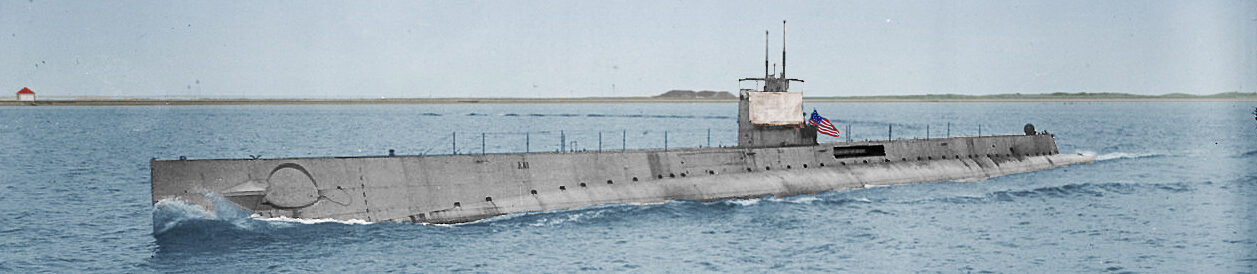

US Navy Submersibles, USS Salmon, Seal, Skipjack, Snapper, Stingray, Sturgeon SS-182-187 (1936-48)

US Navy Submersibles, USS Salmon, Seal, Skipjack, Snapper, Stingray, Sturgeon SS-182-187 (1936-48)WW2 US submarines:

O class | R class | S class | T class | Barracuda class | USS Argonaut | Narwhal class | USS Dolphin | Cachalot class | Porpoise class | Salmon class | Sargo class | Tambor class | Mackerel class | Gato class | Balao class | Tench classThe Salmon-class were six submarines built in three yards for the USN in 1936-38. They were an important developmental step before the wartime Gato/Tench/Balao and in general a maturation of the concept of “fleet submarine”. There was no revolution in design as they were essentially an incremental improvement over the previous Porpoise class (declined into three sub-classes). They were the first class capable of achieving 21 knots making them compatible with “Standard” type battleships with a reliable propulsion plant. They fixed a standard construction design for the pressure and outer hull and added the bonus of a 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) unrefueled range which opened to them Japanese home waters. And they were the first to be built in more substantial number (six) than any other previous class. In WW2 they were juged rugged and dependable, just like their successors the similar Sargo class, which were assimilated by some authors collectively as the “New S Class” (1st and 2nd Groups). However for the sake of diving in their deep career, they will be separated. They accumulated indeed a substantial number of battle stars. Basically the larger Gato class which design dated from 1940 were just stretched versions of the “S” class, not bounded by treaty limitations anymore.

Development

The new Salmon class were authorized under FY1936 provision of the Vinson-Trammell Act*, and distinct in some respects but almost identical designs were developed, to be given to three different constructors. At this stage, the USN was still not fixed on a standard type yet as all previous designs presented some design advances but also flaws. This had been incrementally since the wild experimentations of the V types in the 1920s. But since 1917 already there had been a quest coming back year after year and yet never really fulfilled: To be able to create a true “fleet submarine”, which could operate with and around a battle fleet, as a useful auxiliary. The idea was as old as the “standard” class battleships, defined approx. in 1915 with the Nevada class when it was decided to standardize top speed and armament (21 inches and 13.5 inches guns) in order to ease command and control of the battle formation.

*The first Vinson-Trammell Act Emergency Appropriations Act of 1934 by Congressman Carl Vinson, “The Father of the Two-Ocean Navy”. In 1931, Vinson became chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee and indeed constantly pushed to increase funding of the USN. In that he probably prepared it better to face the Japanese in 1941. The second Vinson act mandated a further 20% increase in strength of the United States Navy and allocated $1.09 billion for it when enacted in May 1938. It notably funded 13,658 tons of submarines (8 vessels built under this authorisation: SS-204 to SS-211, the 1940 Mackerel class, last before the Gatos). A Nimitz class carrier was named after him, a well deserved honor after he passed out in 1981.

The 1918 T class were the first attempt at a 21-knots fleet submarine.

Destroyers and scout Cruisers needed to be ten knots ahead for reconnaissance, but not submarines, whic traded stealth for speed. But the bare minimum was to follow a battle fleet, and if such speeds were sometimes reached, each time powerplants failed to meet expectation. This has been a long, arduous and painful learning curve sinche the T class submarines and the new S class were now symbolically about to make this a reality.

In 1935 Electric Boat Company of Groton in Connecticut was contracted to design and built USS Salmon, Seal, and Skipjack (SS-182 to 184) which would be the prototypes of this new type. The Navy submarine design bureau at the time in Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (Kittery, Maine) submitted a design for the Government group in its turn (admiralty design of you will), which became USS Snapper and Stingray (SS-185 & 186) and the Portsmouth plans were given to a follow yard at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, for USS Sturgeon (SS-187).

The launch of USS Salmon at Electric Boat in Groton, Mass. navsource

Design Differences between EB and Portsmouth Designs

The latter two designs only differed in minor details: Locations of the access hatches for the forward engine room/crew’s quarters, shape of the horizontal conning tower cylinder, closure of the main induction valve. The latter was proven latter to be very problematic as it cost losses of lives on Snapper and Sturgeon, and complete loss of USS Squalus.

The 1st design by Electric Boat, the historical leader, went for a generally Larger boat than the Porpoise-class. Its conning tower was different from Portsmouh boats, having two concave spherical ends, while the second had a concave end aft, convex forward. Small differences but under pressure it could prove instrumental. However unlike Electric Boat, noth Portsmouth and Mare Island ran into production issues with their cast conning towers. Cracks were discovered later and these failed under required pressure test, so before commission. This issue was solved by carseful re-casts but this experience forced government yards to adopt the simpler and more resistant double concave design of EB for the next classes.

Model of the Salmon by EB in 1936 (navsrc)

Externally, differences were in the upper edge, aft end, shape at the conning tower fairwater. The Electric Boat design used a gradual downward taper on its bulwark, whereas the navy design was a bit higher and more straight. The Electric Boat submarines were given two 34 foot periscopes, resulting in a fairly small periscope shear support structure above the fairwater whereas Navy boats combined a 34 foot and 40 foot periscope making for a taller, more conspicuous shear and support stanchions.

Differences with the previous Porpoise class

The former Electric Boat Porpoise design was all-welded, while sub-class were of mixed construction. On the government side (Portsmiuth Yard) construction had been more conservative by keeping the tried and true riveting. Electric Boat eventually proved this was a superior design, making for stronger and tighter boats, lighter and less prone to leakages after river failures, especially under duress depht charge attack. This also prevented oil leakage after the same attacks, revealing the position of the submarine. But all that had to wait for wartime experience. In between, the cause of EB’s engineing gained traction based on these arguments, and finally convinced Piblic yards to the efficience of this method, so Portsmouth’s take on the new Salmon class was to convert without reserve to welding. When in combat, the Navy only had only praises for this move, unlike previous boats, that were criticized in 1942.

The six Salmon class still were very much a repeat of the later batches of the Porpoise class. The latter was deemed successful overall but still, valuable lessons were learned from from their early operating experience, which explains the important gap between them and the Salmons. It was agreed to just make them larger, traduced as longer and heavier, with a better internal arrangement that could free more space in the machinery and install a better and more powerful powerplant. This made on paprt for a faster version of the Portpoise, with the addition of two additional torpedo tubes aft, for four forward and four aft, another critical difference.

These extra aft tubes were also largely the result of the new Torpedo Data Computer adopted for the Portpoises, making broadside attacks less practical and more stern tubes desirable. Although submariners wanted six tubes forward there were technical limitations for this. In UK the same desire led to a mix of pressure hull (reloadable) and outer tubes to reach as much as ten tubes for the T class, contemporary of the Salmons. But it did not matched tactics of the time. One aspect was also important. For years it was believed that tonnage needed to be freed from treaty limitations to allowe extra tubes. It was also believed that compensating by finding more space for torpedoes inside was the best compromise.

In fact, four non-firing torpedo stowage tubes were installed in the superstructure, below the main deck were there was still extra available space. They were stacked vertically, two each on either side of the conning tower. To access them, only surfacing and removing a portion of the decking on either side of the deck gun coukd grant access to these, as well as mounting a small tripod winch chain to lift them up to the main deck. They were then placed on a raised loading skid and then lowered at the perfect angle to slid down through the reload hatch down to the forward torpedo room, process which required calm waters and several hours. Manage to pass them through the reload hatch further forward was hazardous at best with rain and a slippery deck plus violent motion. The traditional small stowed boat previous use to sail to shore was eliminated and rubber boats stowed elsewhere.

Overall this new arrangement specific to the class proved impractical. Being close to the Japanese Home Islands, staying surfaced in enemy waters for so long was just a risk rarely taken by sub captains that knew better. This led to the removal of these tubes in wartime overhauls.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

These six submarines and subsequent U.S. Navy sub designed until the end of WW2 featired the now standard “partial-double hull”, judged the best compromise. This called for an inner pressure hull wrapped by an outer hydrodynamically smooth hull, close to it but with blister like sides and a prominent free space created by the outer flat deck. The space between hulls created the ballast and housed fuel tanks. The outer hull smoothly tapered into the pressure hull forward and aft, with strong torpedo room bulkheads. The pressure hull thus was thus exposed at both ends but that was seen as an advantage however for maintenance and repairs.

The new Salmon class displaced 1,435 long tons (1,458 t) standard, surfaced and 2,198 long tons (2,233 t) submerged versus 1,316 long tons surface, 1,934 long tons submerged for the Porpoise. They were longer at 308 ft (94 m) versus 301ft (92 m) or 91.4 meters at the waterline and 93.9m overall. They were beamier at 26 ft 1.25 in (7.96 m) versus 24 ft 11 in (7.59 m) making for a better lenght-to width ratio. They were also draftier for extra stability, at 15 ft 8 in (4.78 m) versus 14 ft 1 in (4.29 m). This, combined with records of engineering resourcefulness, ingenuity and innovative ideas, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in internal arrangements, making extra space for four more torpedoes and larger engines, while not destroying livable spaces. It was just clever internal layout, the fruit of experience wit the previous boats. This also set a pattern in terms of internal arrangements for the next designs, Sargo, Tambor and Mackerel.

Powerplant

The new class was very different in terms of powerplant, which was far more extensive thanks to the extra space found. Engineers had to go through many companies to find the rare breed, and tested dependiong on the yards, either General Motors-Winton diesels, or Hooven-Owens-Rentschler (H.O.R.) diesels. What mattered was the use of four, smaller yet powerful diesels instead of just two. Of these four diesels, two were used on direct drive, and two were driving electrical generators, but coukd be coupled for added output. They generated 1,535 hp (1,145 kW) each versus two Winton diesels rated for 1300 hp each. This more than doubled the output of previous boats, thus reaching the conveted 21 knots in top speed when surfaced, instead of 18 knots. This was an amazing jump of four knots, something which was looked for two decades. Now these boats were able to follow battle fleets.

Underwater speed was not negliged either. In addition to two 120-cell batteries like the previous boats, they had four high-speed Elliott geared electric motors rated for 665 hp (496 kW) each (2260 hp), compared to four 421 hp units, so there too, quite an increase in power, leading to a top speed of 9 knots instead of 8 knots. To toppled it of, there were two auxiliary diesel generators rated for 330 kW (440 hp) each as a backup, versus three EDEM on the Porpoises.

The net result of all this was a total of 5,500 hp (4,100 kW) surfaced and 2,660 hp (1,980 kW) submerged.

The greatest difference was this 21 knots surfaced versus 18 knots and 9 submerged versus 8 knots of the Propoise. This really was a game changer.

As fore range, they were capable of 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) surfaced at 10 knots (19 km/h) based on 384t oil versus 350t oil, and 6,000 nmi at 10 knots and 50 nm underwater at 5 knots. The Salmon class were capable of cruising 48h submerged at 2 knots (3.7 km/h) over 96 nautical miles.

Two different main diesel engine types installed in during construction varied between yards with the Government boats receiving the new GM-Winton 16-248 V16. Development work by GM-Winton under the whip led tthem to overcome all previous issuesn and through intensive testings create at last a fairly reliable and rugged engine. The three Electric Boat vessels however went for a more exotic solution, sources after many visits and finding their golden eggs hen. This was the nine-cylinder version of the Hooven-Owens-Rentschler (HOR) double-acting engine. This promising solution, also marketed to aviation, derived from a very successful …steam engine. They were innovative as for their small size, they had a power stroke in both directions of the piston, generating twice as much horsepower as for a conventional in-line or V-type engine. But Electric Boat’s choice, albeit promising, proved to be a risky one.

The power unit was still relatively recent and eventually prone to severe design and manufacturing issues when turning into internal combustion. They vibrated excessively, a result of the twin stoke imbalance in the combustion chamber. Engine mounts broke down, and the drive train was severely stressed. Improper manufacture of the gearing added to the misery by resulting in a broken gear teeth. The Navy still appreciated the find by EB and coddled the HORs still. But as the Pacific War broke out, between increased funding and operational needs they were ultimately replaced by larger, more traditional but true and tested GM-Winton 16-278As in their first overhauls.

On aspect that was desired for the new Salmon was the result of the disappountment caused by the Porpoise-class diesel-electric drive. It was decided to radically modify the propulsion plant and fitted a “composite drive”: The two main engines located the forward engine room drove generators in like for the Porpoises but there was now an after engine room in which two side-by-side diesels were clutched to reduction gears forward of the engines, using vibration-isolating hydraulic clutches. The propeller shafts whent through these reduction gears, sitting outboard of the engines and two high-speed electric motors were mounted outboard of each shaft as well and connected directly to the reduction gears. This was a complicated arrangement, but on paper, able to deliver both more power and reduce vibrations.

While surfaced the engines were clutched in to the reduction gears, driving the propellers directly, having the two diesels kept as generators providing additional power though voltage to the electric motors. So this made for a true “diesel eletric” drive surfaced. Only way to reach 21 knots in a satisfactory manner given past lessons. When submerged, direct drive engines were declutched from the reduction gears, the motors drove shafts with electricity from the batteries. This a snot all rosy though as this unusual arrangement was cramped and maintenance and repairs proved more difficult. The new arrangement managed to overcome fears advanced by a number of experts, about insufficient damage tolerance of electrical transmission which could be easily incapacitated at any power cable damage. Fortunately, the ww2 Gato class with their displacement free stance allowed to solve these issues of maintenance with extra space.

Armament

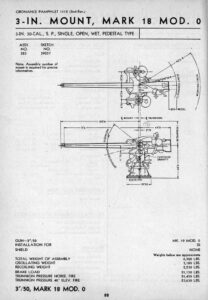

3-inch/50-caliber gun Mk 17/18

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Marks 17 and 18 were installed on the Cachalot class, first used on R-class submarines launched in 1918–1919.

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Marks 17 and 18 were installed on the Cachalot class, first used on R-class submarines launched in 1918–1919.

The Mark 17 guns had a Mark 11 mounting and the Mark 18 guns had the Mark 18 mounting. Importantly enough, the gun was located aft of the conning tower. Image: 3-in/50 Mark 18 specs and sheet, src HNSA via navweaps.

⚙ specifications 3-in/50 Mark 18 |

|

| Weight | 6,500 Ibs |

| Barrel length | 120 inches |

| Elevation/Traverse | -15/+40 degrees |

| Loading system | Manual, vertical sliding wedge type breech |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,700 fps (823 mps) |

| Range | 14,000 yards (12,802 m) at 33° |

| Guidance | Optical |

| Crew | 6 |

| Round | 24 lbs. (10.9 kg) AP, HC, AA, Illum. |

| Rate of Fire | 15 – 20 rounds per minute |

The Porpoise like the Cachalot class had four tubes in the bow and two in the stern and from 1942, six in the bow and carried initially 16 torpedoes, between the bow tubes, two in stern tubes and reloads for sixteen total. In contrast, the design solutions found for the Salmmon guaranteed 24 torpedoes. Eight were already pre-loaded in tubes, there were eleven reloads in the pressure hull, which was amazing by itself, and the remainder four were stored close to the conning tower in vertical tubes, but this needed long hours and lake-like conditions to proceed to the rextraction and reload process, while surfaced. Needless to say, they were eliminated at the first occasion and the class sported still twenty torpedoes instead of sixteen, nothing to shy about. The only issue was the type used, the now infamous Mark 14. Fortunately there were still stocks of the older Mark 10 aplenty.

Mark 10

These boats were capable of firing the 21-inches Mark 10 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark 10, a 1917 design entering service in 1918. From 1927 these were the Mod 3, last designed by Bliss and manufactured by the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport. They equipped R and S boats, most V Boats, The Cachalot, Porpoise and others, and soldiered in World War II as a trusted straight course unlike the infamous Mark 14. Before the latter had its defaults ironed out in 1942-43, the Mark 10 was in high demand and stocks starting to dwindle down rapidly. Production was maintained until 1943.

⚙ specifications Mark 10 Mod 3

Weight: 2,215 lbs. (1,005 kg)

Dimensions: 183 in (4.953 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater

Range/speed setting: 3,500 yards (3,200 m) / 36 knots

Warhead: 497 lbs. (225 kg) TNT or 485 lbs. (220 kg) Torpex

Guidance: Mark 13 Mod 1 gyro

Mark 14

In 1941 she carried the Mark 14, entering service in 1930. Designed replacement for the Mark 10, this was the new standard. Unfortunately the model was infamous for its legendary unreliability, explaining the poor results obtained in 1942 and until mid to late 1943; Long story short, the Mark 14 was a revolutionary new model that was tailored to use a gryroscope combined with a magnetic pistol. The principle was not to detonate on impact, but use magnetoc proximity of the enemy hull to explode ideally under the hull of the target. This way, it was easier to break its hull instead of just making contact below the waterline. These torpedoes were designed at the Naval Torpedo Station Newport, Rhode Island from 1930 and considered state of the art, benefiting from a $143,000 budget for its development. Production was pushed forward after testings, and at 20 ft 6 in (6.25 m), it was incompatible with older submarines’ 15 ft 3 in (4.65 m) torpedo tubes, like the R and O classes. It was also the best performer, capable of 4,500 yards (4.1 km) at 46 knots (85 km/h).

Lots of promises, but the war proved that testings had not been thorough and the rate of misses compared to the Mark 10 became obvious in reports in 1942, this infuriated many captains that disabled the magnetic pistol, but did not solve the problem as it was proved later that their too fragile impact fuse was also faulty.

Responsibility lied with the Bureau of Ordnance, which specified an unrealistically rigid magnetic exploder sensitivity setting while not providing enough funding to a feeble testing program. BuOrd had a hard time later accepting it and enable a new serie of tests, which were mostly from private initiatives.

Only by late 1943 and early 1944 most problems had been allegedly fixed, so that the 1944 Mark 14 at least allowed captains to claim far more kills. The “mark 14 affair” sparkled a lot of controversy postwar and it’s not over.

⚙ specifications Mark 14 TORPEDO

Weight: Mod 0: 3,000 lbs. (1,361 kg), Mod 3: 3,061 lbs. (1,388 kg)

Dimensions: 20 ft 6 in (6.248 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater steam turbine

Range/speed setting: 4,500 yards (4,100 m)/46 knots, 9,000 yards (8,200 m)/31 knots or 30.5 knots

Warhead Mod 0: 507 lbs. (230 kg) TNT, Mod 3: 668 lbs. (303 kg) TPX

Guidance: Mark 12 Mod 3 gyro

Sensors

QCC sonar: The QC/JK gear was located in the Conning Tower, companion units with the QC gear as active/passive sonar and JK gear (passive only). Raides and lowered by a hydraulic system, training by electric motor controlled by handle in the operating station. QCC: No data.

JK sonar: The JK/QC combination projector is mounted portside. The JK face is just like QB. The QC face contains small nickel tubes, which change size when a sound wave strikes this face. (The NM projector, mounted on the hull centerline in the forward trim tank, is used only for echo sounding.)

Se the full reference here

Modernizations

USS Sturgeon after her major overhaul reconstruction and modernizatiion at Hunters Point NY, San Francisco CA in April 1943. White outlines mark recent alterations, among them the relocation of Sturgeon’s 3/50 deck gun, installation of watertight ready service ammunition lockers in her sail, and fitting of 20mm machine guns. Note the large concrete weight on deck, indicating that Sturgeon was then undergoing an inclining experiment to check her stability. 19-N-46405

In 1942-1943 the Portsmouth (and Mare Island) boats had their conning tower rebuilt as the Electric Boat models, and their 76mm (3 inches)/50 deck gun and two 0.5 in or 12.7mm/90 Browning HMG removed. The dedck gun was replaced by a more powerful 4-inches (102mm)/50 Mk 9 or in some cases even a 5-inches (127mm)/25 Mk 17. The sail was completely arased and rebuilt to the new low standard of the Gato class with platforms fore and aft for 20mm/70 Mk 4 Oerlikon AA guns. The new portical around the periscopes supported the SD and SJ radars used for navigation and aerial warning. SS183 to 187 (all but USS Salmon) also operated the QCC and JK sonars.

⚙ Salmon class specifications |

|

| Displacement | 1,435 long tons standard, 2,198 long tons submerged |

| Dimensions | 308 ft x 26 ft 1.25 in x 15 ft 8 in (94 x 7.96 x 4.78 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 diesels 1535 hp, 4 Elliott EM 440 hp, 2 batteries |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h) surfaced, 9 knots (17 km/h) submerged |

| Range | 11,000 nm (20,000 km) at 10 knots |

| Max service depth | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Armament | 8x 21-in TTs (4 fwd, 4 aft, 24 torpedoes), 1×3 in/50 deck gun, see notes |

| Sensors | QCC-JK suite, SD-SJ radars 1942-43 |

| Test Depth | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Crew | 5 officers and 54 ratings |

General Evaluation

USS Skipjack pending her fate close to USS Skate (SS-305) at Mare Island Shipyard in October 1947.

In the end, Portsmouth proved efficient in production methods, managing to complete and commission Snapper and Stingray before Electric Boat delivered USS Salmon for commissioning, despite the fact she was launched earlier. All three of the Government boats managed to beat a private yard into service. It’s not impossible that F.D.Roosevelt was stranger to this, but this was compounded by the choice of engines, as the navy stuck to its guns with the same diesel manufacturer and was confident in its abilities to make a reliable, rock solid product thanks to close monitoriing, unlike the risk taken by EB with a very innovative but hazardous adaptation of an engine. EB compensated by a better connign tower design. In the end, the Salmon class, with its addioan tubes and many torpedoes, and overall, greater speed immensely pleased the Navy. At last after nearly twenty years (1918-1938), they had their first true “fleet submarine”.

The Salmon class clearly showed the way forward, exploited by the Sargo and Tambor, leading directly to the Gato class, which won the war in the Pacific. They were the indispensible stepping stone towards an all-excellent package, and a truly remarkable achievement compared to contemporary designs, especially within treaty limits. This was translated directly in stellar watime records, accumulating almost 60 battle stars together and unit presidential citations.

After commissioning in 1938 as tensions sharply rose both in Europe and Asia, they proved very active, operating initially with the Atlantic Fleet, Caribbean and venturing on both sides of the Panama Canal and then transferred to the Pacific by late 1939, San Diego under COMSUBPAC Admiral Wilhelm L. Friedell. By October 1941, the Salmons, Sargo and Tambor were all transferred to the Asiatic Fleet and the Philippines. The Japanese occupation of southern Indo-China in August 1941 and joined retaliatory oil embargo further raised tensions and found these boats in Cavite, Manila Bay on 7 December. They will accumulate quite a tally and more remarkably despite their numerous missions notably in Japanese home waters, none were sunk. The only one not scrapped in 1946-48 (Seal was retained as reserve TS until 1956), USS Skipjack, future namesake for the first SSNs, ended in the nuclear test of July 1946.

Read More/Src

USS Sturgeon, last in class, post launch on 15 March 1938 with yard’s worker on board. Note the hull sides launch aiming markings and very high freeboard. She was essentially empty and unstable at this point. Via www.navsource.org, USN photo # 274-38 courtesy of Darryl L. Baker.

Books

Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis NIP

Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990 Greenwood Press.

Whitman, Edward C. “The Navy’s Variegated V-Class: Out of One, Many?” Undersea Warfare, Fall 2003, Issue 20

Alden, John D., Commander, USN (retired). The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy Annapolis NIP 1979

Johnston, “No More Heads or Tails”, pp. 53–54

Blair, Clay, Jr. Silent Victory. New York: Bantam, 1976

Lenton, H. T. American Submarines (Navies of the Second World War) Doubleday, 1973

Silverstone, Paul H. U.S. Warships of World War II Ian Allan, 1965

Schlesman, Bruce and Roberts, Stephen S., “Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants” Greenwood Press, 1991

Johnston, David, “No More Heads or Tails: The Adoption of Welding in U.S. Navy Submarines” The Submarine Review, June 2020

Campbell, John Naval Weapons of World War Two. Naval Institute Press, 1985

U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History Hardcover – Illustrated by Norman Friedman.

The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy: Design and Construction History Hardcover 1979 by John D. Alden.

Whitman, Edward C. “The Navy’s Variegated V-Class: Out of One, Many?” Undersea Warfare, Fall 2003, Issue 20

Gardiner, Robert, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946, Conway Maritime Press, 1980.

Links

pigboats.com Salmon/Sargo_Class

salmon on pigboats.com/

salmon class plans as modified 1944 on pigboats.com

on navypedia.org/

on navsource.org

on laststandonzombieisland.com/

navweaps.com/ 3-in/50 mk10-22

zerobeat.net/ sub-sonar.html

on en.wikipedia.org/

on twz.com/

USS Salmon battle damage assessment plans Buships 1944

Cutaway of the Salmon class

Same in HD on the blueprints

salmon photos on navsource.org

biblio.org/ JANAC-Losses/ salmon

Submarine Report Depth Charge, Bomb, Mine, Torpedo and Gunfire Damage Including Losses in Action 7 December, 1941 to 15 August, 1945

Model Kits

Videos

USS Salmon SS-182

USS Salmon SS-182

Salmon was the lead boat of a group of three built at Electric Boat, ordered and laid down on 15 April 1936 based on a winning design, launched on 12 June 1937 and completed on 15 March 1938. After trials, shakedown and training on the Atlantic coast, Carribean in winter and Nova Scotia in summer, USS Salmon was assigned to SubRon 15, Squadron 6, Atlantic Fleet homeported to Portsmouth and flagship of her division until her sister Snapper took over in late 1939 when ported to San Diego.

She trained along the West Coast in 1940 and most of 1941 until transferred with her division and the tender USS Holland, to the Asiatic station which was from 18 November based in Manila and now SubDiv 21 in growing tension. In december 7, Salmon was in a first patrol from Manila along the west coast of Luzon, already on defensive deployment since 27 November. On 22 December while surfaced in Lingayen Gulf she was spotted by two Japanese destroyer and started an attack, damaging both with a “down the throat” torpedo spread catching them when veered course. She managed to flee in a rain squall.

In January 1942 she patrolled in the Gulf of Davao and south Mindanao, underway to Manipa Strait (Bura-Ceram) in the Molucca and in February she was in the Flores Sea, Timor-Lombok Strait and Sunda Islands, until joining as ordered Tjilatjap, Java on 13 February. Bali airfield fell on 18 February 1942 while ABDA was gutted, so she had to flee the new base in Surabaya and the tender Holland departed for Australia, Exmouth Gulf, arriving on 20 February. Salmon soon started her second war patrol in the Java Sea, Sepandjang and Bawean. She returned to Fremantle on 23 March where the base was relocated.

Her 3rd war patrol started from Fremantle on 3 May and she made a barrier patrol along the south coast of Java, try to catch Japanese shipping. On 3 May she sank the 11,441-ton repair ship IJN Asahi. On May 28th, she sank the 4,382-ton passenger-cargo vessel Ganges Maru, and was back to Fremantle.

She started her 4th patrol on 21 July and headed for the South China Sea and Sulu Sea via Lombok and Makassar, Sibutu, Balabac Strait and ended in ambush between North Borneo and Palawan. She missed an attack, but reported shipping movements and returned to Fremantle on 8 September.

Her 5th patrol started on 10 October, off Corregidor and Subic Bay. On 10 November she caught while surfaced and challenged a large sampan, ordered to stop and fired across the bow and after quick recoignition sank with her Browning heavy machine guns before being boarded, with Japanese sailors jumping off and swimming away. Papers, radio equipment were recovered and the sampan sunk.

On 17 November off Manila Bay she sighted three ships and prepared for attack, fired torpedoes at each, damaged two, sank the 5,873-ton, converted salvage vessel, Oregon Maru. Her 5th patrol started from Pearl arter a refit on 7 December, then overhaul at Mare Island from 13 December, completed by 30 March 1943 and back to Pearl Harbor on 8 April. Her 6th patrol started on 29 April 1943 via Midway to the coast of Honshū, surveying Hachijo-jima, Kajitorizaki, Izu Ōshima. She damaged two freighters on 3 June and was back to Midway Island on 19 June.

Her 7th patrol was in the icy Kuril Islands to prey on the Paramushiro-Aleutian supply route, sailing on 17 July. Claimed a small coastal patrol vessel on 9 August, and the 2,411-ton Wakanoura Maru off Hokkaidō the following day, back to Pearl on 25 August. Her 8th war in the Kuril Islands was paid by two freighters (27 September to 17 November).

Her 9th war patrol (15 December to 25 February 1944) saw one freighter damaged on 22 January. On 1 April for her 10th patrol, she left Pearl Harbor for Johnston Island with USS Seadragon for special photo reconnaissance mission patrol fopr the future assault of the Caroline Islands, off Ulithi (15-20 April), Yap (22-26 April) and Woleai (28 April-9 May) and back in peal on 21 May.

For her 11th and last war patrol with USS Trigger and Sterlet she was part of a wolfpack in the Ryukyu Islands, sailing from 24 September. On the 30th she finished off a large tanker already torpedoed by Trigger but had to deal with 4 antisubmarine patrol vessels, with 2 hits, but dive deep under the most severe depth charge attack of her career, first to 300 feet (91 m) then 500 feet (150 m) taking a lot of punishment, uncontrolled leaking. She was forced to surface for a final combat. Escorts CD-22 and CD-33 spoted her and closed in. She turned away to correct a bad list, repair damage, but they were hard on her heel, and eventually she turned, passing just 50 yards (46 m) from CD-22, pounding her with 20 mm gunfire and deck gun (4 killed, 24 wounded, unable to reply as too close and higher freeboard). Salmon also called other subs to help and the two escorts veered away while usind sound gear. Salmon fled in a rain squall, slipping away, nut in very bad shape. This was a fighting miracle. She only suffered from small-caliber hits. She was escorted by Sterlet, Trigger, and Silversides to Saipan. She was co-credited with the 10,500-ton tanker Jinei Maru, finish off for good by Sterlet (5 torpedo hits between three subs). On 3 November she joined her new sub tender Fulton in Tanapag Harbor for initial repairs.

On 10 November she returned to Pearl with USS Holland, via Eniwetok and to San Francisco. On 26 January 1945 she crossed the Panama Canal to Portsmouth, arriving on on 17 February for full repairs and overhaul, but assigned as training vessel, Atlantic Fleet until decommissioned on 24 September, stricken on 11 October, BU from 4 April 1946. She earned 9 battle stars and was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for “extraordinary heroism against enemy surface vessels during her eleventh war patrol in restricted, enemy-held waters of the Pacific” in her last die hard engagement.

USS Seal SS-183

USS Seal SS-183

USS Seal was the second laid down at EB on 25 May 1936, launched on 25 April 1937 and completed on 30 April 1938. She had an extended shakedown cruise in the Caribbean, post-shakedown yard time, and joined New England by late November, then Panama for Coco Solo on 3 December and Balboa until January 1939 before Pearl Harbor and Fleet Problem XX. She trained with DesDiv 4 off Haiti before being overhauled in New London, notably a change of main engines. In June she sailed for San Diego and Pearl Harbor and until September, took soundings for the Hydrographic Office and exercises. She was back in San Diego in 1941 but soon SubDiv 21 departed on 24 October for Manila. 34 days later she started her first war patrol to intercept the Japanese off northern Luzon after the landings of Vigan and Aparri in Cagayan. She awas near Vigan on 20 December. On the 23th she spotted and sank Hayataka Maru.

Next she patrolled Lingayen Gulf, and from January 1942, Lamon Bay, crossing Cape Bojeador for Cape Engaño and the moved to Tarakan, Borneo, and Minahasa, Celebes via Molucca Passage, sruvey traffic to Kema. On 27 January she was ordered off Kendari before heading for the new allied base at Soerabaja on 5 February. She had engines issues and a broken periscope prism control mechanism. On 11 February she sailed for her 2nd patrol on the south coast of Java. On 14 February she joined USS Holland. But she had to depart Tjilatjap via Lombok Strait for Australia, while herself started her 2nd patrol north of Java. On 24 February of twi convoys, she only damaging a single freighter, and later an enemy formation. She patrplled off Makassar City but soon had her conditioning unit broken down, refrigerating plant inoperable so on 21 March she sailed for Fremantle. Her 2rd patrol started on 12 May via the Malay Archipelago, Celebes Sea, Sulu Sea and Indochina coast. On 28 May in the South China Sea she sank 1,946-ton Tatsufuku Maru. On 7 Jun off Cam Ranh Bay she attacked an eight-ship convoy but had toi survived a 7-hour depth charging. From 15–17 June poor weather hampered operarions and on 18 June a leak was discovered on her starboard side., she left for Balabac Strait, Makassar Strait and back to Fremantle.

For her 4th patrol (10 August-2 October) she remained on the Indochina coast and from Cape Padaran. 11 sightings but dubious torpedo performance against shallow draft vessels, premature explosions (Mark 14) while having herself leaky exhaust valves and holes in the fuel compensating line, leaking oil to the surface. Damaged a single cargo on 3 September.

On 24 October she left Australia for the Palau area and on 16 November, intercepted a convoy of five cargos in two columns plus destroyer escort but soon after firing, she collided or was rammed by a IJN vessel, periscope went black, vibrating. She rosse to 55 feet and plunged again before a deluge of depth charging until reaching 250 feet (76 m). When estimated clear she surfaced to see her main periscope was bent down and low periscope housing sprung, radar antenna broken off. The crew recovered uncooked rice and beans but also captured Japanese documents. It’s well possible she hit a freighter’s hull. On 17 November she was ordered back to Pearl Harbor, arrived on 30 November, repaired fully at Mare Island.

On 2 April 1943 modernized as well, she was back to Hawaii and started her 6th war patrol. On 18 April she in Midway. On 1 May, she patrolled off Palau and on 2 May attacked a freighter, missed and was chased off. On 4 May she sank San Clemente Maru and was back to Midway on 3 June. On 24 June she was back at sea and sailed to Todo Saki NE Honshū coast but on 8 July, she was located, chased and depth charged for ten hours. Her position was given by air and oil leaks.

She was back to Pearl Harbor on 24 July for repairs and at sea by mid-August for the southern Kuril Islands. On 31 July when diving her conning tower hatch failed to latch, flew open, pumproom flooded before she could surface. She had short circuits and had to retire for temporary repairs for a week. On 8 August she was back to the Kurils and Sea of Okhotsk. On the 17th she attacked two freighters, missed. On 4 October she was back to Pearl Harbor.

She performed next reconnaissance missions at Kwajalein and from 7 November to 19 December, and Ponape (17 January-6 March 1944). She was overhauled again at Mare Island and returned to Hokkaidō–Kuril Islands for her 11th patorl (8 August-17 September).

She patrolled Muroran, Matsuwa, and Paramushiro. On 24 August she attacked and sank Tosei Maru off Erimo Saki. On 5 September she attacked and missed another. On 8 September she met a 2-column, six-ship convoy and after 2045, she fired 4 torpedoes at overlapping targets and before midnight, again attacked the convoy, marked 2 hits on a freighter and retired briefly. On 0300 on 9 September she attacked the remainder of the convoy but fled by Daylight. At 20:26, she sank Shonan Maru, damaged 3-4 more before heading for for Midway on 17 September.

Her 12th was also her last patrol, from 10 October-29 November 1944 in the Kurils. Only two contacts. On 25 October she sank Hakuyo Maru (5,742 GRT) and later damaged another off Etorofu off Sakhalin and sailed back on 17 October, arrived in pearl on 29 November. Post refit she was versed as TS in Hawaii until June 1945, sent to New London as TS until the end of the war. She was inactivated by early November and in Boston, decommissioned on 15 November, went to the Reserve Fleet. On 19 June 1947 she became a Naval Reserve training ship, then by March 1949, transferred to Portsmouth until stricken on 1 May 1956. She won 10 battle stars for her service.

USS Skipjack SS-184

USS Skipjack SS-184

USS Skipjack was laid down on 22 July 1936 at EB, launched on 23 October 1937 and completed on 30 June 1938. After trials and shakedown in the Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, post-shakedown fixes in New London, she was assigned to SubRon 6 and made a cruise to the South Atlantic, back to New London on 10 April 1939 before being reassigned with USS Snapper and Salmon for the Pacific, ccrossing the Panama Canal on 25 May for San Diego on 2 June. In July she was in Pearl Harbor assigned to SubRon 2 and back to the West Coast for fleet tactics/training ops. until 1 April 1940, and back to Hawaii for more training until an overhaul at Mare Island and back to Pearl Harbor under SubDiv 15 (Captain Ralph Christie). In the summer 1941 she was refitted at Mare Island, back on 16 August for patrols off Midway, Wake and the Gilberts-Marshall area. In October 1941 SubDiv 15 (under “Sunshine” Murray) was transferred to ComSubAsiatic, tendered by USS Holland as SubRon 2. On 7 December USS Skipjack was in refit in the Philippines at Cavite NyD.

Under Cd. of Charles L. Freeman she started from there her first war patrol with remaining unfinished repair work completed en route east of Samar. On 25 December she spotted a military with a and aircraft carrier and destroyer, fired three torpedoes on sonar bearings from 100 feet (30 m) but missed. On 3 January 1942 she did the same on an enemy submarine, two hits, but no confirmation. She refueled at Balikpapan on 4 January 1942 and made it into Port Darwin for refit on the 14th.

Her 2nd patrol was in the Celebes Sea, uneventful except missing a Japanese aircraft carrier. She was in Fremantle for 10 March 1942. On 14 April she started her 3rd under James W. Coe in the Celebes, Sulu and South China Seas. On 6 May she spotted a cargo ship, placed the boat and fired a “down the throat” spread of three torpedoes sinking Kanan Maru. On a 17th, new attack on a 3-ship convoy, two torpedoes fired, badly damaged Taiyu Maru and later sunk Bujun Maru. Later on 17 May, she sank the Tazan Maru off Indochina. There was already some doubts about the Mark 14 torpedo when she took part in her own performance tests, inconclusive.

Her 4th patrol started on 18 July 1942 on the NW coast of Timor, mostly for recon, but severely damaged an enemy oiler. Back on 4 September.

Her 5th patrol brought her off Timor, Amboina, and Halmahera. On 14 October south of the Palau she sank the 6,781-ton Shunko Maru but was depht charged for hours by a Japanese destroyer and had to return to Pearl Harbor on 26 November for repairs and refit.

Her next three patrols (6-8th) were unproductive. Her 9th was in the Caroline/Mariana Islands areas, sinking two ships. On 26 January 1944 she was about to fire on a merchant by night but shifted target when a destroyer arrived. She fired her 4 forward torpedoes and sank IJN Suzukaze, manoeuvered and gutted the cargo with her stern tubes, however one of her torpedo tube valves stuck open she the roop was quickly flooded. The torpedomen could close emergency valves but she took on 14 tons of water and went to a steep angle, blew ballasts and surfaced. Skipjack resumed the attack and found, sunk the converted seaplane tender Okitsu Maru and returned to Pearl Harbor on 7 March.

Sje took part in Mark 14 performance tests in cold water off the Pribilof Islands until 17 April and sailed to Mare Island for a comprehensive overhaul modernization and back to Pearl Harbor for her 10th and final war patrol in the Kuril Islands, damaging an enemy auxiliary, missed a Japanese destroyer.

On 11 December 1944, she was back to Midway and Ulithi, then Pearl Harbor for refit and on 1 June 1945 departed for New London and the training submarine school until sunk as a target vessel at Baker test, Bikini Atoll, July 1946. She was refloated, towed to Mare Island and sunk again on 11 August 1948 off California by aircraft rockets, stricken on 13 September 1948. She won 7 battle stars.

USS Snapper SS-185

USS Snapper SS-185

USS Snapper was the first ordered and laid down at the government’s owned Portsmouth Navy Yard on 23 July 1936, launched on 24 August 1937 and commissioned on 15 December 1937. On 10 May 1938 she left Portsmouth, New Hampshire for her shakedown cruise to Cuba, Panama, Peru, Chile and back on 16 July with final acceptance trials and post-shakedown fixes. On 3 October she joined SubRon 3 based in Balboa, Canal, in exercises until 15 March 1939, refitted at Portsmouth, left on 9 May via New London for the West Coast, San Diego on 2 June. On 1 July she sailed for Pearl Harbor and returned for an overhaul at the Mare Island until 1 March 1940.

Next she joined SubRon 6 in Hawaii on 9 April and stayed until the war started except for a refit at San Diego in October-November 1940 and at Mare Island, versed in SubRon 2 (San Diego) but like the others, she was in the Philippines in december.

On 19 December she started her 1st patrol from Manila for Hong Kong and the Hainan Strait until 8 January 1942, then Davao Gulf and attacked a Japanese supply ship, but escaped her escorting destroyer. Off Cape San Agustin on 24 January she had another missed attacked, forced to dive. On 1 February off the Bangka Strait, she spotted by a destroyer, depth chargeed, but she manoeuvered and sent two torpedoes which failed to hit. She retired in Soerabaja on 10 February then Fremantle.

For her 2nd patrol she departed on 6 March for Tarakan , then Davao Gulf and on 31 March, met a large armed tender/auxiliary cruiser, fired two bow torpedoes from 600 yards (550 m) and emerged at periscope depth to observe, then fired one from her stern tube, but had to dive to evade the escort. Later she proceeded under orders to Mactan Island to unload ammunition, taking 46 tons of food for Corregidor, making it on 4 April, and sailed back with 27 evacuees to Fremantle.

On 23 April underway she rescued USS Searaven, sailed for Albany (Australia) and then to Fremantle.

Her 3rd war patrol was in the Flores Sea, Makassar Strait, western Celebes Sea but found no targets, back on 16 July 1942.

On 8 August 1942 she proceeded for the South China Sea and on 19 August, fired two torpedoes at a cargo, lost contact, evaded escorts. She was too far for an attack on another. On 28 September she was mistook by a PBY-5 Catalina from VP-101 and deph charged in the Indian Ocean, 330 nm SE of Bali. She crash-dived and shook at 140 feet (43 m), only light damage.

Her 5th and 6th patrols were unproductive, but in the 7th she sailed to Guam, her sank her first in Apra Harbor on 27 August while heading north of the harbor, firing three at the first target, one at the second and departed. Observed one hit on the first, Tokai Maru.

On 2 September she spotted a convoy of 5 cargos, 2 escorts. She fired a “down-the-throat” spray at the escort IJN Mutsure, blew her bow (she sank) and evaded a depth charge attack. On 6 September she intercepted another convoy, fired three torpedoes, missed. Sehe was back to Pearl on 17 September.

Her 8th patrol was off Honshū (19 October to 14 December) in heavy seas unil slighting a convoy of 5 merchants, 2 escorts, closed the range, fired three bow torpedoes, scored two hits, blew Kenryu Maru.

On 14 March 1944 after her overhaul at Pearl she started her 9th patrol in the Bonin Islands. Few targets spotted but on 24 March, convoy of 12, fired eight torpedoes, six hits, credited damaging a freighter. Back to Midway on 29 April.

10th war patrol: Tasked of lifeguard duties near Truk during USAAF raids. Rescued none. On 9 June, she was attacked bby air, made a crash dive, one bomb dropped, above the hatch, killing one, injuring 6 including the CO. She was also strafed while diving. After she resurfaced, found her pressure hull undamaged, but outr hull crippled and severe oil leak, tank punctured, patched. She transferred 2 sailors to the tender Bushnell at Majuro on 13 June, and was back at Pearl Harbor on 21 July.

On 5 September she started her 11th and final patrol in the Bonin Islands. On 1 October she met several vessels escorted by small patrol craft, fired all her bow torpedoes (“down-the-throat”), hits scored on two. She sank the liner Seian Maru and coastal minelayer Ajiro. Ordered next as lifeguard station off Iwo Jima until 18 October, headed back to Midway on 27 October, and Pearl Harbor.

She left on 2 November for overhaul at Mare Island, until 9 March 1945, San Diego on 11 March for training, crossed Panama on 20 May 1945 for New London, and operated as TS until decommissioned at Boston on 15 November 1945. Stricken 30 April 1948, sold 18 May 1948. 6 battle stars.

USS Stingray SS-186

USS Stingray SS-186

USS Stingray was the second laid down at Portmouth on 1 October 1936, launched on 6 October 1937 and completed on 15 March 1938. After shakedown off New England and Caribbean she had fixes in Portsmouth until 14 January 1939, returned to the Caribbean and New London, crossed the Panama Canal to San Diego (11 May) for intensive training in SubRon 6. Departed on 1 April 1940 for Hawaii, then overhauled at Mare Island, back to Hawaii and then Cavite on 23 October 1941.

On 7 December she was preparing for a patrol at Manila. She sailed in Lingayen Gulf, seeing the Japanese invasion but had tech issues and could not attack, went back on 24 December. She started her 2nd patrol on 30 December. In Sama Bay on 10 January 1942 she sank the transport Harbin Maru. She patrolled Davao Gulf through and entered Surabaja on 12 February, then headed for Fremantle, arrived on 3 March.

She started her 3rd patrol on 16 March to the Celebes Sea and Java Sea, sighting, attacked but missed a Japanese destroyer off Makassar City, back on 2 May.

Her 4th patrol started on 27 May and she headed for Davao Gulf and Guam. On 28 June, sighted two cargos with escort, closed and fired four torpedoes at the first, sank the converted gunboat Saikyo Maru. Next she patrolled off Guam until 15 July, and back to Pearl for overhaul, fitted with two external torpedo tubes, below the deck level forward (making dfor 6 TTs bow).

5th war patrol was in the Solomon Islands, 6th in the Marshall Islands, no kills. In the 7th, she sank the Tamon Maru.

8th patrol started from Pearl on 12 June 1943 in the Carolines. Spotted a high-speed northbound convoy but too fast for her. She went back to Brisbane on 31 July.

On 23 August 1943 she started her 9th war patrol en route to Pearl Harbor and on 31 August a single B-24 Liberator mistook and bombed her. She made a crash dive and escaped the bomber as she crash-dived in the Solomon Sea west of Buka Island but was violently shook by three 500-pound (227 kg) bombs. They missed her by just 50 feet (15 m), causing significant damage. She had to make later emergency repairs while surfaced, then patrolled in the Admiralty Islands, ending in Pearl on 10 October 1943 and Mare Island for overhaul and repairs.

Back to Pearl Harbor she started her 10th patrol on 10 March 1944 in the Mariana Islands. On 30 March she closed in and passed three escorts to spread on two cargo ships, four torpedoes at the lead, one hit amidships, then four more at the damaged Ikushima Maru, which sank.

On 8 April, while north of the Marianas she hit a submerged object under 52 feet (16 m), lifting her for four feet (0.91 or 1.22 m), somthign off the charts which showed 2,000 fathoms (12,000 ft; 3,700 m) under her. The mistery remained unresolved.

On 13 April her lookouts sighted a broaching torpedo, and she dodged it to port, it passed 100 feet (30 m) ahead. Two seconds later another even narrorwly missed starboard and she searched for her attacker, found none. She sailed back to Pearl Harbor on 22 April.

Her 11th war patrol was on dull lifeguard station during the strikes on Guam. On 11 June she made a rescued and next day two more. On 13 June she closed to rescue an airman 500 yards (460 m) offshore, but she was shelled at and submerged to approach. She made four submerged approaches until the pilot could grab her persicopes, so she could steer away and later surface. On 18 June she had a fire in her superstructure, near the CT hatch, extinguished but restarted several times. The source was located and treated and she went on patrolling to Majuro Atoll and the Marshall Islands on 10 July.

After maintenance and R&R at Majuro she started for her 12th war patrol, for spec ops, carrying 15 Filipino officers and men, 6 tons of supplies to land them on the northeastern coast of Luzon. Underway bacl to Port Darwin on 18 August she picked up four Japanese sailors from the sunken IJN Natori, and arrived on 7 September 1944.

Her 13th patrol started on 10 September 1944 again, special mission for intel on landing beaches at Marjoe Island and back on 19 September 1944.

She made then two more missions (14-15th patrols) in the Philippines. Se was surfaced in the Pacific, some 100 nm east-northeast of Morotai on 3 October 1944 when mistook and attacked by a TBF Avenger from USS Midway (CVE-63). Crash-dived to 120 feet (37 m), and felt a detonation, then went down to 150 feet (46 m). The thud she heard before was probably the TBF and its rookie pilot crashing as being too low.

On 11 January 1945 she started her 16th and last patrol. She made Four special missions in the Celebes with Landing parties on Nipanipa Peninsula, Kagean Island, Pare Pare Bay and at Nipanipa Peninsula. She was back at Fremantle on 23 February and proceeded to New London via Panama on 29 April. She became a TS sub until decommissioned at Philadelphia on 17 October 1945, stricken 3 July 1947, sold 1948. Her GM 248 V16 diesels ended on the preserved USS Cod in Cleveland, held in reserve for parts. She earned 12 battle stars, but had the record for the most war patrols.

USS Sturgeon SS-187

USS Sturgeon SS-187

USS Sturgeon was the only one ordered to Mare Island Navy Yard to keep the yard in the loop of the latest sub designs, based on Portmouth plans, laid down on 27 October 1936, launched on 15 March 1938 and completed on 25 June 1938. She had trials in Monterey Bay, shakedown cruise on 15 October 1938, sailing to Mexico, Honduras, Panama, Peru, Ecuador, and Costa Rica, then back to San Diego on 12 December for fixes, then assigned to SubRon 6, West Coast. She made two cruises to Hawaii (1 July-16 August 1939, 1 April-12 July 1940). She left San Diego on 5 November 1940 for Pearl, until November 1941.

She left on 10 November for the Philippine and Manila Bay, on the 22th, SubRon 2, SubDiv 22, Asiatic Fleet. On 7 Dec. she was at the Mariveles Naval Section Base and sailed this afternoon to the Pescadores Islands and Formosa (Taiwan). Sighted but was too far from a small tanker.

Next she spotted a convoy of 5 merchants, a cruiser and 4 destroyers on 18 December. Emerged to periscope depth to score on the cruiser, but was sighted 250 yards (230 m) away and made a dive to 65 feet (20 m) when the first depth charge fell. No serious damage. She evaded.

On 21 December, she spotted in the night what was possibly a large cargo, made a stern torpedo spread, passed ahead due to an error. She went back to Mariveles Bay on 25 December.

Her 2nd patrol started on 28 December 1941 in the Tarakan area and Borneo. Sighted a tanker SW of Sibutu Island, 17 January 1942, missed. On the night of 22 January, contacted by USS Pickerel that a large convoy was headed her way, in Makassar Strait. Picked them by sonar dead astern, submerged and fired four, heard two explosions but had to pay 2.5 hours of DC attacks, no damage.

On 26 January, spotted a transport and 4 destroyers off Balikpapan. Fired a bow spread, head large explosion on the transport, believed damaged. 3 days later, she sank a tanker. On 8 February, she tracked an invasion fleet to Makassar. Escaped destroyers and a cruiser, reported the convoy. She was ordered to Java, Soerabaja on 13 February, then Tjilatjap. She embarked the Asiatic Fleet Submarine Force Staff and headed with Stingray sailed for Fremantle and on 20 February escorted Holland and Black Hawk.

Her 3rd patrol was between March and May 1942 off Makassar. On 30 March she sank Choko Maru. On 3 April she hit a 750-ton escort under the bridge, probably sunk. Fred three at a merchantman, missed. One torpedo remained stuck in the tube. Fired her bow tubes, probable heavy daage or write-off as she sailed while listing to beach on Celebes shore.

On 6 April she fired a spread at a tanker but these Mark 14 failed to arm and she was mercilessly depth charged but escaped and sailed off Cape Mandar, West Sulawesi (Makassar Strait). On 22 April she was caught by night surfaced by a destroyer’s searchlight, and made a crash dive, then 2-hour depth charging. On 28 April she sailed for Australia but left in the night of 30 April to rescue RAAF personnel reported stranded on an island next to Japanese occupied Cilacap Harbor, and the landing part was directed by Lieutenant Chester W. Nimitz, Jr. son of the admiral. They found none and returned to base.

The 4th patrol was in June–July 1942 after refit, sailing west of Manila. On 25 June she spotted a 9-ship convoy, fired three at the largest, noted hits but was hammered by escorts, escape with some gauges broken. On 1 July she sank the 7,267-ton POW (unmarked) Montevideo Maru off Luzon, 1,000 Australian POW and civilian internees from Rabaul, 18 (mostly Japanese -crew 88-, inc. the captain) survived, only to be later killed by local guerillas. The Japanese war crime here was to usually leave their POW transports unmarked, and leave the exit hatches closed when sinking. Many “hell boats” this went to the bottom with their desperate human cargo, in the hands of unaware US subs captains or pilots which would never have fired on an hospital ship. Geneva convention would have obliged them to at least paint a cross or symbol for recoignition, which they never did. On 5 July she badly damaged a tanker northbound from Manila. She was back at Fremantle on 22 July and had a short refit.

The Montevideo Maru became the worst maritime disaster in Australian history, but eyewitness surviving Japanese sailor later in life described the “death cries” of trapped Australians going down. They were indeed jam-packed without food, sanitation or water inside the cargo holds, under a blistering heat. Meny already died during transport.

USS Sturgeon started her 5th patrol between September and October 1942 as the Philippines campaign developed. She left on 4 September to sail between Mono Island and the Shortland Islands (Solomons). On 11 September she was west of Bougainville, preying on shipping between Rabaul, Buka, and Faisi. She spotted and fired four torpedoes at a large cargo but missed (likely still Mk.14 malfunctions at this point). Three days later she fired four on a tanker with two apparent hits (no kill, tankers had an amazing buoyancy and could survive up to six torpedo hits). At 05:36 on 1 October she spotted the 8,033-ton aircraft ferry Katsuragi Maru. Four torpedoes launched, three hits sank her. She was hammered by escorts but managed to broke off and rescue survivors. Next she patrolled off Tetepare Island until back to Brisbane on 25 October for refit.

Her 6th patrol was between November 1942 and January 1943, patrolling in the Truk area on 30 November, fired four at a vessel, one hit, no kill on 6 December. She damaged other cargos on 9 and 18 December. She sailed for Pearl Harbor on 25 December, arrived on 4 January 1943 for a major overhaul from 14 January to 11 May 1943.

She departed for her 7th patrol on 12 June and entered Midway Island to be closer to Japan, on 2 August. She spotted 7 worthwhile targets but attacked only one, on 1 July, a spread at a freighter, two hits, heavy damage. Her 8th patrol was from Midway again, from 29 August to 23 October, but she had no kill and sailed back to Pearl Harbor.

Her 9thh patrol started on 13 December 1943 in Japanese home waters. She sighted a 7-ship convoy on 11 January 1944, fired four on overlapping targets, sank the Erie Maru. She escapedd a long and heavy depth charge attack and managed later to regain contact with the convoy and after 5 days or pursuit she attacked Akagi Maru and the destroyer Suzutsuki, in Bungo Channel. Suzutsuki was hit by two, blowing off both bow and stern, so she sank very quickly with all hands. But she was happered for hours by Hatsuzuki and managed to escape at 18:55. On 24 January she made two attacks with her last torpedoes, making one hit on an unidentified merchant and spread which claimed the Chosen Maru. On the 26th she attacked bu missed two freighters with her last “fishes” and sailed back to Pearl Harbor via Midway for a long refit.

The tail of Sturgeon after her 1943 refit.

Her 10h patrol was in the Bonin Islands area from 8 April to 26 May with orders as plane guard near Marcus Island in air strikes. On 10 May, she attacked a convoy of 5 merchant ships, 2 escorts. Two hits on a small freighter bu she was spotted and attacked by IJN aviation. Back to periscope depth she trailed the convoy until the next morning, fired four torpedoes at a freighter and sank with 3 Seiru Maru. She swung around, fired her bow tubes, two hits recorded, target dead in the water, status unknown. She escaped escorts and was on plane guard duty on 20 May, rescuing three airmen, then sailed to Midway on the 23.

Her 11h patrol was between June and August 1944 to Nansei Shoto on 10 June, two contacts but heavily escorted, first a 8-ship convoy, attacked on 29 June. 4 torpedoes fired, all hit the 7,089-ton passenger-cargo troopship Toyama Maru. This had a direct influence on the battle of Okinawa, as she brough a reinforcement of 5,600 troops of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade.

On 3 July USS Sturgeon spotted another 9-ship convoy with air cover and many small escorts. Three hit, sank Tairin Maru. The crew counted in the next two hours some 196 depth charges and aerial bombs but she evaded escorts, returned to Pearl Harbor on 5 August. This was her last patrol.

It was decided she was now old and battered enough to merit a reprive. She was ordered to California for an overhaul in San Francisco from 15 August and on 31 December 1944, she sailed to San Diego then on 5 January 1945 East Coast via manapa, New London on 26 January. She was allocated to SubRon 1 and Block Island Sound as training sub until 25 October. Next she was sent in Boston Navy Yard on 30 October to be decommissioned on 15 November 1945, stricken on 30 April 1948, sold for BU on 12 June 1948. She earned 10 battle stars for her service. She did not survived the blowtorch, but her name was given to the first US Navy SSN as a tribute to a very successful submarine.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign