Prussian Navy – Ironclad 1869-1921

Prussian Navy – Ironclad 1869-1921

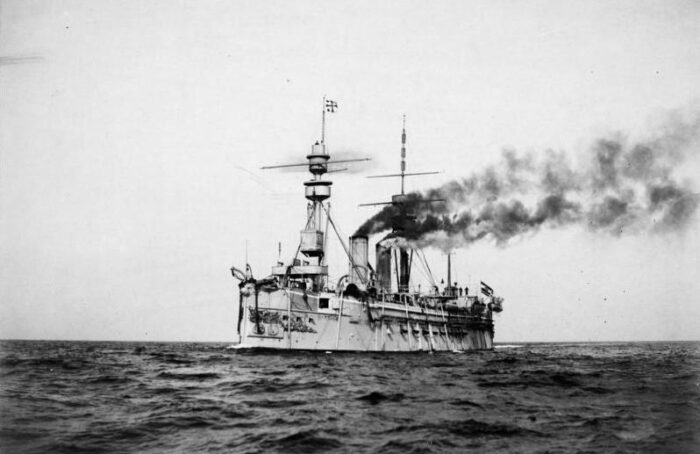

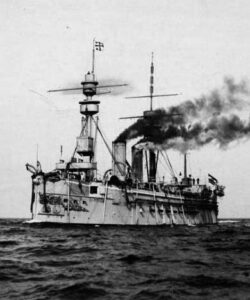

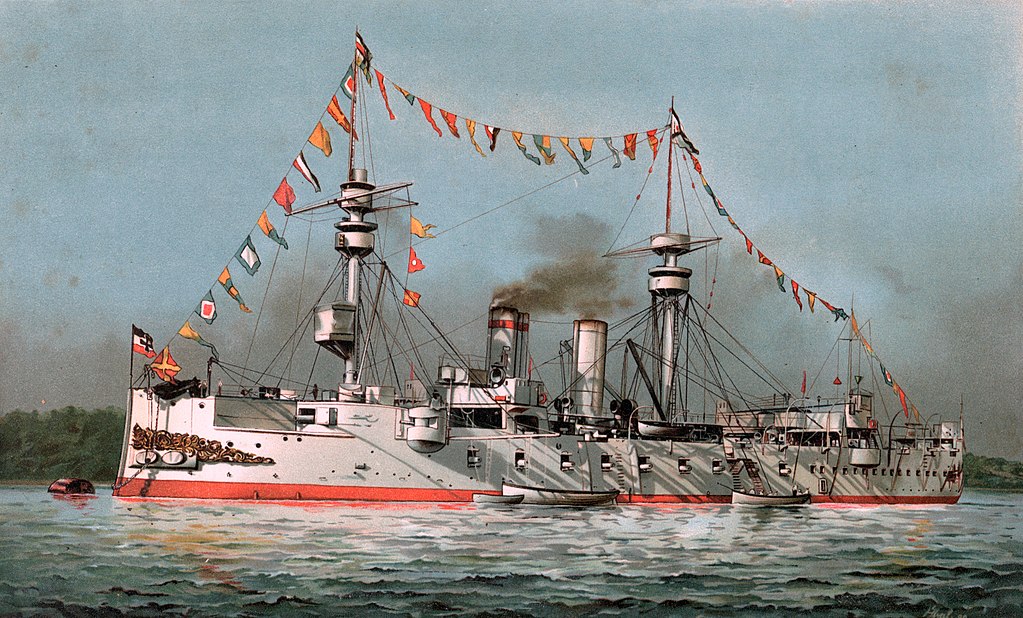

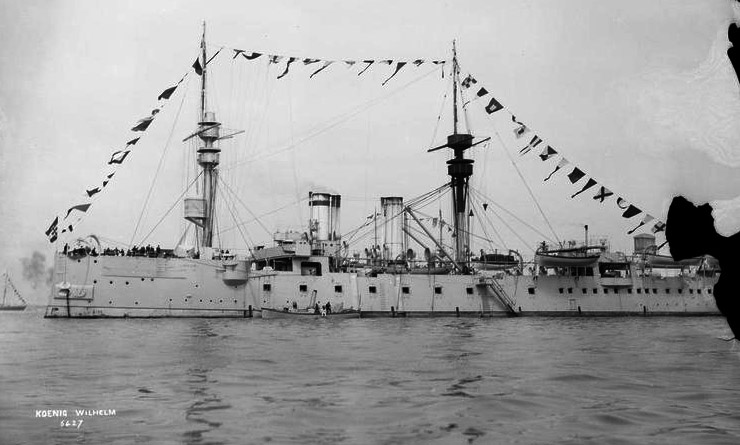

SMS König Wilhelm or “King William” was an armored frigate ordered by the Prussian Navy and later in service with the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliches Marine). She was ordered abroad, in Britain and laid down in 1865 at Thames Iron Works of London. Originaly she had been ordered by the Ottoman Empire at “Fatih” but was repurchased by Prussia in February 1867. She was launched in April 1868, commissioned into the Prussian Navy in February 1869 as its fifth ironclad, flagship and world’s largest warship. Armed with sixteen 24 cm (9.4 in), five 21 cm (8.3 in) she saw limited service in the Franco-Prussian War and in 1878 accidentally rammed and sank Grosser Kurfürst. Later in life she was completely rebuilt as an armored cruiser (1895–1896). From early 1904 she doubled as floating barracks and training ship until discarded and sold for BU in 1921 after 52 years under three states.

SMS König Wilhelm or “King William” was an armored frigate ordered by the Prussian Navy and later in service with the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliches Marine). She was ordered abroad, in Britain and laid down in 1865 at Thames Iron Works of London. Originaly she had been ordered by the Ottoman Empire at “Fatih” but was repurchased by Prussia in February 1867. She was launched in April 1868, commissioned into the Prussian Navy in February 1869 as its fifth ironclad, flagship and world’s largest warship. Armed with sixteen 24 cm (9.4 in), five 21 cm (8.3 in) she saw limited service in the Franco-Prussian War and in 1878 accidentally rammed and sank Grosser Kurfürst. Later in life she was completely rebuilt as an armored cruiser (1895–1896). From early 1904 she doubled as floating barracks and training ship until discarded and sold for BU in 1921 after 52 years under three states.

Development

What pecame late the “King William” was originally had been ordered by the Ottoman Empire. At that time, its greatest concern was the rising star of the Russian Black sea fleet and a war loomed real everyday. Ordered as “Fatih” from Thames Ironworks in London by 1865 she was designed by renown British naval architect Edward Reed. The Ottoman Navy wanted a ship powerful enough so that she could act as deterrence against the Russians, but other powers as well. And when laid down, based on her specs, she as regarded in the British press as the world’s most powerful vessel, 1,800 metric tons (1,800 long tons) larger than the HMS Hercules, and with a larger gun battery. In fact some questioned why she would be sold to a potential rival power at all.

However the Ottoman Navy at the time was the object of internal power politics and the whims of the Sultan. No budget came but empty promises, until the Yard pressured the government to find a solution. Eventually after many back and forth discussions it was clear the Ottoman Empire was unabile to pay for her. Again, the press as she was purchased and integrated to the Royal Navy, but as she never had been planned, the responsibility laid in the builder. The latter placed the still-incomplete ship for sale in 1866.

At the time the Kingdom of Prussia just came out of the humiliation of a Danish naval blockade over the war of Schleswig-Holstein between 1 February to 30 October 1864. On 17 March 1864 for example the Prussian army drove back Danish outposts in front of Dybbøl but was defeated at the naval Battle of Jasmund (Battle of Rügen) when trying to break the Danish naval blockade but was pushed back to Swinemünde. Austria sent a token naval force to help. So as soon as the war was over, Prussia realized its tiny fleet of wooden figates was not up to the task and the government embarked on a program to acquire sea-going ironclad warships. Ex-Condeferate ships were acquired and orders were placed to British and French shipyards in 1865. Fatih was the last of the five ironclads purchased, as the opportunity arose to obtain her from Thames Ironworks, now without customer.

Again, as soon as it was known she would be acquired by Prussia, there were concerns in the press, and when she entered service, now renamed SMS König Wilhelm, she became instantly the largest and most powerful vessel, not only in the Prussian fleet, but of the whole Baltic. She became its flagship, and remained the largest German vessel until… 1891 and the lauch of the four Brandenburg-class battleships, signalling the rise of the Kaiserliches Marine.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

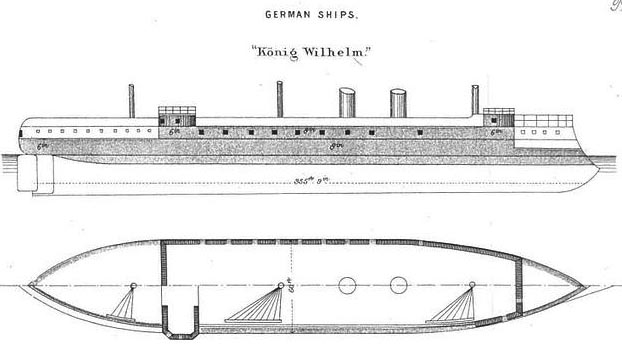

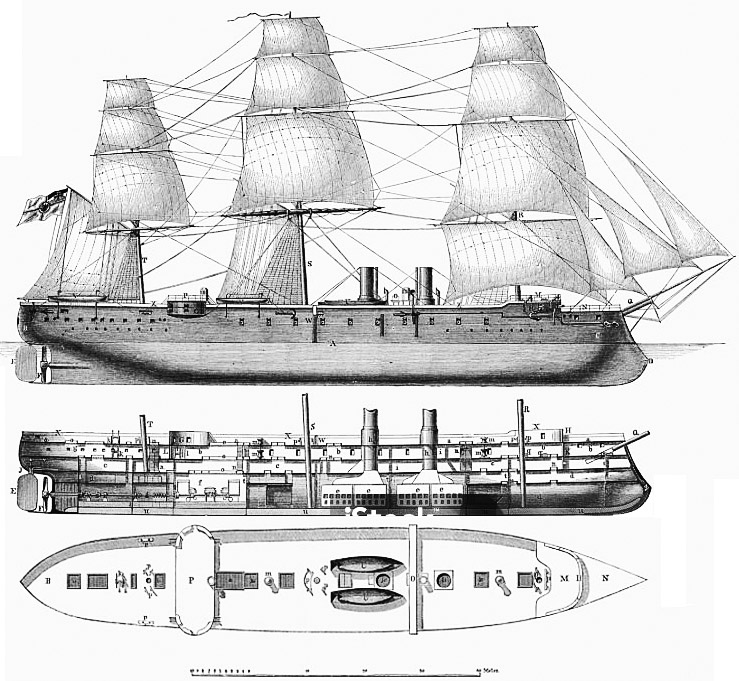

König Wilhelm was very large for a “frigate” indeed, but the term applied to her single main artillery deck. She was quite long at 108.6 meters (356 ft 4 in) at the waterline and 112.2 m (368 ft 1 in) overall for a equally impressive beam of 18.3 m (60 ft) -10/2 ratio, and a draft of 8.56 m (28 ft 1 in) forward, 8.12 m (26 ft 8 in) aft. Her displacement broke records for a warship at 9,757 metric tons (9,603 long tons) at normal load and she went up to 10,761 t (10,591 long tons) when fully loaded, passing the symblic 10,000 tonnes mark. Only a few civilian ships reached that level, notably Brunel’s 32,160 tons Great Eastern in 1859. But she broke the record for a warship, she was indeed larger than HMS Achilles (launched 1863) and only came close to the Minotaur class (1863-66) at 10,600 to 10,700 tonnes. Only the RN until then possessed ironclads of that size in the world.

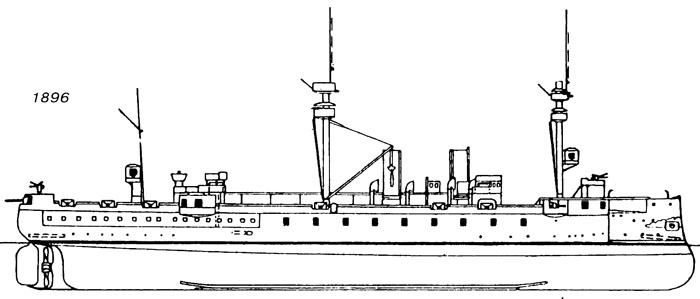

As hull construction was concerned, she was very much close to the aforementioned Achilles, constructed with transverse and longitudinal iron frames and her lower hull being subdivided into eleven watertight compartments plus a double bottom running over 70 percent of her length. She wa sthus protected against grounding and even hitting a submerged reef to an extent. She was a relatively handsome ship, except for the upper battery ended fifteen meters short of her ram bow which broke her profile. She had two funnels and a conning tower between them, three masts with a barque rigging and an aft bridge, located between the main and aft masts. Another sticking feature was her redoubt like casemate aft, at the same height as the bridge for an upper gun with a much better traverse than her conventional, iif heavy battery. She had her main artillery concentrated amidships and she was armoured in such a way as to be considered as a central battery ironclad, one of the first of such new breed.

The ship amounted to 36 officers and 694 enlisted men most of which being gunners and many others dedicated to her rigging. While she served as a flagship, there was on top of this a command staff with nine officers and 47 enlisted men. She carried for them a fleet of small boats, including two picket boats, two launches, a pinnace, two cutters, two yawls, and one dinghy. No doubt they could carry a substantial landing party altogether.

Powerplant

She was powered by a British machinery from Maudslay, Son & Field of London. It was a horizontal, two-cylinder single-expansion steam engine, driving a four-bladed screw propeller 7 m (23 ft) in diameter. The eight boilers that fed this engine were built by J Penn & Sons of Greenwich. These were rectangular, single-furnace tank boilers. They were distributed bwteen two enclosed boiler rooms, which came with twenty fireboxes in each and working at 2 standard atmospheres (200 kPa). Each boiler room had its auxhauts truncated and vented into its a single funnel. The latter were not telescopic and the propeller cannot be jacked up, it was fixed.

The steam propulsion system was rated at 8,000 metric horsepower (7,900 ihp), which was quite impressive at the time. For reference, the Minotaur class reached around 6,500 ihp, and Achilles 5700 ihp. It remained unsurpassed before HMS Alexandra launched in…1875. This have her a top speed of 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) but on trials König Wilhelm in fact exceeded this, her powerplant pushed red hot cranking up as much as 8,440 metric horsepower (8,320 ihp) and 14.7 knots (27.2 km/h; 16.9 mph). To feed her gargantuan fireplaces she carried 750 t (740 long tons) of coal, giving her a maximum range of 1,300 nautical miles (2,400 km; 1,500 mi) at the cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

This was seconded by a barque rig totalling 2,600 square meters (28,000 sq ft), but when added to her ssteam power, it did add little but under the greatest wind forces, and in that case it was reduced anyway. The Prussian Ironclad was not supposed any way to venture far from the Baltic or North sea, although the squadron went to train in the Bay of Buscay at some point and she was deployed to the Mediterranean.

Her first captain on trials noted she had “satisfactory sea-keeping qualities”, was responsive to from the helm and bled speed at a reasonable rate when hard rudder, with a moderate turning radius. Steering was controlled with a single rudder but later it was found she suffered from severe roll. She howver had a very reasonable pitch.

From the Kombrig Kit src

Protection

As built she had a wrought iron plating armour, placed over a teak backing, as custimary for the time. In overall thickness it reached almost a meter thick all combined.

Waterline: Thickest amidships, upper 305 mm (12 in) thick, lower 178 mm (7 in) backed in both cases by 250 mm (9.8 in) of teak.

Upper belt: It was reduced to 152 mm (6 in) in the stern and stopped short of the bow, just as the main artillery deck was cut down.

Lower belt: 127 mm (5 in) thick still at the bow and stern, but the teak backing was reduced to 90 mm (3.5 in) at both ends.

Central battery: 203 mm (8 in) and 150 mm (5.9 in) thick plating. Bow and stern capped ends 150 mm thick transverse bulkheads.

Main Coning Tower: 100mm (4 in) sides and 30mm (1.1 in) roof.

Aft Conning Tower: 50mm (2 in) sides and 30mm (1.1 in) roof.

Armament

As built, König Wilhelm had a main battery comprising thirty-three (33) rifled 72-pounder cannon. Thuis was short lived however as as soon as she reached Germany, they were replaced with nineteen (19) Krupp 24 cm K L/20 guns. This was rounded out by four 21 cm (8.3 in) guns. Of course it all changed later in her career, in 1885-88, and in 1895-96.

28 cm (10 in) K L/18 C/68 guns

All but one were mounted in a central battery, nine either broadside. The nineteenth one was a Chase gun at the stern and located directly in the commander’s quarters. For them a provision of 1,440 rounds were stockpiled. Thy could depress to −4°, elevate to 7.5° for a max range of 4,500 m (14,800 ft).

20.9 cm/20 (8.3 in) RKL/22.5 C/68 guns

These four Krupp guns were located on the upper deck. Two were in the peculiar casemates near the stern, each having three firing ports, hanging over the sides to fire aft or forward, and two others mounted near the bow as chase guns only. They could depress to −5° and elevate to 13° and had en even better maximum range of 5,900 m (19,400 ft). Note that sources diverged on this. Conways for example states that they had only 18 main guns in the broadside, and instead five, not four secondary upper deck guns, including an extra chase gun.

Modifications

From a main battery of thirty-three rifled 72-pounder cannon (which were recycled soon into Prussian fortifications) she obtained the 24 cm K L/20 guns and 21 cm (8.3 in) guns as seen above. But in 1878-1882 she was already rebuilt. She received eight rectangular boilers and her bow ram was strengthened. The armament was apparently unchanged.

From a main battery of thirty-three rifled 72-pounder cannon (which were recycled soon into Prussian fortifications) she obtained the 24 cm K L/20 guns and 21 cm (8.3 in) guns as seen above. But in 1878-1882 she was already rebuilt. She received eight rectangular boilers and her bow ram was strengthened. The armament was apparently unchanged.

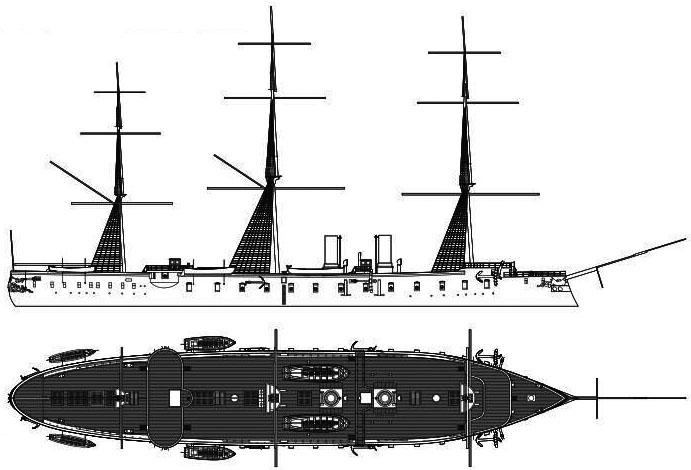

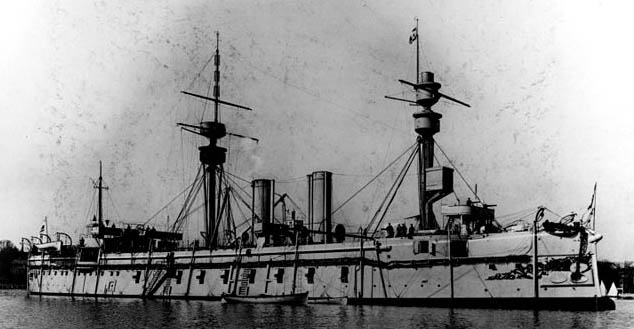

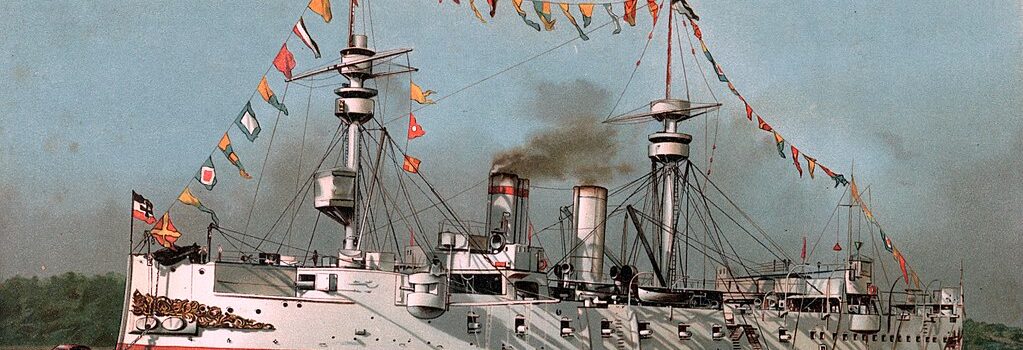

König Wilhelm after the 1895–1896 reconstruction into an armored cruiser

Next, König Wilhelm in the 1880s saw the removal of one of her 209mm/20 secondary guns, for the addition of seven 149mm/28 RKL C/88 guns and four single 79mm/25 RKL/27 C/73 as well as six 5-barrelled 37mm/27 Revolver Cannons L/30 (likely Nordenfelt), and this was rounded up with five 350mm TT, with two located at the bow, two at the beam and one at the stern in a typical lozenge pattern for the time.

Her third and major reconstruction was a radical one. In fact so radical the cost was almost the same as building a brand new ships. She was transformed into an armored cruiser over a year in 1895–1896. Her armour was completely modified. Old iron plating and teak were cut away, replaced with stronger Krupp cemented steel. The space regained also allowed internal modifications, notably a completely new electric lighting. The conning tower was also armoured in steel, with 50 to 100 mm (2.0 to 3.9 in) sloped plates and a 30 mm (1.2 in) thick roof.

As rearmed, she had twenty-two 24 cm L/20 guns in her briadside battery, plus a single 15 cm (5.9 in) L/30 gun (with 109 rounds) at the stern, plus eighteen 8.8 cm (3.5 in) quick-firing guns on the upper deck, nine on each broadside to deal with torpedo boats.

These new 15 cm Krupp guns had a range of 8,900 m (29,200 ft).

In addition she received five new 35 cm (14 in) torpedo tubes above water replacing the former ones and supplied with 13 Schwarzkopf torpedoes.

Only her powerplant was left unchanged and she was likely only able to reach 16 knots at best.

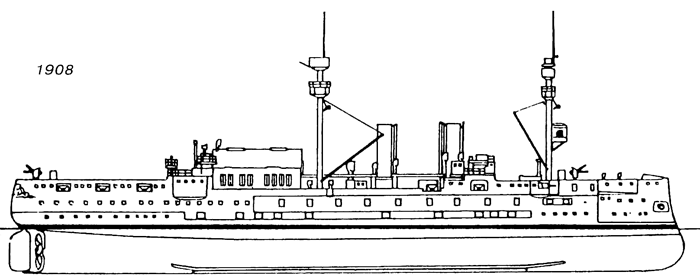

Her last modification was as a training ship in 1904. She then had lost all interest as an “armoured cruiser”, being far too slow and was sidelined as a “coastal cruiser”. Most of her armament was removed and instead she only kept sixteen 8.8 cm L/30 guns on the upper deck. In 1915, she saw even twelve of these removed, leaving just four.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | Design: 9,757 t, FL 10,761 t |

| Dimensions | 112.2 x 18.3 x 8.56 m (368 ft 1 in x 60 ft x 28 ft 1 in) |

| Propulsion | Single-expansion steam engine, 8 × boilers: 8,000 PS (7,900 ihp) |

| Sail | 2,600 m2 (28,000 sq ft) |

| Speed | 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Range | 1,300 nmi (2,400 km; 1,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 19 × 24 cm K L/20 guns, 4 × 21 cm (8.3 in) guns |

| Protection | Belt 152 to 305 mm (6 to 12 in), Battery 150 mm (5.9 in) |

| Crew | 36 officers+ 694 enlisted men |

Career of SMS König Wilhelm

SMS König Wilhelm was laid down in 1865 purchased by the Prussians on 6 February 1867, named at first “Wilhelm I” and then “König Wilhelm” on 14 December, before launch, on 25 April 1868. After fitting-out she was commissioned on 20 February 1869 under Kapitän zur See Ludwig von Henk. She then joined Friedrich Carl and Kronprinz for training in August-September 1969.

SMS König Wilhelm was laid down in 1865 purchased by the Prussians on 6 February 1867, named at first “Wilhelm I” and then “König Wilhelm” on 14 December, before launch, on 25 April 1868. After fitting-out she was commissioned on 20 February 1869 under Kapitän zur See Ludwig von Henk. She then joined Friedrich Carl and Kronprinz for training in August-September 1969.

In May 1870 she sortied as flagship with Kronprinz and Friedrich Carl to join Prinz Adalbert to visit Britain. Friedrich Carl ran aground in the Great Belt and had to return. König Wilhelm, Kronprinz, and Prinz Adalbert arrived in Plymouth and stayed there for celebrations by their hosts, and a few days later, Friedrich Carl returned from Kiel. On 1 July they departed for a training cruise to Fayal, Azores, Portugal. Meanwile, they were oblivious to the rising tensions with France over the Hohenzollern candidacy for the Spanish throne which spiked with the infamous Ems dispatch. While they were undergoing through the English Channel, they learned about the inpending war. They were in a ver precarious situation as at any moment, the French Artlantic fleet could sail up and fight them. By that time the French Navy dwarved the Prussian Navy, despite the fact her assets were distributed between there and the Mediterranean. Prinz Adalbert was sent to Dartmouth to be kept informed of events through displamatic channels whereas the rest of the squadron joined her on 13 July, and promptly returned home at high speed, trying to reach the Jade before being cutout.

They arrived at Wilhelmshaven on 16 July, three days before France declared war on Prussia. Now their role was to avoid a blockade, and forced it out if possible. Fortunately for them, the French Navy was ill-prepared for this campaign. Having no relays to the Baltic, neutral Denmark, Netherlands and Britain allied to Prussia, the large blockading force could only make a short termed show of force before running out of coal. Coasling at seaz proved all but near-impossible especially in the winter.

Kronprinz, Friedrich Carl, and König Wilhelm stayed at Wilhelmshaven, ready to depart at a moment notice. Breaking the French blockade would not be however easy given the French local superiority, even after the arrival of the turret ship Arminius from Kiel, all under the command of Vizeadmiral (Vice Admiral) Eduard von Jachmann. They made a first sortie in early August 1870 out to the Dogger Bank but spottd no French ships. By that stage the blockade was already over and soon the situation on land would make this irrelevant anyway. König Wilhelm however suffered from chronic engine trouble, jus as the other two Ironclads, leaving Arminius alone to multiply sorties. König Wilhelm, Friedrich Carl, and Kronprinz were sent to the island of Wangerooge while Arminius was sent to the mouth of the Elbe until the end of the war. On 11 September they joined Arminius for a sortie deep in the North Sea but saw no French ships. By that time, they all had been sent bac to France and the crews partly sent as extra infantry on the desperate defence of Paris and other cities.

After the war in the new Imperial Navy, she resumed peacetime training routine divided between summer and winter assignations under General Albrecht von Stosch as chief of staff of the Imperial Navy. As an army man, he saw little use for the Navy and suggested it was organize for coastal defense only, and linked to fortifications. As a budget measure, König Wilhelm and others alternated between training in the summer and reserve in the winter, while half the fleet in addition had reduced crews as guard ships. In 1875 König Wilhelm cruised with Kronprinz, Hansa and Kaiser in local waters while being laid up in 1876 and 1877.

König Wilhelm collides with Grosser Kurfürst

König Wilhelm was recommissioned in early 1878 for the new training program and reached the straits of Dover on 31 May, still as flagship, when a manoeuver executed without proper communication ending in König Wilhelm involuntary colliding with Grosser Kurfürst, one of the new steam-only Prussen class ironclads, whuch had left Wilhelmshaven on the 29th. This 31st it all begun in the narrowest part of the Channel, when ceading priority to a pair of sailing vessels off Folkestone as customary at the time. The problem was that Grosser Kurfürst turned to port to avoid these while König Wilhelm was trying to pass them out, but distance soon fell between them. When it was realized what was about to happen it was already too late. Both Grosser Kurfürst and König Wilhelm’s tried to reverse and change course, but inertian brough them on a collision course anywa. Her ram bow tore open Grosser Kurfürst with enough presure nothing could stop the subsequent flooding. This became soon the biggest peacetime German naval tragedy. In eight minutes Grosser Kurfürst was under trapping 269 out of 500 crew. König Wilhelm also had severe flooding forward and her captain planned on beaching her until he was informed pumps were holding firm. She made it into Portsmouth for temporary repairs. While back to Germany she collided with the British smack “Tom” off Norderney, cutting her bowsprit, topmast and mizzen mast and later escorted to safety in Great Yarmouth.

The later court martial judged Rear Admiral Batsch, Captains Monts and Kuehne and Lieutenant Clausa, first officer aboard Grosser Kurfürst. König Wilhelm was in repairs and modernization from 1878 to 1882. Her involutanry ramming showed anway she could not ram enemy vessels without danger to herself and her it reinforced considerably at Wilhelmshaven, while being reboilered and rearmed for a more uniform gun battery.

König Wilhelm as a training ship

In 1885 she received fitting for Torpedo nets that she carried until 1897. In 1887 she took part in the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal ceremonies and in the summer training exercises with the I Division still as flagship, as well as the 1888 training year with Kaiser, Bayern and Württemberg but was in reserve from 1889 to late 1892. She was reactivated for 1892–1893. In 1893 she was now flagship for the II Division under Admiral Otto von Diederichs in Wilhelmshaven. On 20 February 1894 she commemorated her 25th anniversary attended by the new Kaiser, Wilhelm II and Ludwig von Henk, now Vizeadmiral. In April 1894, the II Division cruised in the north sea and channel, but the ironclad ran aground on a mud bank off Frisia. She was puled free by Deutschland and Friedrich der Grosse and damage was light. She visited Oslo and Bergen and proceeded to Scotland until back to Kiel in late May, taking coal and provisions for the summer exercises, acting as the opposing force, simulating a Russian fleet.

In 1895, König Wilhelm was drydocked at Blohm and Voss, Hamburg for her most intensive reconstruction, into an armored cruiser. It’s unclear why this decision was taken. She could have been retired due to her age. It seems a combination of factors, notably her large size and still excellent general condition. This enabled further useful years of service, but not as a frontline warship. Hr new appearance was radical, without her riging, new superstructures, new fighting masts and generous armament, which required 38 officers and 1,120 enlisted men. She was fully recommissioned only by 25 January 1897 and immediately took part in the Fleet Review for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. She went on training with the fleet until 1904, when it was clear her low speed was now a handicap. She was removed from active duty and from 3 May 1904, she became a harbor ship, then barracks ship and training vessel for naval cadets in Kiel from October 1907. It sems she was rebuilt again in 1907-1908 for her new role, her armament radically rediuced. She ended at th Naval Academy at Mürwik and was assigned in 1910 the old corvette Charlotte as support vessel, the SMS Medusa in 1917. She saw many cadets in her decks thoughout World War I and until 1921. On 4 January she was at last stricken and broken up in Rönnebeck. Given the economical context in Germany at the time and lack of conservation practices, she could not be saved. But she was worth it, just as HMS Warrior, given her historical significance.

Read More/Src

Books

Diehl, S. W. B. (1898). “Great Britain’s Naval Review at Spithead”. Notes on Naval Progress. ONI

Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Kaiser’s Battlefleet: German Capital Ships 1871–1918. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing.

Gottschall, Terrell D. (2003). By Order of the Kaiser: Otto von Diederichs and the Rise of the Imperial German Navy, 1865–1902. NIP

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. NIP

Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books.

Lyon, Hugh (1979). “Germany”. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Irving, Joseph (1879). The Annals of Our Time. London: Macmillan and Co.

von Rabenau (1880). Die Kriegs-Marine des Deutschen Reiches. Bremen: Schünemann’s Verlag.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge.

Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and company.

Links

“Current Foreign Topics. A Court-Martial Ordered in the Case of the Collision of German War Ships” (PDF). The New York Times. 9 January 1879.

https://www.navypedia.org/ships/germany/ger_bb_koenig_wilhelm.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMS_K%C3%B6nig_Wilhelm

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:SMS_K%C3%B6nig_Wilhelm_(ship,_1868)

https://books.google.fr/books?id=o6AzLN6GOBEC&redir_esc=y

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign