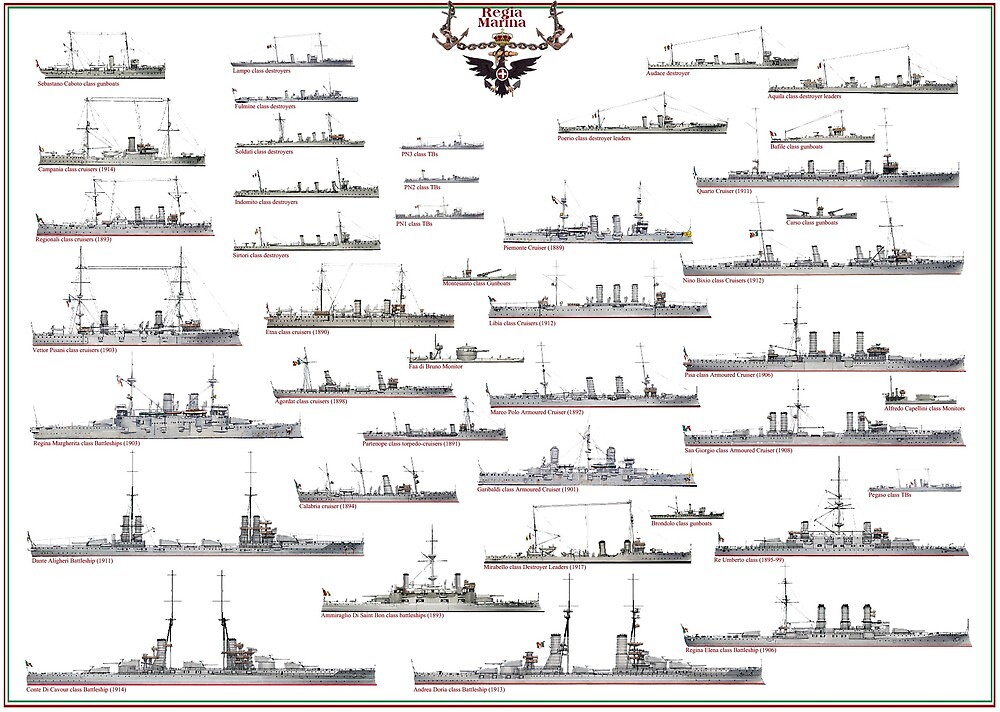

Regia Marina (1914)

Overview of the Italian Fleet (1914-1918)

Overview of the Italian Fleet (1914-1918)

An amalgamation of local navies

Like Germany, Italy was the result in 1914 of a recent unified political construction, but predated by nearly ten years: The Unified Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed on 17 March 1861. From then on, the Italian navy was born, as the result of gathering disparate units from the Duchy of Bourbon, Sardinia, Tuscany, Papal States and Sicilia. The bulk consisted of the Sardinian warships – by far the most powerful with that of Bourbon, then Neapolitan Navy, all very well equipped.

The Battle of Lissa, 1866

Under the impetus of Count Di Cavour, the peninsula’s leadership hero figure, supported by Garibaldi, the Sardinian/Piedmontese combined fleet became the most modern in the Mediterranean, spawning notably the first Italian battleships. The Battle of Lissa, which the Austrians consider to have won, remains a bitter memory for the Italians, in spite of a true naval potential in 1866. The Battle at large also consecrated the great return of ramming as a naval tactic (since the antiquity), launching a durable fad in hull design that will last until 1906 (The Dreadnought too had a ram, and used it in anger).

- Agordat class cruisers (1899)

- Alessandro Poerio class scouts (1914)

- Amiraglio Di St Bon class Battleships (1897)

- Aquila class cruisers (scouts) (1916)

- Audace (ii) 1916

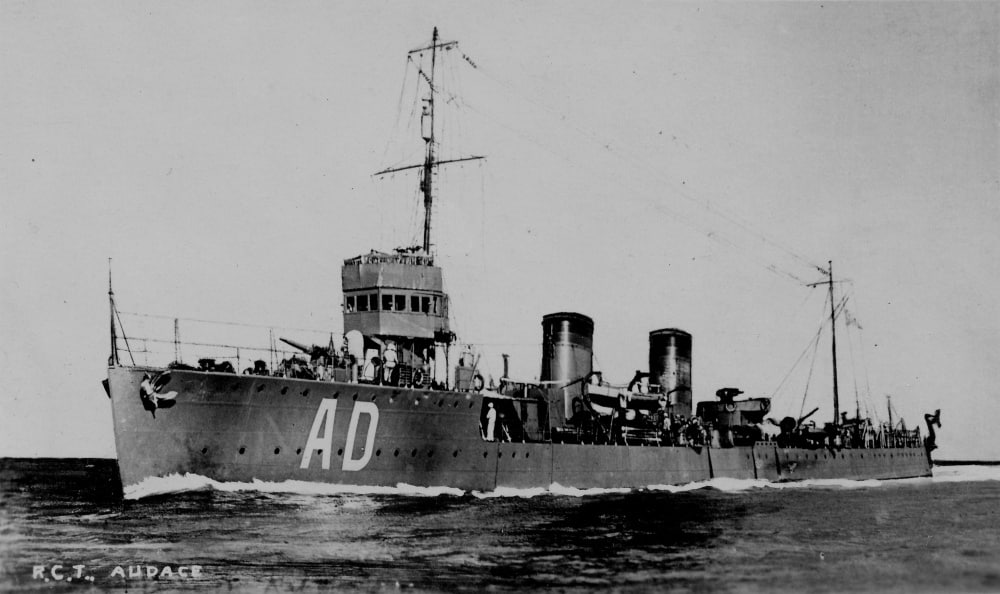

- Audace class destroyers (1913)

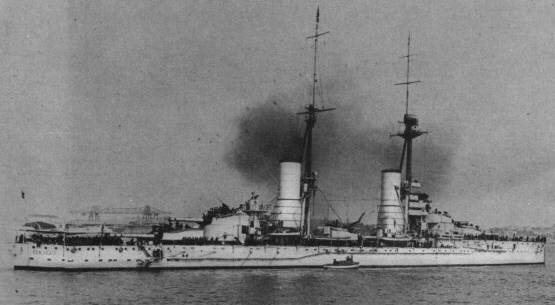

- Caio Duilio class ironclads (1879)

- Calabria (1894)

- Campania class cruisers (1914)

- Caracciolo class battleships (1917)

- Cavour class battleships

- Dante Alighieri

- Doria class battleships (1916)

- Etna class protected cruisers (1885)

- Garibaldi class armoured cruisers (1901)

- Generali class destroyers (1920)

- Giuseppe La Masa class destroyers (1918)

- Giuseppe Sirtori class destroyers (1917)

- Grillo class tracked torpedo launches

- Indomito class destroyers (1912)

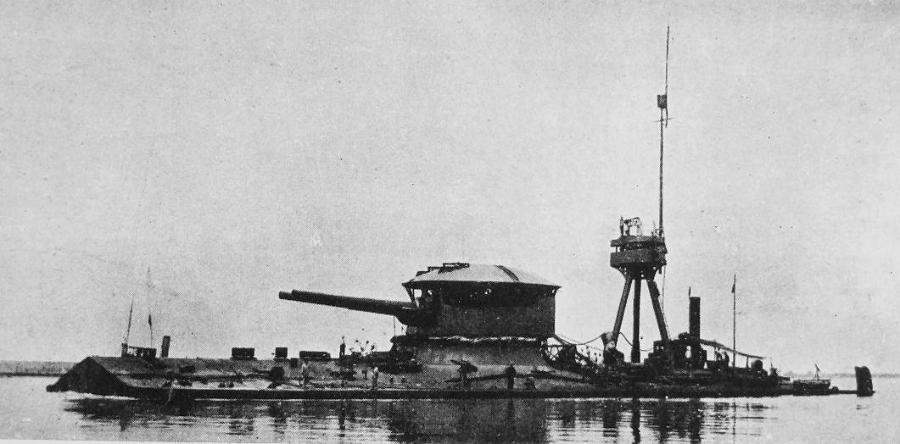

- Italian Monitors (1915-1918)

- Libia (1912)

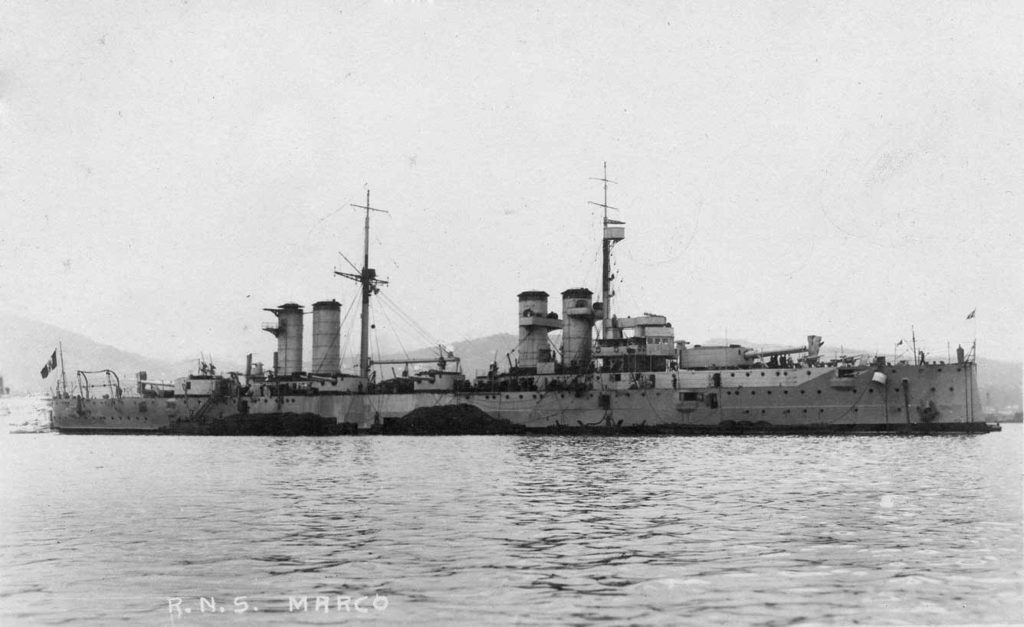

- Marco Polo (1892)

- Mirabello class scouts (1915)

- Nino Bixio class cruisers (1912)

- Pisa class armoured cruisers (1907)

- Protected Cruiser Piemonte (1888)

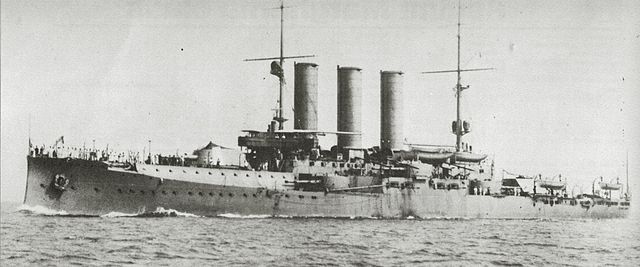

- Quarto (1911)

- Re Umberto class ironclads (1883)

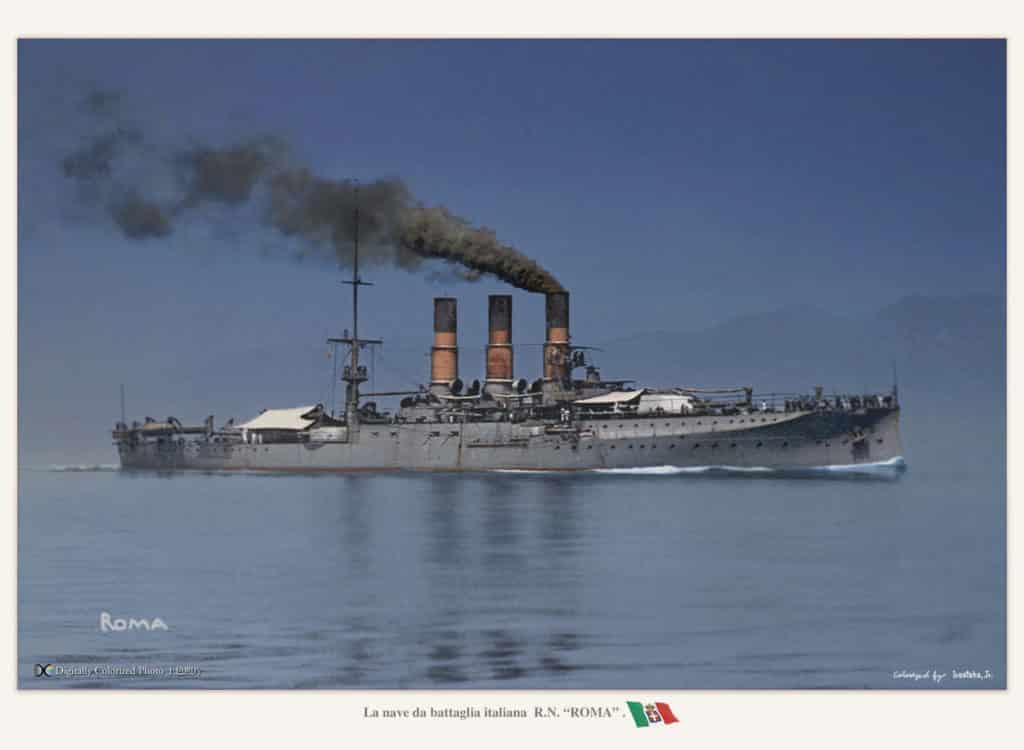

- Regina Elena class battleships (1904)

- Regina Margherita class battleships

- Rosolino Pilo class destroyers (1915)

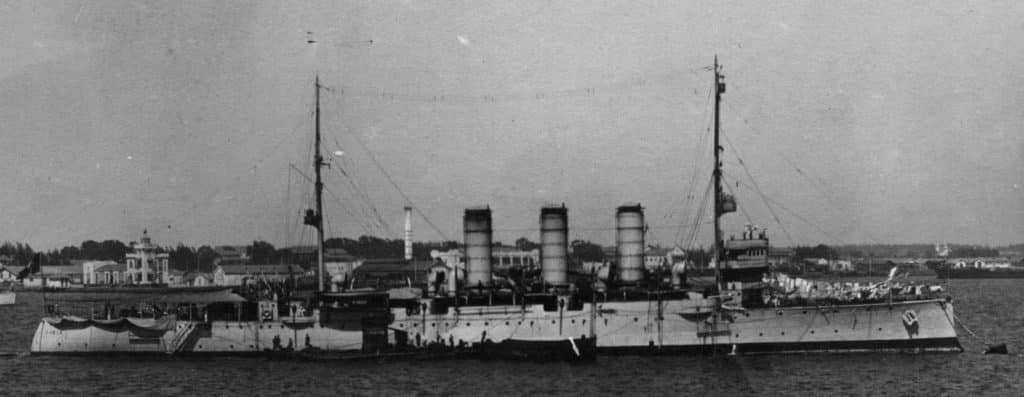

- San Giorgio class Cruisers (1907)

- Umbria class cruisers (1891)

- Vettor Pisani class armoured cruisers (1895)

- WW1 Italian Battleships

- WW1 Italian Cruisers

- WW1 Italian Destroyers

- WW1 Italian Submarines

- WWI Italian Torpedo Boats

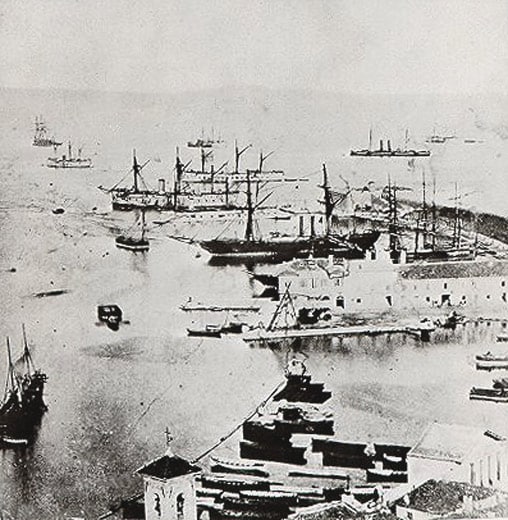

The Italian fleet at Ancona after the battle

Cuniberti breakthrough battleship design

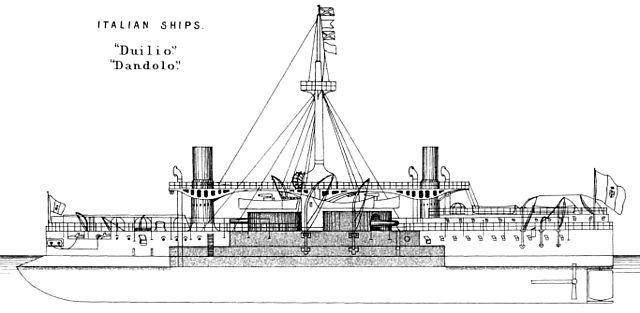

After Lissa, budgets were reduced and the confidence given to the navy largely decreased. Augusto Riboty in 1871 owes the desire to inject new blood to his fleet. He did it superbly, in particular by ordering the series of battleships Duilio and Italia, armed with formidable (unmatched then worldwide) pieces of artillery. These cannons were in addition modern and rapid-firing, and the feat surprised and alarmed the British Admiralty for its own assets in the Mediterranean. The great Italian engineer Cuniberti designed a range of truly excellent ships, including the last pre-dreadnoughts battleships, which were “near-dreadnoughts” in a sense, lacking a true monocaliber gunnery just because he had not been granted the right budget.

Duilio class ironclads, designed by Cuniberti (Brassey’s 1888).

Cuniberti’s four Regina Elena, were indeed considered the best in the category, thanks to a formidable secondary armament. Cuniberti wrote in an article published in Jane’s fighting Ships its famous plans of the Ideal battleship, a sort of modernized armoured cruiser, fast but equipped with same caliber heavy weaponry. The Admiralty, after lessons learnt at Tsushima, had been interested in it, and eventually “Jackie” Fisher ordered its most famous ship: The HMS Dreadnought, first monocaliber battleship worldwide.

Roma, Regina Elena class battleships, colorized by Irootoko

Budgetary constraints

In 1894-95 reverses in Africa were still detrimental to the navy, and it would be necessary to wait for the ministry of navy Carlo Mirabello for a new ambitious plan to be voted. Funds were still modest though, and construction of new heavy units was affected not only by some tradeoffs but also delays of 7 years to 10 years between the first drawings and tests, which rendered obsolete these ships when entering service. However, they were distributed in homogeneous classes, and of certain quality.

Strategic Objectives

On a strategic level, Italy had to face the Turks, Greeks, Austrians, but its tonnage was largely able to face these three fleets, even combined. The Greeks never had serious enmities towards the Italians, and only possessed a modest coastal force. It was quite the opposite with the Ottoman Navy, once so powerful, which remains a threat for the whole Eastern Mediterranean, and the Black Sea. In the Adriatic, it was of course Austria-Hungary, Italy’s great rival. The Italians sought since Lissa to obtain reparation for the outrage they had sustained on the part of Rear Admiral Tegetthoff. However, this rivalry lost ground for political reasons, since Italy became been part of the triple entente in 1885 (Germany-Italy-Austria-Hungary).

Battleship Caio Duilio in 1915

Rank in 1914

In 1914, Regia Marina (“Royal Navy”) was ranked seventh in the world, ahead of the Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Armada (Spain) and the Dutch, but behind the French, Japanese, Russian, German, American and British fleets. She could count on paper 17 battleships, 32 cruisers, 33 destroyers, fifty torpedo boats and a handful of submersibles. However, of these forces, the oldest cruisers (1885), were too small no match for the speed of modern naval operations, while the oldest battleships has been retrograded as coastguards or even dockyards and depot ships of batteries or torpedo boats, being totally obsolete.

Second-class torpedo boats were not of national construction, but came from the three great specialists of the time: Vosper-Thornycroft in Great Britain, Normand in France, and Schichau in Germany. Its cruisers were fairly light for the most part, and apart from the San Giorgio (1911), were inferior in tonnage and armament to their equivalents in the other navies. Italy’s first Dreadnoughts on the other hand, begun a little late in relation to other Nations except Austria-Hungary, were quite modern and integrated triple turrets, like the contemporary American and Russians 2nd generation dreadnoughts.

Conte di Cavour – colorized by Irootoko

*The magazine of Alfred Jane, a British subject, was complementary to the Brassey’s naval annual and well known in naval circles worldwide. Aside being directories of warships around the world, Jane’s was famous for its collection of articles related to tactics and naval strategy. Jane’s fighting ships had precise descriptions of the latest ships released, but also incorporated technical articles, including those of engineers of worldwide reputation like Cuniberti.

Battleships:

-Pre-dreadnoughts: Dandolo, Class Ruggiero di lauria (3) (coastal defense), Re Umberto (3), Amiraglio di Saint Bon (3), Regina Margherita (2), Regina Elena.

-Dreadnoughts: Dante Alighieri, class Cavour (3), 2 others in completion class Duilio and 4 super-dreadnoughts (See later. “war constructions”)

Armoured cruiser San Marco

Cruisers:

Armored cruisers: Marco Polo, class Vettor Pisani (2), class Garibaldi (3), class Pisa (2), Class San Giorgio (2).

Protected cruisers:, Piemonte, class Umbria (5), Calabria, Libia, 2 others under construction.

Minelayers: Partenope class and others (5)

Light cruisers: classes Agordat (2), Quarto, class Bixio (2).

Schoolship and GQG: Etna.

Italian cruiser Quarto

Destroyers: Fulmine, Lampo (6), Nembo (6), Soldati (10), Indomito (6), Ardito (2), Audace (2) classes.

Destroyer Audace

High seas TBs: Sirio (6), Pegaso I (4), Condore, Pelicano, Gabbiano, Orione (4), Pegaso II (16), PN I (36), and 30 more under construction.

Coastal TBs Type Schichau (about 10).

Submarines: Delfino, Glauco (6), Foca, Medusa (6), Atropo, Nautilus (2), Pullino (2), Alfa (2).

Gunboats: Guardiano, Brondolo (2), Caboto.

Miscellaneous: -Floating batteries, floating HQ (Cruiser Giovanni Bausan)

Tonnage 1914:

|

Additional tonnage 14-18:

|

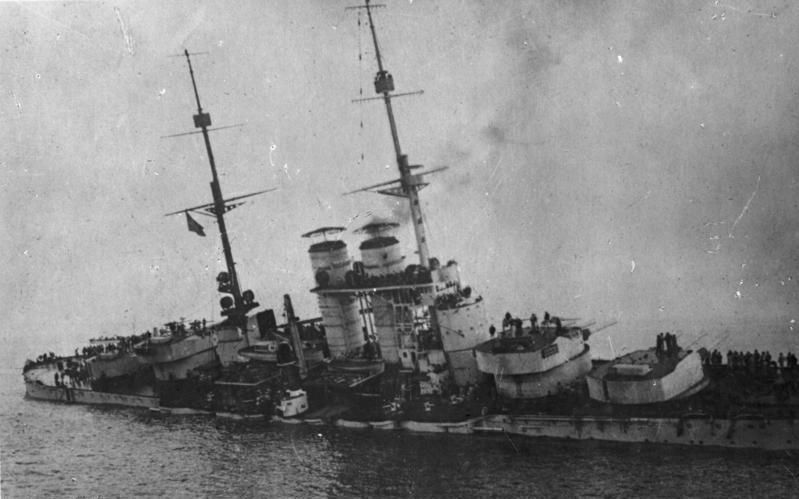

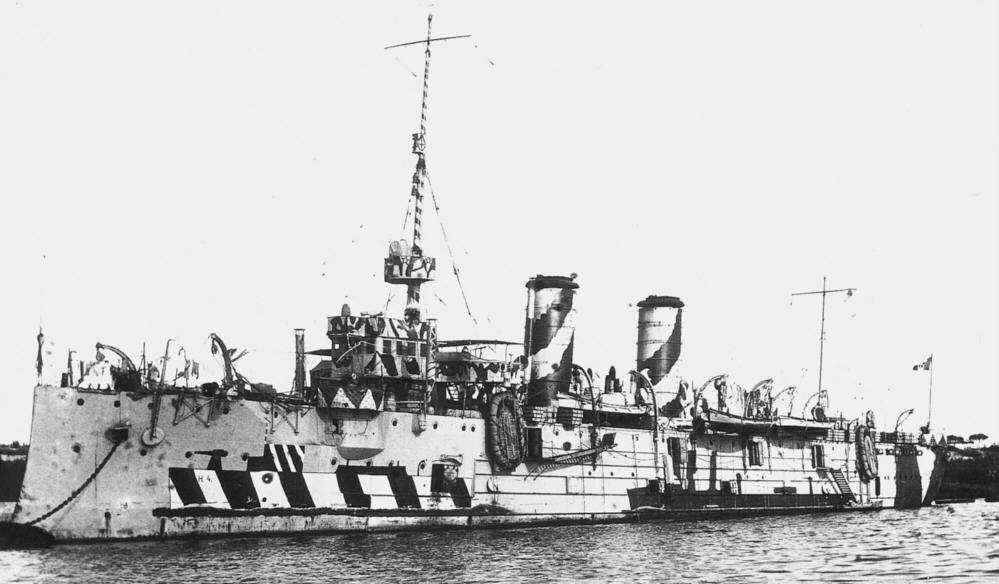

Its war production is characterized mainly by a large use of light units: destroyers, submersibles, coastal bombardment gunboats, but above all a real horde of MAS torpedo boats (Motoscafi Anti Somergibli), widely used as anti- Submersibles, which infested the Adriatic and offered themselves with impunity sumptuous pictures of hunting. These torpedo-launching units, famous with their powerful engines, their light construction, added to the individual audacity, did wonder.

Battleships: -class Caio Duilio (2), 2 others under construction, class Caracciolo (never completed).

Cruisers: Light ships, scouts of the class Alessandro Poerio (3), Carlo Mirabello (3), Aquila (4), and at the end of the war, three others were started, class Leone. Too small as cruisers but well sized as destroyers, they are classified as such after the war.

Destroyers: class Pilo (8), Audace (ii), class Sirtori (4) class La Masa (10), others at the beginning of construction in 1918, class Palestro Class Curtatone (4).

Torpedo-boats: Coastal Type PN II and III (37).

Submarines: Class Provana (4), Class Micca (6), Argonauta, Class F (21), Class N (6), Class H (8), Class X (2).

Gunboats: 10 requisitioned or purchased (see “gunboats”), 4 others escort in project.

Miscellaneous: Dredgers of mines: Class RD (21 during the war, 30 others under construction)

-Monitors Alfredo Capellini, Faa’di Bruno, Montfalcone, Monte Cucco, Monte Santo (2), Vodice, Carso, Pasubio, Padus, and 4 Monte Grappa class yards.

-MAS torpedo torpedo boats (422 in all, more than 380 during the war).

-42 Auxiliary cruisers (armored steamers) of which 17 were sunk

-6 Armed yachts, 9 armed ones (Libya), Seaplane carrier Europa.

Italian Naval Ensign

The Regia Marina at war

Early Operations (1914-15):

The question deserves to be asked: What would have happened if Italy had definitely committed itself alongside the central empires? Indeed, in August 1914, his position was ambiguous. It had claims on the side of France (Nice, Savoy, Tunisia), but also on the side of its allied supposed neighbor, Austria-Hungary, for territories in the Alps and the Adriatic. When the Franco-British combined fleet entered the Adriatic, Admiral de Lapeyrere arranged to cross his fleet near the Italian coasts in order to act as a deterrent.

Colorized photo of the Caio Duilio, completed during the war

In terms of balance of forces, the involvement of the Italian navy alongside the Austro-Hungarian fleet was certainly difficult to manage for the allied forces present: Before the Dardanelles affair, the Royal Navy had on site only Of a handful of buildings (two battle cruisers, moreover quickly solicited in the Von Spee hunt in the Atlantic, and two cruisers-battleships, but not a single ship of line, even old). The French navy was entrusted with the command of naval operations in the Mediterranean, the Royal Navy reserving for itself the North Sea.

The weight of the Italian navy was numerically inferior to that of the French navy, but in 1915 the two combined fleets (Italy and Austria-Hungary) would have had 9 dreadnoughts as against 7 for the French, and there was no The possibility of the Royal Navy separating itself immediately from one of its precious dreadnoughts (which it did however by sending the Queen Elizabeth to the Dardanelles in 1915). In the case of “classical” battleships, the two fleets would have aligned 22 units against 23 for the French. As for cruisers finally, they would have aligned 35 against 36 to France.

Cruiser Libia

As we can see, the forces were comparable, and the former had the disadvantage of having to coordinate their actions. However, this question was settled by a secret treaty concluded in London between the triple agreement and Italy on 26 April 1915. The latter offered to Italy in exchange for its engagement alongside the allies of the territories in the Adriatic and the Balkans, Taken to Austria-Hungary and Turkey.

President of the council Antonio Salandra had rather neutral views as the majority of the population, despite the demonstrations of nationalists carried by the poet Gabriel d’Annunzio, or Mussolini who militate to take back the “irreverent lands”. The secret treaty comes to the public at the same time as a denunciation of the triple entente on May 3 and Salandra saw his government overthrown by the parliament.

Battleship Vitorrio Emanuele

King Victor-Emmanuel, favorable to the war, recalled him. On May 24, 1915, Italy committed itself definitively by declaring war on Austria-Hungary. The navy was then largely involved during the conflict against an enemy located on the eastern coast of the Adriatic, which conducted limited operations due to its manifest numerical inferiority. There was never a real battle between the two fleets, except skirmishes and some punctual clashes, as well as isolated actions by individuals and small crafts but of spectacular results.

In the absence of a decisive confrontation, the Italian admiralty fell on submersibles and small crafts, especially relying on light units of the MAS type, of which they made considerable use. The mine warfare was also a priority, and the many “RD” type are there to testify of its importance. Numerous attempts were made to force Pola harbour.

Battleship Szent István sinking after a MAS attack

Late operations 1916-18

The project of blasting the Habsburg fleet was a veritable manifesto of individual bravery and recklessness. Passing by in particular the heavy nets of steel mesh through the passes required the construction of singular machines like the tracked “Grillo”, a kind of equivalent naval response to the problem of barbed wire for the infantry, which led to tanks. By virtue, the were also the first amphibious “tanks” used in action, although they should be more assimilated to boats. See “boats or tanks? -The Grillo machines”

Italian MAS BMTs at sea. Their successes led to more constructions in ww2.

Finally, the Italian navy made great use of “monitors”, especially at the end of the war. Some of them were real battleships, such as Faà di Bruno, equipped with the Carracciolo cannons (after its construction has been halted), others were simple pontoons, or barges, equipped with heavy artillery. They bombed coastal installations but also supported the Italian troops on the front line, near the coast.

Italian Naval Aviation

-Macchi L.1/2 – biplane flying boat (1915-16)

-Macchi M.3 – two/three-seat flying boat (1916)

-Caproni Ca.39/43 – prototype bomber floatplane (1917)

-Caproni Ca.47 – bomber floatplane (late 1917)

-Macchi M.4 – flying boat (1917)

-Macchi M.5/6 – fighter flying boat (1917)

-SIAI S.8 – two-seat reconnaissance flying boat (1917)

-Macchi M.7 – fighter flying boat (1918)

-Macchi M.8/9/12 – reconnaissance/bomber flying boat (1917-18)

-SIAI S.9 – reconnaissance flying boat (1918)

-SIAI S.12 – reconnaissance bomber flying boat (1918)

links/sources

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regia_Marina”

Italian Naval warfare 1915-18

Naval deployment 1914-15

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_warfare_in_the_Mediterranean_during_World_War_I Naval warfare in the mediterranean

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_battleships_of_Italy List of Italian battleships

Marine Italienne Archives

http://www.hisutton.com/Mignatta.html

Conway’s All warships of the world 1860-1905 and 1906-1922.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign