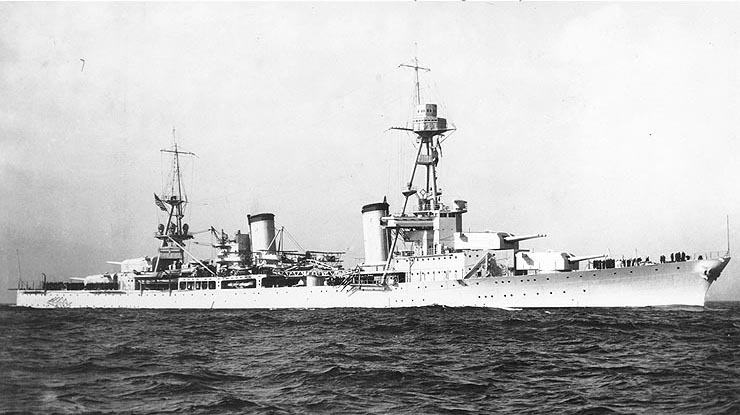

Pensacola class heavy cruisers (1928)

The top heavy cruisers

This summup in a quick way the fundamental problem of the first two cruisers of the USN, experiments of the new abstract concept imposed by the treaty: A 10,000 tonnes cruiser with a ten inches armament, whatever its composition. Engineers were free to stack as many of these as the admiraltly wanted to, giving them an advantage. With ten guns in large triple superfiring turrets, tall superstructures, tall and heavy tripod masts, were combined to a low freeboard, light flush deck hull with a narrow waist and almost no armor weight to compensate, this resulted in ships that were excessively top-heavy, rolled heavily and ended as poor seaboats, bordering to the dangerous.

Fortunately plans were made to rebuild them and ultimately started before and after the attack of Pearl Harbor. Both fought in WW2, in the Pacific. Pensacola escorted various convoys until the Battle of Tassafaronga, took part in the Marshall and Carolines campaign, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, earning 12 battle stars.

Salt Lake City took part in the Battle of Cape Esperance, Battle of the Komandorski Islands, Battle of the Komandorski Islands, second Battle of the Philippine Sea, and Iwo-Jima-Okinawa, earning 11 battle stars;

Design development: 1922-1926

After the WWI-inspired Omaha class, a scout cruiser program of 1917 built as the Washington treaty took place. When the treaty of Washington was ratified, by the great naval powers in February 6, 1922, the nomenclature of ships types was modified on paper and, in a sense, an older concept consecrated. Among these changes, the most notable was the appearance of a new class in its own right, the “Washington Cruiser” which in fact was the typical form of the heavy cruiser, a new category of Washington-compliant type cruiser, so 10,000 tons – eight 8 inches (203 mm).

Note: This article was rewritten after five years. New C&R archives alternatives and preliminary designs are integrated as well as completing in a proper way their details operational career.

The concept of heavy cruiser

The “heavy cruiser” as called, was however not a 1922 concept: Indeed, it went back to the consequences of the construction of HMS Dreanought so right back to 1906. This was such a revolution that costs alone justified the constrution of new “heavy cruisers” of the time, which were armoured ones. This was for obvious reasons as for many, the new battleship merged both roles into one. Aside the heavy artillery, speed was a considerable factor and the new dreadnoughts were now as fast as armored cruisers, making them obsolete. The class entirely disappeared, and apart the exception of the German Blücher, this went down to questioning the concept of cruiser entirely. Admiralties spoke of “large fleet destroyers” to replace cruisers entirely. In the US it traduced into a construction vacancy of ten years, after the Chester class in 1907. Cruiser construction did not stop round the word though, as it was believed scout cruisers always had a secondary role, notably leading flotillas of destroyers. These light cruisers, assimilated to the 1900s “2nd/3rd class” were still built by the belligerents, notably for the Royal Navy (which laid down more than 60 hulls in 1910-1918), Kaiserliches Marine, Regia Marina and KuK Kriegsmarine. But a gap was observed for France, Japan, and Russia and new hull were only laid down almost during WWI itself. All of these were “light cruisers” in the sens later given by the treaty, but at the time just known as “cruisers” or “scouts”.

The concept of heavy cruiser was really pioneered by the British. It was applied to a new breed of “cruiser-killer”, very fast, unprotected by armed with the latest heavy QF guns developed by Vickers: The Hawkins class. Design started in 1914 but construction in 1916, but only one, HMS Cavendish, commissioned on 1 October 1918. All the others were completed after the war, the last, HMS Effingham, five years after she was launched, and rebuilt. They all had in common their seven single 7.5 in (191 mm) guns and only light guns as completement, for a 9,800–9,860 long tons (9,960–10,020 t) standard hull, and 31 knots.

This class, still in completion when the treeaty was signed, no doubt fuelled heavily discussions within the redaction of the treaty. It was seen by all signatories as a new clas of its own and also the British wanted a justification not to cancel them as the risk was they would be considered as not-standard and therefore excluded. Even though no other nation had such concept in store at the time, the Hawkins class was revolutionary enough to consider it as a forerunner of a new class. It was eventually decided to shape it in the treaty as a “heavy cruiser”, with a maximum armament defined as 8 inhes or 203 mm, more than the British one as it was felt than on a near 10,000 tonnses, this could be achieved. The tonnage was also soon fixed to this handy limit.

At that stage there was still an elephant in the room: The Hawkins class had all their guns in single mounts, which reduced the number of guns that could be carrier, because of the firing arcs needed to be optimized. The Hawkins in effect only had five guns in the axis, so with a useful manner adopted also for the standardized C and D class. But the beam authorized two more, which were installed on the broadside as a compromise. Technically in 1916, it was known how to carry 10-inches guns in twin turrets – It was done on the older last armoured cruisers, band such solution combined with the Hawkins arrangement could have led to an alternative design. But the cruisers back in 1915 were needed fast, and single mounts were a known and trusted solution. It’s only from the HMS Enterprise, first of the new cancelled “E-class” light cruisers, that a new twin turret was tested. Both the development of proper mountings for the new 8-in guns was left to decide and develop by the signatories. In fine, this also served the purposed of the treaty in its limitations goal, as this would force the signatories to work out multiple solutions that would delay the construction of new cruisers by a few years. That’s what happened, despite the treaty imposed no vacancy for cruisers.

In an uncertain future where scenarios did not excluded a war with the British Empire, the USN was pleased with the Omaha class cruisers, which gave them a clear advantage over the British late C and D class in firepower and speed. However the British Hawkins Class cruisers designed oriignally to hunt down German commerce raiders worried the US admiralty and soon became the standard for cruisers designed for independent operations (a role more fitted for their status as modern continuations of the Frigate). US Planners soon asked for 8-inch guns and 32.5 knots to counter the Hawkins class and designs produced by the US Navy were formulated in response, eventually leading to the Pensacola’s final design through many iterations in 1922, 1923, 1924 and 1925 when the final draft was accepted and plans drawn.

The admiralty – C&R/BuEng discussions and concepts

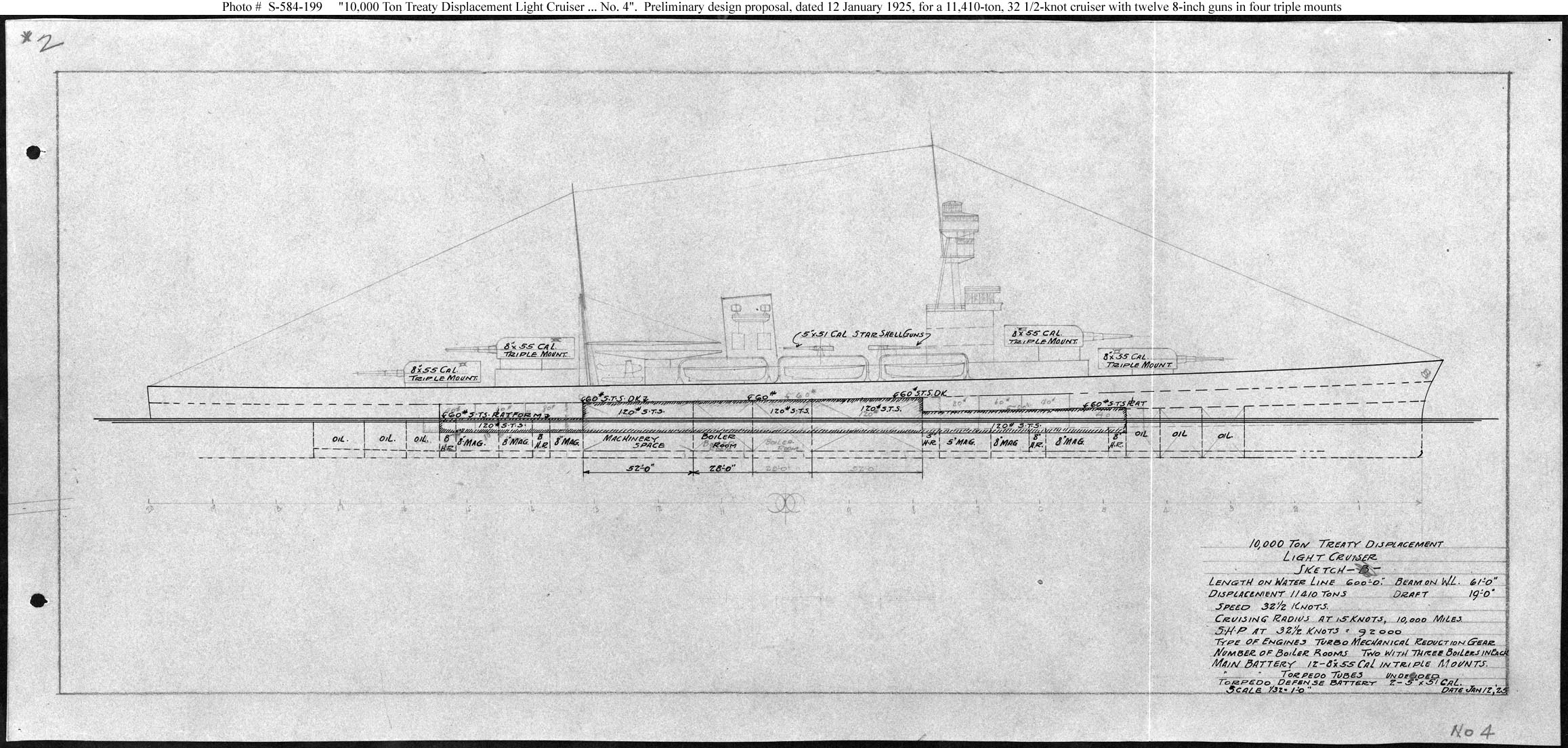

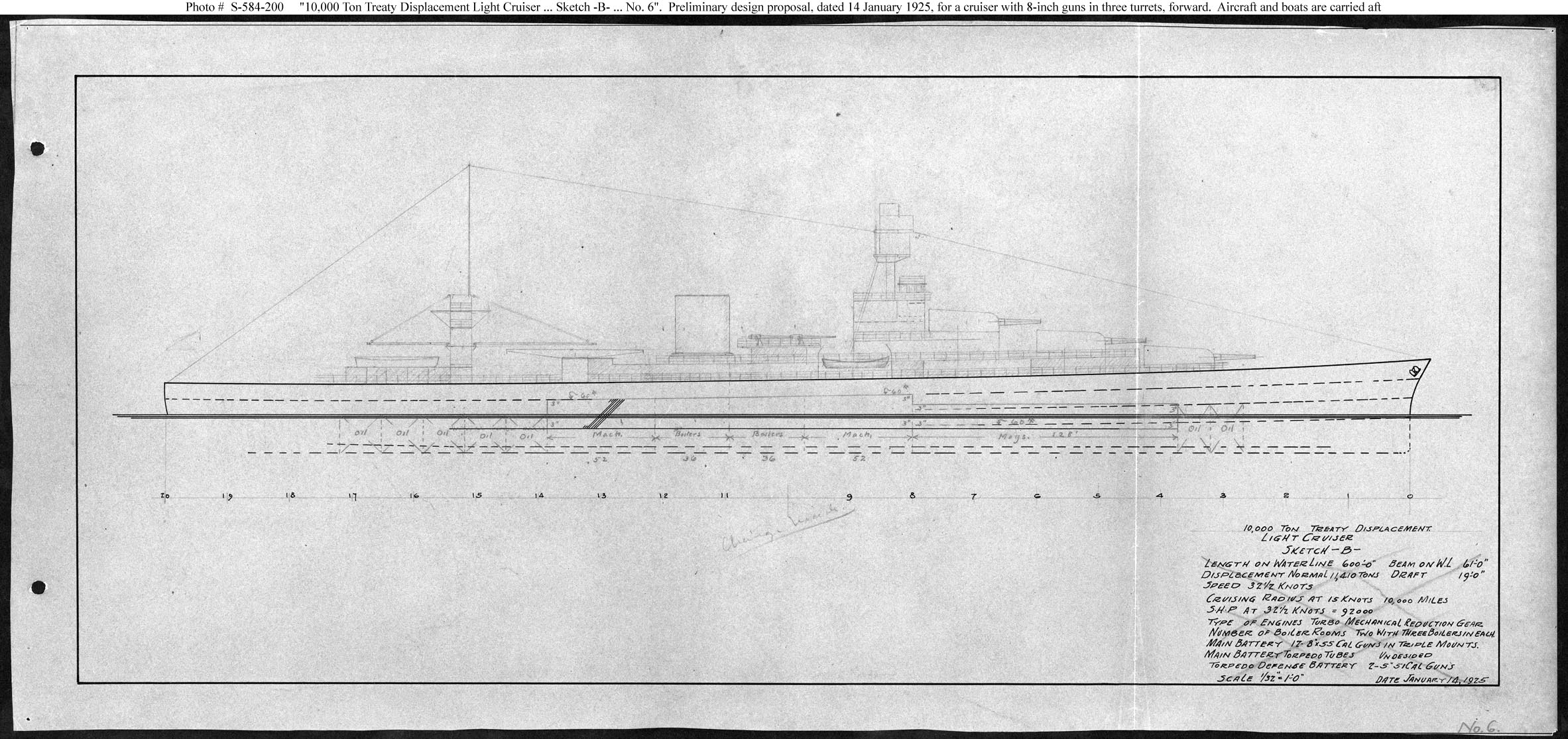

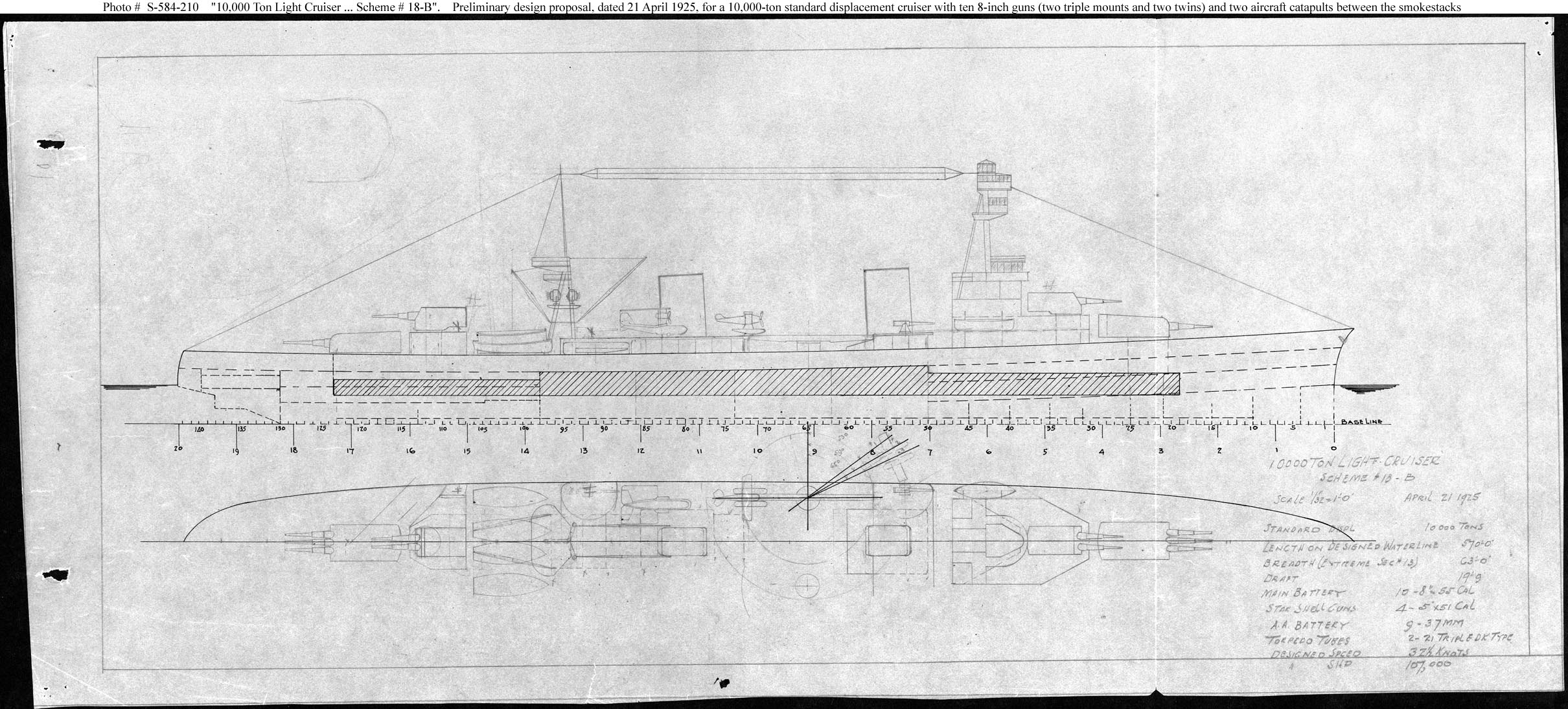

This part presents the lineage of heavy cruisers based on existing plans, preserved, from the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BuC&R) and the Bureau of Engineering (BuEng) in 1922-24. Indeed, it’s only on 1924 that the final design was sanctioned, ordered on 7 March 1925. The design was worked out in between, and there was the 9 July 1926 supplementary contract voted for the sister-ship of this experimental cruiser. With it, the USN went to a brand new leap. Many design solutions were envisioned, notably without (early period) and with aviation facilities. At first, a very heavy arrangement of twelve guns was chosen in four triple turrets. There was no way at the time to design “light” turrets with independent mounts, they would have been way heavier. So solidary mounts were chosen early on to cram more guns in relatively light models, allowing to design quickly a triple model. The major problem not really thought after at the time was the major dispersion due to muzzle interference when all three fired simultaneously.

The General Board had strongly favored cruisers before 1922 and the Washington Treaty renew interest in them, turning these new 8-inch gun cruisers into “junior capital ships”. They were still intended for a scouting role but for the Pacific. One criteria was to use them in case a commander was deprived from his precious capital ship if any was to be lost under the Treaty. Using single ships for roles such as convoy escort and shore bombardment was almost fodbidden to capital ships and therefore turned to these new heavy cruisers. In WWI this role was filled by obsolete battleships and armored cruisers, all been wiped out by the treat and these heavy cruisers were intended to take their role.

The General Board strongly favored cruisers before 1922 by the treaty just reinvigorated the concept, turning as it was said, 8-inch gun cruisers into a kind of “junior capital ship”. The scouting role was even more important for the Pacific war.

The General Board already evaluated a number of scout cruiser designs leading up to the Treaty and still do so of alternatives up to 1924, even when came the authorization of the Pensacola. The General Board concluded that it was useful to split roles between protecting or destroying merchant ships and operating with the fleet. For the first “scouts”, a top speed of 32 to 34 knots was required, reduced in the latter to 27-32 knot with variants on guns, protections and facilities. The Board agreed however that aircraft were secondary, but this position was revised in 1925.

By December 1924 evidence showed outside the US, signatory countries were willing to launch in a cruiser building race. Only because of this, Congress authorized eight new cruisers in FY1925 and the Pensacolas (CA 24-25) were to be the first of them, followed by six more (the future Northamptons, CA 26-31) intended as improved versions of the first. USS Salt Lake City (CA 25) was launched first on January 23, 1929, displacing 11,568 tons.

These were the first US Navy’s Washington Naval Treaty cruisers and first modern cruisers with 8-inch guns, turned to match Japanese cruisers of the time. The treaty at that point still defined cruisers up to 10,000 tons, as “heavy” with 8 inches guns but the denomination changed over time, from CL to CA. The American 8″ gun were not particularly well liked, they had effective range over the horizon, but only fired at 3 rounds per minute.

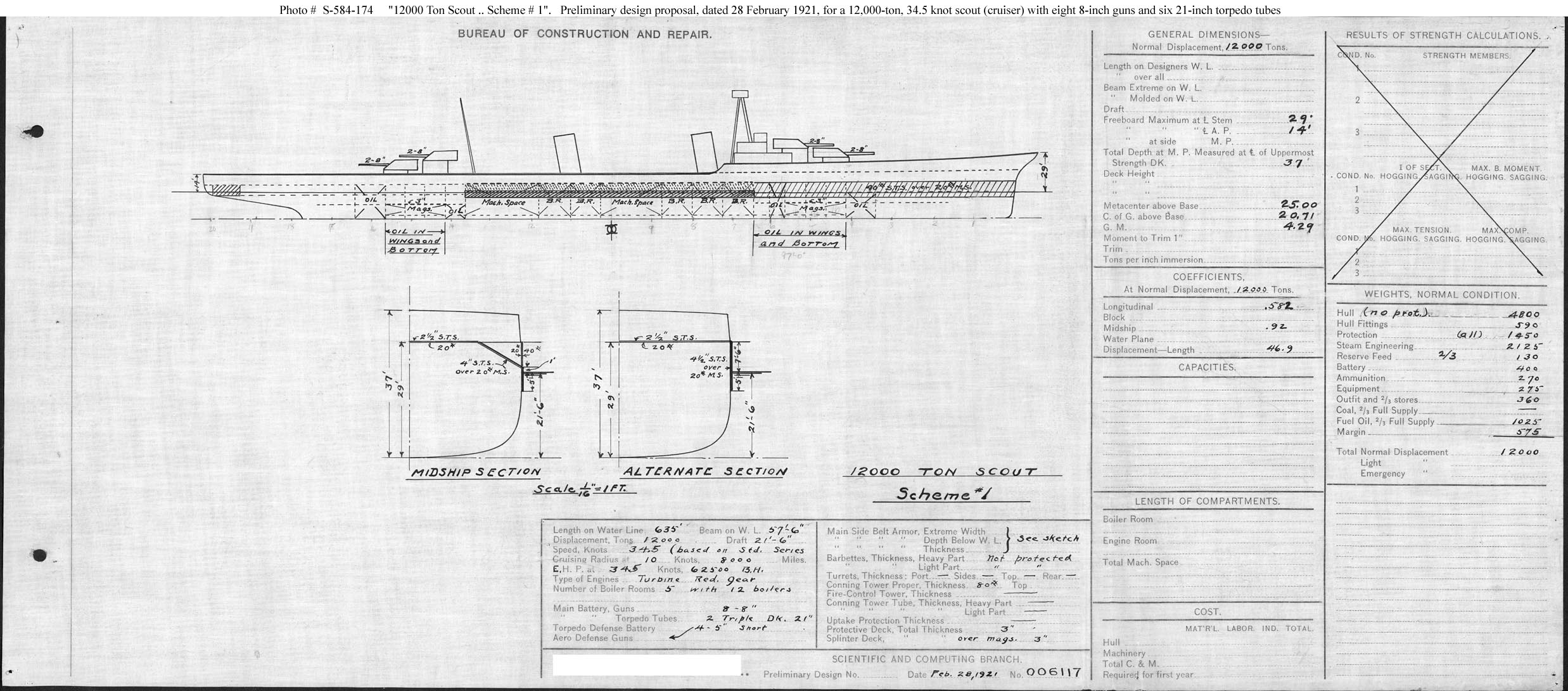

1922 design studies

1922 pre-washington 12,000 tons Sketch A, 12 guns, 6 TTs, 34 kts

Before the Washintgon treaty was signed, the USN asked C&R a new design of “scout” armed with 8-in guns, 34.5 knots, with a forecastle, very long and narrow at a ratio of 635 feets/57 fts 7 in (193 x 17.35 m). The interesting point was that like the Omaha class, she carried twin turrets, and in that case, two fore and two aft in superfiring pairs. The idea was a scout that can deal with flotilla leaders/light cruisers when encountered. It was complementary to the Lexington class battlecruisers and the general outline followed the same DNA. In fact, the original (final) design for the Lexington-class battlecruiser would have shared a unique arrangement of ten 14-inch guns in triple superfiring turrets over twins, and called “like scaled up Pensacolas”.

The Washington redistributed the chips completely and necessitated the whole of 1922 to reassess the needs.

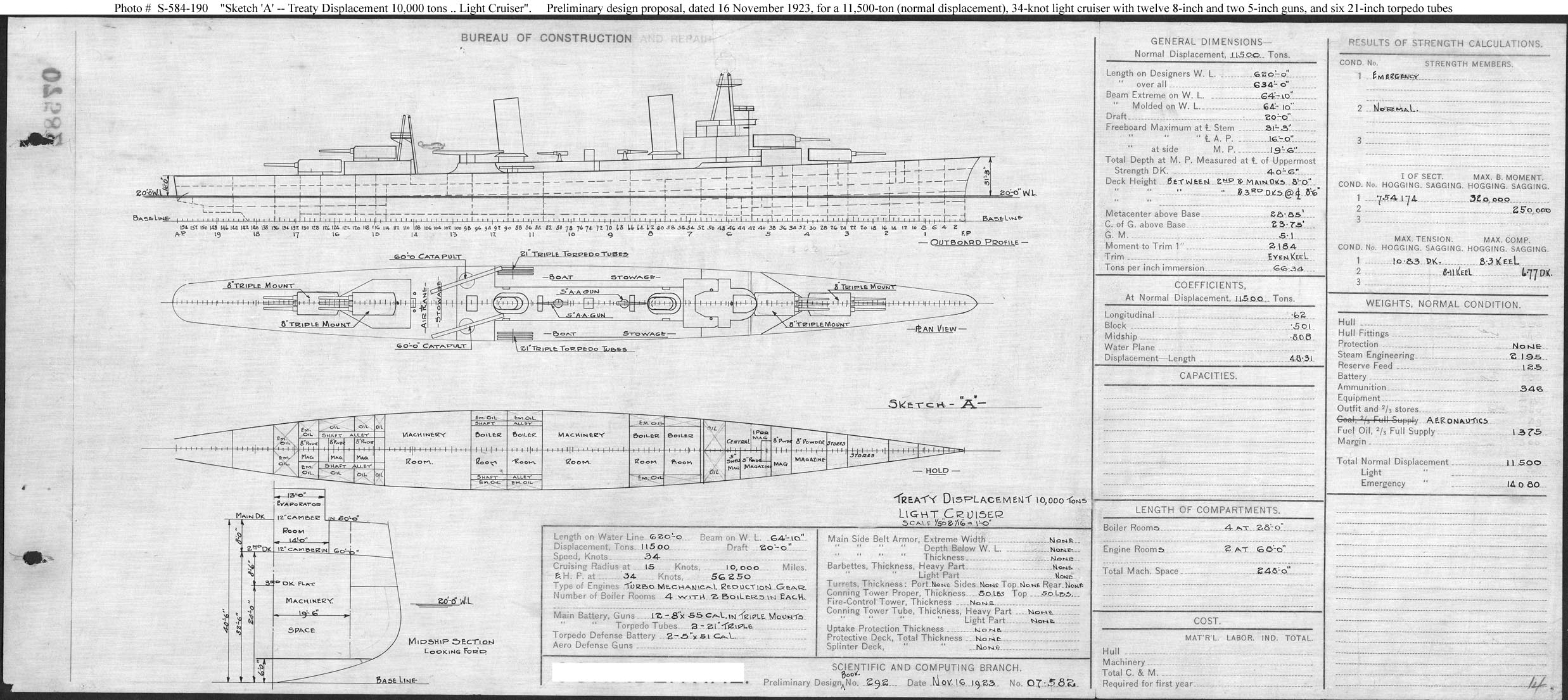

1922-23 early design studies

16 November 1923 11450 tons Sketch A, 12 guns, 6 TTs, 34 kts

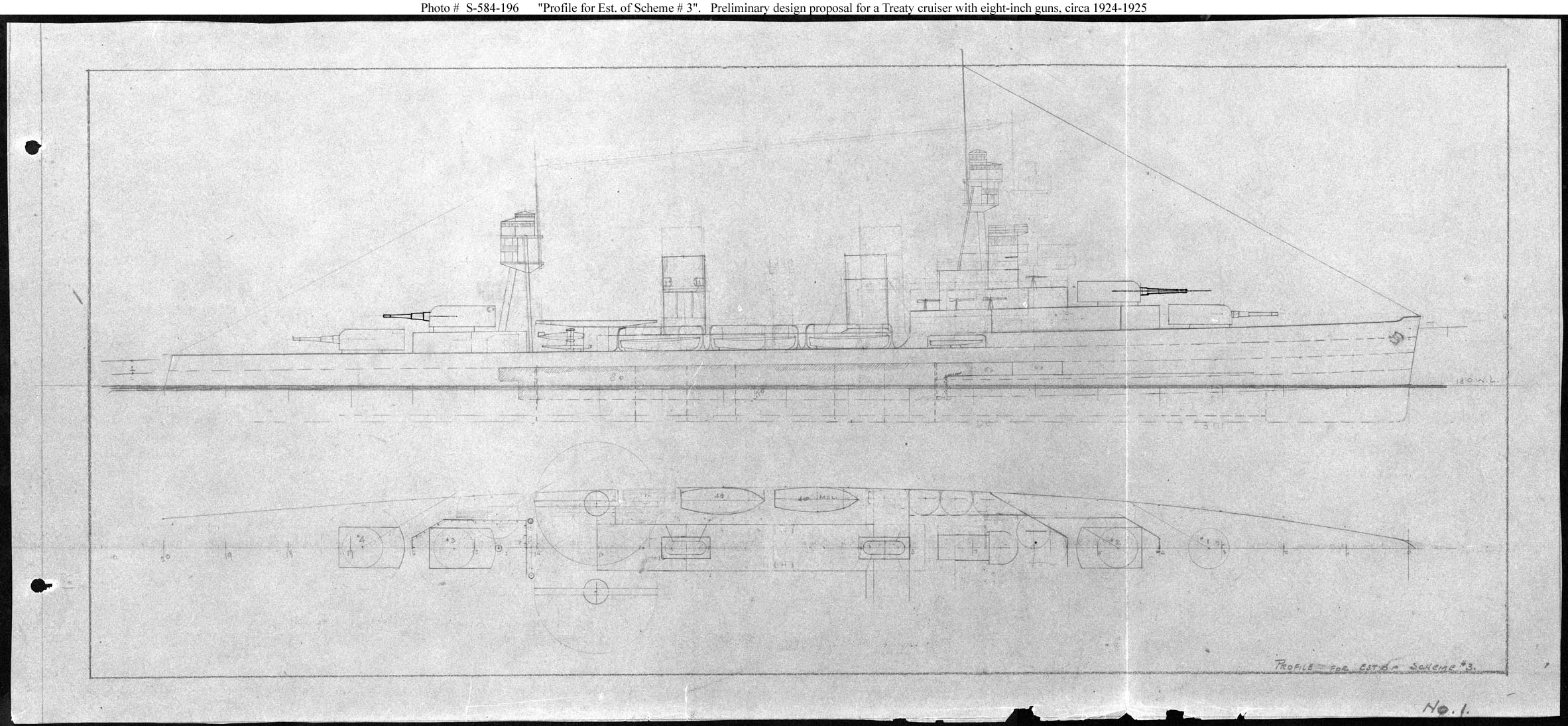

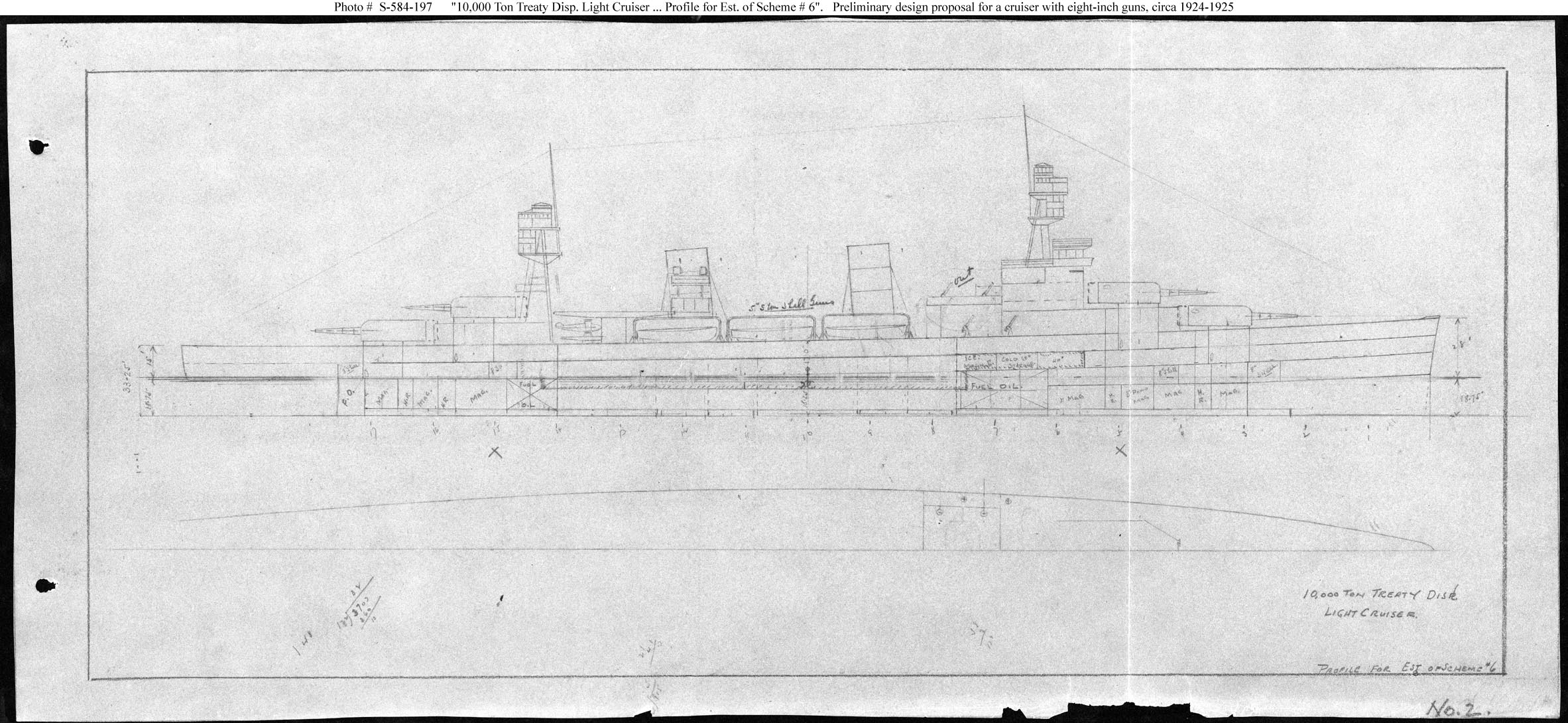

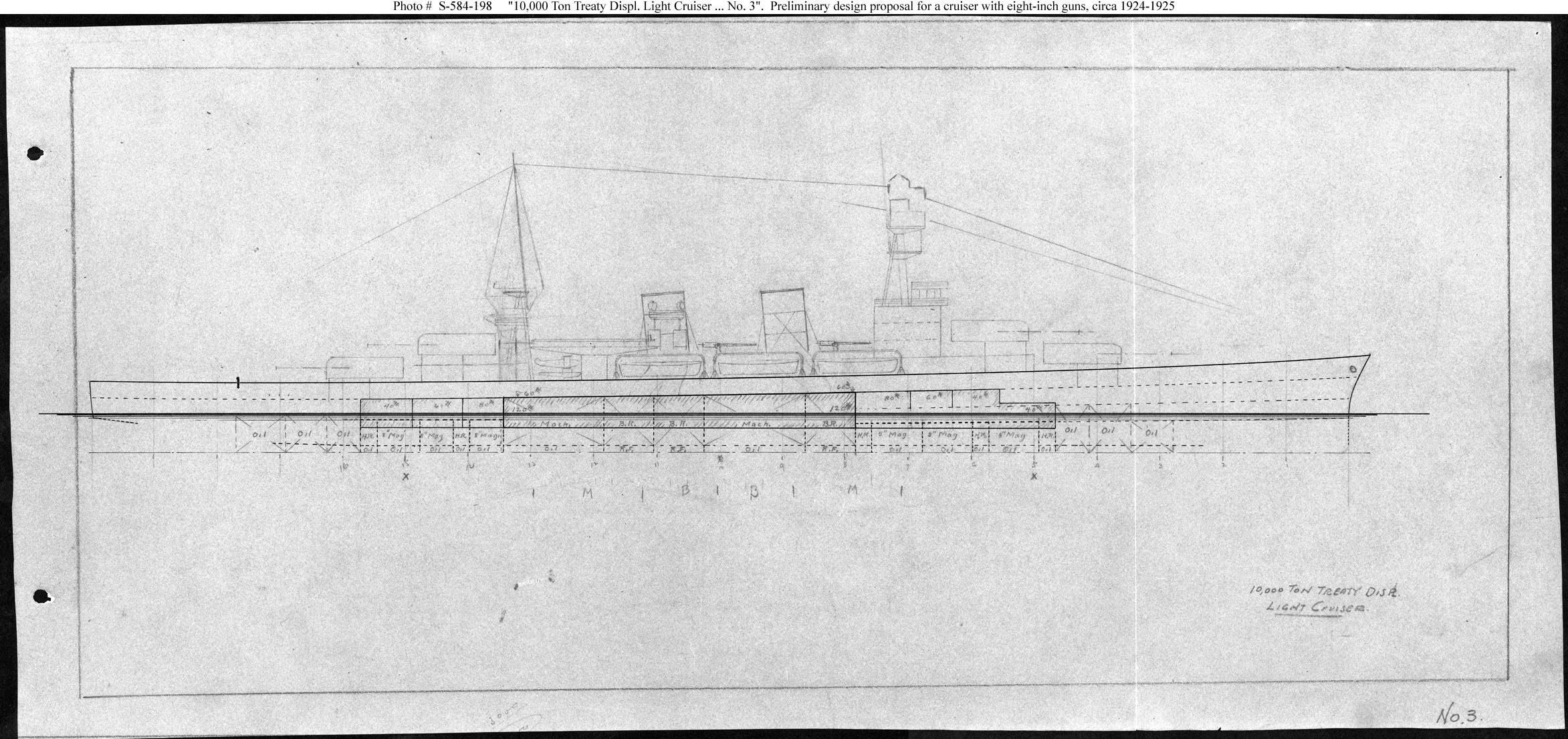

Preliminary design proposal “Profile for Est. of Scheme #3” 1924-25

10000 tons treaty light cruiser “Profile for Est. of Scheme #6” 1924

Same but #3

1925 12 guns design studies

N°4, 1925 design study for a 11,410 tons 32 kts cruiser, 4×3 8-in.

Sketch B N°6, 15 January 1925; 4×3 8-in

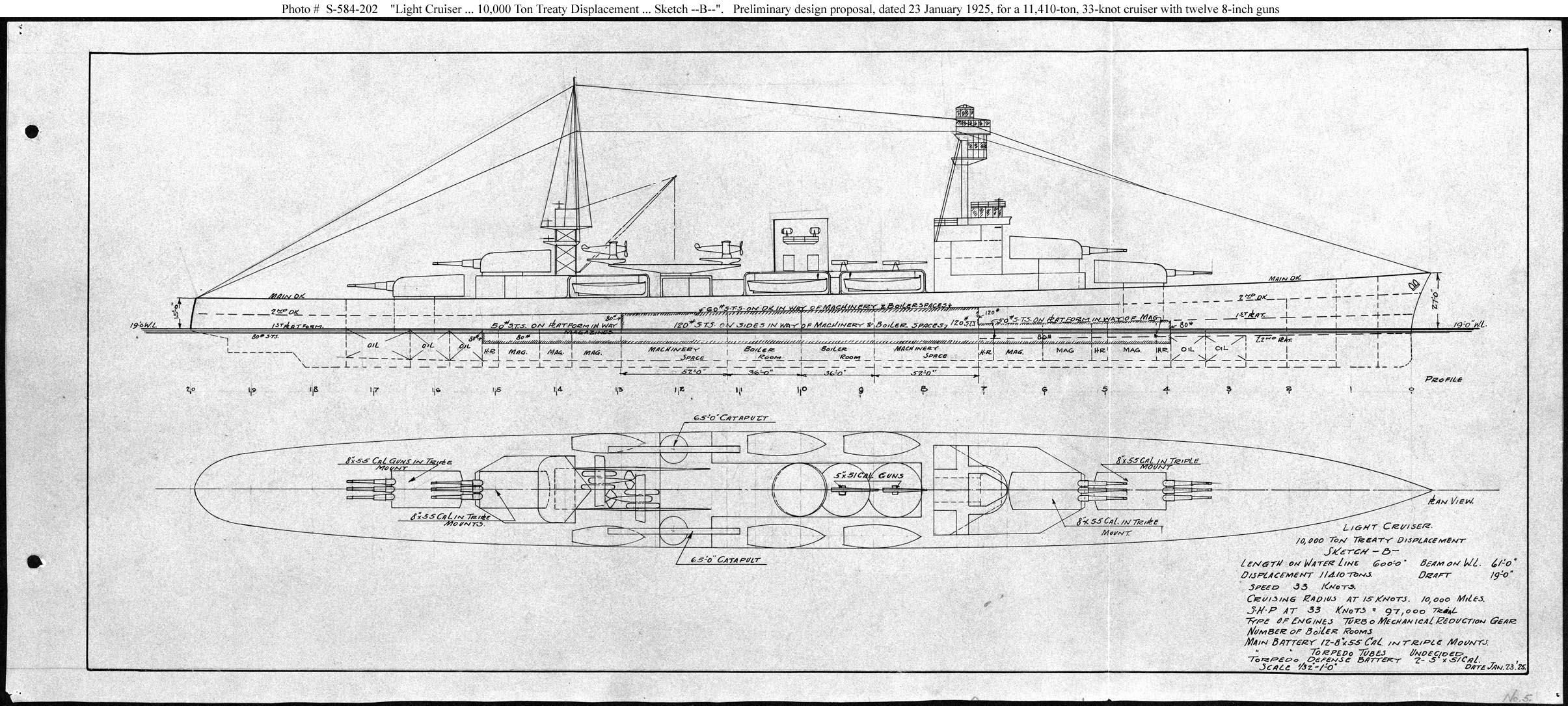

23 January Sketch B.

11,410 tons design study Sketch B with 4×3 8-in

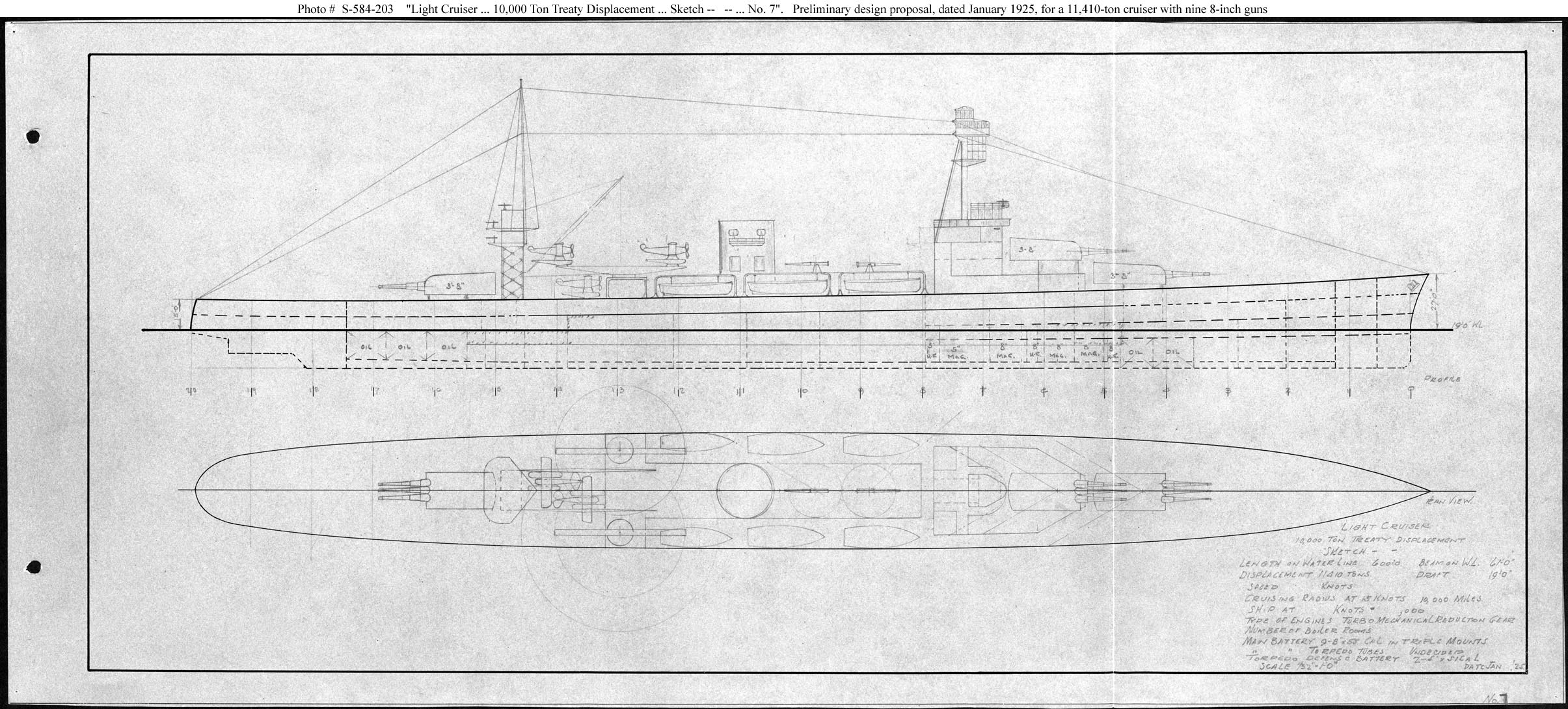

11,410 tons prelim. prop. N°7, with 3×3 8-in

“1925 Aviation cruisers” design studies

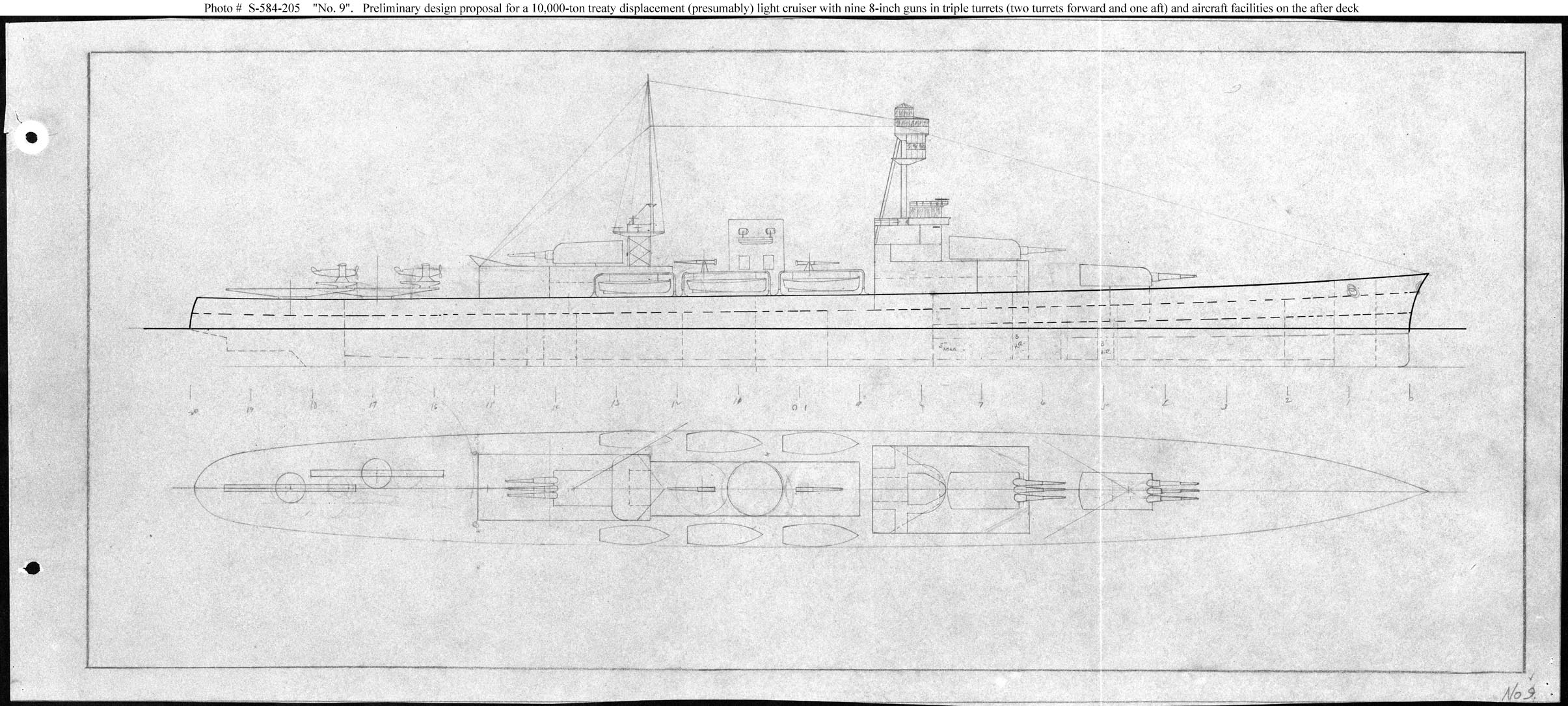

N°9 1925 design study with only 3×3 8-in but extended aft aircraft facilities. Note the artillery is much closer, as the supestructure and single funnel, so reducing the armour lenght.

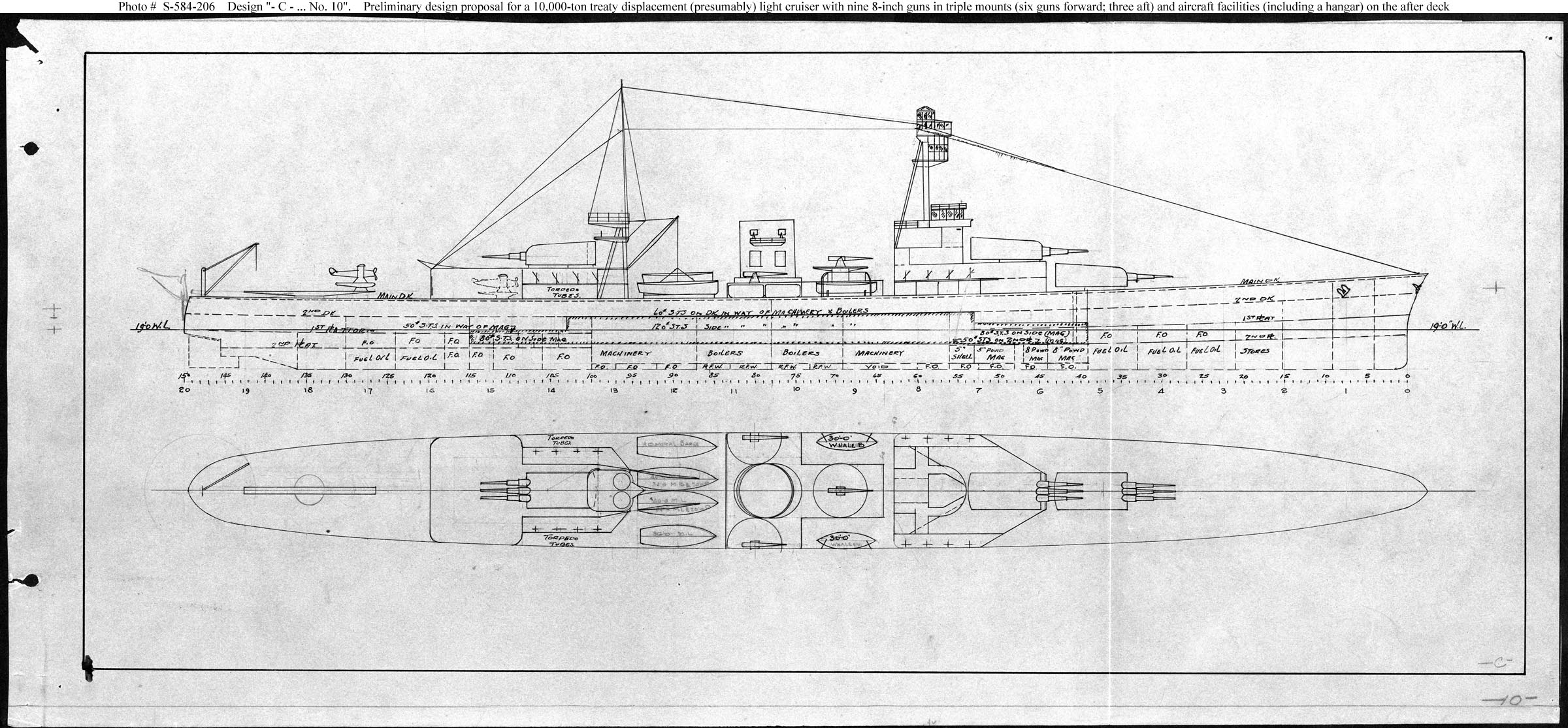

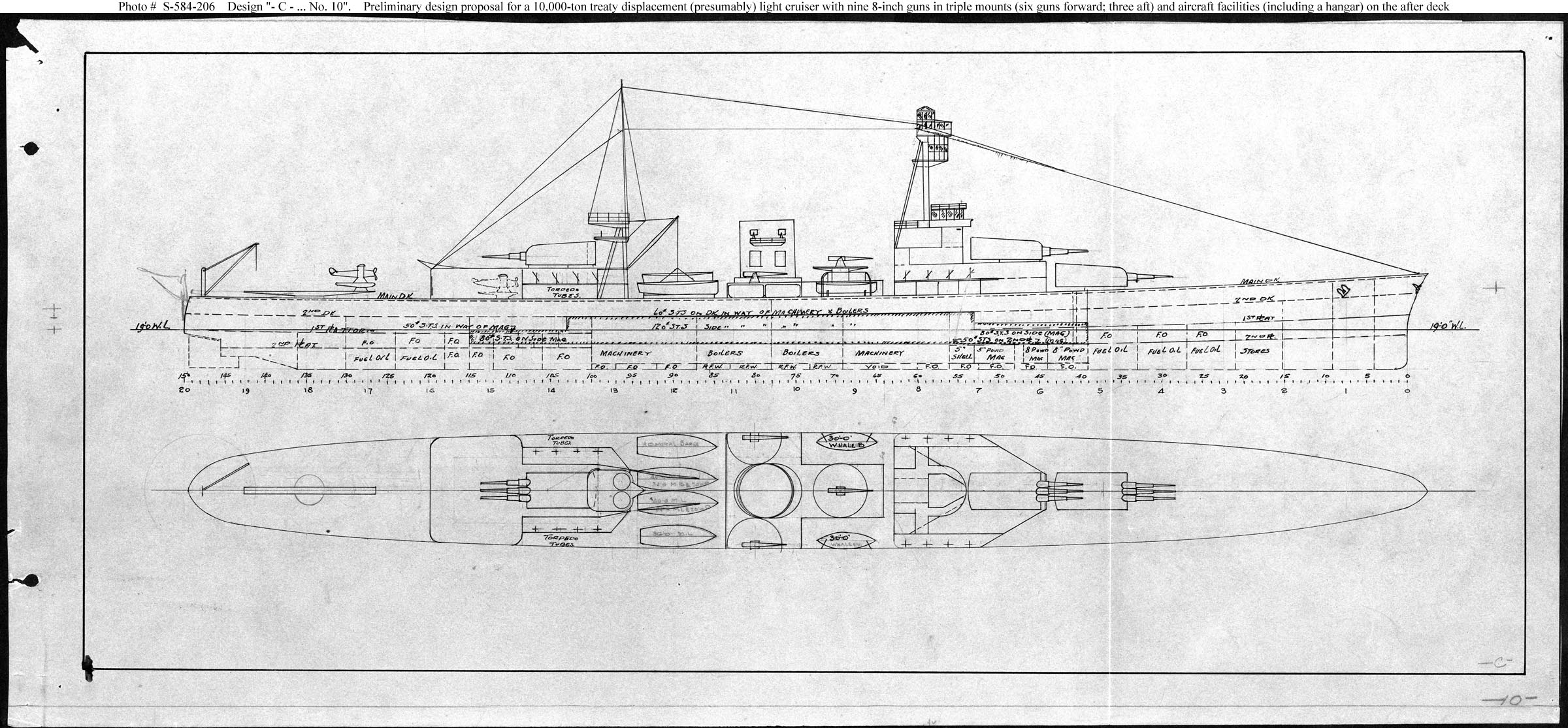

N°10, same, design C. As the first, there was an aviation hangar in front of the superfiring aft “X” turret, the space taken by an alternative “Y” deck level turret. The hangar was large, reaching both sides, so fit to to house four planes, wings folded, with room to spare. A single axial catapult was used for the launching, and poop crane for recovery.

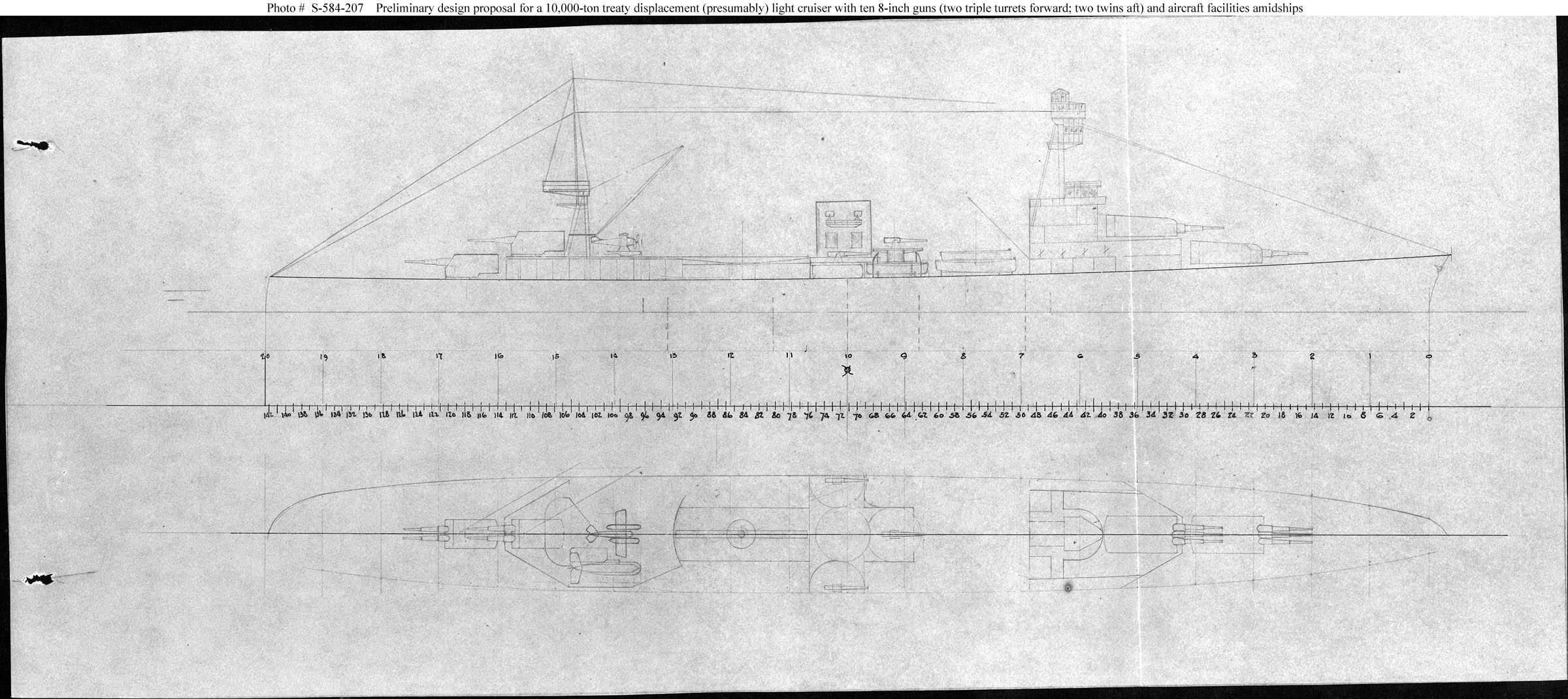

Preliminary design C, 10 guns. A more conventional approach with planes recentered aft of the funnel and axial catapult. The aft mainmast was based on the hangar.

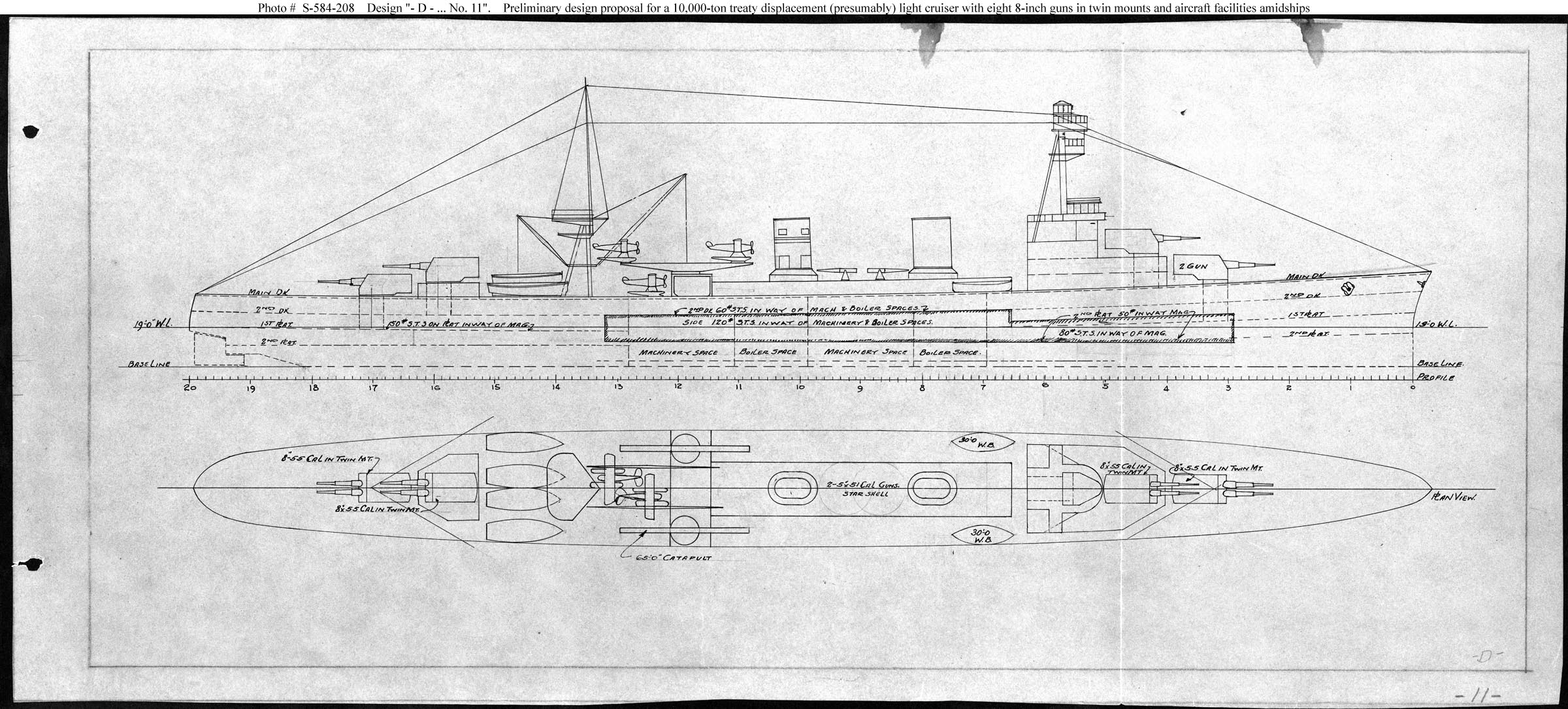

Preliminary design D, 8 guns, same idea but lighter turrets and two side catapults. No hangar, the planes were apparently parked below and in-between, in open air. The secondary armament had a very poor arrangement and armour was limited to the forward section.

April-May 1925 final design

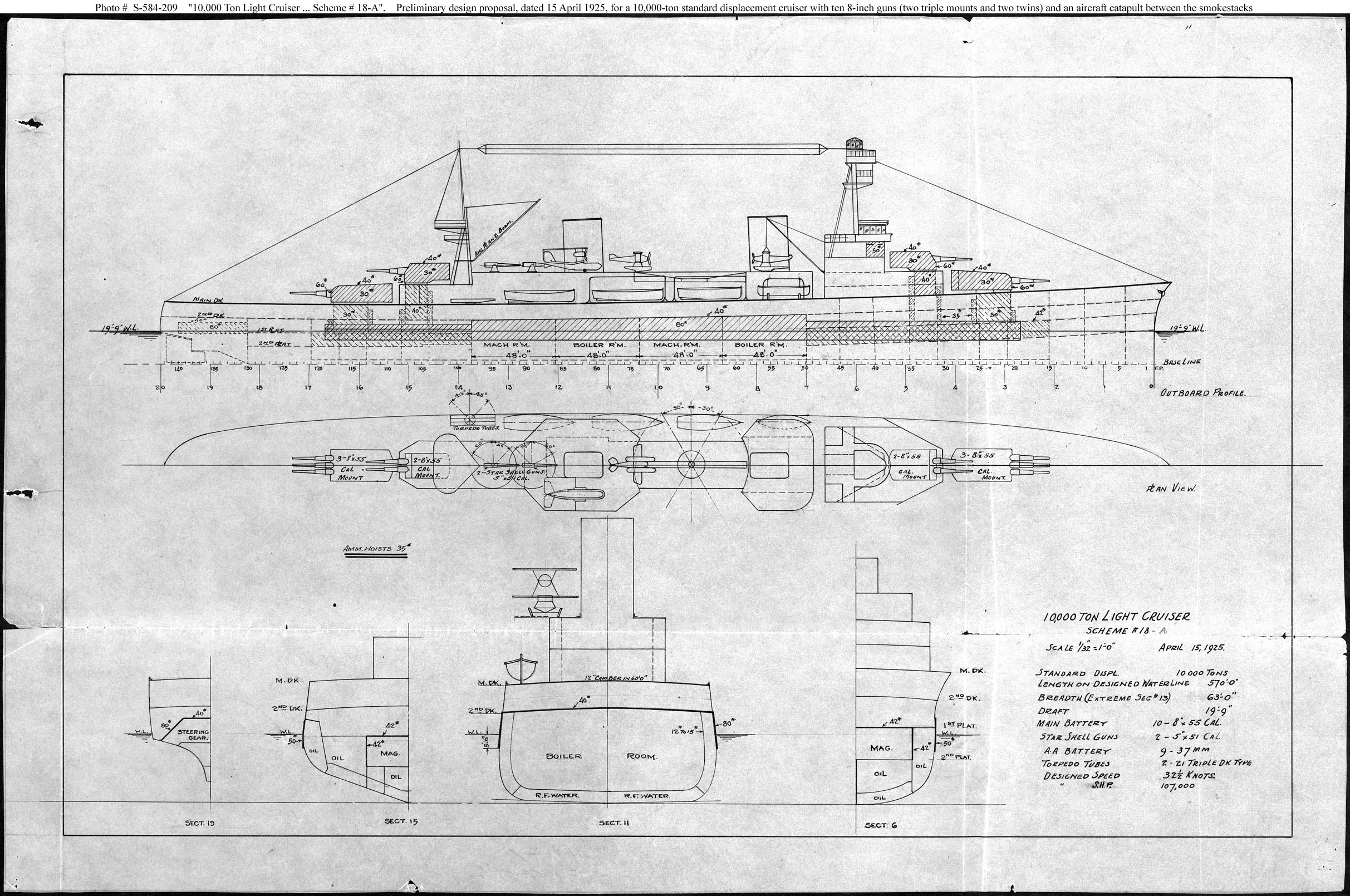

Design Study #7, 10 guns, 15 April 1925

Design Study Scheme #18B, 21 April.

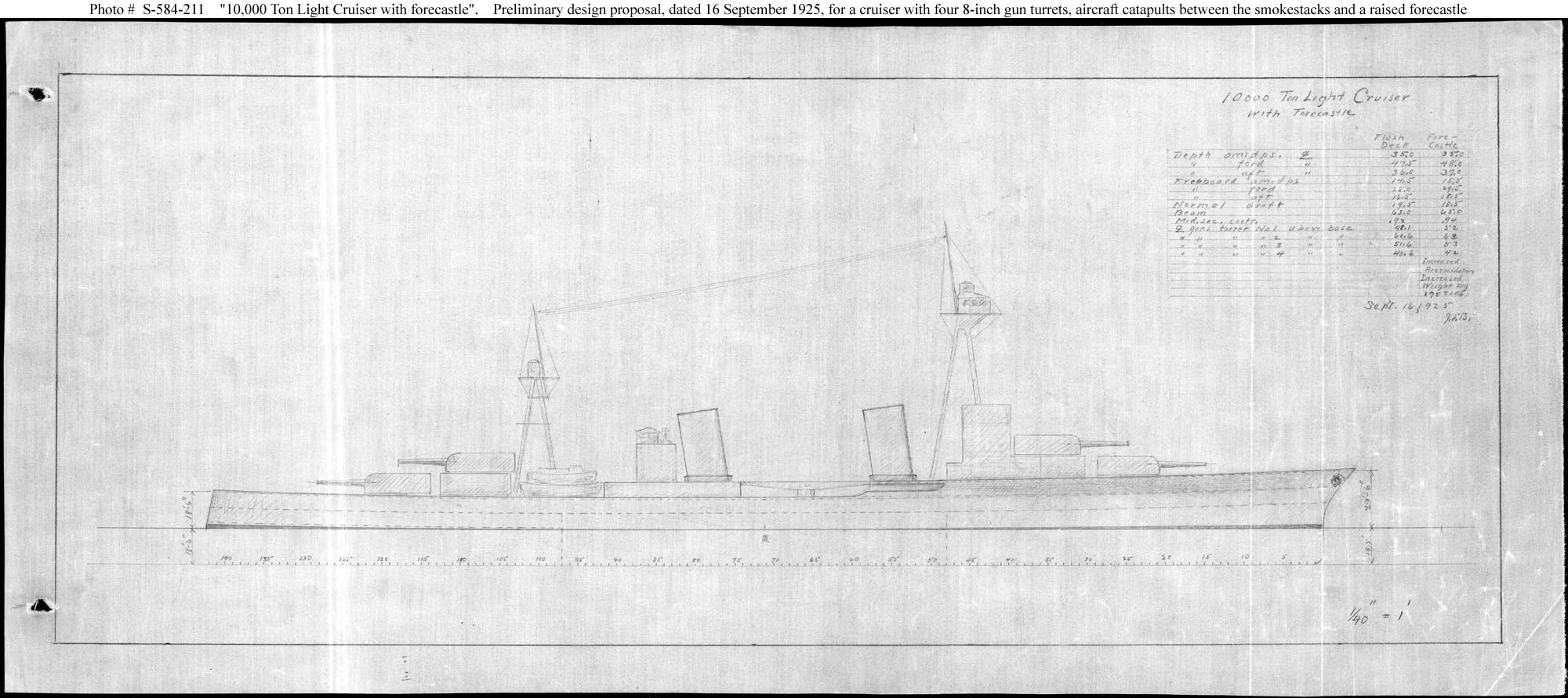

Late 1925 forecastle design

September 1925 Raised forecastle variant

This one was the blueprint in fact for the second class authorized by Congress, of six improved cruisers derived from the Pensacola. Their design proceeded from the feeling within C&R, that the Pensacola design sacrificed too much for the maximum battery. Although the treaty tonnage forbade any great improvement in protection, it was still possible better balance firepower and seagoing characteristics. Trading freeboard for extra guns would reveal itself a quite a heavy priced to paid but it was unknown at the time. Bu reducing the armament to 9 guns the beefits were considerable in displacement, armor area, as well as volume. They also aimed at improving aircraft arrangements, habitability and stability.

1st generation cruisers design

Both the Pensacola and Northampton classes nicnamed “Treaty Tinclads” had been compromised designs largely determined by the need to stay barely within Treaty limits. So they came out grossly underweight, with 900 tons underweight fo the first class, 600 for the Northamptons. The fault fell squarely on C&R, which preliminary Design’s were rather conservative, corrections being too late for the Northamptons. Despite the forecastle the next Northamptons kept the same main issue, having an excessive metacentric height.

Roll was short and deep and a case of very heavy snap rolling was susceptible to break the topmast, essential at the time for long-range radio. This in fact happened when USS Salt Lake City was en route from New York to Guantanamo early in 1931. The first preventive measures were the addtion of anti-rolling tanks on both USS Pensacola and USS Northampton. These were not interconnected, but open to the sea with a vent pipe to managed pressure. Complaints of weak sternposts, and excessive vibration aft attributed to countless weight saving measure in the structure, was solved by structural stiffening, no longer a problem in 1940 a the treaty limits were discarded. In fact the hull seemed so light it was believed a full broadside would cause serious damage.

By practice, Captains avoided it. Nevertheless these “Treaty tinclads” replaced the older battleships used with the Scouting Force, and they were versed as escorts for the new fast carriers, in independent task force operations. They also took the role of fleet flagship, liek the first three Northamptons. The succession was incarnated by the Portland class, considered a second generations, slower, roomier, but more stable, sturdier and better protected. This was pushed further with the New Orleans Class, before effects from the Geneva Summit and London Naval Treaty of 1930 were felt in the USN and trigerred a third generation, this time of light cruisers (The Brooklyn class) which inspired both the wartime Cleveland and Baltimore.

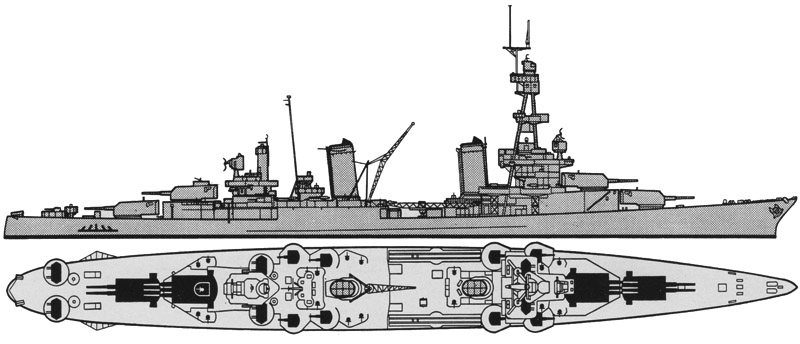

wow’s rendition – Pensacola 1944

wow’s rendition – Pensacola 1942

Definition of the artillery

The British, the French and Italians chose the configuration in twin turrets. However the Americans from the beginning, confident in the design of triple turrets initiated for their dreadnought during the war, chose to adapt it for their cruisers, while maintaining a configuration in four turrets. The Admiralty had thus chosen a compromise with the most powerful artillery possible (ten guns) on a strictly limited tonnage. Like other navies, they also choose welding assembly techniques to save tons of steel rivets.

But these choices were paid later in practice and throughout their career. Indeed, triple turrets – the most powerful – were mounted in superfiring position due to size constraints fore and aft. In addition the tripod military masts were tall and heavy, the aiming bridge and conning tower all played a part on the ships being dangerously unstable. With a limited bream and a lightly built hull, this caused dangerous overweight in the heights and the Pensacolas. Their list was so excessive when steering that rapid evolutions and hard turns were deliberately limited in operations. In addition their pitch and roll were high due to a short “flush deck” hull, narrow and overloaded forward, causing them a “nose down”, plowing in heavy weather.

Final design details

Hull & protection

Her hull was approved in the final draft as 570 ft (170 m) in waterline lenght and 585 ft 6 in (178.46 m) oveall. It was relatively wider at 65.0 ft (19.8 m) with a ratio of 8,9, so debunking the idea she could have been too narrow for comfort. It was even better than the late generation ships of the Brooklyn or Cleveland class (1/10). Her draft was important due to her flushdeck hull, lacking buoyancy, at 19.5 ft (5.9 m) when fully loaded. In all, she also displaced 9,100 long tons (9,246 t) standard, so well below the limit, with the idea of testing how far she could be armed on that displacement (and perhaps hoping to upgrade the design to four triple turrets as first envisioned, reaching the 10,000 tons with no room for improvements). She displaced 11,512 long tons (11,697 t) fully loaded, but this would change over time and refits. Their design was made the utmost economy (costing $11 million apiece), using welding instead of rivering to spare extra weight.

Protection-wise, as the first of the “tin-clad” generation, armour protection was weak to say the least: Her Belt started at 2.5 inches out of the barbette zone and 4-inch (64–102 mm) amidships, with a connected slope of the same thickness to the armored deck. So she could stop in theory destroyers rounds (5-inches), but hardly 6-in light cruisers ordnance. The armored deck range from 1 inch (25 mm) to 1.75-inch (44 mm) over the most sensitive steering room and ammunition magazines. The turrets were weakly protected, ranging from 0.75 in (19 mm) at the back and roof, to 2.5-inch (64 mm) for the front plates. Below them, barbettes were supposed to be partly protected by the deck, and 0.75-inch thick only. The front only conning tower received 1.25-inch (32 mm) walls. The underwater protection comprised a compartimentation for the boilers rooms and turbines, with the usual multiple side compartments below the belt to withstand a torpedo hit. Pensacola survived indeed to a “Long lance” at Tassafaronga.

Powerplant

She was given four Parsons Steam turbines with reduction gear, mated on four screw propellers for more flexibility, with steam pressure variability between the inner (cruise) and outer shafts, as common practice at the time. They were placed in two successive enclosed compartments, with the boilers rooms following behind. Each comprised four Forster-Wheeler boilers (so 12 in all), for a total output of 107,000 hp (80,000 kW). Top speed as designed was 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph).

For the range, these cruisers carried 1,500 short tons (1,400 t) of fuel oil in peacetime*, enough for 10,000 nmi (12,000 mi; 19,000 km) at 15 knots (17 mph; 28 km/h). Capacity could be in theory augmented in wartime, filling some void compartments along the belt.

Armament

Main Guns

10 × 8 in (203 mm)/55 caliber guns (2×3, 2×2): 8″/55 (20.3 cm) probably of the Mark 10 type. Mark 9 was used by the Lexington class (CV-2), Mark 11, 13 and 14 were used by the Northampton and Portland, New Orleans and Indianapolis. They were originally designed to carry the “super-heavy” AP projectile planned in 1923, but never adopted because of loading issues. Therefore fast reload was not the priority and they were criticized for their poor rate of fire (3 rpm). First designed in 1922, chamber volume was 5,300 in3 (86.8 dm3). They fired 260 Ibs rounds (118 kg), AP, SP, HC and HE types. Muzzle velocity was 2,800 fps (853 mps) and appox. barrel life 715 rounds.

It’s likely both cruisers had them relined or replaced during refits due to heavy wartime use added to peacetime and wartime gunnery exercises. At 33.8° their range was 30,000 yards (27,430 m). Penetration at that range was about 4.0″ (102 mm) of deck armor and 3.0″ (76 mm) of side armor. At 9,000 yds, it went up to 10.0″ (254 mm) of belt armor. In addition these earliest weapons systems were officially classified as “twin” and “triple mounts” rather than “turrets”: Indeed their handling rooms was directly below the gunhouse, they did not have a rotating stalk. The barrels were solidary, no independent elevation. To avoid damage however all three barrels fired with a slight lap to avoid simultaneous blast that could damage the whole turret and light hull structure around. This resulted in a rather high dispersion pattern also. See also: http://navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_8-55_mk9.php.

Secondary Guns

8 × 5 in (127 mm)/25 caliber anti-aircraft guns. It was on both cruisers the 5″/25 Mark 10 model. This very famous piece of ordnance was worked on since 1920 an introduced in 1925 as a dual purpose, seeing service with virtually all battleships and cruisers up to the Colorado and Brooklyn (CL-40) classes. It will be treated as a standalione in great detail as part the weapons tech section in the future. It had an appreciable 15-20 rounds per minute rate of fire, and was provided with around 200 shells, HE, AP, AAC and VT AAC plus illumination. Barrel life was around 3,000 rounds and ceiling/range 27,400 feet (8,352 m)/14,500 yards (13,259 m). On the deck, the eight guns were located in individual semi-sponsons on the upper deck of the forward bridge battery superstructure and abaft the aft funnel. They ate a lot of space that could have been used by quad 40 mm Bofors, which were few as a result when modernized. See more: http://navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_5-25_mk10.php.

AA Guns

At first, none were installed (..) and instead, the cruisers just had the utility two 3-pounder 47 mm (1.9 in) saluting guns. They could send flares and smoke rounds as well, but were harly capable of shooting down any incoming aircraft. The 5-inches were intended for dealing at long range with incoming bombers.

This did not last long as in 1939 they were given four quad 1.1 inches (28 mm) or sixteen “chicago piano” mounts, and around sixteen twin 0.5 in cal. Browning M2HB in 1941 located in the fighting tops of the fore and aft tripod mats. Neither were found very efficient (although both had kills with them) and at the first opportunity they were rearmed with 40 mm Bofors and 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns (see wartime modifications). In all, they went in 1944 with four quad 40 mm (32 Bofors) located abaft the aft pole mast and on the aft deck. Six 20 mm Oerlikon guns were also provided located in sponons pairs abaft the bridge, and aft superstructure. In 1944 both cruisers were armed with two quad 40mm/56 Mk 1.2 and eight or nine 20mm/70 Mk 4 Oerikons and in 1945 on Pensacola, 2×4 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, eighteen (9×2) or twenty 20mm/70 Mk 4 AA, even six quad Bofors in 1946 as four 5-in were retired.

Torpedoes

As customary for cruisers at the time, the Pensacola class was fitted with two triple 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes banks. They were eliminated in 1941 already.

Fire control

One particular of the design which also cause staility issues was their tall fire control director. It was mounted on top of the fire direction lookout tower, installed on a massive, and tall tripod mast. There, was located the main artillery Mark 18 fire director atop the main mast. Why so high ? At the time, it was deduced from “below the horizon” imperatives for the limited sights of the time. The higher the better. This height was calculated in proportion of the range. The same principle was applied to the Omaha class which had a lower range, lighter artillery. Over the years of course, better optics and better use of airborne artillery spotting prevented the use of these tall masts. There was a secondary fire director installed on the bridge below, used for the secondaries. A telemeter installed on the radio room behind the aft funnel managed the torpedo tubes. The cruisers also had three main projectors and two light morse projectors. Radars were installed from 1943, on USS pensacola, a CXAM radar and and SG, SK, Mk 3, Mk 4 radars but no CXAM on Salt Lake City. In 1946, the SC, SG, Mk 3, Mk 4 radars were still in use.

Onboard aviation

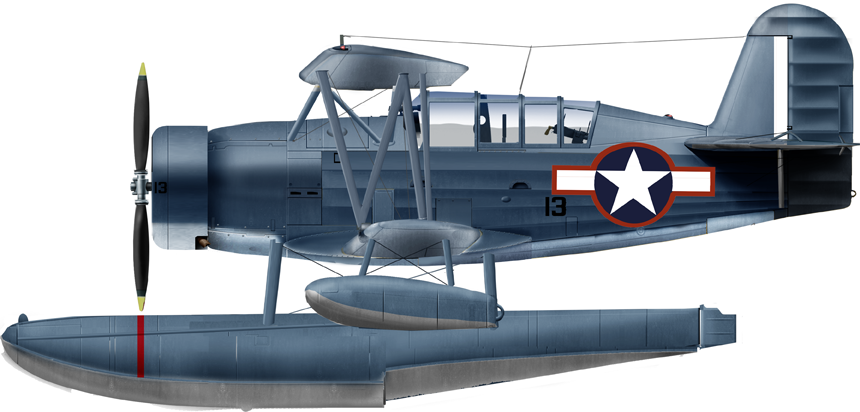

As per the photos shown, the four reconnaissance and spotter floarplanes were likely:

-Loening OL (1923), introduced in 1925 and probably in service until 1929.

-Vought O2U Corsair (1928), replacing the OL until 1935 or 1936, then replaced by the Seagull.

–Curtiss SOC Seagull (1934) Until 1943 (illustration).

-Vought Kingfisher from 1943 onwards until decommission.

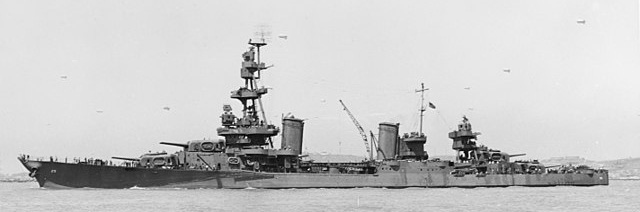

The USS Salt Lake City in 1939.

Refit blueprint of the Pensacola class 1941

The USS Pensacola in March 1945, in support of Okinawa. Note the evolutions with the original design

CA-24 wore 33/10D beginning in October 1943 based on 10/11/43 ComServPac letter #0937 to the BuShips (which replaced and fusioned BuC&R & and BuEng 1940) which assigned camouflage Designs to ships assigned to the Pacific Fleet. Later in May 1944 CA-24 was painted in 32/14D at Mare Island using the 32/14D drawing that had been used for CA-25.

USS Pensacola 1939 |

|

| Displacement | 9,100 t standard, 11,500 tonnes fully loaded |

| Dimensions | 178,5 x 19,9 x 5,9 m |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 4 WF boilers, 107,000 hp. |

| Speed | 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) |

| Range | 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Armament | 2×2, 2×3 8 in, 4x 5-in, 8x 0.5-in, 2×3 21-in TTs, 4 seaplanes |

| Armor | Turrets 5.5-in, belt 2-in, CT, casemate 2-6-in, deck 2-in. |

| Crew | 631 |

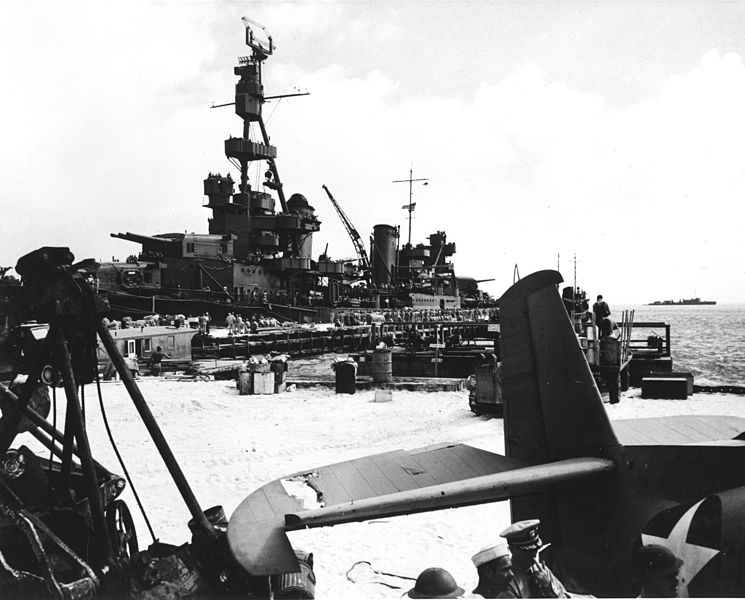

Wartime Modifications of the class

In the end this Pensacola class appeared as quasi-experimental. Pensacola’s sister-ship, USS Salt Lake City was launched in 1930 and completed in 1931. Both ships received additional counter-keels in 1939 to improve stability, then in 1942 their superstructures were curtailed and lightened. In 1944 the massive tripod masts were removed entirely, a new lighter quad structure mounted. They received a new radar pole, new fire control systems, and a powerful AA artillery complement. This solved some of their deficiencies and they participated in major pacific operations before being removed from active service in 1947. They were essentially a first test of how not to do it, that defined the next class, the Northampton, largely derived from the alternative, not adopted forecastle variant of 1925.

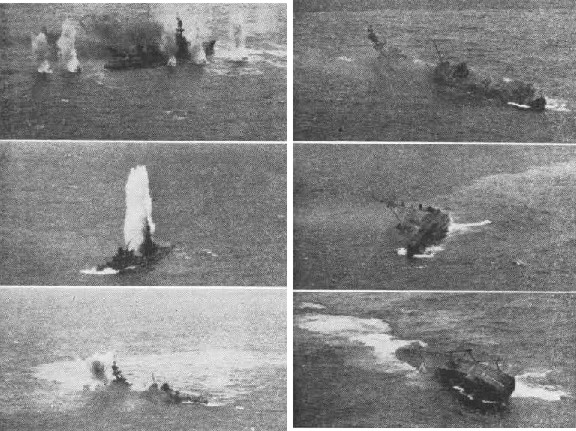

Modifications for Operation Magic Carpet in 1946 included the removal of four single 5-inch gun mounts, two quad 40mm mounts and four twin 20mm mounts but the main turrets stayed in place. Both were utilized as targets (Bikini) fitted with many markers and sensors to measure all aspects on the blast on a warship.

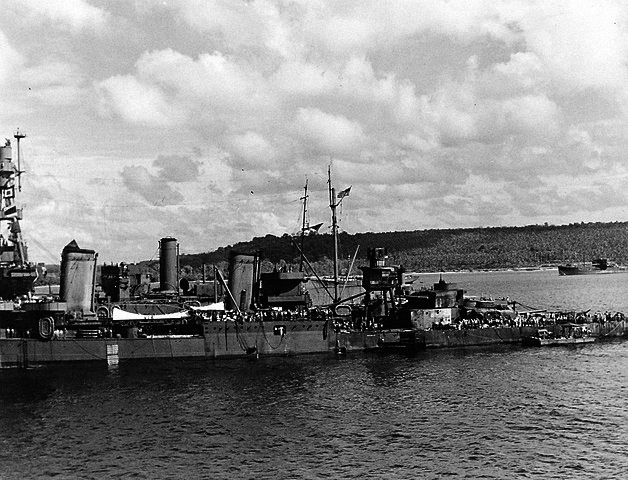

Comparison between the Pensacola sister ships and USS New orleans at pearl Harbor 31 October 1943. Their huge tripod masts were retired only in 1944.

USS Salt Lake City 1944 |

|

| Displacement | 11,744 t. standard -14 130 t. Full Load |

| Armament | Same main armament, 6×2 5-in, 5×4 40mm, 10x 20mm |

| Crew | 690 |

Overall impression

How they compared to the County class ?

Two more guns, a slightly better speed (0.5 knots difference), similarly weak protection, buy the Counties had a larger hull making them more stable and roomy, and about the same range.

How they compared to the Furutaka class ?

The latter had a much lower displacement at 8,700 tonnes, almost half the firepower with just six 8-in guns, a better speed at 33 knots, and a light, but more effective protection, upt to 3-inches and integrated as part of the structure as designed by engineer Hiraga.

USS PENSACOLA, like fast standard BBs of WW1, favored speed and firepower over protection, and they were very lightly armored, even by cruiser standards. They could baely resist to 5-inch gunfire and the great irony was that despite tonnage limitation they came out grossly underweight, even after last-minute changes. Full load reached 10,666 tons eventualy, so 900 tons underweight. Both classes excessive metacentric height caused a roll which was both short and deep, causing a disconcerting motion, combined with a heavy snap rolling, an issue solved later by adding anti-rolling tanks, not interconnected, as each was instead open to the sea with a vent pipe. Weak sternposts and excessive vibration aft at high speed were also later cured by structural stiffening. Firin a full broadside was also avoide in operation for the same reasons.

Nevertheless, both cruisers brought a new capability to the fleet, and replaced elderly battleships of the Scouting Force. They soon served also as escorts for the new fast carriers, something the old Battleships were unable of due to speed issues. The London Treaty of 1930 changed their category, from class A Heavy Cruisers (CA) as having guns over 6.1 inches, versus B Light Cruisers (CL) beyond 6.1 inches and in July 1931, 8-inch gun cruisers were redesignated CA-24 and CA-25.

In 1943 USS Salt Lake City was the oldest heavy cruiser the U.S. Navy, and kept a streamlined beauty but ungainly silhouette the Time Correspondent Bob Casey fondly nicknamed “Swayback Maru”. Never really hit hard in action she lacked publicity as she was never sent home for repairs, but by March 1943 high-ranking officers were willing to concede that her performance made her the number one U.S. cruiser of this war. Indeed Salt Lake City had been in more engagements than any other American warship and Japanese communiques wrongly declared her “sunk” twice, or left burning. Not bad for “protoype cruisers”.

Sources

Books

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-47

Silverstone, Paul H (1965). US Warships of World War II. Annapolis

Sites

http://navalmarinearchive.com/research/cruisers/cr_navsea.html#LinkTarget_8410

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1173/

http://www.usndazzle.com/ship.php?id=9

https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/019.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Pensacola_(CA-24)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Salt_Lake_City_(CA-25)

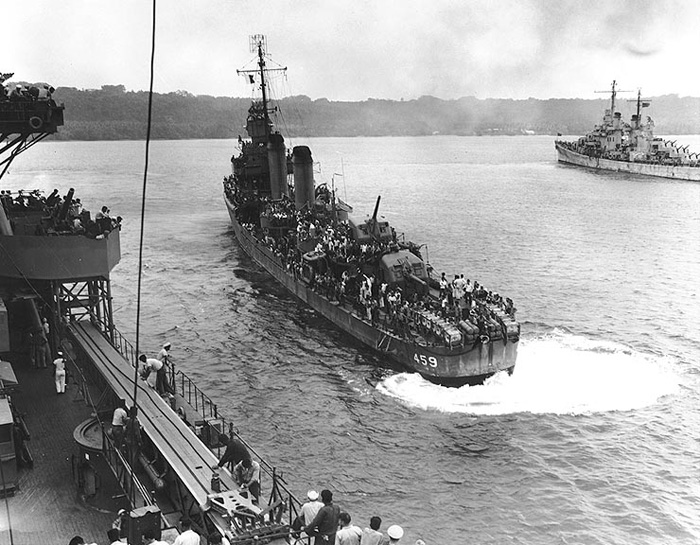

USS Pensacola alongside USS Vestal after the battle of Tassafaronga, 17 December 1942

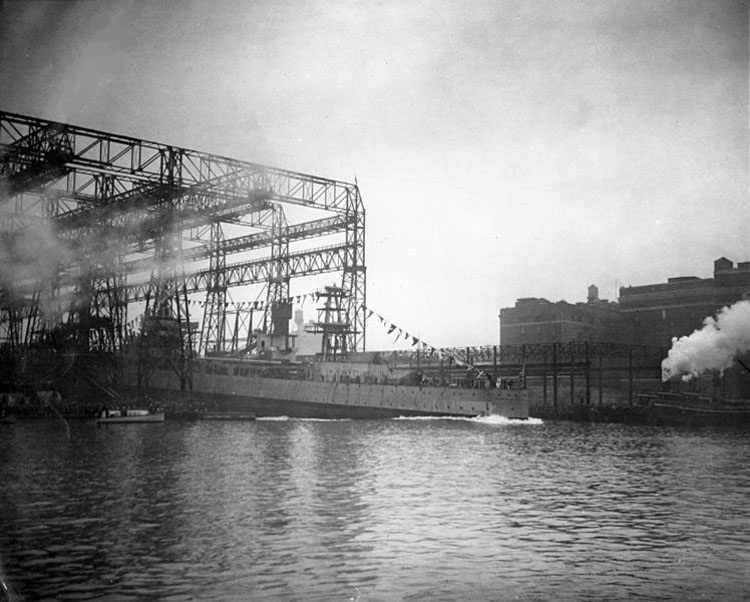

USS Pensacola (CA 24)

USS Pensacola (CA 24)

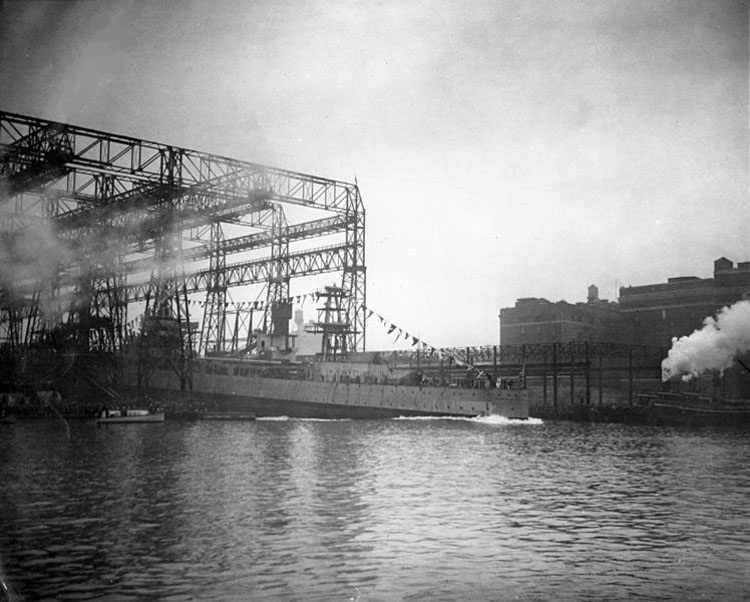

Laid down by the New York Navy Yard on 27 October 1926, she was launched on 25 April 1929, commissioned on 6 February 1930, supervised by her first captain, Alfred G. Howe. She departed New York on 24 March 1930, bound for the pacific, transiting though Panama and heading first for Callao, Peru, and Valparaíso in Chile for her shakedown cruise, then back through Panama to New York on 5 June. Until 1934 she stuck to the Atlantic, training along the eastern seaboard, from Newfoundland to the Caribbean Sea, but also making yearly Panama transits to join the combined Fleet for battle practice, from California to Hawaii.

On 15 January 1935 she depated Norfolk for the Pacific Fleet via San Diego, reached 15 days later. She took part in a Fleet problem off Hawaii but heading north to Alaska and the Aleutians. She was back to the Caribbean Sea and returned on 5 October 1939 to Pearl Harbor. As she was there for maintenance in 1940, USS Pensacola was one of the first six ships receiving the new RCA CXAM radar. Maneuvers followed between Midway and French Frigate Shoals, and then further east to Guam.

Early Pacific Operations

USS Pensacola departing Pearl Harbor since the 29 November 1941, in the “Pensacola Convoy” bound for Manila. After the 7 of December, this convoy was diverted to Australia, Brisbane, reaching it on 22 December. She was back to Pearl on 19 January 1942 and back at sea on 5 February, patrol the approaches to the Samoan group. On 17 February 1942, she met there with Carrier Task Force 11 (TF 11), USS Lexington. She headed for Bougainville Island, her AA gunners helping protect her group against waves of IJN bombers on 20 February while USS Lexington’s CAP claimed no less tnan 17 out of 18 attackers.

This escort role went on also during the offensive in the Coral Sea, until joined by USS Yorktown’s own TF on 6 March 1942, both steaming for Papua New Guinea, launching an air strike on March 10th over the Owen Stanley Mountains on the advanced base at Salamaua and Lae. It caused heavy damage and the fleet headed for Nouméa, New Caledonia whic was at that stage an early replenishing base. USS Pensacola teamed next with Yorktown alone until 8 April before going back to Pearl Harbor (21 April) for the crew’s rest and replenishment and maintenance. She carried personal of the Marine Fighting Squadron 212 to Efate (New Hebrides Islands) ad went back, affected with USS Enterprise on 26 May this time.

Midway

She departed Pearl with USS Enterprise on 28 May, meeting on 2 June the main carrier force northeast of Midway with TF 17. The battle of Midway commenced, leaving four carriers in flames. USS pensacola was present to see Yorktown hit by three bombs ans she raced to screen her and help her if possible. But even though she was close to her when escorted back to Pearl, a submarine went unnoticed and torpedoed her. Dead in the water, Pensacola tried to take her in tow while assistingin shooting down four incoming torpedo bombers. Despite of all these she could not prevent USS Yorktown to take two more torpedo hits amidships. fter she was abandoned and evacuated, USS Pensacola made it back to USS Enterprise’s screen, in hot pursuit of the Japanese.

Battle of Santa Cruz

She was back to Pearl Harbor on 13 June, but departed soon, on 22 June, with USS Enterprise again and 1,157of the Marine Aircraft Group 22 to Midway. After patrols and training back in Hawaiian waters she departed again in August for the Solomons, screening a combind air group with USS Saratoga, Hornet and Wasp. This were submarine-infested waters and soon Saratoga was hit on 31 August and Wasp on 15 September (which sank).

pensacola-after-battle-tassafaronga

Launch_of_USS_Pensacola_Brooklyn_Navy_Yard_1929

USS_Pensacola_transiting_the_Panama_Canal_circa_1930

USS_Pensacola_Massacre_Bay_Attu_Island_9_June_1944

USS_Pensacola_at_sea_with_tugs_14_October_1943

USS_Pensacola_at_the_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard_3_July_1945

USS_Laffey_with_survivors_of_USS_Wasp_September_1942

USS_Pensacola_CA-24_being_sunk_10_November_1948

USS Benevolence in Bikini lagoon, 1946, Salt Lake City is seen in the background.

Resplenising at Nouméa on 26 September she was back to the Solomons with USS Hornet on 2 October. She protected her during the Santa Isabel–Guadalcanal strike. On 24 October Hrner combined forces with USS Enterprise by that time, the last CVs operational in the Pacific. They steamed to intercept approaching ships spotted in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area, relocated later on 26 October.

During the ensuing Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands Pensacola never saw enemy ships but her AA gunners were in high alert and she helped to fight off a coordinated dive/torpedo attack, badly damaging Hornet. Soon, 24 dive bombers attacked USS Enterprise, also damaged, but thanks to her damage control parties, she survived, even taking on board the air group of the crippled Hornet, which sank later. On her side, USS Pensacola took on board 188 survivors from USS Hornet later landed at Nouméa on 30 October. The price to pay prevented a Japanese massive reineforcement of Guadalcanal.

Guadalcanal’s hell

USS Pensacola departed Nouméa on 2 November, escorting transports with Marine reinforcements to Aola Bay in Guadalcanal. She still covered USS Enterprise in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (12–13 November) and returned to Espiritu Santo to be reassigned to TF 67 (Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright). On 29 November, she sailed to intercept a Japanese “Tokyo Express”, destroyer-transport force located and expected to arrive off Guadalcanal the next night. Just before midnight, on the 30th, the US fleet transited Lengo Channel, headed past Henderson Field. Meanwhile, the Japanese task group steamed on a southerly course, west of Savo Island and entereing the future “Ironbottom Sound” also called “the slot”, an infamous trait of water with hights on both sides hiding ships even with radars.

Battle of Tassafaronga

The two opposing forces clashed off Tassafaronga, hence the name. In this first and famous battle of the Guadalcanal campaign, US destroyers launched torpedoes as soon as they located the Japanese, just as the enemy range fell to 5 miles (4.3 nmi; 8.0 km) of the cruiser formation. Gun flashes and tracers added to star shell, creating a surrealist picture in this inky darkness, revealing both forces and hell broke loose. The DD IJN Takanami was hit many times and alight soon, then exploding. USS Minneapolis took two ‘long lance” torpedo hits, blasting her bow downward, leaving her forecastle awash. Howeer she still was operational and fired on. USS New Orleans close behind was hit by a third torpedo, ripping off here whole forward section, almost to the first barbette bulkhead.

USS Pensacola then turned left to prevent a collision with the two damaged cruisers ahead but she was unfortunately also silhouetted by the burning ships, so she came immediately under fire from the whole Japanese line. In addition she took one of the 18 torpedoes launched by Japanese destroyers, struck just below the mainmast, portside. Her engine room was flooded and she had three gun turrets cut from power. He oil tanks also ruptured, bleeding out to a black pool around, while her mainmast became a torch, engulfing the poor watches in the top fire control director. USS Honolulu, next in line, saw this and maneuvered sharply at 30 knots, behing, fring rapidly as she escaped. At last, USS Northampton took the remainder of torpedoes, two stricking her and damaging her so badly, she was not even capable of replicating and was soon abandoned, buning fiercely. The surprise was total and for the first time, Japanese Type 96 Torpedoes shown their amazing potential.

With the oil pool around soon in flames, Pensacola was soon engulfed aft, where ammunition was located, which soon exploded. But inlike other cruuisers that fateful night, she was saved only thanks to the truly heroic, supreme effort of her skillful damage control parties. Men of steel in a tin-clad cruiser. This really was a hellish picture as the cooked-off 8-inch projectiles in her Number 3 barbette exploded one after the others, inside a red hot well that was this part of the ship, also cooking alive turret servants. USS Pensacola nevertheless, amazingly escaped while still being alight, and was able to limp back to Tulagi, arriving there still with multiple fires burning. It would take 12 hours to save her, and she was still smoking in placed the folliwingg evening. The captain ordered a macabre crew account, which was seven officers and 118 men dead, one officer and 67 men were more or less badly injured. Many would later die of their 3rd rate burns despite the care, in great pain.

To avoid being spotted by IJN aviation she was heavily camouflaged, as part of the island wit nets, palm trees, paint and everything possible in between by the crew, working along the clik with those repairing her. Tulagi Harbor provided facilities for the rest, and she was at least able to steam to Espiritu Santo in New Hebrides for more torough, but still emergency repairs. This started on 6 December, hemped by the fleet workshop USS Vestal, until 7 January 1943, at least leaving the traumatized crew some Christmas rest. She sailed via Samoa to Pearl Harbor, arriving on 27 January, repaired entirely and prepared for her next operations.

5in guns_USS_Northampton_firing_on_Wotje_1_February_1942

Tarawa and the Marshalls (1943-1944)

On 8 November 1943, USS Pensacola was at last out of the drydock. Meanwhile her crew served in other ships, and she gained a new one. After post-repairs trials and training, she sailed as part of the Southern Attack Force and took position for a shelling operation on 19 November on Betio and Tarawa. She fired 600 times, blasting away coast defense guns and hammering all visible enemy beach defenses, facilities and miradors, deadling with blochaus with her 8-inches AP shells.

During the landing at Tarawa on 20 November she stayed close to the carriers, provided AA cover and this first night, repelled an attack by IJN torpedo bombers, notably USS Independence. She headed next to Funafuti, Ellice Islands. For two months in December to January 1944, she stayed there screen the aircraft carriers during reinforcements and supply operations to the Gilbert Islands Operations.

On 29 January 1944, she shelled both shore installation and merchant traffic in the Marshall Islands. She notably bombarded Taroa by hersefl (Eastern Marshalls) and destroyed its airfield runways and seaplane ramps but its ammunition depots, gasoline tanks, workshops, and administrative buildings on the next island of Wotje. Marines and Army troops landed on Kwajalein and Majuro Atolls on the 31 and she provided close cover. Her Marshall Islands went on until 1 February with the seizure of Roi and Namur and USS Pensacola returned piunding Taroa in Maloelap Atoll until 18 February (Eastern Marshalls). She respenished at Majuro and Kwajalein and patrolled the approaches of the Marshalls to prevent any IJN reinforcement. She later screened the fast carriers in the Caroline Islands from 30 March to 1st April and shelled defences on Palau, Yap, Ulithi and Woleai.

The Kuriles (Summer 1944)

On 25 April she left Majuro for Pearl Harbor and Mare Island, reaffected to the “cushier” Northern Pacific. She arrived in Kulak Bay on 27 May for the Aleutian reconquest. On 13 June as part of a task force comprising only cruisers and destroyers she shelled the Japanese airfields of Matsuwa in the Kuriles. On 26 June, she sent 300 shells on Japanese shipping and installations at Kurabu Zaki (Paramushiru To) and back to Kulak Bay on 28 June, resupplied and went on patrolling in Alaskan waters before sailing out on 8 August for Hawaii.

The Marianas & Philippines (Fall 1944)

Pensacola arrived Pearl Harbor on 13 August, resplenished and was back on the 29th to the Marianas. She arrived on 3 September after pounding Wake Island underway. On 9 October she shelled Marcus Island with her sister cruisers and destroyers, emulating the firepower of Halsey’s 3rd Fleet and deceiving the Japanese that the Bonins were next. Halsey instead advanced on the Philippines and meanwhile, the Fast Carriers Force headed for Okinawa and Formosa in the Marianas.

USS Pensacola joined the Fast Carrier Task Force as they were out of Formosa area after liquidating Japanese air power there. She sailed with USS Canberra and Houston to Ulithi and joined the Fast Carrier Task Grou based on USS Wasp on 16 October. As the 7th Fleet commenced operations in the the Philippine, USS Pensacola screen the carriers during their attack on Luzon and the invasion of Leyte, with direct fire to destroy ground defenses from 20 October. As the battle off Cape Engaño developed on 25 October, she raced to catch retiring IJN carriers, but turned south to help rescure Taffy 3, achieving nothing in this collective victory.

Iwo Jima (January-March 1945)

Next, USS Pensacola was seeing in support of the operations on Iwo Jima, hammering the island’s defense dring the night of 11/12 November. She was back to resplenish at Ulithi on the 14th. When prepared to sail to Saipan on 20 November, she spotted a periscope inside the attoll. The supposed IJN submersible was just about 1,200 yd (1,100 m) to starboard, and so her captain took probably the best decision given the circumstances. To not left any opportunity to launch, she maneuvered and run towards the periscope, ultimately ramming and sinking what was revealed later to be a Kaiten midget sub. Four minutes later indeed, she witnessed USS Mississinewa, victim of another Kaiten, one of their rare successes during WW2.

Eventually, USS Pensacola made it to Saipan on 22 November. There she was prepared to cover the invasion fleet on Iwo Jima. Five nights later, there was a night torpedo bombers attack she heped to repel. Departing Saipan on 6 December, she plastered Iwo Jima on the 8th, landing 500 8-inch shells and back to replenish to Saipan. She was back for the same on the 24th and 27th, concentrating at this point on the defences on Suribachi Mountain, the “head of the snake”. She also pounded nearby Chichi Jima and Haha Jima before returuning to Iwo Jima for “detailed strikes” on demand by airborne spotters until 24 January 1945.

Resplenishing at Ulithi on 27 January, she was part of a “gunnery” task force under Rear Admiral B. J. Rodgers, comprising Six battleships, four cruisers (including herself) and a destroyer screen, sailing on 10 February via Tinian.

On 16 February, USS Pensacola concentrated on the northwest sector of Iwo Jima, this time for the proper landings. Lieutenant Douglas W. Gandy, piloted one of her OS2U Kingfisher when hemanaged to shot down a Japanese fighter, quite a rare feat from such type. On the 17th however Japanese heavy gunners of Suribachi zeroed in on USS Pensacola which took six hits. By then she was busy covering the the minesweepers close inshore. She had there officers and 14 men killed, five officers and 114 men injured, the heaviest toll since Tassafaronga. Despite the exensive damage to the superstrctures, specifically targeted, her vitals were not compromised and she resumed shelling operations, this time firing back at the supposed locations, and retired afterwards for repairs.

She was back off iwo Jima on 19 February, starting a vigorious counter-battery fire in direct support of the Marines. This went on day and night, until 1st March silencing the last shore batteries, including one hitting USS Terry recently. Her crew also assisted USS Terry′s wounded before resuming hert bombardment until March, 3th. She was back at Ulithi on 5 March, but reassigned for the next big operation of 1945.

Okinawa

Assigned to Task Force 54 (TF 54) she was underway after a rest and respleneishment on the 20th, in support of the Okinawa invasion, last stepping stone to the home islands. On 25 March she had her 8-inches guns barking to crush shore defences and allow the minesweepers to preparing way for the invasion fleet. On 27 March, one of her lookouts spotted a torpedo wake, port quarter and soon a second on, dead astern. Boh missed, but just. Her 40 mm gunners depressed their mount enough to feveridhly fire on the “fishes”, while the Captain order a hard left, hard right turn in order to have his ship in a parallel course. The first missed her starboard quarter with just 20 ft (6.1 m) to spare, the second 20 yd (18 m) on her port side. Soon another lookhout signalled a persicope, and the Bofors barked at it, until it was no longer visible. Extra lookouts estayed extra vigilant for the next hours, until dark. USS Pensacola resumed her bombardment during the early phased of the invasion, on 1-15 April, before heeading for Pearl Harrbor via Guam, and then Mare Island on 7 May.

Post-war

She was Recheduled for an overhaul, in prevision of the expected Operation Olympic, the invasion of Japan. However instead, she left Mare Island only to be reaffected to the North pacific Task Force, heading to Adak in Alaska on 3 August and dropped anchor just to learn the war was over. On the 31st she departed with Cruiser Division 5 (CruDiv 5) for Ominato in the Northern Honshū, seeing soon “the prize” for all these sufferings, anchoring in the outer harbor of Ominato, on 8 September 1945. She departed on 14 November,with 200 veterans from Iwo Jima onboard, bound to Pearl Harbor and San Francisco. She arrived on 3 December there, taking visitors and leaving the crew on leave in the city. She departed 8 on December for Apra Harbor in Guam, for a second “Magic Carpet” run, taking onboard 700 veterans to San Diego (9 January 1946).

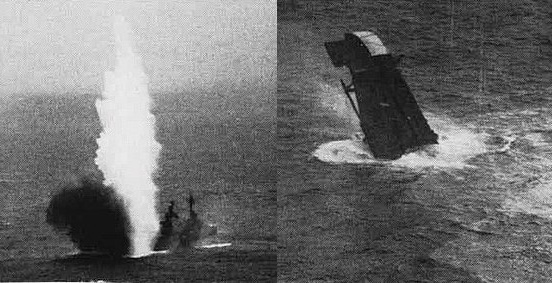

She later was stationed in San Pedro, departing on 29 April with Joint Task Force One in Pearl Harbor. She had been selecteed indeed in preparation for Operation Crossroads, the atomic bomb tests of Bikini Atoll, due to her age and battle damage. Leaving Pearl Harbor on 20 May with a reduced crew and preparations, she reached Bikini on the 29th, placed as a target ship, prepared and abandoned. She survived the 1st “Able” test July as well as the “Baker” 25 July one. On 24 August, she was taken in tow (too radioactive for any crew) for Kwajalein, decommissioned there on 26 August, her hull turned over by using the pumps (it was not difficult !) for radiological and structural studies, then sunk for good on 10 November 1948 off the Washington coast, hardly a life-friendly artificial reef.

USS Salt lake (CA 25)

USS Salt lake (CA 25)

USS salt Lake City at the battle of Komandorski islands 26 march 1943

USS Salt Lake City, CL-25, then CA-28 (First ship named after this “mormon capital” of Utah), was laid down on 9 June 1927 and built at the American Brown Boveri Electric Corporation (New York Shipbuilding Corp.), Camden, New Jersey. She was launched on 23 January 1929, commissioned on 11 December 1929 at Philadelphia Navy Yard with her first Captain Frederick Lansing Oliver taking care of the fitting out process and preparations for service. She made her sea trials and was ready for a first round of training.

Interwar Years

Departing Philadelphia on 20 January 1930, she was ready for her shakedown trials off the Maine coast and an extended cruise from 10 February to Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, and the other classics of the Carribean shakedown cruiser, Culebra in Virgin Islands, but she also went further south, reaching Rio de Janeiro and Bahia in Brazil before gouing back to Cuba and on 31 March affected to the Cruiser Division 2 (CruDiv 2), Scouting Force. She trained next to the cold waters along the New England coast, until 12 September (classic peacetime alternance) and reassigned to CruDiv 5. She operated off New York City and Cape Cod but also Chesapeake Bay.

Originally CL-25, until July 1931 she took the new London Treaty designation CA-25 and returned in the Carribean in the fall of 1931. The next year, she teamed with Northampton class USS Chicago and Louisville for the West Coast, and her first large fleet maneuvers. She crosse dthe canal and was based in San Pedro, on 7 March, reassigned to the Pacific Fleet afterwards, and visiting Pearl Harbor in Jan-February 1933. Attached to CruDiv 4. (October 1933-January 1934) she was drydock for a well needed overhaul at Puget Sound and returned to duty with the same unit, and in May 1934, sailed for New York for the Fleet Review, and back to San Pedro via Panama on 18 December.

1935 saw her training along the West Coast of the Pacific (San Diego-Seattle) and in 1936, in extensive gunnery exercises off San Clemente Island. Departing San predo on 27 April she participated in the first large, complex air-sea-undersea fleet exercizes at Balboa (Panama Canal Zone). Back to San Pedro in June she returned to West Coast training before heading for Hawaii (25 April 1937) and back to the West Coast in May.

Her last peacetime cruise started on 13 January 1939 starting with the Caribbean, also visiting Colombia, the Virgin Islands, Trinidad, Cuba, and Haiti before crossing the canal to San Pedro on 7 April. Bteween 12 October 1939 and 25 June 1940, she made more focused cruises between Pearl Harbor, Wake, and Guam. In August 1941 she visited Brisbane and Queensland in Australia and was back to Pearl Harbor at the end of the year, in state of “quasi war” with Germany in the Atlantic and vivid tensions with Japan.

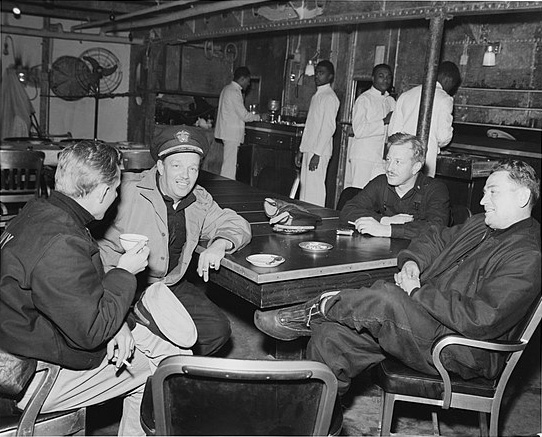

Officer’s mess onboard (Battle of the Komandorski Islands), 26 March 1943

USS_Salt_Lake_City_bombarding_Japanese-held_island_February_1942

USS_Lexington_SaltLakeCity

Allied_cruisers_Brisbane_May_1942

USS_Salt_Lake_City_Dutch_Harbor_29_March_1943

USS_Salt_Lake_City_off_the_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard_California_on_21_June_1944

USS_Salt_Lake_City_off_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard_21_June_1944

USS_Salt_Lake_City_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard_10_May_1943

USS_Salt_Lake_City_early_1930s

USS_Salt_Lake_City_false_bow_wave_c1941

USS_Pensacola_Midway_late_June_1942

Early Operations (1942)

On 7 December 1941, USS Salt Lake City had a new captain, Ellis M. Zacharias. She was assigned to the Enterprise task group just for the Wake Island rieinforcement operation that save her, as she was 200 nmi west of Pearl Harbor when it happened. Scouting planes were launched, hoping to stragglers or even the main Japanese force. Afterwards, they sailed to Pearl Harbor an sundown, 8th of December. There was a tedious night refueling and she was out at dawn, to hunt submarines in the north. Some were spotted on 10 and 11 December, I-70 which was signalled and sunk by dive bombers and the other, engaged by gunfire from Salt Lake City just when turning hard to avoid the coming trails fo torpedoes. Screening destroyers also dropped their depth charge but it seemed the submersible, which plunged when the first 8-in shell landed nearby, escaped. There was a third contact, but it led to no kill. The cruiser was back to Pearl Harbor on 15 December to refuel and be prepared for next operations.

USS Salt Lake City was assigned to Task Force 8 (TF 8), prepared for action until 23 December. She covered Oahu and her task force en route for the beleaguered Wake Island. Wake fell however and she was back to Pearl, then re-routed to Midway and Samoa, where reinforcements were landed.

In February 1942, USS Enterprise’s task force raided the eastern Marshalls: Wotje, Maloelap, and Kwajalein indeed hosted seaplane bases. Shore bombardment was performed meanwhile by the cruiser, which soon came under air attack. Her AA guners claimed their first two Japanese bombers. In March 1942, her TF raided Marcus Island. In In April 1942, she escorted TF 16 en route for the famous Doolittle Raid and was back in Pearl on 25 April.

She was soon reassigned to the Yorktown-Lexington TFs in the Coral Sea, but reached a point some 450 mi (390 nmi; 720 km) east of Tulagi by 8 May and missed the Battle. Salt Lake City next operated as cover for the retiring, crippled USN force, and on the 11th she was steamng in the New Hebrides, then turned eastward, from Efate and Santa Cruz. On 16 May she was back to Pearl Harbor.

Midway & Guadalcanal

After intensive preparations for the expected attack on the Midway Atoll in late May, USS Salt Lake City was affected as a rear guard protection for the islands, but took no part in the battle. Instead, in August–October 1942 she was sent to the south Pacific, in support of operations at Guadalcanal. She escorted USS Wasp, covering the landings of 7–8 August, and later protected air operations from Saratoga and Enterprise, her two Planes in the air to spot possible Japanese moves in the area. On 15 September she witness USS Hornet being torpedoed by Japanese submarines, sinking, and assisted her in rescue operations, taking onboard all pickup up survivors and those by USS Lardner.

Battle of Good Esperance

The campaign in the Solomons was going towards the “Verdun of the pacific” for its protracted and bloody nature. The US Navy soon committed all its heavy and light cruisers to try to stop Japanese reinforcements during epic night battles. On 11–12 October the Battle of Cape Esperance was one of these, and USS Salt Lake City took part in it within TF 64, also comprising USS Boise, Helena (Brooklyn class) and USS San Francisco (Northampton class).

They were poised to intercept the “Tokyo Express”, a force difficult to assess, for its compsition and abilities. The Task Force was mostly ordered to raget transports. This force was off Espiritu Santo on 7 October, then departed for Guadalcanal on 9 October and waiting for the force to be spotted. Meawnhile, land-based search-plane reported an enemy force steaming down the “Slot” in the evening, and TF 64 moved close to Savo Island in order to fell on it.

Search planes were launched from the cruisers to locate the fleet, but the one onboard Salt Lake City′s caught fire, flares igniting in the cockpit. It crashed close to the ship, the pilot was rescued, later found on a nearby island. The fire however formed a well visible bright spot in the pitch black darkness and Japanese flag officers spotted it, assuming it was a signal flare from the landing force.

The Japanese flagship answered with blinker ligh, but receiving no reply, they insisted, starting to smell a fish. Meawnhile TF 64 formed a battle line while “crossing the T” of the Japanese formation. The Americans opened fire first, soon scoring hits for seven minutes before the Japanese realized and started to fire back. They believedat first to a freidnly fire by their own land forces and tried to contact them.

At last when they opened fire, it was too little, too late. Badly damaged, their operational level was just not enough to continue the fight. After 30 minutes, the firce one-sided engagement saw IJN Furutaka sunk, flagship Aoba badly damaged (She limped back to safety but was out of action for several months) and her sister ship Kinugasa, lightly damaged, the escort destroyer Fubuki sunk. The USN only had a destroyer, USS Duncan badly damaged, left to burn off Savo. Salt Lake City sustained three major hits, Boise was severely damaged. However all ships regrouped and steamed towards Espiritu Santo. Without escort, the transports turned back. It was a double victory, tactical and strategic, despite the damage on two cruisers and loss of a destroyer.

Battle of Komandorsky Islands (27 March 1943)

USS Salt Lake City left the Carolines and steamed towards Pearl Harbor. She was drydocked four months, for repairs and replenishing. Only back for duty in March 1943, she was ordered to the Aleutian Islands in the north Pacific. She was based in Adak Island, preventing an expected Japanese reinforcement of their garrisons on Attu and Kiska. The centerpiece of TF 8 (Rear admiral Charles McMorris), USS Salt Lake City was escorted by USS Richmond (Omaha class) and four destroyers. They patrolled on 26 March when Japanese transports escorted by Nachi and Maya, Tama and Abukuma and four destroyers were spotted. This was Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya’s force. The two forced were about to meet off the Komandorski Islands.

On Salt Lake City, the captain understood the crushing Japanese superiority but decided to engage them anyway. Both fleet met and starting to take lines, but soon gunnerywith twice as many guns as the Americans, the fight was soon one-sided. Before that however, the fleet was preceded by a screen of destroyers, the only ships spotted by TF8 at first. Onboard the flagship, Salt Lake City, confidence was renewed as it looked like easy picking.

The cruisers closed the range and engaged the escort, two transports fleein for safety and the Japanese cruisers, until that time onscured y bad weather, arrived and opened fire. Outgunned and outnumbered the Americans suddently changed course to try to engage the fleeing transports, and hoping the Japanese would split their force, but the IJN cruisers followed them and both sides could not avoid the fight.

The gunnery duel started at 20,000 yd (18,000 m) and soon Salt Lake City’s Charles McMorris decided to retire, as the odds were against them. The flagship cruiser received most of the battle damage, as the four cruisers concentrated on her first. She soon received two hits, but her fire was still very accurate. Her rudder jammed at some point to a 10° course and starboard seaplane caught fire (it was jettisoned). She had flooded forward compartments and soon other salvoes fell too close for comfort. Eventually she laid a thick smoke screen, also contributed by the four destroyers that deployed forward and started aggressive torpedo attacks.

Both American cruisers made an evasive turn, opening the range, but the smoke was soon drifting and Salt Lake City spotted again, and fired upon. She took more hits: She suffered a vuilet boiler fire and fuel oil feed lines was contaminated by salt water. Soon she lost power and was found dead in the water, while Japanese ships were closing fast. Meanwhile, her destroyers made wonders, helped by a change of the wind, covering her with smoke.

The destroyers charged the Japanese cruisers again, draw fire away from Salt Lake City and firing more torpedo volleys, even if they were out of range. USS Bailey received two 8 in shell just as she discharged five torpedoes. The others dodged massive near-misses. Meawnhile engineers purged the fuel lines, re-fired the boilers and the ship started to built up steam again and depart. However a miracle happened as Japanese withdrawn, unexpectedly. Indeed meanshile, the Japanese intercepted demands for air support and mistook the 5-in HE shells fired by the destroyers for air-dropped bombs. Also during their hot pursuit they expended most of their ammunition and were low on fuel, also overestimating the American real state, in part thanks to the resolute action of the four destroyers, not unlike what happened with the escoet of Taffy 3 a year later at Leyte.

In the end, despite heavier losses, the Americans succeeded in repelling the Japanese reinforcement. TF8 went back to Adak with 1 heavy cruiser severely damaged, 2 destroyers moderately damaged, 7 killed and 20 wounded while the Japanese had one heavy cruiser moderately damaged, one slightly damaged, 14 killed and 26 wounded. Salt Lake City was later able to capitalize on this and despite her state, covered the American liberation of Attu and Kiska, which won the Aleutian Campaign for the Americans. She departed Adak on 23 September to San Francisco and to Pearl Harbor after repairs. She arrived in October 1943, as the Carolines campaign was ending also favorably.

Early 1944 Operations

The Allied offensive now turned to Marshall Islands, as the Caroline were “bagged”. There was a two-column thrust to Micronesia and the Bismarck Archipelago, in the hope to divide the Japanese. For this, adequate intelligence was needed and the Gilbert Islands were targeted first to offer an airfield for upcoming operations. Salt Lake City was assigned to Task Group 50.3, Southern Carrier Group and prepared for Operation Galvanic.

She made intensive gunnery training until 8 November and sailed to join the cover of USS Essex, Bunker Hill, and Independence steaming to raid Wake as a diversion (5–6 October). Next they attacked Rabaul on 11 November. USS Salt Lake City was in Funafuti (Ellice Islands) on the 13, the resplenishment point off Espiritu Santo. On the 19th she shelled Betio, Tarawa Atoll and repelled torpedo plane attacks. Tarawa fell the 28th. Next, Salt Lake City was attached to the Neutralization Group, TG 50.15, for the Marshalls Campaign. On 29 January and until 17 February 1944, she shelled Wotje and Taroa, bypassed, cut off to concentrate on Majuro, Eniwetok and Kwajalein in typical leapfrog fashion devised by Halsey and Spruance. On 30 March and the following day, Salt Lake City shelled Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai (western Caroline Islands) and replenished at Majuro on 6 April-25 April after which she sailed for Pearl Harbor and from the, Mare Island Naval Shipyard and a possible refit. On 7 May-1 July she trained in the San Francisco Bay area before being ordered to Adak again. She was there on the 8th and shelled Paramushiro despite the severe weather. She was back to Pearl Harbor on 13 August.

Late 1944-1945 Operations

Teaming with her sister ship USS Pensacola, and the fast light carrier USS Monterey (CVL-26) she departed on 29 August bound for Wake Island. On 3 September both cruisers shelled the island, also attacked by air, and proceeded to Eniwetok, refuelling there until the 24th. They then patrolled of Saipan and on 6 October, went to Marcus Island for a diversion as effort concentrated on Formosa. They shelled the island three days later and went back to Saipan.

Of course October saw the second Battle of the Philippine Sea. USS Salt Lake City was back in support with the carrier strike group, based at Ulithi. Operations went on between 15 and 26 October and on 8 November 1944 – 25 January 1945, she was assigned to CruDiv 5, TF 54. She took part in the attacks on Volcano Islands, with raids coordinated with B-24 Liberator strikes. In February 1945, she operated both bombardments and AA cover for TF 54 at Iwo Jima and premliminary operations for Okinawa.

She provided “call-fire” (close support to the Marines on demand) at Iwo Jima until 13 March. Thee she operated around Okinawa until 28 Ma, before departing for Leyte and upkeep. She covered minesweeping operations, patrolled the East China Sea with TF 95 in July 1945. From 8 August, she sailed back to the Aleutians via Saipan, counter-manded on 31 August, and ordered instead to sail for Honshū, in anaticipation of the occupation of Ominato Naval Base. The war had ended by then and the cruiser had an impressive tally and 11 battle stars.

Post-war service

Due to her age, like her sister, USS Salt Lake City was to be deactivated soon after making runs with POWs and veterans. She reported to the 3rd Fleet, west coast in October 1945 for deactivation but diverted to take part in Operation Magic Carpet until 14 November. She was selected for Operation Crossroads in Bikini Atoll, partially disarmed and stripped, her crew reduced, and she sailed to Pearl Harbor in March 1946 then Bikini, prepared for both tests, Able and Baker, surviving both bomb blasts, and studied. She was towed away and decommissioned on 29 August, sunk as a target on 25 May 1948, 130 miles off the coast of Southern California, stricken on 18 June 1948.

The end of Salt lake City as a target 25 may 1943

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Generally a good article but it doesn’t answer the question of why the triple turrets were placed above the twins. Did someone have a theory that this was better or was it just a mental lapse (stupidity)?

Hello Doug

All i know as states Wikipedia (no more info from conways on this) “Placing heavier turrets above lighter ones allows for finer lines for a given length”. I’ll dig deeper into the subject when the post (still going some changes) will be published on facebook.

Best,

No, it was necessity because the triple turret were too large for the bow and aft section.

Indeed. this article needs serious rewrite anyway. Will be done this year.

Doug & Dreadnaughtz

The super-imposition of the triple turrets over the twins in the Pensacola class cruisers was down to the fact that both – in order to ensure they complied with Washington Treaty-driven individual ship tonnage quota for the ‘heavy cruiser class’ (10,000 tons maximum, standard load) – had very narrow (‘fine’) lines toward both stem and stern. A larger, triple gun turret would require a larger barbette and turret substructure than could be fitted within such narrowly confined hull spaces fore and aft, so the decision was taken to put the triple mounts in a ‘super-firing’ (ie : above) position over the twins. Highly unusual (possibly not replicated in any other class of ship – ever !) but expedient in the circumstances, especially when there were so many ‘unknown quantities’ at this time of warship building. The subsequently-discovered drawback was that the triple-superfires-twin-gun-mount arrangement – along with the tall tripod masts fore-&-aft (and other topside needs) – created excessive ‘meta-centric height’, meaning these ships were somewhat prone to rolling in even normal Pacific Ocean swells, thus running a risk of capsizing in heavy seas. Fortunately this didn’t happen and later in the Pacific War during WWII, the 2 Pensacola class cruisers were given an overhaul that simultaneously increased their fighting efficiency, by augmenting the radar suite and increasing the anti-aircraft defence battery, and decreased their meta-centric height, principally by drastically cutting-down the height of their fore-&-aft masts, thus reducing ‘top-weight’.

You probably already know this … Whatever – I just do it cos I love it …

Excellent point Mark !

The true reason behind this unusual choice could have been averted with the use of computer-assisted design. But… Others times, and treaties self-imposed by good will from top (no doubt the admiralties in general were not happy with these). Sometimes challenges are good for innovation though. I think too the design was never repeated anywhere else, but it needs to be verified for sure.

-David B, alias Dreadnaughtz