France (1911) – Courbet, Paris, France, Jean Bart (ex-Ocean)

France (1911) – Courbet, Paris, France, Jean Bart (ex-Ocean)WW1 French Battleships:

Duperre class | Terrible class | Amiral Baudin class | Hoche | Marceau class | Charles Martel class (1891) | Charlemagne class | Henri IV | Iena | Suffren | Republique class | Liberté class | Danton class | Courbet class | Bretagne class | Normandie class | Lyon classFrance’s first dreadnoughts

The Four Courbet class were the first French “monocaliber” or “dreadnought” battleships to enter service. They were started late, pending the scheduled completion of six Danton, decided at the time to not disrupt battleships production, added to the fact they were already “semi-dreadnoughts” with turbines. This delay was considered unfortunate in this new race for dreadnoughts that began in 1906. But the 1912 program, established by Admiral Boué de Lapeyrère had the ambitions to give France twelve other dreadnoughts before 1918. The war would decide otherwise. The Courbet class counted four ships, Courbet and Jean Bart of the first batch, both began in 1910 in Brest, launched and completed in 1913 and the other two, France and Paris, at St Nazaire and La Seyne in Toulon. These were not operational in August 1914, as hostilities just started: France aligned at that date only two dreadnoughts against 13 for Hochseeflotte and 22 to the Royal Navy. Still, they were quite active in the first world war, soon reinforced by the Bretagne class dreadnoughts.

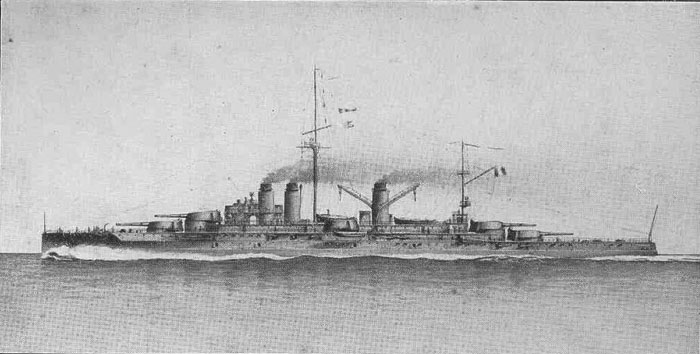

Postcard in 1914

Courbet and Paris, because of their obsolescence, were provisionally paid off as training ships in 1939, but back on active service in the 5th Fleet (Admiral Mord) in May 1940. Their mission was to try to intercept German forces that could approach from Cherbourg. They covered the evacuation of the city, as well as that of Le Havre, but were criticized for their weak AA defence. They were able to take refuge in Portsmouth in June 1940. During Operation Catapult in July, both were successfully captured by Royal Navy troops and their crews were interned. Later, Courbet was transferred to the Free French, rearmed and acted a floating HQ in Britain, then barracks and floating AA battery. Paris became herself a depot ship until the end of the war and. Courbet was disarmed in 1941, also a depot ship for the FFL at Portsmouth. In 1945, Paris was in Brest as a floating barrack, sold for BU in 1947, as Courbet.

Design

Courbet armour scheme diagram Brasseys 1912 (cc)

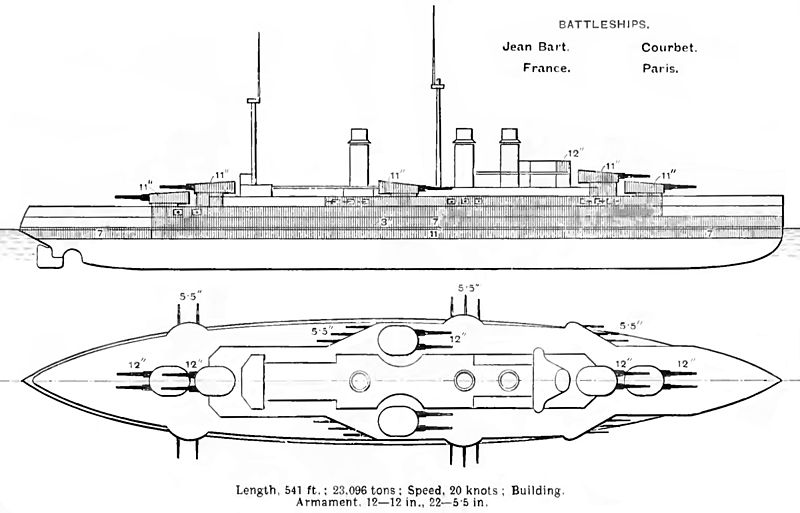

The Courbet class were very late, and through a combination of factors, became sub-par compared to than British, US and German dreadnoughts built at the time, already jumping on the “super-dreadnought” bandwagon with superior artillery than 12-inches. Their artillery configuration showed an early conventional layout closer to the Dreadnought 1906-1908 generation, a strong battery in chase or retreat respectively with 8 and 10 guns, for 12 total. But in 1914, the 305 mm caliber had been superseded by the 343 mm caliber with the 380 mm caliber being tested already and planned for the next class. The latter 15-inch shells were almost twice as heavy as 12-inch shells.

The Courbet were recognizable to their typically French three funnels separated by a single mainmast. Secondary armament remained below standard calibers of other navies (6 inches or 150 mm) while the anti-torpedo boat artillery was modest. These casemated 138 mm were however quick firing and filled the role of anti-torpedo defense. Relatively good steamers, thes Courbet class reached 22.6 knots. Shells provision was 100 rounds for each main gun, 275 rounds for each secondary. They were also fitted to lay down 30 mines.

Early Development

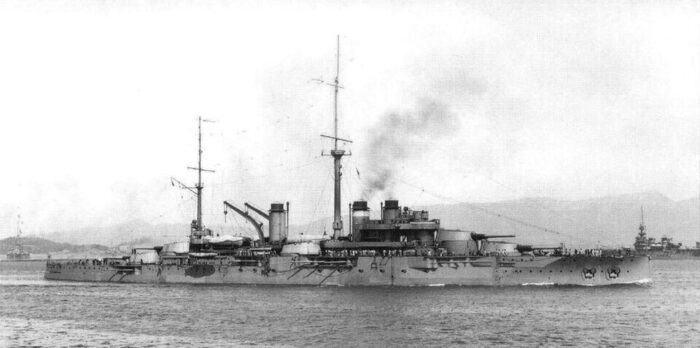

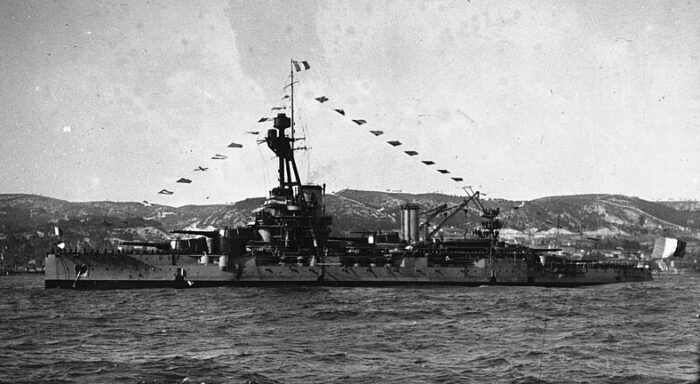

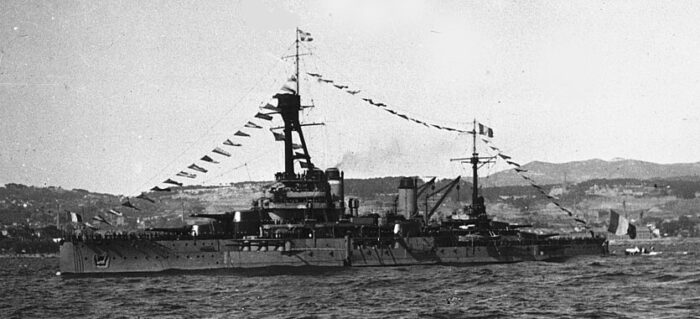

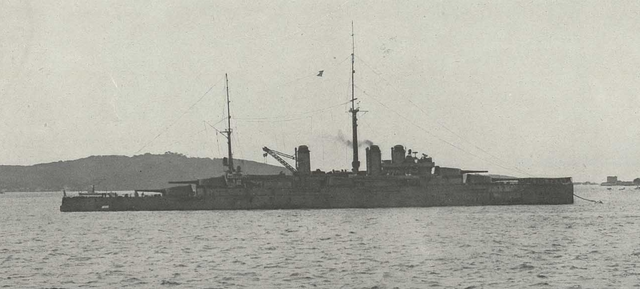

Battleship France off Toulon harbor (src: Gallica Digital Library – cc)

The Courbet class were very late, and through a combination of factors, became sub-par compared to than British, US and German dreadnoughts built at the time, already jumping on the “super-dreadnought” bandwagon with superior artillery than 12-inches. Their artillery configuration showed an early conventional layout closer to the Dreadnought 1906-1908 generation, a strong battery in chase or retreat respectively with 8 and 10 guns, for 12 total. But in 1914, the 305 mm caliber had been superseded by the 343 mm caliber with the 380 mm caliber being tested already and planned for the next class. The latter 15-inch shells were almost twice as heavy as 12-inch shells.

The Courbet were recognizable to their typically French three funnels separated by a single mainmast. Secondary armament remained below standard calibers of other navies (6 inches or 150 mm) while the anti-torpedo boat artillery was modest. These casemated 138 mm were however quick firing and filled the role of anti-torpedo defense. Relatively good steamers, these Courbet class reached 22.6 knots. Shells provision was 100 rounds for each main gun, 275 rounds for each secondary. They were also fitted to lay down 30 mines.

The roots of the program lays in the aftermath of the Jeune Ecole theories from Amiral Aube, born from the post-1870 budget restrictions imposed on the Navy. In the 1890s, the realization that these theories were no long relevant, just started to seep in. Little by little, the influence of the Jeune Ecole, prevalent in French naval circles formatting several generations of officers over two decades, even still canon at the academy, was now weakening and fraying. The Fashoda Crisis of 1898 caught the Marine Nationale in a dangerous state of weakness in the face of a Royal Navy at the height of its power. Battleship construction was revived by the 1900 program passed by the Waldeck-Rousseau administration, allowing for the construction of the République class, Liberté class, and eventually the Danton class.

They were groundbreaking. Until then indeed, the French battleships were condemned not to exceeded 12,000 tons, and even then, the Jeune Ecole considered them as behemoths to be of little use, and saw them built sparingly on a one-at-a-time testing basis. As its ideas waned off, engineers concerned by this 1900 naval program were able to think “outside the dry-dock” quite literally and freely design battleships of 15,000 tons and more, now the new international standard for battleships. More so, they would be standardized, and the design inflexible among all yards. The problem was always the same, the inadequacy of naval facilities. The subject has been seen more in detail about the Danton class already, so let’s jump to the next step.

The Republique-Patrie had been solid, well-made battleships already featuring a rather modern all-turret armament rather than in casemates, good speed, better armour arrangement, and …less tumble home. They were a good basis for future development, however the last of the second class, Vérité, was launched… in May 1907. So a full year after HMS Dreadnought. She had been laid down in 1903 however, showing the still prevalent issues with French naval construction very slow and punctuated by frequent minister changes and unavoidable last minute design changes…

At this stage it was obvious the writing was on the wall for traditional battleships, and France should have jumped into the train… But the years 1905, where such decisions should have been made, saw a completely different path. It started already in August. The departure of Camille Pelletan from the Ministry of the Navy, fortunately, ended definitively all influence of the Jeune Ecole on naval program and a return to healthier prospects, particularly with regard to battleships. The new Minister of the Navy, Gabriel Thomson, submitted a budget proposal for the construction of three 18,000-ton battleships in line with the 1900 program. The jump from 15,000 to 18,000 tonnes however was all but theoretical given the same shipyard limitations we saw earlier. But such tonnage gave a little more leeway concerning the crucial question of armament, with three scenarios emerging:

The first was a ship with six 305mm guns and twelve 194mm guns, a rather advanced semi-dreadnought, but still not a true dreadnought.

The second proposal was for four 305mm guns, twelve 240mm guns, so a true semi-dreadnought.

The third proposed a uniform armament of ten 305 mm guns, in effect, the first French dreadnought.

However, discussions soon ran into the reality of the existing drydocks for their construction and calculations related to the placement of these five barbettes. In length, any hull could only have sported three of these, then in beam, and that was the decisive factor, there was just no sufficient width in existing drydocks to create a design beamy enough for two side by side barbettes, taking in account the intermediate width of the machinery space. It was just not doable. If given investments in time to enlarge these drydocks, if feasible (for which both the yards themselves and the government dragged their feet) and given the plan for four battleships to be laid down in different ports, it just could not be done.

So the minister chose the second solution for the Danton class. And this has been criticized, rightly so, constantly ever since.

However, given the 1905 context, this decision seems more sound that it seems. First off, if Cuniberti’s famous article of 1903 was seen by all admiralties, from theory to reality no country had yet made that decision. Instead, all Navies newest project were traditional battleships with a serious infusion of speed and heavy, very heavy secondary batteries. Even British officials at the time were doubtful about “Fisher’s folly” and considered the Nelson class to be instead the future, notably because of their lower price and with a manageable speed for well known battle fleet operations. More so, telemetry and fire control were still in their infancy. The maximum ranges were still close to 10,000 meters. In this context, the higher rate of fire of 240mm guns versus 305 mm, for a relatively similar broadside weight still, compensated for only twp pairs of 305mm guns envisioned. In fact, given their respective mounts, they ended about at a similar range. The smaller barbettes for these twin turrets were more manageable and freed useful space which could be used for extra speed and protection.

For the remainder of 1905 and to mid-1906, the debate over the single-caliber artillery combat ship raged on. Fisher’s positions were still far from unanimous even close to launching his pet project, and in part due to the fiery character of the First Sea Lord. Grand Admiral Mahan for example, the most respected Anglo-Saxon naval theorist at the time, vehemently opposed this concept. And thus, the construction of the six Dantons proceeded. It would be delayed, again, so that they ended all commissioned in the summer of 1911… When the Orion class were launched, the first “super-dreadnoughts”. At that stage, and since the drydocks were “freed” in 1909-1910, the French Navy had no choice but to embrace the Dreadnought formula, now fully proven in these last years. No only it was a proven concept, effectiveness, but was emulated by virtually all navies, even Austria-Hungary, Russia, Brazil and Argentina.

The Dantons were 18,400-ton, 146.60 meters long ships capable of 19.25 knots, and if their twelve 240mm guns were a serious proposition they lacked an intermediary quick firing caliber. Indeed, between the heavy guns and sixteen 75mm guns, ten 47mm guns, there was nothing, a crucial gap in their defensive envelope against torpedo boats. That limitation was taken in account.

The 1912 Naval Plan

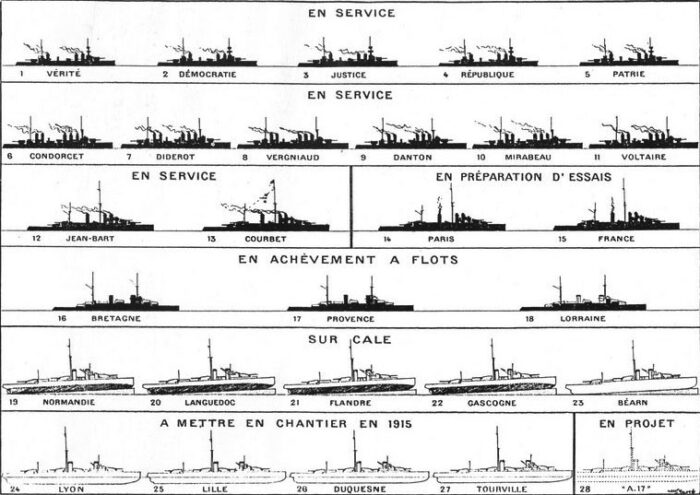

‘Illustration of April 1914 showing the frontline French Battle fleet: The Republique-Patrie, Danton, recently commissioned Jean Bart and Courbet, Paris and France in sea trials, the three Bretagne being completed, and the Normandie class laid down, the Lyon class planned to be laid down in 1915. Of course, the war will completely shatter these plans.

The Fashoda Crisis of 1898 caught the French Navy in a dangerous state of weakness against the RN, at that stage a sleeping beauty soon awakened by the John Arbunot Fisher, having no trouble envisioning a fighter against a French Navy steeped in the questionable ideas of the Jeune Ecole.

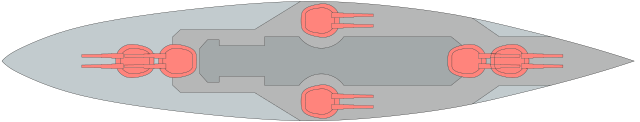

After the departure of Camille Pelletan, aka “the navy wrecker,” French political and naval authorities wanted the Jeune Ecole definitively shelved with sound, homogenous battleship construction programs resumed to restore France at its “natural ranking” in naval powers, notably with Berlin now engaged in a feverish arms race. The 1910 already looked good on paper, even facing Italy about to join forces with Austria-Hungary in the Mediterranean. Once the principle of a dreadnought was accepted in 1912, the Courbet class were planned, designed by engineer Leon Lyasse as an adaptation of the Danton design, better armed and armoured initially. The French rejected the standard hexagonal configuration for the main armament of the Courbet class in the frame of the 1912 naval program.

One key architect of the French dreadnought fleet was, without a doubt, Boué de Lapeyrère, the “French Fisher”. On July 24, 1909, Admiral Boué de Lapeyrère was appointed Minister of the Navy and prepared all the plans for a formidable rise in power of the French Navy, notably due to the ongoing naval arms race between Great Britain and Germany. Her left the ministry on November 3, 1910, and became Commander-in-Chief of the French Navy between August 1911 and 1916, witnessing the vote on March 30, 1912, of the program law he worked out, which planned the imposing Navy was to achieve by the early 1920s. If the second projected class had been laid down in 1915-16 as planned, they would have been completed by 1918-1920, leaving France with a dreadnought fleet of 17 dreadnoughts, 6 semi-dreadnoughts and 5 pre-dreadnoughts, plus probably four or more battlecruisers (planned by engineer Gilles in 1914) and scout cruisers such as the planned Duguay Trouin:

One key architect of the French dreadnought fleet was, without a doubt, Boué de Lapeyrère, the “French Fisher”. On July 24, 1909, Admiral Boué de Lapeyrère was appointed Minister of the Navy and prepared all the plans for a formidable rise in power of the French Navy, notably due to the ongoing naval arms race between Great Britain and Germany. Her left the ministry on November 3, 1910, and became Commander-in-Chief of the French Navy between August 1911 and 1916, witnessing the vote on March 30, 1912, of the program law he worked out, which planned the imposing Navy was to achieve by the early 1920s. If the second projected class had been laid down in 1915-16 as planned, they would have been completed by 1918-1920, leaving France with a dreadnought fleet of 17 dreadnoughts, 6 semi-dreadnoughts and 5 pre-dreadnoughts, plus probably four or more battlecruisers (planned by engineer Gilles in 1914) and scout cruisers such as the planned Duguay Trouin:

-28 battleships

-10 scout ships

-52 fleet torpedo boats (destroyers)

-10 colonial station ships

-94 submersibles.

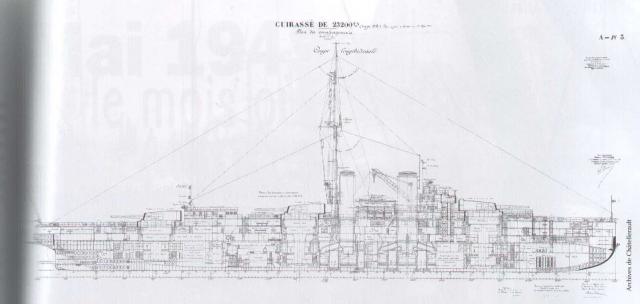

Plans for the Normandie class, laid down in 1913-14

Of the 28 battleships planned (increased to 36 if parliament deputy Mr. de Lanessan, had seen his amendment accepted), 11 were already in service, all pre-dreadnought, leaving 17 dreadnoughts to be built: Two laid down in 1910 and 1911, three in 1912, two in 1913 and 1914, four in 1915, and two in 1917. But international tensions (1912 Italo-Turkish war, 1913 Balkan war) and fears of a major war breaking out and priorities being reset in favor of the Army, pushed political authorities to accelerate construction, so by 1913, the Navy was authorized to lay down four battleships instead of the two planned. However, again, drydocks were not ready yet, and only one was to be laid down in 1914, January 1st. Overall four battleships were laid down in 1915, two in 1917, and it was planned two in 1919, two in 1920, four in 1921 and two in 1922, t be commissioned in 1925, now with 24 “super dreadnought”: 3 Bretagne, 5 Normandie, 4 Lyon, plus five ships of an unidentified type, likely Gille’s battlecruisers, plus the four Courbet.

That was the revised 1913 naval plan. To accelerate things further, the Navy decided to stick to the new 340 mm/45 M1912 guns planned for the Bretagne class and the mass-produced to equip all the 4-turreted Normandie/Lyon class dreadnoughts to follow. The latter would have needed much larger drydocks by the way, but if completed, would have sported sixteen 13.4 inches armed capital ships, an unprecedented battery able to outclass even 15-in armed battleships by sheer fire volume at closer range. Again, fire control was still not considered reliable enough.

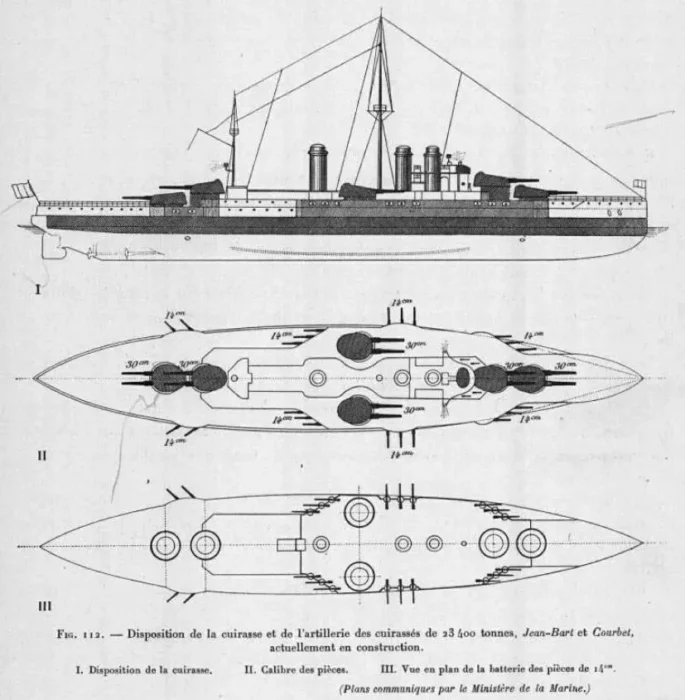

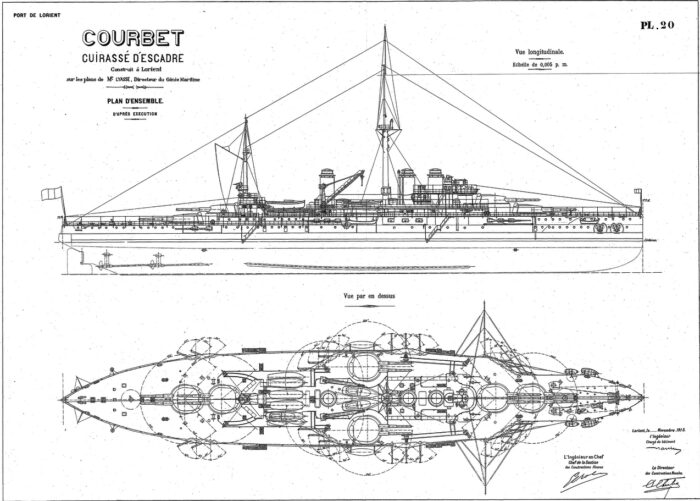

The Courbet-class battleships were designed under the direction of Chief Engineer H. Lyasse, replacing in 1910 L’Homme as head of the Technical Section of Naval Construction (STCN). These clearly were a step-up in terms of tonnage, from 18,000 tons (Dantons) to 23,500 tons, so a 30 percent increase. The hull layout was classic, and still draw some similarities with the Dantons, but with more beam to accommodate the larger barbettes, and an armament which resembled the Brazilian Minas Gerais. The main gun caliber remained the same, as the new 340 mm was still being developed at the time, so sticking with the same 305mm and gun mounts present on the Danton class. Lyasse developed a design with twelve guns distributed in six twin turrets, two more than HMS Dreadnoughts and its successors of the early dreadnoughts.

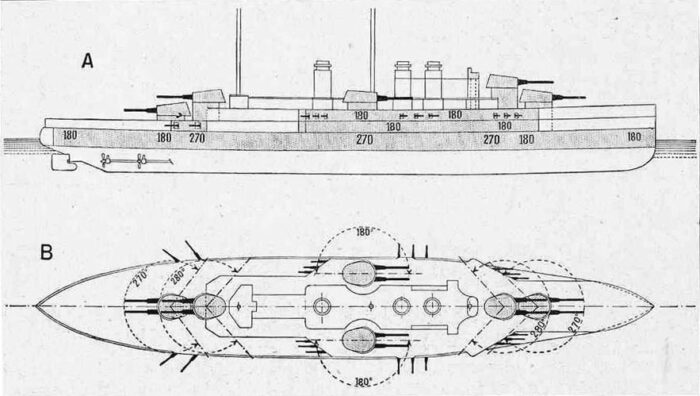

Lyasse made the choice of having two superfiring turrets fore and aft, plus two side amidship, which maximized chase and retreat fire and still procured a ten gun broadside. The secondary armament was still the same as for the Dantons and weaker than foreign design, but faster firing: Twenty-two 138mm guns, conventionally mounted in casemates instead of turrets to compensate for the weight of the main gun turrets. This was complemented by four 47mm guns and four 450mm torpedo tubes.

Armor was supposed to protect against above and below waterline 12-iches shells, but not 13.5 inches shells. Overall, it was comparably weaker than US-UK battleships, which belt extended less below the waterline.

The names renewed with a naval tradition, rather than Republican figures and ideals: Courbet, Jean Bart, but also Paris, and France as if the parliament still was not sure of a naming coherence. Construction was divided between four different shipyards that were expanded at great cost for the task. Two arsenals, Brest for “Jean Bart”, Lorient for “Courbet”, and two private shipyards such as Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée [FCM] at La Seyne-sur-Mer for “Paris” and Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire [ACL] in Saint-Nazaire for “France”. Three yards were on the French west coast, one on the riviera.

Hull and general design

Main elevation longitudinal view, 1/200 plans by M. Lyasse, dated November 1913.

Concerned about underwater hits, the class’s French designers decided to extend the waterline armour belt well below the waterline, as compared to their contemporaries. The main armour was also thinner than that of its British or German counterparts, but covered more area. Their secondary armament was of a smaller size than the 15 cm (5.9 in) guns used by the Germans or the British 6-inch (152 mm) guns, but the French placed a premium on rate of fire rather than size, in order to destroy torpedo boats before they got within torpedo range. The plans were drafted at Lorient Arsenal (By Lyasse) and then copied and passed on to the three other naval yards.

Displacement was 23,475 t (23,104 long tons) at normal load, 25,579 t (25,175 long tons) at full load, for an overall length of 166 m (544 ft 7 in) a beam of 27 m (88 ft 7 in) and draught of 9.04 m (29 ft 8 in). The hull still shared many similarities with the Danton class, but was beamier, with a lower deck about 50% long aft, and forecastle jagged by the presence of massive cutouts to maximize secondary casemate fire, in a rather extreme arrangement of three casemates firing forward per side (six total) and the same aft. They shared their pointy stern with the Dantons, as well as their straight bow without ram, and bow chin nicely curved line. The bow was reinforced, and the ship would have been able to ram and roll over a smaller ship or submarine. The hull had a deep draft, taller than the above water hull, with a single large L shaped rudder and four shafts instead of three on previous pre-dreadnoughts. They had three main anchors in recesses, two starboard, one to port.

The superstructures were rather minimalistic and organized around the turrets, with important cutouts to guarantee the best fire arcs, notably for the amidship turrets that were supposed to have a 180° fire arc. It was reduced in practice to avoid deck and structure damage due to the blast effects. The superstructures comprised a conning tower right behind “B” superfiring main turret, with an open bridge around and above with wings, light projectors, the main funnels group with platforms, the third funnel aft sandwiched at the rear of the two wing turrets, cranes and main service boats, then the aft bridge, and aft mast. The mainmast was located behind the second funnel and rather massive, with an observation post. Fire control however was rather primitive still (see later). The Courbet class carried 15 boats, including 8 on the upper deck amidship and six under davits. There were three powered admiral cutters with cabin. Two were located forward of the aft funnel, one at the rear.

Powerplant

The Courbet-class were powered by four Parsons direct-drive steam turbines (which poses the question of French engineering independence at that stage). They were rated at 28,000 shp (21,000 kW) and were fed by twenty-four Belleville (Courbet, Jean Bart) water-tube or Niclausse boilers (Paris, France) depending on the yards, eight small and sixteen large. The large boilers were located in the two forward boiler rooms; hence the two funnels, the small boilers in the rear boiler room truncated in a single funnel. Each boiler room housed eight boilers, all coal-burning but with auxiliary oil sprayers.

Top speed was 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph), but all four were faster on trials, reaching up to 22 knots. This was “average” given the RN and Germany now targeted 23 knots. The courbet class carried up to 2,700 long tons (2,743 t) of coal, 906 long tons (921 t) of oil and were able to steam for 4,200 nautical miles (7,800 km; 4,800 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Thus was tolerable for the Mediterranean but in comparison the Orion class (also coal powered) were capable of 6,730 nmi (12,460 km; 7,740 mi) at 10 knots, the Iron Duke class 7,780 nmi, and the next Queen Elisabeth class, oil-powered, were now capable of almost 7900 nmi.

Protection

The Courbet-class in detail:

-Waterline armoured belt: 4.75 m (15.6 ft) deep, 270 mm (11 in) thick, tapered down beyond barbettes to 180 mm (7.1 in) bow and stern. 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) below the waterline.

-Upper belt: 180 mm thick over the casemate battery deck and forecastle deck, 4.5 m (15 ft) higher between barbettes again. It was backed by 80 mm (3.1 in) of wood.

-Four armoured decks: Between 30 and 48 mm (1.2 and 1.9 in), 2 or 3 plating layers.

-Lowest armoured deck curved down to the lower edge of the waterline belt: 70 mm (2.8 in).

-Conning tower: 300 mm (11.8 in) thick.

-Main gun turrets: 290 mm (11.4 in) faces, 250 mm (9.8 in) sides, 100 mm (3.9 in) roof. Barbettes 280 mm (11 in).

-No anti-torpedo bulkhead, but longitudinal bulkhead abreast the machinery spaces (coal bunker/void).

Armament

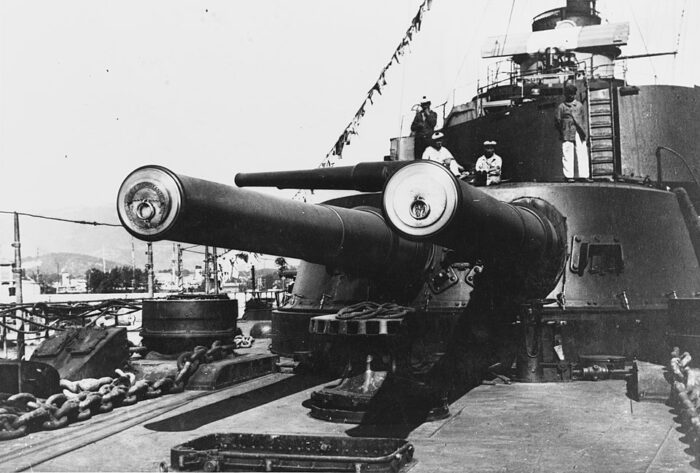

Main Guns: 12x 305 mm/45

Twelve 305 mm Mle 1910 45-calibre, mounted in six twin gun turrets, A-B, X-Y superfiring fore and aft, plus wing turrets.

The 30 cm/45 Modele 1906-1910 had an actual Size of 305 mm (12.008″). The Model 1906 was adopted on the Danton class pre-dreadnoughts and the Model 1906-1910 on the Courbet class battleships. They were also used as railway ordnance during World War I (and reused by the Germans in the Atlantikwall, firing German shells), and so a widespread model with a large production. Construction was a built-up design, light but with a stronger breech piece than the previous 305 mm/40 guns. Breech mechanism were of the interrupted-thread breech block with Farçot breech mechanism operated electrically or manually as backup, instead of a Manz-type interrupted screw breech block.

The APC shells were called “obus alourdi” (heavyweight shell) with a base fuze using a dual delay mechanism to engage both thin-skinned and heavily armored targets. They replaced the former, separate APC (obus de rupture) and SAPC (obus de semi-rupture). These dual delay base fuzes needed further work to be reliable though.

The propellant loads for the HE Model 1916 were reduced compared to the APC Model 1906 as the HE, with thinner walls. They could not handle the added stress of a full charge but had a much higher muzzle velocity, longer range than the APC projectiles: At the same 12 degrees, 18,260 yards (16,700 m) instead of 14,760 yards (13,500 m). Note that the Danton’s 1906 guns had a better range at 15,860 yards (14,500 m).

Specs

Gun weight and size: 120,590 lbs. (54,700 kg), 558.07 in (14.175 m), bore 536.42 in (13.625 m)

Chamber Volume: 12,921 in3 (211.787 dm3)

Shell: 432 kgs (952 lb) AP.

Muzzle velocity: 783 m/s (2,570 ft/s)

Rate of fire: 2 rounds per minute at best.

Provision: 100 shells each.

Approximate Barrel Life: 300 rounds

Maximum elevation 12°. This was an infamous down record making for an exceptionally poor range for their calibre at 13,500 m (14,800 yd). The belief at the time was that long range gunnery was useless and naval combat was much closer, to put the secondary armament to bear, at least that was the idea coming from the Russo-Japanese war in France.

There was a 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) rangefinder inside B turret. In the interwar the mounts were modified to a 23° elevation, range now c18,000m, see later.

To compare, the WWI stock British 15-in guns had a 33,550 yards (30,680 m) yards at 30+ elevation. More than twice as much.

The much lighter secondary guns were just 1,000 m shorter range in comparison.

In the interwar, the Italian dreadnoughts (Cesare/Cavour) were rebuilt with rebored 320 mm Model 1934 naval guns, capable of 30 kilometres (19 mi).

In case of any naval combat in 1940, the Courbets were doomed. In 1914, they were already out-ranged by many pre-dreadnoughts, such as the British Nelson class.

More

Forward turrets photographed by Robert W. Neeser, probably at Toulon, France, circa 1919. Note the triplex rangefinder on the conning tower

Secondary: 22x 138 mm Mle 1910

The secondary armament comprised twenty-two 138 mm Mle 1910 guns all in casemates. The four stern ones, and this was true also for the following Bretagne classes were mounted only 12 feet (3.6 m) above the waterline and useless in most sea conditions. The 138.6 mm/55 (5.46″) Model 1910 were mass produced to be used on the Courbet, Bretagne, Normandie, Lyon and Arras Classes. They compensated on paper their lower calibre for a quicker velocity.

Specs

Gun weight and dimensions: 11,680 lbs. (5,300 kg), 309.2 in (7.854 m), bore 300.2 in (7.626 m)

SAP Shell: 39.5 kgs (87 lb) 27.8 in (70.7 cm) with 5.9 lbs. (2.66 kg) melinite. Muzzle velocity 840 m/s (2,800 ft/s).

HE Shell: 69.4 lbs. (31.5 kg) 23.11 in (58.72 cm). MV 2,756 fps (840 mps)

Elevation: 15°, range 10,970 yards (12,000 m).

Rate of fire: 5–6 rounds per minute

Storage per gun: 275 rounds.

The same size cartridge case was used in all 138.6 mm guns from the Model 1910 onwards.

Later in refits the mounts were mofified up to 25° elevation, range of 17,600 yards (16,100 m) SAP and 16,500 yards (15,100 m) HE.

More

Light Guns

The ships carried four 47 mm (1.9 in) Modèle 1902 Hotchkiss guns, two on each beam.

Torpedo Tubes

Four 450 mm (18 in) submerged Modèle 1909 torpedo tubes were installed, with twelve torpedoes total.

Fire Control

Fire control arrangements were very primitive and the Courbets were only provided with one 2.74 m (9 ft 0 in) rangefinder on each side of the conning tower. Each turret had 1.37 m (4 ft 6 in) rangefinder under an armoured hood at the rear of the turret. This was changed several times in the interwar.

France in 1914. Author’s illustration. Notice the hoists heavy torpedo nets, abandoned some time later.

Courbet class specifications (1914) |

|

| Dimensions | 165,9 x 27,9 x 9 m |

| Displacement | 22 200t; 26 000 PC; FL |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft Parsons Turbines, 24 Belleville/Niclausse boilers, 28,000 hp |

| Speed | 20 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 4,200 nmi (7,780 km; 4,830 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 12 x 305 mm, 22 x 138 mm, 4 x 47 mm et 4 TT sides 450 mm |

| Armor | Belt 270, turrets 320, blockhaus 300, barbettes 270 mm, Decks 20-70 mm |

| Crew | 1108 |

Modernizations

Paris in 1936, author’s illustration

The three Courbet class were the oldest dreadnoughts in the French navy, and Courbet, Paris, Ocean, and France after the Great War were related to the 1st generation of dreadnought, and while in interwar Britain, constrained by treaty to get rid of all its 1st gen. Dreadnoughts and all early super-dreadnoughts (Orions, KGV, Iron Duke), France, which program has been gutted by the war, was left with these now obsolete ships. In 1922, “France” sank off Quiberon bay on an unlisted reef, leaving only three that badly needed.

A 1920 assessment listed their weaknesses as:

-No director control for the guns

-The elevation of the main guns was insufficient

-Protection against torpedoes was weak

-The horizontal protection against plunging fire was weak

-The anti-aircraft defence was negligible

-They were coal-fired

-The organisation of the crew, lighting, order transmission were old-fashioned.

The survivors were refitted several times in the interwar to remedy some of the most glaring issues, although no comprehensive modernisation was ever planned. In fact successive government failed to vote the necessary laws. They ended extensively modernized at last in 1926-29. However, initial plans were shattered by the 1929 financial crisis, and no major changes took place up to September 1939. The ships remained “in their own juice”.

Paris in 1927

In short:

Modifications included three funnels down to two with new oil-fired boilers, two new masts with a forward tripod for a new firing control arrangement and new, larger rangefinders. The order transmission systems were modernized and the elevation of their main guns mounts was also improved at 23°, extending their initially laughable range. They also received additional AAA, albeit still completely inadequate in 1940, of seven 76 mm guns and two 45 mm guns. There was the addition of more rangefinders, but the replacement of coal-fired boilers by oil-fired units was only partial. However, the replacement of the direct-drive turbines by geared turbines was real progress. The bow armour (no ramming intended) was retired to reduce forward weight and improved sea keeping as their flare was virtually nil.

Courbet, which machinery was the oldest, received new engines from the stock provided for cancelled battleships of the Normandie class, whose design was however going back to 1913, but at least used oil-fired boilers. ASW protection was somewhat improved by adding an extra internal sub-division. Northing could be done to alleviate their outdated artillery disposition, and that was still a very low calibre in 1940 with a modern standard between 356 and 406 mm. The AA firing system was also completely obsolete by 1939.

First refit 1927-24:

-Four new oil-fired du Temple boilers replacing old ones

-Trunking of the two forward funnels.

-Maximum main gun elevation from 12° to 23°, range to 26,000 metres (28,000 yd).

-Four 75 mm Modèle 1918 AA guns installed in place of the m1914.

-Bow armour removed (making them lighter, more seaworthy).

-New tripod foremast with fire-control position on top.

-Barr & Stroud 4.57 m (15 ft) rangefinderon its roof position

-Experimental Barr & Stroud FX2 7.6 m (24 ft 11 in) coincidence rangefinder, roof aft superfiring turret

Jean Bart 1927

Second refit 1927-31:

-Saint-Chamond-Granat system director-control tower (DCT), top of the tripod mast

-Rangefinders replaced (exception to 2-me (6 ft 7 in) rangefinders in each turret).

-DCT was fitted with a 4.57 m coincidence rangefinder plus 3 m (9 ft 10 in) stereo rangefinder (to measure distance between target and splashes).

-4.57 m rangefinder in duplex mounting atop the CT

-4.57 m rangefinder at the base of the mainmast.

-Barr & Stroud 7.6 m replaced by 8.2-metre (26 ft 11 in) rangefinder, roof B turret.

-Directors 2-metre rangefinders to control secondary guns.

-Mle 1918 AA guns replaced for M1922

-2x HA (high-angle) 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) rangefinders on top of the duplex CT and aft superstructure.

Modifications 1938-39:

-Torpedo tubes removed

-4-6x Hotchkiss 13.2 mm (0.5 in) AA HMGs added.

Overall, this level of modernization was still ludicrously inadequate, especially compared to Italian modernized battleships in the second half of the 1930s, far more radical. The Guilio Cesare and Cavour for example had brand-new turrets with re-bored guns, modern FCS, brand new secondary artillery and AA, elongated hulls with better sea keeping, completely new and modern power plants for better performances, completely modernized armour scheme, and ended as valuable frontline units. The French Courbets however, were virtually useless in a modern war and only usable as training ships or for minor roles. At least the Bretagne benefited from a more comprehensive modernization.

Active service

Courbet in the interwar – sepia illustration By Francis T. Hunter, Coll. Beatty, Jellicoe, Sims & Rodman. (cc)

The four Courbet were sent to the Mediterranean in 1914. Paris already conducted her first operational sortie. Courbet became flagship of Admiral Lapeyrère, and two additional spotlight were added on platforms, on “B” turret. These five ships served intensely, Jean Bart was torpedoed by U-12 in December 1914 in the Adriatic, but without much damage. France and Jean Bart were also sent to Sevastopol in 1919. At that time, the four existing ships were now obsolete, pending modernization. It was observed that their forward deck ploughed in heavy weather, but it was not possible to have them lengthened because of the lack of suitable dock. France hit a reef and sank in 1922 near Quiberon, and the other three, partially modernized, acted as training ships in 1939.

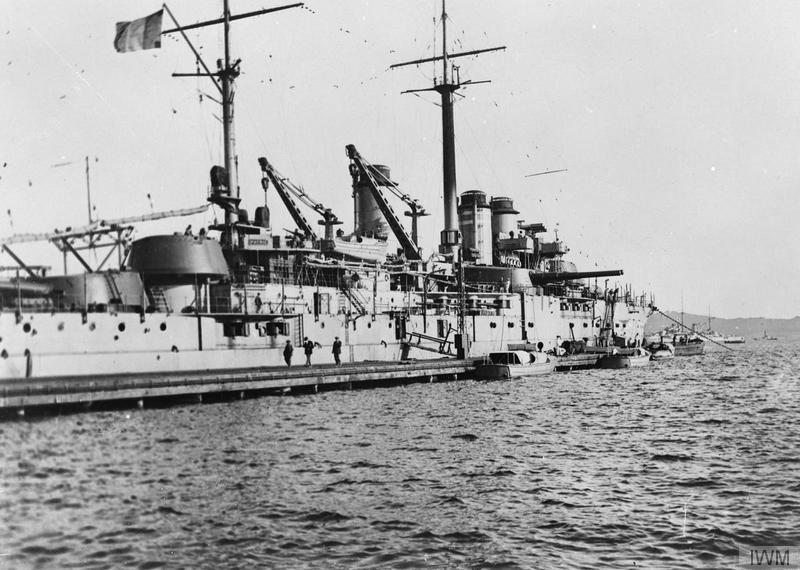

Courbet’s stern view, Toulon, 24 September 1916. – IWM coll.

Courbet (1911)

Courbet (1911)

Courbet was ordered on 11 August 1910 (named after Admiral Amédée Courbet), laid down on 1 September 1910 at Arsenal de Lorient, launched on 23 September 1911. After sea trials, she ferried the President of France (Raymond Poincaré) for an official visit to Britain on 24–26 June 1913. She was completed on 8 October (cost F57,700,000), commissioned on 19 November. With Jean Bart she was assigned to the 1st Battle Division, 1st Battle Squadron, 1st Naval Army in Toulon, as flagship for Vice-Admiral Vice-Amiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère from 5 January 1914.

On 2 August she became fleet flagship and was mobilized to find the SMS Goeben watching over troop convoys from North Africa. She sailed with the 2nd Battle Squadron to Bougie (Algeria) and met Jean Bart and France off Valencia in Spain to Toulon, one having elevation issues and the other no ammunition aboard. On 7 August, Courbet and Condorcet escorted a convoy from Algiers via Toulon.

From 12 August, Boué de Lapeyrère ordered a global sortie to the Adriatic, meeting a small British force on the 15th, and heading for Otranto. The armoured cruisers patrolled off the Albanian coast and Austrian ships were spotted on 16 August, with SMS Zenta sunk off Antivari. Boué de Lapeyrère transferred his flag to Jean Bart and on 1 September, the units was bombarding Austro-Hungarian coastal fortifications in the Bay of Cattaro. After several sorties, she spent time between the Greek and Italian coasts. The torpedoing of Jean Bart on 21 December by U-12 showed ended operations, all were back at anchorage in Navarino Bay.

Courbet in 1916 – Src Europeana 1914 – 1918, originally published in La Guerra in 1916.

Courbet was laid down at Arsenal de Lorient in Lorient on 1st September 1910, launched on 23 September 1911, commissioned on 19 November 1913.

On 11 January 1915, a sortie from Pola was signalled, Courbet, Paris, France led the Army north to the Albanian coast, but this was a false alarm, later patrolling the Ionian Sea. With the Italian declaration of war on 23 May, assuming responsibility for the Adriatic, the French Navy was split between Malta and Bizerte, French Tunisia, to cover the Otranto Barrage. Courbet had twp 47 mm guns on high-angle mountings and two 75 mm (3 in) Mle 1891 G installed. On 27 April 1916 she was at Argostoli, Cephalonia and partially deactivated, with crews transferred to ASW sloops. In 1917, she was moved to Corfu, but rarely operated due to shortages of coal. In 1918, she left Corfu only for maintenance in Toulon and by 1st July, the Naval Army with Courbet, Paris and Jean Bart were reassigned to the 2nd Battle Division. Her mainmast was shortened with a motorised winch installed for a kite balloon, tested and retired.

By late November she was back at Toulon for a refit, placed in reserve and becoming Vice-Admiral Charlier’s flagship from 6 June 1919 to 20 October 1920. On 10 February 1920 the Naval Army was disbanded, replaced by the Eastern and Western Mediterranean Squadrons, and the Mediterranean Squadron on 20 July 1921.

In 1922, she was re-rated as a gunnery training ship at Toulon with a serious boiler fire on 6 June 1923 and repairs, then modernization from July 1923 to April 1924 at La Seyne. New oil-fired du Temple boilers were installed, truncating changed (2 funnels). The gun’s maximum elevation was increased for a 26,000 metres (28,000 yd) range, four 75 mm M1918 AA guns installed, bow armour removed, tripod foremast fitted, Barr & Stroud 4.57-m (15 ft) rangefinder and Barr & Stroud FX2 7.6-m (24 ft 11 in) coincidence rangefinder. She had another boiler fire on 1 August 1924 (13 wounded, 3 killed later). With Provence, she visited Naples on 15–19 June 1925, met Jean Bart and Paris at Mers-el-Kebir to ventured in the Bay of Biscay and the assembled ships with the Atlantic squadron had a naval reviewed by President Gaston Doumergue at Cherbourg. She was back at Toulon on 12 August. In January 1927 she started a new modernization until 12 January 1931.

On 25 March 1931, one turbine broke down in trials, she was repaired and resumed sea trials on 9–12 June, then assigned to the Training Division, gunnery school. She had exercises in February to May 1932 but had her condensers re-tubed, inner propellers replaced. In 1933-1934 with Paris she returned to the Training Division. Courbet had her machinery overhauled in 1937–1938, torpedo tubes removed and AA reinforced. The Training Squadron was disbanded on 10 June 1939 she was reassigned to the 3rd Battle Division, 5th Squadron, cruising on 14 June to Mers-el-Kebir and Casablanca, then Brest on 11 July reassigned to the 2nd Maritime Region as gunnery training ships.

With the invasion of France on 10 May 1940 she was mobilised on 21 May with augmented crews, placed under command of Vice-Admiral Jean-Marie Abrial to defend French ports in the Channel and Courbet provided gunfire support off Cherbourg on 19 June, shelling the 7th Panzer Division, covered the evacuation in Operation Aerial. She sailed for Portsmouth and was later seized in Operation Catapult on 3 July. There was no incident. She was given to the Free French a week later and became a floating AA battery in Portsmouth, until disarmed on 31 March 1941, used as an accommodation ship, then sent to Loch Striven in Scotland to act as target for the “Highball” bouncing bomb trials (9 May-December 1943), derived from “Upkeep” for Operation Chastise (Dambuster Raid). Courbet was used there as depot and target ship. Later she was to be used as “Gooseberry” breakwater at Sword Beach after the Normandy landings, towed from Weymouth on 7 June by tugboats, with her engines and boilers removed and replaced by concrete. She was scuttled on 9 June off Sword Beach but hit by a “Neger” manned torpedoes on 15–16 and 16–17 August, but remained in place. She was slowly scrapped postwar, a work ultimately complete in 1970.

Jean Bart (Océan) (1911)

Jean Bart (Océan) (1911)

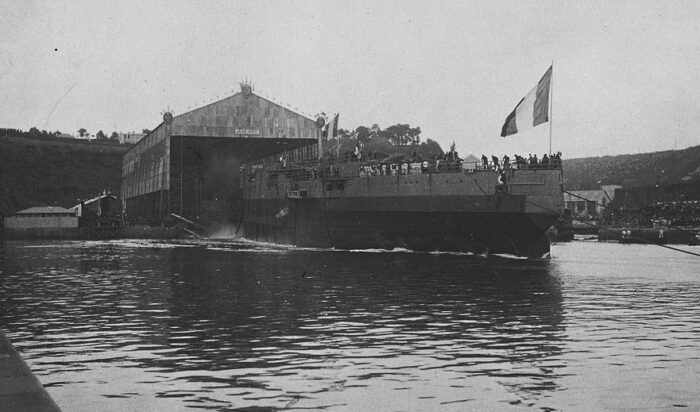

Launch of Jean Bart in 1911

Jean Bart was laid down at Arsenal de Brest in Brest on 15 November 1910, launched on 22 September 1911 and commissioned on 5 June 1913. She was renamed “Ocean” in 1936 but partially disarmed in 1938 as training ship in Toulon, not scuttled in November 1942, destroyed in an allied raid in 1944, finished off by the Germans. Ordered on 11 August 1910 after the privateer Jean Bart, laid down on 15 November 1910 at Arsenal de Brest, she was launched on 22 September 1911, completed on 2 September 1913 for F60,200,000. She visited Dunkerque, birthplace of her namesake on 18 September, then fully commissioned on 19 November with Courbet, assigned to the 1st Battle Division, 1st Battle Squadron, 1st Naval Army at Toulon. On 24 June 1914 she sailed with her sister France completing her trials and carried Pdt. Raymond Poincaré on 16 July for a state visit to Saint Petersburg in Russia, saluting en route the battlecruisers of the German I Scouting Group. She was in Kronstadt on 20 July, later visited Stockholm on 25–26 July but abbreviated the visit due to tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. She was in Dunkerque on 29 July and on 2 August, underway from Brest to Toulon, reunited off Valencia on the 6th Courbet, Condorcet and Vergniaud and escorting a troop convoy.

Under Boué de Lapeyrère, now commander, she was sent to the Adriatic, in an attempt to provoke the Austria-Hungary Navy into battle. She took part in the action off Antivari. Boué de Lapeyrère transferred his flag from Courbet to Jean Bart. On 1 September, she bombarded Cattaro and lost her flag to Paris on 11 September. After uneventful sorties and cruises along the Greek and Italian coasts, she was torpedoed on 21 December by the Austro-Hungarian U-12 off Sazan Island. The torpedo punctured a store in the bow, which was flooded by 400 tonnes (390 long tons). She reached Cephalonia for temporary repairs, completed in Malta from 26 December to 3 April 1915. From there, patrols in the Ionian Sea were restricted. She was withdrawn to Bizerte to cover the Otranto Barrage. On 27 April 1916 this was Argostoli with reduced crews (see above) and with shortages of coal. After months without proper training it was estimated she lost 50% of her capability and by July 1918, she left Corfu for maintenance in Toulon, as part of the 2nd Battle Division, 1st Battle Squadron.

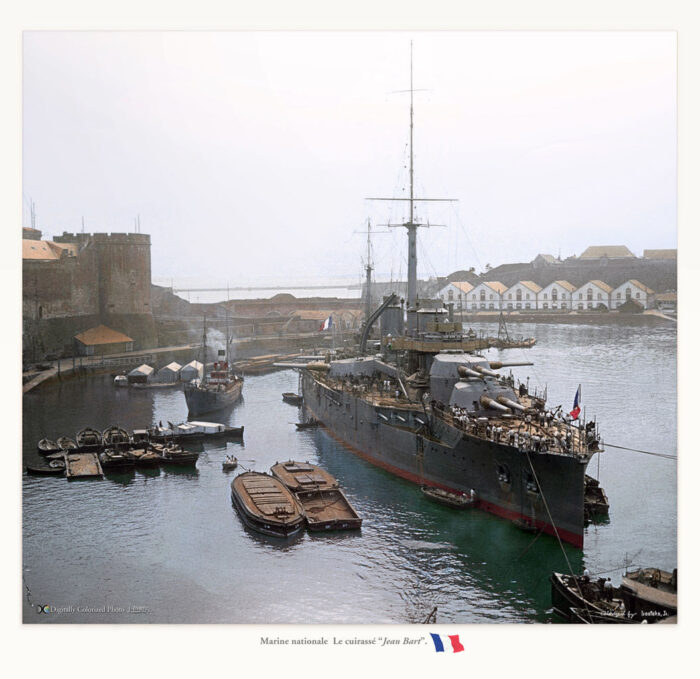

Jean Bart in Brest, colorized by irootoko Jr

After the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October, she took part in the occupation of Constantinople. In early 1919, she was transferred to the Black Sea to support the “whites” against the advancing Bolsheviks. She was bombarding Bolshevik troops advancing on Sevastopol on 16 April, but the crew was on strike on 19 April, inspired by socialist sympathisers. Jean Bart’s captain restored order and mustered a landing party but faced mutiny. Vice-Admiral JF. Charles Amet met the mutineers’ demands for leave and the sailors ashore mingled with a pro-Bolshevik demonstration, to be challenged by a company of Greek infantry, opening fire, as Jean Bart’s landing party, making 6 sailors wounded, one fatally. Delegates from other mutinous crews were forbidden aboard. Three crewmen were sentenced to prison, later commuted in 1922. Back to Toulon on 1 July, Jean Bart was placed in reserve. She was in 1st Battle Squadron with Courbet and Paris, then Mediterranean Squadron from July 1921. In June 1923, in exercises off the coast of North Africa. She would have two refits between 12 October 1923 and 29 January 1925. In mid-1925 she took part in the Atlantic Ocean manoeuvres with Courbet and Paris, stopping at Saint-Malo, Cherbourg and back to Toulon on 12 August. In refit from 12 August to 1 September 1927 she was decommissioned on 15 August 1928 for a full overhaul modernization from 7 August 1929 to 29 September 1931, recommissioned on 1 October as flagship, 2nd Battle Division (Rear Admiral Hervé). She had machinery trials in February 1932 and port visits (Bizerte, Crete, Egypt, French Lebanon, Corfu, Greece) in April-May. She then carried the flag of Rear Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva from August, refitted from 10 October to 24 November, with exercises off Corsica and 1933 port visits in French North Africa, Majorca, Spain and Casablanca. She suffered a collision on 6 August with Le Fortuné (DD) in Toulon, repaired 8-15 August. From 20 April to 29 June 1934 she was in manoeuvres and port visits until her unit was disbanded on 1 August. She was squadron flagship, assigned to the Training Division on 1 November, school for stokers and signalmen, with a last cruise on 15 June 1935.

The Battleship Ocean in Toulon circa 1939, Official U.S. Navy photo NH 55720 from the U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command

An inspection revealed her poor condition, so she skipped her third refit unlike her sisters, being hulked, disarmed in Toulon by 15 August and became an accommodation ship for the naval schools, renamed Océan on 1 January 1937 (named required for the sister ship of Richelieu), and captured intact by the Germans on 27 November 1942 during Operation Lila. She was used for experiments in late 1943 (shaped-charge warheads for the “Mistel” composite aircraft). One 8,000-pound (3,600 kg) warhead was placed on the front of the main-gun turrets, reinforced by an additional 100 mm (3.9 in) plate. The high-velocity jet penetrated through the additional armour, 300 mm (11.8 in) turret-face, 360 mm rear armour, front and rear of the aft turret, the CT and decks over 28 metres, showing this was a success. She was sunk by Allied aircraft in 1944 (Anvil Dragoon), raised for scrapping from 14 December 1945.

France (1912)

France (1912)

France was laid down at Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire in Saint-Nazaire, on 30 November 1911, launched on 7 November 1912 and commissioned on 15 July 1914. She was formally declared completed on 1 July 1914, carrying President Raymond Poincaré to Saint Petersburg from 16 July, with Jean Bart, arriving at Kronstadt on 20 July. She was later in Stockholm, but missed Copenhagen due to rising tensions for Dunkerque on 29 July. From 3 August she departed Brest for Toulon via Valencia, Spain to meet Courbet and Condorcet, Vergniaud, meeting a troop convoy, escorted to Toulon. France from 10 October was assigned to the 2nd Battle Squadron, 1st Naval Army, sent to the Adriatic Sea. After Jean Bart was torpedoed by U-12, she was sent in Navarino Bay. She sortied on 11 January 1915 (false alarm), later patrolled the Ionian Sea and was later in May sent to Bizerte to cover the Otranto Barrage. A fire broke out aboard on 25 July, so she sailed back to Toulon for repairs until 14 October. She became flagship for Vice-Admiral Louis Dartige du Fournet, 1st Naval Army in Malta. On 27 April 1916 she was based in Argostoli, Cephalonia, lost her flag to Provence on 23 May and depleted from her crews (transferred to shios). In 1917 she was in Corfu as well, stuck due to coal shortages, until 1918, leaving only for maintenance. On 1 July she was in the 1st Battle Division, 1st Battle Squadron and after the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October she took part in the occupation of Constantinople.

In early 1919 she became flagship of Vice-Admiral Jean-Françoise-Charles Amet with Jean Bart sent in the Black Sea to deal with the Bolsheviks, bombarding and repelling their advanced on Sevastopol on 16 April, forcing them to retreat. But internal dissent in her crew, with many bolshevik sympathisers, flared out as a strike and near-mutiny. The following day, her captain still could find an arrangement, so Amet hoped to deflate the situation by letting crewmen ashore. However, they mingled with a pro-Bolshevik demonstration and had to be dealt with a landing party from Jean Bart. The situation was solved when their demand to take the ships home was met on 23 April via Bizerte to Toulon. 26 crewmen were sentenced to prison upon her return, commuted in 1922 by PM Poincaré.

On 1 July, she was in the 1st Division, 1st Squadron, later Eastern Mediterranean Squadron, 2nd Battle Squadron under Rear-Admiral Louis-Hippolyte Violette, Mediterranean Squadron from July 1921. With Bretagne she hosted HMS Queen Elizabeth and Coventry in a port visit to Villefranche (18 February-1 March 1922). They were in gunnery exercise on 28 June on the former Austro-Hungarian SMS Prinz Eugen as target, sinking her. On 18 July, France, Paris Bretagne made a cruise in the Bay of Biscay-English Channel. But on 25/26 August, France struck an uncharted rock while entering Quiberon Bay, at 00:57. Her after boiler room flooded quickly, she lost all power and working pumps died, at 01:10. Her 5° list only aggravated, and by 02:00 she was abandoned by order and capsized two hours later. Bretagne and Paris rescued all but three. Her wreck was BU in 1935, 1952 and 1958. The later enquiry concluded that, since the map used was incomplete, no blame could be attributed to the captain and navigation officer, albeit the damage control party showed lacklustre results, which led to further training and new procedures afterwards.

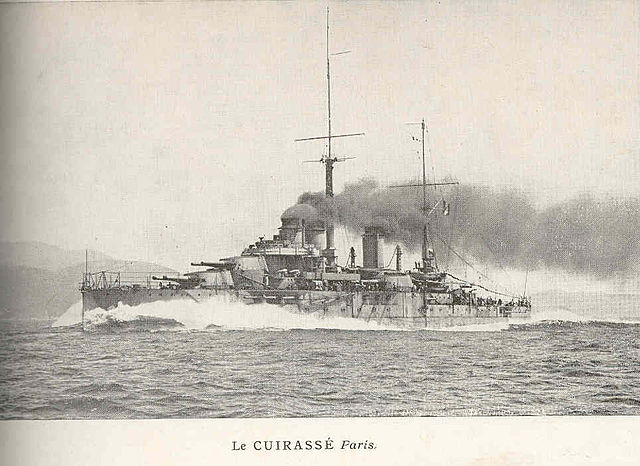

Paris (1912)

Paris (1912)

Batteship Paris, colorized by Irootoko Jr.

Paris was ordered on 1 August 1911 at Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée, La Seyne at a cost of F63,000,000, laid down on 10 November 1911, launched on 28 September 1912 and completed on 22 August 1914 and commissioned on 1 August 1914. Due to the rising tensions in Europe by mid-1914, her commission was rushed, before a formal completion on 14 August, assigned to the 1st Division, 2nd Battle Squadron, 1st Naval Army, from 5 September.

She was in gunfire support for the Montenegrin Army until U-12 hit Jean Bart on 21 December, so she was sent to Bizerte as cover the Otranto Barrage. Next, Corfu in 1916, depleted from her crews, and pretty much inactive due to coal shortages until the end of the war. She sailed to Pola on 12 December 1918 to supervise the surrendered Austro-Hungarian fleet until 25 March 1919. She provided cover for Greek troops as part of the Occupation of İzmir from May 1919 and sailed to Toulon on 30 June 1919 but collided with the destroyer Bouclier on 27 June 1922.

She had her first modernization overhaul between 25 October 1922 and 25 November 1923. Next she supported an amphibious landing at Al Hoceima by Spanish troops (1925 3rd Riffan war) in French Morocco. She destroyed coastal defence batteries but took six hits. She departed on October as flagship, refitted from 16 August 1927 to 15 January 1929 at Toulon and returned as flagship of the 2nd Division, 1st Squadron until 1 October 1931. Furthermore, she was then used as a training ship, overhauled a third and last time between 1 July 1934 and 21 May 1935.

Battleship Paris – By Georges Clerc-Rampal, University of Washington Coll.

In 1939, Paris with Courbet formed the 5th Squadron, transferred to the Atlantic for training duties but soon restored to full operational status on 21 May 1940 by Amiral Mord, notably receiving six twin Hotchkiss 13.2 mm (0.52 in) HMGs, two single 0.5 in Browning machine guns at Cherbourg. Paris left Le Havre on 6 June for gunfire support on the Somme front, covering the evacuation by the Allies. She was useless in this mission due to the lack of spotting aircraft. Later she defended Le Havre against German aircraft but due to her weak AA, she was hit by a bomb on 11 June. She sailed for Cherbourg for temporary repairs while being flooded by 300 long tons (305 t) of water every hour. She was transferred to Brest on 14 June and evacuated from there 2,800 men on 18 June. At the Armistice, she was docked at Plymouth. On 3 July 1940 (Operation Catapult) she was forcibly boarded and seized. She became a depot ship, barracks ship for the Polish Navy until 1945. By 21 August she was towed to Brest as depot ship until sold for scrap on 21 December 1955, BU at La Seyne from June 1956.

Read More/Src

Books

Robert Gardiner et Roger Chesneau Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-21, 1922-47.

Éric Gille, Cent ans de cuirassés français, Nantes, Marines éditions, juin 1999.

Michel Bertrand (préf. Contre-Amiral Chatelle, photogr. SHD-Marine), La Marine française : 1939-1940. Éditions du Portail 1984

Jean Meyer et Martine Acerra, Histoire de la marine française : des origines à nos jours, Rennes, Ouest-France, 1994

Michel Vergé-Franceschi (dir.), Dictionnaire d’Histoire maritime, Paris, éditions Robert Laffont, coll. « Bouquins », 2002

Alain Boulaire, La Marine française : De la Royale de Richelieu aux missions d’aujourd’hui, Quimper, éditions Palantines, 2011

Rémi Monaque, Une histoire de la marine de guerre française, Paris, éditions Perrin, 2016

Jean-Michel Roche, Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours, t. II : 1870-2006. Rezotel-Maury 2005

John Jordan et Philippe Caresse, French Battleships of World War One, Barnsley, Seaforth Publishing, 2017

Links

on forummarine.forumactif.com/

Wiki EN

irootoko_jr colorized photos about the Courbet class

battleships-cruisers.co.uk

on navypedia.org

commons.wikimedia.org/ photos

Videos

Model Kits

On scalemates! 1:350, 1:700.

Ex: SSMODEL 1:350, Armo 1:700.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign