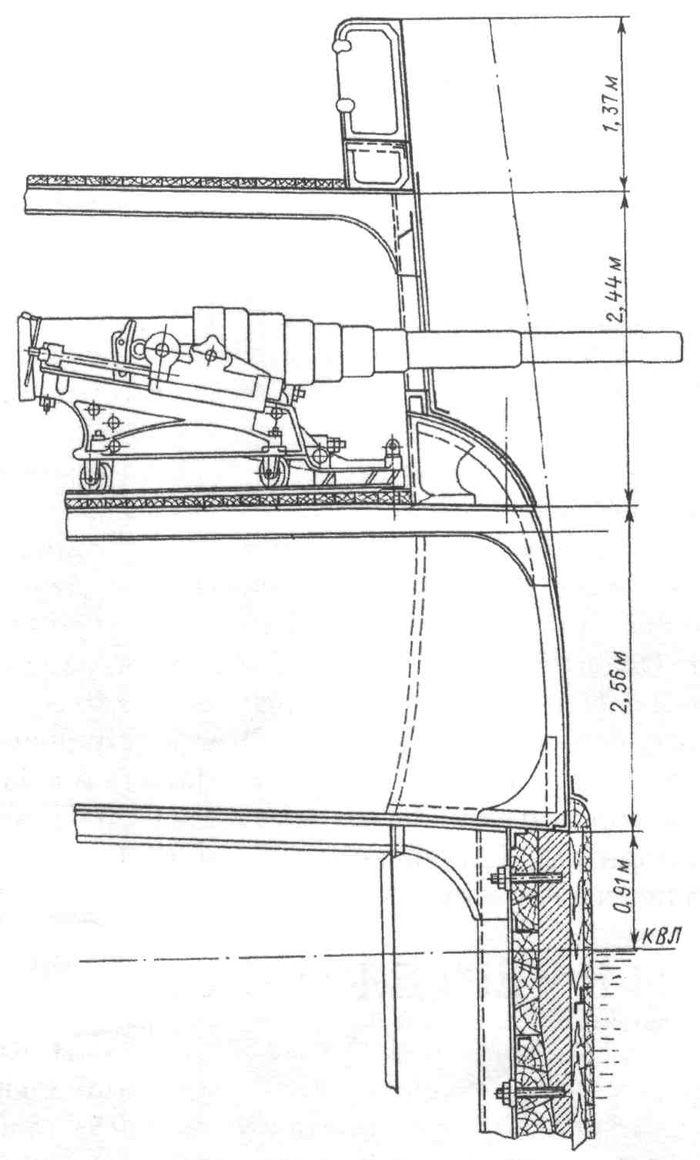

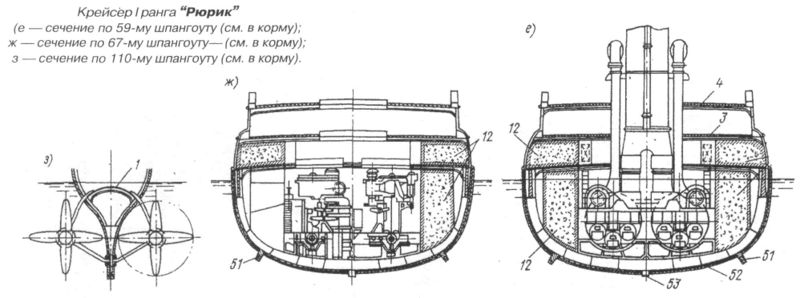

Steering, final design

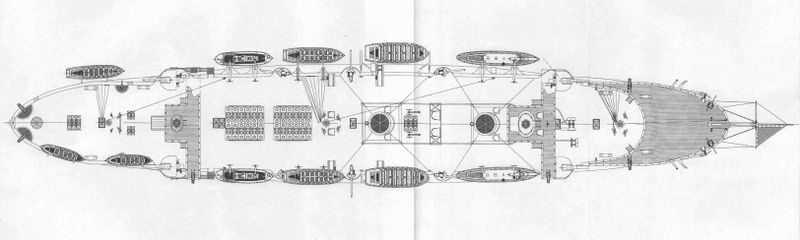

Top view and artillery arcs

Armor Protection cutout, battery deck

Internal details

machinery space cutout

Machinery space details, aft.

The final MTK design was drafted under the leadership of N. E. Kuteinikov, which opinion towards proposals of the baltic Yard started to shift, and revised the initial draft design, with two displacement options, at 9,000 and 10,000 tons. By mid-January 1889, both projects were completed and on January 17, 1889, a discussion took place in presence of invited representatives of the admiralty. On May 25, 1889, the final discussion, led to accept final characteristics of the cruiser which featured the following:

-Design displacement of 10,000 tons.

-Overall length reduced from 130.6 to 120.8 m.

-Waterline lenght reduced from 128.4 to 118.9 m.

-Greatest beam increased from 18.6 to 20.4 m.

-Average draft increased from 7.5 to 7.9 m.

-Hull ratio established to 5.8 instead of 6.88

-Relative hull mass assumed to be 40% of the displacement.

-Powerplant decreased from 12,600 to 12,250 hp, sufficient for 18-knots.

-Coal reserves decreased by 200 tons at 1528/1917 tons.

-Same protection scheme but without the armored deck, but 10-in belt instead of 8-in as in Admiral Nakhimov.

-Artillery unchanged.

-Sailing capacity kept minimal, to just keep some mobility at sea, cruising when wind favourable.

On July 1, 1889, no less than ten blueprints, pre-approved by Emperor Alexander III, were sent to the General Directorate of Shipbuilding and Supply to place an order for construction. On July 20, 1889, final specifications were prepared.

Hull construction and specificities

The final cruiser’s hull design was based on previous Russian armored cruisers, emphasised autonomy and seaworthiness at the expense of other characteristics, notably speed. They were meant as raiders in the Pacific Ocean, based in Vladivostok, with possibly also Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky only. Likelihood of meeting strong opposition in the Pacific was slim, therefore speed and firepower were to be sacrificed in favor of range and protection.

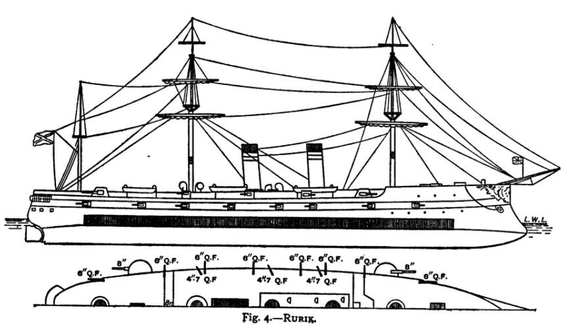

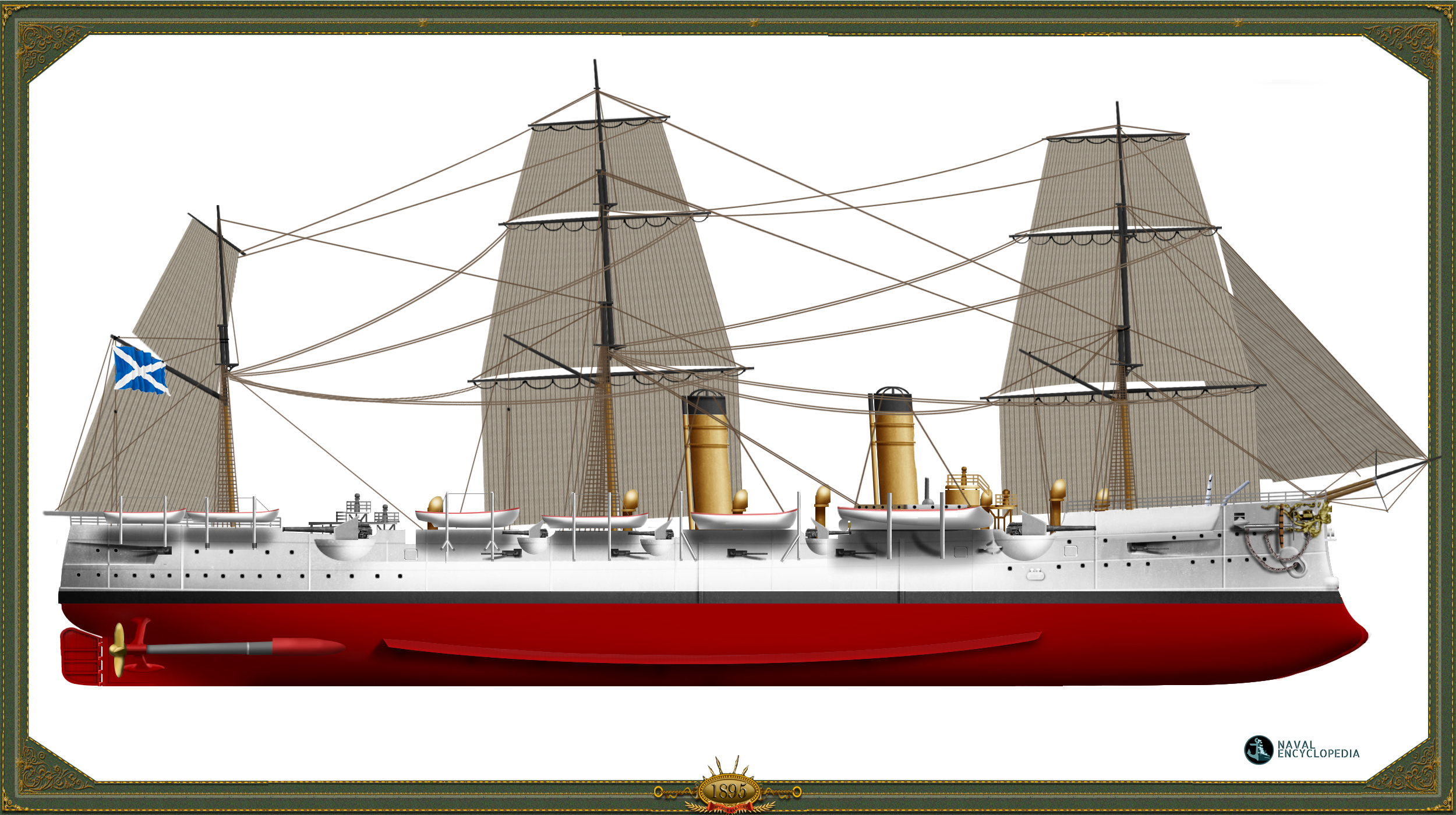

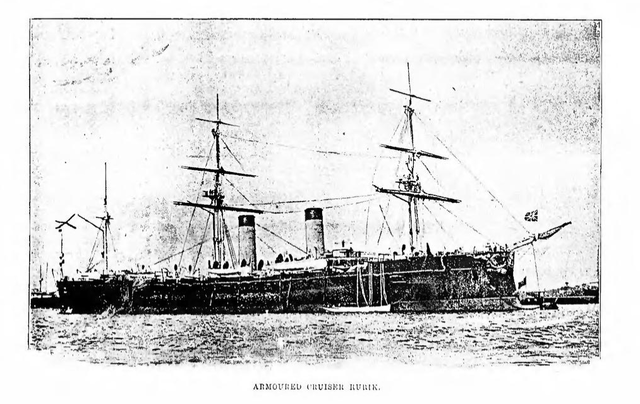

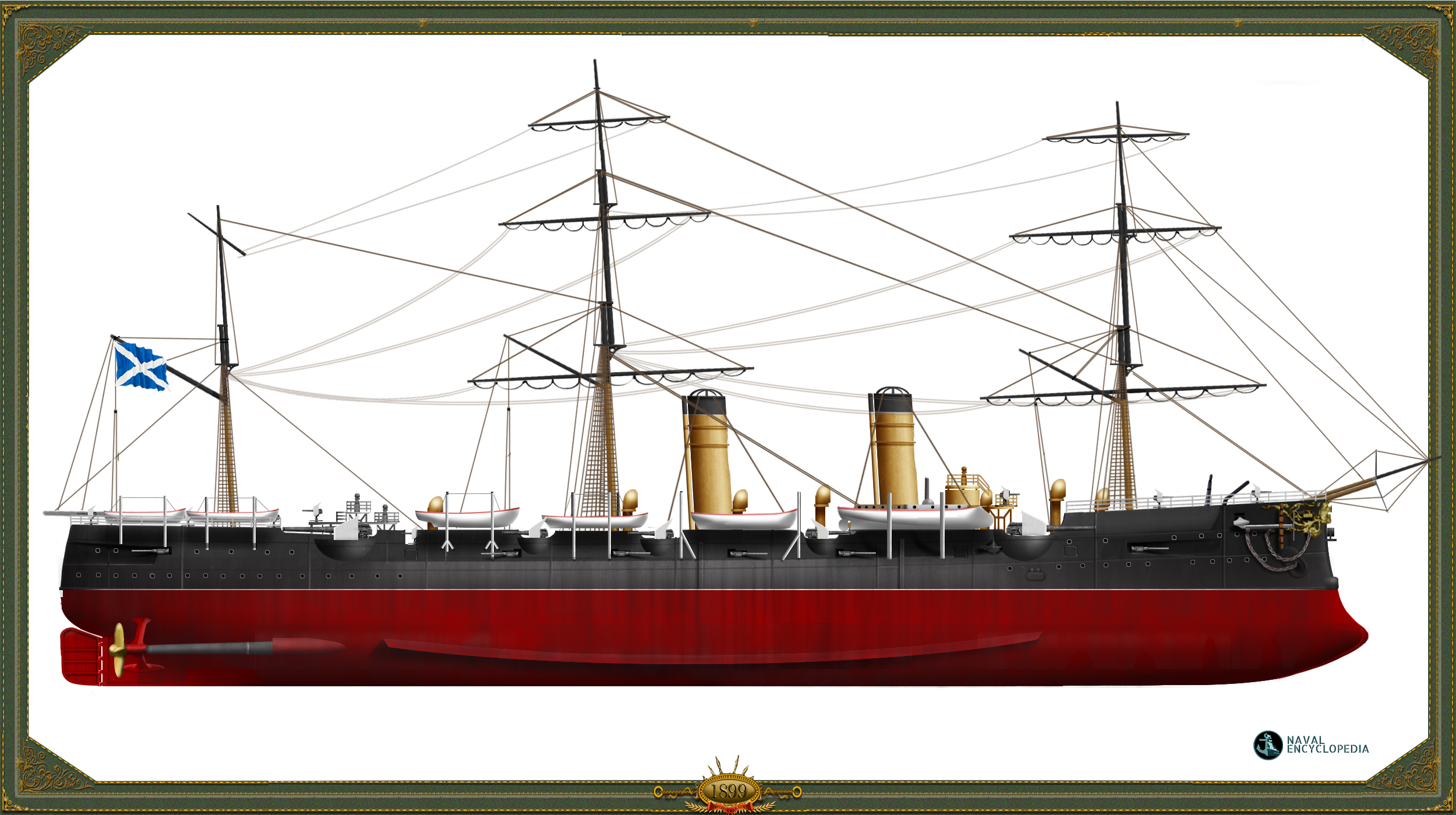

Rurik’s hull was given a large, pointy ram, and she was also one of the last large cruiser of her generation to have a fully rigged sailing scheme, with a fore, main and aft masts, two fore square sails and a brigantine. It was assumed that sails make possible to save coal in long crossings when practicable, but in practice they turned out to be completely useless and not adopted for Rossia and Gromoboi. Rurik’s hull was tall, with a raised forecastle improving her seaworthiness, which as later assessed by the crew, was excellent. The steam propulsion however later appeared not to be powerful enough, top speed sticking to 18 knots. There were some extra bracing frames at three places along the hull, which was pierced only by small apertures for secondary guns to keep its integrity.

Powerplant

It was all Russian made, with 2 shafts (large brone propoellers, diamatere unknown), driven by two vertical triple-expansion steam engines in teh British fashion, fed by 8 cylindrical boilers. They were rated for a total of 13,250 ihp (9,880 kW) in normal draught. This was enough for a specified top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), although more was achieved in sea trials.

Range as designed was 19,000 miles at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), and at full speed it was reduced to 2,300 miles.

Protection scheme

Along the waterline, the amidship hull section was well protected, with an armored belt in steel-nickel armor, ranging in thickness from 127 (5 in) to 254 mm (10 in). The belt itself rested on a 37 mm thick convex armored deck, covering everything below the waterline, up to 3 inches (76 mm) on the slopes. At the ends of the belt however, the citadel was closed by transverse bulkheads 8 inches (203 mm) thick. Outside the citadel, only the forward conning tower was armored, with walls 6 in (152 mm) thick.

Rurik’s artillery was located entirely above the citadel, in completely unprotected sponsons on the main deck. Only the 6 in (152 mm) guns in the battery had at least some structural protection. But in sponsons, neither the gun servants or their ordnance was protected, open to plunging fire and shrapnel. This had dire consequences, since her firepower was soon knocked out at Ulsan, and she was reduced to her ram and torpedo tubes, steering halph-hazardly with her shafts only.

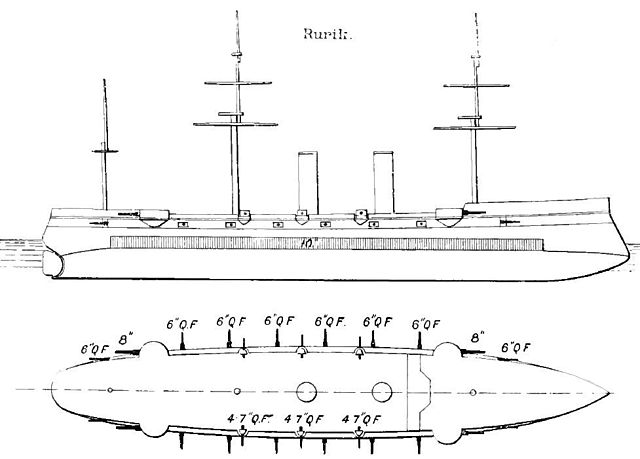

Armament

1892 drawing of Rurik.

Main: Four 8-in/35

The 8″/35 naval cannon (203.2 mm) gun was developed by A.F. Brink, produced by Obukhov. It was adopted by the Navy in 1885 and equipped the armored cruisers Admiral Nakhimov, Pamiat Azova and the Koreets class gunboats, seeing action in the Russo-Japanese War. Barrel weight 13 tons and 710 kgs, shell weight 87.8 to 133 kgs depending on the type, AP or HE, muzzle velocity from 583 to 663 m/s, max range 9,150 meters at +15° elevation. On Rurik, they were placed in barbettes on the four corners of the hull, fore and aft, as customary for 1880s ships. They were low enough as not to compromise the stability if they had been placed higher up, but in 1895, this was an obsolete configuration, notably looking at twin turrets British ships.

Secondary: Sixteen 6-in/45

This was a naval rapid-fire, medium-caliber gun developed in the 1880s by French firm Forges & Chantiers de la Mediteranee, designed by Gustave Canet. First entered service in the French Navy in 1889. Rurik became the first Russian ship armed with it, adopted by the Russian fleet on August 31, 1891.

It was a popular alternative to the classic Vickers 6-inches of the time. Total mass 14 tons, 690 kgs. Barrel length, 6858/45 mm, Barrel weight with breechblock 5,815 to 6,290 tons, shell weight, 41.4-49.76 kgs, muzzle velocity 229-793 m/s, unitary or separated propellant charge, rate of fire 7-10 rpm, recoil course 375 – 457 mm, max elevation +20°, range 11,523 m. They were placed along the hull in recesses fore and aft, and in barbettes on the main battery deck. Due to their exceptional range, better than the main guns, they were used as complement in between reloads: The 8-in fired at 3 rpm of average, double that with the Canet guns.

Tertiary: Six 4.7-in/45

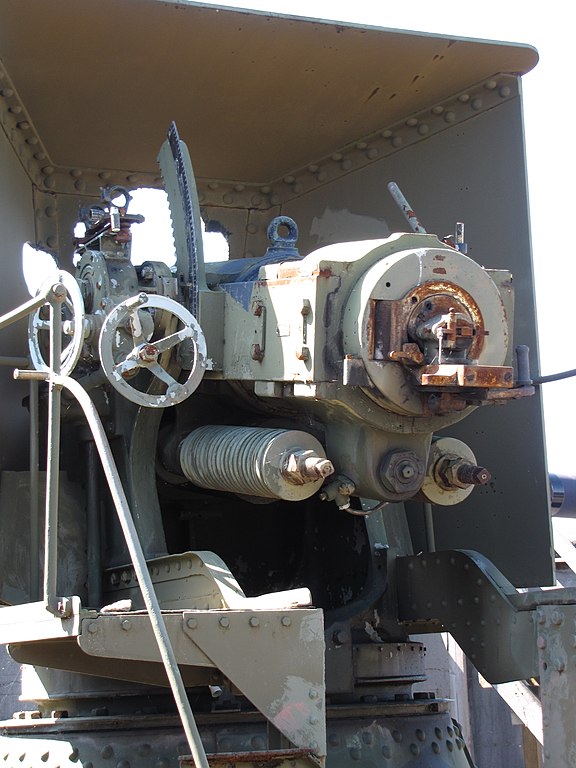

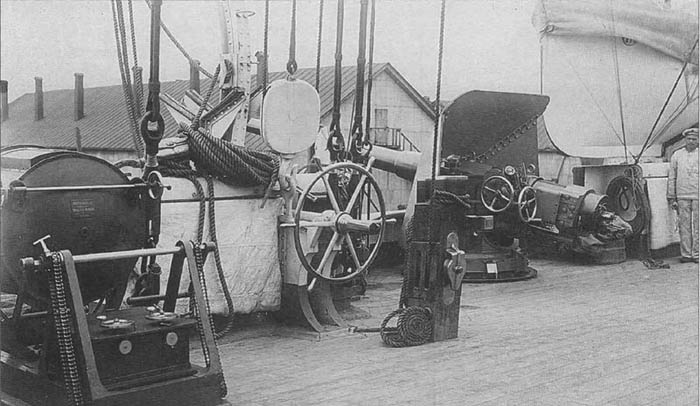

Deck Canet gun, under mask.

Although this seems tp complicate the battery with a very close caliber, Rurik also carried six 120 mm guns in open sponsons. They were also Canet guns, manufactured under license in Russia by Obukhov and Perm. The agreement was signed on August 10, 1891 and it was adopted in 1892, mostly for battleships: Emperor Alexander II class, Tri Svititelia, Admiral Senyavin class as well as the cruisers Rurik, Dmitry Donskoy, Vladimir Monomakh, Zhemchug class, Novik, Boyarin, Almaz, Gilyak class gunboats Kars and Lieutenant Shestakov class destroyers. They had a long service life, were faster-firing (12-15 rpm) even than the 152 mm and about the same range.

Barrel lenght 5400/45 mm, weight 2952 to 2989 kgs, shell 20.41 – 28.97 kgs, single cartridge style charge, muzzle velocity 686 – 823 m/s, max range 11,306 at +25°. They also served in WW2 in coastal positions.

Light: 47 & 37 mm, HMGs

75 mm gun onboard after Rurik’s rearmament.

In total, the ships carried officially six Hotchkiss 47 mm QF guns and ten 37 mm, also Hotchkiss. Similar to those used on other navies and placed on the decks and fighting tops. According to British sources, they were also armed later with a complement of twenty-two small Q.F. guns of the 3 pounder and 1 pounder type (20 mm), also presumably on fighting tops or dismountable for landing parties, two also fitted on the steam cutters.

Light gun deck, masked.

Torpedoes: Six 381 mm models

One in the surface bow tube, a chase stern tube, two hull broadside tubes and two underwater. These were likely if the 1876 15″ (381mm) Whitehead model, carrying a 57 lbs. (26 kg) warhead to a range of 440 yards (400 m) at 29 knots. Still in use before the introduction of the 1898 model, a locally built variation.

Rurik specifications as built |

|

| Dimensions | 125.6 x 20.4 x 9.1m (412 x 67 ft x 30 ft) |

| Displacement | 10,950 long tons (? t) standard |

| Crew | 768 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts 2-cyl. VTE, 8 v.boilers, 13,250 ihp |

| Speed | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 19,000 nmi () at 10 knots, 2000 tons coal |

| Armament | 4 x 8-in (203 mm), 16 x 6-in (152 mm), 6 x 4.7-in (120 mm), 6 x 47 mm, 10 x 37 mm, 22 x 1-pdrs |

| Armor | 8-12 in belt (305 mm), 2-3 in (76 mm) deck, CT 6-in (152 mm). |

Reception and the anglo-russian naval arms race

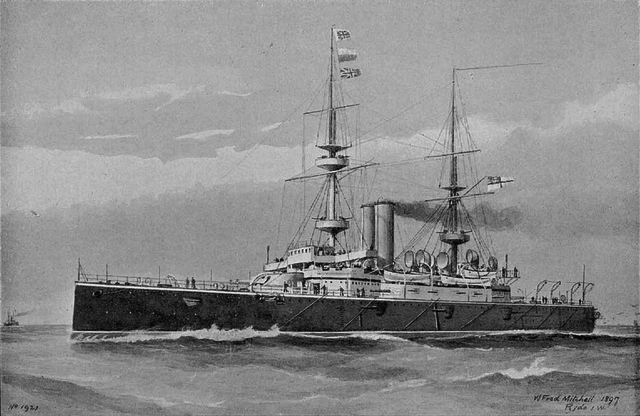

The gargantuan Powerful class cruisers

The Centution class, which answered the support battleships of the Pereviet class.

As plans of Rurik were being finalised, Britain had glimpses and rumors about the new design and became exceedingly nervous about it. It feared, as it was already conceced by the Russian themselves, that it would threaten her large commercial fleet not only in the far east, but Indian ocean as well, due to its long range. The British press further fuelled this anxiety, to the point it reached paranoia. In return, the Royal Navy admiralty itself grossly overestimated the threat posed by Rurik, so to trigger in effect, a naval arms race (but also test the envelope by building “super cruisers”).

Indeed, the house of commons and the opinion put pressure on the Royal Navy to find a solution quickly, and the admiralty responded in building two “cruiser killers”, two new armoured cruisers, HMS Powerful and Terrible. These became in effect when completed the largest warships in the world. But since after the construction of these cruisers the Russians decided to support them with dedicated, fast battleships, the Peresvet class, the British replied in turn with ships derived from battleships but rather comparable to proto-battlecruisers, producing the second-class battleships of the Centurion class, and Renown, after the announcement of the construction of Oslyabya, the third of the Peresvet class.

The British cruisers were absolutely massive, and turned out to be much faster at 22 knots, using watertube (or coil) boilers, which later were proven superior, becoming a standard for all new warships. They were also better armed and better protected, as well as the following Rossia and Gromoboi. The result of this 1890s frenzy however was costly for the British taxpayer: Both the Powerful class cruisers and Centurion class battleships had a short span useful service life. The Centutions were even discarded before WWI, while the Russian threat has been completely deflated. The 1902 strategic alliance with Japan, which own navy was massively backed by the Royal Navy, followed by the Russo-Japanese war, achieved to make this earlier Russian threat completely irrelevant.

Ryurik in action

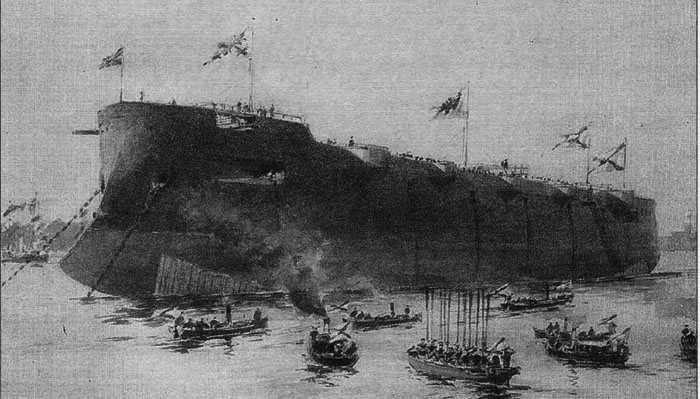

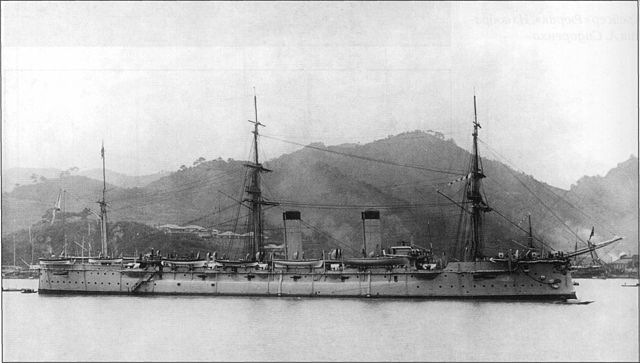

Launch of Rurik in 1892

In service: Marine Company at stand

Rurik was built at Baltic works, laid down on 31 May 1890, Launched November 1892 and commissionedin May 1895. Her captains were Enegelm, Fyodor Petrovich 1890-1891, during construction, Pavel Nikolaevich from 1891 to 1894, Krieger, Alexander Khristianovich 1894-1896, Rodionov, Alexander Rostislavovich 1896-1897, Haupt, Nikolai Alexandrovich 1897-1900, Matusevich, Nikolai Alexandrovich 1900-1903 and her final wartime captain Evgeny Aleksandrovich Trusov, from 1903 until she sank.

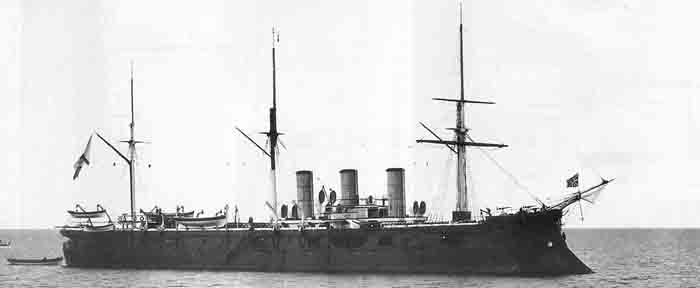

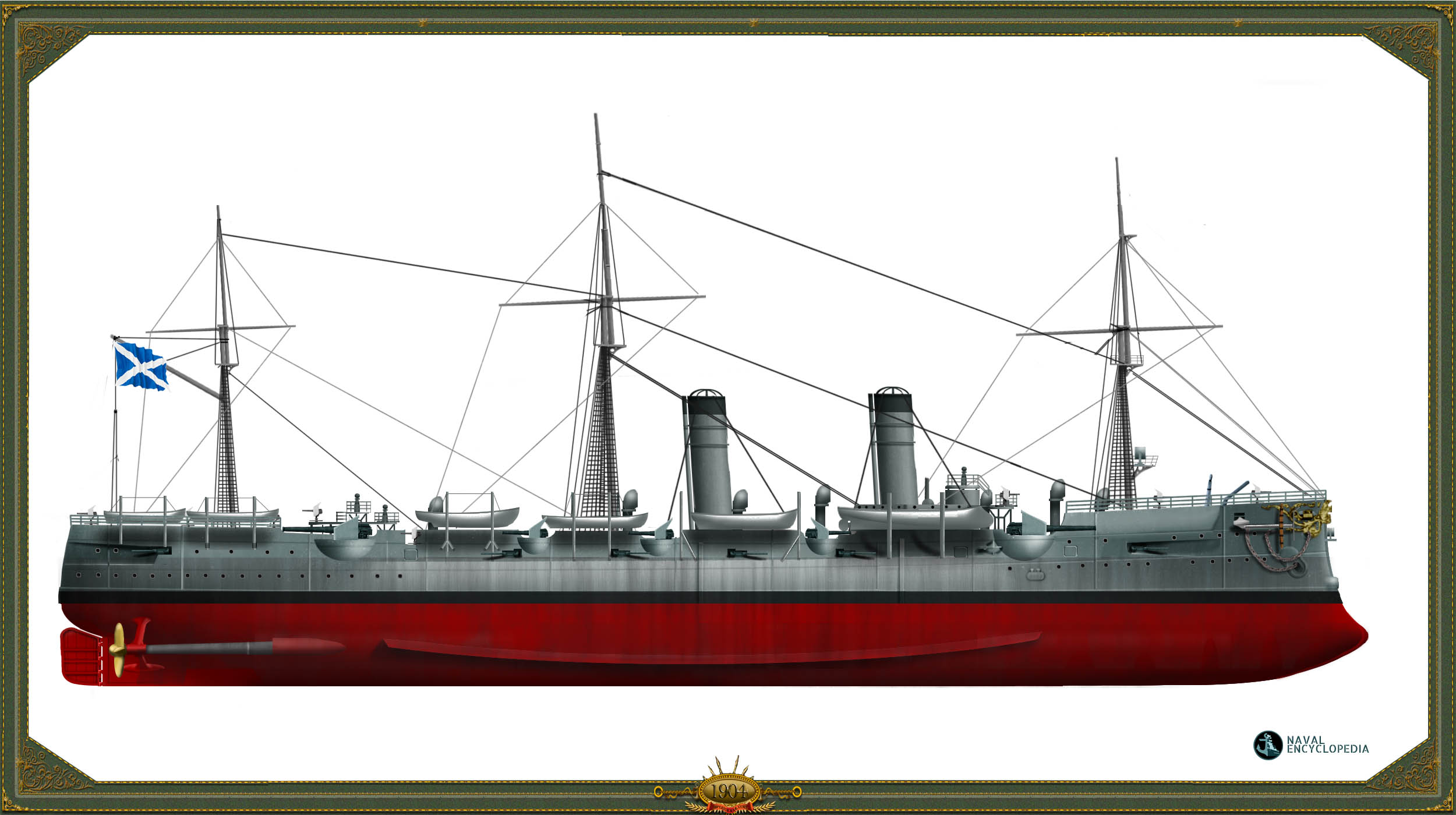

Rurik, after her training cruise in the Baltic, headed for the Russian Pacific Fleet in Vladivostok under command of Admiral Fyodor Dubasov. The latter, after she arrived in the pacific squadron, recommended modifications after short service here: Her poor steaming performances had her reboilering, and her rigging was found as hingerance and entirely removed, along with ropes, capstans, leaving only the bare masts at least to hoist combat ans signal flags. The reboilering project however never was carried out due to limited capacities and the absece of suitable boilers to do the job.

Rurik, after her training cruise in the Baltic, headed for the Russian Pacific Fleet in Vladivostok under command of Admiral Fyodor Dubasov. The latter, after she arrived in the pacific squadron, recommended modifications after short service here: Her poor steaming performances had her reboilering, and her rigging was found as hingerance and entirely removed, along with ropes, capstans, leaving only the bare masts at least to hoist combat ans signal flags. The reboilering project however never was carried out due to limited capacities and the absece of suitable boilers to do the job.

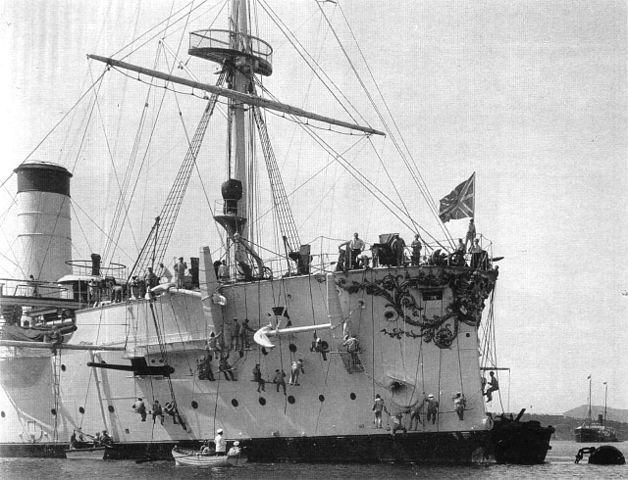

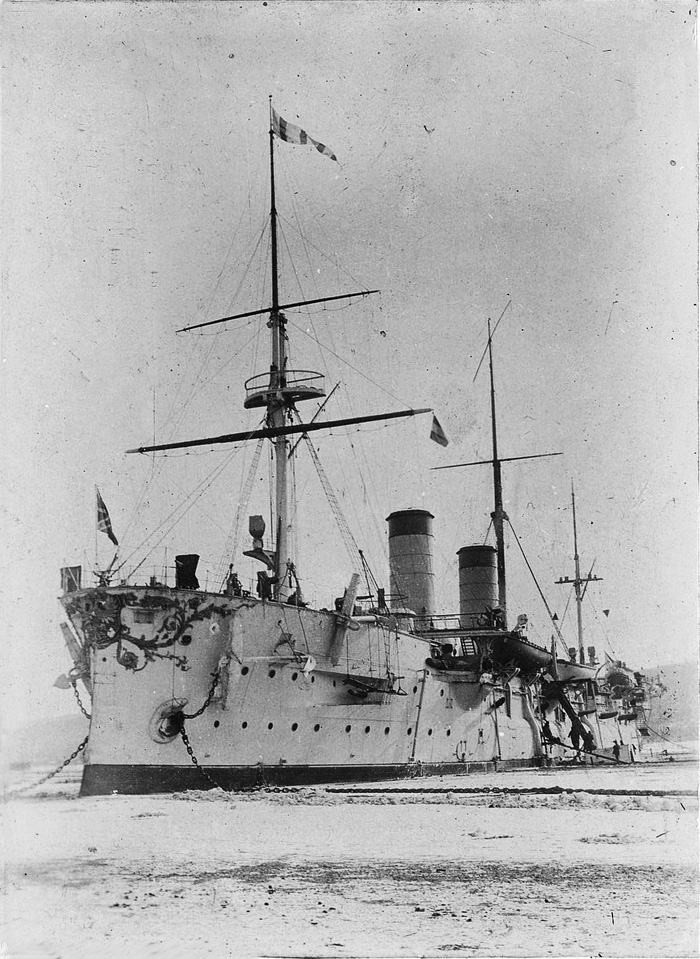

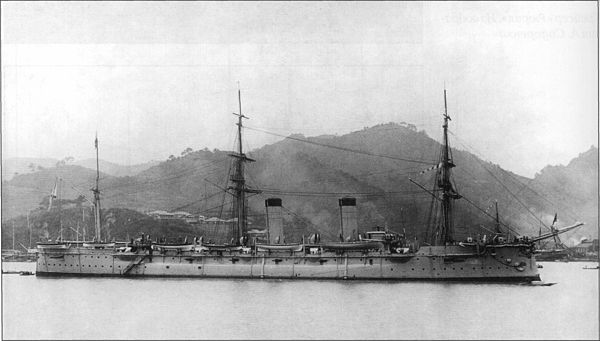

Stern view of Rurik at tsingtao

Her 1896-1904 years are no recorded in detail. Rurik soon took a routine of summer and autumn cruisers and fleet manoeuvers, going south for the latter, probably as far as the south China sea, and visiting many ports in between. She visited for sure Nagoya and Hakodate, but also the German colony of Tsingtao. Each year also she was drydocked in Nagasaki for full maintenance, since there was no drydock large enough for her in the whole region.

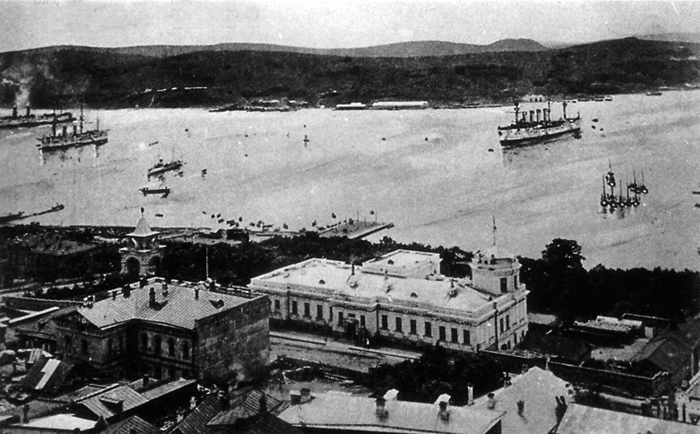

Rurik and Gromoboi in the Golden Horn Bay (Zolotoy Rog), Vladivostok.

Rurik off nagazaki before 1904.

Prow of the ship, with a crew busy cleaning her/repainting the hull.

Prow of the ship, Vladivostok winter. Lhe late 1890s or early 1900s

The Russo-Japanese war

Rurik and the rest of the fleet in Vladivostok

When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, Rurik was not alone in the Pacific Squadron, but with Rossia, Gromoboi, and Bogatyr, which she trained with for many years, in Vladivostok. All these cruisers as tensions were high with Japan, charged with their initial commerce raiding task, of searching and destroying Japanese merchant traffic in the Sea of Japan and off the coast of the home islands. By August 1904 however, only one vessel was spotted and sunk, while the Imperial Japanese Army already moved siege artillery on the hills of Port Arthur. The siege kept the battleships of the Pacific Squadron trapped into the port, after failing to breakout repeatedly.

Battle of Ulsan

Rurik in Feb-March 1904, painted medium grey, with reduced rig and new 3-in light guns.

On August 14, 1904, the cruiser Vladivostok squadron advanced to join the 1st Pacific squadron’s battleship during another attempt to breaking through the siege, to be met in the Korean Strait by a Japanese squadron of four armored cruisers, Iwate, Izumo, Tokiwa, Azuma, and two other protected cruisers. Under command of Vice Admiral Kamimura Hikonojō in the Tsushima Strait, it was purposedly waiting between Korea and Japan. Japanese armored cruisers were better than the Russian in firepower and protection, and when they met their Russian opponents, the latter turned out to be in a bad position to fire, with opposite force in 8-inch guns of 12 vs. 16, and soon due to manoeuvers fell to 6 vs. 16. Bogatyr was left behind during the battle, having received damage due to grounding.

Rurik in the Scientific American Vol 91, N09 August 1904, in black paint, before she was camouflaged grey in 1904.

This, in combination with a generally better rate of fire and more powerful shells, played their part in their own salvoes by 4-5 times, the Japanese firing HE and the Russian firing armor-piercing shells of the French type with a much smaller explosive charge. The melinite charge used by the Japanese however did not surpass much the Russian pyroxylin explosion energy with a ratio of 3.4 MJ/kg versus 4.2. For observers of the battle nevertheless, the Japanese hits looked very “spectacular”. Another factor which played a part in the battle was the Japanese using armored towers, versus Russian half-open casemates. Also choice in armor schemes had the Russian ships unarmoured at the extremities, and on Rurik herself, the otherwise aft rudder compartment’s cover was inexistant.

Due to the rapid show of firepower superiority by the Japanese, it was decided to withdraw back to Vladivostok. At 5:30, while starting her retreat, Rurik received a hit in her stern, below the waterline, flooding the steering compartment. She slowe down and went out of formation and at 6:28, in response the flagship enquiry answered by signals her rudder was jammed. From then on, Rurik became a stitting duck. Caught up by the whole Japanese line, she was pummelled, volleys destroying her and steering completely. Although the crew managed to regain some control for a time, by an unfortunate turn of event, another shell penetrated just at the tight place to jam the steering blade at the starboard side, so she ship was now condemned to turn in cicles.

Her captain tried had to have her staying on course, by playing with the opposite shaft’s revolutions, or even rerverse it but she became completely separated from the detachment. Nevertheless, this did not prevent her gunners to keep the enemy at bay with a vigorous and accurate 8-inches barrage, and with the other guns, inflicting heavy damage on IJN Iwate. Nevertheless she soon lost three 6-in, one 3-in guns on the starboard side, with 40 killed. Admiral Jessen eventually ordered Rossia and Gromoboi to cover Rurik. They came back and tried to interpose, eventually pushing back the Japanese.

This diversion cost them dearly as they came under heavy Japanese fire, taking punishment and casualties, until being forced to leave the battle, leaving Rurik to fend for herself. At 8:20 am, the flagship ordered the line back to Vladivostok, trying to keep the Japanese armored cruisers on their tail, hoping that Rurik could fight off the remaining light armored cruisers and ultimately correct the damage and resume her trip back. Or possibly to reach the Korean coast. The Japanese indeed chased the Russians as expected bu soon ran out of shells and at 10:04 Kamimura decided to stop the chase and turn back.

Menawhile, Rurik still could not recover steering control, and maneuvered by varying shafts revolutions between shafts to try to keep some stright path but her firepower by that time was significantly weakened. Soon, the Japanese closed in on her for the finish. With their remaining shells, and closing each time, they methodically destroyed all remaining gun positions while Rurik’s captain ordered to raise steam and achieve greater speed. At some point she even turned to attempt a ramming, and started to fire her working torpedo tubes. Evading, the Japanese cruisers retreated at a safer distance, but went on shelling her nonetheless. After a while, the Russian cruises fell silent, and after listing by the stern, as the Japanese approached, they could saw Rurik sinking. Indeed, as the cruiser’s firepower was gone, and out of 763 crew members, 204 were killed, including the commander captain 1st rank E. Trusov, senior officer captain 2nd rank N. Kholodovsky, and 305 injured. The senior surviving officer, Lieutenant Ivanov, ordered the ship to be scuttled. The Japanese only arrived to pick up about 625 survivors. The remaining two Russian cruisers escaped back to Vladivostok, joining there Bogatyr. They will be no other attempt to save Port Arthur, which now rested with the “second pacific squadron”, en route.

General assessment of Rurik

Commemorative stamp of the battle

Despite her obsolete look with open barbette guns, barque rigging and ram, Rurik performed surprisingly well at Ulsan. She covered in effect the other two Russian cruisers, less some Japanese indecisiveness. Even the late battle ramming and torpedoing attemps reached the desired effect, of scaring the Japanese away, which went back to a sporadic, but less accurate fire on a well protected cruiser. But Rurik’s sacrifice at Ulsan further weakened the 2nd Pacific squadron’s chances to relieve Port Arthur. Rossia and Gromoboi would not hope to defeat the Japanese, especially with Bogatyr having permament grounding damage. Gromoboi never sortied for the rest of the war. Nevetheless, the “Rurik’s heroic last stand” was an inspiring story in the Russian Navy and it was certainly not at random that the last and most powerful armoured cruiser of the Russian Navy ever built, retook the famous name: The 1906 Rurik

Conway’s profile

Author’s profile: Rurik 1895, in white livery.

Rurik in overall marine green-grey, battle of Ulsan, 1904.

Read More/src:

Books

Conway’s all the world’ fighting ships 1860-1905

Schrad, Mark Lawrence (2014). Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State. Oxford

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Brook, Peter (2000). “Armoured Cruiser vs. Armoured Cruiser: Ulsan 14 August 1904”. Conway

Frampton, Victor; Head, Michael; McLaughlin, Stephen & Spurgeon, H. L. (2003). “Russian Warships off Tokyo Bay”.

McLaughlin, Stephen (1999). “From Ruirik to Ruirik: Russia’s Armoured Cruisers”. Conway

Warship International Staff (2015). “International Fleet Review at the Opening of the Kiel Canal, 20 June 1895”.

Watts, Anthony J. (1990). The Imperial Russian Navy. London: Arms and Armour.

Taras, Alexander (2000). Ships of the Imperial Russian Navy 1892–1917, Library of Military History

Links

Russian_cruiser_Rurik_1892_Jane

Получить печатную версию этой книги

On Russian torpedoes before WWI

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign