US Navy (1942-46) Light Cruisers: USS Cleveland, Columbia, Montpelier, Denver, Amsterdam, Santa Fe, Tallahassee, Birmingham, Mobile, Vincennes, Pasadena, Springfield, Topeka, New Haven, Huntington, Dayton, Wilmington, Biloxi, Houston, Providence, Manchester, Buffalo, Fargo, Vicksburg, Duluth, Newark, Miami, Astoria, Oklahoma City, Little Rock, Galveston, Youngstown, Buffalo, Newark, Amsterdam, Portsmouth, Wilkes-Barre, Atlanta, Dayton

US Navy (1942-46) Light Cruisers: USS Cleveland, Columbia, Montpelier, Denver, Amsterdam, Santa Fe, Tallahassee, Birmingham, Mobile, Vincennes, Pasadena, Springfield, Topeka, New Haven, Huntington, Dayton, Wilmington, Biloxi, Houston, Providence, Manchester, Buffalo, Fargo, Vicksburg, Duluth, Newark, Miami, Astoria, Oklahoma City, Little Rock, Galveston, Youngstown, Buffalo, Newark, Amsterdam, Portsmouth, Wilkes-Barre, Atlanta, DaytonThe WW2 standard USN light cruisers

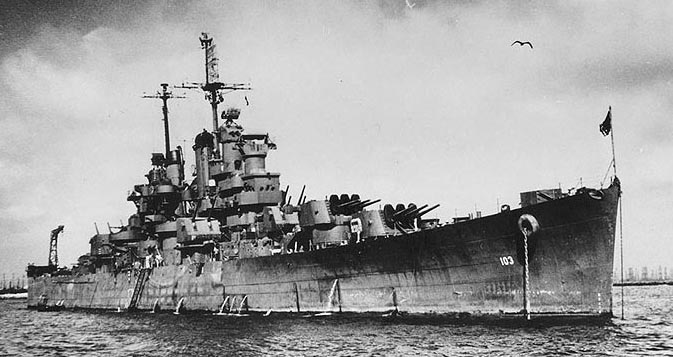

The WW2 Cleveland-class light cruisers formed the most prolific serie in history*. With 29 ships completed out of 52 keels laid down, 13 cancellations and 10 conversion to fast aircraft carriers (USS Independence class). This was the great new standard for light cruisers, with a treaty-free tonnage of 12,000 tonnes standard. Among these two were completed on a different design, the USS Fargo and the USS Huntington, leading to an interesting sub-class designed in 1942 to improve the AA arc of fire with single funnel and revised superstructure.

They derived from the Brooklyn class, but their limited size and the need to eliminate extra weight made their protection insufficient, which were corrected on the new design. The original project was first defined in 1939, including 5 brand new semi-automated 6-in twin turrets, still in development. However as they were never ready on time, the Cleveland reverted on the proven triple turret design of the Booklyn class. The Clevelands were started between the 1st July 1940 and 20 February 1944, launched between 1st November 1941 and 22 March 1945. Some were completed too late: USS Manchester, Galveston, Fargo and Huntington participated in the Korean war instead. This large hulls reservoir led to the cold war conversion into hybrid missile cruisers. If some were discarded in the 1960s, many survived until 1970-78 while USS Little Rock has been preserved as a museum ship.

*with the arguable exception of the 28 British WWI C class cruisers, which diverged much in dimensions and caracteristics from 1912 to 1919. More Cleveland hulls were laid down anyway and they were more standardized.

Design development

If the gigantic industrial effort asked to bolster the Navy started in practice in December 1941, already after September 1939 prospects for a new cruisers started when the treaties were no longer a priority. Freed from cruiser tonnage caps, American engineers were now tasked to answer the Admiralty requests for a new light cruiser with a much satisfying design, for armament, speed, range and protection. It was inevitable these tonnage limits would slip up, both for heavy and light cruisers. And thus, the path chosen for the Brooklyn class (1936), the result of the London treaty, enabled a new “category” of heavy cruisers, capped both to the 6-in caliber and 10,000 tonnes. Soon after their construction was finalized oother light cruisers were considered as the USN was increasingly frustrated by the slow rate of fire of their standard 8-in gun (3 vs. 10 rpm). In 1935 however, the US signed the second London navaly treaty, even more radical as it capped new cruisers to 8,000 tons and 6.1-inch (155 mm) guns. An improved repeat of the Brooklyns was no longer possible, so the admiralty turned towards a new breed of light cruisers designed specifically for AA defense, as already tested by the British.

This resulted in the Atlanta class. However in 1937 as the international situation degraded fast in Asia, the US admiralty re-opened the case of 10,000 tonnes and more light cruisers.

In a general way, anti-aircraft concerns took a large part in some consifderations about the new design. The US Navy indeed started to train its AA gunners with target drones, simulating both dive and torpedo bombers. The simulations showed fire control directors associated with computers were the way forward to reach the required accuracy at greater speeds. It was consider in a future conflict the density of incoming aircraft attack would overwhelm classic defenses. Mechanical computers however at that time weighted up to 10 tons so they needed to be located below decks, also allowing to better protect them. In fact this even was under the reality that emerged during WW2: By 1944, all calibers above 20mm gained remote powered dedicated fire control, and radar aiming.

1938 Initial BuShips proposals

At first to meet the new treaty limits, and still provide much needed cruisers for scouting and fleet screening in 1938, BuShips proposed in June that year a 8,000 ton, 6 inch gun cruiser design with eight to nine main guns. It was at first named Cleveland, and designated CL-55. This intermediate cruiser main battery was not the same as the Brooklyn, but much lighter, a realistic move on the given tonnage. However the admiralty was not satisfied with it. Further developments went on slowly. This “weak” design was, needless to say, disliked by all members of the design group, but submitted to the board anyway. Fortunately, the “scout/screen” design took another path (leading to the Atlanta) while the light cruiser role was reactivated in March 1939. Rapid progress was made based on this new direction, and by May 1939 the design evolved much as the new ship was now to be armed with ten 6in/47 guns in twin dual purpose turrets but also a single aircraft catapult, and two banks of triple torpedo tubes. It also had a light anti-aircraft battery of just five quad 1.1 inch (28 mm) “chicago Piano” mounts.

To keep the design under the 8,000 ton limit the side armor belt was almost symbolic, leaving the ship almost unprotected. Even with this, there was still no room for expected modifications in case of war. From March 1939 already it was decided to retaking the “Brooklyn hull”, already setup for a cruiser 2,000 tons heavier, but gaining considerable development time.

With all these considerations, the bureau of ships (BuShips) started working on this existing hull, to be more precise the St Louis sub-class hull, much improved (USS St Louis, CL-49, launched 15 April 1938), and later settled on the following Helena CL-50. It was chosen as a base for development, leaving time to arbiter about the main and secondary armament as well as AA, and the intended better fire control capabilities that lacked on the previous design. All these discussions went on along 1939, between the board and BuShips as well as the ordnance bureau of the USN. The adoption of the same hull obviously still presented a major problem: It was designed to be light, first designed at a time the Washington limit (10,000 tonnes) prevailed. The Brooklyn eventually ended with all the AA additions made later as top-heavy, a problem basically repeated on the “improved CL49 design” by this choice of the same hull. The main and bigger critic about the Cleveland design was it left very little margin for improvement and instability became a constant problem, imposing sacrifices. The issue was partially solved on the Fargo sub-class, but too late to affect the production.

This process of playing with armament led naturally at first to adopt the same five triple turret design giving the best firepower possoble, with the 6-inch/47-caliber Mark 16 gun. However already the admiralty thought of a new dual-purpose design similar to what the british already worked on, and which ended on the Crown Colony class cruisers. This was on the US ordnance side, the Mark 16DP (“Dual Purpose”) a two-gun configuration, semi-automatic turret, for use against both air and surface targets.

They had (on paper) an individually set elevation and a brand new mounting allowing an elevation up to 78° versus the 40° of the initial model (later improved to 60°). However its development was still ongoing in late 1939, so the admiralty prudently choose to stick with the current Mark 16 already available in numbers, but choosing alter the mounting instead, ensuring faster loading and greater elevation (see later). The Mark 16DP development ended eventually in 1943, and was adopted for the first (and last) time on the Worcester-class cruisers. A triple DP mounting was even proposed to reach the same firepower again, but was cancelled in 1945, its development incomplete.

The basic design included a secondary artillery that did not existed for the Brooklyn/St Louis: Dual purpose 5-in/38 twin turrets, Mark 32 mount. They were a welcome alternative to the former single mount, unprotected Mark 12 used on the Brooklyns, for which they were initially intended, but development time pushed their adoption for later. They would obtain them eventually during wartime overhauls, adding AA and simplifying their superstructure in the process. The adoption of these turrets meant more space was needed for them to traverse without interference. Each of these turrets was 180 inches (4.57 m) wide, thus requiring about 236 inches (6 m) as safety to manage its turns; Multiplied by two (broadside) that was twelve meters/39 feets already, of space eaten on a 66 feets 4 inches beam (20,22 m) thus leaving 46 feets (14 m) available for superstructure. This right away imposed a specific profile with a large battery deck but narrow superstructure.

In August 1939, these discussions were still ongoing, without yet any authorization for constructions. On September 1, 1939 Germany invaded Poland, ending any obligation to all three peacetime naval treaties. Not only for new construction but also tonnages and gunnery limitations altogether. BuShip engineers were now free to realize their unrestricted ship design, pressed on by the admiralty board, fearing the United States might be drawn into the war. All knew from Hawaii to Pennsylvania Avenue, that the US fleet was badly understrength. This sense of emergency led to renounce a major step towards the improvement of the ship: A beamier hull. It was calculated indeed that adding just one meter to the beam (so 22 meters or 72 feets) would help to solve future instability issues and moreover also all modifications made above the deck. However at that stage the design much advanced, and a conversation between BuShip and the board convinced the latter a redesign of the internals would delay for about a year in the best case scenario, the finalization of the design. It was decided to keep the “tight” hull design and concentrate on the superstructures only, while compartimentation was improved. On 2 October 1939 indeed, the Navy ordered a modified version of USS Helena to gain time altogether.

By October 1939 the design study became a modification of the USS Helena (CL-50), with the hull internals reworked, in particular the original arrangement of four boiler rooms forward and two engine rooms aft, which could be disabled by a single torpedo hit, flooding both engine rooms. The Helena design indeed already innovated by having more compartimentation, with two boiler rooms forward and a forward engine room, plus two more boiler rooms and aft engine room. This time even a major flooding would spare at least half the steam or engines. With this in mind, the new CL50 (mod) class had its propulsion plant arrangement revised. Another crucial modification was to renounce one main triple turret. This was to allow two more dual 5″/38 mounts to be added, fore and aft centerline, since there were only two on the broadside.

This new design indeed allowed six dual 5″/38 mounts (so twelve instead of eight single 5″/25 caliber guns). The light armament was settled on the existing, recent 1.1 inch/50 anti-aircraft quad gun mounts, five in all, so just twenty in all. Torpedo tubes were not included as it was realized early on the ships would be top-heavy with any future addition. As the CL-50 with a “rounded transom” type stern, a large hangar and two aircraft catapults would grant a reasonably large aircraft provision for scouting and spottng duties.

1940 Final design

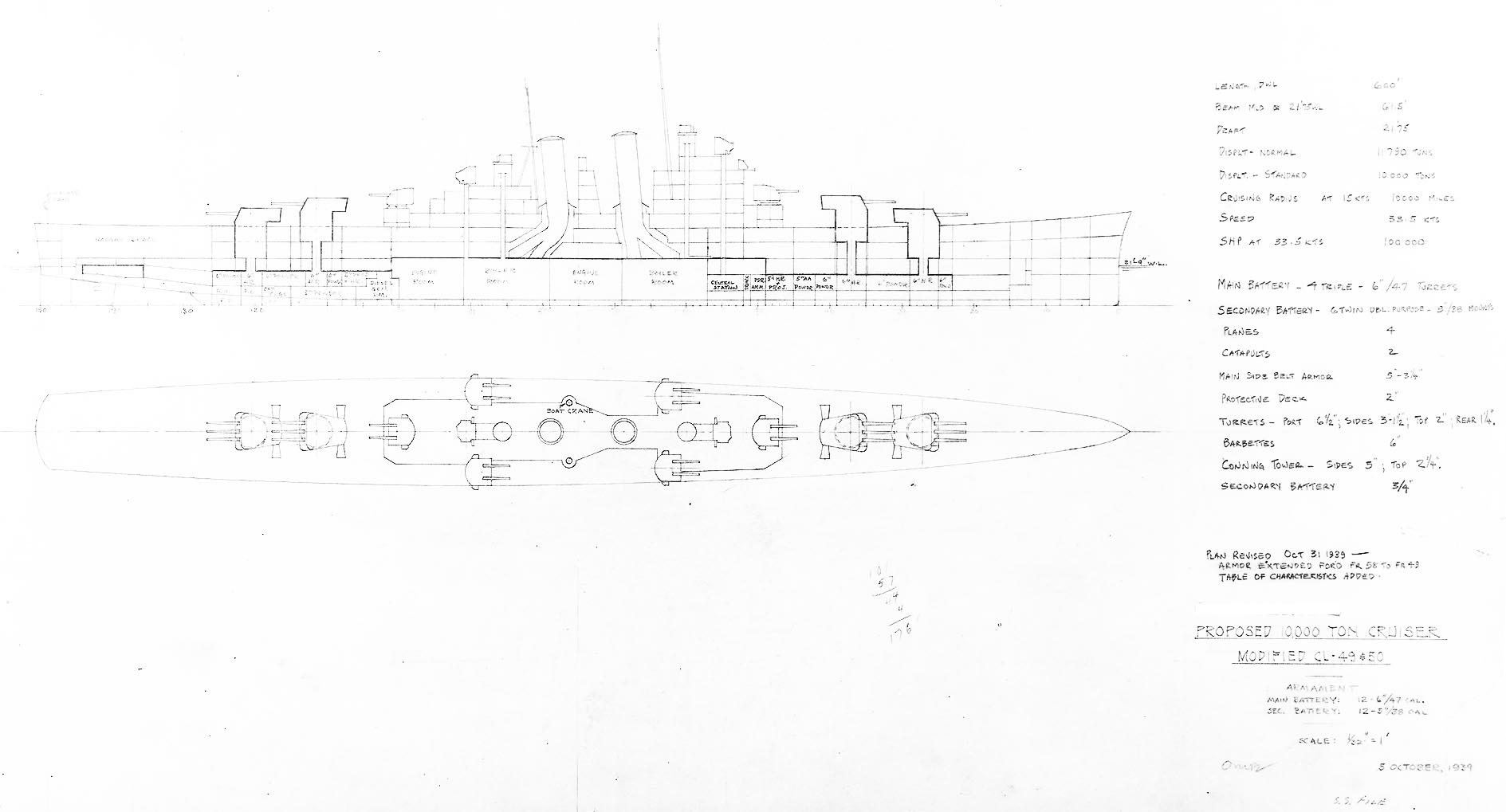

Final BuShip general scheme before acceptance by the admiralty board, modified CL49/50, armor extended version, revised 31 October 1939.

Final design & modifications (1940-41)

Overall in November 1939, the absolute overriding factor was the speed at which these new cruisers could enter service. First off, the triple 6″/47 triple turret was confirmed, the dual 5″/38 was now standardized and fully operational was adopted, while the engineering plant was a repeat of the Brooklyns, less the new compartimenation. Mass production was easier once the design was ensured to be completed in record time. But the new design ran into problems anyway when shortcut were made as studies were now extended into actual working plans. Indeed, any additional armor, AA or and enlarged space for a new powerplant all required lengthening and/or widening the beam, and still, it was precariously close to being unstable. Given the urgency to increase the fleet in March, 1940, the secretary of the navy was notified of the new finalized design as it was, and authorized two ships, to be named USS Cleveland (CL-55) and USS Columbia (CL-56).

Even when the contract design was worke don, they were plans to improve the ship and stability. The initial design was laregly still a Washington-capped pre-war design that was likely to reveal serious shortcomings in wartime. In 1942 it was now clear for all that all ships needed to have greatly improved anti-aircraft battery, but also a more effective protection below the waterline. Both imposed major changes. The contract design was completed in February 1941. They were officially ordered on 23 March 1940, with more to come: CL57 and CL58 on 12 June 1940, CL59 to CL67 in July 1940, CL76-CL88 in September and CL89-94 in October, with more to come in 1941.

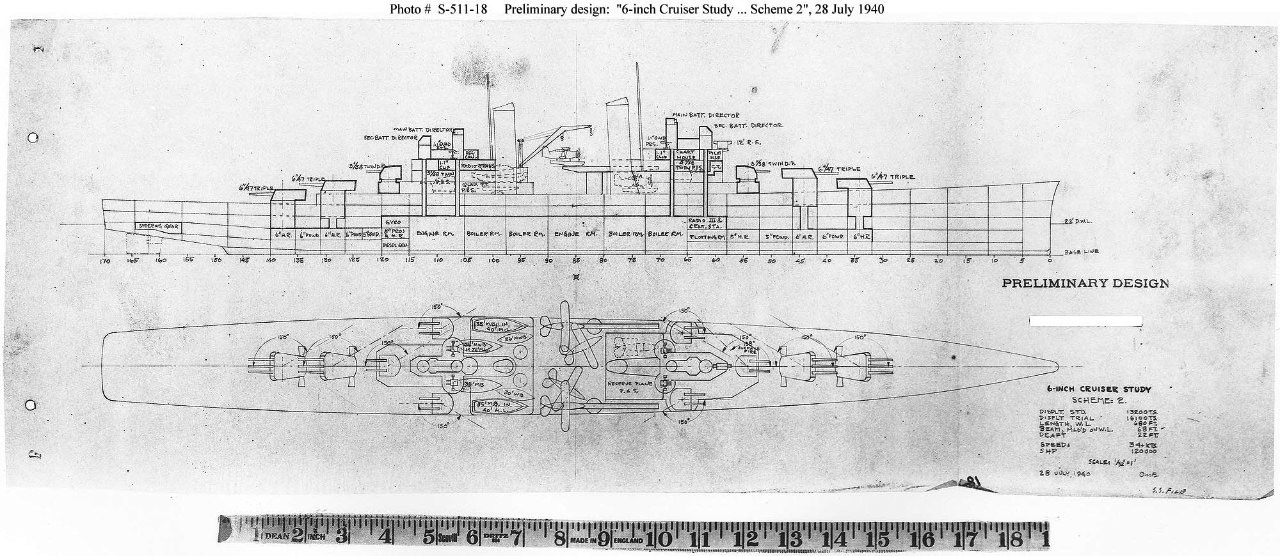

28 July 1940 S-511-18 6-inch Cruiser Study Scheme 2, Preliminary design plan prepared for the General Board. It was an examination of light cruiser designs armed as the Cleveland (CL-55) class, with greater speed and improved protection. It called for a 13,200-ton standard displacement ship, with aircraft facilities relocated amidships to better control weight, improve stability as the after hull was reduced by one deck. It still shows a quadruple torpedo tubes amidships aft of the aircraft catapults. (Naval History and Heritage Command coll.)

At the time, the contractor chosen for both ships, New York Shipbuilding Corporation, proposed improvement of the whole design simply by adding them some tumblehome as French battleships 50 years prior !. This indeed at least on paper improved stability, increased artificially the effectiveness of the belt, now inclined. The hull was also modified: It was initially given a double bottom, and it was altered to a triple bottom. This ensured, in addition to the new engine compartimentation, to give them greater underwater protection.

There was more to come, all as the construction was about to start: Emergency generator power was increased (in case the main powerplant failed). The 5 inch magazine capacity was notably increased of 20%. Of course the anti-aircraft battery was the “hot” topic, and substantial revisions were made. It was worked on as the hulls were already in construction. It was notably discovered that the 1.1 in quad mount was frustratingly slow and inacurate, and design modification went after construction was started, resulting in a “final” design revised entirely to adopt four dual 40 mm Bofors guns, but still 15 quad 1.1 inch machine guns. 50 caliber machine guns were at the time also considered but it was realized they were ineffective against modern planes and were eliminated. These 40 mm guns had no shields to spare weight. In effect, at their first refit in 1942-43, these ships had all their “chicago pianos” removed and replaced by quad 40 mm Bofors and additional 20 mm oerlikon single mounts.

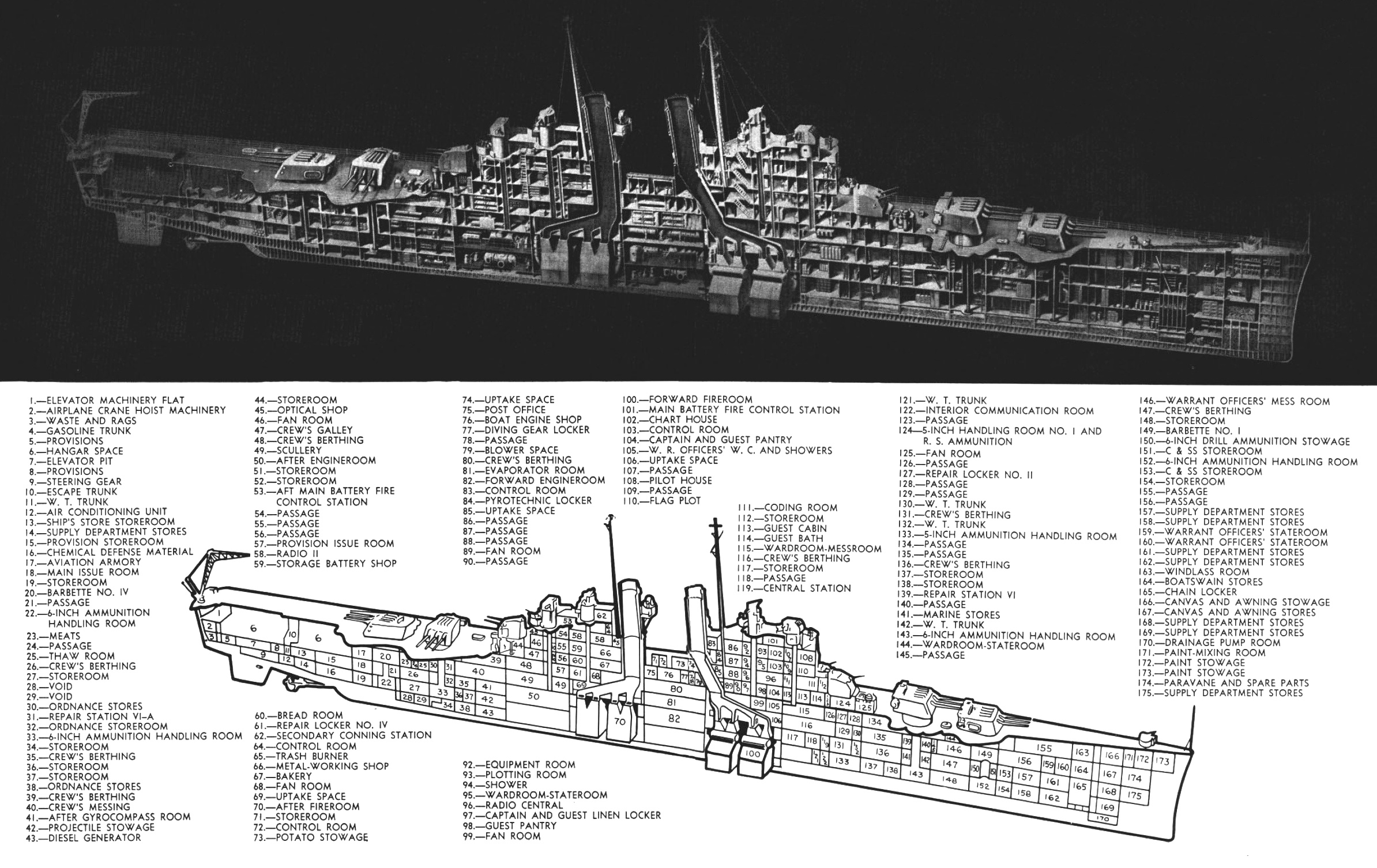

Hull & general caracteristics

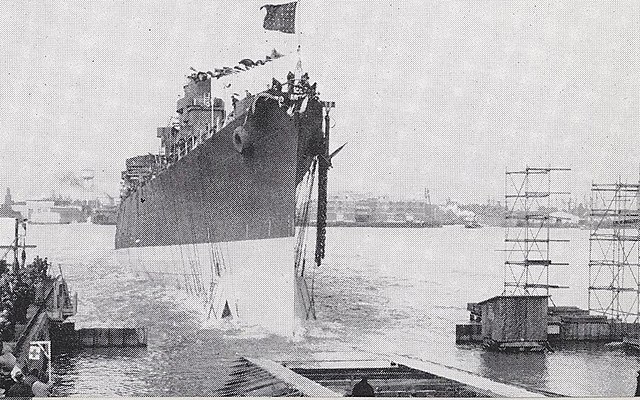

Launch of USS Dayton, NY, 19 March 1944

The new design was given the same general layout as USS Helena, but less a main turret but four more 5in/38 guns. The final design indeed called for four 6in triple turrets, two fore and two aft in superfiring positions. The existing 5in gun positions were retained (two positions on each side of the ship, carried by the side of the main fore and aft superstructures. Two new twin 5in gun mountings were added, one fore and one aft, mounted between the main 6in turrets on a “third level” position reminiscent of the Atlanta class. These raised positions allowed an excellent arc of fire, greater that any other turret on board but still, they weren’t high enough to fire level over the main guns, notably depress to fire on low-flying incoming threats like torpedo bombers.

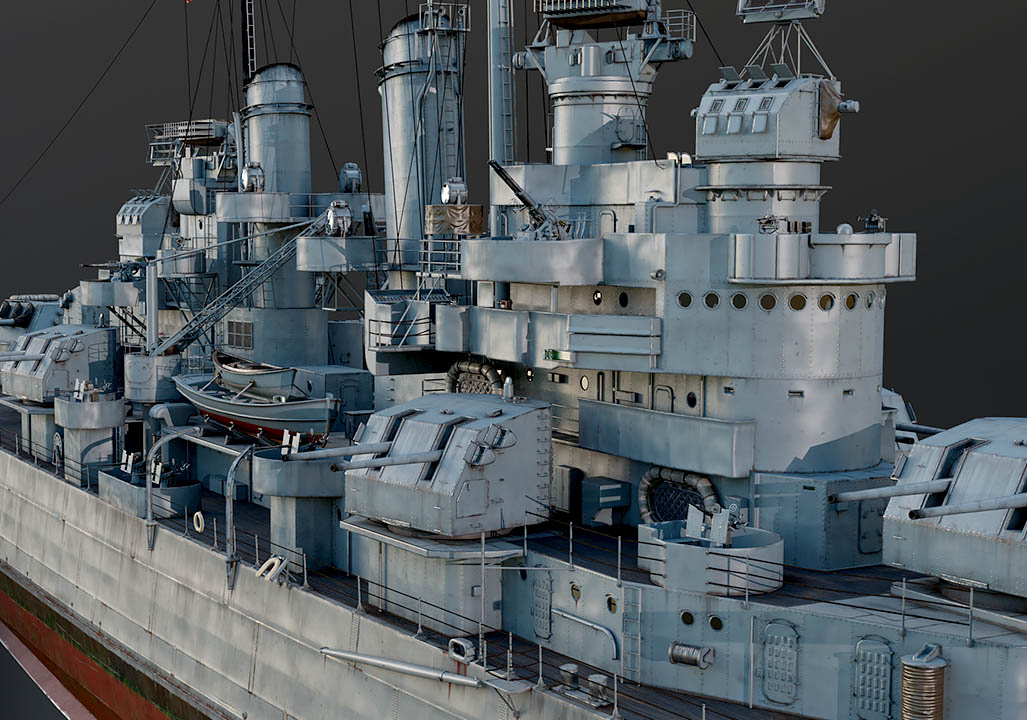

Engineers had the Cleveland class retaining the same hull length but still managed to add 4ft 7in to the beam, even though the hull had the same shape; The new breadth did not changed the internals arrangement that were kept almost unchanged, but mostly allowed to have the hull sloped inwards amidships (so light tumblehome as proposed) and still had the same transom/rounded stern. Well aware of topweight issues, with an artillery already on three level, engineers devised lighter aluminium deckhouses. However wartime shortages redirected this rescources to the air force, and thus construction reverted to heavier steel, stacked on five levels above the deck. This was partly compensated by making lighter metal sheets, hadened when possible by adding a carbon-rich extra layer. But still, the superstructures ended cramped, and the ships gained much extra equipment as the war progressed. First off, new, larger radar aerials were adopted, extra electronics to direct AA fire, plus later the new Bofors AA with their own fire directors, all causing new stability problems.

Increasingly, even dangerously top-heavy the Cleveland had to be manoeuvered with care by commanders, with strict regulations in place and all possible supplies stored as low in the ship as possible. In 1945 one aircraft catapult was removed at the first occasion, and later a rangefinder removed from No.1 turret. Also all ready use AA ammo was to be restricted lower and not brough permanently on the decks, but only in case of attack. Fortunately, none of these cruisers actually topped over and sank, while still retaining good agility when needed.

Protection

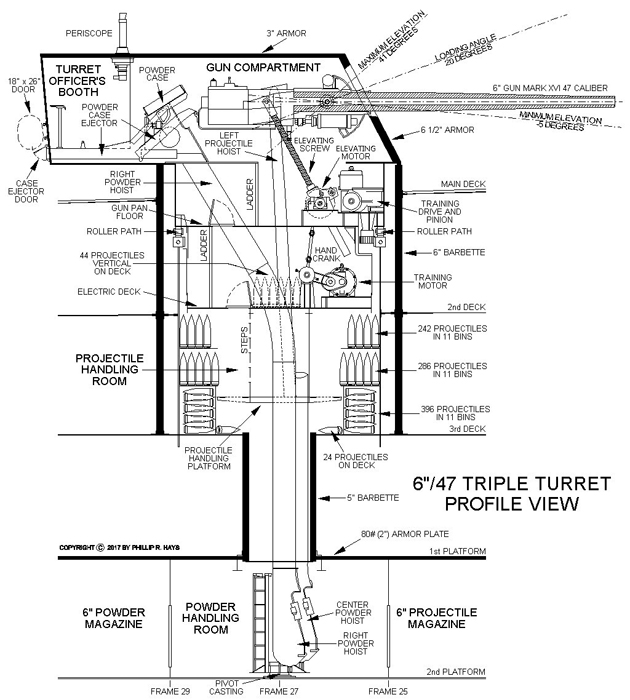

The “poor child” of the design due to pre-existing restructions: The belt was limited to 5 inches (127 mm) in the citadel section, between the outermost barbettes, and down to 3.25 inches (83 mm) fore and aft and down to 1 inch or less upt to the ends. The main armored deck was just 2 in (51 mm) thick, with a secondary, lesser armored deck below it and high tensile strays over the magazines and rudder mechanism (added later during refits). The citadel was closed by bulkheads 5 in (130 mm) thick fore and aft. The turrets were probably the best protected parts of these ships, with a 6.50 in (165 mm) angled, sloped front part (artificially, this went to perhaps 180 mm). The turret sides were like the roof, protected by 3 inches plating (76 mm) and the back was down to 1.5 in (38 mm).

The barbettes below were 6 in thick above the armored deck (150 mm). The forward only conning tower had walls of 5 in (127 mm) thick and a 2.25 inches (57mm) roof. How it compared to the Brooklyns ? The turrets were less well protected on the latter, but they had over the machinery a 5 in (127 mm) doubled by a 0.625-inch (16 mm) STS plate and over the Magazines a 2 in (51 mm) plate added to a 0.625-inch STS plate. The CT and barbettes were the same, the rest was really comparable.

Powerplant

It consisted in a repeat of the Brooklyn class powerplant, four shafts connected to four geared steam turbines fed by four Babcock & Wilcox boilers for a total output of 100,000 shp (75,000 kW), whereas the Brooklyn had a smaller, earlier boiler model, so eight in all. Both cruiser types reached the same output, for the same top speed at 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) for the Brooklyns, but not the same range exactly, 8,640 nmi (16,000 km; 9,940 mi) at 15 knots for the Cleveland versus 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) for the Brooklyns. As said before, the internal compartimentation for the engine rooms and boilers were derived from USS Henela (CL50) and slightly improved, with a forward boiler room, followed by the forward engine room, the aft boiler room and the after engine room respectively. It was again reworked on the late subclass Fargo, with all exhausts ducted into a single funnel.

Armament

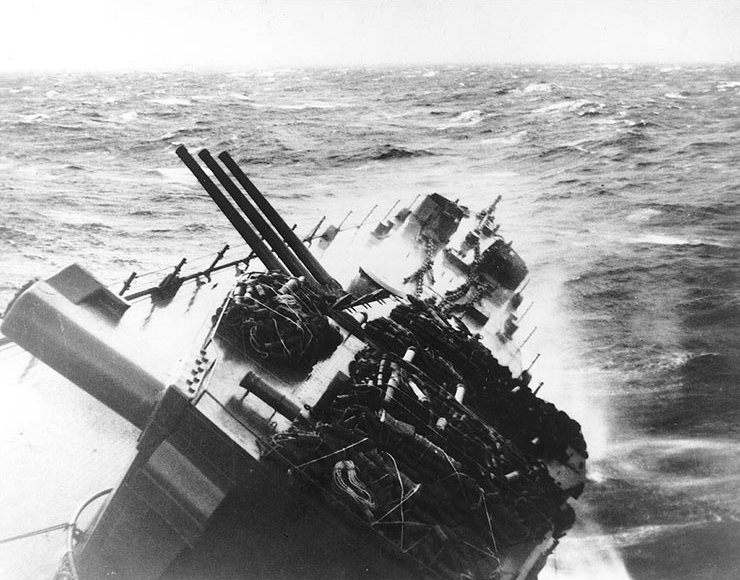

In 1942 as completed, the first Cleveland class cruisers were armed with four triple 6″/47 caliber Mark 16 guns, six dual 5″/38 caliber guns, and four triple 28 mm AA. TTs were also eliminated that this stage. However they were soon rearmed, after sea trials or the first refit, by two quad Bofors 40 mm guns and two dual ones, plus up to twenty single Oerlikon 20 mm cannons. Compared to the Brooklyns, they lost a main turrets but gained much better secondary guns as well as much better FCS (formerly 5″/25 caliber guns, and four dual 5″/38 caliber guns on St. Louis and Helena). At the end of the war, from USS Vicksburg (CL-86, June 1944) this was increased to four quad Bofors 40 mm guns and six dual Bofors 40 mm guns, while the lighter Oerlikon 20 mm cannons were halved. On USS Fargo and Huntington, the completely reworked superstructure allowed an increase of the arc of fire for all secondaries and Bofors, and perhaps sixteen 20 mm guns.

6-in Mark 16 guns

These guns were common to the Brooklyn and Cleveland class, Developed from earlier experiments with old 6″/50 (15.2 cm) Mark 8 guns. The new design incorporated a separate, semi-fixed ammunition while it was tailored to fire tne new “super heavy” AP 6-in shell which had almost double the penetration performance compared to the old Omaha class. The barrels were monobloc autofretted, with their liner secured to the housing, by a bayonet joint. Mod 1 had a tapered liner. They also used a semi-automatic vertical sliding breech block with a 0.5 in ring attachment at the muzzle. Performances with the “super heavy” AP Mark 35 Mods 11 was 26,118 yards (23,881 m) at 47 degrees, as the elevation was ported to 60°. Accuracy was so poor beyond 47° the guns were only used for coastal shelling. The barrel life was between 750 and 1,050 rounds, but each gun was “only” provided with 800 rounds. Their high rate of fire proved a blssing in ship to ship engagements. These guns also fire the HC Mark 34 Mods 1-7 and Illumination rounds Mark 32 and 38 for night battle.

5-in/38 Mark 32 guns

The unquestionably finest Dual Purpose gun of World War II, there in six twin turrets with independent cradles. The were hand-loaded but power-rammed, which procured high rate of fire and with loading at any angle. The shell became proximity-fuzed AA from 1943, with a much greater efficience.

AA guns

-Initially five quad 1.1 in AA guns (28 mm).

-In 1941 BuOrd (The burea of Ordnance) wanted to replace all of these quad 1.1 inch guns with the new licence-built 40 mm Bofors, in dual mounts since they weighed about the same. However the decision was overruled by the admiralty, ordering to replace them with quad mounts for increased firepower. Thos only added to the misery of these top-weight vessels and was only combated by an increase of much lighter Oerlikons.

Note: The 1.1, Bofors 40mm and Oerlikon 20mm will be seen in the tech section.

Fire control systems

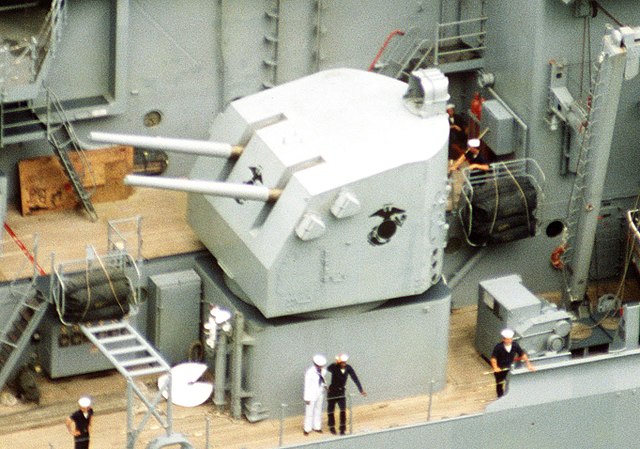

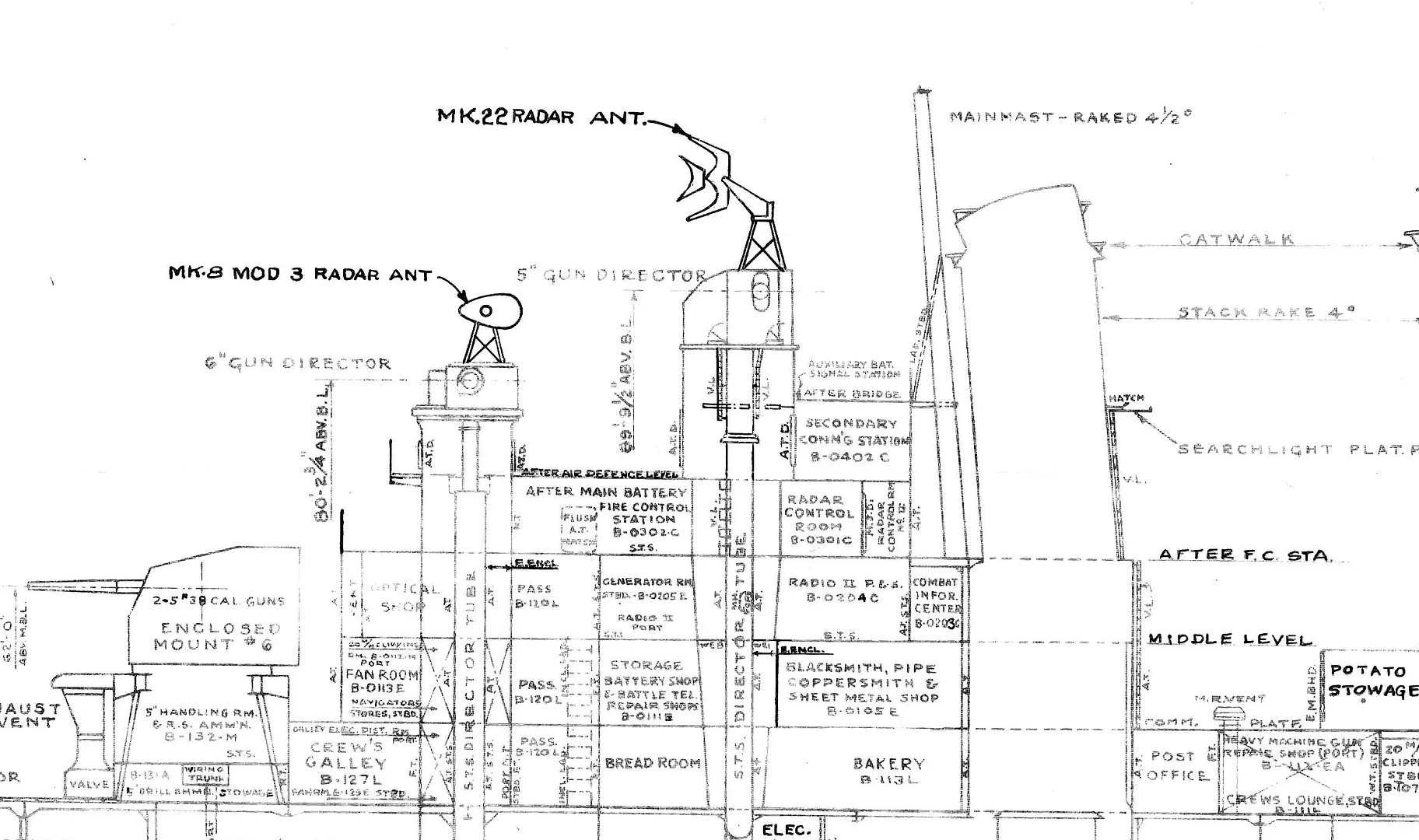

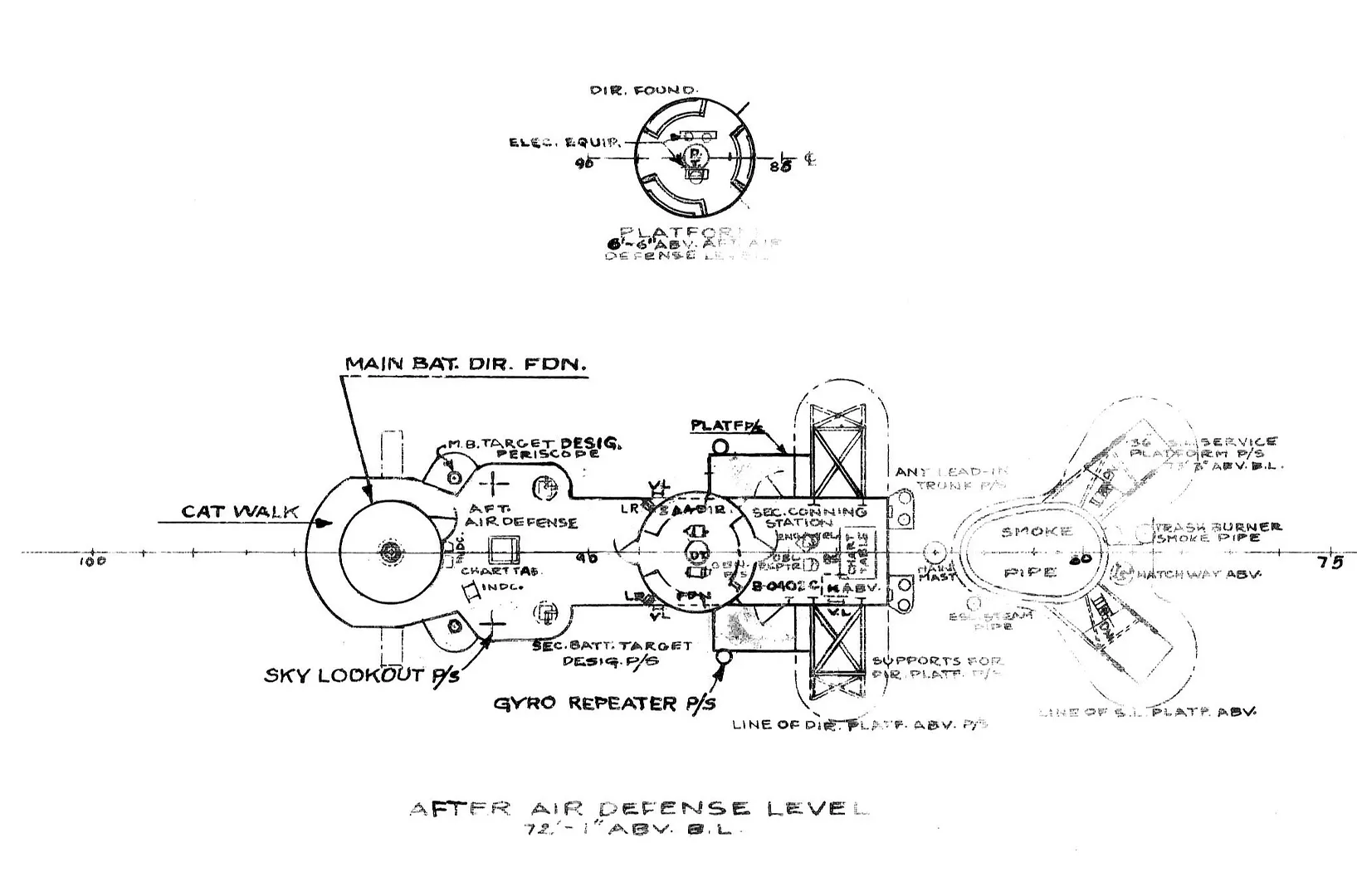

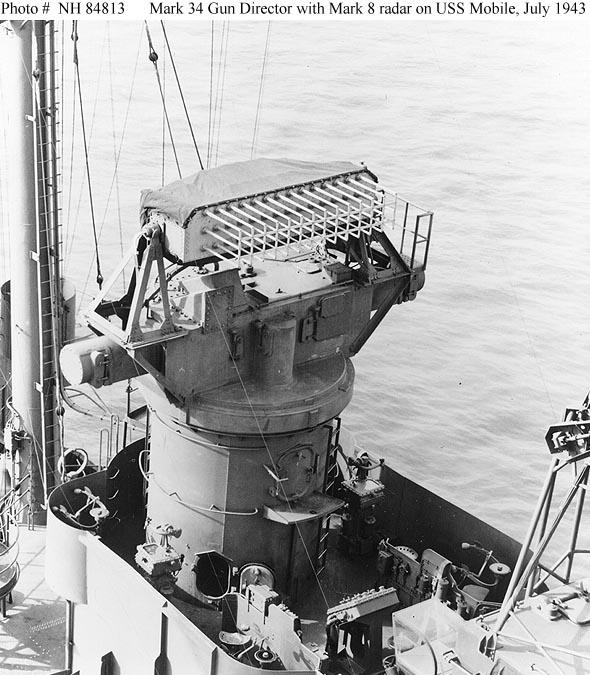

Technical schemes of the superstructure and FCS

The Cleveland’s forward primary director was also the ship’s primary spotting station, usually under the direct personal command of the ship’s leading spotter. The Cruisers of the Cleveland and Fargo class, just as the Brooklyn class were goiven the ubiquitous Gun Director Mark 34. It mounted a Rangefinder Mark 45.

The was a main-battery plotting room located below the waterline, inside the armor belt, and containing the rangekeepers and associated graphic plotters. These were Rangekeeper Mark 8, setup for the 6”/47 caliber. They had also stable-vertical gun directors Mark 41, linked to radar equipment (Mark 27, while the control consoles and indicators were setup for the Radar Equipment Mark 13., and a fire-control switchboard plus its associated battle-telephone switchboard. All cruisers had a unique single main-battery plotting room, with a single rangekeeper and stable vertical set Mark 6 used with the auxiliary computer. For divided fire, auxiliary equipment and procedures were used which changed on the larger Salem and Worcester class cruisers, fitted with duplicate rangekeepers and stable verticals.

Radars

Note that the Cleveland class arrived at a time radar for cruisers became mandatory: They were all provided with the SK-1 air-search radar, or for the latter series, the SK-2 air-search radar, the SG-6 surface-search radar

and SP fighter-direction radar. Cold war vessels were given the upgraded the AN/SPS-6 air-search radar and SR-3 air-search radar. The SK-1 was only able to track large surface ships. Developed from the SC-2, with a CXAM antenna and optional IFF Bl-5 antenna atop the main antenna. It had a 1.5 m wavelenght, a pulse width of 5 microsecond, a pulse Repetition Frequency of 60 Hz, a scan rate of 4.5 rotations per minute.

Its power unit was only 200 kW at the time, ensuring a practical rannge of 100 nautical miles (190 km) to spot bombers, 75 for fighters, 30 nm a surfaced battleship (so 55 km, well beyond gunnery range) and 13 nautical miles (24 km) only for a destroyer. For a cruiser it was probably around 40 km (21 nm). The Antenna was shaped as 17 feet square 6×6 dipole “mattress” array. As an early long-wavelength seaborne radar, it had a tendency to reflect off the sea surface and produce self-interference (Lloyd’s mirror effect) at certain altitudes. Maintaining contact with an approaching spot was difficult. This proved a significant liability during the kamikaze campaign. Many cruisers received in addition microwave radars, less subject to nulls but missing the altitude and range.

Details in USS Birmingham

Mark 34 Director

AA directors

On board aviation

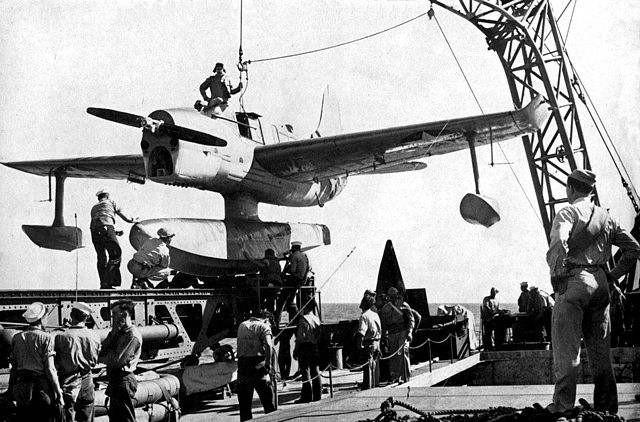

Curtis SO3C Seamew on the catapult USS Columbia, 1943

It was the best of worlds with the shape of the stern on these cruisers, able to carry two catapults and four seaplanes with a large hangar and workshop, plently of space for aviation gasoline tanks, oil, armament including depht charges and bombs. These cruisers were able to launch two planes in quick succession for reconnaissance and spotting, while the lift brough the two others, quickly lifted on the reloaded catapults for a rapid second launch. It is generally agreed the Cleveland class when they were commissioned were provided with the latest and best general purpose seaplane available, the Vought OS2U Kingfisher (ex. USS Mobile 1944). However, photos shows some carrying the Curtiss SOC seagull (ex. on Cleveland in 1944) when available to replace the mediocre Curtiss Seamew, often present of the photos. In 1945, the latter shows Curtiss SC Seahawk mandatory on board. They were still used during the Korean war.

Kingfisher onboard USS Mobile, 1944.

Crossing the line ceremony onboard USS Montpelier, Curtiss Seagull.

USS Cleveland specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 185.9 m long, 20.22 m wide, 7.47 m draft |

| Displacement | 11,744 t. standard -14 130 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts GE turbines, 4 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 100,000 hp. |

| Speed | 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) |

| Range | 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Armament | 5×3 6 in (152 mm)/47,6×2 5 in (127 mm)/25, 28x 40mm, 10x 20mm, 4 floatplanes |

| Armor | Belt 127, turrets 165, bridges 51, inner casemate 127-152 mm. |

| Crew | 1273 |

Profile Illustration of the Cleveland class

USS Cleveland 1943

USS Vincennes 1963, the last ‘conventional-state’ Cleveland class cruiser in service

A late solution: The Fargo class (1942)

Fargo, Huntingtonn, Newark, New Haven, Buffalo, Wilmington, Vallejo, Helena, Roanoke, unnamed, Tallahassee, Cheyenne, Chattanooga (CL-106 – CL-118)

USS Fargo (CL-106) was the lead ship of a sub-class of light cruisers evolved from the Cleveland serie, but most of this class was canceled due to the end of the war. The Fargo-class cruisers were a modified version dsigned by BuOrd in 1943-44 to solve several issues with the design, notably stability, by reducing top weight, and granting a better arc of fire and more Bofors 40 mm AA positions. This was achieved by a far more compact pyramidal superstructure, and single trunked funnel. Well centered, this island free most if the allocated superstructure surface for more AA while still keeping the overall displacement in check, and the metacentric height at an acceptable level. The main battery turrets were placed just a foot lower, the wing 5 inch twin gunhouses were also lowered to the main deck. The 40 mm AA mounts were lowered when possible, helped by the new compact superstructure.

Due to the design time, and approval, it was not ported on an exiting ship, USS Fargo, before the latter was launched 25 February 1945, at New York Shipbuilding Corp. New Jersey. The new cruiser, pennant CL-106, was sponsored by Mrs. F. O. Olsen. She was commissioned on 9 December 1945 with Captain Wyatt Craig in command, but of course at that point, the war was over and her main purpose, intended to deal with kamikaze, no longer relevant. Many of her design peculiarities however went to the next Worcester class. In all, 13 ships were planned.

The war ended when all these were laid down and in construction, the last being USS Wilmington (CL-111, on 5 March 1945). Only Fargo and Huntington were ever completed, the rest being cancelled, even before the end of the war, in what was called de-escalation. USS Newark was in fact the last launched, on 14 December 1945, but not commissioned. Construction was indeed canceled on 12 August 1945, 67.8% completed. She was repurposed to be used in underwater explosion tests. After those were performed, she was mothballed, then sold on 2 April 1949 for scrapping.

USS Fargo herself commissioned on 9 December 1945, four months after the war ended found limited use, and even more Huntington, commissioned early in 1946. They were perhaps the shortest-lived cruisers in USN service, as both cruisers were decommissioned in 1949–1950, after some training and gunnery exercises to evaluate their concept. But after being mothballed and placed in reserve, they were never reactivated. For USS New Haven (CL-109), launched on 28 February 1944, USS Buffalo (CL-110) on 2 April 1944, and USS Wilmington on 5 March 1945 (CL-111), construction was cancelled on 12 August 1945, at various degrees of completion (from 20 to 50%) and they were all scrapped on slip. This situation was also applied to USS Vallejo, Helena, Roanoke and an unnamed fourth vessels, all ordered, but not laid down, and cancelled 5 October 1944. The last of the Cleveland serie, USS Tallahassee (CL-116), laid down 31 Jan. 1944, USS Cheyenne (CL-117) on 29 May 1944, plus USS Chattanooga (ex-Norfolk) on 9 October 1944, Construction was cancelled on 12 August 1945 and they were scrapped on slip as well.

The same type of modification was applied to heavy cruiser as well, between the Baltimore and Oregon City sub-class. It was also applied, but to a lesser degree, to the Atlanta class, compared to the Juneau class AA cruisers. But changes to reduce instability was particularly urgent and important for the Cleveland-class, notably to deal with dangerous roll.

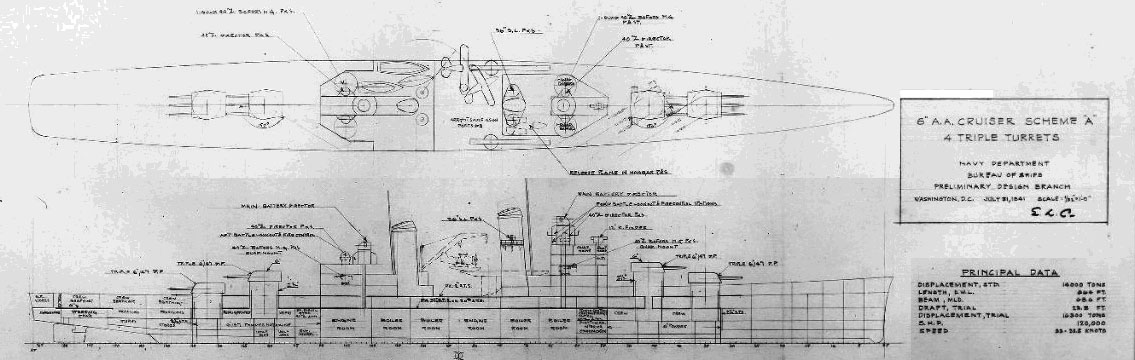

Design S-511-38 6″ A.A. Cruiser Scheme A, 31 July 1941. This was a 4 Triple Turrets Preliminary design plan prepared for the General Board. A further developent of the Cleveland, as a light cruiser with rapid-firing dual purpose 6-in/47 anti-aircraft guns in triple turret version. The latter development was never completed; so the design evolved in 1943 with five twin turret instead, and ultimately became the Worcester (CL-144) class. 664-foot waterline ship, 14,000 standard tons, emphasizing speed and main battery number with reduced protective armor. Naval History and Heritage Command., U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph coll.

USS Fargo specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 185.3 m long, 20.22 m wide, 6.60 m draft |

| Displacement | 11,500 t. standard -14 460 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | Same as Cleveland |

| Speed | Same as Cleveland |

| Range | Same as Cleveland |

| Armament | Same but 4×4 + 6×2 40 mm, 20x 20mm AA |

| Armor | Turrets 5-in, bulkheads 5-in. |

| Sensors | SK-2, SR-3 air-search radars, SG-6 surface-search radar, SP fighter-direction radar |

| Crew | 1,100 |

Torpedo and battle damage on Cleveland class vessels

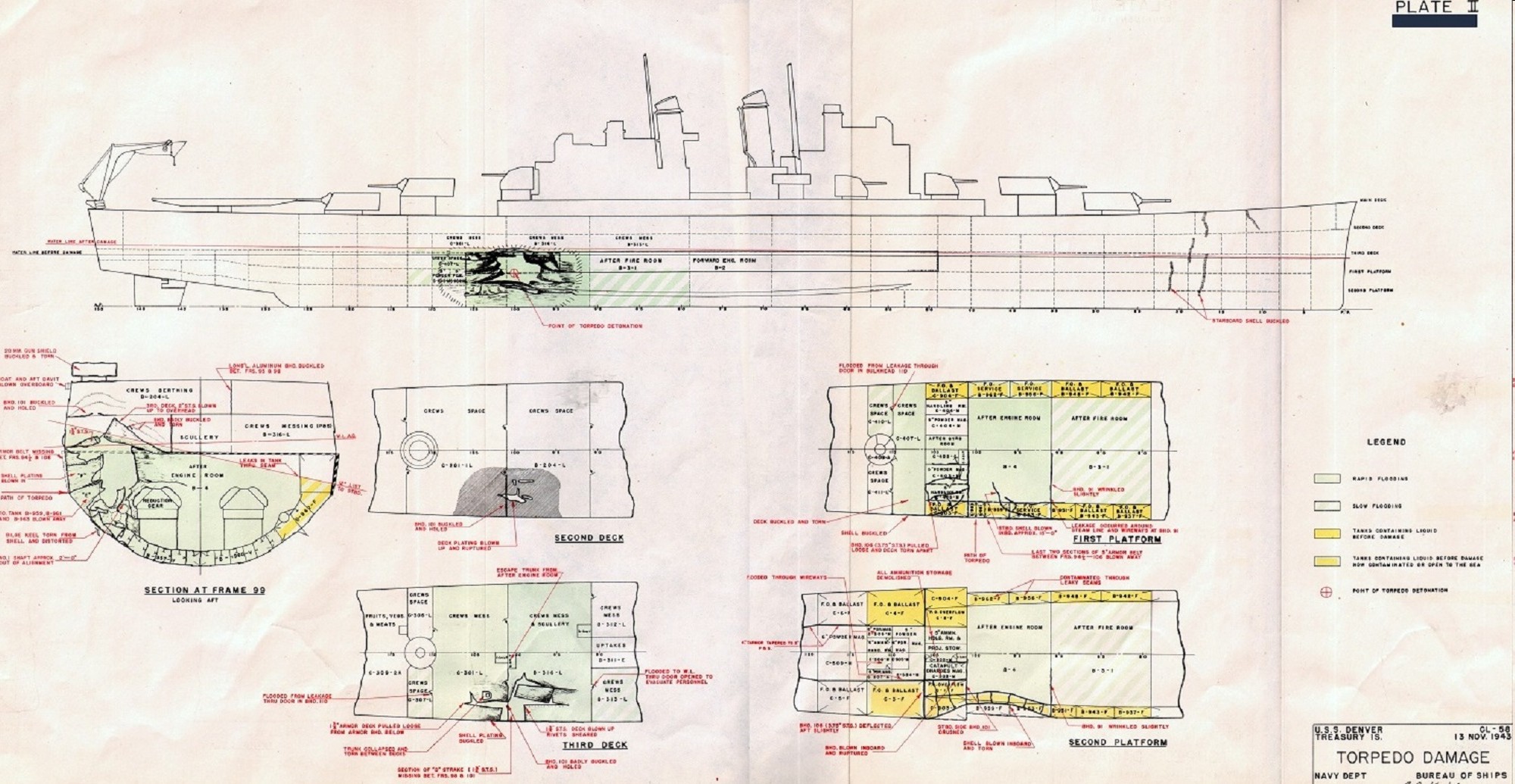

USS denver torpedo damage report

_Battle_of_Kula_Gulf_6_July_1943.jpg)

USS Helena Kula gulf report 6 July 1943

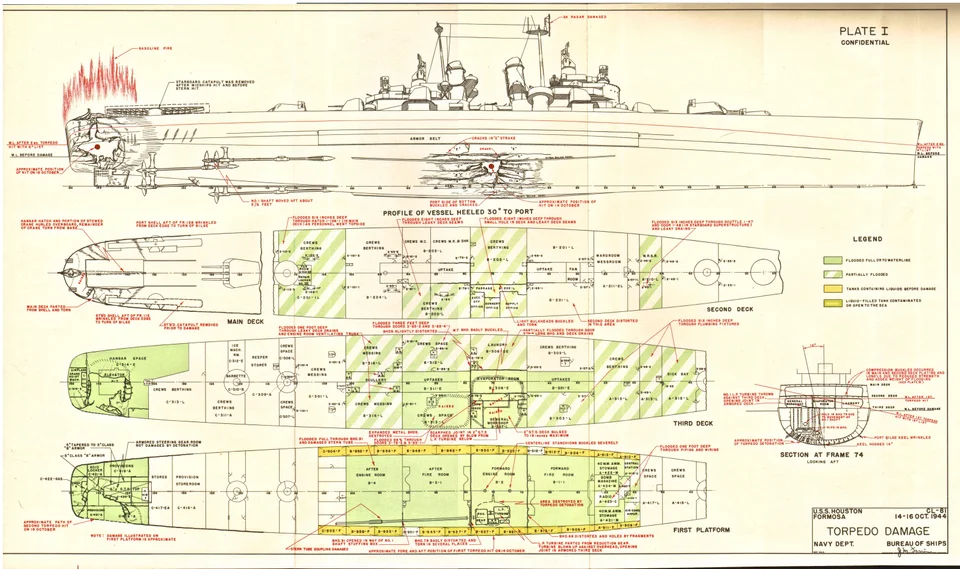

USS Houston torpedo damage report (The most serious case)

USS Houston was the only of the class very close to sinking, torpedoes by two aerial models, the other one being the USS Birmingham when closing for assistance to the crippled and burning USS Princeton. As for the CVs of the USN, the damage control parties did wonders each time.

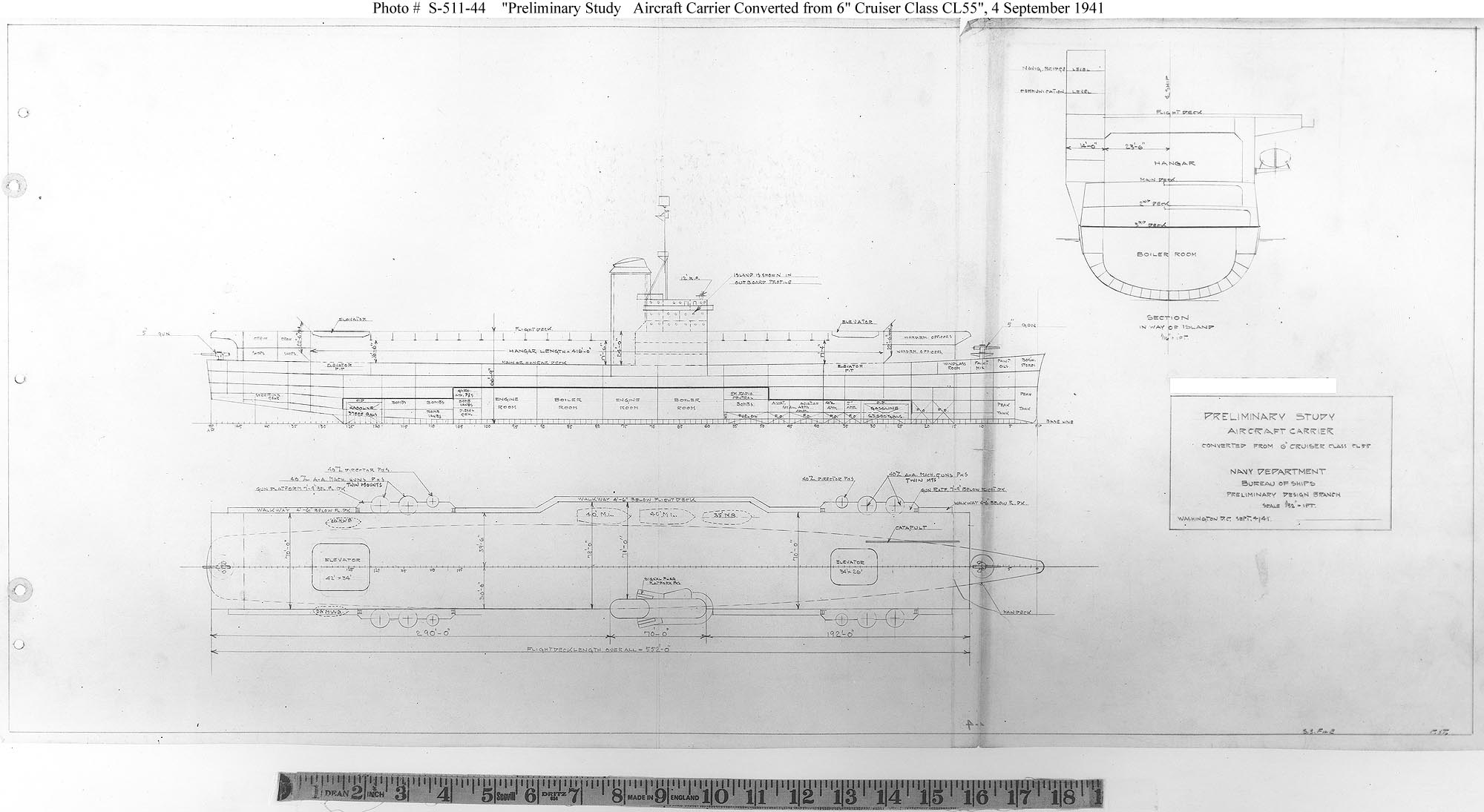

Late Summer 1941 unbuilt CV conversion

Before the Independence class (CVL) standard conversion (approved in June 1942), other schemes were studied:

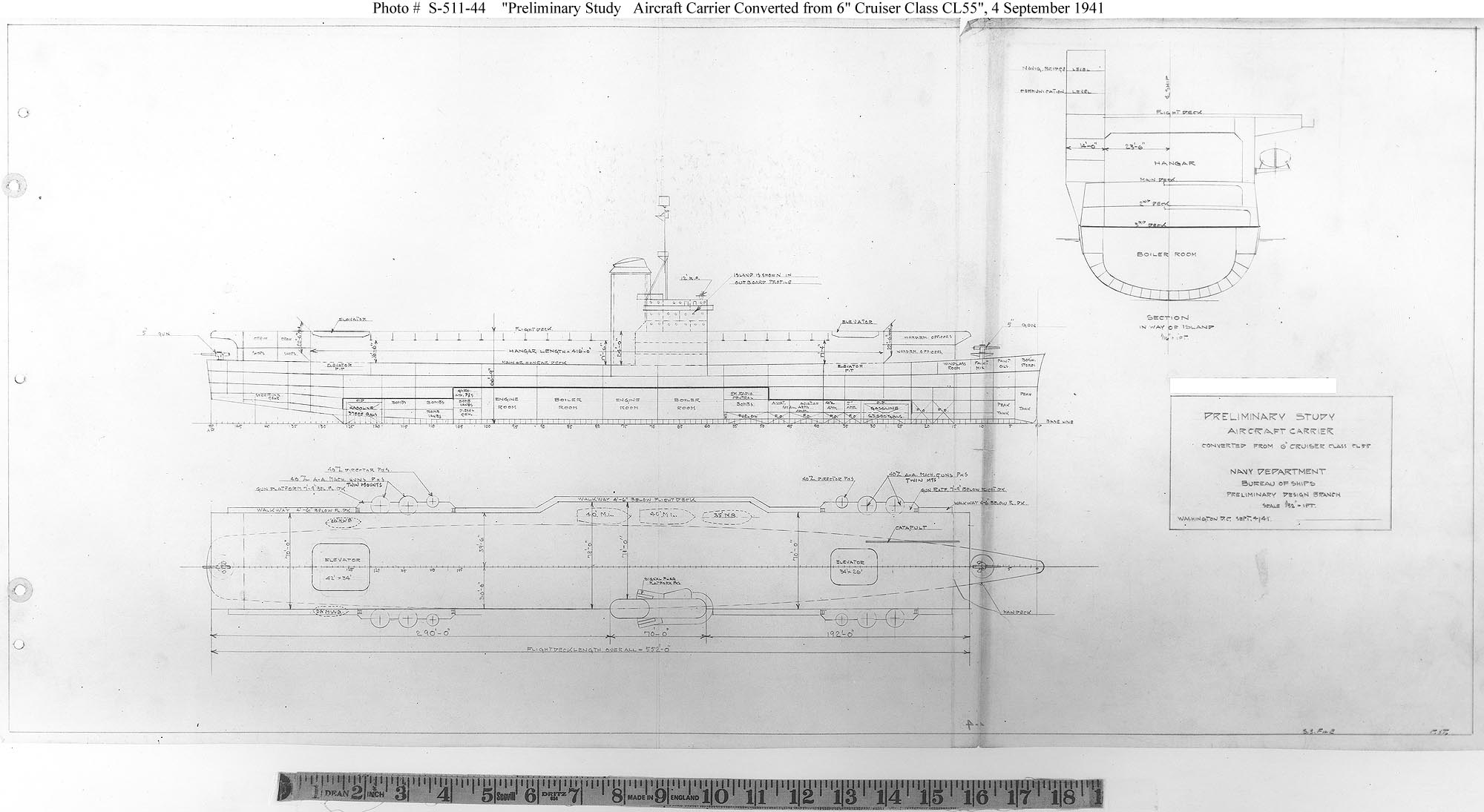

This conversion design project S511-43 dated back from August 1941. It was caracterized by a much larger island on starboard compared to the one fitted on the CVLs for stability reasons, and integrated a mast, two main AA directors, a single funnel and large staged island with the first two quad Bofors grouped fore and aft (as the Essex class) and the remainder two on the port side. Unlike the Independance class, there was an add-on overhang also on this side to allow more plane deck parking and the flight deck seems a bit wider as well.

This S511-44 prelimary study dated back 4 September 1941. It showed a slightly taller hangar but overall a comprehensive island, joint to the exhausts truncated into a single funnel. It had a large aft elevator, two 5-in guns and eight quad 40 mm Bofors (32 total) plus their four attached directors in independent sponsons, but no secondary AA artillery.

USS Fargo (CL-106)

Fargo departed Philadelphia, where she was completed, on 15 April 1946 under orders of Vice Admiral Bernard H. Bieri, on board for a goodwill cruise to Bermuda, Trinidad, Recife, Rio de Janeiro and Montevideo. On 31 May 1946, tshe sailed for the Mediterranean, visiting Turkey, Lebanon, Greece, Italy, France, North Africa. She was stationed as an American representative at Trieste during the crisis between Italy and Yugoslavia.

She was back to New York City on 2 March 1947 but mad another cruise in the Mediterranean on 20 May 1947 being during one month, flagship for the Commander of Med. Naval Forces. She was back to Newport on 13 September but the crew and the ship were prepared for extensive Atlantic Fleet exercises. They started in October and were completed in November 1947, from Bermuda to Newfoundland.

She hosted Vice Admiral Arthur W. Radford (2nd Task Fleet Commander). In 1948, she made another tour of the Mediterranean and another large scale exercises in the Caribbean. The routine went on in 1949 as well. After these active years were her machinery was well tested, she was eventually decommissioned, placed in extensive reserve.

She was affected to the Bayonne (New Jersey) long-term berth on 14 February 1950. During the Korean and Vietnam she stayed in reserve, until she was stricken from the Naval Register on 1 March 1970 and sold for BU, on 18 August 1971. She was broken up by the Union Minerals and Alloys Corporation in Kearney (New Jersey).

USS Huntington (CL-107)

USS Huntingon was commissioned on 23 February 1946 under command of Captain Donald Rex Tallman. She made her sea trials, followed by a shakedown cruise off Guantánamo Bay (Cuba) until back to Philadelphia for post-trials fixes. On 23 July 1946 she sailed for her first mission, joining the 6th Fleet in the Mediterranean. Like her sister ships, she visited many ports like Naples, Malta, Villefranche, and Alexandria. Her presence was needed amidst regional tensions duen to communism insurgency in Greece, troubles in Turkey and in the Balkans or in palestine. In this volatile situation she reassured the US allied. She departed Gibraltar on 8 February 1947, to join exercises off Guantánamo Bay. She was back in Norfolk and later Newport and Rhode Island, departing on 20 May 1947 for another tour in the Mediterranean.

Back on 13 September 1947, Huntington departed Philadelphia on 24 October, carrying the Naval Reserve for exercises off Bermuda, and up to Newfoundland. This was over on 14 November 1947. She was refitted extensively afterwards in Philadelphia, her overhaul lasting until 12 April 1948.

Captain Arleigh Burke (yes, that one), assumed command in between December 1947 and December 1948. She departed Norfolk in April from a refresher training cruise, stopped in Newport and made another tour in the Mediterranean, starting on 1st June 1948. She visited mny ports until August 1948 and crossed the Suez Canal on 22 September 1948 for another good will tour of East Africa, then west Africa via the Cape of good hope, and South America. She visited Buenos Aires in November, greetng her guest President Juan Perón. She sailed to Uruguay and received there another visit from President Luis Berres, on 10 November. She stopped again at Rio de Janeiro and Trinidad, then headed home, arriving on 8 December 1948.

In January she made another cruise from Philadelphia to the Caribbean and back to Newport. From 22 January she stayed idle, until decommissioned on 15 June 1949. She was placed in extensive reserve, she lasted until she was struck from the List on 1 September 1961. She was sold for BU at Boston Metals (Baltimore) on 16 May 1962.

Cold War Clevelands (1950-1979)

CGL-5 USS Oklahoma City in 1974

Apart the ten Independence class fast CVs which a few soldiered under other flags longer than their USN counterparts (like the Spanish Dedalo), the fifteen Cleveland class cruisers were decommissioned in 1949-50 amidst postwar long-term reserve program. With the Korean war, some were reactivated and participated to various missions, and went to various periods of semi-reserve. Apart radars upgrade in the 1950s, the conventional ships kept “in stock” condition were discarded in 1960. Other were converted with the CG, CAG and CLG modernization program as missile cruisers or for other uses. A single one was preserved: USS Little Rock. The others were decommissioned in the 1970s.

The CGL fleet escort conversions were the most interesting, but they will be seen as a standalone post. These cruisers had their entire aft section, after the second funnel, completely rebuilt in 1955-58 or 1956-60, with a stage structure for FCS, entirely dedicated to carry and operate the Talos long range SAM and Terrier medium range SAM on the early and later serie. In all, six ships were so converted with many differences in design. CG3-5 (USS Galverston, Little Rock, Oklahoma City) were Talos escorts, while CG6-8 (USS Providence, Springfield, Topeka). Two were discarded in 1973, one in 1976 two in 1979 and one preserved. More more information about these, see cold war USN missile cruisers. Their larger Baltimore class heavy cruiser wartime cousins benefited from more ambitious conversion programs allowing them so serve until the 1980s.

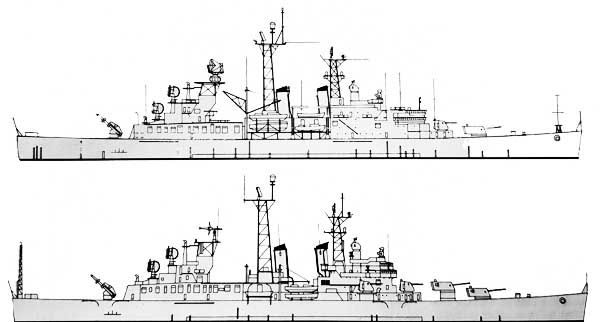

Compared profiles of the two conversions, CG and CGL.

While the Cleveland-class cruisers served mainly in the Pacific and especially with the Fast Carrier Task Force (with Cleveland-based Independence class CVLs) some also served in Europe and Africa with the U.S. Atlantic Fleet durung late 1942-late 1944 operations until the Mediterranean became an “allied lake” and the North Alantic mostly secured. A cruiser was less helpful against u-Boats and the bulk of the surface Kriegsmarine was gone by late 1944. All of these warships worked heavily, winning many battle stars, awards, and survived the war. They were initially decommissioned by 1950 except USS Manchester, soldiering until 1956. None saw action in the Korean War but the latter, and none of the “long reserve” was recommissioned as they required a crew almost as large as the Baltimore-class cruiser, which were reactivated instead due to their longer range artillery and better caracteristics overall. The non-converted ships were eventually sold off, directly from from the reserve fleet to scrap, from 1959. Six were however taken to bolster the surface fleet missile carriers and converted into guided missile cruisers, reactivated during the late 1950s. They served into the 1970s, 1979 for the last one but the Talos-armed ships suffered from even greater stability problems than the original, becoming so severe in fact USS Galveston was prematurely decommissioned in 1970, not worth the cost of her reconstruction. USS Oklahoma City and Little Rock were given a large amount of ballast, internal rearrangement allowing them after an overhault to remain active until 1979, December, for Oklahoma City.

Profiles

USS Birmingham in 1944, soon after the battle of Leyte where she was badly damaged by the explosion of the carrier St Lo (to be redone)

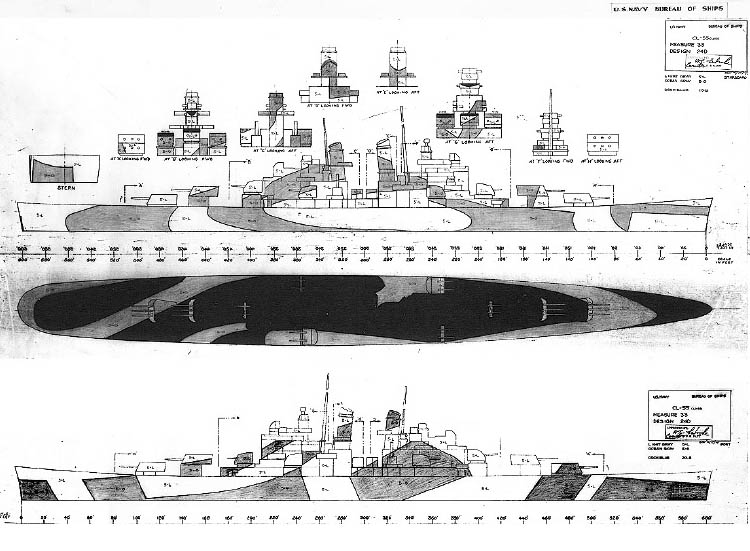

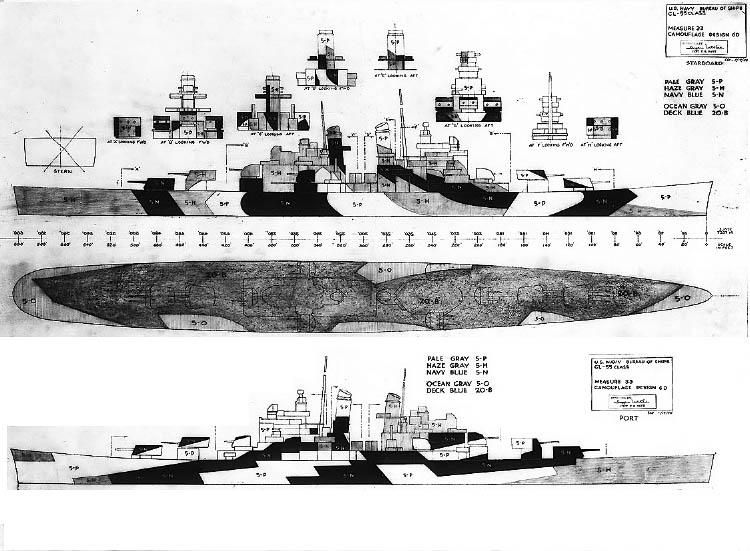

ONI Camouflage Measure 33, USS Cleveland 1944.

Measure 33 design 40, 1944.

Measure 39 design 11

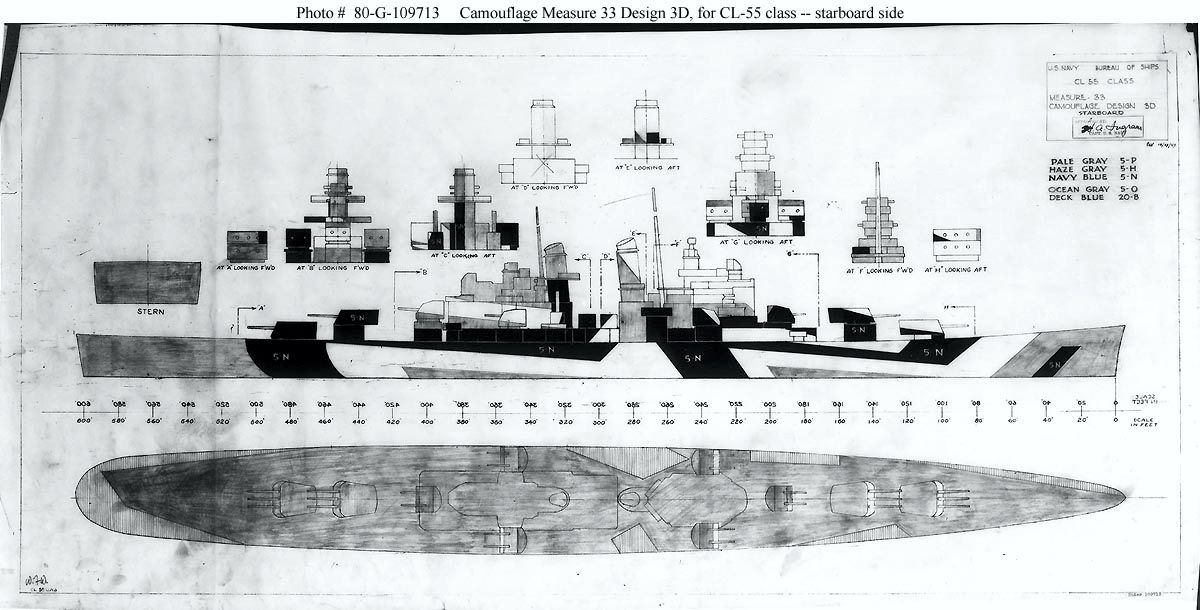

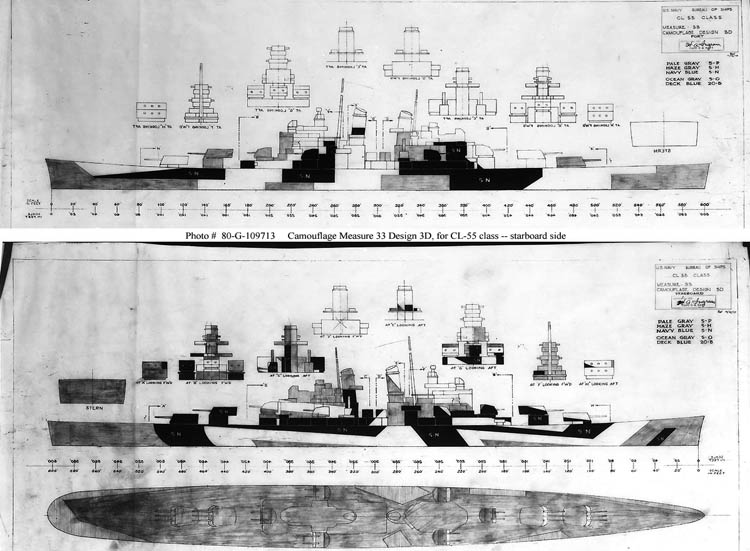

Measure 33 design 3d.

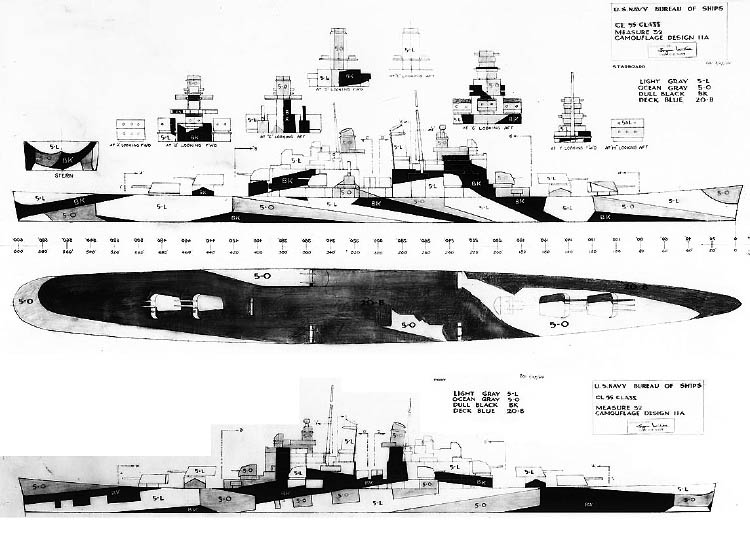

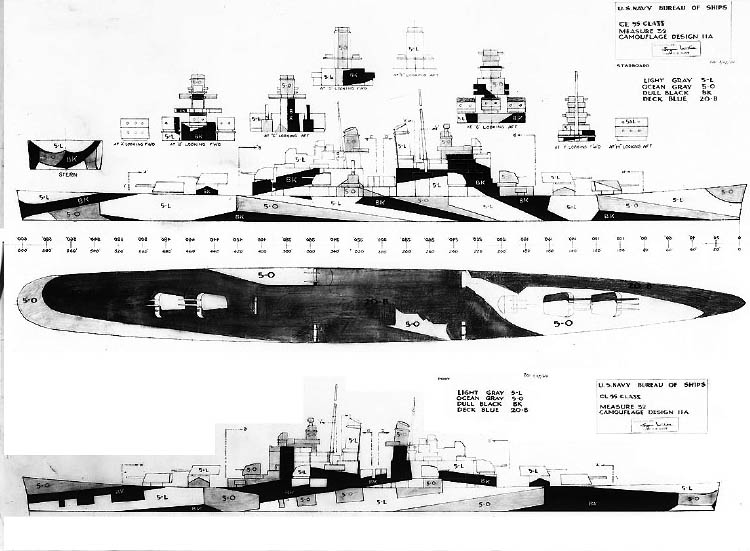

Measure 32 design 11a.

Measure 32 design 4d.

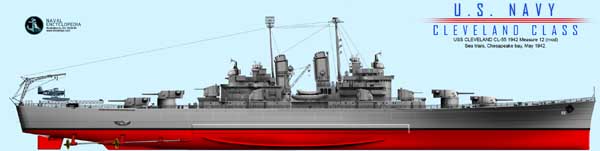

USS Cleveland, CL-55 in trials off Chesapeake, May 1942, measure 3 light ocean gray

USS Cleveland in Operation Torch, November 1942 measure 12 modified

(More to come)

Sources

Links

https://www.okieboat.com/Cleveland%20Class%20History.html

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_5-38_mk12.php

http://www.navsource.org/archives/01/57x.htm

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Admin-Hist/USN-Admin/index.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/weapons_cleveland_class_cruisers.html

https://www.okieboat.com/Cleveland%20Class%20History.html

https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/s-file/S-511-18.html

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/images/s-file/

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/S/k/SK2_air_search_radar.htm

http://www.navsource.org/archives/04/107/04107.htm

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/h/huntington-ii.html

https://www.okieboat.com/Gun%20Director.html

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/cl-55.htm

http://www.hazegray.org/navhist/cruisers/ca-cl2.htm

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/weapons_cleveland_class_cruisers.html

http://www.microworks.net/pacific/ships/cruisers/cleveland.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20150406062952/http://buffalonavalpark.org/exhibits/ships/

Books

J. Gardiner Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

Wright, C. C. (1998). “Question 51/96: Anti-Aircraft Armament of US Cleveland Class Cruisers”.

Norman Friedman, U.S. Cruisers, An Illustrated Design History

Naval Anti-Aircraft Guns and Gunnery loc 3772 – 3792

M. J. Whitley, Cruisers Of World War Two, An International Encyclopedia 1995

Those Cleveland Class Cruisers. An exercise inexpediency in N.Wilder Post.’ Sea Classics

Buffalo & Erie County Naval & Military Park.

Eye candy 3D

Model Kits Corner

On Scalemates

-The scale shipyard produced on demand 1:96 models of any Cleveland ship for RC.

-USS Cleveland CL-55 U.S. Navy Light Cruiser Blue Ridge Models 1:350

-USS Miami CL-89 (1944) ex-Gulfstream Models kit Iron Shipwrights 1:350

-USS Birmingham CL-62 Very Fire 1:350

-U.S.S. Springfield With “Terrier” Guided Missiles FROG 1:500

-USS Galveston CLG3 with “Terrier” guided missiles Renwal 1:500

-U.S.S. Springfield Revell 1:500

-USS Manchester Lindberg 1:600 (and many others)

-1:700 USS Cleveland CL-55 Blue Ridge Models/midship models 1:700 (many too)

-USS Galveston CLG-3 1968 Niko Model 1:700

-CL-89 Miami w/Photo-etched parts Pit-Road 1:700

-U.S.S. Houston CL-81 Lindberg 1:1080 (and others)

-U.S S. Houston Crucero NorteamericanoNecomisa 1:1080

-USS Columbia CL-56 (1943) Hansa 1:1200

-USS Vincennes CL-64 Navis – Neptun 1:1250

-Many 3d printed parts Model Monkey 1:350

The Cleveland class in action

Note: The pennant list seems incomplete: That’s because of all hulls laid down, ten were reordered as CVLs (Independence class) with the new pennants CVL-22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30 (former CL-59 Amsterdam, CL-61 Tallahassee, CL-76 New Haven, CL-77 Huntington, CL-78 Dayton, CL-79 Wilmington, CL-85 Fargo, CL-99 Buffalo, CL-100 Newark). Others saw their contract cancelled in December 1940: USS Buffalo (CL-84), Newark (CL-88), and Youngstown (CL-94).

USS Cleveland (CL-55)

USS Cleveland (CL-55)

USS Cleveland underway at sea in November 1942, Operation Torch

After being commissioned on 15 June 1942, with Captain E. W. Burrough as first captain, and making quick sea trials, USS Norfolk was sent in Chesapeake Bay for advanced training from 10 October 1942. In November she sailed to join a task force off Bermuda, bound for the invasion of North Africa. She covered the landings at Fedhala in French Morocco (8 November) and stayed there until 12 November, before going back to Norfolk on 24 November 1942. She sailed for the Pacific on 5 December 1942, stopping at Efate Island on 16 January 1943. She saw first the Solomon Islands campaign with Task Force 18, escortung a troop convoy bound to Guadalcanal. From 27 to 31 January, she shelled Japanese positions on the island and patrolled, while later fending off air atacks in the Battle of Rennell Island (29–30 January). She then joined TF 68 to be soon found involved in the battle of “the Slot”, on 6 March 1943. After shelling Japanese airfields at Vila (Kolombangara) she shelped sinking the destroyers Minegumo and Murasame durring the night (battle of Blackett Strait).

Captain Andrew G. Shepard took command in June and she covered with the TF 68, the “Merrill’s Marauders”, bombading the Shortland Islands on 30 June 1943, provided close support during the invasion of Munda (New Georgia) on 12 July.After maintenance and crew’s rest at Sydney she was back off Treasury Islands for the 26–27 October preparatory shelling. She then moved on Buka Island and the Bonins, on 1 November 1943, in support the invasion of Bougainville. She shelled also bases in the Shortlands and intercepted the relief night Japanese force (“Tokyo Express”) in what became the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, gaining a Navy Unit Commendation.

USS Cleveland poured showed the accuracy of her modern controlled fire by crippling all Japanese cruisers for over an hour, almost single-handedly destroying IJN Sendai, and chasing the rest until daybreak. She later repelled a morning air attack and was rocked by several near-misses. Back off Buka she made another bombardment on 23 December 1943 before being sent patrolling between Truk and Green Island in Papua New Guinea, until 18 February 1944.

She cover the invasion on Emirau Island (17-23 March) and was replenished and maintained at Sydney to be back to the Solomons on 21 April 1944, in preparation for the Marianas operation. She made a run of practice bombardment on 20 May, surprised to be shot back by useen IJN coastal fortifications that she quickly silenced. From 8 June to 12 August she was in the Marianas, starting on 24 July with the invasion of Tinian, helping there and assisting the crippled destroyed USS Norman Scott, hit by shore batteries. USS Cleveland interposed herself in front of the shore batteries while conducting precised fire to silence them, also making softening-up bombardments and then gave fire support for invading troops until she joined TF 58 for the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 June. Although few enemy aircraft penetrated the screen of American carrier planes, Cleveland was credited on demand. She also shot down an aircraft, assisting shooting another.

On 12-29 September 1943, was part of the invasion of the Palaus. Afterwards she sailed to Manus Island on 5 October then sailed to the US for a major overhaul which lasted almost a year. She was back in the Philippines, Subic Bay, on 9 February 1945. She made a sortie against Corregidor on 13–14 February, destroying the fortress which was later assaulted. She was present in all others Philippines campaig operations, covered landings at Puerto Princesa, but also the Visayas, Panay, Malabang-Parang on Mindanao. Back in Subic Bay on 7 June she covered other operations on demand, then sailed for more fire support at Brunei Bay, Borneo on 10 June 1944. After resplenishing at Subic Bay on 15 June, she was in Manila, carrying Army Douglas MacArthur and his staff for the assault on Balikpapan. She started a pre-landing bombardment the next morning, 31 June, and headed back for Manila on 3 July.

On 13 July she joined TF 95 to Okinawa on 16 July. She made sweeps against Japanese shipping until 7 August. She was back to Okinawa on 9 September, supporting the last operations, and preparing for the invasion of Japan. She made a POW repatriation run from Wakayama, and stayed in the naval occupation group until the 6th Army landing on Honshū. She visited Tokyo Bay on 28 October to 1 November 1945 before going back to Pearl Harbor, and then San Diego, and via the Panama Canal Boston (5 December) for an overhaul. Training exercises followed in 1946-47, notably with the Naval Reserve, between the Carbbean and Halifax in Nova Scotia, also visiting and Quebec in June 1946. She was back in Philadelphia for inactivation, decommissioned and in reserve from 7 February 1947. Judged already well-battered, the lead ship of the class, awarded 13 battle stars, stayed in long term reserve until sold for scrap on 18 February 1960.

USS Columbia (CL-56)

USS Columbia (CL-56)

USS Columbia off San Pedro, 1945

USS Columbia was built at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation, Camden, New Jersey, launched 17 December 1941 and Commissioned on 29 July 1942 under command of Captain W. A. Heard, starting accelerated sea trials and training until November. On 9 November 1942 she departed Norfolk for Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides (10 December) starting her Guadalcanal campaign. On 29 January 1943 while off Rennell Island, covering transports she had her first heavy air attack. The battle of Rennell Island saw her splashing down three enemy planes. She was based in Efate from 1 February 1943 and went on patrolling the Solomons until June. She carried out a shellins and als a minelaying mission on 29–30 June in relation to the attack on New Georgia. On 11–12 July she shelled Munda and was later in maintenance at Sydney, back in September to patrol southeast of the Solomons.

USS Columbia was back in her division on 24 September, off Vella LaVella. She later covered Marines on Bougainville (1st November 1943), shelling Buka and Bonis (Shortlands). During the night they intercepted a Japanese group, which became the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay Columbia helpping to sink (with her suister ship Cleveland) IJN Sendai and the destroyer Hatsukaze. She stayed in support off Bougainville in December as well. After training in the New Hebrides by January 1944, she spearhead the attack and occupation of Nissan (Green Islands) on 13-18 February 1944. In March 1944 her group patrolled between Truk and Kavieng, searching for enemy shipping. She covered afterwards the assault on the Emirau Island (17-23 March) and on 4 April stopped at Port Purvis (Solomons) before heading for San Francisco, for an overhaul that lasted until her return to the Solomons on 24 August 1944, back to Port Purvis.

USS Columbia made a sortie on 6 September with the covering force bound for the Palau islands. She remained off Peleliu, providing gunfire support and protecting shipping until back to resupply in Manus on 28 September. She was back in cover on 6 October, and moved to the assault on Dinagat and other islands, cericling Leyte Gulf, until 17 October. Then USS Columbia provided gunfire cover on the 19th, and participated in the night of 24 October to repelling the southern force entering Leyte Gulf (Battle of Surigao Strait). Columbia teamed with Oldenburg’s battleships division, crossing the T of the incoming Japanese column with devastating results. She helped crippling Yamashiro, firing away on Mogami and other ships. Columbia sank by herself the destroyer Asagumo.

She replenished at Manus in November and was back in Leyte Gulf mostly for air attack cover. By December she was in the Kossol Roads, Palaus, covering the attack on Mindoro. On 14 December 1944 she had an accidental 5-inch (127 mm) misfire, killing four. On 1st January 1945, USS Columbia operated in the Lingayen Gulf and on the 6th participated in the pre-invasion bombardments. Soon the first of many massive Japanese kamikaze attacks started. She first was shook by a near miss to be then struck on her port quarter. The plane and its bomb penetrated two decks before exploding. The immediate result was 13 killed and 44 wounded while both her aft turrets were out of action.

Blazing hard, only flooding of the two magazines prevented other explosions. Damage control teams did wonders however and Columbia was soon in full control, and resumed her bombardment with her forward turrets. She remain in close support also for night underwater demolition teams. Dried ammunition was carried forward by hand. On 9 January USS Columbia could not manoeuver and was struck by another kamikaze. It knocked out six gun directors, killing 24 men, wounding 97, but the new fire was soon mastered again and she was back in action. That night however her captain decided it was enough and sailed her out, escorting unloaded transports. The actions of her safety team won her a Navy Unit Commendation.

She was first repaired at San Pedro Bay in Leyte before sailing for her overdue overhaul on the west coast. She was back from the US on 16 June 1945 and headed for Balikpapan in Borneo, dropping anchor there for gunnery support on 28 June, the assault starting on 1st July. She covered Australian troops, giving close on-demand artillery support until departing to join Task Force 95 sweeping the China sea in search of Japanese shipping. Later she carried inspection parties to Truk when the war ended, and carried Army passengers between Guam, Saipan, and Iwo Jima. On 31 October she sailed for home, the west coast, Philadelphia, arriving on 5 December. An overhaul plus training the Naval Reserve follwoed, until 1 July 1946. Decommissioned, she was placed in prolongated reserve at Philadelphia on 30 November 1946. She stayed there until sold for scrap on 18 February 1959. In addition to the Navy Unit Commendation, Columbia received 10 battle stars for World War II service, her motto was “Gem of the Ocean”.

USS Montpelier (CL-57)

USS Montpelier (CL-57)

USS Montpelier, launched on 12 February 1942 (named after Montpelier, Vermont), was commissioned on 9 September 1942 under command of her wartime Captain, Leighton Wood. After an express shakedown cruise she was bound for Nouméa in New Caledonia to prepare operations against the Solomons. She departed Norfolk as flagship of Cruiser Division 12 (CruDiv 12) on 18 January 1943, with Rear Admiral A. S. Merrill on board. On 25 January she was in Efate in New Hebrides, her home base. During a sweep of Guadalcanal, she participated in the Battle of Rennell Island (last naval engagement of the whole Campaign), and covered the landings on the Russell Islands on 21 February. On 5–6 March she shelled Stanmore airfield (Kolombangara) and took part in the Battle of Blackett Strait. She also shelled Poporang Island on 29–30 June and Munda fortified positions on 11–12 July, then the conquest of New Georgia, patrolling the area to prevent withdrawals.

She made a stop for respenishing and the crew’s rest in Sydney, Australia, and joined TF 39 as flagship again, for the invasion of the Treasury and Bougainville Islands. On 1st November she shelled the Buka and Bonis airfields (northern tip of Bougainville), Poporang and Balalae islands (Shortlands). She also took part in the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay on 2-3 November 1943 under command of Admiral Merrill. Montpelier’s gunners also claimed their first five “bogeys”.

After some rest and resplenishment, on 15–19 February 1944 USS Montpelier covered the Green Islands assault (Bismarck Archipelago) and in March, she patrolled south of Truk and covered the invasion of the Emirau Islands. On 20 May 1944 she was hit by shore batterues when shelling Japanese shore installations on Shortland, Poporang, and Magusaiai. On 1st October 1944 she teamed with the Special Air Task Force (SATFOR) for the assault on Saipan, starting pre-invasion shelling on 14 (Mariana Campaign). She later joined TF 58 and took part in Battle of the Philippine Sea (19–21 June) before returning to shelling Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. She then left for the US and her major wartime overhaul.

She was back on 25 November in Leyte Gulf, attacked by a kamikaze on 27 November, and near-missed. She repelled many other kamikaze attacks and splashed four more, while on 12 December covering the assault on Mindoro. She also provided AA during the Lingayen Gulf landing (January 1945) and the newt month she was off Mariveles Harbor, Corregidor and shelled Japanese positions in Palawan. On 14–23 April, she covered the attack on Mindanao and sailing from Subic Bay she took part in the operations of Borneo on 9 June.Until 2 July 1945, she covered operations at Balikpapan and until early August she made three anti-shipping patrols in the East China Sea with TF 95.

She was in Wakayama in Japan, when the war ended, soon making her first trip back home with POWs. Part of her crew viewed the ruins of Hiroshima. On 18 October, she covered landings at Matsuyama and departed Hiro Wan on 15 November for her run to the East Coast, via Hawaii, to San Diego. She went through the Panama Canal to be in New York City for a parade. On 1st July 1946 she was with the Atlantic 16th Fleet for a time, before being decommissioned and placed into the long term reserve in Philadelphia from 24 January 1947. She was never “woke up” and was stricken in 1959, BU 1960. During her campaign she was awarded 13 battle stars.

USS Denver (CL-58)

USS Denver (CL-58)

USS Denver Underway, circa December 1942. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

USS Denver was commissioned on 15 October 1942, with Captain Robert Carney in command. She sailed from Philadelphia on 23 January 1943 for Efate in New Hebrides, this time under command of Thomas Darden. Her actions included the Vila (Kolombangara) attack on 6 March, co-sinking Minegumo and Murasame at Blackett Strait; Ballale Island (29–30 June) in New Georgia and sorties with TF 39 at Cape Torokina (Bougainville), battle of Empress Augusta Bay in which she was hit by three 8-inch shells, failing to detonate. She earned a Navy Unit Commendation. Off Cape Torokina (November 1943) she was hit by an aerial torpedo, knocking out all power and communications onboard, killing. She was towed by USS Sioux to Port Purvis, then Pawnee (Espiritu Santo) until able to sail to Mare Island for permanent repairs.

She was back at Eniwetok on 22 June 1944, then attacked the Bonins and Marianas, bombarded Iwo Jima on 4 July and back to Eniwetok in August. In September she shelled Angaur Island and covered a minesweeping action before the landings on Ulithi (23 September). On 12 October she covered the landings on Leyte, shalling Suluan Island and Dulag, then the southern landing beaches. She took part in the Surigao Strait battle on 24 October, co-sinking IJN Yamashiro and later IJN Asagumo on 25 October.

Still in Leyte Gulf, she guarded the TF agains Kamiikaze attacks taking a hard near-miss 28 October causing minor damage and flooding. In another attack on 27 November she had four wounded due to fragments of an explosion 200 yards (180 m), starboard quarter. She covered the Mindoro landings (13–16 December), and from San Pedro Bay on 3 January she covered the landings at Lingayen Gulf and the Zambales on 29–30 January, Nasugbu 31 January, before escorting a convoy to Mindoro (1-7 February), and covering landings around Mariveles Bay (13-16 February) rescuing survivors of USS La Vallette then shelling Palawan and Mindanao until May 1945.

On 7 June 1945, USS Denver covered the assaults on Brunei Bay (Borneo) and Balikpapan and another action on Leyte on 4 July, after a brief overhaul. She was off Okinawa on 13 July, and hunting Japanese shipping with TF 95, until 7 August. She made a POW run from Wakayama, covered the landing at Wakanoura Wan, before arriving at Norfolk on 21 November 1945. After another overhaul she was used in Newport, Rhode Island by January 1946 for training the Naval Reserve, and visiting Quebec. Back to Philadelphia NyD she was placed in long reserve from 7 February 1947 until Stricken on 1 March 1959 and sold for BU in February 1960. For her service she was awarded a Navy Unit Commendation and 11 battle stars.

USS Santa Fe (CL-60)

USS Santa Fe (CL-60)

USS Santa Fe 12 Decmember 1944

USS Santa Fe was commissioned on 24 November 1942, with Captain Russell S. Berkey in command and after her shakedown cruise on the east coast, she sailed for the Pacific, first Pearl Harbor on 22 March 1943 and then north, to the Aleutians. On 25 April 1943, after six days there she shelled Attu Island, under Japanese occupation. For four months afterwards she patrolled the Aleutians in case of IJN reinforcements, with shellings of Kiska on 6 July and 22 July. Gunfire support for invasion started on 15 August. She departed on 25 August back to Pearl Harbor and prepared to join Cruiser Division 13, fast carrier task forces, spearheading the island hopping campaign. She escorted two carrier from Pearl Harbor bound to Tarawa (18–19 September) and Wake (5–6 October). Back to Pearl, she departed again on 21 October, detached to escort transports reinforcing Bougainville. She was there on 7 November, protecting her force from furious air attacks. After a resplenishment at Espiritu Santo on 14 November she escorted another force to the Gilbert Islands and at the end of the month shelled positions on Tarawa bfore joining the fast carrier force on 26 November bound to Kwajalein, arriving on 4 December, anc back to Pearl Harbor.

She was absent the first weeks of 1944, back home for an overhaul and trained for coordination firing in future amphibious operations off San Pedro in California. On 13 January she sailed with the task force to the Marshall Islands. On 29 January she shelled Wotje and then Kwajalein, called for close gunfire support during the invasion and resplinishing at Majuro on 7 February 1944. She assisted her force raiding Truk on 16–17 February, Saipan on 22 February. After a stop at Espiritu, she sailed again on 15 March with USS Enterprise and Belleau Wood bound for Emirau Island. She shelled Palau, Yap, and Woleai and on 13 April, escorted USS Hornet(ii), in support of the landings at Hollandia in New Guinea. It was over on 28 April and she covered a new raid on Truk, Satawan, and Ponape until 1st May, before resplenishing at Kwajalein.

Santa Fe assisted in the Marshalls USS Bunker Hill durng raids on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam (11–16 June). On 19 June, IJN aviation fell on the 5th Fleet and USS Santa Fe AA crew contributed to splash many planes. On the night of the 20-21 USS Santa Fe turned on her lights to help guide American planes back to their carriers. A raid on Pagan Island followed on 24 June, a resupply at Eniwetok. Back to Hornet’s group she covered a raid on Iwo Jima on 4 July followed by Guam and Rota, Yap and Ulithi, then Iwo Jima again (4-5 August) while defeating a small relief Japanese convoy (IJN Matsu sunk). She reupplied at Eniwetok on 11 August and from 30 August 1944 to 26 January 1945, she joined the USS Essex Carrier Group: Strikes on Peleliu, Mindanao, second Japanese convoy intercepted, raids on the Visayan Sea and other positions in the Philippines and the TF anchored in the Kossol Passage (Palaus) on 27 September 1944.

New attacks on Okinawa and Formosa in October followed, but on 13 October, Canberra and Houston were torpedoed and Santa Fe, Birmingham, and Mobile were detached to help tow these out. On 16 October underway, she was attacked by a group of Toprpedo bombers, one dropping its torpedo into the wake. Hit, the same tried to crash on her bow but hit the water (starboard bow) but showering flaming gasoline on the 20 mm guns with Marines and one sailor, two of USS Houston survivors burned. On 17 October she was back with the carrier force, supporting the Leyte landings. The Essex group next raided the Visayan airfields and searched for Japanese naval forces reported approaching.

There was a massive air attack on 24 October, on getting htough and ropping its bomb on the USS Princeton (eventually lost but assisted by USS Birmingham). North of Luzon the decoy carrier force was spotted, ptompted the departur of the 5th fleet and Santa Fe was part of a battle group of six battleships and seven cruisers. Later they fell on the forces that swept through San Bernardino Strait. Four cruisers of CruDiv 13 (its commander raised his mark on USS Santa Fe) went north and catched previously damaged ships by air attack, finishing off the CV IJN Chiyoda, destroyer Hatsuzuki (lefotover of the Battle off Cape Engaño). Santa Fe was back with the carriers and to Ulithi on 30 October.

The Essex group was diverted en route to Manus to the Philippines because of another report, later proved false. Santa Fe’s group hit Manila (5–6 November 1944), repelling a kamikaze attack. During their resplenishement at Ulithi the cruisers were attacked by midget submarines. USS Mississinewa was sunk, some survivors later picke dup by Santa Fe’s floatplanes. The Essex group was back in action on 22 November, until 1 December in the Philippines. They supported newt the the Mindoro landings but the whole fleet was hit by the Typhoon Cobra, which sank three destroyers, on 18–19 December.

USS Santa Fe’s bow at high angle in December 1944, Typhoon Cobra

On 30 December 1944, the Essex group raided Formosa and Okinawa (3–4 January 1945), then Luzon, Formosa again and the South China Sea (Indochina coast, China coast, Formosa again (21 January), and Okinawa before resplenishment in Ulithi. Next USS Santa Fe was reaffected to the USS Yorktown(ii) group on 10 February. On 16–17 February she covered the first raids around Tokyo. Santa Fe was detached on 18 February to shell Iwo Jima (19-21), notably trying to destroy batteries on Mount Suribachi and firing illumination shells at night. She was back to protect the carriers of another Tokyo raid on 25 February.

On 14 March, she joined the USS Hancock group, attacking Kyūshū (18 March), Kure and Kobe. She witnessed the Franklin’s agony, and maneuvered alongside the crippled carrier to rescue survivors and fight fires with her pumps, still at safe distance. For nearly three hours she rescured 833 survivors and help mastering major fires, while USS Pittsburgh took her in tow to Ulithi, Santa Fe staying in sclose escort. On 27 March she escorted her to Pearl Harbor, receiving a Navy Unit Commendation for her assistance: Captain Harold C. Fitz was awarded the Navy Cross, three sailors Silver Stars.

To this occasion the tired, but not battered cruiser was sent for an Overhaul at San Pedro until 14 July 1945. Back to Pearl Harbor on 1 August she departed on 12 August with USS Antietam and USS Birmingham, to attack Wake but the raid was canceled on 15 August as Japan capitulation was known. Instead they headed for Eniwetok and Okinawa, Buckner Bay (26 August) before departing for Sasebo (20 September). In October and until 10 November, she covered the forces occupying the northern Honshū and Hokkaidō and made two “Magic Carpet” trips from Saipan, Guam, and Truk. Her last voyage ended on 25 January 1946 at Bremerton. She was decommissioned on 29 October and preserved in the US Pacific Reserve Fleet, but struck on 1 March 1959, sokd for BU. For her service she earned 13 battle stars.

USS Birmingham (CL-62)

USS Birmingham (CL-62)

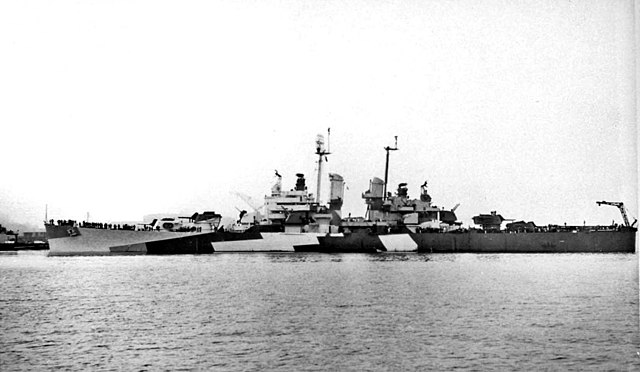

USS Birmingham off Mare Island, and her first repairs ready to join the fray again on 7 February 1944

Following her shakedown cruise, USS Birmingham was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet and departed Norfolk on 7 June 1943 for the Mediterranean front, starting with providing gunfire support for the invasion of Sicily on 10–26 July 1943. Back home on 8 August, she was sent to the Pacific Fleet, making it in Pearl Harbor on 6 September 1943. Son, she joined like most of her sister ships the fast carrier task force screen created by CVLs base don the same hulls.

She took part in the raids on Tarawa on 18 September 1943, Wake on 5–6 October, took part in the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay with Cleveland, Columbia, Montpelier and Denver. Her first major action while her AA gunners also claimed their first four enemy Japanese aircraft. During one such attack she was hit with two bombs and a torpedo and casualties included two killed and 34 wounded. She retired for repairs and kept out the following night battle that followed. USS Birmingham was back to Mare Island NyD for repairs, until 18 February 1944 when she was assigned to Task Force 58 and soon took part in the Battle of Saipan on 14 June – 4 August.

She was also involved in the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 Jun, the Battle of Tinian on 20 July until 1 August, the Battle of Guam on 21 July, the Philippine Islands raids on 9–24 Septemberbefore being assigned to TF 38. She participated in the Okinawa raid on 10 October and strikes on northern Luzon and Formosa until 19 October followed by the Battle of Leyte Gulf (24 October). At this occasion, she tried to help the best she could the crippled USS Princeton, famously almost berthed alongside to help rescure survivors and combat fires. However she suffered great topside damage as multiple explosions rocked the aircraft carrier. In all, 239 died, 408 were wounded, plus four missing. USS Birmingham, crippled herself critically was to be retired, heading to Mare Island NyD. Extensive repairs lasted from November 1944 to January 1945.

She was back in the Pacific in time to supported the battle of Iwo Jima on 4–5 March 1945, assigned later to joined Task Force 54 deployed in the invasion of Okinawa berween 25 March and 5 May 1945. On 4 May 1945 after fending off three Kamikaze attacks, the unlucky cruiser was damaged when one kamikaze hit her forward section, which caused a detonation killing 47, 81 wounded and 4 missing. She returned under escort to Pearl Harbor, with repairs starting on 28 May and completed on 1st August. By the time she gained quite a reputation, but joined the 5th Fleet still operating off Okinawa on 26 August.

USS Birmingham comes alongside the burning USS Princeton to help, in denial of her own safety, the most courageous and dramatic event for the whole Cleveland class.

The was war had ended since almost a week and she stayed to cover convoys bound to mainland Japan, proceeding with the occupation. In November 1945 however steamed to Brisbane in Australia and visited other ports, notably Melbourne on 8 November 1945. Back to San Francisco on 22 March 1946 she was decommissioned, placed in prolongated reserve on 2 January 1947. The most batterred cruiser of the class certainly was not to be recommissioned and indeed she was stricken from the Register on 1 March 1959, scrapped at Long Beach. She won 8 battle stars for her service and would have gained more if not a “magnet” for enemy ordnance, with long repair intervals.

USS Mobile (CL-63)

USS Mobile (CL-63)

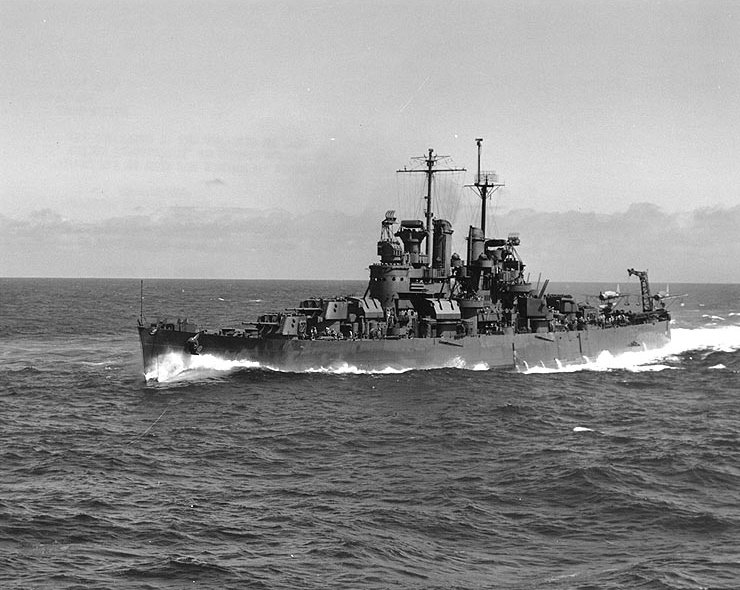

USS Mobile underway in the Pacific Ocean, October 1943.

An early Cleveland class ship, USS Mobile was commissioned on 24 March 1943, with Captain Charles J. Wheeler in command. Following a Chesapeake Bay shakedown cruiser and brief training to Casco Bay, she departed for the Pacific, arriving Pearl Harbor on 23 July 1943 for a month of further training. On 22 August, she was assined to Task Force 15 raiding Marcus Island, on 31 August. She made two other fast carrier raids from Hawaii and joined the 5th Fleet deployed in the Gilberts islands, still screening the CVLs of TF 15 falling on Tarawa Atoll (18 September) and TF 14 on Wake (5–6 October). On the 21 she joined Task Group 53.3 and on 8 November operated off Bougainville Island and later was based at Espiritu Santo, from which she joined TG 53.7 for the attack on Tarawa and Betio (20–28), remaining in the for close support. On 1st December, USS Mobile was ordered to join TF 50 of the Fast Carrier Forces, later conglomerated as TF 38/58. She covered actions at Kwajalein and Wotje before a refill at Pearl Harbor and San Diego, assigned to escort duty for the 5th Fleet on 29 December 1943.

The new year she sailed mi-dJanuary with TG 53.5 back to the Marshalls and the 29 joined CruDiv 13 shelling Wotje and back to Kwajalein. Until 6 February she operated off Roi-Namur and refilled in Majuro latere joining TF 58.

The fast carrier forces she escorted prevented any rinforcement of bypassed small enemy-held atolls and islands, isolate those to be captured. After the occupation of Eniwetok and encirclement of Rabaul, TF 58 headed for the Carolines and operations started on 16–17 February on Truk, before heading northwest to the Mariana for striked on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam until 21–22 February. TG 58.1 became TG 36.1 on 12 March and three days later, covered the Marines assaulting Emirau on 20 March 1944. Until 3 April Palaus, Yap, and Woleai followed, with the usual respite at Majuro. Next were Aitape, Humboldt Bay, Tanah Merah Bay (New Guinea Camoaign) then attacks on Wakde and Sawar Airfield (21–22 April) for the Battle of Hollandia. After a new raid on Truk and Satawan, Ponape followed on 1st May.

On 11 June, USS Mobile operated in the Marianas for more strikes on Saipan, Tinian, Guam, and Rota, Volcano and Bonin Islands to isolate the archipelago.On 19 June she took part in the first Battle of the Philippine Sea. USS Mobile afterwards launched everyday her OS2U Kingfishers for antisubmarine or SAR missions. On 23 June, the carrier force retired to Pagan Island for new strikes. On 30 June, they headed for new raids on Bonin and Volcano Islands and back to the Marianas campaign, Guam, Rota and on 23 July, raids on the Western Carolines, Yap, Ulithi, and Fais, Palaus and back to Saipan on 2 August 1944.

New raids followed on the Bonin and Volcano Islands, CruDiv 13 and Destroyer DesDiv 46 were detached to search for Japanese traffic in the Chichi Jima area. USS Mobile participated in the sinking of a destroyer and large cargo vessel. The shellling of Chichi Jima followed. Her unit was renamed TG 38.3 and was back in the Palau Islands on 6-8 September before a raid to Mindanao and Visayas, the Peleliu and Angaur, and back to Philippines, hitting the Manila area, and Visayas again.

After the usual resuply at Ulithi operations on the Ryūkyūs islands followed, while USS Mobile was detached with USS Gatling and Cotten to destroy two located enemy ships some 30 miles (48 km) away and indeed sank a large cargo ship, while the other already was sunk by aviation. Back with their unit they raided Formosa and the Pescadores. On 13 October they escorted the damaged cruisers Canberra and Houston (“Cripple Division 1”) back to safety. USS Mobile was back to TG 38.3 on 17 October 1944, and after striked on the Visayas and southern Luzon a masive plane attack from Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet commenced and during the ensuing battle of Leyte gulf, USS Mobile protected USS Princeton. Next she fought the Battle off Cape Engaño and aided in sinking IJN Chiyoda and Hatsuzuki. She went on operating in the Philippine until retiring at Ulithi and sailing again on 26 December for the west coast, Terminal Island in California for a well-deserved overhaul and long crew leave.

USS Mobile received alteration and modernizaztion, notably for her radar and AA before heading back to Ulithi on 29 March 1945, attached to Task Force 54 and prepared for the assault on Okinawa, arriving on 3 April. She provided fire support and AA cover, her own planes providing also antisubmarine patrols and tasked to spot and destroy Shinyo suicide boats. By the fall of May 1945, USS Mobile was reassigned to TG 95.7 and complete the Philippine training group, in action until August. On 20 August, she sailed San Pedro Bay for Okinawa and Japan, helping the occupation and making POW transport home runs to San Diego. She made another “Magic Carpet” run until joining Puget Sound for inactivation, decommissioned on 9 May 1947, Reserve Fleet until 1 March 1959, stricken and sold for BU. She won 11 battle stars for her service.

USS Vincennes (CL-64)

USS Vincennes (CL-64)

USS Vincennes underway in San Francisco Bay 29 August 1945

USS Vincennes(ii) – the first was a New Orleans clas cruiser sunk at the infamous “ironbottom sound” during a famous night action in 1942 – was commissioned on 21 January 1944 with Capt. Arthur D. Brown in command. By late February 1944 she made her sea trials and her shakedown cruise in the British West Indies and back followed by training in the Chesapeake Bay area, and Gulf of Paria near Trinidad. She became flagship for Commander, Cruiser Division (CruDiv) 14, Rear Admiral Wilder D. Baker. On 16 April she departed with USS Miami and Houston Boston from Boston, heading for Panama and Pearl Harbor on 6 May 1944. After more training, CruDiv 14 and USS Vincennes hosted Admiral Chester W. Nimitz on board. On 24 May the division left Pearl Harbor to Majuro (Marshall) and Task Force 58 (Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher) for the Mariana campaign.