Category: ww2 US Navy

Landing Craft, Mechanized

US Navy Landing Craft (1938-45): 500 LCM(1), 8,631 LCM(3), 2,513 LCM(6). Operated 1943-1945 D-Day Special ! The Landing Craft Mechanized…

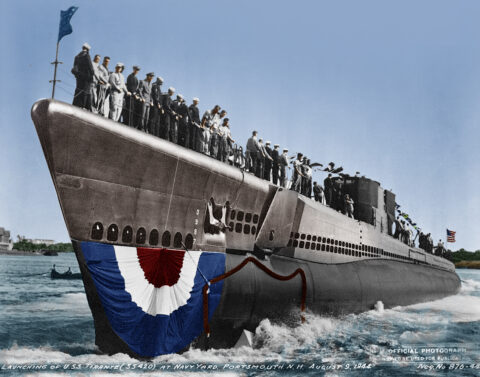

Tench class submarine (1944)

USN Fleet Submarines (1944-51): 80 planned, 51 cancelled, 29 Completed (service until the 1980s), 9 navies The Tench class were…

US Coast Guard

USA (1790-45) -1st Part Introduction The Coast Guard is now a widely accepted concept in most navies, when it exists,…

Balao class submarine (1942)

USN Fleet Submarines (1942-46): 182 planned, 62 cancelled, 120 Completed (service until today), 13 navies The Balao class were a…

Gato Class Submarine

USN Fleet Submarines (1941-43): About 77 subs The Gato class were emergency wartime fleet submarines, built for the USN as…

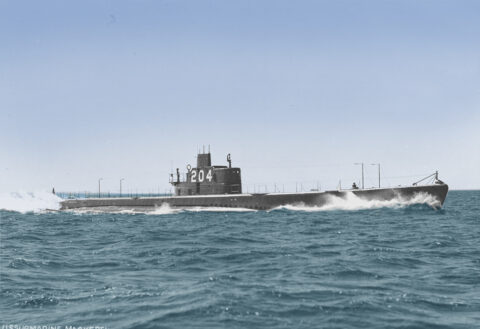

Mackerel class Submarine

US Navy Submersibles, USS Mackerel, Marlin SS-198-211 (1939-48) The Mackerel-class submarines were two prototype submarines laid down before the war…

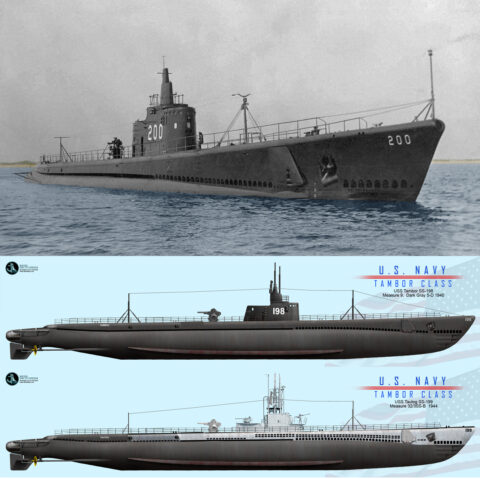

Tambor class Submarine

US Navy Submersibles, USS Tambor, Tautog, Thresher, Triton, Trout, Tuna. Sub-class Gar, Grampus, Grayback, Grayling, Grenadier, Gudgeon SS-198-211 (1939-48) The…

Sargo class submarine (1938)

US Navy Submersibles, USS Sargo, Saury, Spearfish, Sculpin, Squalus, Swordfish, Seadragon, Sealion, Searaven, Seawolf SS-188-197 (1937-48) The Sargo-class were among…

Salmon class submarines (1937)

US Navy Submersibles, USS Salmon, Seal, Skipjack, Snapper, Stingray, Sturgeon SS-182-187 (1936-48) The Salmon-class were six submarines built in three…

Porpoise class submarines (1934)

US Navy Submersibles, 3 sub-classes (1933-45): USS Porpoise, Pike | Shark, Tarpon | Perch, Pickerel, Permit, Plunger, Pollack, Pompano The…

dbodesign

dbodesign