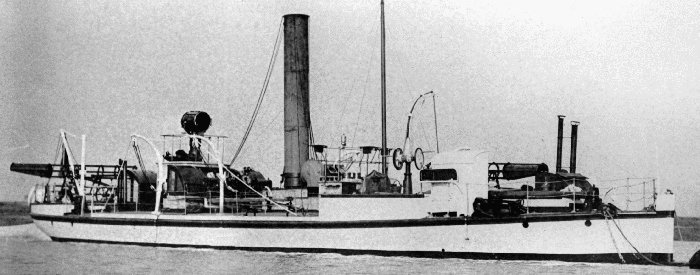

HMS Vesuvius was an experimental torpedo-armed warship in service with the British Royal Navy, built at Pembroke Dockyard in 1873 and the first purpose-designed torpedo vessel built ever in Britain. Intended for night attacks against ships anchored in ports, she was armed with a single, fixed bow tube for the earliest model of Whitehead torpedo. Used for experimental duties and training, she was only disposed of in 1923. She was the forerunner to later experiments with torpedo cruisers and then proper torpedo boats which development started in 1879. HMS Vesuvius is often confounded with the far more popular USS Vesuvius, also experimental, and only pneumatic gun cruiser ever seeing action (in 1898).

Next stop, the even more outlandish HMS Polyphemus.

no cc photos, credits bevs.org

Development

The idea of the Vesuvius was really not to lost track of a potential game-changing, brand-new weapon, created in Austria-Hungary in the hands of a British engineer: The Torpedo. However, it could trace its root to a Croat officer of the Austro-Hungarian Navy (Biagio Luppis Freiherr von Rammer) which in 1850 imagined the concept of the “Salvacoste”, a contact-detonated, floating explosive device, unmanned, and controlled from land.

He made several demonstrations and improved its model, but Emperor Franz Joseph and his commission rejected it.

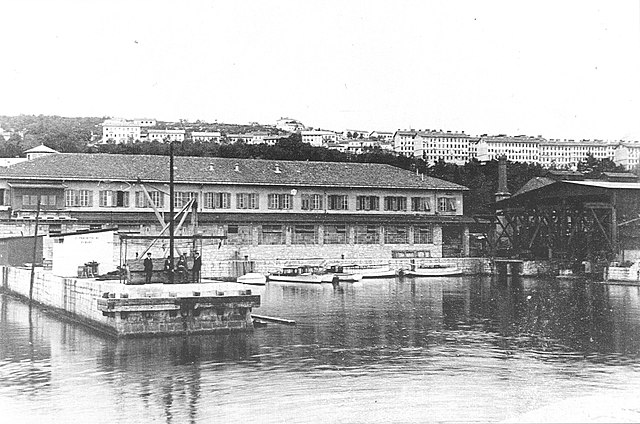

Next, Robert Whitehead (1823-1905) created the “Stabilimento Tecnico Fiumano” in a small Fiume factory. It produced steam boilers and engines for the Austrian Navy. In 1863, Whitehead met Giovanni Luppis, just retired in Trieste at the end of life and feeling dejected. Robert saw the potential and instead of a clock mechanism devised a steam engine small enough to fit in, adding also a compressed air tank. The cable was eliminated and distance increased. The two men entered partnership, however disagreement rose as Robert continued improving on the model, leading to something else entirely. His last prototype was called the Minenschiff, and it was the first true self-propelled or locomotive torpedo.

Next, Robert Whitehead (1823-1905) created the “Stabilimento Tecnico Fiumano” in a small Fiume factory. It produced steam boilers and engines for the Austrian Navy. In 1863, Whitehead met Giovanni Luppis, just retired in Trieste at the end of life and feeling dejected. Robert saw the potential and instead of a clock mechanism devised a steam engine small enough to fit in, adding also a compressed air tank. The cable was eliminated and distance increased. The two men entered partnership, however disagreement rose as Robert continued improving on the model, leading to something else entirely. His last prototype was called the Minenschiff, and it was the first true self-propelled or locomotive torpedo.

It was presented in 1866 to the Austrian Imperial Naval commission on 21 December 1866. It worked flawlessly and the commission purchasing prototypes for the gunboat SMS Gemse from Schiavon shipyard. Whitehead patented the launching barrel that went with it, working with compressed air, inventing the torpedo tube.

The torpedo seemingly was for the young Austro-Hungarian Empire, pitted against an equally young Italian unified Kingdom, the ideal “secret weapon” as until the battle of Lissa the same year, albeit being a victory, showed the numerical inferiority of the K.u.K. Kriegsmarine.

No less than 50 launches were performed at STT in 1967-68, and two years later in 1870 Whitehead patented his first Torpedo, declared ready for service. It was capable of 7 knots (13 km/h) and could reach 700 yards (640 m), as well as powered by a small reciprocating engine, run by compressed air. Now, all this time these developments were followed closely by the British embassy and naval attaché. The RN had interests in the Mediterranean, spread between Gibraltar, Malta and Alexandria, and was concerned that a foreign power could enter such of these ports with a small vessel carrying one of these “locomotive mines” and create havoc. The sells of this new weapon were closely followed, albeit being a private company in a foreign country, Downing street tried to pressure Whitehead to come back home and setup a facility there.

From 1864, already Robert Whitehead’s Fiume tests were known and in 1868, he solved the problem of depth control, which really sparked more than curiosity but the desire to test the new weapon at the admiralty. One was purchased as it was, still not patented or ready for service, and the prototype was trialled from the sloop HMS Oberon in September–October 1868. This was successful enough or the Admiralty to purchase a licence to build these at the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich in London, setup in 1872.

It was done apparently without the presence of Whitehead. On 12 February 1872, the first was ready for tests, and the Admiralty placed an order for a first dedicated ship that could perform torpedo attack. This new boat was named HMS Vesuvius after the famous Sicilian volcano, associated at the time to explosivity. The specifications were quite strict. The new boat was intended for night attacks against enemy harbours and especially France, Toulon, where the bulk of the Marine Nationale was stationed. But it was handy for attacks on Brest as well, provided it could cope with the choppy waters and strong currents of the channel.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

Vesuvius measured 90 feet (27.43 m) long between perpendiculars, around 91 overall, had a beam of 22 feet (6.71 m) draft of 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m). Her displacement was 382 long tons (388 t) at normal load. Her freeboard was low to make her ore difficult to spot. However, her superstructure was still extensive. She had a single funnel, a bridge forward with a spotting platform, single mast, bulwarks, accesses to the lower hull and aft platform with a searchlight. She also had two vents close to the funnel. There were two torpedo tube located forward and at the stern, with some traverse.

Powerplant

HMS Vesuvius was powered by two 2-cylinder compound steam engines, rated at 382 indicated horsepower (285 kW), driving two 4-bladed propeller shafts for a top speed of 9.7 knots (11.2 mph; 18.0 km/h). Her engines were already designed to be as silent as possible for these stealthy attacks. The boilers were fuelled by coke which avoided the production of smoke, and could be vented underwater for the night attack. There was a large searchlight installed on a platform aft to illuminate the target just before launch. She was however short ranged, carrying 25t of coke for perhaps 200 nm at best.

Armament

It was reduced by all means at first to a single torpedo tube. It was 16 inches in diameter, and submerged in the bow, created a protrusion. The torpedo tube was 19 feet (5.8 m) long, 2 feet (0.6 m) in diameter. The torpedo was loaded inside the hull, ran on rollers within the tube. A total of ten torpedoes were carried. They were early Whitehead type, 14 feet (4.3 m) long and topped by a significant warhead of 67 pounds (30 kg) of guncotton. Otherwise, the ship was devoid of any self-defence artillery. No guns were carried albeit the crew of 15 had regular ordnance on board (rifles and pistols).

She was however later rebuilt in the 1880s-90s and had one forward, one aft, more modern torpedo tubes. The forward was located port, and the aft one was axial. By then she was used to launching torpedoes at target ships for ASW defence experiments.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 245 long tons (249 t) |

| Dimensions | 90 x 22 x 8 ft 6 in (27.43 x 6.71 x 2.59 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts compound steam engines: 350 ihp (260 kW) |

| Speed | 9.7 knots (11.2 mph; 18.0 km/h) |

| Range | 25t coal, c200 nm |

| Armament | 1 × 16 inch torpedo tube |

| Crew | 15 |

Career of HMS Vesuvius

Vesuvius was laid down at Pembroke Dockyard, 16 March 1873. She was launched on 24 March 1874. Towed to Portsmouth Dockyard she was fitted and was given a taller funnel than initially planned to aid raising steam as calculations shown she would be slower than expected with the proposed design. This was suggested by the yard. She was completed on 11 September 1874 at a cost of £17,897.

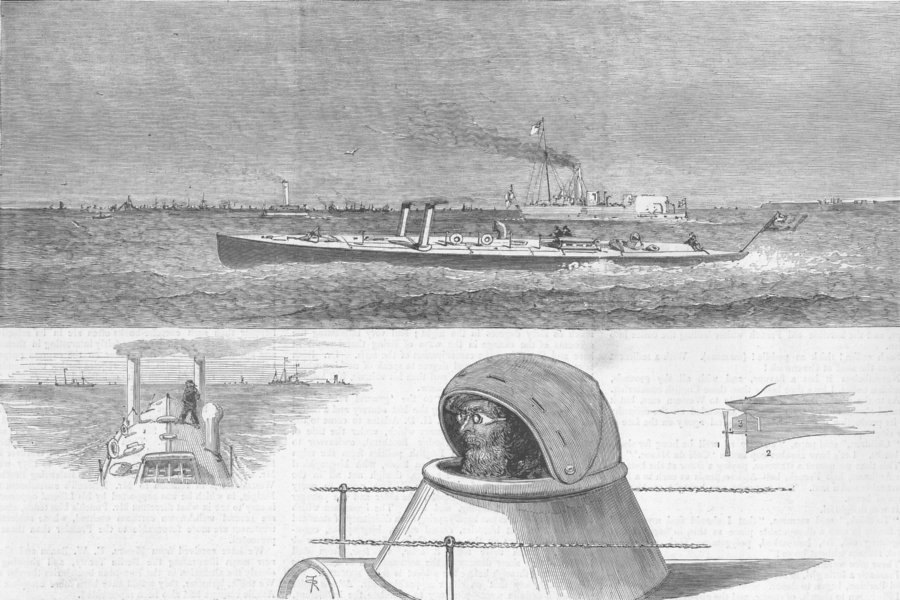

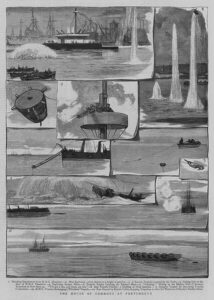

Vesuvius and Lightning, appeared at the Naval Review at Spithead in 1878. The Graphic

HMS Vesuvius first appearance was at the Naval Review at Spithead, in August 1878. The Queen noted in her journal she was impressed by her and the new Lightning, first “true” British TB. The later left vesuvious in her wake, racing at 20 Knots an hour. At the time, she was powered by loco boilers and standard VTE, so nothing came close to the sensation made by Turbinia in 1897.

The House of Commons at Portsmouth witnesses torpedo trials of Vesuvius, which were declared successful, succeeding those performed the previous years.

Contrast with HMS Lightning

As for HMS Lightning built a few years later, as the first true British TB, her design was very peculiar, as she was closer to a fast yacht in appearance with a clipper bow, pointy stern with sloping back keel, and a turtle back to deal with the elements. Superstructures were reduced to be bare minimum, with a pair of funnels forward, a vent, a hatch case, a short “conning tower” for the pilot, which was armoured, had a sliding cap and small slight slits when closed. There was also an open space behind. There was no mast either. The entire design was made to be as stealthy as possible. Modern denominations would have this boat named a “boat”, not a ship, as she carried no boat herself, only buoys. In fact, a smaller version could possibly fit onboard a mothership. These ideas became popular in the 1870s. There was a single, small rudder, and a single two-bladed propeller. The sloping down stern tail was apparently semi-fixed and could act as supplementary rudder on a limited angle, but the real rudder was unusually located aft over the shaft end, just before the propeller.

As for HMS Lightning built a few years later, as the first true British TB, her design was very peculiar, as she was closer to a fast yacht in appearance with a clipper bow, pointy stern with sloping back keel, and a turtle back to deal with the elements. Superstructures were reduced to be bare minimum, with a pair of funnels forward, a vent, a hatch case, a short “conning tower” for the pilot, which was armoured, had a sliding cap and small slight slits when closed. There was also an open space behind. There was no mast either. The entire design was made to be as stealthy as possible. Modern denominations would have this boat named a “boat”, not a ship, as she carried no boat herself, only buoys. In fact, a smaller version could possibly fit onboard a mothership. These ideas became popular in the 1870s. There was a single, small rudder, and a single two-bladed propeller. The sloping down stern tail was apparently semi-fixed and could act as supplementary rudder on a limited angle, but the real rudder was unusually located aft over the shaft end, just before the propeller.

HMS Vesuvius however was never seriously evaluated for harbour night torpedo attacks. It soon appeared that depite her tall funnel she was still too slow and short ranged to go with a blockading fleet. Thus, especially when new TBs were developed, she was relegated to experimental or training roles and permanently attached to HMS Vernon which becale the newly founded Royal Navy’s torpedo training school.

In 1886–1887, she was foubnd useful to test anti-torpedo nets, fitted on the old ironclad Resistance. None torpedo hit her and so it was concluded anti-torpedo nets were an effective protection and soon adopted by most capital ships in the RN despite their added weight. The specter of an harbour attack was indeed well present until WWI. It was confirmed in the 1880s, 90s and 1905 at Port Arthur.

Vesuvius remained attached to HMS Vernon at Portsmouth still in the First World War, to train torpeod crews with the latest models of torpedo tubes, and was sold for scrap on 14 September 1923 at the shipbreakers Cashmore. However she foundered under tow at Newport and is now a wreck of interest for divers.

Read More/Src

Books

Brassey, T. A., ed. (1895). The Naval Annual 1895. Portsmouth, UK: J Griffin and Co.

Brown, D. K. (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. London: Chatham Publishing.

Clowes, William Laird (1903). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Years to the Death of Queen Victoria: Volume VII. Sampson Low, Marston and Co.

Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006). ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy from the 15th Century to the Present. London: Chatham Publishing.

Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Dittmar, F. J.; Colledge, J. J. (1972). British Warships 1914–1919. Shepperton, UK: Ian Allan.

Friedman, Norman (2009). British Destroyers: From Earliest Days to the Second World War. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Gardiner, Robert; Lambert, Andrew, eds. (1992). Steam, Steel & Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. Conway’s History of the Ship. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Links

bevs.org/ wkvesuvi.htm

web.archive.org on navypedia.org/

HMS_Vesuvius_(1874)

Videos

None

Model Kits

None

3D

None

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign