United Kingdom (launched 1909) Dreadnought Battleship (service 1911-1921)

United Kingdom (launched 1909) Dreadnought Battleship (service 1911-1921)WW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

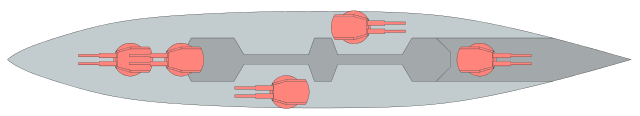

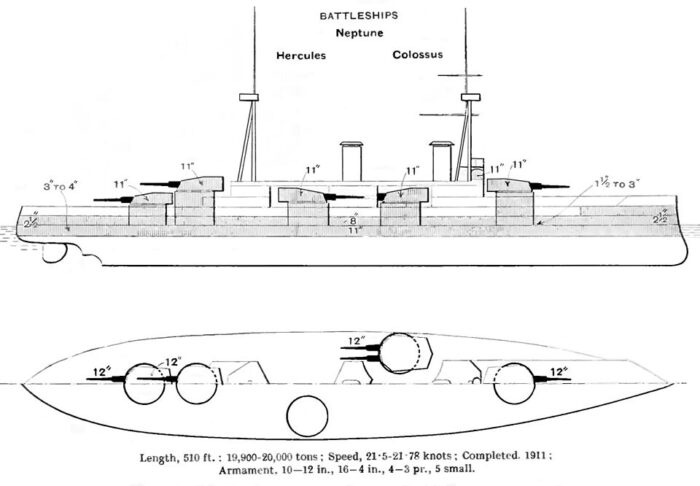

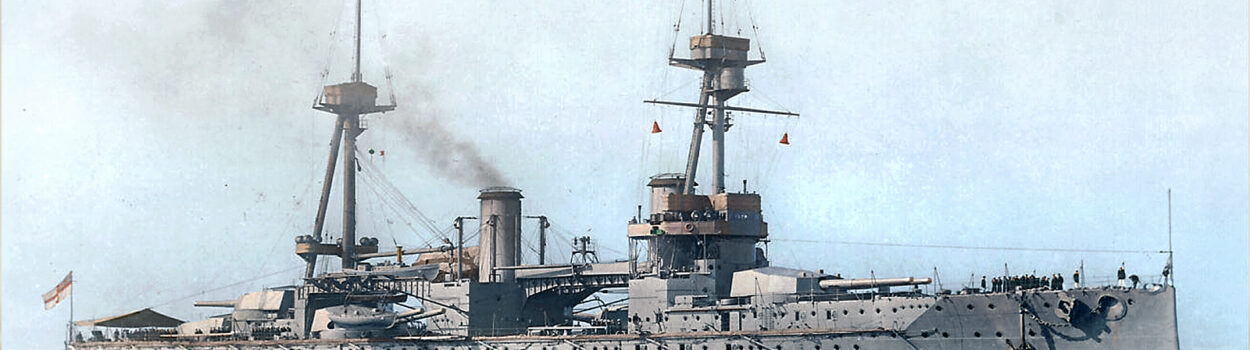

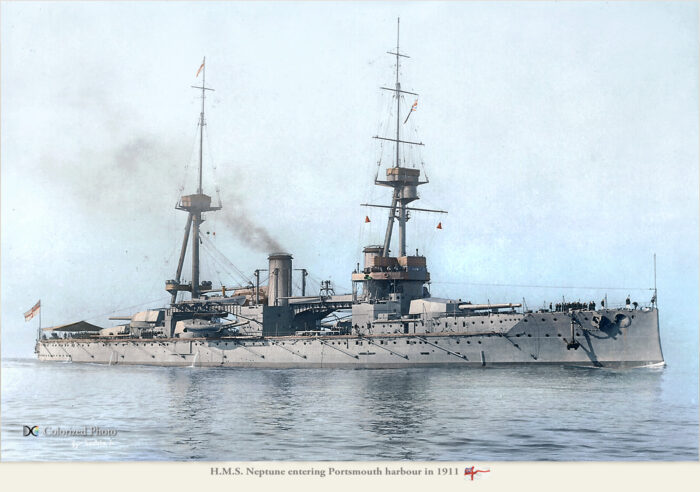

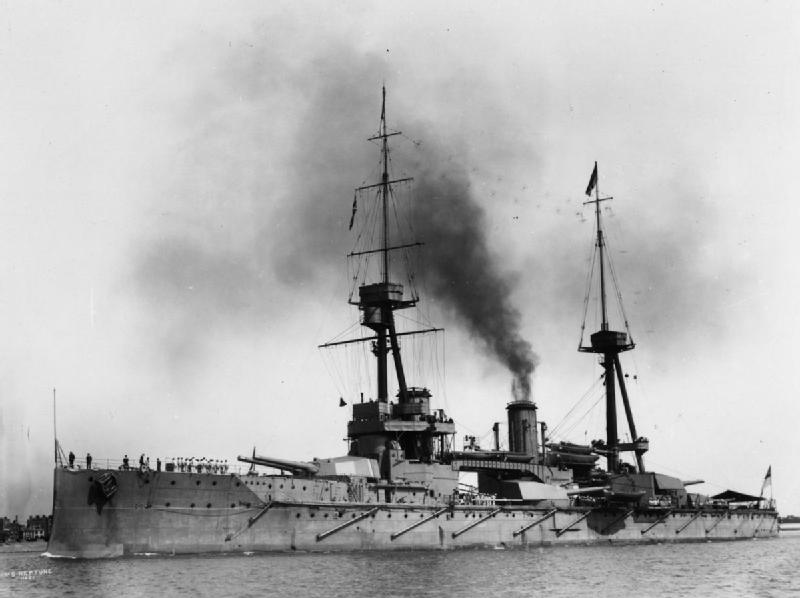

HMS Neptune was a figurehead of a new class of dreadnoughts, but the two others were so heavily modified that they ended in their own class, the Colossus. The main difference resided in the artillery disposition, with two wing turrets staggered en echelon in order that all could fire in broadside. However, this was only in theory, as blast damage to the superstructure and boats for each volley limited angles. The other improvement concerned super firing aft turrets. On the previous series, both were at the deck level. This allowed all four turrets to fire in retreat. Neptune, built at HM Dockyard, Portsmouth, became the first Royal Navy ship to have this disposition, but there was a catch: The upper turret could damage the lower turret’s sighting hoods when traversing within 30 degrees of the stern. Neptune also introduced the first director gun-control, heavily tested in trials and subsequently adopted on all following British dreadnought. She was part of the 1st Battle Squadron, Grand Fleet when in August 1914, taking part in the Battle of Jutland by May 1916, and the inconclusive action of 19 August. Months later, her service generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea. She was deemed obsolete postwar and was reduced to reserve, sold in 1922 and BU.

From Wings to Echelon turrets

Development

After the launch of Dreadnought in 1906, there was a naval arms race that pushed Germany to accelerate its naval construction plans. The British Admiralty intelligence believed Germany could only built four modern capital ships, to be commissioned by 1910. In the meantime, Royal Navy could secure eleven and keep a clear head. The first seven dreadnoughts were a repeat of HMS Dreadnought to gain time. For the next ones, the admiralty proposed the construction of only a single battleship and a battlecruiser as per the 1908–1909 naval budget. They were submitted to the government in December. The Liberals however reduced military expenditure, increased social welfare spending, so £1,340,000 was planned to be axed, which was below the previous year’s budget. PM Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman was briefed by February 1908 however and many were persuaded to wait before the decision. Debates raged over the budget in March. The current Government was accused to be too complacent about the superiority of the Royal Navy over the Imperial German Navy. In the end, H. H. Asquith, Chancellor of the Exchequer, replaced Campbell-Bannerman as Prime Minister and announced that the government was prepared to build as many dreadnoughts as required to prevent any catching-up from Germany for the end of 1911.

Once finances were secured, the next battleship was determined to be named the Neptune class, to continue with antique references. At first the admiralty proposed an improved version of the St Vincent class, only with additional armour and armament, all rearranged for a greater efficiency overall. So after some extra discussions and seeing what was done overseas at the time, her gun turret layout was decided against the classic Dreadnought formula and if wing turrets were retained, they were now staggered “en echelon”.

This arrangement was an answer to the frustration that all turrets could not fire a broadside, one was always on the wrong side. The solution of staggered turrets was already tried and tested since the late 1870s. This allowed to have both placed amidship, still on the wings, but one was further forward than the other. Seen from the side, they seemed to be dangerously close together, but in reality the beam created some room between them, and they could fire, crucially, a broadside, with the opposite turret dangerously however firing across the deck, so the crew needed to be warned and everything prepared. This alternative to axial turrets was used when the latter were larger and heavier than usual, going on par with the evolution of naval artillery, and to keep balance.

The unique arrangement of Neptune, repeated on the next Colossus class.

By retaking this older configuration, but with much more modern 12-inches guns, all five turrets now could shoot on the broadside, but in practice, blast damage to the superstructure and boats made this impractical, except in an emergency. In the US indeed, development led rapidly to a 10-gun broadside on the Delaware class, all-centreline. This configuration eliminated blast problems resulting to fire across deck, and proved the “en echelon” arrangement was a dead end. Having that many turrets, in that case, five, meant a longer hull, if not placed in superfiring positions, which for stability and loading issue was not preferred by the admiralty, yet. But ultimately this was the obvious path that was chosen. Rapidly, the Italians showed triple turrets were possible, and the Austro-Hungarians went even further and brought these in superfiring positions. An extra mile that was considered too dangerous for stability, but which was forced by antiquated, restricted dockyards.

HMS Neptune was also the first British dreadnought with superfiring turrets. Indeed, this effort allowed to shorten the ship, reduce costs. The Minas gerais and Rio de Janeiro class for Brazil followed suit, and went further with forward aft superfiring turrets, and then amidship turrets en echelon. To further save length (which meant less armour, less output) the boats were installed on girders over the two wing turrets. The drawback in the arrangement was obvious: When firing, these girders were damaged, could fall onto the turrets and even potentially jam them. This system was never reused. The bridge also had an odd position, being located above the conning tower, it had a better view but in case of damage, could collapse over and obscure it. In the end, the staggered or en echelon turret solution was a short design fad. Only the RN and Kaiserliches Marine (Kaiser class) tested that one-time configuration.

Brassey’s and other publications diagrams

Design of the class

Hull and general design

Neptune measured overall 546 feet (166.4 m), for a beam of 85 feet (25.9 m), and deep draught of 28 feet 6 inches (8.7 m). She displaced 19,680 long tons (20,000 t) at normal load, 23,123 long tons (23,494 t) at deep load. She had a metacentric height of 6.5 feet (2 m) at deep load. Her crew reached 756 officers and ratings as she was completed. However, it grew to 813 in 1914.

As for the design went, many points were comparable to the previous St. Vincent class.

They had the same ram bow same refined entry lines and large aft section, massive cutouts around the forecastle for the staggered turrets, “three islands” as far as superstructures went, with a narrow bridge with tripod mast (rear legs like on the St. Vincent) and fire funnel, tall bridge above the CT as said, a spotting and fire director atop, forward searchlight platform, composite mast above supporting wireless radio cables, a central “island” with the amidship funnel and extra platforms, plus aerial girders to support the boats (a dozen of all types) and the third “island” with an aft tripod mast, spotting top, and the rear deck turret superfiring X-Y. Unlike the St. Vincent and Dreadnought, Neptune also introduced a secondary armament, with 4 inches or 102 mm anti-torpedo boat guns, more efficient than the puny 3-inches (76 mm) guns.

Powerplant

Neptune was powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines. They were each housed inside their own separate engine room. The outer propeller shafts were driven by the high-pressure turbines. They were further exhausted into low-pressure turbines, driving the inner shafts used for cruising. These turbines were fed by eighteen Yarrow boilers at a working pressure of 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2), also in four separated boiler rooms. This ensemble was rated for an output of 25,000 shaft horsepower (19,000 kW). Neptune thus was capable of maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). She carried 2,710 long tons (2,753 t) of coal and an extra 790 long tons (803 t) of fuel oil in normal conditions. The latter was sprayed on coal to increase the burn rate. Range was 6,330 nautical miles (11,720 km; 7,280 mi), with a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

Protection

Main belt: 254mm (10 inches) (tapering to 203mm (8 inches) at the lower edge) between “A” and “Y” barbettes, tapered to 178mm (7 inches) forward and down to 64mm (2.5 inches) for the last 10 meters (32 ft). Tapered to 64mm (2.5 in) between “Y” barbette and the stern. Belt height 2.08m (6-1/2 ft). The main belt was in Krupp cemented armour.

Upper belt: 203mm (8 inches).

Transverse Bulkheads, fore 127mm (5 inches) and aft 203mm (8 inches).

Secondary fore upper bulkhead closing the 7 in belt of 4-5 in (102-127mm).

Main deck: 32mm (1.25 in) between barbettes, 44mm (1.73 in) middle deck with same thickness slopes to enclose the citadel.

Lower deck: 76mm (3 inches) aft barbette “Y”. 38mm (1.5 in) forward from barbette “A”.

After torpedo control tower: 3-in sides, 2-in roof.

Longitudinal anti-torpedo bulkheads: 1-3 inches (25 to 76 mm)

Main turrets: 280mm (11 in) face, 203mm (8 in) sides and rear, 76mm (3 in) roofs.

Main “A”, “X”, “Y” barbettes: 229 mm (9 inches) over main deck, 127mm (5 inches) under main deck.

Staggered Barbettes “P” and “Q” 254mm thick (10 inches) outer faces.

Funnel uptakes: 25mm (1 inch) splinter protection (first British battleship with these).

Conning Tower: 280mm (11 inches) face and sides.

Armament

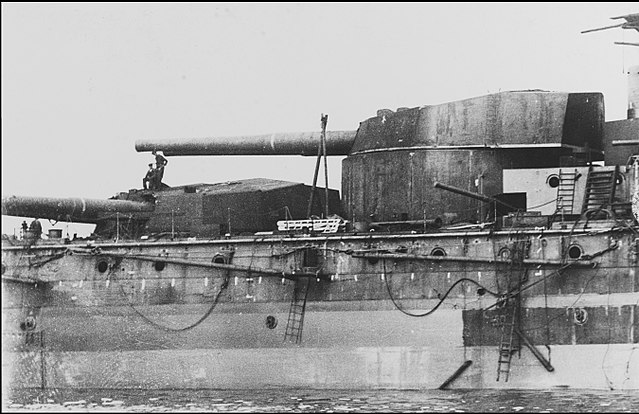

Neptune’s aft X-Y turrets

BL 12-inch/50 Mark XI

Her ten 50-calibre breech-loading (BL) 12-inch (305 mm) Mark XI guns were brand new, introduced in 1910 as Neptune was completing. They were an attempt to improve the performances in armour-piercing capability and range of the Dreadnought’s main guns and successor, going from 45 to 50 calibre, and were introduced on the previous St. Vincent class. They were also adopted by the Colossus class, last armed with 12-in guns.

Furthermore, they were mounted in five hydraulically powered twin-gun turrets, three along the centreline (A, X-Y) and the remaining two as staggered wing turrets (P-Q). Maximum elevation was +20° for a range of 21,200 yards (19,385 m). They fired a 850-pound (386 kg) shell at 2,825 ft/s (861 m/s). Rate of fire was two per minute. 100 shells per gun were carried, for a total of 1,000, mixing AP and HE (mostly AP). More on navweaps.

BL 4-inch (102 mm)/50 Mark VII

The great novelty of the design was the introduction of a real secondary armament, in replacement of the 3-in guns of previous battleships. These sixteen 50-calibre BL 4-inch Mark VII guns were placed in unshielded single mounts, all in the superstructure. For example, the “bridge block” house three on either side alone. This addressed the problems of turret-roof guns, used in earlier battleships. They were difficult to work when the main turrets below were traversing or when replenishing ammunition. They were exposed to shrapnel, and could not be centrally controlled to coordinate fire. The 4-inches had maximum elevation of +15° for a range of 11,400 yd (10,424 m) with a 31-pound (14.1 kg) HE shell at 2,821 ft/s (860 m/s). 150 rounds were provided per gun. This was completed by four QF 3-pounder (1.9 in (47 mm)) Hotchkiss as saluting guns.

Torpedo Tubes

As all previous designs and the next, Neptune carried torpedo tubes, in that case three submerged 18-inch (450 mm): One on each broadside, another in the stern (later removed) with a total of 18 torpedoes provided.

Main weaponry.

Fire Control

A great novelty of the design was the introduction of a modern fire control. Control positions for the main armament were in the spotting tops, fore and mainmasts. Data from a nine-foot (2.7 m) Barr and Stroud coincidence rangefinder on each of these fed a Dumaresq mechanical computer, being electrically transmitted then to Vickers range clocks in the transmitting station located beneath each position on the main deck. There, they were converted into elevation and deflection data, displayed mechanically in each turret. The target’s data was graphically recorded on a plotting table also for the gunnery officer, helping him to predict the target moves. The turrets as well as the transmitting stations and control positions could be connected in almost in all sorts of combination.

Neptune introduced a gunnery director, experimental still, and designed by Vice-Admiral Sir Percy Scott. Located on the foremast underneath the spotting top, it electrically provided data to the turrets via a dial pointer. Each turret officer followed it in action. The director layer fired the guns simultaneously also to help to spot shell splashes, minimising effects of roll on dispersion. This early director was replaced by the final one in 1913, installed in May 1916. She also had additional 9-foot rangefinders protected by armoured hoods for each gun turret, installed as the war started in late 1914. This was rounded up by Mark I Dreyer Fire-control Tables in early 1916, located in each transmission station, combining functions of the Dumaresq and range clock.

Modifications

In 1912 her fore funnel was raised. In 1914 her forward flying bridge and associated girders were removed. In 1915 had stern torpedo tube was removed. By 1916 a clinker screen was added to her the fore funnel. The extra 102mm guns were enclosed by light steel structures, and the aft fire control platform was removed. In 1917 two extra 3-inches/45 20cwt QF Mk.I were added for AA protection.

In 1917-18 her appearance changed indeed considerably: The forward girders were removed, the masts were truncated down to the platforms on top of the tripods, the aft spotting top was removed, and the fore spotting top transformed into a fully fledged fire control station. The fore funnel received a smoke deflection cap, and the bridge was further developed.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 19,680 long tons (20,000 t) normal |

| Dimensions | 546 x 85 x 28 ft 6 in (166.4 x 25.9 x 8.7 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts, 2 Parsons turbine, 18 Yarrow boilers: 25,000 shp (19,000 kW) |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,330 nmi (11,720 km; 7,280 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 5×2 12-inch (305 mm), 16× 4-in (102 mm), 3× 18-in (450 mm) TTs |

| Protection | Belt 8–10 in, Bulkheads 5-8 in, Deck 1.25–3 in, CT 11 in, Turrets 11 in, barbettes 5–10 in |

| Fire Control | See notes |

| Crew | 756–813 (1914) |

Service life

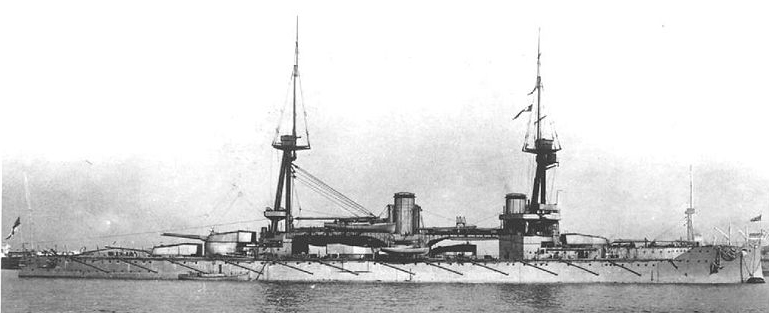

HMS Neptune 1911

In Short:

The HMS Neptune was ordered in 1908, laid down at Portsmouth Dockyard in 19 January 1909 and launched on 30 September 1909, and eventually commissioned on 11 January 1911 under Captain Vivian Bernard in command throughout her career. She was flagship of the Home Fleet May 1911-May 1912 and then was transferred to the 1st Battle Squadron, remaining there until June 1916, after the Battle of Jutland (She took part in the Battle of Jutland as part of Admiral Jellicoe’s Battle Fleet, credited with some hits on the German battlecruiser Lützow). In April 1916 she was rammed by accident SS Needvaal but did not deplore any serious damage.

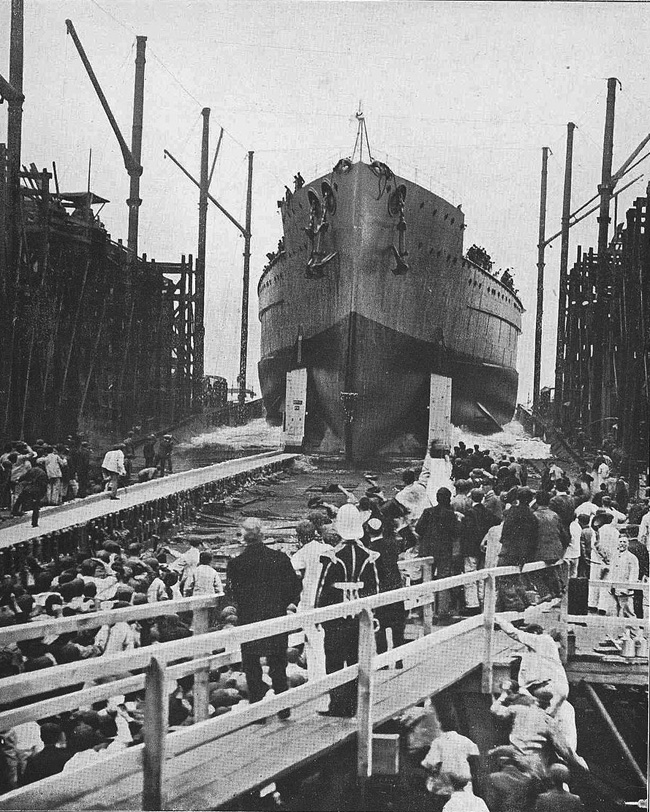

Launch of HMS Neptune at Portsmouth NyD.

Neptune (Roman god of the sea) was ordered on 14 December 1908, laid down at HM Dockyard in Portsmouth on 19 January 1909, launched on 30 September and completed in January 1911, for a cost of £1,668,916, including armament. Commissioned on 19 January, she started her trials with the Scott’s experimental gunnery director until 11 March. They were assisted by Rear-Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Atlantic Fleet. Neptune relieved Dreadnought as flagship of the Home Fleet, 1st Division from 25 March onwards. She was presented in full regalia at the Coronation Fleet Review in Spithead on 24 June. On 1 May 1912, the 1st Division became the “1st Battle Squadron”. Neptune was relieved as flagship on 22 June but took part in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July, still at Spithead. Neptune was privatized on 10 March 1914 instead of Iron Duke as flagship of the Home Fleet.

On 17-20 July 1914, Neptune was present at a test mobilisation and fleet review (July Crisis). She was sent at Portland on 27 July, and proceeded with the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow on the 29th, to safeguard the fleet from a German surprise attack there by the northern route. In August 1914 now part of the Grand Fleet under command of Admiral Jellicoe she was based at Lough Swilly in Ireland, while defences at Scapa were strengthened. On 22 November, she made a first sweep in the southern North Sea. She was in distant support for David Beatty’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron in several operations, starting with this one, ended in Scapa Flow by 27 November. She started a refit on 11 December.

She returned into service on 23 January 1915, again in distant support of Beatty’s battlecruisers, only hearing about the Battle of Dogger Bank. On 7–10 March, she was in a sweep in the northern North Sea and training manoeuvres. Same for 16–19 March. While on her way back, she was ambushed and torpedoed, but missed, by SM U-29. While manoeuvring for another attack, she was spotted and Neptune veered hard to present her bow and attempt a ramming. She succeeded, managed to cut her in half. U-29 was lost with all hands. On 11 April, she was part of a patrol in the central North Sea and back on 14 April, then the same on 17–19 April, and off the Shetlands on 20–21 April.

Next were sweeps into the central North Sea, 17–19 May and 29–31 May. On 11–14 June, she took part in gunnery and battle drills west of the Shetlands. On 2–5 September she made a sweep in the northern the North Sea, plus gunnery drills, and more training exercises. She was part of the North Sea sweep of 13-15 October. Three weeks later, she took part in another fleet training, west of Orkney on 2–5 November. She was part of the sweep on 26 February 1916, this time with the Harwich Force in the Heligoland Bight, marred by bad weather. Same on 6 March, again frustrated by terrible weather conditions for destroyers. On 25 March, she sailed in support of Beatty for the raid on Tondern. On 26 March, the battle was already out when she arrived, as both forces disengaged in a strong gale. On 21 April, she took part in the diversionary action of Horns Reef to leave the Russians performing a mine laying mission.

On 22/23 April, Neptune was accidentally rammed by the SS Needvaal in thick fog, only lightly damaged. She refuelled at Scapa Flow on 24 April and sallied again in response to the raid on Lowestoft, but arrived too late. On 2–4 May, she repeated the diversionary action off Horns Reef to keep German attention out of the Baltic.

On 22/23 April, Neptune was accidentally rammed by the SS Needvaal in thick fog, only lightly damaged. She refuelled at Scapa Flow on 24 April and sallied again in response to the raid on Lowestoft, but arrived too late. On 2–4 May, she repeated the diversionary action off Horns Reef to keep German attention out of the Baltic.

Next came her greatest test, the Battle of Jutland.

British intel (room 40) knew the Hotchseeflotte departed in force, to the Jade Bight on 31 May 1916 to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet. RADM Franz Von Hipper’s five battlecruisers were in vanguard. The Grand Fleet (28 dreadnoughts, 9 battlecruisers in vanguard) sortied the night before in an attempt to cut off and destroy the Hochseeflotte once and for all.

On 31 May, Neptune (Captain Vivian Bernard) was part of the 5th Division, 1st BS, 19th from the head. In the first stage of the general engagement she fired two salvos (main guns) at a silhouette at 18:40 jut before the fleet reversed course from 18:55. Neptune fired a salvo at the crippled SMS Wiesbaden. After a turn, she became one of the closest at 19:10, fired four salvos at SMS Derfflinger, claiming two hits. Later she fired at close range both her main and secondary guns at enemy destroyers but dodged three torpedoes. This was over for her. She had in total spend 48 main guns out of 1000, (21 high explosive and 27 common pointed, capped) plus 48 4-inch guns shells, without any confirmed hit.

HM King George V and Admiral Calaghan on HMS Neptune

Post battle, she was sent to the 4th Battle Squadron. She was part of the 18 August sortie to ambush the High Seas Fleet in the southern North Sea, but the interception failed due to communication mishaps. Two light cruisers were sunk by U-boats, prompting Jellicoe to ban any sortie 55° 30′ North, also fearing mines. Since the Grand Fleet would only make a sortie in case there was an attempted invasion of Britain or large scale engagement in suitable conditions, her last years in 1917-18 were pretty uneventful. Like other battleships, she became “hotel Neptune”.

On 22 April 1918, still, the German High Seas Fleet sailed north in attempt to catch a convoy to Norway, folded back after SMS Moltke suffered damage. The Grand Fleet sortied from Rosyth only on the 24th, it was too late. This was the last time to shine. Neptune was present at Rosyth for the German fleet surrender on 21 November. Placed in reserve on 1 February 1919 she was deemed obsolete, listed for disposal in March 1921, sold for scrap at Hughes Bolckow, by September 1922, towed to Blyth in Northumberland on 22 September and BU.

Read More

Books

Preston, Antony (1985). “Great Britain and Empire Forces”. In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921.

Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. London: Routledge.

Brooks, John (1995). “The Mast and Funnel Question: Fire-control Positions in British Dreadnoughts”. Roberts, John (ed.). Warship 1995.

Brooks, John (1996). “Percy Scott and the Director”. In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. Conway Maritime Press.

Brown, David K. (1999). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. NIP

Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. NIP

Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. NIP

Friedman, Norman (2015). The British Battleship 1906–1946. Barnsley, Seaforth Publishing.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations. Seaforth Publishing.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. NIP.

Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Creation, Development, Work. George H. Doran Com.

Marder, Arthur J. (2013) [1961]. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era 1904–1919. Vol. I, NIP.

Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. Random House.

Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank – 24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. III.

Monograph No. 29: Home Waters–Part IV.: From February to July 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. XIII.

Newbolt, Henry (1996) [1931]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. V.

Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament. NIP

Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. Galahad Books.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. Brockhampton Press.

Links

HMS Neptune on dreadnoughtproject.org

navypedia.org/ neptune class

The HMS Neptune on wikipedia

Gallery

Video

3D

https://www.turbosquid.com/3d-models/3d-hms-neptune-battleship/1138173

Model Kits

https://sdmodelmakers.blogspot.com/2015/03/234-1280-scale-hms-neptune-1909.html

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign