Further east, Indus civilization, represented by seven flourishing and modern cities-states on a river now disappeared (Mohendjo-Daro, Harappa). The Phoenicians of course, the first Mediterranean commercial empire from Tyr, first to ciscumnavigate Africa (Hanno) and travel beyond “Hercules columns”. The Carthaginians (Punic) who founded Carthage (now Tunis) settled permanently in the Western Mediterranean and consolidated their own empire, in rivalty with the Greeks (Macedonians, Thracians and Illyrians included), who imposed their domination against the Persians, and eventually the Romans who made them “Mare Nostrum”, and passed their traditions and strenght to the Byzantines, well into the end of the medieval era.

200 BC, 127 years after Alexander the great passed out.

The Romans also struggled against the last empires of the Diadochi (descendants of the generals of Alexander the Great), the Empire of the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Antigonids of Macedonia and Attalides of Pergamos, Rhodians, Seleucids… The battle of Actium (31 BC) which will mark the end of the Ptolemaic naval power will also illustrate the end of the pre-eminence of the heavy units and the triumph of the pragmatic Roman naval approach to naval warfare.

The fleet of Rome then having no enemy to fight, it was partially disarmed and Rome had to endure for centuries the constant threat of piracy in the Mediterranean. After the fall of Rome with the great invasions (400 BC), Constantinople took over by founding a navy capable of maintaining the naval superiority of the Byzantine empire, recovering and improving the Roman organization. But this story belongs to the Middle Ages…

Papyrus Rafts are the indirect witnesses (they were still manufactured fifty years ago) of the first vessels of the Nile, back in Neolithic times. They indeed existed in forms still advanced in 3000 BC. The Papyrus was, of course, the most common herbaceous found on the delta wetlands: It was available in large quantities, possessed a moderate buoyancy, good flexibility, and could give come in many braided forms. The typical raft had a raised bunch, held at both ends by a rope, The same one found on the first soft wooden boats.

The Cibora – the Papyrus boat – gradually passed in the shape of a basket or a basket, perhaps in 6000-7000 BC (Nile Neolithic peoples), to that, lying in a “shell”. The latter was full, in fact, and came with some accessories to be properly seaworthy, like a maneuver bench, a portico for a paddle used as a drift, and a bipod mast on which was mounted a lattice sail (4000-3500 BC, before the founding of the two Kingdoms).

Thor Eyerdhal experimented with the Ra-I in the 1960s but proved that it was absolutely essential to raise the stern as much as possible to prevent water from impregnating papyrus too much. It is only on this condition that a large ship (made of boots thicker than in the center, constituting the shell) could sail in the Mediterranean, on the great rivers, even in the Indian Ocean, which Ra II inspired Aztec ships demonstrated superbly, as did the Tigris (Mesopotamia). Despite their qualities, Papyrus boats had reduced buoyancy for a certain size, and a length limited to 10 meters at most. It was therefore logical that they should give way at some point to wooden vessels.

EGYPTIAN ANCIENT EMPIRE: The Kheops Ship

A veritable archeological time capsule, this large vessel has been preserved for more than 4500 years (…), thanks to the dryness of the desert and rarefied oxygen in this fully hermetic chamber hold by massive stone slabs, perfectly adjusted. In other words, the container is as fascinating as the content. Until now, the only evidence of these funerary ships, among the best known of the ancient Egyptian ships (pre-Ptolemaic), were finely carved and decorated sculptures found in the Royal tombs.

The Kheops funeral boat was a very light ship, built as expected in planks of fine wood (cedar of Lebanon and not Acacia or Sycamore, too light for her size) linked by planks. The Khufu Funeral Bark is also remarkable for its state of conservation. The funeral bark of Cheops was part of a complex of five boats at the foot of the Pyramid, three stone on the surface east of the pyramid and two genuine, enclosed in sealed basins. Only the boat described was exhumed, discovered in 1954n raised up and recomposed (1224 or 1244 pieces). She measures 43 meters long by 6 wide, and weighs about 45 tons.

Her hull has a covered bridge, and measured up to 1.75 meters. She is on display, in a dedicated room, with a rigorously controlled hygrometry, while wooden had been treated. She is brown, without colors, but she was very probably painted. The dyes, however, too fragile, have not been found and count not be rendered again.

The funeral boat is the solar boat, a very important myth in Egypt of the ancient dynasties because they are linked to the course of the boat of Osiris in the sky (The race of the Sun). It also symbolizes the passage of the deceased into the world beyond, the boat being reserved only to Pharaoh, the equal of the Gods…

On the technical side again, this boat has nautical qualities surprising enough for a boat intended for the Nile. Obviously, she had highly studied shapes and a more solid construction than usual (like the characteristic master-rope joining the bow and the stern and rigidifying the entire hull – some describes it as an “aerial keel” since her duty was similar).

This Demonstrate to the envy that the Egyptians were also Great navigators, although testimonies left us to suppose the contrary. It seems that the builders of this boat have benefited from enlightened advice from seafaring peoples or in contact with maritime civilizations. In this case, there arises the problem of functionality, for the funeral boat was not destined to leave the Nile.

What is certain is that the embalmed body of Cheops was on board when the bark ended its crossing in front of the immense ramp on which the procession would advance, facing the impressive white pyramid. A display Worthy of the Gods …

Other boats of very high quality, still older (5000 years) were found, like the Abydos boats (Upper Egypt). These 14 ships discovered in 1999-2000 were lined up in the desert. According to preliminary studies, these were 20-by-3 meters cedar boats, manned by 30 rowers. Their construction also seemed very solid and suitable for offshore navigation.

ANCIENT EMPIRE COMMERCE BOATS

This type of Egyptian merchant ship is one of the oldest known (2500 to 3000 BC). It is recognizable on numerous bas-reliefs, with very specific characteristics, such as its foldable twin-boom mast, its sail made of linen or papyrus, its shell stitched in cedar of Lebanon, or else in local Sycamore or Acacia which Did not allow planks more than two meters long. These ships also had a quarter-deck with six “rudders”, in fact differently handled paddles, the ancestor of the ancient oars, which predominated until the middle of the Middle Ages with the arrival of the Chinese axial rudder.

KEFTION

The Keftion and Képen were two types of Egyptian military boats of the new empire. They retained the characteristics of other typical Egyptian ships, such as the hulled-lined hull made of cedar leaf tied and waterproofed, making it a so-called “soft” keelless ship, held by a solid rope stretched between the stern And the bow. The sail was made of braided papyrus. This vessel had a relatively low length/width ratio of 6 or 7 to one, and had two fellows for the archers. With the advent of Tuthmosis III, these ships saw their construction reinforced by transverse bars, but still no couples. In 1480 BC, J.C., Queen Hatshepsut sent five Keftions loaded with goods on the Somali coast (the country of Punt at the time), crossing the canal linking the Nile to the Red Sea, built almost 2000 years BC. J.C.

KEPEN

As much as the Keftion was a rather commercial vessel, the Képen was the archetype of the pre-Hellenistic Egyptian warship. Built more for speed and lacking carrying capacity, it was nevertheless constructed in the same way as trade ships, with cedar wood or other related species, a stitched hull with transverse reinforcement beams, and rope running from the prow to the stern for extra rigidity. There was indeed no keel to speak of, invented later by the Phoenicians. The Képen specifics also were bulwarks protecting rowers and soldiers, a long footbridge and a mast top for a watchman/archer. The spur was a weapon of the Kepen, although boarding the enemy ship after watering its bridge with arrows of arrows was the common tactic.

The length of a Kepen could hardly exceed 30 meters. They are known to us by an inscription leaving no doubt and describing well the “Képen” like a warship, a bas-relief found at Medinet Abou describing the conquests of Ramses III in 1170 BC. As early as 1300 BC, indeed, piracy developed at the same time as the flourishing trade relations that Egypt maintained with the Mycenaean and Cretans, Egypt being the interface between India (from 1800 BC thanks to a connecting canal between the Nile and the Red Sea) and the Mediterranean. The Egyptians fought naval battles against famous seafarers, Philistines, Danaens and Achaeans, including the most infamous “Sea Peoples” that brings a new dark age to the area, wiping out several brilliant civilizations.

PHOENICIAN GAULOS

The Phoenician freighter par excellence, the Gaoul (or Gaulos) was the perfect compromise between the Greek and Egyptian influences.

The emblematic Phoenician ship was symmetrical with clean and well-defined characteristics. When the Phoenicians founded Tyre, (Biblos, much earlier, dated back to 7000 BC), they soon had contact with Crete and the brilliant Minoan civilization that resided there. The latter built ships without holding ropes between the prow and the stern, but a keel instead, denoting a much more rigid construction than the standard vessels of the time, those of the Egyptians.

The latter flexible ships, were dependent on small timber and planks sewn. The Minoans seem to be the first to have replaced the string reinforcements with a rigid structure by itself, with a wooden keel on which intermediate pieces (cribs) were laid and on which large arched planks were attached. This shipbuilding revolution, the Phoenicians welcomed it with eagerness, being for a long time under control of the Egyptians.

The Gaoul, in some respects, still had an Egyptian appearance, with a round hull, raised stern and bow, woven sail held between two masts. But it had holding rope, and for good reason: Planking and structure were made of Syria Cedar, the most massive and rigid wood in the area, which had no equivalent in the Levant.

When the Phoenicians emerged from the Egyptian orbit, during the Middle Bronze Age and its contacts with the city-state of Ugarit, it allowed it to gain a technology that boosted commercial extension, from current Lebanon to the columns of Hercules and beyond (trade with the Celts of south-east England, Cornwall), perhaps even a trading post in the Azores and on the American coast.

Innumerable counters were only intended to allow any vessel coasting the day along the coasts to find a haven for the night. Only one true colony was founded, Carthage, which established a new milestone between the Asiatic part and the western part of the Mediterranean, in a crossroads of sea lanes making it impossible to circumvent.

Around 1100 BC, the relative freedom enjoyed by the Phoenicians was due to the decline of the great antagonistic empires of the region, Hittites and Egyptians. The Assyrians did not threaten them, and in general the Phoenicians formed a sphere of co-prosperity with the “peoples of the sea”. The Gaulos played a prominent role in this exchange:

It was sized enough to carry a large load of amphorae (including its deck in galleries to store amphoras vertically, covered by a canvas tent), And at the same time with a modest draft and a relatively flat bottom in the manner of the Egyptian ships allowing it to anchor almost everywhere and even to ascend the rivers. Finally, the Gaulos was characterized by a figure of prow often in the form of head of horse, and a figure of stern in fish tail.

The very name “Phoenician” was a Greek invention to designate peoples of similar culture; in reality they themselves were defined as Sidonites, Byblonians (Giblites), or Tyrians. It drew its origin from the phoenix, a divine bird of the Levant symbolizing the sun rising to the east. But about 800 BC. JC., An early decline began with the gradual seizure of the Assyrians over Tire and Sidon.

The Phoenicians being a peaceful people, they subdued and gradually lost their freedom of commercial action. The Persians in 540 BC. JC. Were therefore seen as liberators. The latter, faithful to their confederal policy, left much greater autonomy to the three great cities, but gradually, Carthage began to gain importance and to detach itself from its Phoenician origin to become fully independent.

Around the Gaulos: Arwad (Syria), Tarsus (Asia Minor), Kition, Paphos (Cyprus), Knossos (Crete), Malta, Hadrumet (South Coast of Carthage, Numidia), Cirta (Inland Numidia), Rachgoun (Current Morocco), Lixus (Atlantic Coast, Morocco), Mogador (Mauritania), Cádiz Seeing Marseilles, it is a colony of Asia Minor …), Tharros and Nora in Sardinia, Motye in Sicily (near Mytilene).

ASSYRIAN BIREME

The Phoenician war galleys left no wreck, for just as the immense majority of the ancient galleys their coefficient of buoyancy remained positive. On the other hand, bas-reliefs inform us to a certain extent, since the engravers were not sailors, and these lithographic testimonies must be taken with a certain distance, and a naval carpenter’s eye, leaving a part Reinterpretation. A model of terracotta is preserved in the museum of Haifa and shows one of these galleys, having a square sail, and quite narrow. A conformation adapted to the speed to the detriment of the place on board for the fighters, was solved by the innovation, taken again by the Greeks, of the gallery over the bridge.

The palace of Nineveh recounting the battle that took place beforehand (700 BC) confronting the forces of Sennacherib, the Son of the great King of Babylon Sargon II, and his biremes used as transports of armed troops on the Nâr Marratoum separating The Tigris and the Euphrates.

It was a “pentecontore” in the sense that it had 26 oars per side, more than 50 rowers. From the top of their gallery, the Assyrian archers, protected by their shields hanging from the bulwarks, had a good shooting platform. These ships were unusual for Assyrians, users of river boats. The Phoenicians used them since 1500 BC. J.C. They are the inventors, but seem to have been inspired by the Cretans for the spur.

MONERE: ARGO

Emblematic type of the monument of the ancient ages of the Mediterranean basin (from the fourteenth century, 10th century before our era), The Argo of the legend of Jason and the Golden Fleece. This representation of a largely ficticious vessel was made, perhaps for the need of a movie, but without historical accuracy in mind.

This is the more accurate “Argo” reconstructed as a Pentekonter and is now displayed in the port of Volos. Src and also official website.

The first galleys with a level of oars (monoreme for the Romans), the oldest, were generally undecked boats but with a small foredeck and aft, possibly a small hold. It was built “first hull”, a technique more elaborate than that of the first ships Egyptian and appeared around the thirteenth century BCE. It consisted of placing on a basic structure with keel and pairs, a plating made of wooden plates (the vats), assembled and held in place by mortises sunk into vertical notches and secured by tenons driven into the mallet.

To waterproof the whole, caulking was used, consisting of applying on the hull of fine linen cloth, coated with heated pitch, then bitumen. Later, towards the tenth century BC. J.C., small copper plates will be used to complete this waterproofing, in particular, due to the relatively rapid decomposition of the bitumen in the sea water.

The Argo of the legend was probably, according to the descriptions given by Ovide, a monoreme of 18 rowers: 9 rowers per side, with a helmsman, and an “officer.” The rowers participated in all the maneuvers of the board, including the brewing of the sail. The oars rest on tops (wooden rings fixed in the flanks of the bulwarks).

It also appears that this ship possessed a small spur, more a traditional feature than a weapon of war. The rosters used in an offensive role only took shape with more massive ships, Dières, Trières and Pentecontores. The reconstructed Argo is an example of what a “warship” could be, with a length of 15 meters, a width of 3.20, which gave it a ratio of 1/5, and made it a relatively Wide and versatile, halfway between a freighter and a real military unit.

The monitors derived from it, the Cisocontore, had hardly more than two rowers per side (20 in all), the Triconteros 30. the latter were clearly longer and had a ratio of 1/6, more favorable to the speed. These apparently appeared during the thirteenth century BCE.

TRICONTER

![]()

A Greek triconter at the time of the Trojan War (1450 BC). This one has 32 rowers, two better than the standard ones. Some late twenties had twenty rowers per side, or 40 in all: The pentaconter was only a logical evolution.

Dikonteros, Cisokonteros, Trikonteros. These terms are known from later writings, from the 5th to the 6th centuries before our era for the most part. They apply to galleys of moner type (a single row of oars, a rowing oar), specific to the Greek navy but not only: Assyrians and Phoenicians also used such types of units, and before them Mycenaean and Minoan.

Although belonging to the majority of the warships of the time, the Phoenicians preferred the Dières, faster. These light galleys date back to the very beginning of the hard construction, with keels and pairs in oak, lined with pine assembled with clinkers (the juxtaposition of planks held by tenons and mortises).

However, these small units formed most of the fleets in the VIIIth century before our era, before precisely the appearance of the Pentacontères and especially the Greek Dières. They never disappeared but were gradually assigned to second-rate roles, due to their agility.

One might even say that they were “second class” units, assigned to liaison and training tasks, or for the transport of rapid troops. But their military value in combat, and this as early as Salamis in 491 BC. J.C., was more reduced in front of heavy units capable of using more effectively their rostrum in effect of mass or of embarking more men of troop.

The fleet which landed on the beach of Troy included both standard cargo vessels, Pentaconteros, cisoconteros (20 rowers), and tricontères (30), intermediates falling between two types with the name of the base class: Avant Pentecontère, the most efficient line ship was to be the 40-oared tricontère, twenty per side. It could have been called tettacontère, but this term was rarely seen in the writings of the chronicles of the time.

A Diconteros or Cisoconteros, systematically employed ten rowers per side. A Triconteros, fifteen. It was their employment that later justified the appearance of the Dieres, consisting in doubling the number of rowers by two rows of oars on the same side, increasing power and speed without excess weight, and the Pentacontère, ultimate attempt To combine the classical scheme of the monoreme with an increase in the number of rowers. The latter proved to be finer and therefore faster theoretically, but being as long and heavy as the Dier, it lacked power.

In any case, the dikonteros generally measured 20 to 23 meters, the tricontères 23 to 26. They had a width of 3.20 to 4.20 meters, and weighed between 15 and 35 tons. They could have a small hold, often lodged under the forecastle, used as a platform for combat by the hoplites.

Their veil being very simple to handle, it is quite possible that there were only two sailors loaded with it, unless it was the rowers themselves. As a result, the complete crew, including soldiers, of a dicontère had to be 28 men, and 40 for the Triconter. It is probable that the first diconter were even more modest and light, for they were stranded on the sand, taking advantage of the tides, before the hard-packed holds appeared.

PENTAKONTER

A Pentaconter of Sparta, Peloponnesian War (5th century BC).

The Pentecontore, or Pentacontère, must not be confused with the “pentere”, not a usual contraction, but the Greek designation of the Roman quinqueremes. This galley was a logical evolution of the Triacontores (30 rowers) and the Cisocontores (20 rowers) of the family of monorems (one rower per bench and rowing).

The Pentekontoros is larger and therefore more conducive to the embarkation of troops (archers, hoplites), faster and stable because it is as wide but better equipped as human power, more massive and therefore more efficient at ramming. Became the standard military ship of the Athenian fleet at war with Rhodes, Macedonia, pirates, and especially the hereditary enemy, the Persian Empire.

Before the Dies emerged, these penteconteros formed the majority of the units of the ancient fleets from the 4th century BC The Persians made extensive use of these ships at Salamis, as these were their only main units, and were beaten By the Greeks who put Dières et Trières in line. The Pentecontents formed the bulk of the light units of the Macedonian, Carthaginian, Roman, and Ptolemaic fleets, disappearing in 200 AD, replaced by the Liburnes and their two or three oarsmen rowing, called “scaloccio swimming.”

Length of 27 to 30 meters on average, ranging from 3.50 to 3.80 meters, moving about 40 or 50 tons, the Pentecontore had a flared section hull. She had a crew reduced to an officer, a helmsman, a “quartermaster” (giving the rhythm of swimming, the Greek rowers being volunteers paying a “right of Passage “and not slaves, some of which could participate in the fighting in case of collision.), Ten hoplites, able to move on a thin central platform, the” gateway “faithful to the original semantics, Shapes to the foredeck and back. In case of ramming, the tripoint bronze rostrum benefited from the mass effect of the galley launched at 5-6 knots (10 Km/h).

DIERE

A Dier from the 6th century BC. J.C. Note the “dolphin” serving as a rostrum, of doubtful effectiveness, the skins stretched to protect the forecastle from the front projectiles, and the ladder placed at the rear.

The Dier was a revolution in the naval domain. Though originally introduced by the Phoenicians and Assyrians in the eighth century BC, which were undeniably paternal, the galleys of war were systematically moners (or monoremes – a single row of oars). The fleets counted on cisocontères and tricontères, two centuries before the invention of the Pentecontère.

Overall, the Greek Dier appeared only a century later. It was probably introduced by a Corinthian shipbuilder, hired by Ameinocles, who observed the effectiveness of the Phoenician models. It is based on two rows of 12 rowers per side, representing a total of 48 rowers, a little less than a penteconteros.

The Dieris also had a meager crew composed of the Dierarch (captain), four deck officers, a helmsman, a “drummer” to keep the swim rate, and four sailors maneuvering, among other things, the Sails. In addition, there were four or six hoplites and two archers, depending on tactical choices. The effectiveness of the Dier to the ramming was already more convincing than for the Assyrian and Phoenician models smaller and light.

The Greek Dier indeed is relatively massive, deep and wide. With a generous hold (probably largely filled with salted meat amphorae and stretched skin bags filled with fresh water), an average length of 31 meters, a width of 4.20 meters, a draft at full load Of a meter ten, and a displacement of 75 tons, the Diere was of comparable weight, and slightly superior to the pentakonteros.

However, the advantage of a staged swimming allowed, unlike the great moners like the pentakonteres, to gain space. The length of the first Dies being thus slightly less, their maneuverability was reinforced accordingly. Thereafter, their tonnage and dimensions increased with the increased number of rowers.

It is also often forgotten to say the fundamental difference between the Greek Dier and the Roman biremes developed later: Their rowers were free men, citizens paying a right of passage or not, and also, as many potential fighters in case of confrontation.

Being rowing on an Athenian galley could also be a very respectable military post, these rowers being specifically trained for combat, within case of collision the physical limit of exhaustive exhaustion following swift maneuvers in combat. The reconstructions of Dières were rare, one can quote recently that carried out by the Ukrainians with their Ivlia.

In Combat: The Dieres engaged at Salamis (480 BC) possessing possibly formidable weapons such as the dolphin, widely used by the Romans thereafter, a collision weapon, held by a yard itself secured to the mast, And dropped on the deck of the opposing ship. It was a weight (lead) that had been given the shape of a large point, in order to easily cross the two to three levels of wood (the bridge, the bridge and the hold in the case of the Dieries).

The aim was to provoke an important waterway, the galley of this period being, practically, unsinkable. Also, fire could also be a weapon of choice. At the side of the Hoplites, elite fighters well armed with handguns and throwers, there were sometimes “light” fighters, the epibatai, who could shortly before the collision, launch on the opponent, in addition Lances, “pots”, small round amphorae filled with pitch, and inflamed with a tissue, an ancestor of the incendiary bombs of which they protected themselves by bulwarks stretched of skin and soaked with oil.

The ballista and catapults entered shortly afterwards, enabling the distance of the combat to be increased to a hundred meters.

Let us recall, finally, that the rowers of these galleys were volunteers who paid their way by rowing, or were enrolled, and touching the pay. They had a cushion coated with grease, which allowed them to slide on their smooth benches, their feet well wedged in the previous bench, flexing their legs.

This technique allowed them to provide the minimum effort for the best efficiency. In addition, the rowers owned their cushion and paddle and were able to embark in any galley. When the Spartans attacked the Athenians in 476 BC, They crossed a tongue of land on foot, carrying their oars and cushions. The complex swimming technique required a training of 8 months per year for a full-time rower…

ATHENIAN TRIERE

The Triere is the most famous and celebrated classical “heavy” unit of the Antique fleets. Greek Invention, taking advantage of by Admiral Themistocles at the battle of Salamis, where he defeated the Persian fleet of Xerxes in 480 BC. J., the triere was obtained by adding a rower and a bench to the Dieris, to reach 170 rowers.

Scarcely larger and longer than the Diere, but a little heavier (about 80 to 85 tons), the Trieris was considerably faster and devastating than dieris and older Pentekonters. The trieris was famous also by the enigma to the historians who wondered how to manage the swimming with such a disposition of the rowers.

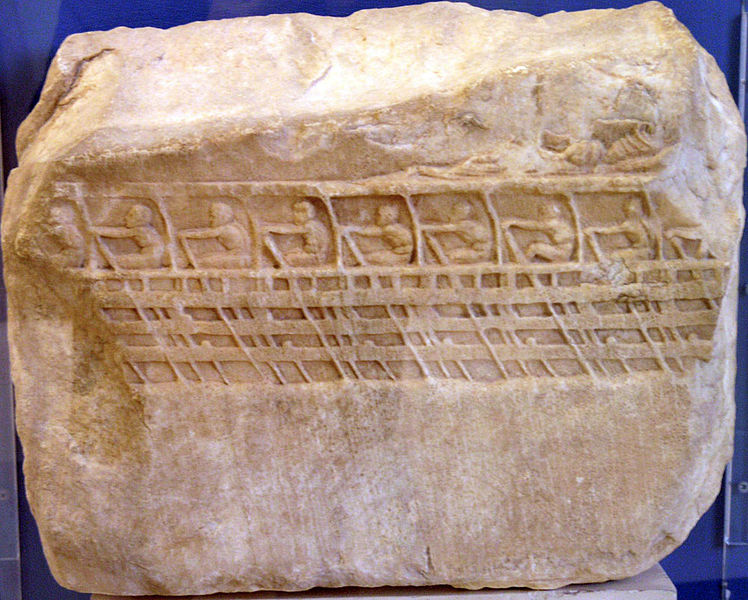

Napoleon III reconstructed and tested one on the seine, which only reinforced the mystery, while through more recent reconstructions, modern archeology gives its answer, supported by frescoes, paintings, mosaics, bas-reliefs, sculptures as iconographic evidence and texts.

The triere demonstrated that it was quite manageable by playing along the length of the oars and physical condition of the rowers, and relatively effective for the time. Replenishments: Napoleon III was passionate like most of his contemporaries (Romantic period, mid-XIXth Century) by ancient civilizations. He helped to clarify the trieris mystery on his personal funds.

His disappointing essays only deepened the enigma. John Morrison and John Coates, in 1988 reconstituted the “Olympias”, a Greek trireme of 500 BC, and solved the problem. The lessons learned from this empirical experience with Thor Eyerdhal deserve a complete dossier. Here is the unpublished report of this experiment signed John Morrison and published in issue 183 (June 1993) of the files of the archeology:

“At an international conference deliberately called” Advisory discussion “held in April 1983 at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, Dr. Coates and I proposed the proposed reconstruction of a triple Athenian V And the sixth century BC Following this conference, the “Trireme Trust” was created in Britain, which was later invited by the Hellenic navy to collaborate with it in order to construct a trireme grandeur nature according to the concepts we Developed.

This ship, launched in June 1987 in Piraeus and named “Olympias”, was put into service after the technical tests to which it was submitted in August of the same year by the Navy and the trust acting in concert. Trials followed in 1988, 1990 and 1992. 1993 marks the tenth anniversary of the start of the project.

It is planned to sail the Olympias in June on the Thames to participate in the Anglo-Greek celebration of the 2500th anniversary of the birth of democracy in Athens. The ship will draw the attention of scholars and the public of Western Europe. It is, therefore, appropriate to review the aims of its construction, to examine what it has accomplished, to evaluate what it represents today and to draw lessons from the teaching it has given us (More to follow).

RECONSTRUCTION: THE OLYMPIAS

What is Olympias:

The trireme trust was founded to promote the construction of an Athenian triere copy. The Greek Trust and the Greek Navy can today congratulate themselves on achieving their goal by achieving Olympias. Their success is however disputed by some who point out that this ship is not rebuilt according to real vestiges of antique triere found to be discovered on seabed.

The objection is less admissible than it appears at first sight. First of all the Trières did not flow: When a waterway was declared there, they floated filled with water, and being unable to sail, they were towed. Even drowned, they had, like Olympias, a positive buoyancy coefficient. Constructed of wood, with only a small proportion of materials heavier than water, the average density of the building and its contents was, therefore, lower than that of water.

In the hypothesis that a trire was able, despite everything, to flow, how could an archaeologist identify it on the substance? Only the lower elements of the hull could have survived. But even in the presence of numerous vestiges, the archaeologist can not decide whether they are those of a trireme, but from what he knows of descriptions made in literature and inscriptions; The latter are the only means of identifying a vessel that appears on ancient representations.

There is only one exception to this: the grafitto of Alba Fucens on which one reads navis tetreri longa (quadrirème or “4”). The wrecks obviously do not have “etiquette”; Therefore the definite identification of a triere is impossible. In case one of them has sunk, the archaeologist will identify it only if he knows beforehand what he is looking for. Therefore, in the absence of a properly identified triere, Dr. Coates and I thought it would be reasonable to proceed as follows:

Gather all the trier data that we could find in the language, literature and inscriptions Various; Use these data to carry out probable identifications of triere representations; Introduce the imperatives of geometry and physics to draw a vessel that incorporates the data of the first and second points; And, as far as possible, construct a vessel according to this drawing, check its characteristics and performances, and compare them with the writings of ancient authors. This method would allow at least to recognize a trireme or its representation newly discovered but not accompanied by an inscription.

Legitimacy of reconstruction: Archaeologists have asked themselves whether experimental archeology, that is to say the reconstruction of objects which can only be a copy of their ancient model, was really or not of archeology in the “Strict acceptance of the term”.

The questioning of the merits of the construction and nature of the Olympias gives us the opportunity to present here the main arguments in its favor. Evidence, or evidence, of the reality of an ancient artefact can be direct and/or indirect.

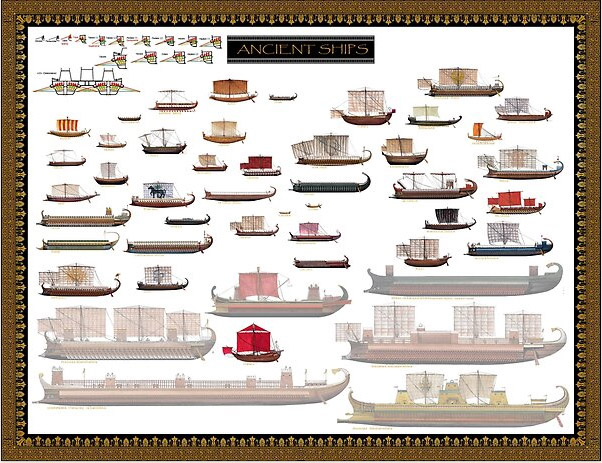

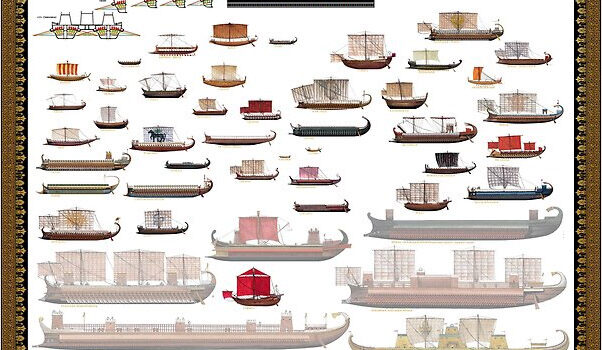

Support Naval Encyclopedia ! – Antique ship poster – the complete typology

Among the first, there is the existence of real vestiges of the object or of those directly related, its representations accompanied by an inscription and the contemporary literary attestations which one has a direct relationship with it. Indirect evidence includes figures that can be recognized as images of the artifact and, in the specific case of triremes, contemporary shipbuilding practices.

In the absence of certain wrecks, the ancient traces that directly concern the trire are on the one hand the holds of Zea (article of D. Blackman), in the port of Piraeus, built to shelter the triere, and other Vocabulary and quotations in literature and inscriptions.

The holds of Zéa were built in the 5th century in the limestone rock to shelter triremes and were restored in the 4th century BC They each have a maximum width slightly less than 6 meters, well enough for a trire. Their length at the present level of the sea is 37 meters but I.X. Dragatzes specifies that they extend farther underwater whose level has risen since the 4th century BC The holds have been able to reach a depth of about 0.8 to 0.9 meters below the surface of the water, With a slope perhaps more pronounced to allow the drying of the boats.

In ancient Greek, the term “sorts” means “(ship) three times equipped …”, or more likely “three times rowed”. Whatever it is, it means that the ship has three units that other boats have in different numbers. The index to say it is provided by the triskalmos synonym, used by Aeschylus as an alternative to say trire.

This ship has three Skalmoi (oars) while others have a different number. There is ample evidence that the oldest Greek galleys, with a single level of 10, 15 or 25 oars per ship, were later armed at two levels of oars to undoubtedly improve the power/weight ratio and To make the ship more maneuverable when we began to use spurs for the collision of the enemy.

This modification means that in the “space” of the rower of the old galleys, two pivots of rowing had to be placed where there was only one before; One was necessarily at a different level from the other. At the time, however, it seems that the necessity of designating the ship was not felt by the new word dieres, which appeared only much later, in the second century AD. J.C., perhaps translated from the Latin Biremis. The words triskalmos and trieres may then apply to a ship in which the number of oars and rowers in space has been increased to three.

This time what distinguished a boat with fifty oars from a boat with 170 oars justified the use of a new name: triskalmos or more prosaically sort. This reasoning leads to the very important conclusion that at least at the time when Aeschylus wrote “the Persians” in 473 BC. J.C., the space of the rower was recognized as one of the fundamental elements of a galley.

The number of rowers in the longest row of a galley is 31, the number known from the inscriptions. With a cubit “Doric”, of 490 mm, the space of two cubits, or 980 mm determines the length of the ship in its part equipped with oars; It would be about 30 meters. Consequently, the total length of the vessel may be estimated to be somewhat less than forty meters, which would allow it to hold in the holds of Zea, if the sea level has risen well since the time of the Athenian triremes.

Bas-relief clearly showing the three ranks of rowers. On later Roman galleys, flanks were completely enclosed, to protect the rowers and mask their view of a possible incoming ramming prow… It would have been blazing hot inside, but in time, these rowers became prisoners and slaves.

The names for the three categories of oars and rowers, the Thranites, Zygios and Thalamios, also inform us. All three are found in naval inventories to designate oars, but the first and last words are also used by historians to designate rowers. The word to designate the hold appears to be Thalamos or thalamus.

The penteconter (in Greek pentekonteros: ship with fifty rowers), with its single row of oars on board could transport a certain volume of payload. In the odyssey, we read that gifts are stowed under the Zyga (swimming bench) and Herodotus describes the Phocaeans who prefer exile to Persian domination and take the sea with their families and their goods on their pentekonter.

When the second level of oars was introduced, the hold was sacrificed to gain more power. It is reasonable to suppose that these oars and their rowers of the second level were called thalamioi, and that those of the upper level, where the rowers used to sit on the shoals, were called Zigioi. The words Zigie and Thalamite are erroneous Byzantine inventions, which, it is supposed, were a counterpart to Thranites.

Since the middle of the 6th century BC the poet Hipponax was the first to mention a trire equipped with a spur and many benches, this one appears frequently in the literature. Herodotus (3.13.1.2) speaks of a ship with a crew of 200 persons, which could only be a trire, since it is the number cited later for this type of ship, and because no other type of ship This size is not reported at the time. However the information given relates to its performance of speed and agility rather than the details of its construction.

The most important text of the 5th century BC. J.C. is probably the narrative of Thucydides (2.93.2) speaking of Corinthian rowers transferred to megarian trenches on the other side of the isthmus, “each carrying its rowing, cushion and tower.” This text thus makes it possible to invalidate that the rowers of trierers may have teamed two or more by rowing, as was often hinted at.

According to Thucydides (7.67) it would seem that on a trire, the men on deck (Katastroma) had to sit. At the beginning of the 5th century BC. It would seem that the bridge was not built transversely from one side of the ship to the other, but that it was later built in order to carry more soldiers. Shielding screens or grids, if necessary, became normal on-board equipment.

Another important text relating to the system of oars of the triremes is found in Aristotle (part of animals 687-18): speaking of the fingers of the hand, he says that “there are good reasons for the external finger to be short, That the middle one is long, like the middle oar on a boat. ” The author of “Mechanika” (4th century BC, attributed to Aristotle) gives the reason for the difference in length of the oars of a galley.

To the question of why the rowers of the middle make the most advanced the building, he replies that it depends on the power developed by the ream like lever: The part of the longest train (that is to say of the tower up to the handle) is inside the hull in the middle of the building, where it is the widest.

At the prow and the stern, the convergence of the edges (port and starboard) obliges to shorten this part of the train. The Greek physician Galien states the same point: “All the oars are thrown out of the hull at the same distance from the flanks of the boat, although they are not of the same total length.” This is useful information, as will be seen later.

Entries and Indirect Sources:

But the most abundant sources on the triremes of the Athenian navy in general are the inscriptions of the fourth century: “The decree of Themistocles” (IG2 1604-1632) and what we will call the “naval inventories”, towards the third quarter of 4th century (377-376 to 323-322 BC). These “inventories” were discovered in Piraeus and give, in a fragmentary state, the annual reports of the outgoing council of shipyard supervisors.

The “decree of Themistocles” is an inscription, which, it is thought, resumes in the literary form of the fourth century, the decree presented by Themistocles to the Athenian assembly in the autumn of the year 481 BC. A “trierarch” (captain), ten hoplites and four archers on each triere. This is corroborated for the fifth century by literary sources (Thucydides 3.94.8 and 6.43).

The modest number of defenders denotes a tactical use of the ship, which influences the construction of the bridge of the triremes of the fifth century. The “naval inventories” contain on the triremes information of great value for the history.

They describe the organization and practices of the Athenian navy during the third quarter of the fourth century and allow us to follow the gradual introduction of tetreres and penteres. (“4” and “5”). On triremes, information is limited but valuable. Their most interesting contribution relates to positions related to oars.

They designate three categories: thranite, zygian and thalamian. The quantities for each building are invariably 62 thranites, 54 zygians and 54 thalamians (respectively 31, 27 and 27 rowers on each side), ie a total of 170 oars and rowers. If the 14 armed men are added to them, there remain 16 (out of 200) to form the hyperesia, that is to say the body of the assistants of the trierarch.

This corps consisted of two teams of five sailors (one at the stern, one at the bow), and six second-masters (junior officers), the most important being the helmsman and the prow. The “inventories” also mention a fourth series of trains, the perineos, that is to say the spare trains to the number of 30 in total, which added to the others make a total rounded to 200, and are of two different lengths, 9 Angled and 9.5 cubits.

From Thucydides (5th century BC) to Procopius (6th century AD), the word is also used to designate persons on board who do not regulate their passage by rowing, as opposed to rowers (Proskopoi, Auteretai, Sortitai, etc.). Since these 9 cubits and 9 and a half cubic yards are undoubtedly spare parts, placed on board triremes to replace unused oars of the three categories, it can be concluded that all the oars had to measure either 9 cubits or 9 cubits and a half.

The reason for the difference in length has been named above and looks good. Calculating with a cubit of 490 mm, one obtains a length of 4.41 meters at the stern and the prow and 4,665 meters in the middle of the ship.

Indirect evidence concerning the trire consists of contemporary shipbuilding practices and some figurative representations of the ship. Also, from the method of construction known as “first hull” which (underwater archeology was revealed) was used at the time for merchant ships, also from the examination of the vestiges of the Prow of a warship of the end of the third century preserved in the spur of Ahlit, one can reasonably imagine the method followed to construct a trire of the Vth and IVth before our era. We also have images of warships of this period representing triremes. Two of them are important:

1. the Lenormant relief, showing the starboard center of the hull of a vessel with oars;

2. the vase of Ruvo decorated with the image of the back of a boat stranded and whose oars are bordered but whose rudder is seen. These objects date from the end of the fifth century when the trire were liner ships, that is to say long before the invention of tetris and pentères in the Athenian naval inventories.

Thanks to the direct sources, it was possible to establish that the triremes had a bridge, a hull open on the flank (parexereisia), an opening through which the Thranite oars passed, and lower two rows of portholes for the oars; The holes in the lower row were covered with sleeves and large enough to pass the head.

A pioneering project

The plans of the Olympias take into account the main characteristics that we have just described, namely: A total crew of 200 men including 170 rowers, each maneuvering a train; Three rows per oar on three superimposed levels, 31 thranites, 27 zygians and 27 thalamians on board, the thranites maneuvering their ream in a long opening (parexereisia), the hull, the zygiens and thalamiens by individual openings;

Openings of the thalamian rank with sleeves (askomata); One space for each rower two cubits; Oars of the same length outside the hull; A total building length of 37 meters, a width of 5.5 meters; A row propulsion system and details of the structure of the building based on the models illustrated on the Ruvo vase and the Nenormant relief; A hypozoma installed taut, with anchorage in prow and stern.

The traditional argument against the three-level trireme that the Lenormant relief represents is that these three levels involved distinctly different lengths of oars, a system that could not be operated satisfactorily. Against this system it was argued that it would involve 4, 5, 6 and up to 40 levels of oars in the later developed warships called tetris, penteris, hexeres, etc…, forgetting conveniently who The “alla zenzile” and “a scaloccio” swims which succeeded him (more than one man per oar), and who both put the oars on one level, could not provide an explanation for these developments. “The enigma of the trire” seemed insoluble.

The major success of the Olympias was to demonstrate without controversy that a 37-meter-long, three-level rowboat could impeccably navigate, making the data available at the moment, Was a trire of the time. It also enabled us to conclude that the name “trire” applied to a vessel having three rows of continuous rows from bow to stern on each side.

This conclusion in turn made it possible to understand exactly what the new types of ships appeared during the 6th century BC. JC, with the introduction of the practice of having several oars rowing, haemiolia, trihemiolia, and those up to 4, 5, 6 up to the monsters of 40 rowers, while always keeping in mind the remark of W. Tarn that no warships of more than 10 rowers per ream were ever used in combat.

Whatever the detailed modifications in the concept of the Olympias which would be deemed necessary after further discussions, new archaeological discoveries or new trials at sea, the success of the archaeological experiment carried out (ie, Paving the way for further work on the whole range of ancient warships) can not be denied.

“According to dr. John Coates, the report of the Olympias test campaigns, highlighted the fact that the “rowing” of this swim was done after a short training, that a space of two (888 mm) between two rowers was too small, that the ligaments of the oars should necessarily be made of green leather, provided that it remained dry, that the oars and their sleeves were to be constantly lubricated in order to be effective, As light as possible while having the best flexibility, and that with 45 strokes of rowing/minutes, the maximum power was reached.

But he also demonstrated that, modified according to these teachings, the revised Olympias could exceed the maximum speed reached and sustained for 24 hours (7.5 knots), reaching 9.5 knots, which was truly unsurpassable.

Greek Trireme facing forward – The trireme Trust

Finally, the rowers had to sit on a comfortable cushion, be protected from the sun, drink enormously in hot weather, especially for the Thalamians (lower rank) lacking air. Concerning the ship, it was also shown that the antique oars were perfectly efficient and that the ship was easily flanked, had practically no grip on the wind, which did not affect its performance, but that it could, because of its Low width, give band.

In sailing, the sail seemed to be sufficiently effective to propel the vessel at 4-5 knots per oblique wind, and in the event of a weak wind, the additional power obtained at the train resulted in speeds of 6 knots without exhausting the rowers. In the event of a standing wind, it was imperative to maneuver the rowing boat to shelter it or to cabot in a less windy place, but in this case the maximum speed did not exceed 3 knots, the effort exhausting the crew.

Extract from the archeology files, N° 183, 06/1993).

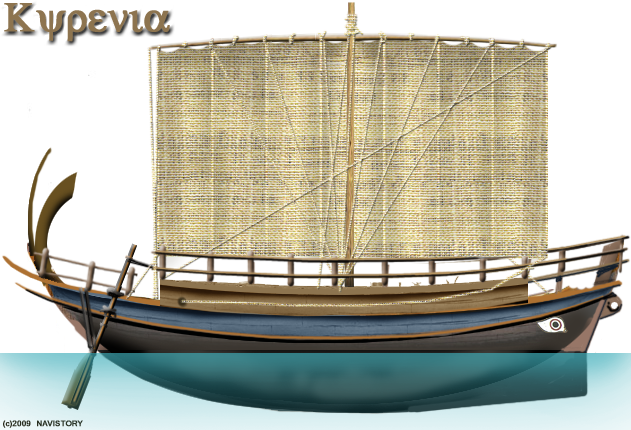

The Greek Trade Ship: Kyrenia

One might think that the explosion of maritime trade in the Mediterranean was related to its “pacification” by the Roman navy under the empire. But this was not the case. Admittedly, centuries before, piracy existed, but went on par with a flourishing trade, all around the antique sea and well beyond. During the Greek golden age, shortly before the Median wars, and the long War of the Peloponese, Phoenicians and Greeks disputed the control of trade from the east to the west of the Mediterranean.

These great navigators dotted the coasts of their trading posts, and durably influenced countries in which they settled, in good understanding with the locals, also providers of good or potential customers. And the ships which secured these connections were for the most, frail coasters beaching each evening along the trip.

A large wreck was discovered by a Cypriot diver in 1967, and later excavated by Michael Katzev (American Institute of Nautical Archeology). The site was notable, as a test bed for a range of new sampling, excavation and conservation techniques. The survey using grid computations, metal detector, proton magnetometer (revealing metal concentrations).

The cargo consisted of amphoras, many of which were coated inside the resin to counter ceramic’s porosity, so the Kyrenia apparently transported wine. Others contained remains of almonds. The lowest level of the cargo consisted of a random number of querns, possibly transported as ballast. The distribution on the wreck of the site was studied in detail.

Outside pottery found in the bow (quarter crews) also had been uncovered four sets of domestic utensils, indicating a crew of four, including plates, bowls, ladles, sifters, a copper cauldron, four cups of cooking salt, four bottles of Oil and four wooden spoon.

Despite the formation of deposits, a substantial part of the hull survived, in fact more than in any other site of the wreck of the old world. The hull was built with mortises and tenons fixed at close intervals of 12.3cm. The hull was reinforced by a number of nine-strake whales between the keel and the first whale. The frames were fixed with treenails led through the pre-drilled holes in the hull and through nailed with copper nails, which were then closed on the top surface of the frame.

Nailing by treenails has been widely used in ancient ships and boats of the Mediterranean. They served two functions, allowing a tighter fit between the tablet and treenail hole, and avoiding damage that would have been caused to the hull and frames if the nails were used as the only method of fixing. Damage caused by friction between the metal and nails of the hull frame interfaces could be further aggravated by the electrolysis reactions between the metal and some woods leading to rotting wood.

By directing the nail through a treenail the carpenter ensured that in the event of erosion of the electrolytic treenail metal and nail rot can be removed from the hull without damaging the hull itself or frames, which Would be much more difficult to repair.

The mast did not survived. Due to its general design and lightness of construction, it has been suggested that the forward and aft part has been faked, but there is no iconographic evidence for the use of these rigs in circa 4-3rd BC.

The true Kyrenia

Bronze coins dated the wreck at 316-294BC, radiocarbon dating of the hull pushed the construction date to about 345-433 BC, while the almonds dated Possibly from 212-342 BC, indicating that the ship was about 300 years old when it capsized, a good testimony to the quality of ancient shipbuilding!

Rather than lift the sections of the wreckage, it was decided to lift the whole ship. This was done by the systematic marking of all the woods after registration by drawing, photography and the new technique of stereo photography.

Objects recovered from the wreckage were well preserved, some dissected by the conservator using a saw’s jeweler. When ferrous concretions had formed around objects such as rusty nails it was possible to use a latex rubber mold, from which a copy of the original ferrous materials can be made.

Source: HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE SHIP – 44 The Kyrenia Ship. C4-3BC

Typology of ships in the antiquity

We can already point out that the sources concerning the maritime heritage of antiquity are mainly Western and centered around the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East. However, it is also possible to define the types of units that existed in South America, or in Asia.

Mediterranean:

One of the striking features of this period is the marked differentiation in the typology of boats between trade and war.

As much in the Middle Ages, in the North of Europe, this distinction made no sense any more than in the Renaissance, as the trade of expensive commodities remained risky, as much in pre-Christian Antiquity, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Babylonians, Had vessels of very distinct genera:

– The merchant vessel was by its very nature a coaster, small (less than 30 meters, at least at the beginning), light enough to be able to be climbed on the sand at night, or run aground with the tide, To carry the heaviest loads, often weighted, equipped with a large rig and equipped with a reduced crew who could also row if necessary for maneuvers in port and in calm weather.

But this propulsion was quite a minority and the main driving force resided solely in the ability to catch the wind thanks to a more developed rigging than on the Galleys.

– The military ship was all its opposite: it was long, fine, very light (at the start), narrow, its rigging reduced to maneuvers and mounted in strong winds, sometimes as a swimming aid, and its main driving force Constituted by rowers, in large numbers and integrated into the crew: A sub-distinction: In the Romans, they were not slaves (forget ben Hur): This driving force was managed with gentleness, encouragement, Rowers being considered as full crew members, enrolled for a few years and receiving a pay.

Among the Babylonians and Phoenicians, these rowers were enlisted and paid sailors, but capable of taking up arms if necessary. Among the Greeks there were free men who paid their transport by rowing, the galleys being able to fight if necessary, but not the rowers, who were relatively unprotected but well trained because the technique of sitting was rather elaborate.

SOURCES :

All the knowledge which we have at our disposal at this distant period have come to us from very few sources, direct or indirect.

“There are wrecks in the ideal.” In this case, only Greek or Roman “cargos” or Phoenicians were found, protected by a bactericidal vessel. But almost no galley (except the ship of Marsala). The explanation stems from the very special nature of these vessels:

Constructed of wood with little metal, they were very light, to the point of having a positive buoyancy coefficient, which implied that in case of ramming they remained Flooded, half submerged. They were burned or captured in general.

On the other hand, the cargo ships of antiquity transported their goods in heavy amphorae, the “standard containers” of that time, and sank with their cargo. Under a pile of amphorae, divers know that they can always find a bow or couples, a remnant of freeboard, all more or less decomposed and crushed by the clay mass of the Amphoras.

The only real enemies of the galley are fire and wear. The galleys themselves were often hoisted on a ramp built of stone or roughly dug on the shore, and protected by “hangars”.

Finding the remains of these hauling ramps gives a precise idea of the dimensions of these ships. The direct sources (wrecks) recovered are hitherto almost exclusively merchant ships. Indirect sources, such as ramps or the remains of hangars cited above, the fixing of trophies and models, or real ships, are therefore the majority.

There are also bas-reliefs, paintings and mosaics, with the limit that the ships represented were only by “generalist” artists, not by specialists in maritime techniques. Thus, among the indirect material sources, one finds the paintings and engravings on vases. The painted Greek vases in negative are particularly instructive in the matter.

Finally there are the sculptures, such as the Roman rostrums and prows on the columns, but also the artisanal objects, which although functional may represent a ship, even roughly. Finally, there are the monuments, such as the one commemorating the battle of Actium, made up of the rostres of the captured galleys (a precious indication because simple calculations then make it possible to define the size and the tonnage of the carrying ship).

There are also the indirect written sources found concerning the organization of the fleets, types of units, legislation, etc. When the navy began to codify, serious sources of information were available. Unfortunately largely destroyed in the frequent fires, including that of the great Library of Alexandria.

There were also indications given by chroniclers of the time or post-antique, the translators of the Middle Ages, the clues and indications of the great stories. For example, the ships used by certain Gaulish tribes of Britanny are known to us in detail thanks to the famous “The Gallic Wars” by Julius Caesar…

> Concerning South America, there are the traditional boats still built in the Andes, with a technique that approximates most primitive skiffs of the great rivers of the Middle East or Asia, boats in rushes. But the very symbolic graphics of the oldest Mesoamerican civilizations are not explicit on the techniques of construction.

The Nazcas, Mayas, were not commercial or maritime powers. The raft of the Jangada (Brazil) found in the mud is undoubtedly the oldest testimony available for this continent (5000 years BC). It confirms in any case the preeminence of river navigation on coastal and offshore navigation, according to a logical chronology because it is linked to the empirical progress of technology.

The Chinese junks, also spread throughout most of Asia, are at the origin of the rafts, intimately linked to the Chinese “Nile”, the yellow river. These massive “rafts” have been improved many times, adapted to coastal navigation, then to the Middle Ages, high seas and even oceanic.

Detailed Typology:

- Merchant Ship of Ancient Egypt (3000 BC)

- Merchant Ship of Ancient Egypt (2600 BC)

- Merchant ship of Queen Hatshepsut (1500 BC)

- Kepen 1600 BC

- Kepen 1400 av JC

- Ptolemaic Triere (100 BC)

- Kheops Funerary Ship (2500 BC)

- Keftion 800 BC

- “Fourth” of the Antigonids (360 BC)

- Ptolemaic Tesseraconter (80 BC)

- Ptolemaic Diere (90 BC)

- Ptolemaic Hepter (70 BC)

- Mithridate’s Hemolia (70 BC)

- Phoenician Trading Ship (270 BC)

- Assyrian Dier (600 BC)

- Phoenician Merchant Coaster (800 BC)

- “20” of Cleopatra (Actium, 31 BC)

- From the MGM “Cleopatra” movie, by Cecil B. De Mille

- Roman Pentecontore (230 BC)

- Roman Triconter (220 BC)

- “10” or Imperial Roman Decere (50 BC)

- Roman Actuaria (200 BC)

- Carthaginian Penteconter of Hannon and Himilcon (180 BC)

- Assyrian Dier of Sennacherib (800 BC)

- Greek Trikonteros (600 BC)

- Greek Pentakonteros (400 BC)

- Corinthian Triere of Ameinocles (400 BC)

- Greek Cisokonteros (500 BC)

- Greek Cargo 500T (500 BC)

- Roman Biremis (250 BC)

- Roman Triremis of Scipio (217 BC)

- Imperial Deceris (70 BC)

- Quinqueremis from Agrippa at Actium (31 BC)

- From the film of the MGM “Cleopatra”, by Cecil B. De Mille

- Deceris of Antoine at Actium (31 BC)

- From the film of the MGM “Cleopatra”, by Cecil B. De Mille

- Carthaginian Tetrere of Hamilcar (260 BC)

- Greek Trikonteros (300 BC)

- Roman Quadriremis (40 BC)

- Oneraria (80 BC)

- Cargo of wheat from Alexandria

- Triere of Themistocles (500 BC)

- Roman Corvus Triremis (not to scale), Imperial period (50 AD).

- Greek Liburna (60 BC)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign