The Ibuki class (伊吹型) or Kurama class (鞍馬型) were transitional “semi-battlecruisers” classed as armoured cruisers (Sōkō jun’yōkan) of Imperial Japanese Navy, with a powerful secondary armament leaning towards monocaliber.

https://bit.ly/3XjuGhD

Delays had them completed only in 1909-1911, and they were obsolete. An interesting design nonetheless, they served in WWI, trying to catch Von Spee’s Asian squadron and covering missions to seize the German Carolines and Mariana Islands, or escorting convoys to the Indian Ocean. In 1922, the Washington treaty was signed and they were disarmed and latter scrapped. #IJN #WWI #ibuki #kurama #armouredcruisers #imperialjapanenavy

Origins and context

After the Russo-Japanese War, many lessons had been digested around the world on naval combat. This was arguably the most influential battle of “modern” battleships so far, prior to Jutland ten years afterwards, generated a lot of theories about how combat between capital ships should be done. The Ibuki class ships reflected Japanese experience from that war, designed to fight side-by-side with battleships and were given an armament almost as superior to Japanese battleships of the time. The key of this design was a very powerful secondary battery, making them for most author’s “battlecruisers” yet, they were still armoured cruisers, of the very last generation, their best equivalents would be the German SMS Blücher, with had lower caliber guns, but on a monocaliber fashion. However by the time they were completed, HMS Dreadnought had been built, and with her sister ship IJN Kurama she was obsolete even before completion in 1909 and 1911, British proper battlecruisers were much more heavily armed, and faster. In 1910 already was launched HMS Lion, which was way superior, and trigerred an order for the Kongo class, studied from 1911.

Both ships “battlecruisers” had a short carrer in World War I, hunting Von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron without success and searched for the commerce-raider SMS Emden, al well as protected troop convoys in the Pacific Ocean in 1914. They were both were sold for scrap in 1923 due to the Washington Naval Treaty.

Design Development

The Ibuki-class ships originally had been ordered during the Russo-Japanese War, on 31 January 1905. They were to be supplementary Tsukuba-class armored cruisers. However they were redesigned to incorporate 8-inch (203 mm) guns rather than the twelve 6-inch guns initially planned. Engineers thus had to rework their hull entirely, which became larger to fit the new, large side turrets and required also more output, adding extra boilers to keep the same speed.

Protection was well cared for, more even that for the Tsukuba class since they needed to be superior to all armored cruisers and and to take part in a battleline, along with regular battleships and drew much from the two Kasuga-class armored cruisers, drawiong inspiration from the Battles of the Yellow Sea and Tsushima. Of course, the appearance of the British Invincible class as they were just started, having eight 12-inch guns for 25 knots, cause concerns to the admiralty, which proceeded anyway.

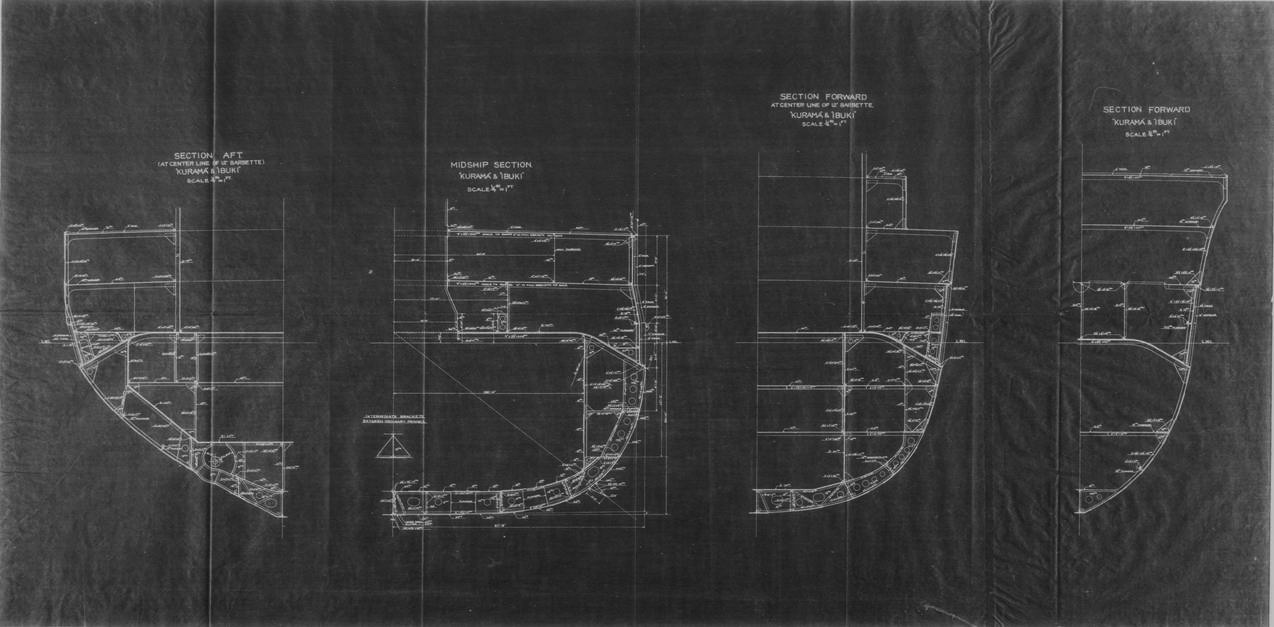

Design of the Ibuki class cruisers

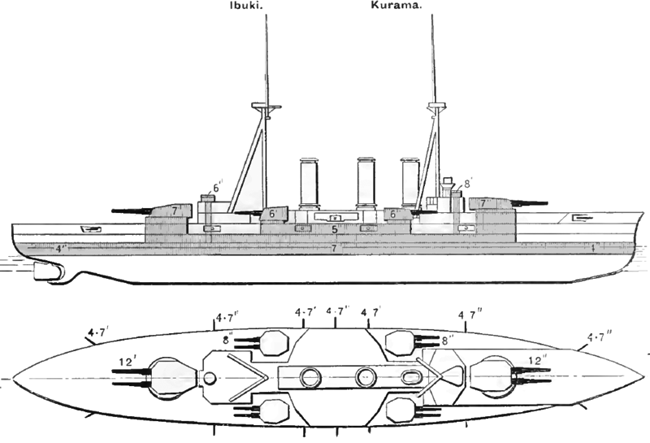

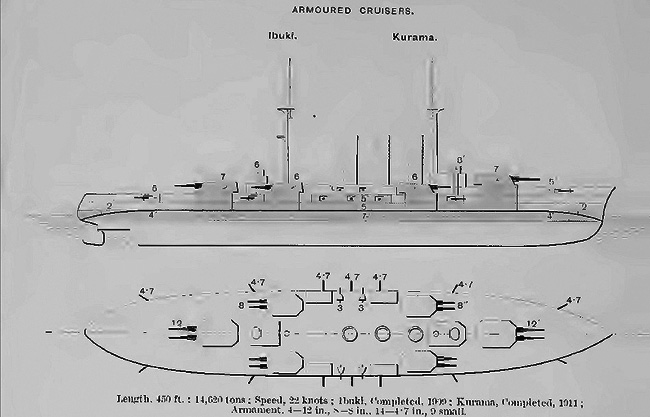

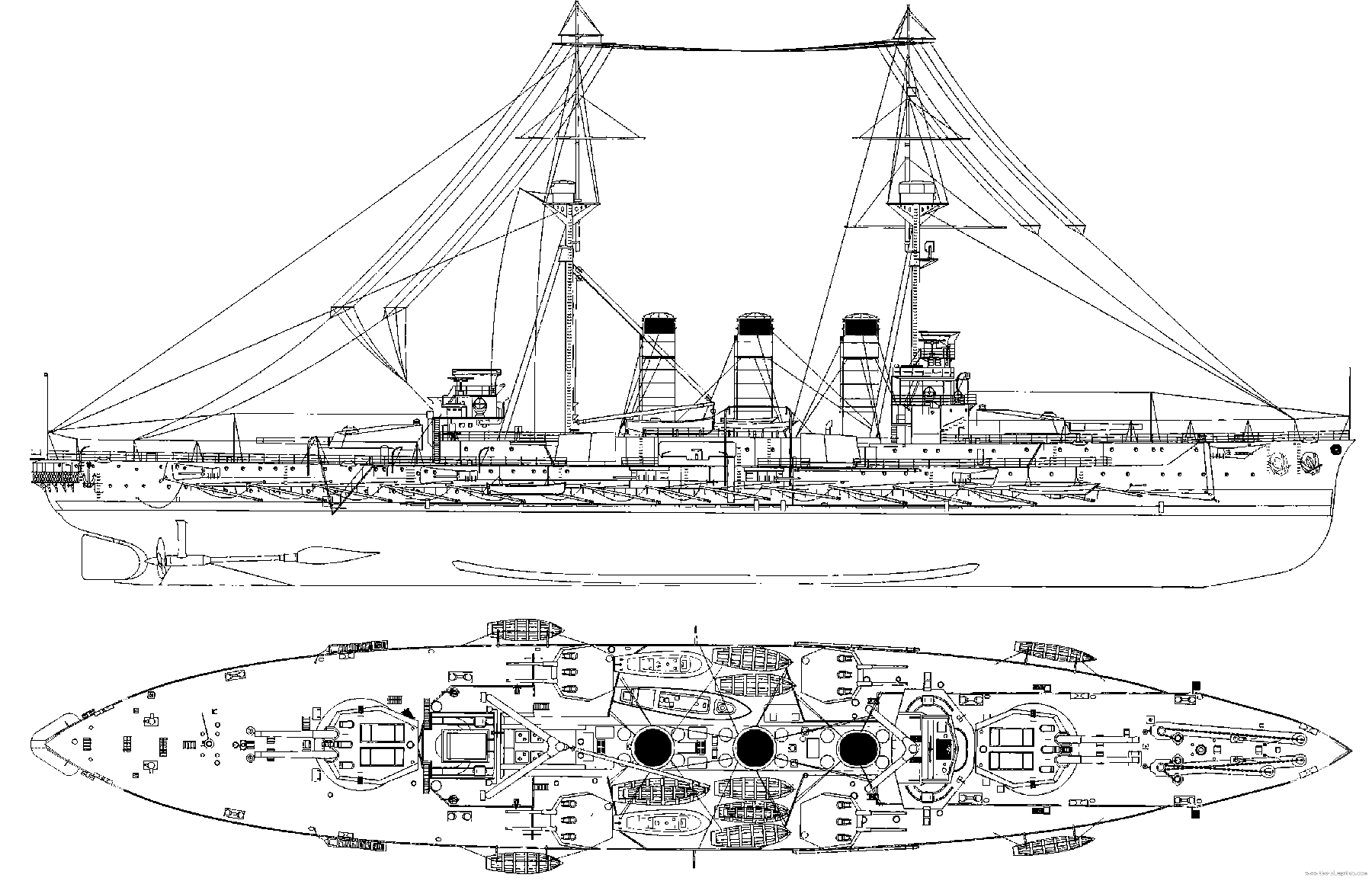

The Ibuki class were 485 feet (147.8 m) long (between perpendiculars 450 feet or 137.2 m) for 75 feet 6 inches (23.0 m) in width and 26 feet 1 inch (8.0 m) in draft. This for a displacement in line with the last generation armoured cruisers, about 14,636 long tons (14,871 t), normal, 15,595 long tons (15,845 t) fully loaded. This was 900 tons more than the Tsukuba class. Metacentric height was 2 feet 11.5 inches (0.902 m). The crew amounted to 845 officers and ratings.

Compared to the Tsukuba class, they were longer, larger, but proceeded from the same general design, with a forecastle given recesses for the broadside forward turrets, and a lower deck, a tall bridge, two mast, taller this time and tripod, and three equal size and span funnels instead of two. Conways classed both the Ibuki and Tsukuba classes as “battlecruisers” given their role (this is literraly their intended role), not based on armament consideration. In comparative sense, only the Kongo class were the first true IJN “battlecruisers”. On the other hand, the Blücher, despite having a more homogeneous, monocaliber armament, was still considered an “armoured cruiser”, because she was not intended to take part in battles but to hunt down cruisers.

Protection

Armor of the Ibuki class was improved compared to the Tsukuba class. She used for the most important parts, comprising the belt, Krupp cemented (KC) armour.

Main belt amidship: 7 inches (178 mm) along the citadel (between barbettes).

For and aft Belt: 4 inches (102 mm) beyonf the citadel.

Upper belt strake: 5-inch (127 mm) only betwen the 8-in barbettes.

Secondary turrets semi-bulkheads 6 inches (152 mm) thick.

Transverse bulkheads: 1-inch (25 mm) thick

12-in gun turrets: faces and sides 9 in (229 mm), roof 1.5-in (38 mm).

Main barbettes: 7 inches

8-inch turrets: 6 inches frontal arc.

Secondary barbettes: 5 inches, 2 in (51 mm) below the armor belt.

Main & secondary armored decks: 2 inches.

Forward conning tower: 8 inches, communications tube 7 inches.

Propulsion

Both battlecruisers had the same vertical triple-expansion (VTE) steam engines as the Tsukuba class, but the delayed Ibuki allowed her to serve as a test-bed to install steam turbines. Four sets of Curtis turbines purchased from Fore River Shipbuilding Co. in the US were in the end procured to equip both IJN Ibuki and the battleship IJN Aki. Later $100,000 were paid to buy a manufacturing license, to be manufactured by Gihon. However the first ships planned to received these were the never completed Amagi class battlecruisers (But IJN Akagi had those).

IJN Ibuki thus diverged from Kurama by having a superior total output of 24,000 shp (18,000 kW), allowing her to reach 21.5 kts, wheras Kurama had two shaft VTE for 22,500 shp (16,800 kW), reaching 20.5 kts. However both had 28 Miyahara water-tube boilers, to compare with the 20 of the Tsukuba class, which “only” reached 22,500 shp for 21.25 kts.

These boilers comprised 18 mixed-firing ones with superheating of the Miyabara water-tube type, with a working pressure of 17 kg/cm2 (1,667 kPa; 242 psi). They used fuel oil sprayers on coal to boost burn rate. But still, they were considered bad steamers: For Ibuki on sea trials, 12 August 1909, she only reached 20.87 knots (38.65 km/h; 24.02 mph) based on 27,353 shp (20,397 kW). The turbines were modified, propellers changed but for only “scratching” a fraction of knot. New trials on 23 June 1910 had her reaching 21.16 knots (39.19 km/h; 24.35 mph), based on 28,977 shp (21,608 kW), just enough to be accepted, but still below expectation.

IJN Kurama with her old style four-cylinder reciprocating steam engines and same boiler with four more for 28 total, and an additional funnel, seemingly reeached the desired speed figures on trials. Both carried 1868 and 2,000 long tons of coal plus 215 (200 and 218 long tons respectively) long tons of fuel oil for the sprayers. No range figure was given, like for the Tsukuba class.

Armament

Main Battery

The Ibuki-class were armed with four 45-caliber 12-inch 41st Year Type guns as main armament. They were mounted in twin, hydraulically powered turrets. These mounted elevated to −3°/+23° and could load at an angle of +5°, and up to +13° in thoery, although problematic due to the shell weight. They fired a 850-pound (386 kg) armour-piercing shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,800 ft/s or 850 m/s, enabling a max range of 24,000 yd (22,000 m) although like in the RN and considered past experiences at Tsushima, a 18,000 yds was preferred.

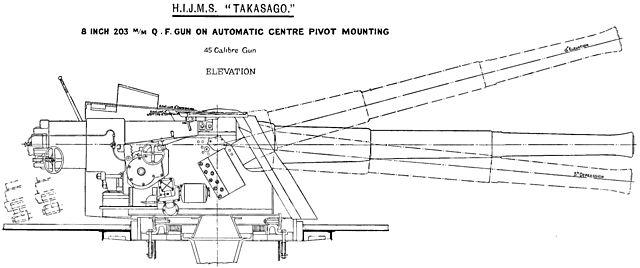

Secondary Battery

The intermediate armament was the earl game changer of the design and why she leaned more towards a “battlecruiser” unlike her predecessor: She boasted four twin-gun turrets, all alongside the central superstructure with large cutouts and sponsons to enable a 250° traverse. They had a 45-calibre 8-inch 41st Year Type gun, derived from Vickers models built under licence in Japan. They actually could fire as far as the main guns thanks to a 30° elevation, givin them the near-same range of around 23,000 yards (21,000 m), and they were faster. Their 254-pound (115 kg) shell, AP or HE, existed the barrle at a muzzle velocity of 2,495 ft/s (760 m/s). Thus in battle, they were likely to fire their whole broadside at max range, not waiting for the secondaries to engage.

Light Artillery

Torpedo boat threat was well understood by the admiralty as as previous ships she had an impressive range of smal caliber fast-firing guns:

-The core was fourteen 4.7-inch/40 Type 41 QF guns, mounted in casemates of the hull and two in the superstructure. They fored a 45 Ib shell at 2,150 ft/s

-They also came with four 12-pdr/40 12 cwt QF guns, plus four 12-pdr/23 QF on high-angle mounts for AA fire alread, doubling as saluting guns. Both fired the same 12.5 Ib shells at 2,300 ft/s or 1,500 feet per second.

Torpedo Tubes

These cruisers were fitted with three submerged 18-inch (457 mm) torpedo tubes, each on a broadside, one in the stern. The latter was a training torpedo with some traverse, but the two broadside ones were fixed. The torpedo model was likely 18″ (45 cm) Ho Type 38 No. 1 (1905) purchased from Whitehead with a Gyroscope, three-bladed propeller, 220 lbs. (100 kg) Picric Acid or Shimose warhread, and ranges of 1,100 yards/27 knots or 3,300 yards/20 knots. More

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 14,636 tons (normal), 15,595 long tons full load |

| Dimensions | 485 x 75.6 x 26 ft (147.8 x 23 x 8.0 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts VTE, 28 Miyahara WT boilers, 22,500 shp (16,800 kW) |

| Speed | 21.25 knots (39.36 km/h; 24.45 mph) |

| Range | |

| Armament | 2×2 12-in, 4×2 8-in, 14× 4.7-in, 8× 3-in, 3× 17.7 in TTs |

| Protection | Belt 4–7, Deck 2, Bulkheads 1, Barbettes 2–7, Turrets 9, CT 8.0 in |

| Crew | 817 |

Construction

Construction was delayed due to a lack of shipyard facilities as much as of skilled workers, they fell in low priority in construction order, which in part explains their very late release.

-Kurama in particular was started in Yokosuka Naval Arsenal on 23 August 1905 and should be the lead ship. But construction dragged on until launch on 21 October 1907 as priority was given to the new Kawachi and Settsu plus the repair and reconstruction of the captured ex-Russian ships. She was only completed on 28 February 1911, making for a five years time.

Ibuki on her side was started two years later, she had to wait for the slipway used by IJN Aki became available in Kure Naval Arsenal. However the latter took advantage by stockpiling material and components and this was ready to break a record construction time of five months, only beaten by HMS Dreadnought (four months). The decision to go from reciprocating engines to turbines on Ibuki made her a high priority over IJN Aki, so she was first Imperial Japanese Navy ship fitted with steam turbines. Aki was delayed for five months as it was estimated the cruiser was better suited as a testbed.

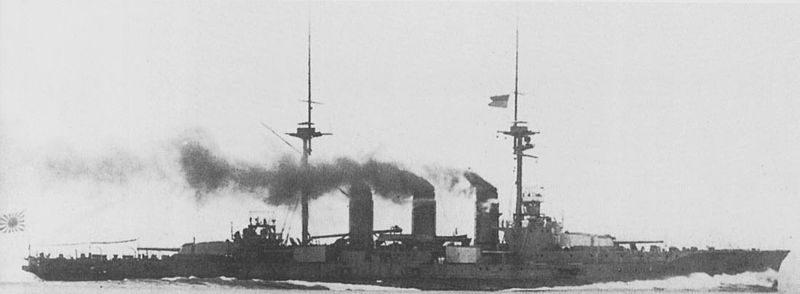

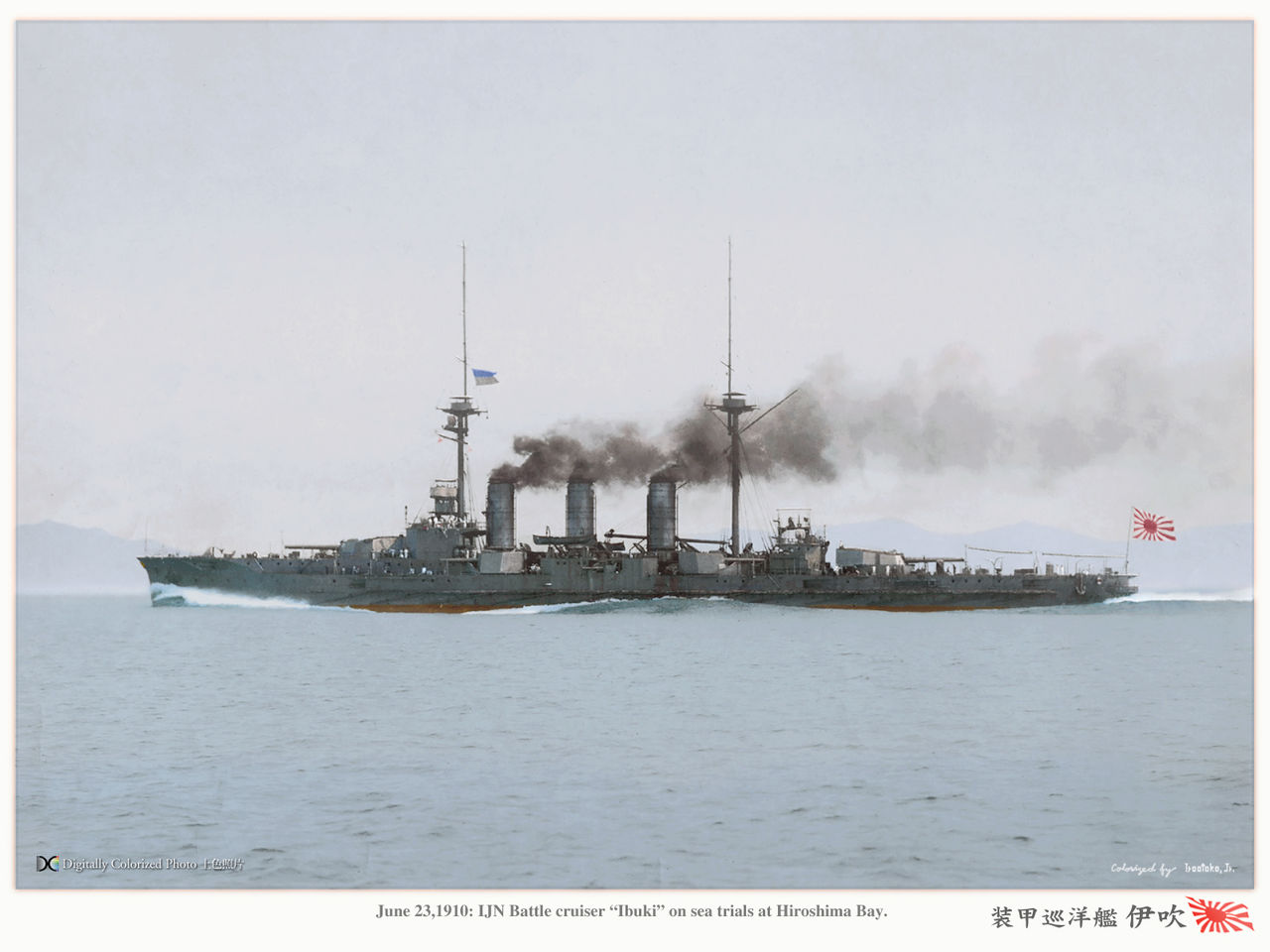

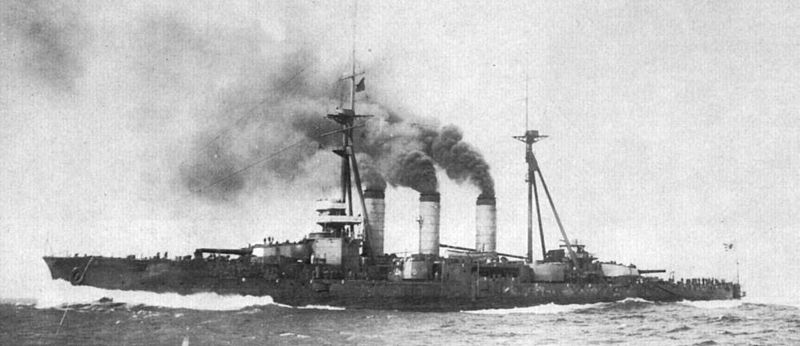

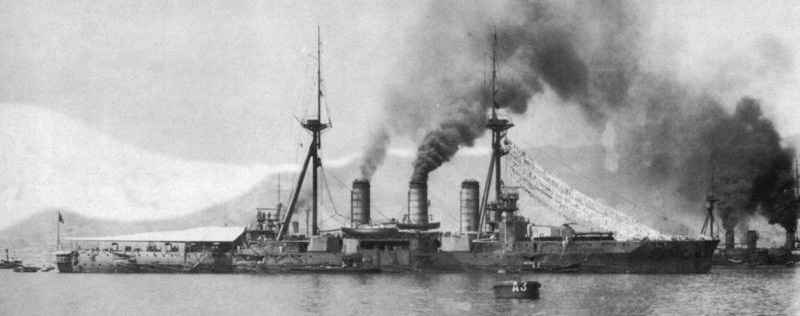

IJN Ibuki

IJN Ibuki

IJN in June, 23, 1910, colorized by Irootoko Jr.

Problems with her turbine engines delayed the full completion of Ibuki, compounding her construction started two years after her sister IJN Kurama still using reciprocating engines. Both were completed far too late, mostly due to Shipyard capacity. Ibuki emerged from Kure Naval Arsenal to be commissioned on 11 November 1907.

She made a first sortie, doubling as shakedown cruise to Thailand, attending the coronation ceremony of the Thai king Rama VI Vajiravudh. Not much happened until 1914, and she was mobilized with the rest of the fleet when Japan declared war on the central Empire and started to go after German possessions in the Pacific and Asia. She thus took part in the hunt for the German light cruiser SMS Emden in 1914. But she never caught her.

She also escorted a convoy of ten troopship with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force aboard, crossing the Tasman Sea with the cruisers HMS Pyramus, HMS Minotaur. They went first to Albany in Western Australia in November 1914 and later departed with HMAS Sydney, to protect a large ANZAC convoy (20,000 men and 7,500 horses) across the Indian Ocean to participate to the British campaign against the Ottoman Empire.

They were landed in Egypt where they trained for many months before being thrown into the furnace of Gallipoli.

The fleet moved ahead from Albany at 8.55, in all 36 transports and 3 escorting cruisers, in case the Germans would shown along the way. Ibuki escorted the liners Ascanius and Medic carrying troops from South and Western Australia. During a rain squall they fell out of the line and of sight, Ibuki taking HMAS Melbourne’s position, starboard beam, while the latter wen astern of the convoy. They arrived off the Cocos Islands. Soon, HMAS Sydney was dispatched to the island and took part in the Battle of Cocos. Meanwhile, Ibuki “shephered” the convoy, its most serious protection. Captain Kanji Katō wanted to engaged Emden, but this was denied by the convoy commander aboard HMAS Sydney. The Royal Australian Navy however noted this and saluted the “samurai spirit of the Ibuki” each time an IJN Imperial Japanese ships visited Australia in WWI and the interwar. Little did they know…

The rest of the war saw mundane tasks, fleet training, gunnery drills and patrols in the Pacific or Japanese waters. IJN Ibuki was still active when her country decided to sign the Washington Naval Treaty. The axe was to fell and the “armoured cruiser/battlecruisers” of the two classes were thussold for scrap on 20 September 1923, despite their age. The guns however were all salvaged and reused in shore batteries, installed at Hakodate in Hokkaidō, and along the Tsugaru Strait. They were still active in WW2, thus a reason, why the USN mostly launched air strikes, and only later closed for shire bombardment of industrial eras, but at such distance they were never threatened. A full review of IJN shore batteries and fortifications are awaited as part of the Naval Fortifications portal.

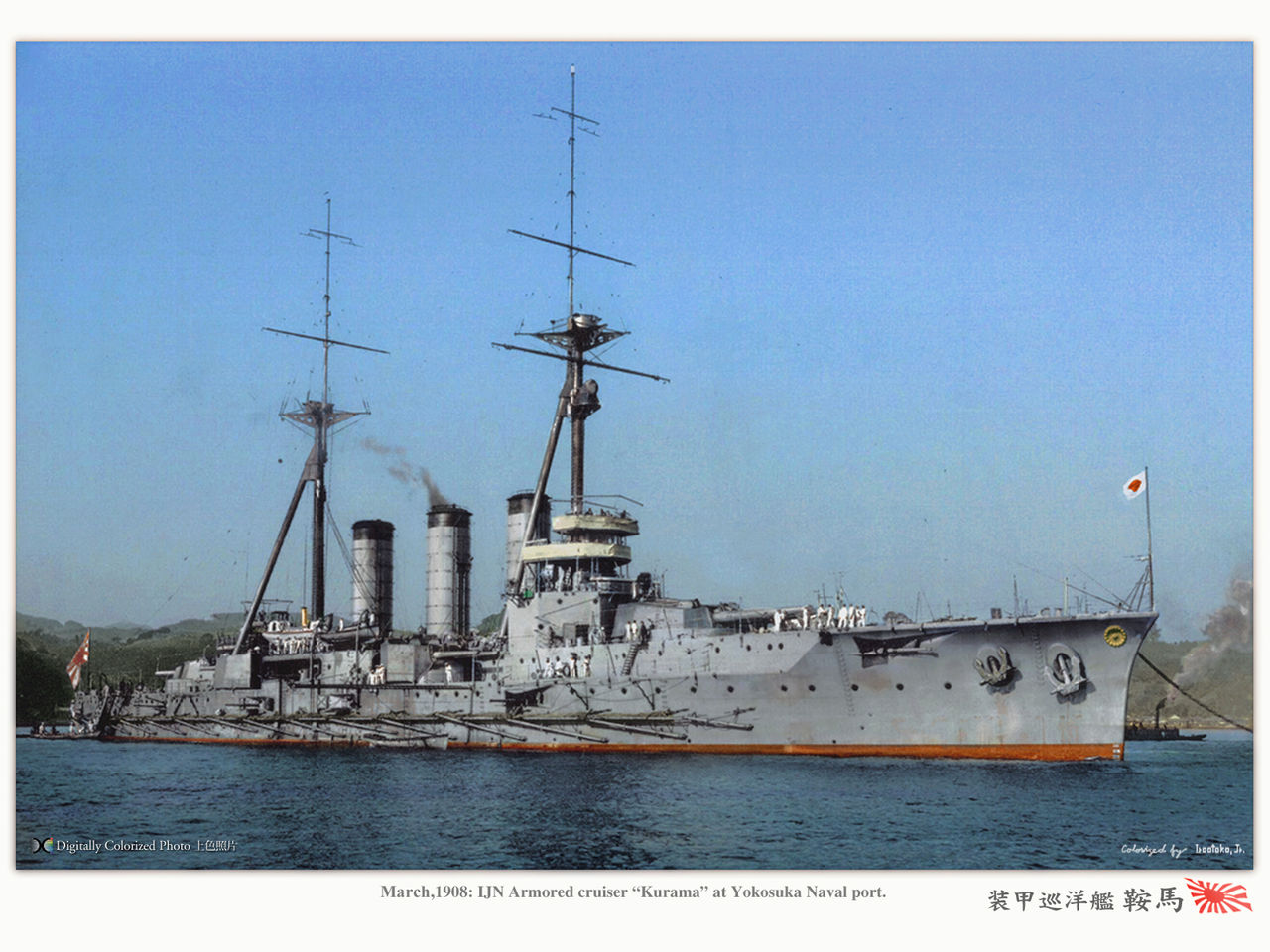

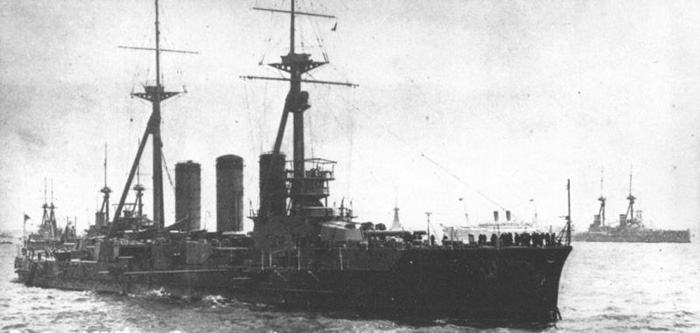

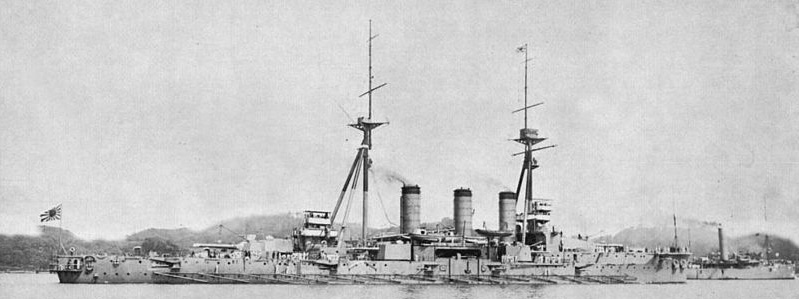

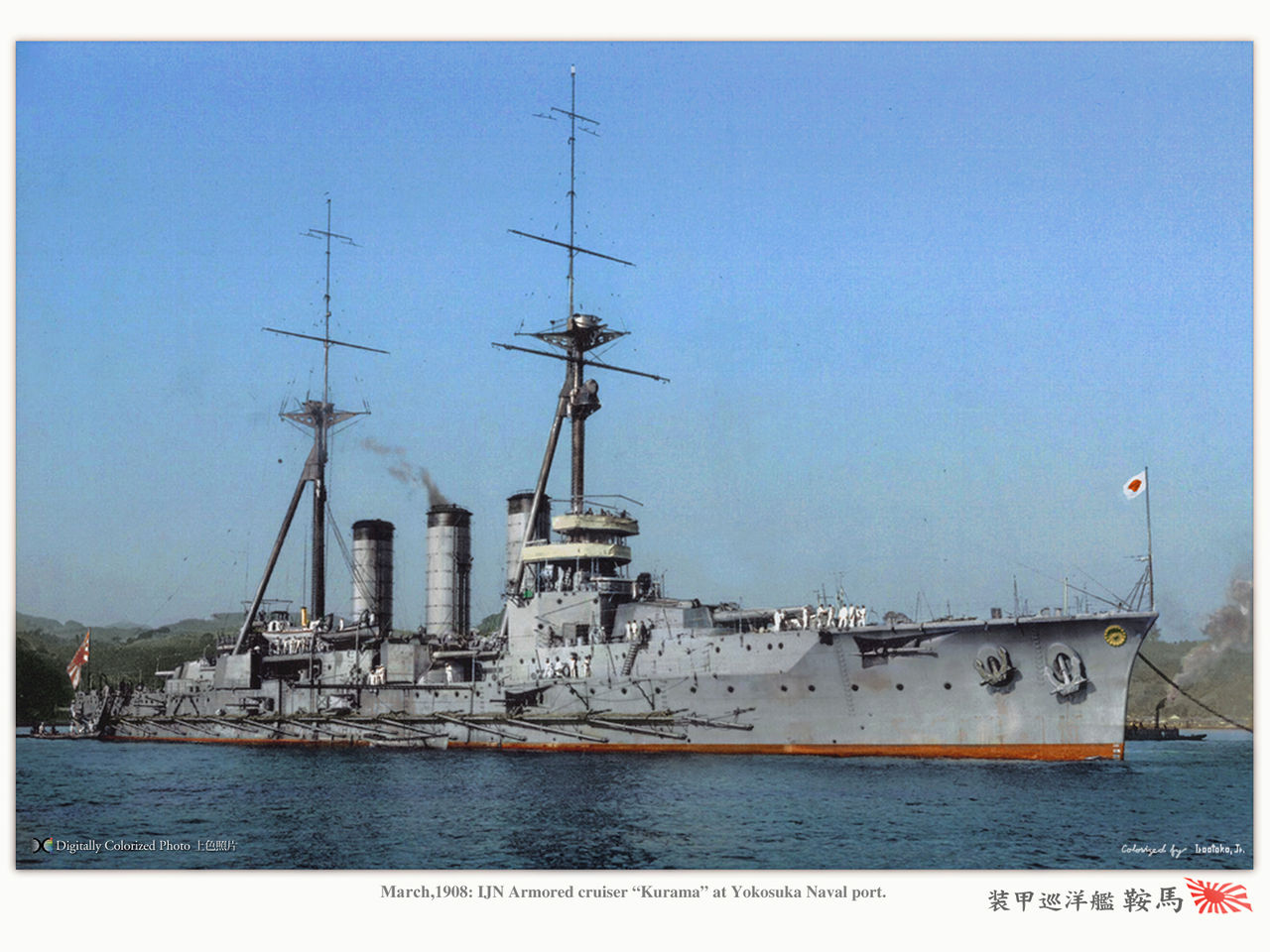

IJN Kurama

IJN Kurama

IJN Kurama colorized by Irootoko Jr.

Problems encountered with IJN Ibuki’s geared turbine engines led the Navy to decide for Kurama to keep her planned vertical triple expansion reciprocating engines. This was fortunate as she was already three years beyond sechedule, delayed at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal.

Kurama in sea trials. She was just half a knot slower than her turbine-driven sister.

Shortly after commissioning, she carried the mark of Admiral Hayao Shimamura for a long trip (doubling as shakedown cruise) to Great Britain. She was to represent Japan in the Coronation Fleet Review for King George V, held in Spithead, on 25 June 1911.

IJN Kurama at the KGV Cornonation review in Spithead

IJN Kurama next trained and made several voyages to China and the Pacific until 1914. Like her sister, she was mobilized, after failing to catch Graf Spee’s fleet, to protect British merchant shipping in the South Pacific. Soon, she joined the newly completed IJN Kongō and Hiei) to support landings in the Caroline and Mariana Islands, both former German colonies. They did not stood a chance.

From the 1st South Seas Squadron search for the East Asia Squadron, departing on 14 September 1914 to Truk on 11 October, protecting troop carriers as part of the squadron task to occupy the Carolines.

The squadron was based in Suva, Fiji by November 1914, to prevent a return of the East Asia Squadron. IJN Kurama was flagship of the 2nd Squadron in 1917. She was then transferred to the 5th Squadron in 1918, but nothing much happened. She trained, between fleet exercizes and gunnery drills.

In 1921 she was assigned to the northern fleet with the intention of taking part in the East Siberian campaign, supporting the “white russians” based in Ekaterinburg. She covered the landings of Japanese troops in Russia during the Siberian Intervention and went back home for a short refit and training. Unfortunately the internatonal coalition cold not prevent the Red Army successes and was forced to evacuate.

However like her sister she was disarmed in 1922 followed the signature of the Washington treaty. She was stricken in 1923 and scrapped while jer artillery was salvaged, two 203 mm turrets engine as coastal batteries around Tokyo Bay.

Sources/read more

Books

Conway’s all the world’s battleships 1860-1905

C.E.W. Bean, The Story of Anzac from the outbreak of war to the end of the first phase of the Gallipoli Campaign

O’Brien, pp. The Anglo-Japanese alliance, 1902-1922, p. 142

Evans, David (1979). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941. NIP

Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. NIP

Gibbs, Jay (2010). “Question 28/43: Japanese Ex-Naval Coast Defense Guns”. Warship International. XLVII (3)

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. NIP

Lengerer, Hans & Ahlberg, Lars (2019). Capital Ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1868–1945, Zagreb Despot Infinitus

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War I. London: Random House Group. 2001. p. 167.

Links

Ibuki on blog.livedoor.jp – colorized photos

On wiki.wargaming.net/ru for plans

On forum.warthunder.com for plans

On nids.mod.go.jp

Main artillery on navweaps.com

20.3_cm/45_Type_41_naval_gun

On en.wikipedia.org/

On naval-history.net

Japanese Battlecruiser Ibuki: Ibuki Class Cruiser, Armoured Cruiser, Imperial Japanese Navy, Mount Ibuki, Japanese Cruiser Kurama

renditions on shipbucket.com

Jap cruisers on battleships-cruisers.co.uk/

On militaryfactory.com/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign