The last Japanese capital ships built in UK:

The Kongo class were the first and last IJN battlecruisers, studied from 1911. Due to the 1902 Anglo-Japanese naval alliance, Japan was the third country to embark on this new breed, and its lead ship, IJN Kongo, was also the last capital ship the Rising sun Empire ordered in the United Kingdom. This habit started in 1890 and confirmed by Tsushima ended there. These battle cruisers were based on the best design British Yards had to offer at the time, the “splendid cats”. But the IJN admiralty’s request made them diverge significantly from their British equivalents. Their replacements were designed in Japan during WW1 but were never completed due to the 1922 Washington treaty. In the interwar and up to WW2, more were studied but none was built, the last to counter the US Alaska class.

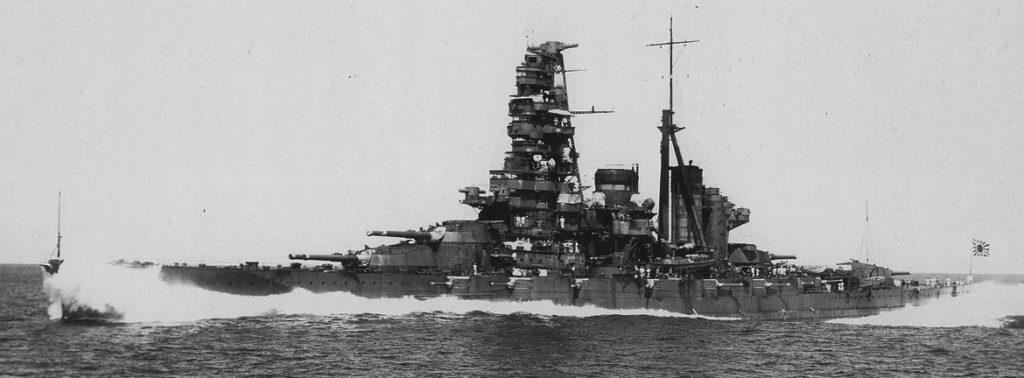

All four were ready on time to take part on WW1, but saw little action after 1914 due to their use in a quiet theatre at that time. They were however modernized and improved in several steps during the interwar, and after their last great modernization in the 1930s, emerged as “fast battleships” and no longer battlecruisers. They participated in many operations from 1937 to 1945, two were famously lost at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, 13 November 1942 (Hiei and kirishima), Kongō by a submarine in 1944, and one sunk by US aviation in July 1945 (Haruna) and later BU.

Development

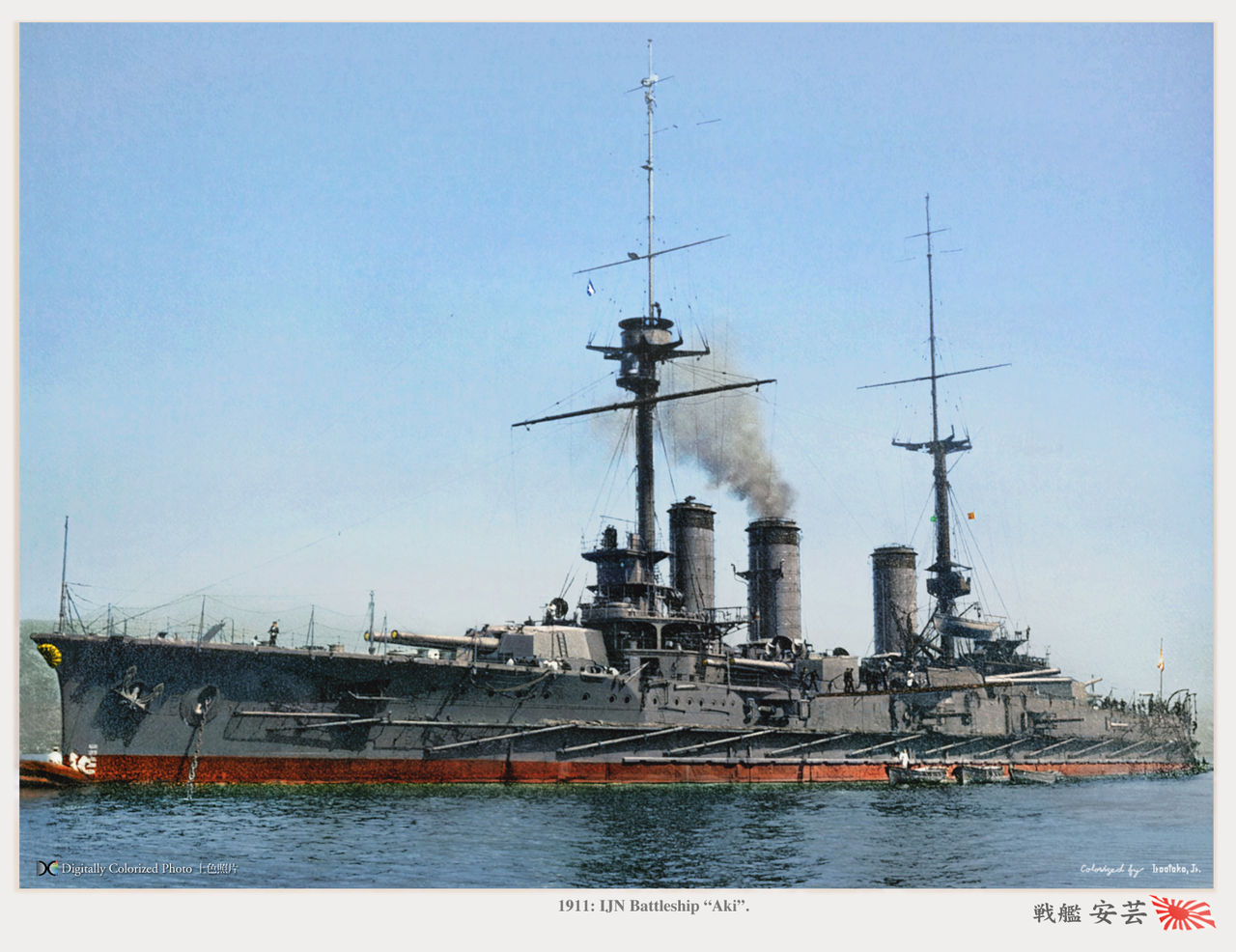

IJN Aki. The Satsuma class were predecessors of the Kongo, only semi-dreadnoughts and first battleships designed and built in Japan (colorized by Irootoko Jr.)

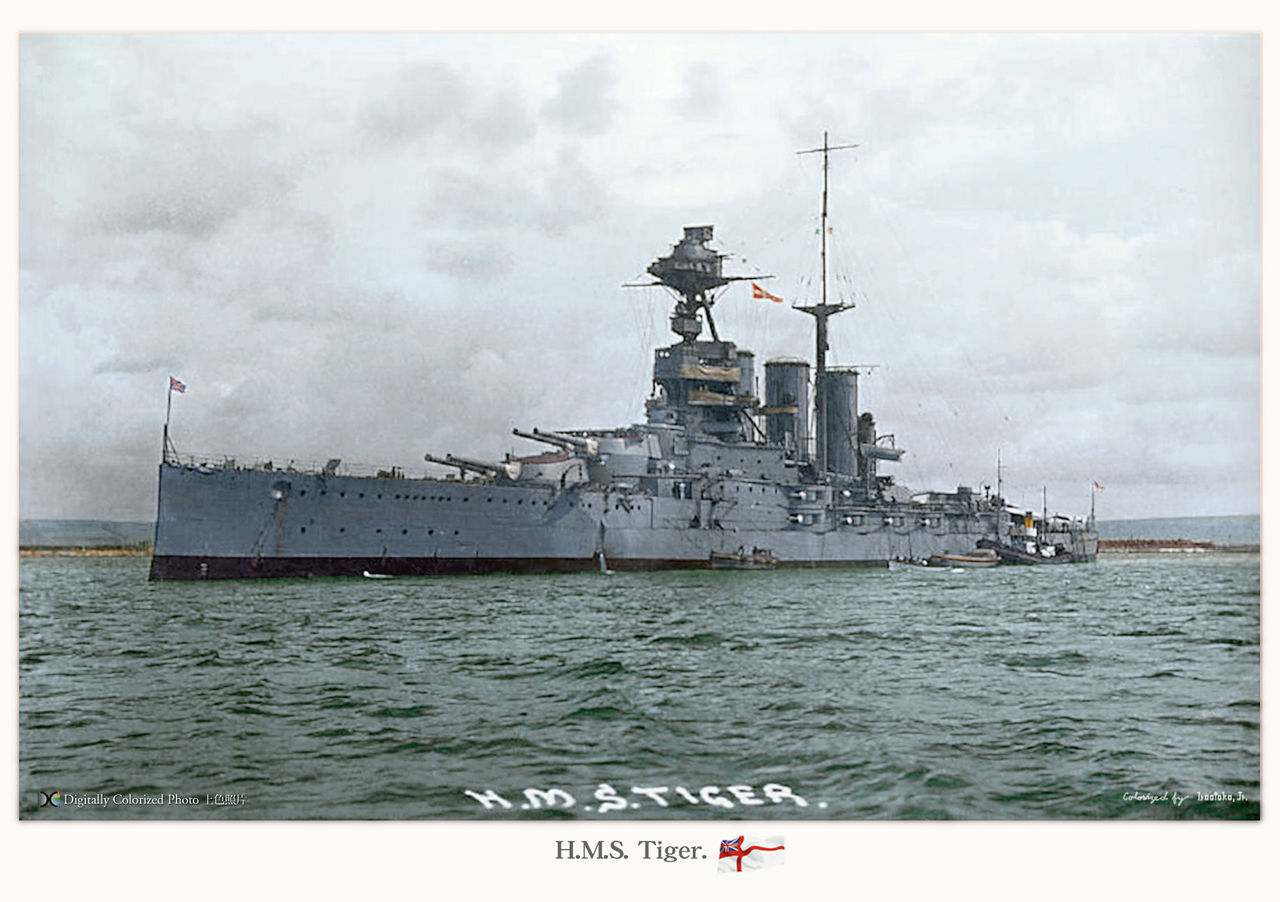

The design of the Kongō-class was linked to the IJN’s modernization programs, and the growing perceived need to compete with the British Royal Navy, which bounced up in March 1908, when was launched HMS Invincible. Because of her speed and uniform eight 12-inch main guns, she made Japanese capital ships obsolete, including the Satsuma class. The Japanese Diet passed in 1911 the “Emergency Naval Expansion Bill”, authorizing one first battleship (IJN Fusō) and four “armoured cruisers”, to be designed by British naval architect George Thurston. Thurston developmental design basically relied on recipe which would be applied in the British Battlecruiser HMS Tiger. A contract was signed with Vickers in November 1910. IJN Kongō was confirmed to be built at Vickers, with terms maximizing naval technology transfer to Japan. Vickers Design was named 472C (Japanese B-46), featuring eight or ten 12-inch (304.8 mm)/50 guns, sixteen 6-inch (152 mm) guns plus eight 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes.

HMS Tiger, which construction was halted to integrate Kongo class design features. Colorized by Irootoko Jr.

A Japanese delegation was sent to follow these development at Vickers Yard. This team comprised 100 technical specialists, sent for 18 months in UK. It was headed by Commander Katô Hirohasu. The latter pushed for the adoption of a new 14-inch (356 mm)/45 calibre gun under development at Elswick at the time. He was present at its fire trials and pushed for the decision on 29 Nov 1911 to use it. The battlecruiser’s keel had been laid down already on 17 January 1911, requiring many alterations of the design. These were made at a frantic pace so to not delay the launching. Before it, with rotation, and comprising superintendents, supervisors and trial witnesses, about 200 Japanese spent a tour of duty there. Their task was self-evident, gather as many technical information as possible to make possible the construction of sister-ships back in Japan.

The final design was basically an improved Lion class, displacing on paper 27,940 tonnes (27,500 long tons), and carrying a final main battery of eight 14-inch guns in four twin gun turrets, two forward and two aft, the latter further apart. As designed it was provided for a top speed of 27.5 knots.

Design

Overall, the IJN design was loosely based on HMS Princess Royal built at the same time. Like her, Kongo had three uneven-sized funnels, a square bow, a pointed and tapered stern, offset C and D turrets. But she also had a relatively weak underwater defense, and light armoured protection at large. These were large ships anyway, with 215 m long from stern to stem, displacing more than 27,000 tonnes standard, and a 27 knots top speed.

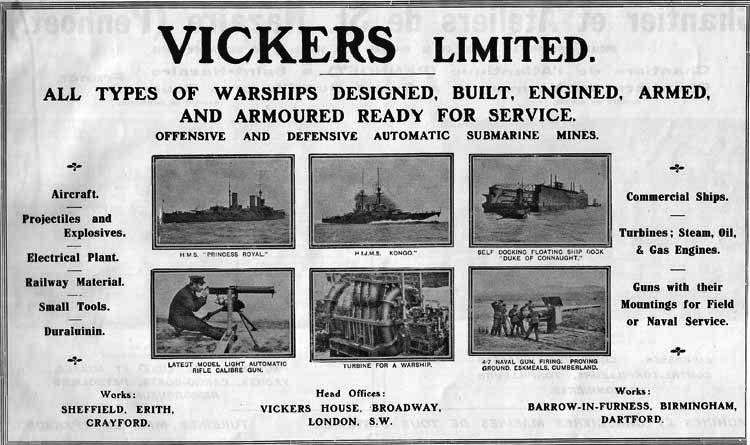

Vickers Advertisement in Janes 1914 showing the Kongo

Powerplant

The Kongō-class were of course equipped with British-built steam turbines. There were two sets of Parsons, direct-drive models, on all ships except IJN Haruna: She had Brown-Curtis turbines instead. This will take time before the Japanese were able to replicate these locally. The high-pressure turbines drove the outwards shafts and low-pressure one the inner shafts. They were arranged in two compartments separated by a centerline longitudinal bulkhead for ASW protection. These were located under and between turrets No. 3 and 4 and designed to produce a total output of 65,000 shaft horsepower (48,000 kW). Steam came from 36 Yarrow (or Kampon on all next three ships) water-tube boilers. Working pressure on average was 17.1, up to 19.2 atm (1,733 to 1,945 kPa and 251 to 282 psi). They were located in eight separated compartments. These boilers used mixed-firing: Standard burn was coal, but with fuel oil injection for extra boost. Their stowage capacity reached 4,200 long tons for coal, 1,000 long tons for oil. This enable them an overall max range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at their design cruiser speed of 14 knots. As designed, top speed was 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) but on sea trials, Kongō and Hiei reached 27.54 knots and 27.72 knots respectively based on an output of 78,275 shp and 76,127 shp. They were reboilered during the interwar.

Yarrow watertube boilers as preserved from IJN Kongo

Armament

Primary:

Eight 14″/45 Vickers/Elswick guns, in four superfiring twin-gun turrets.

Turrets elevation was −5/+20 degrees in the Japanese versions. Kongō, which had British turrets, could elevate to +25 degrees. crucially, these mounts allowed the shells to be loaded at any angle and their firing cycle was 30–40 seconds.

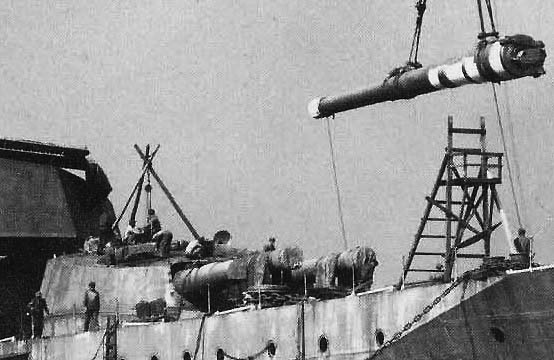

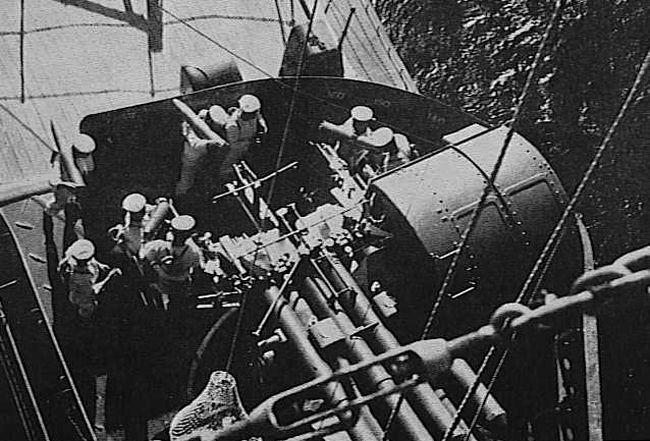

Haruna’ 14 inch gun installation 1914

Secondary:

The Kongō class was given a total of sixteen 15 cm/50 guns mounted in single casemates, along either sides of the hull. They were all at the level of the upper deck, meaning in heavy weather they had the same problems as all casemates mounted that way. Eight were mounted on either side with an arc of fire on average of 130 degrees, maximum elevation of only +15 degrees. They fired a 45.36 kg (100 lb) HE shell at 22,970 yards (21,000 m). The rate of fire was 4-6 per minute depending on the crew and conditions.

Tertiary:

Four 76 mm/40 anti-aircraft (AA) guns were installed on the decks. These 3 in high-angle Vickers guns in single mounts could elevated to +75 degrees, firing a 6 kg (13 lb) shell at 680 m/s (2,200 ft/s). Their useful ceiling was 7,500 metres (24,600 ft). Also all battlecruisers were equipped with the standard torpedo tubes, all submerged and in groups in the broadside: Eight 21 inches (533 mm) torpedo tubes, four on each broadside.

Armour Protection

The Kongō-class were battlecruisers, and thus, were given plenty of output to maximize speed and manoeuvrability. They ended with a thinner armour compared to the next Fuso and Ise of course, but still, they possessed an impressive armour scheme, that would be much heavily upgraded during the interwar years. It used Vickers Cemented plates, on the first, but Krupp Cemented Armour for the next three built in Japan. Subsequent developments of domestic armour technology led to a hybrid design of Vickers and Krupp styles, until the Yamato class armour design in 1938. Here are these figures:

Armoured belt: Upper 6 inches (152 mm); lower 8 inches (203 mm). Bow and stern down to 3 inches (76 mm)

Conning tower: 14 inches (360 mm)

Main Turrets: 10 in front (254 mm), 9 inches (229 mm) back and sides

Barbettes: 3 in lower level blow deck, 10 in above deck (76-254 mm)

Decks armour: Lower: Lower 1 in (25 mm), middle 1.5 in (38 mm), Upper: 2.75 in (70 mm).

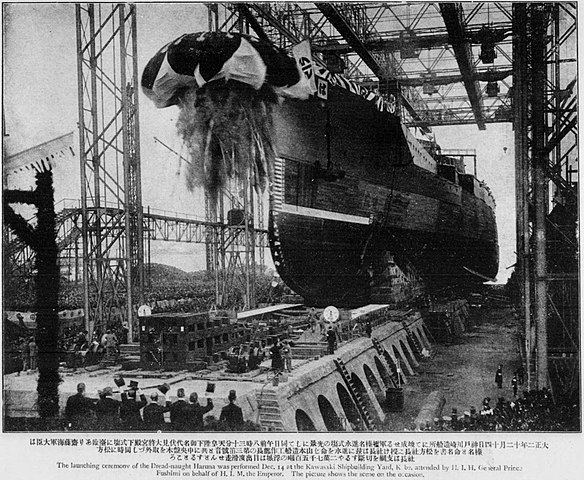

Launch of IJN Haruna, December 1913

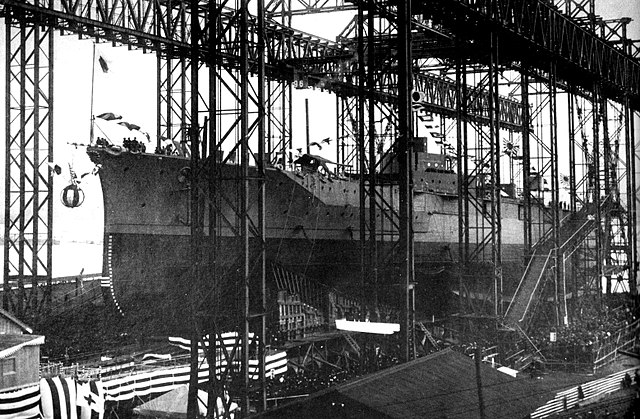

Launch of IJN Kirishima, the same day.

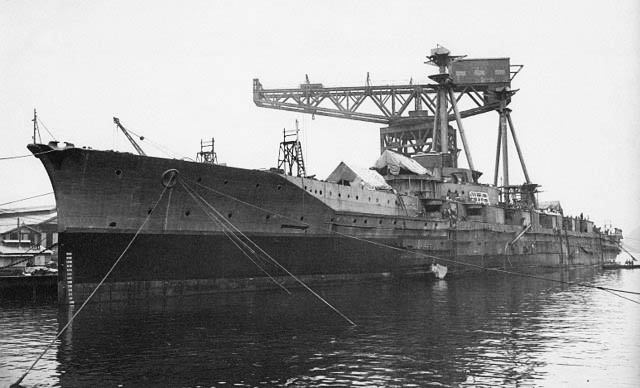

IJN Haruna (top) and Hiei fitting out, in Sasebo and Yokosuka

WW1 service

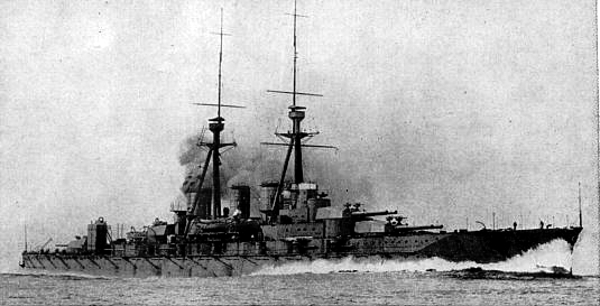

The Kongo class ships were completed in 1913-14: IJN Kongo on 16 August 1913, IJN Hiei built at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, Yokosuka, on 4 August 1914, and IJN Haruna and Kirishima, built at Mitsubishi Shipyard Co., Nagasaki and Kawasaki Dockyard Co., Kobe, on 19 April 1915. Both had been launched in December 1913. Due to a lack of available slipways, the last two were the first Japanese warships made in private shipyards. According to naval historian Robert Jackson, they “outclassed all other contemporary capital ships” at the time. This was, admitedly by the British themselves, such as good design that construction of the fourth battlecruiser Lion-class, HMS Tiger, was halted to integrate features seen on the Kongō class, and she ended as a much different ship altogether.

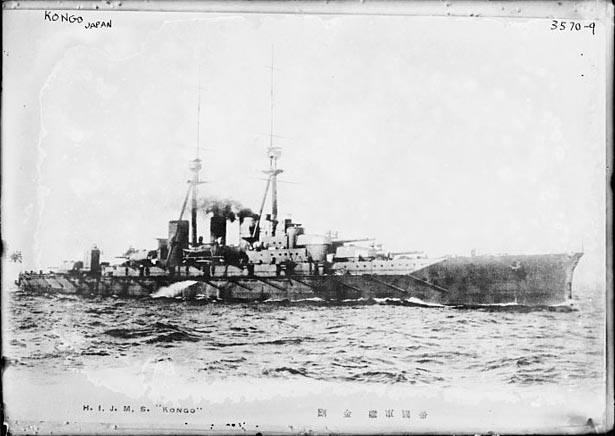

IJN Kongo in 1914-1919:

IJN Kongo in sea trials, 1914

On 16 August 1913, IJN Kongō was completed and 12 days later departed Portsmouth for Japan. She arrived and stayed in Singapore 20-27 October, and headed for Yokosuka Naval Arsenal where she arrived on 5 November, placed in First Reserve waiting for the January 1914 Kure Naval Base armament checks. On 3 August 1914, was broke out anf 12 days later, Japan warned Kaiser Wilhelm II of to withdraw German troops from Tsingtao. The German Empire never responded which in return triggered an official declaration of war on 23 August 1914. The Japanese Imperial Fleet was therefore deployed to seize all former German possessions in the Caroline, Palau, Marshall, and Marianas Islands and Tsingtau as well in China (this was a joint operation with the RN). IJN Kongō was quickly deployed in Central Pacific to patrol sea lines of the German Empire. Graf Spee’s squadron however was nowhere to be found. IJN Kongō was back in Yokosuka, on 12 September, and in October returned with the First Battleship Division, sailing with her sister ship IJN Hiei. They patrolled the Chinese coast, in support during the Siege of Tsingtao. Kongō went back later to Sasebo Naval Base for upgrades, being fitted new searchlights. On 3 October 1915, she and Hiei sank the old Imperator Nikolai I (IJN Iki, a coastal defense ship) as a practice target, captured in 1905 and used by the I.J.N. until then, and now declared obsolete. As the German East Asia Squadron was obliterated by the Royal Navy in the Falkland by December 1914, the I.J.N. had nothing to do in the Pacific Ocean and IJN Kongō spent the next years, and until 1918 rotating between Sasebo and the coast of China for patrol duties. By December 1918 she was placed in “Second Reserve”, and reactivated in April 1919, to be fitted with a new seawater flooding system for her ammunition magazines. See more for her interwar career later in this page.

Postcard of IJN Kongo in Japan, 1914

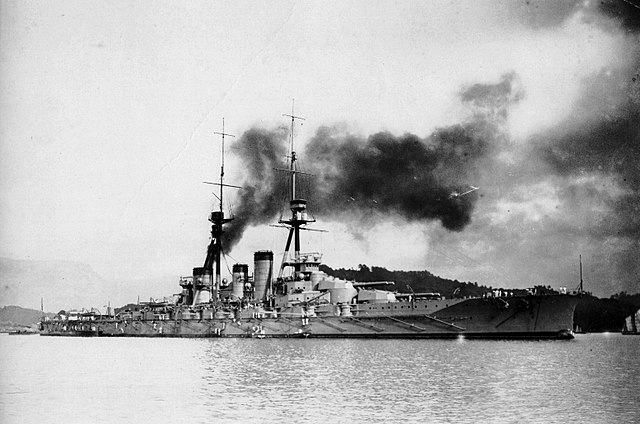

IJN Hiei in ww1:

built in Japan unlike her sister ship, at Yokosuka, and completed at Sasebo, Hiei was commissioned 4 August 1914. She stayed for training in the Sasebo Naval District and was attached to the Third Battleship Division, First Fleet in mid-August. On the 23 Japan was at war with the German Empire and started to operated against German colonial islands in the Pacific. In October 1914, Hiei departed with Kongō to cover the IJN operations during the Siege of Tsingtao, before being recalled on 17 October. On year after, on 3 October 1915, Hiei and Kongō sank in an artillery training exercise the old Imperator Nikolai I. In April 1916, Hiei was sent to patrol the Chinese coast with Kirishima and Haruna. From 1917 to the end of the war, she stayed mostly in Sasebo, and was sent for occasional Chinese and Korean patrols.

IJN Hiei in Sasebo, 1915

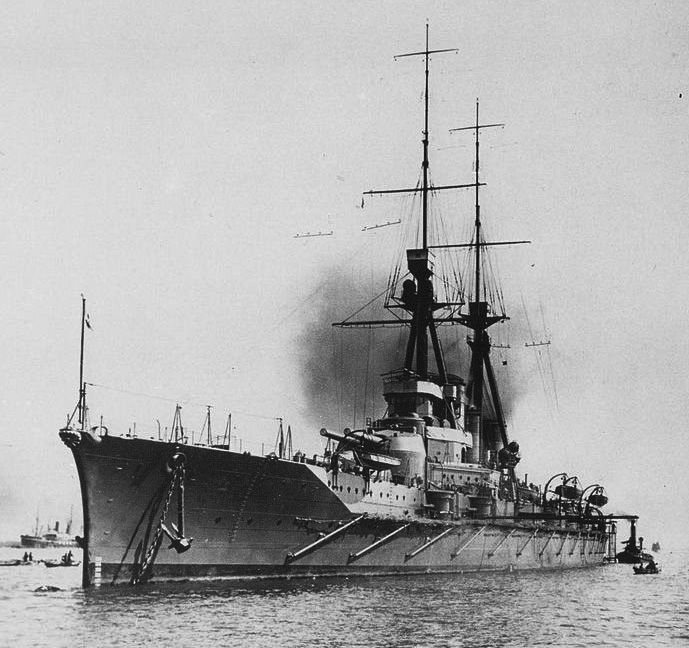

IJN Haruna & Kirishima in ww1:

Both were launched in December 1913 and completed the same day 19 April 1915, so WW1 was in full swing and operations against the German Empire were over. So there was little to do for them. Kirishima was formally commissioned on 19 April 1915. She joined Haruna in the 1st Battleship Division of the First Fleet. Her trials and exercises lasted for seven months, after which she was reassigned to the 3rd Battleship Division, Second Fleet. Captain Shima Takeshi took command and by April 1916, she departed with Haruna the Sasebo Naval Base for the East China Sea. Both patrolled these waters for ten days and were back to Sasebo until April 1917. Another patrol cruise was made with Haruna and Kongō and the last patrol operation was made off the Chinese and Korean coast in April 1918. In July, IJN Kirishima carried Prince Arthur of Connaught for his cruise to Canada, and headed back to Japan at the end of the war. Haruna was commissioned on 19 April 1915 in Kobe. She could start unit operations from December 1915, after eight months of trials and training. She joined the Third Battleship Division, Second Fleet. She joined her sister ship for Chinese coast cruises, in April 1916, 1917 and 1918. Since 1st December 1916, Captain Saburo Hyakutake was her captain, replaced on 15 September 1917 by Naomi Taniguchi. On 1st December 1917 she was placed in reserve.

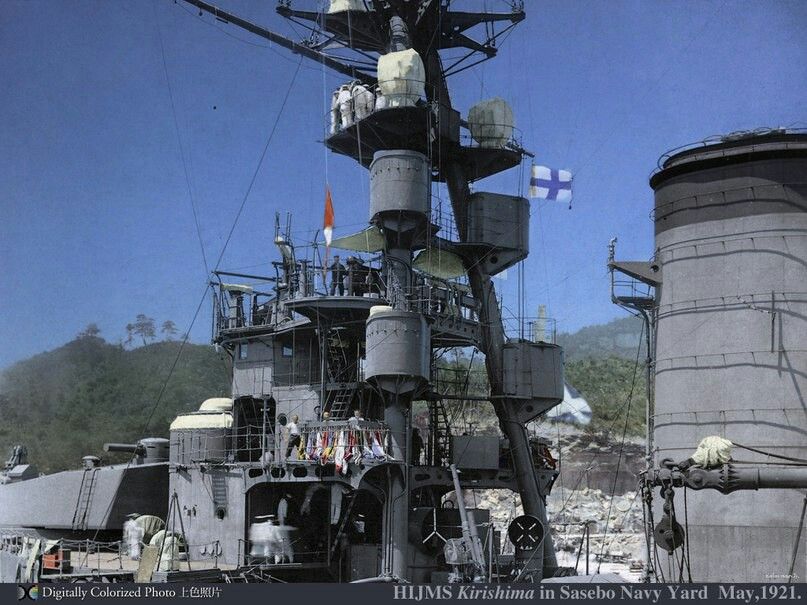

IJN Kirishima in Sasebo, 1915

IJN Haruna in Kobe, 1915

IJN Hiei in Yokosua, 1914

Interwar: From battlecruiser to fast battleships

Pre-reconstruction career, 1919-1929

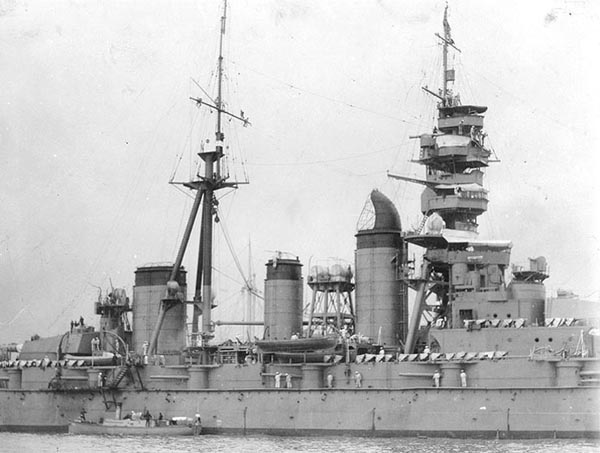

IJN Kongo midship view in the 1927-28 after her first modernization.

In fact upgrades and modernization took place already in the early 1920s. After the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty on 6 February 1922, the I.J.N. was limited with an inferior ratio to the UK and US, and the capital ships ban until 1931 was seen as a double blow for the admiralty, stopping dead their ambitious 1919 naval program. Nevertheless the treaty allowed existing capital ships to be upgraded, but only with improved anti-torpedo bulges and armored main decks. Japan would take full advantage of this, and thee Ise and Fusō class were modernized, but even more so the Kongō-class battlecruisers.

In April 1923, Kongō receive the honor to host Emperor Hirohito for his official journey to Taiwan, In Japanese hands by then. On 14 June 1924, Kongō collided with Submarine No. 62 during exercises, but repairs were quick. However in November that year she was docked at Yokosuka to see her main armament removed, and the gun mounts replaced by newer models for increased elevation. She also received new main fire-control systems and in 1925, 1927, and 1928 she was further upgraded and modified in steps: First a new pagoda-like superstructure, to accommodate fire-control systems and others, and by 1928, the steering equipment. Her main reconstruction started in 1929, and she was put in reserve.

IJN Kongo during Prince Hiro-Hito visit to Taiwan in 1923

Hiei on her side made a last patrol with Haruna and Kirishima off the Chinese coast in March 1919 and was inactive for the next year, and by October 1920 she was placed in reserve. The Great Kantō earthquake (September 1923) saw her assisting in rescue work. She was back at Kure on 1 December 1923 for the same gun mount refit her her sister ships would have, and later her foremast was modified, with extra platforms. By July 1927, she hosted Crown Prince Takamatsu, Emperor Hirohito’s younger brother. She was refitted at Sasebo in October-November 1927, taking onboard for the first time two Yokosuka E1Y floatplanes, lifted by the main ship’s boom. By March 1928 she departed with Kongō, Nagato and Fusō to patrol off the Chusan Archipelago and arrived in April in Port Arthur. By October 1929 she was to Kure to be decommissioned and prepared for her great reconstruction.

IJN Kirishisma patrolled with Kongō and Nagato off the Chinese coast in August 1921 and in September 1922 collided with the destroyer IJN Fuji during maneuvers, but only resulting in minor damage. She assisted populations after the Great Kantō earthquake and joined the reserve in December 1923. Nothing much happened until it was decided to rebuilt her.

By September 1920, IJN Haruna was making gunnery drills off Hokkaidō when she suffered a catastrophic breech explosion. The starboard gun of No. 1 turret blew up, killing seven and denting the armored roof. The Investigation concluded it was caused by a faulty fuse and inspections were made on all of these throughout IJN capital ships. The turret was repaired at Yokosuka and at the same occasion, all gun mounts were changed to allow more elevation. She was placed in reserve later and waited until decommissioned for a comprehensive reconstruction like her sister ship.

Kongo after her first reconstruction

Second reconstruction (1926-33)

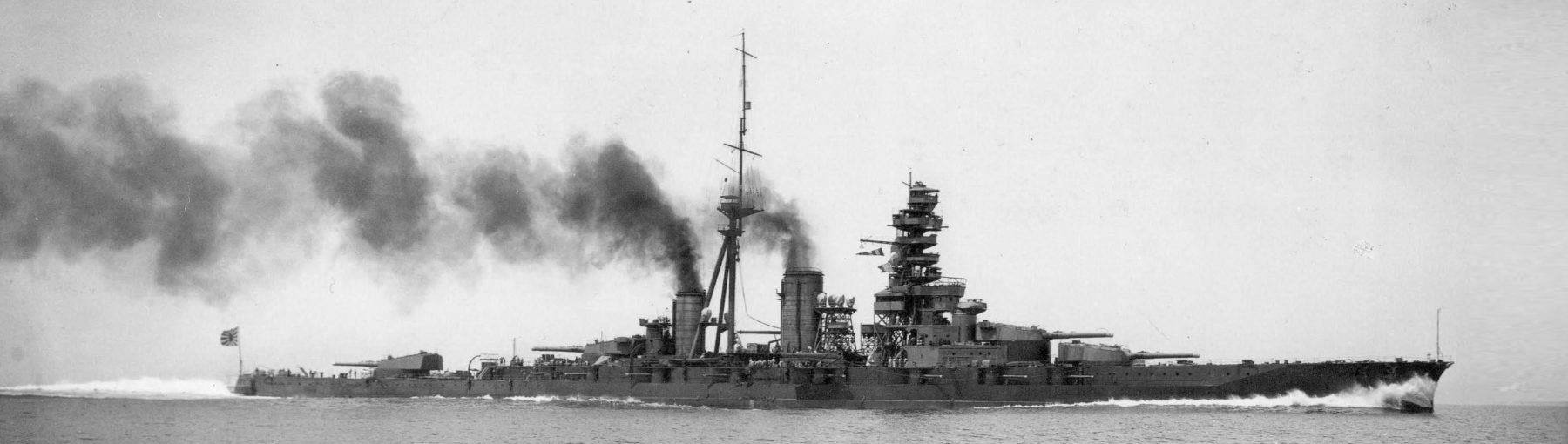

From 1928 until 1931, all four ships underwent a thorough reconstruction, total, radical, virtually changing everything from the keel up as it was allowed by the Washington treaty. First priority was to increase armor and modernizing their propulsion system second (notably oil-only boilers to free internal space). The hull was extended and elongated aaft to help reaching a better top speed alongside extra output. This could have resulted in amazing speeds if that was not for all the added weight. Their protection was considerably reinforced all around, and the ship took close to 10,000 tons more (mostly armour) while still capable of 26 knots. They rightly entered the category of “fast battleships”. A second powerplant refit was made in the late 1930s, helping them achieving a top speed of 30,5 knots. In 20 years, their output more than doubled.

IJN Haruna before her refit

In July 1926, IJN Haruna was in fact the first IJN capital ship to undergo such modernization and modifications. She was immobilized in drydock at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal for two years, decommissioned and her cres re-affected on other ships. Her horizontal armor was improved to better protect her ammunition magazines and machinery spaces armor improved, as well as anti-torpedo bulges added along the waterline. She also received new accommodation and cranes to operate three Type 90 floatplanes. For the powerplant, all Yarrow boilers were replaced with less than half the number of modern oil-firing boilers, and the turbines replaced by modern Brown-Curtis direct-drive models. Her forward funnel was removed, exhausts truncated into the enlarged second, now taller funnel. Total armor weight increased from 6,502 to 10,313 long tons, so the end result was in clear violation of the Washington Treaty, while she was also capable of 29 knots and protected enough to be the first IJN “fast battleship”, as reclassified in the IJN ordnance. After her new sea trials, she joined on 10 December 1928 the Fourth Battleship Division, Second Fleet and was the Emperor’s special ship. She hosted the prince between Sasebo, Port Arthur, and the East China Sea and also Prince Takamatsu, younger brother, was assigned to the crew. By November 1929, she joined again the First Battleship Division. but was in reserve from December 1930.

In April 1930, Japan signed the London Naval Treaty and had to scrap older battleships but alos delayed new construction before 1937. By September 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria and the league of nations in February 1933 denounced the invasion as violating Chinese sovereignty, and Japan withdrew from the organization, and soon ripped off its Washington and London Naval Treaties. As a result, all limitations were lifted and IJN Haruna and other ships in reserve were reactivated while later reconstructions were even more radical as Japan did not feared any retaliation.

Armament

The main guns turrets their mounts and barrels were changed or refitted several times until 1941. At first, elevation was set to +33 degrees (+900 m), next the recoil mechanism was modernized, swapping from an hydraulic to a pneumatic system enabling faster cycling. In 1939 also, the first storage of the new Type 91 armor-piercing capped shells arrived. The latter weighted 673.5 kgs (1,485 lb) for a muzzle velocity of 775 mps (2,540 ft/s). Their larger propellant charge added to mounts greater elevation now allowed a range from 25,000 meters (27,000 yd) (effective fire) to 35,450 meters at 33° (maximal range). These shells were seconded by 625-kilogram HE models, with a muzzle velocity of 805 mps and in 1942-43, the special Type 3 Sanshikidan, famous AA incendiary shrapnel shell, transforming her guns, basically, into giant shotguns. The second reconstruction saw the removal of two after casemate guns, still leaving fourteen 6-in guns for closer defence.

In the 1930s, the old 76 mm guns were considered obsolete and replaced by eight 127 mm (5 in)/40 dual-purpose guns, fitted alongside the fore and aft towers, both in twin-gun mounts. Standard range was 14,700 metres (16,100 yd), ceiling 9,440 metres (30,970 ft) at +90°. Max. rate of fire was 14 rounds/minute, down to 8 sustained. Lastly, a brand new light AA armament was fitted, especially in the 1933-1944 period, constantly improved and almost tripled. The second reconstruction saw on all ships eight twin 13.2 mm (0.52 in) HMGs fitted, replaced later by 25 mm (0.98 in) gun mount, single twin or triple, derived from the old license-built Hotchkiss models of ww1. This standard had severe design shortcomings and notably the twin/triple mounts were slow to traverse and elevate while gun sights proved obsolete for 400 kph plus aircraft of the 1940s. In addition they displayed excessive vibration, small magazine and excessive muzzle blast blinding the pointer and gunners during firing. Haruna ufor example had at the end of her career no les than 118 guns of them: 30 triple, two twin, 24 single.

Hiei at Sasebo NyD 1926

New powerplant

The first reconstruction saw mostly a reboilering of all ships. The numerous classic coal-burning models were replaced by with 11 (on Hiei) or 16 (on Haruna) Japanese Kampon boilers, still burning coal but with important oil injection, or mixed. Stowage now comprised 2,661 long tons (2,704 t) of coal, 3,292 long tons (3,345 t) of oil, enhancing their range to 8,930 nautical miles (16,540 km; 10,280 mi). The fore funnel was removed, eliminating smoke interference on the main fire-controls. Top speed due to increased displacement fell to 26 knots so prompting the admiralty to have them reclassified as battleships. But thier 1930s reconstructions was arimed at turning them to fast battleships again. The admiralty settled on eleven oil-fired Kampon boilers, much upgraded models whoch fed the turbines and now allowed speeds in excess of 30.5 knots, so they soon became available to escort fast aircraft carriers.

Battleship Haruna in 1934

One of their most characteristic, iconic reconstruction symbol was their large “pagoda”, a serie of bridges and platforms installed along the forward tripod mast. They were light enough not to compromise stability, but still acted as “sails” in heavy winds. The British in fact did the same with their own Queen Elisabeth class but on shorter tripods. Later these complicated structures were entirely removed and three of the latter, QE 2, Warspite and Valiant, had sturdied, lower blockhouses instead. The “pagoda craze” reached its caricatural achievement with the Fuso and Yamashiro.

Revised armour

Each of these battleships also underwent armour changed, relatively limited at first on Haruna and Kongo, and unleashed after Japan ripped off all treaties. The main lower belt at first was given an even thickness of 8 inches, diagonal bulkheads were now up to 5-8 inches (127-203 mm) additional to the main armoured belt. The upper belt was closed by 9-inches (230 mm) bulkheads to close the citadel close to the barbettes. The turret armour reached 10 inches (254 mm) face, and deck armour received an additional layer of 4 inches (102 mm). All four ships gained 4,000 tons of armour, and already violated Washington limits, but it was not even close to what followed. Nevertheless, this protection was sub-part on the Kongō class compared to contemporary capital ships and this had consequences at Guadalcanal. The ASW protection was considerably reinforced with the ad-junction in 1944 of massive ASW bulges.

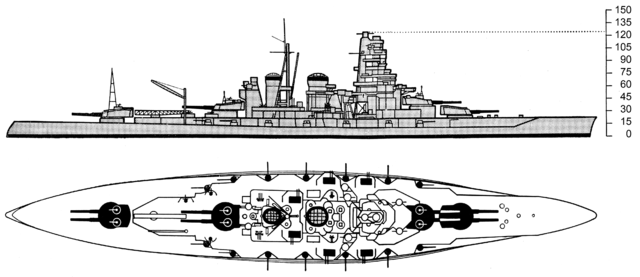

ONI – Kongo schematics recoignition plate, 1944

Specifications (1915)

Displacement: 27,384 tonnes standard

Dimensions: 214.58 m x 28,04 m x 8,22 m fully loaded

Propulsion: 4 shafts, 2 Parsons turbines, 36 boilers, 64 600 hp, top speed 27,5 knots, range 8,000 nm/14kts

Armour: Belt 203 mm, turrets 254 mm, decks 25 mm, CT 230 mm

Armament: 8 x 356 mm (4×2), 16 x 152 mm barbettes, 4 x 76 mm AA, 8 x 533 mm TTs

Crew: 1,193

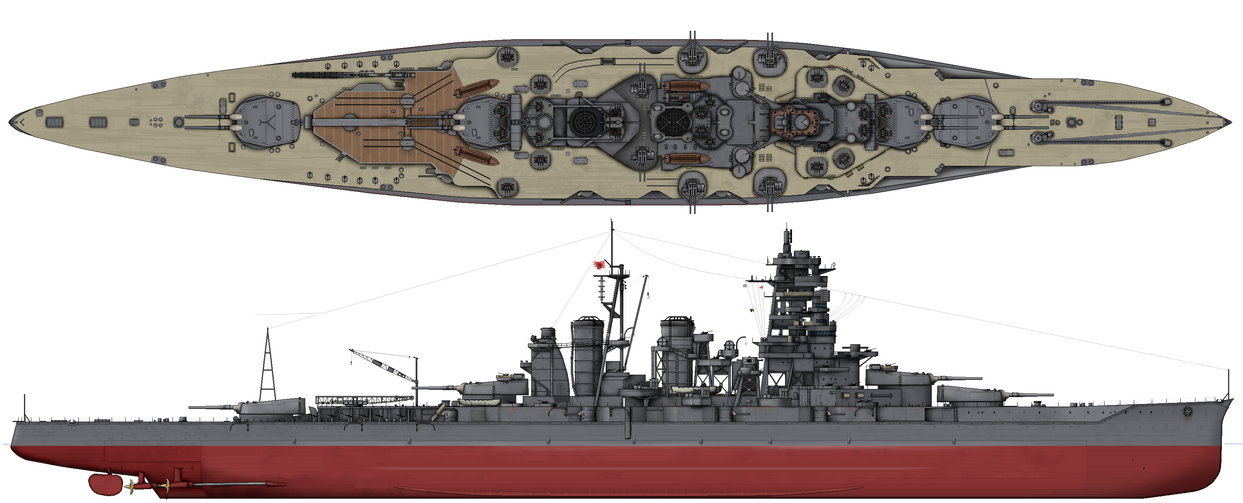

WoW’s renditions of the Kongo in 1944

IJN Haruna sunk in Kure, photos by an Australian officer of the occupation force after the war (bottom), notice the elaborated camouflage, like other stationary battleships in Kure, with grades of green and stripes for the turrets.

Specifications (1944)

Displacement: 36 600 t. standard, 37 187 tonnes fully loaded

Dimensions: 220 m x 30,8 m x 9,7 m fully loaded

Propulsion: 4 propellers, 4 Parsons turbines, 11 boilers, 136 600 hp, top speed 30,5 knots, range 15,000 Km/26 knots

Armour: Belt 279 mm, turrets 227 mm, ammunition wells 101 mm, citadel 254 mm.

Armament: 8 x 356 mm (4×2), 8-14 x 152 mm barbettes, 4×2 127 mm AA, 60 x 25 mm Type 96 AA, 3 floatplanes.

*1945: Up to 118 x 25 mm AA in single, twin, triple mounts, a Type 21 air search radar, two Type 13 early warning radars, two Type 22 surface search radars.

Crew: 1437+

Illustrations

Hiei 1932

Kirishima in 1944

The Kongo class in action:

IJN Kongo:

By April 1923, Kongō hosted Emperor Hirohito during his official visit to Taiwan and by June 1924, she collided with Submarine No. 62 during maneuvers. In November she was in drydock at Yokosuka for main armament mounts elevation modifications and better fire-control. In 1927 other modifications followed, creating a pagoda-like superstructure, and in May 1928 her steering gear was improved, until she was put in reserve for her main reconstruction in 1929–31, ending in March 1931. By December 1932 Captain Nobutake Kondō assumed command of the vessel in December and in 1933, aircraft catapults were fitted between the two aft turrets, new floatplanes provided as well. By November 1934, Kongō was placed again in reserve for her second reconstruction. She hosted in January 1935 the Nazi German naval attaché to Japan, Captain Paul Wenneker during a fire exercize.

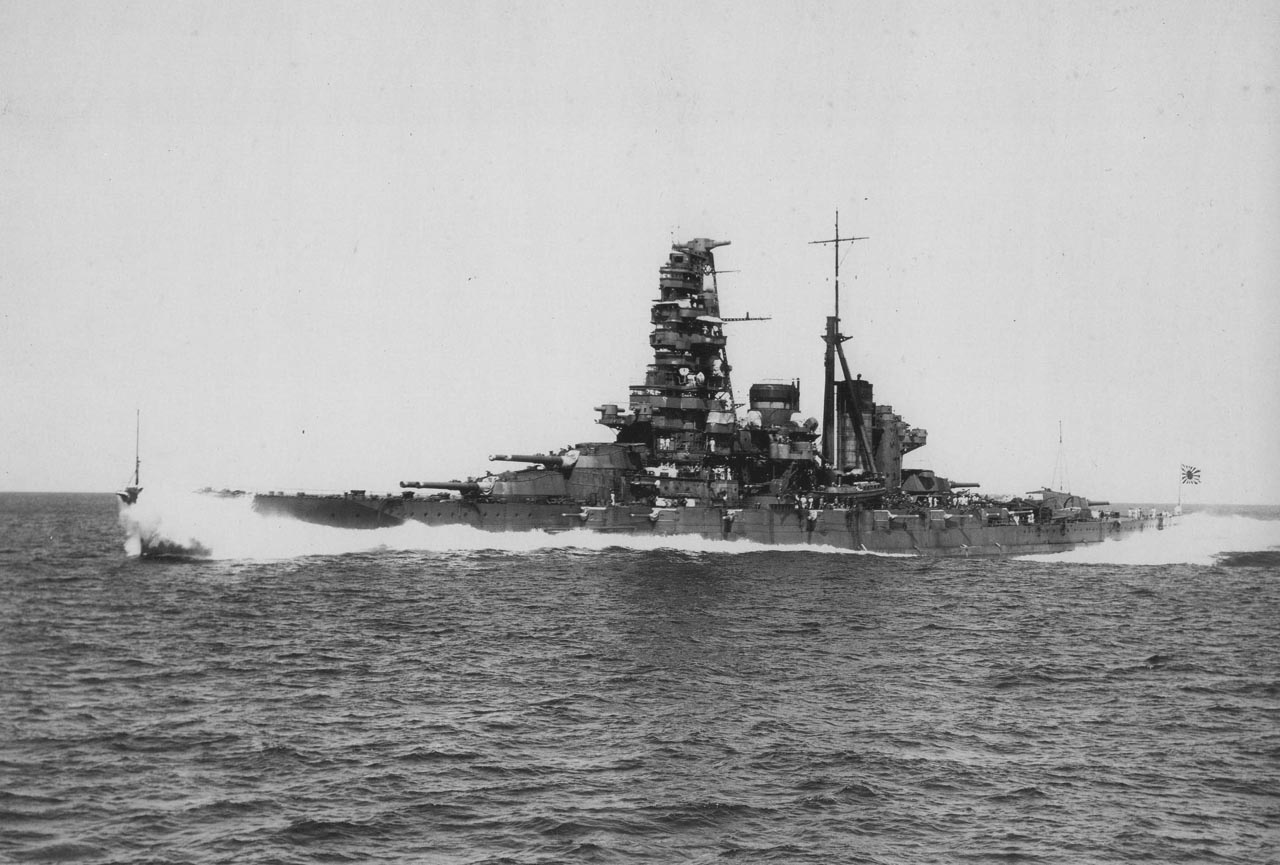

Upgrades started in drydock on 1st June 1935, at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal. The upgrades were intended to give her back speed to escort Japan’s new fleet aircraft carriers. Her stern was lengthened by 26 feet (7.9 m) for finer lines, all her boilers replaced as well as new geared turbines. Her bridge was reconstructed again in a more sturdy version of the “pagoda mast” completely masking the original tripod mast. Her catapults were replaced and modernized, and her air complement now comprised three Nakajima E8N or Kawanishi E7K floatplanes. Modifications also included armor upgrades: Main belt strengthened, diagonal bulkheads, turret armor, deck armor, ammunition magazine were also all reinforced. This was over by 8 January 1937 and she was now capable of 30 knots (56 km/h), reclassified as a fast battleship.

Nakajima E8N recce and spotter plane.

By February 1937, she had made her sea trials and was in training in the Sasebo Naval District. By December she was affected to the Third Battleship Division (Takeo Kurita). By April 1938, her floatplanes strafed and bombed Foochow during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Unil 1939 she patrolled off the Chinese coast and by November, Captain Raizo Tanaka took command. She was back again in drydock from November 1940 to April 1941 for additional armor on her barbettes and ammunition tubes. Ventilation and firefighting was also upgraded and by August 1941, she was in Third Battleship Division (Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa) together with her “family” all modernized, with Hiei, Kirishima and Haruna.

IJN Kongo off Amoy, China, in 1939

1942 campaigns

Kongō and Haruna left Hashirajima on 29 November 1941 to join the Southern (Malay) Force (Vice-Admiral Nobutake Kondō). On 4 December 1941, they operated off southern Thailand, northern Malaya to prepare and cover the double invasion that started on 8 December. While Force Z (Prince of Wales & Repulse) was destroyed by aviation from southern Vietnam, Kongō’s battlegroup retired and sortied from Indochina by mid-December for convoy escort bound to Malaya. On 18 December this battlecgroup covered landing at Lingayen Gulf (Luzon), part of the invasion of the Philippines. They sailed from Cam Ranh Bay (French Indochina) on 23 December, stopped in Taiwan and by January 1942, she was provided distant AA support together with Takao and Atago during an attack and landing on Ambon Island.

On 21 February 1942, Kongō and Haruna escorted a force of four fast aircraft carriers and five heavy cruisers for Operation J, the invasion of the Dutch East Indies. First she provided cover for air attacks on Java. She then headed for Australia, shelling Christmas Island off the western coast of Australia (7 March 1942). In April she escorted five fleet carriers for attacks on Colombo and Trincomalee (Ceylon), seeing the sinking of HMS Dorsetshire and Cornwall, before heading southwest to hunt down what was left of the British Eastern Fleet (Admiral James Somerville). While HMS Hermes was sunk south of Trincomalee, Kongō was attacked (but missed) by nine British medium bombers on 9 April. The Third Battleship Division headed back to Japan with an impressibe battle record, reaching Sasebo on 22 April. Until 2 May, Kongō was drydocked for modification and notably bolstering her AA armament.

On 27 May 1942, Kongō and Hiei, plus the cruisers Atago, Chōkai, Myōkō, and Haguro (Admiral Nobutake Kondō’s invasion force) participated in the Battle of Midway. On 14 July she became flagship of the restructured Third Battleship Division and by August she was in drydock at Kure for the installation of a radar and new range finders. By September 1942 she sailed with all her three sister ships with, three carriers and other ships for on Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands). On 20 September, they arrived at the Truk Naval Base.

After the Battle of Cape Esperance, the Japanese Army started carrying back troops reinforcements at Guadalcanal, with the help of the navy. Admiral Yamamoto sent Haruna and Kongō, a light cruiser and nine destroyers to try to reduced to rubble Henderson Field, the only US aviation air base on the island. These two fast battleships were ideally suited because of their rapid withdrawal capabilities, avoiding retaliation. In the night of 13–14 October, they shelled the field from 16,000 yards (15,000 m), in total pouring down 973 main guns high-explosive shells. It was their most successful action at Guadalcanal so far. The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands (26 October 1942) saw IJN Kongō attacked by Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers, which all failed. In November 1942 she provided distant cover for another shelling of Henderson Field, however after the loss of her sister ships Hiei and Kirishima at the Battle of Guadalcanal, the Third Battleship Division went back to Truk, remaining until the end of the year.

Operations of 1943

IJN Kongo in 1944 with her final AA arrangement, radar and some 6-in gins removed (cc)

This year, IJN Kongō participated in “Operation Ke” in January, a diversionary covering force for destroyers evacuating troops from Guadalcanal. Until 20 February 1943, the Third Battleship Division was moved to the Kure Naval Base. Kongō was drydocked for more AA addition, while two of her casemated 6-inch were retired. Concrete was poured into spaced between plates close to the steering gear. On 17 May 1943 Attu Island was invaded by US Forces and Kongō, Musashi with the Third Battleship Division which also comprised two fleet carriers, two cruisers, and nine destroyers made a sortie. On 19 May, USS Sawfish spotted this task force and on 22 May they arrived at Yokosuka for an addition of three fleet carriers, two light cruisers, but they never departed as news came of the fall of Attu. On 17 October 1943, Kongō left Truk with a task force of five battleships, three fleet carriers, eight heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and a dozen destroyers bound for Wake Island. They returned to Truk on 26 October 1943 and then headed for Japan, Sasebo in December for refits and training

Operations of 1944

The sinking of IJN kongo on 20 November 1944, hit by two torpedoes of the USS Sealion, a Gato class submarine (wow)

In January Kongō saw more AA modifications, four 6-inch removed and the addition of four 5-inch guns, four triple 25 mm mounts. She still was part of the the third Battleship Division (Ozawa), which left Kure on 8 March 1944 for Lingga, where they stayed until 11 May 1944. Admiral Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet then headed for Tawitawi to join Vice-Admiral Takeo Kurita’s “Force C”. On 13 June, Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet departed from Tawitawi and headed for the Mariana Islands, and soon the Battle of the Philippine Sea commenced. Kongō was by then escorting Japanese fast carriers and escape any damage on 20 June, she returned to Japan for more AA additions afterwards while by August 1944, two more 6-inch guns were removed and other additions of 25 mm mounts for a grand total of around 120.

By October 1944, Kongō departed Lingga for Operation Sho-1, and her participation to the climactic Battle of Leyte Gulf. On 24 October she had several near misses from air attacks during the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea. On 25 October she was at the Battle off Samar as part of Kurita’s Centre Force. She shelled ships of the US 7th Fleet’s “Taffy 3”, scoring hits on USS Gambier Bay and the destroyers USS Hoel and Heermann. She also sank the the DDE Samuel B. Roberts. But three Japanese heavy cruisers were sank and Admiral Kurita withdrew while Kongō suffered five near misses. They were in Brunei on 28 October and on 16 November, Kongō, Yamato, Nagato (First Fleet) departed Brunei for Kure.

On 20 November while across the Formosa Strait they were spotted by USS Sealion (by radar at 44,000 yards). The latter fired six bow torpedoes at IJN Kongō followed and emptied her three stern torpedoes at Nagato later. Two torpedoes hit Kongō on the port side, flooding two of her boiler rooms. She survived, and was able to resume her trip at 16 knots and later 11 knots, this time leaving the fleet and heading for Keelung (Formosa) escorted by Hamakaze and Isokaze. She was listing by then at 45° as the flooding progressed, until at 5:18 she lost all power. Order was given to abandon ship and around 5:24, her forward 14-inch magazine exploded. She broke in two and sank quickly with over 1,200 crew member, her captain and the commander of the Third Battleship Division, 237 survivors were rescued by the destroyers. This was about 55 nautical miles northwest of Keelung.

IJN Hiei

Hiei off Tsukugewan in post-reconstruction trials, 1938

During her major reconstruction, Hiei was modified as Kongo, receiving new oil-fired boilers and turbines, lengthened, had her aft 14-inch turret refitted, new fire control systems, improved elevation, catapults and two Nakajima E8N “Dave” and Kawanishi E7K “Alf” floatplanes, managed by launch-rails aft of the third turret. 5-inch DP guns, ten twin Type 96 25 mm AA guns were installed, and her superstructure rebuilt. On this, she was the first to inaugurate a new kind of tower-mast, testing a configuration later resued on the Yamato class. Her armor was also extensively upgraded and the whole process was complete by 31 January 1940. As a fast battleship, after trials and training she participated in the Imperial Fleet Review of October 1940 and inspected by Emperor Hirohito. By November she joined the Third Battleship Division, First Fleet. On 26 November 1941, she departed Hitokappu Bay in the Kurile Islands with Kirishima and the six “Kido Butai” Japanese fast carriers Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku (Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo). On 7 December 1941 she provided cover for the famous attack of Pearl Harbor.

On 17 January 1942, Hiei departed Truk with Third Battleship Division for an attack on Rabaul and Kavieng. By February, she operated in support of counter operations on the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. On 1st March, she provided cover for operations on Darwin and Java with IJN Kirishima and the cruiser Chikuma, escorting the carrier task force. They attacked the DD USS Edsall and Hiei fired 210 14-inch and 70 6-inch shells on the destroyer, without scoring a single hit. Following this, dive-bombers were scrambled and immobilized the destroyer, allowing to sink it by combined gunfire (This tells a lot about Japanese accuracy of the time…).

In April 1942, Hiei assisted a force of five fleet carriers and two cruisers for a “cleaning up” operation of the Indian Ocean. On 5 April, Colombo, Ceylon were attacked and two British cruisers sank. On 8 April, Trincomalee was attacked and one of Haruna’s plane spotted HMS Hermes, later sunk. The fleet was back to home base on 23 April. On 27 May, Hiei, Kongō, the cruisers Atago, Chōkai, Myōkō, Haguro (Admiral Nobutake Kondō) were present as distant cover at the Battle of Midway. Back home in July, IJN Hiei was drydocked for refits: New aircraft and additional AA were provided. In August 1942 she escorted IJN Shōkaku at the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. By October, she was sent as Rear Admiral Abe’s Vanguard Force in distant cover, when Kongō and Haruna shelled Henderson Field to smitherine on the night of 12-13 October. She was present also on 26–30 October at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.

On 10 November 1942, Hiei sailed from Truk with Kirishima and eleven destroyers (Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe) bound to Guadalcanal. The goal was Henderson Field and shelling the coast to prepare a landing. This forced was spotted by US Navy reconnaissance aircraft, which deployed two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers and eight destroyers (Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan) to meet them when they enter “Ironbottom Sound”. At 01:24, 13 November, Hiei and Kirishima were detected from 28,000 yards (26 km) by USS Helena. His battleships were provided only HE shells and this caused a delay after they spotted the US fleet, to swap for AP shells. At 01:50, Hiei’s searchlights were switched on, and she first opened fire on the USS Atlanta. This was the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Hiei destroyed Atlanta’s bridge and killed Rear Admiral Norman Scott. Together with IJN Kirishima she badly damaged also two destroyers, but Hiei soon also became the focus of the US fleet. Her Hiei’s superstructure was targeted as set ablaze by 5-in guns at close range, notably by USS Laffey. Admiral Abe was wounded, and Captain Masakane Suzuki killed.

IJN Hiei underway in Tokyo Bay, 1942

IJN Kirishima evaded attack and meanwhile, crippled USS San Francisco, killing Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, while the latter disabled Hiei’s steering machinery. Dead in the water and burning fiercely, Hiei was an easy target and Abe ordered the remainder of the fleet to withdraw at 02:00. IJN Kirishima tried to launch a towing cable to Hiei but the flooding in her steering compartments jammed it circles. Repair teams struggled all night to unlock it, and at dawn on 14 November, she was bombed by a flight of B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. Still steaming, she made circles starboard at 5 knots until at 11:30, Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo-bombers approached and launched torpedoes, scoring two hits, and others followed plus dive-bomber attacks. Around midday, she was evacuated by her escorting destroyers, and scuttled by torpedoes in the evening. 188 crew members were lost woth the ship, and she was in effect the first IJN battleship lost during this war. Her wreck was rediscovered by Paul Allen’s exploration ship RV Petrel in 2019, under 3,000 feet (900 m) northwest of Savo Island. She probably suffered an underwater magazine explosion when sinking by the bow.

IJN Kirishima

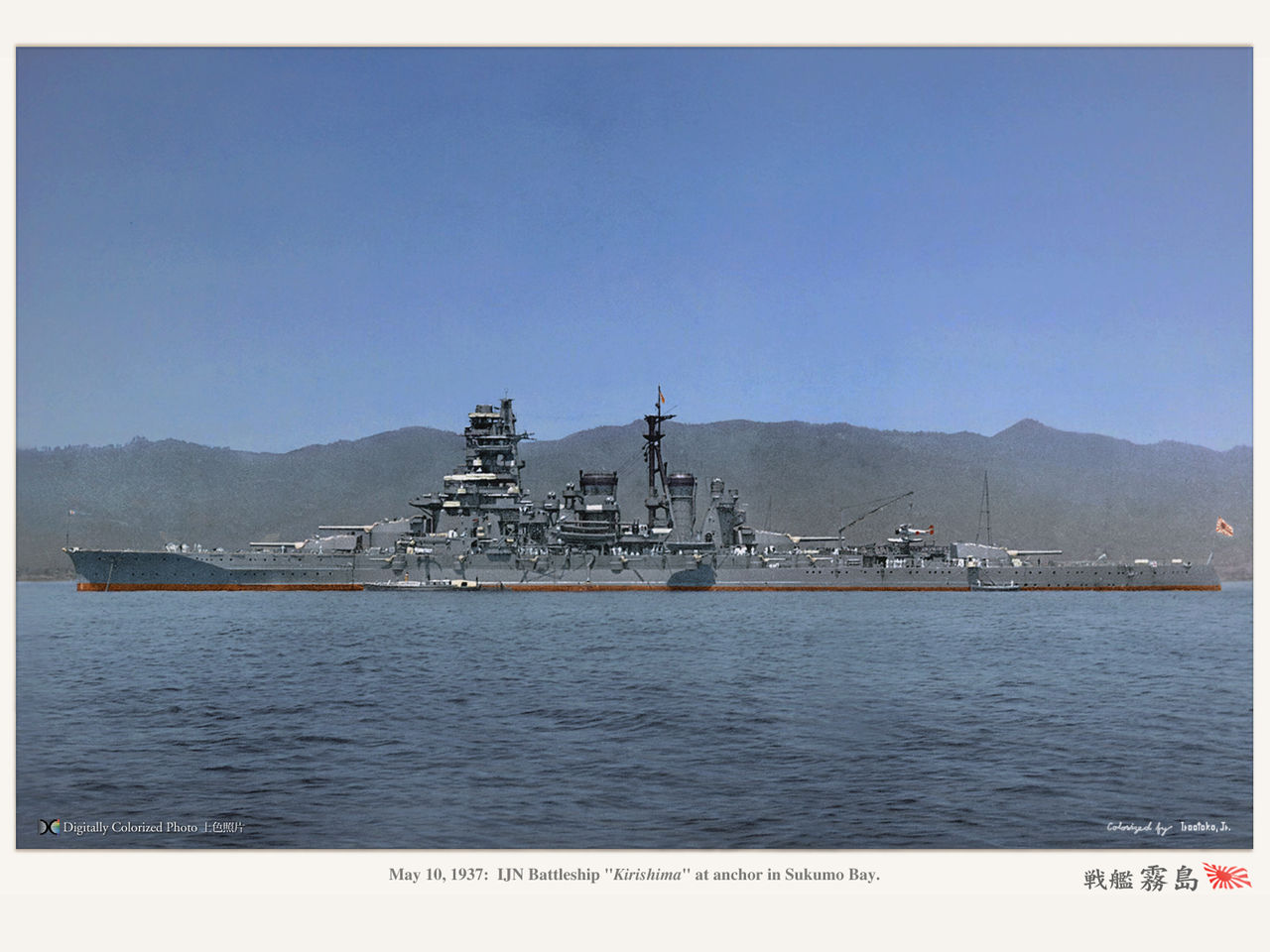

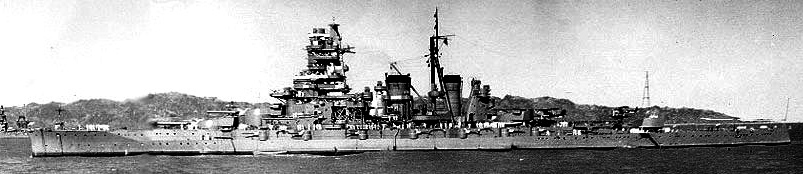

IJN Kirishima in 1937, colorized by Irootoko jr.

On 18 November 1934, Kirishima entered Sasebo’s drydock for her second reconstruction, along the same lines as her sister-ships, and she was ready by 8 June 1936. In August she departed Sasebo with Fuso for patrols in Chinese waters, starting off Amoy. In March 1937-April 1939, she alternated between home waters and escort for troopships to China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. By November 1938 IJN Kirishima became the command vessel of the Third Battleship Division, complete with specific bridge setting, and raised the mark of Rear Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. Next November 1939, she was in reserve for drydock fittings, additional armor on the main turrets faces, and barbettes. Her service records are limited for the period 1940-1941. On 11 November 1941 however, at the eve of the Pearl Harbor attack, Kirishima was again outfitted for the expected hostilities. She retained her role as flagship of the third Battleship Division and on the 26, she departed Hitokappu Bay (Kurile Islands) with Hiei and six Japanese fast carriers of the Kido Butai for the famous attack on 7 December 1941. She was back in home waters afterwards.

IJN Kirishima off Amoy, China, 1938

On 8 January 1942, IJN Kirishima departed for the Truk Naval Base, in full construction in the Caroline Islands. She still escorted the Carrier Strike Force, providing escort for the invasion of New Britain (17 January). She made another sorte after the attack of the Marshall and Gilbert Islands and from March 1942, was included as cover force off Java and the conquest of the Dutch East Indies, where Kirishima, with assistance, sunk by gunfire the immobilized destroyer USS Edsall. In April 1942, she was part of the task force attacking several objectives in the Indian Ocean. Back in Japan, she was drydocked and received additional 25 mm AA twin mounts. In June 1942, she was part of the Carrier Strike Force during the Battle of Midway (Admiral Nagumo) with IJN Haruna. In August 1942 she left Japan for the Solomon Islands with Hiei and three carriers, cruisers and destroyers, to repel the US invasion of Guadalcanal. She covered the CVs during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, during which Ryūjō was sunk, before heading for Truk Naval Base. She was also present at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands with Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe’s Vanguard Force and attacked by dive-bombers on 26 October, without hits.

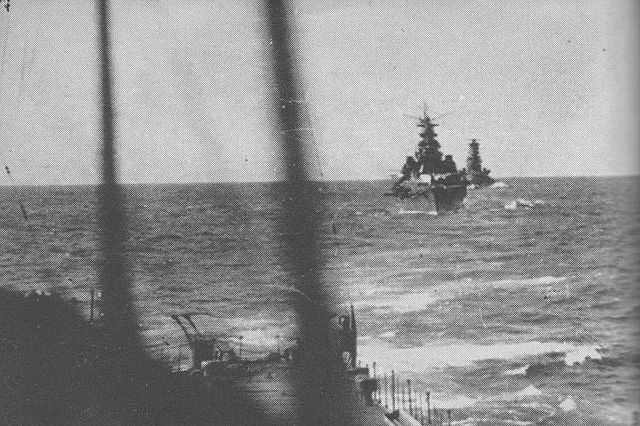

Kondo’s bombardment force heads towards Guadalcanal during the day on 14 November. Photographed from the heavy cruiser Atago, the heavy cruiser Takao is followed by the battleship Kirishima.

On 10 November 1942, she departed Truk with Hiei and eleven destroyers to shell American positions on Guadalcanal, preparing a Japanese reinforcement. They were spotted in advance, and met Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan force at the Ironbottom Sound. The night battle occured on 13 November (First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal) during which IJN Kirishima shelled and hit USS Helena and USS San Francisco. However Hiei was crippled in return, and Kirishima tried to tow her, before realizing she would not steer anywhere. She left the area with surviving destroyers northwards. On the evening of 13 November IJN Kirishima was joined by the Fourth Cruiser Division. Admiral Nobutake Kondō planned to return to Ironbottom Sound and in the early morning of 14 November, were preceded by three Japanese heavy cruisers, shelling Guadalcanal (the “tokyo night express”).

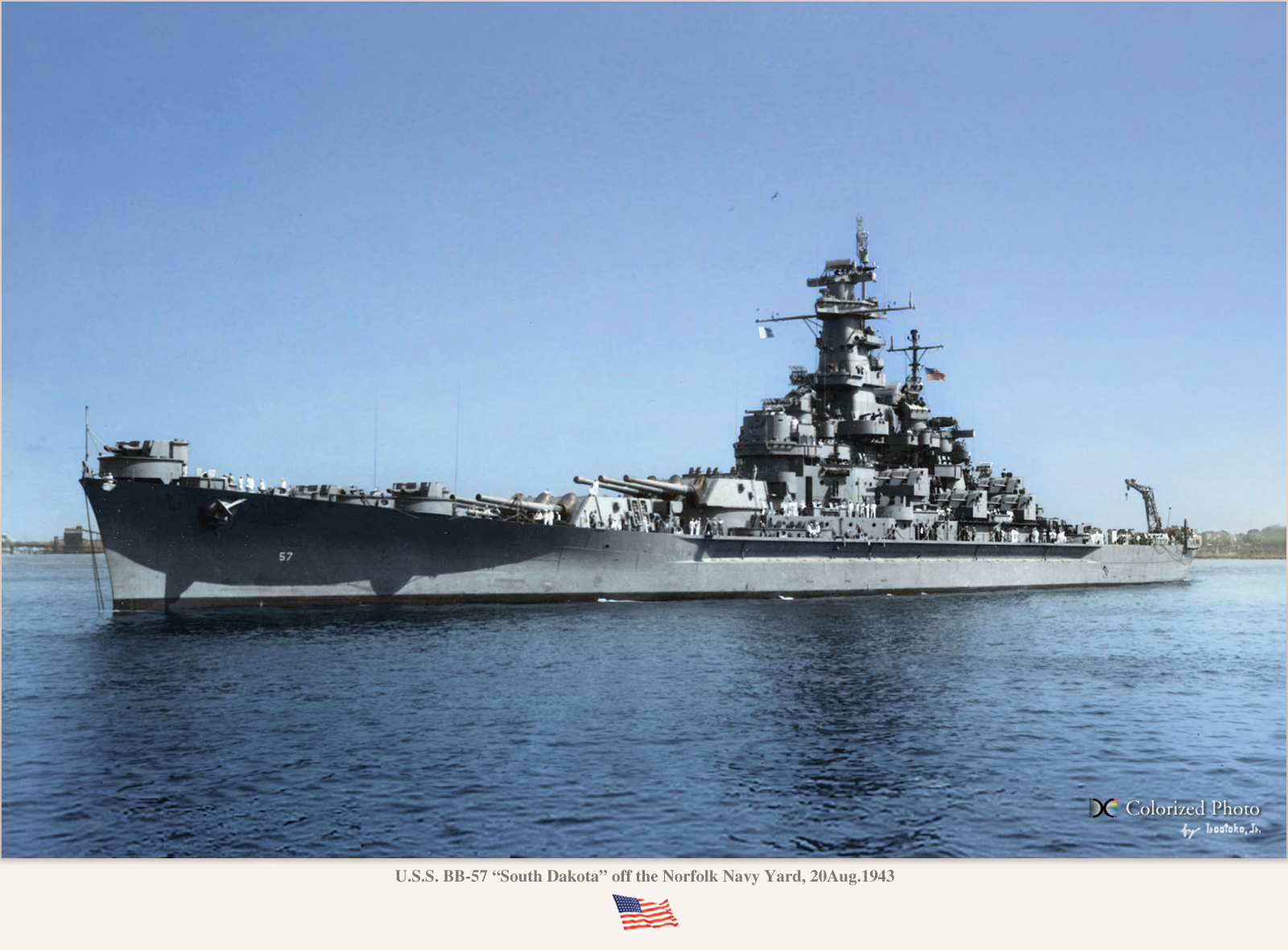

The Battleship USS South Dakota in 1943 (colorized by Irootoko jr). She was badly damaged by Kirishima and Hiei.

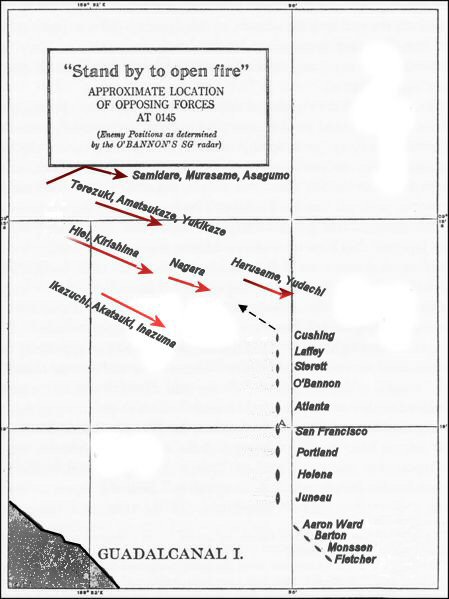

Admiral William Halsey managed to reinforce its local force by the BBs USS South Dakota and Washington. Opposing fleets made contact on 14 November, 23:01. Gunfire started, destroyers closed in for an exchange of and torpedoes leaving four USN destroyers badly damaged, three sank later, while on the other side, the destroyer IJN Ayanami was targeted by USS Washington and South Dakota and almost obliterated. When capital ships came into range, Kirishima and the heavy cruiser Atago switched on their searchlights, illuminating USS South Dakota. Kondō’s battleline then opened a withering, concentrated fire and Kirishima quickly scored hits on the US Battleship, withing her first three main guns salvos. Shells failed to penetrate her armor but her secondary battery knocked out the superstructure, disabling her fire control and communication system. At 23:40 USS South Dakota became practically blind and impotent: She had a general electrical meltdown, no radar, radios and inoperative gun batteries.

Position of both fleets approx. 1:45 AM on 14 November 1942.

Meanwhile, USS Washington still undetected at this point but following the action by radar, found an optimal spot and opened fire at midnight on IJN Kirishima, from only 5,800 yards (5,300 m). Her massive 16-inch/45-caliber gun penetrating Kirishima’s armor at optimal angle and the Japanese battleship was hit by -at least- 9 main rounds, and around 17 5-in shell. One penetrated her forward main ammunition magazines, which were promptly were flooded. But the blast also destroyed hydraulic pumps, jammed her aft 14-inch turrets. The steering room was also hit, while her superstructure was soon ungulfed in flames. Flooding became soon unontrollable and she listed to 18 degree to starboard. IJN Nagara attempted to tow her afterwards, but it appeared soon that she was too badly damaged to be moved anywhere. Surviving Japanese destroyers evacuated Captain Iwabuchi and the surviving crewmen. IJN Kirishima sank at 03:25, on 15 November 1942, carrying with her 212 crewmen. Her wreck was discovered by Robert Ballard 1992, showing her hull upside down, her bow section missing, due to a magazine explosion. This made IJN Kirishima the only Japanese battleship of World War II sunk in classic surface action by an enemy battleship.

USS Washington, winner of her duel with IJN Kirishima, opening fire at the early hours of November 1942

IJN Haruna

On 1 August 1933, IJN Haruna was in drydock at Kure Naval Arsenal for her reconstruction, along the lines of her sister ships. On 28 October 1935 her new captain was Jisaburō Ozawa (future admiral) and on 1st June 1936, she was transferred to the Third Battleship Division, First Fleet. The next year was spent in extensive gunnery drills alternated with patrols off the Chinese coast, notably Tsingtao. On 7 July 1937 the second Sino-Japanese was started and she escorted troopships to mainland China. On 1st December 1937, she returned in reserve in Sasebo Naval arsenal, but was reactivated on 2 April 1940, transferred to Taiwan, then a “special service ship” from November 1940, and in early 1941 she was attached to the 3rd Battleship Division, First Fleet, at Hashirajima. She departed with Kongō on 29 November 1941 to constitute the Southern (Malay) Force (Vice-Admiral Nobutake Kondō). On 4 December 1941, they arrived off Southern Siam, Northern Malaya, to start operations on the 8. Force Z was soon eliminated and Haruna’s battlegroup returned to Indochina, making another sortieby mid-December, protecting a troop convoy to Malaya and later a landing at Lingayen Gulf. They left Cam Ranh Bay on 23 December for Taiwan. On 11 December 1941, the U.S. media reported a raid of American B-17s bady damaged IJN Haruna during the battle off Lingayen Gulf which was debunked later. Haruna was in fact miles away that day.

IJN Haruna underway in 1940

On 18 January 1942, Kondō arrived in the Palau Island, with his two fast battleships escorting two fast carriers. His order was to cover the invasion of Borneo and the Dutch East Indies. Haruna was detached alongside the heavy cruiser Maya, an the carriers Hiryū and Sōryū to take positions east of Mindanao on 18 February 1942. Then they were prepared for Operation J, the invasion of the Dutch East Indies. On 25 February, she provided cover for the main attacks on Java and shelled Christmas Island on 7 March 1942. She headed to Staring-baai for maintenance, resupply and rest of the crew. In April 1942, she escorted five fleet carriers for atacks in the Indian Ocean, notably Colombo (Ceylon). After failing to trap the remainder of the British Eastern Fleet their foce still was able to located and sink HMS Hermes. IJN Haruna was back in home waters by 23 April, drydocked until May 1942 for repairs, maintenance, refits and AA additions. On 29 May 1942 she was part of Nagumo’s carrier strike force during the Battle of Midway and on 4 June was attacked by waves of TBM Avengers, which all missed whie her crew managed to shot down five of them. On 5 June, she picked up survivors from the four sunken Japanese CVs and headed back to Japan. She stayed there until September 1942 for minor refits and on 6 September departed for Truk the new base of the Third Battleship Division. On 10 September she was part of the Second Fleet in action in the Solomon Islands, back on 20 September to Truk lagoon.

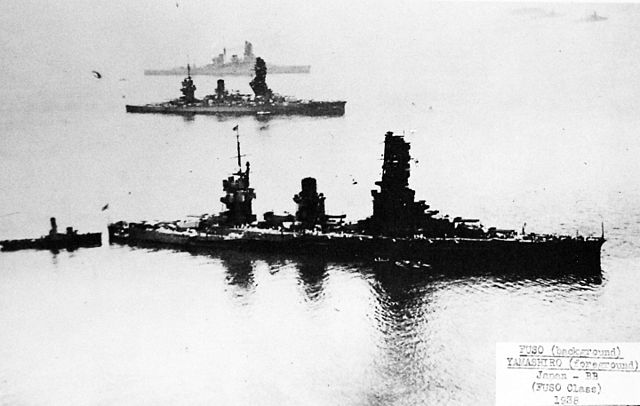

Fuso, Yamashiro and Haruna in 1938 off Amoy, China

Admiral Yamamoto sent Haruna and Kongō to shell Henderson Field as a first step before Japanese reinforcements to Guadalcanal. On 13–14 October, they succeeded in a dramatic way, damaging the two main runways of the airfield, destroyed aviation fuel tanks, incapacitated 48 aircraft (on 90), killing 41 men and wounding many more in the process; This action allowed a faultless troop convoy one day after, but on 26 October 1942, both battleships were in action at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. Haruna was spotted and attacked by a PBY Catalina, a near-miss. In mid-November she provided distant cover agains for attacks on Henderson Field and more landings at Guadalcanal. On 15 November 1942, her sister ships Hiei and Kirishima had been lost in the two Naval Battles of Guadalcanal, and the Third Battleship Division was back to Truk. Action would start again in 1943.

IJN Haruna by late January 1943 was ordered to take part of the “Operation Ke”, a diversion to cover another “tokyo Night Express” (a destroyer convoy sent to pick up this time evacuated soldiers). On 20 February 1943, the Third Battleship Division headed for home, at Kure Naval Base. Until 31 March 1943, IJN Haruna was in drydock for upgrades of AA, radar, and armor. On 17 May 1943, she made a sortie with IJN Musashi (Third Battleship Division) spotted by USS Sawfish, reinforced at Yokosuka, but disbanded when news came that Attu fell. During the summer of 1943, IJN Haruna was again refitted at Yokosuka and on 18 September 1943, she left Truk in response to raids on the Brown Islands (Micronesia), missing the US force there, and headed back to base. On 17 October 1943, she was part of a large force of five battleships, three CVs, 11 cruisers and many destroyers bound this time for Wake Island. No contact was made. Haruna departed Truk on 16 December 1943 for Sasebo, for more refits and training.

On 25 January 1944, Captain Kazu Shigenaga took command of the Battleship which departed Kure on 8 March 1944 for Lingga. The 3rd division remained there for training until 11 May 1944 when Admiral Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet headed for Tawi-Tawi, joined by Kurita’s “Force C” in order to defend the Mariana Islands. Haruna was spotted by USN aviation when escorting the carriers at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and diver bombers scored to two 500 lb (230 kg) AP bombs hits on 20 June 1944. Four days later she was in Kure for repairs, and returned to lingga on August 1944. By October 1944, she departed for “Operation Sho-1”, and the 24, she took near misses at the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea. On 25 October at Samar, she engaged TAFFY 3 escort carriers and destroyers, managing to hit or near miss two of these Jeep Carriers while dodging torpedoes from vigorous destroyers attacks. Admiral Kurita withdrawn his forced, and Haruna sailed to Brunei, and then Lingga where she was repaired. On 22 November 1944, she ran aground on a coral reef near Lingga so she had to be sent to Saseb for drydock repairs. On 2 December 1944, she evaded torpedoes from an unknwon USN submarines during a transfer and on 9 December, was ambushed, as the rest of her task force by three submarines: USS Sea Devil, Plaice, Redfish, which torpedoed Junyō and several destroyers but Haruna was not hit. She was in Sasebo and from there moved to Kure for repairs, upgrades and maintenance. In early 1945, she was the last surviving battleship of the Kongo class and one of the last IJN battleships still in service.

Kure under attack in July 1945

On 1st January 1945 however, IJN Haruna left the third Battleship Division for the First Battleship Division, Second Fleet. On 10 February, she was effected as a local defence ships -due to fuel shortages- of the Kure Naval District. On 19 March 1945, USN carrier aircraft started to launch massive raids on the Japanese coast, targeting ports and arsenals, and looking for the remaining IJN capital ships. Kure would be the object of many of such attacks. Despite its oint defence by veteran pilots and fighter instructors on the excellent Kawanishi N1K-J “Shiden” (“George”) fighters of the Navy led by Minoru Genda, they were just submerged by the inferior but more numerous F6F Hellcat fighters escoting dive bomber and TBs. Haruna during this first attack only sustained light damage, a near-miss on the starboard side. On 24 July 1945, TF 38 launched almost daily raids on Kure: Hyūga was sunk, and Haruna was hit by a bomb, causing light damage. 4 days later she became the main target, taking eight bomb hits. This time, flooding was uncontrollable an she sank at her moorings at 16:15 on 28 july, loosing in the process 65 officers and sailors. Her wreck was raised in 1946 to be broken up. Amazingly enough, she was the last IJN battleship sank in WW2, and the last in Asia for that matter. IJN Nagato survived only to be sent into a fleet assembled for a nuclear test in July 1946. The entire Kongo class with her made full circle: The first and last IJN batteships sank during that war, and the only sank in a classic duel between battleships in the Pacific.

First Published 2017/04/03

Sources/Read more

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kong%C5%8D-class_battlecruiser

fr.naval-encyclopedia.com/2e-guerre-mondiale/nihhon-kaigun.php#cuir

combinedfleet.com/haruna.htm

combinedfleet.com/kongo.htm

combinedfleet.com/Kirishima.htm

combinedfleet.com/hiei2.htm

combinedfleet.com/ships/kongo

combinedfleet.com/eclipkong.html

//www.navygeneralboard.com/kongo-class/

//ww2db.com/ship_spec.php?ship_id=455

//penandswordbooks.com/distributed-publishers/seaforth-publishing/kongo-class-battlecruisers.html

//www.navypedia.org/ships/japan/jap_bb_kongo.htm

//www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/japan/kongo-bb.htm

Videos:

Books:

Boyle, David (1998). World War II in Photographs. Rebo Productions.

Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers, 1905–1970. Doubleday.

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Naval Institute Press.

Chihaya, Masataka & Abe, Yasuo (1971). IJN Kongo Battleship 1912–1944. Warship Profile. 12 Profile Publications.

Evans, David C. & Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Naval Institute Press.

Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Naval Institute Press.

Jackson, Robert (editor) (2008). 101 Great Warships. London. Amber Books.

Jackson, Robert (2000). The World’s Great Battleships. Brown Books.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Naval Institute.

Lengerer, Hans (2012). “The Battlecruisers of the Kongô Class”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2012. London: Conway.

Lengerer, Hans & Ahlberg, Lars (2019). Capital Ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1868–1945. Despot Infinitus.

McCurtie, Francis (1989) [1945]. Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War II. Bracken Books.

Moore, John (1990) [1919]. Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War I. Studio Editions.

Parshall, Jonathan & Tully, Anthony (2007). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Potomac Books.

Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. Galahad Books.

Rohwer, Jurgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Naval Institute Press.

Sandler, Stanley (2004). Battleships: An Illustrated History of their Impact. Weapons and Warfare. ABC Clio.

Schom, Alan (2004). The Eagle and the Rising Sun: The Japanese-American War, 1941–1943. Norton & Company.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Skulski, Janusz (1998). The Battleship Fusō: Anatomy of a Ship. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Steinberg, Rafael (1980) Return to the Philippines. Time-Life Books Inc.

Stille, Mark (2008). Imperial Japanese Navy Battleships 1941–1945. Osprey Publishing.

Swanston, Alexander & Swanston, Malcolm (2007). The Historical Atlas of World War II. LCartographica Press Ltd.

Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Naval Institute Press.

Willmott, H.P. & Keegan, John [1999] (2002). The Second World War in the Far East. Smithsonian Books.

Wiper, Steve (2001). Imperial Japanese Navy Kongo Class Battleships. Warship Pictorial.

A colorized closeup of the Kirishima’s pagoda by Irootoko Jr.

Model Kits Corner

On Scalemates database

Most of these ships had been treated in 1/700 and 1/350 notably by Hasegawa, Tamiya and Aoshima

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

AWESOME WEBSITE!HUZZAH!