Italian Regia Marina, 1863-1907

Italian Regia Marina, 1863-1907

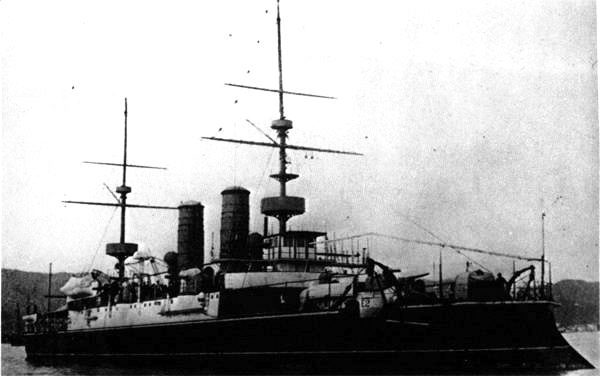

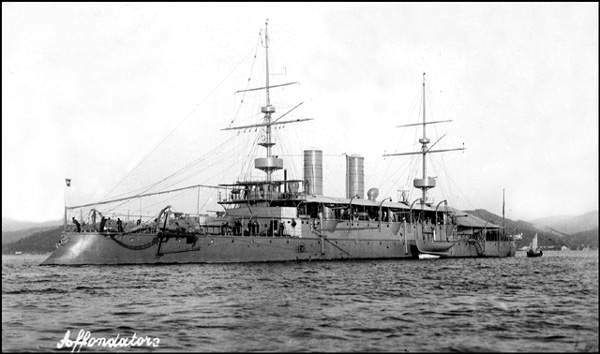

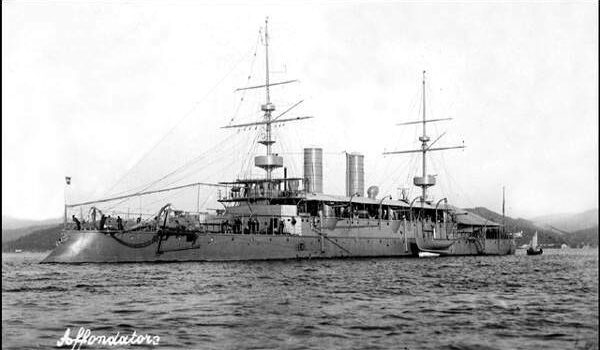

Affondatore was an armoured ram of the Regia Marina built by Harrison, Millwall in London from 1863 and while incomplete, was bought and sent to join the newly created Italian Navy as the Third Italian War of Independence started. Named Affondatore (“Sinker”) she was admiral Persano’s “secret weapon” against the Austro-Hungarian, heavily protected, steam only and fast, initially designed to use her ram backed by two massive 300-pounder guns in turrets. She arrived off Lissa just as the battle started in July 1866. She became flagship, after Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano was transferred, but the move cost him dearly. Affondatore was found in a general melee, was hit many times but hold her ground. She sank in a storm in August but was refloated and rebuilt between 1867 and 1873. She became a guard ship in Venice from 1904 to 1907, completely redesigned again and ended as a depot ship in Taranto, as the oldest veteran of the battle of Lissa anywhere.

The Austro-Italian ironclad arms race

⚙ The Austro-Italian naval Arms Race prior to Lissa (1864) | |

Regia Marina Regia Marina |  KuK Kriegsmarine KuK Kriegsmarine |

|

Formidabile class 1860 Principe di Carignano class 1861 Re d'Italia class 1861 Regina Maria Pia class (1862) Roma class (1863) Affondatore (1863) Principe Amedeo class (ordered 1865) |

Drache class (1860) Kaiser Max class (1861) Erzherzog Ferdinand Max class (1863) |

Development: A troubled start

On 11 October 1862, the Italian Navy staff placed an order with Millwall seaside shipyard of London, for an armoured steam ram. The design was prepared by naval officer Simone Antonio Saint-Bon, famous engineer and later admiral of the Royal Navy. However, financial problems had it took over by Harrison, the former chief engineer (see later). Di Saint-Bon wanted her at first to be unarmed, a pure ram to sink Austrian ironclads, but the chief engineer at Harrison pushed forward a proposal to have her including two large-caliber guns in turrets as a complement. She ended thus, less radical as she could have been and more balanced. And she had somewhat troubled construction with a delivery expected within the following nine months of being laid down on paper.

But shortly after the order was placed the original shipyard went bankrupt so Mr. Harrison which designed her, took over the shipyard, but was only able to lay down her keel by April 1863, extending her expected construction time up to launch to a year and a half. Despite the contract included a clause with a penalty of 50 pounds for each day of delay in delivery from 1 October 1864, in the context of a probable Italian-Austrian war, strong pressure from the Italian went against scores of issues with the yard:

Problems related to the reorganization of the shipyard after its bankruptcy, re-engaging former skills workers, gathering all the material already sized to pay the debts, etc. The penalty accumulated in the end amounted to 5,000 pounds. However Italy now feared the ship will be blocked by the British Government following its usual neutrality policy. Di St Bon agreed to move the delivery date to 6 June 1866 and renounced the penalty providing the yard would keep the delay. The Italian government even did not asked for extra penalties when the contracted speed was not met as well as issues of stability emerged after the first sea trials.

Design of the class

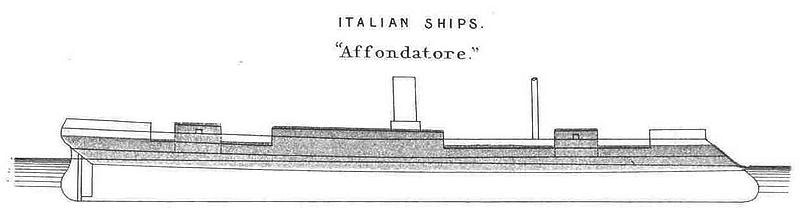

Compared to previous ships, Affondatore was quite revolutionary in her layout. The ram was of course her main asset, but the speed and stability needed to be on par. Outside this, Harrisson managed to convince the Italian admliralty to keep two gigantic (for the time) single Armstrong Mark cannons IV muzzle-loading 254/30 mm instead of a dozen smaller gins. And in addition they were to be installed in two revolving armored turret in the axis, one at the bow, one at the stern. To compare, the very first British turreted warship was HMS Monarch laid down in 1866. The elephant in the room and reference for all savvy naval engineers in Europe at the time was of course the example of USS Monitor built in 1862 and the scores of monitors built afterwards until 1865 some with turrets fore and aft, and one being seaworthy.

This arrangement was eventually adopted by the Italians, and perfected ten years later with the Italian-built Duilio class ironclads. Affondatore, despite is disappointing performances was considered a first prototype of modern battleships.

Beyond her innovative features, was experimental and thus presented a number of defects, which became evident during her first trip to Italy in the summer of 1866.

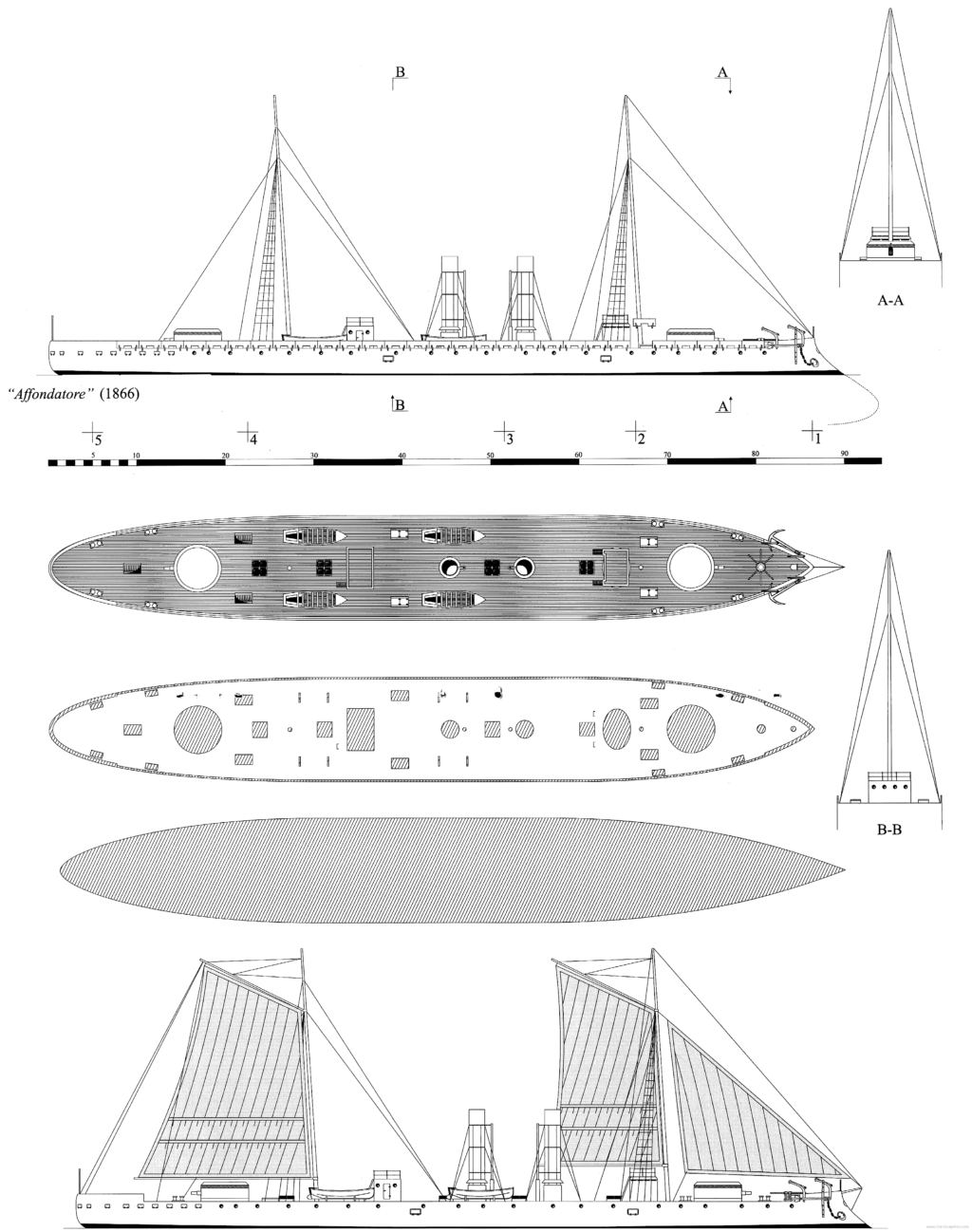

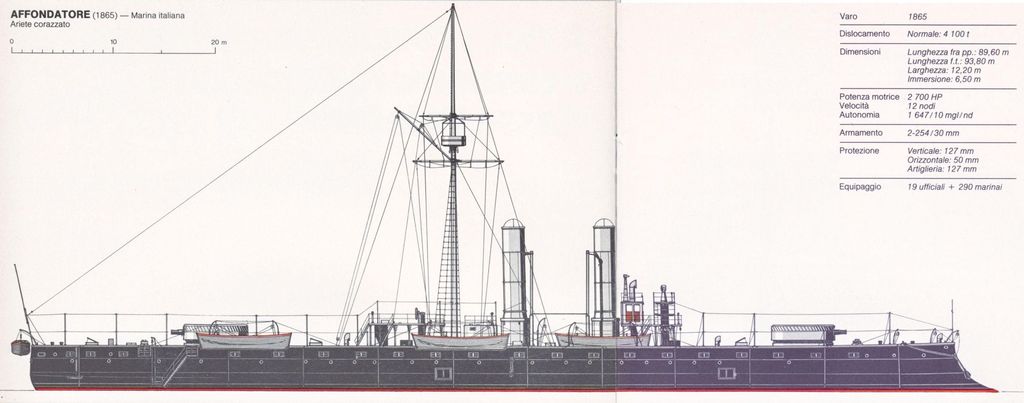

Hull and general design

Affondatore was quite large, at 89.56 metres (293 ft 10 in) between perpendiculars, 93.8 m (307 ft 9 in) overall, on a rather narrow 12.20 m (40 ft) beam t keep a good ratio, a draught of 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in). She displaced 4,006 long tons (4,070 t) normal load, up to 4,307 long tons (4,376 t) full load. She had a very minimal superstructure and just a small conning tower aside her two raked pole masts for stud sails, two turrets, and a small cabin aft plus accesses hatches to the interior. Officers as usual had their housing aft. She had a crew of 309 officers and enlisted men at the start as completed but after refits and rearmament she ended with 356. The most sicking feature was of course her very long ram, protruding almost six meters after the end of her bow deck. Her stern was clipper-shaped.

Powerplant

Her steam engine comprised an horizontal reciprocating engine, with two cylinders and a return connecting rod. Steam came from eight rectangular, boxy boilers (which limited pressure due to the shape). These were trunked into two funnels placed amidships. The powerplant generated 2,717 indicated horsepower (2,026 kW). The initially designed top speed was 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Sufficient coal was carried for a 1,647 nautical miles (3,050 km; 1,895 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). In addition for long trips when the wind was cooperating, she had a two-masted schooner rig, but compared to true sailing ironclads of the time, this was not sufficient to keep her speed up. At least this rigging was very easy to manage for her crew with few hands and in no time, hemped by steam winches.

This top speed setup was reasonable, just 12 knots, but on trials she was completely unable to reach this figure, defeating the main purpose of having a ram in the first place.

Furthermore, her great length to beal ratio, also sound on paper for top speed, meant her agility was poor, which also was detrimental in a melee. Her turning rate was way too slow, she bled speed and needed a lot of space. Stability also was rather unsatisfactory, she rolled a lot due to her high center of gravity especially when unloaded from coal and ammunition. She rolled so badly in that case it was seen as a danger. Captains were used to always carried their full load and ensire to complete their cruises while keeping always coal aboard. The Regia Marina’s staff concluded she was not fleet-capable and rather better for isolated coastal use, as a guard ship, notably for the adriatic. A nother problem that was enlighted, was her armored command post and conning tower combined. It was large enough to have the whole command crew inside, circular and pirced with eight slits for a semi-panoramic view. But the view was in reality very partil and poor, and this impeded her command. This was painfully highlighted during the battle of Lissa.

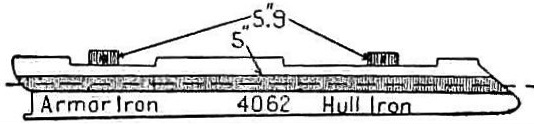

Protection

Affondatore had an all-iron hull, without any wood used in the structure, but precious essences in the officer’s quarters. The sides and turrets were both protected by 127 mm (5 in) wrought iron armour plates bolted together, and there was a 50-millimetre-thick (2 in) armoured deck. The conning tower was supposedly also made in 5-inches plates, but it’s speculative, no sources states its thickness. The armoured deck was of the turtleback style albeit the slope’s thickness is unknown. The belt was complete, tall and extending all the way to the stern and prow, connecting above to to the armour deck. Due to the distances of engagements and height of the belt this scheme was seen satisfactory in nearly all cases. Great confidence in the armour was put to defeat most ironclad calibers of the time, while on paper, Affondatore’s heavy guns were supposed to defeat the armour of any opponent. This was on paper only, though. It’s dubious penetration tests were made.

Armament

The primary armament was her ram: This was 2.5-metre-long (8.2 ft) from the tip of the bow deck to the waterline and went on underwater. it was only good as the ship’s top speed and agility, which were deficient. This made her new main gun armament comprising two 300-pounder Armstrong guns, both in single turrets, fore and aft. 300 dpr was a peculiary measure which did not helpe determine their exact caliber, either 220 mm (8.7 in) or 228 mm (9 in) depending on the authors, with a relative consensus on the latter. She also carried two 80 mm (3.1 in) guns usable in landing parties as they were on wheeled undercarriages. This of course, will change considerably over time.

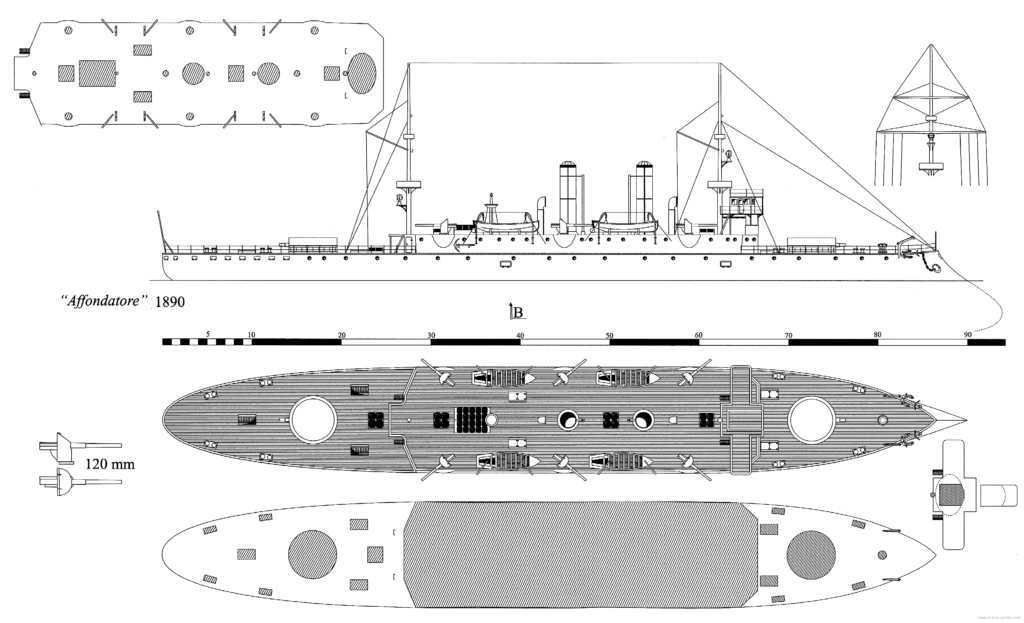

Refits and modernizations

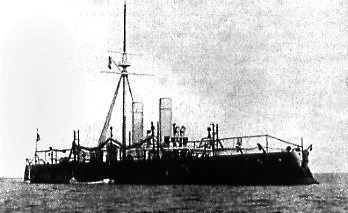

Affondatore in 1875

In her first refit of 1883-1885 she received a more modedrn VTE steam enegine and cylindrical boilers for a 3,240hp and a better sped. She also was fitted with a forward proper military mast, and it seems she received a true conning tower with 5-inches (127mm sides) all cast. Her two antiquated 229mm/14 guns were exchanged for two modern 254mm/30 B types from Vickers Arsmtrong (10 inches).

In her second refit of 1888-1889 she gained six 120mm/24 Armstrong 1.38ton BLR and a single 75mm/21 (3-inches) Uchatius 29cwt BL No1 as secondary gun as well as eight single 57mm/40 Hotchkiss guns (6 pdr) and four or five 37mm/20 Hotchkiss guns (3-pounder). During her last refit she was added in 1891 two 17 inches (450mm) torpedo tibes, both in the beam. Her appearanches changed a lot also, with the onstruction of a complete superstructure admiships, straight funnels and straight military masts with fighting tops in which were placed the 3-pdrs, two searchlight platforms, a new bridge build above the CT, spotting tops and her six 6-pdr placed on sponsons either side of her battery deck.

Affondatore in 1895

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 4,006t standard, 4,307t fully loaded |

| Dimensions | (89.6 pp) 93.8m oa x 12.2 x 6.35m () |

| Propulsion | 1 HSE, 8 rectangular boilers 2,717 hp |

| Speed | 12 kts |

| Range | 474t coal, 1647 nm/10 kts |

| Armament | 2x 229mm/14 (9 in) Armstrong 12.6ton MLR |

| Protection | Belt: 127mm (5-in), turrets: 127mm, deck: 51mm (2-in) |

| Crew | 309-356 |

Career of the Affondatore

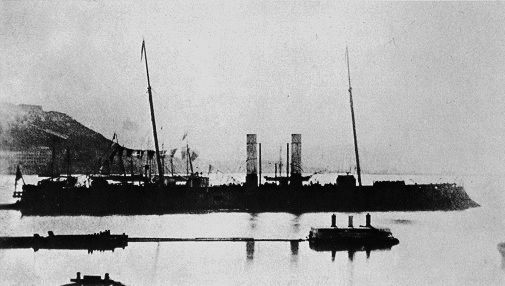

Affondatore in 1866

Affondatore was launched on 3 November 1865 but as Italy was near to declare war against Austria in June 1866, the government feared she would be immobilized under neutrality laws in Britain and thus ordered the crew to move her, still incomplete, to nearby Cherbourg in France for fitting out. The yard continued to shipped parts until this was over and she left Cherbourg on 20 June, the very day Italy declared war and started her long voyage to the Adriatic Sea.

The Third Italian War of Independence was the existential fight for Italy, and the overall Italian fleet commander, Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano, whkch also helped building the fleet, was very cautious and repeteadly avoided confrontation, arguing he wanted to wait until the arrival of Affondatore, in which he placed a lot of trust to turn the tables. It was despite the fact his fleet was already much larger than the Austrian one on paper. However arguably there wa spoor coordination between the ships coming from different kingdoms. Minimal training was made in order to avoid accident, preserve the machinery and stocks or coal and ammunition. But his inaction weakened morale while subordinates openly accusing him of cowardice. Meanwhile Affondator was signalled in Gibraltar on 28 June, entering the Mediterranean.

On 16 July, Persano was forced by the government to leave Ancona and seek action with the Austrians, choosing a bait, which was the island of Lissa (Vis), and started operations there on the 18th. Troop transports carrying some 3,000 soldiers and the first phase, for two days, was bombarding Austrian forts for the intended landing. Informed, Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff sailed out to meet him. On the 20th his fleet was spotted, and in between, Affondatore joined arrived off Lissa on 19 July with largely inexperienced crews, which failed to make any gunnery drill. Persano on the 20th made a third attempt to reduce the forts (after spending a large stock of ammunitions, which were lacking for the battle) when the dispatch boat Esploratore arrived reporting Tegetthoff’s approach. Persano had hios fleet on three locations. Her ordered his ships to form up with Vacca’s division, the closest, first in line abreast and then line ahead formation, leaving Affondatore initially located on the disengaged side.

Then came momentous personal decision, much criticized by most authors since. Persano decided, just as the action was about to start, to leave his flagship, Re d’Italia, an US-built coastal ironclad, to be transferred to Affondatore. This resuired lowring a steam sloop, sail to the distant Affondatore, and claimed aboard, which took tremendous time. Several reasons had been cited, one being that the ship was potentially the strongest asset in the fleet, so more suited as flagship, or just for personal safety. But what was crippling is the fact the transfer was not reported. All captains still looked at the Re d’Italia for flag signals that never came, whereas Tegetthroff was rshing forward, seizing the wek point in the Italian formation.

Persano wanted to steam up and down the Italian line, and found the ship painfully slow for the task, but he did so anyway, and issued various orders to individual ships which ignored his signals, still referring to Re D’Italia. The latter, stopped meanshile, had open the breech in the line Tegetthoff needed to break through. Initially failing to ram any Italian vessl until turing back and aiming at Persano’s formation, the latter keeping Affondatore out of the action, until Herzherzog Ferdinand Max rammed Re d’Italia, sinking her. Since everybody thought Persano was still onboard, moral plummitted in Italian ranks.

Seeing Re di Portogallo under heavy fire convinced Persano decided to commit Affondatore, and ordered the captain to aim a the Austrian Kaiser, a seemingly easy micking for his armoured ship, but he failed, only making a glancing blow.

Kaiser meanwhile rammed Re di Portogallo already on fire. Affondatore tried a second attempt to ram her and failed again, but still secired a single hit which badly damaging Kaiser (20 crew dead and wounded), considerable damage. The Austrian ironclads disengaged protect their wooden ships inside their triangle formation, and Persano still led Affondatore, believing his fleet would follow. Until he was signalled he was almost alone. Only one ironclad followed him. Then he broke off and returned to this ship for reporting. He was signalled how much the fleet was low on ammunition and coal. He then ordered a withdraw, soon followed by the Austrians until night fall. When she arrived in port, Affondator was hit by 22 Austrian shells which cause considerable damage.

It is frequently argued that this improperly repairs damage which caused her to sink in a storm in Ancona harbour, on 6 August 1866. Naval historians Greene and Massignani argued however this was the result of too much water ingested caused by her low freeboard, not detcted and comprimising her already weak stability. The French journal “La Revue Maritime et Coloniale” meanshile stated, based on Cherbourg reports of the general state of the ship in completion, the faulty installation of her hatches allowed water to enter her in bad weather.

Whatever the case, she was refloated by 5 November and rebuilt at La Spezia from 1867 to 1873 and again later in 1883–1885 (new boilers and engines) for 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph).

The first reconstruction was done in the Arsenal of La Spezia.

On 1 July 1877, she was reclassified as a 1st class armored ram. On 12 June 1881, together with the new battleship Duilio and the Principe Amedeo, she attended the launching ceremony of the cruiser Flavio Gioia in Castellammare di Stabia. In the last months of 1881 she was under the command of the captain Giuseppe Manfredi. She sailed with Castelfidardo and the scout Marcantonio Colonna, to Cairo where nationalistic unrest was underway, to protect nationals. The situation degenerated into xenophobic riots leading on 11 June 1882, to the killing of several Westerners, notably Italians in Alexandria. The white population then fled to the port and seek asylum on board Western warships moored in port, including Affondatore. In July, she was transferred to Port Said and gathered here the Italian consulate staff and many of the local Italian community, but also Austro-Hungarian, Russian and German refugees.

On 1 July 1877, she was reclassified as a 1st class armored ram. On 12 June 1881, together with the new battleship Duilio and the Principe Amedeo, she attended the launching ceremony of the cruiser Flavio Gioia in Castellammare di Stabia. In the last months of 1881 she was under the command of the captain Giuseppe Manfredi. She sailed with Castelfidardo and the scout Marcantonio Colonna, to Cairo where nationalistic unrest was underway, to protect nationals. The situation degenerated into xenophobic riots leading on 11 June 1882, to the killing of several Westerners, notably Italians in Alexandria. The white population then fled to the port and seek asylum on board Western warships moored in port, including Affondatore. In July, she was transferred to Port Said and gathered here the Italian consulate staff and many of the local Italian community, but also Austro-Hungarian, Russian and German refugees.

Her refit between 1883 and 1885 was the most radical: Her two former sail masts were eliminated, replaced by a single military mast abaft the smokestack, her machinery was replaced a new one as stated above, rated for 3,240 HP and she had a new command bridge installed while her armament was increased with six 120mm/40 mm Ansaldo guns, eight Hotchkiss 57 mm, and four 37 mm guns plus four torpedo tubes, so by 1885 tshe was reclassified as a 3rd class battleship.

She took part in the annual fleet maneuvers of 1885, and was assigned to the 2nd Division of the “Western Squadron”, later joined by the ironclad Roma and five torpedo boats. This ssquadron made a mock attack attacked of the “Eastern Squadron” in a possible Franco-Italian war, compounded with operations off Sardinia.

Affondatore took part in a naval review with the German Emperor Wilhelm II in attendance during his official visit to Italy in 1888. From 1888 to 1889, Affondatore was modernized with her main battery guns were replaced with two 254 mm (10 in) guns in new turrets. A new, larger superstructure was built to house a new secondary armament, and a second military mast was fitted. Her new secondary battery of six 4.7 in guns in single masked mounts, a single 75 mm (3 in) QF gun and eight 6-pdr or 57 mm (2.2 in) QF guns plus four 3-pdr or 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannons to deal with torpedo boats. In 1891, she was reclassified as torpedo training ship, fitted with two torpedo tubes.

In 1891, she became a training ship for torpedo pilots and in 1892 took part in the celebrations, in Genoa, of the fourth centenary of the discovery of America. She received further modernizations between 1894 and 1898.

She remained in the 3rd Division, Active Squadron and took part in the 1893 fleet maneuvers with the new iconclad Enrico Dandolo, torpedo cruiser Goito plus four torpedo boats. From 6 August to 5 September they similated a French attack on the Italian fleet. On 1st October she was stationed in Taranto with Ancona, the protected cruisers Liguria, Etruria, and Umbria, torpedo cruisers Monzambano, Montebello, and Confienza, and until 1894. In 1899, Affondatore she was reassigned to the 2nd Division alongside the ironclads Sicilia and Castelfidardo, torpedo cruisers Partenope and Urania.

In 1904, she was relegated as a harbour defence ship, sent to protect Venice, and be used as a guard ship until 1907. She was stricken on 11 October 1907, and used as a floating ammunition depot at Taranto. Sources diverged on her fate.

Between 1904 and 1907 she was stationed in La Spezia, and became the base’s main guard ship. it’s odd that apart her initial travel from britain into the Adriatic, she never ventured out of the Mediterranean. She was stricken on 11 October 1907, transferred to Taranto, used an ammunition depot before demolition which date is unknown, somewhere in 1914.

Read More/Src

Books

Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1886). “Evolutions of the Italian Navy, 1885”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1888). “Notes on Italian Navy, armoured ships—Italia and Lepanto—Sicilia, Re Umberto, and Sardegna—Andrea Doria class”. Naval Annual. Portsmouth

Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1889). “Foreign Naval Manoevres”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1899). “Comparative Strength”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Clarke, George S. & Thursfield, James R. (1897). The Navy and the Nation. London: John Murray.

Dupont, Paul, ed. (1872). “Notes sur La Marine Et Les Ports Militaires de L’Italie” The Naval and Colonial Review.

Fraccaroli, Aldo (1979). “Italy”. In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 334–359. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

Garbett, H., ed. (1894). “Naval and Military Notes”. Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XXXVIII. J. J. Keliher: 193–206.

Greene, Jack; Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Da Capo Press.

“La Battaglia di Lissa (20 luglio 1866)” [The Battle of Lissa (20 July 1866)] (in Italian). Marina Militare. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

“Miscellaneous”. Birmingham Daily Post. No. 2582. Birmingham. 5 November 1866.

Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio & Sullivan, David M. (December 2014). “Capital Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918: Part I: The Formidabile, Principe di Carignano, Re d’Italia, Regina Maria Pia, Affondatore, Roma and Principe Amedeo Classes”. Warship International. Vol. 51, no. 4. pp. 323–360. ISSN 0043-0374.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

“The Battle of Lissa” (PDF). The Engineer. Vol. 22. 30 November 1866. pp. 417–418. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2015.

Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.

Links

militaryfactory.com

marina.difesa.it/

history.navy.mil

it.wikipedia.org/

worldnavalships.com

Model Kits

Armo 1:700, 1890s appearance

modellismopiu.it/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign