Nuclear-powered attack submarines (1958-67), service 1961-1993: USS Thresher, Permit, Plunger, Barb, Pollack, Haddo, Jack, Tinosa, Dace, Guardfish, Flasher, Greenling, Gato, Haddock (SSN-593 to 621)

Nuclear-powered attack submarines (1958-67), service 1961-1993: USS Thresher, Permit, Plunger, Barb, Pollack, Haddo, Jack, Tinosa, Dace, Guardfish, Flasher, Greenling, Gato, Haddock (SSN-593 to 621)Cold War US Subs

GUPPY | Barracuda class | Tang class | USS Darter | T1 class | X1 class | USS Albacore | Barbel classUSS Nautilus | USS Seawolf | Migraine class | Sailfish class | Triton class | Skate class | USS Tullibee | Skipjack class | Permit class | Sturgeon class | Los Angeles class | Seawolf class | Virginia class

Fleet Snorkel SSGs | Grayback class | USS Halibut | Georges Washington class | Ethan Allen class | Lafayette class | James Madison class | Benjamin Franklin class | Ohio class | Colombia class

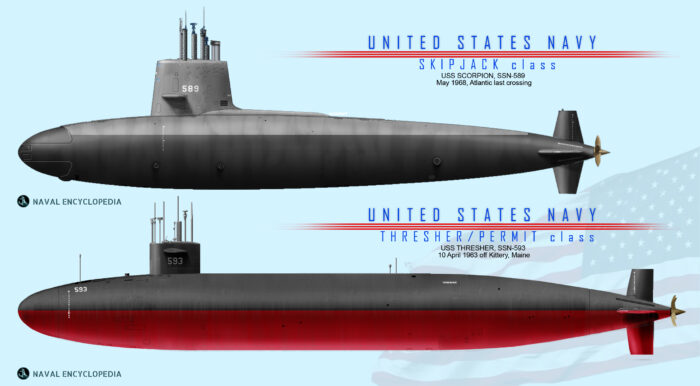

Also known in most publications the Thresher/Permit class, the Permit class Nuclear Attack Submarine marked the true transition to a semi-prototype stage of nuclear submarines (they were preceded by the Skipjack class, first to marry the teardtop hull shape with nuclear power and superior sonar), to mass produced standard SSNs. They truly were the first of these, and maturity was reached in 1968 with the Los Angeles, which owned a lot to the former boats. These nuclear-powered fast attack submarines (SSN) constituted indeed a significant improvement over the Skipjack class having a greatly improved sonar covering the whole bow, side tubes, better diving depth and being far more stealthy. These 13 ships (less Thresher) served until the early 1990s, so between 24 and 29 years of continuous service, being followed by the Sturgeon and Los Angeles classes. #usnavy #coldwar #ussthresher #usspermit #SSN #permitclass #nuclearattacksubmarines

Development: The SBC 188 programme

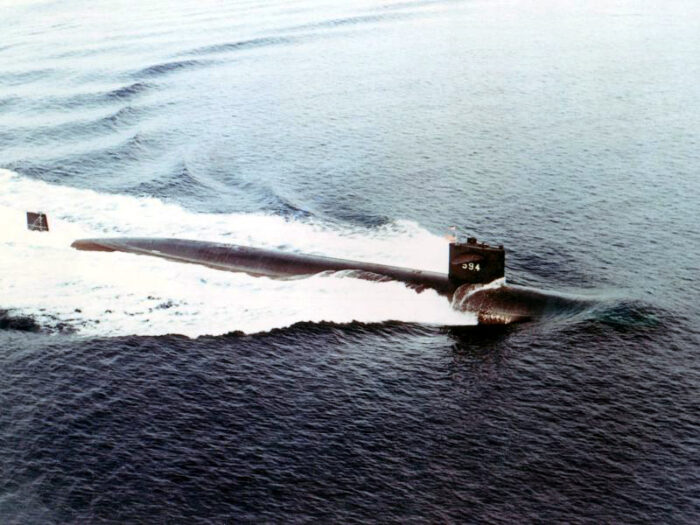

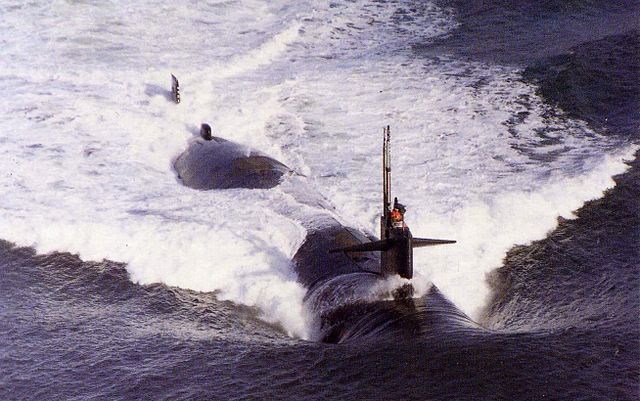

The very clean shapes of the Permit class (here USS Thresher in her first deployment) reduced outer hull dsturbances and noises, enabling to keep a top speed of 33 knots despite having the same nuclear reactor and output as the lighter Skipjacks. Note the narrow and 30% smaller sail than on the Skipjacks. The diving planes were no longer usable by the crew.

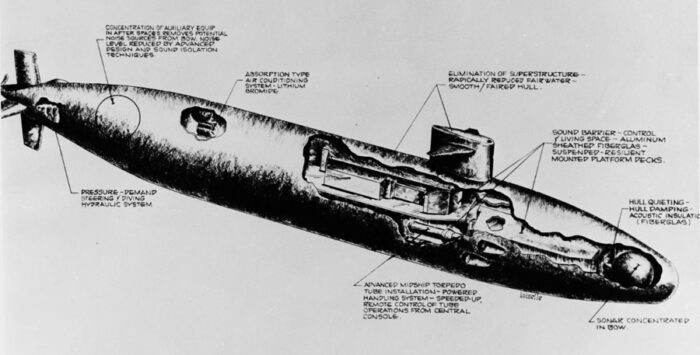

Artwork by Hultberg, circa 1960, depicting the submarine’s anticipated appearance when completed. It shows two torpedoes being fired from Thresher’s midships torpedo tubes. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command

The Thresher class resulted from the 1956 study commissioned by Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Arleigh Burke. “Project Nobska” was the result of the Committee on Undersea Warfare of the United States National Academy of Sciences with numerous other agencies. They digested the lessons of submarine and ASW warfare learned from prototypes such as the Nautilus, Albacore and others. The design of the successors of the Skipjacks was classified under project SCB 188. But they also came bacj as far back as 1949 when the concept of hunter-killer submarine was theorized, and the concept was only made urgent when the Soviets started to field SSBs (Zulu V, Golf I, Golf II) with early nuclear ballistic missiles at the end of the 1950s.

Thresher was created to dive deeper and silent running to detect everything passively thanks to a massive sonar, while staying coutsically “invisible”. This was the embodiement of the hunter-killer concept. On secret came from land tests in secret facilities, where engineers measured the sound coming from various mounting configurations of turbines and transmissions. It was established that inserting rubber washers between metal parts and fasteners stopped radiant noise which was assoviated normally with metal on metal contact. The shape was the latest evolution also of the stilml recent tear-shaped hull and refined in both aerodynamic and hydrodynamic test pools, creating a return in efficient submerged running (at the very birth of US submarines in 1899). Theother innovation was to cast the pressure hull in section of improved hull plates made from HY-80 steel. It was tested able to resist a pressure up to 80,000 psi. Diving deeper than Soviet subs enabled them to attack from below, an unlikely detection area for any sub at the time. This also gave more room top manoeuver and escape possible Soviet ASW forces or just operate at below 1,300 feet.

Powerplatnt-wise, the first point was to keep the now proven S5W reactor from the Skipjacks, but all the rest was to be different. The first and most important point was to mount a large bow sonar sphere, taking all available space in the bow. The only solution was to have the tubes relocated amidships, angled, in order to fire essentially homing torpedoes, a solution also adopted by the experimental USS Tullibee. This made the sonar sphere in an optimal position for a better detection arc at any azimuth and longer range. Tullibee we saw in June 2024 was an alternate design optimized for anti-submarine warfare which was also smaller and slower but with a very quiet turbo-electric propulsion system and same HY-80 steel hull as the Skipjacks, a pressure hull capable of test depth in excess of 1,300 ft (400 m).

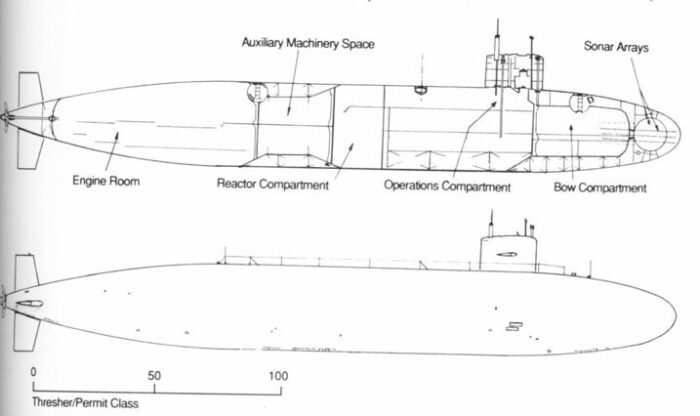

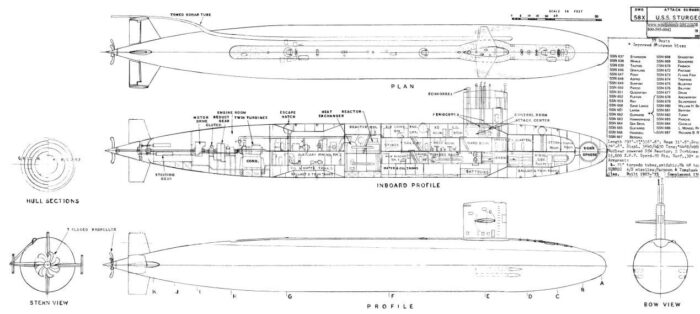

Cut-away sketch of this class submarine, detailing some of its special features. Drawn circa 1963.

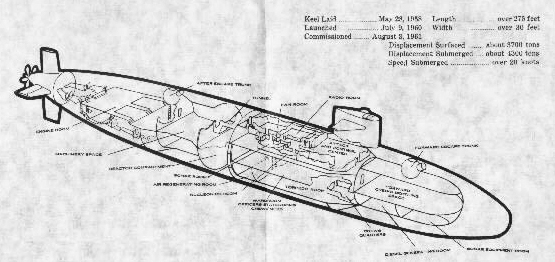

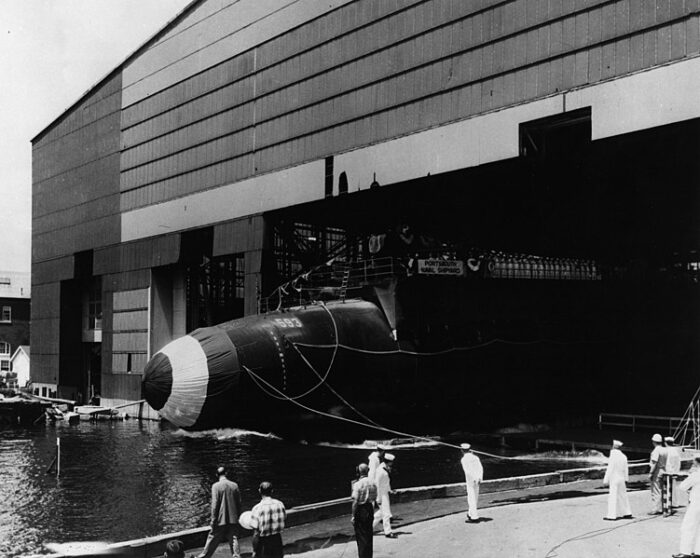

In the end, the combination of all of these innovation was crystallized on USS Thresher (SSN-593), the lead boat, laid down at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on 28 May 1958 and launched on 9 July 1960 for a completion on 3 August 1961. She was lost in 1963 so trials had been successful and she already had fixes and changes, now undergoing more active deployments whe lost. There was an almost year gap between her and the rest of the class, notably USS Permit, laid down at Mare Island on the west coast, on 16 July 1959, launched in July 1961, exactly a yer after her sister, and competed by May 1962, too early to undergo the SUBSAFE changes, implements later on the class and the next Sturgeon class from the class.

Extract of the commissioning brochure of USS Thresher in 1960.

Design of the class

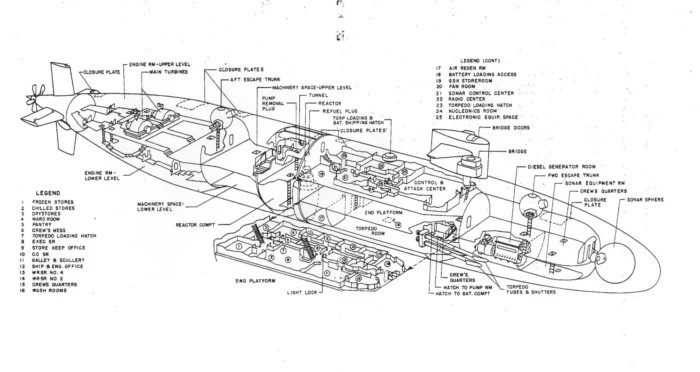

Cutaway of USS Plunder SSN-595, Courtesy of The Lean Submariner from official archives.

There were many differences with Tullibee and the Skipjacks also in that all engineering spaces were redesigned. The turbines were now supported on “rafts”suspended from the hull, on isolation mounts in order to cut off all vibration from the hull. Machinery was almost “in a vacuum” and that noise reduction was also a benefit to the crew. These ubs became the quietest in the USN so far. So much so that WW2 veteran submariners coming from the fleet snorkels (many were still around and not retired yet) had a hard time to believe the submarine was in movement at full speed. Drag was also reduced with a considerable rework of the hull, which made more cyclindrical (whuch bvrought extra benefits, see later) and had external fittings kept to a minimum. As usual the water scoopsopf the outer hull were now all blended and shut close when not in sude. The sail was also greatly reduced in size compared to the Skipjack class. All this contributed to a massive noise reduction, making these SSNs the world’s quietest submarines so far.

The small sail of Thresher was also a way to counterbalance the increased drag of the longer, cylindrical hull instead of a more complex teardrop shape. That gave the lead boat USS Thresher a top speed of 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) just like the Skipjacks on the same output but a longer and heavier hull. The pressureized water reactor compartment was made even more compact and all this elabled extra space for living crews accomodations. However this small sail had shortcomings, allowing only one periscope less electronics masts. It was also less interresting for the surfaced watch crew (also reduced) in rough seas. There was also an increased possibility of “broaching” (inadvertent surfacing) at periscope depth in rough seas. The propeller was also reworked and changed between Thresher and the rest of the Permit class. Mid-life upgrades were applied in the late 1970s and 1980s such as the AN/BQQ-5 sonar suite with a retractable towed array and the Mk 117 torpedo fire control among others, allowing these 1950s tech SSNs to remain operational until the end of the cold war.

Hull and general design

Same scale comparison between the Skipjacks and USS Thresher, self-explanatory (author’s illus).

The Permit class displaced 3,750 long tons (3,810 t) surfaced and 4,300 long tons (4,369 t) submerged, to compare with 3075/3513 tons, an increase of 800 tonnes. They were also longer at 278 ft 5 in (84.86 m) overall versus 251 ft 8 in (76.71 m) so 8 meters or 24 feet for a slightly smaller outer hull at 31 ft 7 in (9.63 m) versus 31 ft 7.75 in (9.6457 m) for the Skipjacks. The Draft reflected the greater displacement, with 25 ft 2 in (7.67 m). The greatest differences in shapes

Powerplant

Internals, original plans (pinterest).

The Permit class opted for a repeat of the Skipjack powerplant, meaning a single shaft propeller (more on this later), driven by two turbines via a combined electric transmission, powered in turn by the S5W reactor, which itself boiled water and produced superheated steam. The ASFR (Advanced Submarine Fleet Reactor) had its designation stands for S = Submarine platform; 5 = Fifth generation core designed by the contractor and W = Westinghouse was the contracted designer.

Standard reactor for the Skipjacks, Permit and Styrgeon, so before the Los Angeles-class which opted for the more advanced S6G. The S5W also powered the HMS Dreadnought.

This pressurized water reactor was both simplied and overdesigned to enhance redundancy, safety, automatisation including, tolerance of battle damage. It had impeccable records of reliability, longevity, and safety and they were later upgraded to be refueled with a S3G core-3.

The S5W made its way into no less than 98 U.S. nuclear submarines in eight classes, making it the most-used US Navy reactor design ever.

It used steam exchangers and boilers to pass on steam to two General Electric geared turbines rated for 15,000 shp (11,000 kW)) on a single shaft.

Like the Skipjacsk, the Permit class opted for a five-bladed propeller which shape came out from USS Albacore, and became standard for the next classes albeit its shape was revised.

The powerplant gave 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) surfaced, 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) submerged, 33 knots on USS Thresher. 28 knots was not only the safety, normal operation top speed with the option in wartime of runs at higher speeds if needed, but with a great level of noise. Top speed after the swap from the Skipjack’s and Thesher’s 5-bladed screw to a larger, 7-bladed screw reduced that top speed but avoide cavitation, perserving stealth.

USS Thresher indeed was fitted originally with the same five-bladed symmetric (constant blade shape) screw very similar to the ones originally fitted to the Skipjacks, however during trials it was found that the propeller produced noise below cavitation depth. Many tests showed this was due to blade-rate, as they started vibrating when hitting the wake of the sail and control surfaces. That noise travelled many miles and could even provide vital data to the enemy to determine a firing solution as its frequency of blade-rate was directly linked to the target’s speed.

Solutions proposed were to design a smaller screw to not hit the wakes of the sail and control surfaces or at the contrary making it large enough and reshape to gently interact with these areas of disturbed water. The latter was chosen as a smaller screw would meant heighr rpm to reach the desired speeds anyway.

The new, larger and reshape screw propeller to a seven-bladed one soon became the one adopted on the Pedrmit class and subsequent SSNs of the US Navy. These seven-bladed skewback (meaning asymetrical, banana or boomerang blade shaped) screws reduced this problem of blade-rate, but had consequences of reducing top speed to 29–28 knots (54–52 km/h; 33–32 mph) as they were less efficient. USS Jack was the only one to test designed with counter-rotating screws in order to reclaim speed, each of screw being smaller, and this became a semi-viable alternative solution to the blade-rate problem, albeit top speed was strill unsufficient. This field of research would bounce again with the Sturgeons and found perfection with the Los Angeles class.

Armament

Due to the new configuration with the tubes relocated behind the sonar close to the sail, with angles tubes, two tubes per sides (in height a full compartment) seemed more practical. The loss of two tirpedo tubes at this point was accepted given the new types of torpedoes just accepted into service, far more capable. And so four 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes amidships, two per side, became the new standard. For this, there was a normal provision of 12-18 Mark 37 torpedoes and later Mark 48 torpedoes.

With upgrades, new capabilities were offered: At first from four to six UUM-44 SUBROC anti-submarine missiles, and then four UGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles.

In 1990 when they were decommissioned, the Permit class had the usual panoply of the Los Angeles class.

Between increased sensitivity in detection while being kept stealthy themselves or diving deeper, the Mark 37 Torpedo (anti-shipping/anti-submarine) was just the start. They carried also the the nuclear tipped Mark 45 ASTOR (anti-submarine torpedo). The new SUBROC (submarine launched missile) shared nothing with the surfaced ASROC, was basically a missile-launched nuclear depht charge, but gave a range that was way beyong the capabilities of any SSN at the time, enabled by the exceptionally long range sonar, it was a match in heaven. For the first time, a submarine could out-range all its prey. The combo Mark 45 ASTOR/UM-44 SUBROC forbade entry in any international port banning nuclear weapons. The crew was not always aware of their presence on board either.

The 21-in sea-mines designed to be launched from their torpedo tubes also became a feature, albeit they had never being used in anger.

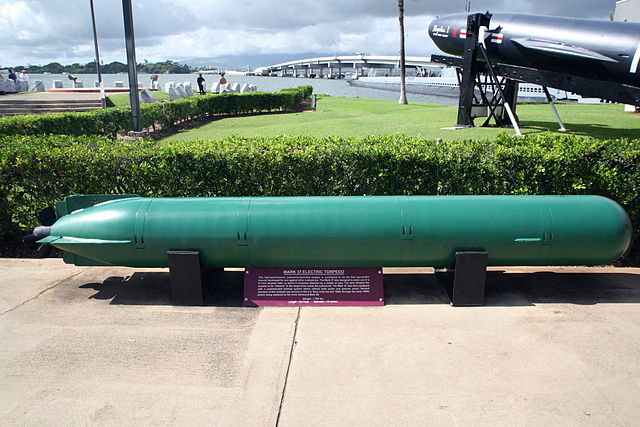

Mark 37 torpedoes

A post-WW II electric acoustic torpedo forst deployed in 1957. The Skipjacks were probably given the 1960 Mark 37 Mod 1, specs below. The 19″ (48.3 cm) Mark 37 and Mark NT37 Designed about 1956 (last introduced, Mod 3: 1967) became the standard US Submarine launched ASW torpedo of the 1960s and until the 1990s.

⚙ specifications Mark 37 TORPEDO |

|

| Weight | 1,660 pounds (750 kg) (mod.1) |

| Dimensions | 161 inches (410 cm) (mod.1) x 19 inches (48 cm) |

| Propulsion | Mark 46 silver-zinc battery, two-speed electric motor |

| Range/speed setting | 23,000 yards (21 km) at 17 knots, 10,000 yards (9.1 km) at 26 knots |

| Warhead | 330 pounds (150 kg) HBX-3 high explosive with contact exploder |

| Max depth | 1,000 feet (300 m) |

| Guidance | Active/passive sonar homing, passive 700 yards (640 m) from target, active and wire-guidance |

Mark 48 torpedoes

Adopted by the Skipjacks and Permit class in addition or replacement for the Mark 37 in the mid-1970s, the Mark 48 and its improved Advanced Capability (ADCAP) variant were heavyweight submarine-launched torpedoes. They were designed to sink deep-diving nuclear-powered submarines and high-performance surface ships. They entered service in 1972 for the first mod, 1988 for the ADCAP (photo).

Adopted by the Skipjacks and Permit class in addition or replacement for the Mark 37 in the mid-1970s, the Mark 48 and its improved Advanced Capability (ADCAP) variant were heavyweight submarine-launched torpedoes. They were designed to sink deep-diving nuclear-powered submarines and high-performance surface ships. They entered service in 1972 for the first mod, 1988 for the ADCAP (photo).

⚙ specifications Mark 48 TORPEDO |

|

| Weight | 3,434 lb (1,558 kg) |

| Dimensions | 19 ft (5.8 m) x 21 in (530 mm) |

| Propulsion | swash-plate piston engine; pump jet Otto fuel II |

| Range/speed setting | 38 km/55 kn or 50 km/40 kn |

| Max depth | 500 fathoms, 800 m (2,600 ft) est. |

| Warhead | 647 lb (293 kg) HE plus unused fuel, proximity fuze |

| Guidance | Common Broadband Advanced Sonar System |

Mark 45 ASTOR nuclear torpedoes

These very particular torpedoes were designed in part in respsonse to Soviet rumored small warheads tests and probably adoption on torpredoes and for general tactical use as per the new wide scale 1960s US deterrence policy. The Mark 45 anti-submarine torpedo (ASTOR) was submarine-launched and wire-guided usable against high-speed and deep-diving Soviet submarines. It was first recommended for implementation by 1956 Project Nobska a summer study on submarine warfare. Its was 19-inch (480 mm) in diameter while carrying a W34 nuclear warhead and under direct control maintained between the torpedo and submarine until detonation. It had no homing capability. The design was completed in 1960, 600 were built between 1963 and 1976 until replaced by the Mark 48 torpedo.

⚙ spec. Mark 45 ASTOR |

|

| Weight | 2,400 pounds (1,100 kg) |

| Dimensions | 227 inches (580 cm) x 19 inches (48 cm) |

| Propulsion | Electric |

| Range/speed setting | 40 knots, 5–8 miles (8–13 km) |

| Warhead | W34 nuclear warhead, yeld 11 kilotons |

| Guidance | Gyroscope and wire |

UM-44 SUBROC missiles

The UUM-44 SUBROC (SUBmarine ROCket) was deployed as a long range tube-launched anti-submarine weapon. It carried a 250 kiloton thermonuclear warhead if configured as such, at a more safer distance than the Mark 45 ASTOR torpedo, and essentially replaced it. This weapon was recommended for implementation by 1956 Project Nobska and development started in 1958, completed in 1963. SUBROC entered service with USS Permit in 1964, so basically soon after the class entered service. However the admiral in charge of weapons procurement stated this wepaon caused more problems than Polaris. Main requirement was to be launched through a 21-inch submarine torpedo tube, and after launch, the solid fuel rocket motor fired, the SUBROC container rapidly rose to the surface and the booster carrying the torpedo flew to destination on a predetermined ballistic trajectory. The reentry vehicle (warhead) at the set time separated from the solid fuel motor and its low kiloton W55 nuclear depth bomb dropped into the water, sank rapidly to detonate at a set depth prior to launch. Accuracy was not a problem.

The W55 (the missile) was 13 inches (33 cm) in diameter, 39.4 inches (100 cm) long, for 465 lb (211 kg) in weight and tactically this was an urgent-attack long-range weapon to strike submarine targets out of range without betraying the position of the launching submarine, and recalled ASROC or Ikara. The additional bonus was a ballistic approach to the target making it undetectable by the target and prevented evasive action. It was however less flexible in its use than Ikara or ASROC and could not be used in a conventional engagement.

SUBROC production ended in 1968 and it was obviously never used in combat, with 285 W55 warheads decommissioned in 1990. SUBROC could not be exported either, even never shared with NATO allies. The planned UUM-125 Sea Lance was authorized in 1980, contract awarded to Boeing in 1982 but cancelled in 1990.

This weapon remains an interesting cold war weapon without true equivalent.

⚙ spec. UUM-44 SUBROC |

|

| Weight | 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) |

| Dimensions | 22 ft (6.7 m) x 21 in (53 cm) |

| Propulsion | Solid rocket booster |

| Range/speed | 55 km (34 mi), subsonic |

| Warhead | W55 1-5 kt (4.2 to 20.9 TJ)/25 kt (100 TJ), Depth Fuze |

| Max depth | Unknown |

| Guidance | Inertial guidance ballistic trajectory |

UGM-84 Sub-Harpoon missiles

The Harpoon was the go-to antiship missile of the USN from 1977. With its amazing range it was tempting to offer the Permit, Sturgeon and Los Angeles classes this upgrade while in service when entering service in 1981. Indeed the UGM-84, name given to the submarine launched variant was fitted with a solid-fuel rocket booster and encapsulated in an upropelled canister using the tube initial propulsion to enable submerged launch at reasonable depth. The flexible wings were folded around the missile body and opened after the missile booster ignited, when it was propelled out of the canister, setup to reach the surface. The canister was partly burned out as the missile ingnited inside after its head popup.

The Harpoon was the go-to antiship missile of the USN from 1977. With its amazing range it was tempting to offer the Permit, Sturgeon and Los Angeles classes this upgrade while in service when entering service in 1981. Indeed the UGM-84, name given to the submarine launched variant was fitted with a solid-fuel rocket booster and encapsulated in an upropelled canister using the tube initial propulsion to enable submerged launch at reasonable depth. The flexible wings were folded around the missile body and opened after the missile booster ignited, when it was propelled out of the canister, setup to reach the surface. The canister was partly burned out as the missile ingnited inside after its head popup.

When freed, the UGM-84 raced to its target as a sea-skimming missile on predeterminated target data fed before launch, and then homing took over in full autonomy when reaching its final leg to the target. Data came from radar or satellite, and sonar if needed. This gave US Navy SSNs an unprecedent range of 67 nmi (124 km) for the Block II for example, at Mach 0.71 to 0.9. Normal provision was four of them on board a Permit class from the 1980s. It was also designated GWS-60 (UGM-84B in UK service) and exported to South Korea and Egypt. The Permit class had the UGM-84A and potentially upgraded to the UGM-84C (Block Ic), UGM-84D from 1985, less likely UGM-84G and UGM-84L so close to retirement.

⚙ spec. UGM-84A Sub-Harpoon |

|

| Weight | As regular missile + canister |

| Dimensions | Canister 21-in, c20ft long |

| Propulsion | solid propellant booster motor |

| Range | 130 to 220 km depending on version |

| Speed | Mach 0.9 |

| Warhead | 220 kg warhead |

| Guidance | Initial intertial, active radar homing terminal, later GPS |

Sensors

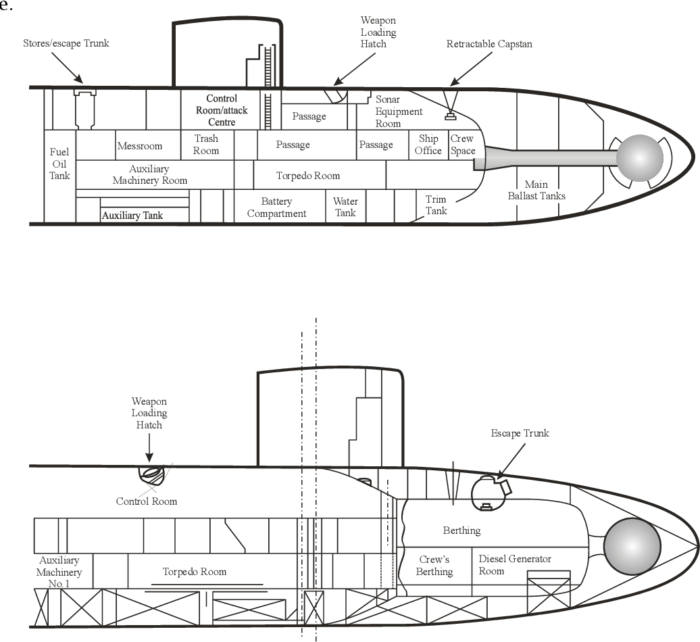

Fwd compartment differences, Los Angeles versus Permit class, from pinterest

The Thresher-class came up with the new passive SONAR AN/BQQ-2, capable of hearing sounds at much greater and on a near 360° arc. Fitted into the bow it filled it entirely, forcing the torpedo room back amidships. But the benefit was just considerable.

BQQ-2 (BQR-7 + BQS-6) bow sonar:

This model was adopted fist for USS Tullibee and also mounted on the Tresher/Permit class SSNs. It combined an Active BQR-7 and Passive PQS-6 arrays, for Active/Passive Search & Track with an unprecedented range of 74.1 km, well beyond the range of torpedoes. Thus, the adoption of SUBROC made a lot of sense and gave USN attack submarine an edge over the Soviet Navy.

The successor AN/BQQ-5 sonar suite was a real improvement as it came with a retractable towed array, the “snake”, for an even more efficient detection sensibility far from the host submarine.

Mark 113 Fire Contol System:

This was a very advance fire control system for the time, computirized, combining several displays but manageable by a single fire control operator. It comprised the Mk 78 Target Motion Analyzer digital computer which memory module has 1024 round magnets with wires wrapped around them. The Mk 78 TMA determined the Target’s course and speed adn sent the data to the Mk 75 AD.

The Mk 75 Attack Director is an analogue computer using synchros, servos, resolvers, and rheostats plus handcranks to input information displayed with counters and dials. The Mk 75 AD solves data targeting Problems and sends the Gyro Angle to the Torpedo.

The Mk 66 Torpedo Control Console was coupled with the Mk 47 Tone Signal Generator used for the Mk 48 Torpedoes, capable of sending new commands and course corrections after fire.

The Mk 50 Attack Control Console prepared the torpedoes launch, coupled with the Digital Interface Box (DIB).

The Mark 113 was replaced by the Mark 117 fire control system envisioned by some to do any thing and almost replace the operator, but in reality it just increased the training requirement. It was capable to manage longer range and missiles, as introduced in the 1980s.

The radar suite is unknown, likely the same as the Skipjack albeit simplified as the Permit’s fins were smaller. So one radar/aerial combined model.

Same with the EW suite it was probably limited.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 3,750 long tons (3,810 t) surfaced, 4,300 long tons (4,369 t) submerged |

| Dimensions | 278 ft 5 in x 31 ft 7 in x 25 ft 2 in (84.86 x 9.63 x 7.67 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft S5W PWR, 2 steam turbines, 15,000 shp (11 MW) |

| Speed | 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) surfaced, 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) submerged |

| Range | Unlimited, except by food supplies |

| Armament | 4 × 21 inch (533 mm) TTs, Mark 37, Mark 48, UUM-44 SUBROC, UGM-84 Harpoon |

| Test Depth | 1,300 ft (400 m) |

| Sensors | BQQ-2 sonar (later BQQ-5), Mark 113 FCS (later Mark 117), ESM |

| Crew | 112 |

Improvements and Upgrades

In the 1970s all Permit class had their BQQ-2 sonar suite replaced by the BQQ-3 which combined the BQS-11 and BQR-7 as a sonar suite, until the end of their career.

In the early 1980s, Permit, Plunger, Barb, Pollack, Dace, Flasher, Haddock and a few yars later the remaining subs were given four SUBROC ASW rockets (UUM-44) and four 4 Harpoon SSM (UGM-84).

In the late 1980s some had their BQQ-3 sonar suite replaced by the BQQ-5 sonar suite whereas the Mark 113 Fire control system was replaced by the Mark 117. Aslo the electronic warfare system was upgraded. Also from 1984 the UGM-83A Harpoon replaced the Mark 48 nuclear-tipped torpedoes.

Flasher sub-class (SBC-188M)

USS Flasher, Greenling, and Gato came out as a redesigned variant under project SCB 188M. They were fitted with a larger sail to house additional masts, adn the convenently cylindrical hull amidship allowed to add with ease a 13 feet 9 inches (4.23 meters) long section to include additional SUBSAFE features and create additional reserve buoyancy as well as fitting more intelligence gathering equipment for their missiones as well as improving accommodations. Haddock was the only one completed with the standard 279-foot (85 m) hull but the new sail.

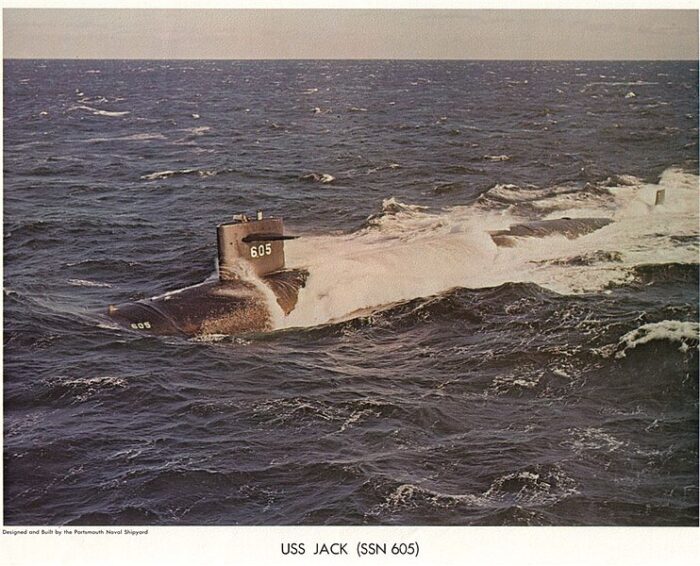

USS Jack sub-class

USS Jack was also lenghtened, but at the engine room, by a more modest 10 feet (3.0 m), to accommodate an experimental direct-drive propulsion system. She was also the only one to use concentric counter-rotating propellers. They had produced extra speed on the diesel-powered Albacore, but in Jack not so much, due to the difficulty in sealing the shaft. She was however used to test polymer ejection to reduce flow noises parasiting sonar acquisition as well. It should be noted that the Sturgeons also had their own share of “stretching”, the record holder being USS Glenard P. Liscomb featuring a turbo electrc transmission for 365 ft (111 m) overall.

USS Thresher tragedy and SUBSAFE

On the mediasphere, the case of USS Tresher made it one of the most infamous tragedy among submariners and the general public as well. To cut it short, she was the lead ship of a new SSN class, but was lost with 129 crewmembers and shipyard personnel on 10 April 1963, 200 nautical miles (370 km) east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Most importantly, the exact cause of her sinking remains unknown… to this day.

USS Thresher SSN-593

USS Thresher SSN-593

USS Thresher (SSN-593) was laid down at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on 28 May 1958, launched on 9 July 1960 and completed on 3 August 1961. She was lost just after 1 year and 7 months of service, including trials and shakedown with 129 crewmembers and shipyard personnel on 10 April 1963, 200 nautical miles (370 km) east of Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

When she entered service under Commander Dean L. Axene she conducted lengthy sea trials in the western Atlantic and Caribbean until 1962 to iron out any issue. She was precisely built a year before the others to be a testbed. These allowed a thorough evaluation of all her new features and weapons and she took part in the Nuclear Submarine Exercise (NUSUBEX) 3–61 on 18–24 September 1961.

On 18 October 1961, she operated with USS Cavalla over three weeks to San Juan, Puerto Rico and her reactor was shut down. Her backup diesel generator took over, but it broke down and battery power needed to keep vital systems operating and restart the reactor but lighting and air conditioning all went down. Temperature and humidity rose rapidly to 60 °C (140 °F) over 10 hours while the crew attempted to repair the diesel generator (all four would earn Navy commendation medals) while the rest of the crew stayed outside the submarine. As this the Generator was impossible to fix before the batteries went dead, they tried to restart the reactor but the charge left was insufficient. The captain was ashore, and arrived after the battery ran down. The crew borrowed cables from another ship in harbor to connected them to USS Cavalla, starting her diesels and reloaded batteries on Thresher enough to restart her reactor and sail back for repairs.

She conducted trials, fired test torpedoes and headed to Portsmouth on 29 November 1961 until March 1962 for repairs and fixes notably to her sonar and SUBROC systems just starting evaluation. In March, she took part in NUSUBEX 2–62 and trained with Task Group ALPHA, the latter trying to locate her.

Off Charleston she continued development of the SUBROC missile and sailed to New England waters, then back to Florida to completed SUBROC tests. When moored at Port Canaveral where the missile tests were carried out, she was accidentally struck by a tug, damaged one of her ballast tanks. She was repaired at Groton (Electric Boat) and sailed back for more tests and trials off Key West until sailing back to Portsmouth Shipyard on 16 July 1962 for her final six-month post-shakedown availability and a long list of corrections, but this reached nine months until she was recertified and undocked on 8 April 1963.

On 9 April 1963 under Lieutenant Commander John Wesley Harvey, she left Kittery in Maine at 8:00 a.m. to meet with the submarine rescue ship Skylark at 11:00 a.m. for her post-overhaul dive trials setup 190 nmi (350 km) east of Cape Cod. She conducted an initial trim-dive test while surfaced, and a second dive at c650-foot (200-meter) test depth, the 41th. She remained submerged overnight until re-establishing underwater communications with Skylark, using its own underwater telephone, at 6:30 a.m. on 10 April, signalling she was about to commence deep-dive trials. Standard practice had Thresher slowly dinving deeper, in a whirlwind pattern under Skylark to remain within communications distance and pausing every 100 ft (30 m) for checks. As she approached test depth, USS Skylark received garbled communications: “… minor difficulties, have positive up-angle, attempting to blow” and later an even more garbled message which only dicernable part was “900”. The all communication ceased. After waiting for a while under regular procedires, Skylark realized USS Thresher had missed her expected call and sensed a problem. Soon alert was sent to shore command and a full search and recue operation commenced with at first 15 ships arriving in mid-afternoon. At 6:30 p.m., the commander, Submarine Force Atlantic (ComSubLant) warned the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard and started to notify the crew’s family members.

CNO Admiral George W. Anderson Jr. attended the press at the Pentagon to annoubce USS Thresher was lost with all hands. President John F. Kennedy ordered all flags at half staff from 12 to 15 April to pay hommage to the 129 lost submariners and shipyard personnel onboard for last minute fixes and reports. The drama was not over as USS Scorpion would be lost on 22 May 1968.

The Search and recovery operations on 15 April 1963 soon became colossal. The Navy wanted answer, given the importance of the program and with some many SSNs built in various yards on the same design.

The Navy quickly extensive search with surface ships gained support from the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), a civilian organiation which possessed at the time deep-search capability the Navy lacked. The research vessel Rockville has a trainable search sonar and departed on 12 April 1963 for the search area, and also carried a deep-camera system. Three ships led a close sonar search of the area over 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) square, some gained likely contacts and uktimately the NRL deep-towed camera system from James M. Gillis founded debris, later confirmed to be from Thresher. The experimental abyss diving bathyscaphe Trieste was at San Diego at the time and on 11 April she was requisitioned by the Navy and notified to sailed to Boston, deployed for two series of dives in debris field, taking scores of photo and making a cartography of the site from 24 to 30 June, and from late August until early September. After the campaign ended for the winter, search restarted on 11 April with the submarines USS Seawolf and USS Sea Owl operating near her location to find the hull itself. But at this stage it was clear she had imploded due to overpressure beyond her safety test depth.

What soon transpired was the inadequacy of existing small Auxiliary General Oceanographic Research vessels to handle deep-towed search vehicles and by late 1963, the acquisition of Mizar led to the creation of sheltered center well which started operation in 1964 with USS Hoist and Trieste II completed in early 1964, operating from the USNS Private Francis X. McGraw from Boston. Mizar used its Underwater Tracking Equipment (UTE) to track its towed vehicle and Trieste, fitted with highly sensitive proton magnetometers from Varian Associates, Palo Alto. They were suspended on an electrical line towing underwater video cameras.

This phase srarted on 25 June 1964 and too pictures of the shattered remains of Thresher’s hull under 8,400 feet (2,600 m), with the hull separated into five major sections and debris spread over 1,440,000 square feet (134,000 m2). By July 22 was completed the photographic/mapping phase and by early August, the task force returned and on the 3rd dive Trieste II arrived over the wreck and started direct observation under Lt. John B. Mooney Jr., John H. Howland, Captain Frank Andrews, recovering parts of the wreckage in September.

On 9 July 2021 all was declassified about the fact USS Seawolf in the vicinity on 10 April detected acoustic signals at 23.5 kHz and 3.5 kHz and metal banging noises determined from Thresher before her loss. Task Group 89.7 Commander ordered echo ranging and fathometers secured to not interfere with the search and no further acoustic signals were detected, the Court of Inquiry determining

U.S.S. Seawolf (SSN575) recorded indeed possible electronic emissions and underwater noises.

Long story short, the court of inquiry concluded the submarine had probably suffered the failure of a salt-water piping system joint using silver brazing instead of welding. it was found later on all Subs freshly built 14% defectuous joints using ultrasound. Already on 30 November 1960 USS Barbel suffered such a silver-braze joint failure and a serious incident again happened to USS Abraham Lincoln during trials for the same cause. Later it was argued that the inability to blow the ballast tanks could be linked to excessive moisture in the high-pressure air flasks, freezing. Air dryers were later retrofitted to the high-pressure air compressors. It was also argued that a trainee was present instead of the experienced reactor control officers that day, R. Mc Coole, and he could have in that case prevent the use of a “by the book” procedure. After the accident Rickover (present at the court) further reduced plant restart times, called the the “scram” procedure.

As for the depht she exploded, at the tile it was established to 1,300–2,000 ft (400–610 m), albeit 2013 acoustic analysis concluded it was at 2,400 ft (730 m), which also reassured the Admiralty on the strenght of these pressure hulls, tailored to endure dives below 300 m or 1000 ft.

The SUBSAFE Program

The ill-fated Thresher, which had class known by her name until 1963 combined numerous advanced design features, her loss meaning quite a serious blow. The SUBSAFE program was instituted to correct design flaws and impose strict manufacturing and construction quality control. Thuis included a “teamwork” starting at the yard and ending in the crew’s training and safety features. For exmaple, the seawater and main ballast systems from the Sturgeon-class onwards, Benjamin Franklin-class SSBNs and three of the Flasher sub-class (SBC 188M) were redesigned and rebuilt. SUBSAFE came with a specific training of quality assurance inspectors which were intregrated with the engineering crew, tracking extremely detailed information about every component subject to sea pressure like joints in equipment carrying seawater.

Welding was imposing without brazing while and every hull opening larger than a set size was to be shut down by a remote hydraulic mechanism, this also improved sltealthiness. The success of this program should be put in light of the fact since then (and apart the Skipjack class Scorpion, designed before) no SSN was even lost again, so sixty one year so far without incident. Before that, the USN experienced 16 losses by accidents since 1915. If there was solace for the grief associated to all the family struck by the loss of Scorpion and Thresher, that was it.

The purpose of the SUBSAFE Program is to provide maximum reasonable assurance of watertight integrity and recovery capability of a Submarine. A culture of Safety is central to the entire Navy submarine community. This starts at the designers, and includes builders, operational crews as well as maintenance organizations. The SUBSAFE Program clearly defines non-negotiable requirements, requires annual training of personnel and then ensures compliance with reviews including audits and independent oversight. The annual training requirement includes review of past failures including the loss of Thresher.

In order to submerge, a submarine must be SUBSAFE certified. This is a process, not just a final step. SUBSAFE certification covers design, installed material, fabrication processes and as well as comprehensive testing. In these areas, documentation must be exact and based on objective quality evidence. This means that records back to original material composition as well as detailed testing results must be reviewed and retained throughout the life of a submarine.

To many the detailed requirements, rigorous training, constant review and questioning attitude, as well as the meticulous record keeping may seem excessive, but the program is successful. In the 48 years before SUBSAFE there were 16 non-combat related submarine losses, an average of one every three years. Since inception of the SUBSAFE program only one submarine, USS Scorpion SSN 589 – has been lost, and it was not a SUBSAFE certified submarine. In the 50 years since the inception of the SUBSAFE program, there has not been a loss of a SUBSAFE certified submarine. The SUBSAFE program has been utilized as a safety standard when analyzing the loss both Space Shuttles Challenger and Columbia.

The SUBSAFE Program is the legacy of those lost on USS Thresher – and it has made a lasting significant contribution to the Submarine Force, the United States Navy and to our Nation.

RADM J. Clarke Orzalli USN (Ret.), Chairman SUBSAFE Oversight Council 2010-2012

An immense Legacy: Sturgeon and Los Angeles

Plans of the Sturgeon class

The legacy of the Permit class is just immense. There was clearly a before and and after. An instant look at their hulls and sails makes it obvious and the general public would immediately recoignise a pattern. The Sturgeons were essentially lengthened and improved variants of the Thresher/Permit class, the extra length being in the operations compartment for longer torpedo racks, more Mark 37 torpedoes, 21 torpedoes instead of 16. Top speed was reduced to 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) submerged and no less than 37 were procured until 1975. As for the Los Angeles class, which development started in 1967, they were approximately 50% larger than the Sturgeons with “major improvements” in stealth and speed to too could keep up with carrier battle groups. 62 were built from 1972 to 1996 and they still made the bulk of today’s US submarine fleet.

Career of The Permit class

USS Permit SSN-594 (1961)

USS Permit SSN-594 (1961)

Permit was laid down at Mare Island Naval Shipyard on 16 July 1959, launched on 1 July 1961 and completed on 29 May 1962. After 5 weeks of trials, Puget Sound area, 3 weeks at Mare Island for setting up the SUBROC missile system she sailed along the California coast in spring 1962, but 30 mi (50 km) west of the Golden Gate she collided with the freighter “Hawaiian Citizen” on 9 May. Her captain was relieved from command. Later that year she made her shakedown in the San Diego area and aft final acceptance trials (January 1963) took part in an evaluation of the SUBROC system with a first sucessful fire on 28 March. 1964-1965 were spent in more testing/training and after her overhaul at Mare Island, winter 1966 from May to July she made a WestPac, stopped at Pearl Harbor and back to San Diego on 13 August, local waters operation until Xmas.

She had another overhaul at Mare Island in 1967, and was homeported to Vallejo. Late November saw her in trials off Puget Sound, back to San Diego on 12 December and operating there until 22 April, then she sailed for the Pacific and “special operations” until 26 June. From 24 July to 1 October she made another of such assignment, followed by local operations. No logs for the 1970s.

In late 1982, she collided with USS La Jolla whereas USS Permit operated at periscope depth, 30 miles off San Francisco. La Jolla had her rudder damaged and Permit had a keel paint scratch.

Permit was Decommissioned on 12 June 1991 after 29 years of serviuce (the longest) she was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program on 20 May 1993.

USS Plunger SSN-595 (1961)

USS Plunger SSN-595 (1961)

USS Plunger SSN-595 was laid down on 2 March 1960, launched on 9 December 1961, completed on 21 November 1962. She tested her systems of Puget Sound on 27 November and departed Mare Island on 5 January 1963 for her shakedown to Pearl Harbor, later homeported at Mare Island and testing her sonar and the fire control system (FCS). She was later homeported again to Pearl Harbor, as flagship of ComSubDiv 71, 1 April 1963. She operated on the West Coast in spring and summer, but sailed to Wake Island on 15 September 1964 at the missile firing range.

She was in Pearl Harbor by January 1965, and made a demo to Dr. Donald Hornig (Special Assistant to the President for Science and Technology). By May she was at C/S-17, Wake Island (SubRon Operational Training Test). In September, she made a full WestPac deployment until mid 1966, notably precticing with her AN/BQQ-1 sonar, sailing to Okinawa and Subic Bay. She also made oceanographic and port surveys.

With SubRon 7 in 1967 she was intrumental to improve ASW readiness of the Pacific fleet and on 6-22 March, was in a large ASW exercise. She was at Puget Sound for a six months overhaul in 1967 and back to Pearl Harbor on 1 February 1968.

She made another WestPac deployment, and became the first SSN to visit Japan at Yokosuka, amidst protestations. By January 1969 she was in “special operations” for 2 months, back home in mid 1969, earning a Navy Unit Citation for her North Pacific tour under Cdr. Nils Thunman (persumably in the waters of the Kamchatka and Vladisvostok). In her 1968-1970 WestPac she stopped at Yokosuka, Guam, Sasebo, Okinawa, Subic Bay, Pusan, Hong Kong. She was the test bed for the new “SubRoc” seen above, tested in anti-submarine operations over 25 miles.

She had her Commander Alvin L. Wilderman washed overboard from the bridge in a storm off San Francisco, 30 November 1973.

From 1970 to 1973 she was in WestPac and Vietnam and by fall 1973 on sea trials off California after her overhaul. Her next WestPacs went on until 1980.

She had her largest mid-life refit in Bremerton (1980-1982) notably receiving the BQQ-5 Sonar, with sea trials in 1983, Westpac from January to June 1984. She had another collision with a freighter off Southern California at periscope depth, early 1985. Her bow and sonar dome needed repairs in drydock, spring 1985.

In 1986 she won the Marjorie Sterrett Battleship Fund Award and became the 1st warship to win both the Sterrett and the Arleigh Burke Awards. That year she made another Westpac to Yokosuka and Subic Bay, and R&R in Hong Kong, plus naval exercises with SKorea and JMSDF fleets, and “special operation” with a second Meritorious Unit Commendation awarded. In 1987 she was noted regularly for “for excellence in virtually every major inspection” earning the Battle Efficiency award. Under decommissioned she was 60% of her time at sea, making her final WestPac deployment in 1988, visiting Japan and the Philippines, Guam and stopping at Chinhae, South Korea plus another 2 months “special operation” and a 3rd Navy Unit Commendation. After a pariod off San Diego by December 1988 she made her final “special operation” during Xmas, and final Operational Reactor Safeguards Examination, then R&R in Pearl Harbor.

She was deactivated under command of Captain William Large, commissioned still from 10 February 1989 to 3 January 1990, stricken after 27 years of service, recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 8 March 1996. The San Diego Tribune noted her as the most-decorated submarine in the Pacific Fleet, most-decorated warship in San Diego.

USS Barb SSN-596 (1962)

USS Barb SSN-596 (1962)

USS Barb SSN-596 was laid down at Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi on 9 November 1959, launched 11 Feb 1962 and completed on 24 August 1963. She departed Pascagoula on 28 September for her shakedown cruise, west coast, round-trip voyage to Hawaii and Vallejo, Puget Sound for more trials 30 October-19 November. On 17 December she entered Mare Island Naval Shipyard for fixes over nine months, into 1964. On 1 July 1964 she was homeported from Vallejo to Pearl Harbor, Submarine Division 71. On 1 December 1964 she became flagship for the Commander, Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet. Between 9 June and 25 July 1965 she had sonar fixed at Mare Island but stayed for two years in Hawaiian waters. By late 1966 she returned to the West Coast, San Francisco for weapons alignment tests at Dabob Bay and more fixes at Puget Sound, back to Hawaii late October.

In 1967–1969 her routine ceased whe she was deployed for first Far East deployment on 9 May to Naha, Okinawa, 22 May and Vietnamese waters for a first wartime tour of duty with Task Group 77.9. She had R&R in Singapore and provisional resupply/upkeep HP at Yokosuka on 19 June. She was back for “unspecified operations”. She made several deployments and also stopped to Guam and Subic Bay. She was in the Hawaiian Islands in 1968 and on 11 April 1968 while at sea she reported a large part of the Soviet Navy’s Pacific Fleet using active sonar, looking for K-129.

In late May 1968 she had her regular overhaul at Pearl Harbor along 1969, 8 December.

By January 1970, she tested her weapons off Washington state, back in Hawaii by February. She ade another WestPac from 2 January 1971 with special operation, Yokosuka, Subic Bay and again four weeks of special operations until back at Subic Bay on 28 March. Later she sailed to the Marianas, Guam and on 1 May, eight weeks of special operations until back at Pearl on 25 June.

After her extended shipyard availability she stayed in fixes an repairs in 1971-1972, trials in the spring of 1972.

On 22 May 1972 she was in the Marianas.

On 8 July she was rushed at sea when cornered by the Typhoon Rita approaching Guam. A B-52 SAC Stratofortress intending to fly over the storm but the crew bailed out. An C-97 Stratofreighter spotted spotted them, radioed their location and both Barb and Gurnard (SSN-662) were ordered there, but Barb was the first on site at 23:00, surfacing 12 miles (19 km) from the reported location in heavy weather but but did not succeed to recue them until the following day. They eventually saved the Electronic Warfare Officer, copilot, and navigator in 40-foot (12 m) waves and later saved Airman Daniel Johansen (gunner). USS Gurnard saved Captain Leroy Johnson but Lt. Colonel J.L. Vaughn (radar navigator) did not survived the night. Barb was presented a Meritorious Unit Commendation and the man that jumped overboard to secure a tow line was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

From January to early March 1973, Barb was in training missions and had a three-month operational cruise, stopping at Pusan in May. After a stop to the Marianas she was back to Pearl Harbor. By September she took part in RIMPAC 73. She had an overhaul at Mare Island from 1 March 1974 over 20 months, homeported to San Diego, in trials by November 1975, and 16 months of local ops. She started her next Westpac by late 1976 until early 1977.

She took part in RIMPAC 77, sailed to Pearl Harbor and Subic Bay working with TG 37.9 and TG 77.3. She was deployed off Chinhae in Korea and trained with the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and South Korean Navy, and R&R in Hong Kong on 11-14 April, sailing to the Marianas, training with the Royal New Zealand Air Force and USN patrol aircraft, then Guam and two special operations until June, Subic Bay, R&R and back home on 7 July.

Next she became the test platform for the Tomahawk cruise missile by late October, and until the end of 1977, second quarter of 1978. She started antother WestPac on 27 September 1978. She was back in Hawaii and Subic Bay, then Japan and a month-long special operation, stopping at Chinhae the last day of 1978. Next she was in the Marianas, Guam and by February Subic Bay and MULTIPLEX 2-79. She was back home on 17 March. In May she resumed training routine up into the first weeks of 1980.

By 7 February she was deployed in the mid-Pacific and RIMPAC 80, based at Pearl Harbor. On 21 July, she started her major overhaul at Mare Island until late 1982. She received the complete SUBSAFE package and she had over 27 months more for issues fixes and four sea trials, final fixes in dry-dock by early 1983. No records next.

Barb was one of the earliest decommissioned on 20 December 1989 after 26 years of service and 3 months, recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 14 March 1996.

USS Pollack SSN-603 (1962)

USS Pollack SSN-603 (1962)

She was laid down at New York Shipbuilding, Camden, New Jersey on 14 March 1960, launched on 17 March 1962 and completed 26 May 1964.

Pollack reported to the Atlantic Fleet, joining Submarine Squadron 4 in Charleston. After shakedown, Caribbean, she had a six-month full evaluation. Most of 1965 was in evaluating of ASW tactics, destroyer vs. submarine, anti-shipping missions, earning the Navy Unit Commendation.

1966 saw more coordinated ASW operations as well as 1967 with weapons tests. On 1 March 1968 she was homeported to Norfolk, first of Submarine Squadron 10, and she remained there until 1970.

After a refueling overhaul at Charleston she was transferred to the Pacific Fleet and SubRon-3, stopped at Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, transited Panama and reached San Diego in March 1975.

In 1979 she had a major refit at Mare Island, Vallejo and back to SubRon 3 and the tender Sperry (AS-12) in San Diego in 1982. In 1988, she transferred to SubGroup 5, Mare Island (reserve) and was decommissioned on 1 March 1989 after 24 years and four months of service, recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 17 February 1995.

USS Haddo SSN-604 (1962)

USS Haddo SSN-604 (1962)

SSN-604 was laid down on 9 September 1960, launched on 18 August 1962 and commissioned on 16 December 1964 and decommissioned on 12 June 1991 after 26 years of serevice and 4 months.

After shakedown off New London by January 1965, she was homeported to Charleston on 8 February, SubRon 4. She operated with the Atlantic fleet, notably in the Caribbean but on 7 July departed for her first Mediterranean tour with the 6th fleet. Se took part in numerous exercises there and with NATO countries, back home on 7 November. The same repeated in 1967.

She was awarded the Navy Unit Commendation for 1966 and Meritorious Unit Commendation for 1967. For 1968-1969 she was awarded the Battle Efficiency “E”. Next she had her 18-month “subsafe” overhaul at Charleston from August 1969 to April 1970. She was homeported to New London, part of SubRon 10 from 1971 to 1973. In 1972 she made the 6-month Mediterranean deployment for any US SSN, back home prior to Christmas.

From August 1973 until December 1975 she had her refueling overhaul at Ingalls Shipyard, Pascagoula, transited Panama on 13 February 1976 to HP San Diego and the Pacific Fleet, SubRon 3.

Spring of 1977, saw the start of her first WestPac, six-month deployment. In 1978 she in was in Selected Restricted Availability at Puget Sound and made another WestPac, stopping in New Zealand, back in 1979.

She was back Mare Island Naval Shipyard for February 1980. In August she was deployed to the Indian Ocean as the middle east crisis developed. She visited HMAS Stirling in Western Australia on 16–22 December 1980 and back to San Diego in February 1981. In July she made another WestPac, back in late October 1981. In Mare Island from April 1982 she had an extensive modernization and overhaul until January 1984.

From February to August 1985, she made another WestPac, Japan, Hong Kong, earning another Battle Efficiency “E” for 1985. She had another Westpac from August 1986 to February 1987 followed by local operations and a last Selected Restricted Availability in San Diego until March 1988.

After 2-month ASW operation by June-July 1988 she stayed at San Diego From February 1989 until February 1990 in intensive operations and last 6-month Westpac between Korea, Japan, Hong Kong and the Philippines. She made then the longest continuously submerged run. The fall-winter of 1989 and 1990 saw her deployed in the largest Pacific Fleet naval exercise, PACEX-89, followed by 2 months ASW ops. in the northern Pacific. After commissioned and being stricke, she was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 20 June 1992.

USS Jack SSN-605 (1963)

USS Jack SSN-605 (1963)

She was laid down on Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on 16 September 1960, launched on 24 April 1963 and commissioned on 31 March 1967. Jack was 20 feet (6.1 m) longer and became the led-ship of her own sub-class, using an experimental direct-drive plant and two contra-rotating propellers on concentric shafts. The latter were smaller, using termed blade rate and had less cavitation when interacting with the hull’s own uneven wake while thrust was preserved. However the specialized turbine and extra shaft watertight system was not an effective alternative. In the end, a much larger and scythe/skew-shaped propeller interacting more slowly with the wake was found the best solution, until the introduction of the pump-jet on the late 1980s Seawolf-class.

Her service logs are missing.

By late September 1982, USS Jack sailed to Portsmouth in Kittery for a 27-month overhaul but while in dry dock, she had a casualty when a man conducted a hydrostatic test of the oxygen banks using Freon (R-12). A shipyard worker was unable to get out of the engineering space in time and succumbed to oxygen deprivation. USS Jack was decommissioned on 11 July 1990 after 23 years and three months of service (the shortest). She was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 30 June 1992.

USS Tinosa SSN-606 (1962)

USS Tinosa SSN-606 (1962)

USS Tinosa was laid down on 24 November 1959, launched on 9 December 1961 and commissioned on 17 October 1964. After shakedown off New London and availability at the yard from April to June 1966 she made her shakedown cruise to Faslane in Scotland and back to the Caribbean Sea plus an overhaul from March through June 1967. Next she served at the Naval Underwater Sound Laboratory at New London in 1968, based at Port Everglades. She visited also Bermuda and resumed operations off New London, eastern seaboard and Caribbean into 1969. She had her major overhaul with the SUBSAFE package next, followed by trials by December 1971, and ops. on the eastern seaboard-Caribbean until mid-1972. By July she toured northern Europe before her first Mediterranean deployment, 6th Fleet, stopping at Sardinia and Holy Loch and back home in December, then ran a test project sponsored by MIT.

Amidst local ops. she had a 3 days visit to the United States Naval Academy by late April for midshipmen, and moved to New London alongside Fulton (AS-11), twice deployed to Bermuda, Andros Island and she took part in joint US-Canadian ASW exercise in December.

Tinosa departed made another Med TOD from 19 May and visited Bizerte from 24 June to 1 July, first SSN to visit Tunisia.

Back to New London on 16 November she was in local ops. to late February 1975. She shifted ops. to Charleston and off the Florida coast. She had her major overhaul at Ingalls Shipbuilding from late 1975 to 12 December 1977 and resumed operations with the Atlantic Fleet, then a combined exercise with the RCN off Florida in mid-April. She departed for her 3rd Med TOD on 13 September and was upkeep in La Maddalena, Sardinia, after a large NATO ex. with British, Italian, and Turkish vessels. In 1981 Tinosa visited Frederiksted St. Croix in October. On 4 January 1988 she had 6 months of operations in the Medi. and by October 1988 left New London for 60 days of North Atlantic Operations and the Arctic. She was decommissoned on 15 January 1992 after 27 years and 3 months. She was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 15 August 1992.

USS Dace SSN-607 (1962)

USS Dace SSN-607 (1962)

Dace was laid down at Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi on 6 June 1960, launched on 18 August 1962 and completed on 4 April 1964. She was the second to be named for one of the small North American fresh-water fishes of the carp family. When launched she was sponsored by Betty Ford, wife of future President of the United States Gerald Ford. Her lgs are missing. Admiral Kinnaird R. McKee, USN, commanded USS Dace. In the 1960s and 1970s, she conducted classified operations that were explained after declassification in Blind Man’s Bluff by Sontag and Drew, 1998. She was decommissioned early on 2 December 1988 after 24 years and seven months, and she was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 1 January 1997.

Guardfish SSN-612 (1963)

Guardfish SSN-612 (1963)

USS Guardfish SSN-612 was laid down at New York Shipbuilding, Camden, New Jersey on 13 February 1961, she was launched on 15 May 1965 and completed 20 December 1966. She departed Camden on 15 February 1967 for shakedown training off San Juan. After this she sailed through the Panama Canal to join Subron 7 in Pearl Harbor. She took part in Pacific operations cranking up 40,000 miles (64,000 km) this first year.

On 13 January 1968, Commander H. A. Benton was in command as she multiplied exercises and in 1970 Guardfish she returned to the Atlantic for her overhaul at Ingalls and returned to the Pacific and received the Navy Unit Commendation for new season here.

The Soviet subs 1972 Vietnam showdown

In the summer of 1972 while deployed in the Sea of Japan as on 9 May the Vietnam War bounced after the Paris peace talks failed, North Vietnamese harbors were targeted, and a blockade was ordered with Guardfish deployed here but warned of the presence of possible Soviet submarines in the area trying to interfere. She stayed at periscope depth close to Vladivostok to monitor such sorties when in the evening of 10 May she had surface contact out the channel at high speed, heading for her. As the contact closed she identified her as a Soviet Echo II-class sub. But she passed nearby, submerged and was soon followed at high speed by SSN-612.

For two days she was on her tail as the Soviets went to periscope depth to receive orders. Guardfish slowed to extend her sonar detection range and detected 2-3 other Soviet submarines nearby.

When the Echo II resumed her trip to the southern exit of the Sea of Japan, Guardfish Cdr. broke radio silence, notified the commander while Washington D.C. tried to assess the threat. President Nixon and his National Security Advisor had a briefin while the US sub’s high frequency radio transmissions could be both detected and located by the Soviet electronic intercept network. Instead a P-3 Orion flew covert missions over USS Guardfish in projected location for reports via short range, ultra high frequency at periscope depth or via SLOT buoys. This was all new and kept communication secret while the sub made vital “Picket duties”.

Every available US submarine of the Pacific was deployed to protect US aircraft carriersoff the Vietnamese coast and try to stop these incoming Soviet submarines. While in the Philippine Sea the Echo II turned southwest for the Bashi Channel between Taiwan and north of Luzon, for the South China Sea. Guardfish continued to tail her but to avoid collision the skipper changed depth to 100 meters (330 ft), typical of Soviet subs. She soon detected another US submarine in the north diving at high speed.

On 18 May she followed the Echo II into the South China Sea until 300 miles (480 km) off Luzon and for 8 days established a rectangular patrol area 700 miles (1,100 km) from U.S. carriers off the Vietnamese coast, beyond the 200-mile range of her missiles. Meanwhile President Nixon went to Moscow for a summit with Brezhnev and Henry Kissinger informed him of the knwoledge of the position of his subs and warning of their presence too close to the Vietnamese War Zone. Ultimately the the Soviets recalled their submarines.

Thius was not completely over as the Echo established a second patrol area in the Philippine Sea, a place with the worst possible acoustical properties, budy with merchant traffic and massive biological noise, frequent rain showers so contact was hard to maintain, Guardfish had to trail closer and closer. Then the Echo came unexpectedly to periscope depth and visually detected Guardfish while also surfaced to establushed contact. Both maneuvered at high speed and the Echo was lost while Guardfish returned to Guam after a 123 days wild chase. This was all declassified in the 1990s.

Guardfish also underwent regular overhaul at Pearl Harbor alternated with WestPacs. From June 1975 she was homeported to Vallejo, California.

1973 Reactor Accident

At 370 miles from Puget Sound between Pearl Harbor and Bangor she had a leak in the primary coolant of her S5W nuclear reactor with the crewman performing a leak test on a valve accidentally leaving coolant to flow out from the primary loop until it was discovered. She had to surfaced to ventilate. Five crewman were contaminated by radioactive steam and were heliported to the nearest hospital for decontamination at Puget Sound. This even was classified.

Guardfish was in Mare Island from August 1975 for refueling, back in July 1977, homeported to San Diego, SubRon Three. She also had her SUBSAFE overhaul and made her trials and test depth in 1977. In January 1979, she completed a new six-month WESTPAC and special operations, being the rest to test a digital sonar in the Pacific, earning a Meritorious Unit Commendation. In 1980 she made another six-month Westpc and was awarded another Meritorious Unit Commendation. From 16 to 21 May 1980 she was in Australia, HMAS Stirling (Rockingham).

In the summer of 1983 she won the ASW “E” and Communications “C” for 1982-83 and was awarded the Silver Anchor Award in 1984 for her crew retention program. She had a short overhaul at Mare Island from September 1983 to August 1985.

In 1986 she made another six month Westpac concluded in January 1987, and won a 3rd Navy Unit Commendation, second Silver Anchor “E”, ASW “A” , Supply “E” and Arleigh Burke Fleet Trophy FY87.

She made her two last Western Pacific deployments until October 1990, being awarded the Deck Seamanship for 1988, 89 and 90 plus the Silver Anchor and another Battle “E” FY1989.

Under Commander P. M. Higgins she made a Northern Pacific Deployment, homeported by June 1991 to Puget Sound, entering inactivation in July 1991. She was decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 4 February 1992 after a quarter of century, and was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 9 July 1992.

USS Flasher SSN-613 (1963)

USS Flasher SSN-613 (1963)

USS Flasher SSN-613 was laid down at Electric Boat and launched 14 April 1961 and commissioned on 22 June 1963. 22 July 1966. She was extensively modified with the lengthening of her hull, sail, SUBSAFE as first submarine certified. First captain was Commander Kenneth M. Carr and US Representative George W. Grider of Tennessee, former commanded of WW2 Flasher (SS-249) presented Cdr Carr the original Battle Flag, mounted and hung in the crewsmess.

She was homeported to Pearl Harbor on 23 September 1966, and on 7 October was visited by Mr. Elkichi Kambayashiyama at the head of JSDGF with COMSUBPAC Rear Admiral John H. Maurer.

By late January 1968 she joined the emergency crisis fleet assembled after the capture of USS Pueblo by the North Koreans in the Sea of Japan, Wonsan. A small ice flow snapped her periscope top. She sailed to Guam for repairs and back to North Korea. She stoppd at Yokosuka and back to Pearl harbor, being awarded the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal and Korean Defense Service Medal.

First WESTPAC was on 25 April 1969, awarded her first “E” on 4 July 1968. She won another 1 July 1969. On 2 December 1969 she had a first Meritorious Unit Commendation for her 1967-1968 Vietnam deployment.

On 15 June 1970 she had her first major overhaul at Pearl Harbor, completed by 12 June 1971. In November 1971 she started he new WESTPAC via Guam, Okinawa; Yokosuka, Subic Bay and Hong Kong, back in June 1972. 1 July saw her 3rd “E”, on 13 July 1972 received she was visited by the Secretary of the Navy John Chafee. On 19 August 1972 she was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation just as CDR R.F. Bacon took command (future Vice Admiral and Assistant CNO for Undersea Warfare), she participated to RIMPAC 72 in September.

On 2 March 1973 she received Navy Unit Commendation for 1970–1971 and started another WESTPAC in early 1973 until 24 December 1973, being awarded a fourth “E”. In June 1974 she made her first 2-month special operation.

She had her second overhaul at Mare Island from 11 January 1975, homeported there, home of SubRon 3 until 16 December 1976, then HP San Diego on 22 December 1976.

In August 1977 she was resent for the Seattle Seafarer Festival and made a 3 month special operation from April to June 1978. By January 1979 she had her SRA at Mare Island until 29 March 1979. In June 1979 she was at the Portland Rose Festival and on 1 July 1979 she earned her 5th Battle “E”.

On 12 November 1980 she had a 2nd Meritorious Unit Commendation and on 5 November 1982 was awarded a third one for 1981-1982. while crew earned the Navy Expeditionary Medal.

She made a 3-month special operation (August to November) in 1982, commenced her third overhaul at Mare Island on 9 May 1983 until 26 March 1985, homeported back to San Diego, and by March 1986 started another WESTPAC deployment, until August 1986 earning a Navy Expeditionary Medal.

She made her last WESTPAC in April 1990 then 2-month special operation in August–October 1990, and March–May 1991, reaning her 5th Meritorious Unit Commendation in 1991 and by 18 June 1991 saw an Inactivation Ceremony at Naval Base Point Loma, in San Diego. She was decommissioned on 26 May 1992 after 25 years, recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 11 May 1994. She was the most decorated SSN in the fleet so far.

USS Greenling SSN-614 (1864)

USS Greenling SSN-614 (1864)

SSN-614 was laid down on 15 August 1961, she was launched on 4 April 1964 and completed on 3 November 1967. She was one of three selected Thresher-class for conversion into the “improved Thresher class” SBC-188M, with SSN-613 Flasher and SSN-615 Gato, lengthened to house SUBSAFE) modifications and others (with improved crew space, and additional equipment). By 27 May 1968, Greenling her fleet training exercise was interrupted by the search for USS Scorpion (SSN-589), designated Commander of the SAR Task Element until 12 June 1968.

She spent most of her career with SUBRON 10, homeported in Groton.

On 27 March 1973 she made a dive below her test depth off the coast of Bermuda, having a faulty depth gauge as the diplay showed by the other gauge revealed an error, but she surfaced safely. She was probably 150-200 feet from crush depth and was sent to Portsmouth Shipyard for examination.

Spring 1983, show her passing a Tactical Readiness Exam (TRE) in the Caribbean when she went in a full down-angle with a flank bell which needed the reactor’s main coolant pumps switched from slow to fast speed but windings did not open properly, so she had a fireball in the switchgear in her auxiliary machinery space, upper level. She was dead stopped and aunable to surface. Normal ballast tank blow failed, but the emergency blow succeeded and slowly stopped the descent, allowing her to later surface but in rough seas. She could no open her aft escape hatch to bring fresh air and cooling into the spaces but the crew rotated 6 hours back aft with no AC, until the planes cooled off. She had 2 weeks of repairs at Roosevelt Roads and sailed back to New London surfaced. Sailors later called it the “The BBQ of 83”. She was decommissioned 18 April 1994 26.4 and recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 30 September 1994. Her control room Equipment was used to buid a simulation control room exhibit at the Naval Undersea Museum in Keyport, Washington.

USS Gato SSN-615 (1964)

USS Gato SSN-615 (1964)

Gato was laid down on 15 December 1961, launched 14 May 1964, commissioned on 25 January 1968 under command of CDR Albert Baciocco. On 15 November 1969, she collided with the Soviet submarine K-19 in the Barents Sea under 200 feet (61 m). The impact destroyed K-19’s bow sonar and cover of her forward torpedo tubes, repaired while Gato went back home relatively undamaged, after resuming her patrol.

She was the first SSN to circumnavigate South America, first to navigate the Strait of Magellan in her 1976 Unitas participation under CDR Robert Partlow. She was decommissoned on 25 April 1996 after 28 years and two months of service. She was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program.

USS Haddock SSN-621 (1966)

USS Haddock SSN-621 (1966)

Haddock was laid down at Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi on 24 April 1961 and launched on 21 May 1966 completed on 22 December 1967. A long gap to allow deep modifications following the experience gained with USS Permit and the few SSNs of that class. When commissioned she was under command of Stanley J. Anderson and underwent sea trials in the Gulf of Mexico. She crossed the Panama Canal in Jan-Feb 1968, to Puget Sound, and assigned to Submarine Squadron 3, homeport San Diego in 1969. After her first Western Pacific deployment she was homeported to Pearl Harbor and had an overhaul completed in 1972. She was awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation for her 1973 deployment, and alternated until 1977 Westpacks and local waters exercises. She had a resupply and refit in 1973 and in 1977 had a 19-month overhaul in Mare Island, HP San Diego, Submarine Squadron Three. By early 1981, she took part in Ready Ex-81 and completed her 7th WestPac on 23 December 1983. She had her third overhaul at Mare Island in October 1984 and was back to San Diego in February 1987, erning a Battle Efficiency “E” for 1988.

She made her 11th Westpac from July to October 1991 and was decommissioned on 7 April 1993 after 25 years of service, recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program.

Read More/Src

Various 1960s US subs, to scale

Books

Links

history.navy.mil/ ssn-593-.html

navsea.navy.mil 59th-remembrance-subsafe-program

news.usni.org after-thresher-…

navypedia.org/s us_ss_thresher.htm

globalsecurity.org ssn-594.htm

oneternalpatrol.com uss-thresher-593.htm

navysite.de/ssn/ssn605.htm

pressandguide.com thresher-sank-60-years-ago-killing-entire-crew/

text-message.blogs.archives.gov patrol-a-tribute-to-the-uss-thresher

nytimes.com nuclear-sub-safe-after-diving-error

web.archive.org/ www.ussgreenling.com/

history.navy.mil/ uss-thresher-selected-documents

www.guardfish.org

threshermemorial.org/

weaponsystems.ne UGM-84+Sub+Harpoon

homeport.smithlc.com/

en.wikipedia.org Permit-class_submarine

Videos

See also on sub brief

Model Kits

sdmodelmakers.com thresher-permit-class

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign