United Kingdom vs. Germany, 23 April 1918

The Zeebrugge Raid on the northern, Flemish coast remains one of the most spectacular and controversial feats of arms of the Great War. It was, as these words are written, about 100 years from now, and it still remembered vividly whereas four generations had passed. This is the equivalent of dixit Jeremy Clarkson’s “the greatest raid of all” for WW2. This event, which teethered with disaster and was heavily paid, finds indeed a certain resonance with the Saint Nazaire raid on 27-28 March 1942. In the specific case of Zeebruge, it was to permanently neutralize one of the main German naval bases on the Belgian coast, which then owned two important ones, Ostend (Oostend) and Zeebrugge. The first farther south being more difficult to access and locked by a serie of many coastal batteries, but Zeebruge, which also served as a seaplanes base, signaling the least acts of allied ships in the whole area, was well protected thanks to the massive curved pier of the harbor, and had very potent coastal batteries of its own too.

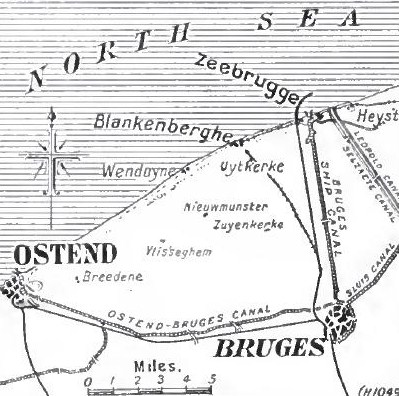

Bruges docks and approaches from Ostend and Zeebrugge

In Flemish, Zeebrugge literally means “Bruges on sea”: This is historically a canal linking Bruges to the sea, and the first tourist fishing port of the coast, became a seaside resort in the nineteenth century. That of Ostend was built later and was much longer and tortuous. The naval base of Zeebrugge was not well protected (if not naturally) and had a dozen submarines and torpedo boats passing through it and torpedo boats constantly threatening the traffic coming from the North Sea. But above all, its channel made the first outlet for the many submersibles based in Bruges. During the British Ypres salient ground offensive in the summer of 1917, a localized offensive was attempted to take Bruges. But the battle of Ypres which was to allow to create this breakthrough ended with the massacre of 200,000 men without the slightest significant advance (Bruges remained 40 km from the front). The coastal bombardments carried out by monitors being risky because of the German batteries, a “commando” type operation (the term did not exist at the time) was mounted to block the port and the canal in situ.

The idea of the raid came from Sir John Jellicoe, then Lord of the Sea, shortly before his sudden resignation in late 1917, then in constant conflict with the first Lord of the Admiralty and his convoy policy, Sir Eric Gedde. His idea, relayed by Sir Roger Keyes, commander of the port of Dover, was accepted in principle and prepared in the greatest secrecy. The obstruction of the access road from Bruges to the sea was issued in 1915 by Admiral Bacon, who has since been sacked. The latter did not envision a commando operation but a raid of monitors on the locks. The plan was rejected by the admiralty. Redefined by Keyes, the operation implemented three old reformed cruisers, used as obstruction plugs and filled with concrete (HMS Thetis, Iphigenia and Intrepid), a “newer” cruiser, the Vindictive, destined to disembark and support for diversionary navy troops, and two strong ferries from Dover, Iris and Daffodil.

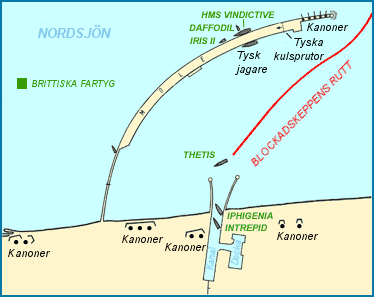

More detailed map of Zeebruge

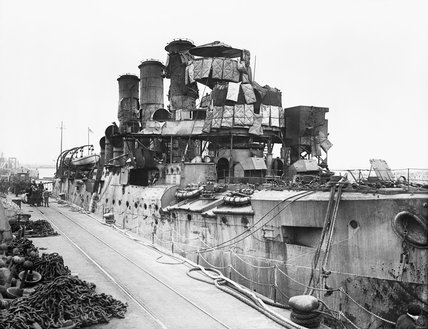

The three units were completely re-equipped for the assault, on a moonless night, supported by the fire of a few monitors. They were equipped with armored towers, with machine guns, sandbags and additional sheet metal plates protecting the firing positions and the bridge. A crew reduced to a few men embarked on the three old cruisers, prepared for their rapid scuttling, the Vindictive to assault on the pier. Finally, the viaduct and its railway linking the pier (nearly two kilometers long and 73 meters wide, protected by a huge parapet on the sea side), was to be destroyed by two reformed submersibles, the C1 and C3, which were to come ‘recess under its batteries. This was to add to the confusion and prevent reinforcements. All this diversion of the Mole was in principle to allow the three cruisers to win under fire enemy their respective positions of scuttling, men being evacuated by stars. Opposite, the German garrison of Zeebruge counted nearly 1000 men, including the servants of the big coastal pieces.

Particular attention was paid to the Vindictive. Because of the height of the parapet to be stormed (9 meters) there was no question of using his normal artillery. It reinforced its armored hune, equipped with fast parts and the bridge was equipped with 14 bridges. In total he embarked an arsenal of three Howitzer, 16 mortars, 10 grenade launchers, and grapple-launcher, the latter to grip the pier while the Royal Marines climb it with bridges, ropes and ladders , the Daffodil to press the cruiser against the pier for safety. Perils are innumerable, but enthusiasm for the audacity of the operation raises more than one objection. The operation is postponed twice due to bad weather. Finally, on the morning of 22 April, a motley flotilla of no less than 157 ships and boats left the port of Swin. This included, in addition to the assault ships escorted by many stars (74), 8 monitors, 8 light cruisers and no less than 45 destroyers and torpedo boats. The Royal Marines strength then consisted of 690 men divided among the three mole assault ships. Two other blockers were planned for Ostend.

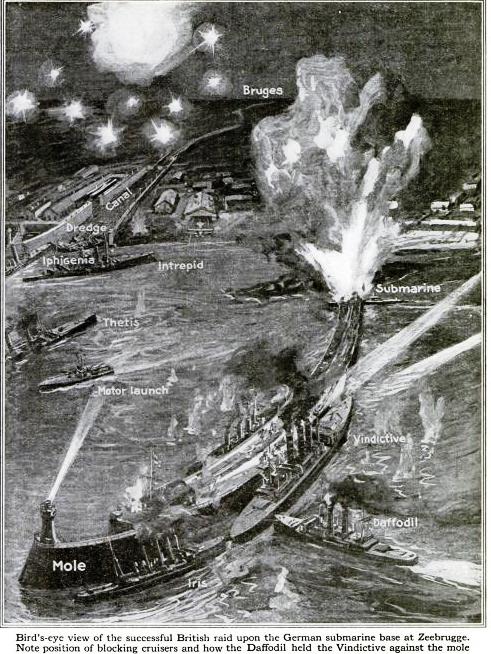

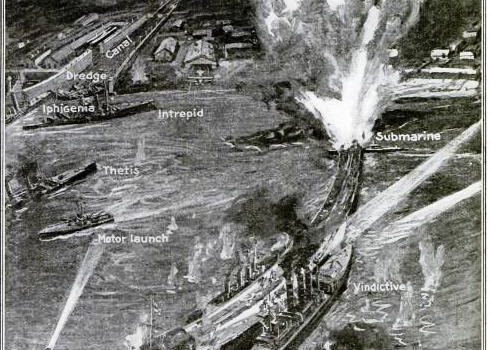

Zeebruge raid illustration, giving the position of most ships

After 7 hours of crossing, the commander Keyes sent to the fleet the signa of the beginning of operations (“saint georges for England”). At about 11 am, the stars began to unfold a smokescreen to protect the tempting targets of the six detached ships, but the wind suddenly became contrary. And while the three assault ships (Le Vindictive and the two Ferries) were only 300 meters from the pier, German flares, following the bombardment of the monitors (inefficiently) at the alleged positions of the batteries, were drawn, illuminating beautifully the three English ships approaching at a pace. At once they were met by a fire of hell, and their bridges swept under a hail of shells. Despite this, they continued their approach to their supposed positions (because they found themselves in confusion and smoke, more than 160 meters from their intended positions, towards the middle of the pier.). Devastated, its footbridges torn off, the Vindictive managed to dock and the Royal Marines to deploy under the fire of the machine guns, throwing their grapples and ladders on the high concrete parapet.

Aerial photo of the Zeebruge entrance, blocked by the sacrificed cruiser

The assault, lack of the support of the arms of the cruisers, destroyed by the German fire, turns short; The men who arrive at the top of the ladders and gangways are systematically shot down by machine gun nests and shooters posted on the roofs of the pier hangars. The rolling fire of small arms will last nearly an hour. Meanwhile, the Iris failed to dock the pier, and his commander decided to moor behind the Vindictive to transfer his men when at about 1 am, the order of withdrawal was decided. The 4th battalion had tried to take the batteries at the foot of the lighthouse, at the end of the pier, never reached it: The men were mowed either at the top of the parapet, or while going down under enemy fire, or running against the a real trench erected by the Germans and under the rolling fire of a destroyer at the dock, slowed down by crates and barbed wire.

On the other hand, the viaduct, at the other end, was effectively destroyed by the C3. The C1, too late, turned around. Without neutralizing the pieces, after the withdrawal of the cruiser, the three blockers were in turn taken under a deadly fire and the first, the Thetis, prematurely scuttled, without reaching their desired position. He had indeed been caught in the nets antitorpilles he had carried with him but twisted his propellers. He drifted on a sandbank before being temporarily immobilized. His commander managed to scuttle him at the entrance of the channel to the lock.

If the bloody assault of the big dyke was above all a diversion, the imperfect blockage of the three old cruisers was not a long time an embarrassment for the exit of the German light units. The operation was therefore mostly a failure disguised as a victory for reasons of propaganda…

The other two passed through the breach created by the Thetis and were relatively spared by the German fire, entertained by the many stars who were running at full speed in the harbor and evacuated the men. Arrived at their positions previously planned, they obstructed the passage between the harbor and the lock, narrower, but still far from them, and in a position that made them bypassable by light units. For their part, the Iris, then the Vindictive and the Daffodil left the pier under a curtain of thick smoke that saved them from certain destruction.

Aerial photograph after Zeebrugge Raid (IWM)

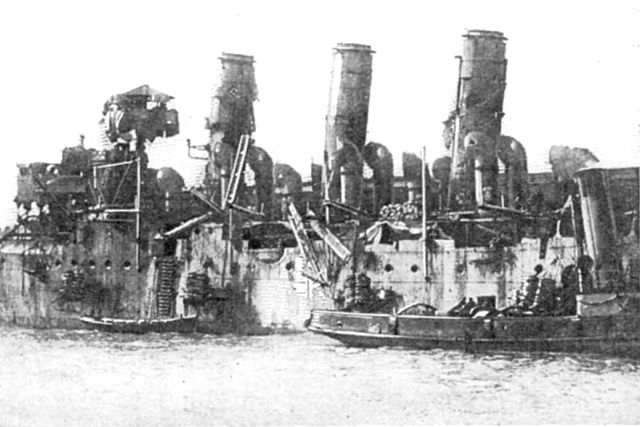

In the end, the three assault ships, riddled with shrapnells, completely devastated and covered with corpses and agonising wounded men, the decks soaking wet of blood, returned to Dover under the cheers of the crowd. The blocking cruisers had failed to stop the exits from Bruges, causing only a few days’ inconvenience, and the Ostend operation had been a bitter failure: The Germans had simply moved the buoy of Ostend, all lights out, 2400 meters further, and blocking ships had come aground in the dunes… May 10 will a new operation against Ostend was planned and eventually launched with the Vindictive as a blockship. But the operation was also a bloody failure.

Photos of the Vindictive and damage after the raid

In the end, three days after the Zeebrugge operation, the dredging around the scuttled cruisers allowed the torpedo boats to cross the channel and reach the open sea. When the coastal submersibles, they were forced only a few maneuvers to cross the channel on the first day of the English attack. However, the British press made this raid a success, cleverly exploited by propaganda. No less than eight Victoria Cross were awarded to commandos, never seen before for an hour-long operation. In the end, it was the Germans themselves who, by evacuating the area, blocked the canal for two and a half years.

Read More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeebrugge_Raid

http://www.greatwar.co.uk/battles/yser/zeebrugge-ostend-raid.htm

http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/zeebrugge.htm

Model of the Vindictive – IMW

http://www.fr.naval-encyclopedia.com/batailles-premiere-guerre-mondiale.php

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

“The Zeebrugge Raid on the Walloon” coast is not correct. Zeebrugge is in flanders, the north region of Belgium

Hello David

Corrected to Flemish ! Thanks,

Really i have no excuse, my great grandfather was a walloon fisher and he spoke perfect flemish, i should know better.

Cheers !