Japan, 1919. Kuma, Tama, Kitakami, Oi, Kiso

Japan, 1919. Kuma, Tama, Kitakami, Oi, KisoWW2 IJN Cruisers:

Furutaka class | Aoba class | Nachi class | Takao class | Mogami class | Tone classTenryu class | Kuma class | Nagara class | Sendai class | Katori class | Agano class | Oyodo

Tsushima | Asama | Tokiwa | Yakumo | Izumo | Kasuga | Hirado

The five cruisers of the Kuma class were first planned in 1916, but entered into service after WW1, the last one in 1921. Enlarged versions of the Tenryu, they had three more main guns, were more powerful and faster, but only for an increased displacement of 1500 tons, a compromise between true light cruisers and scouts. They were active in the interwar and WW2 as well, still useful in many combat operations from the Aleutian Islands to the Indian Ocean. Only one survived, IJN Kitakami, transformed three times.

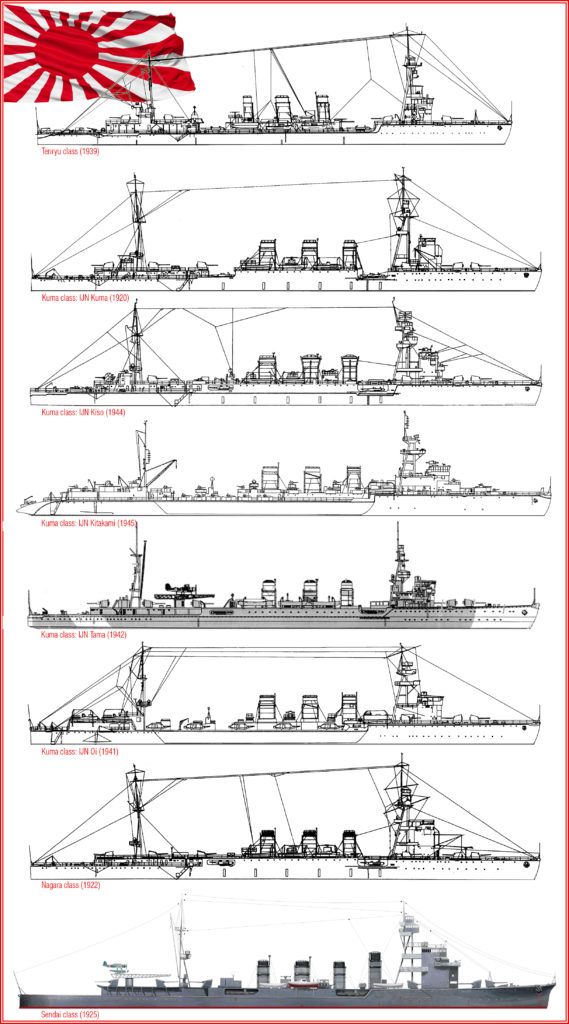

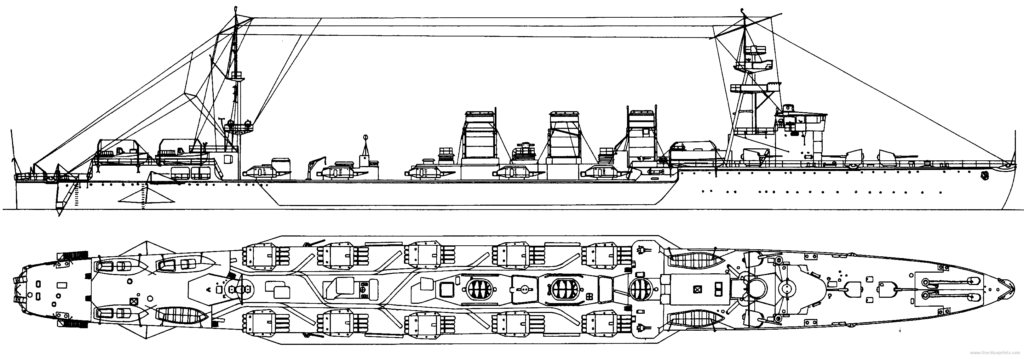

The Kuma class cruisers in their variants compared to the Tenryu, Nagara and Sendai classes

A new serie of light cruisers

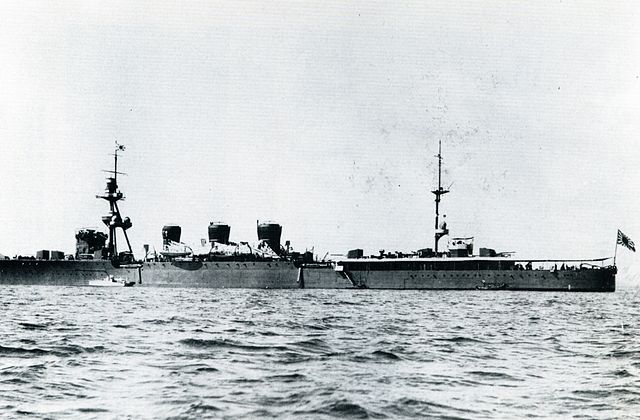

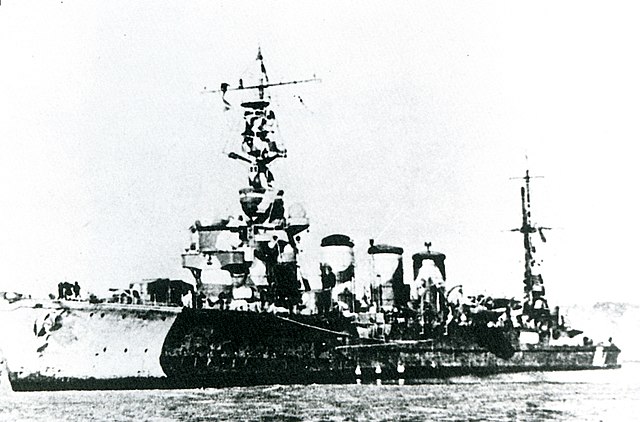

IJN Kuma in Qindao, aft view

By the end of 1917 the admiralty acted a programme for six additional Tenryū-class vessels, and three of a new 7200 ton scout design. They replaced the intermediate 5,500 ton-class vessel. In any case they were tasked to long-range high speed reconnaissance, and command vessel for destroyer/submarine flotilla.

Preceded by the Tenryu, the Kuma represented a brand new step in Japanese light cruiser design. The former basically little more than flotilla leaders, scaled up destroyers. They had a very weak tonnage but head heavier guns and were were a compromise between proper scouts and super destroyers or flotilla leaders. But soon, the IJN admiralty realized they would be outgunned by the USN Omaha class and Dutch Java-class light cruisers than in construction. Also in between a new generation of fleet destroyers was just coming out, and the Tenryu class could not keep up with 33 knots. like the Minekaze class that could reach 39 knots (72 km/h; 45 mph).

So for the new Kuma class cruisers design, engineers were tasked to create a stretched version to house a larger powerplant, and more deck surface for better firepower as well, from four to seven guns. A greater length would also allowed to stack two more torpedo tubes banks (fitting with thoughts about the success of the Battle of Port Arthur in the Russo-Japanese War), that would end in the early 1930s with the “night battle force”, and helped with the developement of new torpedoes, notably the famous “Long Lance”.

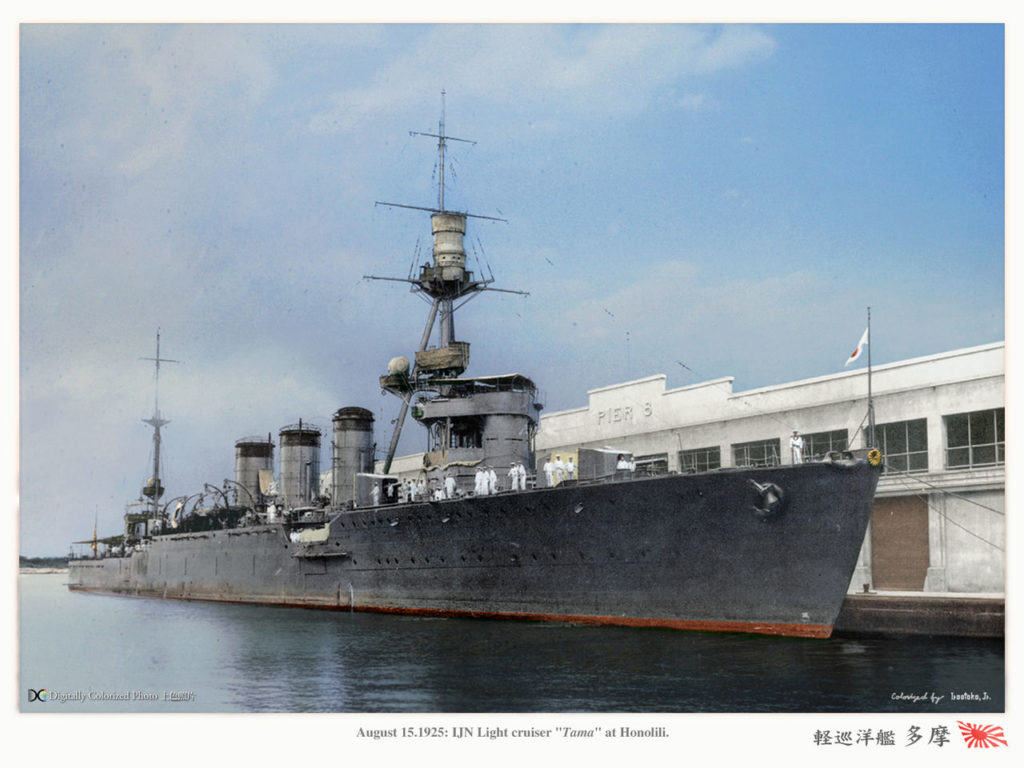

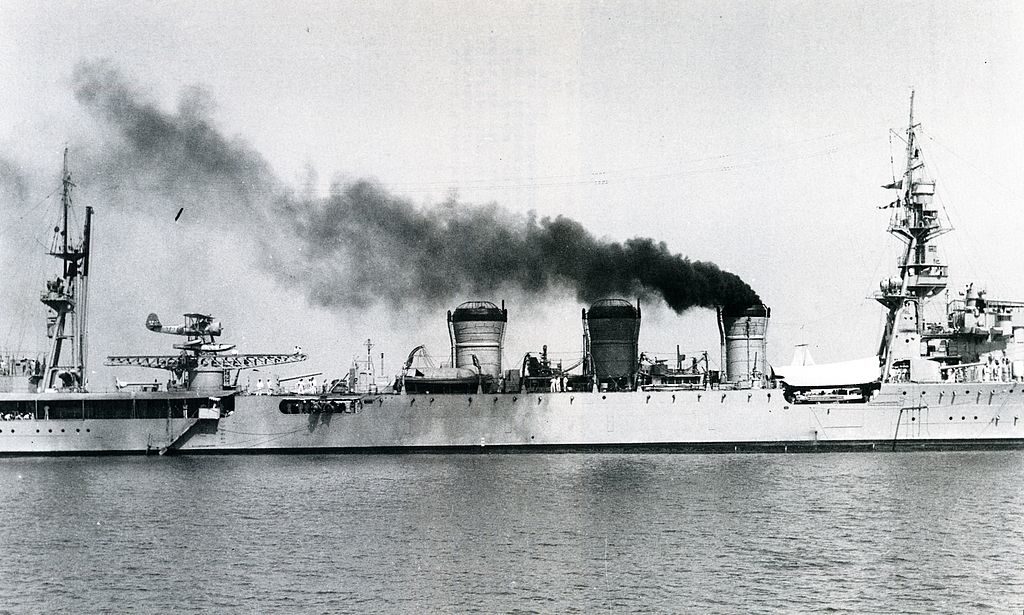

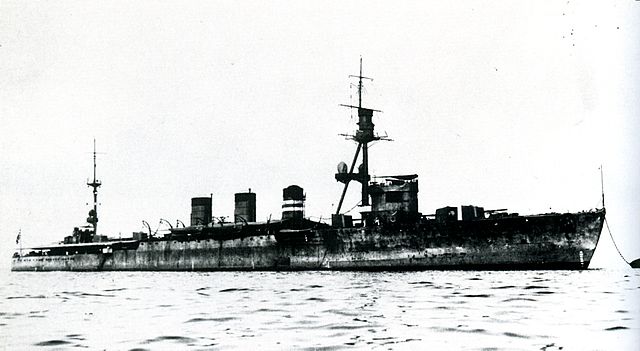

IJN Tama at Honolulu in 1923 – colorized by Irootoko Jr.

Design of the Kuma class

In a general sense, the Kuma class cruisers looked like a streched-out Tenryu class, from 143 to 162 m overall. They still had the same icebreaker bow, round stern, two masts far apart, axial main guns, including the aft main guns mounted high on the quarterdeck, three funnels and a tall bridge with a tripod housing observation tops. However the comparison stops there. The forecastle was extended, slightly enlarge to allow two broadside guns just abaft the mainmast, while the two axial guns were placed in front of the bridge, one facing it. The central section with the funnels was now extended to the broad beam, leaving more deck space. The aft superstructure was stretched enough to mount an axial aft gun, so three aft and seven in all, to compare to just four on the Tenryu.

The two axial triple banks were replaced by four twin on the broadside. And there was enough space, crucially to mount a catapult for a reconnaissance floatplane, not at the origin but in 1934. For all this, the Kuma class cruisers were just 1500 tonnes heavier than the previous Tenryu, at 5,500 long tons (5,588 t) standard and 5,832 long tons (5,926 t) fully loaded versus 4,350 long tons (4,420 t) for the Tenryu. The beam was larger, 14.2 m (46 ft 7 in) versus 12.3 m (40 ft 4 in), so calling to a comparable ratio, but the hull shapes were better studied aft, and the ship was overall more hydrodynamic, and gained three, knot in part due to the more powerful powerplant. Between the added surface, placement of the artillery and fire control platform and searchlights, the Kuma design was appraised and became standard until 1926, as it was followed by the five Nagara class and the slightly larger, four-funnel five Sendai class.

The Kuma class cruisers’ powerplant

Due to the longer hull, the Kuma class cruisers could accommodate four shaft Gihon geared turbines, axial deceleration types, fed by 12 Kampon boilers, for a total output of 90,000 shp (67,000 kW), to compare with 3 shaft Brown Curtis geared turbine engines and 10 Kampon boilers for 51,000 shp (38,000 kW), nearly double. Therefore, between the finer hull lines and output, despite additional tonnage top speed was now above 36 knots (41 mph; 67 km/h) (and not 39 as initially planned, but it proved unrealistic), still way better than 33. Due to the larger hull also, oil tanks had more capacity, allowing a range of 9,000 nmi (17,000 km) at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h), yet again almost double of the Tenryu, at 5,000 nmi (at 14 knots however). Ten out of the twelve boilers burnt heavy oil, and just two a mixture of oil and coal, in case of war. Originally the fat stacks flared out in a trumpet shape, but it differed from ships and after modifications, but it was quite distinctive compared to the tall and slender raked funnels of the Tenryu.

Armament

The five Kuma class cruisers were a net improvement over the previous class, with almost double the artillery, seven instead of four 14 cm/50 3rd Year Type naval guns. These were all individual gun turrets, but their placement meant only six could fire on the broadside. These standard guns used a Breech Welin breech block and had separate-loading, bagged charge, for a shell weighting 38 kilograms (84 lb), HE and AP. It exited the barrel at 850–855 meters per second. The rate of fire was about 6 rpm. The mount could depress to -7° and elevate to +35°, allowing a range of 19,750 m (21,600 yd), but with dispersion and poor accuracy.

At the origin in 1918, the airborne threat was still not taken seriously and the Kuma class were only given two 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type naval guns, slow but with a good ceiling, and two 6.5mm light AA machine guns and nothing in between. At least the previous class had two Type 93 13 mm AA machine guns. This was of course corrected before the war and for those that survived until 1945.

At last, torpedo tubes armament was better, because of two pairs of broadside tubes rather than triple banks. Having only two tubes allowed this disposition, and the banks gained some arc of fire compared to the previous axial banks, due to the ship’s superstructures. These tubes had reloads, eight in all. All five cruisers of the class also could carry 48 mines, stored and moved on tracks running from the amidship structure to the stern.

Protection

As usual the poor parent of this type of ship. Kuma class cruisers’ protection was concentrated in the central portion of the ship with a Belt: 60 mm (or 64 mm) (2.4 in) thick, running for 1/3 of the hull, protecting the vitals, between the forward funnel to the sixth turret, and connected to an armoured deck: 30 (or 32) mm (1.2 in) thick. The other armoured parts are the conning tower, with walls 51 mm thick, the bridge main telemeter, and the radio room at the base of the tripod. Of course, the guns were also protected by enveloping shields, covering their platforms, but the rear was open. Armour was 51 mm thick. The bolted hull was light and structural problems happened, calling for a strengthening and stiffening during the interwar.

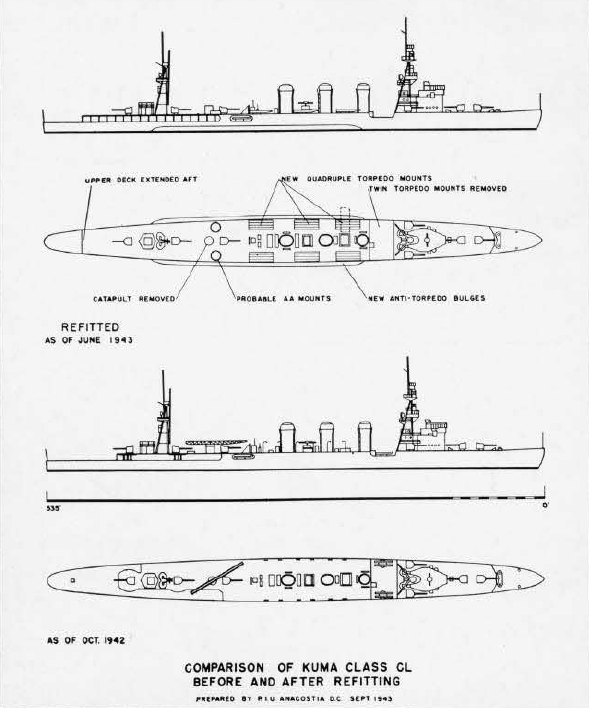

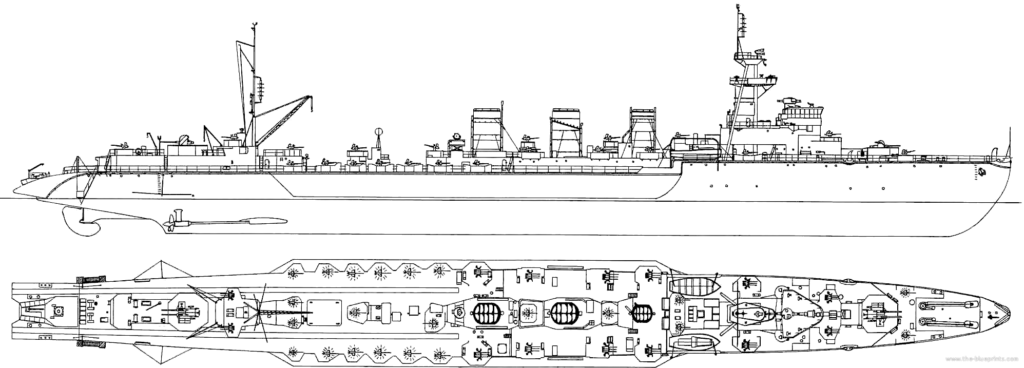

Drawings of the Kuma class in 1920 and after refit in 1934-36.

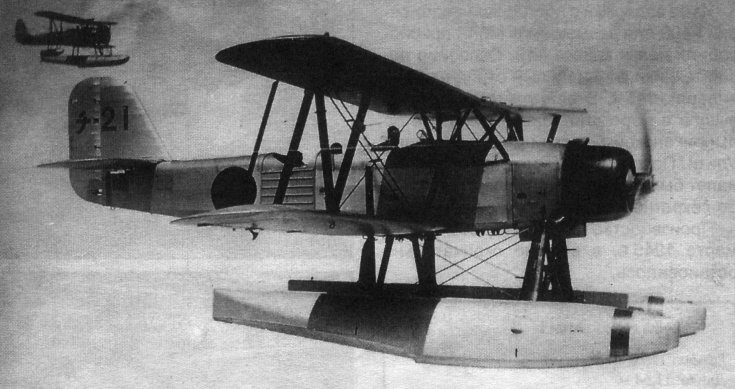

Kawanishi E7K “Alf” (1935) carried by the Kuma and Tama.

Interwar improvements of the Kuma class cruisers

Kuma and the Tama received seaplanes and a catapult in 1934-35, while their rear mast became a tripod, and their hull was reinforced. IJN Kitakami saw her forward funnel heightened while the others two were given new funnel heads. Kiso was also given anti-rain caps on her two forward stacks.The bridge superstructure was enlarged: Renovated, the canvas sides of the bridge were replaced by steel plates. An armoured rangefinder tower was placed behind the bridge with a 11.5-foot (3.5 m) or a 13-foot (4.0 m) rangefinder. The AA was bolstered, receiving four 25 mm guns in 1941, while the 6.5 mm were replaced by 13.2 mm models. while their torpedo tubes were replaced by the new 610 mm Long Lance model. Displacement soared to more 200 tons while top speed fell to 33 knots.

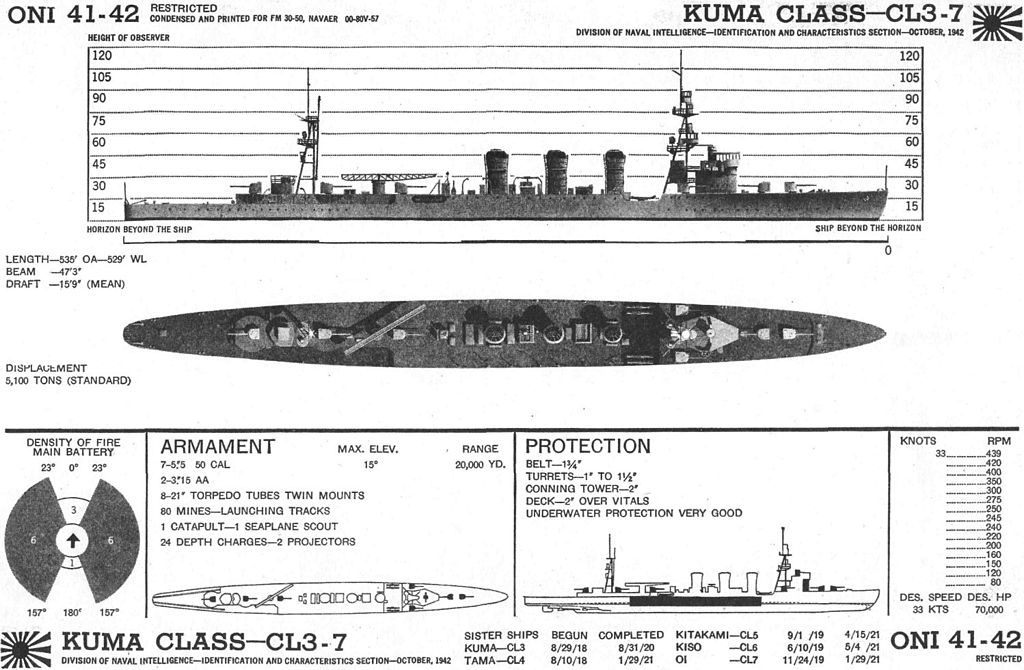

Kuma – ONI

Oi/Kitakami torpedo cruisers conversion

Following the aggressive naval tactics of the admiralty at the time, IJN Oi and Kitakami were converted into torpedo cruisers, a concept fallen into oblivion and refreshed with these modern versions equipped with no less than ten quadruple Type 92 torpedo tubes banks, so 40 in total, mounted on lateral extensions over 60 meters long. The main artillery aft was disposed of. Instead a superstructure large as the beam supported the boats, relocated from the amidship structure, now gone to make room for the torpedo tubes banks. There were reloads in addition, carried from the rear structure via deck tracks to each bank. These ships were quite unique and destined to the “night battle squadron”.

When the rebuilding was completed, both cruisers returned into service in December 1941. IJN Kitakami won later two additional 25 mm twin mounts, and two 5-in (127 mm) AA twin turrets, and in 1943, she lost lost four torpedo benches and was rebuilt again, this time, as an AA cruiser and fast assault carrier: Daihatsu class landing craft were stored on the deck, munted on rails and splashed aft, on a sloped stern extension. The ships also had with depth charge racks and two twin 5-in turrets for and aft, and scores of Type 96 triple-mount 25 mm AA guns replacing the main artillery. The AA was bolstered considerably, for a total of 24 single and twelve triple mounts, so 60 in total. Sources diverged on the conversion of both cruisers or just the Kitakami. The latter was badly damaged in 1944 and rebuilt again to serve in home waters, this time as a Kaiten carrier, eight model 1. She had two Type 89 single gun turrets fore and aft, and a total of 67 Type 96 anti-aircraft guns, (12 triple, and now 31 single). She also carried two depth charge racks. To store ammunitions and reloads, her aft turbine engines were removed and top speed fell to 23 knots. Kitakami survived the war and was broken up in 1947, while Oi was sunk in July 1944, Kiso in November 1944, Tama in October 1944, Kuma in January 1944.

The Kitakami as rebuilt in 1945

Specifications of the Kuma class cruisers (1919)

Displacement: 5,500 t. standard, 5,900 t. Fully loaded

Dimensions: 158,6m wl/162m oa x 14,2 m x 4,8 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Gihon turbines, 12 Kampon boilers, 90,000 bhp, top speed 36 knots

Armour: from 32 to 62 mm

Armament: 7 x 140 mm, 4 x 25 mm AA, 8 x 610 mm TTs (4×2)

Crew: 450

Read more/Src

http://combinedfleet.com/ships/kuma

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kuma-class_cruiser

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1906–1921

Stille, Imperial Japanese Navy Light Cruisers 1941-45

CombinedFleet.com: Kiso Tabular Record of Movement

“Looting under Way by Chinese”. Centralia Daily Chronicle. Zhifu.

Cressman, The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II

Willmott, The Battle of Leyte Gulf

Brown, David (1990). Warship Losses of World War Two. Naval Institute Press.

Boyd, David (2002). The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II. Naval Institute Press.

D’Albas, Andrieu (1965). Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II.

Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941-1945.

Goodspeed, M Hill (2003). US Navy – A Complete History.

Jentsura, Hansgeorg (1976). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869-1945.

Lacroix, Eric & Wells II, Linton (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War.

Morrison, Samuel (2002). New Guinea and the Marianas: March 1944 – August 1944

Tamura, Toshio (2004). “Correcting the Record: New Insights Concerning Japanese Destroyers and Cruisers of World War II”.

Whitley, M.J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia.

Willmott, H P (2005). The Battle Of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action.

Andrew Lambert: Warship, Band 10, Conway Maritime Press

Roscoe, Theodore (1949). United States Submarine Operations in World War II. Naval Institute Press.

Stille, Mark (2012). Imperial Japanese Navy Light Cruisers 1941-45. Osprey.

Ugaki, Matome (1991). Fading Victory: The Diary of Admiral Matome Ugaki, 1941-1945.

Whitley, M.J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia.

The models corner:

Tama camo 1942 1/700, Tamiya. Also Kuma, oi, Kiso.

Tama camo 1942 1/350 Aoshima

http://oisofactory.blog.fc2.com/blog-category-106.html

http://oisofactory.blog.fc2.com/blog-category-33.html

The Kuma class cruisers in the interwar

IJN Kuma in Qindao – colorized by irootoko Jr.

-Kuma (球磨), was launched 14 July 1919, completed 31 August 1920, Tama (多摩) launched 10 February 1920, and completed 29 January 1921 in Mitsubishi in Nagasaki. Kitakami (北上) was built at Sasebo Naval Arsenal, launched 3 July 1920, completed 15 April 1921. Ōi (大井) was from Kawasaki Heavy Industries in Kobe, launched 15 July 1920, completed 3 November 1921. Kiso (木曾) was from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Nagasaki, launched December 1920, completed May 1921. IJN Kuma immediately participated in the Japanese intervention in Siberia against the Bolshevik Red Army, carrying and landings troops. She was based at Port Arthur, patrolling northern China between the Kwantung and Tsingtao. She was refitted in late 1934 with a tripod mast, an aircraft catapult for launching a Kawanishi E7K1 “Alf” with two platforms.

By 1937, Kuma patrolled the China coast and convered the Chinese troops landings central China, under command of Captain Tadashige Daigo (1935-1936) and from December 1937, she served as a flagship for minelaying submarines I-121-I-124 based in Tsingtao until until 1938.

-IJN Tama covered landings in Siberia and in 1925, made a diplomatic voyage to San Pedro US with the remains of US Ambassador to Japan, Edgar Bancroft. In 1932 she patrolled the northern coasts of China and from 1933-34 cover further landings in central China. On 10 January 1935 she was visited by the German naval attaché in Tokyo, Captain Paul Wenneker.

-IJN Kitakami was based from 1931 at Mako, in the Pescadores Islands (Captain Jinichi Kusaka) and later under Captain Tomoshige Samejima until March 1934. When the Second Sino-Japanese War started she covered in central China.

-IJN Oi in 1928-1931 was a training ship at the IJN Academy in Etajima, Hiroshima (Captain Nishizō Tsukahara and Masaichi Niimi). From 1932, Ōi patrolled the China coast and returned to training in 1933-1937. As the Second Sino-Japanese War started she cover landings in central China before returning to training until late 1939. On 25 August 1941 it was decided to convert her as a torpedo cruiser.

-IJN Kiso received a forward and an aft flat superstructure and rotating floatplane take-off platform for experiments and tests. She cover landings of Japanese troops in Siberia against the Red Army and was based at Port Arthur, patrolling the coast between the Kwantung and Tsingtao. In February 1929, she was stationed at Zhifu during the Warlord Rebellion. In April 1939, she gun-saluted USS Astoria in Yokohama, carrying the remains of ambasador Hiroshi Saito. Her carrer was spent until 1941 in patrols off the China coast and training in home waters.

The Kuma class in action

IJN Kuma

IJN Kuma in 1935 off Tsingtao detail

Invasion of the Philippines:

In April 1941, Kuma was assigned to Vice Admiral Ibo Takahashi’s Cruiser Division 16, 3rd Fleet. On 8 December 1941, the invasion of the northern Philippines began. Kuma departed from Mako island in the Pescadores, in company of IJN Ashigara, Maya and the destroyers Asakaze and Matsukaze. On 10–11 December, she covered the landings at Aparri and Vigan, while being attacked by five USAAF B-17 (14th Sqn) without hit. On 22 December she covered the Lingayen Gulf landings. By January 1942, Kuma joined Vice Admiral Rokuzō Sugiyama’s 3rd Southern Expeditionary Fleet. She patrolled Philippine waters 10 January-27 February 1942 and in March, covered the invasion of the southern Philippines: At Cebu harbor she sanking two coastal transports. She covered the landings at Zamboanga (Mindanao) two days later on 3 March. The Kuma’s Special Naval Landing Forces later rescued about 80 Japanese nationals. During the night, Kuma went on a rampage and sent to the bottom twelve transport vessels (Sulu Sea, Cebu). 9 April 1942: Still in Cebu, Kuma and the TB Kiji are attacked by PT-34 and PT-41 and Kuma is hit in the bow by a light Mark 8 Torpedo fired, a dud.

On 10 April 1942, Kuma covered landings on Cebu (35th Infantry Brigade, 124th Infantry Regiment) and Panay six days later (Kawamura Detachment, 9th Infantry Brigade HQ, 41st Infantry Regiment), and on 6 May, Corregidor. She patrolled Manila waters until 12 August 1942 before being redeployed.

Dutch East Indies and New Guinea campaigns:

Refited in Kure by September 1942, Kuma was back to Manila on the 20, sent to Vice Admiral Shirō Takasu as part of the Second Southern Expeditionary Fleet targeting the Dutch East Indies. She stopped in Hong Kong to embark troops (38th Infantry Division), to Rabaul (10 October). She was patrolling the Celebes under command of her new Captain, Ichiro Yokoyama, wcarryiong troops to varying locations until April 1943. Until May,she was in refit at Seletar NyD (Singapore) and resumed patrols in the Dutch East Indies until late June. On the 23 she was attacked off Makassar by 17 B-24 Liberator bombers (319th Squadron/90th BG, 5th AF), in company of other cruiser but all missed and they had little damage.

A day after, Kuma became the flagship of Cruiser Division 16, and with Kinu she sailed from Makassar for patrols off the Dutch East Indies, until 23 October. After a refit in Singapore (a gun removed, catapult and derrick, new triple Type 96 25-mm AA fitted for (2×3, 2×2) total). She departed on 12 November to join Port Blair in Andaman Islands, and ended in Burma on 9 January 1944. Three days later, she sailed with Uranami for an ASW exercise when she was spotted by HMS Tally-Ho (from Trincomalee, Ceylon). Seven-torpedoes were launched from 1,900 yards, spotted by Kuma’s lookouts and despite a hard turn, she was hit starboard aft by two. Fire started and she sank by the stern around 16 km off Penang. Uranami rescued many survivors, but 138 went down including the captain.

IJN Kuma 1930 off Tsingtao

IJN Tama

Japanese cruiser Tama in 1942 in Arctic camoufage

Northern Pacific:

On 10 September 1941, Tama was the flagship of Cruiser Division 21, 5th Fleet (Vice Admiral Boshirō Hosogaya) with Kiso. Both departed for the north of Hokkaidō, repainted in Arctic white camouflage on 2 December. They patrolled the Kurile Islands, but were damaged by heavy weather, and drydocked until January 1942. On the 21, they departed Yokosuka for Hokkaidō, but recalled as Task Force 16 (USS Enterprise) raised Marcus Island on 5 March. Tama was now with the 1st Fleet (Hyūga and Ise), which was sent to search for Admiral Halsey, without success. In April, she heard about the Doolittle Raid and tried to catch up with Halsey’s force, patrolling in May northern waters. She was part of “Operation AL” (Attu and Kiska), the Aleutian Islands campaign.

She landed forces and was back to Mutsu Bay in June 1942 but quickly returned to Kiska, and patrolled until 2 August. She stopped at Yokosuka and carried back the Attu garrison to Kiska, and other reinforcements to Attu, patrolling the Aleutians and Kurile, down to Hokkaidō until 6 January 1943. She was refitted at Yokosuka until February 1943, and was assigned to the Ōminato Guard District to Kataoka and Kashiwabara until 7 March. She later this month joined Vice Admiral Hosogaya’s Fifth Fleet (Nachi, Maya, Abukuma 5 DDs) escorting a troopship convoy to Attu. The Battle of the Komandorski Islands followed on 26 March, with TG 16.6 (USS Richmond, Salt Lake City, 4 destroyers). The battle lasted for 4h. Tama fired 136 shells and four torpedoes, received two hits (catapult) but Nachi was more severely damaged and the convoy retired. Hosogaya was relieved of command, replaced by Vice Admiral Shiro Kawase. Staed on station off Kataoka and was sent to Maizuru for a refit in May, back on the 23 for guard duties until July. She was dismissed from “Operation Ke-Go” because for her engines, and patrolled the Kuriles until 30 August.

Southern Pacific:

After a refit at Yokosuka, Tama carried troops and supplies to Ponape (Caroline Islands) on 15 September 1943. She stopped at Truk, then was back to Kure, and sent to Shanghai in October. When at Rabaul, she was attacked by RAAF Bristol Beaufort bombers on 21 October and had to be repaired after severe near-misses. On 27 October, she was refitted in Yokosuka, same as Kuma but with a twin 5-in HA fitted, and more Type 96 25-mm AA guns (4×3, 2×2, 6×1) plus a type 21 air search radar fitted. She was out by 9 December.

Departing on 24 December she patrolled northern waters until 19 June 1944, stopped at Yokosuka in June, and carried troops to Ogasawara islands, (two runs). By 30 August, she became flagship of DesRon 11 (Combined Fleet) in place of Nagara.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

On 20 October 1944 she was part of Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa Northern Mobile (“Decoy”) Force. She was in the Battle off Cape Engano on 25 October, attacked by TF38 planes and Tama was targeted by TBM Avenger (VT-21, VT-51), hit by a Mark 13 torpedo in the No. 2 boiler room. She managed to retire from the battle, escorted by Isuzu and then the destroyer Shimotsuki, and alone at 14 kn to Okinawa. Northeast of Luzon however she was spotted by USS Jallao by radar, evaded three torpedoes, but three torpedoes later hit her aft section. She broke in two, and very quickly with all hands.

IJN Kitakami

Kaiten Type-1 launch test from starboard of Japanese cruiser Kitakami

On 25 August 1941 kitakami was sent to Sasebo for her conversion as a torpedo cruiser. This short-lived IJN program was only ported to two ships, with IJN Oi. The goal was to have a pplatform to launch massive volleys of the deadly 61 cm (24 in) Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo (often seen as the best torpedo of W2) in accordance to the IJN staff “Night Battle Force”. Reconstruction was completed by 30 September 1941. IJN Kitakami then was assigned to the Japanese First Fleet, Cruiser Division 9. She escorted the Combined Fleet’s battleships from Hashirajima to the Bonin Islands and back to Japan when the attack on Pearl Habor took place. In January-May 1942, she trained in home islands waters.

The cruiser was sent in the Aleutian screening force during the Battle of Midway. She was used a fast transport in and of sorties to Rabaul, the Solomon Islands at large and New Guinea. On 21 November 1942 her division was disbanded and she was assigned directly to the combined fleet.

From March 1943, she joined the Southwest Area Fleet, and the cruiser division 21, escorting convoys and transporting troops and supplies. On 23 June 1943, off Makassar with Kuma she was bombed but missed by Consolidated B-24 Liberators. She was reffited in Singapore in Sept. 1943 and escorted more convoys to the Nicobar Islands, and the Andaman Islands in October.

On 27 January 1944, she was torpedoes by HMS Templar and severely damaged. She was back to Japan for repairs and later conversion to a kaiten carrier, but never served due to lack of fuel at that stage in the war. She was attacked on 19 March 1945 by TF 58 in Kure, but not targeted nor damaged. Afterwards in July 1945, she received 27 additional single Type 96 25-mm AA guns but was attacked again on the 24 by TF 38 and thirty-two crewmen were killed by strafing. She stayed idle in home waters in August and was used as a tender for repatriation ships postwar, scrapped on 10 August 1946.

IJN cruiser Kitakami, as converted as a torpedo cruiser in 1941, with forty 610 mm (24 in) torpedo tubes (10×4).

IJN Ōi

IJN Oi in 1923 at Kure

After conversion, Ōi joined CruDiv 9 (1st Fleet). In In January 1942 she was visited by Staff Rear Admiral Matome Ugaki, which disapproved the conversion and urged a revision of tactics. Ōi escorted transports between Hiroshima and Mako in the Pescadores Islands until April 1942. In May, she was in the Aleutian screening force during the battle of Midway. In August–September, Ōi and Kitakami were converted into fast transports, at Rabaul, the Solomon Islands and New Guinea and in March 1943 as a convoy escort in the Southwest Area Fleet. In October-December, Ōi carried troops and supplies from Truk and Manila to Rabaul and Buin (Bougainville) assigned directly to the Combined Fleet. In December she was in Kure for maintenance and in January 1943, ferried troops to New Guinea, the 20th Infantry Division to Wewak, via Palau and the 41st Infantry Division in February. On 15 March, Ōi joined the Southwest Area Fleet for escort duties to New Guinea and Ambon-Kaimana in May 1943, vombed and near-missed of Makassar on 23 June by B24s. In July, she joined CruDiv 16, based at Surabaya as a guard ship. She patrolled the Java Sea, and from August 1943 to January 1944 with her sister ship Kitakami she made transport runs from Singapore and Penang to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

In February, Ōi, Kinu and 3 destroyers escorted Tone, Chikuma and Aoba for commerce raiding in the Indian Ocean. In May, Ōi transported troops between Tarakan, Palau and Sorong, before resuming patrols in the Java sea in June. In July, she was heading for Manila when she was spotted on 19 July, in the South China Sea, south of Hong Kong by the Gato-class submersible USS Flasher. She was torpedoed by her stern tubes, there were two hits, including a dud, but the second made a breech portside aft. Her aft engine room was flooded and she was immobilized, leaving USS Flasher the opportuniy of manoeuvering to lauch its bow tubes, but missed. Nevertheless, Oi sank at 17:25 by the stern, and the destroyer Shikinami rescued all but 153 men from the crew. She was only stricken on 10 September 1944.

IJN Kiso

IJN Kiso in 1942 in Arctic camouflage

In November 1941, Kiso joined Cruiser Division 21, 5th Fleet (Vice Admiral Boshirō Hosogaya). She was painted in Arctic camouflage for northern operations and in December she was patrolling the Kuril islands. Severe weather damaged her hull and she was repaired in Yokosuka. In January-April 1942, she patrolled northern waters with Tama and after the Doolittle Raid, tied to catch TF16 however both were attacked by planes from USS Enterprise, suffering little damage. In May 1942, she escorted Kimikawa Maru to Kiska and Adak. On 28 May she took part in the Battle of the Aleutian Islands (Operation AL). When troops were landed on Kiska, 7 June 1942, she was covering. Three days later off Kiska, she was attacked by six USAAF B-24 Liberator, but undamaged. On 14 June 1942 this was a group of PBY Catalina flying boats (near misses), she was back in Mutsu Bay on 24 June. Four days later she escorted a convoy to Kiska patrolled in case of an American counter-attack. She was refitted in Yokosuka until 2 August 1942, and covered the transfer of the Attu garrison to Kiska in August 1942. These missions in the Aleutian went on until March 1943.

Kiso in harbour

On 28 March, she passed under command of Vice Admiral Shiro Kawase (5th Fleet), and received a drydock refit in April 1943 (notably her 900 mm (35 in) searchlights were replaced Type 96 1,100 mm models, 2 Type 96 twin-mount 25-mm AA guns added and a Type 21 air-search radar. On 11 May she departed with the DDs Hatsushimo and Wakaba to escort Kimikawa Maru carrying floatplanes of the 452nd Kōkūtai to Attu, cancelled en route as Attu fell to US Forces. On 21 May 1943 she covered evacuation of Kiska and again in July 1943, then patrolling the area until late August. On 15 September 1943, she was reassigned in the south Pacific, ferrying troops from the Caroline Islands to Truk, and was in Kure on 4 October 1943. On 12 October 1943, Kiso and Tama ferried troops in Shanghai and was near-missed en route by the submarine USS Grayback. She ferried troops to Rabaul and on 21 October 1943, attacked by RAAF Bristol Beaufort bombers. She took a direct hit by a 250 lb (113 kg) bomb and was sent to Maizuru for repairs. She was then modified (two 140-mm gun mounts removed, dual 127-mm HA gun mount installed, as well as 3 triple, 6 single Type 96 25-mm AA, bringing the total to 19.

On 3 March 1944, she was back in northern waters and on 30 June 1944, Kiso and Tama carried reinforcements to Ogasawara Islands. In August she was in the Seto Inland Sea (training and guard duties), and during the invasion of Leyte (from 20 October 1944) she departing Sasebo with IJN Jun’yō and DDs Uzuki, Yūzuki and Akikaze. Spotted 160 miles (260 km) west of Cape Bolinao (Luzon) by the submarine USS Pintado. There was a cluster there, with USS Jallao and Atule, Haddock, Halibut and Tuna. Pintado fired its bow torpedoes, one Japanese destroyer interposing and taking some. Kiso, joined later Tone, Haguro and Ashigara, 3 DDs behind the Yamato, Kongō and Nagato, and Yahagi back to Japan. Kiso however returned to Manila, becoming the flagship of the Fifth Fleet. On 13 November 1944, Kiso was ordered back to Brunei with Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima on board. She was soon spotted and attacked by more than 350 carrier planes (TF38) and took three bombs hit to starboard. She sank in shallow waters 13 km (8.1 mi) west of Cavite but Captain Ryonosuke Imamura and 103 of her crew survived. Kiso was stricken on 20 March 1945.

Japanese cruiser Kiso in 1942 arctic camoufage

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign