The “dreadnought race” as a spark – Argentina just ended in 1904 a naval arms race with Chile when the Brazilian Government revealed the acquisition in UK of two brand new dreadnought battleships, the Minas Gerais class. Not only they were the best armed for their time but also the fastest, and most importantly the third built worldwide after UK and USA.

Despite the huge financial pressure put on local economics, a wild campaign in the press led to decide the construction of two dreadnought, and the 1908 open tender was launched on the international market. Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company won and both ships were laid down in 1910 and completed in 1914 and 1915. They completely outclassed the Minas Geraes in artillery arrangement and range, secondary armament, and speed, served through WW1, the interwar and WW2 after a summary modernization, while Argentina stayed neutral, stricken and BU in the 1950s.

Development history of the Rivadavia class

Rivalry with Chile

There were two reasons for the development and funding of the new battleships: The first was the Brazilian move towards dreadnoughts -and patriotic fervor- and the second was the old rivalry with Chile over decades of Argentine–Chilean territorial disputes, over Patagonia’s border and the Beagle Channel. The rivalry reached a peak when Argentina ordered four Garibaldi class armoured cruisers, but the British arbitration of the cordillera of the Andes Boundary Case in 1902 stopped these disputes and the naval race, fortunately for local economies. The “three pacts” also led the British government to seize two battleships in construction for Chile, which became the Swiftsure class while another gesture of good will led Argentina to resold to Japan two of her armoured cruisers in construction.

Debates over the Argentinian fleet

With a population twice as reduced as Brazil and economics not capable of generating the amazing Brazilian US$31.25 million available for the Navy, Argentina debate over the usefulness and wisdom of building two brand new Battleships, at a time Chile did not possessed one. The National Autonomist Party cabinet was in favor. But their 14,000 ton battleships and ten destroyers naval plan was not popular. Aware of this, the American ambassador to Brazil warned his Department of State of the effects of a naval race there. There were some pressures, but like in Brazil, they were brushed aside.

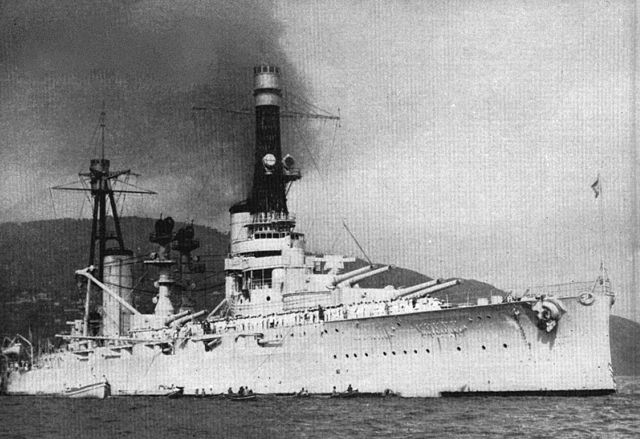

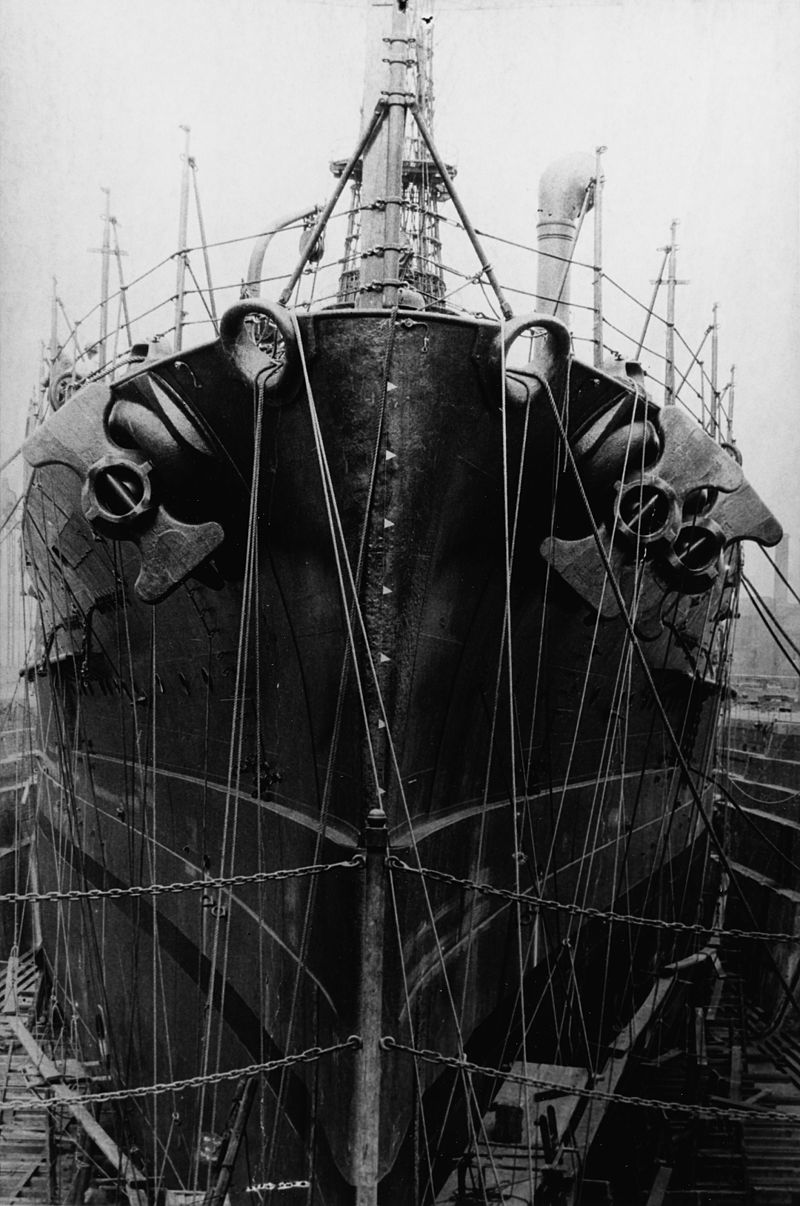

Rivadavia in speed trials, 1915

Eventually renewed border disputes notably over the River Plate area relaunched the initiative, well relayed by the press which, through inflammatory headlines, gradually inflexed the popular opinion. The initial plan called $35 million and $7 more on loans but it was later transformed into $55 in August 1908. Argentina in fact, hoping to stop the naval race proposed Brazil to buy one of her two brand new battleships, which was flatly refuse. The government then turned to Europe and placed a bid.

The 1908 bid

The bid offered to all major national naval industries of Europe, able to built dreadnoughts, sparked a lot of interest, as it was accompanied by twelve destroyers. Fifteen shipyards (United States, Great Britain, Germany, France, and Italy) answered the call, with diplomatic pressures given the sums advanced (nothing new under the sun!), especially from the first three. Requirements were intentionally vague to left room for domestic practices and innovations.

In the US, confidence from various shipyards over this bid was not great. They feared the traditional bonds with Europe will play again, if they did not have an active support from their government. The latter bowed to their demands, and proposed a thee-prone offensive, with the removal of import tariffs on hides from Argentina, promises for additional concessions and offer to include for free the latest developments in fire control systems and torpedoes on the market. But there was still opposition to this in the USA themselves, while naval commission was pro-British, President Roque Sáenz Peña favored Italy, and the war minister, Germany, to standardize land and sea equipments.

However the US cause found an ardent support, the chief editor of newspaper La Prensa, which had a large audience at the time. Soon it revealed British wrongdoing in a naval contract. Under pressure, the commission which favoured Italy first and Britain second had to give some room to the US offer; Suddenly, the commission threw out the opening tenders and announced a much more precise set of specifications with three weeks for all bidders to comply. These specs were updated by combining all the best aspects seen on these various designs, levelling up the whole design.

In the end, it was found both the Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Company and Fore River Shipbuilding Company were the lowest bidders on these new specs. And were chosen, which came as a surprise. At the end despite a lower bid at the last minute by Armstrong Withworth, American diplomacy, multiplying initiatives, stole the show in Argentina. The US design however was smaller, less protected and not as fast but a slight margin. To compensate, the rest of the order concerning destroyers was attributed to Britain, France, and Germany.

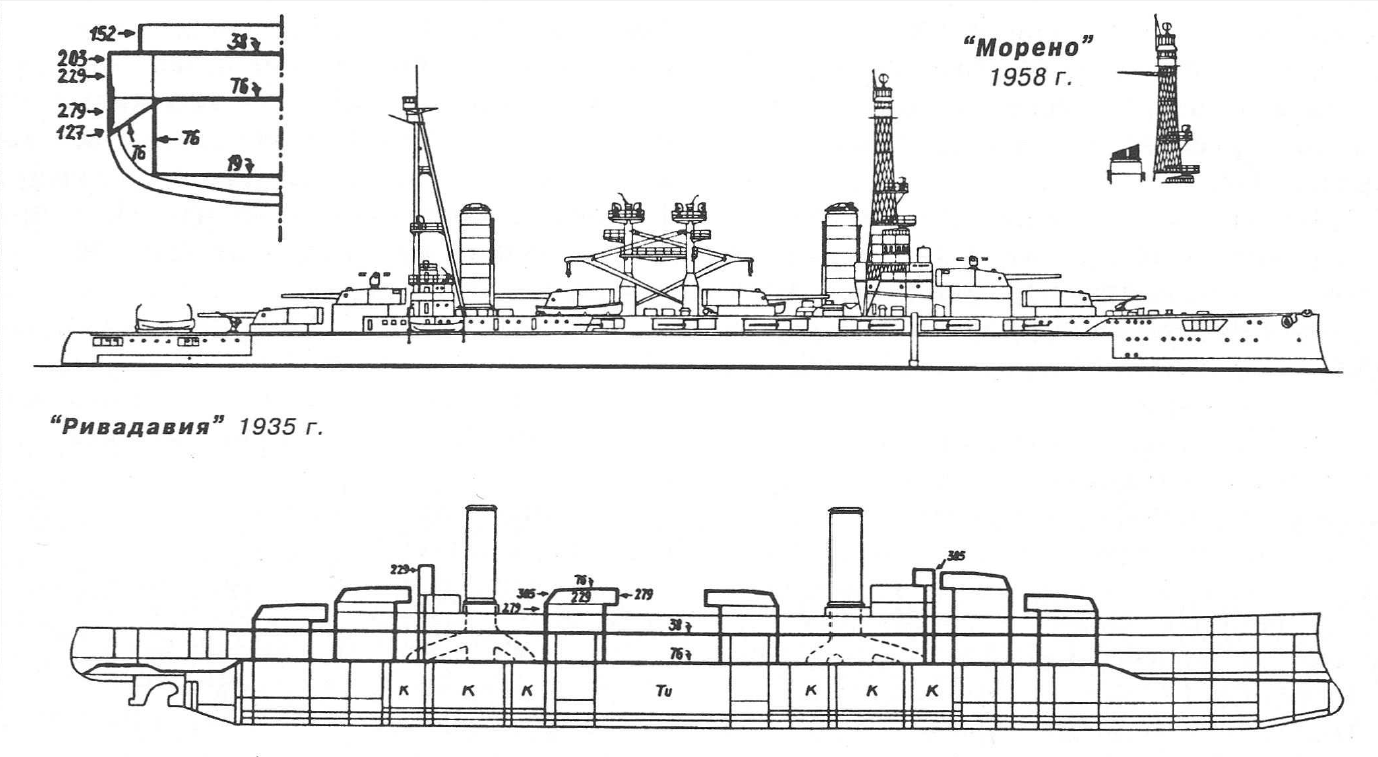

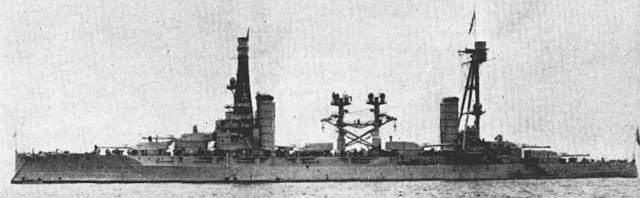

ARA Moreno in 1958

This went with some official complaints too: A naval architect coined the bidding process as “unethical” and British press unleashed its deception. Germany also complaints about allegation of the bids passed onto the Americans eyes to a commission member, and the diplomatic deals. On the other hand, American newpapers, after congratulating the win, boasted about the combined “battleship might” of the American continent -North and South- including the Minas Geraes class, talking of the five biggest capital ships in the world.

Construction

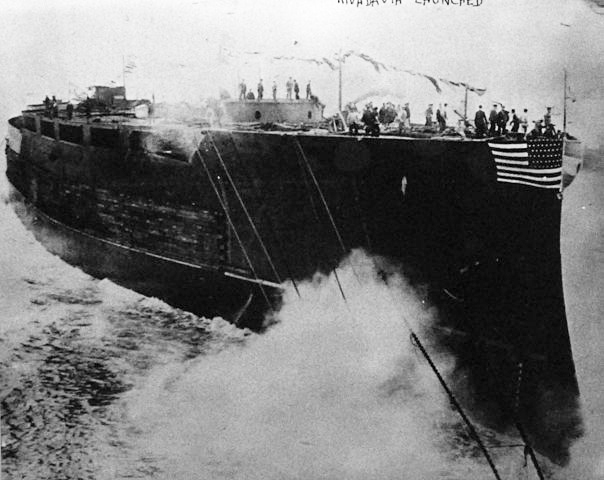

Rivadavia was laid down at Fore River Shipbuilding Company (Massachusetts) on 25 May 1910, launched 26 August 1911 and commissioned on 27 August 1914. ARA Moreno was built at New York Shipbuilding Corporation (Camden, New Jersey), laid down on 9 July 1910, launched on 23 September 1911 and commissioned on 26 February 1915. They started their sea trials on the east US coast. They were named respectively after the Bernardino Rivadavia, the first Argentinian president, and Mariano Moreno, a member of the first Argentine government.

Trials

Just as the Minas Geraes for the Royal Navy, the Rivadavia draw a lot of interest from the U.S. Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey. Its head remarked that the Rivadavia in trials “handle[d] remarkably well … with comparatively minor modifications the vessel would practically meet the requirements of our own vessels.” However the Board of Inspection remarked the position of the wing turrets could cause blast damage to the dish in the smokepipes and uptakes. However the trials also revealed engine trouble soon after completion, damaged turbine on Rivadavia and failure on the Moreno.

Soon after the battleships were received, a change of government and policy made the adoption of the Rivadavia less desirable. After Rio de Janeiro was resold to Turkey (and later requisitioned by the RN as HMS Agincourt), the new authorities thought to resold them. There was a contract provision allowing the US government to acquired them to prevent any sale, but the US Navy did not wanted them. Already some of their features were obsolete like the absence of the “all or nothing” armor arrangement.

At the same time bills directing the sales were defeated by the Argentine National Congress in the summer of 1914. Eventually, despite strong interest from Italy, the Ottomans, and Greece the British government pressured the US Government to not allow these ships to be purchased by Germany. US Pressure, which allowed warned about neutrality and technology transfers, put enough pressure on the Argentinians to maintain their purchase.

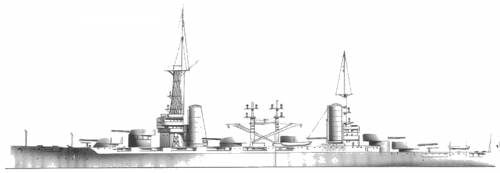

Design of the Rivadavia class

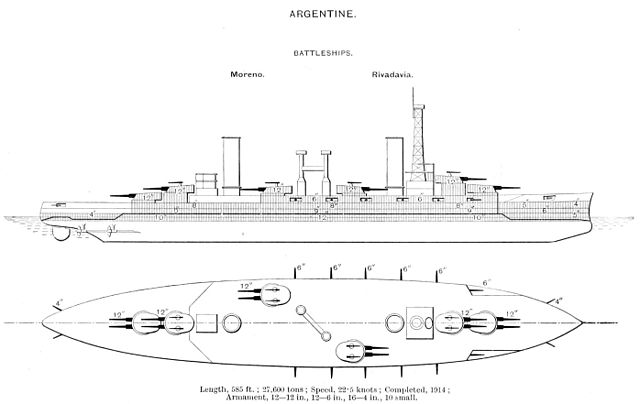

The design was singular as it combined elements from five nationalities and reflected shipyard practices of the time: The basic plan was inspired by a Fore River design for a fourteen-gun armed battleship with wing turrets, forward superfiring ones, and three on the same level at the rear. The wing turrets were British-inspired, the secondary battery of 6-in gun German in inspiration and the engines rooms arrangement was reminiscent of the Italian Dante Aligheri design. Their US origins were betrayed also by the typical corbel mast at the front (the rear one was a reduced pole) and solid gooseneck cranes to lift the boats between both wing turrets en echelon.

The hull was not flush-deck but had a long casemate and aft bridge, it was roomy, 594 feet 9 inches in length (181.28 m) overall by 98 feet 4.5 inches (29.985 m) i width, and a draft ranging from 27 feet 8.5 inches (8.446 m). Displacement was 27,500 long tons (27,900 t) and up to 30,100 long tons (30,600 t) fully load. The crew comprised 130 officers and about 1000 sailors.

Powerplant

Both ships received the same Brown–Curtis geared steam turbines mated on three propeller shafts. They were fed by 18 Babcock & Wilcox boilers. These were rated for 40,000 shaft horsepower (30,000 kW), enough for a top speed of 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph), possibly even more. Their radius of action was about 11,000 to 7,000 nautical miles (20,000 to 13,000 km; 12,700 to 8,100 mi) at 11 knots; The boilers were mixed-fired with coal and oil, and a provision of 3,900 long tons (4,000 t) of coal and 590 long tons (600 t) of oil.

Protection

The armor protection they received was proportional to their main artillery and standard for the time, although relatively thin as repartition was old school: The belt was 12-in at its thickest amidships, raised 5 feet (1.5 m) above the waterline, and 6 feet (1.8 m) below, with a decreasing thickness down to 5-in (130 mm) to the prow and finally 4-in (100 mm) at the stern. Main gun turrets had heavy armor 300 mm front, 9 inches (230 mm) sides, 9.5-in (240 mm) back, and with 4-in (100 mm) on top. Deck were protected by .5 in (13 mm) plates, up to 2 in (51 mm) on the upper level, in Harvey nickel steel.

Armament

The main armament comprised twelve guns in twin turrets, and a mixed secondary battery, mixing 6-in and 4-in calibers. There was no smaller gun. This was completed by two submerged broadside TTs.

The Bethlehem steel 12″/50 guns were close to the ones used on the Wyoming class, mark 7. There were two superfiring pairs fore and aft and two wing turrets en echelon, about the same design as the Minas Geraes. There theoretical traverse was limited by potential blast damage. It was only 90° for the wing turrets; Six guns could fire fore and aft in theory. 1,440 rounds were stored in total. Thet were assisted by Barr & Stroud rangefinders.

The secondary battery comprised twelve 6 inch (152 mm)/50 guns in barbettes, each protected by 6-in armor too with 3,600 rounds in reserve. The second secondary (or tertiary) battery was composed of sixteen 4 inch (102 mm) unprotected guns mounted on the open, on turrets and superstructure to deal with marauding destroyers, with 5,600 rounds in reserve. They were Quick-firing US models also used later on standard destroyers, and certainly more hard-hitting than the British 3-in guns; In 1924 some were deposed to make room for four 3-inch AA guns and four 3-pounders. This was completed by the two 533 mm (21-in) torpedo tubes, with 16 Whitehead torpedoes in reserve.

Specifications of ARA Rivadavia (WW1) |

|

| Dimensions | 181.3 x 29.30 x 8.4m (594 x 98 x 27 ft) |

| Displacement | 27,900 t, 30,600 t FL |

| Crew | 1900 |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts Brown-Curtis turbines, 18 B&W Boilers, 40,000 hp |

| Speed | 22.5 knots (25.9 mph; 41.7 km/h) |

| Range | 13,000 km at 15 knots (17 mph; 28 km/h) |

| Armament | 12x305mm/50 (6×2), 12x152mm/50, 16x102mm, 2TTs 21-in. |

| Armor | Belt: 12–10 in, 12 in (305 mm) turrets and CT, 91/3–61/5-in casemates |

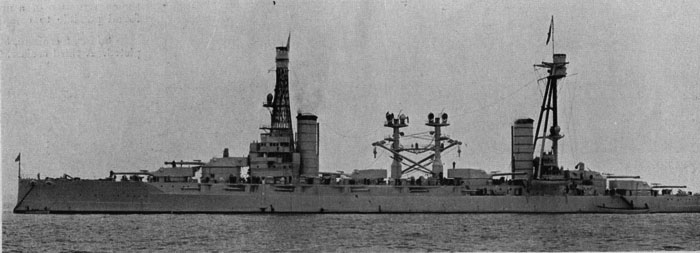

The ARA Rivadavia in service

Rivadavia arrived in Argentina by February 1915. In the early 1920s, she spent time in the reserve due to an economic depression. In 1924 both were modernized in the US as funds were available. This included fuel oil boilers only, a brand new fire-control system, new telemeters installed on a rear tripod mast, new superstructure bridge, and many other detail modifications. from 1927 to 1930 they participated in fleet exercises, and from the early 1930s started world training cruises intertwined with diplomatic trips.

Rivadavia’s travelled in Europe in 1937, visited Brest, Wilhelmshaven, Bremen, and Hamburg. With he sister ship she made in 1939 a training cruise to Brazil with naval cadets.

When the war broke out, both were escorted back home by destroyers sent from Argentina. As Argentina stayed neutral, they remained inactive. Rivadavia however made a diplomatic cruise to Trinidad in Venezuela, and Colombia after the war in 1946. Back home she stayed in active reserve until 1948, and full reserve afterwards, stricken only on 1 February 1957. She was scrapped in Italy in 1959. By selling both battleships and the armored cruiser Pueyrredón, Argentina was able to purchased a ww2 aircraft carrier, renamed ARA Independencia.

The ARA Moreno in service

Moreno arrived in Argentina by May 1915 but after WW1 ended (she remained inactive due to the neutrality policy), she spent time in reserve, caught by the economic depression. In 1924-26 she was refitted in an US shipyard converted to fuel oil, receiving a modern a new fire-control system and AA artillery. Moreno visited to Brazil in 1933, with Argentine president Agustín Pedro Justo. She made a second diplomatic trip in 1934 to mark the centennial of Brazilian independence.

In 1937 she travelled to Europe, France and Germany together with Rivadavia and was present at the British Spithead Naval Review. The New York Times described her as a “vestigial sea monster” in the battleline. She also made a training cruise to Brazil with cadets in 1939, but when the war broke out she had to be protected by destroyers back to Argentina.

Morena stayed inactive during WW2. She stayed and returned in reserve in 1948 and was ultimately stricken from the naval register on 1 October 1956. She was sold for BU to Japan in 1957. She was towed there in only 96-day, which was a world record at that time.

Author’s illustration of the Rivadavia class in the interwar

Read More/ Src

Conway’s all the word fighting ships 1906-21 1922-46

Burzaco, Ricardo and Patricio Ortíz. Acorazados y Cruceros de la Armada Argentina, 1881–1982. Buenos Aires: Eugenio B. Ediciones, 1997.

Garrett, James L. “The Beagle Channel Dispute: Confrontation and Negotiation in the Southern Cone.” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 27, no. 3 (1985)

Livermore, Seward W. “Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925.” The Journal of Modern History 16, no. 1 (1944)

Martins, João Roberto, Filho. “Colossos do mares” Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional 3, no. 27 (2007)

Scheina, Robert L. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

Whitley, M.J. Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis

“Historia y Arqueología Marítima” (HistArMar)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rivadavia-class_battleship

https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/tags/ararivadavia/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign