Category: ww2 French Navy

Guepard class destroyer (1928)

French Navy – Contre-Torpilleurs de 2400 tonnes. 6 built 1927-1930, in service until 1942: Guepard, Valmy, Verdun, Bison, Lion, Vauban….

Chacal (Jaguar) class Destroyer (1923)

French Navy – Contre-Torpilleurs de 2100 tonnes. 6 built 1922-1925, in service until 1943: Jaguar, Lynx, Tigre, Chacal, Leopard, Panthere…

Courbet class Dreadnought Battleships (1911)

France (1911) – Courbet, Paris, France, Jean Bart (ex-Ocean) France’s first dreadnoughts The Four Courbet class were the first French…

Le Hardi class destroyer (1937)

French Navy – Standard 1500t destroyers, 14 built 1925-1931, in service until 1952: L’Adroit, Basque, Bordelais, Boulonnais, Brestois, Forbin, Frondeur,…

Mogador class Destroyer (1937)

French Navy – Contre-Torpilleurs de 3000 tonnes. 2 built 1934-1939, in service until 1942: Mogador, Volta. The Mogador-class destroyers were…

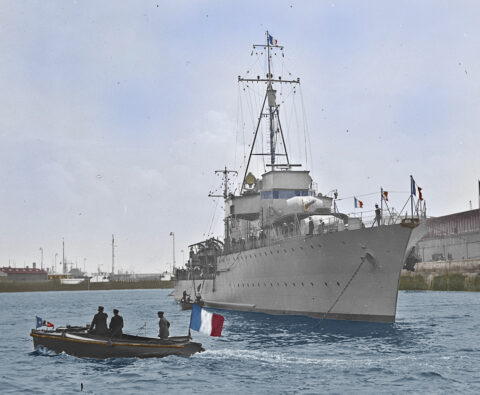

L’Adroit class Destroyer (1926)

French Navy – Standard 1500t destroyers, 14 built 1925-1931, in service until 1952: L’Adroit, Basque, Bordelais, Boulonnais, Brestois, Forbin, Frondeur,…

Vauquelin class destroyer

French Navy – Contre-Torpilleurs de 2500 tonnes. 6 built 1930-1934, in service until 1942: Vauquelin, Kersaint, Cassard, Tartu, Maillé Brézé,…

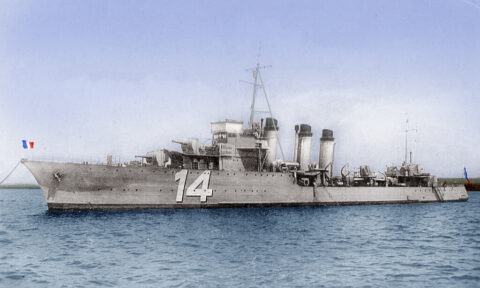

Bourrasque class Destroyer (1924)

French Navy – Standard 1500t destroyers, 14 built 1925-1931, in service until 1952: Bourrasque, Cyclone, Mistral, Orage, Ouragan, Simoun, Sirocco,…

Aigle class destroyer (1931)

French Navy – Contre-Torpilleurs de 2400 tonnes. 6 built 1927-1930, in service until 1942: . Milan in 1936-37 The Aigle-class…

Le Fantasque class destroyer

French Navy – Contre-Torpilleurs de 2500 tonnes. 6 built 1930-1934, in service until 1942: Le Fantasque, L’Audacieux, Le Malin, Le…

dbodesign

dbodesign