Project 705 Lira (NATO “ALFA”) nuclear attack submarines

7 submarines: K-64, K-123, K-316, K-432, K-373, K-493, K-463

7 submarines: K-64, K-123, K-316, K-432, K-373, K-493, K-463

Soviet Cold War Subs

Pr.613 Whiskey | Pr.611 Zulu | Pr.615 Quebec | Pr.633 Romeo | Pr.651 Juliet | Pr.641 Foxtrot | Pr.641 buki Tango | Pr.877 KiloPr.627 kit November | Pr.659 Echo I | Pr.675 Echo II | Pr.671 Victor I | Pr.671RT Victor II | Pr.671RTMK Victor III | Pr.670/670M skat Charlie | Pr.705 lira Alfa | Pr.949 antey Oscar | Pr.945 Sierra | Pr.971 bars Akula | Pr.885 graney Yasen | Pr. 545 Laika

Pr.629 Golf | Pr.658 Hotel | Pr.667A Yankee | Pr.667B Murena Delta I | Pr.667D Delta II | Pr.667BDR Kalmar Delta III | Pr.667 BDMR delfin Delta IV | Pr. 941 akula Typhoon | Pr.995 borei Dolgorukiy | Pr.09851 Khabarovsk

The world’s fastest SSN was already in 1960 a Soviet submarine, the first with two nuclear reactors, with a tested underwater speed of 31 knots: Project 627 “Kit” (NATO “November”). In the mid-1960s it was clear that the US were gearing towards faster ASW escorts, and at the same time, there were alternative nuclear reaction types that could on paper provide an ever greater power. This was a liquid metal-cooled reactor. And this was coupled for the first time with an all-titanium hull, lighter yet stronger. Both combined gave the Alfa class the title of fastest and deepest serial SSNs, as the sole prototype K-222 (NATO Papa-class) managed to beat this.

The world’s first fastest SSNs

The “Alfa” class attack submarines (project 705 Lira) constitute a completely new concept of underwater “interceptor” intended to gain a significant advantage over NATO forces in matter speed and depth, an idea emerging back in 1957 to both catch up 30 knots CBGs and escape their escort. The November class were initially supposed to answer this requirement, but experienced a series of tragedies linked to the way their reactors were built and adapted and rushed into service with many control quality issues. The Alfa were supposed to mark a new milestone in technical advance after a study by Professor A. B. Petrov of the Malakhit design office. The latter proposed a revolutionary solution combining a lighter titanium inner (pressure) hull coupled with a thinner steel houter hull, both in a reduced size, coupled with a brand new fully automated experimental reactor to simplify maintenance, and very small crew.

The titanium hull was already a first challenge, being very expensive and complex to work with but much more resilient and light than steel. In addition, this reactor, effectively far ahead (with however the technology still simple and rudimentary at the time) on the standards of its time, used liquid lead for its cooling, and capable, while being very compact, of delivering 155 MW. This, combined with the small size of the Alfa should give them the required speed. There were seven units built, whose Soviet project name was Lira.

The first was launched in 1967 but entered service only in 1972. But she had a short career: The cooling system of her reactor left something to be desired, as liquid lead froze. She was BU no long after, in 1974. Modified, others were launched in 1974, 1976, 1978, 1980 and 1981. One of these, built in Severodvinsk, and launched in 1977, was apparently a variant, called Nato “Mike”. She suffered serious damage following a reactor failure followed by a nine-year overhaul, after which she received a new conventional pressurized water reactor.

The “Alfa” class, despite their recurring engine issues, indeed shone by their performance: Their top speed during testing was close to 46 knots (73 ph), an absolute record in the category, still unmatched. But in service, it rarely exceeded 42 knots. In addition, their maximum operational depth was 800 meters, while it was expected to be more than 1000 meters. At least two units received a more standard reactor than their initial system of two Lead-Bismuth reactors, cut with two turboelectric groups. Three had all-steel, not Titanium, hulls. The first of these submarines, K377, was withdrawn from service with the Northern Fleet (where they were all based) in 1974, the K463 in 1986 and scrapped in 1988, the others were withdrawn from service between 1993 and 1997.

Development and Origins

Project 705 was first proposed in 1957, by M. G. Rusanov. Initial design work however only started in May 1960 in Leningrad, so this was a long endeavour. The design task was assigned to SKB-143, a predecessor of the Malakhit Design Bureau, the later Soviet sub specialist with Rubin and Lazurit. This was a highly innovative project as for its requirements with a speed to chase or escape any existing surfe ships in NATO inventory, meanding 33+ knots at the least. It was also to avoid ASW weapons by speed and agility (meaning out-running/out manoeuvering a torpedo) and stay stealthy for underwater operations, notably against airborne MAD arrays and active sonars. Agility also required a minimal displacement and minimal crew to got with it. This was far more ambitious than the 1st gen SSN of the November class, almost a reinvention of the concept.

Project-673 (1962)

The concept of a very small and fast interceptor submarine was planned as the finally unbuilt Project-673 design. It only existed on paper, was to be built from titanium alloys with a nuclear reactor using lead-bismuth liquid-metal for cooling, high automation and very small crew of 16, all officers. Blueprints shows a very pure teadpole hull without sail at all, a length of 66.26 m for 9.20 m in beam and a draught of 7.60, displacing 1500/2200 tons with a top speed of 25 kt cuising, 40 kt maximum plus creeping speed of 5 kt.

The first key innovation needed to reach these ambitious goals was the bold choice of a special titanium alloy hull. This was required to create a small and low drag 1,500 ton submarine, built with six compartment and a very powerful machinery (likely nuclear) to reach the very high speeds, precised to be in excess of 40 knots (46 mph; 74 km/h) as well as deeper diving. Project 673 in fact was capable of 600 m in operation ( or 1970 ft, meaning it had to surface to 200 m to fire its torpedoes) but also 800 m max (2620 ft), and an estimated 1300 m (4300 ft) crush depht.

The main hope there was indeed to be able to out-run a torpedo, deep enough for the latter to be crushed. Most torpedoes at the time were more lightly built than submarines and rarely went below 200m. By its agility and limitations to torpedoes only (a new generation was also in the works) she was seen as an high-end “interceptor”. She was not intended to long crossing but staying on harbor or on patrol route to race out an approaching fleet.

The second great innovation then came out to deliver the formidable output necessary for this model to punch her way through deep, cold and compressed salty waters: A high-power liquid-metal cooled nuclear reactor. The idea was already tested on the civilioan field by researchers. The most impotant issue was that the metal needed to be kept liquid in port through external heating. Another aspect to reduce the crew and occupy the compartments by the powerplant and torpedoes, was extensive automation to greatly reduce manpower. The initial goal was unheard of for a submarine, as the team looked after a crew of no more than 16 men.

So three major mountains of issues were at hand straight from the bat and nothing had been done before, neither isolately, nor together.

Practical problems surged and by 1963 the design team just could not solve all the issues and progress stalled.

Revision to Project-705 (1963)

Specifications were revised and a new team arrived to take over with a less ambitious project. Main dimensions were radically increased, from 1,500 to 2,300t, leaving more space for extra crew (now 32) and decreasing automation, using more existing systems. The final crew will ultimately reach 31 in fact. This was the smallest crew since the 1950 Quebec class SSK (460 tonnes)…

The revision gave more internal breething space for the nuclear reactor, and the top speed was now degraded to 40 knots. To put things into perspective the same Quebec class could reach 16 knots.

The best NATO subs were limited to 27-28 knots at best (USS Albacore -33 knots- remained a prototype).

But working out a titanium hull was never done before and the metal was reputed very hard to work with and weld.

Still, before carbon composite, this was the next best thing to built a submarine. The only other “craft” built that way would be not other than Skunk Works’s SR-71 Blackbird, CIA’s preying eyes on USSR at that time from 1966.

The SSGN version: Project 661 Anchar (NATO PAPA)

The Soviet Navy in fact became so enamored by the concept it was decided to test the same ideas in another prototype. This was to be a submarine of roughly similar design, albeit much larger in order to have room to test these innovations, but also to explore an SSGN design and replace the older SSGs classes at some point (The Ocsar class were built instead).

This was Project 661, the single K-162 (from 1978 K-222). This cruise missile submarine was referred to by NATO as the “Papa class” and it was unclear if she was alone for quite a time. She was built at the SEVMASH shipyard, Severodvinsk, completed in 1972, so a few months after K-64, the lead boat of the Alfa class.

Her construction started about the same time with both teams sharing informations about the process. By late 1961 the first titanium plates arrived and she was officially only laid down on 28 December 1963. Indeed delays were caused by numerous design flaws and difficulties in manufacture. Kommunar Metallurgical Plant which provided these plates were found contaminated by hydrogen and cracking easily, no ideal to endure pressure… In fact 20% of the plates were rejected outright on summary examination. So she was only launched eventually on 21 December 1968. Adnd even then, it was realized her ballasts were not watertight.

Extensively tested, she was taken out of service following a reactor accident in 1980. She had a top speed of 41.2 knots (47.4 mph; 76.3 km/h) and a test depth of 400 m (1,300 ft). This combined with other reports created some alarm in the U.S. Navy and prompted the rapid development of the ADCAP torpedo program and the Sea Lance missile programs projects (the latter was cancelled when more definitive information about the Soviet project was known). The creation of the high-speed Spearfish torpedo by the Royal Navy was also a response to the threat posed by the reported capabilities of submarines of the Project 705. It was also realized than on-titanium components were not properly isolated from the hull, causing an hydrolitic corrosion. K-222 was ultimately commissioned later than K-64, but her commission was delayed by scores of newly found issues and fixes.

In the end, this missile counterpart of “Alfa” could indeed dive to 400 meters and reach 38 knots underwater, with studies starting even before the Alfa by 1959, but the even larger titanium double hull and missile/torpedo combination were combined (also) with automation on a tight space, and a new Sonar system, as well as a new navigation system, new batteries and new air conditioning and hydraulic systems working at very high pressure. She was allso the first with two thrusters to reduce acoustic signature (the first soviet attempt to a “pump jet”). She had ten long-range missiles in inclined ramps, forward flanks, like the Echo class.

In terms of pure speed, on trials TASS announced she was certified by the Guinness World Records for her unheard of 44.7 knots in forced gear, which still holds today at least officially. We cannot count supercavitation torpedoes like the Shkval like a submarine… Her max “normal” speed 42 knots was reduced to 35 since strong vibrations negated acoustic discretion. In fact she even had a kiosk door released on trials, three shutters and the buoy ejector hatches being deformed, and fly open. Noise, complexity, cost, construction difficulty shelved the project as unrealistic. K-222 from 1991 was decommissioned and remained in Severodvinsk in 1995 for recycling or disposal. She only confirmed the path taken by the simpler Alfa class to be the better.

Production of the design

Once the final design was approved, construction of the lead boat was authorized to Admiralty (Sudomekh) in Leningrad as Project 705 in 1964. Construction was also doubled at Sevmashpredpriyatiye (SEVMASH) at the Northern Machine-building Enterprise in Severodvinsk. K-64 was laid down in Leningrad and three follwoed while Severodvinsk was ordered three Project 705K which had a revised reactor plant. However, like for the Papa class, forging the titanium hull prpoved extremely complicated.

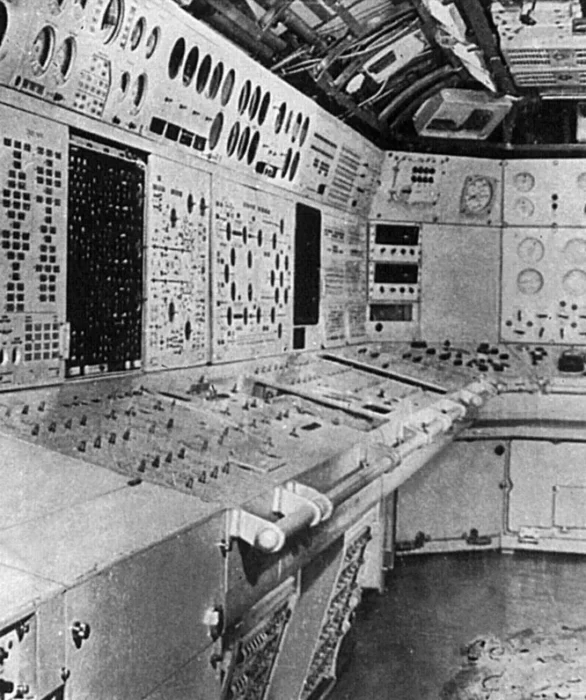

Alfa class CiC

The lead boat was laid down much later than the previous Papa class, benefiting from the experience with titanium forging, and she was laid down on on June, 2, 1968 and launched in April 22, 1969. To compare, K-222 was initially laid down on 28 December 1963, and launched still on 21 December 1968…

The completion however dragged on after examinations and fixes by December 31, 1971. This was four years, far better than the rival project Anchar. Other subs of the class had more time in construction, 5-6 years on average, which given the complexity of the whole design was understandable.

K64 was commissioned in 1971 and yet she was still considered an experimental platform to test innovations and her sisters were believed to lead later to a new generation of SSNs. In 1981, after the seventh built it was decided to terminate the program, and all were sent to serve in the Northern Fleet. Gven the odds, it mairaculous these formed an class operational class in the first place.

Design of the class

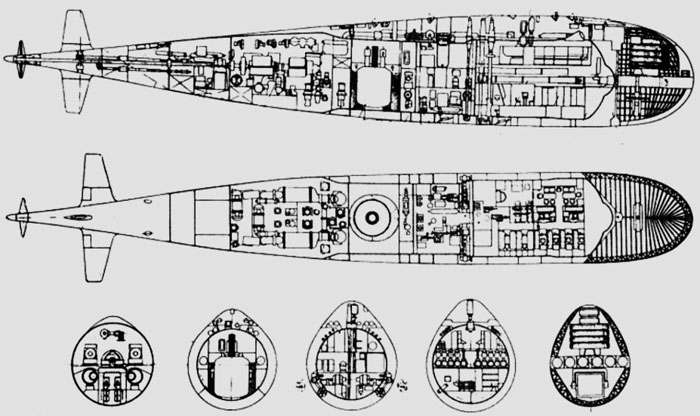

Hull and general design

Like most Soviet nuclear submarines, Project 705 was given a double hull, the internal one being the pressure hull made entirely in titanium while the outer one protecting it and providing an optimal hydrodynamic shape. Her hull was more gracefully shaped and its sail highly streamlined, for higher submerged speed and maneuverability. Hydrodynamic efficience was pushed hard and in a way, these submarines were the Soviet equivalent to the USS Albacore.

Apart from prototypes, all six Project 705 and 705K submarines had pressure hulls in titanium alloy, something completely revolutionary in submarine design at the time. The first issue was the cost of titanium, as well as the technologies and equipment needed to work that material. Since Soviet engineering communiy had little to no experience with Titanium, this was along and painful learning curve. It shoukd be sail that other military projects were concerned, like the fabled Mig-25 “Foxbat”, the world’s first trisonic interceptor, designed to catch and shoot down the projected XB-70 Valkyrie bomber.

1 — Yenisei HAC main antenna

2 — 533 mm TTs

3 — VVD system cylinders

4 — first (torpedo) compartment

5 — spare torpedoes with automated loading complex

6 — Sargan FCS equipment room

7 — Air Bottles

8 — bubble-less torpedo firing tank

9 — bow trim tank

10 — central gas block

11 — second radio-electronic and auxiliary equipment compartment;

12 — VVD system compressor partition

13 — Yenisei HAC antennas

14 — Main periscope mast, Aiva communication antenna (satcom Molniya);

15 — Pop-up external camera and TV-1 system periscope

16 — Persicoping antennas, Chibis radar

17 — Antenna mast fir the Topol (Molniya satcom)

19 — Veslo-P radio direction finder mast

20 — 3rd main command post compartment

21 — Main command post

22 — Living, medical and sanitary rooms

23 — Galley and provision chambers

24 — Fourth (reactor) compartment

25 — Reactor with steam generators, circulation pumps/biological protection tanks

26 — Emergency buoy

27 — Turbine compartment

28 — Block steam turbine plant

29 — Desalination plants and steering gears compartment;

30 — Stern hatch

31 — Shaft line

32 — Oil tanks

33 — Sesalination plant

34 — Stern trim tank

35 — Stern rudder drives

36 — Stern vertical stabilizers.

It was to be Mach 3.2+ and that caused new heat tolerance issues, so designers chose titanium rather than steel at first but found it also expensive and difficult to work with. Cracks appeared in welded titanium structures and simply could not be solved. Heavier nickel steel was used, with heat-resistant seals and final mix of 80% nickel-steel alloy, 11% aluminium, and 9% titanium. This happened in 1963, the first prototype fleet in 1964.

It was believed that an adaptation of the material for a submarine would be better, as pressure would hold the structure altogether, unlike on a powerful jet, subjected to heating and expansion. However difficulties in engineering became apparent. The prototype K69 was in fact short-lived and quickly decommissioned after cracks developed in her hull.

However Soviet metallurgy and welding technology were much improved over the next years, and after delays, it was possible to built hulls for the next boats with more confidence. There were less issues with subsequent vessels. American intelligence services also discovered the use of titanium alloys in their construction as they managed to get their hands on metal shavings simply falling from a truck leaving the severely guarded St. Petersburg ship yard.

The pressure hull was not much different internally than previous projects and separated into six watertight compartments, enclosed by very thick bulkheads. Only the third, forward compartment was manned in fact. All others were only accessible for maintenance which was highly automated and remotelly operated. This third compartment had reinforced spherical bulkheads to withstand even more pressure at test depth than the rest, being the “life capsule” inside the submarine.

It offered indeed additional protection to the crew. However deprived of energy and immerged, there were little in terms of underwater safety to enhance survivability so she was also equipped with an ejectable rescue capsule, which could at least save a few men to tell the tale. The “life capsule” had an auxiliary generator or light and air filtration, but of limited capacity and time.

The original test depth requirement was 500 metres of 1,600 ft, which was in thoery capable of escaping ASW depht charge max settings and torpedoes of NATO for 1965. But after the preliminary design was completed, SKB-143 relaxed that requirement down to 400 metres (1,300 ft). This indeed was make the pressure a bit thinner, simpler to built, while increasing the space and weight available for the reactor, as well as the top of the line sonar system envisioned, and fitting transverse bulkheads. The 1,000 metres (3,300 ft)and deeper dive was a myth found in Western intelligence estimates in that stage of the Cold War, ensuring the scare would results in new and more interesting contracts for ASW.

As said above, the Alfa class were highy automated, resulting in a smaller crew. All the systems that could be remotelly operated from a central were. All operations requiring human decision were performed from the control room, all the rest were based on simple detection/action sensors and mechanisms. The problem was that level of automation was common in Soviet aviation, not on ships. The latter indeed involved far more than a pilot but whole specialist teams performing more complex tasks.

Crew intervention was required underway for course changes and combat. No maintenance was performed at sea and apart monitoring instruments and acting on some parameters, ther crew could be reduced to a few men by department. The typical combat shift of these submarines went down to eight officers stationed in the control room and a few more sub-officer ratings (6) plus the non-officer cook. However later it was considered more practical to have additional crew aboard, notably to train a new generation of submariners. This was increased to 27 officers, four warrant officers but forced to find extra accomodation space where none was planned. The sub fet thus, “cramped” to say the least. Still, as crew’s cost was not an issue, the main incentive behind this high automation was to reduce reaction time, and a more compact size of the submarine. This was believed to speed up any action, avoiding the chain of command.

However most of the electronics components linked to this automation were of Soviet origin and thus, suffered from the same lack of control quality. Many of these automated system were complex and newly developed, so failures were expected. The extra crew were all specialist which stationed to monitor performance of these systems. Theere were indeed reliability issues with electronics, and often accidents would have been prevented with just a more mature and better developed monitoring systems. Again, the Alfa class concentrated many innovations into the same package, at was far more frantic pace than ion the West, with engineers putting altogether these while higher-ups were breathing heavily over their necks.

Powerplant

A risky bet: The choice of lead-bismuth cooling

The power plant was completely new, and was the first to used a lead-bismuth cooling system, for beryllium-moderated reactor. This was a liquid metal cooled reactor, and this alternative branch compared to pressurize water or soldium-cooled ones had many advantages:

-The higher coolant temperature allowed a much greater energy efficiency, 1.5 times that of a PWR.

-The higher efficiency meant it could stay operational much lonnger, before the need of a core change.

-The liquid lead-bismuth system was considered safer, as it just quickly solidified in case of a leak.

-This made also for lighter and smaller reactors, a primary factor for Project 705 submarines.

In the 1960s however existing technology was barely sufficient to produce reliable liquid metal reactors. In fact even today they are still considered so challenging, that there are few ongoing projects. A bit of history history here: Liquid metal cooled nuclear reactor, or LMR are the best due to high thermal conductivity and they can drive power conversion cycles with high thermodynamic efficiency. They need to be moved by electromagnetic pumps which are less noisy than conventiona ones as well, but need their own separate energy source. The major issue remains maintenance: For inspection and repair the reactor is immersed in opaque molten metal. There is in addition a fire hazard risk for alkali metals with also corrosion and possible production of radioactive activation products.

They saw a limited civilian use still as fast neutron reactors (LMFRs).

Mercury, Sodium, NaK, Lead and Tin were all tested, but the Russian choice was on Lead-bismuth eutectic. However it allows operation at lower temperatures while preventing freezing of the metal coolant with an eutectic point of 123.5 °C/255.3 °F). However it had an highly corrosive character and forms by neutron activation of 209 Bi (and subsequent beta decay) of 210 Po (T1⁄2 = 138.38 day). This is volatile alpha-emitter, highly radiotoxic. In fact this is the highest known radiotoxicity, above that of plutonium. Still, authorities considered its advantages compelling. Two power plants were developed independently: The BM-40A by OKB Gidropress in Leningrad, as well as OK-550 by the OKBM design bureau in Nizhniy Novgorod. The two used the same eutectic lead-bismuth solution for the primary cooling stage. They were both able to produce 155 MW.

Amazing performances, massive tradeoffs

Once combined with such a well streamlined (in fact they had the most refined shape than any other Soviet submarine to date) which was lighter than usual, this made for submarines capable of amazing speeds indeed. For such a 3000t mass being able to punch through deep, icy cold water at 43–45 kn (49–52 mph; 80–83 km/h) as tested, was nothing short of amazing for the time.

However speeds were soon toned down a bit for the class at 41–42 kn (47–48 mph; 76–78 km/h) and they were only considered “sustainable dfor short, emergency situations”. Another impressive fact about these reactors is that their acceleration to top speed was done in just a minute, reversing 180 degrees at full speed in 40 seconds. This was unreal agility for a submarine.

That maneuverability exceeded all standards of the time and reach the second desired requirement, as they could not only outmanoeuver any other submarine but also leave behind or dodge any torpedo launched at them. During training this was confirmed as other subs klaunched tiorpedoes (with duds obviously) at them adn the Alfa class proved able each time to successfully evade these.

It’s only after enough intel was gained in the west about these submarines that a new generation of torpedoes entered service. These faster torpedoes were the American ADCAP or British Spearfish. However the Alfa class paid these characteristics by a very high noise level at burst speed, with a more silent, tactical speed similar to Sturgeon-class submarines according to US intel in the 1980s.

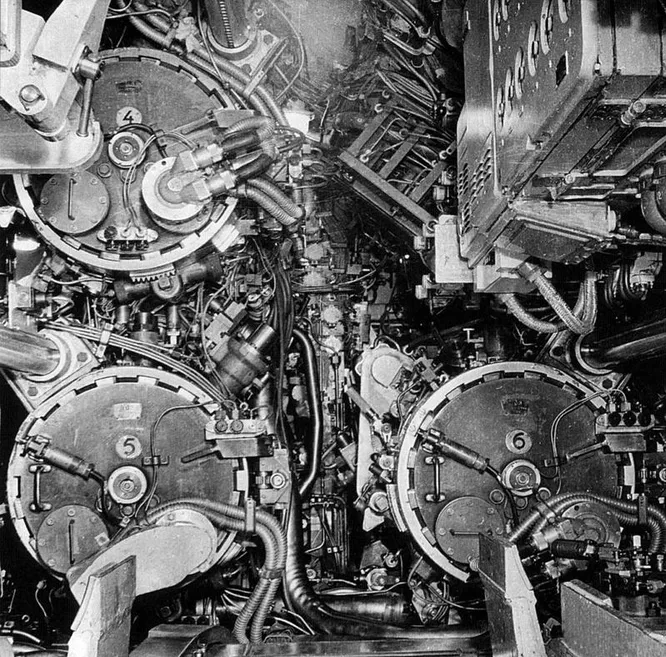

The powerplant

The reactor powered a 40,000 shp steam turbine, and in addition to their single main 5-bladed propeller it was chosen to add two 100 kW electric thrusters on the tips of their stern stabilizers for “creeping” approaches and emergency propulsion as backup. Electrical power in that case, also powering all onboard systems and the ballasts if the main engieering plant failed, was provided by two 1,500 kW turbogenerators, and there was an extra backup 500 kW diesel generator in the crew compartment, plus a bank of 112 zinc-silver batteries.

Reliability remained an issue early in their career. The OK-550 plant was used for Project 705, but later the Project 705K boats adopted the BM-40A plant due to constant reliability problems with the OK-550. The BM-40A however was much more demanding in maintenance than older pressurized water reactors as the lead/bismuth eutectic solution solidified at 125 °C (257 °F). It ever it happened, it would have been impossible to restart the reactor. If the reactor needed to be shut down, the liquid coolant required constant heating with an external source and superheated steam.

The need for pier-side facilities

This imposed particular facilities, which only existed at the norther fleet base, new piers where the submarines were moored received a special facility to deliver this superheated steam when in port. A smaller ship was also stationed at the pier to provide extra steam from her steam plant if needed.

Hoever coastal facilities in USSR at the time certainly received less care than the submarine themselves and regularly failed to deliver the heat to keep the collant unfrozen in the reactors.

As a result, the captains decided to keep their reactors active even when the boats were anchored and free from crew. There was still a nucleus crew and engineers present at all time, rotating. Facilities completely broke down early in the 1980s, so all Afla class had their reactors constantly running and quickly worn out. The BM-40A could do it for many years without stopping but never had been designed for such treatment and any serious maintenance proved impossible. Failures accumulated in the late 1980s, notably coolant leaks. One reactor froze while at sea. This of couirse shortened their career. Four were decommissioned earlier than expected.

Armament

Torpedo Compartment

533 mm SET65 and 400 mm SET40 torpedoes side by side, Kaliningrad.

Only torpedoes, but two calibers, and most importantly, the whole loading operation was entirely automated. There were just two operators to watch over the operations from displays in the control center. One looked out the selection, loading, setting up and readiness, then pushed the launch button, the other monitored the torpedo(es) course and target assignments.

All were armed with just four 21-inches (533 mm) torpedo tubes in the bow (12 total in reserve) and four light torpedo tubes, 16 inches (400 mm), two at the bow and two a the stern. The 533 mm bow torpedo tubes were the main atack tubes, firing the SET-65 and SET 53-61 torpedoes at first, both capable of being fired under 100 m. The four stern torpedo had models capable of 240 m deep operation, still far less than the submarine’s own diving capabilities. The “Ladoga” hull sonar took charge of the location of target, with a data transmitter for the 533 mm models, while the 400 mm models were guided by the SJSC “Kerch” data system.

Later, the SAET-60M was also adopted.

SAET-60M

For discreet sub-killing in the on-board panoply was also the SAET-60 (1961) and SAET-60M (1969) passive acoustical homing. Weight: 4,409 lbs. (2,000 kg) for 307 in (7.800 m) in lenght, 533 mm, carrying a powerful 661 lbs. (300 kg) warhead. Powered by a silver-zinc battery, the difference between the two models are their settings. The first was capable of 42 knots up to 14,200 yards (13,000 m), the second is slower at 40 knots but for 16,400 yards (15,000 m).

SET-65 “Yenot-2”

Introduced in 1965, these were Guided Electrical Torpedoes. They counted on active acoustic guidance, its own range was about 880 yards (800 m)

Weight: 3,836 lbs. (1,740 kg), 307 in (7.800 m) long, with an explosive charge of 452 lbs. (205 kg). It was Powered by a silver-zinc battery for a Range of 17,500 yards (16,000 m) at 40 knots, single setting. Yes, it was slower again than the Alfa’s top speed.

SET 53-61 “Alligator”

The first of these Acoustic wake models, derived from a long lineage going back to captured 1945 German G7 variants was introduced in 1961 and another version was already worked on. Its service life thus was short with the Alfa class. Weight and lenght is unknown, but probably larger than the previous SET-53/53M (3,263 lbs./1,480 kg, lenght 307 in/7.800 m) as they had a larger payload of 672 lbs. (305 kg). They were very fast, powered by a Kerosene-Hydrogen Peroxide Turbine

for 16,400 yards (15,000 m) at 55 knots with a second setting for longer range at 24,000 yards (22,000 m) at 35 knots.

The next SET 53-61M (1969) replace it, with an improved homing system.

SET-40 (MGT-2)/SET-40U

This active/passive acoustic homing torpedo exclusively for defense against ASW ships. Its homing range was between 660 and 880 yards or between 600 and 800 m. The first model was introduced in 1962 and followed the MGT-1, first Soviet Passive acoustic homing torpedo, in service the previous year. It was however only capable of 28 knots at 6600 yards and thus could be out-runned by Skipjack class SSNs but not most USN frigates of the time.

The SET-40 or MGT-2 improved on characteristics. It’s not clear how the SET-40U (1968) improved, likely extended the range of detection.

Weight: 1,212 lbs. (550 kg), lenght 177 in (4.500 m) x 15.75″ (400 mm)

176 lbs. (80 kg) warhead, Silver-zinc battery for 8,700 yards (8,000 m) at 29 knots.

VA-111 Shkval

In replacement for its torpedoes an Afla class can also carry twenty of these supercavitation torpedoes. They were introduced later in their service. Entered service in 1977, deployed in the 1980s, the “squall” was the Soviet “secret weapon” of the deep. This was eessentially a rocket-propelled torpedo, last ditch weapon generating a gas-cavity for 200 kts speed but no homing at all. Due to this, in 1998 appeared a new version slowing to search for a target. This model was 5,952 lbs. (2,700 kg) for an overall lenght of 323 in (8.200 m) and carrying an explosive warhead of 1,543 lbs. (700 kg) and a solid-fuel Rocket for a range of 12,000 to 16,400 yards (11,000 – 15,000 m) at 200 knots, initially of 7,700 yards (7,000 m). The sheer speed (370 kph or 230 mph) creates a superheated bubble around making it very noisy and relatively easy to dodge, at least for the first model. The later, 1998 one searched, and then went straight to the target without correction for its last leg. It still could be dodgedat the last minute as it was a straight course run.

In replacement for its torpedoes an Afla class can also carry twenty of these supercavitation torpedoes. They were introduced later in their service. Entered service in 1977, deployed in the 1980s, the “squall” was the Soviet “secret weapon” of the deep. This was eessentially a rocket-propelled torpedo, last ditch weapon generating a gas-cavity for 200 kts speed but no homing at all. Due to this, in 1998 appeared a new version slowing to search for a target. This model was 5,952 lbs. (2,700 kg) for an overall lenght of 323 in (8.200 m) and carrying an explosive warhead of 1,543 lbs. (700 kg) and a solid-fuel Rocket for a range of 12,000 to 16,400 yards (11,000 – 15,000 m) at 200 knots, initially of 7,700 yards (7,000 m). The sheer speed (370 kph or 230 mph) creates a superheated bubble around making it very noisy and relatively easy to dodge, at least for the first model. The later, 1998 one searched, and then went straight to the target without correction for its last leg. It still could be dodgedat the last minute as it was a straight course run.

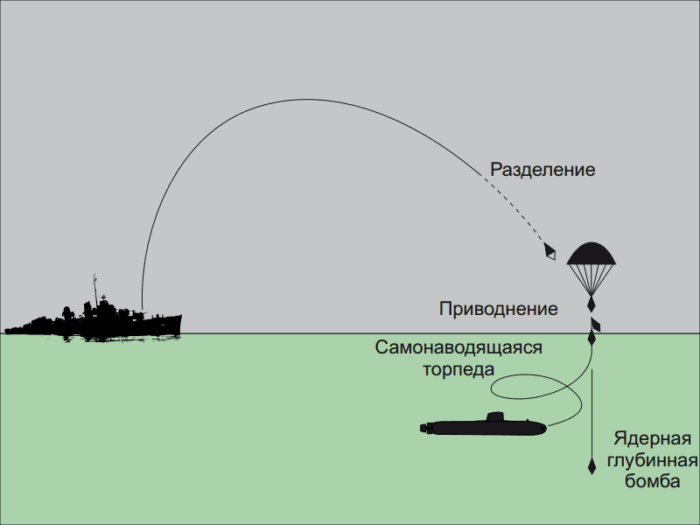

RPK-2 Vyuga

These 81R anti-submarine guided missiles were introduced in 1969. Studies started in 1963. Essentially a Soviet version of SUBROC. It is a missile launched by torpedo, which had a double advantage of speed, range and to carry an optional nuclear wrhead. The ultimate weapon against a surfaced ASW ship at a safe distance.

The RPK-2 uses a 82R torpedo or 90R nuclear depth charge. Shared also by the Akula, Oscar, Typhoon, Delta, Kilo, and Borei classes. The missile had a short burn, using solid fuel rocket for 35–45 km (22–28 mi) at Mach 0.9 with inertial guidance but carries a 2445 kg warhead, eitehr a 400 mm Type 40 torpedo (see above) or a 5 kt thermonuclear warhead. Its use is not certain for the Alfa class but appears in a few sources.

MG-84 Korund-705

Not a weapon per se, but a 400 mm torpedo decoy. This self-propelled multipurpose hydroacoustic countermeasure device was developed by the Central Research Institute “Gidropribor” and accepted into service in 1974. Produced by Dvigatel in Leningrad is similar to a standard 400 mm electric torpedo.

However its role is EW warfare to incoming torpedoes and decoy role. It could emit powerful hydroacoustic interference or alternatively simulate the running noise and echo signals of the carrier submarine with a precise setup. It could even maneuver like it. More

PMR-1/PMR-2 mines

Optionally the Alfa class were planned to carry out “minelaying” missions, laying up to 36 of these 533 mm mines. It’s not ever certain this feature was ever used. Nevertheless, the PMR-1 had a two-channel system to detect and classify targets. It was just laid down in the deep, waiting, and launched from an airtight container if a target was identified, delivering a 400 mm ASW electric torpedo from down to 600 meters. It was accepted into service in 1972.

Alfa class Sensors

MRK-55 Chibis radar:

Navigation radar for surface operation, on mastn close to the “Veslo-P” mast.

MRP-23 Bulava-705:

Reconnaissance radar, carried on a mast.

Khrom-KMA IFF:

Identification Friend or Foe system, antenna errected when surfaced, at the rear of the sail.

Veslo-P radar:

Aerial first warning radar, shared by Project 670 Skat.

MVU-111 Akkord CiC:

This center, at the top of the three decks, below the sail, received and processed hydroacoustic, television, radar, and navigation data from other systems. It enable to determine location, speed, and predicted trajectory not only of submarines but also ships and the path of torpedoes, friendly or foe. Data was displayed on control terminals. It would command the submarine for attack and torpedo evasion but also took charge of an entire submarine group, making them the first command submarines in the Soviet Navy.

Sargan weapon control system:

This system enabled to control attack as well as torpedo homing, and the use of countermeasures by human command or automatically.

Okean automated sonar system:

Hull-mounted, providing target data to other systems, eliminating the need for crew members at its station.

This complex comprises the following:

- Enisey sonar

- Luch mine detection sonar

- Rosa-705 sonar

- Tissa sonar

- MG-512 Vint-705 own-ship cavitation detector

Sozh navigation system/Boksit course control system:

Both combined to integrated course, depth, trim, and speed control for the submarine. They had manual or automated modes with programmed maneuvering if needed, combined with bathymetric data, from maps and real time. This was the first soviet submarine “autopilot”, to some extent.

Ritm operation control system:

A cross-data system controlling operation of all machinery. This avoid any extra personnel to service the reactor, turbines, generators, batteries and auxiliary diesel.

Molniya communications complex:

Soviet 1966 satcom system. Could be operated from depht with a cabled buoy antenna. Communicating through the satellite family of the same name.

There were also Vint & Tissa radio communications antennas, and the MG-21 Rosa underwater communication telephone between submarines.

Alfa radiation monitoring system:

A TV-1 (television) optical system for outside observation including at periscope depth, but mostly used when surfaced in heavy weather. There was also an integrated NBC sensor.

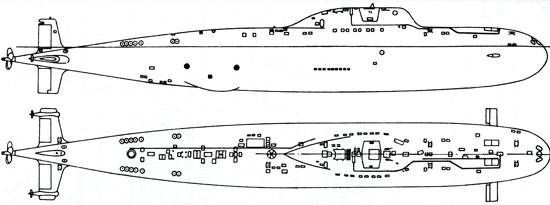

old profile by Mike1979Russia.

New profile by Mike1979Russia with 3d effects.

⚙ Alfa specifications |

|

| Displacement | 2,300 tons surfaced/3,200 tons submerged |

| Dimensions | 81.4 x 9.5 x 7.6 m (267 x 31 x 25 ft) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft OK-550/BM-40A LBCBMR 155 MWt, 40,000 shp (30,000 kW) steam turbine |

| Speed | 12 kn (14 mph; 22 km/h) surfaced, 41 knots (47 mph; 76 km/h) submerged |

| Range | Unlimited |

| Armament | 6× 533 mm (21 in) TTs bow, SET-65/53-65K, or 20 VA-111 Shkval, 24 mines |

| Sensors | MRK-55 Chibis radar, Okean sonar suite, MRP-23 Bulava-705 ECM, MVU-111 Akkord CCS |

| Test depth | 350 m (1,148 ft), c500 max, 1200m crush |

| Crew | 31 (all officers) |

Career of the Alfa class

K-64 (1969)

K-64 (1969)

Order for K-64 was given in 1962 and the crew started training o land facilities. K-64 was laid down at Admiralty Yard in Leningrad on June 2, 1968 April 22, 1969 and she was launched on December 31, 1971. Novo-Admiralty Shipyard worked under conditions of strict secrecy. However, despite this, the launch attracted a crowd of onlookers. She went out for testing, shipyard tests, and she was tracked by satellites and it was not long before the news fell on air, in fact through BBC radio. It was described as a “fundamentally new submarine” and called by defaul the “Blue Whale”. During testing however, one of the three heat exchange loops on the reactor’s primary circuit failed and she completed her trials with the power remaining. She was commanded by Pushkin A.S.

On December 31, 1971 she completed a new serie of tests, followed by state tests, certificate signed, and was officially commissioned and assigned to the 3rd submarine division, Zapadnaya Litsa.

As a lead ship built before the others, she covered 3,482 miles, hald underwater, and made 21 dives. However by the fall end of January 1972, the second of three loops of of the reactor’s primary circuit failed again. It was repaired, but in April more leakages ended in a brutal end, and the primary circuit completely froze. As it was built, the reactor safely shut down, and she was down to her backup diesel to try to go back to port until a tug arrived, and she was towed to Zvezdochka yard for eximantions and possible repairs, remaining her for more than a year. It was notably determine that the early OK-550 reactor was dedicedly too fragile the way it was designed. Other boats were delayed to accept a new reactor, completely reworked and tested hard to eliminate other potentiual issues, the BM-40A.

In 1973, the fate was still uncertain, but it was clear that replacing the entire reactor for an extra one wouldbe quite expensive. She had been cut in half for examination alkready, but no agreement on her repair was done. Eventually it was decided not to repair K-64, her bow was sent to Leningrad as simulator to train future crews of the class. Her 46th crew under Starkov V.V. at the time was reorganized and mixed with new recruits for K-373, the 5h boat of the serie. K64 stern with the frozen reactor compartment remained in Severodvinsk, serviced by the 32nd technical crew. Later the stern passed under control of Sibiryakov K.A. technical crew commander. Some jockinly referred her as the “longest sub in the world”.

In 1978, the stern was disposed of with the reactor compartment block first moored near Yagry Island and until 2015, kept afloat at the Sayda-Guba temporary storage facility. The same year it was decided to get rid of her bow section used for training as it no longer fits the latest electronics development, and it was abandoned and looted. it was later disposed of in the 1990s, but some sub-systems were kept as training aids at the Kirov training center.

K-123 (1976)

K-123 (1976)

K-123 was laid down at SEVMASH in Severodvinsk on December 22, 1967, launched on April 4, 1976 and completed on December 12, 1977.

September 1979 saw her first deep-sea dive to 400 meters in the Norwegian Sea and later she makes a new sortie with the crew of K-316< under command of Capt. RBoyko A.P., senior NSh Capt. Margulis P.M.

Betwene January and March 1980 she makes another sorties under captain Gaiduk V.V. and senior chief of staff captain Margulis, earning an "excellent" rating. She practice under ice navigation and shadows a NATO submarine by order of the fleet command.

In December her crew took 1st place in combat/political training in the division.

In 1981 she makes another patorl with K-432, again with “excellent” rating.

In April with K-432 and K-373 she takes part in the “Sever-81” exercise with the same “E” rating and declared “excellent” ship in the Northern Fleet. On 15-25 August she takes part woth K-432 to a search operation in the Barents Sea.

On 11 September her technical saw her transferred to the 2nd category reserve and on 12 October her crew is transferred to K-432 at Severodvinsk she she underwent repairs. On 13 October she is back in service and in December the crew returned under Capt. 1st Rank Abbasov A.U., which is awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union for his retraining. On March 15, 1982 she makes a new patrol with the 537th crew under command of Capt. 1st Rank Bulgakov V.T. and senior Capt. 1st Rank Grinkevich V.V.

On April 5, and alarm from the power plant went off on the control panel revealing the presence of an unusual floosing in the emergency condenser, which is removed acording to procedures, and a search began for the steam generator’s state. A preliminary check shows the starboard steam generator had an inter-circuit leak while the the port steam generator did not show an obvious sign of leakage. It is decided to shut down the starboard steam generator. On April 8 the steam generator it disconnected following an error, trigerring a power plant failure with release of liquid metal coolant into the reactor compartment with irradiation. The sub looses speed and it is decided to surface. The powerplant enters its natural cooldown mode and freezes. Enegry onboard is switched to the battery and diesel generator to send a radio message to fleet command.

The aircraft carrier Kiev and its escort, the cruiser Marshal Timoshenko, and rescue ship Altai arrived first. The first towing likes breaks, another is placed on the guardrail of the wheelhouse, secured to the foundation of the mine detection system and on April 12 she is back to base under tow. The enquiry later states the cause of the accident was clogging of steam generator tubes with sludge and corrosion.

On April 16 she is transferred to the 2nd category reserve and in August sent to Zvezdochka shipyard, Severodvinsk for decontamination work and dismantling of all radioactive parts. In September the main crew returns and in December she is transferred to No. 42 Sevmashpredpriyatie yard for final decontamination work and reassigned to the 339th technical team. In June< 1983 she is drydock.

In September the 595th technical crew is formed to fully repair K-123 and keep her operational until 1992. On December 21 work starts for full repairs, with the reactor compartment completely replaced, taken from a cancelled Project 705 nuclear submarine under construction in Leningrad for 8 years, the remainder was dismantled on slipway. It was decided in between to stop the Alfa serie. The emergency compartment is prepared for temporary storage afloat, listed as N°120 and 920 (Project 705) and later the reactor is transferred for temporary storage afloat in Sayda Bay. By Sept. 28, 1984 K-123 enters long-term repairs with the 168th crew disbanded.

In Dec. 1989 mooring tests starts and by November 1990 her new reactor is started. The 537th submarine crew is enlisted as second crew but in March 1992 March it is disbanded and in April 11, the 632nd submarine crew is formed instead a second crew of the submarine K-123. In June 3 she is reclassified as B-123 and in July her acceptance certificate is signed by Gulinin B.P. She departs for Zapadnaya Litsa and is assigned to the 33rd Submarine Division, 1st Submarine Fleet of the Northern Fleet. Until 1995 she makes patrols, exercises and takes part in fleet events.

In 1993 January-February she sails for the 270th Naval Training Center in Sosnovy Bor and by March 1994 takes part in ASW drills at the combat training range, when colliding with the trawler ‘Professor Klenov’ of the Murmansk trawler fleet at JSC Sevryba while submerged. Her stern trim increased and Capt. 1st rank Smelkov A.F. ordered an attempt to free his boat from the trawler net and surfaces, spots the trawler and context her by radio to ensure everything is ok and comes back to base to evaluate the damage.

In 1995 she is transferred to the 7th Submarine Division, 1st Submarine Fleet and in 1996 returns to the 33rd SubDiv, 1st Submarine Fleet. In July 31 she is decommissioned and laid up in Bolshaya Lopatka Bay, and in August 7 the 632nd submarine crew is disbanded. In May her reactor is shut down. By July 2001 she is reassigned to the 11th Submarine Division until Sept. 2002 and transferred to Gremikha (Murmansk) for unloading her nuclear fuel. Between 2005 and 2006 she is transferred to a civilian crew at “SRZ “Nerpa” in Gremikha for her reactor core to be unloaded. The hull is then transfered to Kut Bay at “SRP “Nerpa” in Snezhnogorsk for final disposal and cut up in 2007-2008. By Nov. 2007 her Reactor block is prepared for long-term storage, transferred to Sayda Bay un July 2008 and sent to RO Sayda temporary storage facility.

K-316 (1974)

K-316 (1974)

K-316 was laid down at Admiralty (Sudomekh) in Leningrad on April 26, 1969 and launched on July 25, 1974. She was completed and commissioned on September 30, 1978. Her 2nd crew is formed in 1968 as the 313th submarine crew and in July 24 1969, had completed training at the 93rd Training Center.

In August the crew arrived in Leningrad and enters the 39th Separate Squadron, Leningrad Naval Base. In 1971-1976 it repeatedly takes 1st place in combat and political training at the 39th Separate Squadron and is awarded the Brigade Commander’s Challenge Red Banner. In 1974 February-April training starts at the 33rd Submarine Division while hte submarine is launched in July and despite the secrecy and the fact the launch is made at night, the entire Neva embankment is filled with a crowd of onlookers. By June 1975 mooring trials starts, in October 7-22 1977 she is sent to Severodvinsk, Zvezdochka for sea trials and her crew joins the 339th Separate Squadron. In February 1978 she made comprehensive mooring trials and in June-July yard’s trials, and on 3-22 September State trials under 1st captain Rykov V.P.. An incident occured as her control system bugged and she is unable to drop her speed below 40 knots until the malfunction is solved.

On 30 September her acceptance certificate is signed by Melnikov E.P. and she is occicially commissioned, assigned to the 6th Submarine Division, 1st Submarine Fleet at Zapadnaya Litsa. March 1979 and May saw the 168th crew intensive training at sea, and she makes a first patrol in the Atlantic under senior Cdr. SubDiv 6 Capt. 1st Rifle Volkov V.V. and commander Boyko A.P. with a “good” rating.

By December she takes 1st place. By 7 September 1980 she sailed to Severodvinsk with the 313th crew on board submerged at 38.8 knots under 100 m when a navigation error sent her on the coastal slope near Cape Odinchizhny. She broached svery close from the shore, undamaged. She is later examined and received post-fixes at Zvezdochka. From September 1980 to June 1981 she makes anotehr patrol without incident. On June 7-12, she takes part in Sever-81 exercises.

Fropm October 1981 to February 1982 she is overhauled in dry dock repair at SRZ-10, Polyarny.

In March to May 1982 her crew is retrained and she makes another patrol with a “good” rating and by September 13-15 makes a sortie with the 46th crew but her 5th compartment is flooded and she returns to base.

From September to October she had repairs and is retransferred to the main crew. In April 1983 with K-432, K-493 and K-463 she takes part in “Okean-83”. In May-June she taks part in “Razbeg-83”. The 592nd technical crew is formed for her second overhaul, and in October 1983 she makes a cruise in the Arctic with the 313th crew under V.T. Prusakov, supporting the Project 941 TK-208 SSGN. While navigating under ice, the main switchboard caught fire, quickly extinguished, no casualties.

In October 1984 she makes an new patrol with “good” rating and until November works with the 46th crew, had dry dock repairs at SRZ-10 Polyarny but while prepared for her new patrol, a steam line burst open. A large amount of steam enters the 4th compartment. On 25-27 December after repairs she makes a short sortie with the 46th crew, delayed by 10 days. She is back on the 27 due to drinking water plant breaking down. In 1985 January-February she performs harbour training, and by June-July she makes a trials sortie in the White and Norwegian Seas. In 1986-1987 she is in “constant readiness forces” with more intense combat trainign sorties.

On December 1987 she os Withdrawn from service, and until 1988, operated by the 592nd technical crew. Transferred to Gremikha for dismantling and unloading the reactor as part of DesDiv 17. In January 1990 unloading operations starts, completed in February, at the time the first unloading of liquid metal cooled reactor in the Navy. She is towed to Zapadnaya Litsa, stricken, equipment recycling starts and by June she is sent to SubDiv 33 and her crew is reformed for another sub. By October her second crew is disbanded and in 1992 she is renamed B-316. In 1995 she towed back to Severodvinsk, 1st crew disbanded and she is disposed of at Severodvinsk. Her reactor storage is completed by Jan. 2002 in Sayda Bay in long-term storage.

K-432 (1977)

K-432 (1977)

K-432 was laid down at SEVMASH, Severodvinsk on November 12, 1967. She was launched on November 3, 1977 and completed on December 31, 1978. We are not going to dwelve into minutia about dates and concentrate here on main events. She is assigned to the 6th Submarine Division, 1st Submarine Fleet at Zapadnaya Litsa like her sister, and had two crews plus a technical crew attached. Her first patrol was in the summer of 1980 (168th crew, captain Mazin N.I. and Grinkevich V.V. of 2nd and 1st crews) in the Barents Sea and under ice. She takes part in the Sever-81 exercises and in the search and ASW operation “Concrete”. In th summer 1982 she conducted extended acoustic tests in the White Sea. In March 1983 she is Awarded the challenge prize of the fleet commander “For the best torpedo attack”.

With K-316, K-493 and K-463 she takes part in Okean-83 exercises.

From Sept. 1983 to mid-1984 she is in overhaul. She is decommissioned on April 19, 1990, for scrapping. Her reactor compartment is isolated in permament sotrage by 2002 in Sayda Bay facility.

K-373 (1978)

K-373 (1978)

K-373 was laid down at Admiralty (Sudomekh) in Leningrad on June 26, 1972, she was launched on April 19, 1978 and completed on December 29, 1979. Nothing of note in her early career.

In 1989, an accident happened in the reactor compartment (see notes). It was considered unsafe and costly to replace the reactor compartment and she was decommissioned April 19, 1990, sent for scrapping.

Initially, it was planned to store her reactor block on shore for 100 years, but that decision was later revised. In 2008, a scheme was developed for decontamination and stopping the release of radionuclides and then unload the second stage. First stage was completed in June 2009 and second in September. On September 17, 2009, removable parts of the reactor were unloaded at the Rosatom State Corporation (Gremikha). It was financed by the French CAE as part of a cooperation program with Russia, for 5 million euros. The unloaded parts were temporarily located in special containers on SevRAO, the process was completed on 2012-2014.

K-493 (1980)

K-493 (1980)

K-493 was laid down at SEVMASH, Severodvinsk on January 21, 1972. She was launched on September 21, 1980 and completed on September 30, 1981.

She started operations with the 168th crew assigned to SubDiv 6, 1st Submarine Fleet in Zapadnaya Litsa. After a few patrols she is in overhaul between Dec. 1982 and Jan. 1983 in Severodvinsk. She participated in the Okean-83 exercise. In 1984 due to the failure of the UERV-K air regeneration unit, the entire

voyage is carried out using V-64 plates and the crew breathed air with increased CO2. In 1985 she had another accident when radioactive alloy entered the 4th compartment and the crew worked for decontamination. She sailed bacl to base with irradiated aerosols in the air. In 1989 she had a serious leak in her feedwater system. She is withdrawn from service in 1989, towed to Gremikha to unload the reactor core, decom on 19 April 1991, transferred to SubDiv 33rd. She is dismantled from 1996 and in 2002 her three-compartment block in temporary storage at Sayda Bay.

K-463 (1981)

K-463 (1981)

K-463 was laid down at Admiralty yard in Sudomekh, Leningrad on June 26, 1975. She was launched on March 30, 1981 and completed by december 30, 1981.

Her crew was prepared from 1974 August 29, fromation complete in February 1975. In the spring 1981 she sailed from Severodvinsk to the Zvezdochka for sea trials and her crew integrated the 339th Separate Squadron. On December 30 her acceptance certificate is signed by Yudin A.A. and by 30 December she started her service at Zapadnaya Litsa. On January 26 1982 she joins the 6th Submarine Division, 1st Submarine Fleet and by April 16, she receives the 313th crew. In September she made a first patrol. One day had she notes a large leak in the 1st compartment. After surfacing on 27.09, assistant commander for electronic warfare, 3rd lieutenant captain I. Gorelov, is washed overboard while operating on an external system. By Decree of the Presidium of the Soviet Supreme on 23.02.1983 he is posthumously awarded the Order of the Red Star. She is back to base after 19 days at sea. The report is “unsatisfactory”.

By April 1983 she started a new cruise, with an exercises combining her with K-316, K-493 and K-432 as part of “Ocean-83”. This time all her training tasks are successfully completed. 1983 saw another patrol, no details given, completed in September.

The 594th technical submarine crew is formed for preventive maintenance.

Until 1984 she made another patrol with the 46th submarine crew, increased by 10 days with a rating “excellent”. She made another patorl that year, same crew and in 1985 with the 313th submarine crew. In 1986 she is recognized as the best in the Navy for antisubmarine training;

Spring 1987 and new patrols brought her another prize, best submarine of the Northern Fleet for ASW training. She taske dpart in 1987 Northern Fleet exercises and in November received the title “Excellent Submarine”, CiC Prize for anti-submarine training. In April 1990 she is prepared for decommission, laid up in Zapadnaya Litsa and by June 1991, transferred to the 33rd Submarine Division, 1st Submarine Fleet. Renamed B-463. In August 28, 1994 she stays in drydock at Severodvinsk.

By September 1994 her crew is disbanded and she is mothballed at the Northern Sea Route in Severodvinsk with her reactor block extracted and later transferred for temporary storage afloat, Sayda Bay.Scrapping is completed in between adn the ractor compartment is stored definitively in 2002.

General Assessment

The OK-550 and BM-40A just could not be maintained nor changed and they always freezed in the end, but on paper they allowed these expeptional submarines to be active for about 15 years. It was estimated that the entire reactor would be completely replaced for a prolongation of life. This was considered too expensive in the context of late USSR economy. Indeed these submarines lacked the modular design that would facilitate this reactor extraction and replacement. They needed to be cut in drydock for that operation, extrac the entire hull section, extract the plant, then rebuilt the plant and redo all the connections before replacing the hull section. This condemned in practice these submarine to short careers. The whole experiment with liquid cooled reactors was never repeated, but many other aspects of the design passed onto the next SSN classes, like the Sierra and Akula, even the Victor III recuperated some aspects of these experimental and grounbreaking boats, notably in terms of hull shape, some sub-systems, and heavy automation. They surely were a milestone in Soviet submarine design.

There were less incidents in this class than the infamous November, yet they had a few loss-of-coolant accidents: In 1971, bad welding on the steam system allowed moisture to leak into an area where it mixed with chlorides, condensed and dripped onto the primary coolant pipes in which flowed liquid metal coolant. On the long run this caused corrosion and eventually a rupture.

The second happened on the second serie Project 705K and in the case steam generator tubes in the evaporator section corroded, leaked steam into the primary system. Pressure increased but procedures which would have mandated the use of a relif valve and close a sensitive manometer was not done. High pressure broke the instrument and through it, projected highy contaminated Polonium-contaminated aerosols. Fortunately this was an operator-free area, and there was no casulaty but the reactor needed full replacement as it froze over.

The Alfa class never saw in combat but took part in cat and mouse manoeuvers with the US and British submarines in the 1980s and their acoustic signature was quickly classified. The peacetime plan was to have them deployed, shadowing US CBGs or major formation, to be ready to pounce in wartime. The US Navy after the remarkable intel work done by yhre CIA to confirm their construction, developed the ADCAP program, the British Royal Navy launched the Spearfish torpedo program. They were solely intended to destroy these “catch me if you can” submarines, and stayed relevant for decades later.

The Alfa class was to be the first generation of light, fast interceptor submarines, but the ambitious nature of their copbined innovation proved perhaps to much for the Soviet engineers at that time. Still, alazing speeds were indeed reached, but there were just too much traedoffs with their sensitive reactors and complicated and costly hulls.

Still, derivative designs were planned later such as the Project 705D with long-range 650 mm torpedoes, and the Project 705A ballistic missile variant that was a new SSBN high performance class designed to evade hunting SSNs. Instead, by looking at the west response, which was kot seeking extra speed of agility but the contrary (speeds wen down to 27-28 knots at best), efforts were made rather in stealth. This culminated in the late soviet era Akula-class.

Still the Alfa were grounbreaking in many aspects and their control systems was adopted for the Akula-class (roject 971), much larger but with a crew of 50, in fact designed as an hybrid between an Alfa and a Victor III.

Issues with the first sub, K-64, ledt to a decommission in 1974, jus after three yars service. In 1990 all were also decommissioned. The last, K-123 was saved by her refit between 1983 and 1992. A core freeze force complete replacement of her reactor. Se she served for a few more years, until 1996. Instead of her original liquid metal model she obtained a trusted, modern VM-4 pressurized water reactor and was used for training until decommissioned July 31. Disassembling the frozen reactor was impossible and it was stored until the end of the cold war. France’s atomic energy Commissariat designed and donated special equipment to be installed on the dedicated dry-dock SD-10 in Gremikha to properly remove and store the reactors until dismantled.

Interestingly, the post-cold war era saw a US covert operation, called Project Sapphire, to retrieve 1,278 pounds (580 kg) of very highly enriched uranium fuel intended for the Alfa-class submarines. They were stored at a warehouse at the Ulba Metallurgical Plant at Ust-Kamenogorsk (Kazakhstan) with little protection or supervision. These were cans of uranium oxide-beryllium ceramic fuel rods. There were rumored to be resold to Iran so they were extracted by the tiger team, flown and recuperated from three blacked out C-5 Galaxy cargo, over six weeks (1,050 cans of uranium), completed on 18 November 1994. These were carried to Oak Ridge.

Read More/Src

Books

Pavlov, A. S. (1997). Warships of the USSR and Russia 1945–1995. NIP

Polmar, Norman & Moore, Kenneth J. (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Potomac Books

Polmar, Norman & Noot, Jurrien (1991). Submarines of the Russian and Soviet Navies, 1718–1990. NIP

V. P. Kuzin, V. I. Nikolsky “USSR Navy 1945—1991” IMO St. Petersburg 1996

V. E. Ilyin, A. I. Kolesnikov “Submarines of Russia: An Illustrated Directory” Astrel Publishing House LLC 2002

“History of domestic shipbuilding” vol. 5 St. Petersburg Shipbuilding 1996

A. N. Gusev “Submarines with cruise missiles” St. Petersburg “Galeya Print” 2000.

Submarines of Russia Volume 4, part 1. Central Design Bureau MT “Rubin” St. Petersburg. 1996.

Reference information from S. S. Berezhnaya “Nuclear submarines of the USSR and Russian Navy” MIA No. 7 2001.

V.P. Kuzin, V.I. Nikolsky “USSR Navy 1945-1991” IMO St. Petersburg 1996

Apalkov Yu. V. Submarines of the Soviet Union. 1945-1991. Vol. III. – M.: Morkniga, 2012.

I. P. Bogachenko. Nuclear Titanium, 6th Submarine Division, Northern Fleet. St. Petersburg, 2013.

Dronov B. F. Design Studies for the Project 705 Nuclear Submarine of A. B. Petrov’s Group. 2003.

Links

Project 705 iterations and proposals on deepstorm.ru

navypedia.org/ ss k64

hisutton.com Alfa Class Submarine

russianships.info/ project 705.htm

navweaps.com/ Russian post WWII

https://www.veteranrosatom.ru/articles/articles_991.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20070521203333/http://www.submarine.id.ru/thumbs/705/index.shtml

http://www.deepstorm.ru/DeepStorm.files/45-92/nts/705/list.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20151121235804/http://vpk-news.ru/articles/1197

https://русская-сила.рф/typhoon/2001/705-2.shtml

https://web.archive.org/web/20151117021134/http://rocketpolk44.narod.ru/stran/pr705.htm

http://engine.aviaport.ru/issues/10/page12.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20240513185202/https://www.deepstorm.ru/DeepStorm.files/45-92/nts/705/K-463/K-463.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20050911025859/http://www.submarine.id.ru/sub.php?705

https://www.techinsider.ru/weapon/16141-submarina-istrebitel-proekta-705/

en.wikipedia.org/ Alfa-class_submarine

http://www.deepstorm.ru/DeepStorm.files/45-92/nts/705/K-64/K-64.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20090929090318/http://www.minatom.ru/news/17248_25.09.2009

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/russias-alfa-class-submarine-could-out-run-out-dive-anything-22121

reddit.com/ album internal sail area of the soviet navy

on ru.wikipedia.org/

Videos

On weapons detective

Военное дело. НТВ – Альфа из титана

Model Kits

Soviet submarine project 659 (NATO name Echo I) by OKB Grigorov 1:700

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign