The best “washington” cruiser?

Algérie was the last French heavy cruiser. She was also -as many authors agrees- certainly one of the very best, if not the best “Washington cruiser”. Meaning, built within the Washington treaty limitations (1922). She proceeded from two earlier heavy cruisers designs but took a radically new approach and ended as a finely balanced one.

But she was also the only one of her class because of global tonnage limitations, and unfortunately a ship which ended scuttled in November 1942.

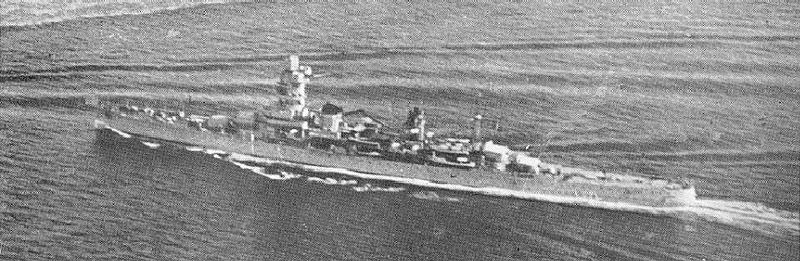

Colorized photo by Hirotoko Jr. – From ONI identification book USN

The Washington treaty limits

The Washington treaty (signed by all major naval powers in 1922) was the embodiement of political power on the military and especially the navy. The needs of the navies were simply ignored or partially obtained after a wave of compromises.

The truth is this treaty left most nation’s own navy staff and some politicians deeply frustrated. But tax-payer side and lifting all egos apart, it helped also contain a dangerous trend in naval spending, towards even more larger and more powerful capital ships. It’s easy to see this mad race in 1917-18 projects: 50,000+ tons warships armed with eight to twelve 457 in guns…

The treaty not only stop this tonnage-wise per ship (on a qualitative level), on the nation’s authorized global tonnage and per-type tonnage, but also imposed a ten years moratorium. Seven years after an historical financial crisis at Wall street would have condemn any or these policies anyway.

France and naval treaties

France in particular was left unsatisfied by the treaty, which left her with 175,000 tons globally, the same as Italy whereas she estimated having more needs because or her more expansive colonial empire. The other nation, for the same reason, that felt frustrated was Japan, whose ambition was parity with the two “greats”, RN and USN, to built her empire.

Now some French policitians however saw these limitations salutary for budgetary concerns. And indeed, it was realism through and through: France has not remotelly close the budget to fill her ambitions, barely enough even to reach the limitations. Her huge ww1-era “prototype” fleet was 80% absolete and of dubious military value. The washington treaty would make this interwar a playground for new naval theories and help France securing “new blood” for her navy, with almost all new classes of ships and produced a compact, homogeneous, modern and well-balanced navy, amidst political turmoil and the 1929 crisis, but thanks to the stable policy of two visionary ministers, Georges Leygues and François Pétrie.

The shadow of the “young school” gabegie was still lurking over their shoulders.

Neither the following Geneva conference of 1927 and 1932 or the London treaty of 1930 made an impact on these policies, but the annoucement of the rearmment of Germany from 1933, quite obvious by 1935, made France denouncing the treaties and retired, just as Japan.

The 120,000 tons limited agreed in the Anglo-German naval treaty of 1935 would not changed the outcome and soon after Italy retired also whereas the treaty attempt at London the next year ended as a failure. But the 1929 crisis consequences had shattered old Europe, and amidt political turmoil in France, construction of new cruiser was stopped altogether.

Only the St Louis was projected in 1938, yet another radically new design (St Louis class) that borrowed to the popular concepts of the time, a 3×3 main artillery configuration among others, but largely inspired by the Algérie in terms of protection and general balance.

Algérie underway in 1943, USN photo for ONI identification book

Towards a better heavy cruiser design

Cruisers were no exceptions: The last ones were built in 1901-1902. 1912 projects has been scrapped. In 1922-23, came the Primauguet of a brand new design, followed by the heavy cruiser series Duquesne and Suffren, six ships relatively similar and also sharing the same issue: On the always true triptych speed/armament/protection, the cursor was set on the first two.

Also typical of the 1920’s and early 30′ fad of Mediterranean “tin-clad cruisers”, these ships lacked also good AA. The Algérie tried to set the cursor right in the center of the tryptich, therefore more towards protection, while sacrificing part of the speed and through compromised.

In the end it was a very well balanced design. The best France ever produced for an interwar cruiser and certainly one of the best at that time. With more time, the St Louis class then in construction would have beaten this probably. They were closer to the American Baltimore, no longer a washington cruiser by any margin in 1942.

Algérie circa 1936-37 – ONI naval recoignition USN intelligence plate, 1943

Design and Development of the Algérie

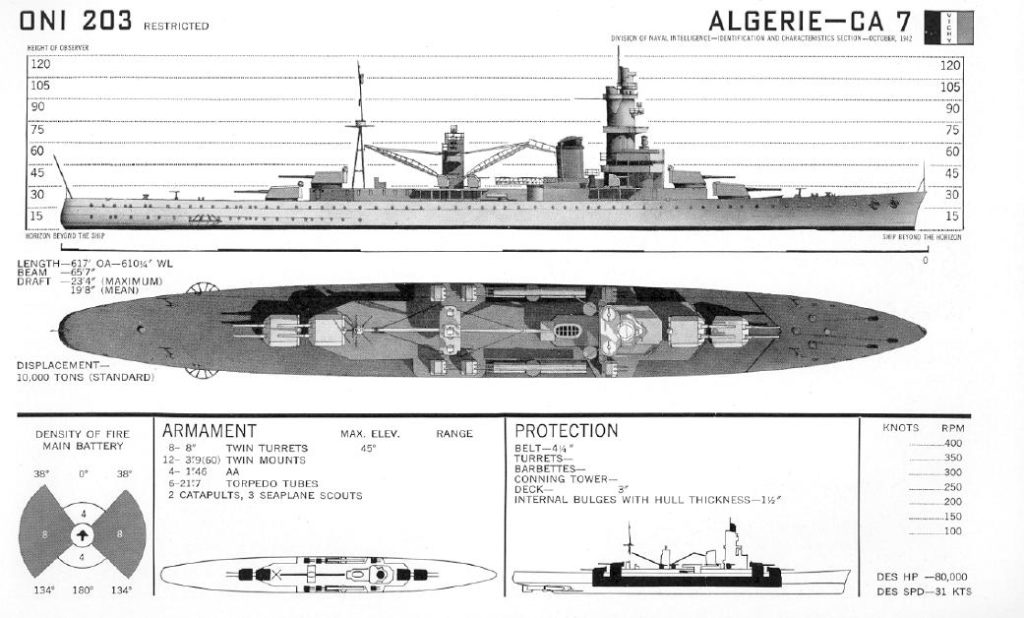

ONI- naval recoignition USN intelligence plate of the Algerie

Overall design

As it was said, The Algérie came after a series of cruisers criticized for their cruel lack of protection and too light construction, better suited for th Mediterranean than the Atlantic. The lack of range and AA could be added to the mix.

A new type of heavy cruiser subjected to Washington tonnage was studied under a new direction. This time it was an attempt clearly focused towards protection. Algérie was voted by the parliament under the provisional code PN 141, part of the 12 january 1930 law also funding the minelayer cruiser Emile Bertin and the famous super-destroyers of the Le Fantasque class.

The final design approved resulted in more modest dimensions, a flush-deck hull, revised interior designs, but a near-unchanged speed and armament (the true miracle of this design) in favor of excellent overall protection. But for the naval staff, she was mostly built in response to the Italian Zara-class cruisers, which themselved were better protected than the Trento. So the Algérie as a fitting response has to incorporater even better armour than not only previous French cruisers, but the Zara class themselves.

Her dimensions were the result of weight-saving measures, and this included significant savings by scrapping the traditional forecastle for a simpler and smoother flush deck, which prow was just as high. In addition, the hull was 186.2 m (611 ft) by 20 m (66 ft), by 6.15 m (20.2 ft) whereas the Suffren was considerably longer and deeper at 194 m (636.48 ft) by 20 m (65.62 ft) and 7.3 m (23.95 ft) draught. However both classes were a close match in terms of displacement: 10,000 tons (standard) and 13,641 tons (full load) for the Algérie and the same as standard but 12,780 tonnes (fully loaded).

So the Algérie was 860 tons heavier at full load, all of it was armour, in reality even more given the reduced size of the hull. In reality given the steel saved by shorter dimensons adnd more compact machinery, almost one meter saved in draught, which was considerable. So total weight of the armour was closer to 1500 tons, the displacement of a destroyer.

WoW’s rendition of the Algérie

Propulsion

To move these 13,000 tons fully loaded, Algérie can count on four-shaft Rateau-Bretagne SR (gearing with simple reduction) and Brown Boveri mixed geared turbines fed by six Indret boilers (with Penhoët burners), rated for a total of 84,000 shp (63,000 kW).

This was slightly less than the 3-shaft Rateau-Bretagne SR geared turbines rated for 90,000 shp on the Suffren, yet the latter achieved 32 knots (36.82 mph; 59.26 km/h). What was important however, was the fact some room was lost as the four turbines were all roomed independantly, so in case of a water gush, only one was flooded, allowing the ship to escape to safety.

However, Suffren had a range of 4,500 nautical miles while Algérie still maintained a top speed of 31 knots (57 km/h), so only conceiding a knot, but with a range of 8,700 nautical miles (16,110 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h), almost double.

This feat was achieved by partly using fuel tanks as an additional protection rather than seawater, and better internal arrangement, as well as the space gained by using slighlty smaller turbines. This range was a welcome addition also for Atlantic operations, the intended role of the new cruiser class.

Armament

The main armament of the ship was four twin turrets housing 203mm/55 Modèle 1931 naval guns. They used the same ammunition as the 203mm/50 Modèle 1924 and were similar except for the longer barrel, hence a better muzzle velocity at 840 metres per second (2,800 ft/s). On Suffren these were the latter, allegedly derived from older ww1-era 240 mm railway guns. These Modele 31 used separate charges and shell and the APC M1936 weighted 134 kilograms (295 lb). The gun breech block was of the same earlier Welin model, with a rate of fire of abot 4-5 RPM. Maximum firing range was 31,000 m (34,000 yd) at 45° elevation.

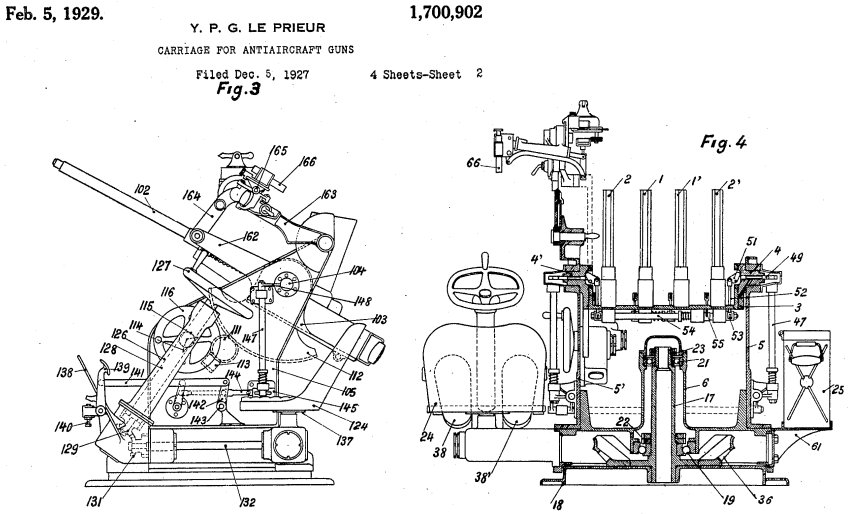

The secondary battery comprised twelve 100 mm/45 guns in six twin mounts, quite an improvement over the Canon de 90 mm Modèle 1926 used by the Suffren (which in addition carried eight single mounts). That was quite an improvement, still, fire direction was limited as well as the rate of fire. The AA battery comprised eight 37 mm (1.5 in) AA guns in four twin mounts. The already old Canon de 37 mm Modèle 1925 was a standard, used on most French cruisers and battleships.

Semi-Automatic (hand-fed with cartridge boxes), it can elevation -15° to +80° and had a 15-21 rpm, the lowest of all contemporary AA guns. By comparison the Italian Breda was 60-120 rpm and the German 3.7 cm Flak 18/36/37/43, 150 rpm, the Bofors 115-120 rpm. Its muzzle velocity was only 810 m/s (2,700 ft/s) and range 5.4 km (3.4 mi) at +45° up to 7 km (4.3 mi) at +45°. From 1941, the ship had sixteen 37 mm in twin mounts.

Algérie was also given sixteen 13.2 mm (0.52 in) AA heavy MGs in quadruple mounts and from 1941, this was bring to thirty-six 13.2 mm HMGs.

Also for close-quarter she was fitted with six 550 mm torpedo tubes in two triple banks on the sides.

The 13.2 mm model was the old Hotchkiss M1929 machine gun, air-cooled, which had a 450 rounds/min cycle, a muzzle velocity of 800 m/s (2,625 ft/s) and was fed by 30-round box magazines.

This model was also used by the Japanese and Spanish Navies, and was tried by Italy as well. But overall this AA cover had many gaping holes, between a slow 100 mm and 37 mm, and the very close-quarter 13.2 mm, which lacked punch and range.

These mounts were all replaced on French ships of the FNFL which went through an American refit, using the standard 20 mm Orelikons and 40 mm Bofors instead. For reconnaissance she also had three Loire-Nieuport 130 seaplanes, 1 catapult which were removed in 1941 while she later gained a radar.

The main tower was quite high and contained all the necessary detection and direction organs of the ship. The main telepointing turret or upper platform on top of the tower carried the telescoping turret for the main artillery, with a 5-meter rangefinder and two smaller telepointing turrets for AA artilley, each with a 3m rangefinder. With staff and all equipment, the main turret alone weighed 10.5 tons and the secondary turrets 5.5 tons.

Below, The Admiral’s Control bridge was originally called the “Headlamp Control Platform” but developed to house the admiral and had a serie of squared windows and doors to access the platform.

This level comprises the navigation shelter, reduced transmission and operations PC and two gyroscopic compass repeaters/taximeters.

The remote control station of the rear axial projector as well as the lookout stations were replaced on the intermediate gateway and the signaling projectors installed on the intermediate bridge, placed in front of the Admiral’s platform. The main bridge was below, in two stage behind the ‘Y’ turret.

The upper bridge, above the main turret, The lower bridge, housed the captain’s bridge with all the usual ship command organs and a map room and communication room behind. It was crossed by the main blockhaus with a repeat of all essential command features. The lower, or intermediate bridge, included the Admiral navigation shelter under the commander’s naval shelter, still with an unobstructed view of the bow and housed the central operations, transmissions and cipher office. On the CT’s back was installed the telegraphic station and a large maps room for the admiral watchmen restroom.

Protection

By far, the best aspect of the ship was its armour, comprising a main belt 120 mm (4.7 in) strong, transverse bulkheads 70 mm (2.8 in) thick, longitudinal bulkheads 40 mm (1.6 in) thick.

The subdivision was provided by sixteen main transverse bulkheads rising from the bottom to the upper deck. These transverse partitions closed completetly any circulation from the bottom to the main deck (machines roof and boiler rooms).

Their main deck was 80 mm (3in-1in) and below in the interdeck bulkheads were pierced with watertight doors. They contributed to the sturdiness of the ship, since their amounts connect the elongated and coamings of the upper decks with reinforcement bars.

The turrets faces were 95 mm (3.7 in), and 70 mm (2.8 in) on the sides and roofs. The conning tower had a 70 mm top and 95 mm walls (2.8 to 3.7 in). There was also an internal torpedo bulkhead, about 30 mm thick, and great compartimentation which acted as additional safe cells.

Compared to that, the previous Suffren were made in paper, with a belt 50 mm (2.0 in) to 54 mm (2.1 in) up to 60 mm (2.4 in) thick depending on the ships, a main armoured deck 25 mm (0.98 in) thicks, and the turrets and conning tower protected by 30 mm (1.2 in). Your authentic “tin-clad cruiser”.

About the new St Louis class (1938)

World of Warships what-if rendition of the St Louis

Algérie inspired the construction of new heavy cruisers to be launched when the limitations of the Washington Treaty would have expired. In effect, these were to reach 14 to 15,000 tons standard (up to 20,000 tons fully loaded), or 5000 more than the limit. Other navies were beginning to study such cruisers, including the United States Navy.

The St. Louis were therefore very close to the Baltimore design, with a same arrangement of three triple turrets. The larger dimensions were intended to improve active protection (AA) and passive protection (more armour and compartimentation) while the larger hull allowed to double to power at about 130,000 hp, regaining two knots.

They were scheduled to replace in 1943 the Duguay-Trouin class (1923) and were approved on April 1, 1940. However due to wartime urgency, their construction was never ordered. Their AA has a well-cleared arc of fire since the St Louis class were to use the same “mack” or “mast-stack”, characteristic of the Richelieu, for the benefit of additional deck and aerial space.

The guns would have been either of the same model as Algérie or an improved model with a longer barrel and reworked breech block for improved rpm. However, the AA battery was pretty much the same as Algérie, and two planes were carried, no radar at that point.

Her details were as followed:

Displacement: 14,470 t. standard -17,620 t. at full charge

Dimensions: 202 m long, 20 m wide, 5.80 m draft.

Powerplant: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 6 Indret boilers, 130,000 hp.

Top speed: 34 knots

Amour: Up to 210 mm turrets and CT, 90 mm decks, battery, 60-70 mm internals.

Armament: 9 x 203 mm (3 × 3) – New 1940 model, 8 x 100 mm (4 × 2), 8 x 37 mm (4 × 2), 16 x 13.2 mm AA HMGs (4 x 4), 3 aircraft

Crew: 760

Rendition of the St Louis class cruisers by the author.

The Algérie in action

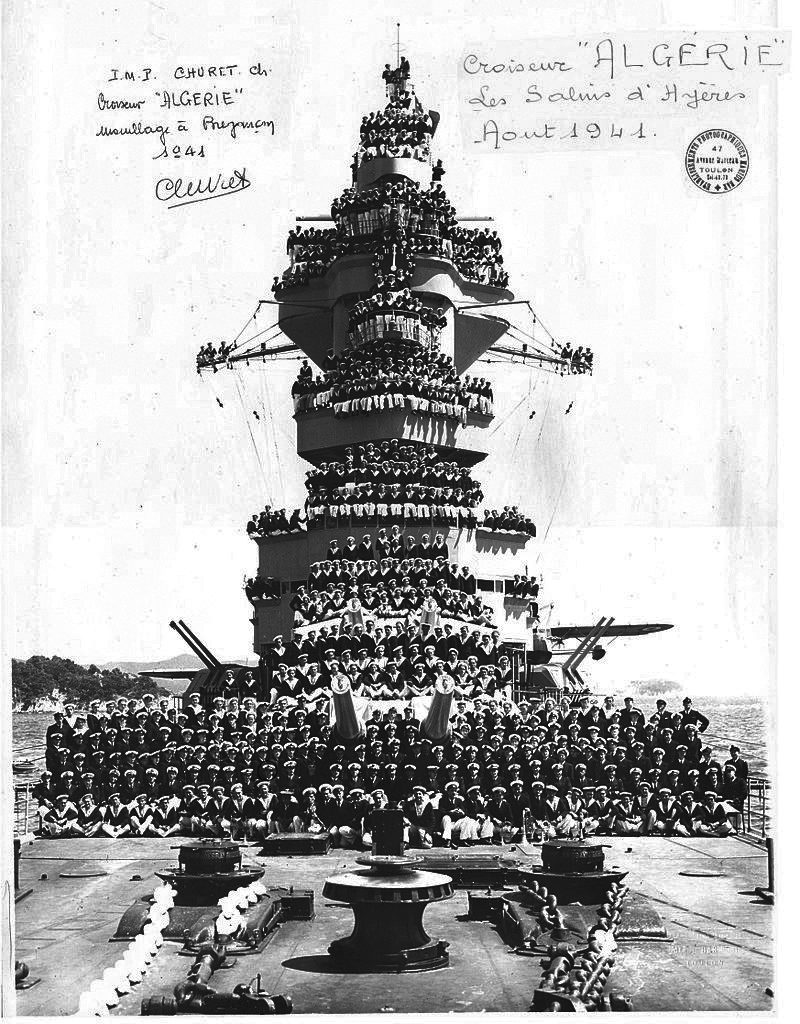

Algérie and crew posing in 1941 at Fort de Brégançon, Les Salins d’Hyères, French riviera. src. MP CHURET – Chef mécanicien (cc)

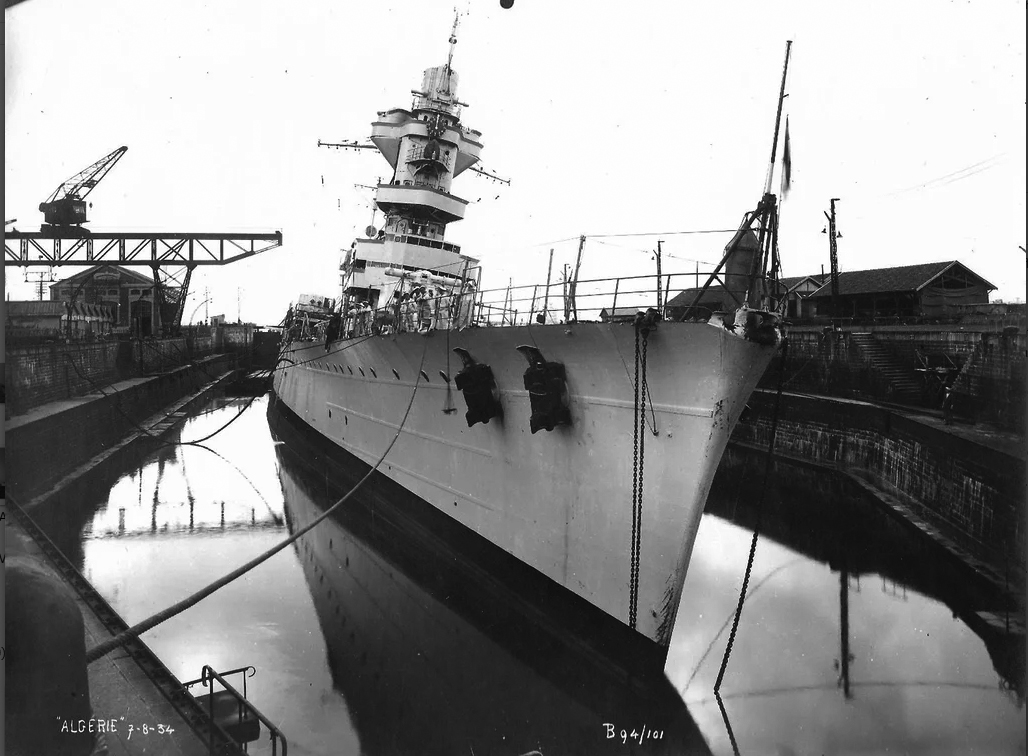

Algérie was laid down in 1931 at Brest NyD (Britanny, Atlantic coast) on 19 March 1931, she was launched on 21 May 1932 and commissioned on 15 September 1934, operational after trials that month. Her name was in relation to the centennary of the former colony, then a department (so officially part of mainland France), fastuously celebrated with a large naval review in front of Algiers, May 1930.

She started after her first sea legs, on 23 août 1933, and the end of preliminary trials on 22 december 1933. Her official tests started in January 1934 by endurance and consumption checks, to test her propulsion system. On 2 February, she made firing tests with her main battery and also reach her top speed ever registered at 33.2 knots with forced heat and a calm sea.

After these satisfactory tests, Algérie joined Brest for after testing work and refits. She layed in drydock Lannion until June 9, 1934 and was definitely commissioned on June 15, 1934 and the definitive armament was tested and provided on September 5, 1934. She left Brest in October for Toulon, with the long range crossing as the last test, making a stopover en route at Casablanca (October 11). Her final admission to active service was on October 19.

From November, she was attached to the 3rd light division also counting Duquesne, Tourville, Colbert Foch and Dupleix. She spent the next years in fleet exercizes, showing excellent characteristics. However no sister-ship was ever ordered as the global tonnage limit for cruisers defined at Washington was reached.

Despite her qualities, Algérie was never really put to the test, the only time she fired was on coastal installations.

Dakar and South Atlantic (1939)

Assigned to the first cruisers squadron (in the company of Foch, Tourville, Duquesne, Colbert and Dupleix), she was detached from Toulon to hunt for the Graf Spee in the South Atlantic. For this reason, she joined Dakar, French West Africa, where she was based, and operated with Strasbourg and the British aicraft carrier Hermes, but never spotted the German raider. She was back in the Atlantic.

North Atlantic (1940)

In March 1940, she escorted the battleship Bretagne carrying French gold reserves (3000 tons) to safety in Canada.

Mediterranean (1940-41)

After the Italian declaration of war, Algérie was sent to the Mediterranean. She reached Toulon, and was prepared for her first mission to shell facilities and installatons at the port of Genoa.

This episode has been seen in detail through Operation Vado 13-14 June 1940. She was part of the French 3rd Squadron (four heavy cruisers and 11 destroyers) which raided the Italian coast.

Algérie was part of the northern group, comprising Foch and the destroyers Aigle, Cassard, Chevalier Paul, Lion, Tartu and Vauban, heading for Vado and Savona, by night at 25 knots. She had there, a fair share of shelling starting before dawn, 16,000 yards (15,000 metres).

Algérie indeed set ablaze several storage tanks in Vado Ligure, not the cleverest decision however as due to the anemic wind, the thick black smoke soon obscured the other objectives and fire lost precision.

Later, MAS539 attacked Algérie at 2,000 yards (1,800 metres) but missed. She made it home unscaved like the rest of the fleet, also attacked by a TB Catalafimi, another MAS and submarines along the way. This was her only significant war action.

Algérie was afterwards on an escort mission when the capitulation came. She was anchored in Mers-El-Kébir but departed to Toulon and was miraculously not present when Operation Catapult began. So she escaped destruction, but later escorted the battle-damaged Provence to Toulon for extensive repairs. In 1941 she was given a better AA battery (16 x 37 mm and 36 x 13.2 mm) and a radar in 1942, or early French design.

Scuttling of Toulon (Nov.1942)

On November, 27, she sank at Toulon, like the rest of the fleet, scuttled to honor the pledge made by admiral Darlan that no French ship would ever be captured by the Germans (German photo, unknwon author)

Demolition charges were set on the ship and while the Germans arrived an tried to persuade the crew to not do so under the Armistice provisions; Algérie’s captain requested the Germans to wait until his superior could advise, leaving ample time for the crew to lit the fuses.

Admiral Lacroix ultimately arrived and by then the captain suddenly ordered the ship to be evacuated. The Germans prepared to board, but to avoid slaughter, the captain told their officers that the charges were about to blew up. The Algerie burned for 20 days, but overall was not that badly damaged.

Later that the Axis was now master of the harbor and the fleet, even in this sorry state, salvage operations took place. The intention was to transfer these ships to the Regia Marina after losses of 1941-42.

The Italians raised Algérie in pre-cut sections on 18 March 1943 after much effort, but the capitulation later stopped all progress. What left of the ship was bombed and sunk again on 7 March 1944 by allied aviation. Algérie would be raised and broken up for scrap in 1949 eventually.

Author’s rendition of algerie 1/700

| Dimensions | 186,2 m long, 20 m wide, 6,15 m draught (611 x 66 x 20.2 ft) |

| Displacement | 10 000 t. standard -13 641 t. Fully loaded |

| Crew | 748 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts direct geared SR turbines Rateau-Bretagne, 6 Indret boilers, 84 000 hp. |

| Speed | 31 knots (57 km/h) |

| Range | 8,700 nautical miles (16,110 km) at 15 knots (28 km/h) |

| Armament | 8 x 203 mm/55 (Mod. 1931), 12 x 100 mm DP (6×2), 8 x 37 mm AA (4×2), 16 x 13,2 mm AA HMGs (4 x 4), 2 x 3 550 mm TTs, 3 Loire 130 seaplanes. |

| Armor | Belt 120 mm, AT bulkheads 70 mm, deck 80, turrets 95 mm, CT 95 mm. |

Read More/Src

Gardiner Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-46.

Jean-Michel Roche, Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours.

http://forummarine.forumactif.com/t3803-france-croiseur-lourd-algerie

Chronology of the war at sea 1939-1945 (3rd ed.) London, Chatham Publishing

https://ww2db.com/image.php?image_id=19195

http://www.alabordache.fr/marine/espacemarine/desarme/croiseur/algerie-croiseur/photo.php

Paper model kit on kartonmodellbau.de

3D model on digitalnavy.com

Sketchup Model on 3dwharehouse

Turret Details on shapeways

The old Kombrig model kit

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

What made Algerie the best treaty cruiser? Wichita (CA-45) was much better armored, faster, had an extra main battery gun, had an arguably superior secondary battery, especially for AA, greater range and by 1942 when Algerie was scuttled, a much better electronics package. By mid-1942 she already had radar on her primary and secondary firecontrol directors.

Wichita may have been overweight by +-600 tons at normal displacement but at full load Wichita was +-600 tons lighter than Algerie.

Not hating on the Algerie at all, she was a handsome ship, just never understood why she stands out to everyone as the best treaty cruiser when Wichita was superior in pretty much every respect.

Hello Shaun, nice to have a debate on this question here !

First off, it’s ‘arguably’ the best heavy cruiser and indeed most authors agree she was so when built in 1930, designed before the London conference while USS Wichita arrived after the second conference of 1935 (launched 1937, comm. 1939). So she was considered so at the time she was launched. Indeed, compared to Wichita for which all this is true, but there was a gap of nearly 8 years in design, which is a lot in naval tech, especially at that time. It’s difficult to compare both ships during WW2 as Vichy France had no authorization or means to upgrade the ships in Toulon. I will do a post on the Wichita this year. It is likely to start as “The best London Conference Cruiser ?” 🙂

Best,

The shadow of the “young school” gabegie was still lurking over their folders: meaning ???

fixed !