International context

Prior to the 1898 war which saw an old European Empire crumbling when facing a young upstart, the world order was very much shaped by navies, reflecting the ambitions, aspirations or capabilities of their countries, often decades old. In 1890, old Europe was content maintaining the old status quo under the Victorian “Pax Britannica”: The Royal Navy ruled the seven seas, twice as large to any contender, and its old rival, the French Navy, rebuilding its strenght to contest the British on the globa sphere, with an unstoppable colonial drive. In 1890 also in Europe, Spain maintained perhaps the second largest navy after Italy, followed by a unified German Empire on the path of radical increase. The naval dominance of Europe however was now contested, on both sides of the hemisphere: In Asia, the Beyiang fleet was in full modernization and grew to the largest fleet in Asia, contested by Japan, another upstart that was gearing up towards a larger, modern fleet under guidance of the French. On te American continent, outside the rivalry between Brazil, Argentina and Chile, the United States was putting an end to its “old fleet” inherited from the cival war and starting to create a modern navy, under the guidance of Mahan.

Relations with Great Britain

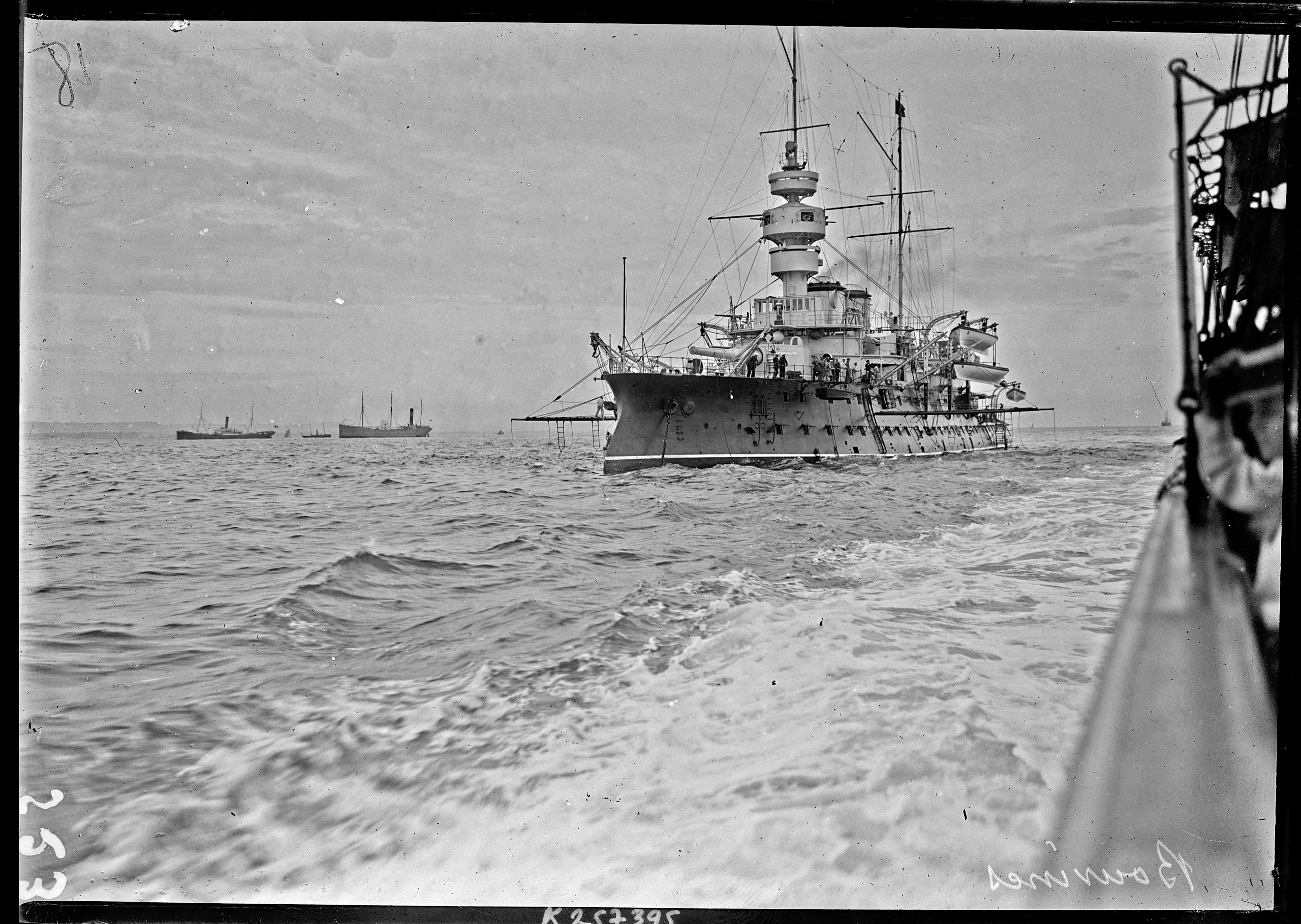

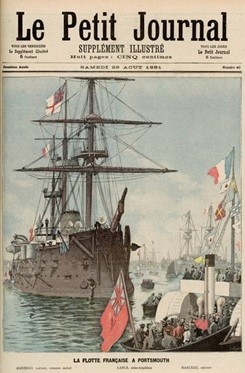

Bouvines present when a British squadron visited Brest in the late 1890s

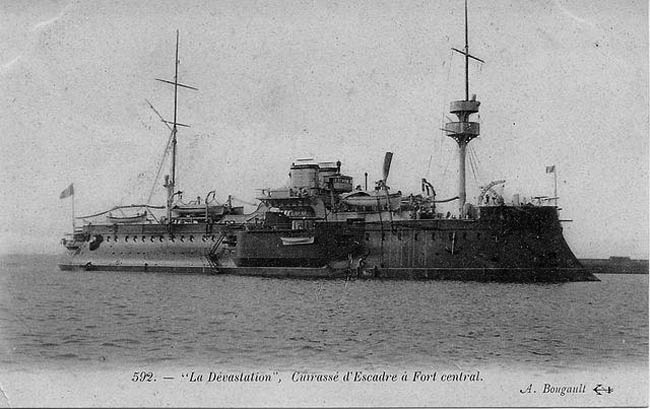

Relations with “perfid albion” (the nickname given to Great Britain by the French at the time) were neither cold not too hot; The internal bickering of the 3rd Republic seemed inocuous to Buckingham, less so than in the 1860-1870 with a Napoleon in power (the third). They however kept a watchful eye on developing alliances and bouts of French nationalism (like General Boulanger’s sudden popularity in 1886), as well as France’s unrelentless colonial drive, which would end with the Fachoda crisis in 1898. And of course its industrial development and military innovations, like the Devastation in 1879, world’s first all-steel and largest central battery ship even built.

Before 1890, there was no such thing as an “entente cordiale”, only occasional partneships with common interests like for the Crimean war. The defeat of 1870 was received with mixed feelings at 10, Downing Street. On one hand, a Napoleon was out again, and the old rival lost its power and prestige in continental Europe. On the other hand, this was counterbalance by a growing upstart from a former ally during the Napoleonic era, Prussia, now creating an Empire driven by industrial might and colonial ambitions, which changed the balance of power in Europe.

The traditional France-Russia-Austria troika found equilibrium, but this new Empire drawn to it all Germanophones of Europe, including the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and even a recently independent Italy. The new “central empires” axis was born. Naturally to this vertically-ordered axis, Great Britain found an alliance with France (after all, a buffer against Germany) preferrable, even though the latter choose the Russian Empire to counterbalance this axis to the east, relations of the latter with Great Britain in the 1880-90s decade remaining icy.

All these alliances, creating a cross throughout Europe, was like an ominous sign of the developments leading to WWI, with the Ottoman Empire’s disintegration in the equation. Despite some ease in 1891 with a famous goodwill visit (see below), in 1898, the “Fashoda Incident”, on the remote upper reaches of the White Nile, was an event close to provoke war between the two. In 1905, the Russian Navy sank by error a bunch of British trawlers while underway to the Mediterranean, and the pacific fleet. At the time, Imperial Russia was France’s objective ally to counterbalance the central empires, while the British Empire allied with Japan (before the war). A complex order which shifted again during the 1912 Balkan war and ended with the current 1914 alliances.

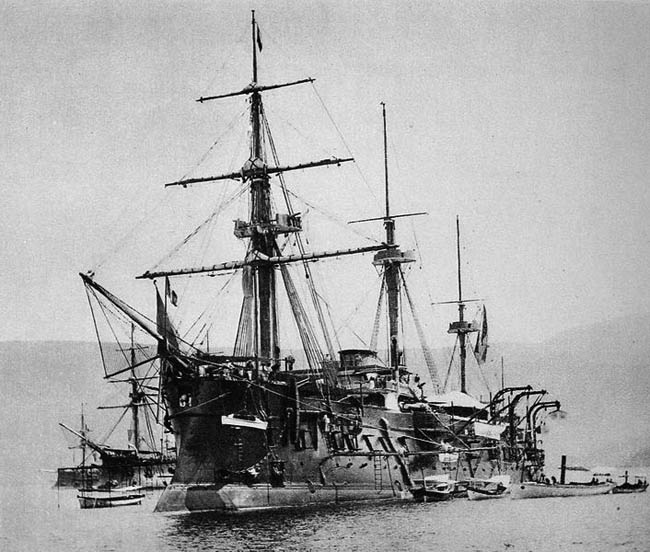

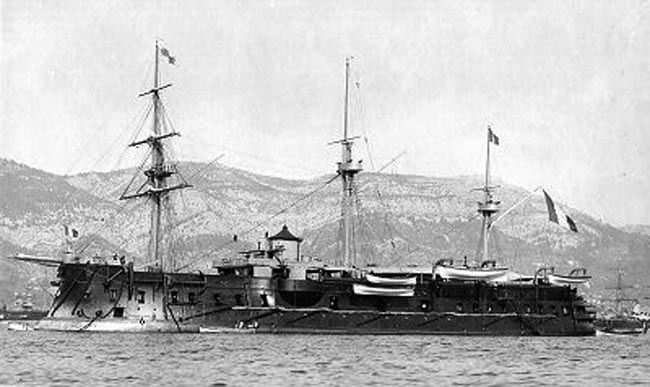

Colbert, photo by Neurdein

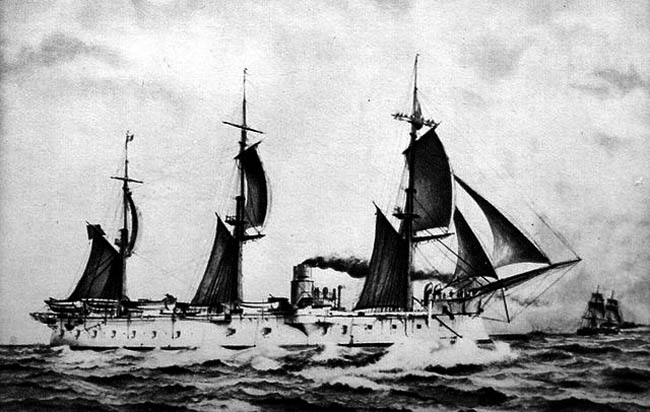

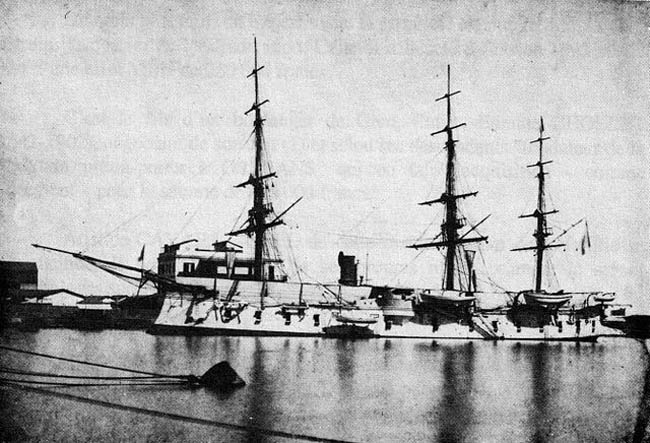

Ocean by F.Roux

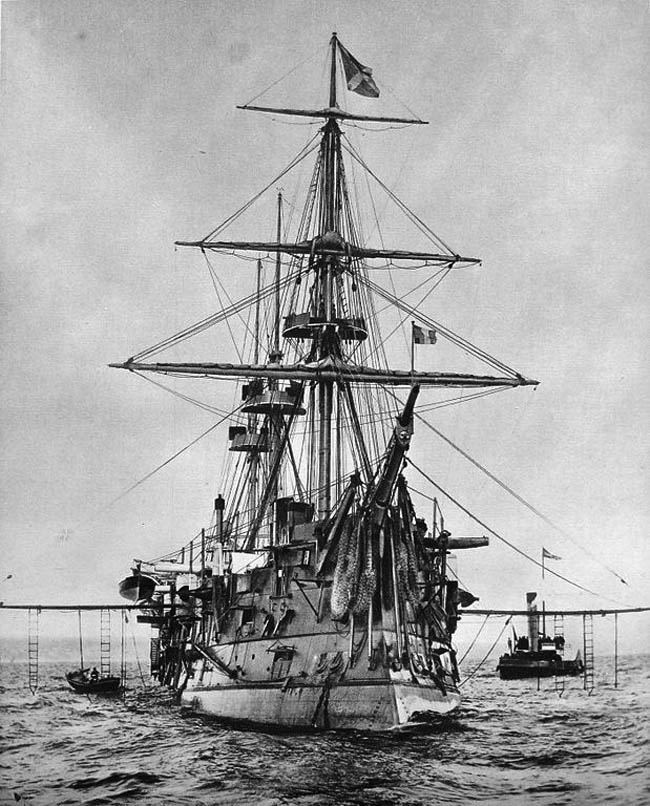

Ocean, by Neurdein

Coastal Battleship Valmy (color postcard)

The Marine Nationale in 1890

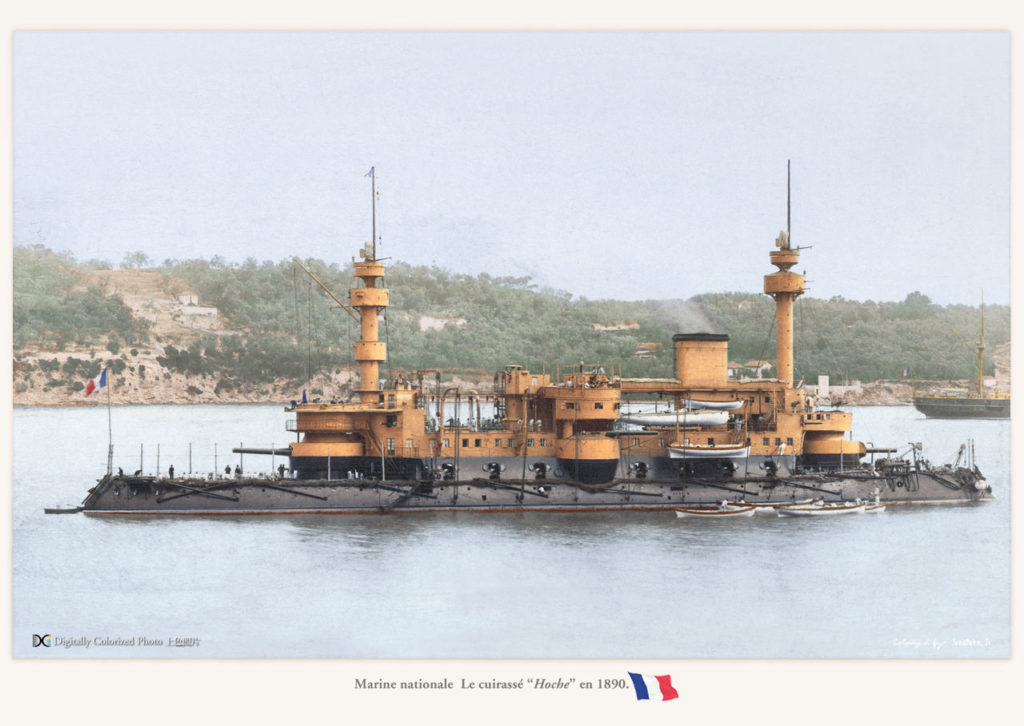

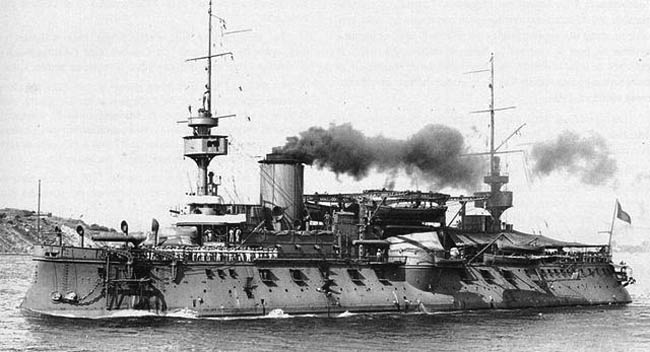

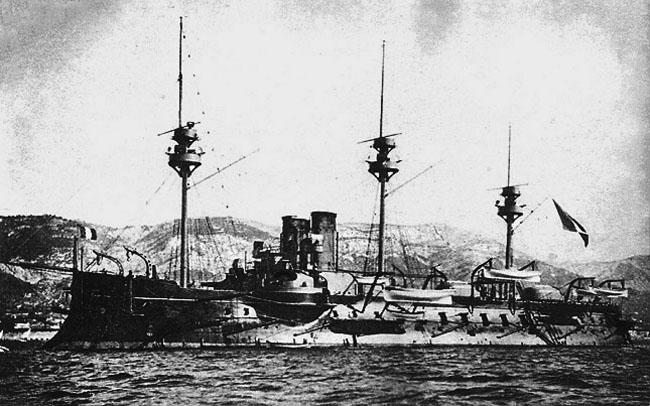

The strange battleship Hoche, perhaps one of the most typical product of the young school, built during the 1881-1890 decade.

Reeling from the 1870s defeat, France’s third Republic took a decade to modernize its largely untapped fleet, notably under the guise of a new fad that dominated its naval thinking: Theories of the “Jeune Ecole” (“young school”) – see later. This was an interesting decade, France transitioning to masted central battery ships to barbette ships, but already taking the path of experimentation, a large fleet of cruisers for home and colonial waters, a coast defence component, and sloops, gunboats and misc. ships in abundance. Like the Royal Navy, the Marine Nationale also kept its older hulls, basically all its old ironclads, most being wooden-hulled, were still in limited service as utility hulks and pontoons, as well as still many of its older steamships of the line.

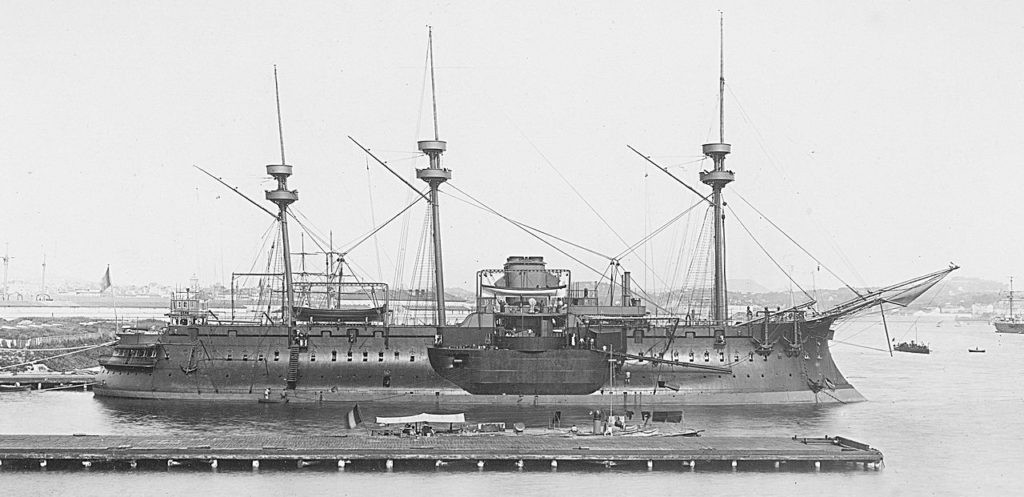

The Redoutable in 1889. One of the world’s Largest masted central battery ship, and first built in steel, when launched in 1879.

After the Napoleon in 1850, first steamship of the line, the Gloire in 1859, first sea-going ironclad, the 1863 Plongeur, first pneumatic-powered submarine, France’s engineers were still pushing the envelope and in 1875 was laid down a class of massive ships, the 10,450 tonnes central battery ships of the Devastation class, followed by armoured barbette ships, the ancestors of the turret battleships. Still, these ships were few in numbers and did not represented a numerical threat to the Royal Navy. Instead of competing on the same level, France, a continental country bound to keep a massive standing army driven by its revanchard spirit (revenge for the 1870 defeat), was obliged unlike Great Britain and its infinitely superior industrial output and finances, to divert large funds from the Navy to the Army.

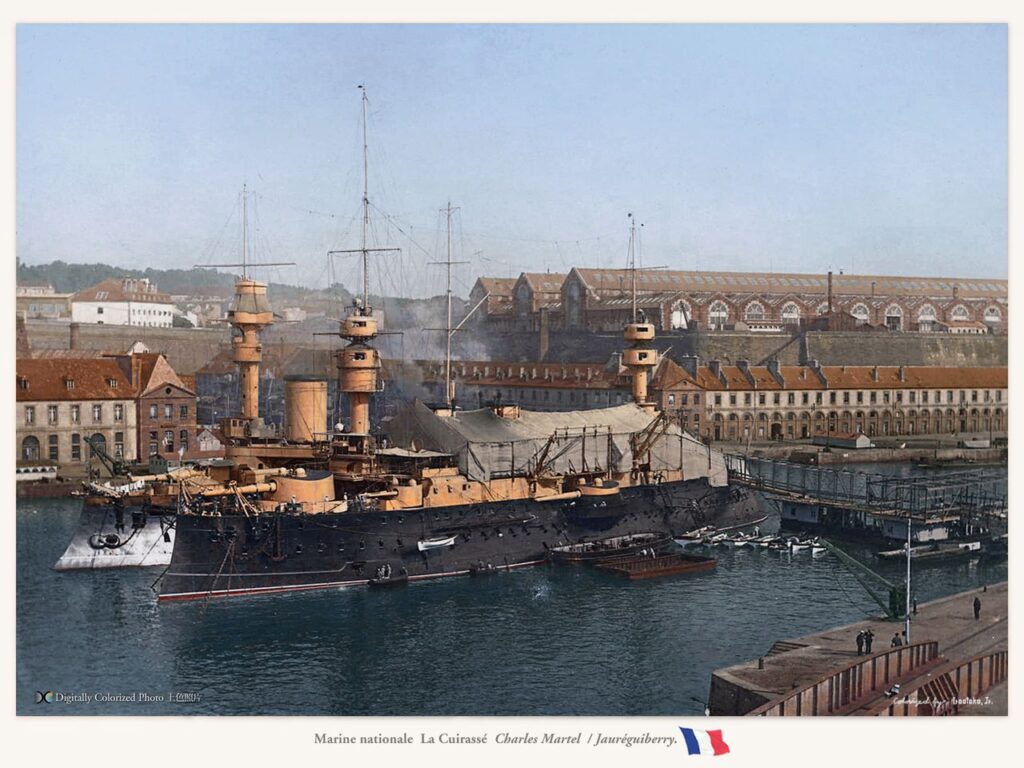

In the year 1890, France had five modern battleships in construction, most of which will not see WWI: Hoche (started 1881), the Marceau class (started 181-83), and Brennus (1889) the first of a new serie of pre-dreadnoughts that defined the French Navy in 1908. On the cruisers side, famous engineer Dupuy de Lôme innovated by proposing the Navy staff his 1887 design of a completely armoured commerce raider designed to prey on commerce (either British or German): Arguably the world’s first armoured cruiser, named after his inventor passed out. Many more were to follow, like the Amiral Charner class (all laid down 1889-1890). These were a complete departure of the old masted barbette and central battery ships of the 1870s-early 1880s still in service.

The revolutionary Dupuy de Lôme, first armoured cruiser (launched October 1890).

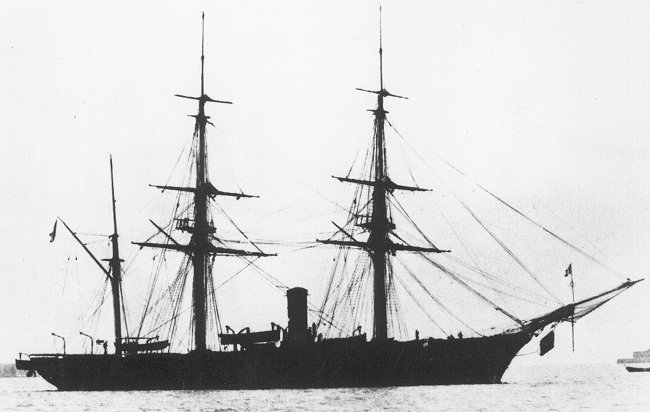

Alongside these, France also built “classic” protected or unprotected cruisers inherited from its 1860s frigates. France’s first protected cruiser was Sfax, launched 1884, and followed by single vessels: Amiral Cecille, Tage, Davout, Suchet, but also the Forbin, Troude and Alger class, all built in the 1880s for a total of 14 cruisers. The first were masted vessels, transitioning to heavy military mast ships in the 1890s. Alongside there was a considerable list of Colonial masted cruisers in service, the Talisman, Résolue, Decrès, Desaix and Limier class, Chateaurenault and Linois, Infernet, Sané, Bourayne and Rigault de Genouilly class, Hirondell and Duguay-Trouin, the large Duquesne and Tourville, Lapérouse and Villars classes, Iphigénie, Naiade, Aréthuse, Dubourdieu and Milan. These made for a total of 53 cruisers. More on these early French cruisers on the dedicated WWI French cruisers page. Milan was built quickly as a light scout, unlike capital ships between 1882 and 1885, but also she was the last French unprotected cruiser. From then on, France concentrated on Protected and later armoured cruisers. The Navy only went back to these light cruisers in 1912, planning a class of scouts that was eventually never constructed (to be continued).

Dupleix in China, 1886

Amiral Cecille

The Jeune Ecole

Theories of the “Young School” and influence over other navies across the world is considerable, albeit we cannot not easily name someone responsible the same way as Admiral Fisher or Alfred T. Mahan. This would be however Admiral Théophile Aube, without a doubt. Hyacinthe Laurent Théophile Aube (22 November 1826, Toulon, Var – 31 December 1890, Toulon) was a French admiral, which also took several important governmental positions in the 3rd Republi and served as Governor of Martinique (French West Indies) between 1879 and 1881 and crucially, became French Minister of Marine from January 7, 1886 to May 30, 1887. An ardent supporter of the Jeune École which he largely contributed to promote, he suspended construction of battleships when he was in charge.

Theories of the “Young School” and influence over other navies across the world is considerable, albeit we cannot not easily name someone responsible the same way as Admiral Fisher or Alfred T. Mahan. This would be however Admiral Théophile Aube, without a doubt. Hyacinthe Laurent Théophile Aube (22 November 1826, Toulon, Var – 31 December 1890, Toulon) was a French admiral, which also took several important governmental positions in the 3rd Republi and served as Governor of Martinique (French West Indies) between 1879 and 1881 and crucially, became French Minister of Marine from January 7, 1886 to May 30, 1887. An ardent supporter of the Jeune École which he largely contributed to promote, he suspended construction of battleships when he was in charge.

The intervention of the “Young School” would transform doubts about floating new theories linked to emerging naval technologies into certainty in many minds, and create for a long time an atmosphere of passionate discussions at least in France, way beyond the naval circles, with hot debates in the assembly about these questions as well. The group that named itself “the young school” included naval officers and publicists. The self-proclaim leader of it was, as said above, none eslse than was Admiral Aube, a distinguished sailor and maritime writer, helped in his preaching by a talented publicist, Mr. Gabriel Charmes.

Theories of the Young School could be summarized as follows:

The French Navy does not have the means to reach its objectives as its stands, because the goal of the country’s naval policy is poorly defined.

The common perception on a political sphere, was that the Navy reflected France and its prestige and it was duty to maintain its rank.

The Jeune Ecole argued this alone could ne be a rational goal and refuted at the same time the fatalism about always submitting to the “law of the strongest” (Britain being targeted).

All Naval operations must have two main and perfectly clear objectives:

1-First, to ensure the defense of the coastline against all odds

2-To do as much harm as possible to the adversary, whoever he may be.

Crucially, Aube argued there is no need for battleships to fill one or the other of these two essential goals.

He argued that armored squadrons no longer have mastery of the sea, because they lost it since the entry into line of “torpedo” and “speed”.

The fear of torpedoing encouraged these fleets to be cautious when facing the detterent of a large array of torpedo-carrying ships. Thus factor alone incapacitated operations against the opposing coasts, making it impossible to maintain a blockade. Slowness of these ships also does not allow them to choose their time and force them into battle. Battleships either can no longer effectively ensure protection of the coastline or communications. Ultimately, squadrons can only be used for a pitched battle and become powerless if the adversary only deployed fast ships capable of avoiding this battle and choosing piece-meale attacks and retreat at will.

The concentration of maximum power, both offensive and defensive into a single hull of a battleship, is moreover an error, challenging the principle of division of labor.

Aube and the school concludes that the battleships days are gone and it is necessary to replace squadron battleships by vessels possessing moderate speed and being multipurpose (read between lines, armoured cruisers), seconded by a large array of torpedo boats, gunboats, or tailored cruisers built for particular purposes and all having a speed enabling a safe outcome of any encounter with battleships.

Torpedo boats and gunboats must have as little displacement as possible and low silhouette to be stealthier, torpedo boats being especially entrusted to defend the coastline.

Gunboats could contribute, but above all, carry out shelling raids on the nearest enemy coasts, drawing its assets, that would be dealt for by an array of torpedo ships and mines.

The fast cruisers are tasked to attack communications lines fiest and foremost and cause the enemy’s soft belly, all possible harm, attacking its interests, goods and trade, waging a relentless “industrial war” and avoiding engagement with its fleet.

To effectively fulfill thes goals, the “new French Navy” was also to have numerous “support points”, carefully distributed and well defended.

A Navy constituted that way would be much better adapted true needs than the “old school battle fleet” and although less prestigious, being more coldly rational it would be both cheaper while being in the end, more formidable for the enemy. As taunted by Gabriel Charmes in support of this visions, for the price of a single battleship, the fleet can muster a fleet of 60 torpedo boats, the equivalent of several squadrons to defend an entire coastline…

Charles Martel and Jauréguiberry in Brest.

Overall, the impact of the “young school” was considerable. France having for more than two centuries the second best navy in rank and tonnage, was heard, despite the sorry state of the fleet after the radical changes in French defence policy following the defeat of 1870. Notably it was seen as a logical solution to make due with meagre budgets, not competing anymore in terms of raw battlefleet tonnage, but more of a constituted multi-ship “deterrence fleet”, made to defend and attack at the same time in an asymetric way. It is strange to consider the “second largest navy” was now professing a “guerilla style” navy, usually taken by naval underdogs and very small fleets.

The influence was considerable on Japan for example, reaching in the 1880s peak under Emile Bertin, which largely shaped the navy that fought the 1894 war with China, or Germany itself, which had growing imperial ambitions and looked at the Royal Navy as an impossible adversary to beat. Third, the Russian Navy was alsoi heavily influenced, in more aspects that one, notably by constituting one of the largest torpedo boat force at the time, plus betting on mine warfare.

However the Jeune Ecole was not such as good proposition for France on the long run, as the Marine Nationale was ill-prepared to fill its tasks in the entente during the first world war. In this war, its fleets of torpedo boats were of no use, its battleships were too diverse (while being both obsolete and costly) to be gathered into homogeneous formations, it’s armoured cruisers being perhaps its greatest asset, but again, gaving nothing really to do as German trade was minimal. In the end overall in 1917 France lacked ships that could actually make a difference against the new threat of the age, submarines…

Articles to cover (In service by 1890 and/or discarded before 1914)

Battleships

Friedland Central Battery ship (1873)

Richelieu Central Battery ship (1873)

Colbert class Central Battery ships (1875)

Redoutable Central Battery ship (1876)

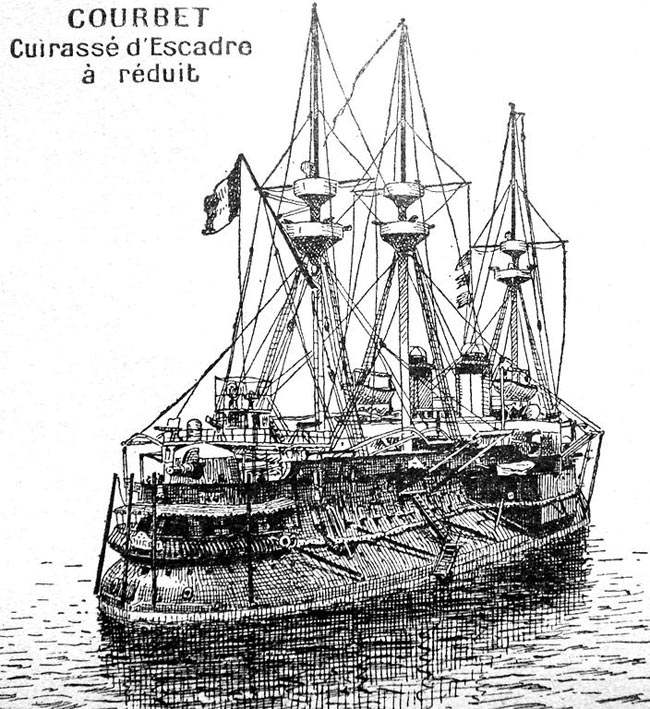

Courbet class Central Battery ships (1879)

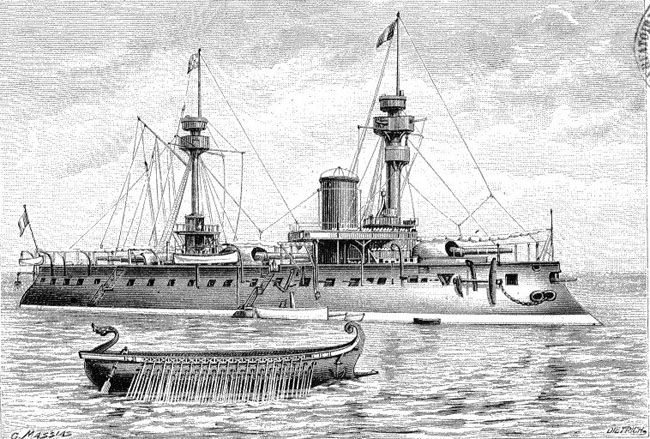

Amiral Duperre barbette ship (1879)

Terrible class barbette ships (1883)

Amiral Baudin class barbette ships (1883)

Barbette ship Hoche (1886)

Marceau class barbette ships (1888)

Coast Defence Ships

Cerbere class armoured ram (1870)

Tonnerre class Breastwork Monitors (1875)

Tempete class Breastwork Monitors (1876)

Tonnant Barbette ship (1880)

Furieux Barbette ship (1883)

Fusee class Armoured Gunboats (1885)

Acheron class Armoured Gunboats (1885)

Jemmapes class Coastal Defense ships (1892)

Bouvines class Coastal Defense ships (1892)

Protected Cruisers

La Galissonnière Cent. Bat. Ironclads (1872)

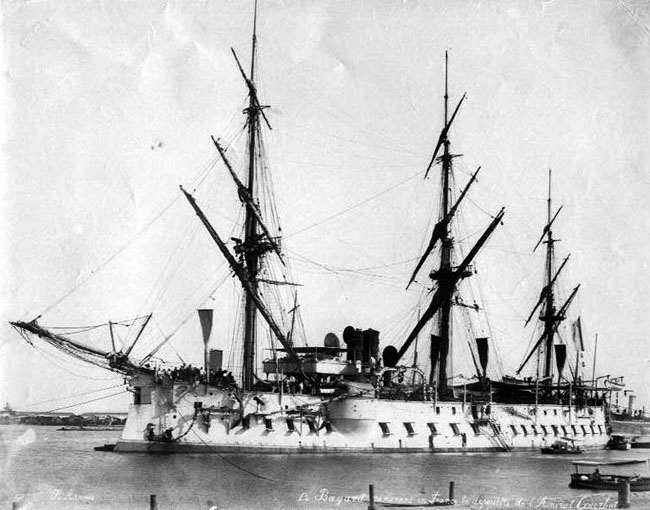

Bayard class barbette ships (1879)

Vauban class barbette ships (1882)

Prot. Cruiser Sfax (1884)

Prot. Cruiser Tage (1886)

Prot. Cruiser Amiral Cécille (1888)

Prot. Cruiser Davout (1889)

Forbin class Cruisers (1888)

Troude class Cruisers (1888)

Alger class Cruisers (1891)

Friant class Cruisers (1893)

Prot. Cruiser Suchet (1893)

Descartes class Cruisers (1893)

Linois class Cruisers (1896)

D’Assas class Cruisers (1896)

Catinat class Cruisers (1896)

Light Cruisers

R. de Genouilly class Cruisers (1876)

Cruiser Duquesne (1876)

Cruiser Tourville (1876)

Cruiser Duguay-Trouin (1877)

Laperouse class Cruisers (1877)

Villars class Cruisers (1879)

Cruiser Iphigenie (1881)

Cruiser Naiade (1881)

Cruiser Arethuse (1882)

Cruiser Dubourdieu (1884)

Cruiser Milan (1884)

Sloops, Gunboats and Misc.

Parseval class sloops (1876)

Bisson class sloops (1874)

Epee class gunboats (1873)

Crocodile class gunboats (1874)

Tromblon class gunboats (1875)

Condor class Torpedo Cruisers (1885)

G. Charmes class gunboats (1886)

Inconstant class sloops (1887)

Bombe class Torpedo Cruisers (1887)

Wattignies class Torpedo Cruisers (1891)

Levrier class Torpedo Cruisers (1891)

The Young School

(More to come)

1891 Goodwill visit to Britain

There were rare, intermittent and usually short times in the 900 years-long tumultous relations between Britain and France and just 40 years after the fall of Napoleon in 1815 (a generation) Britain and France (with Piedmont) intervened to save Turkey from the Russians in the Crimean War in 1854-56, with mutual suspicions relaxed. Until 1890, Buckingham still saw France a first rate threat, with Russia a close second. Coastal fortifications in addition of the Navy were constantly bolstered and a naval arms race ongoing since 1860. In 1891, there was however a surprising gesture of good will:

There were rare, intermittent and usually short times in the 900 years-long tumultous relations between Britain and France and just 40 years after the fall of Napoleon in 1815 (a generation) Britain and France (with Piedmont) intervened to save Turkey from the Russians in the Crimean War in 1854-56, with mutual suspicions relaxed. Until 1890, Buckingham still saw France a first rate threat, with Russia a close second. Coastal fortifications in addition of the Navy were constantly bolstered and a naval arms race ongoing since 1860. In 1891, there was however a surprising gesture of good will:

In this period of lowered tension, a French Naval squadron was sent by order of the government (President Sadi Carnot, PM Charles de Freycinet, both moderate anglophiles) to make a marking goodwill visit to Britain, at times it was rare. This was an event of first magnitude at the time, a novelty marked by a reiew given by Queen Victoria herself. This event was in some way identical to the 1858 similar Britsh visit to France in the aftermath of the Crimean War. In 1959, France launched an arms race and relationed became icy again. Paintings and illustrations showed just how spectacularly naval technology advanced during these 30 years.

This 1891 French visit to Britain trigerred a massive interest, especially as it was in the great anchorage of Spithead, facing Portsmouth, at the time, the main Royal Navy base, surrounded by massive fortifications in the 1860-70s. This arrival in Portsmouth in August 1891 saw Marengo (an obsolete wooden ironclad) leading the French line with, Requin and Marceau and Surcouf on the wing. The Illustrated London News depicted a grand event and the French squadron was flanked by the most modern British battleships of the time, like the HMS Camperdown, later famously rammed HMS Victoria in the Mediterranean in an infamous incident.

The Requin was one of the latest French coast defence ironclad, but the jewel ws rather the brand new Marceau of 1887.

Officers and specialists from both sides happily visited each others’ ships and gauge respective technology and organisations. The Spectator magazine (22nd August 1891) commented in detail about the French mounting of heavy guns compared to British barbettes and personnel/officers differences, like the comparatively larger crews. With French embarrassment, the cruiser Surcouf ran aground and was assisted by British seamen and marines. It was still equipped with a capstan rather than a steam winch, whereas new French designs already made the swap, and long before in the RN.

The “Spectator” newspaper admitted the French engine-room crews seemed to show a marked superiority in education and intelligence compared to british stokers and assistants and the officers are educated gentlemen ‘brimful of the latest theories of naval war and practice and, exceedingly competent in the practical management of their ships’. This was demonstrated by a show of squadron manoeuvers in Portsmouth.

But the visit highpoint was of course the official visit by Queen Victoria. A complete contrast with the fleet she visited at Cherbourg in 1858. In 1891 the younger officers present, both British and French, would learn that the rapprochement ten years latter (despite Fachoda) would lead to the entente cordiale, and agreements between the fleet against the central empires prior to 1914 to who was in charge of the Mediterranean and the north sea/atlantic coast. Both Navies fought as allies in WWI and WWII as well, despite the sad episode of Mers-el-Kebir that soured relations with the Vichy Government (to which the Navy, Army and Air Force obeyed) until late 1942 and Darlan’s swap.

Read More/Src

https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2019/10/28/french-navy-1870s-to-1904-part-i/

https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2019/10/28/french-navy-1870s-to-1904-part-ii/

https://alexcolorsstudio.home.blog/ many colorized 19th cent. French warships

https://www.avions-bateaux.com/uploads/attachment/produit//produit_3625_46384731f590702da7b2e857d3baab72.pdf

French ironclads

Friedland Central Battery ironclad (1873)

Richelieu Central Battery ironclad (1873)

Colbert class Central Battery ironclads (1875)

Redoutable Central Battery ironclads (1876)

Courbet class Central Battery ironclads (1879)

Amiral Duperre barbette ironclad (1879)

Terrible class barbette ironclads (1883)

Amiral Baudin class barbette ironclads (1883)

Marceau class barbette ironclads (1888)

French Coastal armoured ships

Cerbere class armoured ram (1870)

Tonnerre class Breastwork Monitors (1875)

Tempete class Breastwork Monitors (1876)

Tonnant Barbette ship (1880)

Furieux Barbette ship (1883)

Fusee class Armoured Gunboats (1885)

Acheron class Armoured Gunboats (1885)

Jemmapes class Coastal Defense ships (1892)

Bouvines class Coastal Defense ships (1892)

French Protected Cruisers

La Galissonière Cent. Bat. Ironclads (1872)

The La Galissonnière class were a group of central battery ironclad warships built for the French Navy, started before the Franco-Prussian War and heavily modified postwar. They were designed as part of France’s continued naval expansion and modernization during the ironclad era. The class comprises La Galissonnière (launched 1872), Victorieuse (launched 1875) and Triomphante (launched 1877). They were improved versions of earlier Armide class, incorporating lessons from the Franco-Prussian War, and emphasized balanced armor, firepower and sea-keeping. They were mostly designed for overseas territories of the French Empire, basically a cheaper substitute to regular ironclads such as those of the Atlantic and Mediterranean Squadrons. They were smaller than average 1st rank ironclads at 4,600/4,800 tons, had a single steam engine and propeller for 13 knots, four 240 mm guns in central battery and a 150-120 mm wrought armour while being barque-rigged for long travels. They served until 1893-94 in the Pacific, Caribbean and Levant (Middle East), and were sold for BU in 1900-1903.

Bayard class barbette ships (1879)

Vauban class barbette ships (1882)

Prot. Cruiser Sfax (1884)

Prot. Cruiser Tage (1886)

Prot. Cruiser Amiral Cécille (1888)

Prot. Cruiser Davout (1889)

Forbin class Cruisers (1888)

Troude class Cruisers (1888)

Alger class Cruisers (1891)

Friant class Cruisers (1893)

Prot. Cruiser Suchet (1893)

Descartes class Cruisers (1893)

Linois class Cruisers (1896)

D’Assas class Cruisers (1896)

Catinat class Cruisers (1896)

French Unarmored Cruisers

R. de Genouilly class Cruisers (1876)

Cruiser Duquesne (1876)

Cruiser Tourville (1876)

Cruiser Duguay-Trouin (1877)

Laperouse class Cruisers (1877)

Villars class Cruisers (1879)

Cruiser Iphigenie (1881)

Cruiser Naiade (1881)

Cruiser Arethuse (1882)

Cruiser Dubourdieu (1884)

Cruiser Milan (1884)

French small ships

Parseval class sloops (1876)

Bisson class sloops (1874)

Epee class gunboats (1873)

Crocodile class gunboats (1874)

Tromblon class gunboats (1875)

Condor class Torpedo Cruisers (1885)

G. Charmes class gunboats (1886)

Inconstant class sloops (1887)

Bombe class Torpedo Cruisers (1887)

Wattignies class Torpedo Cruisers (1891)

Levrier class Torpedo Cruisers (1891)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign