Japan, 1937-44. Zuihō (瑞鳳), Shōhō (祥鳳)

Japan, 1937-44. Zuihō (瑞鳳), Shōhō (祥鳳)WW2 IJN Aircraft Carriers:

Hōshō | Akagi | Kaga | Ryūjō | Sōryū | Hiryū | Shōkaku class | Zuihō class | Ryūhō | Hiyo class | Chitose class | Mizuho class* | Taihō | Shinano | Unryū class | Taiyo class | Kaiyo | Shinyo | Ibuki |The double life of the Zuihō pair

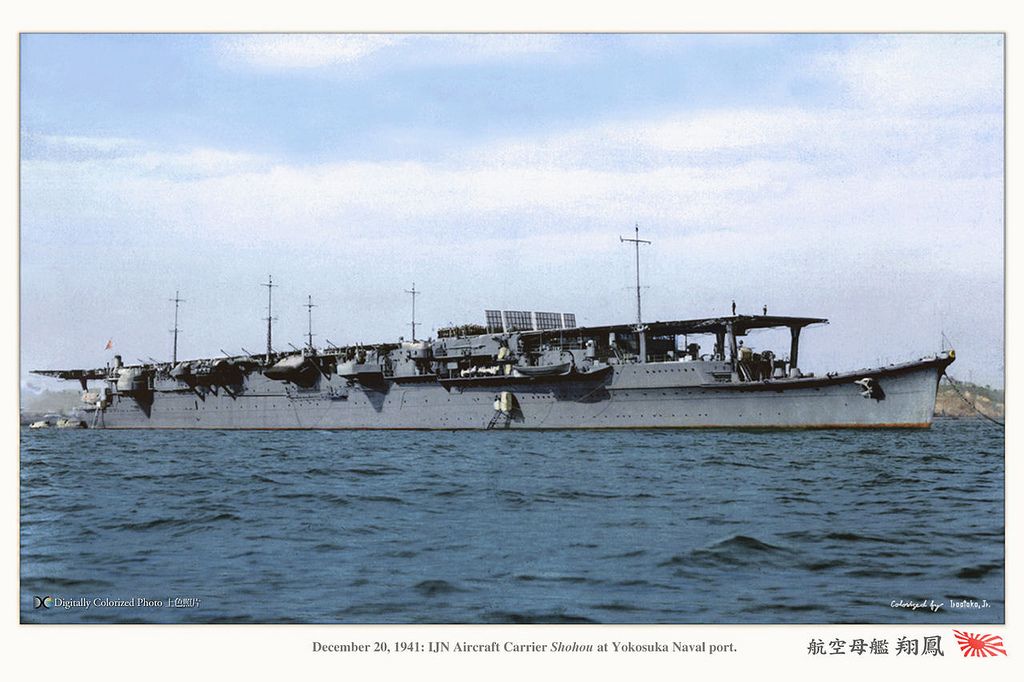

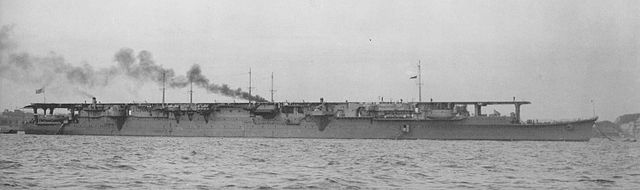

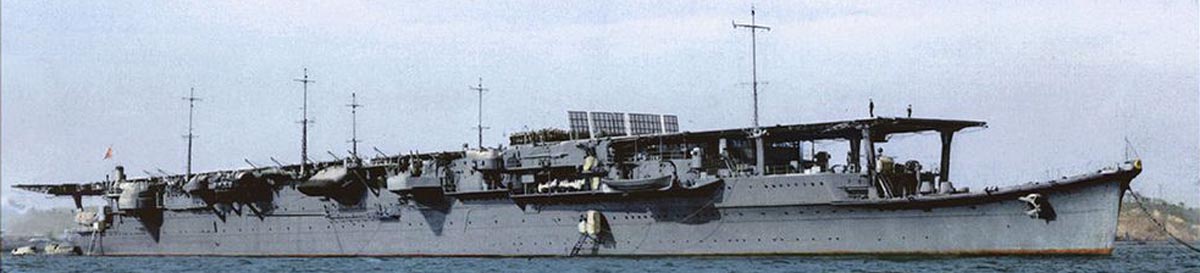

Digitally colorized photo of IJN Shoho in December, 20, 1941 at Yokosuka by irootoko Jr.

Always keen on cheating on the Washington Naval Treaty, the IJN staff planned a way to circumvent the limitations imposed upon them, by crating “convertible” vessels, declared as auxiliaries left free as per treaty conditions, but planned at the start to be transformed as aircraft carrier in a few months in wartime, that would have made the treaty obsolete. Four ships were concerned: The first of these were the IJN Taigei, Tsurugisaki and Takasaki, all seaplane tenders, followed by the Chitose, Chiyoda, Mizuho and Nisshin, all seaplane carriers, not capped in any way. Potentially in 1941, the IJN could reinforce its fleet with seven light aircraft carriers in far less time than required to built entirely new ships on purpose. Even smaller than regular fleet carriers, this was an appealing prospect.

The Imperial Japanese Navy Zuihō and Shōhō were therefore two seaplane tenders converted in 1940 into light aircraft carriers. They saw a very active, but relatively short service in their second life. They mirrored another class of auxiliaries also converted at the same time, the Chitose class. Taigei became IJN Ryūhō, but IJN Nisshin and Mizuho were never converted.

After it was decided to convert them as carriers, both completed in early 1942, Shōhō took part in Operation MO (New Guinea) but sank by aviation at the Battle of the Coral Sea (7 May), the first IJN carrier sunk in WW2. Zuihō played the second-fiddle at the Battle of Midway in mid-1942, she however participated in the Guadalcanal campaign, lightly damaged at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, then to the battles of the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf in 1944, part of the decoy force, she was caught by TF 58, used until then as a ferry carrier and training aircraft. But was this conversion justified after all ?

First life: The Tsurugizaki class submarine tenders

The shipbuilding programmed three large and fast submarine tenders in 1933, to be name later IJN TAIGEI, TSURUGISAKI and TAKASAKI in service of the submarine flotillas currently in formation for long range Operations, including more direct support. On 3 December 1934 at Yokosuka was laid down a new “flexible” design completed as oil tanker and submarine tender but which could be converted in a short notice or aircraft carrier as needed. On 1st June 1935 she was launched as IJN TSURUGISAKI.

In September 1935 the Combined Fleet’s Great Maneuvers conducted in the NW Pacific between Japan and the Kuriles saw the sub tender IJN TAIGEI attached to the Fourth Fleet (“Red Fleet”) which encountered a major typhoon. RYUJO, several cruisers and destroyers were badly damaged, revealing grave strenght weakness. TAIGEI herself at some point listed to than 50°, enough for seawater to pour in, flooding her engine and almost capsize her. Temporally uncontrollable, IJN TAIGEI is eventually saved by her crew, but when back in drydock showed massive wrinkles on some of the deck plates, close to her bridge.

In September-October 1935 a comprehensive report was written after the storm, leading to structural recommendations for most Japanese ships of the time, between strenght stabilization effort, notably by reducing weight above the waterline whereas electric welding is cancelled for a return to river assembly until the technique is perfected. Therefore on 7 October 1935 while TSURUGISAKI is in construction, many design changes are made, delaying her completion. Captain Miki Otsuka was appointed Chief Equipping Officer (CEO) for this phase.

From 1 December 1936 he is relieved by Captain Ko Higuchi and the new ships is completed, carrying out her first sea trials in November 1938, off Tateyama. She reached 29 knots. On the 15th, Captain Tsunekichi Fukuzawa takes command for final pre-commission trials and testings, as well as crew training. On 15 January 1939 finally completed four years after being launched, the new fleet tender os commissioned in the IJN. Sje only carried three floatplanes and armament training soon starts, while Captain Fukuzawa stays as her CEO.

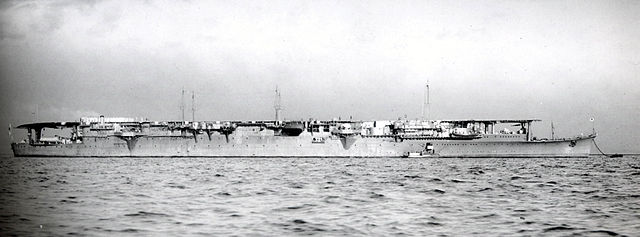

The lead ship IJN Tsurugizaki, was to be followed by Takasaki. However contruction was stopped soon after launch, never to be resumed. She was directly completed as an aircraft carrier, not showing any photo under this name. She was commissioned as Zuiho in December 1940 and followed by the decommission in early 1941 of Tsurugizaki for her own conversion, recommissioned as IJN Shōhō in early 1942, Takasaki being used as a model for the conversion.

Indeed, on 5 February 1939 she is attached to Rear Admiral Sanjiro Takasu with SubRon 2 (Submarine Squadron 2), 2nd Fleet. She spent the rest of the year training with the squadron’s submarine, performing various deployments. On 15 November 1939 Captain Jotaro Ito takes command and the fleet tender is reassigned that same day to SubRon 1, 1st Fleet. One year later, after more training deployments, Captain Takatsugu Jojima takes command and she is detached from SubRon1, placed in reserve as decision was made to convert her to an aircraft carrier. For this, she sailed to the Yokosuka Naval Yard dock, still busy with fitting-out her sister-ship, IJN ZUIHO. Once she is completed, the drydock is freed for the future Hosho. The name signified either “lucky” or “auspicious phoenix”.

Tsurugizaki off China, 1937. The first was in commission from 30 September 1937 to mid-1941 as submarine tender, but Takasaki was only commissioned as an aircraft carrier, rebuilt and renamed.

Tsurugizaki, colorized by irootoko Jr.

Tsurugizaki off China, 1937. The first was in commission from 30 September 1937 to mid-1941 as submarine tender, but Takasaki was only commissioned as an aircraft carrier, rebuilt and renamed.

⚙ Tsurugizaki Specs 1937 |

|

| Dimensions | 205,5 m long, 18.2 m wide, 6,58 m draft |

| Displacement | 11,443 t. standard -11,262 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | 2 steam turbines, 4 boilers, 52,000 hp. |

| Speed | 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) |

| Range | 7,800 nmi (14,400 km; 9,000 mi) at 18 knots (33 kph, 21 mph) |

| Armor | See notes |

| Armament | Presumably 2×2 127 mm (5 in) DP guns, 2×2 25 mm AA guns and/or 2×2 13.2 mm AA |

| Crew | 600 |

Conversion as Aircraft carriers

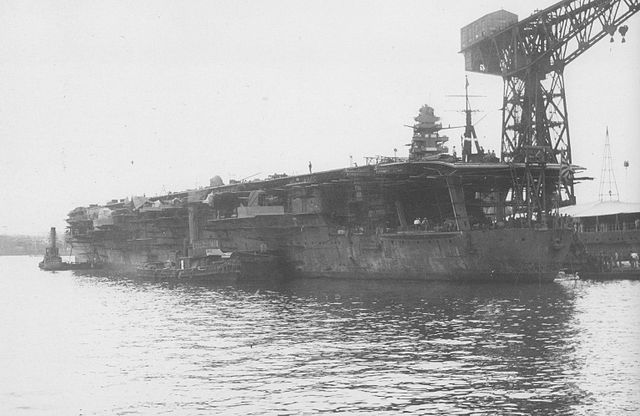

Shoho under conversion, 1941

Hull and caracteristics

After their conversion, they measured both 205.5 meters (674 ft 2 in) overall, for 18.2 m (59 ft 8 in) in beam, 6.58 m (21 ft 7 in) draught and displacing 11,443 tonnes (11,262 long tons) standard. They were served by a crew of 785 officers and men, not counting the air crew.

These were singular ships at many levels: The Kagero class destroyer powerplant gave them the required top speed, compounded by a very favourable hull ratio of 11:1, a long and narrow hull without island which recalled the arrangement and architecture of carriers seen on IJN Ryujo. They also had an additional funnel smoke tube aft intended for exhaust gases of diesels-generators. The captain and staff commanded her from the bridge constructed below the flying deck, left perpetually in the shadow and with a view hampered by the foward deck support pillars. Electric lighting was mandatory, especially in bad weather with limited visibility.

Powerplant and funnels

Their initial diesel engines (29 knots), were replaced by destroyer-type geared steam turbines (52,000 shaft horsepower, 39,000 kW), with the steam coming from four Kampon water-tube boilers. However due to the displacement increasing, top speed fell by 1 knot at 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). Exhausts went through a single downturned starboard funnel. Both carried 2,642 tonnes of fuel oil for 7,800 nautical miles (14,400 km; 9,000 mi) at 18 knots.

Flying Deck and Facilities

They had a flight deck 180 m (590 ft 6 in) long by 23 m (75 ft 6 in), with a single hangar 124 m (406 ft 10 in) long, 18 m (59 ft) wide, pierced by two octagonal centerline aircraft elevators. The forward measured 13×12 meters (42 ft 8 in × 39 ft 4 in), the smaller aft 12×10.8 meters (39 ft 4 in × 35 ft 5 in). They had an arresting gear with six cables but no catapult. They also lacked an island superstructure to maximize space, the command bridge being located below the forward overhanging flight deck. Due to their small size, they only carried 30 aircraft, a third of the Zuikaku class.

Armament

Primary armament comprised eight (four twin) 12.7 cm/40 Type 89 anti-aircraft guns, on sponsons. Initially fitted with four twin 25 mm Type 96 light AA guns in sponsons, this was extended in 1943, up to 48 of them and in 1944 twenty more, plus six 28-round AA rocket launchers.

Protection

Armour was absent, but local protection of magazines and petrol tanks with double sides was used, as well as standard cruiser ASW protection, and spaces between fuel and avgas tanks double sides being filled with water.

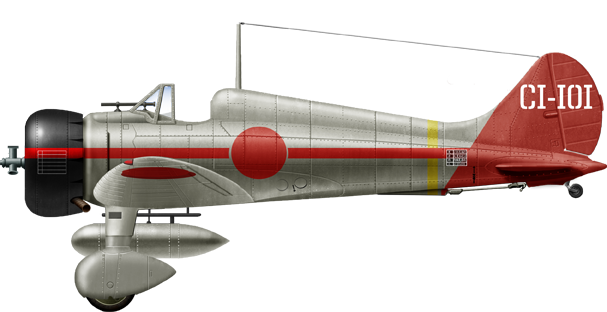

Zuiho class air group

Mitsubishi A6M-1 Zero with folded wingtips

Dring their career, while they had a maximum, nominal air group of 30 planes, they carried often less. In March 1941 for example, Zuiho carried sixteen A5M4 and twelve B5N (28). In May 1942, IJN Shoho carried a mix of six A5M4, six A6M2 and nine B5N, so 21 planes in all. They traded their A5M later than other fleet carriers, but by the time of Midway, had transitioned to the “Zeke” for good. Their air group stayed the same until 1944. After the loss of Hosho, Zuiho was successively equipped with 15 A6M2, 6 A6M5 and 9 B6N in February and for the Battle of the Philippines Sea, and 15 A6M2, 4 B5N, 11 B6N (30 total) in October, for the Battle of Leyte.

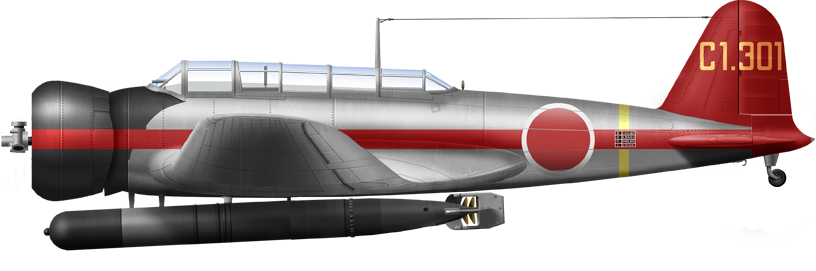

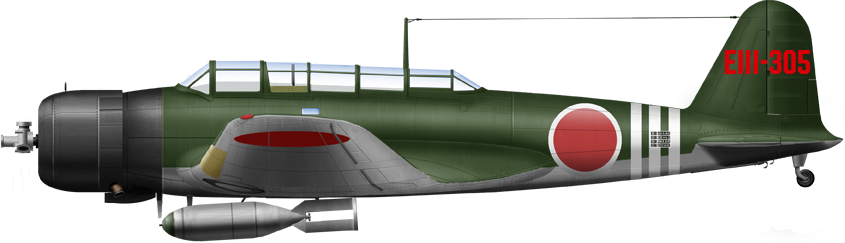

A5M-4, IJN Zuiho, early 1942

Nakajima B5N-1, IJN Zuiho, early 1942

Nakajima B5N-2, IJN Zuiho, Battle of Santa Cruz October 1942

Modifications

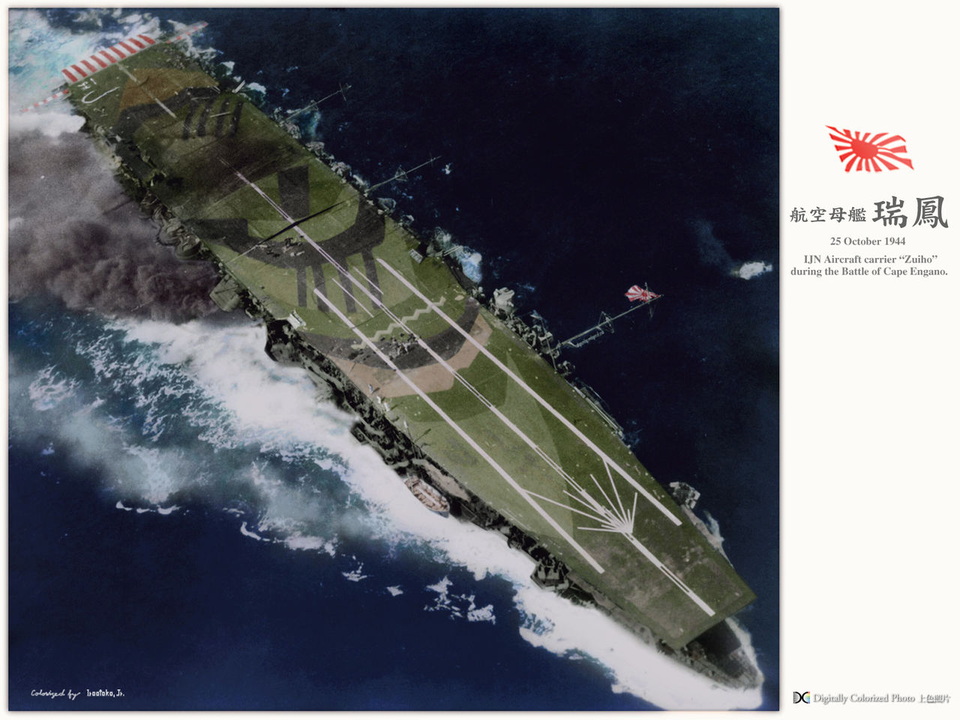

The famous camouflage of Zuiho’s flight deck at the battle of Cape Engano, Leyte, October 1944. Colorization by Irootoko jr.

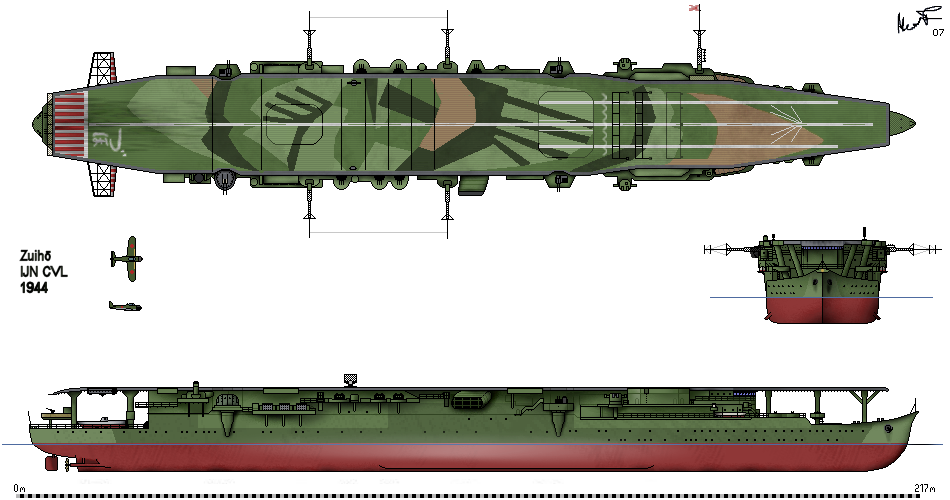

In 1943 Zuiho had her flight deck lengthened to 192.6 m (631 ft). She also received four additional twin 25mm/60 AA guns and sixteen triple 25mm/60 Type 96 (so 56 in all) and a type 1 2-go radar. In October 1944, she had twenty aditional single 25mm/60 (so now a grand total of 76 AA cannons) and six 28-barrelled 120mm AA Rocket Launchers. Her flight deck was painted in a very peculiar camouflage, mostly using green tones, as her hull, with a dark green camouflage amidship to make her “shorter” by illusion than she was. The green-based camouflage became mandatory for IJN aircraft carriers in 1944 but the design of her flight deck is quite unique.

Author’s illustration of IJN Shōhō in 1944, Leyte battle.

CC Profile of the Zuiho class

⚙ Zuiho Specs 1941 |

|

| Dimensions | 205,5 m long, 18.2 m wide, 6,58 m draft |

| Displacement | 9,000 t. standard -10,100 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | 2 diesels, 30,000 hp. |

| Speed | 29 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) |

| Range | 7,800 nmi (14,400 km; 9,000 mi) at 18 knots (33 kph, 21 mph) |

| Armor | See notes |

| Armament | 4×2 127mm AA, 4×2 25 mm AA, 30 aircraft |

| Crew | 1660 |

General assessement of the Zuiho class

Shoho in 1942

If having a fleet tender that can be converted into an aircraft carrier in wartime to circumvent peacetime tonnage limits seemed a good idea to the IJN staff in 1933, when it was actually time to convert them in 1939, aviation technology had made great leaps forwards, the new models being way heavier and larger. The initially optimistic air group of 50 was now reduced to just 30 planes. If it could be on paper split in three with an equal number of fighters, bombers and torpedo-bombers, it soon appeared that the most practical air group for them was to have more fighters and versatile torpedo-bombers. They went from the A5M/B5N models to the A6M/B5N in 1942 and A6M/B6N in 1944, just two types being easier to manage.

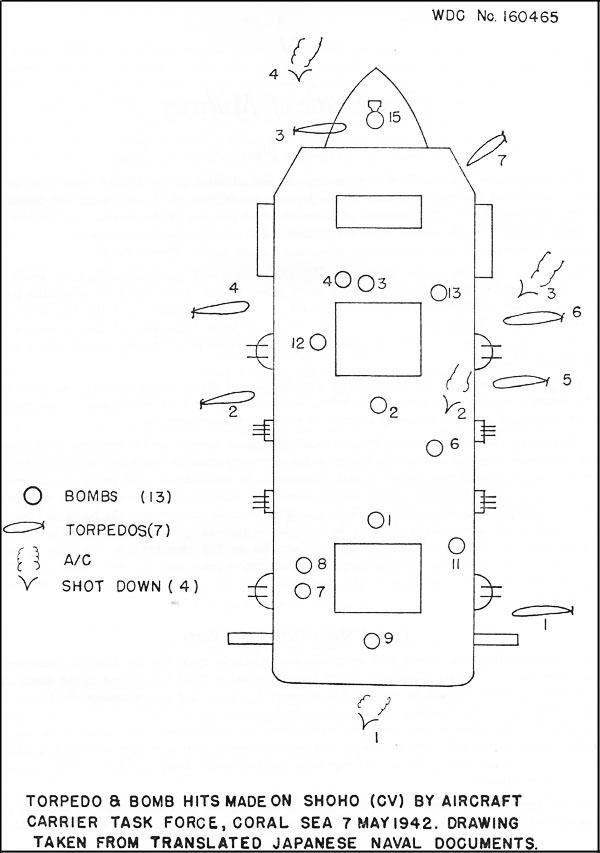

Shoho’s USNI battle reported hits.

The lack of an island for C&C was diversely appreciated, precluding their use as flagship, and making their deck management more complicated, although pilots appreciated the unrestricted deck for landings. A bit like the US Independence class, they played an almost auxiliary role in operations, poviding the bulk of the air group for CAP, in order to allow fleet carriers to manage more of their own planes ot lead the attacks.

Camouflage of Zuiho in 1944

IJN Zuiho career

Zuiho at the battle of cape engano

After commission IJN Zuihō remained in Japanese waters, until late 1941 and Captain Sueo Ōbayashi was her sole prewar, and wartime captain, assuming command on 20 September. Hs ship became flagship of the Third Carrier Division, and assigned to the 11th Air Fleet in Formosa, starting on 13 October to gather her air group, which trained with her. She arrived in Takao and was by early November with Third Carrier Division, followed by a brief refit. With her sister ship Hōshō in the same division she accompanied the cover force, comprising six battleships, waiting at sea the return of 1st Air Fleet (Kido Butai) from the attack on Pearl Harbor, arouind the 14-15 December.

In February 1942 she ferried Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighters to Davao City in the Philippines, on behalf of the 11th Air Fleet. She was transferred to the First Fleet, after the Third Carrier Division was disbanded, on 1 April. Remaining in Japanese waters until June, she participated in the Battle of Midway. Assigned to the invasion force cover, she had at the time six Mitsubishi A5M “Claude”, six A6M2 “Zero”, twelve Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers.

US airstrikes sank three Japanese carriers and the main body she was part of was ordered to join the Kido Butai as fast as possible, an order soon cancelled in the evening. On this 5 June, her combat air patrol was still in the air while darkness fell. They spotted and drove off a single PBY Catalina in reconnaissance (VP-44), which had the time to report their position.

IJN Zuihō was therefore ordereded to prepare an airstrike with Nisshin’s own air group, on the US carriers supposedly in hot pursuing. However this order was rescinded too on the morning of 7 June after reports there was no pursuit. She sailed back to Sasebo, and was refitted in July–August 1942, before beig reassigned to the First Carrier Division, with the Shōkaku-Zuikaku Division, on 12 August, complementing their depleted air groups.

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

This division sailed to Truk on 1 October 1942, in support of the Guadalcanal Campaign. They departed on the 11t, based on IJA assuranced they would capture Henderson Field in between. Zuihō’s air group was now modernized, with eighteen A6Ms, six B5Ns. She was mostly charged or providing the CAP, while the Zuikaku class were tasked of the main strike. Both Japanese and American carrier forces found each others in the early morning of 26 October. This trigerred the start of the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, all carriers launching airstrikes.

Her air group crossed the path of those of USS Enterprise, the nine Zeros shooting down three Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters and three Grumman TBF Avenger. They also damaged one more of each, traded for four losses. Two Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers, used as bomb-armed armed scouts spotted and attacked Zuihō, scoring two 500-pound (230 kg) bomb hits on her flight deck, putting it ablaze. Meanwhile the rest of the fleet launched its first and second waves on the American carriers. Fortunately the bombs detonation were on deck, they did not penetrated so Zuiho was still repairable and retreated with the also damaged Shōkaku, to Truk, which they reached on 3 October. After temporary repairs, they both sailed to Japan. Zuihō’s repairs were completed on 16 December 1942 and Captain Bunjiro Yamaguchi took command during this period.

1943-44 Operations

Battle of the Philippines

Leaving Kure (17 January 1943) for Truk with additional aircraft parked on deck, she was assigned to the Second Carrier Division with Jun’yō and Zuikaku, providing cover for the evacuation of Guadalcanal. Zuihō’s fighters taxiied for Wewak in New Guinea by mid-February, others to Kavieng in March while Zuiho returned to Truk. Her additional air group then went to Rabaul (mid-March) for Operation I-Go against the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. These fighters brough by Zuiho claimed 18 kills.

Zuihō soon sailed back to Sasebo, Japan, on 9 May for a brief refit and was back to Truk on 15 July, remaining there until 5 November before another refit in Yokosuka. She received ha late air group, 18 Zeros and 8 Aichi D3A “Val”, proceeding to Kavieng by late August and the Truk in September, assigned to the First Carrier Division (also Shōkaku, Zuikaku). They proceeded to Eniwetok Atoll (18 September) for training and be ready to intercept American carriers attack near Wake or the Marshall Islands.

IJN report failed to catch the raid on the Gilbert Islands as the 1st Division was gone, off Eniwetok on 20 September when it happened. Reports pointed to another attack on the Wake-Marshall by mid-October, so Admiral Mineichi Koga scrambled the Combined Fleet on 17 October, reaching Eniwetok and waiting for further reports, until the 23th. They proceeded to Wake Island for a sweep, before folding back to Truk on 26 October. Zuihō’s air group was transferred to Rabaul this month, and they defended Rabaul a few days later, fighters claiming 25 enemies, traded for eight planes. Survivors flew back to Truk.

On 30 November 1943 Zuihō, Chūyō, Unyō, departed Truk for home with four destroyers, but since IJN naval codes had been cracked, several USN subs were posted along the way to Yokosuka. USS Skate torpedoed, but missed Zuihō on 30 November, Sailfish however sank IJN Chūyō on 5 December. Until May 1944, Zuihō mostly ferried aircraft and supplies to Truk and Guam. She was reassigned to the Third Carrier Division from January 1944, with the two Chitose class. They carried the 653rd consolidated air group, spread over all three carriers (18 A6M5 Zero fighters, 45 Zero A6M2 fighter-bombers, 18 B5N-2s “Kate” TBs, 9 Nakajima B6N “Jill” TBs) by May 1944. Their pilots were rookies in majority. They left Tawi-Tawi on 11 May (Philippines) for Borneo, resupplying in these oild fields, proceeding next to the Palau and western Carolines. American submarines were well present there, roaming in the area.

Battle of the Philippine Sea

The 1st Mobile Fleet headed to Guimares Island on 13 June for carrier operations training, much needed, until Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa learned about a Carrier strike on the Mariana Islands and he refueled to sail immediately to combat. Task Force 58 spotted them underway on 18 June, but lost contact as Ozawa skillfully turned south, eventually launching his airstrikes. His carried adopted a “T” shaped formation, with Third Carrier Division at the end (with Zuiho), 115 nautical miles ahead of the 1st and 2nd CarDivs (crossbar). Zuihō was supposed to act as bait and was as intended soon under attack.

Heavy cruisers deployed a spotting curtain of Sixteen Aichi E13A floatplanes at 04:30 while CarDiv 3 carriers launched 13 B5Ns at 05:20. At last, four carriers from Task Force 58 were reported at 07:34 and around 8h30 the second wave was launched, 43 A6M2 Zero fighter-bombers, 7 B6Ns, plus 14 A6M5 fighters, keeping a token air group of nine planes for self-defense. Later TF 58’s battleships were also spotted and, fatefully, the airstrike was diverted to them. Ddetected by radar at 09:59, the carriers launched no less than 199 Hellcats when in range. This was the famous “turkey shoot”, leaving just 21 IJN planes survive (for 3 Hellcats lost).

At dusk, the fleet turned to the northwest to regroup and refuel, while TF58 closed the distance. On 14 June, recce flotplanes were launched to try to spot the US TF, Zuihō also launching three aircraft at 12:00, east of the fleet. The Japanese were spotted first and Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher ordered an airstrike, which quickly sank IJN Hiyō, damaging two others. Zuihō escaped and disengaged in the evening, being home on 1 July, and staying there until October. She had notably to receive a new air group, again with young trainees.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

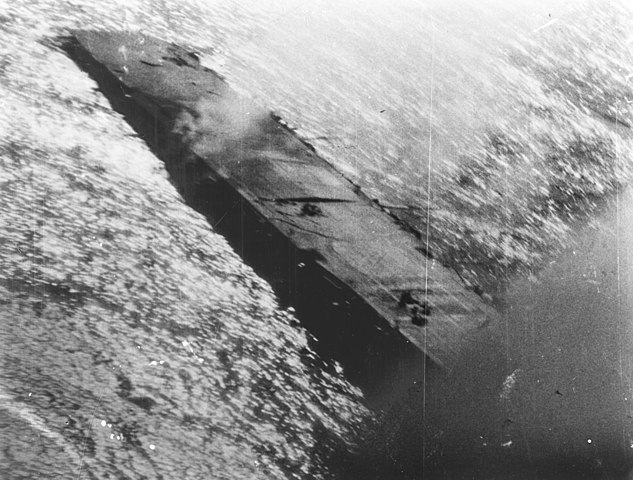

Zuiho sinking, 24 October 1944

The final chapter saw Zuiho, after months of inactivity, receiving her new air group and proceed under orders of Admiral Soemu Toyoda to be part of the Shō-Gō 1 naval operation to reclaim the Philippines, Shō-Gō 2 to defend Formosa (Taiwan) and create a defensive line from the Ryukyu Islands to southern Kyushu, from 10 October. The 653rd Naval Air Group was sent to Formosa and Luzon, very few remaining for carrier operations. The air group was destroyed in the Philippines, leaving the carriers with a feeble air protection.

On 17 October, Toyoda ordered Zuihō and Ozawa’s carrier force to approach Leyte Gulf from the north, as a bait to draw out Halsey’s TF38. Meanwhile a pincer with capital shops and cruisers was made south and west, converging on the gulf on 25 October to destroy the US landing forces. The carriers were not completely devoid of aviation: They shared 116 aircraft between them: 52 A6M5, 28 A6M2, 7 D4Y “Judy”, 26 B6Ns, 4 B5Ns. On 24 October, morning, the northernmost TF 38 carriers were in range and ozawa launched an airstrike to catch their attention.

Like in previous engagements, this was hopeless, and between a hail of Hellcats and the iron wall of 5-in, 40 and 20 mm, the strike accomplished little. None ever passed the defending fighters and survivors landed on Luzon. The Japanese carrier force was spotted at 16:05, but Halsey decided that it was too late to mount an strike, but headed north nevertheless, to launch one the following day. What followed was the Battle off Cape Engaño.

A single Aircraft from USS Independence launched at dusk spotted Ozawa during the night, and keep contact with him all night long, until Halsey ordered an airstrike at dawn (60 Hellcats, 65 Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, 55 Avengers. They were spotted at 07:35. The remaining 13 CAP Zeros were soon shot down, leaving the carriers alone. Zuihō tried launch her remaining aircraft when she was hit by a single bomb on her aft flight deck, after many Avengers misses. This 500-pound ordnance did not penetrated but started fires on the rear elevator and bulged the flight deck. The steering was stuck and she started listing to port. 20 minutes later fires were mastered and the steering repair, list corrected. She remained operational after this first wave.

The second wave focused on Chiyoda, but the third wave, circa 13:00 this time targeted Zuiho. She took a torpedo hit and two small bombs, plus 67 near misses. Shrapnels from the latter did most of the damage: They cut steam pipes, flooding both engine rooms, speed falling to 12 knots, while all available hands were manned the pumps from 14:10. She listed to 13° starboard until being dead in the water (14:45), a perfect exercize target when the fourth wave arrived at 14:55. Yet again, she was only near-misses ten times, while her list took 23°. Captain www ordered to abandon ship at 15:10. Zuihō capsized and sank a mere 15 minutes afterwards, at 15:26, carrying with her 7 officers and 208 men. Survivors (58 officers and 701 men) ere picked up and evacuated by the destroyer IJN Kuwa and battleship Ise.

IJN Shoho career

IJN Shoho on trials

While fitting-out, Shōhō was aqssigned to the Fourth Carrier Division, 1st Air Fleet on 22 December 1941. After commission, she departed with Zuiho and eight battleships in cover for the return of the 1st Air Fleet from Pearl Harbor and remained in Japanese waters until June 1942. On 4 February 1942, she ferried aircraft to Truk and stayed there until 11 April 1942, returning to Yokosuka afterwards. By late April she was assigned to Operation MO (the attack on port Moresby) and is sent to Truk on 29 April. She departed with four heavy cruisers as the Main Force of the operation, Yamamoto staying as cover with the force of battleship. Aircraft shortages meant her complement comprised four old A5M “Claude” and eight A6M2 “Zero”, six B5N2 “Kate”, so 18 out of a normal complement of 30. She was to cover notably Shōkaku and Zuikaku.

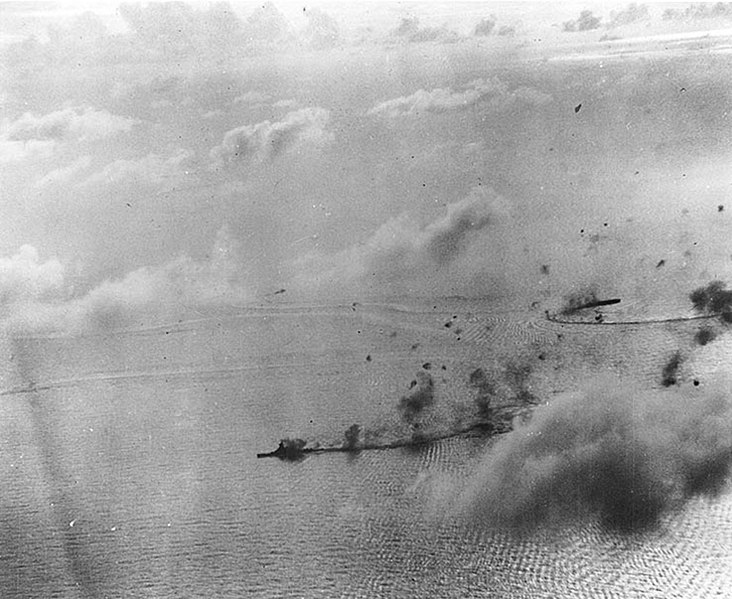

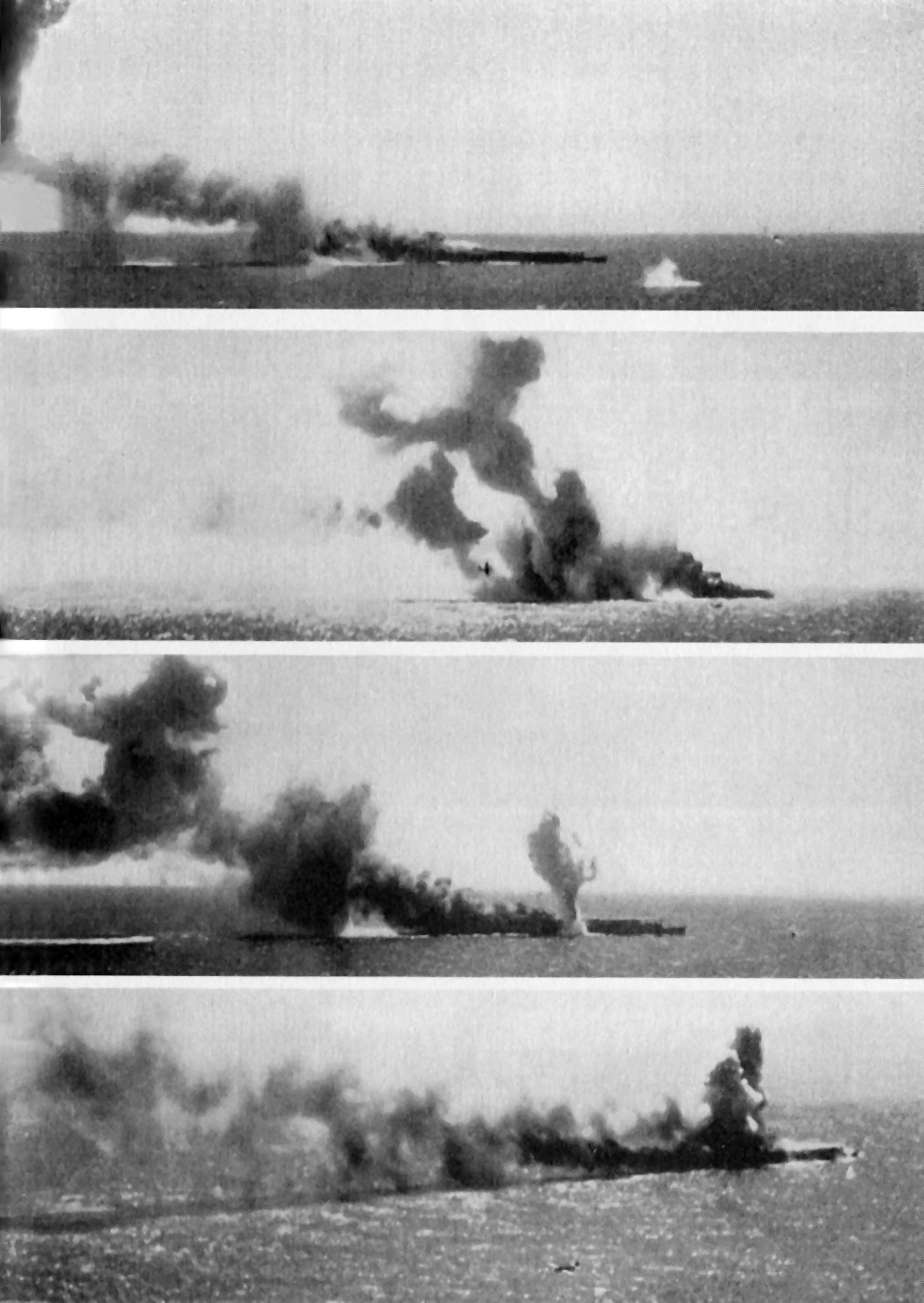

She covered the landings on Tulagi (3 May) and sailed northwards to cover the invasion convoy, hearing en route about USS Yorktown air group attack on Japanese shipping at Tulagi, confirming their relative position, but not precise location. Reconnaissance aircraft took off without result, but meanshile USAAF planes spotted Shōhō southwest of Bougainville (5 May). She was out of range as US carriers were refueling. Rear Admiral Fletcher received intel about the relative location of three Japanese carriers known for Operation MO, near Bougainville. It prediced main operations to start on 10 May and after a complete refueling hos force departed on 6 May, sailing for the eastern tip of New Guinea, ready for an ambush on 7 May.

US recce aircraft reported two Japanese heavy cruisers, northeast of Misima Island (Louisiade Archipelago), eastern tip of New Guinea on the moprning as well as two carriers on hour later and a further later, Fletcher ordered an airstrike, beleaving these were Shōkaku and Zuikaku. Lexington and Yorktown launched in common 53 SBD dive bombers, 22 TBD torpedo bombers, escorted by 18 F4F Wildcats. However the last report proved to have been miscoded, whereas i the meantile a new report from an USAAF aircraft identified Shōhō with her escorts and the invasion convoy en route, 30 nautical miles (56 km; 35 mi) away from the previously reported position, communicated to the USN air strike en route. Thus, Fletcher’ fury was now redirected on Shōhō.

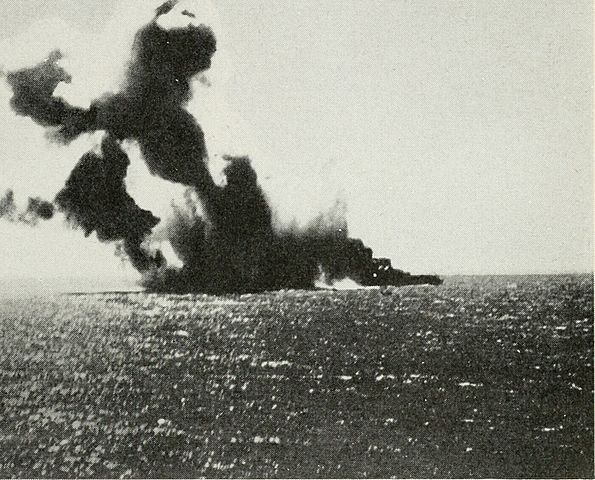

Their position was further confirmed by an aircraft from USS Lexington at 10:40 and Shōhō’s combat air patrol was in the air (two A5Ms, one A6M Zero). The still rookie USN pilots arrived, and the SBD took their diving pattern approach, then followed in échelon, but all missed as Shōhō’s captain manoeuvered hard rudder. This was the first dive bomber attack through, and the CAP shot down one Dauntless. The second SBD attack followed, this time, managing to hit Shōhō twice with 1,000-pound ordnance that penetrated her flight deck, bursting inside. There, between fueled and armed aircraft on fire and ruptured fuel lines, the hangar became an inferno.

A minute later VT-2 torpedo bombers arrived. Thie was the Devastator’s finest hour in the whole of WW2 (At midway they were first, drawing the CAP on them, and decimated in the process). They dropped their torpedoes in pincer as planned, to avoid evading manoeuvers to succeed and made five hits in quick succession. Their blast was sufficient to knock out the aicraft carrier’s steering and power, flooded the engine and boiler rooms, so rapidly bleeding out her speed.

The coup de grace was given by Yorktown’s air group’s SBD, which made their dive in turn: This time, the more experienced pilots had no CAP to oppose them, as they were shot down by the Wildcats in between. They managed to make perfectly coordinated dives “by the book” on a slowed down Shōhō to a crawl, making eleven hits, all with 1000-pound bombs. Remaining TBDs from Yorktown also managed to make two more torpedo hits. Lieutenant Commander Robert E. Dixon (VS-2) famously radioed “Scratch one flat top!”.

Shōhō was abandoned at 11:31, sinking four minutes later, leaving 300 survivors stranded into the sea without help for many hours as the Main Force escaped north at high speed. Only at around 14:00, IJN Sazanami, a destroyer, returned to rescue 203 survivors, with around 1/3 died by exhaustion, wounds, or sharks. IJN Shōhō was the first Japanese aircraft carrier lost in WW2, a considerable morale boost for the US. As customary for the Japanese, the announcement was made much later, kept hidden for a long time, survivors being spread into other crews and not sent home.

IJN Carrier division 3 under attack

Battle of the Coral sea, May 1942

Shoho under attack

Sources/ Read more

Books

Conway’s all the worlds fighting ships 1922-1947

Brown, David (1977). WWII Fact Files: Aircraft Carriers. New York: Arco Publishing.

Brown, J. D. (2009). Carrier Operations in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Hata, Ikuhiko; Yasuho, Izawa & Shores, Christopher (2011). Japanese Naval Air Force Fighter Units and Their Aces 1932–1945.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland

Parshall, Jonathan & Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books.

Peattie, Mark (2001). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power 1909–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Polmar, Norman & Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. Potomac Books.

Tully, Anthony P. (2007). “IJN Zuiho: Tabular Record of Movement”. Kido Butai. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

Stille, Mark (2005). Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carriers 1921–1945. New Vanguard. Vol. 109. Osprey Publishing

Stille, Mark (2007). USN Carriers vs IJN Carriers: The Pacific 1942. Duel. Vol. 6. Osprey

Links

On globalsecurity.org

On militaryfactory.com

On ww2db.com

On combinedfleet.com

aviation-history.com: Coral Sea

j-ships.com – Zuiho study

IJA operations in the South Pacific Area Translated by Steven Bullard

IJN Aces and fighter units in WW2

shattered sword, Midway

Japan Center for Asian Historical Records

combinedfleet.com tabular record of movement; zuiho

combinedfleet.com tabular record of movement: shoho

3D & Model kits

wow’s Zuiho

wow’s Zuiho

Videos

The model’s corner

Zuiho class on scalemates

Hasegawa, Fujimi, Aoshima 1:700 and a 1:3000 for a Coral Sea diorama by Fujimi.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign