US Navy Submersible (1932-45)

US Navy Submersible (1932-45)WW2 US submarines:

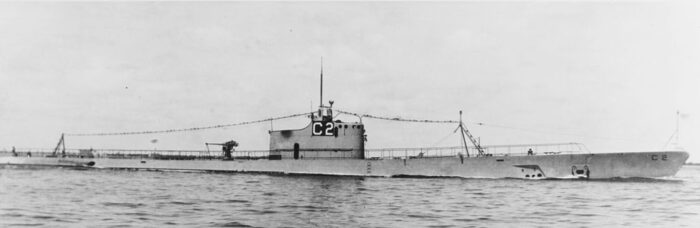

O class | R class | S class | T class | Barracuda class | USS Argonaut | Narwhal class | USS Dolphin | Cachalot class | Porpoise class | Salmon class | Sargo class | Tambor class | Mackerel class | Gato class | Balao class | Tench classThe Cachalot-class were two medium-sized oceanic submarines built for the United States Navy built, last V-Boats, but first under the tonnage limits of the London Naval Treaty of 1930. Laid down as V-8 and V-9, they were loosely related to the others and under an extensive study to determine the optimum submarine size under new treaty restrictions (the Washington treaty had no such limitations on submarines apart global tonnage). It was determine how much armament, speed and endurance, could be obtained of a design that can stay on station far from a base in the Pacific. At 1,100 long tons (1,100 t) surfaced or standard they were much smaller than the previous USS Dolphin, and determined the size of all interwar US submarines to come. Still capable on 1,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) surfaced at 10 knots, they could carry a 3-inches deck gun and 16 torpedoes. Both took part in the Pacific war, but given their limited range compared to the new Gato class they only made three war patrols each, before being relegated to training from September 1942, until discarded in October 1945.

Development

The design of the Cachalots departed from the “V-boats” in more than way. They were not related to the latter as they did not experiment on propulsion or other concepts but just tested previous solutions developed for USS Dolphin, shrunk down to fit treaty restrictions. This of London just signed by the US Government on 22 April 1930. It went further than the Treaty of Washington of 1922 related to the use of Submarines (among others).

Article 22 established rules of international law regarding submarine trade warfare.

Part II, Art VII precised that:

1. No submarine the standard displacement of which exceeds 2,000 tons (2,032 metric tons) (…)

2. Each of the High Contracting Parties may, however, retain, build or acquire a maximum number of three submarines of a standard displacement not exceeding 2,800 tons (2,845 metric tons) (…)

3. The High Contracting Parties may retain the submarines which they possessed on 1 April 1930 having a standard displacement not in excess of 2,000 tons (2,032 metric tons) (…)

It must be precised here that the standard displacement as assimilated to surfaced displacement, ballasts empty.

In Article XVI it was precised that all three main naval powers (US, UK and Japan) could not exceed a global tonnage of 52,700 tons (53,543 metric tons) in submarines.

The problem was a large chunk of this tonnage had been consumed already by the earlier V-boats, including large cruiser types, and WW1 S-Boats as well. This left limited room for manoeuvre, unless scrapping 1918-20 generation boats. On paper indeed, this limited the interwar USN fleet to 50 submarines at best.

Joseph W. Paige from the Navy’s Bureau of Construction and Repair (BuC&R) was tasked by the admiralty right after signing the treaty how to developed a basic design, that can maximize it’s effectiveness in the type of warfare that was theorized (and played at Naval War College) in a Pacific campaign scenario. The builder was already selected to be Electric Boat, for detailed arrangement. Despite it’s origin and fame, the company did not built any new submarines since older design R-boats for Peru. USS Cuttlefish was the first to be built in Groton, Connecticut, and the company’s engineers were tasked to create the detailed design. The company at the time acted mostly as engineering advisor as construction of its previous designs was subcontracted to other shipyards such as Fore River Shipbuilding in Quincy, Massachusetts.

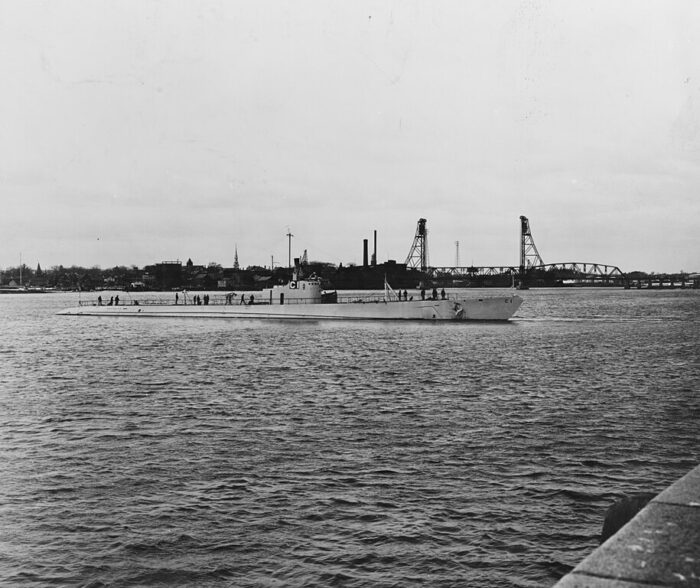

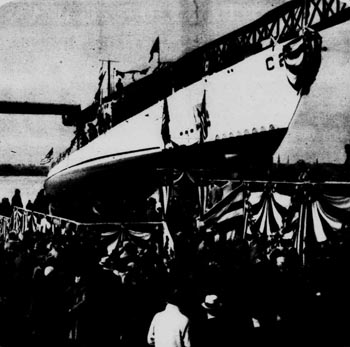

The second boat ordered, USS Cachalot, was ordered to Portsmouth Navy Yard and laid down on 21 October 1931, a week after Cuttlefish. However, this relative lack of recent building experience led Electric Boat to be late in delivery: USS Cuttlefish was indeed delivered on 21 November 1933 versus 19 October 1933 for Portsmouth’s Cachalot. Completion was even more complicated for Electric Boat, which delivered USS Cuttlefish way below schedule in June 1934, versus 1 December 1933 for Portsmouth’s Cachalot. Because of this, she was assigned the pennant S 170 versus her sister’s S 171, making her the class’s lead vessel.

Design of the class

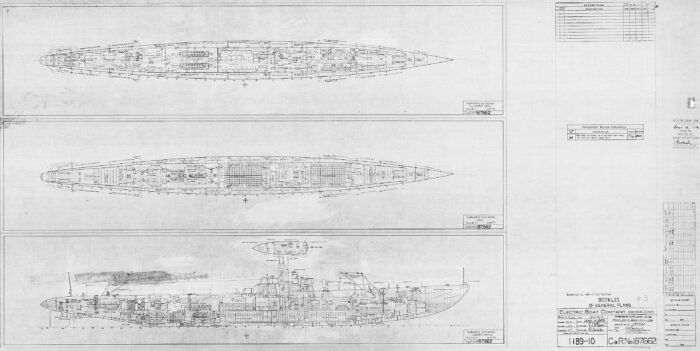

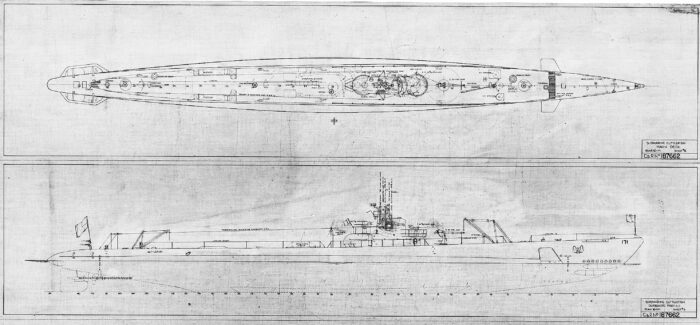

Plans of the boats reconstructed in 1942, National Archives, src catalog.archives.gov. Original profile on navsource by Jim Christley.

Hull and general design

The class still looked externally as “fleet submarines” but internally it featured full double hulls. Thus was the result of the recent Submarine Officers Conference looking to adapt this feature from the war prize Kaiserliche Marine’s U-135. Not only this, but also its direct-drive diesel-electric propulsion systems as well as separate crew’s mess; In this rearrangement by Eelectric Boat of the internal layout, Portsmouth followed these design changes. The same officers obtaibned considerable space around the conning tower and a large bridge fairwater. This was cut down in WW2 overhaul. A 3-inch gun was selected instead the previous 4 inch (102 mm)/50 caliber of USS Dolphin as it was believed that a larger gun gun would encourage submarine captains to fight on the surface, including against superior ASW vessels. The 3-in was seen as only strickly defensive solved also space and weight issues with the restricted design overall. The rounds alone were twice as smaller and lighter. This, incidentally, remained the standard submarine deck gun until the war broke out. It’s early war experience that pushed to adopt a 5-inches gun for the Gato class.

Powerplant

As-built they were to be propelled by a pair of BuEng-built, MAN-designed M9Vu 40/46, 9-cylinder, 2-cycle direct drive main diesel engines. They developed 1,535 hp (1,145 kW) each, for 3,070 hp total. There was an addition BuEng MAN 2-cycle auxiliary diesel enginewhich in turn drove a 330 kW (440 hp) electrical generator to reload the two 120-cell Exide batteries. But it could be coupled onto the main drives via a diesel-electric system powering the main 800 hp (600 kW) each electric motors to boost surface speed if needed to 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph). When submerged, she lost ten knots at 7 knots (13 km/h; 8.1 mph). This was less than USS Dolphin, still capable of 8.7 knots.

The full double hull design however not only had external tanks too narrow for easy maintenance, but the reduced pressure hull hampered so much that maintenance of the MAN diesels that they even led to complete re-engining. In fact, General Motors-Winton 4-cycle 16-258 engines were adopted during their major reconstruction in 1936-38. USS Cuttlefish was however the first submarine ever fitted with air conditioning, quite a progres in crew’s eyes. In complement to its sixteen torpedoes in storage total, this was the first US submarine to make use of the brand new Mark I Torpedo Data Computer (TDC).

As for range, it was clear that new solutions were needed to fit as much oil inside the hull as possible (83,290 US gallons or 315,300 L), and Electric Boat expanded on the use of electric welding pioneered by Portsmouth. This ended with diverging designs, with EB’s USS Cuttlefish having most of her outer hull with welded in fuel tanks whhereas the inner pressure hull remained riveted. At Portsmouth, non-critical areas on USS Cachalot were welded, the rest riveted. The superstructure, piping brackets, support framing, interior tanks were all riveted on the inner and outer hulls but they showed in 1941 that would leak fuel oil instead of all welded boats. The oil on board, was 111 tonnes versus 412 tonnes on US Dolphin. The result was however 6,000 nm at 10 knots for the latter versus 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km; 13,000 mi) at the same speed (19 km/h; 12 mph) for the Cachalot class.

Their underwater endurance was 10 hours at 5 knots (9.3 km/h) submerged. They could aloso dive to 75 meters (246 ft) as limit service depth.

Armament

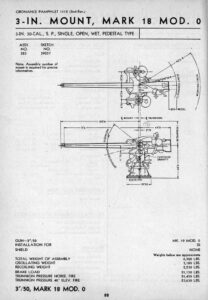

3-inch/50-caliber gun Mk 17/18

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Marks 17 and 18 were installed on the Cachalot class, first used on R-class submarines launched in 1918–1919.

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Marks 17 and 18 were installed on the Cachalot class, first used on R-class submarines launched in 1918–1919.

The Mark 17 guns had a Mark 11 mounting and the Mark 18 guns had the Mark 18 mounting. Importantly enough, the gun was located aft of the conning tower. Image: 3-in/50 Mark 18 specs and sheet, src HNSA via navweaps.

⚙ specifications 3-in/50 Mark 18 |

|

| Weight | 6,500 Ibs |

| Barrel length | 120 inches |

| Elevation/Traverse | -15/+40 degrees |

| Loading system | Manual, vertical sliding wedge type breech |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,700 fps (823 mps) |

| Range | 14,000 yards (12,802 m) at 33° |

| Guidance | Optical |

| Crew | 6 |

| Round | 24 lbs. (10.9 kg) AP, HC, AA, Illum. |

| Rate of Fire | 15 – 20 rounds per minute |

The Cachalot class were different from previous designs, with four tubes in the bow ands two tubes in the stern.

Mark 10

These boats were capable of firing the 21-inches Mark 10 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark 10, a 1917 design entering service in 1918. From 1927 these were the Mod 3, last designed by Bliss and manufactured by the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport. They equipped R and S boats, most V Boats and still soldiered in World War II as a trusted straight course to the infamous Mark 14.

⚙ specifications Mark 10 Mod 3

Weight: 2,215 lbs. (1,005 kg)

Dimensions: 183 in (4.953 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater

Range/speed setting: 3,500 yards (3,200 m) / 36 knots

Warhead: 497 lbs. (225 kg) TNT or 485 lbs. (220 kg) Torpex

Guidance: Mark 13 Mod 1 gyro

Mark 14

In 1941 she carried the Mark 14, entering service in 1930. Designed replacement for the Mark 10, this was the new standard.

⚙ specifications Mark 14 TORPEDO

Weight: Mod 0: 3,000 lbs. (1,361 kg), Mod 3: 3,061 lbs. (1,388 kg)

Dimensions: 20 ft 6 in (6.248 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater steam turbine

Range/speed setting: 4,500 yards (4,100 m)/46 knots, 9,000 yards (8,200 m)/31 knots or 30.5 knots

Warhead Mod 0: 507 lbs. (230 kg) TNT, Mod 3: 668 lbs. (303 kg) TPX

Guidance: Mark 12 Mod 3 gyro

The two boats also had the classic two 0.3 cal. liquid cooled Browning light Machine guns as AA defence in the platform aft of the conning tower. They were presumbaly replaced in 1938 by three cal.50 browning M2 or 12.7mm/90 heavy machine guns and a single or twin 20 mm Oerlikon gun in 1942 as refitted and shown on plans.

Sensors

QC sonar: The QC/JK gear was located in the Conning Tower, companion units with the QC gear as active/passive sonar and JK gear (passive only). Raides and lowered by a hydraulic system, training by electric motor controlled by handle in the operating station.

JK sonar: The JK/QC combination projector is mounted portside. The JK face is just like QB. The QC face contains small nickel tubes, which change size when a sound wave strikes this face. (The NM projector, mounted on the hull centerline in the forward trim tank, is used only for echo sounding.)

Se the full reference here

Modernizations

In 1937-1938 the near-impossible maintannce of their BuEng/MAN diesels meant they were replaced by smaller and yet more powerful Motors-Winton 4-cycle 16-258 engines (3,100hp).

In 1942 they were both upgraded with the SD and SJ radars and their conning tower was massively cut down and redesigned as other boats of the time. The 76/50 was now a Marl 11, and three 0.5 in/90 HMGs fitted in the CT platforms. They had still the QC and JK sonars unchanged as the targeting computer.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 1,120 long tons surface, 1,650 long tons submerged |

| Dimensions | |

| Propulsion | 2 MAN diesels/2 electric motors 2770/1600 hp, 2× 120-cell batt. 2× EDEM |

| Speed | 17 knots surfaced, 7-8 knots* submerged |

| Range | 333t oil, 9,000 nmi at 12 knots normal, 50 underwater at 5 knots |

| Max service depth | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Armament | 6x 21-in TTs (4 fwd, 2 aft, 16 torpedoes), 1×3 in/50 deck gun, see notes |

| Sensors | QC-JK suite, radars in 1942 |

| Crew | 51 officers and ratings |

*8 knots ater 1938 refit.

USS Cachalot (SS-170)

USS Cachalot (SS-170)

After 1933 shakedown, tests, trials, fixes and an overhaul, USS Cachalot sailed for San Diego and on 17 October 1934 joined the Submarine Force there. She took part in many exercises until 1937 along the West Coast, fleet problems and torpedo practice but also tactical/sonar training. She made two sorties to Pearl Harbor and one to the Panama Canal Zone for a massive fleet exercise.

After 1933 shakedown, tests, trials, fixes and an overhaul, USS Cachalot sailed for San Diego and on 17 October 1934 joined the Submarine Force there. She took part in many exercises until 1937 along the West Coast, fleet problems and torpedo practice but also tactical/sonar training. She made two sorties to Pearl Harbor and one to the Panama Canal Zone for a massive fleet exercise.

She left cleared San Diego on 16 June 1937 for New London in Connecticut, used for experimental torpedo firing at the Newport Torpedo Station as well as sonar training at the nearby Submarine School, until 26 October 1937. Next she started her overhaul at the New York Navy Yard until 1938, as said above fitted with new General Motors Winton engines. She took part in the 1938 fleet problem as well as torpedo practice and sound training in the Caribbean/Canal Zone. On 16 June 1939 she was back at Pearl Harbor and started training with the Scouting Force.

She was berthed at Pearl Harbor in yard overhaul by 7 December 1941. She was strafed and one man was wounded, but she escaped serious damage. Yard work was completed very quick to free the space, and on 12 January 1942 she departed for her first war patrol, refueling at Midway Island and making a reconnaissance of Wake Island as well as Eniwetok, Ponape, Truk, Namonuito, and Hall Islands until back on 18 March 1942 with Intel on Japanese bases. Her second patrol was done from Midway on 9 June to the home islands, where she spotted, attacked, and badly damaged an enemy tanker. She was back at Pearl Harbor on 26 July and sailed again for a final patrol on 23 September this time in the Bering Sea for the Aleutian Islands operations.

When back given her age and lack of range it was decided to have her, like her sister, recast as training ship. She was sent to the Submarine School at New London, starting service here from late 1942 until 30 June 1945 before sailing to Philadelphia to be decommissioned on 17 October. She was sold for BU on 26 January 1947 after nearly two years in the mothballs. She won 4 battle stars.

USS Cuttlesfish (SS-171)

USS Cuttlesfish (SS-171)

After commission, trials, fixes, new trials and counter-fixes then an overall and all qualifications in 1934, she left New London on 15 May 1935 for San Diego on 22 June. She started a cycle of torpedo practice, fleet tactics on the West Coast making two trips to Pearl Harbor until 28 June 1937 before beign sent to the Panama Canal via Miami and New York City, reaching New London on 28 July, for experimental torpedo firing and sound training at the Submarine School. Sopon after she entered a drydock overhaul to have her Winton GM engines installed at New York Navy Yard, leaving it on 22 October 1938 for Coco Solo in the Panama canal zone for diving operations and exercises until 20 March 1939, then she sailed for Mare Island Navy Yard.

After her refit she sailed to Pearl Harbor on 16 June 1939 and patrolled from there while participating to this year’s battle problem. She notably sailed to Samoa and by 1940 was back to the West Coast. On 5 October 1941 she ledy Pearl Harbor for an overhaul at Mare Island and the attack took place when she was still there.

She was soon back to Pearl Harbor, and after rpeparations, sailed out for her first war patrol on 29 January 1942. On 13 February she was off Marcus Island to gather intel on Japanese preparations here, and next, the Bonin Islands, then Midway on 24 March. She had a quick refit there and the final one at Pearl Harbor. On 2 May she was back at Midway ahd sailed from there for a second war patrol off Saipain on 18-24 May and the northern Mariana Islands until 19 May, when she spotted and attacked a patrol ship, but was detected after missing and manoeuvering for a second pass. Next she was under severe depth charging for 4 hours but survived. She resupplied air during the night but on 24 May the chase resumed, this time against three IJN destroyers. Again, she survived after a battering. On the 25th while surfaced she was spotted by an enemy plane, whuch attacked, dropped two bombs, but missed as she dived.

USS Cuttlefish then was sent to patrol 700 nautical miles (1,300 km) west of Midway, which made her witnessing the Battle of Midway on 4–6 June. She was back at to Pearl Harbor on 15 June, an prepared to return to Midway as a starting point for her third war patrol, from 29 July, under command of Lieutenant Commander Elliot E. Marshall. When off the Japanese homeland, she spotted and attacked a destroyer on 18 August, but missed. In returned she had to endure a fierce depth charge attack but escaped. On the 21st, she spotted a lone freighter, and launched four torpedoes, three hitting the target and one escort. The sinking could not be confirmed however for nether ship. On 5 September, she spotted and attacked a tanker that was noted as “sank”.

She was back to Pearl Harbor on 20 September 1942, but like her sister given her age and avaialability of better Gato class subs it was founbd more judicious for her to shape up new crews, and she was ordered to New London, at the Submarine School, remaining there from December 1942 to October 1945. On 8 December 1944 she had minor damage when colliding with USS Bray (DE-709). She was decommissioned at Philadelphia on 24 October 1945, sold for BU on 12 February 1947. She won 4 awards including the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two battle stars for World War II service.

Read More/Src

Books

Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis NIP

Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990 Greenwood Press.

Whitman, Edward C. “The Navy’s Variegated V-Class: Out of One, Many?” Undersea Warfare, Fall 2003, Issue 20

Alden, John D., Commander, USN (retired). The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy Annapolis NIP 1979

Johnston, “No More Heads or Tails”, pp. 53–54

Blair, Clay, Jr. Silent Victory. New York: Bantam, 1976

Lenton, H. T. American Submarines (Navies of the Second World War) Doubleday, 1973

Silverstone, Paul H. U.S. Warships of World War II Ian Allan, 1965

Schlesman, Bruce and Roberts, Stephen S., “Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants” Greenwood Press, 1991

Johnston, David, “No More Heads or Tails: The Adoption of Welding in U.S. Navy Submarines” The Submarine Review, June 2020

Campbell, John Naval Weapons of World War Two. Naval Institute Press, 1985

Whitman, Edward C. “The Navy’s Variegated V-Class: Out of One, Many?” Undersea Warfare, Fall 2003, Issue 20

Gardiner, Robert, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946, Conway Maritime Press, 1980.

Links

http://navypedia.org/ships/usa/us_ss_cachalot.htm

http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08171.htm

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_3-50_mk10-22.php

http://www.zerobeat.net/submarine/sub-sonar.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20160221074742/https://pigboats.com/subs/v-boats4.html

https://www.uu.se/download/18.60263fe818f775e78066874/1715780534897/amc_london.pdf

Model Kits

None

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign