Japanese vs Chinese Navy, 17 September 1894

The first major naval battle of the industrial era

Less well known than Tsushima, the battle of Yalu River is nevertheless one of the few naval battles that occurred at the end of the Century, with relatively modern ships. Other contemporary examples had been the battle of Cuba, and of Manila Bay in 1898, opposing a young American navy and the old Spanish Empire.

Yalu was not a prelude to Tsushima as adversaries were not judged -from the Japanese point of view- of the same caliber (The Russian navy vs. the Chinese one). But both were a mirror of the young, ambitious and aggressive Japanese Navy which was seen as an instrument of imperial challenge after the end of the Meiji era and the rise of nationalists. China, on the other end, was still mined by corrupted officials and had a too conciliant international policy that allowed foreign concessions and fed imperialist appetites from nearly all industrial nations, Japan included. The old empire indeed was seen largely as a large untapped industrial market, and Western commercial interventions were backed up by force if needed. Throughout the XIXth century several wars (with Britain, France, the USA) saw all-out easy victories, as the Chinese fleet mostly counted armed junks and few modern vessels.

Context: The first Sino-Japanese war

The first Sino-Japanese war was motivated over influence of Korea.

The second one was of course set in the XXth century and lasted from the early 1930s to 1945. What happened was a shift in dominance from a weakened Qing Empire, unable to modernize its military to Japan’s after a successful Meiji Restoration. As a result of the war, China was humiliated, loosing Korea as a tributary state, and Japan only left with more resolve and confidence in its rising star.

The war erupted after a casus belli, First Punic war style: On June 4, the Korean king, Gojong, seek help from the Qing government in suppressing the Donghak Rebellion, and the latter complied, sending general Yuan Shikai as its plenipotentiary before the main contingent of 28,000 men. But this was seen by the Japanese as a violation by the Convention of Tientsin, as they claimed to have not been informed. In response, the latter sent a 8,000-troop expeditionary force (Oshima Composite Brigade) in Korea. Any reform of the Korean government was refused, and later when the Koreans asked the Japanese troops to leave, the latter bluntly refusing. As events unfolded, in early June, the brigade occupied the Royal Palace in Seoul and replaced officials by a pro-Japanese government, which was understandably seen as an outrage by the Qing Empire.

Opposing Forces

China

On land, the Qing army has no national army. As a whole, there were separate forces based on ethnicity, and sub-divided into independent regional commands. There was however a local Beiyang Army, born from the Huai Army (experienced by dealing with the Taiping rebels), well-equipped with modernized equipment and well trained. This force would bear the bulk of the Japanese assault. However this forced was also largely unsupported as pleas for help from other regional armies failed. Despite of this, pronostics by International experts saw it crushing the Japanese.

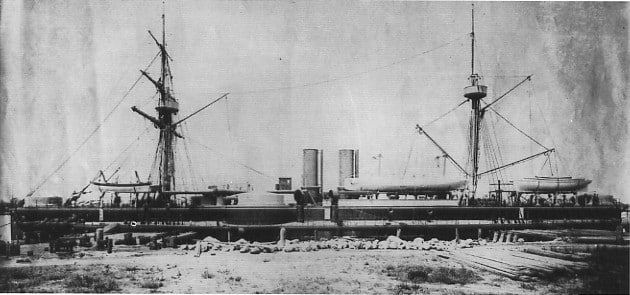

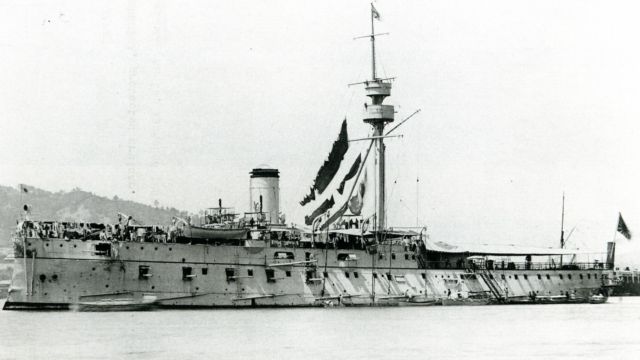

Battleship Ting Yuen. The Japanese has nothing equivalent in 1894.

The local Beiyang fleet was also the best of the whole Empire, pat of the four modernised Chinese navies in the late Qing dynasty: Northern (Beiyang), Southern (Nanking), Foochow and Canton. From 1880, China started to order ships abroad, modernize its training, with the aid of a few British Officers. The modernized Foochow fleet however was entirely sunk by the French Navy over Indochina in 1884, and it’s later rebuilding was largely supported by British and Germans, while Japan was at that time purchasing ships from France. It should be noted also that the fleet lacked ammunitions and more modern ships, as funds were embezzled by corrupt officials (even during the war), the Empress Dowager Cixi even spending military funds on renovating the Summer Palace.

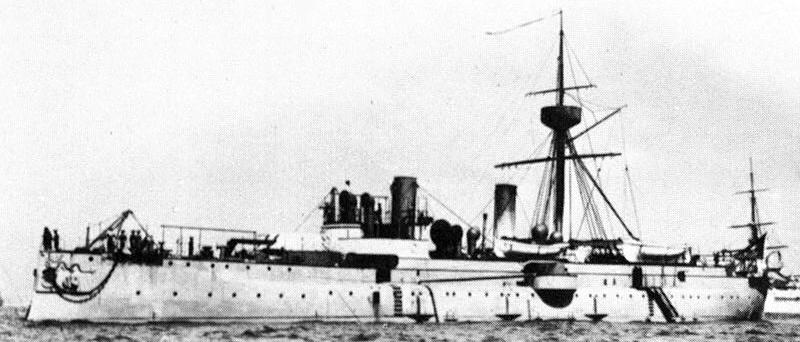

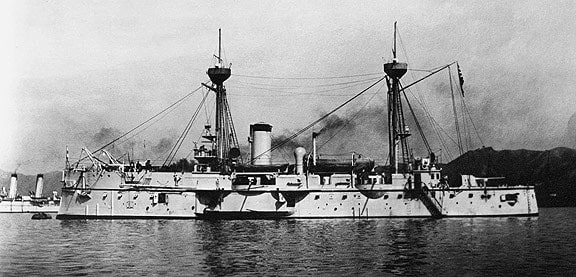

Armoured cruiser Jing Yuan (King yan class).

In 1894, The Beiyang fleet was considered first-rate in Asia, largely supported by Li Hongzhang, Viceroy of Zhili. She counted two ironclads called “armoured turret ships” (Ting Yen class), 8000 tons German-built battleships, but also the armoured cruisers King Yuen, Lai Yuen, protected cruisers Chih Yuen, Ching Yuen, Torpedo Cruisers Tsi Yuen, Kuang Ping class, Chaoyong, Yangwei, and the coastal warship Pingyuan.

Japan

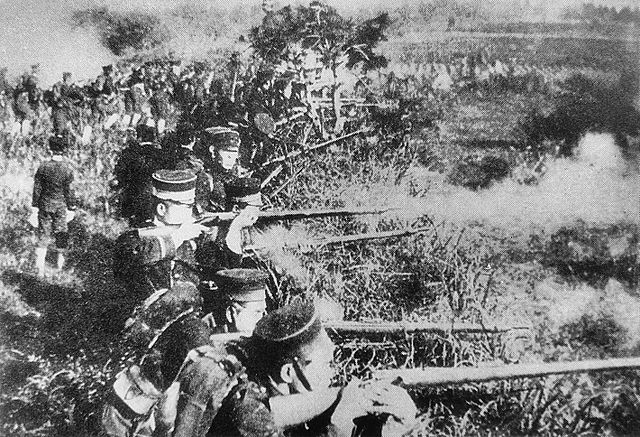

On land, the Japanese infantry, first trained and formed by French officers, has been from 1885 onwards re-modelled after the Prussian model. This army was well equipped with German guns, had Western, high level standard doctrines, military system and organization. Mobility was improved by enhancing logistics, transportation, and structures. In 1894, 120,000 men and four divisions were mobilized.

A bit like the American Navy in 1898, the Japanese Navy was seen largely as a young underdog in 1894. Officers has been formed by the British Navy, and an academy was set up for technical training and background by France. Therefore the Jeune Ecole came to influence largely Japan’s first fleet, largely based on cruisers supported by torpedo boats, that were in theory to render battleships obsolete.

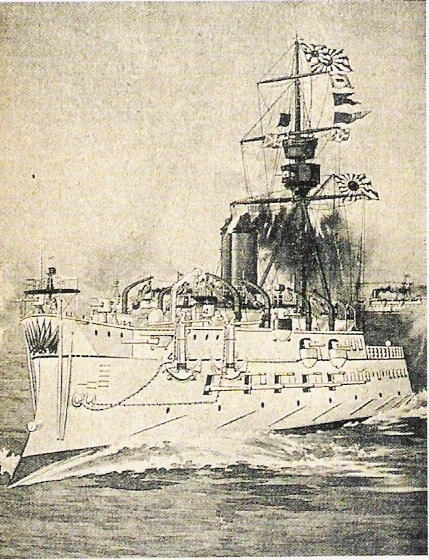

Matsushima, built by engineer Emile Bertin, flagship of the Japanese navy at Yalu.

The first expansion bill was passed, ordering 46 vessels, including 2 cruisers in 1881. Orders were delivered mainly to French and British yards, while the Yokosuka yard was refit by French engineer Emile Bertin in 1886, allowing to built large all-iron hull ships. The first HTE engines were introduced in 1892 and the first VTE in 1890 (Cruiser Oshima). A new naval plan was passed in 1893, this time largely leaning towards British yards, but none of the ships would enter service before the war broke out.

As of july 1894, the Japanese mustered virtually all their available warships into one combined force. This counted 9 Protected Cruisers, Matsushima (flagship), Itsukushima, Hashidate, Naniwa, Takachiho, Yaeyama, Akitsushima, Yoshino, Izumi, the cruiser Chiyoda, the Armored Corvettes Hiei, Kongō, and the old Ironclad Warship Fusō.

25 July 1894, Battle of Pungdo

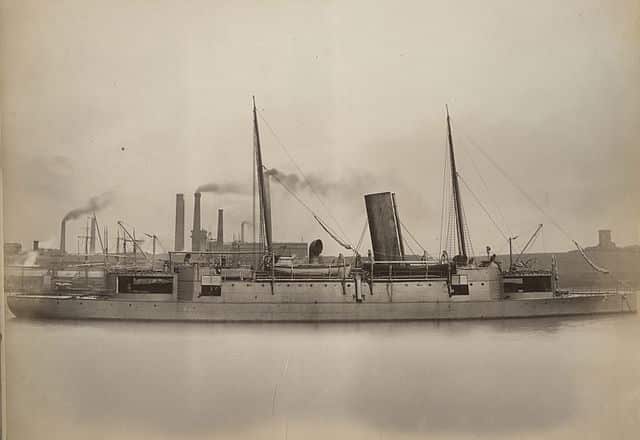

Also called the sinking of the Kow-shing, it was a small scale engagement, between the cruiser Naniwa (detached from the Japanese flying squadron off Asan bay), and the Chinese cruiser Tsi-yuan and gunboat Kwang-yi, both at sea to reinforce the escort (gunboat Tsao-kiang) of the transport Kow-shing. Guns blazed for an hour, after which the damaged Chinese cruiser fled, the Kwang-yi ran aground to avoid sinking, and the Kow-shing sank, with nearly all hands. Some were rescued by the gunboats Itlis (German) and Lion (French). The Kwang-yi was a 2,134-ton British merchant vessel from the Indochina Steam Navigation Company of London, carrying 1,100 troops plus supplies and equipment and one Prussian officer. This led to a diplomatic crisis with Great Britain. However Naniwa’s captain Tōgō Heihachirō became a celebrity in Japan for this feat.

Japanese cruiser Naniwa

Meanwhile the Battle of Seonghwan and Battle of Pyongyang (1894) would make the headlines. After a first engagement at Asan in August, the Japanese had free hands to converge from four direction on Pyongyang. The city fell on 15 September. According to posterior accounts, the Chinese lost 2,000 killed and around 4,000 wounded. However, the bulk of the action would take place two years after at sea.

17 September 1894, prelude to battle

At that time, the Beiyang fleet was located off the mouth of the Yalu River. The latter was crossing the northern border between Korea and China, ending in the yellow sea. The name in Manchu, signified “the boundary between two countries”. It should be noted that there was a second battle of the Yalu, this time with the Russian Empire ground forces in 1904 and the site was also crucially nearby major battles of 1950. Japanese objective was simple, as command of the yellow sea would allow Japan to transport troops to the mainland. However the Chinese fleet was a tough nut to crack, with two battleships (the Japanese had none).

Chinese cruiser Chao Yong, as built, on the Thames (1880). She was armed with two 254 mm (10.0 in) cannons, four 120 mm (4.7 in) cannons and 12 smaller guns. She was very similar to the previous Chilean Arturo Prat.

At some point Li Hongzhang recommended the Beiyang fleet to be kept safely in Lüshunkou (Port Arthur), a naval stronghold, safe from a naval engagement far at sea that would be at the advantage of the fast and agile Japanese. However the Guangxu Emperor insisted that convoys passed safely, and this required neutralizing the Japanese fleet in any case; In fact the battle occurred while the Beiyang fleet was back from the mouth of the Yalu River, escorting a convoy, and then intercepted by the Japanese.

Japanese armoured cruiser Matsushima, Japanese flagship. She was badly burnt and nearly lost, showing this was never an easy fight.

Respective Strengths

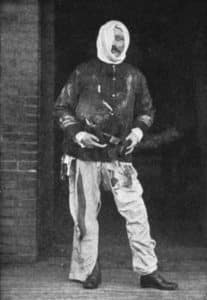

On paper, the Chinese advantage with big guns and armour was completed by the presence of Western naval advisors: Prussian Army Major Constantin von Hanneken, appointed to Admiral Ding Ruchang and W. F. Tyler, (Royal Navy Reserve) his assistant. Philo McGiffin (former U.S. Navy ensign, Weihaiwei naval academy instructor) appointed to Jingyuan as co-commander. It seems however that the gunners did not had sufficient practice, a result of a serious lack of ammunition. The fleet was arranged in a line facing southward, with the two battleships in the center. There was another group of four ships, that had to catch up and would not be ready before 14:30.

The Japanese Combined Fleet comprised, in addition of the flying squadron described above (Yoshino, Takachiho, Akitsushima, and Naniwa, under command of Tsuboi Kōzō), consisted in a main fleet: Cruisers Matsushima (flagship), Chiyoda, Itsukushima, Hashidate, ironclads Fusō and Hiei, under command of Admiral Itō Sukeyuki.

Japanese Ironclad Fuso (1877), after rebuilt at Yokosuka (July 1894). Slower, she was heavily engaged, hit many times by 6-inch (152 mm) shells, but none penetrated.

Three protagonists of the battle: Baron Tsuboi Kozo (Jap. combined fleet), Admiral Ding Ruchang (Beiyang Fleet) and co-commander Philo Mc Giffin (here at the hospital after the battle). He became a national celebrity in the US after the war.

Start of the battle

When the two battle lines approached each other, the Chinese fleet formation had somewhat been broken into a rough wedge, due to bad signal interpretation, and diverging speeds. Admiral Sukeyuki Ito ordered the flying squadron to engage the Chinese right flank. The Chinese however opened fire at a range of 5,000 metres (5,500 yd), and missed because of extreme dispersion, while the Japanese waited patiently for twenty minutes, closing range for maximal effect. Their maneuver consisted in heading diagonally across the Beiyang Fleet at twice the speed, making them difficult to hit. They then headed straight for the center, then, puzzling the Chinese, moved around the right flank and started to pummel the weakest ships.

The Beiyang Fleet at Weihaiwei.

The Chinese right flank is dislocated

After holding their fire until the last possible moment, the Japanese unleashed it on the Chaoyong and Yangwei, which were battered and soon rendered inapt for any further engagement. The squadron then turned northward to face Chinese reinforcements coming from the Yalu river, but doing this, it circled round the Chinese. Meanwhile, the Japanese main squadron starting the same manoeuver as the flying one, ended the other way, completing the encirclement of the Chinese fleet. Therefore, the Beiyang Fleet ended sandwiched between the two Japanese squadrons, a classic of the Royal Navy, giving a much-needed local superiority against the center battleships.

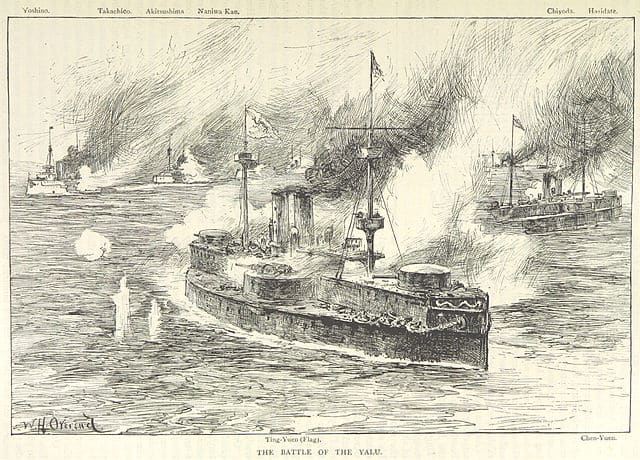

Western Illustration of the Chinese battleships

The Chinese center is fully engaged

Dingyuan and Zhenyuan hulls, according to their excellent protection, suffered little damage, but following the French Jeune Ecole practice, the Japanese targeted the weaker superstructures. Soon, both ships were ablaze and suffered many casualties. Mostly the crews were cut to pieces by the numerous quick-firing secondary and tertiary guns of the Japanese, which were now close enough to have every single one speaking.

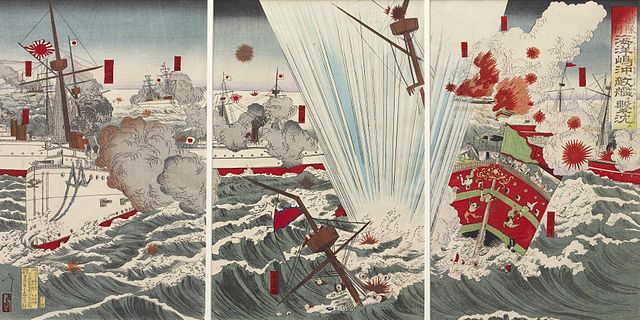

Matsushima attacking Chinese warships (Shunsai Toshimasa)

The Chinese left flees and partly escapes

Meanwhile cruiser Zhiyuan broke the line and attempted to ram the Japanese cruiser, and latter tried to rally fleeing ships from the left wing. She was soon caught, battered and sunk by the flying squadron. The trap was not properly closed, as in chasing (and destroying) the cruiser Jingyuan, leaving other ships fleeing northwards unmolested. Eventually Admiral Itō completed the annihilation of what’s remained in the circle, targeting superstructures, but doing so, also taking serious damage: The Yoshino, Akagi, Hiei, Saikyō Maru were hit and/or put out of action. The Matsushima probably suffered most, as two 12-inch shells penetrated the deck, blasted ready rounds, putting the ship ablaze and forcing the admiral to carry his mark to Hashidate.

“Battle of the Yellow sea” by Korechika

End of the battle

The engagement ceased at sunset, when most ships from the Beiyang fleet had been sunk, seriously damaged and fled, but the two battleships remained, although short of ammunitions. As a result, they were able to retire and fight another day. However ultimately the Japanese would sink the Ting Yuen (on February, 6, 1895), torpedoed by TB.26 at the battle of Wei Hai Wei, while the Chen Yuan was engaged heavily by Japanese army guns three days after, sunk in shallow waters and would be later refloated, repaired, and reused by the Japanese (renamed Chin Yen). She would be used as a flagship in 1904, but was retired eventually in 1910 and used afterwards for training in home waters.

Both Chao Yung class protected cruisers were sunk, the Chi Yuan, badly damaged, would be captured later in February 1895, the Chih Yuan (namesake for the class) was also sunk and the Ching Yuan also captured in 1895, as well as the armoured cruiser Ping Yuen, while both King Yuan armoured cruisers would be sunk, one in this battle, the other at Wei-Hai-Wei.

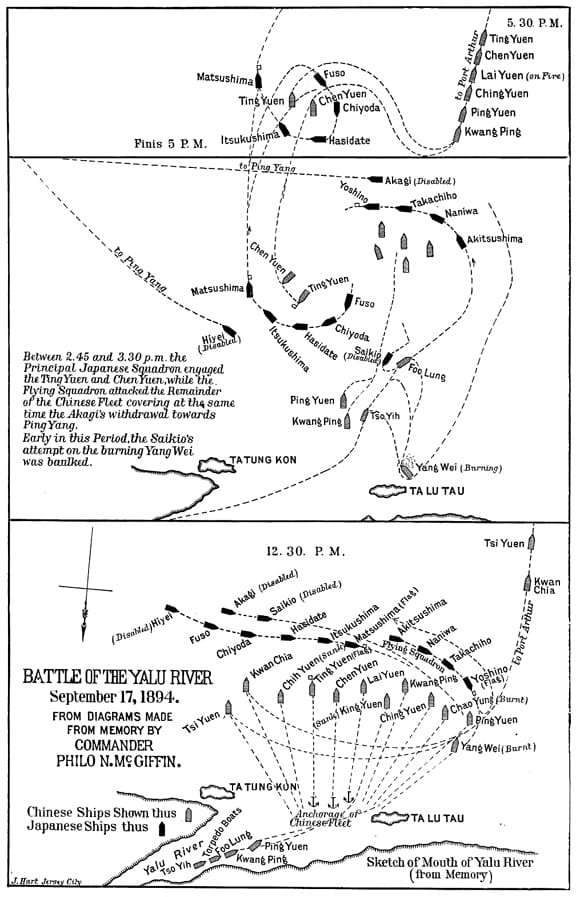

Global map of the battle, mid-day, afternoon and evening.

Post battle analysis

Admiral Ding’s decision not to change formation had been pointed out, but this was due to the unwillingness of Dingyuan’s captain to not change formation himself, pass the order to other ships, while the flying bridge of the flagship was later destroyed, Ding apparently injured and the mainmast later destroyed, leaving no way to signal orders. Meanwhile the Chinese fleet wisely reorganized itself in three-ships self-supporting formations. From some time, when distances fell below 3000 m, Chinese 12-inch (305 mm) and 8.2-inch (208 mm) guns apparently failed to score any hit. One of the “legends” of the battle was that Chinese heavily varnished and polished wooden decks burnt more easily.

Jiyuan and Guangjia turned and fled as soon as the Japanese opened fire, therefore weakening the Chinese position, however the full encirclement never happened as the flying squadron was soon diverted to oppose the rallying Chinese ships, previously escorting a convoy (cruisers Kuang Ping and Pingyuan, Fu Lung and Choi Ti TBs). Slower Hiei, Saikyō Maru and Akagi had been severaly hit by the Chinese left, therefore diverting more ships in support. One of the Chinese heroes of the battle had been Zhiyuan’s captain: Whereas his ships was crippled and burning, rather than fleeing he decided to ram and opportunity target, the nearby cruiser Naniwa. However, the slow cruiser never made it. The Japanese immediately concentrated their fire and sank it.

It has been said that the rapid-fire guns (and fast ships) has been a factor, as opposed to a relative lack of training and lack of ammunition from the Beiyang Fleet. Indeed, if the two battleships had been able to fire more, and with more precision, there was no doubt the Japanese would had been at a serious disadvantage as none of their ships was protected enough. The Matsushima (flagship) was seriously crippled, the Hiei would be in repairs for the duration of the war, the Akagi was burnt from stern to stem, and the converted liner Saikyō Maru, after taking four 12-in hits was definitely out of the way. It was a bold gamble and afterwards a major propaganda victory.

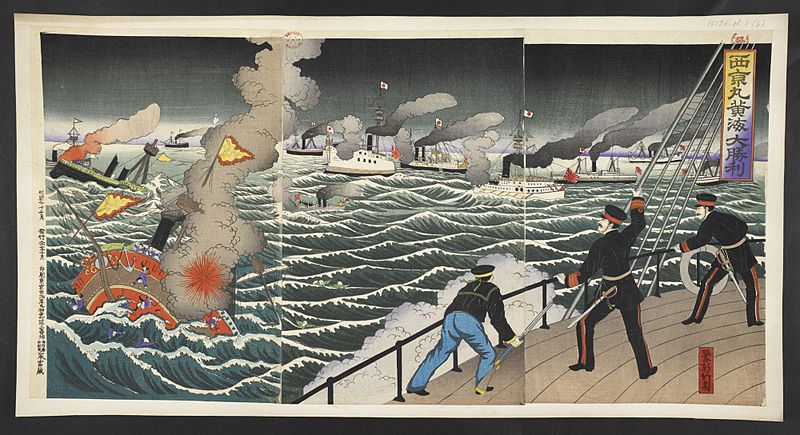

Saikyō Maru, Japanese wooden block painting.

The tactical result was indeed overall, and despite later analysis, favorable to the Japanese, which strictly lost no ship, and strategically “cleaned” the Yellow sea of Chinese escorts. On a strategic level, without Chinese reinforcement, the whole campaign’s ultimate fate made no doubt. Lessons for the Japanese has been to take battleships more into consideration (in fact the Chinese Chen Yuan became the first Japanese battleship), therefore departing a bit from French tactics, but keeping agility and maneuvering at heart. There is no doubt that some of the veterans were still present in 1905 with the confidence to undertake a whole new challenge: The destruction of two entire Russian fleets, then the world’s third largest naval power…

Aftermath of the battle

At first, the Chinese government denied this defeat, as a sizeable part of the fleet was able to retire at Weihaiwei. But Viceroy Li Hongzhang and Admiral Ding Ruchang served as scapegoats. International press praised the “rapid assimilation of Western tactics and training” by the Japanese that had taken a “much bigger adversary”. Some analysts however pointed out this battle as a near-draw.

The battle of Yalu did not ended the hostilities: This victory secured the Japanese position, to launch a crossing of the Yalu, and invade Manchuria. This was followed by the Fall of Lüshunkou (Port Arthur) and the sack of the city and massacre of the whole population. In Jan-Feb. 1895, the Fall of Weihaiwei followed. This was a sea-land battle, with the navy actively participating, the Japanese operations against fortified positions behind the cover of the cruisers Yoshino, Akitsushima, and Naniwa of the “flying squadron”. This secured most coastal access to the route of Beijing. In March, the Japanese occupied the Pescadores Islands (west coast of Taiwan). The Treaty of Shimonoseki was eventually signed on 17 April 1895 and the war was officially over.

Links & Sources

http://sinojapanesewar.com/yalu.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Yalu_River_(1894)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Sino-Japanese_War

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_naval_yalu_river.html

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign