The Landing Darling (06/06/2022)

Few crafts in WW2 were underrated but these “Higgins Boats”. The LCVP has been absolutely crucial to the Allied victory From the shores of Africa to the European Western Front. It became as instrumental as the Jeep or GMC truck on land, not a proper military asset but still a vital part of the industrial effort, ensuring troops arrived where they were needed in the way that mattered the most.

Technically however, this was not an intimidating sight. A wooden bucket, not very seaworthy, slow, very lightly protected and light armed, hardly anyone would have predicted it a war-winning solution. But the LCVP for “Landing Craft, Vehicles & Personel” became the Navy equivalent of the acronym “Jeep”, the only way to transition from an assault ship to the beach. And it filled its role perfectly, sometimes compared in importance to the equally successful DUKW, an amphibious GMC truck.

“Andrew Higgins … is the man who won the war for us. … If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different”

“The Jeep, the Dakota, and the Landing Craft were the three tools that won the war.”Supreme allied commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower

“The Higgins boats broke the gridlock on the ship-to-shore movement. It is impossible to overstate the tactical advantages this craft gave U.S. amphibious commanders in World War II.”

Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret)

“(…The LCVPs) did more to win the war in the Pacific than any other single piece of equipment.”

General “Howling Mad” Smith, USMC (Ret)

They were designed out of necessity, but did not came out from the blue, and were entrusted not to take any strategic materials on a southern (Florida) specialist of small, fast, flat wooden boats. They will enter history both as a type, and the most produced in history at the same time: The LCVP was part of all amphibious operations from late 1942, meaning Torch, Husky (Sicily), Baytown (Italy), Overlord and Anvil Dragoon in France, could not have been done without these landing crafts, as well as many operations involving the army in addition to the Marines in the Pacific ibn 1943-44, even some river crossing, but the one on the Rhine. Not bad for a tiny wooden flat boat.

This “D-Day special” post is complementary to two other massive sections:

Genesis of the design

The road to this kind of landing craft was not a straight one: At first, Andrew Higgins, a businessman of New Orleans, manufacturing small, fast flat boats used by trappers, oil-drillers even smuggler during the prohibition, was hit hard by the 1929 crisis until approached by the USMC which looked for a particular boat. Specifications led to the shallpow-draft “Eureka boat”, both tested by the USMC and marketed with some success.

The 1926 Eureka boat, it’s best seller, had a draft such that it could swim on just 18 inches of water while running through dense vegetation and over logs and debris, its propeller safe in a tunnel. It could beach anywhere and extract itself with ease. The Eureka boat was tested by the Marines on Lake Ponchartrain seawall and it’s ruggedness was in part due to its very strong bow piece, the “headlog” or “spoonbill bow”, deep vee hull forward and reverse-curve section amidships with flat sections aft, semi-tunnel for the propeller shaft. It could easily back away and protect it’s vitals thanks to this very unusual recessed propeller cavity and unusual concave shape forward reversing into a convex shape aft, it’s drademark keep for all its boats.

But the USMC is not the US Navy. The administration seemingly wanted to advance its own tailored in-house designs. Time and again, these Navy Boats were tested and rejected by the USMC: Their draft was often too deep and thus, could not getting close to the beach, leaving the Marines almost head-deep to fend off the waves by foot for long distances, or their draft at the contrary way too shallow so they were tossed about in the surf. Both their propellers or rudders were also damaged in the proces, not even speaking of the damage caused by rocks. There was ot satisifying way of exiting the boat also. Like the landing parties of old, performed with standard dinghies and yawls, troops just climbed over the side, under potential enemy fire. They were also not agile.

Higgins obtained in fact this list of grievance and perfectly knew he had the answer. He could convinced some USMC officers but it was another story for the USN at large. But he tried, showing his boat time and again, making them run in shallow water at relatively high speed, turning almost within their own length, doing hard beachings and back down with ease, loaded or unloaded. Undeterred, Higgins showcased time and agin his boat With only minor modifications, from the original Marine Corps exercises in early 1939 where it gain very favorable reviews to the LCP(L), at first a “USMC affair” which already saw extensive service, but mostly with with British forces. No doubt admiralty top commander Admiral Ernest J. King had other preoccupations than these little wooden boats. The LCP(L), once adopted, secured Higging place among Navy providers.

The LCP series

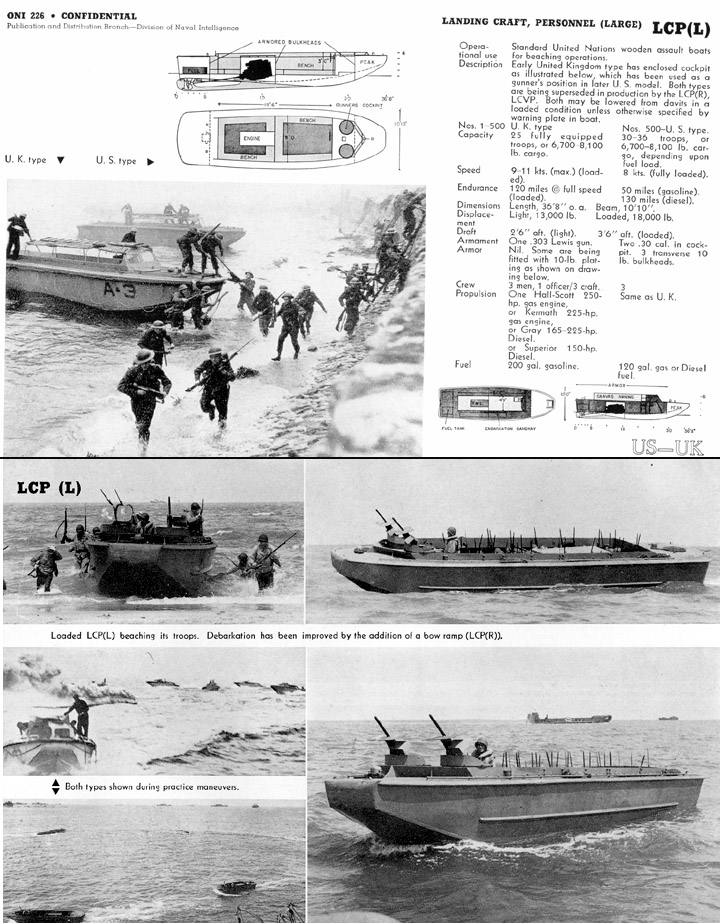

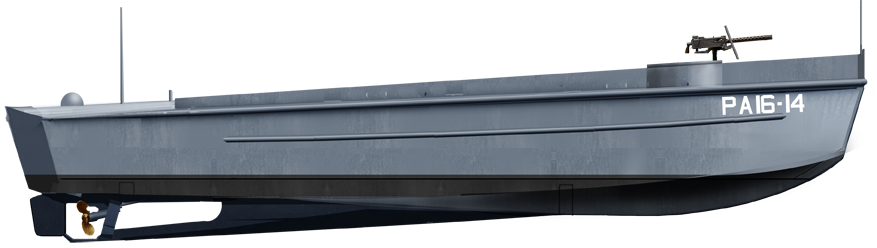

ONI depiction and dataset of the LCP(L)

Indeed until then, the Navy has been constantly frustrated at the solutions given by the Bureau of Construction and Repair. Proposals were off-the-mark contraptions, heavy and ungainly, unpractical and costly. This eventually pushed for a foray in the private sector and specialists such as Higgins were soon contracted. His Eureka boat proved the best contender, but also the company would be qually praised for it’s MTBs sent in the Pacific. It soon gave birth to the LCP(L) for Landing Craft, Personnel (Large) in which 25 fully equipped troops (or 8,100 Ibs of cargo) bench-seated, which had to jump overboard when beached. The British version had a cabin at the front, US versions had two machine-gun positions instead. Propulsion was by diesel, installed almost in the center.

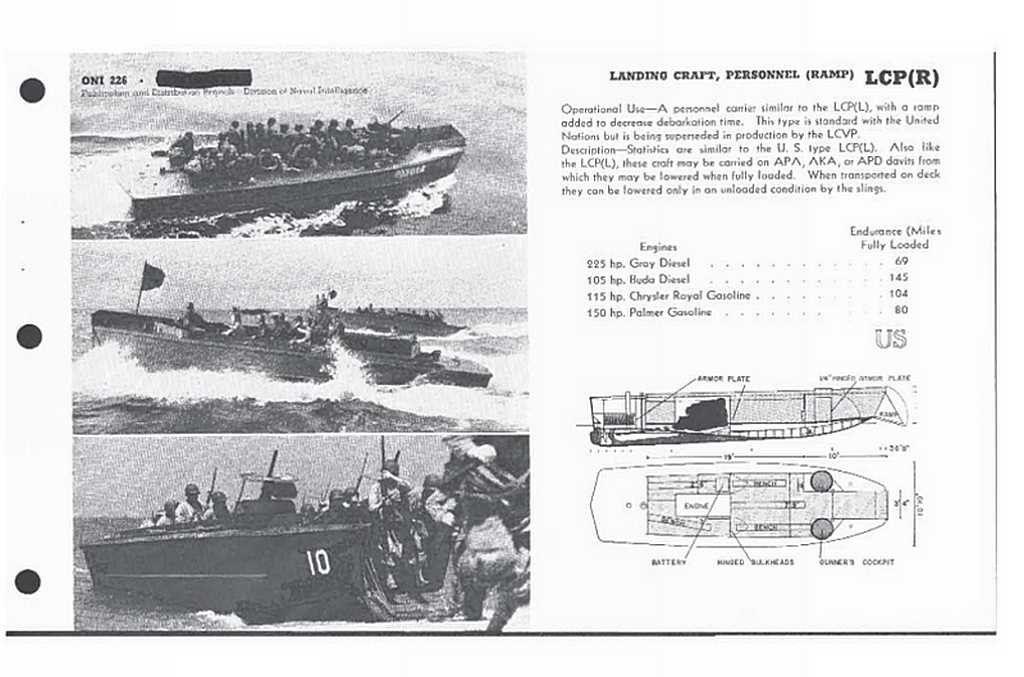

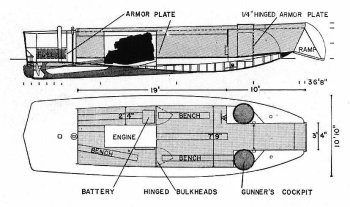

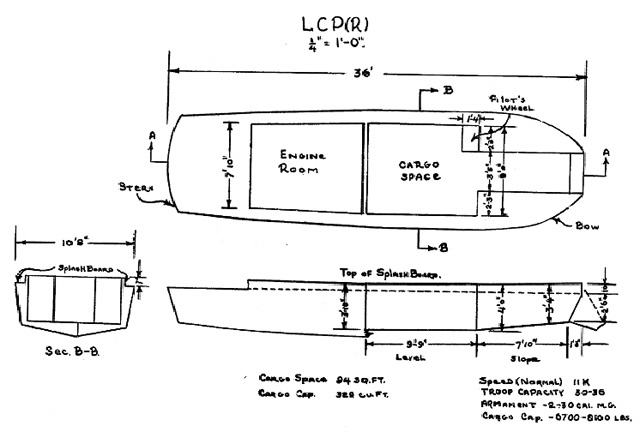

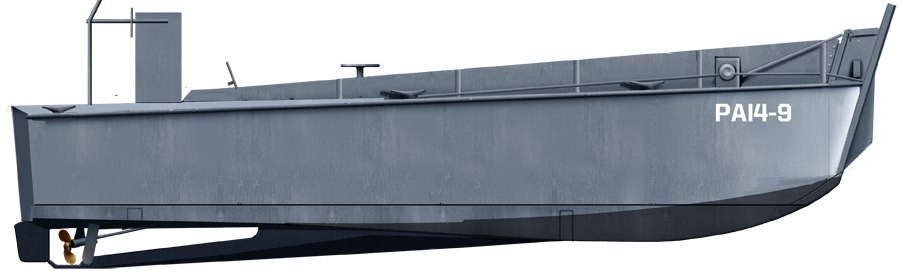

ONI depiction and dataset of the LCP(R)

The LCP(L) was followed by the LCP(R). The first one was criticized as the Marines had to jump overboard, exposing themselves to enemy fire. The next iteration was naturally to procure them some minimal protection in the shape of a small ramp foward, hence the “R” for “ramp”. Like the previous boat, it was wooden, with the engine in the middle-rear, ususllay a 225 hp Gray Diesel (69 nm endurance). The ramp was not initially intended for protection but rather for faster disembarkation. At least the troops did not have to fell waist-deep alongside the boat.

For it’s roots, US Intel produced the Navy photos of the earlier Japanese Daihatsu-class already used in the second Sino-Japanese War. The Navy and Marine Corps also had observers and saw them in action in 1937 at the Battle of Shanghai. Victor H. Krulak was one of these officers, which came to Andrew Higgins with a picture of one of these, back in April 1941 during a meeting in Quantico. Thus Higgins was briefed and started studies long before the Navy came out with any specification.

This was the origin of the ramped version of the LCP(L) which just entered production. Higgins briefed his designers and from his bureau came out with three crafts as a private venture, classed at first as a 36ft LCP(L) to be tested internally, from 21 May on Lake Pontchartrain. The Navy was next to be shown the definitive model, and enthusiastically asked for the production of the LCP(R) as soon as possible. Given Higgin’s confifence in its new design, retooling and a new facility already started in prevision.

This was the origin of the ramped version of the LCP(L) which just entered production. Higgins briefed his designers and from his bureau came out with three crafts as a private venture, classed at first as a 36ft LCP(L) to be tested internally, from 21 May on Lake Pontchartrain. The Navy was next to be shown the definitive model, and enthusiastically asked for the production of the LCP(R) as soon as possible. Given Higgin’s confifence in its new design, retooling and a new facility already started in prevision.

Like the previous LCP(L) they were armed with two forward gunner’s positions alongside the forward hull section, framing the ramp and bringing close support. The LCPs of both types had the same dimensions and the new converted or buuilt assault ships were designed to carry as much as possible. They were stored in davits, empty, lowered at sea and the troops came on board by the use of rope nets. This was a hazardous procedure, which was not modified until the end of the war and introduction in small numbers of the LSD or floating drydocks we are familiar today.

We need a vehicle in it ! Here comes the LCVP

First draft of the LCP(R)

Higgins also was well received by the Coast Guard but still banged heads with the Navy, noy part of its exclusive and comfortable circle of regular shipyards and shipbuilders. The Navy farvored at the time still another in-house landing boat design but eventually some wetn overhead to apply pressure and pierce the bureaucratic immobilism. They played the strengths of Higgins’ design to the full, and with the right support, it eventually won out a contract for a full-width bow ramp demonstration boat.

The LCP indeed had its advantages, but it’s ramp had major issues though, and the Marines wanted to improve on the design if possible. At first glance, the small cargo space compared to the engine compartment, and small ramp aft, were a siginificant loss in internal space. With a larger ramp, more troops could be carried and cargo could be easier to unload as well. More so, if the deck was reinforced, it could accomodate a small vehicle, such as the Jeep. And if possible, offering a better protection. The concept of the LCVP was born.

The semi-armoured LCVP this time came from a Navy request, not a private venture. To carry 36 fully-equipped infantrymen and the same payload, Higgin’s design team had to take a more radical approach. To have a larger ramp and forward section, thus more space forward, both machine-gunners were moved to the back, while the engine was moved more to the rear, now at about 1/3 keel lenght.

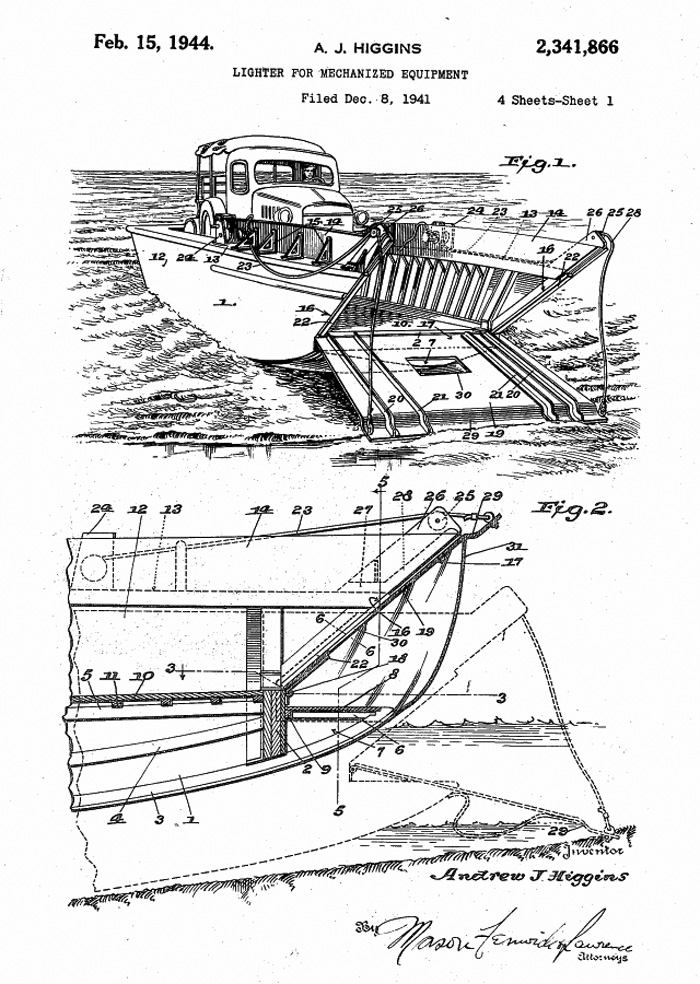

The new boat still used the same shape recipe under the hull, but with the larger, reinforced ramp, using metal this time, bith to support the vehicle, heavy payloads, and protect at the same time the troops onboard. It was even compounded by taller sides, elimination of bunks, so that the troops would go standing, meaning more could be carried, reaching the desired number. It drew only 3 feet of water aft, 2 feet forward and run up onto the beach and then easily reverse back into deeper water as intended. The large steel ramp dropped quickly to unload men, allowing a full beach rotation in the matter of a few minutes. For his model, Higgins was awarded the US Patent Nos. 2,144,111; and 2,341,866. For all his models (including PT Boats) he would have 18 Patents.

Design

Early patent filed on Dec. 8, 1941, about the ramp system. The optimistic depiction shows a small US Truck well at the back. In reality the final boat could only carry a Jeep or Dodge heavier vehicle, but the system could depict a LCM.

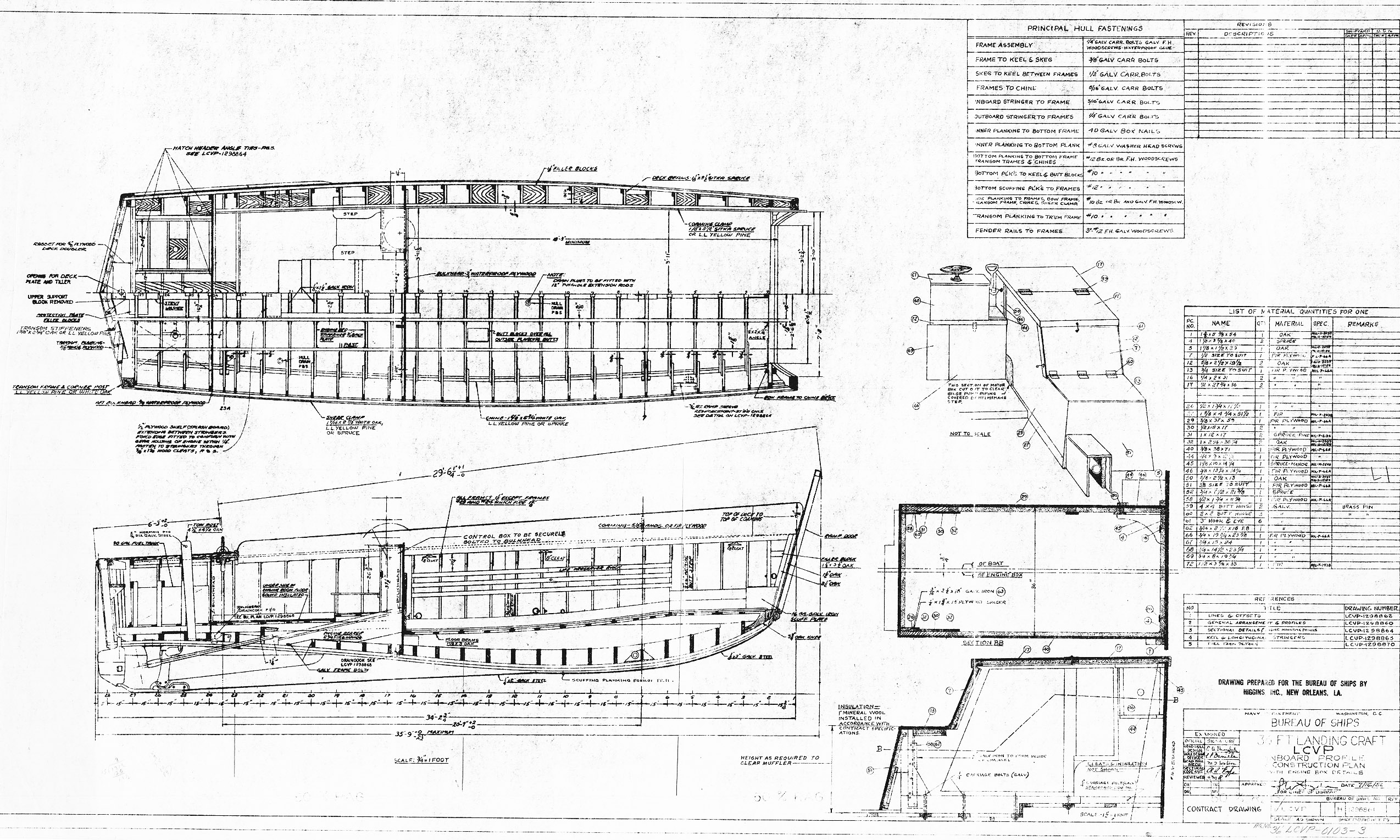

The basic shape was kept, with a “Vee” under the belly and another, inverted, to house the propeller, protected by a keel wth a single rudder. The concave part of the belly housed the shaft and propeller which went above directly to the engine in a short, very angled way in order to keep the aft section compact. Thus despite a generous payload area, the boat was still light and compact. A precious requirement as it had to be carried by rail and also bee lowered from standard USN assault ships davits (see later).

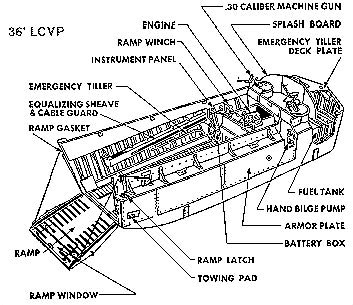

Hull

The LCVP was constructed from wood, with an agglomerate mix of oak, pine and mahogany. On the forward open section for the troops, 0.2 in (5 mm) of Special Treatment Steel armour plating was added, three plates either side rovered to the wooden structure. For the forward protection, a tall, steel bow ramp was also installed, which acted as frontal armour. The ramp was lowever and lifted by the way of two pulley chains logded in the ramp gasket with a ramp latch and towing pad, like a medieval drawbridge.

The LCVP was constructed from wood, with an agglomerate mix of oak, pine and mahogany. On the forward open section for the troops, 0.2 in (5 mm) of Special Treatment Steel armour plating was added, three plates either side rovered to the wooden structure. For the forward protection, a tall, steel bow ramp was also installed, which acted as frontal armour. The ramp was lowever and lifted by the way of two pulley chains logded in the ramp gasket with a ramp latch and towing pad, like a medieval drawbridge.

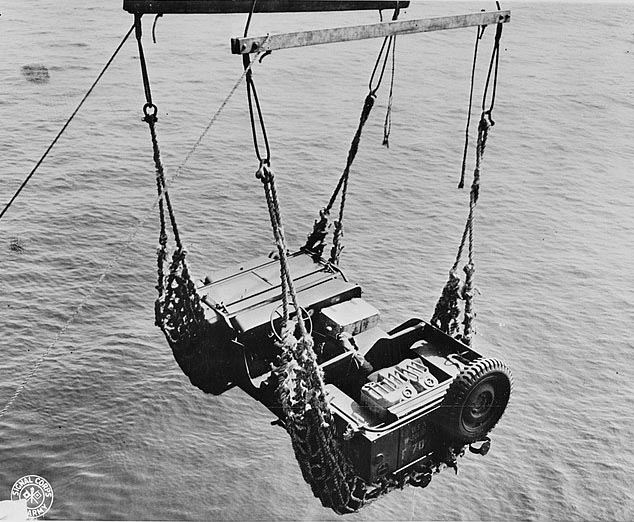

Inside the main troop compartment there were no bunks but a simple track at the floor and some hooks to have a Jeep or even a Dodge WC-51. The troops standed but could hold to a cable guard placed next to the equalizing sheave. Also for unloading fixed stowage there was a ramp winh installed next to the engine, on the right.

Behind the driver’s open section, the hull contained two gunners positions, each with it’s own “foxhole” and pintle to man a .30 caliber Machine gun.

Powerplant

Most LCVPs were powered by the same 225hp Gray Marine 64HN9 diesel engine as the earlier versions, bt there were varants, notably due to other manufacturers also producing the LCVP. The 6 cylinders, Gray Marine 64HN9/64HN5 diesel engine delivered was perfect for the task, reasonably compact and tall but narrow. A 6-cylinder 2 cycle 4-1/4 inches bore, 5 inches stroke rated for 225 hp, at 2100 rpm. It was salt-water cooled with a filter, electrically-started and with a right-hand rotation. Its weight was 2950 Ibs. Gear ratio was 1.5-1. They were manufactured at Corpus Christi and San Diego in California. After the war they were sold as surplus at 2500$ apiece, 2775$ for a 64HN9.

It was simple to maintain and protected in its own “stowage bin” easily accessible aft, under a two-folded hatch, hunged in the middle. There was a cranckshaft to the left connected to a small gearbox activated by foot pedals and a simple wheel for direction. So the driver standed next to the engine and could se forward through the opening of the ramp. The drive also had it’s own small and simple instrument panel with basic informations, speed, rpm, oil level, heat and some switches plus the starter. Also close to him into the wall and at the feet was installed the bilge pump, also activated like the wing by the diesel. The fuel tanks were located on either sides of the compartment behind him, close to the MG-gunners.

In alternative, a 250 hp, 6 cyl. Hall Scott gasoline unit. The maximum speed was 10 knots when fully loaded, the range was 110 nm which was twice that of the previous LCP. This enable for example the assault ships to remain further away, to operate “waiting patterns” running circles until every boat was loaded and ready for the final coordinated push, or the make several waves without being refuelled, and carry back the wounded or supplies when possible. It depended of local conditions and notably the tide. On the long, flat, tidy beaches of D-Day for example, many LCVPs simply were left stranded. At Anvil Dragoon or Salerno this was more a rocky, gravel shore, and the boats could disengage more easily.

Armament

The standard was two 0.3 inches M1919 machine guns mounted on the aft deck, on standard pintles also found on many vehicles of the US Army. These pintle mount M40 type Small Naval pintle, were a very rare equipment, Manufactured from 1942 to 1943 for exclusive LCVP use. They were designed for use with a COLT .30 caliber oak ammo box. They had a limited elevation for AA cover.

They authorized direct ground support with a range of 2,500 yards and more if needed, but only 1,000-1,500 effective, with tracers helping guide the weapon. Both gunners had to spend their 250 rounds ammo before reloading; a process that can take 10-15 sec. for a trained operator. I have bo idea how much ammo boxes could be stored at the feet of the MG operators, but there was ample room inside the LCVP for fifty of so ammo boxes and possibly a few spare barrels, ensuring constant fire for two hours or more.

The Machine Gun, Caliber .30, Browning, M1919A4 had the following characteristics:

- Mass 31 lb (14 kg)

- Lenght 37.94 in (964 mm)

- Barrel lenght 24 in (610 mm)

- Cartridge .30-06 Springfield

- Action: Recoil-operated/short-recoil operation, bolt closed.

- Rate of fire: 400–600 round/min (1200–1500 for AN/M2 variant)

- Muzzle velocity 2,800 ft/s (853 m/s)

- Effective firing range: 1,500 yd (1,400 m)

- 250-round belt

As for heavy armament, the pintle was not large enough to house another type of armament. Indeed, fitting a cal.50 was envisioned, or even a 20 mm Oerlikon, but these boats were just too cramped for this. This would have required redesigning the whole rear section. The manhole of the MG gunner was too cramped for the size and recoil of the Browning M1920 anyway.

Protection

Three armored plates were bolted along the sides, riveted, while the wood itself, a glued composite of Pine and Mahogany was both resistant anf flexible, offering a further protection layer. The plates themselves were only 0.2 in thick, about 5 mm. Overhad protection was inexistant in case of shrapnel and mortar fire of any kind, soldiers and crew only had their helmets. The rea and side of the bopat were unprotected, but they were never suppose to turn over but disengage while backing by propeller, staying always forward until out of range. For this, and the final approach, the whole ramp, far larger than the former LCP(R) was made in metal, with the same 5 mm sheating forward, added to a sloped primastic structure, bot for rigidity, anchoring in the sand, and artificially increasing thickness. This ramp had “windows”, empty section at the lower level for the driver and MG-gunners.

Payload

Detailed blueprint, cutout and elevation by BuShips “36 FT Landing Craft, LCVP, inboard profile, construction plan with engine details.”, seemingly dated from July, 16, 1952?. The plans shows notably the filler blocks alongside the hull for buoyancy.

The cargo well measured 17ft 3in long, 7ft 10in at its maximum width and 5ft high. At the bottom there were two “tracks” with fixing bars and strapping hooks in order to solidly immobilize a Jeep, the main designed vehicle load. The Willy Jeep indeed had a front axle track of 47 inches (1,19m). It could carry on paper any vehicle not heavier than three tons. The Dodge C-51/52 was 2 ton 520 (5,550 Ibs) fully loaded, and thus, was compatible, but its track was wider at 62 in (1,56 cm) at the rear. The ramp width was around 96 inches, so it had room to spare. There were the most common types. A small truck such as the G506 already was 8,215 lb (3,726 kg) (empty), so way above.

As for the lenght, it was sufficient on paper to carry also a trailer behind a jeep, but unattached, with it’s hooking leg above the rear compartment to gain space. In theory, the LCVP could also load any artillery piece not heavier than three tonnes; giving it some leeway: It could acommodate the 2,495 lb (1,130 kg) 105 mm Howitzer M3, the 4,980 lb (2,260 kg) M101 105 mm Howitzer, the 653 kg (1,439 lbs) M8 mountain Pack howitzer for example, or a Bofors AA. Nevertheless, they were rarely used for fire support on the beach, but as a second wave payload. There were in 1944 plenty of support conversions of landing crafts, from artillery, rocket, AA support and command.

The usual practice was to sent infantry first, fully equipped for at least 48h of fighting unsupported, to recoignise the terrain an pass on info the naval artillery, use mortars and bangalores to blast its way through the beach and secure a beachhead enough for a second wave to come, either infantry reinforcement, or indeed artillery and ammo supplies, aso repatriating wounded if a beach sector was safe enough.

Production

About Higgin’s dogged confidence and production

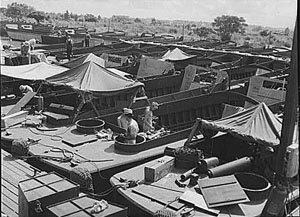

After some testing, the new landing craft was accepted for production as the Land Craft Vehicle, Personnel, soon abbreviated like previous small boats as the LCVP. Higgins main facility was considerably enlarged to meet the demand, making also massive paking spaces in the swampy area of “Vachon bay”.

Eventually he would employ more than 30,000 integrated workforce in New Orleans, including blacks and women, still uncommon practice in 1940. He received in 1942 as numbers piled up, the help of other American factories, to eventually reach the amazing figure of 23,398 LCVPs in 1945, the largest boat production ever seen in history. His construction methods were so efficient in 1945 he could turn out an entire boat in a week, and dozens were produced in finely tuned streamlined areas, each responsible for a construction stage. Being much simpler and quicky to built than PT-Boats, they had a much faster process.

Production would go on from then, with a grand total between 23,358 and 22,492 depending of the sources. In fact by 1944, the LCVP accounted for 92% of the entire US Navy inventory of ships and boats. It should be noticed that Andrew A. Higgins, described as “a fire-tempered Irishman who drank whiskey like a fish” was already a colorful figure in Louisiana, and positive there would be a need among for the U.S. Navy small boats, also was sure steel would soon be in short supply and he could play his card.

Higgins in fact even bought the entire 1939 crop of mahogany coming from the Philippines, storing it on his own accord in prevision. His expectations proved right, and he even applied in Naval design to reach a more official position and secured his bids. Confonted with the USN bureaucracy he complained time and again that the Navy “doesn’t know one damn thing about small boats”. It took the whole year of 1940 and 1941 for Higgins to the administration of the need for small wooden boats until with the confidence built with the USMC’s LCPs, obtained the well-awaited signing for the LCVP.

The American Auto Industry in Detroit also worked with Higgins Industries in New Orleans as they built the engines for the PT boats (Packard 4M2500 marine engines) or the Detroit Diesel Division for General Motors 6-71 diesel engines modified by Gray Marine Motor Company in Detroit. When they were not available, gasoline powered engines built were used. Other manfacturers of the LCVP included Chamberlain (unknown records), Chris-Craft (8,602), Dodge Boat and Plane (74), Matthews Company (496), Owens Yacht Company (2,150) and Richardson Boat (604) But this included others than the LCVP alone; Also the LCP(L), LCP(R), and LCV for which 1200 were mostly prodced by Chris and Owen.

Production peaked in 1943 with 8027 (only 215 LCVPs delivered by fall 1942) and 1944 with 9290, but fell logically to 5,826 in 1945 for the LCVP alone. However 510 Higgins LCVPs were built monthly for a period of 10.5 months resulting in 5,355 LCVPs built amounting to 12,355, so close to the total 12,500 from most sources and 53% of all of all LCVPs built during the war. It should be added than Higgins also perodced also some hundred 170 and 180-foot Steel FS Coastal Freighters, 335 J Boats, 13036-ft landing crafts for the US Army, as well as 316 barges, 10 tuges, 18 other small boats in addition to the aforementioned vessels.

On 23 July 1944, Higgins employees and U.S Navy personnel boarded an LCVP on Lake Ponchatrain during the celebration for completion of the U.S. Navy’s 10,000th Higgins Boat, through “File No. 631C-13. Subject: Navy’s 10,000th Higgins Boat. Date: Jul 23, 1944.” in New Orleans, Louisiana. Src. Below, stockpiled LCVPs in Vachon and on railcars.

Specifications 1942 |

|

| Dimensions | 36 ft 3 in (11.05 m) x Beam 10 ft 10 in (3.30 m) x Draft 2 ft fwd, 3 ft (0.91 m) aft |

| Displacement | 18,000 lb (8,200 kg) light |

| Crew | 3-4: Coxswain, engineer, bowman, sternman |

| Propulsion | Gray Marine 6-71 Diesel Engine, 225 hp (168 kW) or Hall-Scott gasoline engine, 250 hp (186 kW) |

| Speed | 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h) |

| Range | Range 110 nm (203 km) |

| Armament | 2× .30 cal. (7.62 mm) Browning machine guns |

| Payload | 6,000 lb (2,700 kg) vehicle, 8,100 lb (3,700 kg) cargo, 36 troops |

Variants of the LCVP

“Mad Jack” Churchill leaving a landing British LCP(L).

In WW2, there was no known conversion of the LCVP at least on the US side. The British forces received a thje LCP(L) and declined their own version, and later the LCP(R) which they derived their own LCA, but they would receive a total of 413 LCP(R) transferred under Lend-Lease and later only around 700 LCVPs in 1943. Most were used in Operation Overlord. The LCA, very close to the LCVP was declined into the support vessel LCS(M) Mk.I. See also British landing Crafts; The British RN retained the name of LCVP for a new wave of landing crafts in trhe 1960s, the Mk.2, 4 and 5 which participated in the Falklands war. The last were still operational in 2012.

Geheese pulling an LCVP on a beach in 1957

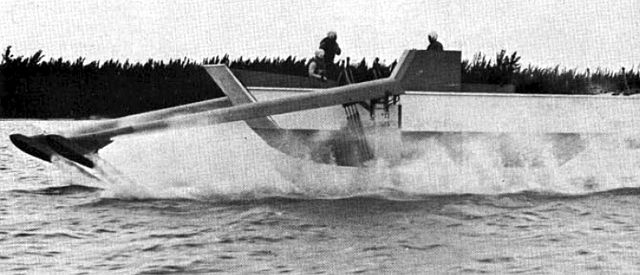

Halobates experimental hydrofoil circa 1958

_hydrokeel_landing_craft_c1961.jpg)

LCVP(K) hydrokeel landing craft tested c1961

_with_hydrofoils_during_tests_in_1962.jpg)

LCVP(H) with hydrofoils during 1962 tests

One of the path of improvement for the huge postwar fleet of LCVPs notably the approach speed. Tests were performed in the late 1950s and 1960s with variopus hovercraft contraptions, including jettosonable versions and powerful engines to reach the desired 40 kts plus speed. The “high lander” had interesting addon foils on the sides which could be lowered at high speeds and a long reshaped ramp bow. It was powered by a twin 275 hp Chrysler powerplant. Instead of wood, the new LCVP(H) had a double skin platic hull, was 40 ft long, 29 wide, 28,000 Ibs. First tests were performed on the 23-ft High Pockets boats in 1952, but the 1959 High Lander was tested until 1962 but not adopted.

As for the experimental LCVP(K) hydrokeel landing craft, it was tested on the Potomac River (USA) in 1961 but could exceed 30 knots. The hydrokeel used the principle of air cushio, trapping air under the keel, and blewing it to pressure using a compressor. Also not adopted as wing in ground experiments. At the time, the USMC started to be interested by more promising Hovercrafts, which gained traction until the first petrol crisis of 1973.

Src/Read More

Books

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1922–1946

The Boat that Won the War – An Illustrated History of the Higgins LCVP, Charles C. Roberts, Jr.

Links

ww2db.com on Andrew Higgins

Higgins on usautoindustryworldwartwo.com

Higgins Industries on nationalww2museum.org

Hydrofoil tests

Hydrofoil tests

Hydrokeel tests

Hydrofoil tests

ww2db.com

On cs.stanford.edu

On globalsecurity.org

cc pics

On historyofwar.org

invent.org

netmarine.net

history.navy.mil

dday-overlord.com

wiki

challengelcvp.com

About D-Day

Higgins on www.nww2m.com

Model kits

Italeri 510006524-1:35 LCVP

LCVP Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel w/Figures 1/72 Heller

Armageddon models: LCVP 1/72

British Model on gaso-line.eu

Videos

Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) (documentary)

LCVP HIGGINS BOAT 1944 U.S. NAVY LANDING CRAFT TRAINING FILM 29784

The Boats That Built Britain – WWII Landing Craft – Part 1

Builders, Heroes & The Boats that Won the War for Us | 2000 (book)

Heller kit review on onthewaymodels.com

Combat records & Legacy

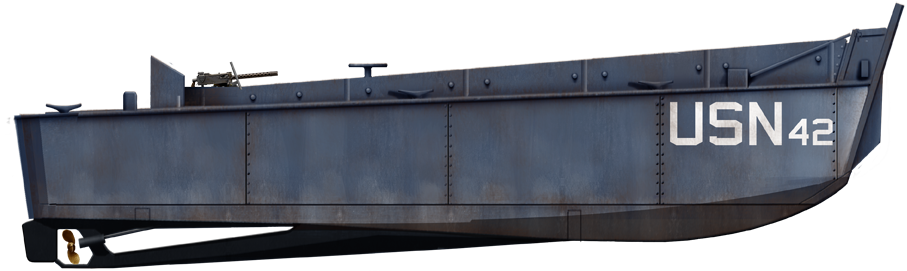

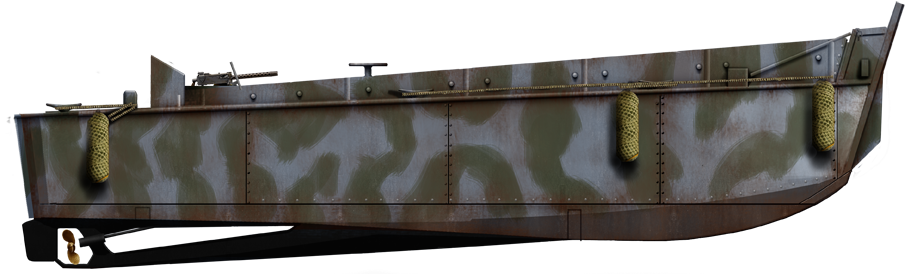

In these profiles the standard livery was the Ocean Gray 5-0 FS35164. The British ones were sometimes camouflaged, as well as some USMC vessels which had some leeway due to their threater of operation.

LCP(R)

Early LCVP from USS Hunter Liggett (APA-14), USMC at Bougainville, Solomons 1st Nov. 1943

Typical mid-production LCVP in Normandy, USS J.T Dickman (APA 13) 6 June 1944 (3 view).

Typical mid-production LCVP in Normandy, USS J.T Dickman (APA 13) 6 June 1944 (3 view).

LCVP with a navy blue livery, Philippines October 1944

LCVP camouflaged used at Iwo Jima, 1945 (photo)

LCVP in British Service 1944

Tactical Use

Troops climbing back a rope net onto their boat. Note their heavy equipment and cold climate jacket. Landing at Attu and Kiska, 1943. Often, the nets were loaded with ballasts and reinforced by transverse wooden beams for stability along the ship’s flank and maintained by soldiered already onboard.

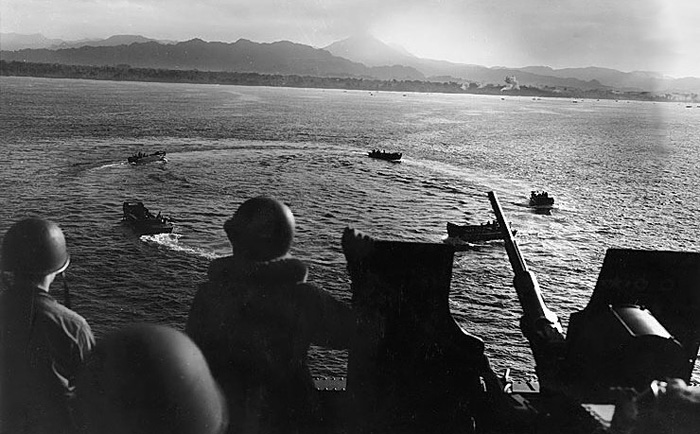

As Operation Torch took place in November 1942, the LCVP was brand new and just getting recenty produced. By that time, below 200 has been shipped by production record, and it’s not even sure how many assault ships carried these. On that path, for deployment, Higgins Boats were typically loaded on Attack Transport Ships (APAs) – see the button link above – which carried troops and/or equipment, plus numerous small boats that acted as shuttles with the beach. The troops were carried all along the journey from the home port to the shores, staying out of range of coastal batteries, so around 30 km for safety but it depends of intel. Some beaches were almost not fortified or only had a few 8-in guns batteries and below.

Thus, when, the standing area was chosen, ships were positioned and anchored in carefully planned locations to ensure proper deployment of large flotillas of landing crafts, with enough room for tem to circle in wating patterns and not interfere with other flotillas; Next, the landing craft would be prepared, with all troops and their supplies on deck since an hour, checking and rechecking equipment and gear. When all was in order and the greenlight given to commence operations, all the landing crafts were put into the water, lowered from davits or from boom cranes, strapped and empty but for the diesel tanks.

Once lowered on the water they were kept as close as the waterline as possible and large nets were thrown along the sides of the vessels in order for the troops to climb into them. This was by far the most preilous and complicated process. Given the state of the sea, the land crafts could have a hard time stying close. That climbin net was rarely deposed inside them, but in most case just layed alongside the hull in order not to encountering harsh moves. If a sailor fell, there were chances he would either drawn due to his heavy equipment carried, or be crushed between the 12 tonnes LCVP and the 9,000 tons APA hull.

Bantam Jeep being lowered into an LCVP at New River, NC August 1941.

There were actually losses of that kind at any and each of the transboarding phases, but statistics aside they were considered always acceptable, that is until the concept of LSD rushed in by 1944. But that’s another story. The latter were rare and so until Okinaway, 90% of the troops landed used that system. The British devised heavy duty davits allowing to lower fully loaded landing crafts and the US followed suite on their 1944 APDs.

When all troops were aboard, rarely reaching the nominal 36, the landing crafts would then leave the mothership and gather to the circling pattern formation that allowed all the small boats to join in before order was given by a general coordinator (each LCVP has a driver/commander with a helmet and radio contact), to rush forward to the beach as cruise speed at first, and when entering the dangerous area, a few miles of the beach, to full power.

Wave waiting circle pattern before rush hour.

Then started the “mad mile” in which all of these landing crafts were targeted sucessively by all calibers, until entering mortar and machin-gun range, basically 500 m from beaching, depending on the beach configureation, tide and other parameters. For all that distance, the LCVPs ensured a good all-around protection to it’s occupants, at least for MG fire as its ramp was immune to small arms fire as the side plating. For mortar shrapnel that was another affair. Soldiers generally seated themselves inside when fire was too intense, reducing their vulnerable height and counting on their helmets.

And then the first wave crashed onto the beach. By coming together this alleviated the risk of being picked peacemeale by enemy fire. Having a lot of troops on shore together also multiplied targets and improved the chances of the ensemble to survive during their own foot “mad dash” until finding protection somewhere.

A well-coordinated wave approaching from the beach of Lingayen Gulf, October 1944

When beaching, the MG gunners would generally generously pepper all the fire sources they could spot on the enemy line, but the drivers generally tried to disengage at that point, to avvoiud needlessly exposing themselves and rush back to the assault transports to carry reinforcements and supplies, a process that could take more than an hour. Responsability fell onto the shoulders of the men on the beach to somewhat secure a first foothold, by default of a beachhead which was reached when all frontline defences were silenced.

Ideally alongside the LCVPs other “small boats” rushed forward with support: Some were direct artillery support vessels, others were larger LCMs and carried tanks. Despite the losses, LCVPs would make three or even four rotations during the day, bringing supplies and repatriating injured men in the first day until the beach head was fully secured. The next hours and days, they went on making the same, mostly bringing supplies on shore from the cavernous assault ships’s holds.

LCVPs on deck of an assault ship off Pavuvu Island and “resting place”, August 1944.

Wounded carried inside an LCVP. This top view also showed the interior, driver’s post and engine. Unknown location, but the LCVP next to it (top) seems to shows a camouflage and the one on the first plans looks also as it was camouflaged (lower right corner).

WW2 Operational History

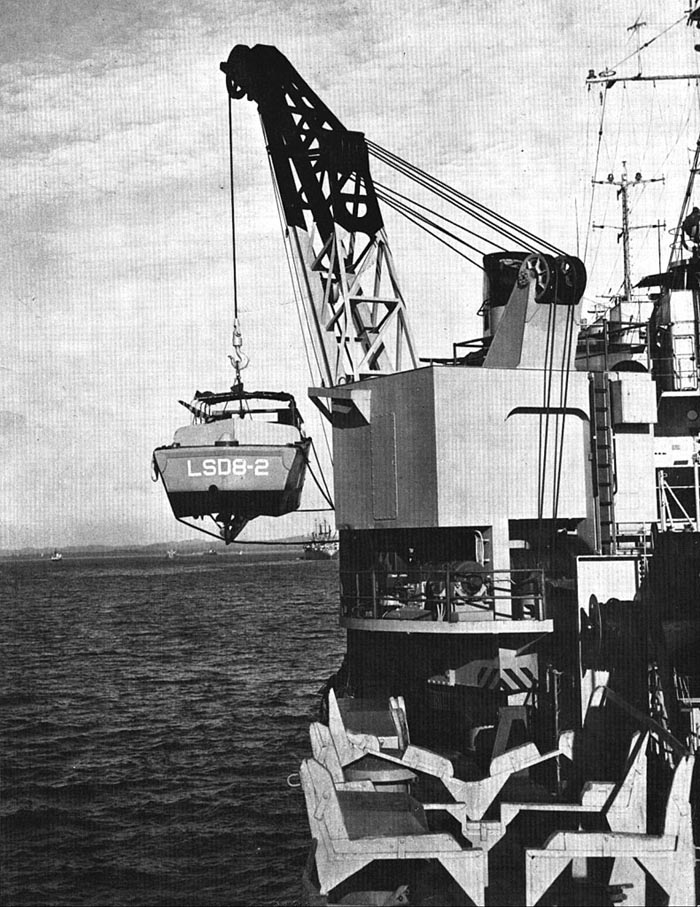

The landing of Attu and Kiska, LCVPs carried on deck pulled over side with cranes. They were often those of the second wave, as it took more time. The davits boats were quicker to put at sea.

23,000 LCVPs were built and the Higgins Boat participated in nearly every significant amphibious landing made by US forces throughout the war. In the European Theater, LCVPs were integral parts of the landing strategies in North Africa (Operation Torch), Sicily (Husky), Salerno and Anzio (the Italian Campaign), Normandy (Operation Overlord), southern France (Operation Dragoon) whereas in the Pacific, they saw action in the Solomons from late 1942, at Tarawa, Leyte and Luzon in the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Riverine operations included some in the Netherlands and of course, the Crossing of the Rhine in the winter of 1945. In the Pacific, they were used for the Guadalcanal Campaign, Battle of Tarawa, Battle for Iwo Jima, and the Okinawa Campaign.

LCVPs in the background. After the landings in Leyte, speech of General Mc Arthur (center) to the troops.

1,100 LCVPs have been used in all for Overlord on Tuesday, June 6, 1944, the greatest concentration before Okinawa. 1,089 were available just for Utah and Omaha, meaning Britush use was farily limited. 26 were lost at Utah, 55 at Omaha, high by naval standards but sustainable. Soldiers in most case a LCVP was hit by a shell or mortar grenade were able to escape from a sinking LCVP, but all payload and vehicles were lost. The high tides in Normmandy meant most could not disengaged when beached and stayed on the beach, providing some shelter points for medical unit in some cases.

French Foreign Legion making an exercize landing in North Africa, march 1944, in preparation for Italian Operations, the landing on Corsica and Anvil Dragoon.

LVCPs in Korea

LCVP bucks in the well of USS Catamount (LSD-17) during a mine-clearance operations of Chinnampo, North Korea, November 1950

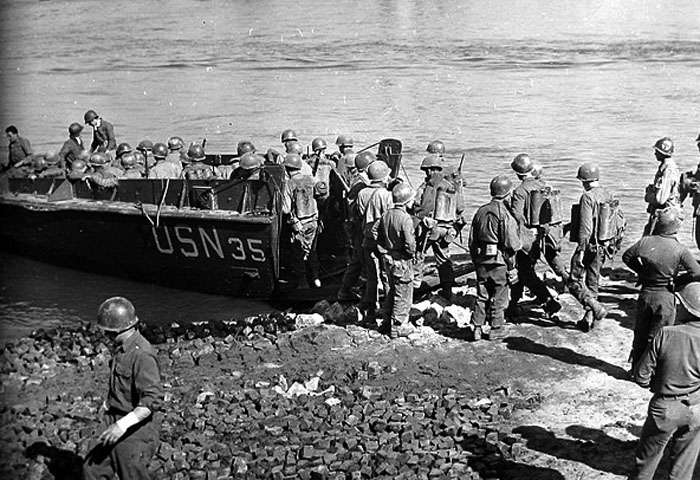

LCVPs Carrying scaling ladders by US Marines to the seawall at Inchon, 1950

USS White Marsh (LSD-8) lowers an LCVP in 1955

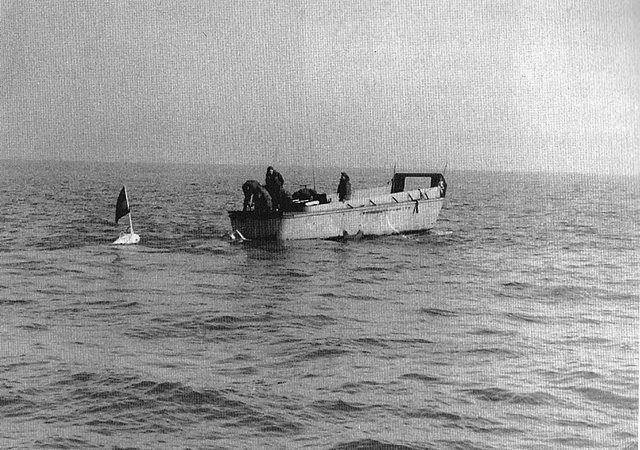

LCVP off Chinnampo 1955

The LCVP saw service also in Korea. Their greatest operation was the the United Nations landings at Inchon (Operation Chromite), South Korea in September 1950. There, some LCVPs carried ladder to climb the port’s defensive wall. The same assault transports were used as in WW2. No major landing required its use later in this war but some operations in the shores of North Korea. Later they also assisted in the Evacuation of Chinese from Tachen Island off China in 1955. They also took part in Operation Blue Bat, a combined US Army/USMC landing in Lebanon during the July 1958 crisis.

French LCVPs in Indochina

Paired French LCVPs rearmed as gunboats on an unidentified Mekong tributary, 1954.

After the US, France used the LCVP extensively, not only during operations such as Anvil-Dragoon in August 1944, but also in Indochina from 1945 and until 1956. They were particularly used on the mekong river, and modified for the occasion as armoured gunboats, the “dinassault”: Considerably transformed, hull plating doubled with extra armor plates, armored shelter built around the helmsman’s position, armored roof above the tank, plus a shielded 20 mm/70 Mk.II Oerlikon gun installed behind the bow. The ramp was cut down, its height reduced to fire above. From a rustic landing craft, the French made quite a formidable patrol craft.

This customized versions was not without flaws: Her single engine was not always reliable and LCVPs always operated in sections of two, the payload was severely reduced, the draft exceeded one meter in full order, and there were problem with the engine ventilation and exhaust, making it very noisy, and precluded infiltrations.

As it is, this “LCVP Blindé” formed Flotillas in the South, the first operational on March 15, 1946, having up to 30 vessels in 1947, and one in the North, and by the fall of 1950, operating 78 armored LCVPs plus 13 regular ones, for a grand total combined in 1952 of 150 LCVP, of which 120 were armored. Any of these were under orders of a midship or young ensign, active or reserve. Riverine operations were a success, despite the lack of boats to really pêrform a constant presence. These lessons were applied during the US Operations of the 1960s.

LVCPs and sub-versions in Vietnam

LCVP, LCU and LCM of the US Navy Brown Water Navy, on the Cua Viet river, 1967

Vietnamese LCVP on the Mekong, 1973

USS Askari (ARL-30) with converted LCVPs in Vietnam, May 1967.

In all, sixteen LCVPs were transferred from 1961 in Vietnam, alonsgide the same numbers of LCMs. Far more reconditioned from mothballs were sent there until 1965, used for early landings or with the Mobile Riverine Force alonsgide LSMs, PGMs, LSSLs. RPCs were conversions derived from LCVPs, but criticized as being slow, prone to mines blast with their welded-steel hulls and poorly armed. According to various sources 27 or 34 (Conways) were built in 1964. Monitors were rather converted from the larger LCM(6). LCVP were rare at this stage and sidelined to auxiliary roles after 1965. After more than 20 years, their wooden frame was generally in poor condition. The bulk of riverine operations was made by nimble plastic-built PBRs in the later phase of the war, until 1973.

Surviving examples

A veteran od D-Day revisiting a static example at Utah Beach in the 1990s.

Only a few Higgins boats survived, and many were modified with a quite substantial was in the cold war. A replica Higgins Boat was in fact even built in the 1990s using original specifications from Higgins, now displayed at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. A second original LCVP is restorated at the same place.

One original boat was rediscovered at Vierville-sur-Mer in Normandy, and now professionally restored by the North Carolina Maritime Museum, First Division Museum, Cantigny Park, Wheaton, Illinois. Overlord Research, LLC (West Virginia) founded in 2002. Its role has been to collect and restore this WW2 memorablia and artifacts, returning them back to the United States. It was purchased from its French owners, transported to Hughes Marine Service in Chidham, England for initial evaluation and restoration, then acquired and shipped to the First Division Museum via Beaufort, Illinois.

Another one was also located by Overlord Research, LLC on the Isle of Wight, also under restoration at Redstone Arsenal, Alabama for the United States Army Center of Military History, intnded to be displayed at the National Museum of the United States Army, constructed at Fort Belvoir in Virginia. Another was recuperated in a farmyard, in Isigny sur Mer in 2008 and endeed on the car park at the German Headquarters,Grandcamp-Maisy battery 1.5 miles from Omaha Beach. Another is on display at the D-Day Museum in Portsmouth, England.

LCVP used for flood emergency evecuations and relief at Clastskania, Oregon june 2, 1948

Another is restored in France, constructed in 1942 and used in North Africa and Italy by Free French troops. It is restored to full operation in order to participate in some future big events. Another one located in Port St. Lucie, Florida is also awaiting restoration. There is a LCP(L) at the Military Museum Of Texas in Houston, fully restored. Another from USS Cambria survived seven Pacific Theatre invasions ans is now showcased at the Motts Military Museum in Groveport, Columbus, Ohio, with its Coxswain, Sam Belfiore, awarded the Silver Star. Another was located in poor condition layong at King Edward Point, South Georgia in an Antarctic environment. Their wooden structure had a hard ttime surviving 80 years while being exposed to the elements.

Gallery

USS_Weber_APD-75_in_reserve_circa_in_the_1950s

LCVPs-ItalySalernoInvasion1943

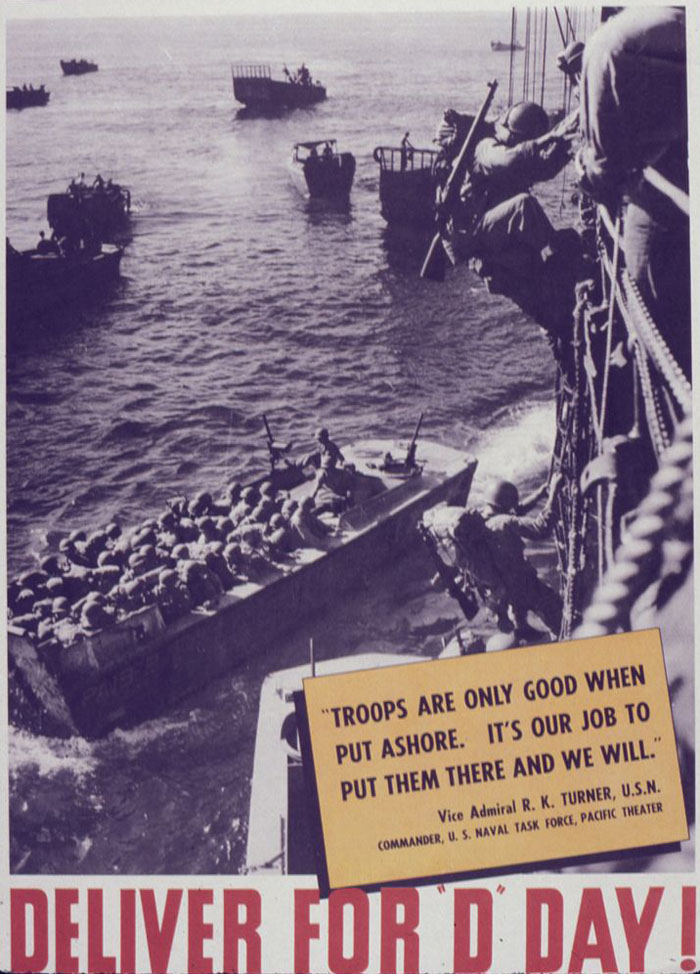

Deliver_for_D_Day 1944 propaganda poster (NARA)

Attu_landing_craft_on_beach_1943

Landing_barges_loaded_with_troops_sweep_toward_the_beaches_of_Leyte_Island

Coast_Guard_manned_LCVPs_Empress_Augusta

Australian_troops_storm_ashore_in_first_assault_Balikpapan_Borneo

LCVP close to Leyte Beach, October 1944

US Coast Guard personal driving an LCVP from USS Joseph Dickman, Utah Beach, 6 June 1944

LCVPs landing in Guadalcanal, Solomons

St Tropez area Wounded soldiers evacuated LCVPs transfer onto hospital ship 15 August 1944

LCVPs on Cavalaire invasion beach (Anvil Dragoon) 15 August 1944

Wounded men in an an LCVP on a beach of France, with a Coast Guard coxswain to a Coast Guard manned assault transport

Evacuation of wounded men into Higgins boats, 7th Army, 3rd Division, 15 August 1944

US LCVPs at Gela beach, Sicily, in July 1943

USS-Audubon_Lowering-an-LCVP-from-port-davit_Feb-1945

Attu_Invasion

LCVP_landing_craft_put_troops_ashore_on_Omaha_Beach

LCVP_crossing_the_Rhine

FrenchFL-exercise-Nafrica-amphibious_exercise_P-39_close_air_support-19March44

LCVP-Leaving-bikini

LCVP-Unloading_at_Gela_during_the_Sicily_Invasion

Rhine_Crossing-_equipment_to_be_ferried_across_the_Rhine_River_is_loaded_on_US_Navy_LCVPs

Seabees_used_Marston_Matting_approaches_for_loading_LCVP_craft_at_loading_points_to_take_Pattons_army_across_the_Rhine

Rhine_Crossing_3rd_Army_flatbed_truck_carrying_a_Navy_LCVP

Rhine_Crossing_U.S_Third_Army_LCVP

Into_the_Jaws_of_Death_LCVP-6June44

Troops_wade_ashore_at_Omaha_Beach_from_a_LCVP_landing_craft

Troops_and_crew_of_LCVP_off_the_Normandy_beaches_6_June_1944

LCVP-Approaching_Omaha

LCVP-1944_NormandyLST_clean

LCVPs-TanapagHarborSaipan3August1944_US_National_Archives_Photo

Lopez_scaling_seawall-LCV

LCVP_and_vehicles_on_Omaha_Beach_6_June_1944

3d_Division_Marines_fan_out

LCVPs_shoving_off_with_liberty_parties_at_the_Pearl_Harbor_Naval_Shipyard_Hawaii_July_1945

Tractor_pulls_SBD_Dautless_on_Espiritu_Santo_LCVPs-c1942

LCVP-Supplies_piled_up_on_the_beach_at_Guadalcanal_1942

USS_Mindanao_ARG-3_damaged_by_explosion_of_USS_Mount_Hood__Seeadler_Harbor_10_November_1944

163rdInfRegt_hit_beach_from_Higgins_boat_invason_Wadke_Island_DutchNewGuinea_May18-1944

LCVPs-IowJima

French_Foreign_Legion_troops_landing_on_a_North_African_beach_exercises_march_1944

American_troops_leap_forward_to_storm_a_North_African_beach

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

There is a preserved/not restored one (still in the original paint) at the Nebraska National Guard Museum in Seward. PA 31-17

Thanks for the info !