Germany – SMS Wiesbaden, SMS Frankfurt (1914-1919)

Germany – SMS Wiesbaden, SMS Frankfurt (1914-1919)WW1 German Cruisers

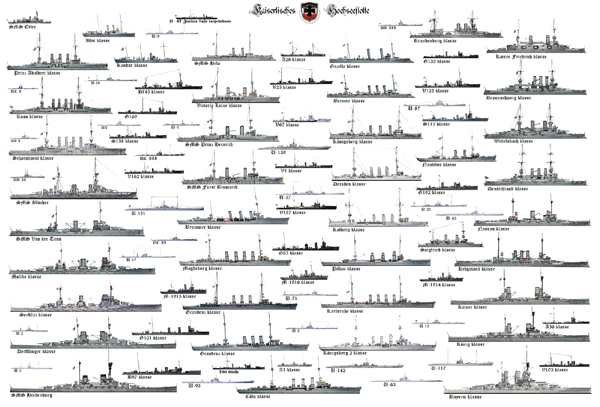

Irene class | SMS Gefion | SMS Hela | SMS Kaiserin Augusta | Victoria Louise class | Prinz Adalbert class | SMS Prinz Heinrich | SMS Fürst Bismarck | Roon class | Scharnhorst class | SMS BlücherBussard class | Gazelle class | Bremen class | Kolberg class | Königsberg class | Nautilus class | Magdeburg class | Dresden class | Graudenz class | Karlsruhe class | Pillau class | Wiesbaden class | Karlsruhe class | Brummer class | Königsberg ii class | Cöln class

Hipper’s Cavalry:

Among the light cruisers screening for the Kaiserliches Marine, were the modern and active SMS Wiesbaden and Frankfurt: They were screening Admiral Franz Hipper’s battlecruisers (1st scouting group) in early sorties and fought notably at Jutland. Very similar to the previous Graudenz class, but up-armed with 15 cm SK L/45 guns and capable of 27.5 knots. Wiesbaden’s career ended at Jutland, badly damaged and eventually sank in the early morning hours while Frankfurt was only lightly damaged and went on with the II Scouting Group in Operation Albion and Second Battle of Heligoland Bight in 1917.

Development of the Wiesbaden class

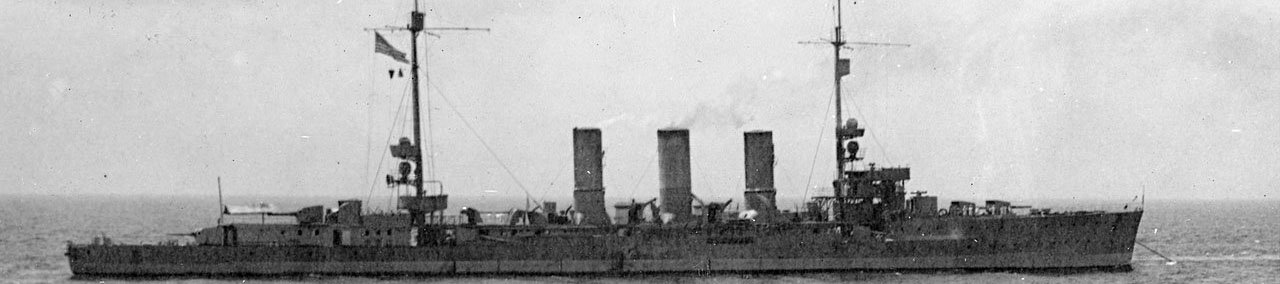

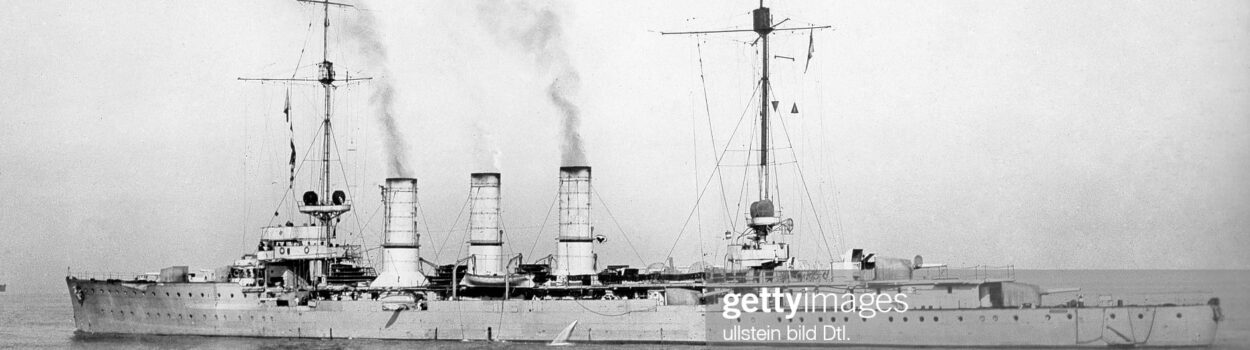

SMS Frankfurt in Scapa Flow, 1919

Technically these cruisers were just an incremental step in light cruiser design. Planned in 1912 as part of the naval program, as improved Graudenz class, only two were built, laid down in 1913. They were very similar but armed with eight 15 cm SK L/45 guns instead of the twelve 10.5 cm SK L/45 guns on the earlier cruisers, a radical firepower upgrade that was a result of recent evaluation and tactical use as screening vessels. It went from “destroyer killers” to “cruisers killers”. Ie. their role went to chasing out enemy’s own flotillas, generally led by light cruisers, to combat their opposite screening forces, which cruisers the time were all armed with 6-in guns, like the prolific “Town” class.

And apart a reviewed protection for better standing 6-in shells damage (they could not be stopped anyway), it was joined with a better speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) to also give them a fair advantage and the ability to out-run their enemy and choose their distance of engagement. This was especially true for the Hochseeflotte which planned them to serve on the north sea, which vibility was poor most of the time, between bad weather and fog. The Royal Navy when designing their cruisers were less specific about the theater of operation due to the needs of their large empire and numerous trade routes.

SMS Wiesbaden was ordered under the contract name “Ersatz Gefion”. She was laid down at AG Vulcan shipyard, Stettin, in 1913. She was launched on 20 January 1915 and fitting-out work started. Her sister Frankfurt was ordered under “Ersatz Hela”, laid down at the Kaiserliche Werft, Kiel, also in 1913, launched later on 20 March 1915 but fitting-out work proved faster and she was completed earlier.

Construction was relatively long, delayed due to other more priority works after the war broke out. But they were eventually launched on January and March 1915, and completed in August 1915, Frankfurt ten days before her sister ship. The class is still named in most publications after the led ship launched. Completion and fitting out work was very short in order to have both pressed into service as soon as possible. In between the Graudenz and Wiesbaden built at Vulkan and Kiel, little experience could be integrated from cruisers classes built in between: The Pillau were Russian designed ships, requisitioned and modified, and the Brummer were minelayers.

Design of the Wiesbaden class

SMS Frankfurt seen from profile

If taking of the previous Graudenz class as reference (both were launched in 1913 and 1914); the new Wiesbaden were a bit larger, perhaps 300 tonnes more in displacement fully loaded, a few meters longer (145.3m/476 ft versus 142.7m/468 ft overall), just 10 cm (4 in) wider, but they generally shared a similar design and outlook, with two equal masts fore and aft, three raked funnels of equal size and span, a forecastle, a bulwark covered amidship section and a lower aft deck, clipper bow and round stern.

In many way they confirmed the design standard repeated for the next wartime Königsberg (ii) -four ships- and the final Cöln class flirting with 7,500 tonnes (11 ships planned, two completed too late to see action). They could be seen as well as the forebears of the interwar KMS Emden, first “modern” german cruiser.

Hull and general design

The hull followed the usual scheme of longitudinal steel frames. Their crew comprised 17 officers and 457 enlisted men, a bit less than the previous Graudenz which had more guns (albeit of a smaller caliber), so they felt roomy. They carried for service boats a single steam picket boat, a supply barge, a cutter, two yawls and two dinghies, man-rowed but with optional sail.

Apart changes in armament, the new cruisers had a bit more power, but their simhouette remained the same. The bridge was separated entirely from the forward conning tower, on which was installed the main telemeter. The enclosedd winter deck with wings was topped by the open battle deck with lookouts and signals post. The two equal masts were composed of two parts, the lower being thicker and supporting a lightly armored observation post. Contrary to the Graudenz, there were equal fore and aft, covering the observer from the elements and from shrapnels.

The central section, about 1/3 lenght was dotted by the three funnels, truncated from all the pipes, with ventilation louvres on uptakes fore and aft of these. Two flak guns (8.8 cm) were installed either side of the middle funnel. Six service boats were fitted under davits on the sides and extra space was allocated aft of the third funnel, at the foot of the aft mast. The latter also supported a watch platform, a small radio room, and aft main telemeter for the two superfiring guns. Four night projectors were located on invidual platforms on each mast, one over the other, covering the front and back.

Powerplant

SMS Wiesbaden engraving (postcard) – pinterest

The Wiesbaden class propulsion systems consisted of two sets of Marine steam turbines. Each drove a single three-bladed 3.5-meter (11 ft) screw propeller. In total, ten coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers and two oil-fired double-ended boilers provided an output of 31,000 shaft horsepower (23,000 kW). Top speed as designed was 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). Sea trials speeds are not known, but generally superior to those planned on German cruisers.

For range, they carried 1,280 metric tons of coal plus an additional 470 metric tons of oil making for a total of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 12 knots cruise speed. At 25 knots as tested (46 km/h; 29 mph) it was down to to 1,200 nmi (2,200 km; 1,400 mi). Wiesbaden and Frankfurt each had a pair of turbo generators, but only the first had an extra diesel generator, rated for 300 kilowatts (400 hp) at 220 Volts. SMS Frankfurt reached only 240 kW (320 hp) however she also differed by having a hydraulic drive on one shaft, and geared cruising turbine on the other as an experiment. Steering on both vessels was controlled by a single rudder and they were considered good steamers and responsive at the helm, good weapons platform with a moderately slow and predictable roll.

Armament

Main Guns: 8x 15cm SKL/45

The Wiesbaden class made their greatest changed compared to all previous cruisers (and it was time!) by replacing the usual 10.5 cm (4 in) battery by a far more potent main battery of eight 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns, all also in single pedestal mounts with different locations:

-Two were placed side by side (tandem) forward on the forecastle

-Four located amidships, two per side

-Two were placed in a superfiring pair aft.

The SK L/45 became the mainstay of secondary armament on battleships and cruisers in the German Navy. It was studied from 1906, introduced first in capital ships like the Kaiser and König class, but the Wiesbaden were the first to introduce these. They were also used by subsequent vessels of the Pillau, Brummer, Königsberg (II), Dresden (II) classes, and KMS Emden in the 1920s, spared later being used on the many auxiliary cruisers seeing action in WW2, notably KMS Atlantis against Sydney. Many cruisers were also rearmed in 1915-16 with these guns.

These guns fire an HE or AP shell both 99.8 lbs. (45.3 kg), with a rate of fire of about 5-7 rounds per minute, and range of 17,600 m (19,200 yd). In total 1,024 rounds of ammunition was aboard, so for 128 shells per gun. More on navweaps

Main Guns: 4x 5.2cm SKL/55

Since the design was studied in 1913, antiaircraft armament was planned from the start, and comprised four 5.2 cm (2 in) L/55 guns. They were located amidship, abaft the third funnel, but later replaced with just two 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns with high-angle mountings.

Torpedo Tubes: 4x 50cm Torpedoes

As previous cruisers, the new cruisers carried torpedo tubes, four 50 cm (19.7 in) two submerged braodside, two on the upper deck, with eight torpedoes in store. The Wiesbaden class was also design to be able to carry mines, 120 of them stored on the deck rails running aft.

Protection

SMS Wiesbaden and Frankfurt had the following:

-Waterline armored belt 60 mm (2.4 in) thick amidships.

-Forward belt tapeered down to 18 mm (0.71 in).

-No stern belt.

-Forward Conning tower 100 mm (3.9 in) walls, 20 mm (0.79 in) thick roof.

-Rangefinder atop 30 mm (1.2 in) armor protection.

-Main armored deck 60 mm thick armor plate forward, 40 mm (1.6 in) amidships, 20 mm aft.

-Sloped armor 40 mm thick, connecting deck to belt armor.

-Main battery gun shields 50 mm (2 in) thick.

-Seventeen watertight compartments

-Double bottom 47% keel lenght.

Wiesbaden class, old illustration by the author

⚙ Wiesbaden class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 145.30 m (476 ft 8 in) x 13.90 m (45 ft 7 in) x 5.76 m (18 ft 11 in) |

| Displacement | 5,180 t normal, 6,601 t (6,497 long tons) FL |

| Crew | 17 officers + 457 ratings |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts geared steam turbines, 12 WT boilers, 31,000 hp (23,000 Kw). |

| Speed | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h, 31.6 mph) |

| Range | 4800 nm (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) @ 12 knots. |

| Armament | 8× 15cm (6-in) SK/45 (152 mm) SK, 2x 8,8 cm (1916), 4x 50cm TTs (19.7 in) |

| Protection | Belt: 60 mm (2.4 in), Deck: 60 mm, Conning tower: 100 mm (3.9 in) |

Links & Resources

Books

Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). “Germany”. In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.) Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1906–1921.

Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. NIS

Herwig, Holger (1980). “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Humanity Books.

Miller, Roger G. (2009). Billy Mitchell: Stormy Petrel of the Air. Office of Air Force History.

Staff, Gary (2008). Battle for the Baltic Islands. Pen & Sword Maritime.

Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks.

Woodward, David (1973). The Collapse of Power: Mutiny in the High Seas Fleet. Arthur Barker Ltd.

The Kaiser’s Cruisers, 1871–1918 By Aidan Dodson, Dirk Nottelmann

Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Seaforth Publishing.

Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2004). Kleine Kreuzer 1903–1918 Bremen bis Cöln-Klasse, Bernard & Graefe Verlag

Links

Model at the Hamburg Museum (facebook)

On wrecksite.eu

The Kaiser’s Cruisers, 1871–1918 By Aidan Dodson, Dirk Nottelmann

On dreadnoughtproject.org

On historyofwar.org

Extra CC photos

On worldwar1.co.uk

On militaer-wissen.de

Model kit review Kombrig 1:700 nntmodell.com

SMS Wiesbaden

SMS Wiesbaden

SMS Wiesbaden was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet, on 23 August 1915, while her sea trials were rushed out (perhaps why nio data is available for test speeds). Her career in the winter was spent with uneventful patrols and training sorties as part of the II Scouting Group (also Lebing, Königsberg and her sister ship). The latter on 24 April 1916 had her taking part in Raid of Lowestoft at last. But only her sister saw some action, not her. As part of the screened force she did not have the occasion to fire one shot apart on Yarmouth and Lowestoft, but damage was light; The operation had been almost a complete failure as just two patrol craft were sunk, in exchange of a badly damaged battlecruiser. But her real test came with the spring of 1916.

Under Command of Kapitan zür zee Fritz Reiss, SMS Wiesbaden was still assigned to II Scouting Group, headed by Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedicker and operating alongside the I scouting group as the forward screening force, departing on 30 May with Hipper’s battlecruisers. Wiesbaden and Frankfurt served teamed together, her sister as Boedicker’s flagship. She was cruising to starboard on the formation, on the disengaged side when Elbing, Pillau, and Frankfurt engaged the British screen.

Circa 18:30, SMS Wiesbaden spotted and fired on the cruiser HMS Chester, scoring several hits, but both sides disengaged, spotting Rear Admiral Horace Hood’s battlecruisers. HMS Invincible fired on Wiesbaden and managed to land a lucky hit, penetrating the unprotected aft deck and exploding in her engine room. The damage was so extensive the cruiser bled speed to a crewl, while Konteradmiral Paul Behncke ordered his dreadnoughts Wiesbaden, in a vain hope the crew could repair the damage.

But at the same time, the British 3rd and 4th Light Cruiser Squadrons closed earlier to make a massive torpedo attack on the German line, while shelling Wiesbaden with their main guns at the same time. Then, the destroyer HMS Onslow closed within 2,000 yards (1,800 m), firing a single torpedo with sure results on a siotting duck. Hit below the conning tower forward, the hull shook violently, but thanks in part due to the compartimentation, she still remained afloat. The melee which followed was absolutely chaotic and fierce, with the crew of Wiesbaden right in the middle of the storm, witnessing fire from all sides. They saw the armored cruiser HMS Defence blew up, HMS Warrior fatally damaged. The German cruiser’s captain decided to launch her torpedoes in this, and managed to score against the battleship HMS Marlborough.

Shortly after 20:00, the German III Flotilla of torpedo boats attempted, not to defend, but just to evacuate her crew. They were pushed back by a dense fire from the British battle line. Another attempt was made but in the darknes they could not spot the stranded cruiser. Eventually she was left to her fate. Wiesbaden sank without witness at circa 01:45 up to 02:45. One crew member survived though, picked up by a Norwegian steamer on 1st June. The whple crew of 589 disapperaed behind the waves, probably surviving for some time swimming for some, but never found. Among these was the well-known poet and essayist Johann Kinau, aka “Gorch Fock”. Her wreck was found in 1983 by divers of the German Navy. The screws were salvaged and she was classed as a war grave, found lying upside down, the last vessel of the battle to be discovered.

SMS Frankfurt

SMS Frankfurt

SMS Frankfurt was commissioned on 20 August 1915 and like her sister ship due to the war, she rushed out her sea trials, being assigned to the II. scouting group.

Raid on Lowestoft

After months of training she took part at last in her first operation, the Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft, on 24 April 1916. As part of the screen of the I Scouting Group (Franz Von Hipper’s battlecruisers) and under command of Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedicker she spotted, attacked and sank a British armed patrol boat off the coast during the bombardment. Reports of submarines and torpedo attacks had Boedicker breaking off and ordered to sail full speed back east, towards the High Seas Fleet awaiting further away to destroy any chasing British force. Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, C-in-C, was warned of the Grand Fleet rushing out of Scapa Flow in hot pursuit and ordered a general withdrawal.

Jutland

Next action was not long to follow, still in the same unit with her sister she sailed on 31 May, as Boedicker’s flagship, II Scouting Group commander, screening for Hipper’s I Scouting Group. Frankfurt spotted their British’s screening counterpart and opened fire, with the battlecruiser squadrons closing fast behind. Frankfurt, Pillau, and Elbing were on the right side of the engagement and duelled with British light cruisers at 16:17, until the British, having many hits, folded away. But 30 min. later the 5th Battle Squadron’s fast battleships arrived and started to fire at SMS Frankfurt, which fled under a smokescreen, unscaved.

At around 18:00, the destroyers HMS Onslow and Moresby found and attacked the German battlecruisers, but were repelled by Frankfurt and Pillau. 30 min. later, Frankfurt spotted and engaged the cruiser HMS Chester, scoring several hits. Rear Admiral Horace Hood battlecruisers in turn arrived on the scene, opened fore and hit her sister Wiesbaden, disabled and later left behind. About 19:30 as darkness fell, HMS Canterbury scored four hits on Frankfurt, two 6-in around her mainmast and two 4-in forward above the waterline, and near the stern, damaging both screws.

Frankfurt and Pillau spotted HMS Castor and several destroyers at about 23:00 and fired each a torpedo at the cruiser before folding on the German line, searchlights shut not to be spotted. It was past well past midnight when Frankfurt met two British destroyers at close range, firing on them briefly and retreated; At around 04:00, 1 June, the entire fleet had managed to reach Horns Reef and Frankfurt had “only” three men killed and eighteen wounded, having fired 379 rounds or her main guns, some of her 8.8 cm guns and a single torpedo. Her captain found himself lucky to have escaped the fate of her sister ship.

Operation Albion and Heligoland

Next was Operation Albion, in October 1917. The goal was to drive off the Russian naval forces of the Gulf of Riga. Still in the II Scouting Group under command of RADM Ludwig von Reuter, she did her share of the action but did not fired a shot. In November, SMS Frankfurt and the II Scouting Group took part in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight. With the three other cruisers of her unit she escorted the minesweepers clearing paths in British minefields around the contested island.

SMS Kaiser and Kaiserin were in distant support in case of need, and during the British attack, Frankfurt fired torpedoes at incoming British cruisers, but missed. The British eventually broke off as German battleships came to the rescue. All withdrew soon after.

On 21 October 1918 in the evening, SMS Frankfurt accidentally rammed UB-89 in Kiel-Holtenau. The schock not only sunk the submarine, it also killing seven of her crew but 27 survivors were still pulled from the water. UB-89 was would be later raised by the salvage vessel Cyclop on 30 October but never repaired.

Later career and end as a target ship

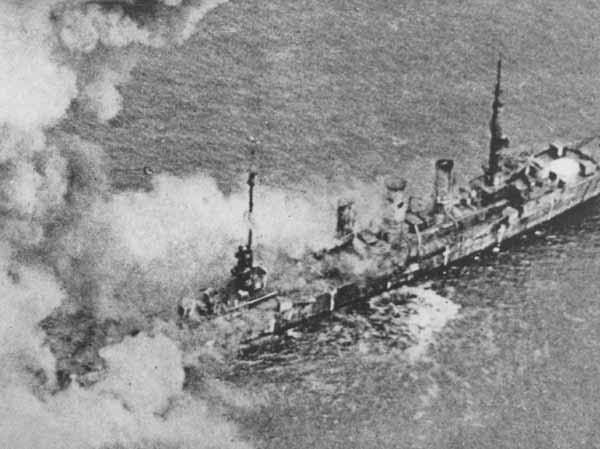

18 July 1921 US coast air attack test: Frankfurt is bombed.

Frabkfurth is burning

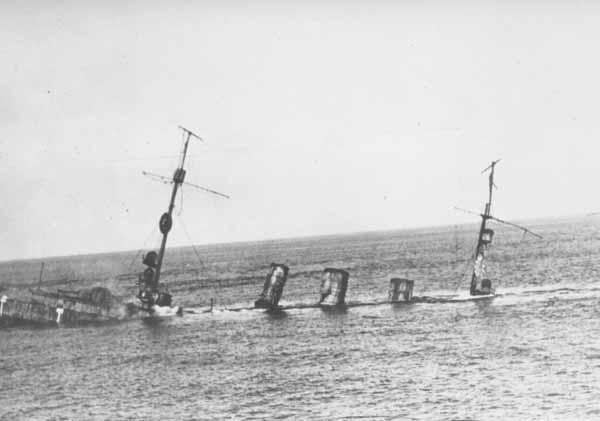

Sinking.

Scheer and Hipper had the project of a last massive sortie with the while fleet “for honor” after months of inaction, and trying to gain a better bargaining position for Germany in the peace treaty. On 29 October 1918, Frankfurt’s captain was ordered to sail to Wilhelmshaven but miutinies during the night of the 29-30 and further unrest during teh day forced Hipper to cancel the operation. Frankfurt was later summoned by the treaty’s condition to be interned in in Scapa Flow under overall command of Admiral Reuter.

While negotiations went on, she as prepared for scuttling and on 21 June 1919, as Reuter believed the deadline was about to end for the allied seizure of the fleet, he waited for an opportunity, which presented itself on 21 June when the Grand fleet left Scapa Flow for maneuvers. Ar 11:20 order to scuttle the ships was given. However Frankfurt was close to the coast and was swiflty boarded by British sailors when what happened was now obvious, and under gunpoint, even after the cocks were opened, they managed to have the ship beached before sinking. Raised in July, she was transferred to the USN as war prize.

From 11 March 1920 she was taken over, and then recommissioned on 4 June 1920, still in Britain. Instead of repairing her damage for subsequent service it was decided to have her “spent” as a target for experiments. She was taken in tow by the minesweepers USS Redwing, Rail, and Falcon to Brest, France, together with the battleship SMS Ostfriesland also a war prize. The three minesweepers towed three ex-German torpedo boats for good measure, creating a nice “target flotilla” which was not dealt on situ but rather escorted in convoy across the Atlantic to NYC Navy Yard. Inspection by naval engineers was long and exhaustive in order to gain lessons to apply to US ship design.

Her watertight compartments were completely sealed in order to have her survive extensive damage and on July 1921, the US Army Air Service and US Navy conducted bombing tests off Cape Henry in Virginia. They were at the initiative of WW1 ace and war hero, now General Billy Mitchell, to convince the Navy of the potenty of naval aviation and the threat it posed to traditional fleets. The “target fleet” was buffed up further by the adition of the old, stricken 1890s battleship USS Iowa. Tests started on 18 July with air attacks performed at first with small 250-pound (110 kg) and 300 lb (140 kg) bombs. Damage was minimal, then tests started with 550 lb (250 kg) and then 600 lb (270 kg) bombs using Martin MB-2 bombers. Frankfurt took several 600 lb bombs and sank that day at 18:25.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Theodore Johann Heinrich Verhaaren was on the Wiesbaden . He did not go down with the ship. He is my great grandfather. What dates did he serve? Where can I find more information about his service .