Российский императорский флот: 90,000 personal, 40 ship of the line, 15 frigates, 24 corvettes and brigs, 16 steam frigates. Created 1696

Российский императорский флот: 90,000 personal, 40 ship of the line, 15 frigates, 24 corvettes and brigs, 16 steam frigates. Created 1696Foreworld:

The Russian Imperial Navy was created a bit later than other great European Navies (Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, British, French…). I existed from 1696 to 1917. See the Russian Navy in WWI for the final part of this chapter.

The Russian Imperial Navy was created a bit later than other great European Navies (Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, British, French…). I existed from 1696 to 1917. See the Russian Navy in WWI for the final part of this chapter.

As Russian main industry was agriculture, they were few facilities skilled enough to deliver reliable steam engines as 1850. So far, the bulk of the fleet was made of many sailing three and two decker, equipped with 130 to 74 guns. The former navy was built carefully during Peter the Great and Catherine of Russia rules.

St Petersburg was a major warship harbour of strategic importance for all Baltic Sea, as well as Sevastopol in Crimea. The majority of the screw vessels were built from 1856 to 1860, after the Crimean war, and the major ships were all based in the Baltic, while frigates and corvettes were based equally in the Mediterranean and in the Far east. The very first Russian ironclad was built in 1865. It was based on a frigate and converted in 1862 at Kronstadt.

As from the Russian perspective, the French and British were Christian nations, and as such the fact they could wage war against Russia to defend the Ottoman Turks was unbelievable. So the Russian navy, in relative understrength compared to the Ottoman navy, but counting half of Paixhans guns, attacked the squadron at Sinope, the Black Sea stronghold, as the first move against the Ottoman Empire.

This was purchased notably to ensure safe passage of troops and materials in the Black Sea. Obvious Russian ambitions in the Mediterranean, were both the French and the British has commercial and strategic interests, as well as the well-known weakness of the Ottoman Empire, came as a threat sufficient to intervene. During the whole Crimean war, no Russian ship was ever committed against the allied armada. They relied on forts.

Aleksander Nevski was the flagship of the Russian navy, an impressive first-rate, three deckers sailing ship of the line, which fought at Sinope. The Russian navy, as for 1853, was no match for the combined allied forces. They retreated and the bulk of the navy was stationed in the Baltic sea, were naval operations, once again, were directed toward an impressive line of naval fortifications.

Early Origins

An introduction: The Russian navy (1680-1917): Before the Soviet Navy, there was the Russian Navy. The latter was of relatively recent composition (from the seventeenth century, Peter the Great). Governing a colossal continental power, the Tsar of all the all Russias had little interest in maritime affairs. But long before this vast country secured outlets on the Black Sea or the Baltic, the Slavs possessed rudiments of long-sea maritime trade, carried out first and foremost by fluvial boats, and then Ships of Scandinavian nature, influenced by the Venetian construction (present-day Poland). In the Middle Ages, the Slavic navigators were equally bold as those of the Vikings on their Lodyas, a Russian replica of the Drakkars, but originally canoe derivatives. Some cities, such as Kiev and Novgorod, had enjoyed a certain radiance thanks to maritime trade on a network of routes from the Scandinavian and Hanseatic cities to Constantinople and Greece.

The semi-legendary figure of Rurik, that funded Kiev. Scandinavian shipbuilding was locally adapted to produce the Lodya.

At that time there was an embryo of a naval force, for vast fleets were thrown against Constantinople by the princes. The Black Sea is certainly the cradle of the Russian fleet, and its academy. A trade also began in the Baltic with the Hanse, but the lack of large coastal ports prevented its development. Moreover, pirates began a real boom in the 15th century, to which the Tsars brought a solution by financing the protection of their ships by the Danes, bought at a gold price thanks to the benefits of this trade. The threat of the Tatars, the Mongols and the Teutonic Knights having passed, a new opponent in the Baltic presented himself: Sweden. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the house of the Romanov succeeded to the house of Rurik. Disturbances marked this interregnum, in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, while Cossack expeditions defended the interests of the Tsar. But these operated more often on land, or in solid galleys, distant derivatives of the Lodyas.

A Kievan Rus Lodya.

The fleet was used during the Caspian campaigns, the Russo-Byzantine wars and the Swedish-Novgorod wars. In 1496, during the Russo-Swedish war, Princes Ivan and Peter Ushaty made a naval campaign on the ships of the Russian Pomors – having passed through the White Sea, they rounded the Kola Peninsula, captured three Swedish ships and invaded the northern part of Finland.

The first three-masted ship built in Russia according to the European standard was launched in Balakhna in 1636 during the reign of Tsar Mikhail Fyodorovich. The ship was built by shipbuilders from Holstein and was named “Frederick”. The ship sailed under the flag of Holstein, on its maiden voyage “Frederick” set off from Nizhny Novgorod down the Volga on July 30 (August 9), 1636, heading to Persia. On October 27 (November 6), 1636, Frederick set out for the Caspian Sea, and on November 12 (November 22), it was caught in a powerful storm that lasted three days. The ship was badly damaged and ran aground to save its cargo and crew. It was later pulled ashore near Derbent and plundered by local residents.

On July 22 (August 1), 1656, the Russian rowing flotilla of Governor Pyotr Potemkin defeated a squadron of Swedish ships near Kotlin Island and captured a 6-gun galley. The Battle of Kotlin Island is considered by historians to be the first documented Russian victory at sea in modern times. Earlier, on June 30 (July 10), 1656, the same flotilla of Governor Potemkin took part in the capture of the Swedish fortress of Nyenskans (Kantsy), located at the mouth of the Okhta River.

During the Russo-Swedish War of 1656-1658, Russian troops captured the Swedish fortresses of Dünamünde and Kokenhusen (renamed Tsarevich-Dmitriev) on the Western Dvina. Boyar Afanasy Ordin-Nashchokin founded a shipyard in Tsarevich-Dmitriev and began building ships for sailing on the Baltic Sea. In 1661, Russia and Sweden signed the Treaty of Cardis, as a result of which Russia returned all conquered territories and was forced to destroy all ships laid down in Tsarevich-Dmitriev.

A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin invited Dutch shipbuilders to help Russian craftsmen in the village of Dedinovo, located on the Oka River, where shipbuilding began in the winter of 1667. Four ships were built within two years: the frigate Orel and three smaller vessels. Orel is considered the first Russian sailing ship; it was in Astrakhan from 1669. According to one version, the ship was burned in 1670 by the rebellious Cossacks of Stepan Razin, according to another, it was captured by Razin’s troops and transferred to the Kutum channel, where it stood for several years and fell into complete disrepair.

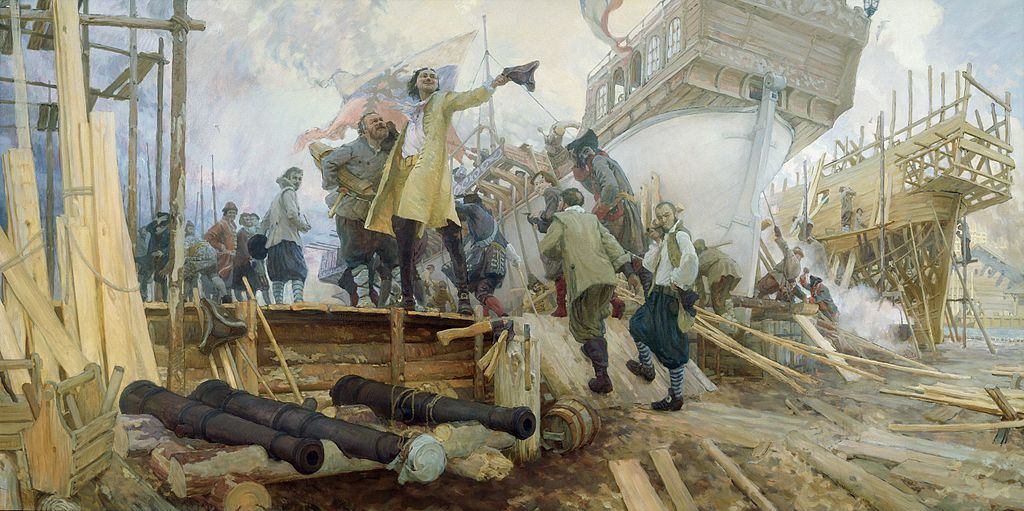

Peter I’s Fleet

Peter the Great in a Dutch Shipyard learning naval construction, a 19th cent. painted allegory, “A New Thing in Russia” by artist Yu. Kushevsky.

In 1693, the Solombala shipyard was founded near Arkhangelsk, where Dutch craftsmen built the yacht “Saint Peter”, and the following year the first merchant ship, “Saint Apostle Paul”, was launched. In 1696, the Preobrazhensky shipyards were formed. On December 21, 1698, the Naval Fleet Order was established, headed by F. A. Golovin; in 1700, it was renamed the Naval Affairs Order, headed by F. M. Apraksin, and in 1708, the Admiralty Order, headed by A. V. Kikin.

During the Second Azov Campaign of 1696 against Turkey, the Russians deployed 2 ships of the line, 4 fire ships, and 23 galleys for the first time. The first ships of the new fleet were built at the shipyards of the Voronezh Admiralty and 1,300 barges were built on the Voronezh River. After the capture of the Azov fortress, the Boyar Duma discussed Peter I’s report on this campaign and decided to begin construction of the navy on October 20 (30), 1696. This date is considered the official birthday of the regular Russian Navy. On December 1 (11), 1699, the banner with the St. Andrew’s Cross was proclaimed by Peter I as the official flag of the Russian military fleet.

The Russian Baltic Fleet was created during the Great Northern War of 1700-1721. Construction of the galley fleet began in 1702-1704 at several shipyards located on the estuaries of the Syas, Luga, and Olonka rivers, as well as on the Svir River (now the city of Lodeynoye Pole). To protect the conquered coasts and to attack enemy sea routes in the Baltic Sea, a sailing fleet was created from ships built in Russia and purchased in other countries. In 1704, the Admiralty shipyards were laid down in St. Petersburg. In 1703, the first sea vessel for the Baltic Fleet, the Shtandart, was built. In 1703-1723, the main port of the Baltic Fleet was in St. Petersburg, and after that – in Kronstadt, new military ports were created in Vyborg and Revel.

In 1725, the Russian fleet had 130 sailing ships, including 36 ships of the line, 9 frigates, 3 shnyavas, 5 fire ships and 77 auxiliary vessels. The rowing fleet consisted of 396 ships, including 253 galleys and scampaveas, as well as 143 brigantines. The ships were built at 24 shipyards, including shipyards in Voronezh, Kazan, Pereslavl, Arkhangelsk, Olonets, St. Petersburg and Astrakhan. Naval officers were from the nobility, sailors – recruits from the common people. The term of service in the navy in those days was lifelong. Young officers studied at the School of Mathematical and Navigational Sciences, founded in 1701 in Moscow, and were often sent abroad for training and practice. Foreigners were also recruited for naval service, for example, the Scotsman Thomas Gordon, commander of the Kronstadt port.

In 1715, the first Academy of the Naval Guard was founded in St. Petersburg, in 1718 the Admiralty College was formed – the highest governing body of the Russian fleet, the Kazan Admiralty was formed. In 1722, the Astrakhan Admiralty was created, and in 1724, Efim Nikonov tested the first underwater vehicle made of wood.

The principles of organizing the navy, the methods of education and practice for training future personnel, as well as the methods of conducting military operations were recorded in the Naval Regulations of 1720 – a document based on the experience of foreign countries. Peter the Great, Fyodor Apraksin, Alexey Senyavin, Naum Senyavin, Mikhail Golitsyn and others are considered the founders of the art of naval combat in Russia. The principles of naval warfare were further developed by Grigory Spiridov, Fyodor Ushakov and Dmitry Senyavin.

The fleet created by Emperor Peter I reached the zenith of its power by the 1720s. During this period, a new fleet staff was introduced, which resulted in the construction of 54-gun ships and the laying of the first 100-gun ship “Peter the First and Second” in 1723. However, from 1722 the rate of shipbuilding declined sharply. In the last years of Peter’s reign no more than 1-2 ships were laid down per year.

1722: 1

1723: 1

1724: 2

1725: 1

The number necessary to maintain the regular staff was 3 ships per year.

In 1725-1726 the first long-distance Russian ocean expedition to Spain took place. The Baltic fleet had 25 ships in 1725, versus 48 for Sweden and 42 for Denmark and Turkey.

The state of the fleet after the death of Peter I

Left: President of the Admiralty College in 1728-1732 Dutch-born Admiral Pyotr Ivanovich Sievers. After the death of Peter I, the situation in shipbuilding deteriorated sharply. In 1726, only one 54-gun ship was laid down, and in the period from 1727 to 1730, not a single ship was laid down.

Left: President of the Admiralty College in 1728-1732 Dutch-born Admiral Pyotr Ivanovich Sievers. After the death of Peter I, the situation in shipbuilding deteriorated sharply. In 1726, only one 54-gun ship was laid down, and in the period from 1727 to 1730, not a single ship was laid down.

In 1727, the navy consisted of 15 combat-ready ships of the line and 4 combat-ready frigates.

In 1728, the Swedish envoy to Russia reported to his government:

“Despite the annual construction of galleys, the Russian galley fleet, compared to the previous one, is greatly diminished; the naval fleet is falling into complete ruin, because the old ships are all rotten, so that more than four or five ships of the line cannot be put to sea, and the construction of new ones has weakened. There is such negligence in the admiralties that the fleet cannot be restored to its previous state even in three years, but no one thinks about this.” At the end of 1731, the naval fleet included 36 ships of the line, 12 frigates and 2 shnyavas, but only about 30% of the regular number of ships of the line were fully combat-ready, another 20% could operate in the Baltic only at the most favorable time of the year, without storms. In total, the Russian fleet could put eight fully combat-ready ships of the line to sea and five – on short voyages in the Baltic. All ships of the large ranks – 90, 80, 70-gun ships – were out of action. Only one 100-gun ship, five 66-gun ships and seven 56-62-gun ships remained combat-ready or partially combat-ready.

The galley fleet, which included 120 galleys, was in relatively satisfactory condition. In 1726, Vice-Admiral Pyotr Sievers proposed introducing a peacetime staff for the galley fleet, which was implemented in 1728. The fleet constantly maintained 90 galleys afloat, and another 30 galleys stored timber for quick assembly.

During the reign of Peter II, the intensity of combat training of the fleet’s crews sharply decreased. In April 1728, at a meeting of the Supreme Privy Council, the Emperor ordered that only four frigates and two flutes of the entire fleet should go to sea, while five more frigates should be ready for cruising. The remaining ships were to remain in ports to “preserve the treasury.” To the arguments of the flagships that it was necessary to constantly keep the fleet at sea, the Emperor replied: “When need requires the use of ships, then I will go to sea; but I do not intend to stroll along it like a grandfather”. The poor state of the treasury and irregular payment of salaries led to an outflow of officers, which caused a decline in discipline among the soldiers and sailors.

During the reign of Anna Ioannovna

Left: Empress Anna Ioannovna bu Louis Caravaque, 1730. Upon her accession to the throne and the abolition of the Supreme Privy Council, Empress Anna Ioannovna addressed the issue of restoring the fleet with her first decrees. On July 21 (August 1), 1730, the Empress issued a personal decree “On the maintenance of the galley and ship fleets according to regulations and statutes”, which “most firmly confirmed to the Admiralty College that the ship and galley fleets were maintained according to statutes, regulations and decrees, without weakening and without relying on the current prosperous peacetime”.

Left: Empress Anna Ioannovna bu Louis Caravaque, 1730. Upon her accession to the throne and the abolition of the Supreme Privy Council, Empress Anna Ioannovna addressed the issue of restoring the fleet with her first decrees. On July 21 (August 1), 1730, the Empress issued a personal decree “On the maintenance of the galley and ship fleets according to regulations and statutes”, which “most firmly confirmed to the Admiralty College that the ship and galley fleets were maintained according to statutes, regulations and decrees, without weakening and without relying on the current prosperous peacetime”.

In December 1731, the Empress ordered the resumption of regular exercises at sea in the Baltic Fleet, so that “this could be done both for training the men and for the ships to be properly inspected, since in the harbor it is impossible to inspect the rigging and other damage as well as the ship in motion”. In January (February, N.S.) 1731, the new 66-gun ship of the line Slava Rossii was laid down at the Admiralty shipyards, and two more ships were laid down in February and March 1732.

In 1732, under the chairmanship of Vice-Chancellor Count Andrei Osterman, the Naval Military Commission was established to reform the fleet[p. 7], which included Vice-Admiral Count Nikolai Golovin, Vice-Admiral Naum Senyavin, Vice-Admiral Thomas Sanders, Rear-Admiral Pyotr Bredal and Rear-Admiral Vasily Dmitriev-Mamonov, a management reform was carried out, and new fleet staffing levels were introduced.

According to the 1732 staffing level, the main ships in the navy were 66-gun ships, which were to make up 59% of the fleet. In doing so, the commission proceeded from the following considerations:

The design features of Russian 66-gun ships allowed them to carry guns of the same caliber as the guns of 70-gun ships of foreign fleets. The 66-gun ships already existed in the fleet, and upon their disposal, part of their rigging and artillery could be used to equip new ships, and artillery and rigging accounted for 28-38% of the cost of the entire ship.

The total number of ships of the line remained unchanged: 27. The total gun force of the fleet remained unchanged. According to Peter the Great’s staff, taking into account the planned introduction of a 100-gun ship, the fleet was to have 1,854 guns. According to the 1732 staff, the ships were to have 1,754 guns, and taking into account the commission’s decision on the mandatory presence of one 100-gun ship in the fleet outside the staff – 1,854 guns. The fleet staff introduced in 1732 remained unchanged until the reign of Catherine II.

In August 1732, a decision was made to restore the Arkhangelsk port, closed in 1722, and military shipbuilding in Solombala, which played a huge role in the development of the fleet and shipbuilding. The Solombala shipyard became the second main construction base of the Baltic Fleet and began work in 1734. Conceived for the construction of lower-ranking ships – 54-gun ships, in 1737 it began building 66-gun ships, and from 1783, 74-gun ships began to be built in Arkhangelsk. During the reign of Anna Ioannovna, 52.6% of all ships of the Baltic Fleet were built in Arkhangelsk, and 64.1% under Elizabeth Petrovna. During the period 1731-1799, 55 ships were built in St. Petersburg (with Kronstadt), and 100 in Arkhangelsk.

The creation of the Arkhangelsk shipyard made it possible to quickly and efficiently launch the construction of a large number of ships, using local larch and saving the limited resources of ship oak. The Arkhangelsk shipyard actually became the main shipbuilding base of the Baltic Fleet. The availability of skilled labor, shorter delivery times for timber and better organization of its procurement led to the fact that the cost and time of ship construction in Arkhangelsk were less than in St. Petersburg.

In May 1734, when, during the War of the Polish Succession, the Russian fleet under the command of Thomas Gordon went to sea to besiege Danzig, it consisted of 14 ships of the line, 5 frigates, 2 bombardment ships and small vessels, and in the two months that had passed since the beginning of the war, the fleet increased the number of combat-ready ships of the line and frigates from 10 to 19.

Despite the decline in the shipbuilding program in 1736-1739 due to the war with Turkey, when intensive construction of the Dnieper and Azov flotillas was underway, during the reign of Empress Anna Ioannovna there was some progress in the state of the fleet. If in 1731 the fleet had only 8 fully combat-ready ships of the line, and another 5 were of limited combat capability, then in 1739 there were already 16 fully combat-ready ships of the line and another 5 were of limited combat capability. After the end of the war with Turkey, the Admiralty resumed intensive construction of the fleet in the shortest possible time: in 1739, 2 ships of the line were laid down, in 1740 – 3, and in 1741 – 5 ships of the line at once.

During the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna

During the Russo-Swedish War of 1741-1743, the Russian fleet, in contrast to the successful actions of the army, distinguished itself by its astonishing inaction. Zakhar Mishukov, commanding a fleet equal to the enemy’s, showed indecision and took advantage of every possible circumstance to avoid meeting the Swedish fleet, which was trying with equal persistence to evade the Russian. In 1743, command of the entire fleet was entrusted to Nikolai Golovin, who was ordered “if need be, to attack the enemy fleet not only with a force superior to the enemy’s, in the number of ships and guns, but also with an equal force.” But Golovin, approaching Gangut in May 1743, stood for some time inactive at anchor near the Swedish fleet; and then both fleets, built in a battle line, held out at sea for more than a day, one opposite the other, and separated after an insignificant exchange of fire between the vanguard ships that had approached each other.

During the fourteen years of peace that passed from the end of the Swedish War to the beginning of the Seven Years’ War, the activities of the Russian fleet were limited to annual practical voyages in the Baltic Sea. Although in Russian historiography the period of the reign of Elizabeth I (1741-1762) is sometimes called “the time of the revival of the fleet”, in fact one can only speak of some progress in comparison with the previous reign. In general, the ships were dilapidated, their number was less than required by the staff, there was a chronic shortage of crews, due to which at the beginning of naval campaigns it was necessary to send soldiers to the ships. The experience of voyages was very limited. In 1752, the Naval Gentry Cadet Corps was opened to train naval officers.

At the beginning of the Seven Years’ War in 1757, the fleet, which went to sea under the command of Zakhar Mishukov, was ordered to blockade Prussian ports and act against the British fleet if it came to the aid of Prussia. The fleet also participated in the siege of Memel that year. In 1760-61, the fleet participated in the siege of Kolberg.

The Russian Empire Navy in the Second Half of the 18th Century

Battle of Chesma with the Turks in 1770. Painting by I. Aivazovsky

The fleet met the beginning of Catherine’s reign in a sad state. At the end of the Seven Years’ War, 10 ships of the line, 3 frigates, 43 galleys were written off due to dilapidation, while the production of new ships was significantly less than their loss. Expenditures on the fleet from 1757 to 1767 decreased from 1,200 thousand rubles per year to 589 thousand. Empress Catherine II understood that without a strong fleet, the development of the state and its due role in European politics could not be ensured. On November 17, 1763, the “Naval Russian Fleet and Admiralty Administration Commission for the purpose of bringing this notable part (fleet) to the defense of the state in real, permanent good order” was established. The frigate “Nadezhda Blagopoluchiya” became the first Russian-built ship to visit the Mediterranean Sea in 1764-1765. The restoration of the fleet began.

In the second half of the 18th century, the Russian fleet was strengthened due to Russia’s more active foreign policy and the Russo-Turkish wars for dominance in the Black Sea. For the first time in its history, Russia sent naval squadrons from the Baltic Sea to a distant theater of military operations (see Archipelago expeditions of the Russian fleet, First Archipelago expedition). During the Battle of Chesma in 1770, Admiral Spiridov’s squadron defeated the Turkish fleet and achieved dominance in the Aegean Sea. In 1771, the Russian Imperial Army conquered the coast of the Kerch Strait and captured the fortresses of Kerch and Yenikale.

After the Russian troops approached the Danube, the Danube Military Flotilla was formed to protect the mouth of the river.

In 1773, the ships of the Azov Flotilla (re-formed in 1771) entered the Black Sea.

The Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774) ended with a victory for Russia, as a result of which the entire coast of the Sea of Azov and part of the Black Sea coastline between the Southern Bug and Dniester rivers went to Russia. In 1783, Crimea was annexed to Russia and in the same year the main base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, Sevastopol, was founded, and the Akhtiar Admiralty was founded.

In 1778, the port of Kherson was founded, where the first ship for the Black Sea Fleet was launched in 1783. In 1788, the Nikolaev Admiralty was founded.

The Russian Black Sea Fleet successfully fought the Turkish fleet in the Black Sea in the following Russo-Turkish War (1787-1791).

By 1791, the Russian fleet consisted of 67 ships of the line, 40 frigates and 300 rowboats.

In 1798-1800, the Russian squadron under the command of Admiral Ushakov made an expedition to the Mediterranean Sea. As a result of the campaign, the French fortress on the island of Corfu was captured and landing forces were landed on the coast of Italy.

19th century

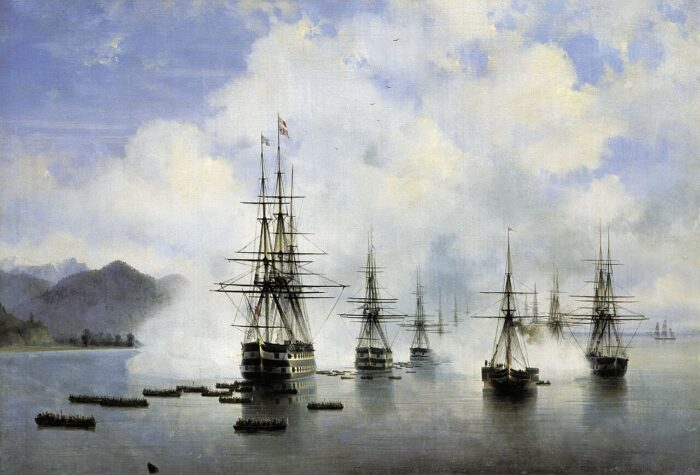

Russian squadron under the command of F. F. Ushakov sailing through the Strait of Constantinople. Artist M. Ivanov

The Black Sea Fleet consisted of 5 battleships and 19 frigates (1787), the Baltic Fleet had 23 battleships and 130 frigates (1788).

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Russian Imperial Fleet consisted of the Baltic and Black Sea Fleets, the Caspian Flotilla, the White Sea Flotilla, and the Okhotsk Flotilla. In 1802, the Ministry of Naval Forces was created (renamed the Naval Ministry in 1815).

In 1815, the first steamship “Elizaveta” was built in Russia, in 1826 the first military steamship “Izhora” (73.6 kW or 100 hp) armed with 8 guns was built, and in 1836 – the steam frigate “Bogatyr” (displacement – 1340 tons, capacity – 117 kW (240 hp), armament – 28 guns).

Between 1803 and 1855, Russian navigators made more than 40 round-the-world and long-distance voyages, which played a significant role in the development of the Far East, various oceans and the Pacific operational region.

In 1803-1806, Russian sailors completed the first Russian circumnavigation of the globe, and in 1819-1821, the First Russian Antarctic Expedition took place, which resulted in the discovery of Antarctica. On June 17, 1819, Emperor Alexander I instituted the St. George Flag for courage and bravery. In 1834, Russia tested the first all-metal submarine of K. A. Schilder.

Raevsky’s landing at Subashi. I. Aivazovsky

The fleet continued to successfully conduct military operations. During the Russo-Turkish wars of the first half of the 19th century, the Russian fleet made two expeditions to the Mediterranean Sea (the Second Archipelago Expedition and the Third Archipelago Expedition). During the expeditions, the Russian fleet inflicted a number of defeats on the Turkish fleet (the Battle of Athos, the Battle of Navarino). The fleet also participated in the Caucasian War, landing troops in 1837-38, which built fortifications on the Black Sea coastline. Photo: Pavel Nakhimov which commanded the fleet at Sinop and later took command of the siege of Sevastopol.

The fleet continued to successfully conduct military operations. During the Russo-Turkish wars of the first half of the 19th century, the Russian fleet made two expeditions to the Mediterranean Sea (the Second Archipelago Expedition and the Third Archipelago Expedition). During the expeditions, the Russian fleet inflicted a number of defeats on the Turkish fleet (the Battle of Athos, the Battle of Navarino). The fleet also participated in the Caucasian War, landing troops in 1837-38, which built fortifications on the Black Sea coastline. Photo: Pavel Nakhimov which commanded the fleet at Sinop and later took command of the siege of Sevastopol.

However, during the reign of Alexander I, a period of decline began for the navy, which he inherited as one of the strongest in the world (which determined its successes in the first decade of the 19th century), but by the end of his reign it was lagging behind the leading powers. Alexander considered Russia a continental power and viewed the navy as a burden, and his long-term Minister of the Navy, Marquis I. I. de Traversay, was guided by the opinion of the emperor.

Nicholas I, who succeeded him on the throne, believed that Russia was obliged to have a strong navy and from the first years of his reign revived mass shipbuilding. But by providing huge amounts of money for the construction of battleships and frigates, the emperor and A. S. Menshikov, the leader of the Russian navy he appointed, missed the mass transition of European fleets to steam shipbuilding. The technical backwardness of the fleet could not be compensated for by the heroism of Russian sailors in the grand pan-European war that ended the reign of Nicholas I.

The Crimean War and its aftermath

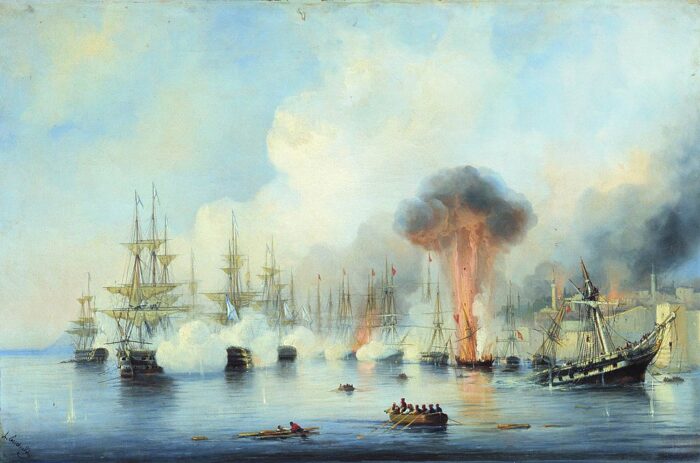

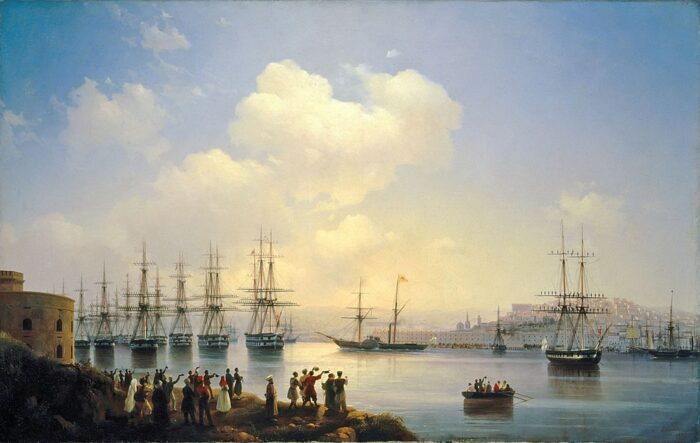

Review of the Black Sea Fleet in 1849 in front of the Emperor. Painting by I. Aivazovsky

The slow economic and industrial development of Russia in the first half of the 19th century led to its lagging behind in the field of steamship construction. By the beginning of the Crimean War in 1853, Russia had the Black Sea and Baltic fleets, the Arkhangelsk, Caspian and Siberian flotillas – a total of 40 battleships, 15 frigates, 24 corvettes and brigs, 18 steam frigates. At the same time, by the beginning of the war, the Russian fleet did not have a single steam battleship.

The total number of personnel in the fleet was 91 thousand people. Serfdom had a very unfavorable effect on the development of the navy – especially in the Baltic Fleet, which was known for its particularly harsh training.

Thanks to Admirals Mikhail Lazarev, Pavel Nakhimov, Vladimir Kornilov and Vladimir Istomin, the sailors of the Black Sea Fleet were well trained in the art of naval affairs and the maritime traditions that had been maintained since the time of Admiral Ushakov.

At the beginning of the war, the Russian Black Sea Fleet defeated the Turkish fleet in the Battle of Sinop in 1853.

Battle of Sinope, 1853

The Battle of Sinope, fatal to the Ottoman fleet in 1853. Painting by I. Aivazovsky

Later Operations

However, with the entry of the Anglo-French fleet into the war, the Russian sailing fleet found itself in a losing position and was sunk in the bay of Sevastopol, and the sailors went ashore to defend the city. During the defense of Sevastopol in 1854-1855, Russian sailors showed an example of using all possible means to defend their city at sea and on land. The steam frigates of the Russian fleet were not sunk and, while in the bay, supported the city’s defense with artillery fire.

At the same time, the Baltic Fleet survived, taking refuge in Kronstadt under the protection of sea minefields and coastal artillery. The Allied fleet was never able to break through to the main port of the Baltic Fleet. As a result of the Paris Peace Treaty of 1856, Russia lost the right to have a navy in the Black Sea.

Postwar reforms

In the 1860s, the outdated sailing fleet of the Russian Empire lost its significance and was replaced by a steam fleet.

After the end of the Crimean War, Russia began building first-generation steam warships: battleships, monitors, and floating batteries. These ships were equipped with heavy artillery and thick armor, but were unreliable on the open sea, slow, and could not make long sea voyages. In 1861, the first combat ship with steel armor was launched — the gunboat Opyt.

In 1862, a committee was established to develop a new shipbuilding program. At the same time, it was decided to armor the frigates Sevastopol and Petropavlovsk that were under construction. In the same year, the construction of the floating battery Pervenets was ordered in Great Britain. Then, according to the drawings of Pervenets, the second floating armored coastal defense battery Ne tron menya was built in Russia, and then the third floating battery — Kreml. In 1863, the first armored squadron (Practical Squadron of the Baltic Sea, Training Squadron of the Baltic Fleet) was formed as part of the Baltic Fleet under the command of Vice-Admiral G. I. Butakov. It included the armored wooden frigates Petropavlovsk and Sevastopol, a steamship, two steam frigates and two gunboats. But only three floating batteries of the Pervenets type made up the armored fleet that could operate in the open sea.

In 1869, the first armored ship designed for sailing in the open sea was laid down – Pyotr Velikiy.

Next: The Russian Navy up to the war of 1878 and 1905.

The Russian Navy, Battle Order

Battle of Sinope 1853:

–Velikiy Knyaz Konstantin, ship of the line, 120 guns

-Tri Sviatitelia, ship of the line, 120 guns

-Parizh, 120 guns, ship of the line, transferred flagship

-Imperatritsa Maria, ship of the line, 84 guns, flagship

-Chesma, ship of the line, 84 guns

-Rostislav, ship of the line, 84 guns

-Kulevich, frigate, 54 guns

-Kagul, frigate, 44 guns

-Odessa, Krym, Khersones, 12(4)guns paddle steamers

Vice-Admiral Pavel Nakhimov, commanding the 84-gun battleships Empress Maria, Chesma and Rostislav, was sent by the Minister of the Navy Prince Menshikov to the shores of Anatolia: information had been received that the Turks in Sinop were preparing forces for a landing at Sukhum and Poti.

Approaching Sinop on November 11 (23), Nakhimov discovered a detachment of Turkish ships in the bay protected by 6 coastal batteries and decided to blockade the port in order to attack the enemy upon the arrival of reinforcements from Sevastopol.

On November 16 (28), Nakhimov’s detachment was joined by the squadron of Rear Admiral Fyodor Novosilsky (the 120-gun battleships Paris, Grand Duke Konstantin and Three Saints, the frigates Kagul and Kulevchi). It was assumed that the Turks could be reinforced by the allied Anglo-French fleet, located in the Bay of Beshik-Kertez (Dardanelles Strait).

Sinope Battle Plan

It was decided to attack in 2 columns: in the 1st, closest to the enemy – the battleships of Nakhimov’s detachment, in the 2nd – Novosilsky, the frigates were to be under sail, observing the enemy steamers; it was decided to spare the consular houses and the city in general, if possible, hitting only the ships and batteries. For the first time, it was supposed to use 68-pound bombardment guns.

On the morning of November 18 (November 30), it was raining with a gusty wind from the OSO, the most unfavorable for capturing Turkish ships, since they could easily be thrown ashore.

At 9.30, keeping the rowboats at the sides of the ships, the squadron headed for the roadstead. In the depths of the bay, 7 Turkish frigates and 3 corvettes were located in an arc under the cover of 4 batteries (one with 8 guns, 3 with 6 guns each); behind the battle line were 2 steamships and 2 transport ships.

At 12.30, after the first shot of the 44-gun frigate “Aunni-Allah”, fire was opened from all Turkish ships and batteries.

The ship of the line “Empress Maria” was showered with cannonballs, most of its spars and standing rigging were broken, only one shroud remained intact at the mainmast. However, the ship moved forward without stopping and, using battle fire on the enemy ships, dropped anchor opposite the frigate Aunni-Allah; the latter, unable to withstand half an hour of shelling, ran aground. Then the Russian flagship turned its fire exclusively on the 44-gun frigate Fazli-Allah, which soon caught fire and also ran aground. After this, the guns of the ship Empress Maria concentrated on battery No. 5.

Grand Duke Constantine, having dropped anchor, opened heavy fire on battery No. 4 and the 60-gun frigates Navek-Bahri and Nesimi-Zefer; the former was blown up 20 minutes after opening fire, showering battery No. 4 with debris and bodies of sailors, which then almost ceased to function; the second was thrown ashore by the wind when its anchor chain was cut.

Chesma destroyed batteries No. 4 and No. 3 with its shots.

Paris, anchored, opened fire on battery No. 5, the corvette Guli-Sefid (22-gun) and the frigate Damiad (56-gun); then, having blown up the corvette and thrown the frigate ashore, it began to hit the frigate Nizamiye (64-gun), whose foremast and mizzen masts were knocked down, and the ship itself drifted to the shore, where it soon caught fire. Then the Paris began firing at Battery No. 5 again.

The battleship Tri Svyatitelya entered the fight with the frigates Kaidi-Zefer (54-gun) and Nizamiye; the first enemy shots broke its mainspring, and the ship, turning into the wind, was subjected to accurate longitudinal fire from Battery No. 6, whereby its masts were severely damaged. Having turned its stern again, it began to act very successfully against Kaidi-Zefer and other ships and forced them to rush to the shore.

The battleship Rostislav, covering Tri Svyatitelya, concentrated its fire on Battery No. 6 and the corvette Feyze-Meabud (24-gun), and threw the corvette back to the shore.

At 13.30, the Russian steam frigate Odessa appeared from behind the cape under the flag of Adjutant General Vice-Admiral V. A. Kornilov, accompanied by the steam frigates Crimea and Khersones. These ships immediately took part in the battle, which, however, was already drawing to an end; the Turkish forces were greatly weakened. Batteries No. 5 and No. 6 continued to harass the Russian ships until 4 o’clock, but Paris and Rostislav soon destroyed them. Meanwhile, the remaining Turkish ships, apparently set on fire by their crews, blew up one after another; as a result, a fire spread throughout the city, which there was no one to put out.

At about 2 p.m., the Turkish 22-gun steam frigate Taif, armed with 2 – 10-inch bomb, 4 – 42-pound, 16 – 24-pound guns, under the command of Yahya-bey, broke away from the line of Turkish ships, which were suffering a severe defeat, and fled. Taking advantage of the Taif’s speed advantage, Yahya-bey managed to escape from the Russian ships pursuing him (the frigates Kagul and Kulevchi, then the steam frigates of Kornilov’s detachment) and report to Istanbul about the complete destruction of the Turkish squadron. Captain Yahya Bey, who expected a reward for saving the ship, was dismissed from service with deprivation of rank for “unworthy behavior.” Sultan Abdul-Mecid was very unhappy with the escape of the Taif, saying:

“I would have preferred that it did not escape, but died in battle, like the others.”

According to the French official source “Le Moniteur”, whose correspondent visited the Taif immediately after its return to Istanbul, there were 11 killed and 17 wounded on the steam frigate.

According to other sources, the steam frigate Taif, under the command of the British captain Slad, slipped out of Sinop Bay at the very beginning of the battle. Leaving the roadstead, the Taif ran into the frigates Kagul and Kulevchi, which rushed in pursuit of it. Around 2:00 p.m., Taif also met Kornilov’s steam frigates, but was able to escape them. Kornilov arrived in Sinop Bay around 4:00 p.m., when the battle was already virtually over[2].

The broadsword of the Turkish squadron commander Osman Pasha, which he gave to the victors (Russian Black Sea Fleet Museum in Sevastopol)

Among the prisoners were the commander of the Turkish squadron, Vice Admiral Osman Pasha, and two ship commanders.

After the battle, the ships of the Russian fleet began to repair the damage to the rigging and spars, and on November 20 (December 2) they weighed anchor to proceed to Sevastopol in tow of the steamers. Beyond Cape Sinop, the squadron encountered a large swell from the northeast, so that the steamers were forced to give up the tugs. During the night the wind grew stronger, and the ships moved on under sail. On November 22 (December 4), around midday, the victorious ships entered the Sevastopol roadstead amidst general jubilation.

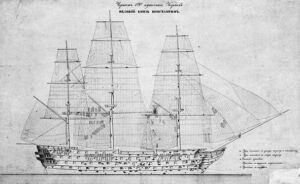

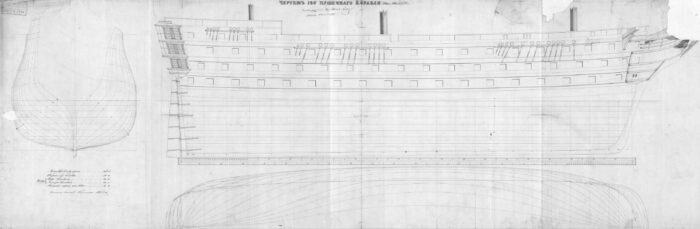

This class comprised three 120-gun ships of the line.

“The Twelve Apostles” was a 1st rank ship in the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Empire, part of the fleet from 1841 to 1855, and lead ship of of her class taking part in the Crimean War. She also carried troops, and during the defense of Sevastopol she was sunk in the roadstead in order to block its entry.

“Grand Duke Constantine” was a sailing ship of the line of the Black Sea Fleet from 1852 to 1855. One of three ships of the “Twelve Apostles” class. Participant in the Crimean War, including the Battle of Sinop. During her service, she took part in numerous naval exercises and carried troops. At the end of the defense of Sevastopol, she was sunk in the roadstead when the garrison abandoned the city. “Paris” of the three was perhaps the best in the battle of Sinope, sinking more ships and most decorated.

Tri Sviatelia (1838)

Tri Sviatelia (1838)

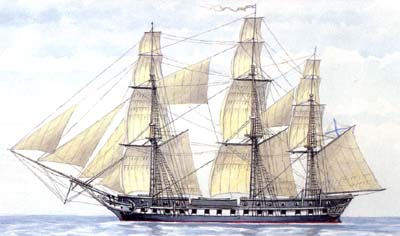

“Tri Svyatelya” is a 120-guns (built 1835-38) single class sailing ship of the line of the Black Sea Fleet, part of the fleet from 1838 to 1854, a participant in the Crimean War, including the Battle of Sinop. During her service, it mostly participated in Black Sea exercises, trips and transportation of troops, and during the defense of Sevastopol, she was sunk in the roadstead in order to block the entry of enemy ships.

Imperatritsa Maria

Imperatritsa Maria

84 guns ship of the line, flagship. More to come if info is find.

Chesma

Chesma

ship of the line, 84 guns. More to come if info is find.

Rostislav

Rostislav

Ship of the line, 84 guns More to come if info is find. Likely all three belonged to the same class.

Kulevchi (1847)

Kulevchi (1847)

“Kulevchi” is a 60-gun sailing frigate of the Black Sea Fleet, taking part in the Battle of Sinop, named in memory of the victory of Russian troops under the command of Field Marshal I. I. Dibich over Turkish troops on May 30, 1829 near Kulevchi. Construction started on March 18, 1844, she was launched on September 20, 1847, Commissioned in 1847, scuttled on August 28, 1855 in the Sevastopol roadstead when the garrison abandoned the city.

Kagul

Kagul

“Kahul” was a 44-gun sailing frigate of the Black Sea Fleet, taking part in the Crimean War, including the Battle of Sinop. Construction started on October 31 (November 12), 1840, she was launched on September 17 (29), 1843, Commissioned that year, and on February 13 (25), 1855, scuttled in the Sevastopol roadstead between the Mikhailovskaya and Nikolaevskaya batteries.

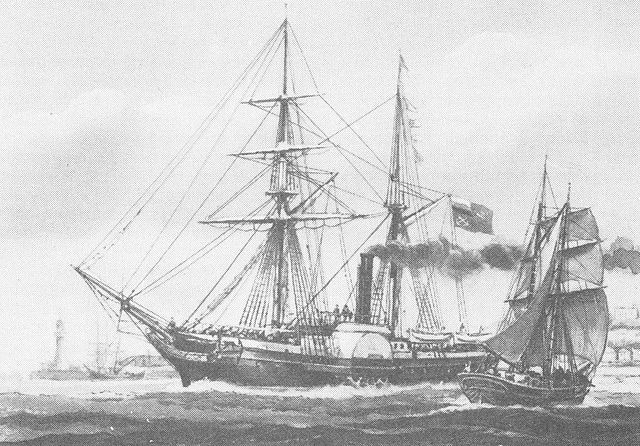

Odessa

Odessa

“Odessa” is a paddle steam frigate of the Black Sea Fleet, one of four identical steam frigates ordered in England and participating in operations of the Crimean War. Manufactured by W. & H. Pitcher yard she was launched in 1843, Commissioned the same year and scuttled in August 1855 in the Northern Bay.

She was in the same class as “Krym” and “Khersones”. All three were of mixed construction and armed wiht 12 guns. They were 1305 tons 53.3 x 9.7 m x 4.47 m ships powered by two unbalanced two-cylinder steam engines for 260 hp and 2 side paddle wheels plus sails capable of 11 knots.

At Sinope they sank the following:

-Frigate Aunni Allah — 44 guns (washed ashore)

-Frigate Fazli Allah — 44 guns (caught fire, washed ashore)

-Frigate Nizamiye — 62 guns (washed ashore after losing two masts)

-Frigate Nesimi Zefer — 60 guns (washed ashore after anchor chain was broken)

-Frigate Navek Bahri — 58 guns (exploded)

-Frigate Damiad (Egyptian) — 56 guns (washed ashore)

-Frigate Qaidi Zefer — 54 guns (washed ashore)

-Corvette Nejm Fishan — 24 guns

-Corvette Feyze Meabud — 24 guns (washed ashore)

-Corvette Guli Sefid — 22 guns (exploded)

-Steamer frigate Taif — 22 guns (went to Istanbul)

-Steamer Erkile — 2 guns

More to come !

More to come !

Russian Empire naval forces, order of battle (in writing):

– Screw three deckers: In research

– Screw two deckers: In research

– Screw frigates: In research

– Screw Corvettes: In research

– Paddle frigates: In research

– Paddle corvettes: In research

– Screw sloops: In research

– Paddle sloops: In research

– Screw gunboats: In research

– Sailing ships of the Line: In research

– Sailing Frigates: In research

– Sailing corvettes: In research

– Brigs: In research

Read More/Src

Books

Links

en.wikipedia.org Imperial_Russian_Navy

ru.wikipedia.org/ the imperial fleet

en.wikipedia.org/ List of Russian sail frigates

commons.wikimedia.org Battle_of_Kinburn_(1855) pics

Siege_of_Petropavlovsk pics

tri sviatitelia

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign