HMS Audacity (1941)

WW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classThe first British RN Escort Aircraft Carrier

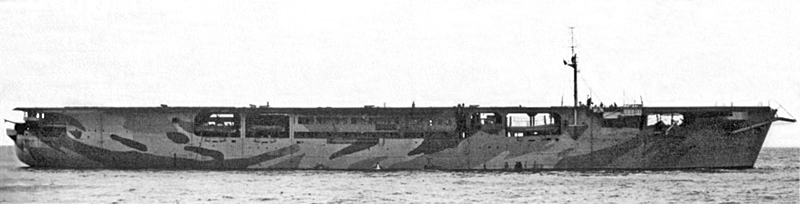

The Royal Navy’s first escort carrier was for most of her life never a carrier at all. She started life as SS Hannover which served as a regular cargo ship for Germany, but was requisitioned in January 1941 by the Royal Navy and converted quickly to act as a test bed for a light carrier design in order to better cover Atlantic convoys in the height of the Battle of the Atlantic. The conversion was complete in June, so quick that her aircraft facilities were barebone: No hangar, eight planes including two in reserve at a time, meaning that only six aircraft were operational at all times from her small deck, only allowing either landing or taking off, but not both. Overall not very successful, her conversion did bear fruit in the MAC design later.

She was the first operational British escort carrier, second built in the world, beaten a mere 19 days by USS Long Island. She entered service as HMS Empire Audacity with North Atlantic escort program.

Nevertheless, this was quite instructive and she went on escorting four convoys before being sent to the bottom by U-751 on 21 December 1941 with HG 76.

Genesis of the design

The “quick carrier conversion” idea

The idea of producing a quick escort carrier conversion in the RN was not new: The admiralty saw the advantages of having a permanent air patrol over the convoy, both as a CAP (Combat Air Patrol) to shoot down incoming Luftwaffe spotters, such as flying boats and the massive FW.200 Condor, or to spot submerged submersibles in calm to moderate weather when any shape could be identified with trained eyes less than 10 meters (32 feet) under the surface. Thus, there was no need for a large aircraft group. Only 1-3 aircraft in the air at all times was enough.

It was also estimated that with a deck around 150 m or 492 feet long, any FAA model could take off unassisted. This eliminated the need for a catapult, simplifying conversion. The base principle for the operation was that three planes were to be stored permanently aft, two on either side, wings folded, and one in front, wings deployed and ready to depart to create a permanent state of readiness over the convoy. By night, they would be simply carried back below the hangar to be serviced while new fresh aircraft were brought forward.

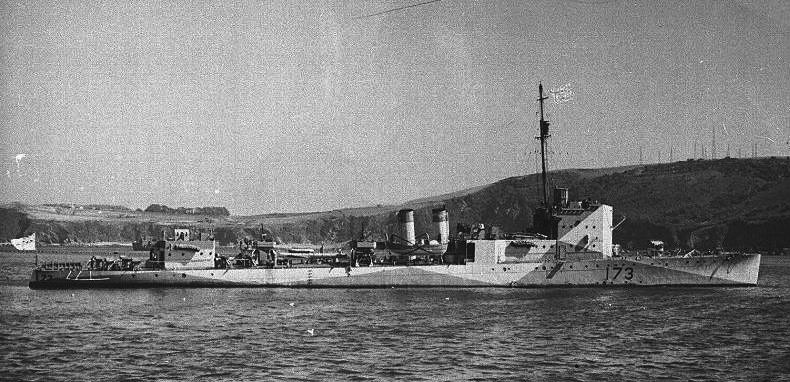

USS Long Island, converted and operatioal 19 days earlier. Contrary to the latter, she was larger than a C3 cargo and had a greater aircraft capacity, later even further enhanced on the Bogue class (Archer/Attacker in British service).

There would also be no island to facilitate construction and the ship was to have a flush deck. Like early carriers, she was to be given truncated boilers to bring smoke over the side, and engineers could simply turn the existing storage areas into the main hangar, adding a hangar deck and keeping the lower storage bays as utility ones, for a payload of spares for the planes. All this, as assured by Royal Engineers, would ensure a five month conversion, to be carried out on any merchant vessel fast and recent enough.

At least that was the base principle, and not much more info was available on the order itself. Later on, extreme conversions were made on further “Empire Ships”, MAC’s, or “Merchant Aircraft Carriers” which would carry three planes parked on deck, with the merchant area preserved on top to act also for its intended purpose.

Hannover before her capture

The opportunity: SS Hannover/Sinbad/Empire Audacity

Hannover, trying to scuttle herself photographed before capture

SS Hannover was a 5,537 GRT cargo liner. She was built in Germany for the Norddeutscher Lloyd, by Bremer Vulkan Schiff und Maschinenbau (Vegesack), and launched on 29 March 1939. Before the war, she made her first trip to the West Indies, her first “banana run”, and was registered in Bremen.

When the war started in September, she was just about to depart when Captain Wahnschaff was informed of hostilities. He chose to take refuge in Curaçao, the Netherlands Antilles, which at the time were still neutral. In March 1940 as it was now clear Hitler was close to invading western Europe, he received an order to attempt to return home, acting as a blockade runner with her initial load. Unfortunately, most of the Caribbean was under French and British control, and she was sighted en route between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, close to the Spanish possession, on the night of 7/8 March, by the HMS Dunedin and HMCS Assiniboine, with both being dispatched to watch over the area precisely due to a possible breakout of German shipping in the area.

Hannover was ordered to stop, but her captain ignored the order, counting on his speed to try to reach the neutral waters of the Dominican Republic. However, Dunedin and Assiniboine pressed on at full speed and eventually intercepted her, bringing their guns to bear on the merchant. Next, Captain Wahnschaff ordered that the seacocks be opened and his ship set afire. However, it was too late. Dunedin closed while a landing party of sailors, well armed, prepared to board the Hannover. The crew of the latter, being mostly unarmed, quickly surrendered and the captain was forced to accompany the boarding party at gunpoint into his ship forcibly close sea cocks. The flood was quickly mastered while the crew was placed under custody and the second in command of Dunedin took charge of the ship’s provisional staff.

Now Hannover was officially a war prize and was taken under tow, however, four days were needed to put out the fire that had been started on her deck before she was boarded. Towed to Jamaica and arriving at Kingston on 11 March under the command of Acting Lieutenant A. W. Hughes, a damage assessment was quickly made, but it was found that anything serious had been confined to her electrical system, which needed full replacement and the cleaning of all burnt sections. Most importantly her hull integrity and powerplant were intact.

As a war prize, she was soon pressed into merchant service again, renamed Sinbad with UK Official Number Code Letters, under the British merchant marine flag. The cargo was also part of the loot and consisted of 29 barrels of pickled sheep pelts, offered for sale by a tender in August 1940 in Kingston. The crew became POWs until the end of the war in Jamaica.

On 11 November 1939, the Sinbad was renamed “Empire Audacity” now reclassed as part of the “Empire ships” by order of the Ministry of War Transport, she was recommissioned as an Ocean Boarding Vessel. The latter operated with 17 OBVs, taken over by the Royal Navy to enforce wartime blockades by intercepting and boarding foreign vessels. Apart from HMS Cavina (August 1940) she was the jewel of the boarding fleet, being the fastest ship and the easiest to operate.

Her new port of registry became London and although she operated for the RN, the latter did not have the staff to operate her, so she ended up under the management of Cunard White Star Line Ltd to gather a merchant crew. However, between November and December, she was never recommissioned as an OPV. Indeed On 22 January 1941, the Admiralty decided she would be perhaps more valuable as a converted aircraft carrier. She was requisitioned for it and sent to Blyth Dry Docks & Shipbuilding Co Ltd to start work.

Conversion Design

Model of the Audacity

She was to be the lead “small carrier”, and pave the way for a possible solution to cover the vulnerable “Mid-Atlantic Gap”. The Empire Audacity was still at the time the largest ship handled at Blyth which was generally more used to 300 ft vessels. Townsfolk at the time were amazed by the ship’s size and wondered why her superstructure was being cut down at a time that the country was so short of merchantmen, in particular given that she was a modern and freshly repaired ship. Indeed the real conversion was kept secret.

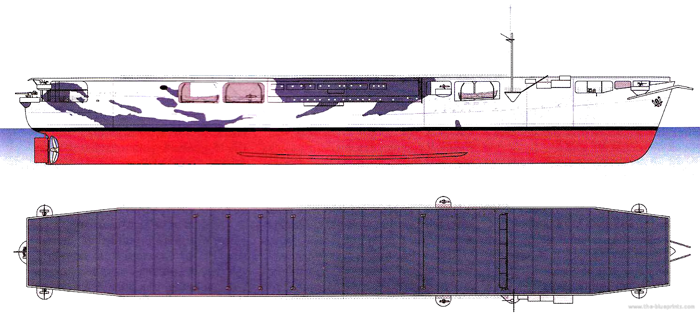

HMS Empire Audacity was recommissioned on the 17th of June 1941 as the Royal Navy’s first escort carrier. She would end as the smallest of the ships of her type, apart from MACs, carrying the smallest air park. By the end of her conversion, her whole deck was scrapped clean out, the island bridge was removed along with the storage areas hatches, cranes, and booms. A hanger was built on top and a flush deck was widened above. Engineers spent time devising the way to utilize her storage areas below best, building a unique lift to access the hangar, and studying the possibility of fitting a small command bridge;

The hangar height was calculated so as to use merchant ballast and still keep the metacentric height low enough for stability. In the end, the absence of an island solved the weight issue. Other works included truncating the exhausts from the machinery sections down the sides instead of building a vertical funnel. In the end, Audacity was finished with no proper hangar deck and an open conning position on the starboard side for command. She carried also little anti-aircraft armament due to the limited locations for it around the hull.

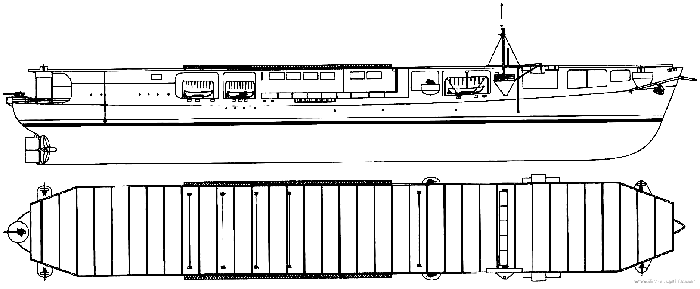

Hull construction & protection

The Audacity’s hull measured 441 ft 9 in (134.65 m) and 56 ft 3 in (17.15 m) originally as SS Hannover. When she was completed, her new flight deck was built overhanging above the original hull to maximize the area, at 467 ft 3 in (142.42 m) in length and 27 ft 6 in (8.38 m) in width at flight deck level. She carried originally a 5,537 GRT payload, but her full load displacement was 6,740 t standard, 8,370 t FL, with some sources stating it being as much as 11,000 tonnes.

Her protection was… mostly absent, as she was not built originally to integrate any. Compartmentation underwater was standard in comparison with any 1930s cargo ship and she had a double bottom, plus the sealable holds, but that was about it, making her very vulnerable to a torpedo hit. In the same fashion, while the deck was reinforced to support the weight of 5+ tons aircraft, it was hardly built up more, with 2 cm (1.1 in) at best of protection. She had no protection below either, as she had nothing thicker than the original weather deck, and of course, no armoured deck at the waterline level. To compound this, her ammo storage, avgas tanks, nor her steering compartment received any extra protection.

Propulsion

Profiles (from the blueprints.com)

After her conversion, her installed power was unchanged. It comprised the original one-shaft, 7-cylinder low revolution MAN diesel engine, which developed an output of 5,200 hp (3,900 kW). It was so efficient nothing was changed, which also helped the conversion time. Audacity ended up not being very agile as she had only a single propeller and rudder. However, the powerplant was powerful enough to reach 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph), proving fast enough to escort a convoy. Her exhaust vents were small, but the pipes were all forward of the prow, placed flush with the deck, and angled at 90° downwards in an “L” fashion to vent diesel fumes sideways, away from the ship.

Armament

4 inches (102 mm) gun

Installed on a sponson overhanging the stern, this single artillery piece was a standard DP (Dual) QF Mk.V HA gun, meaning it could engage both aircraft and ships if needed. It fired a 31 lb (14.1 kg) fixed QF or Separate-loading QF shell (exact caliber 101.6 mm). The gun used a horizontal sliding block with a hydro-pneumatic or hydro-spring ram (380 mm), at a muzzle velocity of 2,350 ft/s (716 m/s), giving it a surface range of 16,300 yd (15,000 m), and a ceiling of 28,750 ft (8,800 m). The 5 pound (2.27 kg) shell’s warhead was filled with lyddite.

AA armament

It comprised three types, spread around the vessel: A single 6-pounder (57 mm (2.24 in)) gun was installed probably on the single aft side sponson.

Also, she was given four QF 2-pounder anti-aircraft guns, which were located on forward sponsons.

Alongside these, she had four 20 mm (0.79 in) anti-aircraft cannons, installed in lower hull side sponsons and on her deck.

Aircraft facilities

HMS Activity top deck showing a line of seafires. On Audacity it was also too narrow for side parked aircraft. The wooden deck was not camouflaged also.

Her flight deck was 450 feet long and 60 feet wide, equipped with only three arrestor wires and one barrier close to the prow. In recovery mode, all Martlets were parked forward and the barrier was erected. Without a catapult, they were always parked aft, interlocked to make room, and ready to take off. Pilots stayed on deck waiting for an alert or below in heavy weather, with their planes solidly strapped and covered by a tarpaulin.

Other Features

She carried paravanes, stored on the forward deck, had two mors projectors and a main mast antenna, coupled with a Type 79B air warning radar. The latter was a primitive early-warning model developed before World War II, in fact the very first radar system deployed by the Royal Navy, introduced in 1939. Frequency was 43 MHz, with PRF 50 per second Beamwidth and 70° (horizontal), Pulsewidth 8-30 μs and power 70 kW for a range of just 30–50 mi (48–80 km) average. Needless to say this was quite small, just enough for scramble the fighters with a few minutes warning.

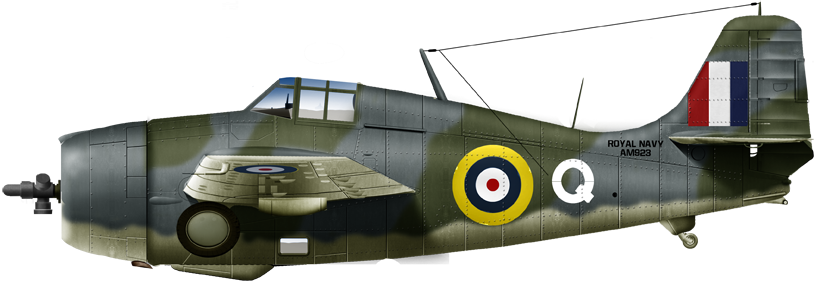

Air Group

Martlet Mk I (AM823) of No 802 Squadron Fleet Air Arm on board HMS Audacity, 19 dec. 1941, probably South African S/Lt Jimmy Sleigh.

She was capable of operating up to eight Martlet Mk I/II fighter aircraft parked on deck, but at the mercy of the elements at all times. However wfor her first sortie, she had six, and at the time she was sunk, this was down to three, one being lost previously. Nevertheless her air group, Squadron 802 (a fraction of it, based on HMS Glorious) became the Royal Navy’s top scorer unit against the German FW-200, and one pilot, S/Lt “Winckle” Brown, which survived her sinking, becoming the unit’s top ace. The first kills were performed by Sub-Lieutenants Patterson and Fletcher.

HMS Audacity (1941) |

|

| Dimensions | 142.41 oa x 17.14 x 8.38 m (467.3 x 56.3 x 27.6 ft.in) |

| Displacement | 9000 t standard, 11,120 t FL |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft MAN diesel, 5,200 bhp (3,900 kW) |

| Speed | 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Range | Unknown, likely 10,000 nmi at 10 kts |

| Armor | None |

| Armament | 1x 4 in, 1x 3pdr, 4x 2pdr, 4x 20 mm AA |

| Crew | 600 wartime |

| Air group | 6 operation Martlet I + 2 storage on deck. |

Scr/Read More

Links

royalnavyresearcharchive.org.uk/

.historyonthenet.com

naval-history.net

on navypedia.org

“LLOYD’S REGISTER, STEAMERS & MOTORSHIPS” (PDF).

“HMS AUDACITY”. Fleet Air Arm Archive

“A History of HMS AUDACITY”. Royal Navy Research Archive

u-boat.net

“H.M.S. AUDACITY (D10)”. Naval History, full logs

“HMS Audacity alias the MV Hannover”. Mike Kemble.

“Convoy HG-76 December 1941”. Mike Kemble.

british-forces.com

www.wrecksite.eu/

alchetron.com

Books

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-47

Ford, Roger (2001) The Encyclopedia of Ships, pg. 362. Amber Books, London.

Sturtivant, R & Ballance, T (1994). ‘The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm’ Air Britain 1994

The World’s Warships 1941 by Francis E. McMurtrie (1944). Janes London 1941 1st ed.

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War II by Francis E. McMurtrie (Editor)(1944). Crescent Books

“HMS AUDACITY”. Fleet Air Arm Archive. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

Mitchell, W. H.; Sawyer, L. A. (1990). The Empire Ships. Lloyd’s of London Press.

Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

Don Kindell, Casualty Lists of the Royal Navy and Dominion Navies, ww2 15th – 31st DECEMBER 1941

“No. 35481”. The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 March 1942. p. 1106.

Videos

HMS Audacity Escort Aircraft Carrier, Battle Of The Atlantic part 3

Birth of the CVE Tom Gaskill

Captain eric winkle brown talks about hms audacity

Model Kits

None found so far but a 3D print model.

Martlet I, HMS Audacity

1/700 3D Model on shapeways

1/700 scratch by Bob P. Lord

HMS Audacity in service

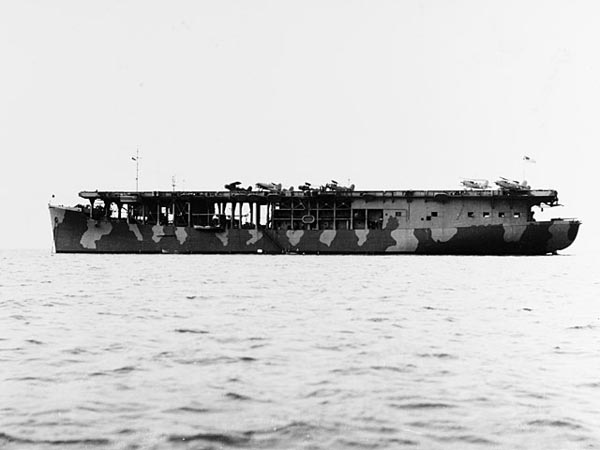

Audacity at sea, IWM

Four Convoy escort missions

Before conversion, Sinbad, now renamed HMS Empire Audacity, was part of the Empire ships, transport ministry’s “Ocean Boarding Vessel” from 11 November 1940, home port London. The Cunard White Star Line Ltd. was given its exploitation. So what happened between November 1940 and 22 January 1941 when she was requisitioned for conversion ? It seems she was still inactive, perhaps because no proper crew was gathered. I cannot find any record of her exploitation on Cunard’s book so it’s likely she never made a single commercial trip.

On 22 January 1941 conversion started at Blyth Dry Docks & Shipbuilding Co Ltd, Blyth and she was commissioned on 17 June 1941 as the Royal Navy’s first escort carrier. The conversion lasted for more than five months, but was a “first” for the RN, and many conversion trips were learned along the way.

Audacity’s Martlets on the rear deck, Ytube video extract

Operational Details are from From Barrett Tillman’s book “On Wave and Wing: The 100 Year Quest to Perfect the Aircraft Carrier”. In adition to her halp-hazard conversion, crews onboard were not happy, in particular superstitious “old salts”, which which it’s bad luck to rename a ship. In that case, four times. In the days following her commission, she did her sea trials, with nothing reported of curial importance.

She started basic in June after Contractors trials, before before commissioned on the 20th and approved for service at the Western Approaches for convoy defence. By July she had her full trials Acceptance and first of Class trials in Clyde area. On the 10th she carried Carried out first deck landing by MARTLET Mk.I aircraft of 802 Squadron. On the 31st she was officially Renamed HMS AUDACITY. And furher trials including flying operations in continuation. She at last embarked MARTLET aircraft and personnel of 804 Squadron, including, seemingly mechanics and mantenance crew in addition to the pilots.

There are doubts of it was eight or six Grumman Martlets (F4F Wildcat) when ready for her first convoy escort, preparing in September 1941.

No.802 Squadron FAA trained extensively to perform CAP (combat air patrol), ready to intercept any spot detected by radar or by themselves. Indeed, fighters were preferred to anti-submarine patrol aircraft (like the Swordfish) as the only perceived threat towards Gribraltar were German long-range Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor.

OG 74: Audacity’s fighters were supposed to OG 74 en route to Gibraltar and were deployed aslmost daily for the trip. Fortunately for the lack of maintenance, the fighers proved quite rugged in appealing conditions. Nevertheless, despite almost daily sorties, there were losses: On 21 September the convoy was attacked by lone a German Condor bomber, which managed to badly damage SS Walmer Castle (later scuttled), before it was intercepted and shoot down by a Martlet. This was the first loss in the convoy, but also the first kill. The bomber of course reported the position to Raeder’s HQ which pressed its available assets. As a result, four ships were claimed by U-boats along the way, which were still by far the greatest peril. Fortunately, on the return trip, HG 74 from Gibraltar (departing on 2 October, to the Clyde on 17 October) was uneventful.

OG 76:

By late October, after a short rest for the crew, the carrier was prepared for her next mission, with OG 76. Again it was to Gibraltar. This time, with the edge of experience, the British pilots managed to intercept and shoot down four Condors, which remains a record for a single convoy. However, one Martlet was crippled by the defensive fire of one of these FW.200 and crashed at sea. Nevertheless, Sub-Lieutenant Eric “Winkle” Brown became the champion Condor killer with two victories during the escort. From there, the Luftwaffe reported the losses and the ship responsible, HMS Audacity, to Admiral Raeder. Therefore, the little carrier was marked for priority destruction by the U-boat command.

HG 76:

The return trip left Gibraltar on December 14, 1941, and this time, HMS Audacity had just four Grummans aboard (possibly one landed for extensive maintenance, and one previously was lost missing, still its replacement). She departed, escorted by three destroyers as the Admiralty was now aware that the Kriegsmarine’s Lorient HQ would probably make her a prime target. Somewhat unsurprisingly, the convoy was soon attacked along the way by a full U-boat wolfpack. Meanwhile, two FW 200 which came to attack the convoy were shot down. A Martlet also spotted on 17 December a lone U-Boat, U-131, and attacked it, but the latter’s AA was sufficient to cripple the fighter, forced it to crash. The U-Boat was also damaged and had casualties. Eventually, she proved unable to dive and was scuttled, becoming the first U-Boat “kill” by a fighter in the Royal Navy.

A FW 200 condor, the ideal long range patrol bomber of the Luftwaffe over the Atlantic and North sea. (wiki cc)

The convoy came under heavy attack by 12 U-boats during the night of December 20-21. Ten U-boats stalked the convoy and four made it inside, attacking, at full speed with their MAN engines. Soon one of the merchantmen fired a “snowflake” flare which silhouetted them. But this also revealed more clearly the silhouette of HMS Audacity, at this point on the recognition books of all German captains, operating not inside, but well off the Convoy. Therefore, U-751 (Kapitänleutnant Gerhard Bigalk) was in a favourable position and prepared to fire his torpedoes. By night, the three remaining Martlets were inoperative, and the pilots on deck could only watch the deadly game of chess taking place. The convoy would lose that night two merchantmen and an escort.

HMS Stanley escorting the convoy

Later that night, U-751, a Type VIIC/41, managed to hit the Audacity in the engine room. Not being protected like a warship, the whole engine room, VTE, and boilers quickly flooded. Not only did Audacity crawl to a stop, but she also started to settle by the stern. Bigalk took his time to approach and fire off his stern tubes. The next two torpedoes hit the aviation fuel close to the bow, which blew it off. Now taking massive flooding from both sides, she settled and sank rapidly about 500 mi (430 nmi; 800 km) west of Cape Finisterre, in 70 minutes.

This time allowed still some of her crew to evacuate, but she carried 73 of her men with her to the bottom of the Atlantic. Survivors were later picked up by the corvettes HMS Convolvulus, Marigold and Pentstemon and dispatched out of the Convoy. One of these was the pilot Eric Brown. At first, an enthralled Bigalk claimed to the HQ having sunk an 23,000 long tons (23,000 t) Illustrious-class aircraft carrier and it was promptly announced by Nazi propaganda, though this was later debunked by the RN. After her loss, operating outside the convoy was later prohibited by the Admiralty. Audacity was avenged later as U-751 was destroyed by RAF Bombers later in the war.

Very dark night, overcast. moderate swell. Spread of four, enemy speed 10 knots, inclination 80°, bows left, depth 3 m, range 1,200 m. After running time of 3 min. 20 sec. we see a detonation against the stern of the enemy— this also turned out to be clearly audible in the forward compartment.

Enemy alters course away from us to port. The light produced by some extremely bright starshell reveals her beyond all doubt to be an aircraft carrier. Now I understand why I got her range and speed so wrong.

Nice artwork of Michael Turner for Winkle Brown’s book sinking of the escort carrier HMS Audacity. srcI withdraw somewhat to reload torpedoes, keeping a close watch on the carrier. After her course alteration to port (south) the carrier slows to a halt. The first torpedo hit must have shattered her rudder and propellers because carrier seems powerless to manoeuvre [sic] herself out of an unfavorable position beam to wind. [Actually her engine room was flooding.] With just a single torpedo—all that remains loaded in my stern tube—there’s little chance of my sinking her. I’ll have to wait until at least two bow tubes have been reloaded.

The shadow is so monstrously large that its breadth covers at least two periscope glass widths. Line of bearing 0°, range 800 m, enemy speed=0. Running time 50 sec, depth 4.5 m. Twin salvo from Tubes I and III. Tube I hits 25 m from the stern. Tube III 10 m forward of midships. Shortly after these hit there is a third powerful detonation accompanied by flames and a substantial quantity of smoke. Carrier is firing red distress signals. Two destroyers approach at high speed. As one of them heads straight towards me I am forced to withdraw.

(Kapitänleutnant Gerhard Bigalk log book, 21 December 1941).

Final assessment

The HMS Audacity was in the end, an objectively bad carrier, and proved to be even more compromised than USS Langley. Her main problem was her half-squadron only comprising of fighters and with just two reserves parked on deck, at the mercy of the weather. The air group was completely ineffective without mechanics and parts, or even a place to be serviced daily. Without proper maintenance, whatever air group squeezed onto her deck, without a hangar to properly protect it, it was likely that it would be able to perform just a few missions during the first leg of any convoy and not on the return trip, suffering a high attrition rate. Not being as extreme as a Merchant Aircraft Carrier, which only carried three planes, and assumed perfectly their hybrid merchant role, not having a hangar or lift, they worked as they were.

However, HMS Audacity was just converted too quickly and was too compromised to reach the same level of operation as later escort carriers, notably those of the Bogue class and their derivatives built in the US but operated by the RN. If she would have survived her last convoy, she would likely have been sidelined for training, anchored in home waters while her precious crew would have been sent on a recent escort carrier.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign