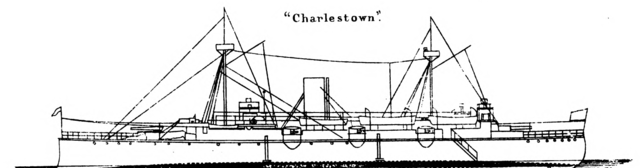

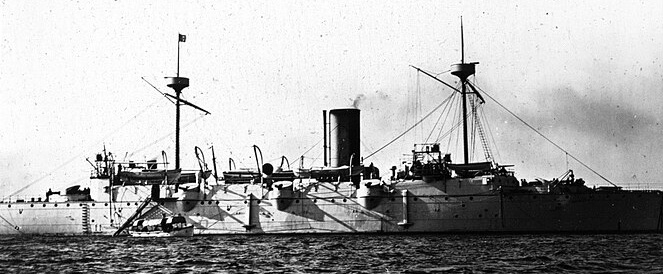

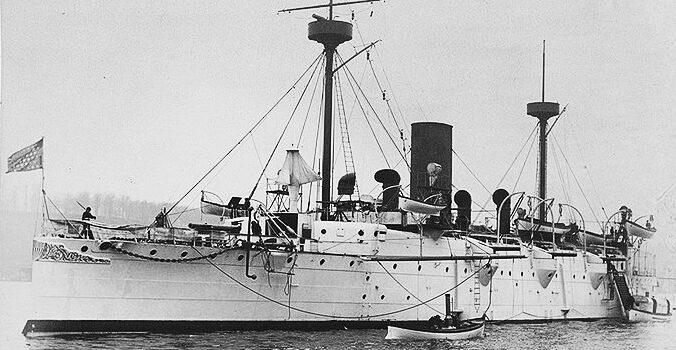

USS Charleston (C-2) was the second British-designed cruiser (after Baltimore) in the early years of the “new navy”, purchased from Armstrong, Mitchell and Co. in Newcastle to follow the “ABC” cruisers with better protection, higher speed, and similar armament but as a way to keep up with the latest techniques in naval tech and construction. She virtually a copy of the excellent Naniwa class (1885) prepared by William White with US specifics. She was launched on 19 July 1888 at Union Iron Works in San Francisco, and commissioned on 26 December 1889, but her career was short as she was wrecked in 1899, Grounded 2 November 1899 near Camiguin Island, Philippines and abandoned after taking part in the Philippines campaign of the 1898 Hispano-American war.

Charleston in Hong Kong, 1893

Development

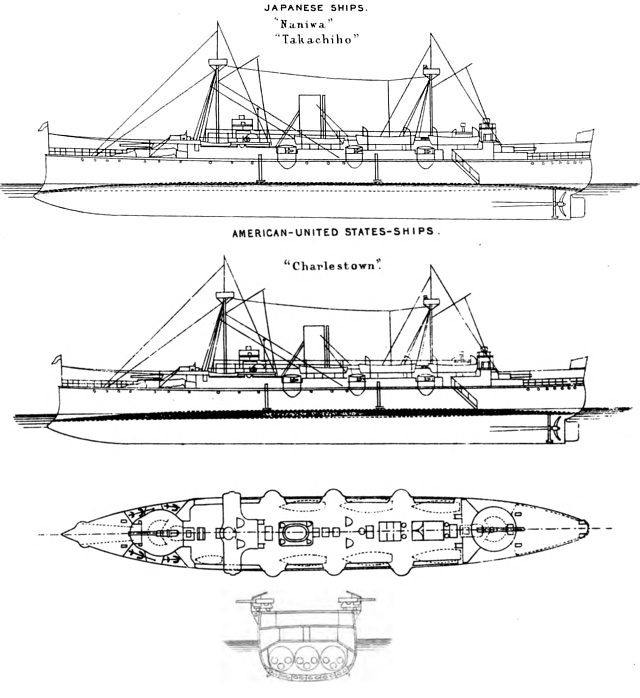

Comparison between the two cruisers (1887 and 1888 Brassey’s editions)

After the completion of the first “ABC” cruisers, the Atlanta class, USS Boston, and Chicago intended for commerce raising or coastal defence, the US admiralty recognised some deficiencies in cruiser design and wanted to stay up to date with the latest European trends in construction and design. They turned, with a commission and via the naval attaché in London from 1886 to the best Yard at the time, building dozens of cruisers for many countries across the globe. Armstrong was the world’s largest shipyard, and its chief engineer at the time, William White, was also the general manager of Armstrong Whitworth in Elswick.

It was decided to adopt the design of Japanese protected cruisers, the Naniwa class just launched in 1885. Just like the US, Imperial Japan was building up its navy. USS Baltimore also was built to modified Armstrong plans, but Charleston was even more faithful to the original. Adapting her propulsion machinery to US standards and practices was however difficult. It was combination of components of several different plants and the Yard assembled them the best it could, but they were proved troublesome. She failed to reach her designed speed and fearing penalties, Union Iron Works made costly changes in order to complete her up to specs and reach her designed speed.

She was initially laid down on 20 January 1887.

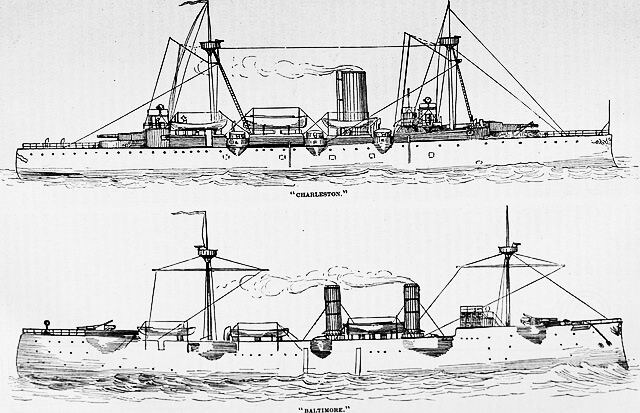

Appelton’s cyclopedia, USS Charleston and Baltimore, the “british cruisers” in US service.

Design of the class

The USS Charleston’s displacement only known figure was 3,730 long tons (3,790 t). Like the Naniwa she was in the 3,700 tonnes range, just three tones heavier as declared, for the same length overall of 320 ft (97.5 m), a similar Beam of 46 ft (14 m) but a lower draught of 18 ft 6 in (5.64 m) versus 20 ft 3 inches or 6.2 meters. The design otherwise was very similar in all aspects, from the protection to the armament, albeit in details. Her whole profile was articulated between her two main guns fore and aft, pretty hefty caliber for that displacement, near-battleship size, and sice secondary rapid fire guns in broadside sponsons. Two short masts topped by spotting platforms and projectors, and a single funnel amidship. The prow was rounded, the hull had an amidship flat section, the straight bow had a limited flare and sheer, but ended with a ram. Unlike ABC cruisers she was not masted and looked more modern in many aspects.

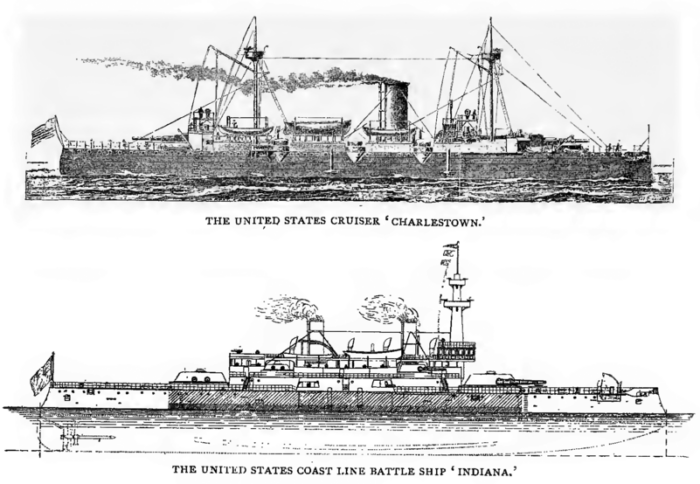

Charleston compared to USS Indiana

Protection

As British protected cruisers of the time, she had a waterline turtleback style deck armour, flat in the center, curved downwards to replace the belt and protecting all the vitals. This complete armoured deck, from prow to stern without tapering, was up to 3 inches (76 mm) on its sloped sides down to 2 inches (51 mm) in the middle, flat section. It was common practice to load coal in the adjacent compartments above the deck to mitigate any impact and flooding. Above deck, protection was limited to 3 inches (76 mm) gun shields for her main guns and secondaries, plus bulwarks, and two inches (51 mm) barbettes behind the guns. There was also a two inches (51 mm) conning tower. This was to protect from close quarter fire but in no way sufficient to deal with other protected cruisers, apart the deck. Her big guns were supposed to keep adversaries at bay.

Powerplant

Her powerplant started woth two propeller shafts and a single rudder. The shafts were driven by two US built horizontal compound engines roughly similar in size and output than those delivered to Armstrong, fed in turn by six coal-fired cylindrical boilers for a total rating of 7,500 ihp (5,600 kW). This procured a top speed of 18.2 knots (33.7 km/h; 20.9 mph) on trials, which was great especially compared to the 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) of Naniwa. But not enough to reach design speed, 19 knots. Failing to achieve this top speed, which seems high given the technology used, was perhaps something the yard should have been contesting. In any case, the engine proved troublesome and prone to excessive vibrations due to the tolerance in components coming from many companies and loose quality control. This ended in lenghty and costly modifications after sea trials.

USS Charleston indeed was in fact the very last US Navy ship with a compound engine design, later ones all swapped for the modern triple expansion engines. As said above, she had no sails as fitted. Her two masts could have rigged stud sails but it was never done. USS Charleston could fill all her compartments up to 328 tons of coal enabling a range of 2,990 nmi (5,540 km; 3,440 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). In wartime and filling all voids, she could be loaded as far as 682 tons in order to reach 7,477 nmi (13,847 km; 8,604 mi) which proved handy during the 1898 war. But this was not as good as the Naniwa class, which proved far better steamers with 9,000 nmi (17,000 km; 10,000 mi) at 13 knots.

Armament

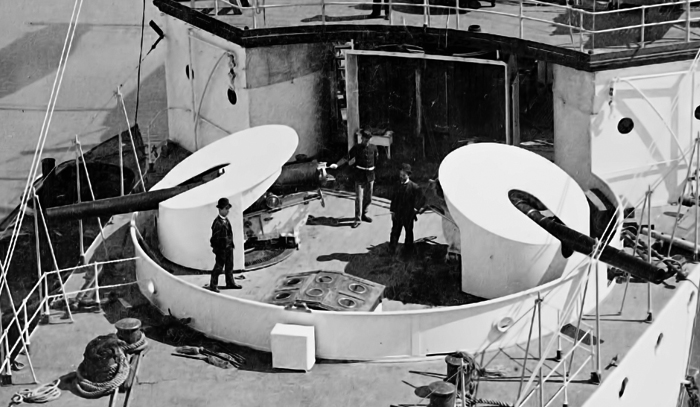

Main guns aft, San Francisco as completed.

The general armament design of both USS Charleston and the Naniwa class were very comparable. However since it was decided to have them equipped only with US ordnance, they were given smaller main guns, 8 inches instead of 10 inches. There was still the same secondary battery, but smaller guns differed in detail, especially for Gatling style machine guns for landing parties.

Main Guns: 2x 8 inches/35 Mark 3

USS Charleston was given two 8-inch (203 mm)/35 caliber Mark 3 guns, one each in bow and stern barbettes. However as they were initially unavailable, on her commissioning in 1889 until her refit in 1891 she had four additional 6-inch guns, mounted in pairs fore and aft.

Secondary Guns: 6x 6-inch (152 mm)/30 caliber Mark 3 guns

The six 6-in/30 Mark 3 were all mounted in in sponsons along the sides. They were not exactly amidships but slightly aft. They were also hidden behind bulwarks, protecting the crews from small arms fire and shrapnel, with openings for the guns being composed of a sponson wall, and a complete shield.

Tertiary guns:

-Four 6-pounder (2.2 in (57 mm)) guns

-Two 3-pounder (1.85 in (47 mm)) Hotchkiss revolving cannons

-Two 1-pounder (1.5 in (37 mm)) Hotchkiss revolving cannons

There were to protect against spar torpedo boats attacks. Location is uncertain, most being placed in the wings fore and aft above the bulwarks, and the two 1-pdr in the spotting tops of the fore and aft masts.

-Landing Party Guns: This was composed of two .45 caliber (11.4 mm) Gatling guns. They could be placed in the two steam cutters onboards. There were seven boats in all under davits for these and a company of 30 Marines that could be reinforced by up to 150 armed sailors from the well supplied small arms locker.

USS Charleston also had on paper four 14-inch (356 mm) torpedo tubes as designed, but they were never mounted, probably a good move as they was no need to remove any later and this freed internal space, eliminated a hull weakness.

⚙ specifications as built |

|

| Displacement | 3,730 long tons (3,790 t) |

| Dimensions | 320 x 45 x 2 ft x 18 ft 6 in (97.5 x 14 x 5.64 m) |

| Propulsion | 2× HC steam engines, 6× cyl. boilers: 7,500 ihp (5,600 kW) |

| Speed | 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) as designed |

| Range | 2,990 nmi (5,540 km; 3,440 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 2× 8-in/35, 6× 6-in/30, 4× 6-pdr, 2× 3-pdr, 2× 1-pdr, 2× .45 cal. Gatling |

| Protection | Gun shields 3 in, Main deck 3 in (75 mm), CT 2 in (51 mm) |

| Crew | 34 officers, 296 men, 30 Marines |

Career of USS Charleston

Published by Detroit Publishing Co

https://www.loc.gov/resource/det.4a14138/

http://www.navsource.org/archives/04/c2/c2.htm

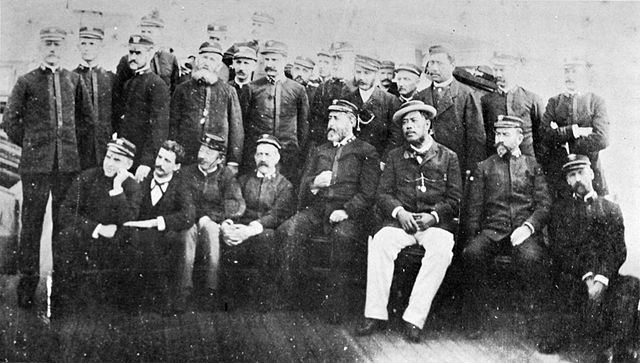

USS Charleston (or Charlestown in britain) was launched on 19 July 1888, Sponsored by Mrs. A. S. Smith and Commissioned on 26 December 1889. She had her trials, fixes and counter-trials in early 1890. She left at alst Mare Island Navy Yard on 10 April 1890 and joined the Pacific Squadron as flagship, and then made a cruise in the eastern Pacific to Hawaii, later carrying the remains of King David Kalakaua to Honolulu as he passe dout in San Francisco. From 8 May until 4 June 1891, she looked for the the Chilean steamer Itata leaving San Diego in violation of the US neutrality laws enforced with the 1891 Chilean Civil War. She was never found. From 19 August until 31 December 1891, USS Charleston cruised in the Far East as flagship, Asiatic Squadron, and met the Squadron in 1892, doing exercises until 7 October. Next she sailed for the east coast, with numerous port calls and arrived in Hampton Roads, on 23 February 1893.

King Kalakaua on board USS Charleston

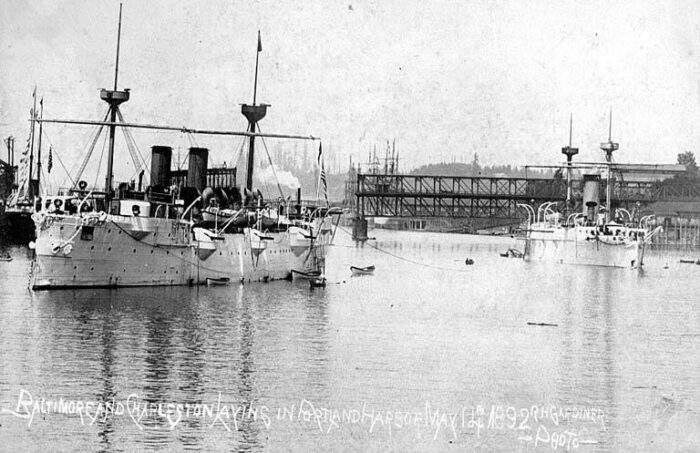

Charleston and Baltimore in Potland

From here, she sailed with US and foreign ships to see the International Naval Review in New York City, 26 April 1893 for the Columbian Exposition. She was presented to President Grover Cleveland on board the despatch vessel USS Dolphin. Late 1893 saw her patrolling the east coast of South America after the Brazilian Revolution. She cruised from Montevideo to San Francisco on 8 July 1894 and preparations to be reassigned to the Asiatic Station. She trained around the west coast and Hawaii until 6 June 1896, and sailed to Yokohama, then sailed back to San Francisco to be decommissioned on 27 July 1896. Reasons are unclear but perhaps her powerplant.

She was reactivated at fever pitch as the Spanish–American War broke out. Fully recommissioned on 5 May 1898 under Captain Henry Glass, she sailed 16 days later to Honolulu, joined by three chartered steamers with troops. She was to sail to and invade Guam, a Spanish possession. At daybreak on 20 June, the convoy arrived at the north of Guam and Charleston entered Agana harbor and then proceeded to hte main port of Apra. Leaving the transports anchored outside she entered the harbor ready to deal with Fort Santa Cruz. When at good distance she fired a challenge.

Charleston en route to Guam

In one of these events typical of the Gentlemanly code of conduct of the time, a Spanish delegation arrived in a rowboat with a large Spanish flag. Spanish authorities came on board, apologizing for not being able to answer the supposed salute, having no gunpowder in store, …and learn about the state of war between the countries. Surrender terms were discussed, after which the delegation returned on land to prepare for a proper surrender and keys transfer ceremony. The US sent a landing party ashore to be greeted by the governor. The garrison of 69 were made symbolically prisoners and were transferred in the transports. Charleston then disembarked troops and sailed to join Admiral George Dewey in Manila Bay.

She arrived on 30 June 1898, having missed the battle, entering an harbor littered with still smoking wrecks. She still joined in the final bombardment of 13 August prompting the surrender. She remained in the Philippines in 1898 and 1899, and started to deal with insurgent positions when called by Army forces advancing inland. She also was part of the expedition to capture Subic Bay in September 1899.

However while she was returning from it to Manila, USS Charleston grounded on Guinápac Rocks, 10 miles East by South of Camiguin Islandn north of Luzon. It happened at 5:30am on 2 November 1899. There was no casulaty and her crew was partly evacuated. Later a party examined her hull and she was declared wrecked beyond salvage, abandoned, stripped down from armament. The crew proceeded to these optrations from the camp on a nearby island and later moved to Camiguin. Launches were budy all this tome. On 12 November the gunboat USS Helena (PG-9) rescued the shipwrecked men and took on board some of the salvage ordnance and equipments. USS Charleston became the first steel-hulled ship lost by the US Navy.

Read More/Src

Books

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905

Friedman, Norman (1984). U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History

Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants.

Rentfrow, James C. Home Squadron: The U.S. Navy on the North Atlantic Station.

Spears, John Randolph. A History of the United States Navy. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1908.

Taylor, Michael J.H. (1990). Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War I. Studio.

The White Squadron. Toledo, Ohio: Woolson Spice Co., 1891.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign