Kriegsmarine (1936), 24 submarines

Kriegsmarine (1936), 24 submarinesWW2 U-Boats:

Seeteufel (1944) | Type Ia U-Boats (1936) | Type II U-Boats (1935) | Type IX U-Boats (1936) | Type VII (generic) | VIIA | VIIB | VIIC | VIIC/41 | VIIC/42 | VIID | VIIF | Type XB U-Boats (1941) | Type XIV U-Boats (1941) | Type XVII U-Boats (1944) | Type XXI U-Boats (1944) | Type XXIII U-Boats (1944) | German mini-subs and human torpedoesThe Type VIIA as a sort of “pre-serie” for an experimental mid-sized oceanic submersible in the interwar was in everything a success. Apart for one aspect. It was soon clear its only real drawback was its fuel oil storage for its role and expected patrol areas. That’s what engineered solved by creating the next VIIB which had 33 tons more fuel in external saddle tanks, giving them the final appearance of the serie, and an extra range of 2500nm at 10 knots. It was also recognized their full speed when surfaced was a bit light, and the Type VIIB were also fitted with more powerful diesels. They ended slightly faster and, for extra agility, were fitted with two rudders instead of one. However, they carried the exact same armament but could carry three main torpedoes. U-83 was the only experimentally completed without a stern torpedo tube. In all, twenty-four were built, instead of a mere eleven for the VIIA. They became the basis for the famous mass-produced VIIC, our next step. The Type VIIB produced aces like Kretschmer’s U-99, U-48 (the most successful) and Prien’s U-47 of HMS Royal Oak fame or Schepke’s U-100.

Type VIIB development

Trailblazers: The Type A

The Type-VIIB was developed from the Type A, which theoretical development found its roots in the 1919 interdiction for Germany, signed by entente powers, to built submarines. However as the interwar progressed, Germany found a way for covert development via a front company, IVS (Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw Den Haag) at the Hague, an austere marine engineering firm. The idea was to propose designs to various nations without a domestic submersible industry, that would be built either locally or in the purchasing countries. Submarines were built for many nations, Turkey, Finland, Sweden, Russia, or Spain. All types tested various designs of large, medium, coastal and minelayers, with a starting point that were the excellent WWI Type UB-III and UC-II.

As for the Type VIIA, thei development went back as early as 1933, when their specs, range, armament, and manpower setups were all decided upon. It really was the Anglo-German naval treaty of 1935 that almost broke the Versailles treaty at least as far as the kriegsmarine was concerned. Not only the tonnage requirements were now of 35% of the Royal Navy and aligned both on the 1922 Washington and 1930 London treaty and that if on paper did not lifted the ban on submarines, the blatant violations remained unanswered. Plus as any submarines that could be built, they had at least to stay under Washington and London treaty limits. The Type-VII came after the larger experimental Type IA (prototypes for the Type IX) but the submarines advertised still seemed innocuous enough for the former allies, they were the small Type IIa and IIb coastal submarines intended for the Baltic.

The development of the intermediate Type VII was far more discrete and undertook when Hitler started to act more forcefully, notably after the “test” that was the rearmament of the Rheinland, and absence of reaction from France or Germany.

The Type VIIA was still modelled after the UB III, with a double-hull type but with a stern torpedo tube above the waterline and borrowed some aspects from IVs designs like the Delfinen class or more recent Russian S1 class (1934-38) and Spanish E1 design as well as the cancelled Type UG type of WWI resurrected from original blueprints. The VIIA design was solidified in 1934 and had a 200 tonnes difference and one less torpedo tube in the stern for five tubes, four in the bow, all operating from the pressure hull.

The pressure hull was too narrow aft for two tubes, and only had a non-reloadable tube above the waterline as a defensive weapon. The VIIA inner hull was designed to accept a total of eleven torpedoes less the five already preloaded in tubes, as for their WWI brethren. The reloading operation was still manual, hand-operated with cranks, chains and pulleys. Apart more modern gauges, pumps, radios, hydrophones, the technology was still largely the same as 20 years prior. These boats were submersibles, meaning surface-first and only submerging in emergency or for attacks. Already tactics theorized in the interwar looked at night surface attacks as a solution to catch up convoys, which would certainly be reproduced by the allies as the war broke up, and that impose a top speed of 16 knots. This was all that diesels of the time for this size and weight allowed.

The detailed design was shared between AG Weser (already designing and building the Type IA) and D. Krupp in Germaniawerft. Ten boats were approved in 1935 and ordered with six laid down at Weser and four at Krupp, completed for the first in 1936, others in 1936-37 so by September 1939, they had two-three years of training. They were the trailblazer for the Type VII, and their sea trials showed a number of issues that were corrected on the Type VIIB, laid down afterwards.

Improved across the board

When evaluating and comparing the commissioned Type I and Type VIIA, the Kriegsmarine soon realized the first had a right range but were slower to dive and less agile, whereas the second were nimbler and dive faster, but they lacked range. The high command under Grand Admiral Raeder thus asked for an improved version of the Type VII. In 1939, they were retrospectively called the Type VIIB in naval nomenclature but were developed as the U-45 class. Four requirements had to be addressed with this new design:

➾ A smaller turning circle

➾ A better surface speed

➾ A larger range

➾ More torpedoes

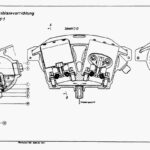

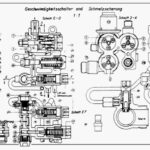

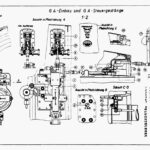

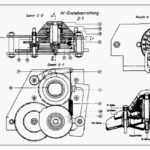

Two rudders and more torpedoes

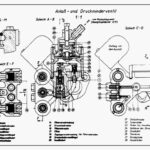

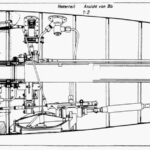

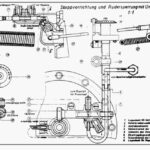

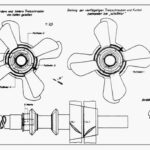

The issue of manoeuvrability was solved by the installation of two rudders instead of a large one due to space and power constraints. There were thus two rudders in line with each of the two propellers, in order that the wash of the propeller had a greater effect on the rudder. As for improved armament and reserve torpedo capacity, the stern internal arrangement with these two sid rudders now allowed the external stern torpedo tube to be relocated within the pressure hull, between the two rudders and thus to be reloaded while at sea, a crucial advantage, which went with two more spare torpedoes in addition to the one pre-loaded in the tube.

In addition, engineers managed to shoehorn two more spare torpedoes, one below the forward deck, another below the afterdeck, stored externally in pressure-tight containers between the pressure and outer hull. That idea of using this “lost space” was known by all nations building submarines, as it would have allowed on paper to reload when surfaced at sea if the conditions were right. However, there was a catch, as the weight of these torpedoes on top of the pressure hull could have a detrimental effect on stability.

Saddle Tanks

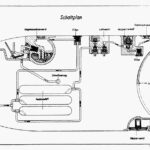

That’s when the third solution came out, killing once more two birds with one stone:

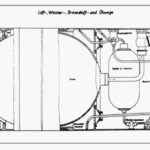

To improve the range, engineers added to the hull two external saddle tanks, above the outer hull, rising the beam and compensate for the slight loss of stability due to the added containerized torpedoes between decks. At the same time, the pressure hull also was extended by 2 m (6 ft 7 in) to increase internal fuel storage. The saddle tanks could house as much as 40,000 L (1,400 cu ft) fuel. Both combined enable an extra 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km; 2,900 mi) range at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) as calculated. These saddle tanks, also offered more advantages. Instead of having all fuel stored internally within the pressure hull, this external storage for once reduced the risk of oil leaks if the outer skin was damaged and procured a “buffer” in case of depth charge shock, given the viscosity of marine oil.

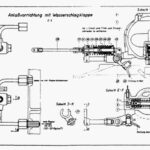

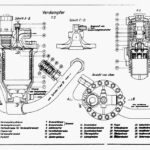

Diesels with Compressors

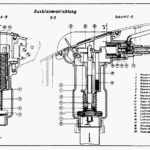

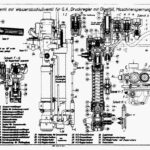

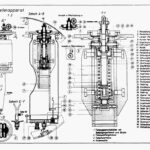

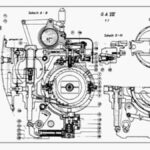

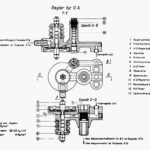

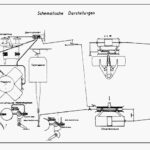

To adress the speed issue, as 16 knots seemed a bit tight, engineers looked after new marine diesels, and for comparisons, installed two types of diesel engines on the Type VIIB: The first types installed were revised, but similar MAN M6V40/46 as for the Type VIIA, and the second were the near identical Germaniawerft F46. Power output was increased just by installing superchargers, a new technology already used in aviation and that was translated for diesels.

The MAN engines had the compressor for the supercharger driven by exhaust gasses for power increases to 2,800 brake horsepower (2,100 kW). The Germaniawerft one differed in having its compressor driven by the shaft of the engine, delivering a more impressive 3,200 brake horsepower (2,400 kW) total. Thus, MAN powered U-boats managed 17.2 knots (31.9 km/h; 19.8 mph), and those with Germaniawerft diesels managed 17.9 knots (33.2 km/h; 20.6 mph), showing the superiority of the the second compression solution. As for the electric motors, they were also differences, but no increase in speed looked after, with some Type VIIBs having Brown, Boveri & Cie GG UB 720/8 electric motors as for the Type VIIA, and others later, having the AEG GU 460/8-276, mostly identical to the Boveri engines. See “powerplant” for more details. Surface displacement increased by 120 t (120 long tons), standard went from 500t (490 long tons) to 517t (509 long tons), albeit there might be some trickery in the numbers published at the time. But overall, the Type VIIB were certainly larger.

Construction

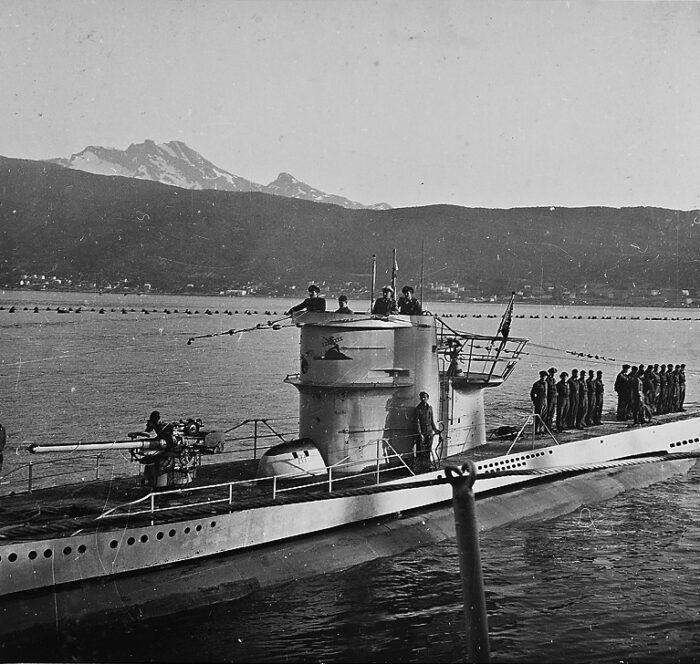

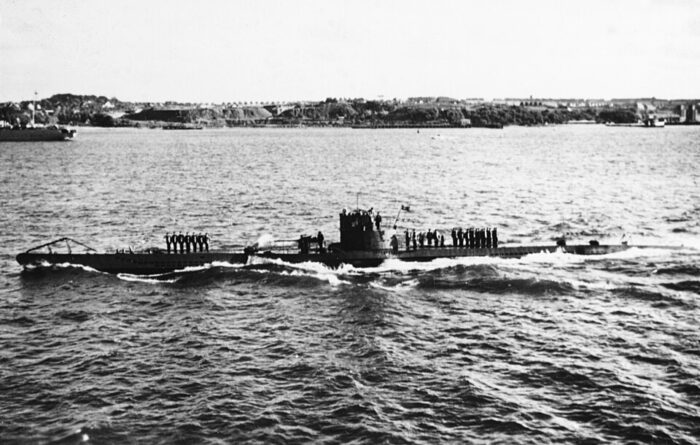

Commission of U-45 with the naval staff at Kiel on 25 June 1938. She was one of the best trained of the VIIB when the war broke up.

In short:

U-45 to U-55, and U-99 to 102 at Germaniawerft, Kiel

U-73 to U-76 at Vegesacker Werft, Vegesack

U-83 to U-87 at Flender-Werft, Lübeck

The first seven Type VIIB were ordered on 21 November 1936 from Germaniawerft. Then two more were ordered on 15 May 1937 and two more on 16 July 1937. After the revision of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, four more were ordered to Germaniawerft, Bremer Vulkan and Flender Werke, each. Flender Werke, which built their first U-Boats, also created an extra fifth Type VIIB, U-83 under export contract. However, it was taken over on 8 August 1938 by the German government, fearing an allied response (and possible war) after Hitler’s last moves. This modified Type VIIB lacked its stern tube. When war broke out for good in September 1939 however, only eight of these Type VIIB were in commission but until late 1940 the remainder over a total of twenty-four Type VIIB entered service, the last delayed until 1941: In all twenty were lost in action, only four survived to be scuttled at the end of the war. Like the Type VIIA they were retired from active service and used for training in the Baltic at some point, replaced gradually by the better VIIC.

Design of the Type VIIB

Hull & General layout

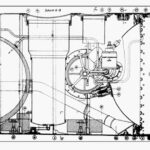

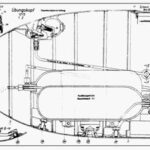

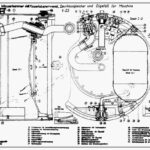

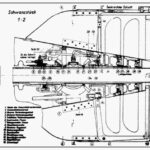

The Type-VIIB measured 66,5 (216 ft 5 in) x 6,20 (19 ft 6 in) x 4,74 meters (13 ft 1in) with a pressure hull that was 48,8 meters long (157 ft 5 in) for 4,7 meters wide (15 ft 4 in) compared to 45,5 meters (150 ft) for the same beam on the Type VIIA.

Compared to the Type VIIA which had a length of 65 meters (212 feet), a draft of 4 meters (15 feet), and a beam of 6 meters (19 feet).

The VIIB had a displacement of 753 tons (including fuel and water tanks) surfaced at 17.9 knots (33 kph, 21 mph) and 857 tons at 8 knots (15 kph, 9 pmh) submerged. She was 1,040 tons fully loaded with her crew and food on board. This was versus 626 tons surfaced and 745 tons submerged for the VIIA, quite a large difference. As per design specifics, they had a distinctive conning tower shaped after the one on the Type IA, slightly reduced.

It remained the same with much change for the VIIB. This conning tower was the reslt of WWI and interwar experience, and its size and shape were judged optimal to limit drag underwater while offering good enough protection against the elements while surfaced (especially in the winter’s North Sea and North Atlantic) while preserving a free space for lookouts to spot potential targets. The choice was made to eliminate the surface helmsman entirely. Instead, orders were simply relayed from the CT by voice pipes and/or direct voice. This helmsman post was kept, often under a windowed protecting cab forward of the conning tower in other navies, resulting is a somewhat bloated structure, which in practice was all but a hindrance when it came to dive fast. The Type VII but in general all German conning towers were created to offer the minimal amenities in order to maximize diving time, and it was notably adopted by the Italians in wartime, which suffered slow diving times. The Germans had recognized the danger of ramming already in WWI and now anticipated the danger of aviation. Soon, it would be needed to dive faster, and efforts were made to improve this on the VIIC, VII/41, 42 and 43.

The VIIB had a crew of 4 Officers and 40-56 men, not that different from the former boats. The extra space inside the pressure hull allowed the transportation of extra food, helping to reach 30 days patrols (or more) and fully exploit the additional torpedoes. Like the previous boats, there was also a small inflatable dinghy stored under the foredeck, near the torpedo boarding hatch.

Shipyards and Supply Chain

The construction involved Deschimag Bremen, Germaniawerft Kiel, but also Vulcan and Flenderwerft. It rested on a network of suppliers that for many, had a monopoly on their product. Let’s cite:

Electrical engines: Allgemeine-Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG, Berlin), Brown, Boverie & Co. (BBC, Mannheim) and Siemens-Schuckert AG (SSW, Berlin)

Batteries: By the former Accumulatoren Fabrik AG (today VARTA/VHB, Hagen)

Diesels: Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg (MAN, Augsburg) and Germaniawerft for the diesels. The latter’spublic yard essentially produced a copy of the first.

Watch and Attack periscopes: Zeiss works in Jena. Also providing optics for tanks and antitank guns, famous for their long range accuracy.

Main deck gun: The 8,8 cm was manufactured by Krupp.

Torpedoes: The G7 since WWI were designed and manufactured by the Kiel arsenal. They were tested by the Torpedo Trials Institute at Eckernförde.

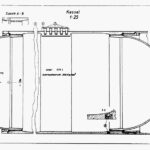

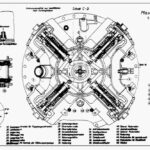

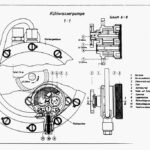

Powerplant

So, the VIIB came out with two alternative diesels, either two MAN M6V 40/46 inline 6-cylinder diesels developing 1160 hp at 470 rpm, or two Germaniawerft (Krupp) F46 inline 6-cylinder diesels which were near-copies of the first, but pushed further with a compressor to develop 1400 hp at 470 rpm. The M6V had a 57,8 litres capacity. This was a 6-cylinder 4-stroke engine with a cylinder diameter of 400 mm and a piston stroke of 460 mm.

So, the VIIB came out with two alternative diesels, either two MAN M6V 40/46 inline 6-cylinder diesels developing 1160 hp at 470 rpm, or two Germaniawerft (Krupp) F46 inline 6-cylinder diesels which were near-copies of the first, but pushed further with a compressor to develop 1400 hp at 470 rpm. The M6V had a 57,8 litres capacity. This was a 6-cylinder 4-stroke engine with a cylinder diameter of 400 mm and a piston stroke of 460 mm.

For underwater running, the VIIB had two BBC GG UB 720/8 electric motors developing 375 hp at 322 rpm or two AEG GU 460/8-276 developing 375 hp at 295 rpm.

This power was passed to two shafts propellers identical to the VIIA, with also the same three bladed bronze fixed pitch propellers as far i can find.

Top speed, as seen above, was 17.9 knots surfaced, the best speed achieved before 1942, and 8 knots underwater.

Surface range was also largely improved at 6,500 nautical miles (nm) on the surface at 12 knots and 72 nautical miles (nm) underwater at 4 knots.

The surface weight to displace was 753 tonnes (including fuel and water tanks) at 17.9 knots and underwater 857 tonnes calculated at 8 knots but 1040 tonnes when fully loaded underwater with crew.

The usual operating depth was 100 meters submerged, judged “safe” to avoid visual detection, with a crush depth at first established for safety at 200 meters, but the dials were marked to 250 meters. The normal time to dive was 30 seconds. It was the same as for the VIIA and judged in 1942 too important for safety. The goal for the VIIC and later models was to improve on this. It was better however than for the Type Ia and early Tyoe IX, much larger.

The new type steel developed for the Finnish submarines in the interwar helped to create a more resistant pressure hull, ideal for far deeper dives than any other submarines of the time, and it was one of the master aces of the Type VII for survivability. Test depth was at first around 180-200 m (650 ft) but on the Type VIIC it grew to 230 m (750 ft) with a final calculated crush depth of 250–295 m (820–968 ft) albeit it was still noted 200 m (safety limit) in many sources for the VIIA and B. To compare, with its small size, the Type VII could dive deeper than any other submarine in service at the time. The vintage US S-class still in service and comparable in size could reach 60m (200 ft). The British S-class could dive to 90m (300 ft) on average. So in early service the allies were unaware of this and never set up their depth charges that low.

Armament of the Type VIIB

Type G7e(TII) captured in Scapa Flow (dud) after being fired at HMS Royal Oak, preserved at Birkenhead.

Five 533 mm torpedo tubes (4 bow and 1 stern). 14 reserve torpedoes or 26 TMA or 39 TMB mines.

One 37 mm gun as designed, replaced by a 88 mm C35 L/45 when available.

One 20 mm C30 machine gun in the CT aft platform.

From 1944: Enlarged CT for one 37 mm gun and a flakvierling (4x) 20 mm Flak.

Deck Gun: 8.8 cm/45 (3.46″) SK C/35

The type VIIA U-boats had the 8,8cm as deck gun. The Type IA and later Type IX had the larger 105 mm deck gun, and the small Type II had a 20 mm AA gun. This deck gun was produced by Krupp but had absolutely no relation to the famous German Army 8,8 anti-tank and anti-aircraft gun. They did not even share the same ammunition. The 8.8 cm/45 (3.46″) SK C/35 was also used on Type 40 minesweepers and sub-chasers. After 1942, many U-Boats had it removed to install more FLAK instead. Only in the Mediterranean and the Northern Sea, U-boats kept their guns for a few months longer. It seems the original 37 mm was only sported at completion but the first two boats and replaced, the 8,8 cm was installed at completion on all the others as the production at Krupp was ramped up.

This was a pure “marine guns”, with material resistant to corrosion, simpler mechanisms and lubrication was limited or made internal. The goal was to have a permanent deck gun that could stay very long periods underwater at great pressures that could damage mechanisms and smaller parts. It was tested in a pressure chamber to the equivalent of around 200m (650 ft) which was the max theoretical diving depth at the time. These constraints made for a completely different gun than the more complex land-based 8,8 cm FLAK gun.

The 8,8 cm caliber had been used for many decades in the German Navy, all the way back to the 1890s and saw many iterations over the years. Unlike its land-based counterpart, it was a pure anti-ship model as it was limited by its mount to 30°.

The model used on the Type VIIA and following was designed in 1935 and introduced in 1938 so it’s likely the Type VIIA U-Boats were completed without it. It was a very rugged gun, albeit not having the same punch as its land counterpart, and a AP round (AP 35) which was far weaker. At 700 mps (2,300 fps) versus 840 m/s (2,690 ft/s) it lacked the speed and range as well, but was very impressive an efficient as a naval gun, especially for such as “small” submarine. It’s just that from 1942, no U-Kaptain would be mad enough to try to sink a cargo while surfaced with this single gun, staying exposed for an hour or more. More

Specs 8.8 cm/45 (3.46″) SK C/35

Weight: 5,346 lbs. (2,425 kg), Barrel alone 1,711 lbs. (776 kg)

Lenght: 157 in. (3.985 m) bore 146.9 in (3.731 m).

Rate of fire: 15 rounds per minute

Shell: 33 lbs. (15 kg) 14 in (385.5 mm) HE, AP, Incendiary, Illumination (90-10.2 kgs).

Busrting charge: AP 35S 0.064 kg. HE L/4.5 0.698 kg, HE L/45 Inc. Brandkörper A

Propellant charge: 3.70 lbs. (1.68 kg) RP C/32, 3.90 lbs. (1.77 kg) RP C/38, 4.63 lbs. (2.1 kg) RP C/40N and PL/V41

Muzzle velocity: HE 2,300 fps (700 mps), Illum.: 1,970 fps (600 mps).

Range: 13,070 yards (11,950 m) at 30°. Depression -10° on Ubts LC/35 mount.

Ammunition stowage Type VII: 220 rounds.

Barrel life: 12,000 rounds.

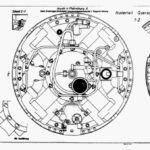

Torpedoes

For the Torpedo tubes I-V, Piston was 70 kg, forward +25.25 with piston inserted, 1680m3 and aft: -26,15 without piston and 1740m3. There was an upper deck container forward and aft, with and without G7A. Torpedo in the tubes were the G7E/G7A models. There was also a reserve stowage forward, aft. Note: The “Torpedokrise” lasted until the end of 1941. The result were scores of duds or precocious detonations. It was less severe than the infamous USN Mark 14, but limited the effectiveness of the Type VIIA, B and C until solved.

G7A Torpedoes

Direct involvement of Spain in the development of German torpedoes started in the late 1920s when the Spanish businessman Horacio Echevarrieta decided to start a torpedo factory in Cádiz (Fábrica Nacional de Torpedos, F.N.T. / National Torpedo Factory) with a theoretical production capacity of 100 torpedoes per year and license-build German torpedoes. But the G7 was created in WWI. The lineage comprised the pre-WWII G7A (T1) using compressed air and thus leaving a visible trail of bubble.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G7a_torpedo

The G7a (TI) torpedo calibre was the standard 533.4 mm (21 in), for a length of 7163 mm (23 ft 6 in), fitted with a Ka or Kb warhead, Pi1 or Pi2 pistol. The warhead carried 280 kg (617lbs) Schießwolle 36. The model remained standard issue from 1936 to the end of WW2. This model was of a straight-running unguided model only controlled by a gyroscope. It could be set at a variable speed, 5,000 m at 81 km/h or 7,500 m at 74 km/h (8,250 yd at 40 kt) but also “long course” 12,000 m at 55.6 km/h. The 44 knots model setting was only used by Schnellboote with a reinforced engine.

Later were introduced the G7a (T2) electric, T3, T4, T5 (Zaunköning), and T11, but the latter remained a prototype.

In 1940-41, the Type VIIA were likely upgraded with the G7a T2:

G7E Torpedo (T2)

They had a unique setting of 5000m at 30kts. Standard torpedo of the war, it suffered from early issues with the internal depth-keeping equipment and firing pistol, solved after the Norwegian Campaign,but only gradually implemented. The “torpedokrise” was thus only resolved in mid-1941 when all stocks had been changed or spent. Full effectiveness on the T2 was obtained when preheated electrically to 30 degrees Cent (86 F) before firing. If not, speed was down to 28 knots for 3000m.

The G7e(TII) already entered service in 1936 and was a “secret weapon” for the Germans as much as was the “long lance” (type 93) for the IJN. Its existence was virtually unknown to the British until fragments were recovered following the sinking of HMS Royal Oak in October 1939. The G7e was electric, no longer using a wet-heater (steam-driven) and was simpler simpler and cheaper to manufacture (half the cost), as well as being virtually silent, leaving almost no visible trail of air bubbles.

The latter was by far its biggest advantage. It was virtually invisible in the dark north Atlantic and spotters needed to be posted high and have an excellent view to see them via the water disturbances they still create at this speed, so a very faint trail underwater, still. It was most often heard first but the hydrophones’ operator, getting a bearing.

The T2 had many issues, it was however less reliable and performed unpredictably compared to the G7a(TI). Just like the Mark 14, both the contact and magnetic detonators were unreliable. But the feedback loop was quicker and there was less inertia from the engineering department to solve these issues way quicker than in the US. The T3 became the Stradivarius of the G7 type in 1942.

G7E Torpedo (T3)

By mid-1942 the improved version had an increased battery capacity, asking for a 50% superior range as the T3a. Range was now, 7500m at 30 knots, but in a preheated state it was 4,500m at 28 knots. More detail to come for the next articles on the Type VII. Thy did not have the previous faulty exploders and had a brand-new system, with a perfected proximity feature. This enabled what the US and other navies looked for, a torpedo that can dive below the keel of a ship and explode, breaking it. More on these (and other G7 models) on the next Type VIIIC.

TMA Mines

In alternative to their torpedoes, the Type VIIA U-Boats could also carry 22 TMA mines, for a ration of two for one. The Type VIIs did manage many mine laying missions, but the size of their individual minefields was fairly limited, so losses were few, but not absent. The TMA mines were shaped as cylinders, they were moored mines, attached by cable to float above the surface, while the anchor secured its position. The correct depth setting needed to be applied depending on the observed depths. Two could be carried in each torpedo tube.

Length/Diameter: 11.1ft (3.38m)/21in (533mm)

Maximum Depth: 270m

Warhead: 215kg.

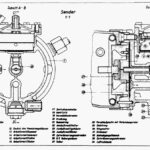

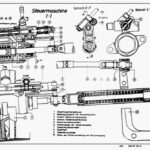

Sonars

Gruppenhorchgerät

The GHG was an early acoustic system, a hydrophone array used on all models, including the Type VII. It was developed in WWI already following Pierre Curie discovery in 1880 using the piezoelectric principle. Atlas Werke AG in Bremen and Electroacustik (ELAC) in Kiel worked on transducers, detectors and amplifiers and found the best being the Seignette crystal formed from a mixture of different salts. From 1935, crystal receivers were permanently installed on German submarines.

The GHG was the final product, GHG made of two groups of 24 sensors, one on each side of the boat. Each sensor had a tube preamplifier. These 48 low frequency signals were routed to a switching matrix and the sonar operator could determine the side and direction of the sound source. To improve resolution, a frequency of 1, 3 and 6 kHz could be setup. There was however a dead zone of 40° fore and aft, but range was 20 km to individual ships and 100 km against a full Convoy.

The Search area was 2 × 140° with a resolution of less than a degree at 6 kHz, 1.5° for 3 kHz, 4° for 1 kHz and without crossover 8°.

The Royal Navy in May 1942 captured a submarine and its ELAC equipment. Later the Balkongerät was tested on U-194 in January 1943 and installed a few Type VII/41 or 42 but became standard on the Type XXI.

Appearance

Albeit this will be treated much more in detail on the VIIC, the VIIB started career with the following:

Prewar: Upper colour medium blue-grey Dunkelgrau 51 (RAL7000). Darker grey upper colour may have been used for a period prior to the war. Lower colour dark grey Schiffsbodenfarbe III Grau (RAL7016)

August 1939: Pre-war markings and inscriptions removed.

Winter 1940: Upper colour changed from Dunkelgrau 51 to a darker grey, possibly Schlickgrau 58. Ported during refits. Upper colour remains a shade of grey.

Dunkelgrau 51: (RAL7000, FS35237, RGB: R120, G131, B137)

Schiffsbodenfarbe III Grau: (RAL7016, in between FS36076 and FS35042, RGB: R54, G61,

B65)

Schlickgrau 58: (slightly darker than FS36134, RGB: R77, G81, B76)

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 753 tonnes surfaced, 857/1040 t submerged |

| Dimensions | 66.5(48.8 ph) x 6.20(4.7 ph) x 4.70-74 m draught |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 2800-3200 bhp diesels, 750 shp electric |

| Speed | 17.9 knots surfaced, 8 knots submerged |

| Range | 8,700 nmi/10 knots or 6500/12 kts surfaced, 72 nmi/4 knots submerged |

| Depth | 220 m (722 ft), CD 230–250 m (750–820 ft) |

| Armament | 5× 533 mm TTs (1 stern ph), 14 torpedoes/26 TMA/33 TMB mines, 8.8 cm deck gun, twin 2 cm C/30 AA |

| Sensors | Gruppenhorchgerät |

| Crew | 4 officers, 40–56 enlisted |

General Evaluation: Kriegsmarine’s top scorers

The case of Gunther Prien:

Günther Prien (16 Jan 1908 – presumed 8 Mar 1941) was a famed German U‑boat commander during World War II, best known for his audacious raid on Scapa Flow aboard U‑47 and for becoming the first U‑boat officer to receive both the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and its Oak Leaves. Born in Osterfeld, Prussia, Prien began in the German merchant marine (1923), rising from cabin boy to first mate by 1932, before joining the Reichsmarine and later transferring to U‑boat service. He commissioned U‑47 in December 1938 and was promoted to Kapitänleutnant by February 1939.

Günther Prien (16 Jan 1908 – presumed 8 Mar 1941) was a famed German U‑boat commander during World War II, best known for his audacious raid on Scapa Flow aboard U‑47 and for becoming the first U‑boat officer to receive both the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and its Oak Leaves. Born in Osterfeld, Prussia, Prien began in the German merchant marine (1923), rising from cabin boy to first mate by 1932, before joining the Reichsmarine and later transferring to U‑boat service. He commissioned U‑47 in December 1938 and was promoted to Kapitänleutnant by February 1939.

On 14 October 1939, her led U‑47 through Holm Sound into the supposedly impregnable Scapa Flow anchorage—a daring, high-risk infiltration. He torpedoed the British battleship HMS Royal Oak at anchor, sinking it and killing 833 crewmen. This was a tragedy in Britain, which was never repeated.

Prien gained national hero status, his conning tower adorned by this distinctive bull emblem. He completed ten war patrols, sinking over 30 Allied ships (for c200,000 GRT). Her hit a peak of fame and controversy as a propaganda figure during the war. He was in a final patrol in February 1941, sinking several ships in early March, then vanished. Officially declared lost around 7–8 March 1941 near Ireland, HMS Wolverine may have been involved but records don’t match and today’s mechanical failure or accident is more likely.

He was the subject of films and literature, notably “U‑47 – Kapitänleutnant Prien (1958)” movie and US TV’s “The Silent Service” featured in an episode.

He was the subject of films and literature, notably “U‑47 – Kapitänleutnant Prien (1958)” movie and US TV’s “The Silent Service” featured in an episode.

His wartime memoir, “Mein Weg nach Scapa Flow” remains in print. One of the most famous book about him is Dougie Martindale’s “The Bull of Scapa Flow: From the Sinking of the HMS Royal Oak to the Battle of the Atlantic”. A fair commander as seen in his early patrols, always watching over the safety of the crews from the ship he arrested in the old commerce raiding laws her was proven tactically skilled and fiercely ambitious. His bold tactics cracked a symbolic target, turning him into a wartime icon for Germany. Despite controversy over his political alignment and harsh leadership style, his exploit remains the shining WWII U-Boat most daring naval action.

U47 underway after commissioning.

Preparing the Type VIIC.

The Type VIIB was found a very satisfactory design, and could have been mass-produced when the war broke out, but when submarines complained of their primitive underwater detection means, and engineers worked on a modern sonar, which was to be installed and needed extra room. This space had to be created by adding an entire frame section amidship of 0.6 m (2 ft) in the control room. This, in a nutshell, created the Type VIIC. Extra weight decrease speed marginally (this was later compensated by improved compressors and other diesel improvements). This extra section was also repeated for the outer hull and saddle tanks, but instead of extra fuel oil, this added space was used for an extra buoyancy tank as the new priority was to dive faster (in addition of new crew drills, like the “running to the bow” famously showed by the 1980s “Das Boote” movie to shift extra weight forward. One of the electrical air compressors was also replaced by a Junkers diesel-powered air compressor (another borrowing tech from the Luftwaffe) to reduce demands on the limited internal electrical supply.

The Type VIIB was found a very satisfactory design, and could have been mass-produced when the war broke out, but when submarines complained of their primitive underwater detection means, and engineers worked on a modern sonar, which was to be installed and needed extra room. This space had to be created by adding an entire frame section amidship of 0.6 m (2 ft) in the control room. This, in a nutshell, created the Type VIIC. Extra weight decrease speed marginally (this was later compensated by improved compressors and other diesel improvements). This extra section was also repeated for the outer hull and saddle tanks, but instead of extra fuel oil, this added space was used for an extra buoyancy tank as the new priority was to dive faster (in addition of new crew drills, like the “running to the bow” famously showed by the 1980s “Das Boote” movie to shift extra weight forward. One of the electrical air compressors was also replaced by a Junkers diesel-powered air compressor (another borrowing tech from the Luftwaffe) to reduce demands on the limited internal electrical supply.

Early Type VIIC U-boats also were fitted with the new 2,800 bhp (2,100 kW) MAN M6V40/46 diesel, which gave a top speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph), others having the 3,200 bhp (2,400 kW) Germaniawerft F46, also compressed, for 17.7 knots (32.8 km/h; 20.4 mph). The electric motors were now produced by four companies on the same exact design, for had identical performances, as the AEG GU 460/8-276 and BBC GG UB 720/8 (Type VIIB) but also the new Garbe, Lahmeyer & Co. RP 137/c and Siemens-Schuckert-Werke (SSW) GU 343/38-8. These new companies joined in production due to the immense orders that were in place as the war started. Mass production was required.

The VIIC repeated the same torpedo tube arrangement as before, but a few boats experimented with new arrangements: U-72, U-78, U-80, U-554, and U-555, only had two bow tubes. U-203, U-331, U-351, U-401, U-431, and U-651 had no stern tube. The first VIIC, U-93, was commissioned on 30 July 1940 and provided useful data for future improvements across the board, but all limited in scope so that by the end of the war, 577 Type VIIC had been built, on fifteen shipyards, with incremental yet unspectacular changes. The greatest changes triggered two new sub-types sometimes called improperly “U-Flak”, the VIIC/41 and VIIC/42.

So to be precise, there were 568 boats commissioned for the Type VIIC, 91 Type VIIC/42, none Type VIIC/42*. The remainder were 6 Type VIID and 4 VIIF, 4 “Flak-U” and many paper projects.

*The VIIC/42 had 176 orders, 164 contracts signed however, and they were all cancelled on 30 September 1943 as the Elektro Boat XXI looked far more promising.

They will be developed in the following months.

VIIB in service

U-45

U-45

U-45 was ordered on 21 November 1936 and laid down at Germaniawerft, Kiel, yard number 580 on 23 February 1937, launched on 27 April 1938, commissioned on 25 June 1938 under command of Kapitänleutnant Alexander Gelhaar. During her wartime service, she had two war patrols, sank two vessels (19,313 GRT).

U-45 was ordered on 21 November 1936 and laid down at Germaniawerft, Kiel, yard number 580 on 23 February 1937, launched on 27 April 1938, commissioned on 25 June 1938 under command of Kapitänleutnant Alexander Gelhaar. During her wartime service, she had two war patrols, sank two vessels (19,313 GRT).

After training exercises, she left Kiel for her first war patrol on 19 August 1939 (same commander) and sailed for 28 days without kill, before returning to base at Kiel on 15 September 1939.

Her second war patrol started on 9 October 1939, which was her final patrol. On 14 October, she sighted and attacked convoy KJF-3, 230 nautical miles (430 km; 260 mi) southwest of Ireland. This attack sank the 9,205 ton British freighter Lochavon and 10,108 French merchant ship Bretagne. She also missed the 10,350 ton British steam merchantman Karamea as the torpedo detonated prematurely. Survivors were picked up by HMS Ilex. During a wolfpack attack later on an Allied convoy she was detected and sank by depth charges from British destroyers HMS Inglefield, Ivanhoe and Intrepid on 14 October 1939, southwest of Ireland.

U-46

U-46

U-46 was ordered on 21 November 1936 to Germaniawerft, Kiel at Yard number 581, laid down on 24 February 1937, launched on 10 September 1938 and commissioned on 2 November 1938 a Cost of 4,439,000 Reichsmark. First commander was Kptlt. Herbert Sohler. She was assigned to the 7th U-boat Flotilla, as lead boat. She left Kiel on her first war patrol on 19 August 1939, North Sea, returned on 15 September. On 13 April 1940 while off Narvik, she was depth charged, severely damaged by destroyers escorting HMS Warspite. Sohler made six war patrols, failed to score any successes until removed from command on 21 May 1940, replaced by Engelbert Endrass, former XO of Günther Prien’s on U-47.

On 1 June she sortied to patrol in the North Sea and Atlantic and the 6th she torpedoed the AMC Carinthia, then the Finnish merchant SS Margareta on 9 June and on the 11th damaged MV Athelprince, then sank SS Barbara Marie and SS Willowbank on the 12th, then SS Elpis on 17 June, and was back to Kiel on 1 July (31 days with a tally of 35,347 tons +8,782 tons damaged.

In August she was moved to Bergen and on the 3th she was spotted by the T class sub HMS Triad. Both were surfaced then she spotted and attack her with her 102mm gun at 22:30. U-46 dived, pursued by Triad, but they lost contact. U-46 made another patrol from 8 August and on the 16th damaged the Dutch SS Alcinous, on 20 August the Greek SS Leonidas M. Valmas (total loss). On 27 August she sank the AMC HMS Dunvegan Castle, and SS Ville de Hasselt on 31 August, SS Thornlea on 2 September SS Luimneach (Irish steamship, neutral flag) on 4 September. On the german side it was assumed abandoned by her crew as soon as she was spotted.

U-46 was reassigned to Lorient on 6 September, after 29,883+ 6,189 tons damaged.

Next she departed from Saint-Nazaire for a 7 days patrol (2 ships sunk: 26 September SS Coast Wings, SS Siljan 3,920 tons). On 13 October she was in a wolfpack against convoys SC 7 and HX 79. She sank SS Beatus, SS Convallaria and SS Gunborg on 18 October, SS Ruperra and SS Janus on 19 October and 20 October. On 25 October she was spotted and attacked by three Lockheed Hudsons of No. 233 Squadron RAF. She was back to Kiel on 29 October (tally 22,966 GRT).

Departing from Kiel on 12 February 1941 to St. Nazaire (4 March) no kills. Next patrol saw her sinking on 29 March SS Liguria, then SS Castor on 31 March, SS British Reliance on 2 April. SS Alderpool damaged on 3 April (17,465 GRT, 4,313 damaged). Next patrol saw her damaging SS Ensis (8 June), SS Phidias (9 June) but Ensis rammed and damaged her CT and bent her periscope. Endrass made his last patrol from 26 July to 26 August (no kill). On 24 September U-46 became a training boat with the 26th U-boat Flotilla under Peter-Ottmar Grau, Konstantin von Puttkamer, Kurt Neubert, Ernst von Witzendorff, Franz Saar, Joachim Knecht, Erich Jewinski, then on the 24th U-boat Flotilla in April 1942, decommissioned at Neustadt in October 1943, worn out.

She saw no more service until scuttled on 5 May 1945 in Kupfermühlen Bay.

U-47

U-47

U-47 was ordered on 21 November 1936 to Germaniawerft, Kiel at Yard 582, laid down on 27 February 1937, launched on 29 October 1938 and commissioned on 17 December 1938. U-47 for ten combat patrols, 238 days at sea, sank 31 enemy ships (162,769 GRT and 29,150 tons), damaged 8 more before disappearing on March 1941. She was in the 7th U-boat Flotilla on 17 December 1938, and sailed on 19 August 1939 for her pre-positioned patrol from Kiel. She circumnavigated the British Isles, entered the Bay of Biscay and on 3 September, on active search, leaning about the sinking of SS Athenia by U-30. She inspected and released a neutral Greek freighter and met later two further neutral vessels.

U-47 was ordered on 21 November 1936 to Germaniawerft, Kiel at Yard 582, laid down on 27 February 1937, launched on 29 October 1938 and commissioned on 17 December 1938. U-47 for ten combat patrols, 238 days at sea, sank 31 enemy ships (162,769 GRT and 29,150 tons), damaged 8 more before disappearing on March 1941. She was in the 7th U-boat Flotilla on 17 December 1938, and sailed on 19 August 1939 for her pre-positioned patrol from Kiel. She circumnavigated the British Isles, entered the Bay of Biscay and on 3 September, on active search, leaning about the sinking of SS Athenia by U-30. She inspected and released a neutral Greek freighter and met later two further neutral vessels.

On 5 September, Engelbert Endrass was her 1st watch officer when he spotted SS Bosnia. He stopped her by a bow shot of 88 mm deck gun, but the latter radioed an alert. Prien made 3 more hits prompting the crew to abandon ship, but assistance was given, brought aboard, helping to set up a lifeboat capsized earlier. A Norwegian vessel picked them up later. A single torpedo sank her and her load of sulphur (2,407 GRT). A day after same procedure on the 4,086 GRT SS Rio Carlo. After a warning and several hits, the crew abandoned ship, and she was sunk by a single torpedo, but also boarded and ensured there were enough provisions for survivors but had to dive when aircraft appeared.

On 7 September, this was SS Gartavon and this time her aimed at her mast and radio antenna. The crew put into a lifeboat, but suddenly it appeared the ship was rigged to try to ram her, making steam so U47 made an emergency dive. The crew survived. He tried to sink her, but the torpedo malfunctioned, and she wrecked her with a deck gun (she carried iron ore). He was back on Kiel on 15 September 1939.

On 8 October 1939, for his second patrol Prien had the idea to penetrate Scapa Flow without orders (which would have been perhaps denied given the risk of even attempting it) and on 14 October he managed to penetrate all defences and the primary base, albeit the Home Fleet was mostly absent. He spotted the battleship HMS Royal Oak 4000 m away, took an attack position, and opened fire with three torpedoes. The first 2 damaged the bow, severed an anchor chain, started reloading but the 3rd struck a point out of the belt, causing severe flooding. She listed to 15 degrees, with open portholes, soon submerged, then took 45 degrees and capsized within 15 minutes with 835 men aboard. Amazingly, Prien managed to leave the bay and get back to port where he became an instant celebrity as was Otto Weddingen, which sank three armoured cruisers in 1914. He was nicknamed “Der Stier von Scapa Flow” (“Bull of Scapa Flow”) which became hist CT emblem and later extended to the whole 7th U-boat Flotilla. Prien was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross by Hitler, first U-boat commander and second member of the Kriegsmarine to receive that decoration. The rest of the crew received an Iron Cross. The Knight’s Cross was awarded to chief engineer Johann-Friedrich Wessels and 1st watch officer Engelbert Endrass.

For its 3rd patrol, U-47 was at sea on 16 November 1939 from Kiel to the North Sea, rouding the British Isles for the Bay of Biscay and English Channel by the south, sinking Navasota on 5 December, MV Britta on 6 December, Tajandoen on 7 December. She was depth charged but escaped without damage.

Her fourth patrol from Wilhelmshaven started on 11 March 1940, 19 days in the North Sea and on the 25th she claimed the Danish steam merchantman Britta off Scotland, back on 29 March.

She departed for her 5th from Wilhelmshaven on 3 April, North Sea but on 19 April, fired a missed HMS Warspite, was depth charged but escaped.

In her 6th patrol from Kiel on 3 June 1940, in the North Sea, southern coast of Ireland, heading “Wolfpack Prien” and attacking Convoy HX 47, bagging SS Balmoralwood on 14 June, San Fernando on the 21st, Cathrine on the 24th, Lenda and Leticia on the 27th, Empire Toucan on the 29th, Georgios Kyriakides on the 30th, SS Arandora Star on 2 July and back to Kiel on 6 July.

The 7th patrol was north of the British Isles and North Atlantic south Iceland for 30 days, sinking 6, damaging 1: Belgian liner Ville de Mons (2 September) British Titan (4) Gro, José de Larrinaga, Neptunian (7), Possidon (9) nand damaged Elmbank (21) back on the 25th at Lorient, just acquired.

Her 8th patrol started on 14 October for 10 days, Smaging Shirak (19), sank Uganda and Wandby, damaged Athelmonarch (20) sank La Estancia and Whitford Point.

Her 9th patrol started on 3 November 1940 in the North Atlantic. She damaged Gonçalo Velho, Conch and Dunsley, sank Ville d´Arlon and was back to Lorient on 6 December.

Her 10th was also her last patrol. She was at sea from Lorient on 20 February 1941. Reported missing on 7 March, believed sunk by HMS Wolverine west of Ireland but postwar assessment underline a possible success by the Flower class corvettes HMS Camellia and HMS Arbutus.

U-48

U-48

U-48 was ordered on 21 November 1936 from Germaniawerft, Kiel, at Yard number 583. She was laid down on 10 March 1937, launched on 8 March 1939 and commissioned on 22 April 1939 at a cost of 4,439,000 Reichsmark. Her successive crews were composed of captain Herbert Schultze, Hans-Rudolf Rösing and Heinrich Bleichrodt, first watch officer Richard Schoen, second watch Otto Ites, chief engineer Erich Zürn and coxswain Horst Hofmann for her first patrol, when she left Kiel on 19 August. She was a top scorer. She operated north of the British Isles,, North Atlantic and Bay of Biscay, then west of the Western Approaches and spotted the 4,853 GRT SS Royal Sceptre, sank by deck gun on 5 September 1939. The Radio Officer transmitting “SOS” was taken prisoner and released to the lifeboats, and verified the lifeboats were provisioned with food and water. U-48 later stopped SS Browning, the crew wanted to abandon ship, but Schultze told them to return and pick up the crew of Royal Sceptre while en route to Brazil. After other inspection she sank Winkleigh on 8 September and on 11 September, Firby. She was back to Kiel on 17 September with a tally of 14,777 GRT.

Her second patrol started on 4 October, same course. She sank the French tanker SS Emile Miguet on 12 October, Heronspool and Louisiane on 13 October, Sneaton on 14 October and Clan Chisholm on 17 October and damaged by deck gun the steamer Rockpool, which replicated, she had to dive, return only to be repelled by a destroyer. Total 37,153 GRT, back on 25 October.

Third patrol: 20 November, four vessels: Swedish tanker MT Gustaf E. Reute/27 Nov., freighter Brandon 8 Dec., tanker San Alberto and the Greek freighter Germaine 15 December 1939 and back on 20 December (25,618 GRT). She departed for her 4th patrol on 24 January and sank the Blue Star Line liner SS Sultan Star and was equipped with mines she laid off St Abb’s Head. She later sank two neutral Dutch ships, a Finnish ship.

He 5th patrol started in June 1940 under KptLt. Hans Rudolf Rösingand hunted off County Donegal, sank Stancor (fish freighter from Iceland) Eros (with 200 tons of small arms from the US) and Frances Massey (iron ore). Eros however survived and was beached on Errarooey strand. She was vectored in on RMS Queen Mary and Mauretania carrying 25,000 Australian soldiers to Britain, to Cape Finisterre joining a wolfpack. On 19 June she attacked Convoy HG 34, sank SS Baron Loudoun, SS British Monarch, MV Tudor. She caught Convoy HX 49, dispersed, sank Moordrecht, Violando N. Goulandris. They carried grain for Ireland and the Gvt. protested.

U-48 was made a stop at Trondheim claimed eight ships from convoys above (Eastern Atlantic) and 5 more on her 6th patrol in August, ended at Lorient.

Her 7th patrol saw 4 kills in Convoy HX 65, 1 damaged and she was vectored south of Greenland. In September, 8th patrol, she sank SS City of Benares and sank 5 others in Convoys SC 3 and OB 213. City of Benares carried 119 children evacuated to Canada under the Children’s Overseas Reception Board initiative so captain Bleichrod was accused of war crimes postwar but eventually acquitted. This sinking ended the overseas evacuation programme. She was painted like a troop ship at the time, and the escorting British sloop HMS Dundee was sunk also.

Her 9th and 10th patrols was for 2 and 5 kills respectively. Back home at Lorient she was declared obsolete despite a winter refit. Her 11th patrol was not successful, and her final, 12th patrol saw her sinking 5 ships and the crew saw a Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross awarded by her XO, Erich Zürn.

Back to Kiel on 22 June 1941, her crew was transferred to a training flotilla in the Baltic Sea. In 1943, she was deemed unfit, laid up at Neustadt, Holstein wuth a maintenance crew, until scuttled in the Bay of Lübeck on 3 May 1945.

U-49

U-49

U49 was ordered to Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft AG in Kiel as hull yard 584, ordered on 21 novembre 1936, keel laid down on 15 septembre 1938, launched on 24 juin 1939 and commissioned on 12 août 1939 for a cost of 4 439 000 Reichsmark. She initially served until early 1940 as part of the “Wegener” Flotilla. She conducted her first combat patrol from Kiel on November 9, 1939, under command of Kapitänleutnant Kurt von Gossler for training in pack off the coast of Portugal, with U-41 and U-43. They spotted and attacked a convoy, U-49 sinking a 4,258-ton merchant ship northwest of Cape Ortegal. Destroyers counterattacked and damage her with DCs. She was back to Kiel on November 29, 1939.

Her second patrol from February 29, 1940 from Kiel ended six days later after a cruise in the North Sea, no spots, not kills. She entered Wilhelmshaven for maintenance on March 5, 1940.

She departed Wilhelmshaven on March 11, 1940 for a third patrol to the Norwegian coast, 19 days at sea, no spot, no kill, back on March 29, 1940.

Her 4th patrol from Wilhelmshaven started on April 3, 1940 and in Operation Hartmut, she ws to protect the flanks of the the German landings in Norway. She joined U-boat Group No. 5 NE of the Shetland Islands and was ordered to proceed to Narvik. On 15 April 1940, she was caught surfaced near Harstad, and attacked by guns and depht charges from the British destroyers HMS Fearless and HMS Brazen. 42 crew members survived.

U-50

U-50

U 50 was ordered at Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft AG in Kiel as hull 585 on 21 november 1936, laid down on 3 novembre 1938, launched on 1st november 1939 and commissoned on 12 December 1939 for 4,439,000 Reichsmark. She was integrated after training in the Seaboat Flotille “Wegener”. She carried out her first combat patrol from Heligoland on February 6, 1940, under command of Kapitänleutnant Max-Hermann Bauer, for the North Atlantic and coast of Portugal. She spotted and sank four merchant ships for 16,089 tons. When attacking the fourth ship, she lost her diesel engine. Repairs were impossible so she returned to Kiel on March 4, 1940. In her second patrol, she took part in Operation Hartmut, to protecting German landings in the invasion of Norway. Attached to Group No. 5, with U-47 (Günther Prien Flotilla) she left Kiel on April 5, 1940 but crossed a minefield and sank on April 6, 1940 north of Terschelling. Her exact position remains unknown. All 44 crew members went down with her. These mines had been laid by HMS Express, Esk, Icarus, and Impulsive on March 3, 1940 as British Minefield No. 7. Well placed in the path back to port, they also likely causes other U-Boat losses.

U 50 was ordered at Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft AG in Kiel as hull 585 on 21 november 1936, laid down on 3 novembre 1938, launched on 1st november 1939 and commissoned on 12 December 1939 for 4,439,000 Reichsmark. She was integrated after training in the Seaboat Flotille “Wegener”. She carried out her first combat patrol from Heligoland on February 6, 1940, under command of Kapitänleutnant Max-Hermann Bauer, for the North Atlantic and coast of Portugal. She spotted and sank four merchant ships for 16,089 tons. When attacking the fourth ship, she lost her diesel engine. Repairs were impossible so she returned to Kiel on March 4, 1940. In her second patrol, she took part in Operation Hartmut, to protecting German landings in the invasion of Norway. Attached to Group No. 5, with U-47 (Günther Prien Flotilla) she left Kiel on April 5, 1940 but crossed a minefield and sank on April 6, 1940 north of Terschelling. Her exact position remains unknown. All 44 crew members went down with her. These mines had been laid by HMS Express, Esk, Icarus, and Impulsive on March 3, 1940 as British Minefield No. 7. Well placed in the path back to port, they also likely causes other U-Boat losses.

U-51

U-51

U 51 was ordered on 21 November 1936 to Germaniawerft AG, Kiel as yard number 586, laid down on 26 February 1937, launched on 11 June 1938 and commissioned on 6 August 1938 at a cost of 4,439,000 Reichsmark under Kapitänleutnant (Kptlt.) Ernst-Günther Heinicke. She was deployed from Kiel and took part in four combat patrols with the 7th U-boat Flotilla from 6 August 1938. Her 1st patrol started on 17 January 1940, leaving Kiel, crossing the North Sea, negotiating the ‘gap’ between Orkney and Shetland Islands. 45 nautical miles (83 km; 52 mi) west of Rockall she sank the Gothia on 22 January. Then she south down the west coast of Ireland and encountered and sank Eika, west of the Scilly Isles on the 29th. She ended in Wilhelmshaven on 8 February.

In her second patrol she was caught surfaced and torpedoed, but missed by the French submarine Orphée on 21 April 1940. She then headed parallel to the Norwegian coast but made no kills, went back home.

Her third foray was in the Atlantic in the GIUK gap (Faroe-Shetland) from Kiel on 6 June 1940. She spotted and sank the Saranc on 26 June 270 nm WSW of Lands End and later sank the Q-ship HMS Edgehill two days later. The latter was a good kill, she was a real danger with her nine 4-inch guns and four torpedo tubes, extra ballast for better buoyancy so she needed three torpedo hits to do down over an hour. He crew survived.

For her 4th and last patrol she departed Kiel on 9 August 1940, sank the Sylviafield 190 nm (350 km; 220 mi) WNW of Rockall (36 survivors). U 51 was sunk by a torpedo from the British submarine HMS Cachalot in the Bay of Biscay, on 28 August 1940. No survivors.

U-52

U-52

U-52 was ordered on 15 May 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel as Yard number 587 laid down on 9 March 1937, launched on 21 December 1938 and commissioned on 4 February 1939 at a cost of 4,439,000 Reichsmark. First skipper was Kapitänleutnant (Kptlt.) Wolfgang Barten. She left Kiel on 19 August 1939, crossed the North Sea for the Atlantic via the GIUK gap and reached the most southerly point on 1 September the day of war. She bagged no ship and was back home soon after.

She later made series of short trips from Kiel to Helgoland and Wilhelmshaven, and left Helgoland on 27 February 1940 for Wilhelmshaven on 4 April. That counted for a 2nd sortie but she made no kill. For her 3rd patrol she met no success so her skipper crossed the North Sea, swept the area between the Faroes and Shetlands.

She moved to the west of Ireland, spotted and sank The Monarch, 60 nm west of Belle Ile, Bay of Biscay, 19 June 1940. Next she crossed paths with Ville de Namur, which carried large wooden structures on deck, stables for horses. She was sunk and went down in 5 minutes with all a cargo of cavalry. She sank Hilda on 21 June, Thetis A on 14 July, with two torpedoes, the first was a dud. In her 5fth patrol she bagged SS Geraldine Mary and Gogovale on 4 August 1940, 300 nm WSW of Bloody Foreland, County Donegal but was badly damaged by the escorts and limpled back to port for 4 months repairs. Her 6th patrol saw her skinking the Tasso and Goodleigh on 2 December 1940, 360 nnm west of Bloody Foreland.

For her 7th patrol she departed for the mid-Atlantic, sank the Ringhorn on 4 February 1941, and Canford Chine on the 10th, 165 nm southwest of Rockall.

In her 8th patorl she sank the Saleier on 10 April 1941, which went down in 15 seconds but the crew was well drilled, and all 63 survived.

Her last kill of the war was Ville de Liège (Belgian) 700 nm east of Cape Farewell in southern Greenland on 14 April. Afterwards she was transferred to the Baltic, had a collection of captains and used to train new crews for the Type VIICs that were built like sausages. She was eventually decommissioned on 22 October 1943 and left in reserve with a skeleton crew until cauht by an air raid of the Royal Air Force at Danzig 3 May 1945. She was raised and BU in 1946–7.

U-53

U-53

U-53 was ordered on 15 May 1937 to Germaniawerft, Kiel as Yard number 588, laid down on 13 March 1937, launched on 6 May 1939 and commissioned on 24 June 1939 at a cost of 4,439,000 Reichsmark. After working up under command of Oberleutnant zur See (Oblt.z.S.) Dietrich Knorr she started her 1st patrol on 29 August 1939 under command of Ernst-Günter Heinicke and Ernst Sobe, commander of the 7th (“Wegener”) Flotilla. She bagged two British ships, the tanker SS Cheyenne and freighter SS Kafiristan. For her 2nd patrol under Heinicke from 21 October she had no kills. She was reordered to join with U-25 and U-26 and penetrate the Strait of Gibraltar to raid Allied shipping in the Mediterranean. But given the strong patrolling British forces at the straits, Heinicke did not attempted the crossing, and was retransferred to protect the merchant raider German auxiliary cruiser Widder returning to Germany.

The apparent prudence of Heinicke did not pleased Dönitz which had hime sacked and replaced by Harald Grosse for her final war patrol (something that saved him). U 53 was underway 2 February 1940. Grosse sank six ships (21,230 gross GRT) including the neutral Banderas, straining relations with Spain. On 23-24 February she was spotted, engaged and sunk by depth charges from HMS Gurkha west of the Orkney Islands. No survivors.

U-54

U-54

U-54 was initially ordered on 16 July 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel as Yard number 589, laid down on 13 September 1938, launched on 15 August 1939 and commissioned on 23 September 1939 at a Cost of 4,439,000 Reichsmark. Her first skipper was Kapitänleutnant (Kptlt.) Georg-Heinz Michel under the 7th U-boat Flotilla until 30 November 1939, then Korvettenkapitän (K.Kapt.) Günter Kutschmann on 5 December, completing the training programme on new year’s eve. She made only a single war patrol from 1 January 1940, North Sea, no successes but reported missing after failing to comminicate as prearranged on 20 February. Likely cause is a mine from mine barrages Field No. 4 or Field No. 6 laid down by HMS Ivanhoe and Intrepid by early January 1940. Part of one of her torpedoes was found on 14 March 1940 by V 1101 Preußen nearby.

U-55

U-55

U-55 was ordered on 16 July 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel, as Yard number 590, laid down on 2 November 1938, launched on 19 October 1939 and commissioned on 21 November 1939 at a cost of 4,439,000 Reichsmark under command of Kapitänleutnant (Kptlt.) Werner Heidel. She made just one single war patrol from 16 January 1940 under Heidel which previously sunk two ships on U-7. She spotted herself and sank four small freighters sailing independently and preyed on convoy OA-80G from 29 January, sank two ships but faced a well concerted attack from escorts, supported by a Sunderland flying boat from 228 Squadron. A deadly mix. She had to face series of depth charge attacks, and ws so badly damaged her captain decided to surface and start a running gun battle, until the deck gun jammed. She was abandoned, and went down with her skipper still aboard, after scuttling charges were apparently activated. The crew was rescued. The sloop HMS Fowey, DD HMS Whitshed, French destroyers Valmy and Guépard and Sunderland were all colectively awarded the kill.

U-73

U-73

U-73 was ordered on 2 June 1938 from Vegesacker Werft as Yard number 1 (first ever U-Boat from this yard), laid down on 5 November 1939, launched on 27 July 1940 and commissioned on 30 September 1940. 15 patrols, 8 ships, 4 warships, she was one of the most successful in class, but she was sunk on 16 December 1943, by USS Woolsey and Trippe (16 dead).

To come in a future update.

U-74

U-74

U-74 was ordered on 2 June 1938 to Vulkan of Bremen-Vegesack as Yard number 2, laid down on 5 November 1939, launched on 31 August 1940 and commissioned on 31 October 1940 at a cost of 4,760,000 Reichsmark. She conducted eight patrols, sinking 4 ships (25,619 GRT) damaging two more for 11,525 GRT and was in three wolfpacks. She was sunk on 2 May 1942 by HMS Wishart and HMS Wrestler. To come in a future update.

U-75

U-75

U-75 was ordered on 2 June 1938 from Bremer Vulkan, Bremen-Vegesack, Yard number 3, laid down on 15 December 1939, launched on 18 October 1940 and commissioned on 19 December 1940 at a cost of 4,790,000 Reichsmark. She saw 5 patrols, sank 9 ships, and was Sunk by HMS Kipling on 28 December 1941

To come in a future update.

U-76

U-76

U-76 was ordered on 2 June 1938 from Vegesacker Werft, Bremen-Vegesack as Yard number 4, laid down on 28 December 1939, launched on 3 October 1940 and commissioned on 9 December 1940.

She made only a single patrol and was sunk on 5 April 1941 by HMS Wolverine and Scarborough. 42 were rescued. More To come in a future update.

U-83

U-83

U 83 was ordered on 9 June 1938 to Flender Werke, Lübeck as Yard number 291, laid down on 5 October 1939, launched on 9 December 1940 and commissioned on 8 February 1941.

U 83 was ordered on 9 June 1938 to Flender Werke, Lübeck as Yard number 291, laid down on 5 October 1939, launched on 9 December 1940 and commissioned on 8 February 1941.

She was not very sucxessful: In 12 patrols she sank 5 ships totalling 8,425 GRT and a single auxiliary warship, Q-ship HMS Farouk (96 GRT). She also damaged a 2,590 GRT, damaged the fighter catapult ship HMS Ariguani, 6,746 GRT. She was sunk on 4 March 1943 (with all hands) southeast of Cartagena by a RAF Hudson bomber from 500 Squadron, dropping three charges right on target.

U-84

U-84

U-84 was ordered on 9 June 1938 from Flender Werke AG, Lübeck as Yard number 280, laid down on 9 November 1939, launched on 26 February 1941 and commissioned on 29 April 1941.

She carried out 8 patrols, 6 ships sunk one damaged. She was one of the rare in class to operate in the Gulf of Mexico and under Captain Uphoff, she torpedoed the freighter Baja California there on 19 July 1942. She sank in shallow waters 60-70 nm southwest of Fort Myers in Florida. U-84 was sunk on 7 August 1943 in the North Atlantic by a Mk 24 homing torpedo from a B24 Liberator, all hands lost.

U-85

U-85

U-85 was ordered on 9 June 1938 from Flender Werke, Lübeck as yard number 281, laid down on 18 December 1939, launched on 10 April 1941 and commissioned on 7 June 1941.

She departed Trondheim in Norway on 28 August 1941 for her first patrol, sank the Thistleglen on 10 September northeast of Cape Farewell, Greenland. She docked at St. Nazaire on 18 September but not as new homeport. For her 2nd patrol she inded started and finished in Lorient, no kills. In her third, she sank the Empire Fusilier southeast of St. Johns, Newfoundland, after a seven-hour chase on 9 February 1942. Her 4th patrol was from St. Nazaire on 21 March 1942. She sank the Norwegian freighter Christen Knudsen off New Jersey, USA on 10 April. She also took part in the wolfpacks Markgraf on 1 – 11 September 1941, Schlagetot from 20 October to 1 November 1941, Raubritter from 1 – 17 November 1941 and Störtebecker from 17 to 22 November 1941. She was Sunk by USS Roper on 14 April 1942.

U-86

U-86

U-86 was ordered on 9 June 1938 from Flender Werke, Lübeck as Yard number 282, laid down on 20 January 1940, launched on 10 May 1941 and commissioned on 8 July 1941 at a cost on 4,714,000 Reichsmark. She trainied with 5th U‑boat Flotilla (Jul–Aug 1941), assigned to 1st U‑boat Flotilla from 1 September 1941 until her loss. She performed eight combat patrols; first began 7 Dec 1941 from Kiel, last ended in loss on 29 Nov 1943 east of the Azores. She sank 3 merchant ships (total ≈9,614 GRT); damaged 1 vessel (≈8,627 GRT).

2nd patrol: Damaged British Toorak (16 Jan 1942), sank Greek Dimitrios G. Thermiotis (18 Jan 1942). 4th patrol (Aug 1942): Sank American schooner Wawaloam via deck gun. 6th patrol (Mar 1943): Sank Norwegian Brant County on 11 Mar 1943. She participated in ten operations: Zieten, Wolf, Natter, Westwall, Neuland, Dränger, Seewolf, Schill 2, Weddigen.

She was lot on 29 November 1943 east of the Azores by Depth charges from British destroyers HMS Rocket and HMS Tumult. All 50 crew lost – no survivors. More to come in a future update.

U-87

U-87

U-87 was ordered on 9 June 1938 from Flender Werke AG as yard number 283, laid down on 18 April 1940, launched on 21 June 1941 and commissioned on 19 August 1941. She was assigned to the 6th U-boat Flotilla on 1 Dec 1941 after training. She departed for five offensive patrols between December 1941 and early 1943. Sehe sank 5 Allied merchant vessels totaling ~38,014 GRT

Notable successes included the tanker Cardita (31 Dec 1941) and British freighter Port Nicholson (15 June 1942) — the latter carried massive quantities of platinum.

Wolfpack participation: Ziethen, Westwall, Iltis, Delphin, Rochen. On 4 March 1943 she was lost on the North Atlantic, west of Leixões (Portugal), attacked with depth charges by Canadian warships HMCS Shediac and HMCS St. Croix. All 49 crew members were lost. More to come in a future update.

U-99

U-99

U-99 was ordered on 15 December 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel at Yard number 593, laid down on 31 March 1939, launched on 12 March 1940 and commissioned on 18 April 1940.

She completed eight patrols between June 1940 and March 1941. She sank 38 merchant ships (≈244,658 GRT), damaged 5 more and captured 1 prize vessel. Tactical innovation: Kretschmer employed daring nighttime surface attacks inside convoys, often needing just one torpedo per ship—earning the adage “one torpedo … one ship”. On her 2nd patrol (27 Jun – 21 Jul 1940): Sank 6 ships and captured the Estonian vessel Merisaar, which was later bombed by Luftwaffe. Convoy actions: Successfully struck HX‑53 (July 1940), OB‑191, SC‑7, OB‑256, HX‑79, among others

Final patrol: 22 Feb – 17 Mar 1941. On 17 March 1941, while attacking Convoy HX‑112 southeast of Iceland, U‑99 was detected by HMS Vanoc’s Type 286 radar (one of the first radar detections of a U‑boat). She was subject to depth charges and then rammed and sunk by Vanoc (and assisted by HMS Wrestler). 3 crew killed, 40 survivors (including Kretschmer) who became POWs

She was sunk on 17 March 1941 by HMS Walker southeast of Iceland.

U-100

U-100

U-100 was ordered on 15 December 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel, Yard number 594, laid down on 22 May 1939, launched on 10 April 1940, commissioned on 30 May 1940. Patrol 1: Shadowed convoys OA‑198 & OA‑204. Patrol 2: Struck HX‑72; sank 7 ships (50,340 GRT) with famously precise, convoy-penetrating attacks—heavy Wolfpack success. Later operations included attacks on HX‑79, SC‑7, SC‑11, OB‑256, etc. Final Patrol: On 17 Mar 1941, while closing convoy HX‑112, U‑100 became the first U‑boat detected by radar (HMS Vanoc’s Type 286), then rammed and sunk—6 survivors, 47 lost

U-101

U-101

U-101 was ordered on 15 December 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel as Yard number 595, laid down on 31 March 1939, launched on 13 January 1940 and commissioned on 11 March 1940. 16 Jun 1940: Sank Wellington Star west of Spain; used torpedo + deck‑gun; crew questioned survivors. 31 May 1940: Sank Orangemoor from convoy HG‑31F—8,150 t of iron; escort dropped ~41 depth charges over 8 hrs; U‑boat survived.

U-101 was ordered on 15 December 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel as Yard number 595, laid down on 31 March 1939, launched on 13 January 1940 and commissioned on 11 March 1940. 16 Jun 1940: Sank Wellington Star west of Spain; used torpedo + deck‑gun; crew questioned survivors. 31 May 1940: Sank Orangemoor from convoy HG‑31F—8,150 t of iron; escort dropped ~41 depth charges over 8 hrs; U‑boat survived.

Aug–Sep 1940 Patrols: Sank Ampleforth, Elle, Efploia, Saint‑Malo; participated in wolfpack attacks on convoys SC‑7 and SC‑48; sank/damaged multiple merchant ships. Totals: Sunken 22 merchant ships + 1 warship (~1,190 t); damaged 2 others. Served as a training boat (1942–43) in the Baltic. She was decommissioned on 22 October 1943. Scuttled 3 May 1945. Took paert in the Wolfpacks: Rösing, West, Grønland, Reissewolf.

U-102 (1939)

U-102 (1939)

U-102 was ordered on 15 December 1937 from Germaniawerft, Kiel, Yard number 596, laid down on 22 May 1939, launched on 21 March 1940 and commissioned on 27 April 1940. First patrol: Departed Kiel 22 Jun 1940. Sank British merchantman Clearton (5,219 GRT) on 1 Jul, part of convoy SL‑36 west of Ushant. Sunk the same day (1 Jul 1940) by depth charges from British destroyer HMS Vansittart southwest of Ireland; all 43 hands lost. Vansittart rescued 26 survivors from the Clearton.

Gallery

Read More

uboat.net/types/viib.htm

uboat.net u45.htm

u-boot-archiv.de/ u45.html

uboat.net u47.htm

uboatarchive.net/U-47

donhollway.com/scapaflow

en.wikipedia.org/ Type_VII_submarine

commons.wikimedia.org Type_VIIB_submarines

en.wikipedia.org List_of_U-boats_of_Germany

uboatarchive.net U47_mods.pdf

u-boote.fr/charact.htm

VIIC

uboatarchive.net/ Manual.htm

uboatarchive.net/ U-570 British Report

Möller, Eberhard; Brack, Werner (2004). The Encyclopedia of U-Boats.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships 1815–1945

Helgason, Guðmundur. U-Boat War in World War II

Busch, Harald (1955). U-Boats at War.

Rossler, Eberhard (1981). The U-Boat.

Stern, Robert C. (1991). Type VII U-boats.

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-47

Type VII by Marek Krzysztalowicz

U-Boote by Jean-Philippe and Dallies-Labourdette

The U-Boat Type VII by Robert Cecil Stern

Type VII U-Boat (Anatomy of the Ship) by David Westwood

Caractère Edtions: LOS! n°61 TYP VIIB U-48 link

Busch, Rainer; Röll, Hans-Joachim (1999). German U-boat commanders of World War II : a biographical dictionary. Greenhill Books NIP

Busch, Rainer; Röll, Hans-Joachim (1999). Deutsche U-Boot-Verluste von September 1939 bis Mai 1945. Hamburg, Berlin, Bonn: Mittler

Gröner, Erich; Jung, Dieter; Maass, Martin (1991). U-boats and Mine Warfare Vessels. German Warships 1815–1945. Vol. 2. Conway Maritime Press.

Kemp, Paul (1999). U-Boats Destroyed – German Submarine Losses in the World Wars. London: Arms & Armour

Model Kits:

shipwrightshop.com

modelingmadness.com

super-hobby.com/

howesmodels.co.uk/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign