Germany (1913-1919) – SMS Brummer, Bremse

Germany (1913-1919) – SMS Brummer, Bremse WW1 German Cruisers

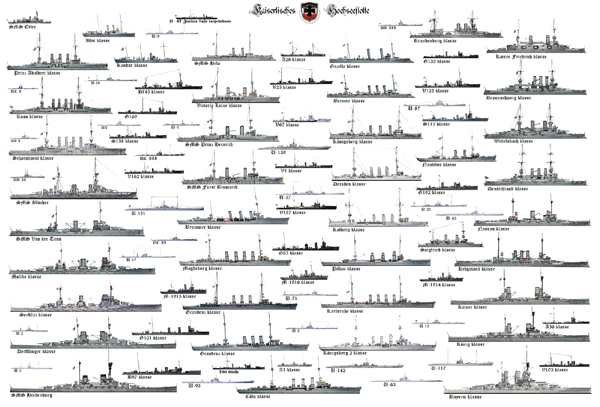

Irene class | SMS Gefion | SMS Hela | SMS Kaiserin Augusta | Victoria Louise class | Prinz Adalbert class | SMS Prinz Heinrich | SMS Fürst Bismarck | Roon class | Scharnhorst class | SMS BlücherBussard class | Gazelle class | Bremen class | Kolberg class | Königsberg class | Nautilus class | Magdeburg class | Dresden class | Graudenz class | Karlsruhe class | Pillau class | Wiesbaden class | Karlsruhe class | Brummer class | Königsberg ii class | Cöln class

In 1915, the Admiralty decided to start construction in Vulcan, Stettin, of two large turbine-powered minelayer vessels. Launched in December 1915, March 1916, commissioned in April and July 1916. These were very active and successful ships until the end of WWI.

Design development

In order to strengthen or replace Albatross and the Nautilus, the only mine-laying cruisers in the German fleet, the Admiralty decided to start construction in 1915 at Vulcan, Stettin, of two large vessels dedicated to this task, better armed than the frail light cruisers of 1906. The Brummer and the Bremse were launched in December 1915 and March 1916 and accepted in April and July 1916. Decision to build them was also facilitated by the presence of turbines built to propel the Russian battle cruiser Navarin, whose construction was canceled due to the war. So they were quite powerful as a result.

In order to strengthen or replace Albatross and the Nautilus, the only mine-laying cruisers in the German fleet, the Admiralty decided to start construction in 1915 at Vulcan, Stettin, of two large vessels dedicated to this task, better armed than the frail light cruisers of 1906. The Brummer and the Bremse were launched in December 1915 and March 1916 and accepted in April and July 1916. Decision to build them was also facilitated by the presence of turbines built to propel the Russian battle cruiser Navarin, whose construction was canceled due to the war. So they were quite powerful as a result.

In the end, these mixed ships, running on coal and fuel oil, were able of way than 28 knots (29.5 on trials), and developed more than 42,000 hp (Brummer) and 47,000 (Bremse) during the same trials. Their career was quite intense: SMS Brummer was part of the 2nd and then the 4th fleet. In January 1917 she participated with Bremse in the great minefield laid between Norderney and Helgoland. In October, she was detached with her sister-ship to attack convoys and from 16 to 18, decimated a convoy by sinking 8 freighters and a destroyer, another badly damaged.

In November, Brummer successfully carried out another raid from Helgoland. In June 1918, she was seen performing two more minelaying missions, but remained inactive until November. Bremse raided off Fisher Bank in December 1916, and had the opportunity to use her AA to protect Zeppelin L44 from British fighters in September 1917. She also went out against merchant traffic, and carried out a raid on the coasts of Norway in April 1918. Like Brummer, she was forced to join Scapa Flow after the capitulation and scuttled there in June 1919.

In 1914, AG Vulcan in Stettin was building two sets of high-powered steam turbines for the Russian Navy, intended for the battlecruiser Navarin under construction in Russia. However August 1914 had the German government seizing the turbines. Meanwhile, the Kaiserliche Marine’s only two minelayer cruisers Nautilus and Albatross being whoefully unsufficient, ordered AG Vulcan to reuse Navarin’s turbines and from there, deliver two cruiser hulls buikt around these in order to be fast mine-layers for night operations of the British coast. The speed allowed them to make a “hit and run” minelaying opetration and not to be intercepted. Also it was envisioned to make them look superficially as the British Arethusa-class cruisers to confused British observers and allow them to close on the hostile coast.

Final Design and construction

Design work was completed in 1914, just after the order, SMS Brummer being laid down at AG Vulcan, Stettin in early 1915, built in record-time to be launched on 11 December. SMS Bremse was also built at AG Vulcan, but launched later, on 11 March 1916 and still completed in less than four months to be commissioned in mid-1916. To reach the same crescent bow shape (straight in German cruisers) and general silhouette of British cruisers the yard went as far as covering parts and add fake volumes using sheet metal for a perfect disguise.

Brummer was contract name “C” laid down at the AG Vulcan shipyard in Stettin in 1915. She was launched on 11 December 1915, after which fitting-out work commenced. Completed in less than four months. SMS Bremse was ordered under the contract name “D”, laid down also at AG Vulcan shipyard the same day but launched on 11 March 1916, followed by an express fitting-out work, also in four months for a commission on 1st July 1916, one month after Jutland.

Hull

Both Brummer and Bremse were 135 meters (442 ft 11 in) long at the waterline, mostly due to the space required for the turbines, around which the rest of the ships were designed. They reached 140.4 m (460 ft 8 in) overall for 13.2 m (43 ft 4 in) in beam (making for a 1/10 ratio) and 6 m (19 ft 8 in) draft forward, down to 5.88 m (19 ft 3 in) aft. Designed displacement was 4,385 metric tons (4,316 long tons) standard and up to 5,856 t (5,764 long tons) when battle ready and fully loaded.

Construction of the the hull called for longitudinal steel frames and a waterline internal compartimentation pushed into twenty-one watertight compartments. They also had a double bottom for 44% pf the hull underbelly, over the keel. SMS Brummer was given portholes amidships, but not Bremse, and this was their first difference.

For the silhouette, both were given masts shaped like and implanted as on the British Arethusa-class cruisers, and they could be lowered and stored on the superstructure deck to free some fire arc or steam under bridges if necessary. The bow was modeled too as an Arethusa class bow, using extra plating to reach the desired shape. They carried both some 16 officers and 293 ratings and had the usual fleet of smaller service boats installed aft at the foot of the mainmast, served by a boom, and on davits along the main deck: She carried a steam picket boat, a barge for supplies, and two dinghies.

Powerplant

The Brummer’s propulsion systems rested on these two turbines, rather powerful for cruisers. They drove two three-bladed screw propellers 3.20 m (10 ft 6 in) in diameter. These turbines in turn were fed by six mixed firing boilers: by just two coal-fired Marine Doppelkessel double-ended water-tube boilers, but also four oil-fired Öl-Marine double-ended boilers. Total output was rated for 33,000 shaft horsepower (25,000 kW), enough for a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). Thus was equivalent to the Arethusa class.

On trials however, Brummer with forced heating reached 42,797 shp (31,914 kW) for 30.2 knots (55.9 km/h; 34.8 mph) and even 47,748 shp (35,606 kW) for SMS Bremse, which was also observed capable of reaching 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph) in quick runs, something no British criser was capable of at the time.

They carried 300 t of coal as designed in peacetime, which could be doubled to 600 t in wartime, notably by filling extra waterline compartments. They also carried 500 tons of Fuel oil and also by having all voids filled, could reach 1,000 t. At a cruising speed (12 knots or 22 km/h/14 mph, they reached 5,800 nautical miles (10,700 km; 6,700 mi). When fast-cruising at 25 kn (46 km/h; 29 mph) this naturally fell to 1,200 nmi (2,200 km; 1,400 mi). Electrical power aboard came from two Siemens turbo generators coupled with a MAN diesel generator.

There was a single, large rudder and it was enough for them to be regarded as excellent sea boats, very agile, and with gentle and predictable motion making them good gun platforms. They had a tight turning radius and bled speed in heavy weather or about 60% speed when turning hard. They were also seen a bit stiff as well.

Protection, Armour scheme

Their protection tested on Krupp cemented steel. There were the following:

- A Full waterline armored belt that 40 mm (1.6 in) in thickness amidships

- The bow and stern were completely unarmored.

- The armored deck at waterline level was just 15 mm (0.59 in) thick.

- There was no extra armor over the steering gear room or ammunition magazines.

- The main gun shields were made of 50 mm (2 in) plating.

- The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) walls and topped by a 20 mm (0.79 in) roof.

- The bridge above was unarmoured except a splinter-proof chart house.

- The three funnels had a steel glacis for splinter protection.

Armament

Compared to the Arethusa class it was weak, although they had four guns, the latter had two, but also six quicker guns. The 88 cm were a match for the 4-in (102 mm) at close range though, but they were there for AA defence mainly. Overall, aside their minelating capability they were rather weak for their size and tonnage.

-Four 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns in pedestal mounts allowing 30° elevation, centerline, enabling a four guns broadside. They were located on the forecastle, between the first and second funnel and superfiring pair aft. 45.3-kilogram (100 lb) shell at 840 meters per second (2,800 ft/s) and max 17,600 m (57,742 ft 9 in). 600 rounds were carried (150 per gun), of HE/AP types.

-Two 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns, centerline, astern of the funnels. They fired a 10 kg (22 lb) HE shell at 750 to 770 m/s (2,500 to 2,500 ft/s).

-Two 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes (four torpedoes in reserve) in swivel mount amidships. G7 type (1913), 430 lbs. (195 kg) WH at 4,370 yards/37 knots or 10,170 yards/27 knots.

-450 mines on two main deck rails and stern chutes. They were moored Hertz horn contact mines Type I-IV with various warheads and depht settings. The more common Type IV was 34 inches (86 cm) in diameter, 620 lbs. (281 kg) and fitted with a 180 lbs. (81.6 kg) Wet gun guncotton warhead. Read more on navweaps

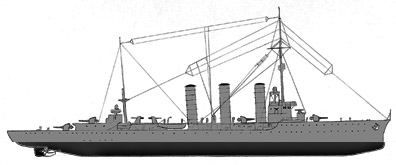

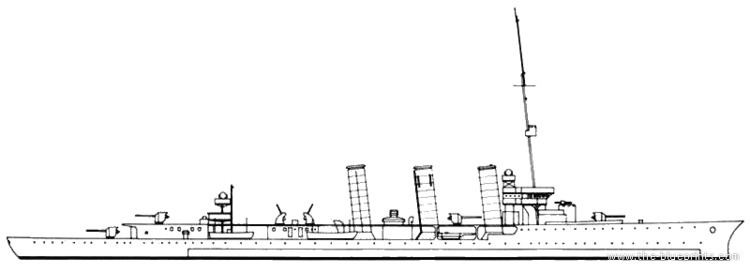

Author’s illustrator of the Brummer class

⚙ Brummer class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 140.4 x 13.2 x 6 m (472 x 46-47* x 16.5 feets) |

| Displacement | 4,385 tons standard, 5,856 tons Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 309 wartime |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts Parsons turbines, 6 Schulz-Thornycroft boilers, 33,000 hp. |

| Speed | 28 knots (40 km/h) |

| Range | 2300 nm @ 27 knots. |

| Armament | 4× 6-in/45 (15,2 cm SK), 2x 8,8cm, 2x 20-in TTs (500mm), 400 mines |

| Protection | Belt 40 mm, Bridge 15 mm, CT 100 mm |

General Assessment of the Brummer class

After commissioning with the High Seas Fleet they made a sortie in the North Sea in October 1916, and mining Norderney approaches in January 1917 as well as covering minesweeping operations until May 1916. By October 1917 they were part of the attack force of a British convoy to Norway. They were chosen by Scheer because of their high speed and autonomy. The battle of Lerwick saw them butchering the two escort destroyers and sink nine of the twelve cargo vessels of the convoy, the rest beong damaged but escaping.

This infuriated the British Admiralty when leaent and remobilized the fleet to better protect these and change their communication habits and planning. These were the shining points of their career, the rest was les glamorous. Still, the Navy had immense respect for both cruisers, largely due to their oversized propulsion. If their design was generaly excellent, making them among the best German cruisers, their armament was weak, if only in a cruiser duel. It was perfectly adequate to rampage convoys as seen.

All in all, these cruisers were several fold better than the previous Albatros, but they really had the occasion of testing their metal against equivalent ships. In that case, they lacked armament: Four 15 cm guns versus eight of the Wiesbaden class, built at the same time. They still were by far the best minelaying cruisers of the central Empire, and their concept was sound.

Due to their reputation, the entente powers obliged to cede them Brummer and Bremse for internment at Scapa Flow. Departing on 21 November 1918 under Ludwig von Reuter, they were scuttled like the rest of the fleet on 21 June 1919, at 13:05, never raised for scrapping and remains to this day on the bottom. Bremse sank at 14:30. She was however raised on 27 November 1929 and BU 1932–1933.

The Wiesbaden class in comparison (1915-16) packed a twice greater punch.

Links & Resources

Books

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1906–1921 – German section Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986)

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis NIS

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis NIS

Herwig, Holger (1980). “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Humanity Books.

Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. Ballantine Books.

Novik, Anton (1969). “The Story of the Cruisers Brummer and Bremse”. Warship International

Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. BSeaforth Publishing.

Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2004). Kleine Kreuzer 1903–1918: Bremen bis Cöln-Klasse. Bernard & Graefe Verlag.

Links

alchetron.com

scapa-flow.co.uk

militaer-wissen.de

scapaflowwrecks.com

Model Kits

HP Models 1:700 WM WW1 series sms brummer

Unfortunately HP is the only known to have cared about these ships. The gunnery school vessel of WW2 actually received more attention.

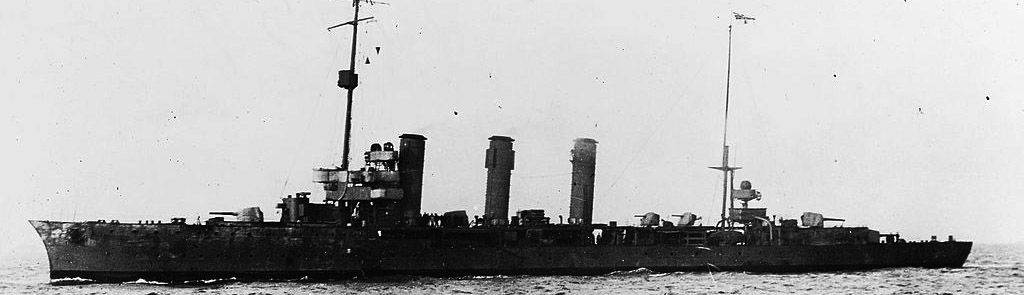

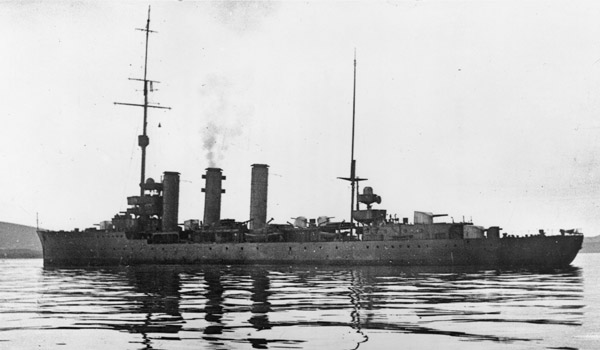

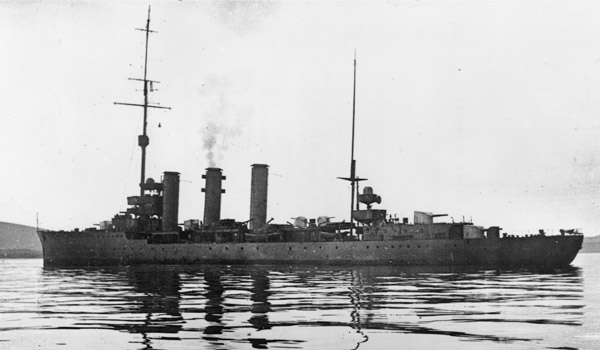

SMS Brummer

SMS Brummer

SMS Brummer was commissioned into the Hochessflotte (High Seas Fleet) on 2 April 1916 and trained enough to be ready in early May 1916, but on the 31 she did not followed the fleet to Jutland and went on training. It’s only in the autumn of 1917, almost one year later, that Admiral Reinhard Scheer decided to start a new tactic, sending surface raiders ti catch and destroy British convoys to Scandinavia. He wanted to divert escorts from the Atlantic to give more leeway to U-boats.

SMS Brummer at the time un command of Fregattenkapitän Leonhardi teamed with SMS Bremse again (Fregattenkapitän Westerkamp) chosen by Scheer and prepared for this operation. In addition to their performances, they looed like British light cruisers, and the captains in addition knew Royal Navy communication codes. The crews also painted the ships dark gray, the livery of these cruisers in the Royal Navy a the time. Nothing was left unanswered for a perfect deceiption plan.

Just after dawn on 17 October, SMS Brummer and Bremse arrived at cruise speed at a point which crossed the path of a westbound convoy 70 nautical miles (130 km; 81 mi) east of Lerwick. Hence later the “battle of Lerwick”. The convoy comprised twelve freighters escorted by the destroyers HMS Strongbow and HMS Mary Rose plus two armed trawlers. This seems to use ludrcrously weak, but at the time, convoy attack was only threatened by rare submersibles. Never the navy sent two surface cruisers for the task.

The German ruse worked enough for them to close in the convoy after a few exchanges by morse projector, reassuring the convoy commander about these to be friendly ships. Identification was not help by the way due to the early morning light. Recognition signals in rerturn from British vessels were however unanswered until the Germans eventually opened fire at a 2,700 m (8,900 ft), not point-blank range but close enough to almost guarantee first hits.

HMS Strongbow was hit by a first volley of both cruisers, eight 15 cm shells, which quickly were fatal, while Mary Rose closed in and by rapid fire, struggling to bring her to torpedo range, she was also dealt with. The two trawlers were armed with a single 3-in gun each and tried to protect the convoy the best theyr could, but now that the two shepherd dogs were out, the sheeps were ready for the slaughter. Bummer and Bremse rampeged into the convoy, even ifiring their 8,8 cm and torpedoes.

Recoignising the situation was hopeless, the two trawlers escaped with three merchant ships but the rest of the convoy was sunk entirely, nine vessels total, destroyers not included. Elise, one of the armed trawker coming from Bergen was fired on by Bremse while attempting to pick up survivors, something which was later told to the press and further exacerbate the ire of the admiralty. No wireless report was sent, wheras there was a squadron of sixteen light cruisers at sea, just south of the convoy. When known later, it was too late and Admiral David Beatty later said this was ‘luck was against us.’.

The British Admiralty was not informed of the attack the two cruisers informed the admiralty of their success while underway back home, and the message interecpted and decoded. Kaiser Wilhelm II congratulated the captains and Scheer for the idea and was overjoyed. The plan succeed as now, feating further raids, the RN decided to bolster the protection of its convoys with more vessels. But scheer, to maintain this fear, attempted more bold attacks all along the remainder of 1917 and 1918. None however achieved the same success.

Anyway, this feat, combined to the early successed for some far east cruisers like Emden, convinced the admiralty, of which any officers still crewed the Kriegsmarine years later, that commerce rauiding by cruisers and even battleships was a sound tactic for the new surface fleet. This was number one tactic to be applied by Erich Raeder, alongside a repeat of submarine warfare.

In late 1918, the Admiralstab again considered sending Brummer and Bremse on such mission, but in the Atlantic , where convoys were larger, and transiting to operate off the Azores with a pre-positioned oiler. They targeted the central Atlantic, out of U-boats. They were lightly defended on this leg and area. But eventually it was canceled as there was still some need to refuel them at sea, a dangerous task. If the oilers were spotted and sunk, the two cruisers would have been stranded there, easy targets fopr the entente;

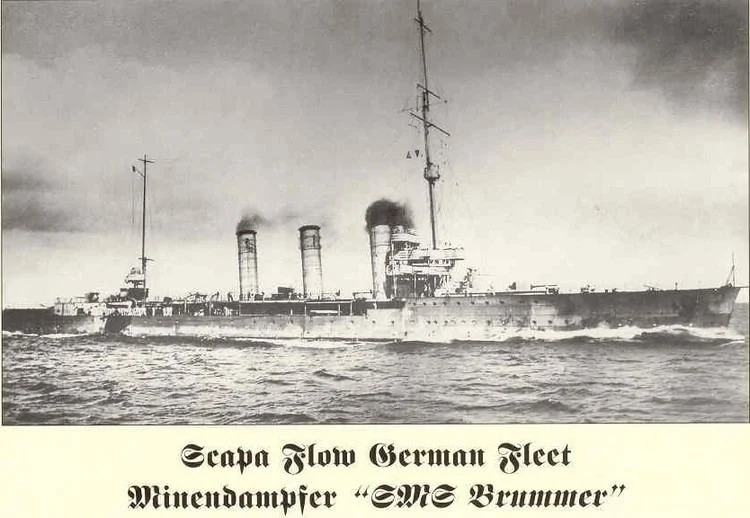

SMS Brummer entering Scapa Flow

Another issue identified was the clouds of red sparks emergig from their stacks when steaming over 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph), making them easy to spot by night, precluding a stealthy approach. SMS Brummer was also mobilized for thefinal sortie “for honor” of the High Seas Fleet in October 1918, cancelled due to mutinies in Wilhelmshaven. She was moved to Sassnitz; but due to their reputation, both were included in list of internment in Scapa Flow signified to the Admiralstab.

Brummer followed on 21 November 1918 the rest of the Hochseeflotte as part of a single file, heavily guarded by an international coaslition. Under RADM Ludwig von Reuter she arrived in the Firth of Forth later this day and escorted to their final leg into Scapa Flow. Wireless equipment was removed as well as breech blocks for the heavy guns and skeleton crews only for basic maintenance, the rest being sent home. Further crews cuts were made by Reuter fearing an uprising on board.

Unaware that the new extended deadline provided on 23rd, Reuter wated for the Home fleet to depart for exercizes and ordered this morning of 21 June, her order the crew to prepare the ship, so at 11:20 order was given for a scuttling, using mostly pumps or small explisive charges in the underbelly not to raise attention. Brummer sank at 13:05, never raised, still there under 36 m (118 ft), a nice recreational site for scuba divers.

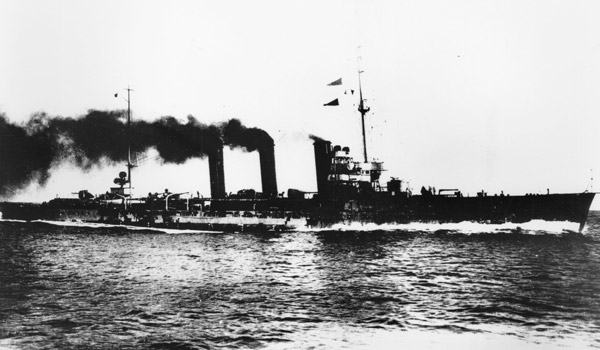

SMS Bremse

SMS Bremse

SMS Bremse was commissioned on 1 July 1916, and on 11–20 October she teamed with her sister Brummer for a first sortie in the North Sea. This was mostly a patrol, which was uneventful. On 10 January 1917, however, they woukd be used as intended, although in a mission not as bold as initially planned. They would lay a minefield off Norderney (Nördernee, an East Frisian Island off the North Sea coast of Germany). This was a defensive minelfield, certainly not an offensive one, close to the british coast. Together they laid around 900 mines.

On 1–13 March, they escorted minesweepers from Emden and Wilhelmshaven. The rest of 1917 saw no important mission but in October 1917 an important commerce raiding mission to diver the RN atttn,tion from submersible warfare in the Atlantic. At the time, Britain agreed to ship 250,000 tons of coal monthly to Norway in exchange of steel. These convoys started to cross the North Sea by late 1917 and were weakly escorted as consiered too far away for German raiders.

Scheer until then posted U-Boats along their supposed route, but in vain. Her wanted to try a dailight surface surprise raid and mobilized Bremse (Fregattenkapitän Westerkamp) and her sister Brummer for the task, being the longest-range, faster cruisers designed to resemble British light cruisers. All measures were taken for a perfect deceiption, and both cruisers as described above, arrived to the scene as planned at dawn on 17 October and the rampage was total.

Bremse during the Lerwick convoy attack in 1917 (shipbucket)

Brummer and Bremse were mobilized again for a commerce raiding mission into the Atlantic, based off the Azores and replenished at sea by an oiler to operate in the central Atlantic, where convoyed expecting no threats, were lightly defended. This (the limited radius of U-Boats) was recoignised in interwar and Dönitz would precisely specify a range extending to the central Atlantic which becalme in WW2 the famous “black pit” with limited escort and air cover.

The Admiralstab however canceled the plan due to several issues. On 2 April 1918 however, SMS Bremse, sent alone, laid a 304 mines field in the North Sea, and 150 on 11 April. Both made a final fleet sortie with the rest of the battle fleet on 22–24 April, in vain as they spotted no British vessel. On 11 May, SMS Bremse laid another minefield in the North Sea, with her almost full load of 400 mines and 420 mines on the 14th. Mobilized for the final sortie of the High Seas Fleet in October, it was cancelled due to mutinies.

Included in the list for internment she departed on 21 November 1918, being later rescorted on the RDV point by some 370 entente warships to the Firth of Forth and later Scapa Flow. Wireless was removed as her 15 cm guns breech blocks while part of her crew was sent back home. In June 1919, Von Reuter believed the deadline was about to expire on the 23 and prepared the scuttling, waiting for an opportunity to proceed. On 21 June, the departure of the British fleet for training maneuvers gave just the pretext he wanted and ordered at 11:20 the general scuttling order. It was done with celerity as all preparations has been made long ago in such eventuality.

Seeing Bremse prepared for the scuttling, an armed British naval party attempted to board her and close her bottom valves, but they arrived too late. They managed instead to blast off her anchor chains to have her taken in tow under guard from the destroyer HMS Venetia, trying to beach her. Indeed they managed to have her beach south of Cava, bu the slope here was such that her stern sank deep, so she rolled over and sank in 75 ft (23 m) of water at 14:30. Fortunately there was no casualty. Her bow emerging there was the only reminder for many mon,ths and years afterwards.

Ernest Cox bought salvage rights in the early 1920s but Bremse presented her own challenges. She was in part perched precariously on a sloping rock and could during salvage operations slip off and sinkat any moment, so Cox’s salvage team sealed her bulkheads, divided the hull into watertight compartments and pumped air in them, afetr the hull was patched up and fitted with an airlock. There was however still a load of oil covering her which needed disposal. With oxyacetylene torches, some was burnt, leading to an explosion, but none was injured.

By July 1929 superstructure being gone, she was turned upside down and compressors brought her to the surface, supported by 9-inch wires connected to the floating docks anchored on her port. However as success was coming, she toppled onto her side, heeled over and settled onto the rocks inshore, also causing an oil spill. It was decided to burn off the oil and the fire was later controilled while operations resumed, patching her again, pumping in air, and she again broke the surface. Considered too unsafe to tow to Rosyth she was brought to nearby Lyness on 30 November to be scrapped. So she outlived here sister by eleven years.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign