Light, Heavy and Specialized Imperial Japanese Cruisers of WW2.

WW2 IJN Cruisers:

Furutaka class | Aoba class | Nachi class | Takao class | Mogami class | Tone classTenryu class | Kuma class | Nagara class | Sendai class | Katori class | Agano class | Oyodo

Tsushima | Asama | Tokiwa | Yakumo | Izumo | Kasuga | Hirado

The fleet’s spearhead

In December 1941, the most valuable asset of the Imperial Japanese Navy, after the aircraft carriers of the combined 1st air force (Kido Butai), were its Cruisers. Indeed, contrary to the older, slower battleships, cruisers were built along along the interwar and perfected until stopped during the war itself, when fewer resources were available.

All in all, despite having formidable offensive assets, IJN cruisers performed actions in dispersed order depending of their age and capabilities. The real spearheading ones were only twelve: The four Myoko, the four Takao and the four Mogami. They were the most recent, best armed, largest of the IJN and indeed took part in the most offensive fleet units of WW2 in the Pacific.

The older 1920s vessels of the Tenryū, Kuma, Nagara and Sendai classes were stil transitional WWI designs which were arguably obsolete in 1941 and were sent to aid eny convoy which needed protection; thus logically sidelined and never used in first line units. The experimental Yubari followed that path, but the more potent Furutaka and Aoba classes at least saw more frontline action. Wartime vessels such as the Tone were in effect the last “heavies”, joining the pack, but the four Katori were essentially schoolship with little military value, and the four Agano were rather more escorts than frontline cruisers.

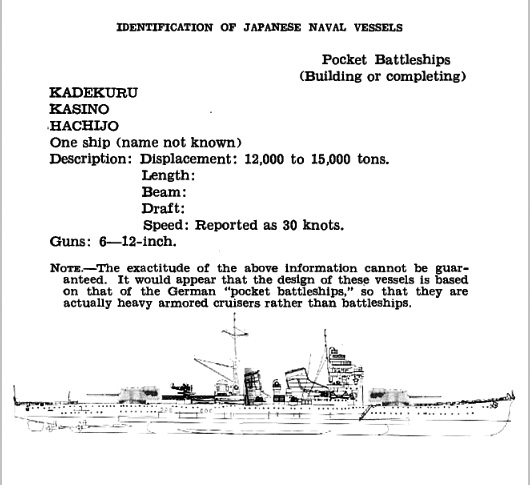

Special mention to the never-built B-64 though. These “large cruisers” to keep the US denomination adopted for their Alaska class, proven to be an imaginary threat were indeed planned by the IJN high command planning the end of peactime limitation, as a “cruiser hunter”.

Legacy: WW1 cruisers still in service

In December 1941 there were still a surprising number of WW1 vessels still listed as active, dating back from before the great war. On paper, this was even impressive and only comparable to the Royal navy’s C and D class cruisers. There were of course those of the 1918 plan which were the best known, the oldest of which being the two Tenryu class launched in 1918, but the following Kuma and Nagara (11 cruisers) designed as destroyers leaders were completed at the time the Washington treaty was signed. They are seen in the later part of this article;

As for older cruisers, the list was comprehensive, but the Washington treaty forced their scrapping and/or conversion to other roles. Not willing to scrap what for them was perfectly valid ships, paid a high price compared to the country’s GDP, they were maintained in service by using the exemptions of the treaty: Training and Miscellaneous ships (like minelayers).

And thus a remarkable number of these “antiques” in 1942 were still proudly flying the hinomaru.

Battlecruisers:

If the four Kongo class were the last and best known, reconstructed twice in the interwar and gradually converted as fast battleships and thus not counted here. The older Kasuga class, Ikoma and Kurama class were classed as armoured cruisers (from 1921 for the latter).

Armoured Cruisers:

Asama class: Launched 1898, Asama was converted as a training ship in 1937 (BU 1947) and Tokiwa as a minelayer by 1928.

Yakumo: Launched 1899, she became a coast defence ship (full detail later)

Adzuma: Launched 1899, was also converted as a coast defence ship, and doubled as trainign ship as Yakumo.

Izumo class: Izumo and Yakumo, Launched 1900 were 9750t ships with the same status: TS in peacetime, coast defence ship in wartime.

Kasuga class: Kasuga and Nisshin were “1st rate cruisers” and used as training ships from 1927 as new vessels took their place. Nisshin was expended as target in 1936 but Kasuga only retired in 1942. She was sunk in Kure the same day as the two Izumo in July 1945 (see later).

Kurama class: The former battlecruisers, reclassed in 1921 as “1st rate cruisers” were considered during the Washington treaty too valuable to keep even as training ships. They were ordered to be scrapped, which was done in 1923, to quite some frustration from the naval staff.

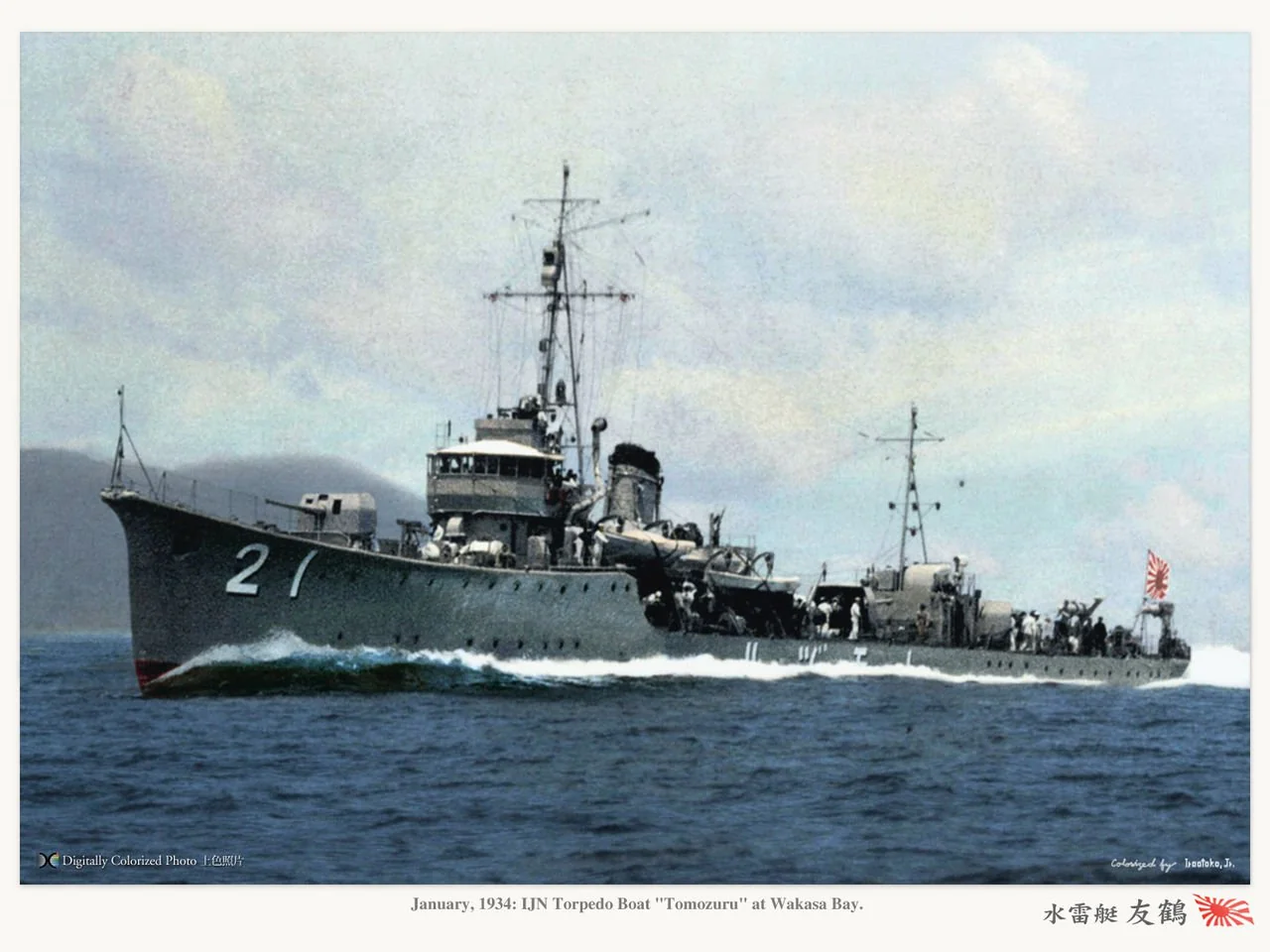

The IJN Yubari (here colorized by irootoko Jr) at Sasebo just completed in 1923. This strange prototype light cruiser marked the rebirth of the IJN after the Washington treaty. She really was built not to fill a precise requirement (but of a fleet scout), but merely to test new weight-saving construction techniques will would allow the IJN naval staff to get “more with less”, doing better than the (US-British) competition in armament on smaller tonnages. The Tomozuru and 4th fleet incidents would shatter these illusions.

Protected Cruisers:

Smaller and of an earlier design these vessels were improper for training ship conversion. Re-rated as 2nd class cruisers in 1921, their career was shortened, except for three.

Chitose class: This 4760t, 1898 ship was discarded in 1928, sunk as target 1931

Niitaka class: Niitaka and Tokiwa were 1902, 3,366 tons cruisers no longer active: The first was lost in a typhoon in 1922 and the second hulked in 1930, sunk in 1944.

Tone: This 1904 4,100 ton cruiser was discarded in 1931, sunk as target in 1933.

Chikuma class:

These had a more interesting career. Still “young” in 1922, they were reboilered and rearmed to extend their useful life. Chikuma due to tonnage limits was discarded in 1931, Hirado in 1939 and Yahagi hulked in 1940 so they took no part in the hostilities, but both survived WW2 nevertheless.

Postwar cruiser development: Yuzuru Hiraga’s design school

Baron Yuzuru Hiraga was one of the most influential (if not the most) of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the interwar. Born in Tokyo, grewing up in Yokosuka, Kanagawa (his family was from Hiroshima) he graduated from Hibiya High School and was in the engineering department of the Tokyo Imperial Universityby 1898. As specialist in marine engineering. Draft in the IJN while still being a studen in 1899 he graduated in 1901 as sub-lieutenant and started working at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal a design engineer.

Baron Yuzuru Hiraga was one of the most influential (if not the most) of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the interwar. Born in Tokyo, grewing up in Yokosuka, Kanagawa (his family was from Hiroshima) he graduated from Hibiya High School and was in the engineering department of the Tokyo Imperial Universityby 1898. As specialist in marine engineering. Draft in the IJN while still being a studen in 1899 he graduated in 1901 as sub-lieutenant and started working at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal a design engineer.

A lieutenant on 28 September 1903 she was transferred to Kure Naval Arsenal in 1905 just as the Russo-Japanese War started. He was soon sent to the allied United Kingdom for extra studies of British designs, leaving Yokohama for the Pacific in January and also visiting the United States west to east, and crossing the Atlantic Ocean to London in April 1905. By October, he became a member of the Royal Naval College in Greenwich, having the most immediate immersion into the latest techniques in warship design. Graduated from there by June 1908 he spent six months touring various shipyards in France and Italy for an extra insight,nwriting many reports befire arriving in 1908 back in Japan. By September her became professor of engineering, at Tokyo Imperial University, promoted to lieutenant-commander on 1 October.

In 1912 he was part of the design team in charge of the design for the battleship Yamashiro (Fuso class) and conversion of Hiei from battlecruiser into a battleship. He also worked for the Kaba-class destroyers designed and became commander on 1 December. In 1913 he became Director of Shipyards for the Imperial Japanese Navy, a very coveted title comparable to CNO, and awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure on 28 November, and a new time by November 1915 as he managed to speed up the efficiency of Japanese shipyards under heavy strain to provide ships to the allies (and another award on 25 February 1926).

In 1916 he was the chief engineering director behind the “Eight-eight fleet program”. He focused on a new breed of high speed battleships and cruisers. On 1st April 1917, now ranked captain and rear admiral from June 1922 he closely followed discussions leading to the Washington treaty with dread. On 7 November 1920 he was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun for his innovative deisgn for the cruiser Yubari, his first really 100% own project.

He was soon appointed a technical advisor to the Japanese delegation sent to the Washington Naval Conference until August 1924. Back home he was promoted to the head of the Imperial Japanese Navy Technical Department and vice admiral in 1926.

He assembled his own design tem around picked-up engineers to create a new fleet within the Washington Naval Treaty boundaries, severely restricting Japanese designs and forcing him to take many innovative design approaches (mostly saving weight) for cruisers and destroyers. His shiped became extraordinarily powerful for their tonnage, using assembly and construction techniques among the most advanced at the time. His famous work was to bring about heavy cruiser better armed than the competition while still well below the 10,000 tons limit (about 8,500 to 9,000 to plan for future additions).

However perhaps enboldened by these enegineeing feats, the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff often ordered that more weaponry despite Hiraga’s objections over strength and stability. The Mogami-class cruisers were perhaps the most striking exampkle with no less than 15 6.1-inch guns over a 8,500 tons tonnage. In fact these feats only came through “generous” underestimation of their true displacement as well as sacrificed in hull strenght and stability as shown by the Tomozuru incident. By 1929, his last project, the planned Kii-class battleship (never completed) was ended abruplty by the naval staff and retired from active military service in 1930, now just an advisor for Mitsubishi shipyards, in part tired and disgruntled by the attitude of the Navy.

In April 1934 despite all his previous warnings he was part of a board of inquiry after the Tomozuru Incident. His reputation suffered even further in the Fourth Fleet Incident, forcing the Fubuki-class he designed for a rebuilt after a typhoon. Nevertheless he managed to clearly establish his own warnings and was eventually released, and even appointed in the design team in charge of the Yamato.

In December 1938 he became President of the Tokyo Imperial University and conducted a “Purge” of those having liberal political doctrines. On February 17, 1943, Hiraga died at Tokyo University Hospital after a pneumonia, posthumously awarded with the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun and kazoku peerage as baron. His grave is now located at the Tama Reien in Fuchū, Tokyo.

The 1934 Tomozuru incident and consequences

As seen above, both this incident, compounded with the 4th fleet typhoon drama, was a incident which implied a torpedo-boat of the Chidori class. Japan like Italy and Germany looked at TBs as a way to create more warship tonnage out of the authorized destroyer tonnage. They could be useful notably in the confines of the China sea, Japan sea, Jorea sea or Pacific islands chains. But industrial limitations only generated two classes, the four Tomozuru (launched 1933) and eight Oroti class (1935). Soon the naval staff priorities changed for escorts, like the Shimushu class (launched 1939) followed by many more.

As for the incident, IJN Tomozuru incident happened soon after the ship entered service, on 24 February 1934. She joined the 21st Torpedo Flotilla at Sasebo and on 12 March 1934, departed for a night torpedo exercise with the IJN Tatsuta and he sister ship Chidori, marred at 03:25 by stormy weather and ordered to return to base. However soon radio contact was lost and her lights disappeared at 04:12, a signal she had probably capsized. A rescue started ten hours later, the capsized hull spotted drifting but there was none to save, 100 of her crew was lost in the rapid capsizing. She was was towed by Tatsuta to Sasebo for an investigation.

After weeks of intensive scrutiny it was established instability was the cause, as they played with the Washington treaty of 600 ton, but were given the armement of a 1,200 tons destroyer essentially. She received under Hiraga direction a lighter construction manking her top heavy. Their unbalance centre of gravity proved even higher than feared and efforts made to remedy it, as shown by her sea trials, by adding hull bulges on Chidori and applied to Tomozuru, and her sisters, with the added benefit of filling these with extra oil (so better range). However the incident happened when she was very low on fuel/water that would have used until then as ballast, hle having full ammunition load. The combination with what was perhaps a near-rogue or very high wave taken from a bad angle was probably the finishing blow. It was estimated that in her condition the situation was worse than on her sea trials.

Do note that the USN Farragut class lost two destroyers in a storm for the same reasons in 1944. They were less top heavy afte their partial reconstruction, but happened to meet the exact same conditions.

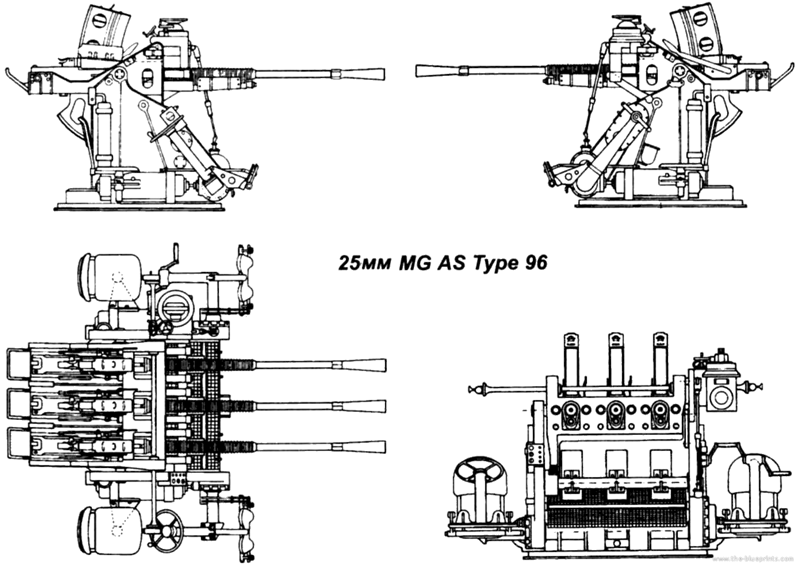

Whatever the details, the consequences were dramatic and far reaching. An immense cross-fleet investigation of all ships designed after 1922 was undertook, in search or similar design weaknesses. Recalculations (more detailed and realistic) were made with simulations of similar conditions which led to a rebuilting of the following ships due to their low metacentric height: The Aircraft carrier Ryūjō, the Mogami class cruisers, Fubuki, Akatsuki and Hatsuharu classes destroyers, submarine tender Taigei Minelayer of the Yaeyama, Shirataka, Itsukushima, Natsushima, Tsubame classes, minesweepers of the No.1 and No.13 classes and existing subchasers. The total cost was worth one or two battleships and had grave financial consequences for the IJN budget planification, delaying several program and shutting down projects.

It completely changed the naval staff initial assumptions over stability issues, and led to valuable lessons for future designs across the board. Superstructures were reduced, bulges added, over deck structures lightened, ammunition dug below decks, and armament downgraded in 1934-35. The Mogami-class cruisers were probably the most heavily modified of all these ships, at again, a cost superior to the construction of an extra cruiser.

The Tomozuru affair will bounce back with the loss of several Fubuki class in the 4th fleet incident, in a typhoon, for the same causes.

After 1936 no such incident ever occured again as the metacentic height was now one of the master data to put under scrutiny on all designs. Despite of these stability measures, the cruisers in particular were again compromised by the addition of countless AA guns in WW2, but no such capsizing happened ever again.

The 4th Fleet Incident

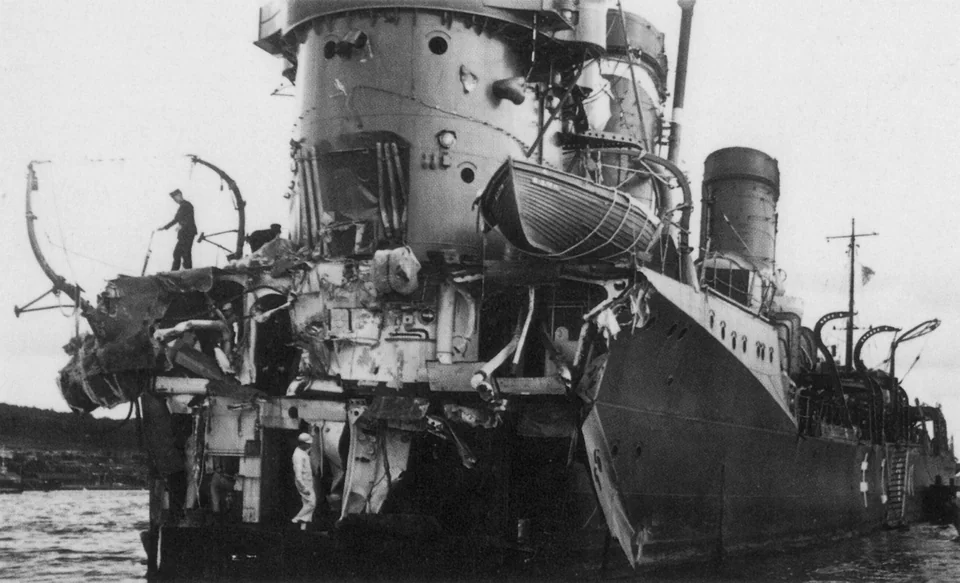

Japanese destroyer Hatsuyuki (Fubuki class) heavily damaged after Fourth Fleet Incident – 1935 (reddit)

On September 26, 1935, offshore east of Sanriku in the Pacific Ocean, the Japanese 4th Fleet while in training encountered an abnormal typhoon, 250 miles east of Sanriku coast, which damaged many vessels very seriously and also caused human losses. Bows were cut off from IJN Hatsuyuki, Yugiri, the new Japanese “Special-Class” Destroyers (serie started by IJN Fubuki). Many other ships were damaged or flooded (like Ryujo).

Waves far larger than first expected were the primary cause. But it was serious enough to be investigated, and new facts discovered. The main consequence, was a reinforcement of many ships across the board. The even confirmed tendencies in naval construction were risky at best, after the Tomozuru capsizing (which showed shortcomings in stability), and highlighted this time structural weaknesses across the board.

This day, the Blue Fleet (1st and 2nd fleets) was going agains the Red Fleet (4th Fleet, assembled temporarily). This large scame fleet manoeuver started in July, until late September (as planned). The rebuilt Yamashiro, Haruna, the Mogami Class and the Hatsuharu Class took part for the first time and much was awaited from their performances.

By late September, the Red Fleet crossed the Tsugaru Straits eastwards, and the Red fleet was expected east of Honshu Island to meet the Blue fleet. Weather degraded very fast from 14:00 on September 26, as a typhoon grew out of proportions, catching the fleet completely off-guard. The first largest waves simply knocked off the bridges of Hatsuyuki and Yugiri, the one of Mutsu was smashed, the front side Ryujo’s bridge too, and huge flooding followed, while IJN Hosho plunged so deep had flight deck was completely overwhelmed by huge waves, which crashed her deck and leaked into the hangar; All ships present suffered slight or heavy damage.

The Red fleet abandoned its maneuver and gathered off Shinagawa, Tokyo bay. On October 7 onboard IJN Hiei the staff made a reunion to assess the exercize and overall damage (she was the observing vessel of the maneuver). The incident was judged serious enough that authorities concealed it entirely, put all present sailors to secret, and this happened as Japan withdrew from the London Naval Conference soon after and went even more into secrecy.

Analysts were baffled as it was the first time any ship was so badly damaged by waves since the British destroyer Cobra split in half by 1899. This just confirmed worrying signs after the capsizing of Tomozuru, and put into question the whole Japanese shipbuilding practices. A commission of enquiry was setup in place and led an investigation, (also looking for scapegoats, this was a naval staff one, which deliberately asked engineers for more armament). It was determined first that the Special-Class destroyers. It was decided also to reinforce cruisers, notably those of the Mogami class, and even aircraft carriers. It shows for example that the Ryujo class, built on the below 10,000 tonnes design to go around the Washington treaty limitations (she was not considered as an aircraft carrier) was not a realistic prospect.

Plates that were recuperated and analyzed showed notably for the destroyer, many welding faults (or too weak bonds) and cracks developed after years of vibrations and intensive use. But since thos was merely a political matter, the naval staff looked to blame the shipbuilders and chairman Admiral Kichisaburo, assisted by Vice Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto and Rear Admiral Mineichi Koga. They heared notably Yuzuru Hiraga and his assistants.

On October 21th, 1935, a new special investigative committee for the improvement of the efficiency of naval vessels was established under the lead of Admiral Seizo Kobayashi, which was poised to find the most effective measures to deal with the structural weaknesses observed. These went on for five months and released a very detailed report in April 1936. It was also underlined that vessels appeared heavier than first designed, either when completed and fully loaded, or remarkably heavy after alterations. They established that welded ships proved to have reduced body strength also, and required extra internal bracing, better welding or riveting of some parts. Engineers put to the task found it was not easy to calculate and apply stresses in severe conditions. And the naval staff wanted these reinforcements must affect performance as little as possible. This became rapidly a daunting, hair-splitting and time consuming work and it was felt by some it would endanger National defense at that time. The government wanted to keep costs low, adding more strains in the effort.

Most of the smaller ships went into dock, their plateing and decks stripped and rebuilt, Bridges separated and re-braced. As it appeared welding was overused this immature technology. Also the Design process and construction techniques were reviewed across the board. Critical parts of the hull’s strenght were reevaluated and riveting reappared. They were used for example on Yamato. All these countermeasures efforts of all concerned bore frtui ultimately, with the last ship out of the yards in December 1938 already. They could therefore perform their missions without any further problems afterwards, but this caused immenses delays and extra cost to the fleet as a whole.

Rear Admiral Keiji Fukuda (later promoted to Technical Vice Admiral later) and Prof. Yuzuru Hiraga, assumed most of this daunting work, but this took a strain on the latter’s health, which soon retire from active involvement in naval construction afterwards.

This kind of event was not limited to the IJN however. Famously, the latter “had their revenge” in wartime: The U.S. Navy’s 3rd fleet under the command of Admiral Halsey, was heavily damaged by two typhoons during the Pacific War. Notably many ships were damaged, including some of the Essex-class carriers had their flight decks mushed and collapsed. On December 18th, 1944 in the Philippine sea, 3 destroyers capsized and sank, 18 vessels were badly damaged, 9 were slightly damaged, 183 aircrafts, 700 lives lost. It happened again off Kyushu on June 4th and 5th, 1945. This time, four battleships, two aircraft carriers, two light aircraft carriers, four escort carriers, three heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and 17 other vessels were seriously damaged, most of the aircraft deck park thrown overboard or destroyed by giant waves. There too, draw consequences for US naval shipbuilding, notably by avoiding stability issues and oil-tanks consumption and supply procedures (this caused the loss of three destroyers in the first case). The Essex-class for example received “typhoon bows” when possible and the Midway class had them installed while in completion. Would this have changed things if the US intel had the knowledge of the 1935 incident ? Debate is launched.

Characteristics of IJN Cruisers

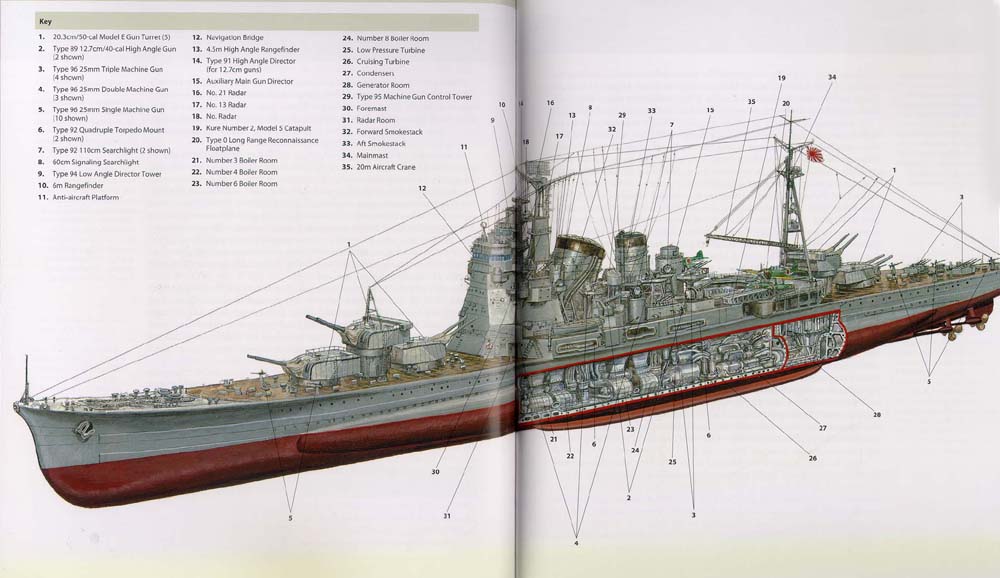

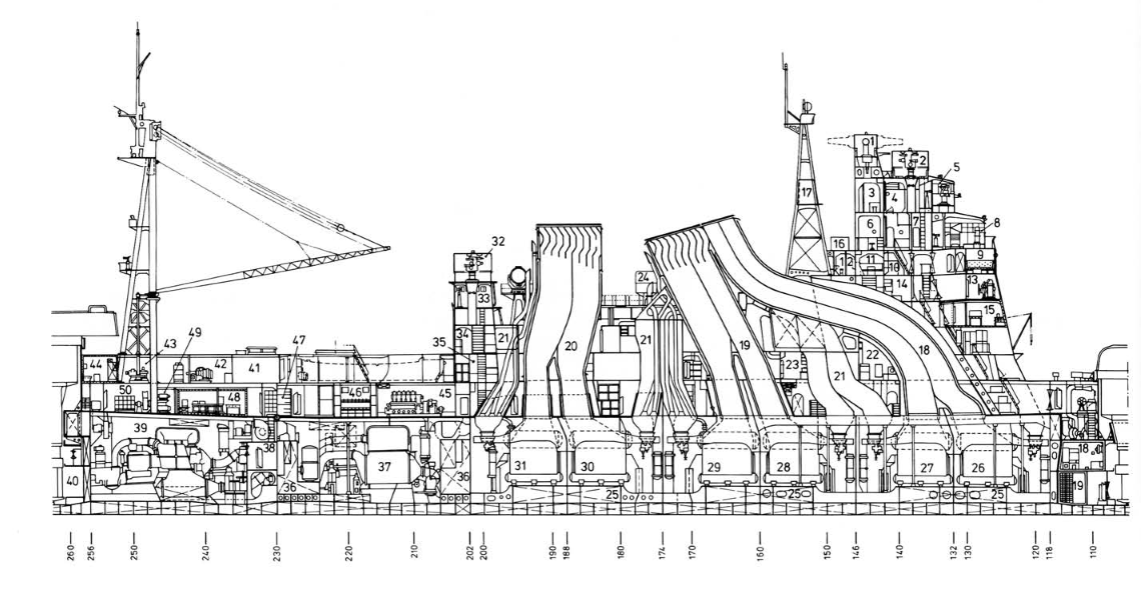

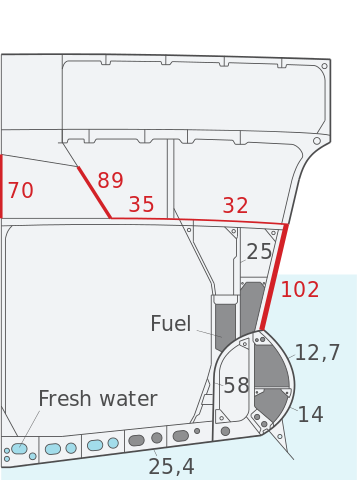

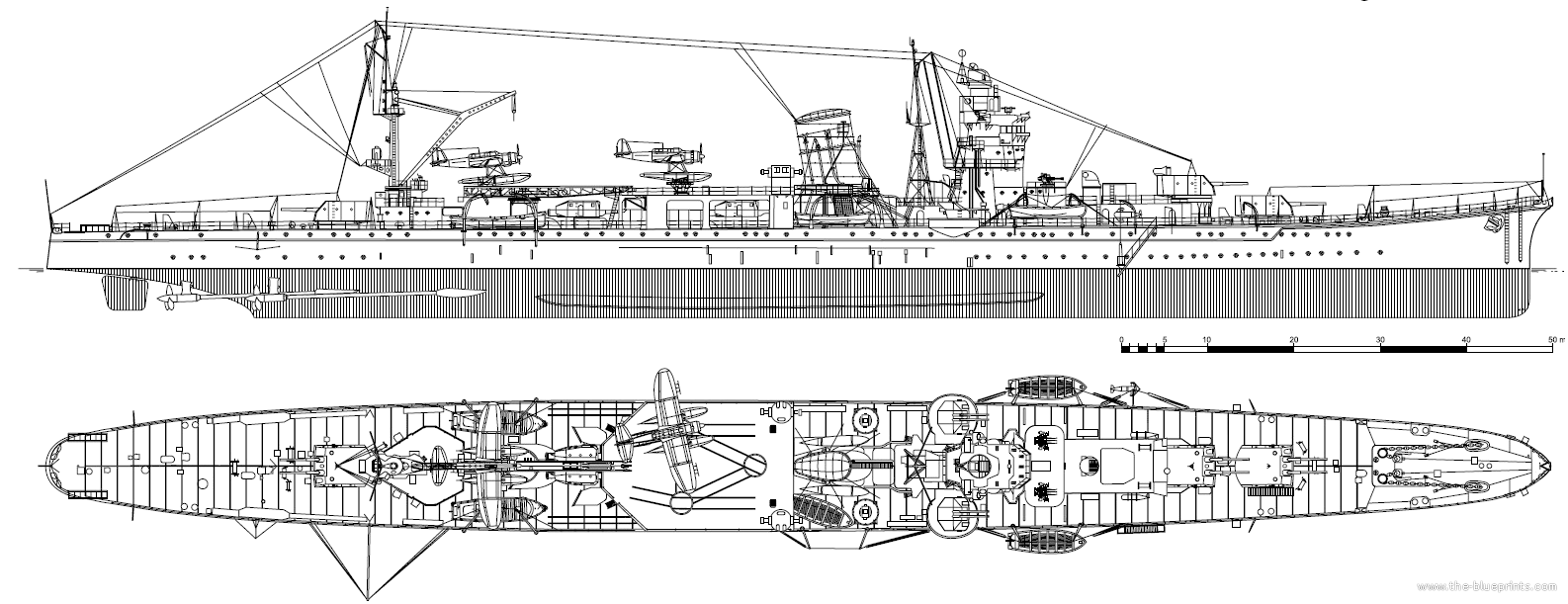

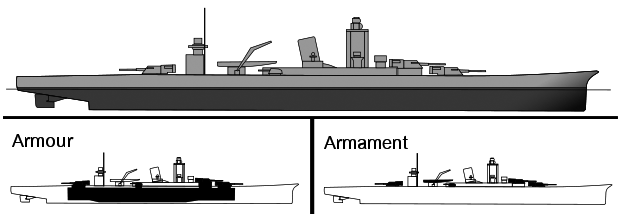

Cutaway of the Nachi class from “Imperial Japanese Navy Heavy Cruisers 1941–45: 176 (New Vanguard, 2011) by Mark Stille (Author), Paul Wright (Illustrator).

As already seen above through Hiraga’s design philosophy and incidents, the designs of early IJN cruisers (Yubari was a pre-Washington design, which stayed experimental, only to test new construction techniques) proceeded with two main concerns in mind: The heaviest armament possible, on the lighter displacement possible, and keeping speed at the top end of their class. Protection was not secondary. These early cruisers were not “paper cruisers” such as those French and Italians of the early 1920s. But there were clearly three eras to separate:

-The WWI program cruisers (Tenryu, the Kuma, Nagara and Sendai classes): These were scout cruisers, armed with single-mount pieces, at best with 2.5 in of armour on a partial belt.

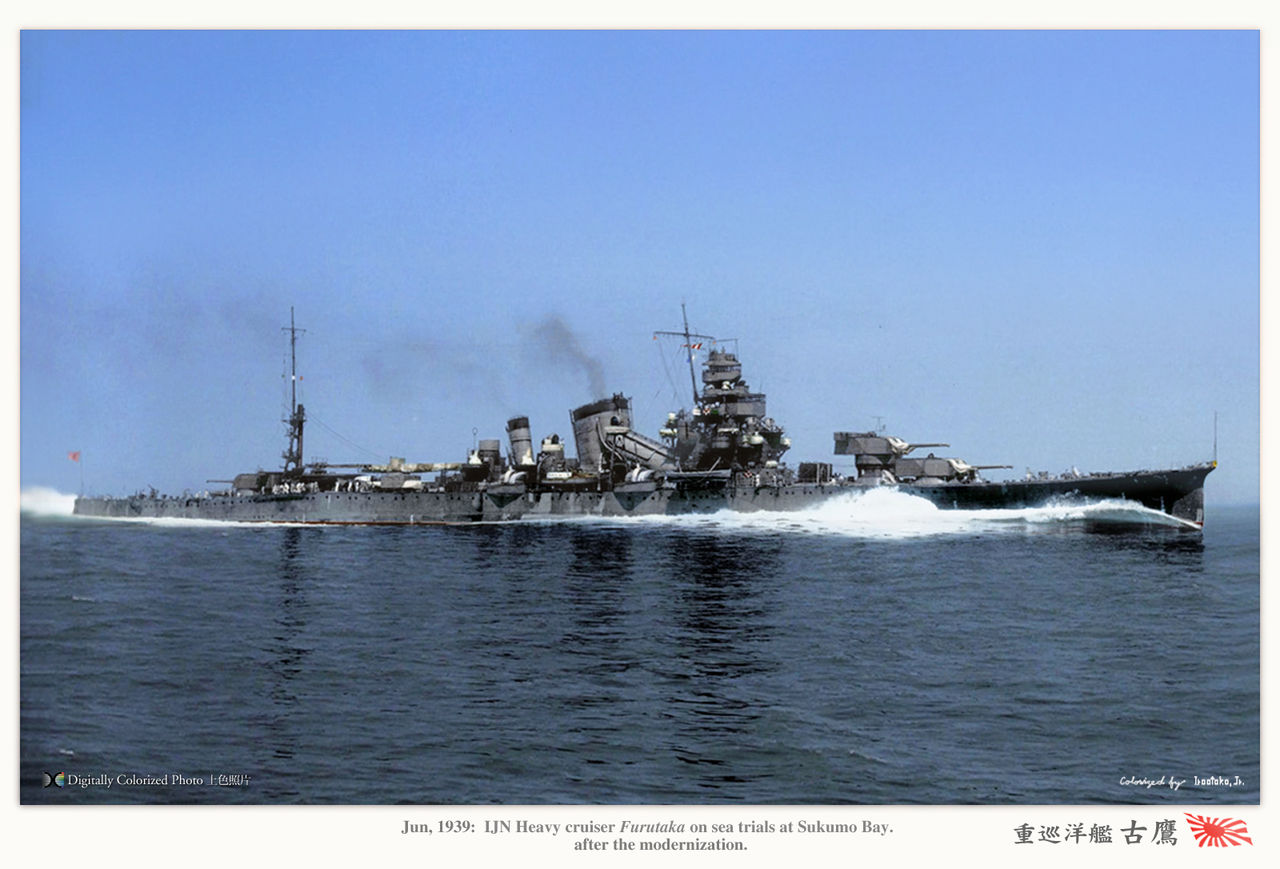

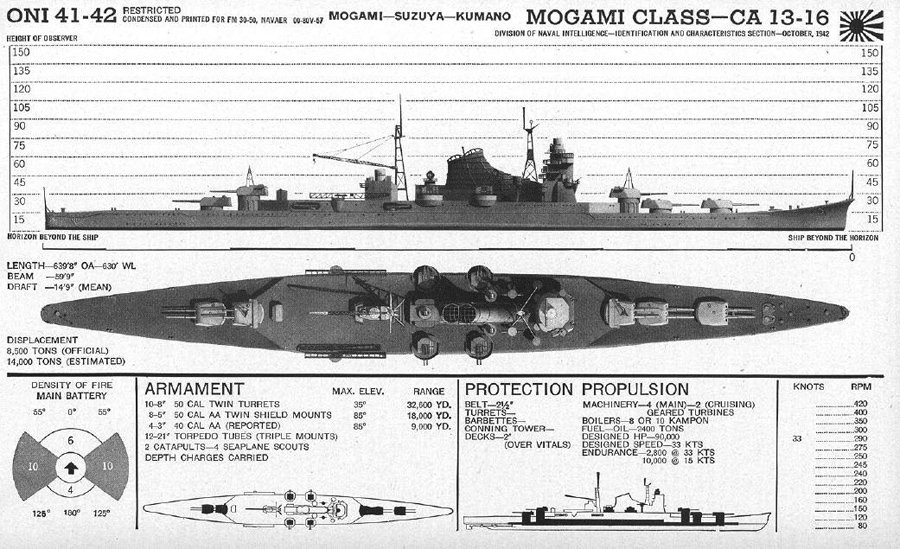

-The post-Washington design cruisers: This included the new generation Furutaka and Aboa (4 ships), brand new designs based on the experience of Yubari but with heavy artillery of 8-in guns as in all navies of the time. And this included the Nachi class (designed in 1923), Takao class (designed in 1926), just much larger and better armed, and the Mogami class (designed in 1930), but revised after the London Treaty with 6-in guns.

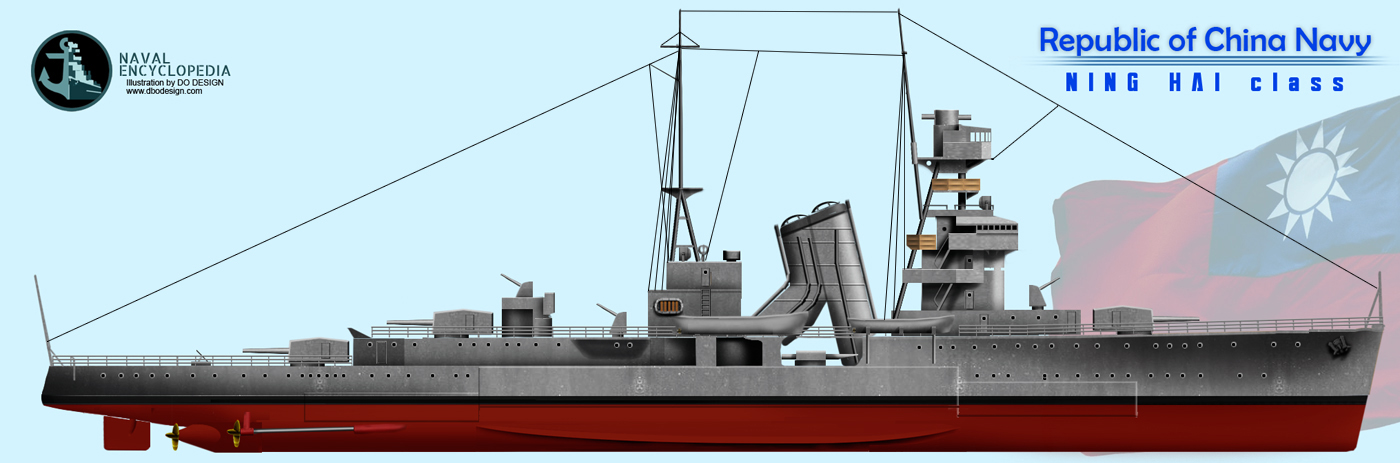

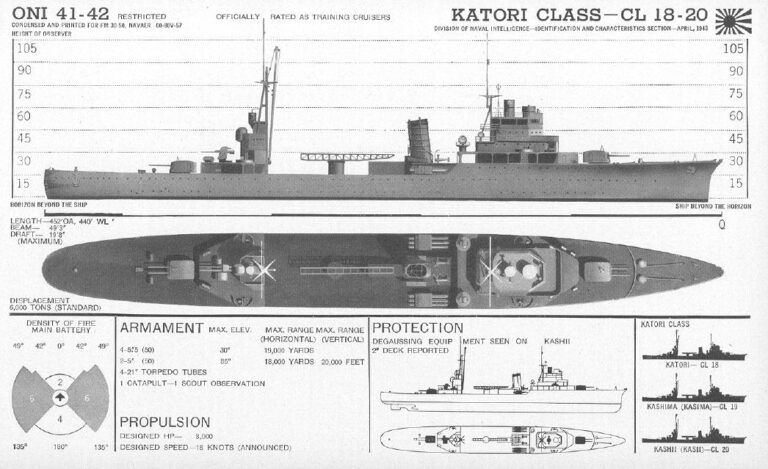

-The Post-Tomozuru incident (1934): The Tone class (design revised in 1934 just after they were laid down), Katori class (which were school cruisers) and the WW2 Agano and Oyodo class intended as replacement for the WWI program cruisers.

The appreciation of design specifics for comparisons only concerned largely the Nachi, Takao and Mogami. Indeed the Furutaka and Aoba were merely “light cruiser” by displacement and an arguably lower armament than contemporary heavy cruisers and can be seen as steps towards the definitive IJN cruiser designs of the interwar, still testing many solutions. They are not representative of the whole picture.

Yubari was a prototype, and the design solutions were mixed with the need of a heavier armament proceeding by steps, single turrets on the Fututaka before rebuilding, and twin turrets with superfiring turrets with the Aoba. It was all-Japanese, since Britain ended its alliance with Japan in 1923. These “test cruisers” paved the way for a much more ambitious design, which was to this time answer to any regular British or US cruiser design of the time. The goal was simple: More guns and more, better torpedoes first and foremost. AA artillery was secondary.

Speed was paramount, and all this was to be done under the 10,000 tonnes limit officially as long as Japanese offices remained open to the west (which was no longer the case when the Yamato class was started). The fact Japan retired from the second London conference made it free to launch several reconstructions (like the Mogami class being the most spectacular) which implied also the Nachi and Takao, and naturally pushed their tonnage well beyond the 10,000 tonnes limit. In WW2 for example, they looked towards 14,600 tonnes or above. The Tone class (launched 1937) was even above treaties from the start, with 11,215 tonnes standard already and up to 15,600 tonnes later in WW2. They all gained bulges and were considerably reinforced structurally.

Armament

Armament-wise, the cruisers went from six 8-in guns (203 mm) on the Furutaka-Aoba, to a staggering ten on the Nachi-Takao-Mogami (the latter before swap to 6-in guns); This made them the most gun-heavy cruisers of the interwar. The closest were the US cruisers adopting triple turrets (for nine guns) on the Northampton, New Orleans, and even the wartime Baltimore class. The European standard was eight guns in two twin turrets. The way to shoehorn a fifth turret however ment some sacrifices.

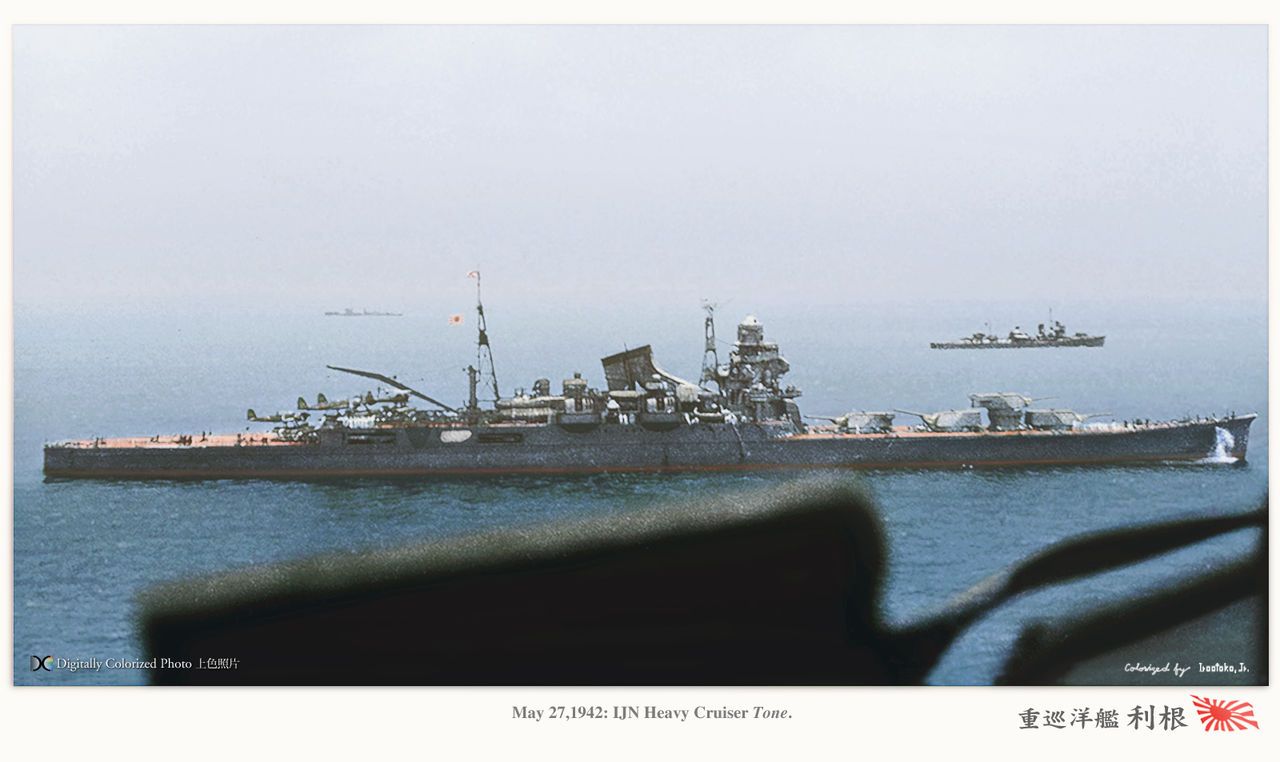

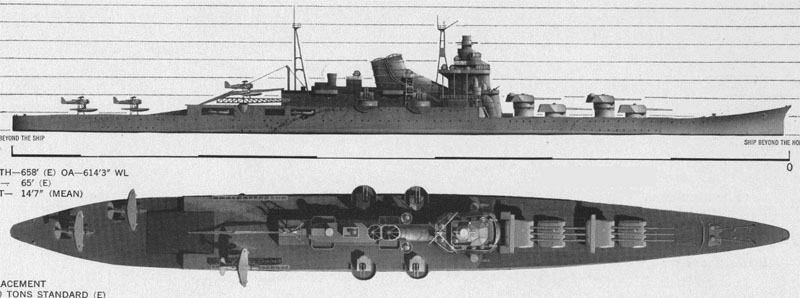

The hull was lenghtened, and the turret N°3 was placed between behind the superfiring N°2, meaning it was facing the bridge and had a more limited arc of fire, only potent in broadsides, but neither in chase or retreat. The mogami improved this as having the N°1 and 2 on the same deck level and N°3 raised on the superstructure, enabling more leeway and a six guns chase fire. The Tone were even more radical with a return to four turrets but all forward, a superfiring pair followed by two deck-level turrets facing the bridge. A unique approach enabling space aft for an air group. Something never seen in any other design worldwide.

The other shining point of the designs, purely out of Japanese newly developed night combat tactics with only cruisers and destroyers, favored an aggressive use of the torpedo. Indeed, from the Furutaka’s originl fixed tubes in pairs were substituted two quadruple banks at deck level after reconstruction, abd same for Aoba. But originally they could fire six torpedoes on either side.

The Nachi adopted these traversing banks early on, in four triple banks inside niches in the superstructure aft.

They thus passed from eight to twelve, six either broadside and reloads. This scheme was repeated on the Takao class (relocated amidships) and Mogami, Tone class as well. Many were later removed to spare weight and add extra AA. As for the light cruisers of the Agano-Oyodo they are to be compared rather to what they replaced. The Kuma-Nagara-Sendai had four twin tubes, four torpedoes on either broadside. The Agano planned as destroyer leaders had two axial quaduple banks (so also eight tubes) like on a destroyer, and this placement enabled more stability and a full broadside, twice the cruisers they replaced. The larger Oyodo due to her role had no TTs at all.

50 caliber 3rd Year Type 20 cm Gun 1 GÔ (No. 1)

This was the official designation for the main guns of the Akagi and Kaga initially, and the cruisers of the Aoba/Furutaka classes, as well as the Myôkô class.

These 17.6 tons (17.9 mt) had a rate of fire of 2 initially (Kaga) and up to 3-5 in the later version. Approximate Barrel Life was 300 rounds and the ships had about 120 rounds in store for each. Range at 45° was 30,620 yards (28,000 m). More

50 caliber 3rd Year Type 20 cm Gun 2 GÔ (No. 2)

The “modern” 203 mm (8 inches) caliber, found on the Takao class. They tried to correct large dispersion patterns, and were fitted on the Takao and Tone classes as well as the rearmed Furutaka, Aoba, Myôkô and Mogami classes as well as the unbuilt Ibuki class. Performances: 3-4 rounds per minute, range 27,340 yards (25,000 m)/30°, 1,247 fps (380 mps) terminal velocity, able to defeat 2.9″ (74 mm) armor at 30,000 yards. More

60 Caliber 3rd Year Type 15.5 cm Gun

When the Mogami class were rearmed with lighter guns following the Londong treaty signature in 1930, these were the new guns adopted. They swap back onto the 20 cm guns again after reconstruction 1939-41. Their former mounts were reused on the Yamato class battleships and light cruiser IJN Ôyodo (which had two such turrets). They had a slow rate of fire and limited elevation and were useless as dual-purpose but stayed accurate in their anti-ship role. Their theoritical rpm was 7, but in reality only 5-6 rounds per minute was achieved. Range 27,340 yards (25,000 m)/55°. They could defeat 4.2″ (108 mm) of armour at 16,400 yards (15,000 m). For the Kuma/Nagara/Sendai classes, see the WWI section.

DP/AA Guns

127 mm (5 in) dual purposes on IJN Chitose before conversion

As standard, these ships were equipped with the following:

45 caliber 10th Year Type 12 cm: cruisers built in the 1920s and early 1930s.

40 caliber Type 89 12.7 cm Gun: Standard DP gun on cruisers in the 1930s. The great standard, 14 rpm/30,840 feet (9,400 m) ceiling. More

3″/40 (7.62 cm) 3rd Year Type: Furutaka/Aoba

25 mm Type 96: The ubiquitous main AA gun of the IJN, present virtually on all ships in single or triple mounts ☍, replacing often the 13.2 mm Type 93 heavy machine gun ☍.

Of course this point would be gravely incomplete without mentioning their fabled Type 93 Torpedo, the famous “long lance”. Although not as famous as the German 88mm, British 17-pdr or the Bofors 40mm, this “secret weapon” was certainly the best asset of the IJN and best torpedo of WW2. Given its results in several “close-quarter” battles notably in the Solomons, and the poor performances of the US Mark 14 conversely, explains partly the crippling losses of the USN until late 1942.

The Type 93 was designed from 1928 by Rear Admiral Kaneji Kishimoto, and Captain Toshihide Asakuma and was accepted for production in 1932.

No nation at the time indeed had a torpedo that carried a larger payload (1018 kgs) to 43,700 yards (40,000 m) at 36-38 knots or going to 21,900 yards (20,000 m) at 50 knots.

Other Torpedoes ☍

61 cm (24″) Type 8 No. 2 (1920): On the Kuma/Nagara/Sendai classes

61 cm (24″) Type 90 (1930): Interwar heavy cruisers, Aoba, Furutaka, Nachi/Takao before replacement by the Type 93.

61 cm (24″) Type 93 (1933): Model 1, Mod 1, Mod 2 and Mod 3, all cruisers in 1941, including the unbuilt Ibuki class.

61 cm (24″) F3: First Experimental Turbine powered torpedo, 17,500 rpm geared down to 1,650 rpm at the propellers but capricious and not adopted.

Powerplants and performances

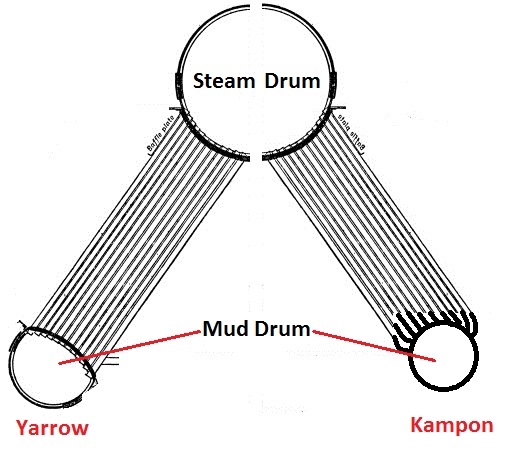

Differences between a Yarrow and Kampon boilers drum arrangement

The oldest cruisers in service in 1941, mainly converted as minelayer/training vessels from the late 1890s or 1900s still around indeed had quite antiquate machinery limiting their top speed to 18-20 knots making them unable to take part in any fleet exercize. The Asama-Idzumo (Armstrong), Yakumo (Vulcan), Adzumo (Loire Yards) had different powerplants but all were VTE, coal-burning. It seems none received any engine upgrades. The scouts of the Chikuma class (1911), still around in 1940-41, had Parsons/Curtis steam turbines and Kampon boilers and mixed coal/oil burning.

Next, were the active ships of the Tenryu class (1918): First with Brown-Curtiss turbines to achieve 33 knots. This became the new IJN speed standard for the fleet. After all they were destroyer leaders. The first cruisers with national turbines were the Kuma class (1919) which had Gihon steam turbines for 36 knots, and moslty oil-burning. This was repeated on the Nagara class (1921) and even on the Sendai class (1925), which all shared the same 90,000 bhp powerplant. They typically carried 2/3 oil and 1/3 Coal.

The transition to oil-only was not yet achieved on IJN Yubari, which was revolutionary at other titles. She had three shafts, not four as usual, same generation, but more compact geared turbines to reach 35.5 kts. The Furutaka and Aoba as built also carried a mix of Oil/coal and were capable of 34.5 kts (less after modernization).

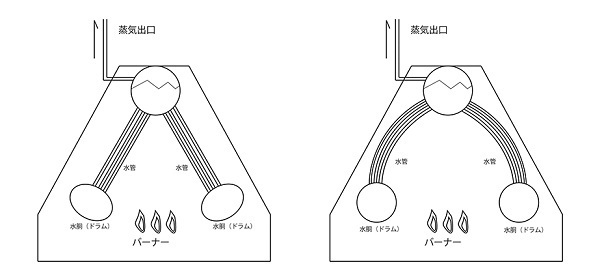

Kampon Ro-Go and Type B boilers

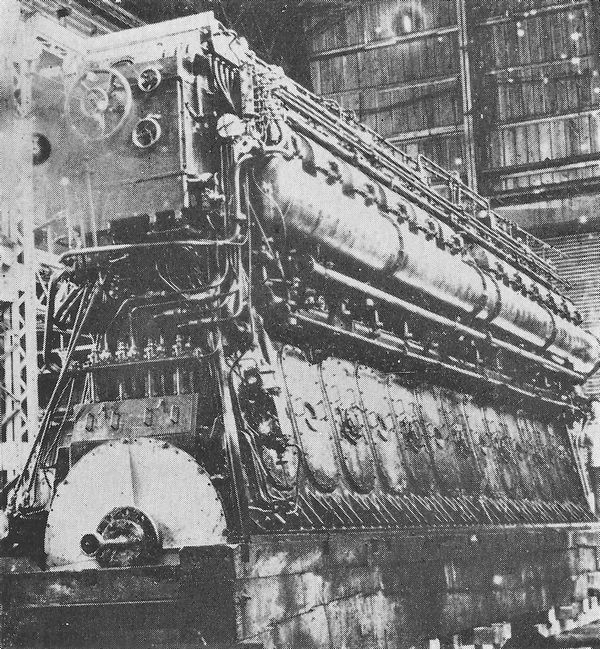

However innovation came from the next heavy cruiser generation of the Nachi and Takao class: They had still four Gihon geared turbines, but coupled with 12 Kampon new generation boilers, burning only oil. With 130,000 shp they reclaimed the speed lost at 35.5 kts, while the Mogami class had a new generation of superheated boilers, and with just ten, achieved 152,000 shp for a record 37 kts. They were the fastest cruisers in Asia. That is, before their reconstruction. The added tonnage made them closer to 35 kts at best in early 1942.

The Tone class (1937) still managed the same output with eight boilers, but kept at 35 kts as the fleet standard.

Exhaust and boilers arrangement on a Takao class cruiser

The small Ibuki class were an exception, designed as training/HQ ships. They mixed diesels and turbines for extra range (which was exceptional) and with just three boilers, only achieved 8000 hp, for 18 kts, escort speed. The light cruisers of the Agano class counted on the same powerplant as the larger cruisers, but with just six boilers in a compact arrangement. These slender vessels achieved 35 kts, sufficient for their task. The Oyodo, single in her class, had about the same arrangement but were a bit more powerful at 110 instead of 100,000 shp. They all had four drive shafts and three-bladed bronze screw propellers. It must be said that interwar aicraft carriers copied cruisers powerplants to achieve speed in excess of 36 kts (Notably Soryu/Hiryu), making them the world’s fastest aircraft carriers (The lexington class came close at 33 kts).

The gargantuan Kampon Mk.25 mod 2 diesels in 1944

As for the Ibuki class, she was not innovative in particular: She started as a repeat of the Mogami class, but when decision was made for a conversion, the first and single ship of the class modified had her powerplant halved to make room for extra aircraft, ammunition or avgas tanks: She ended with two shafts and geared turbines fed by just four Kampon boilers for 72,000 shp and 29 kts (as planned).

The heavyweights in this serie were also also unbuilt “B64” type cruisers: These were more capital ships than “cruisers” and were capable of 160,000 shp for 33 kts.

Protection

Takao class midship armour scheme. It shows a relatively common trend at the time, with an inverted external sloped belt, central turtleback type section, well compartimented ASW compartimentation with bulges also used for extra stability, divided into crush half-tubes. They had no conning tower, and only the ammunition magazines were the best protected parts of the ships, with 100 mm thick boxes, deep inside the ship, counting on the energy dispersion effect of the decks above. Indeed, cruiser’s ammunition explosions has been exceedingly rare, but cases of spare torpedoes detonating was not unusual.

It varied from ship to ship, and types. We are going to start with active cruisers in WW2, the Tenryu class and 1919 programme. As scouts, these were lightly protected, intended to only fight other destroyers. It was limited to a 2-in belt (51 mm) and 1-in deck (25 mm), creating a small “immune zone” on a very limited distance, representing 1/3 of the ship and centered around the machinery spaces. In comparison even the previous Chikuma class were better protected. However these new cruisers were capable of 33 knots, same as destroyers, making them more difficult to hit anyway.

The trend was continued on with the next Kuma, Nagara and Sendai which had about the same scheme. “Immune” area around the machinery space, but thicker at 2-1/2 inches (63 mm) and 1-1/2 inches (32 mm) respectively for the horizontal and vertical protections. The Sendai class (1925) were about the same, 2.5 and 1.1 inches respectively.

The experimental Yubari (1923) designed by Hiraga, experimented a new kind of structural protection, and it was installed internally and sloped unlike previous cruisers. And it contributed at the same time to the longitudinal strenght of the hull, a way to used all available steel plating count in a dual role. This way, this made the structure lighter overall. But fugures were still limited: 2.3 in for the internal belt, shorter than the outermost barbettes, 1-in (25 mm) both for the armored deck and gunhouses.

For the early heavy cruisers of the Furutuaka-Aoba class, the same recipe was applied, but the belt reached 3.4 in (86mm) -even 3 inches on Aoba- and the deck 1.4 in (35mm), the gunhouses (turrets) stayed at 1-in. If they were intended to combat other 8-in armed cruisers, this was ludicrously light.

For the Nachi class, at least the belt was augmented to 3.9-in (100 mm) but the deck armor remained the same, as the turrets, but at least the main barbettes were augmented to 3-in (76 mm). The next Takao class had the same scheme, but this time localized areas were better protected, as the ammunition magazines, boxed into 4.9 in (120 mm) compounds. The bridge was absolutely massive and abl to “absorb” extra punishment. As for the Mogami class, they followed the general trend of all Washington cruisers, and improved their protection a bit. The belt remained the same, they had the same boxes magazines, but a better, layered deck protection ranging from 1.4 to 2.4 in (35-60 mm).

The Tone class had the same scheme, but with 1.2 to 2.5 in for the deck protection. Protection of the turrets was still paper thin (1-in/25 mm). The next Ibuki class was a repeat of the Tone class scheme.

It must be said a few authors pretended that Japanese steel was naturally of general better quality, given perhaps the local ore, adding to the protection, in addition to Hiraga’s construction “wizardry”. It’s not the case. All sorts of stell qualities were recycled if possible, and the reputation of Japanese swords was not due to the material use, but the skills of the master smiths. The fundry tech in Japanese was borrowed from western techniques, mainly those of Britain originally, and through their purchases, Japan tested Krupp and Harvey armor as well. They did not came with a revolutionary “special process” for hardened steel of their own, at least one that is know of.

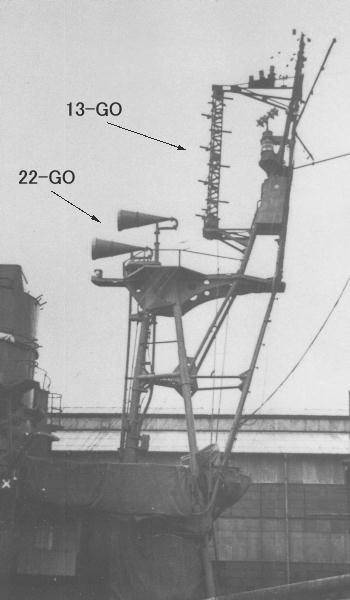

Radars

Japan came to radars a bit later than the allies. It is also often said that their optics were of superior quality and by clar weather, or even by night the “eyeball Mark I” was still the best long range detection asset of the IJN, this was especially true in the Solomons. Optical detection used to out-range US radar detection, especially because of the surrounding relief. The main types were the Ta-Se 1 Anti-Surface Radar and Ta-Se 2 Anti-Surface Radar. Hiwever the Japanese developed 30 different types of sets and had 7256+ sets of all types built. Late and far less effective than that of the Allies, they still were fitted on all surviving cruisers from 1943 onwards. Some cruisers had their mainmast rebuilt as derricks to support large aerial warning sets.

Japan came to radars a bit later than the allies. It is also often said that their optics were of superior quality and by clar weather, or even by night the “eyeball Mark I” was still the best long range detection asset of the IJN, this was especially true in the Solomons. Optical detection used to out-range US radar detection, especially because of the surrounding relief. The main types were the Ta-Se 1 Anti-Surface Radar and Ta-Se 2 Anti-Surface Radar. Hiwever the Japanese developed 30 different types of sets and had 7256+ sets of all types built. Late and far less effective than that of the Allies, they still were fitted on all surviving cruisers from 1943 onwards. Some cruisers had their mainmast rebuilt as derricks to support large aerial warning sets.

More on the topic.

IJN Cruisers in action in WW2

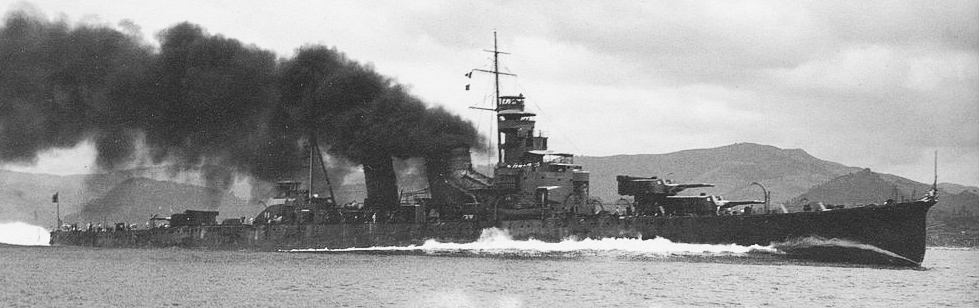

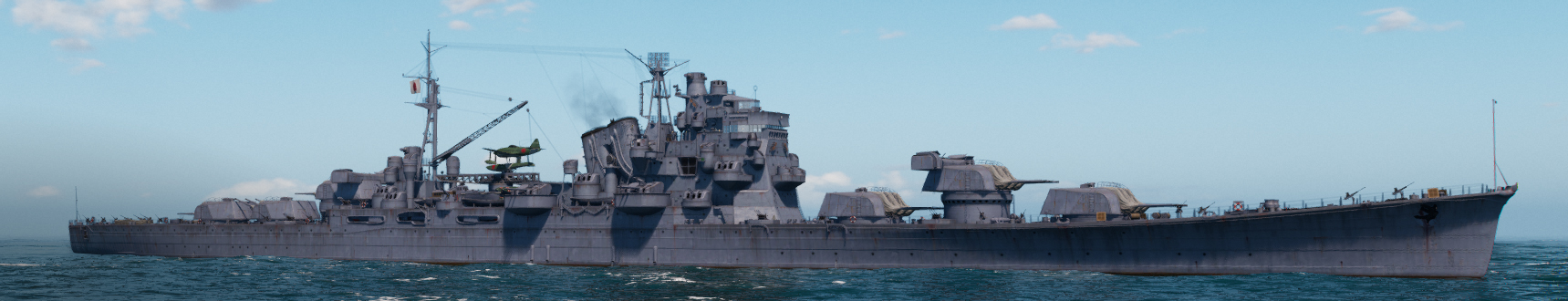

IJN Nachi in sea trials

Cruisers were classed in three categories, which defined their roles, depending on their capabilities:

-The pre-WWI cruisers still active (mostly armoured cruisers) were reclassed as training ships or minelayers and used as such.

-The 1919 program cruisers (Tenryu, Kuma, Nagara, Sendai) were considered obsolescent in 1941 and used generally (there were exceptions) as assault forces escorts, also providing fire support. In some rare cases they were used as destroyer leaders, but not ion the fleet screening role. Their role was retaken by the post-1942 Agano class, but by 1944 they were used to replace loss in standard fleet operations. IJN Oyodo was never used as intended (leading submarine attacks), and ended as fleet HQ ship. The Katori class were used as escorts for convoys and assault forces, and floating HQs, so about the same as above.

-The “fleet cruisers” (Furutaka, Aoba, Nachi, Takao, Mogami and Tone classes) were the real deal, used as part of combined fleets with battleships and carriers, or independently with destroyers, notably for cruiser forces interception (like ABDA in the west indies, or Solomons fleet moves). By default of battleships, the US used their cruisers, and the IJN answered the same, keeping their capital ship for more important operations. As befitting of cruisers, they could act independently with the escort of a few destroyers.

As said above about radars, the IJN developed the reputation of markmanship’s gunners. They also had generally good gunnery direction. There were excellent optics in general and they tended to detect their foes earlier. Not only they were able to place salvoes on target consistently but also at longer ranges.

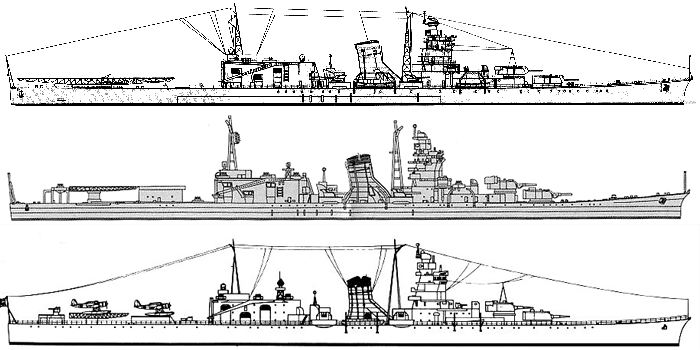

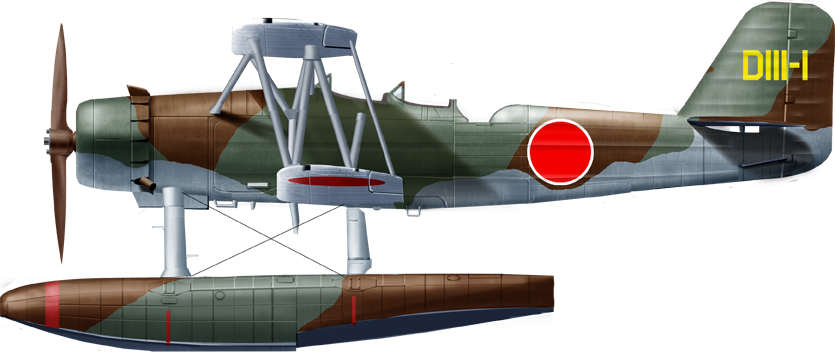

Onboard air groups and hybrid cruisers

IJN Oyodo, a standard hybrid cruiser intended to lead submersible attack groups on long range missions, equipped with the mediocre Aichi E 16 A Zuiun “Paul”.

The other factor was long range reconnaissance, well above the range of any radar. These cruisers had generous seaplane provisions, and in fact tactically were often used as “eyes” of the fleet. When integrated into combined battle formations, they screened the capital ships and sent their seaplanes before any engagement to sport and report the enemy formations. This was crucial for the “first air strike”. Let’s take two models to have a clearer view of this:

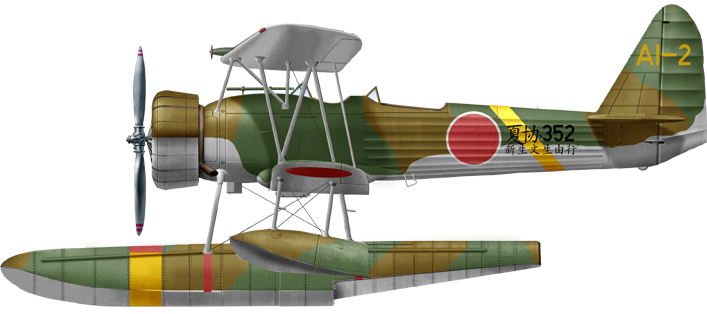

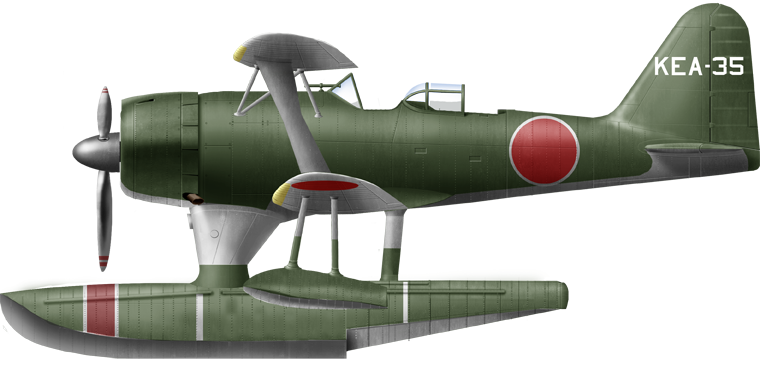

Kawanishi E7K2 “Alf”. This long range reconnaissance model was standard on all cruisers in 1941 (here IJN Abukuma).

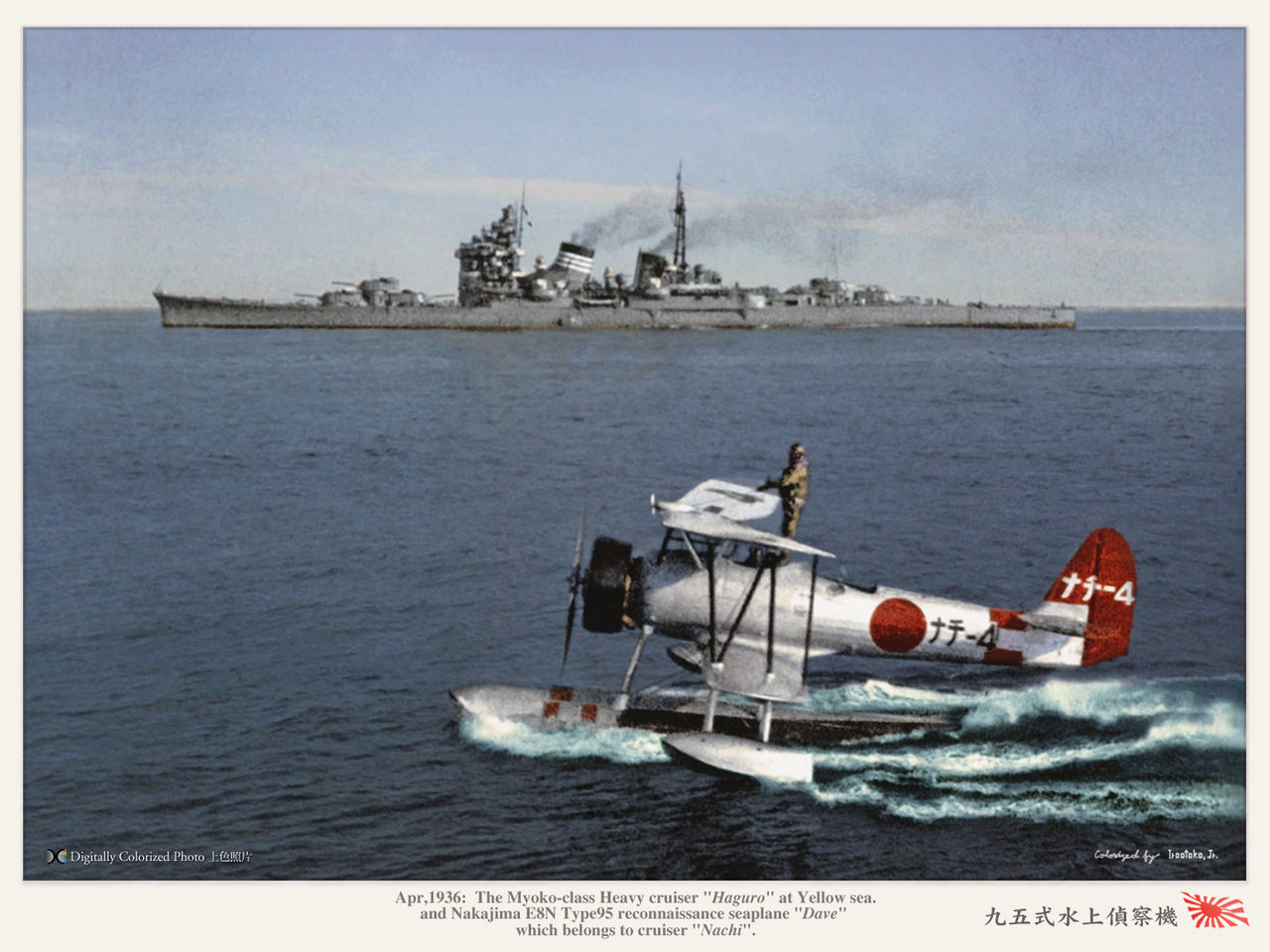

Nakajima E8N2, IJN Nagato, 1941.

Note the different in size. This was also traduced in range, which nearly was double on the Cruiser’s models. The contemporary E8N was more an artillery spotting model.

They were replaced by the Aichi E13A and Mitsubishi F1M respectively. 1919 program cruisers only had an axial catapult and single model, but later fleet cruisers had two or even three of these, a small hangar, two catapults and a deck trackway to store and dispatch non-mounted models. Usually there were two mounted on their catapults and a third, wings folded, kept in reserve. Even the small Agano had two. Some cruisers were even transformer to carry more: The Tone carried six as the Oyodo, and the Mogami was completely rebuilt also as an hybrid cruiser. This also concerned battleships, with the Ise class also rebuilt that way in WW2.

They played an important role in several engagements, reporting enemy fleets, but never really filled all the hopes placed in them. The case of oyodo is interesting by the way and Mogami also carried models intended to carry torpedoes and bombs.

Probably the best “observation/fighter” aboard IJN cruisers was the F1M “Pete”.

It was also not unusual for cruiser’s floatplanes to fill the role of carrier aviation, downing enemy aircraft (it was often the case over China) or supporting troops during assaults. Probably the best floatpolane “fighter” actually carried by cruisers was the Mitsubishi F1M “Pete”, which was high performances despite it’s biplane configuration. In fact the theoretically better A6M2-N “Rufe” was never adopted for cruiser service, kept for the defence of isolated island garrisons.

Cruiser Doctrine since 1894

One Famous cruiser tactic was the night combat:

A whole doctrine was developed around it, maximizing the cruiser’s heavy torpedo armament. Some early principles were also laid down by Baron Vice Admiral Tsuboi Kozo. A Rear Admiral in 1894, he led a special force of four extremely modern cruisers, called the “Flying Squadron” of the Imperial Japanese Navy during the 1st Sino-Japanese war and at the Battle of Yalu. He was not content to just act as a scouting force for the main fleet but took his squadron on long distance “reconnaissance-in-force” missions. Instead of dispatching his four cruisers separately for commerce warfare, he kept them together to put under heavy fire any encountered hostile unit with Guns and torpedoes. He wanted this unit to move quickly and striking key locations in rapid succession with surprise and strength. This unit became famous and had a legacy teached in the Etajima naval academy all the way to WW2. In between onboard aviation appeared, and later torpedoes were developed to a further level, enabling new capabilities.

The question of artillery was also an issue: Kubo’s squadron only had slow-firing 8-inch guns, fine against armoured cruiser but usuless against destroyers at short range. The concept of fleet light cruiser was developed in the IJN after the Second London Naval Treaty.

These tactics centered around a powerful cruiser force was put to good use at the Battle of Sunda Strait, Java Sea and Savo Island.

Nevertheless, the Japanese fleet devised two general types of surface warships (neither capital nor carriers), mainly torpedo carriers with secondary gun batteries, and mainly gun carriers with secondary torpedo batteries. Destroyers represented the first category, and heavy cruisers the second.

There was still the need of a combo between heavy cruisers and large light cruisers, as the Mogamis and Tones were originally meant to be, before reconversion. Combining long range gunnery with rapid fire against enemy destroyers would indeed have made these combinations more effective.

Organization and Use

From December 1941, the IJN mustered its eighteen heavy cruisers and four supporting fast battleships (Kongo class) actively used for the conquest, with destroyers supporting screens. They were dispatched to operate over half the Pacific, organized into five cruiser divisions (which were classes) and five supporting forces. Two of these five supporting forces had a pair of fast battleships each. These forces could have both land-based or carrier air based support (such as the forces which claimed Force Z), sparing the IJN a potentially challenging surface combat.

1942 divisions (“squadrons”):

ATAGO class (CruDiv 4): Atago (F), Takao, Maya, Chokai

NACHI class (CruDiv 5): Nachi (F), Haguro, Myoko (F), Ashigara

AOBA class (CruDiv 6): Aoba (F), Kinugasa, Furataka, Kako

MOGAMI class (CruDiv 7): Mogami, Mikuma, Kuman (F), Suzuya

TONE class (CruDiv 8): Tone (F), Chikuma

CruDiv 16 (formed 1943): Aoba (F), Ashigara, and two light carriers

CruDiv 21 (former 1942): Nachi (F), Maya/Ashigara, two light carriers

(*F: Flagship)

They were assisted by destroyer squadons with various strenghts, sometimes as low as two ships.

The Indirect Escort of Convoys from March 1942 on counted on three heavy cruiser divisions (12 ships in all) screening landings over the Pacificn with CruDiv 7 taking on Malaya, Sumatra, and western Java, CruDiv 5 the Philippines, Celebes, and eastern Java, CruDiv 6 Guam, Wake, and Rabaul. The distant cover meant the transports did not even saw them, but closer, older 1919 program cruisers as direct protectors. This never led to troubles as the allied response was so weak at first. In addition this organization meant the heavy cruisers were not stuck to close protection and could be detached of need be:

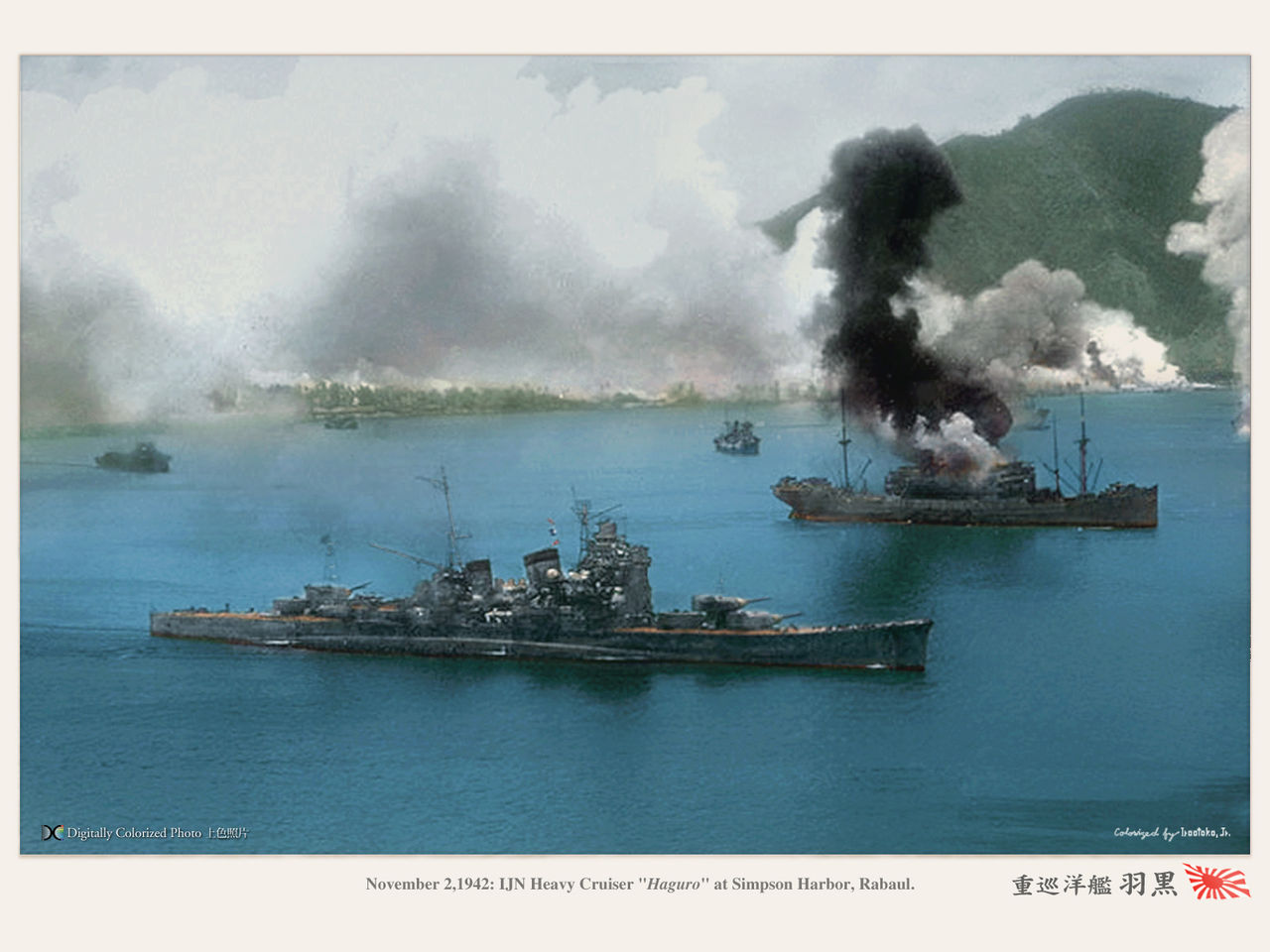

This was case at the Battle of the Java Sea (February 27, 1942) when Nachi and Haguro until then attached to the support of 41 transports, went sent to fend off the ABDA Allied cruiser force. They were repulse three times over seven hours. Long-range daylight battle was not in their favour however with only six hits scored after an hour, but victory was secured in a night action at 8000 yards with torpedoes (also fired from destroyers) working their magic. The Dutch navy was equally unaware of their range, as their allied counterparts.

However this indirect support was not always successful: It failed in Makassar Straits as the supporting Japanese cruisers were too far north to inetrvene, and when USS Houston and HMAS Perth ran into a fleet of transports while under hot pursuit (by the cover cruisers) off Java, they sank four of them. Mogami and Mikuma were again not present.

In the attempted capture of Port Moresby in May 1942 the four Aobas (CruDiv 6) were reployed in screening the support carrier force, while CruDivs 5, 6, and 7 were screening the invasion force proper, and CruDivs 4 and 8 were in close protection of the Kido Butai. The 8th screened with the fast battleships Hiei and Kirishima. They were a kind of “supporting force of the supporting force”. The Kido Butai had de facto the most powerful screen force at the time, four fast battleships and six heavy cruisers. These cruisers provided intel, via their seaplanes, notably Tone and Chikuma. This early phase saw only IJN Myoko damaged, at Davao by a B17 bomb on January 4.

Haguro in the raid of Rabaul, November 1942

A fast bombardment force was later built around Cruiser Division 7. CruDiv 8 at Midway failed to prevent the destruction of the four carriers. Tone’s floatplane sighted USS Yorktown, allowing the IJN some retribution at last. CruDiv 7 failed as the mission was aborted following the disater, Mogami rammed Mikuma after a sub sighting and later Mikuma was sunk and Mogarni severely damaged by US Carrier planes.

During the Solomons campaign these heavy cruisers were used for antishipping raids, and shore bombardments, notably at Guadalcanal, their use evolving along the situation on the ground. The night raid on 8-9 August which fed the future “ironbottom sound” was by far the mpst successful. They approached undetected due to the surrounding volcanic peaks and hills, defeating the US primitive radars, fired torpedoes and finished the job with heavy guns at close range, acheving complete surprise. The US lost four cruisers that night, including three New Oerlans class in one go. The remainder of this one-year gruelling campaign the Japanese would try to replicate that success.

In the next daylight two carrier battles of Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz, cruisers fare with little success, due mostly to their inadequate AA. But again, reconnaissance planes of those were decisive: On August 25, one of Chikuma’s seaplanes sighted the USS task force (USS Saratoga and Enterprise). They also fought not decisively in subsequent actions and were limited afterwards to bombardment runs of the “Tokyo Express”, not carrying supplies or troops themselves, as too precious.

After the Battle for Guadalcanal these cruisers were pulled back and retired in the central Pacific, notably to operate from Truk.

Nachi, Maya, Aoba, and Ashigara were more active, with the first two part of the 21st Cruiser Squadron with Tama and Kiso, seeing action in the Aleutians (5th fleet).

The last two were sent to the 16th Squadron with the light cruisers Oi and Kinu in the South Pacific. In both cases they acted as distant support, the two older cruisers being in close protection of the troopships.

Nachi at the Battle of Manila Bay, 5 November 1944

At the Komandorski Islands Nachi and Maya perfrormed poorly against an inferior force. They landed only 0.33% hits out of 1,800 main rounds fired on Salt Lake City and all their torpedoes missed. Myoko and Haguro fared little better at the Empress Augusta Bay on November 1, 1943: Without effective radar they lost 30 min. firing poorly, and were damaged in between. Despite the oppostion only had 6-in guns, they did not excelled in markmanship to say the least, and retiring with damage after achieving little.

As for the central pacific, a major raid at Truk damaged Atago, Takao, Kutnano, Tone, Mogami, and Maya, while Suzuya and Chikuma escaped unharmed. At Saipan they were mostly absent, and in the Philippines this was mostly an air war, and again, they could do little with their inadequate AA to protect the fleet.

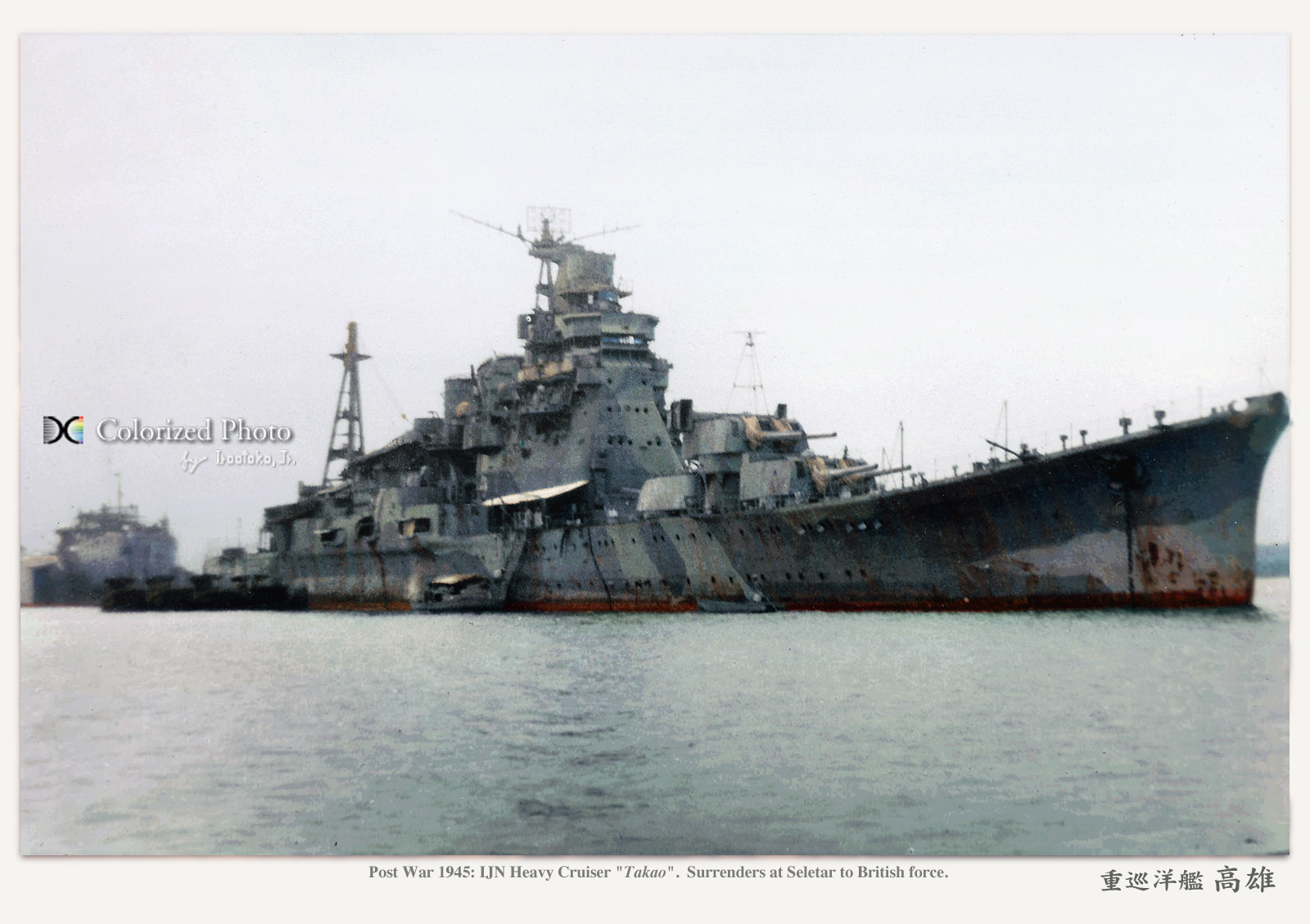

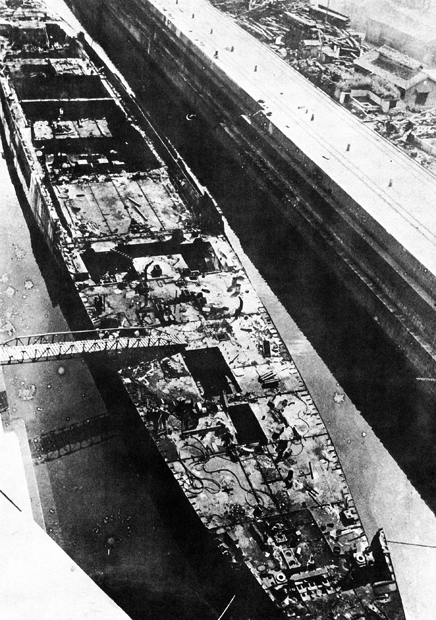

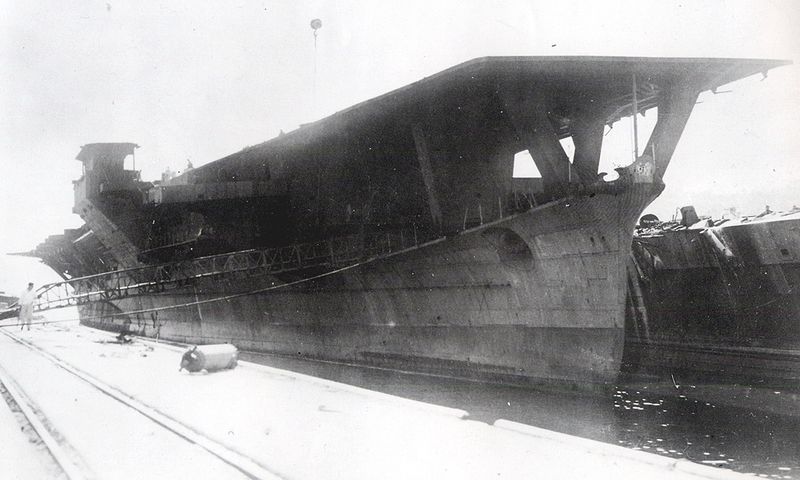

IJN Takao “rotting”, camouflaged in Singapore, as captured by British forces

The last occasion of a naval action was at the battle of Leyte in October 1944: But eight Japanese heavy cruisers were lost in the battle, the bulk of the fleet. After that Tone and Aoba were sent in Kure for repairs and never left home waters before their execution in the summer of 1945, whereas Myoko, Takao, and Haguro were sent permanently to Singapore, Ashigara in Indochina. This was pretty much game over for the IJN Cruisers at this juncture.

Night Combat

< Raizo Tanaka, a master cruiser tactician. There is a long legacy to the concept.

< Raizo Tanaka, a master cruiser tactician. There is a long legacy to the concept.

The Japanese navy specialized in the early interwar in a new kind of “night torpedo action” bringing their new heavy cruisers into very close range, putting to good use the range of their torpedoes, something completely overlooked by the USN. The Battle of Savo island was a textbook example of this, but it was not the only one.

However a usual, fate has these plans not working on the long run. The US had better radars ultimately and used their submarines in very efficient ways to detect enemy forces. The Japanese staff had to decide ultimately to use their “tokyo Express”, based around a core of cruisers, to resupply by night their beleaguered troops on Guadalcanal. This led to several night actions with various fortunes.

Too many limitations

The IJN, even after eliminating the bulk of the USN capital fleet at Pearl Harbor, continued to consider heavy cruisers as the backbone of their operations, with fast battleships ready to support them a la Hipper (usually the Kongo class specifically), but they were still too few and precious to be committed each time. To put it mildly heavy cruiser squadrons put most of the fighting, while the Japanese battleline accumulated barnacles in the Inland Sea, notably “Hotel Yamato”, despite being the most formidable asset until the USN reclaimed total air dominance over the Pacific. This was compounded with the failure of the IJN to recoignise the danger of US Submersibles tactics early enough. They too, preyed on these hard-pressed cruisers.

However in the end, the failure to consider cruisers with rapid-firing medium guns rather than sticking on armour-piercing heavier guns -the after effect of a long obsession with circumventing treaty limits- eventually produced a fatal gap in tactical firepower capabilities. With their generally good heavy cruisers but mediocre light cruisers, the fleet lacked intermediate, modern large or medium light cruisers that can fill gaps, comparable to the USN Brooklyns/Atlanta in 1942.

The IJN industry was nowhere near the capability of the US industry to provide these, as shown by the small number of Agano built (4 of 24 planned initially), Oyodo (One on 12 planned) or Ibuki (none, converted to CVL). Changing priorities converged after the disater of Pearl Harbor to aircraft carriers and smaller escorts. Or even “super destroyers” to fill that gap. IJN’s Agano class were still a prewar project completed in wartime, IJN Oyodo being the real only Japanese wartime cruiser (launched 1943) taking some lessons of these deficiencies, but making the choice of an hybrid configuration. It was large enough to have been given three or even four tripl turrets with 6-in guns.

To compare at the same time, the USN laid down more than 65 keels for light cruisers (Cleveland and Atlanta class) and 30 keels for heavy cruisers, completing most of them, the Royal Navy itself commissioning also many new cruisers during that time.

This lack of resources meant efforts were concentrated on aircraft carriers, escorts, “secrets weapons” such as the Kaiten submarines, or Shinyo Motor Boats, the Yamato and Mushashi absorbing most of available the resources in 1941-42. Would more cruisers had changed the nature of the fight in 1942-43 ? Not really, as air power was the dominant factor, but until the Japanese retired from Guadalcanal, operations were mostly led by Cruisers, especially by night, and they proved very efficient.

USNI Japan’s Heavy Cruisers in the War (1950)

US Postwar assessement of IJA night combat

See also the tabular record of movements of the cruisers

Vintage IJN Cruisers in WW2

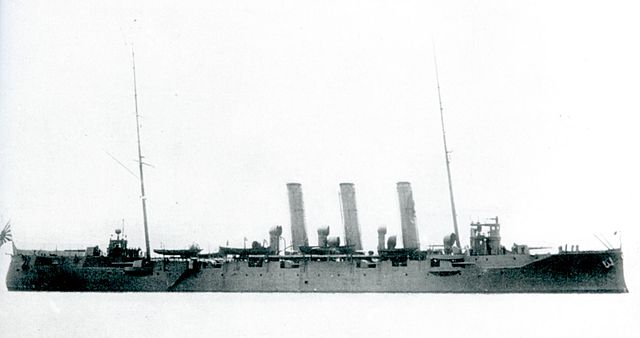

Tsushima (1902)

Tsushima (1902)

Hulked 1930. Sunk 1944. Also hulked, IJN Adzuma, but in 1941. Survived the war into 1946 and BU. On 1st September 1921, IJN Tsushima was re-designated a “2nd class coastal defense vessel”. In 1922 seh received six modern 15.2 cm and eight 12-pdr (3 in) guns. Later in the 1920s she was given a single 12-pdr AA gun. She became the main patrol vessel on the Yangtze River and Kichisaburō Nomura’s flagship, at the head of a gunboat fleet.

IJN sushima was partially disarmed in 1930 and became back home a training ship, struck in 1936. She became “training hulk Hai Kan No. 10”, annchored at Yokosuka Naval District, until 1 April 1939. She ended her life as a target ship off Miura (Kanagawa) by torpedoes in 1944.

As for Niitaka, from September to July 1920, she covered landings of the IJA in Petropavlovsk as part of the anti-Bosheviks Siberian Intervention and as fishery protection vessels for Japanese trawlers along the Kamchatka Peninsula. By May 1921 she was patrolling southern China and down to the Netherlands East Indies, and South China Sea. From September 1921, she became a “2nd class coastal defense vessel”. On 26 August 1922, she was based on the southern coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula, sending a landing party of 15 led by Lieutenant Shigetada Gunji ashore, looking for presence of Belsheviks there. Ironicall they became survivors as the while crew disappeared when the ship was caught by a sudden typhoon, with gale winds drossing her onto rocks. She was overturned. A salvage team went there in 1923 to examine the wreck and see if it was recoverable. But it was not to be and the wreck was finished off with explosives, and the metal taken away. She was stricken on 1 April 1924.

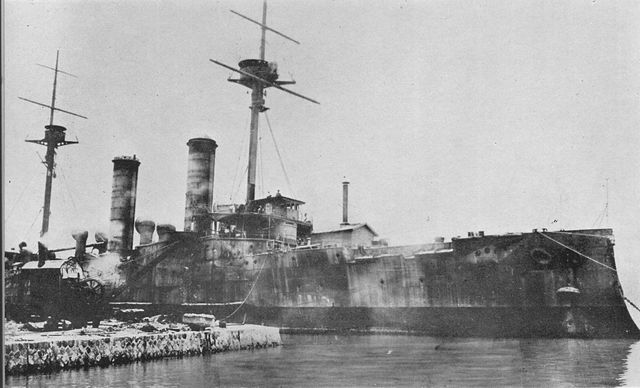

Training Cruiser IJN Asama (1898)

Training Cruiser IJN Asama (1898)

IJN Asama towed in Sydney, 1930s

After the war Asama was used as navigation training ship, performinge long range cruisers for cadet officers. On 21 August 1920, she visited South America and Polynesia but by late 1921 she was re-designated a 1st class coast defense ship. In 1922, her main deck guns were removed as six 6-in, four 12-pdr guns, QF 2.5-pdr guns and casemates plated over. A single 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type AA gun was added however.

From 26 June 1922, her training cruises brought her to Australia, Southeast Asia, and Mediterranean; but she ran aground on the night of 13 October 1935 NNW of Kurushima Strait, Inland Sea. Rngineers estimated that she was difficult to repair. Towed to Kure she was provisionally repaired, and assigned the Kure naval Corps as a stationary training ship from 5 July 1938.

Asama as a barrack ships in 1946. She was BU the next year.

She was reclassified as a training ship in July 1942 and was later converted as a gunnery TS at Shimonoseki, keeping a few 80 mm/40 (78 in) 3rd Year Type AA guns in 1944. But she was eventually stricken on 30 November 1945, scrapped at the Innoshima shipyard (Hitachi Zosen) after the war, from 15 August 1946.

Minelaying Cruiser IJN Tokiwa (converted 1928)

Minelaying Cruiser IJN Tokiwa (converted 1928)

IJN Tokiwa in 1945

Tokiwa, a former Asama class armoured cruiser built in Britain (launched 1898), was reassigned to the Training Squadron on 10 August 1918 and prepared a training cruise with Azuma from 1 March 1919 for South Asia-Australia. From 24 November she stopped at Singapore, visited Southeast Asia, crossed the Indian Ocean, Suez Canal and entered the Mediterranean Sea, back home by 20 May 1920 and left the Training Squadron in June, reclassed as 1st class coast-defense ship and taking in hands at Sasebo on 30 September 1922, for conversion into a minelayer:

She was modified to carry To accommodate 200–300 mines depending of the type:

-Rear 8-inch gun turret, six 6-inch guns (main deck) removed.

-Rear guns were removed and two 12-pdr retained

-Two 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type anti-aircraft guns added.

The process ended by March 1924 but she suffered whilke in service an accidental explosion in Saiki Bay (1 August 1927) when mines were disarmed. One detonated, fllowed by others and 35 were killed, 65 wounded. Tokiwa was repaired and went to the reserve fleet. From January 1932 she joined the 1st Fleet, until May 1933. She served in China. From November 1937 she was druyocked and gutted, with eight new Kampon boilers, with a speed down to 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph), torpedo tubes removed. The freed space enabled to carry 500 extra mines. She was reassigned to the 4th Fleet on 15 November 1939, then 18th Division, 19th Division in 1943 (Rear Admiral Kiyohide Shima) with the other minelayer IJN Okinoshima. In 1940, she received two single 40-mm (1.6 in) guns, 20 Hotchkiss 25-mm Type 96 light AA guns (twin-guns).

On 9-10 December 1941, IJN Tokiwa and other minelayers from the 19th Division escorted two troop transports for Makin and Tarawa. By January 1942, Tokiwa took part in Operation R to Rabaul and Kavieng andlater Kwajalein. February 1942 saw her attacked by planes from USS Enterprise, she was later repaired in Sasebo and was back to Truk on 14 July 1942. On the 19th she joined the assault Makin squadron tasked to reoccupy the Atoll after the USS Raid.

On 1 May 1943, she was part of the Ōminato Guard District. She left Truk on 26 May to escort a convoy to Yokosuka ambushed but missed by USS Salmon (SS-182) in June. She was reassigned to the 18th Escort Squadron, 7th Fleet, on 20 January 1944. She was reamed with ten single 25 mm Type 96 AA guns and 80 depth charges as well as a Type 3-1, Mod 3 and Type 2-2, Mod 1 radars. She layed a large minefield off Okinawa the same month, and off Yakushima in February 1945.

However on 14 April 1945 (78 miles off Hesaki- Kyūshū) she hit a mine, but damage was moderate. USAAF B-29 Superfortress bombers laid mines and she hit another one on 3 June 1945. Caught by TF 38 US aviation while off Ōminato, Mutsu Bay (northern Japan) on 9 August 1945 she took several near-misses and at least a direct hit. Her captain decided to have her beached to avoid sinking. On 30 November 1945 she was stricken and her wreck, partially underwater, was relfoated and towed for demolition in Hakodate, BU in August–October 1947.

Coast Defence ship IJN Yakumo (1899)

Coast Defence ship IJN Yakumo (1899)

The single German (Vulcan-built) armoured cruiser (launched 1899) was still active in 1918. On 1 September 1921, she became a “1st class coast-defense ship” used for training, as her sisters making long oceanic navigation trips with academy cadets, making 13 of these cruises in the interwar, visiting all continents over time. She even made a circumnavigation of the globe (August 1921-April 1922) with IJN Izumo, with distinguished hosts such as Princes Kuni Asaakira and Kachō Hirotada.

In 1924, her armament was modified: She her most her 12-pdr guns and all QF 2.5-pdr, three TTs removed, but eight single 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type AA guns added. In 1927, she was drydocked for her boilers to be replaced by six modern coal/oil-burning Yarrow boilers from the rebuilt IJN Haruna. He new output was 7,000 ihp (5,200 kW) for 16 knots. She carried 1,210 metric tons of coal and 306 metric tons of oil.

With Izumo she landed IJN Marines in Tsingtao by 1932 to quell a riot of Japanese residents and in 1933 she became a training ship. From 6 November 1936 she suffered an accidental explosion while underway between Saipan and Truk. This was in the front ammunition magazine. 4 were killed, but it was quickly flooded. Two weeks later she was repaired. By December 1936 she had a new captain, Matome Ugaki, departing in 1937 for IJN Hyūga. She made new cruises in 1937 and 1939, the last ending on 20 November 1939.

From early 1942, IJN Yakumo was fully reactivated as “1st class cruiser”, on 1 July 1942. Her main guns were by four 12.7 cm (5.0 in) standard Type 89 DP guns in two twin mounts in place of her former 8-in turrets. She also receibed extra 25 mm in triple and single mounts. She was based in the Seto Inland Sea for training until stricken on 1st October 1945. She started repatriation trips in December, notably from Taiwan and mainland China. Her last ended by June 1946, with 9,010 onboard. She was sold and BU at Maizuru (Hitachi Shipbuilding) by July 1946.

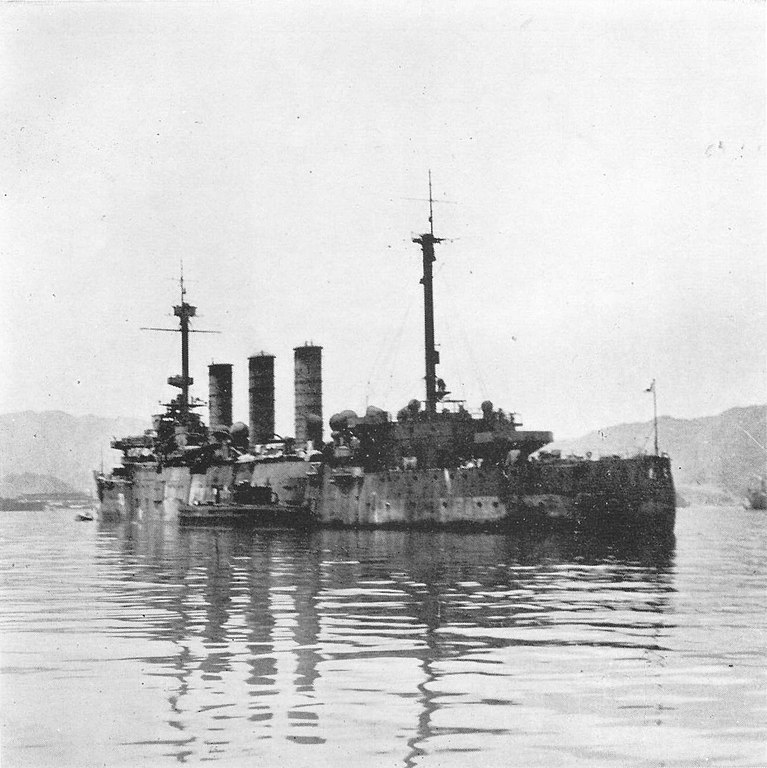

Izumo class Coast Defence ships (1899)

Izumo class Coast Defence ships (1899)

Izumo 1932

The lead ship of the Izumo class, veteran of the Russo-Japanese war participated in the 1919 Naval Review in honor of Emperor Taishō. “1st class coast-defense ship” from September 1921 she also was a oceanic navigation training ship for the Academy, making six voyages in the 1920s-1930s and a circumnavigation from August 1921 to April 1922 with Yakumo. On 7 February 1925 she collided with a tugboat at night.

In 1924 she had a first refit: 12-pdr guns, QF 2.5-pdr guns, TTs removed later in 1930 and single 8 cm/40 3rd Year AA gun added. Her final armament was just four 12-pdr (3-in/76mm). In 1935 she was drydocked, six Kampon water-tube boilers (7,000 ihp/16 knots) replacing her former large powerplant. This freed space for more bunkerage and extra cadet accomodations/instructor spaces. She had 1,428 metric tons of coal, 329 of fuel oil, and displaced 10,864 metric tons.

On 2 February 1932, she intervened after the first Shanghai Incident, as flagship, 3rd Fleet (Admiral Kichisaburō Nomura). In 1934 she was refitted in Sasebo, receiving a floatplane.

As the Second Sino-Japanese War started by July 1937 she was attacked on 14 August by the Chinese Air Force in the Battle of Shanghai. Two bombs landed among spectators. Izumo’s Nakajima E4N floatplane and another from Sendai claimed to have shot down one Curtiss Hawk biplane and a Northrop Gamma. Her E4N claimed another Hawk afterwards. She was attacked by a Chinese torpedo boat, but torpedoes missed. The TB ws promptyy destroyed. Next, she provided naval gunfire during the battle. Chinese aircraft attacks went on but she had no hit to report, only strafing attacks.

Izumo was still there by 8 December 1941. She captured the USS Wake and gunned, sinsked the HMS Peterel. On 31 December however she hit a mine in Lingayen Gulf while taking part in the Philippines Campaign. Towed to Hong Kong by February 1942 she was repaired, and re-classified as a “1st-class cruiser” by July. By late 1943 she was a training ship in Kure and by 19 March 1945, while off Etajima she was attacked by airplane but only had light damage. He antiquated 8-inch guns were at last replaced by twi twin 12.7 cm (5.0 in) Type 89 DP and her last 6-in guns removed. She received 25 mm Type 96 AA guns (2×3, 2×2, 4×1 mounts) and 2×1 13.2 mm Hotchkiss HMGs. She hit an aerial mine on 9 April off Hiroshima and was near-missed by 28 July 1945. These caused flooding extensive enough to turnover and capsize slowly for most of the crew to survive. Stricken on 20 November she was scrapped in 1947 at Harima Dock. More (TroM)

Training Cruiser IJN Kasuga (1902)

Training Cruiser IJN Kasuga (1902)

Part of the Nisshin class purchased to Italy in 1905, this veteran of the Russo-Japanse war and WWI arrived in Portland, Maine for the state centennial celebration on 3 July 1920, visited New York City and Annapolis, Cristobal (Panama) and San Francisco. She carried soldiers and supplies to Siberia in 1922 (Siberian Intervention) under command of Mitsumasa Yonai (future Prime Minister of Japan) and on 15 June 1926 rescued off Japan the crew of the freighter SS City of Naples.

From 1927 she was rerated as a training vessel for navigators and engineers and by July 1928 rescued the crew of airship N3 during fleet maneuvers. By January–February 1934 she carried 40 scientists to Truk for a solar eclipse. Hulked and disarmed by July 1942 she became floating barracks, capsizing at her mooring at Yokosuka on 18 July 1945 after near-misses of an air raid. She was salvaged in August 1948, BU at the Uraga Dock Company. No photo exist to my knowledge of her during the war.

Hirado(Chikuma) class (1911)

Hirado(Chikuma) class (1911)

Hirado, Yahagi

Hirado in 1912, note the clipper bow. She apparently never changed appearance in the interwar.

The Chikuma class were two scout cruisers of the IJN, the first of their kind. Fast and moden there were comprehensible restrain to scrap her after the Washington treaty. Her sister Chikuma was sunk as a target ship, 1935, while Yahagi was discarded on 1 April 1940. As for the only one active in 1941, IJN Hirado was assigned to patrol off the east coast of Russia for supply and troop convoys to Siberia, taking her share of service against the Bolshevik Red Army. Her captainw as soon the future Fleet Admiral Osami Nagano (1919-1920) and then Captain Zengo Yoshida until December 1924.

She was tasked to guard the southern approaches to Japan, stopping in Manila and Macau. From 1932 she was reassigned to the northern coast of China and after the Manchurian Incident, based in the Ryojun Guard District (Kwantung Leased Territory). She was plagued all along by engine problems.

Placed in reserve vessel in 1933 she became a training ship, officially stricken on 1 April 1940 but used as the barrack ship Hai Kan No.11 at Etajima Naval Academy and Kure. Towed to Iwasaki in December 1943 she was scrapped postwar, by January-April 1947.

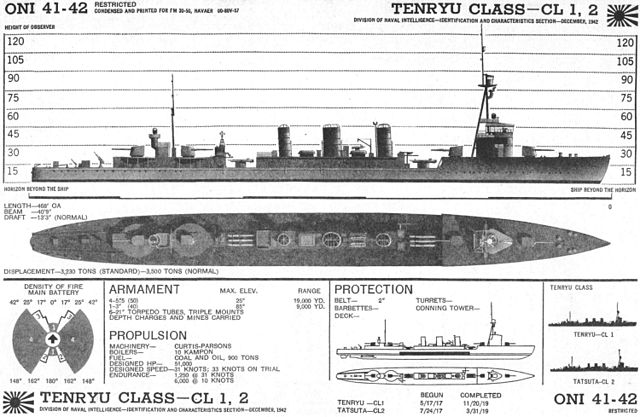

Tenryu class (1918)

Tenryu class (1918)

Scout Cruisers Tenryu, Tatsuta

If the great cruisers of the class Kuma, Nagara and Sendai are better known, they constitute an evolution of these precursors, built during the great war. Indeed, the Tenryu and the Tatsuta were defined by the Admiralty in 1916 who wanted a kind of “super-destroyer” based on the British design of the Arethusa and “C”. Under the name of project 33, they were laid down in 1917 two months apart at the Yokosuka and Sasebo shipyards. They had been defined as squadron leaders capable of 33 knots. They also received the new 140mm guns fitted to the two Ise-class battleships. They were also the first to benefit from triple banks of torpedo tubes.

During their long active career (launched in 1918 and completed in 1919), they received a sturdier tripod foremast. Originally, their DCA was provided by a single 78 mm mount, replaced in 1941, after being supported by two 13.2 mm machine guns in 1939, by 5 double 25 mm mounts. The Tatsuta however retained its 78mm on the rear shelf. During the war, they mainly performed escorts. The Tenryu was sunk on December 18, 1942 by an American submersible, the USS Albacore. The Tatsuta survived her only until April 1944, to be torpedoed and sunk in turn by another submersible, the USS Sandlance.

Specifications

Displacement: 3,948 t. standard -4,350 t. Full Load

Dimensions: 142.9 m long, 12.3 m wide, 4 m draft

Propulsion: 3 shafts Kampon SG turbines, 10 mixed boilers, 51,000 hp= 33 kts

Armor protection: From 51 (belt) to 25 mm (Main Deck)

Armament: 4×1 140 mm, 1x 78 mm, 8x 25 mm AA, 2x 13.2mm AA, 2×3 610mm TTs

Crew: 340

Interwar IJN cruisers

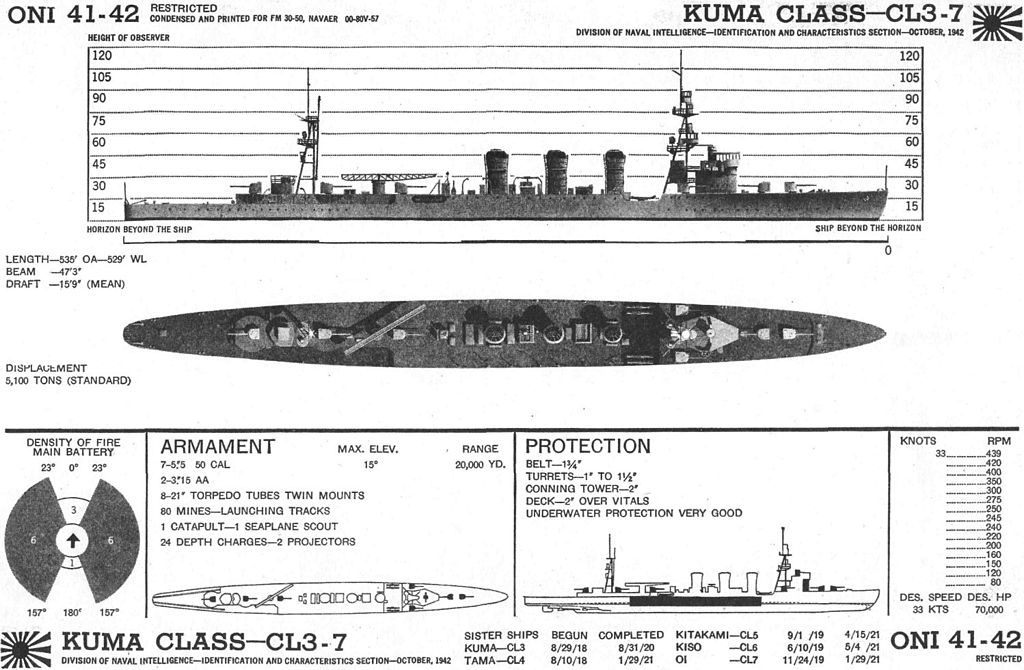

Kuma class (1920)

Kuma class (1920)

Scout Cruisers Kuma, Tama, Kitakami, Oi, Kiso

The 6 Kuma class cruisers, of the great armament plan of 1916, entered service too late to participate in the conflict, the last in 1921. They were enlarged versions of the two Tenryu, with a reinforced armament of 3 pieces 140 mm, they were more powerful and faster, but accusing a displacement of 1500 tons higher. They were a compromise between light cruisers and scout ships.

The class included the Kuma, Tama, Kitakami, Oi, and Kiso. Kuma and Tama received seaplanes and a catapult in 1934-35, their rear mast became tripod, the hull was reinforced, the Kitakami seeing its front funnel raised while the others saw themselves grafting different funnel heads. Their foremast superstructures were enlarged. They received four additional 25 mm in 1938-39, and their Torpedo tubes pwere upgraded to 610 mm instead of the initial 533 mm. The displacement thus increased by 200 tons, their speed, initially 36 knots, fell to 33.

Following the very aggressive naval tactics in vogue at the time, the Oi and the Kitakami ferret converted into torpedo cruisers, an old concept fallen into oblivion and refreshed with these versions equipped with 10 quadruple banks of torpedo tubes (40 in total), mounted on 60-meter-long hull side extensions and losing their main artillery. They returned to service in December 1941. Kitakami gained two additional 25mm twin mounts, as well as two 127mm AA twin turrets, and in 1943 she lost four torpedo banks. Severely damaged by the English submarine HMS Templar in 1944, she will be rebuilt as a kaiten transport, losing part of its machinery, replaced by a hold, a crane and a workshop for these eight piloted torpedoes. She survived the war and was BU in 1947, while the Oi was sunk in July 1944, Kiso in November 1944, Tama in October 1944, and Kuma in January 1944.

Specifications

Displacement: 5,650 t. standard -6,200 t. Full Load

Dimensions: 158.6 m long, 14.2 m wide, 4.8 m draft

Propulsion: 2 shafts, 4 Gihon turbines, 12 Kampon boilers, 90,000 hp=32 knots

Armor: 32 to 62 mm

Armament: 7x 140 mm guns, 4x 25 mm AA guns, 4×2 610 mm TTs, mines, 1 aircraft

Crew: 450

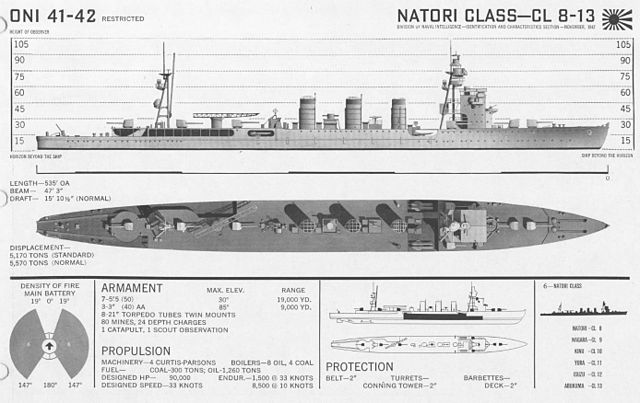

Nagara class (1921)

Nagara class (1921)

Scout Cruisers Nagara, Isuzu, Natori, Yuru, Kinu, Abukuma

Isuzu rebuilt in 1944

Isuzu rebuilt in 1944

IJN Nagara:

IJN Isuzu: She was built at the Uraga Dock Company. She was commissioned on 15 August 1923 and participated in the second war with China, covering landings in China, and the capture of Hong Kong. Reassigned to the Dutch East Indies, for the landings and battle of Java, she also later took part later in the Solomon Islands campaign. She was present at the Battle of Santa Cruz and the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Almost sunk due to air attacks in late 1943, she headed back to Japan to be rebuilt into an anti-aircraft and anti-submarine cruiser. She participated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, sunk later by a “wolfpack” of three US submarines and one British, off Sumbawa, 7 April 1945.

IJN Natori:

IJN Natori was built by the Mitsubishi Naval Yard in Nagasaki, commissioned on 15 September 1922. In 1937 and afterwards, she covered troops landings in China and in early 1942, took part in the Phillippines invasion. She also took part in the Dutch East Indies campaigh, notably contributing during the Battle of Sunda Strait, to torpedo the cruisers USS Houston and HMAS Perth. Next she stayed patrolling in the Dutch East Indies waters before a refit and repairs in Japan after air attack in June 1943. She was back in service by April 1944, sunk off Samar by USS Hardhead, on 19 August 1944.

IJN Yura:

IJN Yura was commissioned at Sasebo Naval Arsenal, on 20 March 1923. She was pat of the fleet shadowing Force Z (Prince of Wales and Repulse) in december 1941. Later in January 1942 she covered the landings of Japanese troops in Malaya and Sarawak. She also took part in the Indian Ocean raid, and was part of Nagumo’s escort at the Battle of Midway. She also later took part in the Battle of te Eastern Solomons. Badly damaged after a sever air atack in the Solomons, she was scuttled to prevent capture on 25 October 1942.

IJN Kinu:

IJN Kinu was completed at Kawasaki Shipbuilding Corp., Kobe, on 10 November 1922. She was part of the fiorce shadowing Prince of Wales and Repulse and like her sister Yura also took part in the landings of Japanese troops in Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. She took part in many combat missions in the Solomon Islands and the Philippines. She was ultimately sunk by USN aviation in the Visayan Sea, on 26 October 1944.

IJN Abukuma:

Last of the Nagara class, IJN Abukuma came from the Uraga Dock. She was commissioned on 26 May 1925, part of the escort force assigned to the kido Butai at Pearl Harbor. She was later also the sole Nagara class ship at the Battle of the Komandorski Islands (north pacific), remaining active in northern waters until October 1944. She was rushed south to oppose the American invasion of the Philippines, caught and attacked, severely damaged by ambushing American PT boats, at the Battle of Surigao Strait (25 October) finished off by land-based bombers and eventually scuttled on 26 October 1944.

Sendai class (1923)

Sendai class (1923)

Light Cruisers Sendai, Jintsu, Naka +5 cancelled

The cruisers of the Sendai class were very close in their general design compared to the previous Nagara, but with larger dimensions, new machinery for greater speed traduced in a new funnel. The fourth of the class, 1st batch, IJN Kako, was broken up soon after launch, as the following 2nd batch because of the Washington Treaty limitations, just signed.

The three cruisers received a catapult for reconnaissance in 1929, and by 1943, a powerful AA. All were sunk in action, Naka in February 1944 during the air raid on Truk, Sendai by aviation after the Battle of the Bay of Empress Augusta, and Jintsu by gunfire at the battle of Kolombangara.

Specifications

Displacement 5,200 t. standard 7,100 t. Fully Loaded