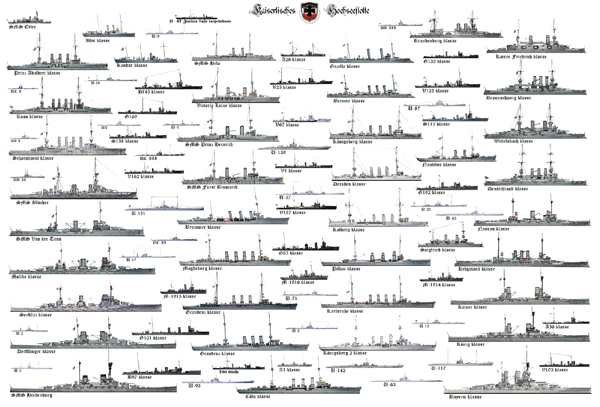

Germany’s first dreadnoughts

The four Nassau (Nassau, Westfalen, Rheinland, Posen) were the first monocaliber battleships of the German Navy. They were not however ordered or designed in response to the HMS Dreadnought as often assumed but predated her in the Admiralstab. Another confirmation the monocaliber type was “in the air” since at least 1903 and Cuniberti’s famous Jane’s publication. The Nassau class were the first of about twenty German dreadnoughts which quickstarted a famous prewar rivalry and naval arms race between Wilhelm II and Georges V, Fisher and Tirpitz.

Note: Updated 28/02/2022

The Kaiser’s “cruiser killer”

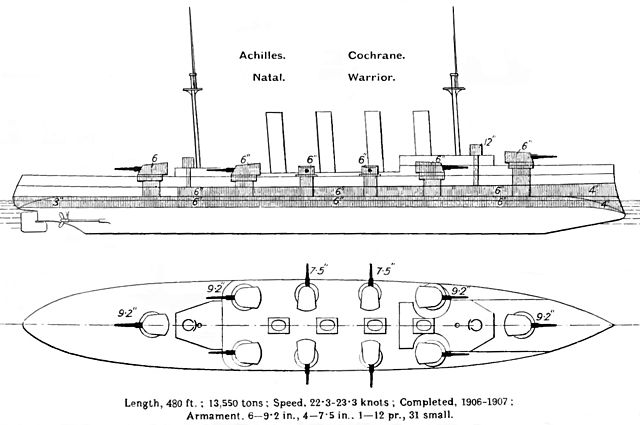

Warrior class diagram

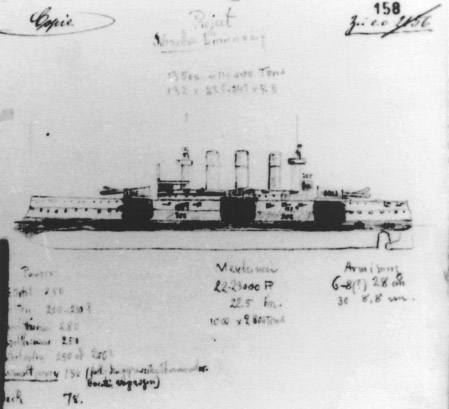

Indeed, design work on what would eventually become the Nassau class started in 1903. Long-term design phase was scheduled to start in 1906. Kaiser Wilhelm II was instrumental in this, arguing his navy was to possess large armored cruisers instead of traditional, slow capital ships. In December 1903, Wilhelm II suggested himself a 13,300 metric tons displacement design, armed with four 28 cm (11 in) guns, and eight 21 cm (8.3 in), a type of late armoured cruiser type in the fashion or late pre-dreadnoughts, with a powerful secondary armament. This was not far from Cuniberti’s own armoured cruiser, with the difference the latter had only 8-in guns all around. The cruiser advocated by the Kaiser was more in line with the British Warrior class laid down in 1903, which had a pair of 23,4 cm (9.2 in) completed by four 19,1 cm (7.5 in).

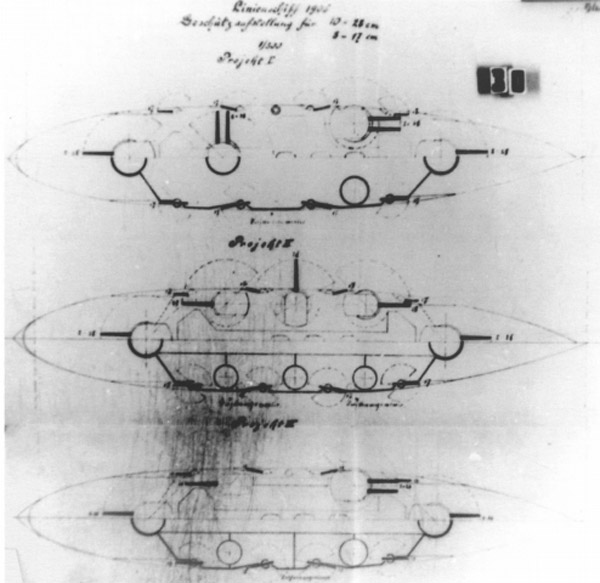

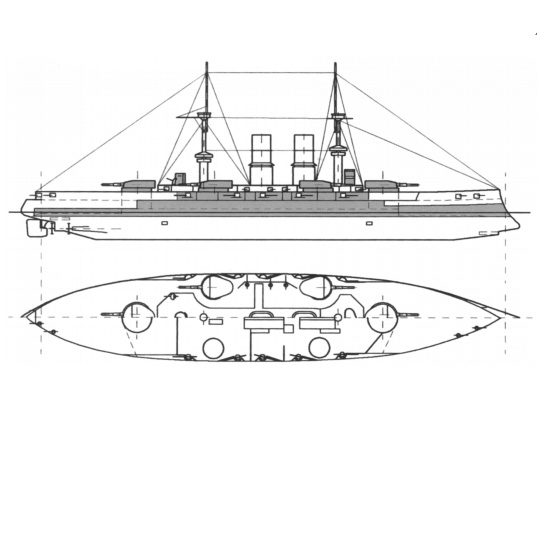

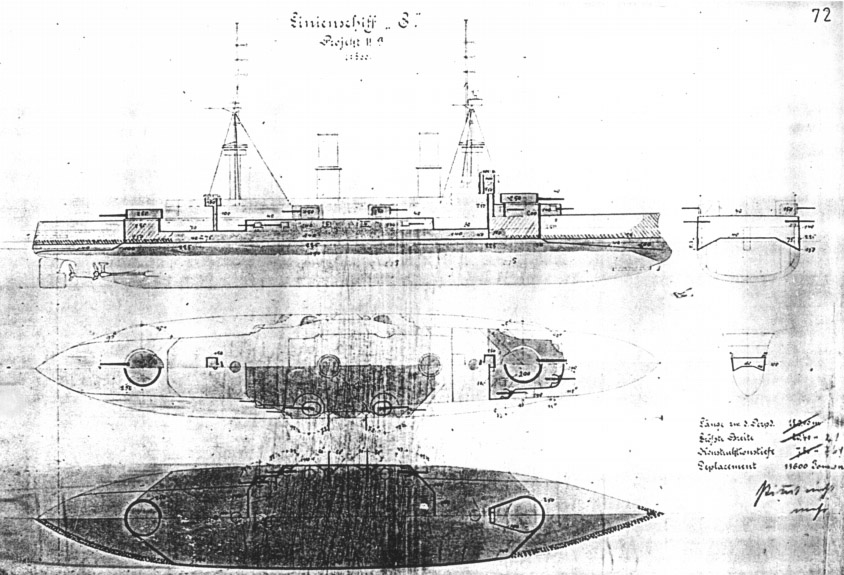

Emperor’s personal sketch submitted in December 1903

Top speed however was not the greatest concern, cruiser-wise, defined to be 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) (The Warrior class made 23 knots). The reasoning was that a longer-range caliber could ideally slow down the chased vessel, allowing to close for the finish. Wilhelm requested the Construction Office to submit him proposals and the latter complied, by January 1904. They presented three designs: “5A”, “5B”, and “6”.

The first two designed had in common eight 21 cm guns in four single-gun turrets plus four in casemates (“5A”) or in twin-gun turrets (“5B”). This too, was pretty close to Cuniberti’s design. The “6” design had ten guns in four casemates and six in a central battery, a more conservative approach. The naval command, participating in discussion settled on “5B” as possessing the best firing arcs. The “6” was sidelined until further evaluation, but it was eventually concluded it offered significant improvement over the Deutschland-class battleships (laid down 1903), which had single turrets already (and barbettes) with 17 cm guns.

Review of a mixed design (1904)

Eventually, as it seems the Kaiser’s design was to be placed in “reserve”, the latter intervened again, in February 1904. He wanted a 14,000 t (13,779 long tons) armoured cruiser, but with a secondary battery with ten 21 or even or 24 cm (9.4 in) guns. There again, the Construction Department and Kaiserliche Werft, Kiel submitted their own proposals (lost and thus, details unknown). “6B-D” was basically a variant of “6”, while “10A” and “10B” had the combination of 28 and 24 cm guns.

Kaiser Wilhelm interrupter the research work based on this design design, requesting a higher speed at a cost of a main battery made entirely of 24 cm guns. This resulted in further studies and delays resulted ending in April 1904. However the results were judged unacceptable, requiring more design work in the Reichsmarineamt (Imperial Naval Office), trying to obtain realistic figures. Officers, which for some participated to the debates, suggested that the secondary battery was to be limited to 21 cm (not 24 cm) guns, to spare weight and have more of them, and also on consifderations about fire corrections with very similar water plumes.

The sum of all these observations resulted in “Project I”, with an uniform battery of twelve 21 cm guns, and “Project II”, with sixteen, and “Project III”, with eight 24 cm guns but all with a 28 cm main battery. Deliberations went on until late April and “Project I” came as a winner since on cost concerns and avoiding to modify the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. The approved design led to refined variants, “IA” and “IB”, with casemates and single turrets respectively.

The Kaiser reviewed these and eventually approved “IA” in May 1904, but the secondary guns arrangement remained a point of contention for the following months. It’s only in December 1904 that the “7D” variant, with eight secondary guns in twin turrets was eventually adopted. From there, work went on an improved underwater protection system, which the Emperor approved on 7 January 1905. However everything was halted as German spies reported the contruction of the lord Nelson class, pre-dreadnoughts with a secondary battery of ten 9.2 in (230 mm) guns, plus estimates on the next class believed to be even much heavily armed. “7D” was sidelined as no longer sufficient to answer the pre-dreadnoughts. It was necessary to start over again.

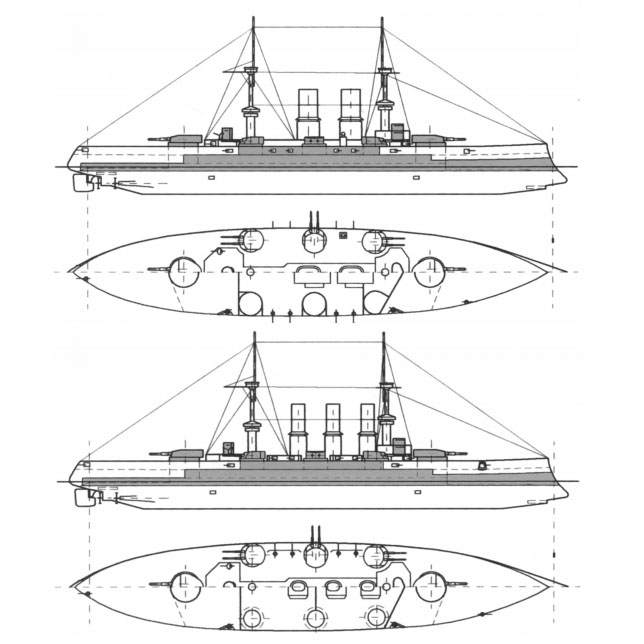

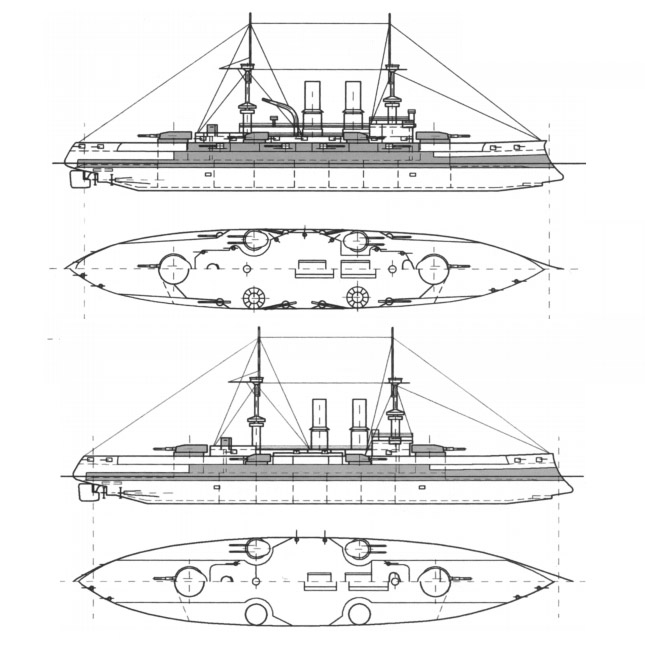

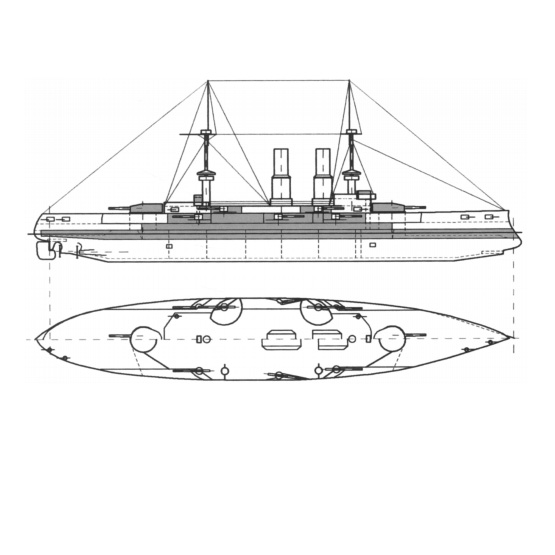

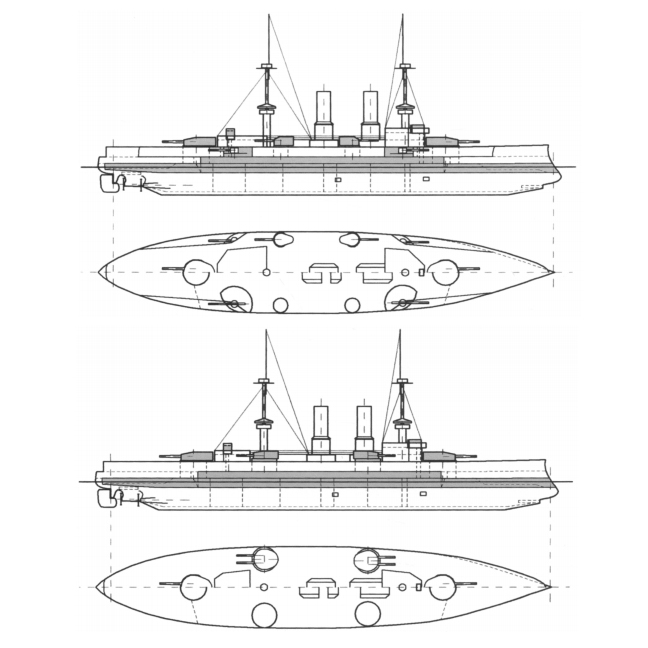

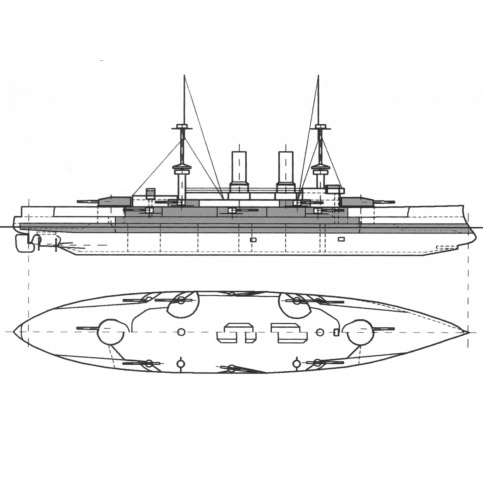

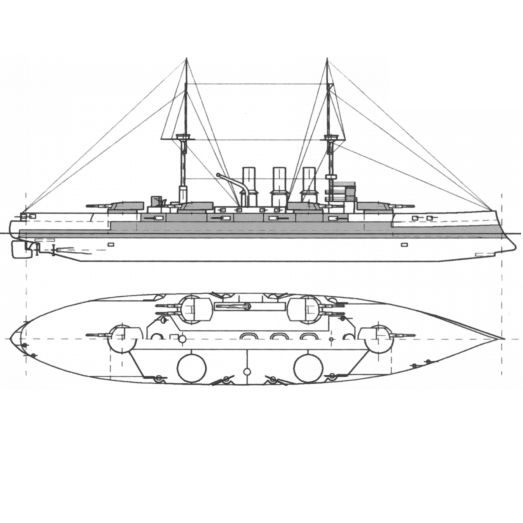

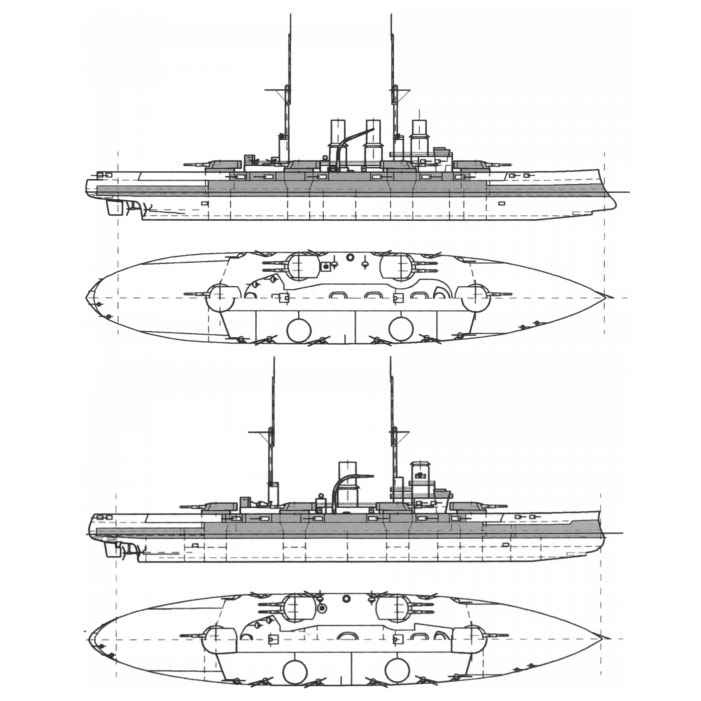

Note: So far i cannot find the original blueprints projects leading to the Nassau class. These are reconstitutions of various projects by Dirk Nottelman published in “Warship International” as part of “From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The Development of the German Navy 1864-1918 serie. Part VI-A: “The Great Step Forward”, Vol. 52, No. 2 (June 2015), pp. 137-174 (38 pages) available in JSTOR.

The “Ersatz Sachsen”

The design team started wotking again on a six 21 cm twin-turrets variant and the first German “all-big-gun” battleships with this time an uprated battery of eight 28 cm guns: It was chosen a mixed approach again with twin axis turrets (two, fore and aft) and the rest in single wing turrets, lighter and narrower. The Kaiser approved the latter design, on 18 March 1905. The work was refined, notably by increasing the beam for better stability, making a ship closer to a pre-dreadnought battleship, and no longer a cruiser by any standard.

It was decided also to rearrange the secondary battery with eight 17 cm (6.7 in) guns in casemates, plus improved main battery turrets. The Kaiser in between received the specs and design of the Italian Regina Elena-class battleships capable of 22 knots and wanted a similar vessel and a return to the previously approved 1903 design.

Before the understandably incoming massive delays in redesign, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz intervened. He pointed out that merging the battleship (monocaliber 28 cm) and armored cruiser (high speed) categories were contradicting the German Naval Law of 1900 clearly separating types, and previously approved. He also argued that the Construction Office was already too busy with other projects, and he manoeuvered to have the Kaiser’s project in the next Naval Law to pushed things forwards.

Based on the new design, he originally requested six of them, plus six armored cruisers (remarkably close to the Japanese naval program by the way). Capital ship designs however had a spiralling cost upward and political opposition increased in the Reichstag, which eventually forced Tirpitz to tone down his request to the six armored cruisers, including one in peacetime reserve -sparing a crew), and 48 xheaper torpedo boats. Tirpitz, to his dismay, would have no battleship approved in 1906.

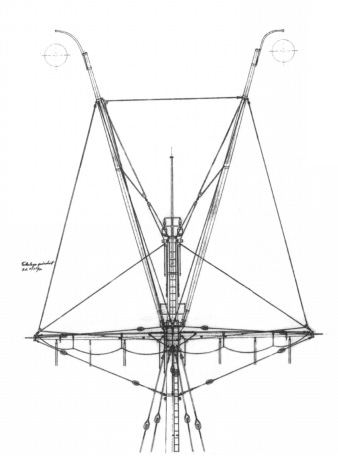

Ersatz Sachsen, alternative lattice masts proposal

Voted on 19 May 1906, the new program registered as the First Amendment to the Naval Law. Funds were allocated however later for two 18,000-ton battleships and a 15,000-ton armored cruiser plus funds to widen the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and enlarge dock facilities, planning for the future. All this largely explained why the Germans seemed late on the game of dreadnoughts: The Emperor’s own direction changes, external competition, and final opposition by the parliament. The first German dreadnoughts could have been programmed in 1904 already. Meanwhile Fisher pressed on with the keel laying in October 1905 and express launch 10 February 1906 of his HMS Dreadnought, creating an international sensation in all admiralties overnight.

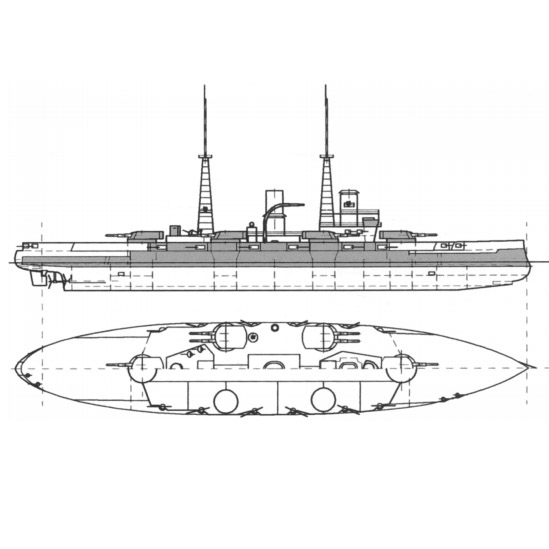

Project F (1905), rejected by Tirpitz

Meanwhile, the design staff continued to refine the new capital ship. It’s only by September 1905 (before the Dreadnought had her keel laid down in HM Dockyard, Portsmouth), that several, supposedly final variants were proposed. Among these, was proposal “F”, which replaced the single-gun by twin-gun turrets, and 17 cm by twelve 15 cm (5.9 in) gun, offering a greater rate of fire. The underwater protection was reworked and greatly improved as well, with a ship even more beamy, now the canal enlargement was approved.

Design “G” was ultimately approved on 4 October with rearranged magazines and boiler rooms on “G2” and a radical variant G3 with all gun turrets on the broadside, soon proved unworkable. “G2” was evetually chosen, but still for continued refinement, as “G7”, then “G7b”, at last approved by the Kaiser, on 3 March 1906, one month after the Dreadnought. The original three funnels was truncated to two, the bow was redesigned as straight, and the very last design “G7d” was approved by the Kaiser on 14 April. Construction was authorized on 31 May and in between, the race to create the blueprints went on. Soon, Tirpitz had the satisfaction (Dreadnought effect!) to have a sister-ship programmed the same fiscal year, and another two in FY1907.

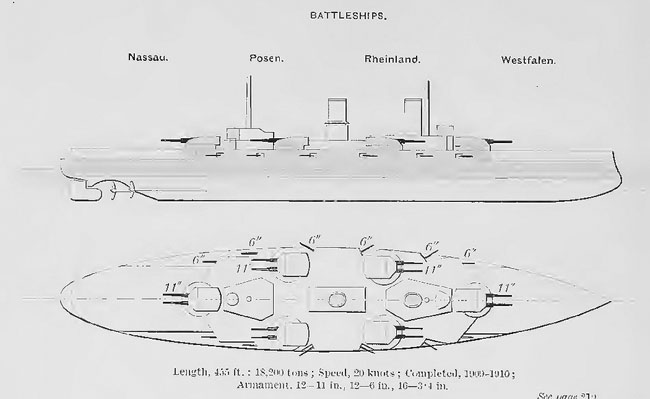

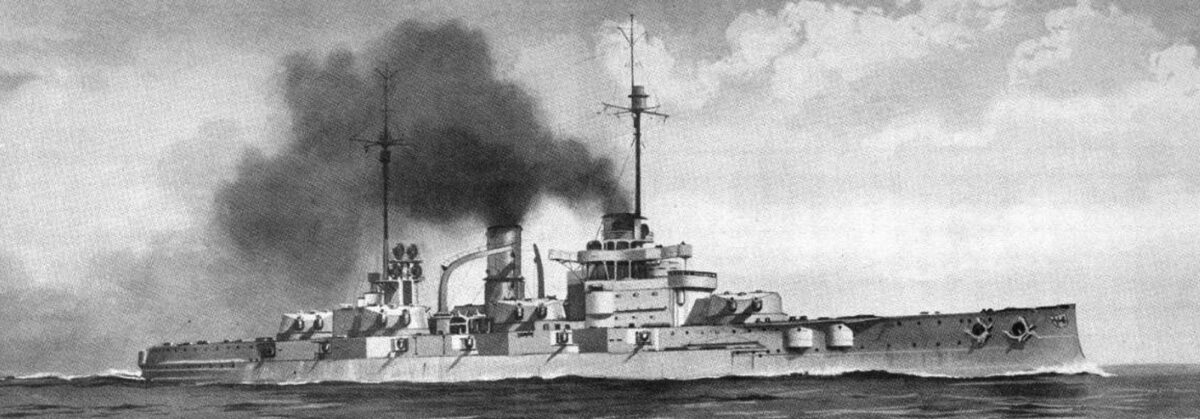

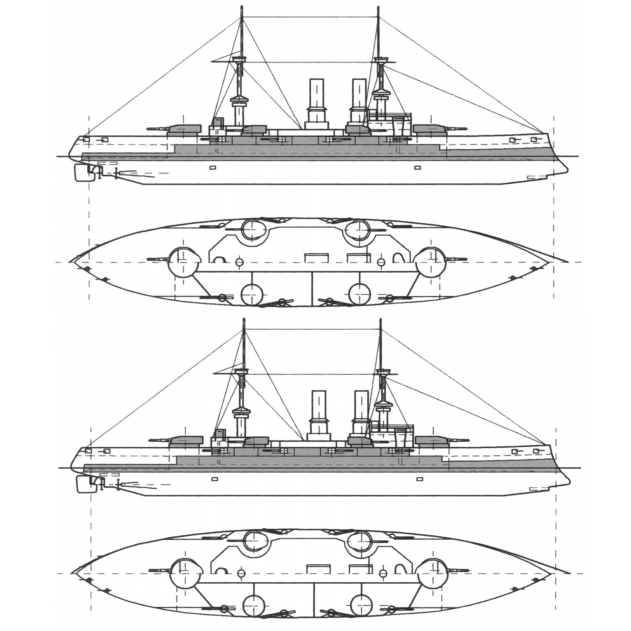

Design

The Nassau class still had a short hull compared to the Dreadnought, only 146.1 m (479 ft 4 in) long, but they were quite beamy at 26.9 m (88 ft 3 in), with a draught of 8.9 m (29 ft 2 in), while their width ratio was 5.45, making them “stubby” or “potty” for the time. Al last, they were supposed a bit more agile and stable. It’s mostly explained by the choice of twin wing turrets rather than single. The admiralty was not diconcerted by the general allure of the ship as they repeated the design (with 12-in guns) for the next Helgoland class. The Nassau class displaced 18,873 metric tons (18,575 long tons) standard and 20,535 t (20,211 long tons) at full load, a bit “light” for dreadnoughts.

Hull and general design

Construction was classic, with steel sections and frames, then rivered outer plating. For ASW protection below the waterline, they had nineteen watertight compartments (Nassau had sixteen), a double bottom for 88% of the keel. The turrets took a large space onboard,so they were two small lozenge-like superstructures fore and aft shaped to maximize the arc of fire of the wings turret, then an intermediate flying deck between the fore and main funnels. There two pole masts fore and aft, the second located at the aft island, with projectors on platforms (eight in all). The superstrcture was quite reduced, with just an enclosed command bridge in front of the conning tower, a formula that was repeated on the next classes. Later in the war, an additional narrow flying bridge was constructed above with repeaters and extending from the platform in front of the main funnel.

Nassau class double gaff pole masts design

The ships carried a number of boats located in the gangway in between funnels and wings turrets, served by two gooseneck cranes abeam the aft funnel: A picket boat (which could be armed with a gun for landing parties), three admiral’s barges, two launches, two cutters, and two dinghies. The peacetime crew reached 40 officers and 968 enlisted men, but the ship could be equipped as squadron flagships and took onboard an extra 13 officers and 66 enlisted men. As flagships, they carried two extra officers and 23 sailors.

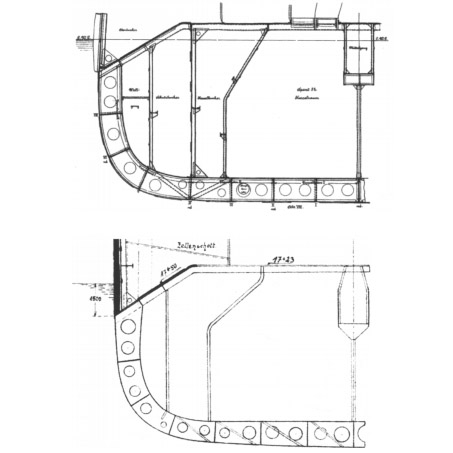

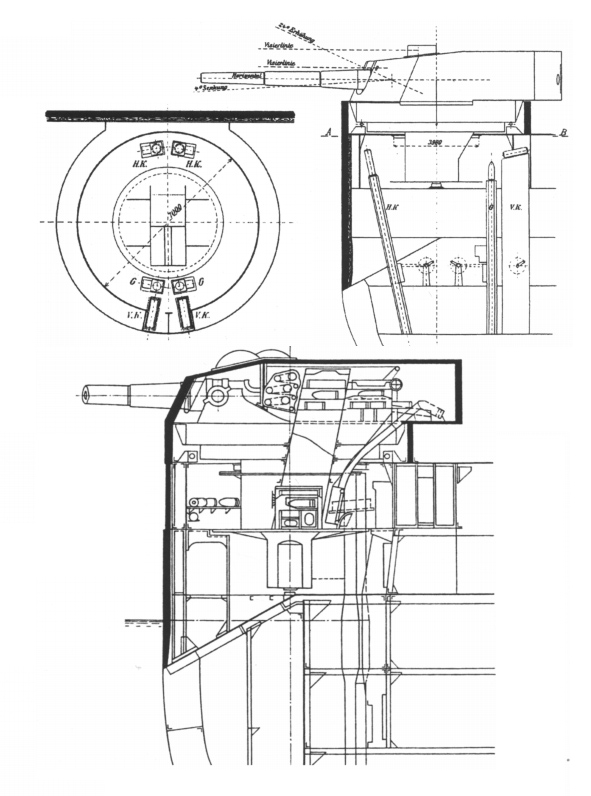

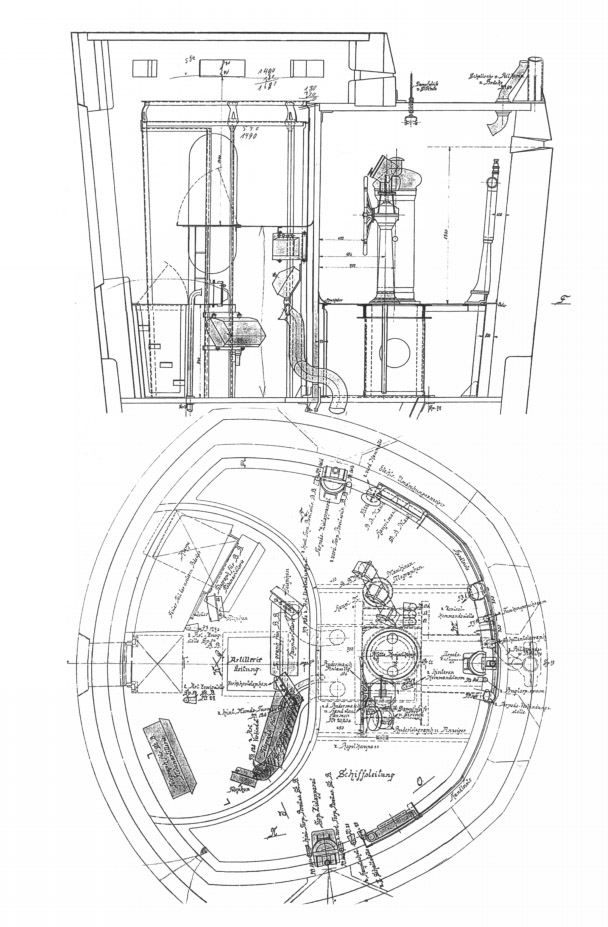

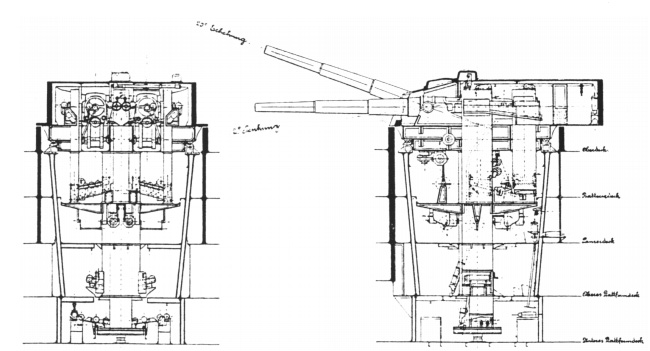

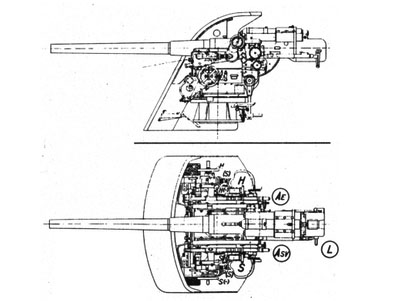

Nassau’s turrets sections

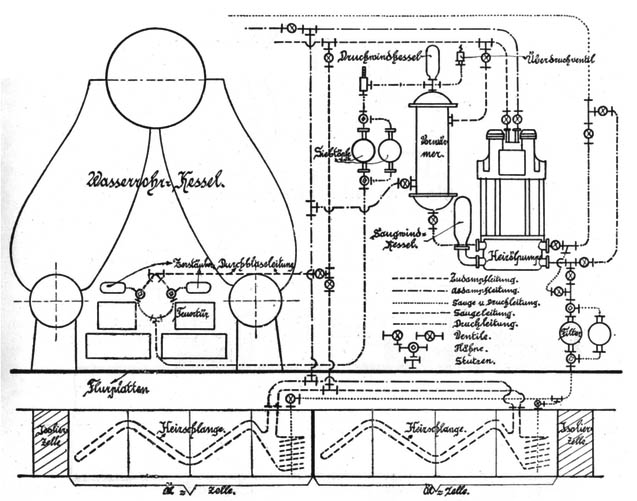

Powerplant

The Nassau class were all equipped with VTE engine, vertical tubes, tripe expansion systems instead of turbines as for HMS Dreadnought. There were reasons behind this choice: Both Tirpitz and the Navy’s construction department resisted the adoption of Parsons turbines “for heavy warships” in 1905. A cost-based decision at first, as Parsons had the monopoly on steam turbines. Appoached by the German admiralty, the company asked one million marks in royalty fee, for every turbine exported. Also, German companies were not ready to produced their own turbines until 1910, at least on a large format. This will have a consequence for the following series, as the Helgoland repeated VTE, and the next Kaiser mixed Turbines and VTE, as the König. But it was not before 1912 Germany had Turbine-driven capital ships.

The Nassau vertical, 3-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines were protected, each in their own engine room and each shaft-driving a 3-bladed screw propeller 5 meters (16 ft) in diameter. Twelve coal-fired, Schulz-Thornycroft water-tube boilers provided steam, themselves separated in their own three boiler rooms (four boilers each). These boilers were ducted into a pair of funnels instead of the three initially planned. In all, this powerplant delivered a maximal output of 22,000 metric horsepower (22,000 ihp) for a 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) top speed.

The Nassau class carried 950 t (930 long tons) of coal in peacetime, normal conditions. In wartime, they can carry up to 2,700 t (2,700 long tons), so thrice that amount, filling usually void underwater bunkers. At 10 knots cruising speed (19 km/h; 12 mph) they could reach 9,400 nautical miles (17,400 km; 10,800 mi), which fell at 12 knots to 8,300 nmi (15,400 km; 9,600 mi), at 16 knots to half that, 4,700 nmi (8,700 km; 5,400 mi) and at battle stations, 19 knots, 2,800 nmi (5,200 km; 3,200 mi). In 1915 during their overhaul, all ships received boilers modifications, with oil sprayers installed to boost their combustion rates. For this, they obtained an extra storage for 160 t of fuel oil.

Performances

On trials, these somewhat pessimistic, or restrained figures were all exceeded, by a wide margin. The Nassau class in fact delivered an output of 26,244 to 28,117 metric horsepower (25,885 to 27,732 ihp) depending on the ships, reulting in top speeds of 20 to 20.2 knots (37.0 to 37.4 km/h; 23.0 to 23.2 mph), which was completely unexpected from their stubby appearance. By comparison, HMS Dreadnought, despite her steam turbines, could only reach 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph)! – This made the four German battleships, not only the fastest VTE-powered vessels in service, but also fastest German capital ships to date, although the Italians still had 22-23 knots dreadnoughts. The Kaiser has its high speed equivalent. Electrical power was provided by eight turbo-generators (1,280 kW – 1,720 hp) rated at 225 V.

Steering power came from two rudders side-by-side. The Nassau class were fast but contrary to what was expected, did not handle particularly well even in calm seas. Their motion appeared quite “stiff” and they rolled excessively in heavy weather, mostly due to the side wight of their wing turrets, which also caused a large metacentric height. They were designed to be very stable gun platforms and it appeared their roll period coincided with the average North Sea swell. To mitigate the roll, bilge keels were later installed. Nevertheless, the ships proved maneuverable enough, with a small turning radius and minor speed loss in heavy seas but 70% at hard rudder, after the roll keels were added especially, which “braked” the motion.

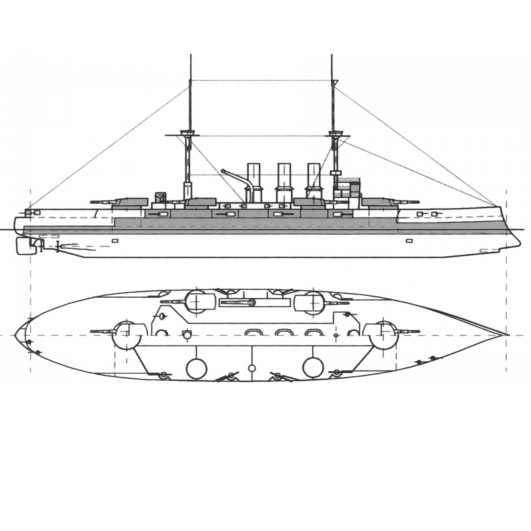

Armour scheme

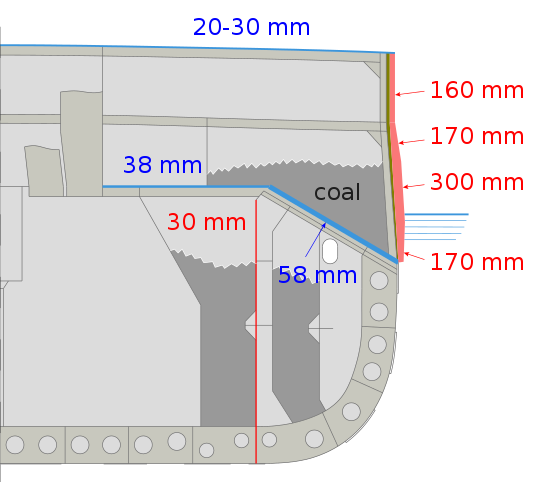

Nassau class armour scheme.

As there were no particular requirements there, engineers started on the known (but unproven) base of the Deutschland class Battleships, but with improved underwater protection as learnt from the Russo-Japanese war. They used Krupp cemented steel armor all around. The basic layout divided comprised three sections: The bow, stern, and central citadel, between the two main barbettes. The citadel comprised a main belt armor at waterline level, connected closed by transverse armored bulkheads. It was supported by a bottom curved armor deck at mid-deck level over the vitals: Machinery spaces and ammunition magazines.

The citadel varied in thickness, lowered to the waterline level forward but aft, it remained at mid-deck level. If the main portion of the belt armor was 29 cm (11.5 in) thick over 1.2 m (4 ft), then 30 cm (11.8 in) it tapered to 17 cm (6.7 in) on the bottom edge over 1.60 m (5.25 ft), below the waterline. The top edge was also thinner, at 17, then 16 cm (6.3 in), reaching the upper deck. The belt outside the citadel was just 14 cm (5.5 in) thick, the tapered dow to 10 cm (4 in) at its extremity. Aft it fell to 13 cm (5 in) and then to 9 cm (3.5 in), closed before reaching the stern proper, enclosed by a 9 cm transverse bulkhead.

The torpedo bulkhead, about five meters behind the belt, was just 3 cm (1.2 in) thick. The underwater compartmentation was split in two, with a serie of void compartments followed by another serie of coal-filled ones. It should be noted that the downward sloped 5,8 cm section behind the main belt was also filled with coal. Behind the torpedo bulkhead, protecting the machinery room proper, was a last internal compartment layer with a 1 cm separation, also full with coal. Engineers found it difficult to mount the torpedo bulkhead during construction, due to the four wing turret’s disruption and their thick barbettes, so close to the hull’s sides.

The casemate battery, was above the central portion of the belt, 16 cm thick as seen above, containing casemated guns and backed by a bulkhead 2 cm (0.8 in) thick. If the main armor deck was 3.8 cm (1.5 in) with same thickness slopes downward, they connected to the bottom edge of the belt, a common design. The slope was 5.8 cm (2.3 in) thick. When all coal bunkers were full, they added some protection by absorbing and distributing the blast energy. The bow and stern sections had 5.6 cm (2.2 in) decks, which went up to 8.1 cm (3.2 in) over the steering compartment. The forecastle deck was protected by 2.5-3.0 cm (1 to 1.2 in) thickness, protecting the secondary battery above the torpedo bulkhead.

The forward conning tower had 30 cm walls, and was topped by a 8 cm (3.1 in) roof, with a smaller gunnery control tower above curved with a 40 cm (15.7 in) thick face. The aft conning tower was of course lighter, with 20 cm (7.9 in) sides and a 5 cm (2 in) roof. Main battery turrets were protected by sloped 28 cm faces, then 22 cm (8.7 in) sides, but 26 cm (10.25 in) rear plates, more for balance than protection. The sloped artificially increased their thicknes in direct fire, estimated above 32 cm. The roof were partly sloped at 9 cm, then flat at 6.1 cm (2.4 in). The secondary casemated gun had 8 cm thick gun shields and separated fro the others by a 2 cm transverse screen stopping fragments. As most dreadnoughts of the time, the Nassau aso received heavy anti-torpedo nets strapped along their side to be deplyed at anchor. They were seen as a liability at sea, causing stablity problems, and were removed after 1916.

- Main Belt: 30 cm (11.8 in)

- Main turrets: 28 cm face and sides

- Battery: 16 cm (6.3 in)

- Conning Tower: 40 cm (15.7 in)

- Torpedo bulkhead: 3 cm (1.2 in)

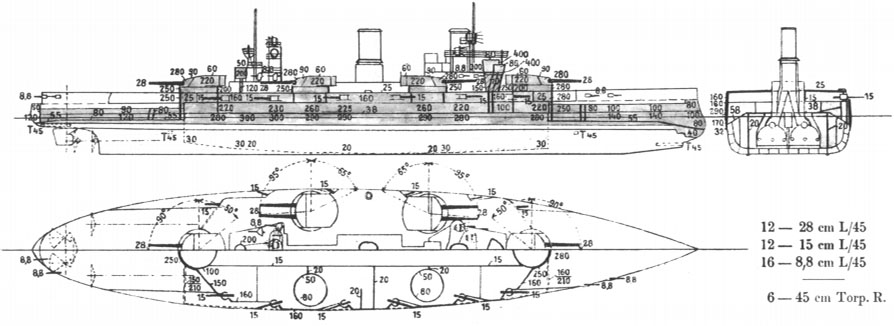

Armament

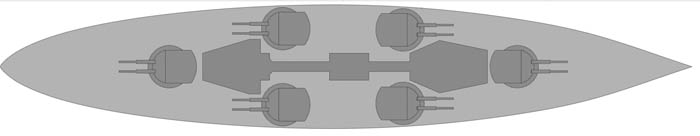

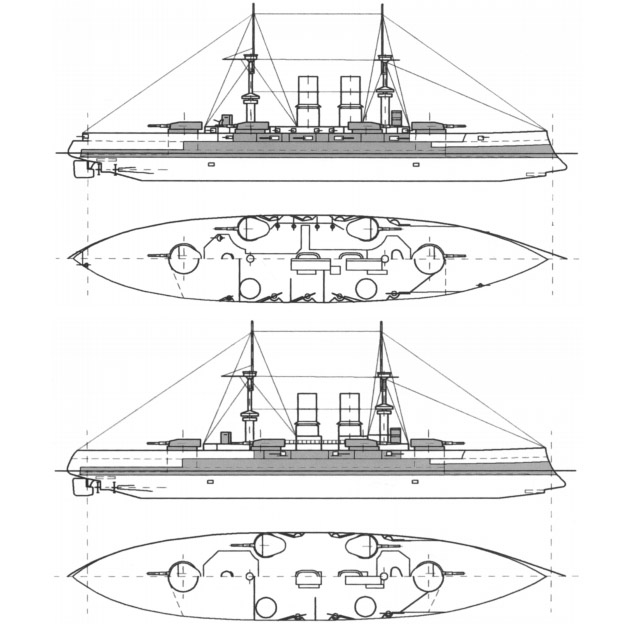

Nassau artillery configuration

Turret arrangement as the Japanese Kawachi class, 4 wing turrets, 2 axis fore and aft, 8 guns broadside. Broadly similar performance to the British 12 in guns. This was a common configuration at the time, as nobody yet tried the superfiring concept, which allowed to add more on the centerline. The vertical triple expansion engines also consumed a lot of internal space, forbidding magazines, which mostly precluded in that case, superfiring centerline turrets. As such, the six twin-gun turrets were placed in an hexagonal configuration.

In a sense it was almost a pre-dreadnought configuration, with two main turrets in the axis fore and aft, and several side turrets (three per side in the case of Nelson, two twin and one single). The Nassau as a result had six guns to bear in chase or retreat, and eight in broadside, on paper, same as HMS Dreadnought and its successors, but with an extra turret in the case of the Nassau-class. It was also believed this arrangement shielded some guns from enemy fire. In fact it made such sense for German engineers, that the scheme was also adopted without change for the next Heligoland class, which were started in 1908. At the time, British battleships still mixed echelon turrets and superfiring ones (St Vincent, Colossus, Neptune). The revolutionary Orion class superdreadnoughts only came a year later.

Main Artillery: 6×2 28 cm SK L/45

Nassau’s C07 turret design

Wings turrets were Drh LC/1906 mounts (as well as centerline for the first two), but Drh LC/1907 for the other pair, with a longer trunk. Both the Drh LC/1906 turrets and 28 cm SK/L45 guns were tailored-designed for the Nassau class. The main battery propellant magazines were located above shell rooms for wings turrets, but not for centerline turrets in Nassau and Westfalen. The shells themseves weighted 302 kgs (666 lb), and they were propelled by a combo of a 24 kg (52.9 lb) fore propellant charge, in silk bags, and a 75 kg (165.3 lb) main charge, in a brass case to reduce risk and make for easier manipulations. Despite of this the process was streamlined enough to procure a rloading rate of 20° the fastest of any capital ship at the time.

- Elevation/depression +20/-8°

- 302 kgs shell, 24 kg fore propellant, 75 kg main charge

- Fast reload time: 20 seconds

- Muzzle velocity 855 m/s (2,810 ft/s)

- Maximum range at 20°, 20,500 m (67,300 ft)

Nassau’s turret distribution

Secondary Artillery: 12x 15 cm SK L/45

In six per side individual casemates along the upper battery deck, part of the hull above the main belt, in indidividual recesses and approximative arc of fire of about 160-180°. They fired exclusively armor-piercing shells. The elevation/traverse and reloading process as well as targeting were all performed manually.

- Elevation/depression +20°/−7°

- Rate of fire: 4-5 per minute.

- 51-kilogram (112 lb) shells, in solidary brass case

- Muzzle velocity: 735 m/s (2,410 ft/s).

- Maximum range: 13,500 m (14,800 yd).

Tertiary Artillery: 8x 8,8 cm SKL

Close-range defense against torpedo boats, designed in 1903 and introduced in 1905. Classic caliber which would eventually last until 1945 in many iterations and for many roles. On the Nassau class, they were placed in casemates: in hull casemates under recesses and semi-sponsons fore and aft (eight), and the remainder in superstructure islands for and aft (eight). The scheme was partially reproduced for the next Helgoland class but eliminated afterwards for superstructure shielded guns, and dual purpose mounts. Aviation was still an unknown factor in 1906. Elevation/training, targeting and loading were all manual. The 22-lb projectiles (9.97 kgs) had solidary brass casings.

- +22° elevation

- Muzzle velocity: 2,133 ft/s (650 m/s),

- Maximum range: 10,500 yards (9,600 m)

In 1915 two hull casemate guns were eliminated and opening plated over, two 8.8 cm Flak guns installed on the superstructures instead and in 1916-17 they were all eliminated (which also freed crew members). These AA guns fired a lighter shell at 2,510 ft/s (765 m/s) and 45° up to 12,900 yards (11,800 m).

Torpedo Tubes: 8x 8,8 cm SKL

A classic at that time, as it was planned to discharged torpedo broadsides during a classic battleline engagement, early on, the Nassau class were provided with with six 45 cm (17.7 in) submerged torpedo tubes. One in the bow (with a characteristic semi-external tube emerging from the underwater icebreaker bow which could be trained thirty degrees to either side. There was another one in the stern, fixed, and two per broadside, outwards of the torpedo bulkhead, which could aimed thirty degrees forward, sixty degrees aft.

- C/06D torpedoes

- Warhead: 122.6 kg (270 lb)

- Top speed (1 setting): 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph)

- Range 6,300 m (20,700 ft)

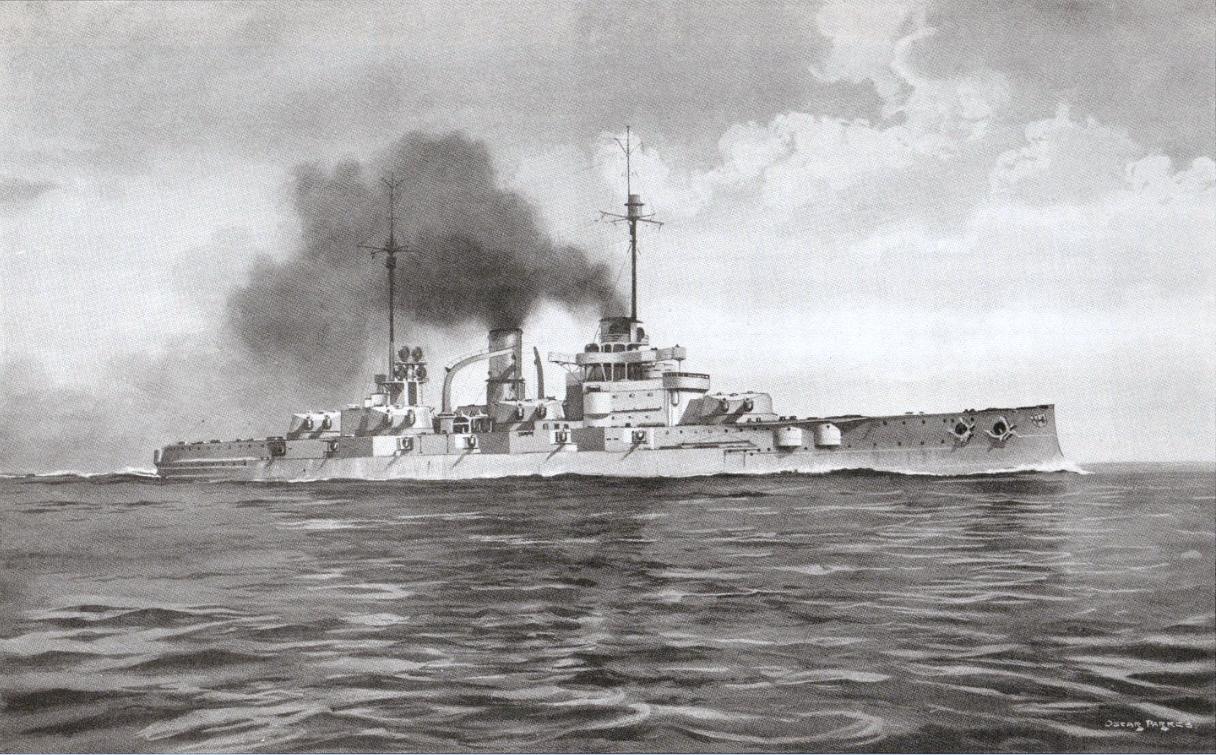

Author’s illustration of the Posen in 1918

⚙ Nassau class specifications |

|

| Displacement | 18,750 t – 21,000 t FL |

| Dimensions | 146.1 x 26.9 x 8.76 m (479 x 88 x 28 ft) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts 3 cyl VTE, 12 Schulz-Thornycroft boilers, 22,000 hp |

| Speed | 19-20.2 knots (37.4 km/h; 23.2 mph) (23.2 knots best trials) |

| Range | 8,300 nmi (15,400 km; 9,600 mi) @12 knots |

| Armament | 12 x 280mm (6×2), 12 x 150mm, 16 x 88mm, 6 TT 450mm Sub |

| Armor | Belt 300, Battery 160, Internal bulkheads 210, Turrets 280, Blockhaus 300, Barbettes 280mm |

| Crew | 1,140 |

SMS Nassau

SMS Nassau

SMS Nassau class

SMS Nassau was ordered as Ersatz Bayern (replacing SMS Bayern), laid down on 22 July 1907 in Kaiserliche Werft, Wilhelmshaven, number 30 under absolute secrecy with detachments of soldiers tasked with guarding the shipyard itself and all sub-contractors such as Krupp. Launched on 7 March 1908, christened by Princess Hilda of Nassau in presence of Kaiser Wilhelm II and Prince Henry of the Netherlands for the House of Orange-Nassau. Fitting-out work was delayed when a dockyard worker accidentally removed a blanking plate from a large pipe, which flooded the ship, without yet her watertight bulkheads installed.

In fact SMS Nassau even sank 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) to the bottom of the dock, but water was pumped dry and she was cleaned out for weeks and months, son only completed by the end of September 1909, then commissioned on 1st October 1909, making her sea trials, many months after HMS Dreadnought, but showing she was faster. On 16 October 1909 with SMS Westfalen she took part in the opening ceremony of the Wilhelmshaven Naval Dockyard’s 3rd entrance. After annual maneuvers in February 1910 (still on trials, until 3 May), she joined the I Battle Squadron.

Four four years, her routing comprised series of squadron maneuvers, training cruises, and the annual fleet manoeuvers. The summer training cruise of 1912 (Agadir Crisis) saw her confined in the Baltic. On 14 July 1914, she was to start her Norway summer cruiser, soon cancelled by Wilhelm II after two weeks, back in late July in port, preparing for war, which broke off between Austria-Hungary and Serbia on the 28th. In a week, full conflict had Germany at war with Russia and France.

Nassau as part of her unit was in all Hochseeflotte deployments in the North Sea, at first to cover Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper, at the head of the battlecruisers wing raiding Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby on 15–16 December 1914, and covered by 12 dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts, on 15 December, just 10 nmi of a six British battleships squadron. Darkness between screening destroyer convince Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, under the Kaiser’s orders to not risk the fleet, broke off.

Battle Riga Gulf (August 1915)

In cover of the capture of Riga by the German Army, and in search of the Russian pre-dreadnought battleship Slava, a German naval force was sent, preceded by minesweepers and TBs into the gulf entrance. Nassau and her three sister ships were mustered as well as the four Helgoland-class and the battlecrusiers Von der Tann, Moltke, and Seydlitz under Vice Admiral Franz von Hipper’s command. The battleships stayed at a distant cover on 8 August and the operations started again on 16 August 1915.

SMS Nassau and Posen this time went further, covered by four light cruisers, 31 torpedo boats. The German minesweeper T 46 and V 99 were lost in minefields, but Nassau and Posen engaged the Russian Slava, managing three hits which forced her to retreat. On 19 August, minefields being cleared, the flotilla entered the gulf but was repelled by reports of British submarines in the area, Nassau and Posen remaining however in the Gulf until 21 August, destroying with other vessels the Russian gunboats Sivuch and Korietz. Later Riga was capture and the gulf entirely secured. Further advances would take place in 1917, but focus soon returned to the north sea.

Battle of Jutland (May 1916)

SMS Nassau underway, Jane’s postwar illustration

SMS Nassau was largely inactive for the rest of 1915 and early 1916, but made sweeps in distant cover in other operations. At last, she took part in the Battle of Jutland with the II Division, I Battle Squadron. The latter formed the center of battle line, preceded by Rear Admiral Behncke’s III Battle Squadron, followed by Rear Admiral Mauve’s II Battle Squadron’s pre-dreadnoughts. SMS Nassau was third in line, behind Rheinland, in front of Westfalen while SMS Posen was at the head as squadron’s flagship. The night time reorganization for a cruising formation was inadvertently reversed: SMS Nassau now became the second ship in line, and ws soon found in action.

At 17:48-17:52 indeed, the eleven German dreadnoughts were engaged by the Grand Fleet, duelling with the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron first, Nassau targeting HMS Southampton and believed to score at least one one hit from 20,100 yd (18,400 m), on the cruiser’s port side but causing little damage. Next Nassau targeted HMS Dublin but the exchange was over at 18:10, and later at 19:33, Nassau spotted HMS Warspite, both briefly exchanging before making a 180-degree turn away, and thus beyond range.

Nassau, while proceeding home, crossed again during the night (at 22:00) British light forces (SMS Caroline, Comus, Royalist) and with Westfalen, made a 68° turn to evade possible torpedoes from them. Both targeted HMS Caroline and Royalist from 8,000 yd (7,300 m), but the latter turned away and soon back, making another torpedo run, Caroline firing two at SMS Nassau, the first close to her bows, the second under her belly.

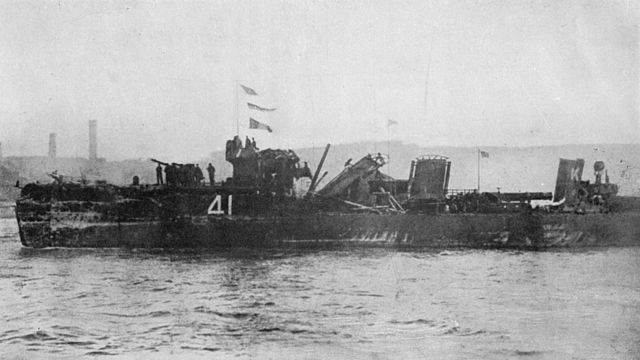

HMS Caroline

Midnight, 1 June, saw a large manoeuver behind the British Grand Fleet in its way when the Hochseefotte crossed the path again of British destroyers. SMS Nassau was torpedo assaulted by HMS Spitfire, which missed, and the latter was at such close distance her captain attempting a ramming, that could undoubtely cut her in half. The destroyer was caught and tried to evade but too late, and collided with Nassau in an oblique angle, while the battleship fired her main battery at point-blank range, max depression. But if the shells went above, the blast however was itself sufficient to destroy Spitfire’s bridge, incinerating all the staff onboard.

HMS Spitfire, showing her battle damage after Jutland.

Crippled, Spitfire disengaged but with a 6 m (20 ft) Nassau’s side plating chunk strapped on her hull. Nassau had a 15 cm casemated gun disable and a 3.5 m (11.5 ft) gash above the waterline, which caused some flooding, slowin her down to 15 knots until she reached home. British destroyers present landed on her two 4 inshells, damaging her searchlights.

After 01:00, Nassau and Thüringen crossed the path of the armored cruiser HMS Black Prince, and Thüringen opened fire first, making 27 heavy-caliber hits, 24 secondary in quick succession. Nassau and Ostfriesland soon also opened fire and later SMS Friedrich der Grosse, which disabled the cruiser, soon ablaze and immobilized, then, she exploded and sank. But as she did, Nassau as steaming on her wreck, and manoeuvered to avoid it, steering hard towards III Battle Squadron, at reversed steam to avoid collision with SMS Kaiserin.

Nassau came back in line, but between the pre-dreadnoughts SMS Hessen and Hannover. She was attacked agains at 03:00 by British destroyers and tne minutes later her lookouts spotted three to four of them, port. Sjhe immediately opened fire at circa 5,500 yd-4,400 yd, but soon made a hard turn to avoid possible torpedoes. This was the last tense moment of the battle. Back in German waters, Nassau, Posen and Westfalen took up defensive positions in the Jade roadstead, waitiong a possible arrival of the pursuing British Grand Fleet. Unbeknown to them, Jellicoe folded up in between.

Nassau received two hits, only by secondary shells, with little damage. Apart her hull damage and casualties or 11 men killed, 16 wounded she was still fully operational. She spent 106 main battery shells, 75 secondary and even some 8,8 cm at the destroyers. After repairs, she was back in her unit on 10 July 1916.

Later operations

With the 1st and second squadron

She took part, as distant cover, to the 18–22 August fleet advance, behind the I Scouting Group battlecruisers shelling Sunderland. The battlecruisers were assisted by Markgraf, Grosser Kurfürst, and Bayern. On 19 August, SMS Westfalen was torpedoed by the HMS E23, just 55 nautical miles north of Terschelling and she had to return to port while the Grand Fleet departed. By 14:35, Admiral Scheer retreated.

Nassau’s second sortie on 19–20 October 1916 was uneventful. She ran aground on 21 December, in the mouth of the Elbe however, and if she was able to free herself, repairs were needed on Hamburg (Reihersteig Dockyard), until 1 February 1917. She took part in the cover for the raid on Norway on 23–25 April 1917, soon canceled when Moltke lost her propeller. Nassau, Ostfriesland, and Thüringen became a special unit for Operation Schlußstein, the planned assault and captured of Saint Petersburg.

On 8 August, Nassau embarked some 250 soldiers in Wilhelmshaven for this mission, but as the the three ships reached the Baltic on 10 August, the operation was postponed and later canceled., their unit being dissolved on 21 August, and they headed back to Wilhelmshaven. Nassau was schefuled to take part in the final fleet action planned in late October 1918, under overall command of Großadmiral R. Scheer. On the morning of 29 October 1918, order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven, but on this night, sailors on Thüringen mutinied, soon spreading on other battleships, including Nassau, leading to the cancellation of the whole operation.

After November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet was interned in Scapa Flow but Nassau and her three sisters were not listed for internment, remaining in German ports, in part, like the pre-dreadnoughts, to their age. Hermann Bauer became SMS Nassau’s last commander. On 21 June 1919 the scuttling took place at Scapa and back in Germany, it was decided to hand over the four Nassau class to the various Allied powers, as replacements for ships sunk. Nassau was awarded to Japan, on 7 April 1920, but the latter declined and ordered her to be scrapped instead by a British ccompany in Dordrecht, by June 1920.

SMS Westfalen

SMS Westfalen

SMS Westfalen underway

SMS Westfalen was ordered as “Ersatz Sachsen”replacing the old 1880s Sachsen-class ironclad of the same name. The Reichstag in fact secretly approved and provided funds by late March 1906, construction was delayed however unlike Nassau, waiting for arms and armor to procured, under very strict security. Laid down on 12 August 1907 (AG Weser shipyard, Bremen), she was launched on 1 July 1908 without much fanfare, was fitted-out and transferred to Kiel on mid-September 1909 to gather her final crew, as she transited with dockyard workers, helped by pontoons as the Weser River was very low at this time of year, and it took two attempts before cleared the river.

On 16 October 1909, before commission, she took part in the third set of locks, Kaiser Wilhelm Canal opening ceremony like her sister ship and she was commissioned a month later, making fleet training exercises in February 1910. It’s only by 3 May she completed her full trials. Assigned to the I Battle Squadron and in 1912, squadron flagship in place of SMS Hannover, she performed the same training routine as Nassau.

Early Operations

Westfalen’s wartime service was very much the same as Nassau, as they operated in the same unit; She participated the raid of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby (15–16 December 1914) as rear cover, and then took part in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915, also to provide cover for the forces engaging the Russian flotilla. She did not really saw action on the second attempt on 16 August 1915, as only Nassau and Posen were detach to attack Slava. Reports of Allied submarines in the area had everyone packing on the 17.

Back in the north sea via the Kiel canal at the end of August, SMS Westfalen took part in a sweep into the North Sea on 11–12 September, but seeing no action. Yet again, she was in another on 23–24 October and again on 21–22 April 1916. Westfalen was part of the battleship support for Hipper’s battlecruisers attacking Yarmouth and Lowestoft also on 24–25 April and the whole operation was soon called off. The real test came out in the last day of May 1916:

SMS Westfalen at Jutland

Under overall command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer, and under Captain Redlich’s command, she departed the Jade at 03:30 on 31 May as distant cover with the II Division, I Battle Squadron (Rear Admiral W. Engelhardt), last ship in line, astern of her three sisters. Also the II Division was the last unit of dreadnoughts in the fleet, followed by pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron. There were few chances they would be engaged, however the confusion of the evening and night action had it all reversed. The veteran dreadnought suddenly were found at the hearth of the storm.

At 17:48-17:52, eleven German dreadnoughts opened fire on the British 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, in poor visibility and unclear results. At 18:05, SMS Westfalen spotted again and fired on a light cruiser, assumed later to be HMS Southampton. Shells were fired from 18,000 metres (19,690 yd), but she scored no hits. Like the rest of the battle line she was ordered at maximum speed in pursuit (20 knots) and at 19:30, Scheer signaled “Go west”, as spotting the Grand Fleet deployed to face them a second time. With the battle line reversed her Squadron was now in the lead, Westfalen now assuming a lead position.

Around 21:20, SMS Westfalen therefore was the first spotted and engaged by the British battlecruisers of the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron, soon straddled and showered with seawater and splinters. lookout soon spotted two torpedo tracks that turned out to be imaginary, but she was forced to slow down, allowing the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group to pass ahead. At around 22:00, SMS Westfalen and Rheinland spotted an unknown force in the falling darkness, flashing a challenge via searchlight, ignored, and immediately turning away to starboard, to avoid possible incoming torpedoes, the rest of the I Battle Squadron following behind. Westfalen fired seven main shells in afew miniuted of visibility, and was still in the lead, Scheer still weary about torpedoes.

At about 00:30, the line spotted British destroyers and cruisers, followed by an intense exchange at close range. Westfalen engaged HMS Tipperary, with her 15 cm and 8.8 cm guns at just 1,800 m (2,000 yd). Her bridge and forward deck gun were soon blasted out, and she fired 92 secondary, 45 tertiary rounds at Tipperary, then turned to 90 degrees to starboard, to evade her possible torpedoes. Nassau soon joined in the attack on Tipperary, which was finished off and sank, not before launching her two remainder starboard torpedoes.

Westfalen’s bridge was also hit by a 4-inch shell, killing two men in the staff, wounding eight, including Captain Redlich. At 00:50, Westfalen spotted HMS Broke, a British destroyer leader, briefly engaged her with her 15 cm battery. In 45 seconds she fired about 40 shells (plus 30 8.8 cm shells) and turned away again to avoid possible torpedoes. Broke was later engaged by other battleshps and the cruiser Rostock and soon was in “an absolute shambles” but withdrawned successfully to tell the tale. At about 01:00, Westfalen’s searchlights fell on HMS Fortune soon targeted point-blank and set ablaze with also Westfalen and Rheinland. She also spotted HMS Turbulent and wrecked her too, as she soon sank in turn.

The night fighting kept all onboard Westfalen in high alert, but eventually the High Seas Fleet managed to punch through the curtain of British destroyer, ultimately reaching Horns Reef before dawn, at around 4:00 AM, on 1 June. She was still in the lead, with little damage, and many shells spent, guns barrels still hot. She reached Wilhelmshaven in the early hours, taking up defensive positions in the outer roadstead for a possible arrival of Jellicoes’s Grand Fleet. When counts were made, it was reported she fired 51 28 cm shells, 176 15 cm rounds, and 106 8.8 cm shells. Repair was performed quickly in Wilhelmshaven, over by 17 June.

Sunderland Raid (18–19 August 1916) and aftermath

Westfalen was part of the fleet advance of 18–22 August, in cover of the I Scouting Group battlecruisers shelling the city of Sunderland, in the hope drawing out Beatty’s battlecruisers. Westfalen was at the rear of the line, lioke at jutland. At 06:00 on 19 August, she was spotted and torpedoed by the British submarine HMS E23, 55 nautical miles (102 km; 63 mi) north of Terschelling. 800 metric tons of seawater entered her gash, but the torpedo bulkhead held form and nothing happened to her powerplant, still dry and fully operational. However it was decided to send her back to port, with an escort of three torpedo-boats, at 14 knots all the way. German plans were known and so, the Grand Fleet was en route to block their way back home and at 14:35, Admiral Scheer, warned of this, retreated.

Westfalen’s repairs were over on 26 September and she trained in the Baltic Sea, being back in the north sea on 4 October. She took part in a sortie to the the Dogger Bank on 19–20 October, without action. She remained inactive for the majority of 1917 and was not called for Operation Albion in the Baltic, staying in Apenrade to prevent a British incursion there.

Invasion of Åland and fate

On 22 February 1918, Westfalen and Rheinland departed to Finland, in support of the German army deployed as the Finns were in-fighting for their independence and between the “Whites” and the “Reds”. On 23 February, they carried the 14th Jäger Battalion on 24 February, heading for Åland island, to become the German forward operating base in reach of the port of Hanko and a stepping point to seize the capital, Helsinki. The task force arrived on 5 March, metting the neutral fleet deployed there: The Swedish coastal defense ships Sverige, Thor, and Oscar II. Negotiations followed and the Germans were granted to land German troops on Åland as planned, on 7 March, and as it was done, Westfalen was ordered back to Danzig.

She remained there until 31 March, and returned to Finland with SMS Posen, off Russarö, the outer defense of Hanko on 3 April, bombardrded. Soon the army took the port and both Battleships proceeded to Helsingfors, and on 9 April, Reval, where Westfalen took command of the invasion force. On the 11th, she passed off Helsingfors, landed troops and supported their advance until the Red Guards were defeated. She remained there until 30 April, until a Finn White government was installed.

Soon, SMS Westfalen was back to the North Sea, assigned to the I Battle Squadron. On 11 August with Posen, Kaiser, and Kaiserin she was ordered to patrol off Terschelling, but she suffered en route serious damage to her boilers (near explosion) that limuted her for 16 kn until she reached her support position and back to port. It was judged not sound to repair or change her boilers se she remained stationary, decommissioned, employed as an artillery training ship for the remainder of the war.

In November 1918, she was not interned to Scapa Flow and so remained where she was, and after the scuttling, the Allies demanded replacements for the ships sunk in Scapa, so Westfalen was struck on 5 November 1919, handed over as “D” on 5 August 1920, but promptly sold to ship-breakers in Birkenhead, BU on 1924.

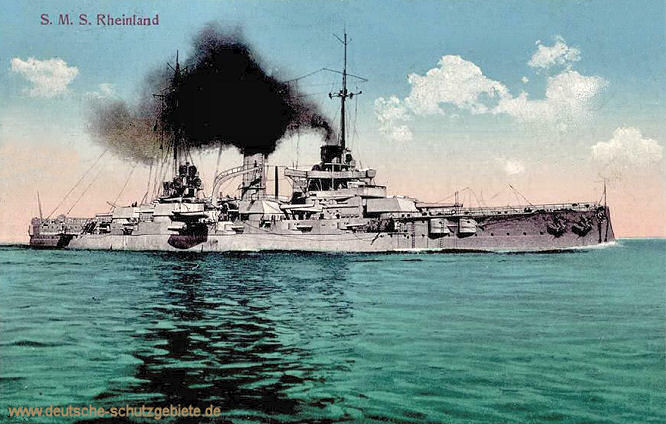

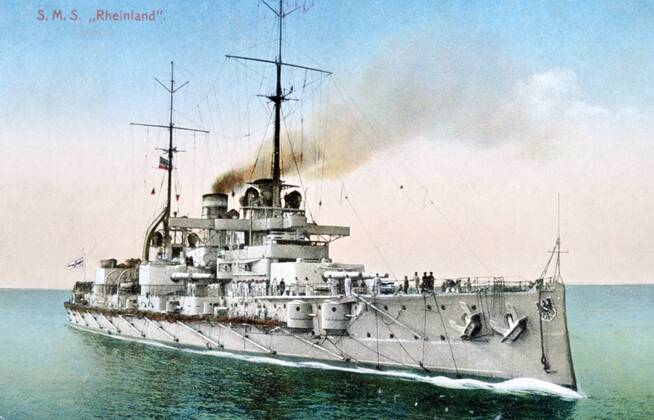

SMS Rheinland

SMS Rheinland

SMS Rheinland

SMS Rheinland was ordered as “Ersatz Württemberg” to replace this third Sachsen-class ironclad, laid down on 1 June 1907 at AG Vulcan shipyard, Stettin. Construction proceeded under absolute secrecy until she was launched on 26 September 1908, christened by Queen Elisabeth of Romania, Clemens Freiherr von Schorlemer-Lieser. Fitting-out ended in February 1910 and she was commissioned under Kapitän zur See (KzS) Albert Hopman, in command until August. Limited sea trials until 4 March 1910 off Swinemünde ended on Kiel for full commission on 30 April 1910, followed by additional sea trials in the Baltic Sea.

From 30 August 1910, Rheinland was taken to Wilhelmshave as her first crew was transferred to the new battlecruiser SMS Von der Tann. Her new captain (temporarily) was Korvettenkapitän Wilhelm Bunnemann in limited commission, in September 1910. (KzS) Albert Hopman returned to the ship later that month, until September 1911. He was replaced by KzS Richard Engel, until August 1915.

After autumn fleet maneuvers new crewmembers from the pre-dreadnought Zähringen arrived, and she was assigned to the Ist Battle Squadron. In October 1910 she took part in the annual winter cruise, then fleet exercises in November, alternated with summer cruises to Norway, eaxch time in August 1911, 1913, and 1914.

SMS Rheinland participated in distant cover of the Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby raid, but also at the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915, under overall command of Vice Admiral Franz von Hipper. The operation was successful on 16 August 1915 but only Nassau and Posen saw action. She was later back in the north sea, made a sweep on 11–12 September, then 23–24 October. KzS Heinrich Rohardt took command until December 1916. From 12 February 1916, she underwent an extensive drydock overhaul until 19 April. She participated next in another north sea sweep on 21–22 April and later, as cover again of the I Scouting Group battlecruisers, for the planned Yarmouth and Lowestoft raid of 24–25 April, called off when Seydlitz was damaged.

The first real test of SMS Rheinland came with the Battle of Jutland: As part of the III Battle Squadron she departed the Jade at 03:30 on 31 May, and was reassigned to the II Division, I Battle Squadron (Admiral W. Engelhardt), second ship in the division astern of Posen, ahead of Nassau and Westfalen, in the last unit of dreadnoughts in the fleet followed by pre-dreadnoughts. She engaged the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron and engaged in bad weather HMS Southampton, scoring no hit.

After a complete reverse manoeuvers, SMS Rheinland became third behind Westfalen and Nassau. At 21:22, her spotters Rheinland spotted two fancy torpedo tracks, slowing down to make the battlecruisers pass ahead. Around 22:00, Rheinland and Westfalen spotted light forces, challenged by searchlight, followed by a torpedo evading measure, and later the group identified a large dark gray warship motionless in the water, with four tall and thin smoke stacks which happened to be HMS Black Prince.

A night clash erupted with British destroyers and cruisers at 3:00, with close range firing from Rheinland on HMS Black Prince at 2,200-2,600 m (2,400 to 2,800 yd), followed by a torpedo avoiding manoeuver. At 00:36, Rheinland was hit by two 6-inch (15 cm) shells from HMS Black Prince, one cutting cables to the four forward searchlights also piercing the forward funnel. The second exploded on the forward armored transverse bulkhead, doing little damage as it was not penetrated. 45 minutes of intense exchanges interrupted by the arrival of HMS Ardent, saw Black Prince eventually pounded to oblivion by SMS Ostfriesland.

The Hochseeflotte reached Horns Reef by 04:00 on 1 June and SMS Rheinland was in Wilhelmshaven a few hours later to be refueled and re-armed for a possible Grand Fleet arrival with her three sisters stood out in the roadstead. Reported stated she had fired 35 28 cm (11 in) shells, and 26 15 cm (5.9 in), had 10 men killed, 20 wounded but Repair work was completed by 10 June.

The rest of the war was calmer, apart a fleet advance on 18–22 August behind the I Scouting Group battlecruisers attacking Sunderland, but followed by a quick a retreat to German ports. She later was detached to cover a sweep by torpedo boats on 25–26 September. She also took part in the fleet advance on 18–20 October. In early 1917 she was placed as permanent sentry, in the German Bight. In the summer, her crew showed signs of rebellion mostly bevcause of the poor quality of the food, and she was left behind during Operation Albion. She stayed in the western Baltic, guarding the Skagerrak against a possible British sweep in the aid of the Russians.

On 22 February 1918 like SMS Westfalen, Rheinland (Now under command of Korvettenkapitän Theodor von Gorrissen, until September 1918), were tasked to a support mission in Finland with the German army. It was seen above already for her sister-ship for the details. The operations proceeded from 6 March, under a Senior Naval Commander, until 10 April. She proceeded to Helsinki, encountered heavy fog en route to refuel in Dantzig, and ran aground on Lagskär Island at 07:30, killing two men, and causing great damage.

The rocks pierced the hull, which was flooed, loosing three boiler rooms. A small fleets of tuges and tother ships tried to have her refloated without success on 18–20 April and the crew was removed temporarily, reassigned to the pre-dreadnought SMS Schlesien. On 8 May 1818, a floating crane came from Danzig to lift out the main guns and turret armor, bow and citadel armor, ill about 6,400 metric tons , almost 1/3 of her normal displacement. She was strapped with floating pontoons to add buoyancy and eventually refloated by 9 July 1918. Towed to Mariehamn for limited repairs, on 24 July she departed for Kiel with two tug boats but it was decided upon arrival repairs were not worth it. She was decommissioned on 4 October, becaoming a barracks ship in Kiel. Her last captains were KzS Ernst Toussaint for a month and then Fregattenkapitän Friedrich Berger from September 1918 until her decommissioning on 4 October, as depot/barrack ship.

Struck from the German naval list on 5 November 1919 she was handed over to the allied commission, which sold her on 28 June 1920 to ship-breakers in Dordrecht. Towed there, she was BU from 29 July until late 1920. Her bell could be seen at the Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr in Dresden.

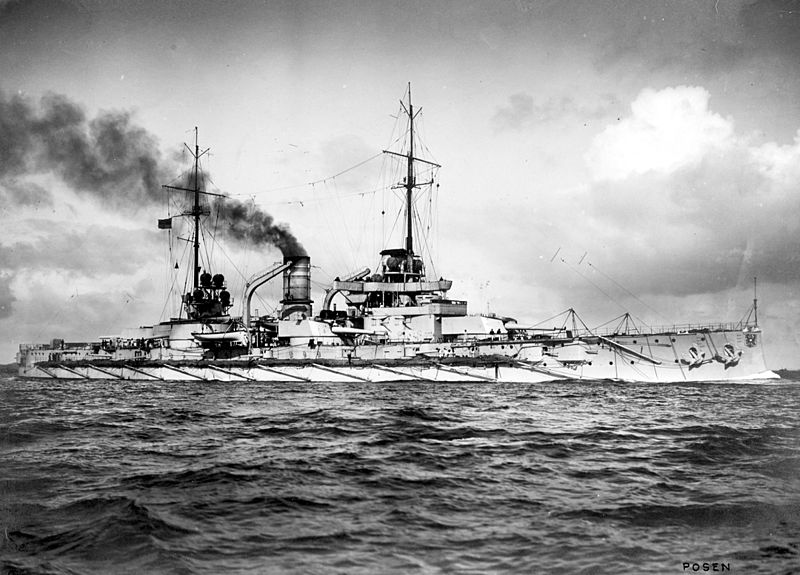

SMS Posen

SMS Posen

SMS Posen underway, USN archives (Lib. of Congress).

SMS Posen started life as “Ersatz Baden” replacement for her namesake in the Sachsen-class ironclads, laid down on 11 June 1907 at Germaniawerft shipyard, Kiel. Like the others, built under absolute secrecy she was launched on 12 December 1908 with Wilhelm August Hans von Waldow-Reitzenstein in the attendence, making her trials in April 1910 before being fitting-out in May, and be commissioned on the 31rh, making her final Sea trials until 27 August.

After completing her trials in August 1910, she headed from Kiel for Wilhelmshaven, and from 7 September was crewed by the old pre-dreadnought Wittelsbach decommissioned on 20 September. Later she integrated the II Division, I Battle Squadron, as a flagship. She entered the prewar years of routine training, fleet exercizes and summer cruises in Norway, starting with a training cruise into the Baltic. Her 1914 cruise was however interrupted by the incident in Sarajevo. She was back in Wilhelmshaven on 29 July.

On 4 August, the UK was at war with Germany and the Hochseeflotte was mobilized to take on the Royal Navy in the north sea. SMS Posen made a serie of covering sorties for the I Scouting Group, at first raising the coast and shalling cities in the hop to draw out Beatty’s battlecruisers and destroy them. After the first raid on 15–16 December, Posen took part in the the expedition and Battle of the Gulf of Riga, starting in August 1915. As part of the “special unit” her only opposition was to be the pre-dreadnought battleship Slava.

In addition to the four Nassau, the four Helgoland-class were also mobilized, plus the battlecruisers Von der Tann, Moltke, and Seydlitz and some pre-dreadnoughts as cover against a sortie of the Russian flotilla. The second minesweeping attempt was successful on 16 August, Posen and Nassau being detached to lead the charge though the defenses of the gulf, Posen being Admiral Schmidt’s flagship in this operation. They were screened with four light cruisers and no less than 31 torpedo boats.

The first day, the minesweeper T46 and the destroyer V99 were sunk but Posen and Nassau sank or badly damaged the Russian gunboats Sivuch and Korietz. On the 17th, Posen and Nassau also engaged Slava at long range, scoring three hits, forcing her back to port. From 19 August, all Russian minefields were cleared for the flotilla to proceed into the gulf, until reports of Allied submarines had everydone packing up.

By late August, Posen was back in the North Sea, making a sweep on 11–12 September, without result, another on 23–24 October. On 4 March 1916, with her sisters and Von der Tann they sailed to Amrumbank, protecting the returning cruiser Möwe from a raiding mission. She made another sortie on 21–22 April and was in support for Hipper’s battlecruisers raiding Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April, called off due to Seydlitz’s damage;

Posen’s real test in this war came at Jutland: On 31 May, as part of the II Division, I Battle Squadron, flagship, Rear Admiral W. Engelhardt, Posen was leading the division. II Division was last in the battle order though. After engaging the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, in poor weather, she started to straddle British destroyers, notably HMS Nomad and Nestor, in particular the later with her secondary battery. She exploded and sank, notablyt due to the combined fire of eight dreadnougts. At 20:15, the whole lined veered away as encountering the Grand Fleet for a second time and Posen ended fourth in line, not a favourable command position for a flagship…

At 21:20, Posen and the others engaged the British battlecruisers of the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron. Posen was the only one to effectively spot and fire on HMS Princess Royal and Indomitable, from 21:28, at 10,000 m (11,000 yd), scoring one hot on Princess Royal and straddling Indomitable, until 21:35. From then, darkness engulfed the combatants, and having no radar, the situation became stressful. The order was not to steam away and back to port. The Britush meanwhile launched their light forces in the hope of catching up, shadowing the fleet, attacking it with vigorious torpedo strikes and slowing it down for the Grand fleet at dawn.

At about 00:30, there was a violent firefight at close range. Posen fired on several unidentified British warships, narrowly friendly-fired on SMS Elbing, passing through the German line, just in front of Posen, so close in fact she was rammed by the later. If Posen’s strenghtend bow was undamaged, Elbing had her engine rooms flooded and two hours later while in repairs, she spotted approaching British destroyers, her captain order to scuttle his ship.

About 01:00, a fierce firefight with British destroyers started, Posen engaging HMS Fortune, Porpoise, and Garland at around 800 and 1,600 m (870 and 1,750 yd), using projectors and its 8,8 cm guns. HMS Porpoise was almost destroyed, Fortune quickly too, but torpedoes were fired, that Posen evaded, breaking its fire. At 01:25, Westfalen illuminated Ardent, crippled at 1,000 to 1,200 m.

The High Seas Fleet eventually made it through to Horns Reef on 1 June, taking up defensive positions in the outer roadstead. it was time for a report: Posen expended 53 28 cm shells, 64 15 cm rounds, and 32 8.8 cm shells, with no casuatly on board, which was northing short of a miracle considering the action, and compared to her sisters.

From June 1917, Posen had a new captain, Wilhelm von Krosigk, until November 1918. No notable sortie was done after Jutland. In February 1918, however, Posen and her unit was mobilized for a sortie in Finland, support of the German army, and in support of the “White Finns” trying to keep away the Soviet Red Guards and “red finns” from their newly constituted country. On 23 February, Westfalen and Rheinland were assigned to the Sonderverband Ostsee while Posen stayed in Dantzig.

SMS Posen underway

She departed on 31 March Posen with Westfalen for Russarö, outer defense ring of Hanko on 3 April and the port was seized. Next they steamed to Helsingfors on 11 April landing soldiers. Posen’s crew suffered however had four men killed and twelve wounded in the cover attack. From 18 to 20 April, SMS Posen assisted tried to free Rheinland, grounded, wthout success. She later struck a sunken wreck in Helsingfors harbor. On 30 April, she was detached from the Sonderverband Ostsee back to to Germany for repairs, being back in Kiel on 3 May and its drydock. Repairs ended on 5 May. Nothing much happened in June-July.

On 11 August 1918, with her sister SMS Westfalen, and Kaiser, Kaiserin, she sortied from Wilhelmshaven in support of a torpedo boats raid off Terschelling. On 2 October, she steamed in the outer roadsteads of the Jade this time in cover of returning U-boats from the Flanders Flotilla. She was part of the fleet planned to ake the famous “last stand” attack on 30 October, which never took place due to widespread mutiny withing the Kaiserliches Marine. Posen and the other ships of I Battle Squadron were sent back to the roadstead on 3 November, and from there, to Wilhelmshaven on 6 November 1918.

On 11 November 1918, Posen was seized as replacement for ships lost in Scapa and, while stricken, she was handed over to Great Britain, transferred on 13 May 1920 and in November, driven ashore at Hawkcraig, Fife, Scotland, then sold Posen for BU in the Netherlands, Dordrecht, in 1922.

Links & resources

SMS Rheinland, postcard

SMS Rheinland, postcard

SMS Nassau, stern view, colorized by Irootoko JR

Books

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-1921.

Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers 1905–1970: Historical Development of the Capital Ship. Doubleday.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1977). Preston, Antony (ed.). “German Dreadnoughts and Their Protection”. Conway

Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Kaiser’s Battlefleet: German Capital Ships 1871–1918. Seaforth Publishing

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations

Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis

Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Humanity Books

Ireland, Bernard (1996). Jane’s Battleships of the 20th Century. New York: Harper Collins Publishing

Lyon, Hugh; Moore, John E. (1987) [1978]. The Encyclopedia of the World’s Warships.

Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel. New York: Ballantine Books.

Nottlemann, Dirk (2015). “From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The Development of the German Navy 1864–1918

Philbin, Tobias R. III (1982). Admiral Hipper: The Inconvenient Hero. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 1: Deutschland, Nassau and Helgoland Classes. Osprey

Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. Cassell Military

Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Seaforth

Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (1999). Von der Nassau – zur König-Klasse. Bernard & Graefe Verlag

Linienschiffe: Von der Nassau- zur König-Klasse, Gerhard Koop, Klaus-Peter Schmolke

Die Linienschiffe der Nassau- bis König-Klasse Eine Bild- und Plandokumentation, Gerhard Koop, Klaus-Peter Schmolke

Links

From Ironclads to Dreadnoughts: The German Navy 864-1918 by Dirk Nottelmann

On deutsche-schutzgebiete.de

On historyofwar.org

Cutaway of the SMS Rheinland

Nassau class on wikipedia

Model Kits

Nassau, general query on scalemates

The 1/250 paper model HMV

Not much: SMS Nassau, ModellbauRay 1:700, or the paper model 3046 by HMV, 2017 1:250, or the rare De Agostini Warships DAKS34 Nassau-class Diecast Model at 1:1250 Scale.

3D rendition gallery

The German Battleship SMS Posen, Super Drawings in 3D Nr. 16053, Marsden Samuel, Gary Staff

Help support Naval Encyclopedia !

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign