Sangamon class Escort Aircraft Carriers

US Navy 4 ships (Converted, Commissionned Aug. – Sept. 1942): USS Sangamon, Suwanee, Chenango, Santee

US Navy 4 ships (Converted, Commissionned Aug. – Sept. 1942): USS Sangamon, Suwanee, Chenango, Santee

WW2 US Carriers:

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classFrom civilian oilers to aircraft carriers

The former Cimarron-class oilers launched in 1939 for civilian use, were requisitioned for the supply needs of the fleet, recommissioned by the U.S. Navy in 1940–1941 as AO28, 29, 31 and 33. Later in early 1942, it was decided to convert them as escort aircraft carriers, a choice constrained at the time by the shortage of MARAD type C3 cargo ships for extra conversions.

The USN desperately needed new escort carriers, so was decided to attempt the Long Island type conversion to these four oilers, a work started in February-March and which took around six months, until the ships were recommissioned in August 24 (Santee), 25 (Sangamon), and then Chenango (19 September) and Suwanee (24 September).

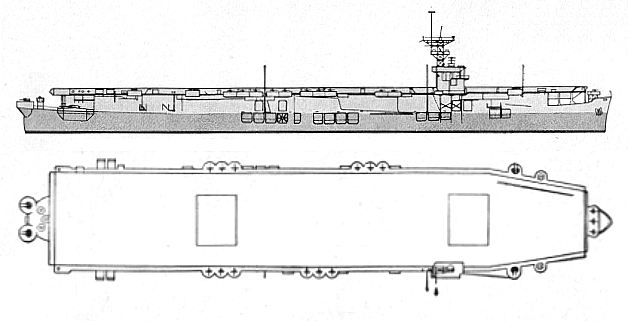

Due to their larger size, these were the largest escort carrier conversions to date. They still managed to be faster than C3 conversion with 18 knots, roomier, and thus carrying 31 aicraft in normal condition, more than the C-3 based Bogue (28) for example. The larger hull also authorized more armament to be installed, twice as many 40 mm and two more 20 mm as completed.

Slightly larger they were designed as carriers from keel up. Since they were at the core designed as T3 tanker oilers, their machinery space was aft so the smokestacks were relocated on both sides aft also, at the flight deck level. Excellent first examples of Oiler conversions, they were found roomy, tough, and with a larger flight deck enabling larger aicraft, plus good stability on high seas. The Sangamons could also operate dive bombers, unlike other CVEs mostly carrying smaller F4Fs on board.

As fleet oilers

The Sangamon were named after rivers, a practice for oilers taken into naval service. USS SANGAMON (AO-28) was one of twelve tankers built on a joint Navy-Maritime Commission, design later duplicated by the T3-S2-A1 type laid down as ESSO TRENTON (MC hull 7) on 13 March 1939. She was originally built at the Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., Kearny, N.J. as a special wartime standard. Launched on 4 November 1939 (sponsored by Mrs. Clara Esselborn), she was operated by the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey), acquired by the USN on 22 October 1940, Renamed SANGAMON as the fleet oiler AO-28 and recommissioned the following day with Comdr. J. R. Duncan in command.

After service off the west coast and in Hawaiian waters, USS SANGAMON started a round of service with the Atlantic Fleet in the spring of 1941, operating together with the Neutrality Patrol by carrying fuel from the gulf coast oil ports to bases on the east coast including as north as Canada and Iceland. On 7 December 1941 she was at Argentia, offloading, before departing south to load another cargo, but this time on a tighter time frame.

After arrival in January 1942, she was designated for conversion to an auxiliary aircraft carrier and on 11 February sailed to Hampton Roads to be reclassified AVG-26 and on 25 February, decommissioned and converted at the Norfolk Navy Yard. During the spring and summer the USN expressed the need of a large fleet of auxiliary/escort carriers increased and outside Sangamon, three other CIMARRON class oilers were concerned as well as twenty C-3 merchant hulls (the future Bogue class), sped up. In August 1942, so seven months after start, USS SANGAMON was ready. On the 20th, she was redesignated ACV-26; and recommissioned on the 25th under command of Captain C. W. Wieber (see career).

For more about the ships themselves, they were the T3, an improved, larger versions of the T2 Tankers were saw recently. Designed in 1940 under the supervision of the United States Maritime Commission, they were part of the T3-S2-A1 Cimarron-class oilers (35 ships, AO-22-33, AO-51-64, AO-97-100). “AO” stands for “” . They were the USN underway replenishment class of oil tankers designed in 1939.

They had a full load displacement of about 24,830 tons, 553 ft (169 m) x 75 ft (23 m) x 32 ft 4 in (9.86 m), propelled by Geared turbines, twin shafts for 13,500 shp (10,067 kW) and 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h), a range of 12,100 nmi (22,400 km; 13,900 mi) and Capacity of 146,000 barrels (23,200 m3). Complement was 304. They were USN oilers and thus, well armed for the Pacific, with four 5-inch/38 caliber guns, four twin 40 mm gun mounts, four twin 20 mm gun mounts.

Conversion Design

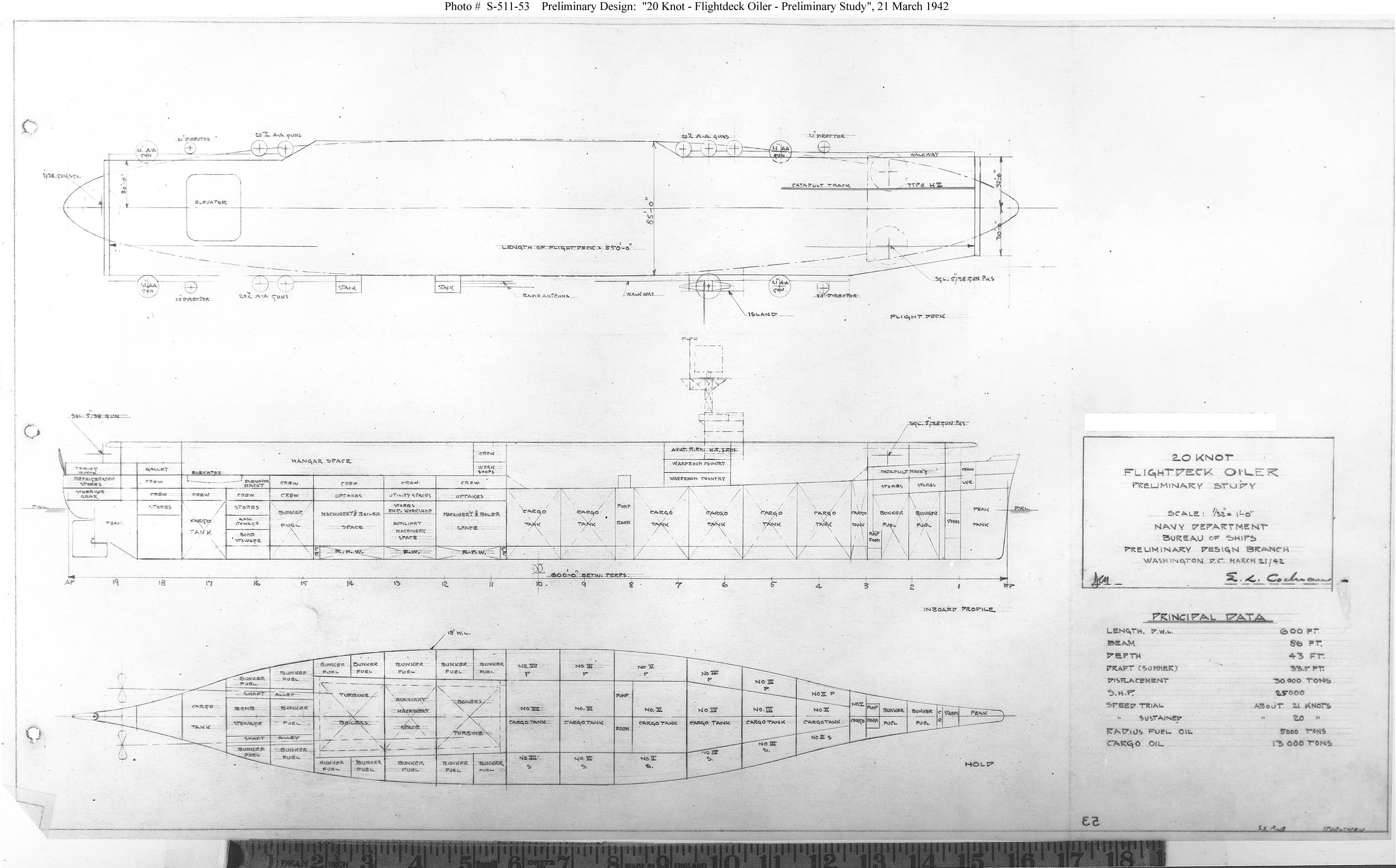

BuShips’s S-511-53 20 knots Flight Deck Oiler conversion design, prelim. study dated 21 March 1942.

The conversion consisting in deleting her superstructure, masts and all related oil-management pumps and tanks, adding a flight deck 502 feet long, 81 feet wide, with two elevators, a full size hangar, a catapult forward port, a sonar gear, aircraft ordnance magazines and work shops, stowage space for aviation spares under and in the hangar (suspended undere the roof as usual practice). Accommodations were also enlarged and rationalized to house her the aviation complement of mechanics, pilots and officers.

Hull and general specifications

The had a small island superstructure starboard, three decks high, with open bridge fo C&C, and a lattic mast supporting various radars. Unlike the C3 conversion, the basic hull was longer, roomier, and characterized by openings under her hangar for the storage room.

Powerplant

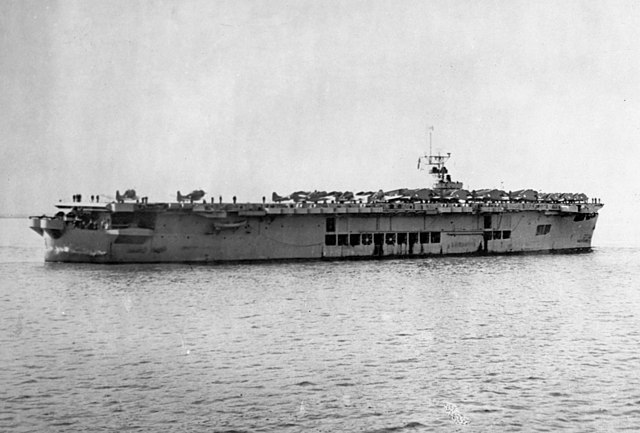

USS Sangamon in sea trials, Aug. 1942

Based on the T3 Tanker machinery they were designed to reach 18 knots, thanks to a pair of steam turbines driving two shafts propellers. These sets of General Electric geared steam turbines were fed by four Marine-grade Babcock & Wilcox boilers for a global ouptut of 13,500 shp. For endurance, they kept some of her former holds, carrying a generous 4,780 tons of oil, enough not only for a very generous range of 23,900 natiical miles at 15 kts, but also allowing them to carry refuelling at sea of other ships like their own, always fuel-hungry escort destroyers, which happened in several occasions.

Armament

Final armament:

-Two 5 inch guns in sponsons aft, below the deck level, with a limited arc of fire. Standard Mark 15 127 mm/51: They could elevate −15° to +85°, had a rate of fire of 15 rpm ideally (manual loading), with a muzzle velocity of 2,600 ft/s (790 m/s), Optical telescope sights.

-8 x 40 mm/70 Bofors Mk.1.2: In twin and single mounts (22 in 1945)

-20 x 20 mm/70 Mk.4 Oerlikon AA guns: located around the flight deck in individual positions.

During the war, they received additional AA: In 1945, two quad 40mm/60 Mk 2, ten twin 40mm/60 Mk 1, 21 single 20mm/70 Mk 10 AA.

Radars

For communications she used an intercom, and a backup pipe system running from the open bridge on top. There were two large mast for antennae located on the port side. They supported a set of 12 radio wires. The bridge’s main derrick located at its supported at first a single SC radar, later in 1944 complemented by a SC radar. By 1946 they were upgraded to a SC-2 and an SG radar. They still carried it when decommuissioned but in the 1950s all carried an SLR-2 ECM suite.

The first platform supported light projectors. In front of the derrick on the open bridge’s deck was mounted a telemeter for gunnery operations. During her 1943 refits they obtained a centralized combat system, installed deep within. Fur service boats were suspended below the flight deck’s side overhangs fore and aft, but inflatables were carried all along the side, folded.

Aviation Facilities

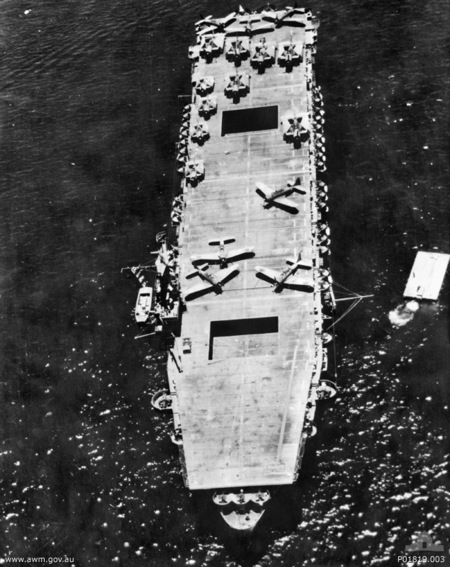

SBDs on USS Sangamon, Operation Torch, Nov. 1942.

Their flight deck was of the same simple, stright design of the early C3 conversions, with a single H2 catapult fitted on the starboard side, oblique to follow the forward flight deck narrowing. This allowed also a second place to be parked alongside, wings unfolded. They had two lifts of standard size, located centerline, one forward, at the same hight of the island, and the other aft at the same height of the second triple 20 mm mounts mounts;

To stop planes, the Sangamon class had nine arrestor cables running all the way past mid-ship. They were followed by three extra cables (unweighted) and a crash barriers at the hight of the island.

Operations were made from the open bridge, but there was an operating room in the bridge with a model to carefully plan aircraft parking and launch/recovery operations more in detail. The hangar ran for most of the flight deck’s lenght, and was tall enough to accomodate all USN models in the inventory. The enclosed hangar could be ventilated through eight shutters along the sides. Inside, there was a sprinkler system for extinguishing fires and a single fire fighting OM. Details of the location of avgas tanks and safety of the pump/piping system are not known as conversion blueprints are unavailable.

Aviation Group

In absolute terms, the air group of 31 aircraft total (max capacity inside the main hangar) could in reality be boosted to 50+ with parked aircraft in taxiing mode (freeing the forward part for taking off) or “full monty” if the planed are disembarked by cranes on arrival. The deck space could accomodate well over 70 planes, wings folded.

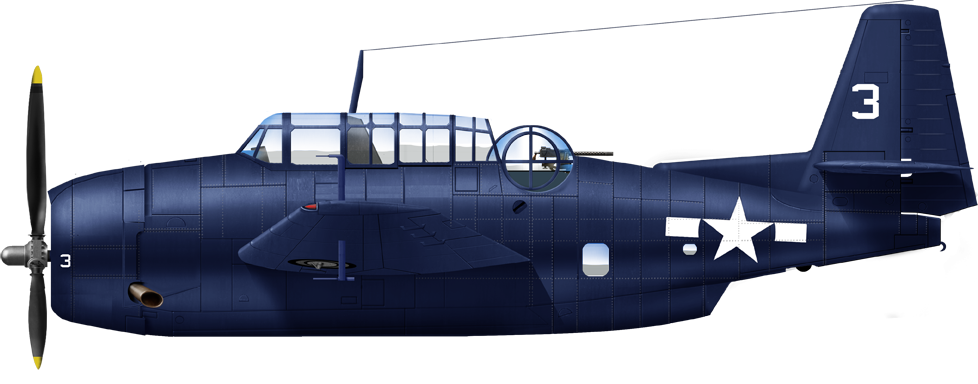

According to Navypedia, USS Sangamon entered service with 12 F4F-4 Wildcats, 9 SBD-3 Dauntless and 9 TBF-1 Avenger (total 30). It was the same for Santee as commissioned, but with 13 TBFs, making for a total of 34.

USS Sangamon apparently had more modern F6F-3 Hellcats and same for the rest; Chenango however in October 1944 had 24 Hellcats and not TBF, but nine TBM-1 (the late GM Avenger). In April 1945 USS Santer had 18 F6F-5 Hellcats, equipped as fighter bombers, and 12 TBM-1 used only as bombers. Both AVC 26 and 27 carried also a Curtiss SOC Seagull, and one of several F4F-P Wildcat reconnaissance planes.

F4F-4 Wildcat, USS Santee, Atlantic, Nov. 1943.

F6F-3 Hellcat, USS Suwanee, 1945.

Grumman TBM-3 Avenger, USS Sangamon, circa 1945.

USS Sangamon in 1944, in measure 5-O ocean blue – old author’s illustration: More modern and HD awaited.

Sangamon class (1942) specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 168.55 x 22.8/32 x 9.32m (553 x 105 x 30 ft) |

| Displacement | 10,494 long tons standard, 23,875 tons FL |

| Crew | 1080 in 1945 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts GE turbines, 4 Babcock & Wilcox boilers |

| Speed | 13,500 shp, 18 kts |

| Range | Oil tons = |

| Armament | 2x 5-in/51 DP guns, 4×2 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, 12x 20mm/70 Mk 4, 31 aircraft |

| Armor | None |

Legacy: The “Bay” class

The experience was judged satisfying enough the admiralty ordered a new class, from the keel-up, to be mass-produced at Todd-Pacific Tacoma from the fall of 1943 to the end of the war: The Commencement Bay, or just “Bay”. The latter were about the same size, but their dedicated design was improved in a massive way, they were one knot faster, were roomier and could carry 33 aircraft (versus 27 on the Casablancas) plus a heavier armament. Their hull design however, machinery and underwater accomodation were mostly based on the T3 oilers. In all, 23 were planned (CVE-105 to 127), named after various land-sea battle, as they were intended to bring amphibious air cover, like the Casablanca class (the role given to modern Amphibious Assault Ships).

On the total, planned FY1944 and all laid down at Todd-Pacific Tacoma between September 1943 and March 1945, the war ended before most could see action in the Pacific. The last four were cancelled. Only USS Commencement Bay (CVE-105) comp. 27 November 1944, USS Block Island (CVE-106), comp. 30 December 1944 and USS Gilbert Islands (CVE-107) Comp. 5 February 1945 saw significant actions. Most of the others were completed in April to July 1945, and by the time their crews were ready for action, the war was practically at its end. Placed in reserve, many would be reactivated for the war in Korea.

A note about the CVHE conversion

USS Thetis Bay, CVHE-1, lead ship of the helicopter carrier conversion.

In the early cold war (1955) they were reclassed as helicopter carriers for ASW escort, but the conversion was cancelled. The concept of CVHE (H standing of course for “helicopter”) was a logical answer to the “Whiskey fear” of the 1950s when the Soviet Union could muster hundreds of Project 613 submarines, basically copies of the WW2 Type XXI, roaming the Atlantic. A plan was quickly setup to convert back many of the “mothball fleet” CVEs of WW2 into useful escort vessels again. Although the new generation of sea patrol planes, piston-propelled such as the Douglas Skyraider could be used for ASW missions, helicopter were thought as the best answer. The limited size of thickness of the decks allowed to carry about thirty or more helicopters onboard the Sangamon-class CVEs.

In the end the conversion was planned, but cancelled after a few years. In their place the larger and more modern “Bay” (but also Casablanca) class vessels were chosen for such conversions, not the venerable and battered Sangamon class. CVHEs were also later used as CVHA, for assault, their 21 helicopters used to carry and land USMC troops, later redesignated LPH.

Gallery

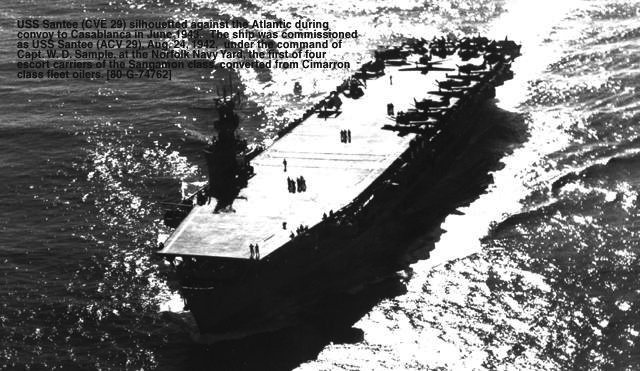

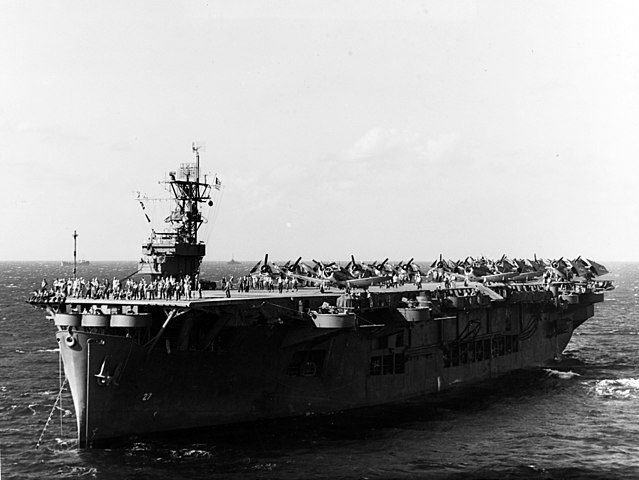

USS Santee at anchor, late 1942

Japanese A6M kamikaze hitting USS Suwannee, Battle of Leyte 25 October 1944

Grumman TBF Avenger of VT-60 in flight over USS Suwannee, circa 1944

Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat from VF-60 launched from USS_Suwannee, circa_1944

USS Suwannee underway to Puget Sound, 31 January 1945

USS Santee, date unknown

Aircraft warming up before launch close to the island

FM-2 on CVE-89, October 1944

F4F Wildcats on USS Santee, late 1942

F4F-4 Wildcats of VGF-29, USS Santee November 1942

SBDs on USS Santee, 1942-43

Douglas SBD-3s, VGS-29 USS Santee, 27 December 1942

Flight deck of USS Santee, SBDs in November 1942

TBF being hoisted aboard USS Santee, coast port

USS Hambleton (DD-455) and USS Sangamon underway in 1942;

USS Sangamon in the Solomons, 1943.

Operation Torch, USS Chenango taxiing P40 Warhawks in Nov. 1942

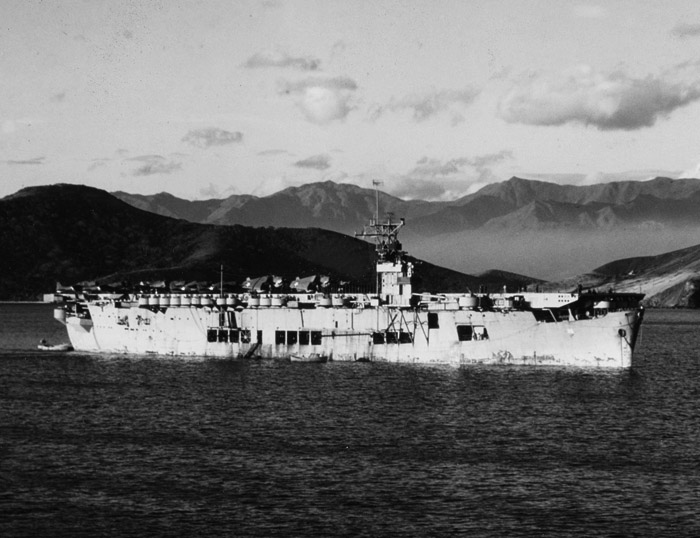

USS Chenango in Noumea, Jan 1943

USS Chenango underway in 1944

Air group 35 planes and crew posing on her flight deck

The Sangamon class in action:

After a short service in the Atlantic and Mediterranean (Operation Torch), all four CVEs spent almost all their active career in the Pacific, following the supply fleets for the USMC and taking part in the Guadalcanal and Somomons Campaign, The Marshall, Carolines, Philippines Campaign, participating also in the Battle of the Philippines in June 1944 and of Leyte in October 1944, being heavily targeted by Kamikaze but surviving.

In general, they were really appreciated as a conversion due to their very large fuel capacity, enabling them to refuel their own escort destroyers, but also large medical facilities, helping them to save many lives, and of couse a larger air group than C3 hull conversions CVEs, giving them a greater deal of flexibility in operations, between a defensive CAP, ASWP, and simultaneous air strikes. They collectively earned 41 battle stars and several presidential citations for their service.

USS Sangamon (CVE-26)

USS Sangamon underway in the South Pacific, 1943

Originally Esso Trenton (T3 tanker oiler) built by the Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, she was operated by Standard Oil, New Jersey making regular trips from gulf coast ports to the east coast. Requisitioned by the US Navy she re-entered service as a fleet tanker, USS Sangamon. She was then converted into an aircraft carrier. After conversion, USS Sangamon was recommissioned as ACv 26 and recommissioned on 25 August 1942, she made her Shakedown in Chesapeake Bay and off Bermuda followed by a stop to the yard for post-trials fixes andd improvements, notably to her ventilation system. On 25 October, even though everything was not fixed, she was ordered to join Task Force 34 mobilized for Operation Torch.

Operation Torch and Mediterranean Campaign

USS Sangamon underway to North Africa in November 1942

Her first action was to be part of the invasion fleet, under command of Capt. C. W. Wieber. During the invasion of North Africa she was assigned to the Northern Support Force, arriving off Port Lyautey on 8 November 1942. She barely had time to train with her rookie air group, the Composite Squadron 26 (VC-26) which composed her Wildcats combat air patrol (CAP), and an anti-submarine patrol (ASP) with nine, factory fresh first generation Grumman TBF Avengers, plus her ground support group composed of SBD Dauntlesses. She allegedly deployed a SOC Seagull fo reconnaissance. After support ing troops duing the few days of initial operations, at mid-November, she returned to Norfolk for a small refit, and she sailed for Panama and the Pacific.

A Sangamon class in 1942

The Pacific theater

By mid-January 1943, SANGAMON had arrived at Efate, New Hebrides and entered the Carrier Division 22 (CarDiv 22) operating from New Caledonia, to the New Hebrides and Solomons area for eight months. She was soon reunited with USS SUWANEE and CHENANGO her sister ships (90 plane between them) to provided cover for for the vital resupply convoys en route to Guadalcanal and assault forces that were inbound on the Russells. She became CVE-26 on 15 July 1943 and Efate, then Espiritu Santo became her new operating base in August 1943, followed by a voyage back to the US in September, for an overhaul at Mare Island.

The Marshall Campaign

There, she received a modernized AA battery, radars and equipment for her flight deck as well as a fully functional, standardized combat information center. This was completed and she departed on 19 October San Diego with the air group VC-37, heading for Espiritu Santo. She arrived on 13 November, refuelled and rendezvoused with Task Force 53, proceeding next on the 20th to the Gilberts, on where she stays as support, for the assault on Tarawa. In the first two days her attack planes strafed and bombs enemy positions on Tawara and until 6 December, her fighters daily patrolled as part of the CAP, also making ASP missions to protect the escort carrier group.

Once complete, she was back to San Francisco and in early January 1944 trained off southern California, in the West, and back to Pearl Harbor, she was assigned to the fleet assaulting Kwajalein (Marshalls). At 16:51 on the 25th, her luck ran out: Despite a routine flight operations, one of her returning F6F Hellcat fighter failed to hook a wire on landing, and went through the barriers to crash into the forward flight deck jam-packed of parked planes, wings folded. Her belly tank detached and skidded forward, spewing flaming fuel quick inflamed, engulfing the parked group, and then spreading between these, causing further fiery explosions and ammunition detonations. Flames eventualy leaked the bridge, so her control became extremely difficult, but at least the captain ordered she was turned out of the wind to combat fire, and by 16:59, it was under control, but she deplored 7 kills, 7 seriously burned or injured, and from the 15 who jumped over the side, 13 were picked up.

The Marianas Campaign

After temporary repairs at sea, she spent up to mid-February resuming cover of the occupation of Kwajalein before proceeding to Eniwetok, covering the landing forces (17th-24th). She departed later the Marshalls back to Pearl Harbor and full repairs. On 15 March, the CVE got underway again. Departing soon, she joined Task Group (TG) 50.15 fast carrier force on 26 March, and up to April, she escorted TG 50.15, north of the Admiralties, refuelling and

resupplying after strikes on the Palaus. After returning to Espiritu Santo she headed for New Guinea, attached to the 7th Fleet, to cover the assault at Aitape (22-24) and retired to Manus, for rest and resupply two days, and back at Aitape for patrolling the area until early 5 May.

After a run to Espiritu Santo, she departed on 19 May to take part in Rehearsals for the Marianas campaign. On 2 June, she sailed for the Marshalls and joined TF 53, stopping at Kwajalein, then to the Marianas. On 17-20 May, she patrolled east of Saipan as part of the backup force for TF 52, and covered the assault on Saipan proper. Soon, the Battle of the Philippine Sea took place and she was detached to join TF 52 and by July, supported the occupation of the Island, before retiring to Eniwetok. On 13 July-1st August she covered prelimanry attack for Guam. On 4 August, she was in Eniwetok to resupply, then Manus for a prolongated rest until September.

On 9 September 1944, USS SANGAMON departed Seeadler Harbor, Manus, for Morotai and on the 15-27th covered Allied assault, bombing and strafing missions, on map and on demand on all Japanese positions and airfields at Halmahera. She was back at Seeadler Harbor (1-13 October) and was reassigned to TG 77.4, escorting the carrier group of the Leyte invasion force.

Sangamon at Leyte

Battle of Samar, USS Sangamon is hit;

This force comprised no less than 18 CVEs, and for easier management, was split into Task Units 77.4.1, 77.4.2, 77.4.3 (“Taffy”). At first she was assigned to Taffy 1 (east of Leyte Gulf, northern Mindanao). Meanwhile “Taffy 2” was posted at the entrance to Leyte Gulf and famous “Taffy 3” off Samar.

Before D-Day (20 October) regular missions were flown in support of advanced units, performing strikes against Leyte and Visayan airfields. The day of the landings, she covered the transport areas, but also came under enemy air attack. She was struck by an A6M Zeke Kamikaze, by a bomb at the main deck level. The detonation cut out a 2×6 feet section of plating, but the aicraft crashed at sea 300 yards away. The bomb did not penetrated and she could resume operations against Enemy airfields afterwards.

On 24 October her CAP was busy fending off more waves of Kamikaze over the landing area. On the 25th, she sent part of her air group out to the Mindanao Sea to search and destroy Japanese survivors of the Battle of Surigao Strait, while her other was a CAP toward Leyte. Soon, news were received that “Taffy 3,” 120 miles northwards, was under attack, to what was later known as the Japanese Center Force sneaking by night through the San Bernardino Strait. In 50 min. her CAP was sent to Samar to assist.

At about 07:40, Taffy 1’s planes were recovered, rearmed, and launched again when hit by a first massive strike of Kamikazes. Son CAPs and AA gunners were overwhelmed, and USS SANTEE took a direct hit, the ordnance going straight through her flight deck, exploding on the hangar. Others targeted Sangamon and during her fierce defense, a single 5-inch shell from USS Suwanee blasted on Kamikaze only 50 yards from SANGAMON in the “scratch my back” way. By 07:55 I-56 arrived on sight and took part in the fray, torpedoing the unfortunate SANTEE just has her heroic damage party was having fires under control. The ship soon listed, and if that was not enough, a few minutes later, an A6M “Zeke” crashed on her deck, forward of the after elevator.

Meanwhile, USS SANGAMON’s crew, in particular the exposed AA personel and deck crews were strafed, one being killed, several injured in the process. After the first wave exitnguished, her captain decided to sent her own medical

personnel to assist on USS Santee in particular. The most in need of care were brought aboard for treatment. Even if she was not hit directly, many near-misses took their toll and USS Sangamon had her steering gear malfunctioning as well as her generators and catapult. Repairs were completed just for her scheduled afternoon strikes, which gave chase to the retreating Japanese Center Force.

On the 26th, she recovered all her scattered planes, soon gathering a new CAP, with tired pilots, just as at 12:15, radars spotted enemy planes incoming from the north. Despite a staunch CAP defense, severam of these second wave Kamikaze went through and dove on Taffy 1. USS SUWANEE suffered another kamikaze hit, but Sangamon fended off attacks and went unscaved again. Like her crippled sisters, she retired on the 29th, to Seeadler Harbor. By early November, she headed back to the US for her main overhaul at Bremerton, until 24 January 1945. There, she had rocket stowage racks installed for her late F6F Wildcats and Avengers, a welcomed second catapult, modernized radar gear and extra new 40 mm AA mounyts, plus a decicated bomb elevator, additional fire fighting equipment.

Okinawa

In mid February, USS Sangamon was in Hawaii, training her crew and her new air group, notably VC-33 including F6F night fighters. On 5 March 1945 she proceeded to Ulithi, temporarily detached for TU 52.1.1, committed to the initial assault phase for Operation “Iceberg” (Ryukyus Campaign). On 21 February, she departed Ulithi as part of the Kerama Retto assault force. She also operated south of Okinawa, launching a CAP and and strikes on Kerama Retto until secured. On 1 April, she was reassigned to TU 52.1.3, and reunited with her own CarDiv 22, and sister ships for more missioned over and around Okinawa.

She was posted on the 9th, about 70 miles east of Sakishima Gunto, attacking airfields on Miyako and Ishigaki, later alternating with strikes on Okinawa and landing at Ie Shima. She made Dawn and dusk strikes plus heckler flights on airfields at night. On the 22d, her strike group founded a 25-30 aircraft just warming up on Nobara Field in central Miyako and despite Seven Ki-43 “Oscars” took off in time for interception, her attack was devastating. Bombers went back after delivering their payload but Hellcats stayed being to finish off remaining Oscars, claiming five. Her night fighters arrived later and intercepted more Japanese planes, downing four “Oscars” that night.

On 4 May, Kerama Retto became her new resupply base for upcoming operations. At 18:30, her radars spotted Japanese aicraft incoming 29 miles off soon intercepted by land-based fighters, claiming 9, but one Kamikaze went thriugh and soon took a position ideal to find a spot and attack Sangamon at 19:00, circling towards her port quarter. Her captain ordered a hard left turn while opening fire, assisted by her escorts. They eventually splashed down the plane just 25 feet off her starboard beam.

Kamikaze damage, 4 May 1945

At 19:25, another also came though her CAP and managed to avoid AA fire, and at 19:33, dropped a bomb that crashed dead center on her flight deck, the plane itself also crashing, both partly penetrating into the hangar, hurling flames and shrapnel, and fires erupted which were hard to contain. Communications from the bridge were severed, and she became out of control. Unfortunately, she turned into the wind, which spread flames and smoke. At 20:15, steering control was back in operation, so her captain ordered a course helping fire-fighting, despite water pressure was low. In addition, firemain and risers ruptured, forcing the damage party to use Carbon Dioxide bottles while other ships came alongside to assist. At 22:30 at last, after four hours of a raging inferno, everything was under control, including Communications. it was reported to the captain at 23:20, 11 dead, 25 missing, and 21 seriously wounded. All her aicraft but one were lost. She headed for previsional repairs at Kerama Retto.

Back home and decommission

After transiting to Pearl Harbor she went bacl to the United States and on 12 June, Norfolk for full repairs, suspended with the cessation of hostilities by mid-August 1945. In September, she was inactivated. She was decommissioned on 24 October 1945, struck from the Navy list (1 November), put on the disposal list and sold to Hillcone Steamship Co., San Francisco on 11 February 1948 for BU. She earned 8 battle stars for her campaign, from the sands of North Africa to the Kyushus and her three air groups each won a Presidential Unit Citation.

USS Chenango (CVE-27)

The second USS Chenango was the requisitioned fleet T3 Tanker oiler AO-31, redesignated ACV-28. She was acquired on 31 May 1941, commissioned on 20 June 1941 as AO-31 (Capt. W. H. Mays). As a fleet oiler she served in the Atlantic, Caribbean and Pacific (Hawaii). Off Aruba on 16 February 1942 she spotted a German submarine shelling a refinery, but could do little. Decommissioned at Brooklyn NyD on 16 March, she was convetrted as an escort carrier.

Her conversion complete and recommissioned on 19 September 1942 her first job was to taxiing 77 P-40 Warhawks (33rd Fighter Group USAAF) to North Africa. She sailed on 23 October with the Torch assault force, arriving at launching point on 10 November, off Port Lyautey in French Morocco. Next she was anchored in Casablanca from 13 November, refuelling 21 destroyers, before returning to Norfolk on 30 November, weathering a hurricane en route. This caused enough damage to have her repaired.

Next she was sent to the Pacific, being underway in mid-December, escorted by USS Taylor (Task Force 13). She dropped anchor in Nouméa on 18 January 1943 and joined TF 13 for air cover, supply convoys in supporting of the Solomon Islands Campaign. She flew her air groups to Henderson Field, in close support of the USMC ashore. She stayed there as a permanent sentry and her air cover allowed to save USS St. Louis and Honolulu after the Battle of Kolombangara on 13 July.

Redesignated CVE-28 on 15 July USS Chenango was overhauled in Mare Island from 18 August. Afterwareds, she was kept in home waters as a training carrier for new air groups (her old ones were fighting hard at Guadalcanal), until 19 October. When declared ready she left San Diego for the Gilbert Islands invasion force gathering at Espiritu Santo, arriving there on 5 November. She took part in the invasion of Tarawa (20 November-8 December 1943) her air group multiplying sorties to cover the advance of the attack force, another part protecting the off-shore convoys. On 29 November 1943, 21:57, Avenger TBFs of her own Air Group 35 spotted and sank the IJN I-21. She was later back to San Diego for training

Away at sea again from 13 January 1944, USS Chenango supported took part in the invation of Roi, Kwajalein, and Eniwetok, part of the Marshalls Campaign. She covered the refueling fleet units engaged in the Palau strikes an was back to resupply herself at Espiritu Santo (7 April). Next she covered the raids on Aitape and Hollandia from 16 April to 12 May and served with TG 53.7 sent in the invasion of the Marianas. Her planes targeted airfields, enemy shipping, harbor facilities, notably at Pagan Island. Her photo Recconaissance F6Fs also provided vital intel on Guam. From 8 July 1944 she covered the assault on Guam and was back to resupply in Manus (13 August).

USS Chenango off Mare Island Navy Yard 22 Sep 1943

On 10-29 September 1944, she neutralized enemy airfields in the Halmaheras, supporting the invasion of Morotai in the Philippines. From 12 October she made strikes on Leyte from 20 October with her sister ship USS Sangamon, bith repelled an attack of three Japanese planes, all splashed down, managing to capture a pilots. Their new advanced base was now Morotai, where they loaded new aircraft. USS Chenango missed the Battle of Leyte Gulf, but was back on 28 October, assisting her victorious sister escort carriers there. She wetn back home for an overhaul at Seattle, until 9 February 1945.

Based in Tulagi, Solomons on 4 March, USS Chenango trained and sortied from on 27 March, taking part in the Okinawa. Air cover was provided for the initial feint landings south, and her air group raided kamikaze bases in nearby Sakashima Gunto. On 9 April she suffered a crash-landing fighter. Fire broke out cause mahyem in the parked planes on deck. The crew however prevented serious damage. She was back in Okinawa until 11 June 1945. Later she escorted a tanker convoy to San Pedro Bay in the Philippines and from 26 July, joined the logistics force, 3rd Fleet, for the final offensive.

Receiving news of the ceasefire on 15 August, USS Chenango supported the occupation forces. She also supplied POWs and made “magic carpet” runs, starting with 1,900 Allied POW and 1,500 civilians, clearing Tokyo Bay on 25 October 1945. She had a brief overhaul in San Diego before returning to bring home veterans from Okinawa and Pearl Harbor. Back in San Pedro on 5 February she departed for Boston, to be placed there out of commission, reserve fleet, on 14 August 1946. Reclassified CVHE-28 as she was supposed to carry helicopters (which never happened) from 12 June 1955, she was eventually struck on 1 March 1959 and sold for BU on 12 February 1960.

USS Suwanee (CVE-28)

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat from VGF-27 onboard USS Suwanee, late 1942

After six months as fleet oiler, Atlantic Fleet (AO-27), USS Suwannee became AVG-27 on 14 February 1942, decommissioned at Newport News, converted, renamed ACV-27 on 20 August and recommissioned on 24 September 1942 under command of Captain Joseph J. Clark.

Less than a month after commissioning, Suwannee was underway from Hampton Roads for the invasion of North Africa. She joined Ranger as the other carrier attached to the Center Attack Group whose specific objective was Casablanca itself, via Fedhala just to the north. Early in the morning of 8 November, she arrived off the coast of Morocco and, for the next few days, her Grumman F4F Wildcats maintained combat and anti-submarine air patrols, while her Grumman TBF Avengers joined Ranger’s in bombing missions. During the Naval Battle of Casablanca from 8–11 November, Suwannee sent up 255 air sorties and lost only five planes, three in combat and two to operational problems.

From 11 November she was stationed off Fedhala Roads in North Africa for anti-submarine patrols, spotting and sinking allegedly a German U-boat, but later reported as one of the three Vichy French submarines which sortied from Casablanca on Operation Torch D-Day. She remained in North African waters until mid-November 1942 before going back to Norfolk, Hampton Roads, 24 November, training there on 5 December and then reassigned for the South Pacific.

Crossing the Panama Canal on 11–12 December she arrived in New Caledonia on 4 January 1943 and for seven months, provided air cover for escort/transports/supply convoys for the marines on Guadalcanal, taking part to the Solomons campaign, stopping notably in Efate and Espiritu Santo. By October 1943 she was back in San Diego for a refit and was on 5 November back at Espiritu Santo. By mid-November she took part in the Gilbert Islands assault, and later she was reassigned to the Southern Attack Force, Tarawa. She made another trip back home via Pearl Harbor to San Diego on 21 December, spendng Christmas there.

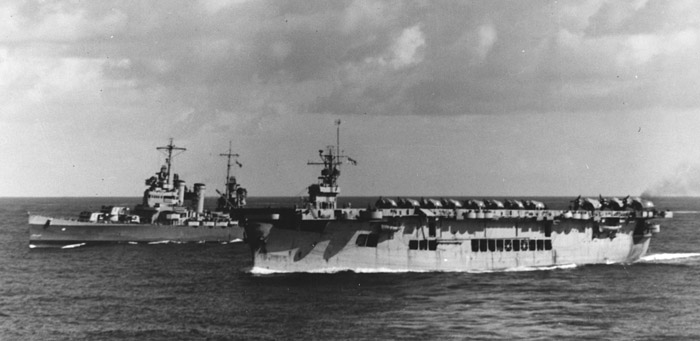

USS Brooklyn and USS Suwannee underway in the Atlantic Ocean, early November 1942

The new year saw her training on the west coast for two weeks, before heading for Lahaina Roads, Hawaii, then en route again on 22 January 1944 for the Marshalls. She was assigned to the Northern Attack Force, her air force striking Roi and Namur, north of Kwajalein in addition to ASW patrols, until 15 February, before moving to Eniwetok. On 2 March she was back in Pearl Harbor.

On the 30th she took part in the assault of the Palau Islands, 5th Fleet. She resupplied at Espiritu Santo and sailed to Purvis Bay, Solomons, Seeadler Harbor, Manus, and New Guinea, supporting the Hollandia landings, notably by sending replacement aircraft to the fleet carriers there. She made two more supply runs to Tulagi and Kwajalein, and then participated in the Marianas Campaign, with the attack on Saipan in mid-June, followed by Guam. On 19 June, she took part in the Battle of the Philippine, with her air attacking and sank I-184 at the start of the battle. Suwanee’s planes was not sent to participâte in the “Turkey Shoot” and stayed in close protection of the invasion force between the CAP and ASW patrol (ASWP).

On 4 August she left for Eniwetok, Seeadler Harbor but was back on 10 September, for the assault of Morotai, being back to Eniwetok and prepare for the next invasion of the Philippines. On 12 October, she proceeded to Manus, with Rear Admiral Thomas L. Sprague’s Escort Carrier Group, reaching the Philippines, her aviation operating in the Visayas until 25 October 1944. Next she spread her air group between striked on Japanese installations ashore, CAP and ASWP.

USS Suwannee at anchor Kwajalein atoll, 7 February 1944

On 24–25 October 1944, she took part in the epic battle of Leyte Gulf. Suwannee was present with the other 15 escort carriers and 22 destroyers when Takeo Kurita’s 1st Striking Force passed through San Bernardino Strait into the Philippine Sea attacking TAFFY 3. Their force was first spotted by USS Kadashan Bay’s planes. USS Suwannee whe it happened was farther south with Rear Admiral Thomas Sprague’s “Taffy 1” and could not do much in the subsequent Battle off Samar. But At 07:40, 25th October “Taffy 1” was attacked by many planes from Davao. This was the first large kamikaze attack of the war.

The first one crashed into USS Santee, USS Suwannee splashed a kamikaze, narrowly missing USS Petrof Bay. Her gunners claimed another, engaged a third circling at 8,000 ft (2,400 m). Hit, the Kamikaze roled over and dove, to end crashing on USS Suwannee’s deck at 08:04, 40 ft (12 m) forward of the after elevator. It blasted with the impact a 10 ft (3.0 m) hole, its bomb exploded between the flight and hangar decks, making a bigger gash, 25 ft (7.6 m) with many casualties in the process. But satefy teams did wonders and in two hours the CVE was operational again.

She repelled indeed two more air attacks before 13:00 before being ordered to join Taffy 3 close enough to launch searches for Kurita’s force, in full retreat after being beaten back in the miraculous, beyond duty staunch USN defense. On 26 October more kamikazes attacked Taffy 1, another Zero crashing into USS Suwanee’s flight deck at 12:40. It crashed onto an Avenger torpedo bomber just recovered, busting into flames, soon spread to nine other parled planes. The fire burned for several hours but damage control was done eventually. For this two days USS Suwanee had 107 dead and 160 wounded. This was her most harrowing test of her career. With other escort carriers put she went into Kossol Roads, Palaus on 28 October, before moving to Manus for upkeep.

Later she headed for west coast for major repairs via Pearl Harbor (19–20 November), entering Puget Sound on 26 November, and be fuly repaired on 31 January 1945. She stopped in Hunter’s Point and Alameda, returned to Pearl Harbor in 16–23 February, then stopped at Tulagi (4–14 March) Ulithi (21–27 March), reaching finally Okinawa on 1 April 1945. She was ordered to provide close air support for invasion troops before be sent hitting kamikaze airfields at Sakishima Gunto. For 77 days, her air group daily sorties for the same missions with Periodical supply runs to Kerama Retto.

On 16 June 1945 she was sent for resplenishing and crew’s rest at San Pedro Bay, Leyte Gulf. Next she was assigned to the Netherlands East Indies, Makassar Strait, to cover landings at Balikpapan in Borneo. From 6 July she was back in Leyte and spent the next month until 3 August, bacj for Okinawa, Buckner Bay and strill being there when the war ended on 15 August. On 7 September she headed for Japan, to cover occupation duty, anchored southwest of Nagasaki. Her air group helped located mines blocking the harbor, and entering on 15 September.

She took onboard New Zealand POWs , ferried to the hospital ship USS Haven, but also assisting due to their own generous medical facilities and doctors. USS Chenango was prepared to leave Nagasaki on 15 September with POWs bound for home, but was weathering a typhoon on 17 September. Anchored after being warned, some cables snapped, but she avoided running onto the cast thanks to the hawser helding. On 21 September, she departed at last Nagasaki, headed for Kobe due to a minefield, then Wakayama. Captain Charles C. McDonald hosted Rear Admiral William Sample (COMCARDIV 22) taking from a Martin PBM Mariner to maintain flight qualifications, but disappearing soon. The wreck was discovered on 19 November 1948.

Suwanee in San Diego Naval Base, 1945

Transferred to the 9th Fleet, then 5th Fleet Suwanee remained at Wakayama in October, weathering another typhoon. Later she was in the port of Kure and back to Wakayama for another “typhoon anchorage”, and proceeded to Tokyo, (18 October) before being order a first run for “Operation Magic Carpet”. She was sent to Saipan on 28 October, loading there 400 troops, then moved to Guam (29 October) to load 35 planes before moving to Pearl Harbor. Next she headed for Long Beach, being dry-docked here before making her second run on 4 December to Okinawa and back to Seattle with up 1500 troops, and Los Angeles, San Francisco. She ended in Bremerton on 28 October, placed in reserve and decommissioned on 8 January 1947.

After 12 years she was re-designated CVHE-27 on 12 June 1955, but was stricken on 1 March 1959, sold to Isbrantsen Steamship Company of New York City (30 November 1959) for conversion to merchant service, but this was canceled after examining her, and by May 1961, she was resold for BU to J.C. Berkwit Company, being sent to Bilbao in Spain, by June 1962. She won 13 battle stars for her WW2 service.

USS Santee (CVE-29)

USS SANTEE was launched oriignally on 4 March 1939 as ESSO SEAKAY, Maritime Commission contract (MC hull 3), built by Sun Shipbuilding and DryDock Co., at Chester, Pa.; and sponsored by Mrs. Charles Kurz. She was acquired by the Navy on 18 October 1940, commissioned on 30 October 1940 as AO-29, with Commander. William G. B. Hatch in command after some service with the Standard Oil of New Jersey, west coast, setting several records for fast oil hauling.

After conversion and commissioning USS SANTEE (AO-29) served in the Atlantic and from 7 December 1941, she was carrying oil for a secret airdrome at Argentia in Newfoundland. By the spring of 1942, her conversion started at the Norfolk Navy Yard and was complete, recommissioned on 24 August 1942, with Commander. William D. Sample at the helm. She was in fact fitted with such haste, that some Norfolk’s workmen were still on board during her shakedown training, while her decks were piled high with stores, still not inside. Her nominal completion was dated 8 September and she reported for duty to Task Force 22. Next was training with her air group, and and the first plane which ever landed on her flight deck was from the 24th.

Mediterranean and South Atlantic service

USS Santee departed Bermuda on 25 October 1942, heading for the coast of Africa. On the 30th, an SBD-3 scout bomber launched from a catapult dropped a 325-pound depth bomb onto the flight deck while doing so. The ordnance rolled off the deck and detonated close to the port bow. The entire ship shook badly, enough for the main range finder and searchlight base to be displaced, and radar antennas to be damaged. It was not consider enough to deter her from service and she went on with Task Group 34.2. On 7 November she was escorted by the destroyers USS RODMAN (DD-456) and EMMONS (DD-457) plus the minelayer USS MONADNOCK (CMc-4) detached to take position off Safi, French Morocco.

As Operation Torch began, USS Santee launched her air group for their first mission, also fuelling ships until Friday on 13 November, before joining TG 34.2 to Bermuda. They departed the 22d for Hampton Roads after two days and after repairs and drydock, she departed again escorted by USS EBERLE (DD-430) on 26 December 1942. On January 1943 she was based in Port of Spain, Trinidad. Next, she operated off the coast of Brazil, disembarking passengers at Recife before be reassigned to Task Unit 23.1.6, her air group deployed to hunt enemy merchant shipping in the south Atlantic.

Until 15 February 1943 her air group was mostly deployed in antisubmarine patrols. Her operating base was in Recife. On 10 March at last, she saw some action: Escorted by the light cruiser USS SAVANNAH (CL-42) and the destroyer USS EBERLE they were sent to investigate a suspicious cargo liner previous identified as the Dutch KARIN, but which turned out to be the German blockade runner KOTA NOPAN. EBERLE’s boarding party cae onboard just when her scuttling charges exploded, killing eight. On 15 March, USS SANTEE was sent to Norfolk for a refit, via Hampton Roads and back in action on 13 June

She was escorted by the old Gleaves class “four-stackers” USS BAINBRIDGE, OVERTON, MacLEISH. She headed for Casablanca on 3 July and departed later with a convoy home-bound. Her submarine patrols spotted none en route, however one Avenger had a technical issue and made a forced landing in Spain its crew interned. USS SANTEE was detached from the convoy on 12 July to operate independently against U-Boat wolfpacks detected south of the Azores. ASW patrols resumed on 25 July, after attacking seven surfaced U-boats, but loosing two SBD Dauntless in the process due to AA fire.

She joined another west-bound convoy to Virginia and on the 26 August after refulling, and escorted by BAINBRIDGE and GREER she was bacl patrolling the Atlantic, based in Bermuda. She escorted another convoy run from Bermuda to

Casablanca and was back to Hampton Roads on 13 October. On the 25th, she departed for Casablanca, refitted at Basin Delpit on 13 November 1943. On the 17th she met USS IOWA (BB-61) with President Roosevelt aboard, tasked to provide air cover for several days, until ordered to the Bay of Biscay, back to antisubmarine patrols intil fall November.

With TG 21.11, escorted by three four-stackers DDs, she went on patrolling the North Atlantic from 1 to 9 December. The group was dissolved at Norfolk Navy Yard on the 10th, and Santee disembarked her air group and headed for New York escorting USS TEXAS (BB-35). Until 28 December P-38 fighter planes were parked onboard at Staten Island and she steamed the following day across the North Atlantic to Glasgow, arriving on 9 January 1944. After disembarking her planes, she departed to join a home-bound convoy on 13 January, arriving to Norfolk and back at sea on 13 February with the destroyer escort USS TATUM (DE-789), crossing the Panama Canal bound for San Diego, reached on the 28th.

Santee’s Pacific Campaign

There, she embarked 300 Navy and Marine Corps personnel plus a new air group of 31 aircraft to be delivered to Pearl Harbor as well as 24 Wildcat fighters and Avengers for her own air group, parked inside her hangar. She unloaded on the 9th and she was reunited with her sister ships SANGAMON , SUWANEE and CHENANGO at Pearl Harbor, prepare to depart with a destroyer escort on 15 March, for the southwest. Carrier Division (CarDiv) 22 joined the fast carriers of the 5th Fleet on 27 March 1944, reaching the the Palaus. From there, Santee’s career is the same as her sister ships.

She operated in the closing phase of the New Guinea campaign, in the Solomons in April, her air group assiting in destroying 100 enemy aircraft. On 12 May-1 June, she carried 66 Corsairs and 15 Hellcats and personnel for the Marine Air Group 21. She took part in the assault cover on the Kwajalein Atoll, Marshalls and in August was in Guam. Air Group 21 (81) aircraft were landed on the reconquered Guam. She operated with TF77 near Mapia Island, and attacked Morotai in the Moluccas, having Manus as operating base.

On 12 October, she attacked several targets in Philippine waters and on 25 October, as the battle of Leyte developed, she received her first war damage: At 0740, a lone Kamikaze dive on SANTEE with a 63 kg bomb, crashing through her flight deck and splashing on her hangar deck. At 07:56, she was struck by an airbone torpedo flooding several compartments, and she took a 6° list, but repairs were complete at 09:35. Until 27 October, hr air group claimed 31 enemy planes. They also sank an IJN 5,000 ton ammunition ship, and rampaged any objectives during 377 sorties. On 31 October, she received more repairs at Seeadler Harbor, Manus Is.

On 9 November, she sailed back to Pearl Harbor for more repairs, embarking 98 marines back to the states, reaching Los Angeles on 5 December. She had a general overhaul, making post repair trials at San Diego and being back to Hawaii on on 8 February. On 7 March 1945, she headed for the Western Carolines, and reached Leyte Gulf. On 27 March she covered the southern transport groups Dog and Easy towards Okinawa Gunto in the frame of the Okinawa campaign.

On 1 April 1945, she provided direct support until 8 April, then operated on Sakishima Gunto, her air group also rampaging the East China Sea, alternating with Okinawa itself and on 16 June, started to attack Kyushu in Japan proper. On 5th-14th June she covered minesweeping operations. On 7 July, she had a plane missing its mark as its tail hook broke when landing clearing all barriers and crashing among parked planes, with four fighters and two torpedo bombers being destroyed by flames and jettisoned, six torpedo bombers being total constructive loses, and one pilot killed.

On 15 July she was detached to Guam, Apra Harbor, and after deck repairs and upkeep she was sent on 5 August for Saipan. She was underway for the Philippines on 13 August, receiving two days later news of the cessation of hostilities and deopped anchor at San Pedro Bay in Leyte. On 4 September, while en route to Korea in order to cover occupation forces she was diverted to northern Formosa to evacuate ex-POWs, 155 officers and men of the British and Indian Armies captured by in Malaya in 1942. She picked up additional men from destroyer escorts FINCH (DE-328) and BRISTER (322 total) including men from Bataan and Corregidor, from the Dutch Army and Merchant Marine captured in Java. They were disembarked at Manila Bay, after which she headed for Okinawa, Buckner Bay, then Wakanoura Wan, Honshu, and until 26 September, she steamed along the coast for on-demand air coverage, notably in destination to Wakayama.

She departed Wakanoura Wan on 3 October 1945 leaving her air group, searching for a missing PBM aircraft carrying Rear Admiral William D. Sample, her former first commanding officer. On 20 October, she was back to Okinawa, and headed for Pearl Harbor, disembarking 375 passengers and taking part in Operation “Magic Carpet” with 18 marines for the west coast. She was in San Diego on 11 November to the 26th, then headed for Guam for another run. On 27 February 1946, she departed San Diego for Boston Harbor, being placed in reserve on 21 October 1946. On 12 June 1955 she was reclassified as an escort helicopter aircraft carrier (CVHE-29), but never modified not used in that role and struck from the Navy list on 1 March 1959. On 5 December 1959, she was sold for BU to Master Metals Co. In all, she received nine battle stars for her wartime service.

Read More/Src

Books

Smith, Peter C (2014). Kamikaze To Die For The Emperor. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books

“All Hands Naval Bulletin – Dec 1945 | PDF | Pacific War | United States Navy”.

Friedman, Norman (1983). U.S. Aircraft Carriers. Naval Institute Press.

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

Paul H. Silverstone: US Warships of World War II. Ian Allan, London 1965, reprint 1982

Terzibaschitsch, Stefan (1979). Flugzeugtraeger der U.S. Navy. Munich: Bernard & Graefe

John Gardiner Conway’s all the World’s fighting ships 1921-47.

Smith, Peter C (2014). Kamikaze To Die for the Emperor. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books

Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea (1983). Europe, Torch to Pointblank, August 1942 to December 1943.

Howe, George F. (1993). The Mediterranean Theater of Operations — Northwest Africa: Seizing The Initiative In The West.

Links

About their extensive medical facilities (pdf)

Logs on hazegray.org

Oral Histories – Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23-25 October 1945

usssuwannee.org

Chenango II on history.navy.mil

Chenango on navsource.org

Santee on navsource.org

Videos

footage of the gun crew of uss sangamon

The class on navyreviewer

Model Kits

1:350 iron shipwrights

1:350 CVE-26 Trumpeter

1:700 ACV-26 Aki Products

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign