Fairey Firefly: As we just saw the Attacker class, which operated in the Pacific for some the new Fairey Firefly, let’s have a look on the last generation of WW2 British aircraft carrier multirole aircraft, the quite successful Firefly. It was essentially a replacement for the Fairey Fulmar of 1940, with a much more powerful engine, a more rugged structure, and carrying twice as much payload while having blstering performances cloe to a regular fighter while capable of long range escorts unlike the short-legged, fragile seafire, or reconnaissance and strikes.

Introduced in 1943, it was declined in two main versions and constantly improved until production stopped in 1955 with 1702 made. That’s a measure of its quality and it served until 1956 for the RN, but soldiered on for many more years in other aviations, being exported to Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ethiopia, the Netherlands, India, Sweden, Thailand and also tested by the USN. A Legend.

The Fairey Firefly was a Second World War-era carrier-borne fighter/ASW aircraft operated mainly by Fleet Air Arm (FAA) and produced from 1941 by the Fairey Aviation Company. Its development was traced back to specifications by the British Air Ministry in 1938, and urgent need for naval fighters. At the same time it was revised to performed miultiple roles, a versatility tailored for the reduced air groups of former British carriers from Argus to Hermes, Furious and Eagle or the new armoured carriers in construction.

Part of the need for a dual-seat fighter was however mostly the simple realization that fighters would regularly become lost once they had passed beyond 20 nautical miles of the fleet. An observer was thus necessary (Technology would solve the problem later in WW2). Plus since the model was a dual fighter/reconnaissance model, its observation needed to be accurate, and so making the observer even more relevant. In fact this need was already highlighted in the 1920s, leading to tests made on the The Hawker Osprey in the early 1930s already, to test this concept. Its success led to the design of the design requirement leading to the Blackburn Skua dive-bomber/fighter and Roc turret fighter. Still, they were judged underpowered, over-weight, with poor aerodynamics, leading to a new spec. for the Fulmar. The basic concept was now for a “two-seat multi-role fleet fighter”.

The admiralty later asked for a 2-seat reconnaissance/fighter to replace the 1940 Fulmar, just introduced from this 1938 request. Specification N8/39 was issued March 1939 to replace the Sea Gladiator, Skua and Fulmar in one go. However Fairey was busy with mutiple projects and its model had a protracted development due to engines procurement and others, making it enter service from ealy 1943 and up to 1945. At this stage, it was no longer required as a fighter, with the Sea Hurricanes, Seafires, Wildcat, Hellcat, Corsairs were now in numbers for that role. The Firefly remained used as a “general puspose” model, ensuring long range escort, reconnaissance, strikes, and proving fast and sturdy, docile and overall well tailored for carrier operations. It was in fact ordered and constantly improved even after the war ended, notably in new roles.

Development

Naval fighter 1938-40 specifications

In 1938 the likelihood of a major conflict was clear for all at Westminster and the Air Ministry was tasked to issued a pair of specifications for particular types of aircraft until then postponed to feed the needs of the RAF. These were to be a new generation of naval fighters, the first since early 1930s biplanes, and it was precised both a conventional and a “turret fighter”.

Performance requirements for both was to have a 275 knots speed while flying at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) plus armament of eight 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns in one case and four 20 mm (0.79 in) Hispano cannon in turret for the other. The first was to replace the Fairey Fulmar, and interim design to already answer this specification and still in early development.

These specifications were updated in 1939 (Specification N8/39) and 1940 (Specification N5/40) whereas tenders were obtained. Official specifications were changed again and deleted the turret fighter specification (The awful Blackburn Roc was delivered still) being eliminated, the modified specification was common to a single and dual-seat fighters, capable respecively of 330 and 300 kn (610 and 560 km/h; 380 and 350 mph). Fairey proposed a single model with both configurations and the same Rolls-Royce Griffon engine. There was also another proposel with a larger airframe an Napier Sabre engine. Specification N.5/40 after reviewing these was a new set of specifications which simplified the request to the two-seater, an observer/navigator being requested for the open sea. The single seater was rerated to defend naval bases, and the contract went to Blackburn, with the Firebrand.

Design Work and trials

The design team at Fairey on this project was under H.E. Chaplin and the Fulmar was said to have been used as a base at least in concept, but all components were brand new. In June, 6, 1940, as in France the war was going south (it is not even an expression !) paperwork was still ongoing, a mocup was presented and approved by the FAA with the ink on drawing boards not dry, and on what Fairey promised, the Admiralty placed an initial order on the 12th for 200 aircraft.

Project F5/40F in December 1940 was named “Firefly”. However in July, the Battle of Britain commenced, and a lot of attention and resoufces were diverted to it, including at Fairey. The project took a massive delay wheeras war experience which emerged from it would led to a massive influx of proposed design changes.

Project F5/40F in December 1940 was named “Firefly”. However in July, the Battle of Britain commenced, and a lot of attention and resoufces were diverted to it, including at Fairey. The project took a massive delay wheeras war experience which emerged from it would led to a massive influx of proposed design changes.

The first three were prototypes. On 22 December 1941, so one year, 5 month after the signing, the first Firefly prototype had its maiden flight and with its reinforced airframe and much more powerful engine, it promised to deliver the goods, despite being 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) heavier than the Fulmar based on the use of the Griffon engine whic was already twice as heavy, and an armament pushed at that stage to a pair of 20 mm (0.79 in) Hispano cannon in each wing, quite enormous for a reconnaissance model, but good for a fighter. The prototype was 40 mph (64 km/h) faster compared to the latest Fulmar, and had for this improved aerodynamics, plus what delivered the Griffon IIB engine rated at 1,735 hp (1,294 kW).

On June 26, 1942, however the second prototype had a structural failure in flight and the company’s chief test pilot, Christopher Staniland, was killed in low-level flight. Theories by examining the wreck cited either the tail unit or faulty elevators. But the trials campaign was not even complete and the project was already a full year beyond schedule. Then were noted serious delays in fighter production. Alongside it, the Frirebrand was even more in troubles. The 5th sea lord adressed in a letter a recommendation to the 1st sea lord and first lord of the admiralty ciring issues with the Firefly and recommanded to pressure the RAF and obtain in emergency 500 Seafires to the Royal Navy.

Meanwhile, testing at Boscome Down arrived to its end. The model was judged globally satisfactory albeit heavy in the controls. To gain time in production the first batches of Firefly Mark I and FIs delivered were virtually a repeat of the prototypes, whereas improvements were worked on. In fact trials went on with the first production model in January 1943. In place of a prototype. It was to be delivered to the had pressed FAA. When received, impressions were mixed. Being heavier than the Fulmar, the new Firefly landed faster, and leeded more space.

The Air Ministry asked Fairey to a possible installation of a torpedo but it tried and failed. First carrier decks were made on Illustrious by February 8-9, 1943. By June, 30 had been delivered already. But the air assessment office deemed the bird in its current form “only suitable for training”. Eric Brown flew it from HMS Pretoria Castle and was rather favourably impressed still, his report was soon published and known by FAA pilots. Still, Brown found also severe issues: The Firefly at erratic porpoising with inadequate elevators and too heavy ailerons at high speed. Faireay answered to this by extended leading-edge elevators while ailerons and elevators were metal skinned. The pilot’s prosition was raised and were was a redesigned front armoured windscreen among other things. This went to the 1944 Mark IV after further tests were succesful in Boscombe Down by October 1943. The Firefly at last reached maturity.

Design

General conception

The Firefly was a low-wing cantilever monoplane. It had the following caracteristics:

-Oval-section metal semi-monocoque fuselage

-Conventional tail unit with a rounded triangular shape

-Forward-placed tailplane.

-Rolls-Royce Griffon liquid-cooled piston engine

-Four-blade Rotol-built propeller (3 bladed tested on protos)

-Large chin-mounted radiator for extra cooling

-Retractable (reinforced) main undercarriage, tail wheel

-Hydraulically-actuated main landing gear retracting inwards underside, wing centre-section.

-Widely-set of the carriage for carrier landings.

-Retractable arrester hook mounted underneath the rear fuselage.

-Separate pilot Cockpit located above the leading edge of the wing

-Rear observer/radio-operator/navigator positioned aft of the wing’s trailing edge.

-Separate jettisonable canopies.

-All-metal wing, folded manually along the fuselage sides

-Wings hydraulically locked in place when unfolded.

-Square tips, large Fairey-Youngman flaps for good handling at low speeds.

-Four 20mm cannon in the inner wings

Most pilots thought its general handling was relatively well-balanced, but it required physical strength to effectively make aerobatics. Legendary test pilot Eric Brown which of course tested the prototypes, said in “Wings of the Navy”:

My first impression was one of beautiful proportions; a careful mating of smoothly-cowled Griffon engine blending with cleanly-contoured fuselage and aesthetically pleasing elliptical wings.

In the 1942 trials for handling and performance at RAF Boscombe Down (Admiralty test pilots Mike Lithgow and Roy Sydney Baker-Falkner) and they had the same impression: Handling well but heavy commands. Less forgetting than a Fulmar for a novice. Two years later in 1944, rockets had been tested positively and noew about to be installed. In April 1944, tests with a double-underwing load of 16 rockets plus 45 US gal (170 L; 37 imp gal) drop tanks had the Firely still handling well enough to go to its target without being a stitting duck. Further tests were done with two 90 gallon (410 L) drop tanks or two 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs produced the same results albeit with a ésmall adverse effect on handling”. Handing a single 1,000 lb (450 kg) bomb was still manageable but not recommended. At 11,830 lb (5,370 kg) top speed was still 315 mph (507 km/h) at 16,800 ft (5,100 m) but it took 12 minutes to reach 20,000 feet.

Engine

FR Mark.IV 1944

As seen in the versions below, main changes came with the engine power and rate. The Mark I was split between the first batches having the prototype engine, the Griffon IIB engine rated at 1,735 hp (1,294 kW) and the last 334 having the better 1,765 hp (1,316 kW) Griffon XII engine. Next the Mark II and T.Mk. versions shared the same powerplants, and the Mark III never built had the proposed Griffon 61 engine. The latter had a two-speed two-stage supercharger with aftercooler and resembled in that the Merlin 61 and was rated for 2,035 hp (1,520 kW) at 7,000 ft (2,100 m) but was not adopted for production, already reserved for the Spitfire F.Mk.XIV and Mk.21.

From the Mark 4 onwards (postwar models), and that included the Mark 5 and Mark 6, the Firefly swapped onto the Rolls-Royce Griffon 74 which was a V-12 liquid-cooled piston engine rated for 2,300 hp (1,700 kW) take-off speed. It was even more efficient as fitted with a 4-bladed Rotol constant-speed propeller just like the earlier Marks, instead of the three bladed one from the Fulmar. Top speed rose to 367–386 mph (591–621 km/h, 319–335 kn) at 14,000 ft (4,300 m) and 330 mph (287 kn; 531 km/h) at sea level, cruising on long distances to 209 mph (336 km/h, 182 kn).

As for its range it rose to 760 miles (1,220 km or 660 nautical miles) on internal fuel, at 209 miles per hour (182 knots or 336 kph). Ferry range was 1,335 miles (2,148 km, 1,160 nmi) when carrying two 90 imperial gallons (110 US galllons or 410 metric Liters) with drop-tanks, the same cruise speed of 209 mph. It was of course less snappy than fighters and certainly not an interceptor, with a service ceiling 31,900 ft (9,700 m) and still capable to reach 5,000 ft (1,500 m) in 3 minutes 36 seconds or 10,000 ft (3,000 m) in 7 minutes 9 seconds and finally 20,000 ft (6,100 m) in 10 minutes 30 seconds. Wing loading was 43 lb/sq ft (210 kg/m2) and it could still carry a very large payload, double that of the Fulmar. This was hemped further by a power to mass ratio of 0.164 hp/lb (0.270 kW/kg). There was no upgrade engines after this, with the griffon 83 never adtopted.

Armament

The armament adopted from the start barely changed. It is interesting to note that due to its speed there was no need to install a tail machine gun, seen as a complication. But four 20 mm (0.787 in) Hispano Mk.V cannon in the wings was a pretty solid combination, if the Firefly was used against bombers and less agile models. Certainly more potent than the 0.303 inches machine guns of the initial Fulmar. It could also carry underiwngs a large variety of payloads, typically bombs, 2x 1,000 lb (454 kg) on inner underwing pylons and up to sixteen RP-3 60 lb (27.2 kg) rockets on 8 × zero-length launchers. They would combined only four of these under the outer underwings with bombs as well, and performed well as strike aircraft. They did wonders from the raids on Tirpitz to the Pacific and Korea.

Avionics comprised a Radar (inner left wing), Radio set and a Night-flying instrumentation and equipment. There were Night fighters and Fighter-reconnaissance variants as well as anti-submarine aircraft, replacing bombs by depth charges.

⚙ Fairey Firefly specifications |

|

| Gross Weight | 9,674 lb (4,388 kg)/12,727 lb (5,773 kg) |

| Max Takeoff weight | |

| Lenght | 37 ft 11 in (11.56 m) |

| Wingspan | 41 ft 2 in (12.55 m) |

| Wings folded | 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) |

| Height | 14 ft 4 in (4.37 m) |

| Wing Area | 330 sq ft (31 m2) |

| Engine | RR Griffon 74 V-12 LC piston engine 2,300 hp (1,700 kW) TO |

| Top Speed, sea level | 367–386 mph (591–621 km/h, 319–335 kn) at 14,000 ft (4,300 m) |

| Cruise Speed | 209 mph (336 km/h, 182 kn) |

| Range | 760 mi (1,220 km, 660 nmi) on internal fuel at 209 mph (182 kn; 336 km/h) |

| Climb Rate | 5,000 ft (1,500 m) 3 minutes 36 seconds |

| Ceiling | 31,900 ft (9,700 m) |

| Armament | 4× 20 mm HS Mk.V, 16x RP-3 60 lb rockets, 2x 1,000 lb (454 kg) bombs |

| Crew | 2 |

Operators

Used for ASW until 1956, replaced by the Fairey Gannet. Used by the 700, 703, 706, 719, 723, 724, 725, 728B, 730, 731, 732, 736, 737, 741, 744, 746, 748, 750, 751, 759, 764, 765, 766, 767, 768, 771, 772, 778, 780, 781, 782, 783, 784, 790, 792, 794, 795, 796, 798, 799, 804, 805, 810, 812, 813, 814, 816, 817, 820, 821, 822, 824, 825, 826, 827, 837, 851 Naval Air Squadrons.

No. 723, 724, 725, 816, 817, 851 Squadron RAN adn the Aircraft Research and Development Unit (T.5 VX373 1953).

Royal Canadian Navy: 825, 826 Squadron RCN and the Heavier-than-air Experimental Air Squadron VX-10, RCN

Royal Danish Air Force

Royal Netherlands Navy, Dutch Naval Aviation Service. VSQ-1,2,4,5,7,VSQ-860

Indian Navy, Indian Naval Air Arm, surplus airplanes from 1955 onwards, used for target tugging.

Svensk Flygtjänst AB. Bromma Airport: 19 TT.1 aircraft used between 31 January 1949 and 17 October 1963.

Royal Thai Air Force operated Fireflies between 1952 and 1966 as well as the Royal Thai Navy.

Variants

Firefly I/FR.I

Two variants of the Mk I Firefly were built; 429 “fighter” “Firefly F Mk I”s, built by Fairey and General Aircraft Ltd, and 376 “fighter/reconnaissance” Firefly “FR Mk I”s (which were fitted with the ASH detection radar). The last 334 Mk Is built were upgraded with the 1,765 hp (1,316 kW) Griffon XII engine.

Firefly T.3

Observer trainer of 1841 Squadron in 1952

Firefly T.7

trainer with wings folded in 1953

Firefly T.Mk 1

Firefly Mk IV

Preserved Firefly AS.6 demonstrating in Korean War-style markings

Firefly AS.Mk7

WJ154

Firefly U.9

Drone aircraft in 1959

Firefly NF.Mk II

Only 37 Mk II Fireflies were built, all of which were night fighter Firefly NF Mk IIs. They had a slightly longer fuselage than the Mk I and had modifications to house their airborne interception (AI) radar.

Firefly NF.Mk I

The NF.II was superseded by the Firefly NF Mk I “night fighter” variant.

Firefly T.Mk 1

Twin-cockpit pilot training aircraft. Post-war conversion of the Firefly Mk I.

Firefly T.Mk 2

Twin-cockpit armed operational training aircraft. Post-war conversion of the Firefly Mk I.

Firefly T.Mk 3

Used for Anti-submarine warfare training of observers. Postwar conversion of the Firefly Mk I.

Firefly TT.Mk I

Postwar, a small number of Firefly Mk Is were converted into target tug aircraft.

Firefly Mk III

Proposal based on the Griffon 61 engine, but never entered production.

Firefly Mk IV

The Firefly Mk IV was equipped with the 2,330 hp (1,740 kW) Griffon 72 engine and first flew in 1944, but did not enter service until after the end of the war.

Firefly FR.Mk 4

Fighter-reconnaissance version based on the Firefly Mk IV.

Firefly Mk 5/NF.Mk 5

Day and Night fighter version based on the Firefly Mk 5.

Firefly FR.Mk 5

Fighter-reconnaissance version based on the Firefly Mk 5.

Firefly AS.Mk 5

The later Firefly AS.Mk 5 was an anti-submarine aircraft, which carried American sonobuoys and equipment.

Firefly Mk 6/AS.Mk 6

The Firefly AS.Mk 6 was an anti-submarine aircraft, which carried British equipment.

Firefly TT.Mk 4/5/6

Small numbers of AS.4/5/6s were converted into target tug aircraft.

Firefly AS.Mk 7

The Firefly AS.Mk 7 was an anti-submarine aircraft, powered by a Rolls-Royce Griffon 59 piston engine.

Firefly T.Mk 7

The Firefly T.Mk 7 was an interim ASW training aircraft.

Firefly U.Mk 8

The Firefly U.Mk 8 was a target drone aircraft; 34 Firefly T.7s were diverted on the production line for completion as target drones.

Firefly U.Mk 9

The Firefly U.Mk 9 was a target drone aircraft; 40 existing Firefly Mk AS.4 and AS.5 aircraft were converted to this role.

Service

In WW2

The first unit which received the Firefly was RNAS Yeovilton, starting in October 1, 1943 and by December, there were 16 in operation. The general impression was good, as pilots found they could even out-turn a seafire in mock dogfight, provided they could muscle it out. On July 9, the squadron joined HMS Indefatigable for the first raid against the Tirpitz. Landing qualifications were helped by the hydraulically-operated Fairey-Youngman retractable flap systems.

The Firefly Mk I was used in all theatres of operations from late 1943 to August 1945 and well beyond, in Korea. If in March 1943, the first Mk Is were delivered to the FAA none was really operational before July 1944 and that was 1770 Naval Air Squadron on HMS Indefatigable with the first operations in the European theatre, in armed reconnaissance flights, anti-shipping strikes along the Norwegian coast but also air cover and aerial reconnaissance during the raids on the battleship Tirpitz.

It was used more and more as an anti-submarine patroller and long range strike/recce model looking for targets of opportunities. Wghe the production reached its apogee, these were stationed mainly with the British Pacific Fleet, Far East, Pacific theatres, against Japanese ground targets notably airfields and depots, oil refineries, between Malaya-Burma, Indochina and China, and the last Japanese-controlled islands. In the summer, this was against Kyushu itself, part of the home islands. The Firefly were the first British-designed aircraft to overfly Tokyo close to V-Day.

In May 1945 already in prevision of Operation Olympic, the spring 1946 assault against the home islands, the Canadian government accepted a British offer to loan two Colossus-class aircraft carriers to its navy, and to equip those, naval fighters based upon RCAN veteran airmen’s feedback, and to acquire the Firefly over opposition favouring the procurment of US aircraft instead. Fireflies were for this essentially stop-gap models before more advanced purpose-built aircraft were being constructed. Of course the war was over on 15 August, officialized on 1st September.

The cold war

Canadian Fireflies

Between 1946 and 1954, still, the RCN received and used some 65 AS Mk.5 Fireflies on its loaned aircraft carriers and some older Mk.I Fireflies. In the 1950s, Canada sold them off to Ethiopia, Denmark, and the Netherlands, at cheap price but third hand and already worn out. It stayed front line with the Fleet Air Arm until 1955, taking part in the Korean part for the same missions as before. Before even that treshold, older Fireflies declared surplus were sold to Australia, India and Thailand, plus those from the RCN and ex-RN to Denmark, Ethiopia and the Netherlands.

Aussies Fireflies

In 1947, the Australian government approved of formation of the Royal Australian Fleet Air Arm. Loke Canada she was loaned two <Majestic-class aircraft carriers from Britain both the Firefly and Hawker Sea Fury, forming the backbone of the newly formed Australian Carrier Air Groups: 108 Fireflies, the first delivered in May 1949, final in the August 1953, all pilots qualified.

The Korean War

During the Korean War in the 1950s, British and Australian Fireflies conducted anti-shipping patrols, ground strikes from carriers but also anti-submarine patrols and long range observation. They even acted as gunnery spotters after the disappearance of seaplanes used as such, assisting battleships in naval gunfire support. Due to their capacity to fly slow but high, and circle for a long time, they were found really useful. Fireflies loaned to the Australian Navy mostly did not feature cannons as they mostly served for ASW patrols. A few were damaged or short down by anti-aircraft fire, but most just landed and survived proving how much they were rugged.

With the capacity of having two bombs, eight rockets and their four 20 mm guns, Fireflies were found just as deadly as they were in WW2 and it was not raraz to see them attacking well defended bridges and railway lines, destroying North Korean logistics. Taking advantage of its ruggedness, pilots even developed new low-level dive-bombing techniques for greater accuracy, often taking FLAK while doing so. Pilots needed leg-size arms in order to make their resource as the Firefly notoriously flew “like a truck” for many pilots. Operations went on until the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement on 27 July 1953, still with post-armistice patrols until 1955.

The Malayan Insurgency

FAA Fireflies still in the Far East saw action as well in the Malayan Emergency, conducting ground-attack operations against Communist insurgents. Just as the larger Fairey Gannet was introduce, the Firefly was declared obsolete and surplus. The RAN placed them at the same time under secondary, adopting also the Gannet as well as the De Havilland Sea Venom. Sub-versions were developed for secondary roles, trainers, target tugs, drones, such as the Indian Navy which adopted ten target tug purposes in 1956. By 1958 most were sent for scrap.

The Indonesian Insurgency

In the late 1940s, the Royal Netherlands Navy deployed a single Firefly squadron to the Dutch East Indies from HNLMS Karel Doorman, another ex-Colossus class carrier. Talks broke down in July 1947 with the nationalists, so multiple air strikes were launched, but three Fireflies were shot down by ground fire. They still were used in 1960, after new territorial demands and threats formulated by Indonesia, and the remaining AS.Mk 4s were deployed to Dutch New Guinea. Operations started, still from the same carrier, early 1962. This ended with a political settlement signed between the two countries.

Legacy

The Fairey Firefly served in the Second World War as fleet fighter, in Korea, Malaya and Indonesia long after it was retired in order forces. The 1950s saw ther arrival of modern jet aircraft, and after being used in other roles, strike operations or anti-submarine warfare it lingered into the mid-1950s, the very last being the worn out Dutch models flying missions against Indonesian infiltrators in Dutch New Guinea and India’s tugs retired perhaps in 1970.

Gallery

Author’s illustrations: Types and liveries

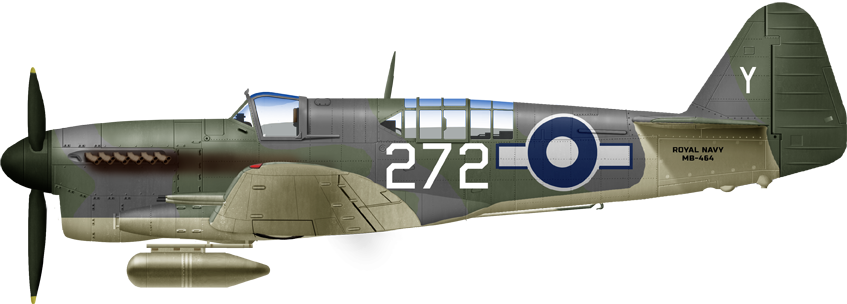

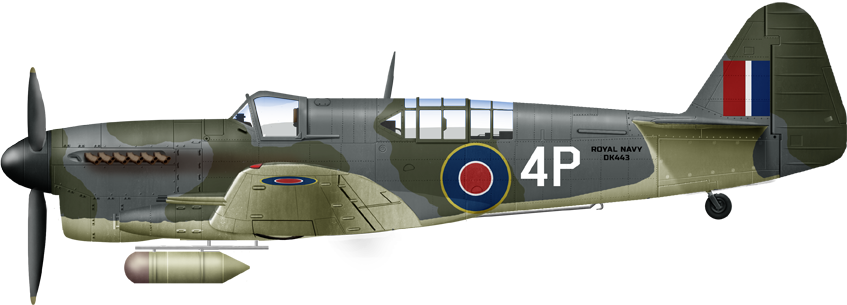

Mark I prototype, July-August 1943 tests Boscombe Down

FR1 1771 NAS HMS Implacable, Tirpitz Raid

NF2 772 NAS 1944

Mk.I 1770 NAS HMS Indefatigable 1945

Mk.I 837 Sqn HMS Glory, BPF 1945

FR Mk.I 816 NAS HMS Ocean 1946

Firefly FR1, 814 NAS, HMS Venerable 1946

FR1 1790 NAS HMS Puncher 1945

F1, HMS Vengeance 1948

AS7 719 NAS RNAS Erlington, 1953

Firefly AS6 HMAS Sydney, 817 NAS 1952

AS6, Dutch FAA, HMNLS Karel Doorman 1952

Firefly TT1 Duxford 1955

Firefly TT1 Esk.222 Royal Danish Navy 1950s

Firefly TT1 INS.112 Indian Navy 1953

Thai Mark I, late 1950s

Ethiopian model, 1960s

Additional photos

Links and resources

Books

Bridgman, Leonard. Jane’s Fighting Aircraft of World War II. Crescent Books 1988

Brown, Eric, CBE, DCS, AFC, RN., William Green and Gordon Swanborough. “Fairey Firefly”. Wings of the Navy, Janes

Bishop, Chris. The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II., Sterling Publishing 2002.

Bishop, Chris and Soph Moeng, ed. The Aerospace Encyclopedia of Air Warfare, Vol. 2: 1945 to the Present

Bussy, Geoffrey. Fairey Firefly: F.Mk.1 to U.Mk.9 (Warpaint Series 28). Milton Keynes, UK: Hall Park Books Ltd. 2001.

Buttler, Tony. Blackburn Firebrand – Warpaint Number 56. Denbigh East, Bletchley, Warpaint Books Ltd. 2000.

Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Fighters & Bombers 1935–1950. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing 2004.

Forsgren, Jan (January 2013). “New Tricks for an Old Seadog”. The Aviation Historian

Fredriksen, John C. International Warbirds: An Illustrated Guide to World Military Aircraft, 1914–2000

Harrison, William A. Fairey Firefly – The Operational Record. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife, 1992.

Harrison, William A. Fairey Firefly in Action (Aircraft number 200). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal 2006.

Mason, Tim. The Secret Years: Flight Testing at Boscombe Down 1939–1945. Manchester, 1998.

Pigott, Peter. On Canadian Wings: A Century of Flight. Dundurn, 2005.

Smith, Peter C. Dive Bomber!: Aircraft, Technology, and Tactics in World War II. Stackpole Books 2008

Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft since 1912. London: Putnam 1978.

Thomas, Graham. Furies and Fireflies over Korea 1950–1953. London: Grub Street, 2004.

White, Ian. “Nocturnal and Nautical: Fairey Firefly Night-fighters”. Air Enthusiast No. 107 2003.

Wilson, Stewart. Sea Fury, Firefly and Sea Venom in Australian Service. Aerospace Publications, 1993

Links

On armouredcarriers.com, development

On armouredcarriers.com, variants

warplane.com

classicwarbirds.co.uk

faaaa.asn.au

seapower.navy.gov.au

warbirdregistry.org

faireyfirefly.com

aeropedia.com.au

shearwateraviationmuseum.ns.ca

en.wikipedia.org

Video

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign