Rule Britannia, still

Rule Britannia, stillIn 1939, the British Navy was still the most powerful in the world, with the largest worldwide network of fortified bases and arsenals. An imperial fleet, planetary par excellence. The military budget allocated to aviation, and especially to the army, was tiny in comparison.

The Royal Navy in 1940, contemporary perspective drawing.

But the insular position and security of the sea routes of the empire imposed this state of affairs. Though officially “the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland”, it was always spoken in the newspapers of “British Empire”. A fleet of unparalleled importance confirmed by the de facto position and authority of the first Lord of the Sea with the Prime Minister. In September 1939, it was Sir Winston Churchill who occupied this post, the providential man, who had played a comparable role during the Great War.

Articles published and awaited

WW2 RN Battleships

Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | Nelson class | King Georges V class | HMS Vanguard | Lion classWW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classWW2 British RN Cruisers

C class | Hawkins | D class | E class | HMS Adventure | County | York | Leander | Surrey | Arethusa | Perth | Town | Dido | Abdiel | Fiji (Crown Colony) | Bellona | Swiftsure | TigerWW2 British Destroyers:

V class | W class | W mod class | Shakespeare class (1917) | Scott class (1818) | A/B class (1926) | C/D class (1931) | E/F class (1933) | G/H class (1935) | I class (1936) | Tribal class (1937) | J/K/N class (1938) | L/M class (1940) | Hunt class DE (1939) | O/P class (1942) | Q/R class (1942) | S/T/U/V/W class (1942) | Z/ca class (1943) | Ch/Co/Cr class (1944) | Battle class (1945) | Weapon class (1945)Hunt Type I class DE (1939) | Hunt Type I class DE (1939) | Hunt Type I class DE (1939) | Hunt Type I class DE (1939) | Captain class DE (1941)

WW2 British Submersibles:

X1 | Odin | Parthian | Rainbow | Thames | Swordfish | Porpoise/Grampus | Shark | U class | T class | S class | U class 1940 SH | P611 class | V class (U 1941/42 LH) | X-Craft | A class- A/B class destroyers (1929)

- Abdiel class minelayers (1940)

- Admiralty type (Scott class) flotilla leaders (1917)

- Ameer (Ruler) class Aircraft Carriers

- Amphion class submersibles (1945)

- Arethusa class cruisers (1934)

- Attacker class Escort Aircraft Carriers (1941)

- Avenger class Escort Aircraft Carriers (1943)

- Bellona class cruisers

- British C class cruisers (1914-1922)

- British Cruisers of ww2

- C/D class destroyers (1931)

- Castle class corvettes (1943)

- Colossus class light fleet Aircraft Carriers (1944)

- County class cruisers

- Courageous class aircraft carriers (1928)

- Crown Colony class cruisers (1936)

- Dido class AA cruisers (1939)

- E/F class Destroyer

- Enterprise class cruisers

- Flower class Corvettes (1940)

- G/H class destroyer

- Grampus class submersibles (1932-36)

- Hawkins class cruisers (1920)

- HMS Activity (1942)

- HMS Adventure (1923)

- HMS Archer (D78)

- HMS Argus (1917)

- HMS Ark Royal (1937)

- HMS Audacity (1941)

- HMS Dreadnought (1960)

- HMS Eagle (1918)

- HMS Furious (1917)

- HMS Hermes (1919)

- HMS Hood

- HMS Pretoria Castle (1938)

- HMS Unicorn (1941)

- HMS Vanguard (1944)

- HMS X1 (1923)

- Hunt class Destroyer Escort (Type 1)

- I class destroyer

- Illustrious class aircraft carriers (1939)

- Implacable class fleet aircraft carriers (1942)

- J- K- N- class destroyer

- King George V class Battleships (1939)

- Landing Craft, Tank (LCT) (1940-1945)

- Leander class cruisers (1931)

- Loch class Frigates (1942)

- Merchant Aircraft Carriers (1942)

- N3 (St Andrews) class Battleships (1918)

- Nairana class escort aircraft carriers (1943)

- Nelson class battleships (1925)

- Odin class submersibles (1926)

- Parthian Class submersibles (1929)

- Perth class cruisers (1934)

- Queen Elizabeth class Battleships (1913)

- Rainbow class submersibles (1930)

- Renown class battlecruisers (1916)

- Revenge class Battleships (1915)

- River (Thames) class submersibles (1932)

- River class Frigates (1942)

- S class submersibles (group III) 1939-43 Programmes

- Shark (Group II) class submersibles (1934)

- Swiftsure class cruisers (1943)

- Swordfish (S) class submersibles (1931)

- Thornycroft Type (Shakespeare class) Destroyer Leaders (1917)

- Tiger class cruisers (1945)

- Town class cruisers (1936)

- Tribal class Destroyer (1937)

- Triton (T) class Submersibles (1937)

- U class submarine (1937)

- WW2 British Aircraft Carriers

- WW2 British Amphibious Ships and Landing Crafts

- WW2 British Battleships

- WW2 British Destroyers

- WW2 British submarines

- York class cruisers

Lion class

Surrey class cruisers (project)

Malta class (project)

V class (1917)

S class (1918)

W class (1918)

I class (1936)

Tribal class (1937)

J/K/N class (1938)

Hunt class DE (1939)

L/M class (1940)

O/P class (1942)

Q/R class (1942)

S/T/U//V/W class (1942)

Z/ca class (1943)

Ch/Co/Cr class (1944)

Battle class (1945)

Weapon class (1945)

X-Craft midget (1942)

LSI(L) class

LSI(M/S) class

LSI(H) class

LSS class

LSG class

LSC class

Boxer class LST

LST(2) class

LST(3) class

LSH(L) class

LSF classes (all)

LCI(S) class

LCS(L2) class

LCT(I) class

LCT(2) class

LCT(R) class

LCT(3) class

LCT(4) class

LCT(8) class

LCT(4) class

LCG(L)(4) class

LCG(M)(1) class

LCA

LCP

LCM

WW2 British MTB/gunboats

WW2 British MTBs

MTB-1 class (1936)

MTB-24 class (1939)

MTB-41 class (1940)

MTB-424 class (1944)

MTB-601 class (1942)

MA/SB class (1938)

MTB-412 class (1942)

MGB 6 class (1939)

MGB-47 class (1940)

MGB 321 (1941)

MGB 501 class (1942)

MGB 511 class (1944)

MGB 601 class (1942)

MGB 2001 class (1943)

WW2 British Gunboats

Denny class (1941)

Fairmile A (1940)

Fairmile B (1940)

HDML class (1940)

WW2 British Sloops

Bridgewater class (2090)

Hastings class (1930)

Shoreham class (1930)

Grimsby class (1934)

Bittern class (1937)

Egret class (1938)

Black Swan class (1939)

Loch class (1944)

Bay class (1944)

WW2 British Corvettes

Kingfisher class (1935)

Shearwater class (1939)

WW2 British Misc.

Roberts class monitors (1941)

Halcyon class minesweepers (1933)

Bangor class minesweepers (1940)

Bathurst class minesweepers (1940)

Algerine class minesweepers (1941)

Motor Minesweepers (1937)

ww2 British ASW trawlers

Basset class trawlers (1935)

Tree class trawlers (1939)

HMS Albatross seaplane carrier

WW2 British river gunboats

HMS Guardian netlayer

HMS Protector netlayer

HMS Plover coastal mines.

Medway class sub depot ships

HMS Resource fleet repair

HMS Woolwhich DD depot ship

HMS Tyne DD depot ship

Maidstone class sub depot ships

HmS Adamant sub depot ship

Athene class aircraft transport

British ww2 AMCs

British ww2 OBVs

British ww2 ABVs

British ww2 Convoy Escorts

British ww2 APVs

British ww2 SSVs

British ww2 SGAVs

British ww2 Auxiliary Mines.

British ww2 CAAAVs

British ww2 Paddle Mines.

British ww2 MDVs

British ww2 Auxiliary Minelayers

British ww2 armed yachts

- Blackburn B-25 Roc (1938)

- Blackburn T.5 Ripon (1926)

- Fairey Albacore

- Fairey Barracuda (1942)

- Fairey Firefly

- Fairey Fulmar (1940)

- Fairey IIIF (1930)

- Fairey Seafox (1936)

- Fairey Seal (1930)

- Fairey Swordfish

- Gloster Sea Gladiator (1938)

- Short Sunderland (1937)

- Supermarine Seafire (1942)

- Supermarine Seagull (1921)

- Supermarine Walrus (1936)

Interwar history of the Royal Navy

Washington treaty

The Royal Navy had its status confirmed, but at the same time capped by the Treaty of Washington (1923), which defined its tonnage limit (tied with the US Navy), 500,000 tons for first- At the time the battleships. As it did not cease its shipbuilding during the Great War, its forces included a large number of cruisers, line ships, and even destroyers dating from the Great War or the Pre-Washington (1919-22). It was only for liner ships that the 10-year moratorium was required. The only exception to the treaty, even though very precisely designated, were the two battleships of the Nelson class (1925) whose construction was too advanced for demolition.

The Home fleet patrolling the North Atlantic, at the time of the mutiny of Invergordon (Sept. 1931). The government had proposed to lower the salaries of seamen by 25%. After a generalized mutiny, the decline was limited to 10%. (wikipedia)

The battle-cruisers had seen their conversion into an aircraft carrier, and only three survivors of that age remained in service as such: The Hood (1920), pride of the British navy, and the Repulse and Renown a little older ( 1917), but fast and with formidable armament. The battle cruisers of David Beatty engaged during the Battle of Jutland (May 1916) had shown such poor performances that they had been discredited by a large part of the Admiralty.

Nevertheless, the concept of a considerable artillery with a high speed remained topical. And indeed the new generation of battleships called “rapids” was on the drawing boards as early as 1918. The great majority of them were never finished or converted into aircraft carriers. It was not until the second half of the thirties that the fruits of this naval thought came to fruition in practice.

HMS Hood and crew

Recomposition of the 1930s

The composition of the British fleet still depended largely in 1939 on two classes of battleships dating from before and during the Great War, five from the Queen Elizabeth class (1913) and five from the Revenge class (1916). Most will simply be modernized, but others will be completely redesigned (Warspite, Queen Elisabeth, Valiant). In addition to these two ships, the Royal Navy had the largest fleet of aircraft-carriers, with the largest number of vessels on board.

Near by Japan. This weapon, Great Britain, had been the pioneer, implementing the first aircraft carrier operating in 1918, derived from the battle cruiser Furious. Its numerous attempts afterwards, reconstructions and new buildings in 1936 and later in the war, even more massive, were not to be eclipsed by the extraordinary capacity of American industry. War saw the birth of beside classic solutions the most fanciful projects of flying aircraft carriers, “floating military aerodromes” and even giant aircraft carriers made of a compacted ice comparable to concrete…

Bases and harbours

The British navy had the role of defending the metropolis, which it had been doing since the “inviolable harbor” of Scapa Flow in the Orkneys (north of Scotland), a place of humiliation of the hochseeflotte and its sinking On a large scale in 1919. Moreover, the roadstead had nothing inviolable, as will be proved later by the U47 by Gunther Prien… This “myth” about the Royal Navy, also anchored in the heart of its Compatriots than the maginot line for the French, would fall like the Hood … The fleet also had advanced bases and arsenals at Rosyth and Portsmouth. Its presence in the Mediterranean, although assured mainly by tacit agreement, by its French ally, was based in Gibraltar, closing access to the Atlantic, and Alexandria, guarding the vital Suez Canal. Finally, two other central locks controlled the roads from west to east, Malta and Rhodes.

Scapa Flow, with the Hochseeflotte at anchor, 1918.

The British navy was also present in south-east Asia, notably thanks to the Singapore base, the “gibraltar of the Indian Ocean”, whose coastal fortifications and the large protected harbor that could accommodate a large fleet, (Jungle) on the land side ensured theoretical immunity. Here again, a myth that the Japanese will fall and at the same time inflict on the empire the worst defeat in its history. More to the east there was Hong Kong, with its concession for 99 years. Once again, the Japanese will de facto place the city under siege in December 1941.

4.7in QF MkXII masked twin gun, HMS Javelin, 1940

The last British refuges will be in Oceania (Australia and New Zealand) and in India they will remain, in spite of the formidable Japanese advance, in the hands of the allies and will allow The US navy to have a rear base of reconquest, and later to the Royal Navy to return. British naval aviation, which had given excellent results (the Royal naval air service) was assimilated in 1918 to the Royal Flying corps, giving birth to the Royal Air Force. However, in 1937, in front of the increasing number of aircraft carriers and the real and differentiated needs of the Navy, a new naval aviation corps was created: The Royal Fleet Air Arm. In 1939, Great Britain had the largest naval air force in the world, closely followed by Japan.

The HMS Hood, pride of the British Navy. The most powerful ship in the world, the fastest ship of the line and the best armed one, at its launch and for twenty years, it was nicknamed “mighty hood”. The limitations of the Washington Treaty and the crisis of 1929 passed, but remained the pride of the navy, embodied by this great building. Never modernized significantly, it will be a mistake that will cost dear Admiralty in May 1941. (wikimedia)

The 1935 agreement with Germany

In 1935, the London Naval Treaty redefined (and relaxed) the rise of some fleets such as the Kriegsmarine and the Japanese Navy and broke the Washington Treaty, albeit to conform with the latter, the super-dreadnoughts of the King George V class built on the eve of the war were under-equipped with low-caliber main artillery. In fact, the essential part of the home fleet was assured by the ten venerable battleships of the great war, whose potential remained formidable, and they showed it amply in the Mediterranean.

HMS Cossack

Naval innovations

In 1937, a new engineering department attached to the Royal Navy was working to make aircraft that had remained prototypes practicable. They were going to give the first radars and sonars (ASDIC and hydrophones), Huff-Duff Localization trigonometric) of the fleet, and thus a decisive advantage at the beginning of the war. Outside Germany, only Germany was at the level, followed by the US Navy.

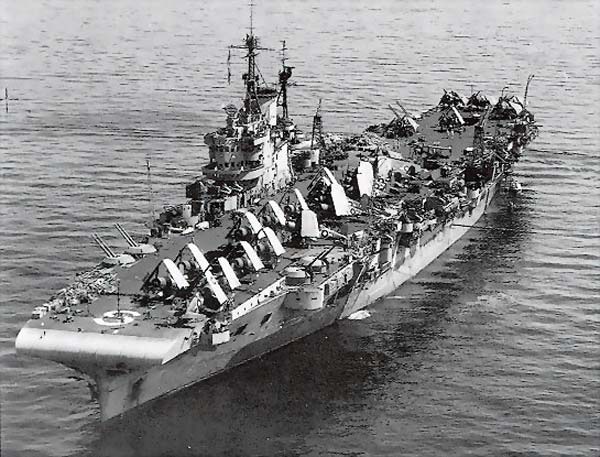

HMS Victorious in ww2 (src naval-history.net)

As we have seen, the relative shortage of battleships was compensated by the modernization or even overhaul of these vessels (boilers and engine equipment, turbines, telemetry, secondary artillery, range and incidence of new main rooms, radio, And in particular AA artillery), compounded by a large number of new cruisers, whose backbone was represented by the large buildings of the “County” class, assisted by a myriad of light cruisers. In accordance with the Treaty of Washington, cruisers had a main artillery of 203 mm (eight pieces for example on the County, six on the Exeter), and light ship with 152 mm pieces (from six to nine).

HMS Rodney after refitting at Liverpool

In 1935, a new tactical trend was to give the cruisers a lighter weaponry, but in greater numbers, which gave the heavy cruisers of the “Town” class, surprisingly armed with 12 pieces of 152 mm. Thereafter, no British cruiser carried more 203 mm artillery, despite their large tonnage. In the oldest cruisers, they wore unique parts under masks, in an outmoded configuration, such as the Cavendish with their 190 mm pieces, the Enterprise and a cohort of lighter vessels ranging in size from 3,000 to 5,000 tons, armed in general with 5 pieces of 152 mm. Most of these ships were re-armed with DCA for escort during the war.

Destroyers of the Royal Navy

The number of destroyers was considerable, as there were about five destroyers for each cruiser in proportion. Their design was derived directly from the 1920s-1919 tye “leader” buildings and there was little or no change in armaments other than the modernization of the carriages, the scope and mechanisms for greater As well as more sophisticated rangefinders, and on the eve of the war, the huff-duff, a simple radio antenna designed to track the position of submersibles transmitting shortwaves. Electronic sonar (asdic) was also adopted around 1938 and systematized alongside classical hull hydrophones. We also saw the anti-submarine grenades. Typically, the “leaders” had 5 pieces of 130 mm, and the “standards” lighter of 500 tons or more, 4 pieces of 106 mm. The space between the torpedo tubes was frequently used to install AA guns, an intermediate-caliber piece with a long range, but low firepower and low cadence, and then the 40 mm Bofors quadruple shafts, which were nicknamed Later “pom-pom” and reloaded by cartridges, requiring a total of five people. Oerlikon (American) 20-gauge pieces of small caliber were manufactured under license.

HMS devonshire, a standard “County” class cruiser in peacetime livery.

British Submarines of WW2

In the case of submarines, the Royal Navy had fewer vessels than France, Germany or Italy, because it had no use for this type of A classic fleet of overwhelming proportions. However, the utility of the submersibles having been demonstrated in a modern fleet for a variety of missions, several classes of oceanic submersibles were built, mainly from the “rivers” class beginning in 1922. They recognized themselves as their ” Artillery under a mask attached to the kiosk, to their hemispherical gangway with portholes, to their raised prow to improve their outfit in heavy weather. These were long-cruising vessels, equipped with powerful diesel engines, made to patrol the Atlantic and remote bases (Indian Ocean in particular). It was only shortly before the war that new classes of lighter submersibles were born, and their production grew.

MTBs and light ships

On the other hand, the British had renounced the torpedo boats since 1914, but had taken an interest in the performances of the Italian MAS during the Great War, which had given new life to the concept of the torpedo boat, in the form of light and very fast stars. Although it was embryonic (because of its lack of usefulness a priori in times of peace), the force of torpedo boats would quickly develop and find its place during the war. Then, in terms of submarine warfare, the destroyers were supposed to carry the bulk of the effort as scavengers. There were only a few lighter ships capable of performing this role (again unnecessary in time of peace), if not a handful of Sloops. Finally, the Royal Navy, like the US Navy, had understood the interest of an offshore support, and had built workshops and workshop ships that proved valuable thereafter.

The Royal Navy in the interwar, HMS Nelson

The Royal Navy in 1939:

15 Battleships

– 2 Renown Class Battle Cruisers: Last battle cruisers of the Great War (the Furious followed but was converted), active throughout the interwar period, and in active service In 1939. Both were modernized, but the Renown was later completely rebuilt.

– 1 HMS Hood (Battle cruiser): This superstar, was the most powerful warship of the Royal Navy when it came into service in 1920, and had a brilliant career in peacetime. But behind symbolism, the Hood never had the modernization it deserved.

– 5 Queen Elisabeth Class: Launched 1913-14, commissioned during the Great War, first dreadnoughts with 381 mm pieces, and first with oil boilers instead of coal. Three (Valiant, Queen Elisabeth, Warspite) completely rebuilt, the others modernized.

– 5 Revenge class: Launched 1915-16, modernized, sometimes in two periods over twenty years.

– 2 Nelson Class (1925).

– King George V: New series in completion (none in service yet).

Also to notice, although then partly demilitarized, was the Iron Duke, dating back to 1912, kept in operation as a gunnery training ship.

7 aircraft carriers

– HMS Furious: Originally from a battle cruiser with 457 mm pieces, they were first converted first (1918) and then totally converted (1922-25) into aircraft carriers.

– 2 Glorious class aircraft carriers: From the same concept, but smaller, they were reconverted and completely rebuilt in 1924-30.

– HMS Argus: Reconverted from a liner in 1918, it was still in service in 1939, used primarily for school and aircraft transport.

– HMS Eagle: Reconverted from a dreadnought (formerly Almirante Cochrane), he became an aircraft carrier after a reconversion in 1918-1920. Active in 1939

– HMS Hermes: The first aircraft carrier built as such in the world, the Hermes was only operational in 1924. It was active in 1939.

– HMS Ark Royal: Second purpose-built aircraft carrier, completed in 1938. By far the largest, spacious and performing of the type by 1939.

63 Cruisers

– 13 “County” heavy cruisers (1926-29): Actually these ships were three separate classes, but very close. They were the bulk of the force of heavy cruisers in the fleet.

– 2 class York heavy cruisers (1928-29): Smaller than the previous ones. The York differed a great deal from the Exeter to the extent that it was often assimilated to different “classes”.

– 10 class “Town” heavy cruisers (1936-1939): Armed exclusively of 6-in guns (152 mm), these ships were divided into three classes.

– 3 class Hawkins heavy cruisers (1917-1921): Only survivors of this class of cruisers equipped with parts under masks, configuration obsolete in 1939.

– 5 Leander class light cruisers (1931-34): Classic washington treaty light cruisers, armed with eight 6-in (152 mm).

– 3 Perth class light cruisers (1934): From a very close model, they were assigned or transferred at the beginning of the war to Australia.

– 4 Arethusa class light cruisers (1934-36): Reduced compared to the previous ones, they had only 6 pieces of 152 mm.

– 3 class Caledon (1916-17) light cruisers: Of obsolete configuration, they were modernized and quickly assigned to the escort.

– 5 class Ceres light cruisers (1917): Very close to the first, they were partially rebuilt as anti-aircraft cruisers.

– 5 Carlisle class light cruisers (1918-19): Same remark as above.

– 8 class Danae light cruisers (1918-19): Modernized and reconfigured as anti-aircraft cruisers and escort cruisers.

– 2 Enterprise class light cruisers (1919-1920): First equipped with a double turret of 152 mm, they had been modernized and were active in 1939.

184 Destroyers

It would take too long to detail all the classes of destroyers built since 1920 and those resulting from the Great War. In essence, these vessels had an almost identical configuration since the commissioning of the Shakespeare and Scott class fleet leaders in 1917-1920. At that time, the arming of these leaders consisted of 5 pieces of 120 mm, 3 pieces of DCA (75 mm and 40 mm) and six torpedo tubes of standard caliber (533 mm) in two axial and central benches. The V and W classes, which were significantly heavier than the previous classes of the R classes, had four 102 mm pieces and four torpedo tubes only, with 500 tonnes less.

The practice of having “leaders” and “standard” destroyers was not unique to the Royal Navy and lasted until 1930. After that, the tactics changed and the destroyers had reached a much higher standard: 1938, the J/K/N class constituting a clear advance, had a displacement of 2500 tons at full load (against 2000 for the leaders of 1918), 6 pieces of 120 mm in double carriages, 10 torpedo tubes in quintuple benches And a much more substantial DCA. As a result, destroyers from before 1920 were essentially converted as escort.

60 Submarines

Like in most navies, submersible construction was divided into two categories, the big oceanic and the coastal and medium range types. More economical, they were produced in mass during the war, on models defined in 1937 and 1942 (Class S and Class T). British submarines served mostly in the Mediterranean, attacking Italian shipping lines and supply convoys after the French defeat, and as submarine hunters, patrolling all areas subject to attack, both Italian units and rare U-Bootes (in the Mediterranean) and the gray wolves of the Atlantic. The great oceans, dear to operate and equipped with aging equipment, operated especially from distant stations.

The end of the war would have to wait until a new class of submarines destined for the Far East began to replace them, Class A. Most were finished after the war, modernized or refurbished, and served even in the seventies. In addition to patrolling and hunting for enemy submarines, the S and T classes were also used for stealth transports, to disembark or embark on liaison officers with the resistance or important characters (such as General Giraud, for example). The losses were nevertheless severe, sometimes as a result of misunderstandings by other submarines, escorts or Allied aviation.

These forces included 60 units in service in September 1939: 9 former H class (1916-17), 3 former oceanic class L (1918-19), HMS Oberon (1926), 3 Thames (1932-34), 6 Odin ), 2 Oxley (1928), 6 parthian (1929), 6 Grampus, HMS Porpoise, HMS Oberon, 4 light Swordfish (1933), 33 Class S (1942-44), 53 class T (1937-1945) Class U (1937-44).

123 Miscellaneous

Under this umbrella are minesweeper, sloops, frigates, torpedo boats and various supply vessels or squadron motherships. Concerning the “sloops”, this type of light vessel which could be likened to a gunboat was produced in limited series, both as an escort and in this role of ship of distant stations. They served as coastguards and control vessels in fishing areas during their civilian service. There were the Bridgewater (1928), Hastings (1930), Shoreham (1930) and Grismby (1933). In terms of minesweepers, the RN consisted of 21 ships class Halcyon (1934) and 4 Basset/Fundy (1938-delivered to the RCAN). Patrollers included units of the Kingfisher, Shearwater and Kil class.

Supporting vessels included the Medway, supply ships for submersibles (1928), the Resource (1929) and the Woolwich (1934- destroyer support), as well as the Maidstone submersible tankers (Two units with the Forth – 1938). As for MTBs, the RN built prototypes and 18 boats, starting in 1938 at Vosper Thornycroft, one of the future leaders of this market. The vast majority of the MTBs will be built during the conflict and used for a large variety of missions.

The Royal Navy in ww2

Undoubtedly, the Royal Navy played an essential role with the Royal Air Force in safeguarding the metropolis as well as the empire and its vital routes to its commercial resources. Three main and highly strategic routes were to be defended with all available means: The North Atlantic route, the link with Canada and the United States, which provided a considerable number of armaments (including many Ships) to Great Britain with the lend-lease agreement, and South America trade, especially providing food supplies, vital production for the metropolis, and to “the Indies”, passing through Egypt and the Suez Canal. Also the fleet was in 1939, scattered among many distant stations, though essentially, the Home Fleet remained based at the Firth of Forth (Scapa Flow).

HMS Warspite in the Indian Ocean, 1942.

First operations in the Atlantic (1939)

The first operations of the RN, shortly after the declaration of war, and as in 1914, was to carry, on the one hand, the hunt for German corsairs in the Atlantic (the three pocket battleships, their supply vessels and privateers) , And on the other hand on the protection of the zone of the great banks (North Sea), opposite the Strait of Denmark and to the English coasts. The danger was to come-and indeed it came-from the German submarines. A network of patrols was set up, and minefields were laid on certain strategic areas between the passages of the large benches. At first the U-Bootes carved out a beautiful chart, mainly cargo, before the system of convoys to be reorganized. The battleship Royal Oak (Revenge class) was thus sent from the bottom to the anchorage at Scapa Flow, by the U51 of the Commander Prien. He proved that the “sanctuary” in northern Scotland was not, and forced the RN to reinforce the patrols.

But an unexpected new perile appeared suddenly: The Luftwaffe launched an operation destined to anchor magnetic mines in areas of strong passage. In response, after the first losses, and the identification of the problem, the “demagnetization” of the civil and military ships was put in place. The first major success of the RN was the (indirect) destruction of the pocket battleship Graf Spee. The latter, thanks to his large coins, had wrecked Admiral Goodwood’s squadron (Exeter, Achilles, Ajax) before taking refuge in the Rio de la Plata, then Montevideo, and then being scuttled by a bluff Cleverly orchestrated by the British. His sister-ships, the Admiral Scheer and the Deutschland, renamed Lützow, did not have the same success, but their career led them until 1945. In October the system of convoys had been reconstituted and applied to the letter by The British ships, but mobilized a large number of destroyers. The War Room, the central operation of the Admiralty, was moved underground into new bomb-proof facilities. From there, this HQ managed on a giant map the available assets.

HMS Emerald (Enterprise class), one of the early interwar British Cruisers still in service.

Norwegian Campaign (March-May 1940)

Triggered by the Germans to secure very large iron stocks from narvik, it began in April 1940 (Operation Weserübung). In a short time, the Kriegsmarine landed troops that seized strategically important cities. The weak Norwegian Army defended itself, as it had been able, by surprise, against elite troops like the Gebirgsjäger. The Norwegian navy, with limited means, tried to stop the advance of the German ships in the Fjords, but it was the coastal batteries that played the most important role. The allies replied. France pressed for an intervention that would distance the German threat from its borders, an idea backed by Churchill. During the night of 15-16 February 1940, the Altmark (Graf Spee tanker), escorted by Norwegian torpedo boats in a fjord, was approached, without the Norwegians intervening, by a naval commando from destroyer HMS Cossak.

The incident provoked an official German protest, whose relations had deteriorated with Scandinavia in general, notably because of its pact with the USSR, at war with Finland. This event caused the Germans to fear the passage of Sweden and Norway, neutral on the side of the allies, and the plans of invasion were speeded up. The British Admiralty set up Operation Wilfred, designed to force transport vessels to navigate the territorial waters to better control them on Norwegian coasts and to hinder the movements of the Kriegsmarine, the R4 plan, to attack and Stavanger and Sola airfields, and the “Operation Royal Marine” consisting of mines on the Rhine. On 4 April the Admiralty dispatched a screen of 16 submersibles before alerting the Germans to the Skagerrak. Admiral Whithworth left Scapa Flow with the Renown and 12 destroyers to sail to the Vestfjord. Caught in a snowstorm, they missed the Germans.

After the detection of Gruppe 1, the RAF attempted an attack which was lost in the execrable time, which helped the Germans. The HMS Glowworm, a destroyer who accompanied the Renown, had diverted to recover a man who had fallen into the sea in heavy weather. When he returned to the Renown, he fell upon two German destroyers of the invasion plan. A cannonade ensued, and the Glowworm, severely touched, spurred the Hipper cruiser, before being destroyed. The Renown left the Vestfjord in search of him, and on his return northward he encountered the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau which he faced. His heavy pieces struck them, without wiping himself, and forced them to flee. After the invasion was completed (except in Oslo, Oscarborg’s battery put an end to this attempt by sinking the Blucher), the allies replied.

The Home Fleet concentrated its efforts on Bergen. Rear-Admiral Warburton-Lee, at the head of 6 destroyers, took his place in the Narotk Ofotfjord, and engaged five German destroyers escorting a convoy. Two other successes were credited to the RN, the Königsberg and the Karlsruhe. Later, the Furious and the Warspite joined the operations. The bulk of the Kriegsmarine forces was now riding, and the RN was trying to intercept these forces. The Spearfish torpedoed the Lützow, and on 13 April, after a failed air attack, it was the second battle of Narvik: The Warspite, escorted by several destroyers, pushed the German destroyers back to the bottom of the fjord, and the latter having exhausted their ammunition, Were scuttled and evacuated.

The rest of the operations were mainly terrestrial. After attempts and disembarkations, the allies recorded some successes, but the beginning of operations on the Netherlands and Belgium on the western front stopped all advance and the Allied troops were quickly evacuated to join the front to the south. During these cover operations, the aircraft carrier Glorious was surprised by the Gneisenau and its sister-ship and sunk. This was the only serious loss of the Royal Navy. The German losses had been much more severe… (read more)

Dunkirk and Operation Dynamo (may 1940)

Much of the international attention shifted away from Scandinavia, Norway and Denmark were occupied by the Germans, Sweden remained neutral, and Finland, partly dismembered by the USSR after a rough winter campaign. The western front suddenly exploded in May 1940, with the invasion of the Netherlands and belgium. The ground operations, as we know, had three phases: the attack on belgium, forcing the best Allied troops to enter it to take a stand, the decisive breakthrough of the ardennes, the race to the sea and then the encirclement of the forces Allies of the north. This encirclement continued and ended on the Dunkirk pocket, where the Admiralty envisaged a bold but extremely risky evacuation plan, the Dynamo plan.

The brain of this operation, dubbed “Dynamo” was Admiral Ramsay. In a few days, we mobilized literally everything that could float to be sent to the English Channel. But neither the Kriegsmarine nor the Luftwaffe remained impassive. While on the ground the pressure increased, seven German divisions were held at a distance by the 30,000 French soldiers of General Molinier, encircled near Lille by Rommel, who protected this operation, fighting for four days until the last cartridge . A halt was ordered by Hitler to the German troops. The suburbs of the city were taken by assault by grenadiers, while Goering made great efforts to annihilate the pocket of Dunkirk.

He put the city on fire, effectively destroying ships at the wharf, effectively defeating the docks and compelling the troops to be evacuated by the beach, which they did with ingenuity and using equipment that would have been abandoned and condemned to anyway. The solidarity of the British people with their soldiers, an army of occupation infinitely more valuable than the material-enormous- left there, shuttling in fragile yachts and boats with cargo and large ships, or directly crossing Middle of the stuka raids, the R-Bootes mines and S-Bootes outings. It was the “dunkerque miracle”, all the British troops were evacuated (the operation began on 26 May and ended on 2 June), as well as more than 100,000 French soldiers who formed part of the future FFL base. Churchill insisted that on June 3, they try to save the French rear-guard.

Battle of the Atlantic (1940-45)

The “battle of the Atlantic” is actually a series of very similar events that took place in the North and southern Atlantic. This was an attrition type of war, a “war of convoys”, vital for Great Britain, between the American continent and Great Britain on the one hand, and the Bay of Biscay, with the link to the Mediterranean and Suez The Far East. Opposing U-Boats only risked a small number in the Mediterranean, as the presence of the Royal Navy was important even after the elimination of France as a belligerent naval power.

With numerous small ships, corvettes and frigates, escort destroyers, aircraft carriers were the eyes of the fleet, ASW planes and even the frail torpedo carrier Swordfish proved formidable opponents for German U-boats.

On the other hand, as an ally of the axis, Italy had to make up for this weak presence of the Kriegsmarine in these waters. The battle for the Atlantic took place in several phases, punctuated by technical advances, espionage, and a formidable industrial war, between the United States on the one hand, producing cargos and escorts, and Germany On the other hand, abandoning the construction of surface units to devote themselves entirely to that of U-Bootes. The first phase saw the reinstatement of convoys, and the organization of convoys and forces available in the war room.

An episode like the Bismarck hunt (May 1941) or Operation Cerberus (the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau de Brest crossing to the waters of Norway in 1942) was only one of the events that marked this great battle, a war in the war. Following its great losses in destroyers, Great Britain received from the USA 50 destroyers (old lend-lease agreements), although old (1920), but it continued the construction of escorters itself, notably the Corvettes of the class Flower, River frigates and derivatives.

HMS Nelson firing

With the entry into the war of the USA (December 1941) it became clear that the latter brought all the weight of their industry into the balance. After a period of fluctuations, which resulted in American commercial traffic resisting the system of convoys (the golden age of German submariners), a common organization was finally adopted, and soon the industry was able to supply several hundred escorts. Escort carriers, and Cargos to replace the losses, the so-called “Liberty Ships” and the like, which eventually led to so many losses to the Kriegsmarine in 1944 that she could only renounce her Operations.

Malta in 1942

The Mediterranean Theater (1940-44)

The Royal Navy must undoubtedly have its finest pages in its struggle against the Regia Marina, the Italian navy, for the strategic control of the Mediterranean. With the capitulation of France in June 1940, the Royal Navy found itself alone, facing a recently belligerent Italy (before the lightning successes of its ally). So far, the Royal Navy had only a measured strength in the Mediterranean, to defend Suez and Alexandria. On the other hand, it had several bases: Gibraltar, Malta, and Alexandria. An agreement with France meant that the “Royale” was entrusted with the control of these common trade routes (France also needed the canal, which was after all Franco-British).

Supermarine Walrus hydroplane

The French Navy was therefore in 1922, placed in direct competition of the Regia Marina, only rival in the Mediterranean. The Turkish and Greek fleets were of lesser importance, and neutral, and in 1939, at the end of the civil war in Spain, also entered neutrality, its fleet had been divided and partly destroyed. With the French capital, the Royal Navy suddenly found itself face to face with the Italian Navy, deprived of a powerful allied fleet now neutral and potentially worse: Susceptible to be captured by the axis. In this perspective, Churchill ordered the controversial Catapult operation. We know what happened next.

After the partial neutralization of the French ships (the remaining ships had taken refuge in Toulon) in July 1940 and the auxiliary operations (Dakar, Syria), the Royal Navy was alone against Italy. Although this opponent was endowed with modern, powerful and numerous buildings, the regia marina lacked modern means compared to Great Britain: Aircraft carriers – Mussolini considered that he did not need it, given the configuration Of the Italian boot in the Mediterranean, giving him a vast maritime facade covering the whole center of the Mediterranean, and the bases of Libya, he could do without, dixit the “aircraft carrier italy”.

HMS Warspite in the Mediterranean

Seaplanes were more numerous and of quality. It was not until 1941 that a first aircraft carrier was started, the conversion of the liner Aquila. She was never completed. The lack of lighting and air coverage was going to cost him dearly. Another lack, but which was still rare at the time, the absence of a radar. Again, to increase his chances of detecting the opponent before being detected. It cost him no less than three cruisers at the battle of Matapan. Moreover, the British bore him a very rude blow during a bold operation in Taranto during a night-time air raid. As a result, the fleet had to retreat to other more protected ports.

But the Italians did not remain inactive: they owe to simple frogmen their best success against the Royal Navy, immobilizing for long months the battleships Queen Elisabeth and Valiant in Alexandria, only British ships of the Eastern Mediterranean by the Decima Flottiglia MAS. Numerous other clashes took place on convoys to North Africa, where Italy, after scathing reverses in trying to take Egypt, was joined by the innocent Rommel and his Afrikakorps. The scale turned to El Alamein, then the forces of the axis were completely caught after Operation Torch (Dec. 1942).

HMS York in Suda Bay, may 1941

Other battles in which the British navy took part took place in Greece (which capitulated in front of the Germans), then in crest (which cost the York cruiser), not to mention the long “blitz” of Malta. From May 1943, the presence of the axis in the Mediterranean had reduced to the Balkans and to Italy. The allies passed from Tunisia to Sicily and then to the south of Italy. After November 1943 and the Italian capitulation, the Germans set up an almost impassable defense. The Royal Navy played its part in the attempt to overthrow Anzio (landing of Operation Shingle, January 1944). A few months later, after heavy fighting, the Germans withdrew from Italy and the Balkans. The British admiralty was able to entertain units towards the Far East, the Suez Canal was safe…

HMS Hermes sinking in 1942.

The Far East (1942-45)

It was there, facing the Japanese, that the British experienced their worst setbacks, both at sea and on land. Recalling the tragic end of the “Z force” including the Renown and the Prince of Wales, destroyed by aviation in December 1941, the loss of the Hermes aircraft carrier on March 28, 1942 off Trincomanlee, All the Indian Ocean of the necessary naval means to prevent an invasion. Then, logically, with the debacle of the Dutch and Americans, the fall of Singapore, the “Gibraltar of Asia”. Clinging to Burma, Malaysia and even India, the British experienced a long eclipse that was only raised by the successes of the US Navy in the Pacific. It was not until about 1944 that Great Britain was able to entertain sufficient means of the Mediterranean for its operations in Asia.

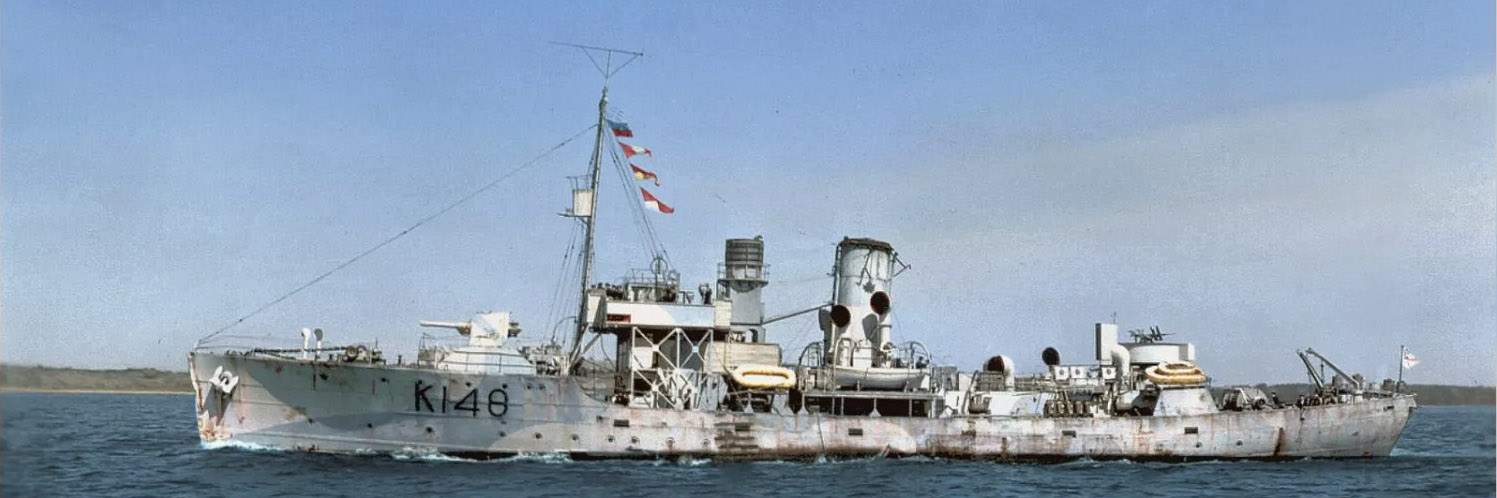

River class frigates – HMS Swale

WW2 British shipbuilding

Of course due to reduced industrial capabilites (manpower losses due to engagements), the Royal Navy gradually renounced to costly battleships (only the King Georges five were completed all other cancelled), and focused instead on aircraft cruisers, cruisers, but overall destroyers and escort vessels, like new classes of ASW frigates and corvettes.

Flower class corvettes- HMCS Regina

- 5 King Georges V class Battleships

- 2 Roberts class Monitors

- 3 Illustrious class aircraft carriers (1940)

- HMS Indomitable aicraft carrier (1941)

- Implacable class aircraft carriers (1944)

- Colossus class aircraft carriers (1944)

- HMS Unicorn aircraft carrier (1943)

- HMS Audacity escort aircraft carrier (1941)

- HMS Activity escort aircraft carrier (1942)

- HMS Pretoria Castle escort aircraft carrier (1943)

- Vindex class escort aircraft carriers (1943)

- HMS Archer escort aircraft carrier (1941)

- 3 Avenger class escort aircraft carriers (1942)

- 10 Attacker class escort aircraft carrier (1943) -> USA reverse LL 1946

- 23 Ameer class escort aircraft carrier (1943) -> USA reverse LL 1946

- 6 Empire Grain class escort aircraft carriers (1942)

- 13 Empire Oil class escort aircraft carriers (1943)

- Dido class cruisers

- Fiji class cruisers

- Bellona class cruisers

- Swiftsure class cruisers

- Abdiel class minelayers

- L/M class destroyers

- O/P class destroyers

- Q/R class destroyers

- S-W class destroyers

- Z class destroyers

- Ch/Co/Cr class destroyers

- Battle class destroyers

- Hunt class escort destroyers

- T class submarines

- S class submarines

- U class submarines

- X class midget submarines

- Black Swan class sloops

- Bittern 2 class sloops

- River class frigates

- Loch class frigates

- Bay class frigates

- Captain class frigates

- Flower class corvettes

- Castle class corvettes

- Bangor class minesweepers

- Bathurst class minesweepers

- Algerine class minesweepers

- Catherine class minesweepers

- Basset class trawlers

- Kiwi class trawlers

- Hills/Castle class trawlers

- Round table class trawlers

- Fish class trawlers

- British MTBs

- British MGBs

- British Motor launches

- LSI(L) class landing ships

- LSI(M/S) class landing ships

- LSI(H) class landing ships

- LSS class landing ships

- LSG class landing ships

- LSC class landing ships

- LSD class landing ships

- LST class landing ships

- LSH(L) class landing ships

- LSF class landing ships

- LCI(L/S) class landing crafts

- LCT(1-8/R/L) class landing crafts

- LCG class landing crafts

- LCF class landing crafts

- LCA class landing crafts

- LCP class landing crafts

- LCV class landing crafts

- LCM class landing crafts

- HMS Tyne depot ship

- HMS Adamant depot ship

- Athenes class aircraft tranports

- Auxiliary merchant cruisers (56 conversions)

- Ocean boarding vessels (16 conversions)

- Special service vessels (8 conversions)

- Sea-going auxiliary AA vessels (8 conversions)

- Coastal auxiliary AA vessels (32 conversions)

- Paddle minesweepers (39 conversions)

- Mine destroyers (10 conversions +2 built 1943)

- Auxiliary Minelayers (12 conversions)

- Other auxiliaries (100+ conversions)

Paper pojects

- G3 class Battlecruisers (cancelled)

- Lion class Battleships (cancelled)

- Malta class aircraft carriers

- Surrey class heavy cruisers

- G class destroyers

Completed postwar:

- HMS Vanguard

- Eagle class aircraft carriers

- Majestic class aircraft carriers

- Centaur class aircraft carriers

- Tiger class cruisers

- Weapon class destroyers

- Daring class destroyers

- A class submarines

The scale of the effort showing here, certainly not a net loss in industrial production, but quite the contrary. Being an Island, and remaining unoccupied, Great britain still could find the manpower and resources needed to produce an amazing array of warships and convert many others, only match by the Industrial might of the USA. And that’s only for military ships. In addition, Canadian shipyards produced no less than 180 Park ships (the equivalent of the Liberty ships) and 90 Fort ships (given to the US Government). In addition the Royal Navy received a considerable numbers of US-built ships, not only Victory cargos, but famously 50 destroyers (ex-“four stackers”), the C1-C5 type mass-built cargos (thos generally accepted by the British Ministry of War Transport took an “Empire” name).

MTBs (Motor Topedo Boats)

There is a category of “naval dust” in which a large navy like the Royal Navy excelled, perhaps unexpectedly: Motor boats. These small vessels were just an afterthought at the beginning of the previous conflict, yet they quickly gained an aura of versatility which had few equivalents and were found in the end irreplaceable. Traditionally indeed, MTBs were basically cheap to dispense a torpedo, potentially as battleship-killer as shown by the brillant attack of an Italian MAS in 1928. Just like submarines they were despised by the traditonalists as a “poor man’s navy” fighting force alongside coastal submarines and minelayers. Therefore, right during the interwar, attention was given to the type, but limited. Production scale in the interwar was also limited but in time, the more specialized types MGB (gunboats) and MA/SB (ASW boats) appeared during the war. They acquired fame and presented two main advantage: They were cheap and used non-strategic materials like a wooden construction, and rendered quantities of services. It was indeed more suitable to answer with these MTBs in the channel against German S-Boote and R-Bootes than destroyers. In addition, the gunboats replaced advantageously thanks to their speed, the old gunoats and rejuvenated the type, while other were used to save lives, mostly downed pilots and sunken ships crews, to the extant of their range.

Early interwar series: MTB1 and MA/SB 1

It’s only in 1936 (the last were launched in 1939) that these boats were given consideration again, amidst international climate degradation ad recent concessions to the Germans or the Japanese and Italian retirement of all treaties. The first serie comprised 18 boats, of 18 tons, capable of 38 knots and armed with two aviation-type 18 in TTs and 6 deep charges. The MA/SB were 5 boats launched in 1938-39 as a preserie experiment to be used as ASW patrollers. These 19 tons boats were capable of 30.9 knots but with almost twice the range, and armed with ten deep-charges. They were later converted as sea rescue ships as the war progressed. Related to these developments were also the three series of the “admiralty” motor minesweepers built from 1937 as an aswer to the German R-boote.

Vosper standard: The MTB 31 series (1940)

In late 1940 was defined the large model that was built in series (about 115). These “73 feets” were 47 tons boats fully loaded, so no longer a small craft, 22 meters long for almost 6 wide. They were armed this time by two marine TTs (21 in) or four aviation type instead (18 in), deep charges, a 40 mm bofors or 6 pdr/7 cwt or 4.5 in gun, 20 mm guns and multiple 0.5 MGs. They generally used three automotive engines and their compoenents, either Isotta Fraschini, Hall Scott, but more generally Packard which were delivered by Lend-lease in very large quantities. This allowed them to reach 40 knots. The series went on until the MTB 537 in 1945. They proceeded from the 1939 intermediary type (11 built), the MTB 24 series, 37 tons boat (43 fully loaded).

Fairmile standard: The Type D series (1942)

This legendary type was produced to around 229 boats, with many armament variants. They were much heavier at 102-1180 tons for 35 x 6.5 m, and generally better armed but appeared late in the war, in 1942. They were produced in droves until 1944, wtih the serials MTB-601 to 5029. The “C” types were gunboats. Other builders were Thornycroft, White, Camper & Nicholson, and British Power Boats (BPB) which “invented” the concept for UK in 1936. Gunboats were also built by Denny, Hawthorn Leslie, and Yarrow.

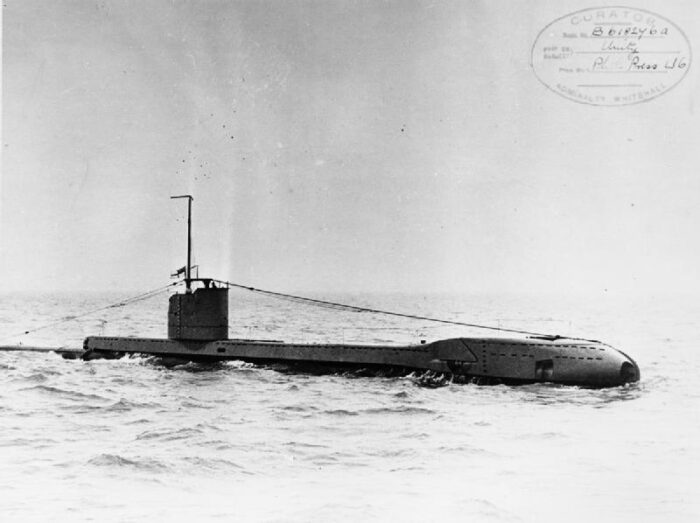

HMS Unity class submarines

Note: This very old portal (2010) is in dire need of a rewrite, which is done gradually from 2025.

Old Sources

Primary: Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-47

Fleet Air Arm

SONAR and ASDIC

Huff-Duff

Trawlers of the Royal Navy ww2

Royal Naval Patrol Service

The Royal Navy ww2 on naval-history.net

See also “Hog Islander”, T class tankers http://www.usmm.org/hogislanders.html

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign