Derfflinger class battlecruisers

German Empire (1913-14) Battlecruisers S.M.S. Derfflinger, Lützow, Hindenburg

German Empire (1913-14) Battlecruisers S.M.S. Derfflinger, Lützow, Hindenburg

The last German Battlecruisers, Derfflinger, Lützow and eventually Hindenburg, were all operational during WWI. They were the pinnacle of this development in continental Europe, innovating in two ways: 30 cm main guns all in centerline turrets, and a flush-deck hull, among others. As the Seydlitz and Moltke clas they were planned as mixed battlecruisers to deal with regular battleships. With Tirpitz’s staunch support, they were defined in the fourth and final Naval Law as three dreadnoughts, for which Design work on SMS Derfflinger herselfstarted in October 1910. They would end slightly different, especially the last, SMS Hindenburg, eventually launched later on a modified design.

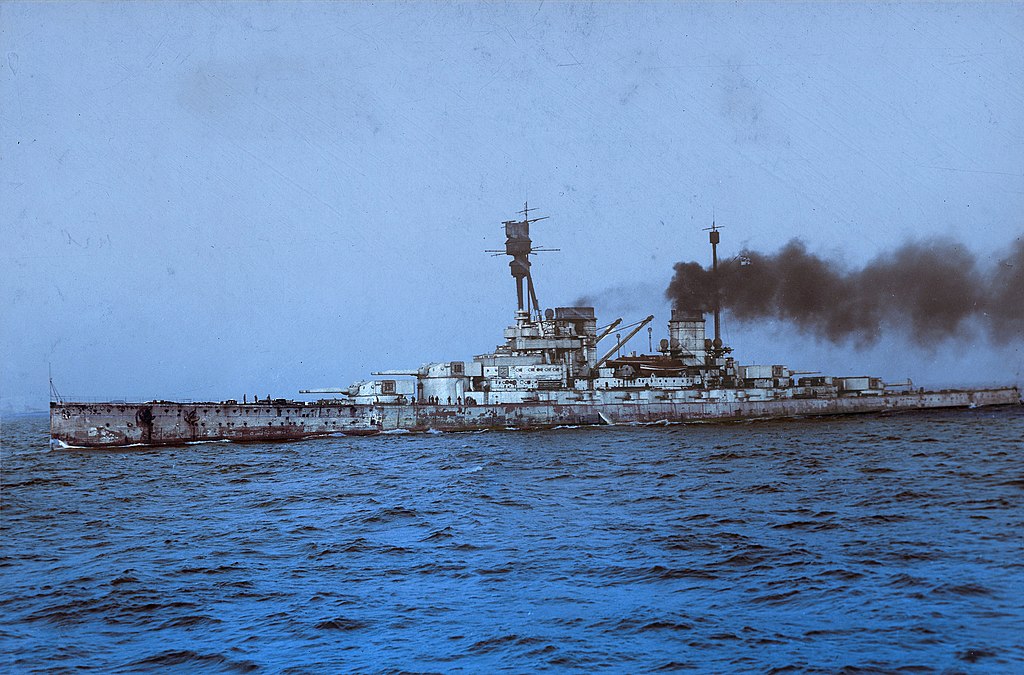

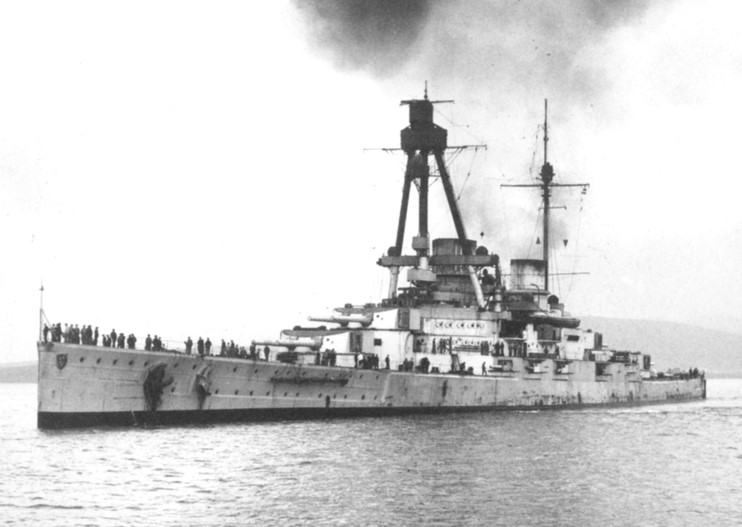

SMS Hindenburg, colorized by irootoko Jr

It resulted in a ship even further on the path of “fast battleships” rather than battlecruisers. It happen at a time admiral Jackie fisher advocated for his “Baltic battlecruisers”, very light and extremely fast, with super-heavy guns. A stark contrast, until a logical technical rapprochement with super-dreadnoughts. HMS Hood was perhaps the closest to what the Germans were building or planning at that point. Only the first two would see intense actions, Hindenburg being completed too late to be engaged in any significant actions as she was commissioned on 10 May 1917, to be scuttled like the others in June 1919, after a career of just two years. The next, the Mackensen class for the first time sported 38 cm guns, greater speed and protection, and really were the first german “fast battleships”.

Development history

Their origin is found in the fourth (final Naval Law) passed in 1912. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was keen to mobilize the press and his connections to mount a public outcry, over the British acting the way they did at Agadir (After the first Moroccan Crisis of 1905–06, France and Germany agreed on 9 February 1909 the former would retain political control, but the two would avoid tepping on each other’s economic interests in the country.

Germany’s move later tested the relationship between Britain and France, enforcing compensation claims to accept effective French control of Morocco. In short the Germans sent a gunboat (SMS Panther) in Agadir, replaced by the cruiser SMS Berlin. The British reacted by sending battleships to Morocco, and this was fully supported by France as part of the entente cordiale.

The crisis of 1911 suceeded to pressure the Reichstag to secured more funds to the Navy and in that fourth Naval Law added three new dreadnoughts, two light cruisers, as well as recruiting 15,000 more personal for the Navy. The three “capital ships”, still undefined, were reprecised by Tirpitz as battlecruisers, but still with this caracteristic duality, making them intermediate between battleships and battlecruisers in the British sense. They became the Derfflinger, Lützow, and Hindenburg. Design work started in October 1910, and went on until June 1911. It was soon decided to give SMS Hindenburg a slightly modified design and the completion of the design work was delayed. It was done between May and October 1912.

The navy department asked engineers to submit proposals to remedy problems found on the preceding battlecruiser like the Moltke class and Seydlitz, notably over propulsion, but moeover the main armament, which was still weak on paper compared to British battlecruisers. The four shaft arrangement was reduced to three as in battleships, as this would allow to use a cruising diesel engine for the central shaft and significantly improve their range. It would aslo eased refuelling operations, and reduce the crew needed in their machinery. The second point was perhaps more urgent, as it was about the use of a larger artillery than the usual 28-cm (11 in) used upt to that point (over arguments of standardization, development time, long range and quick firing), to 30.5 cm (12 in), to be at last able to compete with British designs armed with 15-in guns. But this was also caused by the confirmation the latest British battleships also had a main belt armor 300 mm thick (12 in).

Due to the dual nature of German battlecruisers, supposed to fight in batte line if need be, their armament needed to be able to defeat this protection. The turrets being larger, it was decided to reduced the overall weight by using less turrets, just four instead of five, and drop the echelon arrangement, which was not optimal, for an axial (centerline) arrangement, maximizing the arc of fire.

Moreover, two were forward and two aft, so to avoid the problems of previous admiship turrets stuck between funnels and superstructures. The superfiring solution seemed also obvious, but with a twist for the aft turret. Weight increases eventually was only 36 tons to the overall displacement. Tirpitz however, again, at first argued against this increase in gun caliber, but he was overruled, notably by the Kaiser himself.

The design of the hull also evolved in time, and engineers wanted to do the lightetst, yest strongest possible hull at the same time. It seems contradictory, but the new construction technique employed to save weight was to drop transverse steel frames entirely, and relying entirely on longitudinal ones (made strnger in the process). This enabled to retain the necessary structural strength at a lower weight and also easing a new hull design, still brand new for capital ships at the time: Dropping the forecastle entirely and create a flush-deck hull. The latter presented advantages, saving weight again notably, but it also made internal compatimentaion a bit more complicated. It coould also bee seen as a reaction to the two-stepped hull of the previous Seydlitz. The ASW protection was not very different than prevous designs, with outer hull spaces between the hull wall and torpedo bulkhead filled with coal, raising considerably the range in wartime.

On 1st September 1910, the design board adopted officially the German 30.5 cm (already developed for the Helgoland class back in 1908, but with a new improved moint and reload system). They were to be mounted in four twin turrets with a specific new design, mounted on the centerline. Overall the armor layout repeated the Seydlitz’s protection, adjusted for the flush deck hull. The German reaction to Agadir trigerred a new fear in the British medias, forcing the British Parliament to vote for more ships. Kaiser Wilhelm II in recation, wanted to reduced build time to two years each from keel laying to completion, and no longer three years, imposing drastic readjustments. This of course proved unfeasible, since both armor and armament could supply them on schedule anyway. In fact completion time was about two years and six month for the lead ship, but far more for the others, due to the war breaking out: Three for Lützow, and even four for Hindenburg, launched in August 1915 despite being laid down in October 1913.

Construction

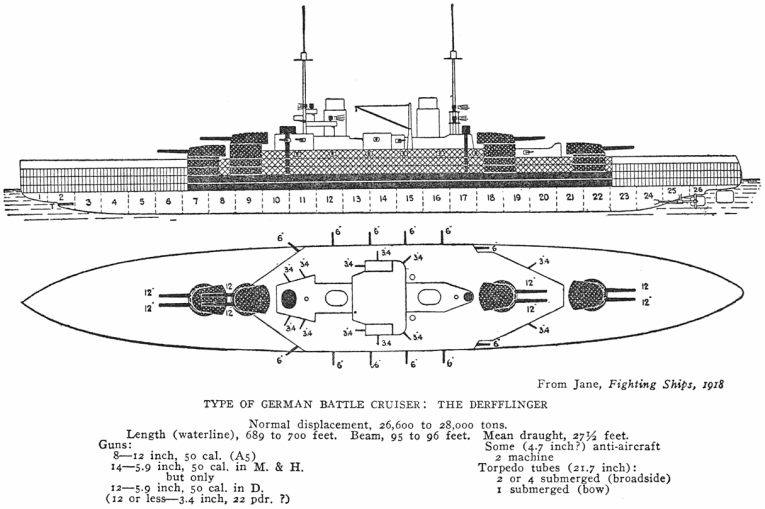

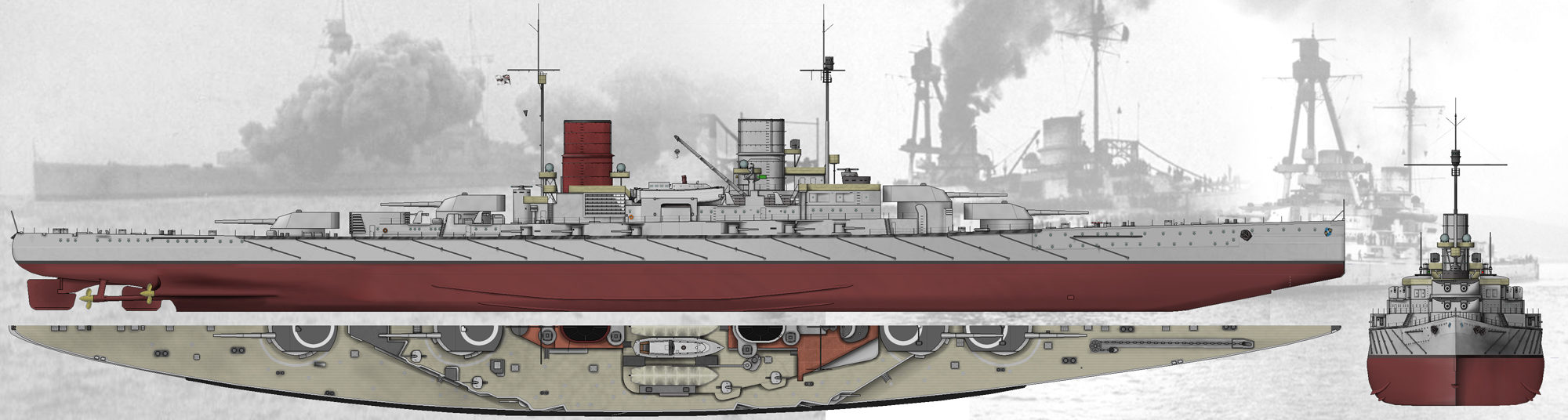

Derfflinger general design scheme on Janes 1919

Derfflinger was initially ordered as an addition, under the provisional name “K”, but the other two were supposed to replace older ships as per usual. Lützow was ordered as Ersatz Kaiserin Augusta replacing the old protected cruiser SMS Kaiserin Augusta while the contract for SMS Hindenburg was named Ersatz Hertha, replacing the protected cruiser SMS Hertha.

SMS Derfflinger was named after Georg von Derfflinger, a Brandenburg-Prussia field marshal distinguished during the 30 years war in the 17th centry. The contract was awarded to Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, under construction number 213. She was also the least expensive at a cost 56 million gold marks, which is rare for a lead vessel. Laid down on 30 March 1912, she was ready for launch on 14 June 1913, but during the ceremony one wooden sledge upon which the hull rested got stuck jammed so she refused to slide. In fact it took until 12 July, almost a month later to have her released and enter the water. Completion therefore was delayed, and she only was commissioned on 1 September 1914, with the war just a few days old.

SMS Lützow was named after Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow, a napoleonic era Prussian Notable that created the Freikorps. The contract of Ersatz Kaiserin Augusta was awarered to the Schichau dockyard in Danzig, under construction number 885. Cost was 58 million gold marks. Her keel was laid down on 15 May 1912, not long after her sisyter ship, and she was launched on 29 November 1913, so actually her completion was made during wartime, with massive shortages of personal and skilled labor, recources being rdirected elsewhere. Trials and post-fixes took time so she was only commissioned on 8 August 1915, almost one year after the war.

SMS Hindenburg, had to be named otherwise, but she was renamed to honor Germany’s statesman at the time, Paul von Hindenburg, as a recoignition gesture by the Kaiser, despite the fact her arguably would have more leverage than the Kaiser himself in time. As the final ship of the class, her delayed construction, awarded at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven (construction number 34) allowed engineers to refine the design and make significant changes (see later). She was also the costliest of all three at 59 million gold marks. She was laid down 1 October 1913, launched on 1 August 1915 (a week before the commission of Lützow) and eventually commissioned on 10 May 1917. By that time, the maritime phase of the war was basically over and the Kaiserliches Marine, after an half-success at Jutland, condemned to inaction, to the dismay of Hindenburg’s crews.

Design of the Derfflinger class

Hull & construction

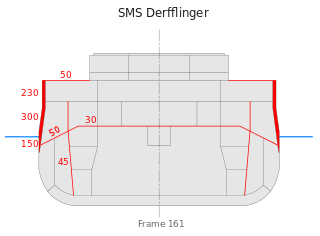

Armor cross section of SMS Derfflinger

SMS Derfflinger and Lützow measured 210 m (690 ft) long at the waterline, and 40 cm longer (3 in) overall. They had a beam of 29 m (95 ft 2 in), and a draft of between 9.20 m (30 ft 2 in) forward, up to 9.57 m (31 ft 5 in) aft. They were were designed to displace 26,600 tonnes (26,200 long tons) standard load, then 31,200 tonnes (30,700 long tons) fully loaded, at combat weight. Their hulls were constructed from longitudinal steel frames only as stated before, with the outer hull plates riveted over this structure. The usual practice was to cross vertical and longitudinal frames. SMS Derfflinger’s below the waterline was subdivided into sixteen watertight compartments. This was revised on SMS Lützow with an extra seventeenth compartment. All three had a double bottom running for 65% of the total hull length. Although a decrease comared to Seydlitz, (75% of the hull), this was deemed sufficient enough.

At sea, all three ships had a metacentric height of 2.60 m (8 ft 6 in), meaning they had good stability and predictable roll. They were widely regarded as excellent sea boats, with gentle motion, although their low flush deck hull made for low freeboard and they were “wet” at the casemate deck. Being beamy ships, they also lost up to 65% speed when hard over, heeled up to 11 degrees, a greater figure than any preceding German battlecruiser. This trigerred a rebuilt and anti-roll tanks were fitted to SMS Derfflinger at her first refit.

General design

They general appearance was really different than any battlecruiser which preceded them, and they could be dubbed “2nd generation”, the fist one, all with forecastles and 28 cm guns being the Von Der Tann, Moltke, Goeben and Seydlitz. Having 30 cm guns was really a noverlty, as well as being all centerline, as the flush deck, and the superstructures grouped in the center of the ship as a result. The turret N°3 was widely separated from N°4, with a vents structure in between, communicating to the lower decks. As previous ships, the bow was doubled underwater by an icebreaking bow. There were two pole masts in front and aft of respective funnels, and supporting small lookout posts, larger for the mainmast. After refits, these were rebuilt as solid tripods with a large fire control post, after what was done on SMS Hindenburg. They had two small bridges, a captain bridge forward of the main conning tower, and an admiral bridge placed on a platform at the foot of the mainmast. The Derfflinger class also had four projectors placed on separate platforms around the funnels.

Standard crew comprised by default 44 officers and 1,068 men, but when used as flagship for the I Scouting Group, they had accomodation to house 14 officers and 62 men in addition. The Derfflinger class also carried the usual service small craft fleet, grouped in between funnel amidship and served by two cranes: One picket boat, three barges, two launches, two yawls, two dinghies. The steam launched wcould be used to searhead a landing party, but they were not given fitting to operate a small field gun or dismountable onboard salute gun. The 8,8 cm were used as such.

Armour protection

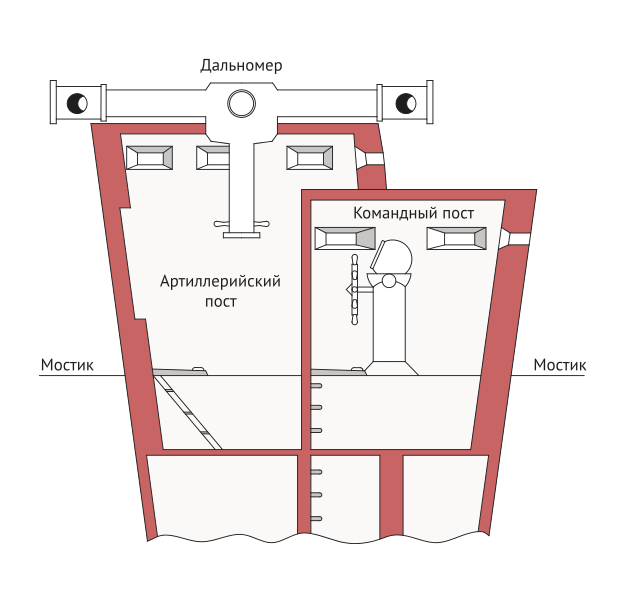

Conning tower design, Derfflinger class

All three Derfflinger-class were basically protected by a repeated scheme inherited from the Moltke class and Seydlitz. Krupp cemented steel armor was used everywhere, based on a longitudinal framing for the hull. Here are the detailed figures:

-Main armor belt 300 mm (12 in) alongside the central citadel (between N°1 and N°4 barbettes)

-Outer belt 120 mm (4.7 in) forward, 100 mm (3.9 in) aft.

-Tapered down to 30 mm (1.2 in) at the bow.

-Torpedo bulkhead 45 mm (1.8 in), 4m behind the main belt.

-Main armored deck 30 mm on average

-Deck over sensible areas 80 mm (3.1 in) – Ammo magazines and steering.

-Forward conning tower 300 mm thick walls, 130 mm (5.1 in) roof.

-Aft conning tower 200 mm (7.9 in) walls, 50 mm (2 in) roof.

-Main battery turrets front & sides 270 mm (11 in), roofs 110 mm (4.3 in).

-Secondary guns casemates 150 mm.

-Secondary guns shields 70 mm (2.8 in).

The three ships also carried protective nets stored along their side, until 1916 at least. The were retired later.

Powerplant & Performances

Athiough planned for SMS Derfflinger the centerline shaft diesel engine first planned, was not yet ready for use. A plan was setup as an interim measure, and the planned three-shaft system was abandoned. They reverted to four-shafts. They had two sets of marine-type turbines driving each two 3-bladed propeller screws 3.90 m (12 ft 10 in) in diameter. Lützow differed by having 4 m (13 ft 1 in) propellers, just as on SMS Hindenburg. Each set comprised a low-pressure turbine reserved for cruising and the inner shafts, and high-pressure machines driving the outer shafts. Steam was provided by 14 coal-fired admiralty-type twin boilers (one feeding face at each extremity) but also eight oil-fired equally double-ended boilers. In addition, electrical power was provided by two turbo-electric generators driven in turn by two diesel-electric generators for a grand total of 1,660 kilowatts -for 220 volts.

As designed, their machinery was supposed to deliver 62,138 shaft horsepower (46,336 kW) at 280 rpm calculated. Top speed on paper was 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph). Trials were less optimistic: SMS Derfflinger managed a much greater output of 75,586 shp (56,364 kW) but top speed remained sub-par, at 25.5 knots (47.2 km/h; 29.3 mph) only. Lützow managed even better at 79,880 shp (59,570 kW) and top speed reached 26.4 knots (48.9 km/h; 30.4 mph). Both had two sets of rudders.

SMS Derfflinger carried at normal load, in peacetime 3,500 t (3,400 long tons) of coal, 1,000 t (980 long tons) of oil, and was able at a cruising speed of 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) to reach 5,600 nautical miles (10,400 km; 6,400 mi), still a far cry of what was hoped if they had fitted with a diesel. SMS Lützow on her side coukd carry 3,700 t (3,600 long tons) of coal, 1,000 tons of oil and same range.

Armament

Forward main turrets

Eight 30.5 cm SK L/50

The Derfflinger class had height 30.5 cm (12 in) SK L/50 guns in four twin gun turrets. Two forward in a superfiring pair, two aft in similar arrangement but with N°3 further apart. They were given Drh.L C/1912 mounts. These turrets were traversed by electric power but the guns were elevated hydraulically. Here are the main caracteristics:

- 405.5-kilogram (894 lb) AP shell, SAP, HE

- 855 meters per second (2,805 ft/s) muzzle velocity.

- Elevation 13.5° maximum.

- 18,000 m (20,000 yd) range at max elevation.

- Rate of fire 2–3 shells per minute

- 720 shells carried in all, 90 per gun: 65 AP, 25 SAP.

- Barrel Life expectancy: 200 rounds

Although they were also tested to fired the 405.9 kg (894.8 lb) high explosive shell, it was not provided, except for coastal bombardment missions. The shells were loaded with two RP C/12 propellant charges, the main with 91 kg (201 lb) a brass cartridge and a silk bag that weighed 34.5 kg (76 lb) fore charge. Propellant magazines were located underneath shell roomsin forward turrets and N°3, but it was reversed for the N°4 turret.

1916 modifications: The turrets were upgraded for their mounts, allowing an elevation increase 16°, raising the range to 20,400 m (22,300 yd). The 25 semi-AP shells provided to each gun was for use against targets limuted armor protection targets such as cruisers and destroyers.

Fourteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 gun

Seocndary artillery was located in the battery deck, making the central superstructure in the center of the ship. This made for a shorter armour lenght to protect. All these guns were in casemates, five on either side in recesses with around 150° traverse, two forward of the superstrucure, firing in chase, and two after, in retreat, with better arc of fire, so seven per side. On Derrfinger, two were deleted later when she was fitted with anti-roll tanks as extra room was needed.

Essential points:

- 45.3 kg (99.8 lb) HE shell

- 835 meters per second (2,740 ft/s) muzzle velocity.

- Elevation 19° maximum.

- 13,500 m (14,800 yd) range at max elevation.

- Rate of fire 7 shells per minute

- 160 shells carried per gun: HE types.

- Barrel Life expectancy: 1400 rounds

These 45.3 kg (99.8 lb) HE shells were loaded with a single 13.7 kg (31.2 lb) RPC/12 propellant charge, with brass cartridge. In 1916, an upgrade allowed them to fire at 20°, raising the range at 16,800 m (18,400 yd).

Eight 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 guns

Definitely the standard for German capital ships in WWI, these guns were considered better than the standard British Vickers 3-in in some areas. On the Derfflinger class, they were provided with two different configuraton for antiship and AA fire:

Four were placed in the forward superstructure, four in the aft one, all protected by curved, enveloping light shields (to protect from splinters). In 1916 however they were removed, and only four mdified FLAK models were retained, and these Flak L/45 anti-aircraft guns emplaced around the forward funnel for for Lützow around the rear funnel, had an maximal elevation of 70°, reworked MPL C/13 mounting for better speed and elevation, better optics, larger choice of shells, with the standard 9 kg (19.8 lb) HE model. The FLAK 8,8 cm had an effective ceiling of 9,150 m (30,019 ft 8 in) indeed at max range and was accurate.

Four 50-60cm Torpedo Tubes

SMS Derfflinger was given at the origin, four 50 cm tubes located underwater in the bow, stern, and two admiship. Lützow and Hindenburg were upgraded with new and much more powerful 60 cm tubes.

-The 50 cm torpedoes of the G7 type were the stanfdard of the time across the Kaiseliches Marine, 7.02 m (276 in) long with a 195 kg (430 lb) Hexanite warhead, range of 4,000 m (4,370 yd) at 37 knots setup speed, and 9,300 m (10,170 yd) at 27 knots setup.

-The 60 cm torpedoes of the H8 type were 8 m long, carrying a 210 kg (463 lb) Hexanite warhead, having a range of 6,000 m (6,550 yd) at 36 knots and even 14,000 m (15,310 yd) at 30 knots. Both Lützow and Defflinger used their tubes at Jutland.

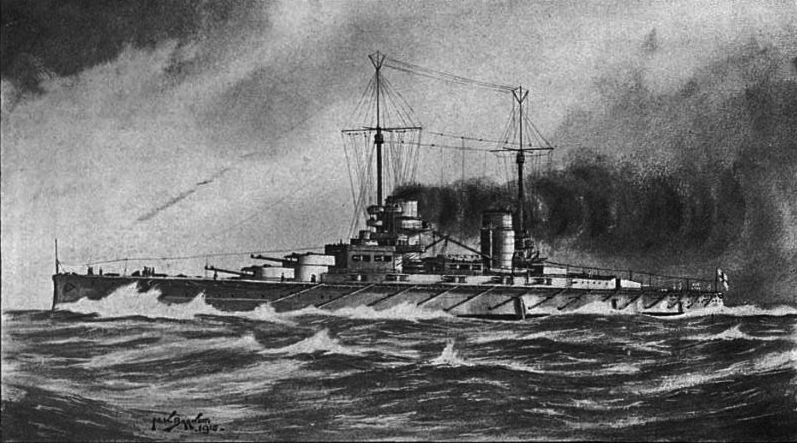

Derfflinger in 1915, old author’s illustration

Derfflinger specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 210,40 x 29 x 9,20 m |

| Displacement | 26,500t, 31,200t FL |

| Crew | 44+1068 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts 2 Parsons turbines, 14 Schultze-Thornycroft boilers, 62,130 hp |

| Speed | 26.5 knots (49.3 km/h; 30.6 mph) |

| Range | 5,600 nmi (11,400 km; 6,400 mi) at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Armament | 4×2 305mm, 12x150mm, 12x 88mm, 4 TT 450mm* (2 sides, bow, stern). |

| Armor | Battery 150, citadel 250, turrets 270, belt 300, blockhaus 350, barbettes 260 mm |

The last German Battlecruiser, SMS Hindenburg

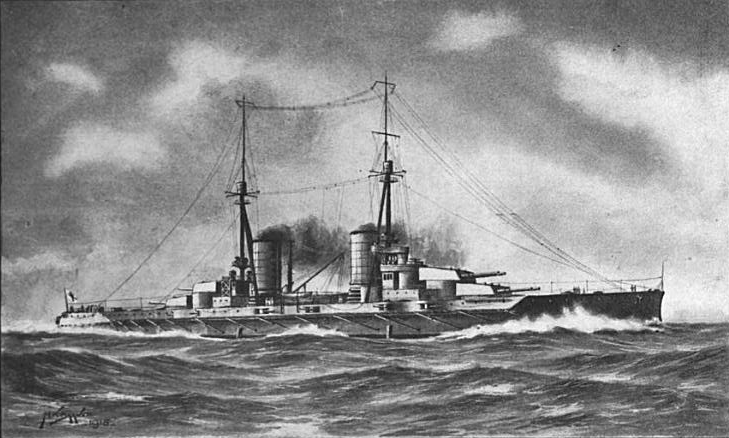

The Derfflinger (colorized photo).

Hindenburg was slightly longer than her sister ships at 212.50 m (697 ft 2 in) at the waterline and 212.80 m (698 ft 2 in) overall. She also displaced slightly more, at 26,947 tonnes (26,521 long tons) standard and 31,500 tonnes (31,000 long tons) fully laden. Like Lützow she had 17 underwater compartments fo ASW protection. Her power plant was rated at 71,015 shp (52,956 kW) at 290 rpm, for a top speed of 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph). On trials she reached 94,467 shp (70,444 kW) and 26.6 knots (49.3 km/h; 30.6 mph).

She also stored mre than her sister-ships, 3,700 tons of coal, as well as 1,200 t (1,200 long tons) of oil; Her range at 14 knots was rated at 6,100 nautical miles (11,300 km; 7,000 mi). Her main guns were upgraded, having the new Drh.L C/1913 mounts allowing for a slightly faster reload and elevation. For protection, thickness of the turret roofs was increased to 150 mm (5.9 in) but the rest was identical.

But the main change was the installation of a brand new fire control direction tower with telemeter (by default, she had two of these, installed on their respective conning towers fore and aft). The FCS top was supported by a massive tripod, in opposition of the usual style of simple pole masts. The British had the time were markedly superior in this regards, with advanced telemetry in large spotting tops, linked with ballistic computers. They were only deserved by the quality of shells, many of which hit but failed to detonate, as seen at Jutland. The main feature of SMS Hindenburg was repeated on her earlier sister ships in 1917-18.

Derfflinger in 1915, old author’s illustration

Hindenburg specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 212,8 x 29 x 9,4 m |

| Displacement | 26,960t, 31,500t FL |

| Crew | 1182 |

| Propulsion | 4 screws, 4 Parsons turbines, 18 Schultze-Thornycroft boilers, 71 000 hp |

| Speed | 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) |

| Range | 6,100 nmi (11,300 km; 7,000 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Armament | Same |

| Armor | Same but turret roofs 15 cm (5.9 in) |

Links & resources

Books

John Gardiner Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1921-1947.

Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. Pen & Sword

Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918, Bernard & Graefe Verlag.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Tome I. Annapolis

Herwig, Holger (1998). “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Humanity Books.

Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Osprey Books

Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. Cassell Military Paperbacks.

Breyer, Siegfried (1997). Die Kaiserliche Marine und ihre Großen Kreuzer. Podzun-Pallas Verlag.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1978). Battle Cruisers. Warship Special. 1. Conways

Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Kaiser’s Battlefleet: German Capital Ships 1871–1918. Seaforth Publishing.

Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley

Staff, Gary (2014). German Battlecruisers of World War One: Their Design, Construction and Operations. Barnsley

Links

Germany 30.5 cm/50 (12″) SK L/50″. NavWeaps.com.

German 15 cm/45 (5.9″) SK L/45″. same

German 8.8 cm/45 (3.46″) SK L/45, 8.8 cm/45 (3.46″), same

German Torpedoes Pre-World War II, same

About the scuttling – IWM

Derfflinger class on wikipedia

Videos

Grosse Kreuzer Hindenburg By willembrock

Hindenburg salvaged 1930

Gallery

Painting of the Lützow and Derfflinger at Jutland, May, 31, 1916

Active service

SMS Derfflinger

Built at Blohm & Voss and launched in difficult conditions (The wooden sledges jammed, the ship was launched a second time on 12 July 1913), SMS Derfflinger had a crew composed of dockyard workers at first, conducting her for fitting out in Kiel by early 1914. In July, 27th, the fleet was placed on a state of heightened alert with Derfflinger being feverishly completed. It was feared notably an attack from the Russian Baltic Fleet in the inverted style of the Russo-Japanese War, but this proved futile. At last, SMS Derfflinger was commissioned on 1 September and sailed out for her sea trials. By late October she was assigned to the I Scouting Group but unseen at first during trials, she developed turbines issues and had to be dockyard until 16 November. She was ready on 20 November, out at sea with the light cruisers SMS Stralsund and Strassburg plus the Vth Torpedoboat Flotilla, veturing some 80 nautical miles northwest of Heligoland without spotting anything and make it back.

Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

Bombardment of Whitby

SMS Derfflinger participation to the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby was performed by the entire I Scouting Group, after the success of the raid on Yarmouth. Admiral von Ingenohl wanted still to have a portion of the Grand Fleet detached and sent into a trap. This forced was under orders of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper, flagship Seydlitz, and Derfflinger was second in line, followed by Moltke, Von der Tann, and Blücher, four light cruisers, two squadrons of torpedo boats, and the Hochseeflotte departing afterwards to provide distant cover. Meanwhile British intel had Vice Admiral David Beatty’s scrambling his four battlecruisers to intercept them. Admiral Ingenohl, informed of this ordered to retreat, Hipper still unaware and proceeding with the bombardment, with Derfflinger and Von der Tann on Scarborough and Whitby, before retreating eastward as planned. Later, confusion allowed the German light cruisers to slip away while Hipper now knew the location of the British battlecruisers and wheeled to the northeast, escaping.

Battle of Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank

In early January 1915 British ships were spotted in the Dogger Bank area, Admiral Ingenohl being reluctant to send his forces since I Scouting Group was deprived from Von der Tann, in maintenance. But Konteradmiral Richard Eckermann decided otherwise and ordered Hipper to go, on 23 January. His flagship was Seydlitz, followed by Moltke, Derfflinger, and Blücher. British intel again foiled these plans, and Beatty’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron sailed, at the same time as Rear Admiral Archibald Moore’s 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron and William Goodenough’s 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, to meet Reginald Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force north of the Dogger Bank.

After the duel between Kolberg and Aurora, Hipper turned his battlecruisers towards while soon spotting a number of ship, and without precision, Hipper decided to retreat, at a slow limited by the armored cruiser Blücher, caught soon by British Battlecruisers and sunk, but not before Hipper turned to face Beatty, concentrating on Lion from 16,500 metres (18,000 yd). New Zealand engaged Blücher, Sydlitz was crippled and Moltke left alone, but SMS Derfflinger was hit once, with minor damage, two armor plates forced inward and coal bunkers flooded. With Seydlitz badly damaged and Blücher crippled, the chase ended when Beatty was signaled U-boats in the cicinity, allowing Hipper to retreat.

Raid on Yarmouth and Lowestoft

Derfflinger at Lowestoft

SMS Derfflinger also took part in the raid on Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April 1916. The I scouting group was commanded this time by Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedicker. SMS Derfflinger this time operated with her sister ship SMS Lützow, just commissioned, and the seasones Moltke, Seydlitz and Von der Tann, sailing with a screening force of six light cruisers and two torpedo boat flotillas, while High Seas Fleet (Admiral Reinhard Scheer) sailed later, at 13:40 as distant support. The British Admiralty was alerted again by Room 40 and the Grand Fleet was at sea at 15:50.

At 15:38, Seydlitz hit a mine and had to retreat, the flag being passed onto via the Lützow torpedo boat V28, and cruisers turned south towards Norderney avoiding the minefield. On 25 April before noon, the battlecruisers approached Lowestoft, with Rostock, Elbing, covering the southern flank. They spotted Commodore Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force. Boedicker went on nevertheless, and rampage the city, until retreating northwards at 05:20, in degrading visibility for the next city, Lowestoft, which was spared much damage. On the return trip, Bodicker stumbled upon the Harwich Force, which fled south, but reports of British submarines ended the chase.

Battle of Jutland

Derfflinger Firing a full salvo

Soon after, Scheer planned a sortie, waiting for Seydlitz to be repaired. On 28 May, repairs over, SMS Seydlitz was back to I Scouting Group which spent the night on the Jade on 30 May and then steamed towards the Skagerrak at 16 knots, SMS Derfflinger being second in line after the flagship Lützow, Seydlitz being behind. The II Scouting Group (light cruisers Frankfurt, Wiesbaden, Pillau, Elbing, 30 torpedo boats) provided the surrounding screen.

The High Seas Fleet left the Jade just 1h30 later, again to be posted as distant cover, with 16 dreadnoughts. The details of the battle of jutland can be seen in detail here. Hipper’s batteline engaged soon the 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons at 14,000 metres (15,000 yd) and due to poor communication to coordinated targets, Derfflinger was left alone for ten minutes, and concentrated with increasing accuracy on HMS Lion, the flagship. Soon HMS Indefatigable exploded, hit by Von der Tann but the four Queen Elizabeth-class battleships emerged from the mist, and fired first at Von der Tann and Moltke. Seydlitz engaged Queen Mary, which was soon crippled and later exploded.

However at around 18:09 and at 18:19, SMS Derfflinger was hit by 15 in shells from either Barham or Valiant, as well as 18:55, the latter destroying her the bow and creating flooding. After 19:00, Lützow’s commander ordered the while line to fire on newly found light British cruisers, and they sunk HMS Defence. At 19:24 Beatty’s remaining battlecruisers spotted Lützow and Derfflinger and openend fire again, concentrating for eight minutes on Lützow, but the latter and Derfflinger replied well, Derfflinger firing he final and fatal salvo at Invincible, which magazine forward detonated.

By 19:30 the High Seas Fleet came into fray as Scheer, considered folding up at dark fell, stumbled upon the Grand Fleet and could not disengage so easily. Derfflinger and the other battlecruisers changed twice direction which led them pointing towards the center of the British fleet, creating a deadly “T”. Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke, Von der Tann high speed “death run” masked attacking destroers which suceeded on disrupting the British formation. Soon after, the German battlecruisers turned in retreat, Derfflinger and the other having tme to repair their damage when possible. At 21:09, they were spotted again by the British and a formidable engagement saw at less than 7,800 metres Derfflinger hit several times, destroying notably her last operational gun turret while Lion and Princess Royal were also hit.

After Admiral Mauve turned his ships the British did not pursue and the battle ended at 03:55, Hipper reported to Admiral Scheer his fleet was crippled and no longer operational. SMS Derfflinger for her part had all but one turret knocked outn, after being hit 17 times, mostly by 14 and 15 inches shells, plus nine times by secondary guns. She fired 385 main guns shells and 235 rounds for her secondaries, and she also fired a torpedo. She also deplored 157 killed, 26 wounded, the highest toll of any battleship present to be not destroyed at Jutland on the German side. Her drydock repairs would last until 15 October, but for her stalwart resistance at Jutland, the British soon nicknamed her “Iron Dog”. With “shell magnet” and others, from that day, German Battlecruisers gained an ominous reputation, mostly due to their original design choices.

Later operations

SMS Derfflinger in 1918, note her new tripod mast

Derfflinger made battle readiness training (Baltic Sea) until the end of 1916 but had little to do as the U-boat campaign had preiority. The German surface fleet meanwhile was tasked of defensive missions. However, Derfflinger intervened during the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight (November 1917) when dispatched to assist hard pressed German light cruisers (II Scouting Group) arriving too late. On 20 April 1918, covered a minelaying operation off Terschelling and soon attention shifted towards supply convoys between Britain and Norway. In October and December 1918 two such convoys were destroyed. The next would be heavily escorted with the Grand fleet. Hipper planned a new operation, launched on 23 April 1918, and after Moltke lost her inner starboard propeller, the German fleet missed the convoy. SMS Derfflinger was also mobilized at the very end of the war to participate to the “death ride” from Wilhelmshaven, later cancelled due to desertion en masse of war-weary sailors. Derfflinger and Von der Tann had for example hundreds deserting when crossing the locks separating Wilhelmshaven’s inner harbor and roadstead.

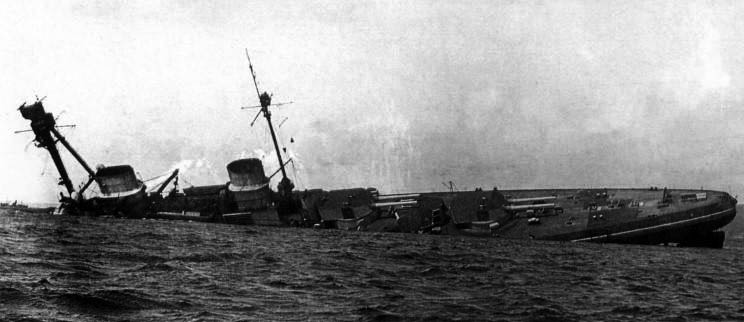

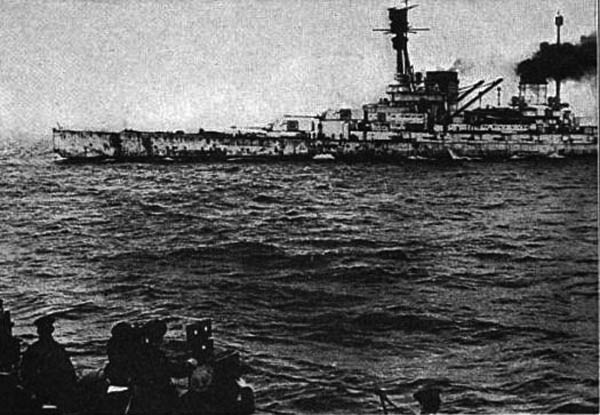

Underway at Scapa Flow, 1919

Scuttled, capsized, in June 1919.

On 24 October 1918, this was over. After the capitulation, Derfflinger followed the rest of the fleet in captivity in Scapa Flow. On the morning of 21 June, as ordered by Reuter, scuttling preparation were made, opening valves and removing the lockings, detonating charges at 11:20, leaving her to sink at 14:45. Raised in 1939 she was left off the island of Risa until 1946, still upside down, then sent to Faslane Port to be broken up in 1948.

SMS Lützow

SMS Lutzow illustration as depicted in Janes

SMS Lützow was originally ordered as Ersatz Kaiserin Augusta, replacing as per usage, the former SMS Kaiserin Augusta. Built at Schichau-Werke, Danzig (more accustomed to smaller Torpedo Boats & destroyers) laid down in May 1912, launched 29 November 1913, she was commissioned on 8 August 1915, starting sea trials before heading to Kiel on 23 August for final adjustments and post-trial fixes. The torpedo boats G192, G194, and G196 shielded her from possible hostile submarines in the area. Final fitting out done and armament installed, she departed on 13 September for further armament trials, including torpedo firing tests (15 September) followed by gunnery tests on 6 October. It was soon detected her port low-pressure turbine had broken gears, so repairs took place in Kiel until late January 1916, followed by further trials and the whle preparation process ended on 19 February 1916, delaying from eight month her entry into service ! – SMS Lützow was eventually assigned to I Scouting Group, on 20 March, notably with her sister ship and other battlecruisers of the Hochseeflotte. She had missed three major engagements to that point.

Her first -and only- captain was Victor Harder. On 24 April, she departed with Seydlitz and Moltke for a brief foray into the North Sea, at the eastern end of the Amrun Bank, where British destroyers had been reported and followed by a second sweep two days later. A British submarine ambushed, but missed Lützow underway. Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedicker, I Scouting Group, raised his flag on Lützow from 29 March until 11 April as his usual flagship was in maintenance. On 21–22 April, she joined in anorther sortie into the North Sea, for nothing.

Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft

Before Jutland, Lützow’ first major operation was this raid, on 24–25 April. The Scouting Group was under orders of Boedicker. Lützow was third in line, followed by Moltke, and Von der Tann. As described above, British Room 40 informed the admirakty that despatched in advanced Beatty’s battlecruisers and prepared the Grand Fleet to depart in turn from Scapa Flow, hoping to ambush the battlecruisers on their return trip. Avoiding Dutch observers on Terschelling the fleet was underway when flagship Seydlitz struck a mine and torpedo boat V28 took back admiral Boedicker to Lützow, the new flagship for this operation.

The bombardment of Lowestoft on 25 April took place whereas two German cruisers fought Reginald Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force. Poor visibility spared Yarmouth, and on their way back crossed the Harwich Force again so Lützow opened fire like the rest of the line at 12,000 m (13,000 yards). The battle was soon over as the British fled and the Germands made their way home.

Battle of Jutland

On 31 May 1916, I Scouting Group departed the Jade estuary with SMS Lützow now promoted as Hipper’s flagship in the lead, followed by Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke, and Von der Tann. As explained above and detailed in the battle’s page, at 16:00, Hipper’s battlecruisers fought their direct opponents from Vice Admiral David Beatty’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The signal “Distribution of fire from left” was hoisted on Lützow for all ships to followed. Lützow was in fact the first to open fire (the battle of jutland’s opening shots), at 15,000 yards (14,000 m). HMS Lion and Princess Royal concentrated soon on Lützow, hoping to cripple the flagship and desorganize the German line.

Meanwnhile Lützow engaged HMS Lion. Her gunners overshoot at 16,800 yards (15,400 m), firing semi-armor-piercing (SAP) shells unlike the others, to tracers could be seen and followed by all, useful in the bad visbility. The others indeed used only AP shells. British rangefinders misread the range and overshoot as well. HMS Lion fired at 18,500 yards (16,900 m) but during three minutes, Lützow fired four more salvos, and hit their mark on the last one at 16:51, followed by a second hit a minute later, while 8 minutes later, Lion scored her first hit on Lützow, hitting (but bouncing apparently) her forecastle. Lützow at last dealt a tremendous blow as one shell penetrated the roof of Lion’s center “Q” turret. This detonated ammunitions stored inside, but flooding prevented explosion by prompt action of commander—Major Francis Harvey, which had the magazine flooded.

Meanwhile, this looked not good for Beatty: Indefatigable was sunk by Von der Tann and Lützow went on pounding Lion, but with moderate damage. Her gunnery officer, Günther Paschen, later regretted using SAP shells, thinking using AP rounds instead would have probably destroyed Lion, Beatty’s flagship and quickly end the contest as clear-cut German victory. Lützow fired 31 salvos at Lion so far for just six hits (telling volumes on accuracy at the time) and at least had HMS Lion shearing out of line temporarily. With haze, gunners believed they engaged Princess Royal whereas it was still HMS Lion. HMS Princess Royal however, immediately behind, scored two hits on Lützow. The first exploded between the forward turrets, the second on the belt. At 17:24 Lion was hit three times more in thirty seconds, her gunners being far more accurate at that stage.

Beatty ordered a turn just when the Queen Elizabeth-class battleships (5th BS) entered the fray, and opened fire, to the dismay of Hipper that was until then the winner of the engagement. Queen Mary was sunk, while opposing destroyers made torpedo attacks. HMS Nestor and Nicator targeted, but missed Lützow. At 17:34, Lützow launched her own broadside tube torpedo on the distant HMS Tiger, but without success. She also scored another hit on Lion, then three, and a fire broke out in the aft secondary battery of Beatty’s flagship.

Hipper was now engaged at 18:00 against both the remaining British battlecruisers and Queen Elizabeth-class battleships and 15 in (380 mm) shells were certainly a more serious threat for his hybrd battlecruisers. HMS Queen Elizabeths engaged and soon found its mark, hitting his flagship Lützow. She was hit again at 18:25 and 18:30, 18:45 and soon had both of her wireless transmitters damaged, Hipper seroting to searchlight messages afterwards.

After 19:00, he ordered his line a 16-point turn northeast to close with the approaching III Battle Squadron and assist the hard-pressed SMS Wiesbaden. During the cruisers screen engagement, HMS Onslow and Acasta approached Lützow, and launched a volley of torpedoes but missed. Onslow was hit thrice by her 15 cm guns and withdrawed. HMS Acasta however made another run, launched but missed again, and was soon engulfed by Lützow and Derfflinger’s combinded 15 cm barrage. Shi was hit twice and fled. At 19:15, Hipper’s lead ship spotted and engaged the armored cruiser Defence and at 19:16, Kapitän zur See (KzS) Harder ordered to fire despite Hipper’s hesitations about the nature of the ship. The other German battlecruisers and battleships joined in the melee; Lützow fired five broadsides in rapid succession. In the span of less than five minutes, Defence was struck by several heavy-caliber shells from the German ships. One salvo penetrated her ammunition magazines followed by a massive explosion.

Lion scored two more hits on Lützow, starting a serious fire, followed by them being spotted and fired upon by the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron. HMS Invincible scored 8 hits on Lützow concentrated in her bow and, causing massive flooding. Lützow and Derfflinger on her and at 19:33, Lützow’s third salvo entered her center turret, probably igniting the magazine, followed by a tremendous serie of explosion wiping out the ship. However Lützow was still hard-pressed, taking fire while listing badly by the bow, “ploughing” heavily.

At 19:30, the High Seas Fleet at last encountered the Grand Fleet and soon Scheer ordered Hipper to make his famous “death run” towards the British line. However it was declined by Lützow which lost speed and could not keep up. She tried to withdraw southwest but at 20:00, flooding reached the magazine for the forward turret and the crew frantically tried to evacuate as many shells and propellant charges elsewehere. At 19:50, Kommodore Andreas Michelsen (SMS Rostock) dispatched I Half-Flotilla’s G39 came to assist Hipper and take his staff aboard, to transfer him on another battlecruiser. V45 and G37 also laid a smoke screen but at 20:15 Lützow was hit by four 15-in shells. One made it though her forward superfiring turret, knocking it down, detonating a propellant. The second disabled the electric training gear of the rearmost turret, now hand-cracked for traverse. Hipper aboard G39 still tried to save I Scouting Group but command was now exerced by KzS Johannes Hartog. Lützow fired her last shot at 20:45, now obscured by smoke.

The end of Lützow

Nightfall saw Lützow steaming at 15 knots trying to return hime. By 22:13 the rest of I Scouting Group lost sight of her. Scheer hoped the foggy darkness would allo her to evade detection, but meawhile flooding appeared out of control, water reaching her forward deck, and floosing her forecastle above the main armored deck. At midnight, many thought she still could make it harbor, whereas she was now making 7 knots. At 00:45, the bow listing was such she plowed at 3 knots, only to reduce pressure on the rear bulkhead with forward main pumps’s control rods jammed.

By 01:00, the pumps were overwhelmed as Water now invaded the forward generator compartments. Light went off and the crew resorted to candlelight to continue trying save the ship. At 01:30 water flooded the forward boiler room and almost all of compartments in the forward section, up to the conning tower level were now underwater. Waves crashed above her bridge, leaped the base of the mast. Shell holes in the forecastle also created more leaks and the desperate attempts by the crew to patch the shell holes inhibited progress. At some point it was ordered to steam backwards, soon abandoned as the bow was submerged so much (17 meters) the propellers started to peep over the water.

At 2:20 she had taken some 8,000 tons of seawater and capsizing was no longer avoidable. To spare his crew at this point, KzS Harder gave the order to abandon ship. Torpedo boats G37, G38, G40, and V45 in escort came to take onboard the crew, though six men were still trapped in an air pocket in the bow. At 02:45 Lützow’s bridge itself was underwater, and from G38, Harder asked to scuttled her, firing two torpedoes. At 02:47, SMS Lützow, flagship of Hipper at Jutand disappeared approx. 60 km (37 mi) NW of Horns Reef. During the battle she fired an estimated 380 main battery shells, 400 rounds secondaryes and two torpedoes. She was hit 24 times and suffered 115 killed, 50 wounded. In 2015, her wreck was rediscovered by accident by HMS Echo while laying a tide gauge. So far, no ceremony or plaque has been made but she has the status of war grave.

SMS Hindenburg

Built at the the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Wilhelmshaven, SMS Hindenburg was the third and last of the Derfflinger class. She was ordered as replacement for SMS Hertha (Victoria Luise class cruisers), her keel laid down on 30 June 1913 at Kaiserliche Werft, Wilhelmshaven, and launched on 1 August 1915. Construction priorities of wartime delayed her completion so much she was only completed on 10 May 1917. British naval intelligence believed this was due to cannibalization to repair Derfflinger after Jutland, but it mostly was due to labor shortages and all priority given to submarine warfare by this point. For the same reasons, the Mackasen class was also suspended, as well as the last two sister ships of the Bayern class.

SMS Hindenburg was the last German battlecruiser, with very short career of two years. Only Fully operational by 20 October 1917, so after five months after fitting out of sea trials, armament trials, and fixes, training, but at this point the situation for the Hochseeflotte was of readiness in case of a large scale operation from the Grand Fleet. There was no operation planned in the north sea, to the point more assets were freed to unlock the situation in the Baltic, with success. However too precious even for this theater, SMS Hindenburg was kept in port, venturing at sea with the rest of the fleet for exercizes.

On 17 November 1917 however, SMS Hindenburg and Moltke, departed with the II Scouting Group as distant support for German minesweepers trying to block some areas to RN incursions, when British cruisers fell on them, soon joined with the battlecruisers HMS Repulse, Courageous, and Glorious, the latest commissioned. But by the time Hindenburg and Moltke arrived this was already too late. On 23 November, SMS Hindenburg became flagship of I Scouting Group, replacing the older Seydlitz.

Convoys to Norway

In late 1917, light German forces attacked British convoys to Norway. On 17 October, SMS Brummer and Bremse intercepted one of these, and sank nine of the twelve cargo ships en route, plus two escorting destroyers, HMS Mary Rose and Strongbow. On 12 December, four German destroyers again ambushed a second British convoy of five freighters escorted by two British destroyers and all were sunk plus one destroyers, the other returing badly damaged. This caused a scandal at the parliament and the British admiralty decided to bolster the protection of the next convoy with capital ships.

Admiral David Beatty now in charge of the Grand Fleet detached battleships for the next one, and Hipper saw this as an opportunity to revive the old tactic since the start of the war: Drawing a portion of the Grand Fleet to be isolated and destroyed peacemeal, reducing its overall superiority. Franz von Hipper, now Vice Admiral, planned the operation with of course the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group and their light cruisers and destroyers screen as vanguard force, and the Hochseeflotte in support, ready to pounce on the chasing British dreadnought battleship squadron.

At 05:00 on 23 April 1918, Hindenburg led the battle line from the Schillig roadstead. Hipper onboard ordered wireless transmissions to be near silent and taking a route out of reach from foreign observers. Unfortunately for them, the British admiralty still had the code books and Room 40 was not long to intercept a few messages. At 06:10 the battlecruisers were circa 60 km southwest of Bergen, when SMS Moltke lost her inner starboard propeller, causing by vibrations her entire engine gears disintigrating.

In the explosion which followed, debris from the broken machinery also damaged several boilers, tearing a hole in the hull and causing flooding, in addition to her machinery stopped dead. The crew tried to repair what they could, and the ship was later able to steam at a snail pace of 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) and she was left behind, to be towed by the detached battleship SMS Oldenburg.

Hipper went on northward and at 14:00 arrived in sight of the convoy route, crossing it but seeing nothing. Unbeknown to him, Room 40 had alerted the admiralty and the convoy schedule was changed, departing a day later. The same would happen in WW2 at several occasions after Enigma was broken. At 14:10, Hipper had no choice but to return home, veering southward. At 18:37, the fleet was back in the maze of defensive minefields placed in defence of the German coast and bases.

The death ride

On 11 August 1918, Hipper was promoted to Admiral, given overall command of the entire High Seas Fleet. Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter also replaced him at the head of I Scouting Group, with Hindenburg as his flagship. But nothing happened in 1918, as the entire fleet was stuck in harbor, much enraging the sailors that were highly criticized for their inaction whereas German was crippled by the British blockade, and the submarine warfare not giving the expected results. After the Americans entered the fray indeed, the US Navy participated now in the atlantic convoy and US capital ships were even detached in reinforcement to the Grand Fleet.

Born of despair, Hipper in September started to think about a “death ride” for the whole High Seas Fleet. The idea was to make a sortie and seek engagement, whatever the result. The goal was to give German a better bargaining position at the negociation table as defeat seemed inevitable. The plan was refined in October and Admiral Reinhard Scheer was charged of the detailed operations, with nothing more than a full attack and causing maximium damage to the Royal Navy, being confident enough since the results of the Battle of Jutland.

Scheer planned two simultaneous attacks by light cruisers and destroyers off Flanders and on shipping in the Thames estuary acting as a bait. The four battlecruisers would be sent in support the Thames attack. After after this, the Hochseeflotte was to concentrate off the Dutch coast, ready to meet the Grand Fleet that would have been sent inevitably. For this, the fleet was to be assembled first in Wilhelmshaven on 23 October 1918.

However by that stage of the war, discontent from war-weary sailors reached a peak. The decision to sent Lenin to Russia to trigerr the revoluition had backfired and bolshevism was now growingly popular among sailors, with elements that started to politicize entire crew sections. This all developed “under the rug” in 1918 and reached boiling point. At Whilehlshaven, disgruntled sailors decided to desert en masse, notably for Von der Tann and Derfflinger as they went through the harbour locks.

On 24 October 1918, even though, Scheer ordered to sail from Wilhelmshaven, but the crews disobeyed in most ships, on strike. It reached even the no-return point in the night of 18-29 October, sailors with outright mutiny on several battleships. Officers were placed under lock and key and molested. Those of III Battle Squadron refused to weigh anchors and sabotage were committed on board Thüringen and Helgoland. With all these ominous reports incoming Scheer rescinded the operation, which was later cancelled for good and the squadrons were dispersed to avoid “contagion”.

The 1919 internment and scuttling

The last chapter for Hindenburg, which never fired her guns in anger so far, was rather sad. Under the Armistice preliminary terms, the Allies ordered the fleet was to be conducted ti Scapa Flow, the main base for the Grend Fleet and kept here under custody, pending the result of negociations. SMS Hindenburg, as flagship of the scouting squadron and modern capital ship was concerned and on 21 November 1918, departed along three other battlecruisers, 14 capital ships, seven light cruisers, and 50 destroyers. Admiral Adolf von Trotha briefed Reuter which commanded the fleet about instructions in case the entente would try to seize the ship, of scuttling. The fleet spotted first HMS Cardiff, which led them to assembled entente fleet, a combined British, American and French armada of more than 370 vessels.

Interned in Scotland, news were rare and only came through supplies with letters from home. Negociations at Versailles went on, and Reuter was given a copy of The Times statung the Armistice was to expire at noon, on 21 June 1919, the signature deadline for German negociators. Her believed that after this, hios fleet would be saied by the British and possibly donatedto all belligerents. As instructed he started to plan the scuttling, and on the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow for training maneuvers, leaving Reuter the chance her waited for, transmitting at 11:20 the order to scuttled the ships, performed by loyal skeleton crews (troublesome elements had been sent back to Germany a while ago). SMS Hindenburg was the last to sink, at 17:00, and deliberately on an even keel, not only to allow an easier evacuation by the crew but also flying proudly the Kaiserlichesmarine pennant, in view of everyone. She would be raised on 23 July 1930 after several attempts, scrapped at Rosyth between 1930 and 1932, her bell saved and now on display at the Bundesmarine HQ since 1959.

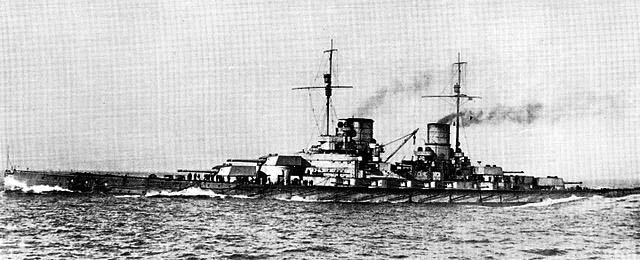

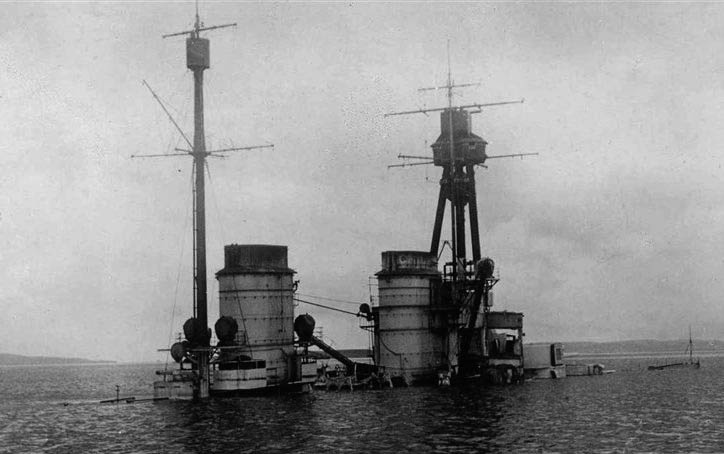

Hindenburg steaming to and in Scapa Flow.

SMS Hindenburg scuttled, still straight. This enabled a torough examination by Royal Engineers later.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign