US Navy Submersibles, USS Sargo, Saury, Spearfish, Sculpin, Squalus, Swordfish, Seadragon, Sealion, Searaven, Seawolf SS-188-197 (1937-48)

US Navy Submersibles, USS Sargo, Saury, Spearfish, Sculpin, Squalus, Swordfish, Seadragon, Sealion, Searaven, Seawolf SS-188-197 (1937-48)WW2 US submarines:

O class | R class | S class | T class | Barracuda class | USS Argonaut | Narwhal class | USS Dolphin | Cachalot class | Porpoise class | Salmon class | Sargo class | Tambor class | Mackerel class | Gato class | Balao class | Tench classThe Sargo-class were among the first United States submarines sent into action after the attack on Pearl Harbor, with very active war patrols the very day after the attack, from the Philippines. USS Swordfish (SS-193) was the first USN submarine to sink a Japanese ship in World War II. Design wise they were part of the large “S” class, the last prewar submarine class, followed by the Tambor and wartime Gato class. They were similar to the previous Salmon class minor slightly larger hulls, varied powerplants for comparative tests, and a few details. They were built between 1937 and 1939 at Electric Boat (Conn.) and portsmouth NYd Kittery (Maine) on the east coast and Mare Island on the west coast, first laid down in 1937, last completed in December 1939.

Same top speed of 21 knots surfaced and impressive range of 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) which opened them Japanese home waters from Midway and Pearl Harbour. They had reliable propulsion plants (in WW2) and a sound construction using almost entirely welding. These were an important step towards the standard US fleet submarine. Their similarity with the Salmon class had them called 1st and 2nd group of the S class in some publications, making for a total of 16 fleet subs (6 Salmon, 10 Sargo).

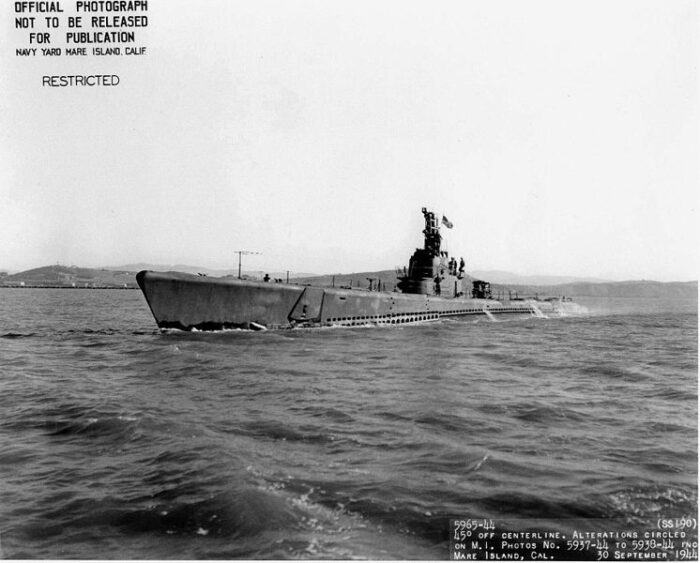

USS Searaven on sea trials on 13 May 1940.

Development

Most of their features repeated the Salmons, so they were “near sisters”, except for the return to a full diesel-electric drive for the last four boats, and adoption of the improved Sargo battery design with more cells. This gave them extra ranbge and autonomy underwater, at the price of slighlty lower top speed when submerged. They also kept the armament of the previous boats, which inaugured an extra pair of torpedo tubes aft and greater capacity overall.

The original Mark 21 3-inch (76 mm)/50 caliber deck gun however was judged too “puny” in service. It could take an hour to sink a moderately large steamer, whereas they had no hope defeating anything larger than a small patroller or armed sampan. It juts lacked the punch either to finish off a crippled vessel or deal directly with small targets. It endangered the crew when surfaced. A 3-in gun was suitable in general in a 600t submarine, but WWI large U-Boats proved already they could have up to two 15 cm guns for a not that far tonnage. It was replaced in wartime by the Mark 9 4-inch (102 mm)/50 caliber gun, moslty removed from former WWI S-boat being relegated to training. It seems at least one or two tested also the standard 5-in deck gun.

Engineering Differences with the previous Salmon class

Composite direct-drive/diesel-electric

The first group of six Sargo class (three ordered at Electric Boat, two at Portsmouth and one at Mare Island, all in May (two), September (two) and October 1937 (last two) were driven by a composite direct-drive and diesel-electric plant, with two engines in each mode as the Salmons. This arrangement enabled the two main engines of the forward engine room to drive generators and the after engine room had two side-by-side engines clutched to reduction gears placed forward of the engines. They were isolated by with vibration free hydraulic clutches. There were also two high-speed electric motors which were driven by generating diesel or batteries and also connected to each reduction gear.

Looking for a full diesel-electric plant

The Bureau of Steam Engineering (BuEng) worked with the General Board in order to adopt for the next batch a full diesel-electric plant for simplification. Not all agreed to this. Admiral Thomas C. Hart was the most vocal in opposition, and at the time, the only experienced submariner part of the rather conservative, surface officers of the General Board. He argued that flooding would easily disable the whole diesel-electric system due to shortcurcuits, even after a mild depht charge detonation, with valves and pipes breaking.

There were also technical problems against the use of two large direct-drive diesels instead of a four-engine composite system, an the first was a diesel powerful enough and reliable enough to replace existing ones. None, if coupled, could reach the desired 21-knot top speed. The other issue is even if such powerful diesels existed, there was no vibration-isolating hydraulic clutches capable of transmitting that power. Some also argued that it was always problematic to clutch two engines to each shaft. This was demonstrated in the past.

Despite of this, a full diesel-electric plant was adopted for the nex four boats of the Sargo class, Seadrong and Sealion from EB and Searave, Seawolf from Portsmouth (state yard). The arrangement of the latter would remained standard for the next Tambor, Mackerel, Gato, Tench and Balao classes, even the last coinventional boats of the 1950s.

Electric Boats’s troublesome HOR diesels

Four of the class in addition, USS Sargo and Saury as well as Spearfish, and Seadragon, all from Eelectric Boat in Groton, were equipped with the troublesome Hooven-Owens-Rentschler (HOR) double-acting diesels. Eletric Boat continued meanwhile tikering with smaller engines capable of far more power in the idea of replacing four by six or even eight of these and reached 22 knots or more, or just keep 21 knots and save space: These were double-acting system were in fact derived from a steam engine. They had nine-cylinder with a power stroke in both directions of the piston. But the Hooven-Owens-Rentschler (HOR) double-acting engine. Albeit it generated twice as much horsepower as for a conventional in-line or V-type diesel, the new promising engine was problematic.

Long story short they proved unreliable in service. Still relatively recent and lacking extensive testing, they proved immature and had design and manufacturing issues, result of a rushed adaptation from steam to internal combustion. The much higher energy from oil combustion was too much for the block, which happened to vibrate excessively, putting wear and tear on the whole power unit, as a result of the twin stoke imbalance in the combustion chamber. The mounts broke down, the drive train was severely stressed. To boot, improper manufacture of the gearing resulted often in broken gear teeth.

The Navy stuck to Winton diesels

Meanwhile the Navy stood to its gun, via Portsmouth and Mare Island, and continued to recommand use General Motors-Winton diesels. These GM-Winton 16-248 V16 were developed for years now, and under constant feedback and fixing gradually all teething issues with the design managed to overcome all its previous issues of vibrations and noise, loose tolerances manufacting among others. This was, in 1938, a fairly reliable and rugged engine. A complete contrast to the largely unrpoven Hooven-Owens-Rentschler (HOR) which were a liability on trials. Fortunately it was revealed in 1939-40, but no refits were done at the time, at least until the war came out. They soldiered on in 1942 with these. At last in early 1943 during their major overhaul reconstruction, they swapped, but not for GM-Winton 16-278A diesels. Instead they were given GM Cleveland Diesel 16-278A engines. They were more advances, but in this, the Navy failed to create a uniformally powered class, like the previous Salmons, destrimental to the supply and logistic chain.

The adoption of new batteries

There was a second innovation: BuEng designed a new lead-acid battery capable of resisting battle damage and with better water resistance. The previous Salmon class had two 120-cell battery units, and in the new design, the smaller batteries were a bit more, 128 per unit. This was known as the “Sargo battery” as tested first on USS Sargo. The new battery cell was suggested while just commissioned by her first captain Lieutenant E. E. Yeomans. He wanted instead a single hard rubber case around each cell, two concentric hard rubber cases, with a layer of soft rubber between them to sandwich all vibrations even better.

The nightmare was a sulfuric acid leakage if a case cracked open in depth-charging concussion. Leaking sulfuric acid would be capable of corroding steel, burning the skin of crew members it came into contact with, and if mixed with any seawater in the bilges it would generate poisonous chlorine gas. This proved a success, although more intensive in terms of manufacturing. This remained the standard battery design until the new 1950s GUPPY batteries of the cold war. The capacity was increased to 126 cells instead to raise the nominal voltage from 250 volts to 270 volts, translated into a standard since, even with backup batteries of modern nuclear submarines… to this day.

Design of the class

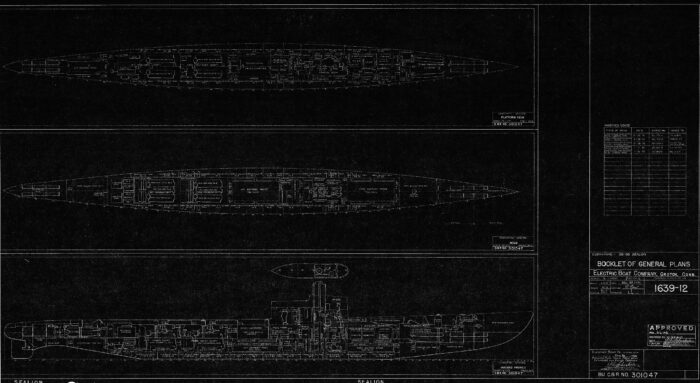

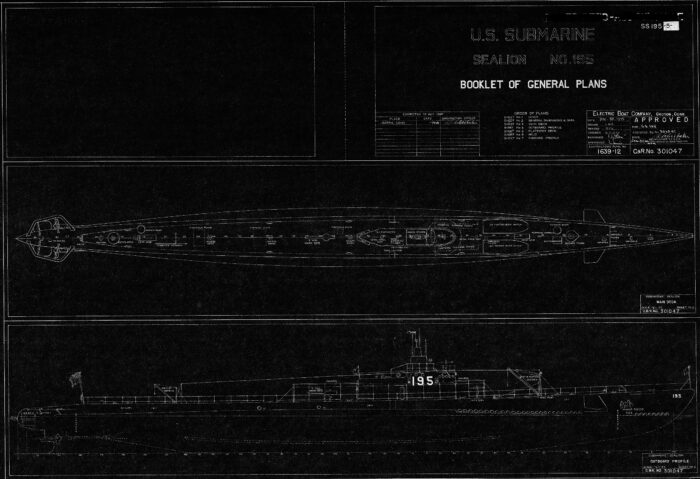

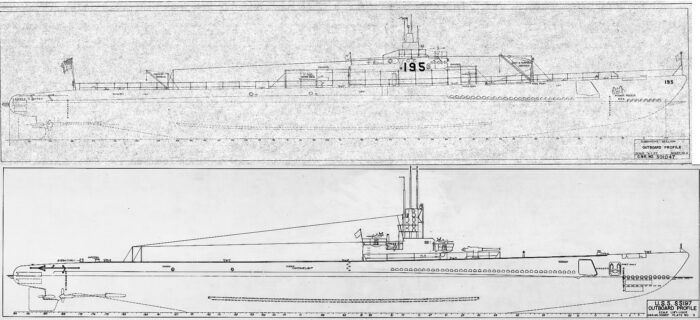

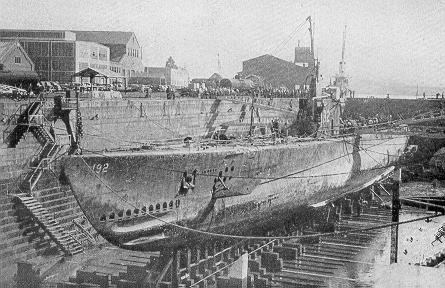

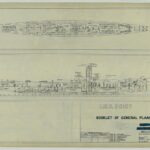

USS Sealion’s booklet of general plans in 1937

Hull and general design

The Sargo class were slightly heavier thn the Salmons at 1,450 tons (1473 t) standard, surfaced and 2,350 tons (2,388 t) submerged versus 1,435 long tons standard, 2,198 long tons submerged

They were also slightly longer at 310 feet 6 inches (94.64 meters) versus 308 feet and 10 inches wider (26 feet 10 inches or 8 meters) versus 26 ft (7.96) and draftier at 16 ft 7½ in up to 16 feet 8 inches or 5.08 m versus 15 ft 8 in (4.78 m).

Powerplant

So, to resume, four Electric Boat Subs. (SS188-191 and SS 196) has four Hooven-Owens-Rentschler (H.O.R.) and four electric motors with two direct-drive, two driving electrical generators.

The remainder S-192-195 as well as S197 had General Motors diesel engines and four electric motors, all driving electrical generators.

All generated 1,535 hp (1,145 kW) each, and this made for SS188 to 192: 5,500 hp surfaced and 2,740 hp submerged, but for SS193-197: 5,200 hp surfaced, same submerged.

After the diesels came four high-speed geared electric motors, 685 hp (511 kW) each.

Then came two auxiliary diesel generators, 258 kW (346 hp) each to reload the batteries.

The boats all had the same 126-cell “Sargo batteries” which were considerably improved, and “battle-proof”.

All this was passed onto two shafts with a net 5,200–5,500 shp (3,900–4,100 kW) surfaced as seen above and 2,740 hp (2,040 kW) submerged for all boats.

They had the same top speed surfaced as the Salmons but less submerged, 8.75 (16 kph) instead 9 knots (17 km/h).

Comparison between subs, before and after overhaul.

Armament

The S-class at large shared an arrangement wanted by sub captains for a long time and thought to be impossible at first. Four torpedo tubes in the bow, four in the stern, all reloadable. The easy solution would have been to shoehorn extra external tubes (non reloadable) and manage to have more on the bow and stern (The T class British method), but this was not popular with the crews. The previous Porpoise and Cachalot class had four tubes in the bow and two in the ster plus 16 torpedoes total. Design solutions found for the Salmon class “guaranteed” 24 torpedoes, with eight already pre-loaded in tubes, and eleven reloads in the pressure hull, a remainder four stored close to the conning tower in vertical tubes.

The latter solution was quickly found useless as the handling when surfaced required hard, dangerous work and perfect conditions. The remaining issue was the type used, the standard Mark 14 pushed by the ordnance for adoption on all S class in 1940. They were abysmal in 1942-43, until their numerous issues were fixed. Fortunately there were still stocks of the older Mark 10 aplenty, that sub captains back from patrols utterly frustrated asked again and again.

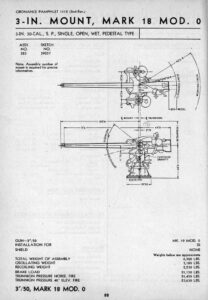

3-inch/50-caliber gun Mk 17/18

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Marks 17 and 18 were installed on the Cachalot class, first used on R-class submarines launched in 1918–1919.

This proven ordnance went right back to the O class and its 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun, non-retractable in later batches. The new 50 caliber model became pretty standard, with a design going back to 1898 when designed, Mark 6 for the Electric Boat models. The 3″/50-caliber Marks 17 and 18 were installed on the Cachalot class, first used on R-class submarines launched in 1918–1919.

The Mark 17 guns had a Mark 11 mounting and the Mark 18 guns had the Mark 18 mounting. Importantly enough, the gun was located aft of the conning tower. Image: 3-in/50 Mark 18 specs and sheet, src HNSA via navweaps.

⚙ specifications 3-in/50 Mark 18 |

|

| Weight | 6,500 Ibs |

| Barrel length | 120 inches |

| Elevation/Traverse | -15/+40 degrees |

| Loading system | Manual, vertical sliding wedge type breech |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,700 fps (823 mps) |

| Range | 14,000 yards (12,802 m) at 33° |

| Guidance | Optical |

| Crew | 6 |

| Round | 24 lbs. (10.9 kg) AP, HC, AA, Illum. |

| Rate of Fire | 15 – 20 rounds per minute |

Mark 10 Torpedoes

These boats were capable of firing the 21-inches Mark 10 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark 10, a 1917 design entering service in 1918. From 1927 these were the Mod 3, last designed by Bliss and manufactured by the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport. They equipped R and S boats, most V Boats, The Cachalot, Porpoise and others, and soldiered in World War II as a trusted straight course unlike the infamous Mark 14. Before the latter had its defaults ironed out in 1942-43, the Mark 10 was in high demand and stocks starting to dwindle down rapidly. Production was maintained until 1943.

⚙ specifications Mark 10 Mod 3

Weight: 2,215 lbs. (1,005 kg)

Dimensions: 183 in (4.953 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater

Range/speed setting: 3,500 yards (3,200 m) / 36 knots

Warhead: 497 lbs. (225 kg) TNT or 485 lbs. (220 kg) Torpex

Guidance: Mark 13 Mod 1 gyro

Mark 14 Torpedoes

In 1941 she carried the Mark 14, entering service in 1930. Designed replacement for the Mark 10, this was the new standard. Unfortunately the model was infamous for its legendary unreliability, explaining the poor results obtained in 1942 and until mid to late 1943; Long story short, the Mark 14 was a revolutionary new model that was tailored to use a gryroscope combined with a magnetic pistol. The principle was not to detonate on impact, but use magnetoc proximity of the enemy hull to explode ideally under the hull of the target. This way, it was easier to break its hull instead of just making contact below the waterline. These torpedoes were designed at the Naval Torpedo Station Newport, Rhode Island from 1930 and considered state of the art, benefiting from a $143,000 budget for its development.

Production was pushed forward after testings, and at 20 ft 6 in (6.25 m), it was incompatible with older submarines’ 15 ft 3 in (4.65 m) torpedo tubes, like the R and O classes. It was also the best performer, capable of 4,500 yards (4.1 km) at 46 knots (85 km/h).

Lots of promises, but the war proved that testings had not been thorough and the rate of misses compared to the Mark 10 became obvious in reports in 1942, this infuriated many captains that disabled the magnetic pistol, but did not solve the problem as it was proved later that their too fragile impact fuse was also faulty.

Responsibility lied with the Bureau of Ordnance, which specified an unrealistically rigid magnetic exploder sensitivity setting while not providing enough funding to a feeble testing program. BuOrd had a hard time later accepting it and enable a new serie of tests, which were mostly from private initiatives.

Only by late 1943 and early 1944 most problems had been allegedly fixed, so that the 1944 Mark 14 at least allowed captains to claim far more kills. The “mark 14 affair” sparkled a lot of controversy postwar and it’s not over.

⚙ specifications Mark 14 TORPEDO

Weight: Mod 0: 3,000 lbs. (1,361 kg), Mod 3: 3,061 lbs. (1,388 kg)

Dimensions: 20 ft 6 in (6.248 m)

Propulsion: Wet-heater steam turbine

Range/speed setting: 4,500 yards (4,100 m)/46 knots, 9,000 yards (8,200 m)/31 knots or 30.5 knots

Warhead Mod 0: 507 lbs. (230 kg) TNT, Mod 3: 668 lbs. (303 kg) TPX

Guidance: Mark 12 Mod 3 gyro

Mark 12 Mines Mod 3

Submarine launched mine designed to be launched from a standard 21 inches or 53.3 cm torpedo tube. They were cylindrical, with an aluminum case. The model was derived from war prize German models in the 1920s, the S-type mines. The Mod 1 was an (airborne) parachute mine, M3 was the submarine type. Some were delivered to Manila just before the Japanese invasion and were dumped into deep water to prevent capture. In total, when carrying just a few spare torpedoes in minelaying missions, the S-class could carry a total of 32 Mark 12 mines.

⚙ specifications Mark 12 mod 3 Mines

Dimensions: 94.25 inches long, 20.8 inches wide. (2,394 m x 0.53 m).

Weight: 1,445 lbs. (655 kg), 1,100 lbs. (499 kg) TNT charge or 1,595 lbs. (723 kg) with a 1,250 lbs. (567 kg) Torpex charge.

Pissibly replaced in 1944 by the Mark 24 submarine launched ground mine. src

Sensors

QCC sonar: The QC/JK gear was located in the Conning Tower, companion units with the QC gear as active/passive sonar and JK gear (passive only). Raides and lowered by a hydraulic system, training by electric motor controlled by handle in the operating station. QCC: No data.

JK sonar: The JK/QC combination projector is mounted portside. The JK face is just like QB. The QC face contains small nickel tubes, which change size when a sound wave strikes this face. (The NM projector, mounted on the hull centerline in the forward trim tank, is used only for echo sounding.)

Se the full reference here

Modernizations

USS Sculpin overhaul details

In 1942-1943, all boats underwent a reconstruciton of the conning tower (see the Salmon class for the controversy) and their 3-in/50 Mk.17 and two 12.7mm/90 Browning AA heavy machine guns were replaced by a 4-inches(102mm)/50 Mk 9 deck gun and in some cased, a 5-inches(127mm)/25 Mk 17 deck gun as well as two 20mm/70 Mk 4 Oerlikon AA guns mounted on platforms for and aft of the sail. They also received the SD and SJ radars. Later it was swapped for the Mk 10 in 1945 and they had theor sonar upgraded to the QCD model.

USS Seawolf in 1944 after refit at Mare Island, original plans

⚙ Sargo class specifications |

|

| Displacement | 1,450 tons (1473 t) surfaced, 2,350 tons (2,388 t) submerged |

| Dimensions | 310 ft 6 in x 26 ft 10 in x 16 ft 7½ in/16 ft 8 in (94.64 x 8.18 x 5.08) |

| Propulsion | 4 diesels 1,535 hp, 4 EM 659 hp, 2x aux. DG. 236 hp, 2x 126 cell batteries |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h) surfaced, 9 knots (17 km/h) submerged |

| Range | 11,000 nm (20,000 km) at 10 knots |

| Max service depth | 250 ft (76 m), crush depht 150 ft (140 m) est. |

| Armament | 8x 21-in TTs (4 fwd, 4 aft, 24 torpedoes), 1×3-in/50 deck gun, 4x 0.5-in HMG AA |

| Sensors | QCC-JK suite, SD-SJ radars 1942-43 |

| Test Depth | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Crew | 5 officers and 54 ratings |

General Evaluation

USS Sargo in 1938

The Sargo class were a gradual, if limited improvement over the Salmon class. Construction and armament remained the same, but choices in powerplants were confirmed, the design of the conning tower as well, adopting Electric Boat’s design, and standardizing a configuration of full diesel-electric plant and the “Sargo battery” with units of 126 cells, much more secure and “battle proof” to any sulfuric acid leak when taking depht charge concussion damage.

They were large fleet boats with the same excellent surface speed and range, being capable to reach and stay cruising in the Japanese home islands from Midway. Their only limitations were engines issues until fixed for the four Electric Boat subs, a puny 3-inches/50 gun too weak to do any impression (and also replaced), and the awful Mark 14 torpedoes until they were fixed. Despite many missed occasions in 1942, their kill rate was on par with the previous Salmon class, making the collective S-class(II), the most successful interwar submarine class of WW2.

And since they soldiered on from December 7, 1941 to September 1945, they were among the most decorated individually. It is often forgotten than the more numerous Hato/Tench/Balao entered service much later. The Salmon/Sargo represented the bulk of the US submarine force in 1941 and it showed in the number of patrols, ships sunk and battle stars gained, setting new records.

In addition they were safer than earlier designs, notably to a construction that prevented oil leakages after depht-charing, safer batteries, and reliable engines. Only two were lost to enemy action (one direct), one by friendly fire, one by error on trials (and still saw service in wartime after being refloated and renamed).

Periscope view of a sinking steamer by USS Seawolf.

Appearance

USS Sargo

US submarines were rarely “camouflaged” due to their small size and unlikely chances to be caught while surfaced, albeit patterns were used quite soon to try to blend them with the surroundings. Prewar popular scheme were Measure 9, overall dark grey/black above waterline surfaces and anti-fouling red primer for the hull underwater. With early wartime experience if the weather was clear in relatively shallow waters, the red of the hull could be picked up by an aircraft. Measure 10 thus saw the hull painted in a lighter shade of dark blue, the conning tower in navy blue, as black as also found easy to pick. But the entire hull was painted dark grey. In 1944-45 some had the MS (Measure) 32/3SSB, with light grey overalls, same underwater hull as above, and black aft section as well as the drive planes forward.

Measure 32/3SSB was all black.

USS Sargo after her Mare Island arsenal overhaul, note the same MS 9 livery.

The Salmon class were noted officially painted with measure 9 for all their service, except USS Salmon which in 1944 was applied the MS 32/3SS-B scheme.

In 1938-1942 they had their number painted white on the sail. Post-overhaul with their new smaller sail the number was plated on the prow in the same color as the hull, dark grey/black overall. The wooden decks and platforms were painted the same.

The Sargo class were painted the same, MS.9 even after overhaul. There is not other pattern reported.

See also

Books

Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis NIP

Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990 Greenwood Press.

Alden, John D., Commander, USN (retired). The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy Annapolis NIP 1979

Johnston, “No More Heads or Tails”, pp. 53–54

Blair, Clay, Jr. Silent Victory. New York: Bantam, 1976

Lenton, H. T. American Submarines (Navies of the Second World War) Doubleday, 1973

Silverstone, Paul H. U.S. Warships of World War II Ian Allan, 1965

Schlesman, Bruce and Roberts, Stephen S., “Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants” Greenwood Press, 1991

Campbell, John Naval Weapons of World War Two. Naval Institute Press, 1985

The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy: Design and Construction History Hardcover 1979 by John D. Alden.

Gardiner, Robert, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946, Conway Maritime Press, 1980.

Links

wwii-submarine-operations.tripod.com

on navypedia.org/

on pwencycl.kgbudge.com/ (pacific war)

on pigboats.com/

on uboat.net

A VISUAL GUIDE TO THE U.S. FLEET SUBMARINES PART THREE: SALMON & SARGO CLASSES 1936-1945 BY DAVID L. JOHNSTON

on en.wikipedia.org/

USS Sargo on navsource.org

on commons.wikimedia.org

Model Kits

on scalemates, Blue Ridge Models 1:700

Also: US Navy Booklet of General Plans for USS Seawolf post-overhaul, Portsmouth NyD. Note: They are available on wikimedia CC, unlike prewar (1937) plans for the same boats.

on sdmodelmakers.com/

The Sargo class in Action

USS Sargo SS-188

USS Sargo SS-188

USS Sargo (SS-188) was laid down at Electric Boat, Groton, Connecticut on 12 May 1937, launched on 6 June 1938 and completed on 7 February 1939. After shakedown (eastern seaboard, South America) she departed Portsmouth in July 1939 for the west coast and Pacific Fleet via Panama, San Diego, and made a practice 40-day war patrol between Midway and the Marshall, fall 1941. She left Pearl Harbor on 23 October 1941 for Manila (10 November) and was present there on 7 December.

Under captain Tyrell D. Jacobs (torpedo specialist) she started her first war patrol to French Indochina and Netherlands East Indies. Off Cam Ranh Bay she was vectored to three cruisers on the 14th but missed the TDV point. She spotted and fired on a freighter, a Mark 14 which prematurely exploded 18 seconds later so he switched to contact pistol. On the 24th two freighters, fired two, missed. Lost depth control and broached, firedstern tubes, missed. On the 25th, spotted two more, missed firing position and later spotted another two, fired stern torpedoes from 900 yards (800 m) but missed. The skipper discovered they ran too deep and they started to modify their settings. On 26 December, good position but bad weather prevented an attack. He fired on a tanker later but missed again with perfect condition, and in sheer exasperation signaled headquarters his ideas about Mark 14’s reliability on open radio. This was the first serious shot fired at the infamous Mark 14 in thi war, by a torpedo specialist. On 20 January 1942 he assisted a rescue (S-36, ran aground on Taku Reef) and headed for Java, Soerabaja on 25 January for supply and ending her patrol. First thing he unloaded all his reload torpedoes and 3-inch ammunition, took a million rounds of .30-caliber for the Philippines instead. He only kept two bow torpedoes. He sailed on 5 February to Polloc Harbor, delivered his cargo to Mindanao, and back to Soerabaja with 24 Boeing B-17 specialists from Clark Field.

He then left Soerabaja with 31 passengers on 25 February for Australia, arrived off Freemantle on 4 March 1942 when misidentified and attacked by a RAAF Lockheed Hudson at 13:38 while surfaced. Crash-dived, two bombs exploded whule under 40 feet (12 m), lifted her stern off water, out of control, plunged to 300 feet (91 m) but the crew recoreved her in time. She broached spectacularly and submerged under a new attack, dtonation close to her CT while under 50 feet, optics broken on periscopes, conning tower door and upper hatch jammed, lights and gauges, electrical power down. She remained submerged until after nightfall and made it into Fremantle on 5 March 1942.

For her third war patrol she was under command of Richard V. Gregory, detailed to guard Darwin’s approaches as panic spread over a potential Japanese invasion of Australia but nothing materialized. On 8 June he departed for a 4th patrol in the Gulf of Siam, off Malaya. Missed a small tanker, back on 2 August.

5th patrol (27 August-25 October): Celebes Sea, South China Sea. Submerged attack off Vietnam 25 September, fired at 4,472-ton cargo Teibo Maru, one hit, 3 more misssed, one became circular, exploded off her stern. Surfaced and finished her off with gunfire, reporting the weakness of his deck gun when back.

He 6th War patrol started under command of Lt. Edward S. Carmick, departing on 29 November 1942 from Brisbane to Hawaii. Last day of 1942, submerged attack on a tanker off Tingmon Island, fire four torpedoes, heard explosions, reported ship breaking up but JANAC did not confirmed. Arrived at Pearl Harbor on 21 January 1943, left for San Francisco, Mare Island for major overhaul. She was back in Hawaii on 10 May 1943, departed 27 May, 7th patrol to Truk-Guam-Saipan. 13 June, intercepted a convoy escorted by a subchaser. Submerged attack, sank the liner Konan Maru SW of Palau. On the 14th, fired on another, but not confirmed, forced to dive to escape subchaser. Back at Midway Island on 9 July, credited a 5,200t ship. Left on 1 August for 8th patrol for Truk, Mariana Islands, no contacts, back to Pearl 15 September for refit. Under new captain Philip W. Garnett she started her 9th war patrol from 15 October to 9 December 1943 off Formosa and Philippine Sea. 9 November, torpedoed Tago Maru, finished off with gunfire. 11 Nov. torpedoed and sank passenger ship Kosei Maru off Okinawa. Picked up a Japanese soldier clinging to floating debris, back to Pearl Harbor on 9 December 1943. 10th patrol was from 26 January to 12 March 1944 north of Palau Islands. Faled to intercept Admiral Koga, made four attacks, sank transports Nichiro Maru (6,500 tons) 17 February, Uchide Maru (5,300 tons) 29 February.

Refit in Pearl Harbor, sortied for 11th patrol on 7 April to Kyūshū, Shikoku, Honshū. 26 April, torpedoed, sank Wazan Maru off Kii Suido, Osaka Bay. Back to Pearl on 26 May, sailed to west coast of overhaul at Mare Island, back in September 1944, 12th patrol (13 October) for the Bonin-Ryukyu Islands. Two trawlers damaged by deck gun and HMGs. Off Majuro Atoll 7 December 1944, assigned to training submarine crews until 13 January 1945, sent to Eniwetok Atoll, acted as target for ASW training and abck to Mare Island on 27 August. Hulk was sold for scrap 19 May 1947. She was awarded 8 battle stars.

USS Saury SS-189

USS Saury SS-189

USS Saury (SS-189) was laid down on 28 June 1937, launched on 20 August 1938 and completed on 3 April 1939. She had sea trials and qualifications off New London and sailed to Annapolis and New York City (late April) for the World’s Fair. In mid-May she had test dives, shakedown cruise which (26 June to 26 August) from Newfoundland to Venezuela, Panama Canal Zone and PSO (post-shakedown overhaul) at Portsmouth Navy Yard.

After final trials she sailed on 4 December for the West Coast and on 12 December, transited the Panama Canal for SubDiv 16, SubRon 6 in San Diego fior training until March 1940 and by April, Fleet Problem XXI off Hawaii. She sailed to Midway and back to the West Coast in September for overhaul at Mare Island. Until October 1941 she trained between Pearl Harbor and San Diego, California until sailing for Cavite, Philippines to join SubDiv 21, SubRon 2 from mid-November and a day after Pearl Harbopur attack, started her 1st patrol. She was off Vigan and on 21 December, she was ordered to Lingayen Gulf after a report from USS Stingray (SS-186). On 22 December, sighted an enemy destroyer, fired, no detonation. Countered attacks, evasive tactics in shallow waters, veered northwest and surfaced after dark in the gulf. She was sighted at 02:10 on 23 December, went to 120 feet (37 m), depth charged close. Escaped. Nex depht charging mid-day. 24 December missed a transport, too far. Evening another spotting, dove to 140 feet (43 m), escaped. 27–28 December made a crahe dive while charging batt. to avoid a destroyer division. 1 January 1942, sighted a convoy, unable to close range. 8 January ordered to proceed to the Netherlands East Indies via the Basilan Strait (11-12 January) and Davao-Tarakan line. 16 January, spotted the Tarakan lightship. 19 January entered at Balikpapan.

2nd sortie, patrolled off Cape William, Sulawesi and approaches to Balikpapan. 23 January 1942 moved to Koetai River Delta (Mahakam). 24 January was illuminated anf crash dived. Patrolled off Cape William and on 27 January sailed to Java. Arrived to Surabaya.

9 February she headed east for the Lesser Soendas. 13 February patrolled between Kabaena and Salajar (Sulawesi coast). Lombok Strait, night 19-20 February learned about the landing on Bali. 18 hours of submerged evasive tactics. 24 February sailed to Sepandjang Island, missed an enemy convoy.

From 26 February to 8 March patrolled from Meinderts Reef to Kangean Island (Madura Strait), leanred Surabaya fell and on 9 March proceeded to Fremantle (17 March). Reported Mark 14s issues.

3d patrol from 28 April 1942, but returned due to a crack in the after trim tank. 7 May, headed north. 14 May, patrolled off Timor. 16 May wa sin the Flores Sea, Banda Sea, eastern Sulawesi. 18 May attacked and missed a troopship off Wowoni. Patrolled Kendari, then Greyhound Strait, Molucca Passage. 23-24 May patrolled off Manado. 26 May, eastern Celebes Sea. 28 May sighted, fired on merchantman/seaplane carrier, missed. 8 June, returned to the Molucca Passage and off Kendari. 15 June, Boeton Passage, Flores Sea, and back to to Fremantle on 28 June.

2 July, sailed for Albany to test the Mark 14 torpedo. 23-25 July escorted the submarine tender Holland (AS-3) to Fremantle.

4th patrol, Lombok Strait 6 August 1942, Iloilo-Manila on 16 August, Ambulong Strait, Mangarin Bay. 18 August Mindoro Coast, Cape Calavite, Corregidor. 21 August sighted and attempted to close a tanker, missed. 24 August, closed Manila Bay. Sighted masts, heavy rain. 09:52, launched two torpedoes. 09:54 explosion heard, small tanker, 1st kill. 10:47 started to be Depth charged. Tried to surface and reload at 19:21, elusive tactics with more destroyers.

29 August poor weather, 31st, sighted, not attacked an hospital ship. 3 September headed south. 7 September was ordered off Makassar City. 11 September spotted 8,606-ton aircraft ferry Kanto Maru. 20:58 sent 3 torpedoes, heard explosion at 21:00, blew up 16 min. later. 17 September sailed for Exmouth Gulf and Fremantle 23 September.

She was under refit from 24 September to 18 October 1942. Left Brisbane on 31 October, 5th patrol over 27-day, western and northern New Britain, 27 contacts, developed four, fired 13 torpedoes, only single probable hit. Wask back at Pearl on 21 December, then Mare Island for overhaul, receiving a bathythermograph and new high periscope, back to Pearl 16 April 1943 and. 6th patrol from 7 May, East China Sea, northern Ryukyu, Kyūshū.

11 May took fuel and lubricating oil at Midway. 19-20 May passed a typhoon. Ordered off Amami Ōshima naval base, off Kagoshima (southern Kyūshū).

Patrolling to the west of the island, Saury sighted her first enemy maru soon after 09:00 on 26 May; but the ship was too distant to catch. About an hour later, Spotted a 5-ship convoy, fired 3 at 10:30, one exploded, then another (new spread), claimed 2,300-ton Kagi Maru. 10:34 depth charged, escaped. 28 May sighted steamer, moved to intercept, submerged 16:43 launched four at 17:24, hit once the 10,216-ton tanker Akatsuki Maru which dropped depth charges. USS Saury fired six more, 4 hits, she sank.

29 May spotted when surfaced smoke 14 miles (21 km) off, 19:13, submerged, tracking convoy of 4 cargo + 3 tankers. Surfaced and attacked at 20:58, claimed Takamisan Maru, 1,992 tons, Shoko Maru, 5,385 tons. 30 May back to Midway. 7 June, lost N°4 diesel. 13 June sailed to Pearl Harbor for repairs/refit.

13 July 1943 left Hawaii, 7th war patrol. 21 July, lost again her 4th diesel. Poor weather. Night 30 July between Iwo Jima and Okinawa, spotted contact by radar at 22:25, 2 large warships and a destroyer. On 31st, 03:03 submerged, 03:25, attacked but had troubles with depth control, targets passed. Was chased by a destroyer, escaped to the east. Surface later, discovered periscope shear bent 30° and other periscope + radars out of commission. She was back to Midway on 8 August, Pearl 12 August. Given enlarged conning tower, new periscope shears, new radar, engine overhauled.

8th-9th patrols, 4 October to 26 November 1943. 21 December 1943 to 14 February 1944, many sighting in the East China Sea but poor weather, no kill. When back while surfaced she was swamped by an oversized swell, hatches open. Electrical equipment shoerts, small fires, extinguished. Auxiliary power restored, arrived at Pearl on 21 February, the Mare Island for overhaul and re-engining. 16 June back to Pearl, 29th, started her 10th patrol.

5 July she had a cracked cylinder liner, back to Midway for repairs. 11 July same, but continued to San Bernardino Strait, entered 18 July. 6 August sighted an unescorted freighter. Spotted and attacked by aviation, broke off, sailed to Majuro on 23 August.

11th and last patrol (20 September to 29 November 1944) to Nansei Shoto until 4 November, rescuing a downed pilot. Sailed off Saipan 5-10 November, then antipatrol vessel sweep, Bonin Islands but poor weather. 18 November spotted, and attacked, damaged a tanker. Back to Pearl on 29 November.

Never sailed again. Became a target and TS. 19 August 1945 sailed to San Francisco for inactivation. She was given seven battle stars for her service. Saury was decommissioned on 22 June 1946, stricken on 19 July. She was sold for scrap 19 May 1947 to Learner in Oakland.

USS Spearfish SS-190

USS Spearfish SS-190

USS Spearfish (SS-190) was laid down on 9 September 1937, launched on 29 October 1938, completed on 12 July 1939. After sea trials off New London she had her shakedown cruise in the Guantanamo Bay area until 3 October, overhaul at Portsmouth from 1 November 1939 to 2 February 1940. On 10 February she sailed for the West Coast, San Diego from 6 March to 1 April, and Pearl Harbor.

On 23 October 1941 she departed for Manila, training from 8 November until the 8 December and started her first war patrol to the South China Sea, near Saigon and Cam Ranh Bay, then Tarakan-Balikpapan off Borneo. On 20 December she spotted a Japanese submarine, tried a submerged attack, fired four, missed. She ended on Surabaja on 29 January 1942.

2nd patrol from 7 February, Java Sea, Flores Sea, torpedo attacks on two cruiser but missed. On 2 March she was in Tjilatjap, taking on board 12 members of the staff, submarines command (Asiatic Fleet) for Australia, Fremantle.

Her 3rd war patrol was from 27 March to 20 May in the Sulu Sea and Lingayen Gulf. On 17 April, she sank a 4,000 tons cargo, and on 25 April, the 6,995-ton Toba Maru.

On the night of 3 May, she managed to sail into Manila Bay, picked up 14 nurses, several staff officers from Corregidor. Last American submarine to the fortress before it surrendered. From 26 June to 17 August she patrolled the South China Sea. From 8 September to 11 November, west coast of Luzon, damaged two freighters.

She returne to Brisbane and departed on 2 December 1942 for her 4th patrol off New Britain-New Ireland area. She then headed for Pearl Harbor on 25 January 1943, the Mare Island for a major overhaul until 19 May.

Back to Pearl Harbor on 26 May, she started her 7th war patrol on 5 June to the Truk Island area and gathered intel of Eniwetok Atoll, then Marcus Island. She was back at Midway for a refit between 1 August to 25 August and returned to Japanese home waters, south of Bungo Suido. Night of 10 and 11 September, she performed a submerged torpedo attack on a convoy (7 freighters), fired torpedoes, damaged two. Depthed charged for the rest of the day but eluded escorts. Night of 17-18 September, she attacked another convoy, sinking two, damaging one. She then headed to Pearl Harbor for refit.

From 7 November to 19 December she performed intel missions to Jaluit, Wotje, and Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands before the invasion. On 5-6 December she became lifeguard submarine during air strikes on Kwajalein and Wotje.

For her 10th war patrol she was south of Formosa from 17 January to 29 February 1944 and on 30 January, made two torpedo attacks on a convoy, sank an escort and the passenger-cargo Tomashima Maru. On 10 February another convoy, damaged a freighter and sank a transport and the day after, damaged another freighter. On 12 February, she damaged another freighter.

For her 11th war patrol from Pearl Harbor she headed for the East China Sea, north of Nansei Shoto. On 5 May she sank a freighter and the 6th the cargo Toyoura Maru. She was back to Pearl Harbor on 27 May, but sent to the West Coast for a major overhaul from 6 June to 3 October at Mare Island, then back Pearl Harbor on 10 October 1944 for training. She amde a Reconnaissance photo of Iwo Jima diring her last war patrol went from 12 November 1944 to 24 January 1945. She also made a survey of Minami Jima. Next she moved to the Nanpō Islands on lifeguard duties. On 28 November 1944 she was 23 nm (43 km; 26 mi) east-southeast of Iwo Jima when a B-24 Liberator bomber attacked her with rockets but hit the water 700 yards (640 m) from her as she submerged.

On 19 December 1944, she rescued 7 survivors from a ditched B-29. This was the first submarine rescue of downed B-29 airme.

On 11 January 1945, she gunned down a sampan, took three POW. After sailing back to Pearl Harbor on 24 January, she started to be used as local training sub until 18 August. On the 19the she sailed for the West Coast, arrived at Mare Island on 27 August. On 7 September she was inspected. It was decided it would be better of she can be decommissioned immediately and scrapped. But instead she was used for experimental explosive tests, cancelled, stricken 1946, and she was sold for BU to Lerner of Oakland, mothballed and scrapped in October 1947. She was awarded 10 battle stars.

USS Sculpin SS-191

USS Sculpin SS-191

USS Sculpin SS-191 was laid down at Portsmouth Navy Yard, Kittery, Maine on 7 September 1937, launched on 27 July 1938 and completed on 16 January 1939.

During her shakedown cruise on 23 May 1939, she searched for the missing USS Squalus after a test dive. She saw the red smoke bomb and rescue buoy and managed to establish communications by underwater telephone and by signals tapped in Morse on the hull. She stayed when Falcon rescued the survivors and helped the divers figuring out her sister ship as well as in the salvage. She then resumed training off the Atlantic coast and was transferred to the Pacific Fleet on 28 January 1940, via San Diego on 6 March. She was at Pearl Harbor on 9 March for 18 months. She left on 23 October 1941 for SubDiv 22 at Manila on 8 November, then Cavite until December 1941.

She started her first patrol on 8–9 December 1941 under command of Lucius H. Chappell, escorting USS Langley and Pecos to the San Bernardino Strait. She stationed off Lamon Bay, north of Luzon in four weather and replaced USS Seawolf off Aparri from 21 December. She spotted a task force coming ashore at Lamon Bay but was not in firing position. She sailed to Lamon Bay but due to the weather was unable to attack and she was back after 45 days to Surabaya on 22 January.

The second patrol lasted from 30 January to 28 February in the Molucca Sea and east of Sulawesi. On 4 February off Kendari (Java) she spotted and fired three torpedoes on Japanese destroyer and recorded two hits. IJN Suzukaze beached herself but was later salvaged. Later she spotted a task force bound for Makassar City and managed to fire on a cruiser but missed, was detected, depht charged for 4 hours, by six destroyers. She later reported the position. On 17 February, she was detected while surfaced for a night attack, firing two torpedoes at a freighter and a destroyer, missed, depth charged, damage to her starboard main controller and starboard shaft. She was back after 28 days at Fremantle for refit under repair, taking orders from Admiral Charles A. Lockwood.

Her third patrol was from 13 March-27 April in the Banda Sea and off Kendari. She was warned of the passage of CarDiv 5 on 24 March. But she failed to spot them, hiowever she saw and fired three torpedoes at a freighter, missed (ran deeper than set). The same happened on 1 April in a night attack and the third with the exact same. Her captain when back complained loudly about the Mark 14 torpedo which proved erratic with a Mark VI exploder never detonating. 45 unproductive days.

His 4th war patrol was from 29 May to 17 June in the South China Sea. On 8 June, unsuccessful cargo attack, again, torpedo malfunction. But she was depth charged anyway. On 13 June near Balabac Strait, she torpedoed a cargo ship while surfaced, but she returned fire with her deck gun. Sculpin then turned to the accompanying tankers astern, attack but was forced to dive as one attempted to ramm her. Surfacing at dusk the trailed the cargo ship, but was driven away by accurate gunfire, but she managed to hit the tanker, leaving her listing and smoking (no kill). Off Cape Varella (Indochina) on 19 June, she torpedoed a cargo (hit forward of the stack), secondary explosion, beached. She was back to Brisbane, under new Admiral Ralph Waldo Christie (Arthur S. Carpender’s 7th Fleet) with SubRon 2 in August.

Her 5th patrol was in the Bismarck Archipelago from 8 September to 26 October. She did some recce off Thilenius and Montagu harbors (New Ireland) and started to prey for shipping. On 28 September, 2 hits on a cargo but forced to dive (destroyer incoming), depth charged for three hours, minor damage. On 7 October she had at last her first confirmed kill: Naminoue Maru off New Ireland. A week later, she caught a three-ship convoy between Rabaul and Kavieng. She launched four torpedoes at Sumoyoshi Maru, confirmed sinking. Four days later by night she damaged, surfaced, the cruiser IJN Yura (hit forward of the bridge) but was driven off by gunfire. 54-day, 3 ships and 24,100 tons, but 6,652 tons later confirmed.

She left Brisbane for her 6th war patrol from 18 November 1942 to 8 January 1943, New Britain and Truk. Attempted attack, had to dive on 11 December. Codebreakers sent to meet a Japanese aircraft carrier, looked for her in the night of 17–18 December, 9 miles (14 km) but was illuminated by searchlight from escort, had to dive under fire. Depth charged/sonar search for hours, escaped. Next night, scored two hits on a tanker, no kill, for 52-day.

USS Sculpin then sailed to Pearl Harbor on 8 January 1943, then San Francisco for a major overhaul at Mare Island. Back to Pearl Harbor on 9 May, 7th war patrol on 24 May, northwest coast of Honshū. Midnight on 9 June off Sofu Gan, detected a Japanese task force (2 aircraft carriers, cruiser escort). She was outdistanced but launched four torpedoes from 7,000 yd (6,400 m), one exploded prematurely, had to flee but heard heavy underwater explosions. On 14 June, she damaged a cargo but was counter-attacked for hours. On 19 June, she destroyed two sampans by gunfire. She made more sightings but most hugged the shore. She went to Midway on 4 July after 41 days.

Her 8th war patrol was from 25 July–17 September off the Chinese coast, East China Sea, Formosa Strait. On 9 August, she sank Sekko Maru off Formosa. On 21 August, she intercepted an armed cargo, fired a spread, no explosion. Same pattern on 1 September, perfect course, two hits, no detonation. She patrolled of Marcus Island and returned to Midway Atoll after 54 days, credited a 4,500 tons cargo.

After a brief overhaul at Pearl Harbor under Fred Connaway she left on 5 November 1943 for the north of Truk, trying to catch intercepting force during the invasion of Tarawa as part of a wolf pack for coordinated attacks with Searaven and Apogon. Captain John P. Cromwell who knew in detail the Tarawa operation was on board to coordinate operations. She refuelled at Johnston Island on 7 November, and arrived on station. On 29 November, the wolf pack was activated but her mate never showed and after 72h was presumed lost (stricken on 25 March 1944). Her final patrol is told by surviving members, from the few surviving POWs liberated after V-J Day. On 16 November Sculpin had arrived on station, made radar contact with the convoy on 18 November, made a surface run until dawn on 19 November, in firing position but forced to dive as escorts zigged toward her. She surfaced doe an another run, but was spotted by Yamagumo 600 yards (550 m) away. She escaped the first depth charge pass. Second knocked out her depth gauge, she evaded in a rain squall but surfaced badly due to her damaged depth gauge, broaching and detected. She submerged but took 18 depth charges with considerable damage, she lost depth control, ran beyond safe depth (many leaks) and was easy for the Japanese sonar to follow. Second depth charge pass, she lost her sonar.

Commander Fred Connaway, decided to surface and give the crew a fighting chance. Still when surfaced, Sculpin’s gunners tried their best against the destroyer, but a shell destroyed the CT and killed the bridge watch, including the captain, and the gun crew. Surviving Lieutenant George E. Brown, ordered to abandon ship and prepared to scuttle her. He informed Captain Cromwell and the latter, fearing revealations under torture or drugs, went down with the boat and was posthumously awarded the MoH. Ensign W. M. Fiedler and ten others joined him down.

42 were picked up by Yamagumo. Survivors were questioned for ten days at Truk, embarked on two aircraft carriers to Japan. IJN Chūyō which carried 21 in her hold was torpedoed and sunk on 4 December by USS Sailfish. Just one survived, George Rocek. Ironically, Sailfish was the former Squalus she helped retreiving prewar. 21 were interned at Ōfuna Camp from 5 December and sent to work on the Ashio copper mines. Sculpin obtained 8 battle stars, the Philippine Presidential Unit Citation but only 3 confirmed kills for 9,835 tons. Again, the Mark 14 was flagged as a terribly inefficient weapon.

USS Squalus/Sailfish SS-192

USS Squalus/Sailfish SS-192

USS Squalus (SS-192) was laid down 18 October 1937, launched on 14 September 1938 and completed on 1 March 1939 with Lieutenant Oliver F. Naquin in command. On 12 May 1939 after a yard overhaul, she started test dives off Portsmouth, making 18, then another at the Isles of Shoals on 23 May. The main induction valve letting in fresh air surface failed and she started flooding the aft torpedo room, the the twoh engine rooms, crew’s quarters, drowning 26. The crew managed to seal other compartments and she still sank to the bottom under 243 ft (74 m) of water. As seen above she was spotted by Sculpin.

The two were able to communicate with a telephone marker buoy until the cable parted. Divers started rescue operations under the direction of the salvage and rescue expert Lieutenant Commander Charles B. “Swede” Momsen and this was the first use of the new McCann Rescue Chamber. The diverse supervised by a medical officers used heliox diving schedules and avoided cognitive impairment symptoms (nitrogen narcosis). The feat was that their managed to rescue all 33 survivors, 32 crew members and a civilian worker. Four enlisted divers were later awrded the MoH. Thuis became an international sensation, proving it was possible, especially back in UK with the loss of HMS Thetis in Liverpool Bay with all hands.

She was raised for study for checking the new construction, or determine alterations. Previous accidents in Sturgeon and Snapper urged indeed to to determine a cause to these losses. Rear Admiral Cyrus W. Cole (Portsmouth Naval Shipyard) and salvage officer Lieutenant Floyd A. Tusler from the Construction Corps managed to lift the submarine in three stages to prevent it from rising too quickly and possibly sink again. For 50 days, cables were passed and secured underneath to attach pontoons for buoyancy. On 13 July 1939, the stern was successfully but the bow remained stuck in the hard blue clay. She raised too quickly and suddenly, slipping her cables, broached with 30 feet (10 m) of the bow vertical for ten seconds and sank again to the bottom. Next was prepared a radically redesigned pontoon and cable arrangement and this second attempt was successful. She was towed into Portsmouth on 13 September, decommissioned on 15 November.

She was Renamed USS Sailfish to avoid th bad luck syndrom on 9 February 1940, first USN boat named for the sailfish. She was reconditioned, repaired and overhauled, then formally recommissioned on 15 May 1940 under command of Lieutenant Commander Morton C. Mumma Jr. She departed Portsmouth on 16 January 1941 for the Pacific via Panama, San Diego to refuel, Pearl Harbor (early March), and Manila. The previous boat’s bad luck curse was taken seriously and captain issued standing orders to never say the word “Squalus” ot be marooned at the next port call. Many crewmen deribly called her the “Squailfish”, until the threat of court martial also stopped it.

She departed Manila on her first war patrol, west coast of Luzon…

On 10 December, she sighted a landing force but was not in a good firing position. On the night of 13 December, she spotted two Japanese destroyers and attacked but she was detected, missed, was depth charged. She head a large explosion but no kill. She was back in Manila on 17 December. Her second patrol (under command of Richard G. Vogel) started on 21 December off Formosa. On 27 January 1942 off Halmahera (Davao) she spotted a Myōkō-class cruiser, she made a daylight submerged attack, launching four, reporting damage, and credited. Running under 260 ft (79 m) she managed to elude the destroyers and arrived at Java; then Tjilatjap on 14 February.

3rd patorls started on 19 February and she headed for the Lombok Strait to the Java Sea, spotting udnerway USS Houston and two escorts sailing for Sunda Strait after the defeat at the Battle of the Java Sea. She spotted an IJN destroyer on 2 March. Unsuccessful attack, dive deep. Next night near the mouth of Lombok Strait, she spotted what sghe thought to be IJN Kaga escorted by four destroyers. Fired four, scored two hits, leaving her aflame, dead in the water and she was depth charged for 90 minutes but eluded escorts and aircraft, camed back to Fremantle on 19 March. Her crew was saluted and greeted as the press reported this victory but in reality, she had sunk the 6,440-long-ton (6,540 t) IJA aircraft ferry Kamogawa Maru. Her 4th patorl sent her to the Java Sea and Celebes Sea from 22 March to 21 May. She deliver ammo to “MacArthur’s guerrillas” and returned to Fremantle.

Her 5th patrol was from 13 June to 1st August off the coast of Indochina and South China Sea. On 4 July she tracked a large freighter later identified as a hospital ship. However she spoted a Japanese freighter, sent two torpedoes she hit, she was left listing, heaed a series of explosions, credited the 7000 ton ship. In reality she had damaged the Japanese transport ship Aobasan Maru (8811 GRT), not sunk her.

Next she departed Brisbane under command of John R. “Dinty” Moore for her 6th patrol on 13 September to the western Solomon Islands. On 17–18 September, met eight Japanese destroyers escorting a cruiser, could not attack. On 19 September, she attacked a minelayer, three torpedoes which missed, had to dive deep, depth charged, minor damage. She was back on 1 November.

Her 7th patrol started on 24 November to New Britain. She attacked and missed a destroyer on 2 December, but no contacts until 25 December, then detected and torpedoed a Japanese submarine. Postwar analysis confirmed no sinking. She had one unsuccessful attack on a cargo and on a destroyer and returned to Pearl Harbor on 15 January 1943.

After an overhaul at Mare Island from 27 January to 22 April 1943 she was bac to Pearl Harbor on 30 April. She departed Hawaii on 17 May for her 8th patrol, refuelled at Midway and reached her station off east Honshū. Several contacts but bad weather prevented developments. On 15 June she spotted two freighters off Todo Saki with three subchasers. She fired three stern torpedoes, observed one hit but was driven down byescort, she was credit the Shinju Maru. Next she spotted a second convoy of three cargos with a subchaser and aircraft. She fired three stern tubes, sank Iburi Maru. But was massively depth charged over 10 hours (98 charges), light damage. She was back to Midway on 26 June, arrived on 3 July.

9th patrol (under William R. Lefavour) was from 25 July to 16 September 1943, Formosa Strait and Okinawa. Two contacts, no worthwhile targets, she sailed for to Pearl Harbor.

Her 10th patrol lasted from November 1943 to January 1944 after a refit at Pearl Harbor (Robert E. McC. Ward took command) and a partially newbie crew. She patrolled south of Honshū but lost a tube in a “hot run” aft. She refuelled at Midway and was directed by ULTRA to intercept a fast convoy before arriving on station. She made radar contact Southeast of Yokosuka on 3 December at 9,000 yd (8,200 m). This was the carrier IJN Chūyō, a cruiser, and two destroyers. She took firing position on 3–4 December and dived to radar depth to fire four bow torpedoes at the carrier from 2,100 yd (1,900 m), two hits. Depth charged, reloading, and at 02:00, surfaced and found many radar contacts but poor visibility. She fored 3 more from 3,100 yd (2,800 m), hearing two more hits on the carrier and eluded counter-attacks in raging seas. Went later to periscope depth to confirm at 07:58 the carrier preparing to abandon ship. In the morning she fired another spread of three from 1,700 yd (1,600 m), two last hits, loud internal explosions. She was narrowly missed by the prow of a ramming cruiser, went to 90 ft (27 m). Chūyō (20,000 long tons (20,321 t)) was confirmed, as the first aircraft carrier sunk by an American submarine. Chūyō howecer carried POWs from Sculpin (one survived) which saved her whe she was named Squalus. 1,250 went down with her as well.

On 7 December she was strafed by a fighter. Made contact and tracked two cargo ships and two escorts on 13 December south of Kyūshū. Fired four at the two freighters, two hits heard, internal secondary explosion. Totai Maru (3,000 GRT)borke and sank. Escaped the depth charged attack. Other freighter dead in the water, but covered by five destroyers. She left. On 20 December, she caught but left an enemy hospital ship.

On 21 December while close to Bungo Suido she intercepted six large freighters escorted by 3 destroyers. Five torpedoes sent, then 3 stern oned, two hits. Escaped the destroyers, detected breaking-up noises. Conformed sank Uyo Maru (6400 GRT). She was back to Pearl Harbor on 5 January 1944 to a hero’s welcome, 3 ships for 35,729 GRT, 7000 tons damaged, at this point she was believed to be the most successful by tonnage but postwar reduced to two ships and.

She had an extensive overhaul at Mare Island (15–17 June) and arrived at Pearl to resume activities on 9 July this time as part of a wolfpack, the “Moseley’s Maulers” (Stan Moseley), with USS Greenling and Billfish. They sailed for Luzon–Formosa. On 6 August, Sailfish and Greenling spotted an enemy convoy. Sailfish fired 3 torpedoes at a mine layer and a tanker, the later exploded and sank, but was not recorded postwar. She still sank the Kinshu Maru (238 GRT) in Luzon Strait. Next they spotted a battleship escorted by 3 destroyers, made radar contact on 18–19 August. At 01:35 she fired 4 bow tubes torpedes at 3,500 yd (3,200 m), hit a destoryer that saw the bubble and interposed herself, allegedly badly damaged but survived. The other missed.

On 24 August south of Formosa she spotted four cargo ships escorted by 2 small patrollers. Fire four torpedoes, scored two. Sank the Toan Maru (2100 GRT). Depth charged bu later trailed the second cargo, fired four, scored two, believed sanl bu no confirmed in JANAC postwar. She was back in Midway on 6 September.

Her 12th patrol was from 26 September to 11 December between Luzon and Formosa with USS Pomfret and Parche. Sge weathered a typhoon and was on station for lifeguard duty. On 12 October she rescued 12 navy fliers after fierce attacks on the airfields of Formosa. She sank a sampan and a patrol craft (deck gun). She landed her airmen at Saipan on 24 October, refuel, made repairs. She made an unsuccessful attack on a transport on 3 November. On the 4th, she damaged IJN Harukaze and the landing ship T-111 (890 tons) in Luzon Strait but was caught surfaced an near-missed, damaged by a bomb from a patrol aircraft. She rod out a typhoon on 9–10 November, intercepted a convoy on 24 November sailing to Itbayat, Philippines. USS Pomfret alerted of the convoy’s location and course and Sailfish moved in attack position. Caught by a destroyer, fired three-torpedo “down the throat”, one hit scored. Next came under fire by the same destroyer believed sunk. Ran deep and silent for amny hours, lost the convoy. She slipped away for Hawai, via Midway, arrived on 11 December. IJN Harukaze (which sank USS Shark) survived.

After refit in Mare Island, Sailfish was ordered to the east coast on 26 Decembe, New London, via Panama on 22 January 1945 and was kept for training out of New London until V-Day. She as a TS at Guantanamo Bay between 9 June and 9 August. After a refit at Philadelphia she was sent to Portsmouth for deactivation in October. She was decommissioned on 27 October 1945. Efforts by the city to keep her as a memorial failed. At least her conning tower was saved, dedicated in November 1946 on Armistice Day by the Under Secretary of the Navy. The rest was sold in March 1948, stricken on 30 April 1948 and BU in Philadelphi. The conning tower is now at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Kittery, Maine. She is a memorial to lost crewmen, and sports proudly her 9 battle stars.

USS Swordfish SS-193

USS Swordfish SS-193

Swordfish was laid down at Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo, California on 27 October 1937, launched on 4 January 1939 and completed on 22 July 1939.

⚠ Note: To be completed at a later date in an update

She won 8 battle stars for sher service but wa lost on or about 12 January 1945, presumed sunk by mine or depth charged.

USS Seadragon SS-194

USS Seadragon SS-194

USS Seadragon (SS-194) was laid down at Electric Boat, Groton, Connecticut on 18 April 1938, launched on 21 April 1939 and completed on 23 October 1939.

⚠ Note: To be completed at a later date in an update

She won 11 battle stars, had 10 Japanese ships certified for 43,450 tons. Sold for scrap 2 July 1948 to Luria Brothers, Philadelphia.

USS Sealion SS-195

USS Sealion SS-195

USS Sealion (SS-195) was laid down on 20 June 1938, launched on 25 May 1939 and completed on 27 November 1939.

⚠ Note: To be completed at a later date in an update

She was bombed by Japanese aircraft at Cavite Navy Yard 10 December 1941 and scuttled 25 December 1941. No battle stars.

USS Searaven SS-196

USS Searaven SS-196

Searaven was laid down at Portsmouth Navy Yard in Kittery, Maine on 9 August 1938, launched on 21 June 1939 and completed on 2 October 1939.

⚠ Note: To be completed at a later date in an update

She was decommissioned on 11 December 1946, sunk as a target on 11 September 1948, stricken 21 October 1948 with 10 battle stars for her service. She ended as target in Operation Crossroads Able test at Bikini Atoll 1946, survived, ended as target 11 September 1948.

USS Seawolf SS-197

USS Seawolf SS-197

Seawolf underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California on 7 March 1943. It was cold, note the white smoke coming from the diesels.

USS Seawolf was laid down on 27 September 1938, launched on 15 August 1939, completed on 1 December 1939 with Lt. Frederick B. Warder in command.

⚠ Note: To be completed at a later date in an update

Seawolf ranked 14th in confirmed tonnage sunk (71,609 tons) for the Sargo-class, 7th on top with USS Rasher (SS-269) and USS Trigger (SS-237) in confirmed kills according to postwar accounting (JANAC) and 14 batlle stars. She was sunk by “friendly fire” from the destroyer escort USS Richard M. Rowell on 3 October 1944.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign