Aircraft Carrier Support Ship

Royal Navy – 1939-59

Royal Navy – 1939-59

WW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classDon’t call me an aircraft carrier: HMS Unicorn was an oddity as aircraft carrier in WW2, as she was envisioned in the 1920s already and with the Second London Naval Treaty, the british delegation secured a condition for auxiliary vessels at large, that opened the gate for a brand new type of ship that would escape aircraft carrier classifications. When started later, what would became HMS Unicorn entered this artificial category of support ships, and thus auxiliaries, not entering the aicraft carrier tonnage. She was indeed at the core designed as an aircraft repair ship. She also represented well the limitations of British armoured carrier doctrine during the war, providing support in distant waters for them. She was indeed a previous asset to repair and supply aicraft to frontline carriers, which had a short air group compared to US carriers. The concept, thus, remained unique to the Royal Navy. She was really indispensible for for extended operations as a fleet carrier deployed on the other side of the globe would rapidly wear out its air group to combat and attrition, and sail back home. Started in 1939, Unicorn was completed only in March 1943 due to delays and priorites, and immediately went into action at Salerno in September 1943, followed by the Eastern Fleet and ending with the British Pacific Fleet. She she notably took part in Operation Iceberg, the campaign of Okinawa and was still used in the Korean war (duelling with NK batteries) ultimately sold in 1959. #royalnavy #aircraftcarrier #hmsunicorn #britishpacificfleet

Genesis and Design of the repair carrier (1936-39)

HMS Unicorn was designed at first as a repair ship and light aircraft carrier, a role split between peacetime and wartime duties. In fact her design went back to the design of the Illustrious class, first British armoured carriers. The latter had a fairly limited air group due to their small hangars and space lacked for effective repair. As said by Brown, D. K. Nelson in Vanguard:

“Repair and even the major maintenance work could not be carried out in the hangars of an operational carrier without interfering with flying and hence it was decided to build a maintenance ship.”

The reduced operational endurance of the armoured carriers was both the result of treaty limitations and smaller air group, but the British Empire network of naval bases was thought to provide both facilities and support. However the Abyssinian crisis of 1935-36 which inspired their design shown also what was needed for sustained operations and it exemplified that these carriers in case of quick deployment between theaters would be soon left their land-based support behind, with the added risk of land facilities falling into enemy hands, as shown by the rapid Japanese advances later in the Pacific.

This a committee was setup in 1936 to evaluate this issue and look at possible fleet support facilities. The need of repair, maintenance and depot ships to be moored in anchorages near the action and not part in the fleet, itself at danger on the first line. The FAA during the Abyssinian crisis showed also her forward deployment followed amonth of intensive flying result in an attrition rate up to 20%, and so that replacement would be needed to compensate close to the action. Not only 20% would be missing but with the ongoing avation, an average of 10% would be in need of repair and maintenance all the time. This combine would result in an effective air group reduced by 30%, on an already limited base.

In 1937 the need for a mobile aircraft depot ship or maintenance carrier was identified whereas the new projected armoured carriers were still in design phase. But this new carrier needed much time and debates to end with a suitable ship. The committee would only snd its report in 1939. It was soon identified this new depot carrier was expected to carry 33 aircraft, made readily available for support and resupply. In 1938 as the design was precised, the design team ended with a calculated displacement of 14,750 ton (20,300 full load) and a speed of 24kts, clearly not sufficient for fleet operations, but they were supposed to operate from afar anyway. It would also need to ensire its own defence.

The tactical plan was any of these new support carriers was to support three fleet carriers, and the planned six not even included the Ark Royal, Courageous and Glorious, made for three ships of the same class being built.

Its Controller Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson, already behind the armoured carrier design which still wanted the new carrier to retain all the features of an operational aircraft carrier, as a “spare” spare deck and act in crisis as a supplementary light aircraft carrier. in times of crisis would be invaluable. The future HMS Unicorn was to be given arresting wires, catapult and well protected munitions stores as well as a fully fonctional armoured flight deck and lifts for standard operations. Engineers however had to tone down some protection aspects, but she was still an armoured carriers by international standards, albeit lightly (see later). The design was approved in mid-1939 (date in research).

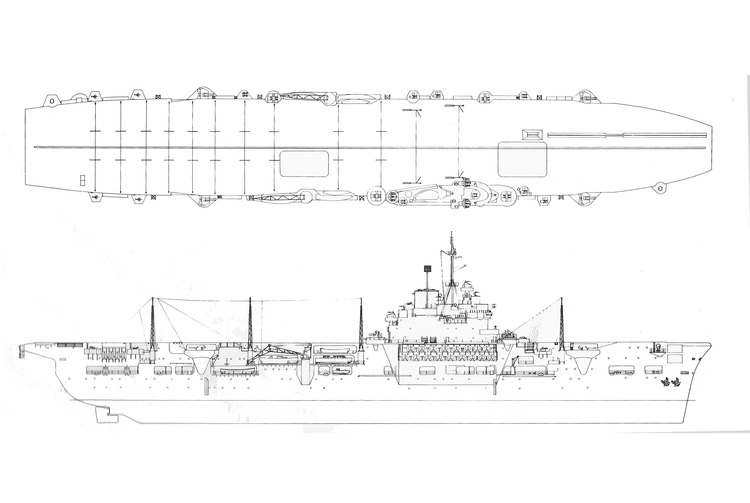

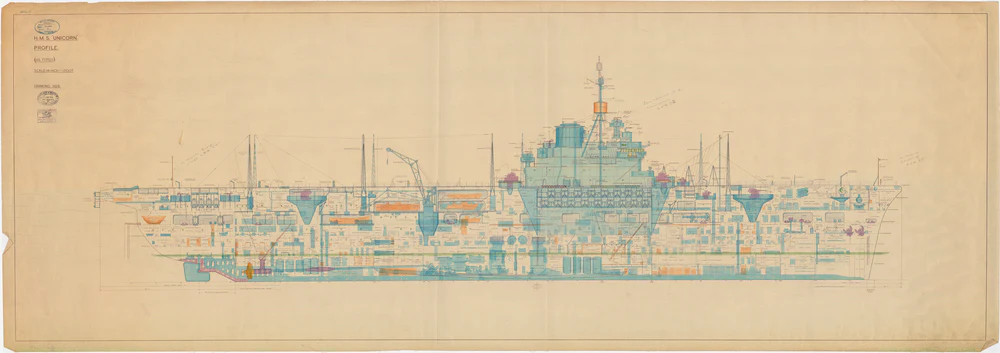

Hull and general design

For most authors and even commentators of the time in 1943, she looked like a “small ark royal”, more stubby-looking, sharing many caracteristics like the twin hangar, one usable for repair and the other for a protected park. The bow lines were modelled after Ark Royal in 1939, the most recent carrier in completion by then, and the flight deck had its edges sloping inwards a little over the prominently plated prow. Her flight deck was also “clean”. However as an auxiliary no much care was given to her aerodynamics, notably the airflow from the bow and around the island. As expecience showed, they would have an inpact on landing approach. Pilots would experience a “sudden drop” with harder landings than on other carriers. This was even aggravated by her shorter deck.

As for her hull, HMS Unicorn measured 640 ft (195.1 m) long overall at the flight deck level, 90 ft 3 in (27.51 m) wide also at flight deck level and 23 ft (7.0 m) deeply loaded. Fpor a displacement of 16,510 long tons (16,770 t) standard and 20,300 long tons (20,600 t) deeply load. This was far more than her intended 14,750 long tons (14,990 t), but additional equipments more in line to fleet carriers operations were added once the treaties were torn down during completion.

Construction

HMS Unicorn was eventually laid down at Harland & Wolff on 26 June 1939, launched in 20 November 1941 and completed on 12 March 1943 at a cost of £2,531,000. By that time not only her design was already obsolete, but her intended role became a straight use as a front line carrier. At the origin this was a project of the Admiralty motivated by reports from the Abyssinia Crisis of 1934–35 which showed an airplane specialized depot ship could be quite useful in operations. Design-wise, she was the pet project of Admiral Reginald Henderson, Controller of the Navy.

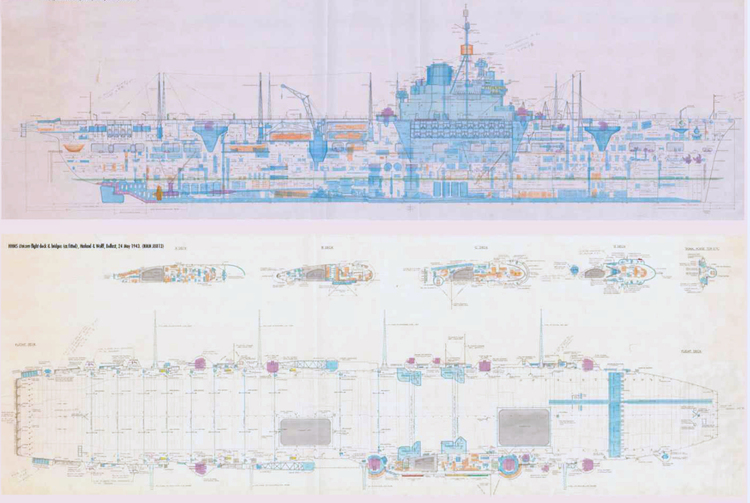

She was defined by him as to “carry out the full range of aircraft maintenance and repair work in addition to the ability to operate aircraft from the flight deck”. Later the concept was seen sound enough to convert two other fleet carriers into the same lines, the HMS persus and Pioneer. She was however somewhat overweight as completed, and stabilization was worked out. She was equipped with a 600 ft/180 m long flight deck with arresting gear a 14,000 ib (6,400 kg) strong catapult. She had two lifts and two hangars like the Ark Royal, of unequal length: Each was 16′ 6” (5.03 m) tall, and the upper one was 324 x 65ft (98 x 19.5m), the lower one 360 x 62ft (190 x 19m). Her petrol capacity was a generous 36,500 imperial gallons and she was equipped with a self-propelled lighter under the rear of the flight deck to recover and transfer disabled aircraft.” (old archive)

Armour protection layout

HMS Unicorn was indeed armoured, but at a level ideal for a ship not intended to be frontline. It was closer to HMS Atk Royal levels of protection, meaning relatively light: She had a 2 in (51 mm) armored flight deck, offering little protection against armor-piercing bombs, but her magazines were boxed and well deep inside the hull, protected by 2–3 in (51–76 mm) or armour. For ASW protection her longitudinal Bulkheads and thise protecting the hangar reached 1.5 in (38 mm). To compare, an Illustrious-class was protected overall by 4.5 in (114 mm). So she better earned the title of “protected carrier”, not better than an Essex-class. Additionally, her hangars could be divided into sections with fireproof curtains and there were fire stations and sprinkers.

Powerplant

Her powerplant was in now way innovative, but compact, with two shafts 15-foot (4.6 m) propellers connected to two Parsons Geares steam turbines, fed in turn by four Admiralty 3-drum boilers working at a pressure of 400 psi (2,758 kPa; 28 kgf/cm2). This enabled a total output of 40,000 shp (30,000 kW), and in turn she as capable of a top speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph), not ideal for fleet operation, but well enough to outpace any submarine and for convoy operation (depots ships of the supply train). The weight/power ratio on this output made her relatively slow but the critical factor was range, with a 7,000 nautical mile radius at an honorable 13.5 kts based on a supply of 3,000 long tons (3,000 t) of fuel oil.

Armament

Main:

Her main armament replaced the cumbersome 4-in twin turrets of her larger fleet sisters for four twin mounts 45-calibre QF 4 in Mk XVI (102 mm) dual purpose guns, much more compact and simply shielded in positions sponsoned along the hull fore and aft, two on each broadside. They sat too low to ensire cross fire above the flight deck however.

AA:

-HMS Unicorn was designed to be fitted with four quadruple 40 mm (1.6 in) QF 2-pounder Mk VIII gun “pom-pom” AA guns. They were located fore and aft at the foot of the port island, and two more in sponsons starboard.

-She also carried four 20 mm Oerlikon guns. They were located mostly on outer small individual sponsons along both sides. This was augmented in 1944-45, although detail is not known.

Sensors

The DP and AA mounts served by two HACS (High Angle Control System) directors coupled with a Type 285 gunnery radar. HMS Unicorn was the first RN ship fitted with the Type 281B early-warning radar.

Facilities

Arresting cables

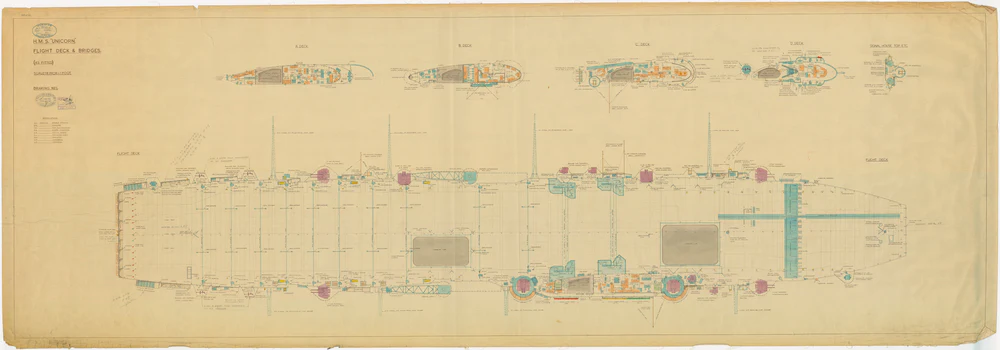

HMS Unicorn looked “stubby” due to her two 16ft 6in hangars sandwiched like HMS Ark Royal on a shortened 640ft length. In total she only had a 600-foot (180 m) long flight deck, 90ft wide flight deck, with arresting gears, ten cables aft of the second lift, and others between this and the fore lift (They could trap 20,000 lbs at 60 knots), plus two stopping nets (crash barriers) short of the catapult, with the same stopping power, but with a much shorter “pull-out”.

Catapult

The latter catapult was located port of the centerline, and was capable of launching a 14,000-pound (6,400 kg) aircraft to 66 knots (122 km/h; 76 mph) with the tail-down launch method. This was called officially a BHIII hydraulic accelerator, same as fitted to armoured carriers.

Hangars

The two hangars making her looks like a “Midget Ark Royal”, measured each 16 feet 6 inches (5.03 m) high. But they diverged in overall surface: The upper hangar reached 324ft by 65ft, the lower one 360ft by 62ft. Total surface was 40,000sq ft, almost the same amount as HMS Idomitable. There was openings to the hangars from the stern enabling her also service floatplanes. Total capacity exceeded her nominal air group: The Hangar space was sufficient to contain 48 aircraft, wings folded, with eight more, wings spread in maintenance. So a grand total of 66, not bad for a ship less than 195 m (640 ft) long, cruiser size. The idea behind the two hangar system was that reserve aircraft were to be stowed into the lower hangar, the upper one used for urgent maintenance and repair.

Lifts

Aircraft were carried between them and the flight deck by two aircraft lifts or elevators located on the starboard side, of different size for different aircraft. They were not far from the island, leaving most of the port side of the deck unincumbered. The forward lift measured 33 by 45 feet (10.1 m × 13.7 m) for potential not-folding models, and the rear lift 24 by 46 feet (7.3 m × 14.0 m) only, better fit for planes having folded wings. Both were designed to lift loads of up to 20,000 lbs with a cycle time of 46 seconds. For her 36 operational aircraft she carried aviation gasoline up to 36,500 imperial gallons (166,000 l; 43,800 US gal) in buried-deep fuel tanks, unprotected. During wartime, between her regular operation crew as a ship, her full air group’s pilots, and all the technical team to repair and maintain a far larger air park, amounted to 1,200 personal in wartime.

Other facilities

She carried about six service boats in recesses into the hull, under davits, but also a self-propelled lighter stowed under the rear of the flight deck, which allowed allow unflyable aircraft to be transferred between ships or to shore facilities, and htne lifted aboard using cranes. This lighter was placed levelled at the upper hangar deck to allow aircraft to be quickly rolled onto it, on one lifted up from the water into it. Thus system was unique to this aircraft carrier and proper to her role.

With hangars intended wide and high enough to include all FAA present and future aiecraft, wings spread or folded, she could maintain any air group models, including US ones.

Both hangar decks were fitted with a network of rails and hoists to allow heavy payloads such as aircraft engines to be moved around and hauled out between aircraft or transferred in and out of the dedicated workshop, which included a very large set of spare parts, tooling, and even a working bench for engine trials.

The large engine repair shop with its test compartment were located near the bow, under the flight deck. It comprised also two large, rectangular openings for engines to be run at full power with the external airflow venting fumes out. More specialized workshops were built-in, to service the airframe, or radio equipmant as well as the electrical networtk, even woodworking or fabric repairs, against with spares and tooling machinery. At design phase already it was planed six days for an average repair with 3×6 personal work teams in rotating shifts.

Artificers and mechanics were mustered into two Special Repair Parties with full British and USN standard toolkits.

In 1944 her hangars and workshops were modified, reorganized to accept US-built aircraft, with even specialised workshops for US engines and stores for Grumman, Vought and Curtiss parts.

So that as part of the BPF she was fully capable of servicing/maintaining not only FAA Seafires, Fireflies and Barracudas but also Corsairs, Hellcats and Avengers, including those of the USN if needed. After all, she was very unique among the allies in the Pacific. The US Navy had no such ship. Due to her deck she could receive and sent back aircraft in a shorter span than regular maintenance/repair including depot with a lighter, transfer to shore facility or repair ship and return via the same mode.

A problematic island

Her only backdrop as a regular carrier for standard flying operation was her tall and bulky ship’s bridge, the highest in the RN as it sat 95ft above the wavetops. Wind flow was disturbed quite a lot and pilots were not at ease when landing on her. This island was modelled both after the on Ark Royal but also the Illustrious class. It was crowned by a main fire control top, and a tripod mast supporting radar aft of it. So she at least fill her role, with two bridges, one for carrier operation and another for ship’s manoeuvers.

Air Group

Supermarine Seafire Mk.IIb aboard HMS Unicorn, Salerno Landings 1944

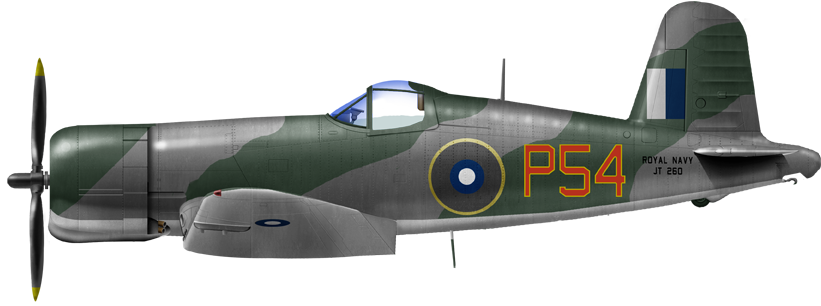

Corsair Mark II aboard Unicorn, 757 Naval Air Squadron FAA, BPF July 1944

HMS Unicorn could carry and operate 33-35 aircraft all contained by the hangars in maximal capacity. However as practice changed, especially in the Pacific with the BPF, following USN standard, she was setup to have a permament deck park and had in the end twice (66-70) aircraft crowded on her flight deck crowded as a “taxi”. This air group varied in time, but it seems the kept a permament park of Seafires and Swordfishes throughout 1943-44. In a strict ferrying capacity, an average of 50 to 80 aircraft depending on the type were carried.

But when operational as fleet carrier like at Salerno and Norway, she could support 35 aicraft, comprising notably 20 non-folding Seafire IICs. But she was proven capable to ferry also 69 folding-wings Seafire IIIs. This became even her most common payload as the Seafire, a dream to fly and formidable fighter, was never intended for carrier use originally and was prone to break its landing gear or damage her structure at each landing. Wilcats and Corsairs were infinitely more robust. So she was a frequent “guest” aboard Unicorn in 1944-45. Given her capacity she was paradoxically not able to repair that much aicraft: She could have about 24 aircraft under repair at any one time, supposedly wings spread.

According to various lists, this included the Fairey Fulmar, Seafire, Martlet (Wildcat), Corsair, Swordfish, Albacore, Barracuda, Walrus (seaplane) and Tarpon (Avenger). However these were mostly repaired models, and the “home list”, those for sure par tof her permament park could be listed below:

-In May 1943 as completed: 18 Swordfish, rest unknown

-July 1943: 10 Seafire, 13 Swordfish

-September 1943: 17 Wildcat, 38 Seafire and 3 Swordfish

-1944: Photo shows seafires and Barracudas, Walrus…

-1945: Likely resident Corsairs, Wildcats and Seafires

General Assessment

The funny part of the ship when approved before the war was taht on plans she (HMS Unicorn) was in many respects indistinguishable from an active fleet carrier and already back then US filled its authorized tonnage, and when completed in 1943, it was seen as supplementary to prewar approved combat-capable carriers.

So some in the admiralty worked out between treaty lines and the Naval Law Department to recommend HMS Unicorn to be classified as an auxiliary, according to her primary role to support carriers liked armed tenders for submarine or destroyer flotillas. Her aircraft carrier appearance was “sold” as a necessary adaptation to her trade, and even looked at destroyer tenders had the time which indeed looked large very large, stretched destroyer in silhouette. But in the end only one was ordered by fear for suspicion in 1939, not the three planned for all active carriers. Emergency war program in any case had it all reset anyway and auxiliaries were out of the question now.

Shifts in priorities during construction would not only affect Unicorn but also Implacable and Indefatigable, completed way after the Illustrious class, despite started and planned as part of the same bunch.

In service HMS Unicorn was recoignised as indeed slow, but this in not way plagued her utility. She was found quite adequate for regular carrier operation in settled fronts like landing areas, starting with Salerno. Sehe only started to play her intended role in the Pacific and played it wall. In fact her general flexibility made her in a sense, the precursor to modern SVTOL/Helicopter assault ships. Indeed, one often overlooked aspect was her floating hospital facilitiesn reminiscent of these modern assault ships. There was a large sick bay and fully equipped surgery and even dental rooms, twin medical stations for grave, urgent injuries in addition to the hospital facility. In short she could “treat” far more than her crew, but other fleet carriers injured men as well, possibly flew from modified flying ambulances, but it’s a topic worth researching.

Old author’s illustration

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 13,310 t. standard – 24,000 t. Fully loaded |

| Dimensions | 640 ft x 90 ft 3 in x 23 ft (195 x 27,5 x 7m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shaft Parsons geared turbines, 4 Admiralty WT boilers, 40,000 sh |

| Speed | Top speed 24 knots |

| Range | Oil: 3,157 t- 7,000 nm/18 knots or 11,000 nm/13.5 kts |

| Armament | 4×2 4 in MK IVI, 4×4 40 mm Bofors AA, 12x20mm Oerlikon AA, 33 planes |

| Protection | Flight Deck 51mm, Bulkheads 36-38mm, Boxed Magazines 51-76mm |

| Crew | 1200 with air crew |

Read More

Books

Accinelli, Robert (23 January 1996). Crisis and Commitment: United States Policy toward Taiwan, 1950-1955.

Brown, D. K. (1984). “HMS Unicorn: The Development of a Design 1937–39”. Warship VIII. Conway

Blackman, Raymond V. B. (ed.). Jane’s Fighting Ships 1953–54. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Brown, J. D. (2009). Carrier Operations in World War II. NIP

Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946.

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. NIP

Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). Chatham Publishing.

Ford, Roger; Gibbons, Tony; Hewson, Rob; Jackson, Bob; Ross, David (2001). The Encyclopedia of Ships. Amber Books.

Friedman, Norman (1988). British Carrier Aviation: The Evolution of the Ships and Their Aircraft. NIP

Garver, John W. (30 April 1997). The Sino-American Alliance, Nationalist China and American Cold war Strategy in Asia.

Hobbs, David (2007). Moving Bases: Royal Navy Maintenance Carriers and MONABs. Maritime Books.

Hobbs, David (2011). The British Pacific Fleet: The Royal Navy’s Most Powerful Strike Force. NIP

Howse, Derek (1993). Radar at Sea: The Royal Navy in World War 2. NIP

Lenton, H. T. (1998). British & Commonwealth Warships of the Second World War. NIP

McCluskie, Tom (2013). The Rise and Fall of Harland and Wolff. Stroud: The History Press.

Sturtivant, Ray (1984). The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm. Tonbridge, UK: Air-Britain (Historians).

Links

On armouredcarriers.com

On navypedia.org/

wikipedia.org

telegraph.co.uk/news On /Captain-George-Baldwin

http://fleetairarmarchive.net/Ships/Unicorn.html

https://archive.ph/20120720192453/http://www.btinternet.com/~faahistoryweb/index.htm

On maritimequest.com/

On britains-smallwars.com/

CC photos

Model Kits

The only one known: HP-Models No. WWII-WL-GB-172 1:700, a rather old kit. Photos. It seems also that White Ensign models made it too, no longer, neither in stock.

3D

HMS Unicorn in service

HMS Unicorn was completed after many delays on 12 March 1943, and to accelerate the process, the Admiralty decided in 1942 that she would not be equipped with her full maintenance and repair equipment suite. Total cost without armaments, sensors and air group amounted to £2,531,000. She started working up after sea trials, and saw 818 and 824 Squadrons arriving, landing aboard in April 1943. 818 Squadron comprised nine Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers while 824 Squadron comprised six of them.

European waters: Norway, Mediterranean

Underway in the Atlantic, 1943

OPERATION GOVERNOR

887 Squadron arrived just afterwards, with nine of the brand new Supermarine Seafire IIC fighter. They all made their carrier qualification in home waters. By late May 1943, HMS Unicorn departed for her first escort mission, with Convoy MKF 15 to Gibraltar taxiing Royal Air Force Bristol Beaufighters. She escorted the returning convoy to the Clyde estuary by early June. With HMS Illustrious, she was sent to operate along the Norwegian coast (Operation Governor) which was a diversion for the Allied landings in Sicily, by early July. She carried 887 Squadron instead of 800 Squadron, equipped with Hawker Sea Hurricanes, hoping to inflict a lot of damage on the Luftwaffe based in Norway.

Atlantic 1943, underway – IWM

OPERATION AVALANCHE

HMS Unicorn newt was reassigned to Force V comprising several British carriers under overall command of Admiral Philip Vian. This was the air cover of Operation Avalanche, the Allied landings at Salerno, and first big operation of HMS Unicorn as a fleet carrier. In preparation she had her two Swordfish squadrons landed only keeping a small detachment of three 818 models for abtntiship self-defence, the rest being composed of the Sea Hurricanes of 800 Squadron, soon replaced by Seafires of 809 and 897 Squadrons (10 aircraft each) making for a total of 33 planes overall. HMS Unicorn joined Force V in August 1943 at Gibraltar and sailed for the Central Mediterranean for intensive training before the operation commebced on 9 September.

Her Seafires flew 75 sorties the first day, 60 on 10 September, but attrition in carrier landings in low wind conditions made her suffer even worse than any other fleet carrier due to the disturbances caused by her large island. She had the highest ratio of landing accidents in the fleet. 44 sorties only were flown on 11 September, 18-12 September, mechanics repairing ten Seafires during the night.

Fighter shortage became such an issue than those of Illustrious and Formidable intended to cover and air strike on the incoming Regia Marina poised to to interfere with the invasion, were instead reassigned as air cover over the landings area. On 12 September, 887 Squadron was back at half-strenght, at least providing a CAP of six Seafires, soon moved to a temporary airfield ashore, ensuring better landings.

After the operation was concluded, HMS Unicorn went back home on 20 September with a large load of damaged Seafires, her own and those of the fleet carriers, as intended when she was first designed. These were off-loaded at Glasgow for repairs. HMS Unicorn had her first refit in her original builder Yard, Harland and Wolff of Belfast, and she was reconfigured for her designed role as aircraft repair ship, with her original full repair suite, workshops, parts magazines and all, left over when she was first completed.

So Salerno would be her only true “fleet carrier” operation, but the Seafire proved at this stage not reliable for prolongated use, and the Martlet and Sea Hurricane were now obsolete.

Indian Ocean

HMS Unicorn (camouflaged, in the background) and illustrious at Trincomanlee, Ceylon, 1944. Notice the difference in height of the former

Servicing a Supermarine Walrus used for reconnaissance with her crew, far east 1944

By the end of December 1943, HMS Unicorn joined HMS Illustrious, escorted by the battlecruiser HMS Renown and Queen Elizabeth, Valiant, en route to bolster the Eastern Fleet. She only carried her permament self-defence four Swordfish from 818 Squadron at the time.

Indeed she acted as taxi for the Royal Navy Air Station at Cochin in India. She arrived and flew out her plans there on 27 January 1944. Next, she headed to Trincomalee, Ceylon, arriving on 2 February. She was immediately tasked to repair aicraft and her deck was used for landing practice. She had a brief refit in Bombay in May 1944. On 23 August, 818 Squadron was transferred to Atheling (and disbanded soon after). On 7 November, 817 Squadron flew aboard, counting Fairey Barracudas equipped with ASW warfare. At the time indeed, HMS Unicorn was assigned to the convoy patrol route of the cape, she was to be based in Durban, South Africa. She was modified there with separate workshops and equipment to service American engines, not to the same standard, in order to return to the pacific and be of some use for the now largely provided US fighters, the robusts Hellcats and Corsairs.

When done at the end of August, HMS Unicorn was officially transferred to the newly formed British Pacific Fleet (BPF). She left Durban on 1 January 1945 for Colombo in Ceylon, retruning to her deck-landing practice for BPF pilots, ahd repairing damaged planes during these training sessions. She next loaded 82 aircraft and 120 engines to be landed in Australia, which were all the available stocks of the Eastern Fleet, not rebaptised and relocated to the Pacific. Departing for Sydney on 29 January she arrived on 12 February.

Pacific

With the BPF (she is second from the foreground) at anchor in 1945, Manus Island

HMS Unicorn sailed in 28 February for Manus Island (Admiralty Islands) to provide again BPF training and repair services. The BPF was prepared for Operation Iceberg. Next she was moved to San Pedro Bay, Philippines, arriving on 27 March. She served as intermediate replenishment base, and was prepared to move for Operation Iceberg proper. Recuperating her fleet carrier role, she was assigned the attack of attack Japanese airfields in the Sakishima Islands and Formosa in the early part of the invasion of Okinawa.

Operation Iceberg

HMS Unicorn was moslty use to prepare aircraft for operational squadrons, then flew aboard fleet carriers for first line operation. It was mostly preparation and maintenance but she still performed repairs and modification of 105 aircraft by March–May 1945. She returned to Australia on 22 May to take aboard parts and engines, arriving in Sydney on 1 June. She moved to Brisbane on 6 June and entered the Cairncross Dockyard to have her bottom scrapped in drydock, and afterwards loaded more replacement aircraft.

Back to Manus on 22 July, HMS Unicorn prepared operations off Japan. July-August saw her rarely theatened by Kamikaze as she never was frontline and she soldiered on until the Emperor declared the capitulation on 15 August. Her next task was to ferry aircraft and equipment, but also men to Australia, arriving at Sydney on 6 November. By December she sailed for home. She arrived in Plymouth by January 1946 to decommissioned, placed in reserve. This made for a fairly short service by then of just three years, so the RN looked at ways to use her in the future.

Post-War Career

In 1949 the far east proved a powdercake and HMS Unicorn was reactivated for service, and support of the carrier HMS Triumph (Colossus class). She sailed from Devonport on 22 September loaded to the brim with spare Seafires and Fireflies.

As the Korean War started by June 1950, she disembarked her air group, equipment and maintenance personnel to RAF Sembawang in Singapore. She was reassigned as a replenishment carrier to the Royal Navy and Commonwealth naval air forces deployed on the theater. HMS Unicorn left Singapore on 11 July for Sasebo in Japan (20 July) sending 7 Seafires and 5 Fireflies to HMS Triumph. By August she carried the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment and 27th Brigade HQ from Hong Kong to Pusan on 29 August. She also unloaded next more supplies in Sasebo and was sent back to Singapore for a refit.

As the Korean War started by June 1950, she disembarked her air group, equipment and maintenance personnel to RAF Sembawang in Singapore. She was reassigned as a replenishment carrier to the Royal Navy and Commonwealth naval air forces deployed on the theater. HMS Unicorn left Singapore on 11 July for Sasebo in Japan (20 July) sending 7 Seafires and 5 Fireflies to HMS Triumph. By August she carried the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment and 27th Brigade HQ from Hong Kong to Pusan on 29 August. She also unloaded next more supplies in Sasebo and was sent back to Singapore for a refit.

Back in December 1950 she carried 400 troops and an air park, supplies and equipment. Like in the old days, mostly green pilots practice deck-landing en route. By March, she ferried Gloster Meteor jets (No. 77 Squadron RAAF) to Iwakuni in Japan. She spent the next three months there as an accommodation ship. In June 1951, she was back as a ferry carrier. However while corssing the Shimonoseki Strait on 2 October her Island cut overhead power cables between Honshu and Kyushu after a heavy snowfall.

On 21 November she exchanged crews with the carrier HMS Warrior at Singapore so to be free for a refit, completed on 20 January 1952. She was back to ferry duties. In July 1952 she was used as a spare flight deck for damaged aircraft from fleet carriers, in order not to disrupt strike operations.

On 27 July she entered Singapore load replacement aircraft. This included more jet-powered Meteors. On 9 August she headed for Japan and by September, the received her first CAP since a very long time: HMS Ocean’s four Hawker Sea Fury fighters for air cover during strike operations. Again, this freed Ocean to concentrate on strikes only.

HMS Unicorn received a drydoch maintenance in October 1952. She embarked the First Sea Lord, Admiral Rhoderick McGrigor and CiC, Far East Station to tour Commonwealth forces based in Japan. At least she saw some action, striking North Korean coastwatchers at Chopekki Point. This was her only wartime active strike.

With the BPF in Sasebo, Japan, 1950

Back to Singapore for a new refit on 15 December 1952, she as inactivated until17 July 1953 and on the 26th while en route for Japan she received an SOS from SS Inchkilda, atacked by pirates south of the Wuqiu region (Taiwan Strait), which proved to be gunboats of the ROC Anti-Communist National Salvation Army (ACNSA). She arrived at high speed and seeing her, pirates abandoned their prize. She went close to the freighter with all guns bearing and fired a warning volley for good effect. The Korean Armistice was learned the following day. Still, she became the sailor of HMS Ocean on two more patrols on 30 July and 25–29 August, monitoring North Korean compliance with the terms. On 15 October she departed for home, ending her last combat deplmoyment. She arrived at Devonport on 17 November.

With sea Fury aboard, Kure 1950 src FLICKR

Unicorn In Singapore, 1953, FLICKR via pinterest

Fom destinationjourneys.com via pintesrest

Hawker Sea fury taking off, 1950s – IWM

Fate

Well before that, in 1951, the admiralty already had some ideas about her possible conversion. In 1951, indeed was planned a modernisation to accept modern and heavier jet aircraft. She was to be fitted with a new steam catapult, reinforced flight deck and lifts, the forward one being enlarged. She was to be also fitted with a new crane and new lighter aft. The Director of Naval Construction (DNC) proposed to combine both hangars into a single one due to the height of the new models, but this proposal was rejected based on budget. HMS Unicorn was to be taken out from the reserve in July 1954 for such conversion, but it was cancelled well before in November 1952. Indeed, some light fleet carriers of the Colossus/Majestic class were converted while under completion as repair ships already. The admiralty also considered having a budget to refit existing carriers with angled flight decksmight have all budgetary priority.

Thus, a new project was born, to convert as a Ferry Carrier in June 1953. This was done quickly but she returned in extended reserve in March 1957, then stricken in 1958 and ultimately sold for scrap in June 1959. She was broken up at Dalmuir, arriving on 15 June and the process ended at Troon in 1960.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign