The two Suma-class cruisers (Suma, Akashi) were protected cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) which took part in the boxer rebellion, Russo-japanese and the first world war. They were lightly armed and armored for the time, but this small size and simple design made faster their construction. They were also high speed and for this, were found useful in all their operations. Cherry of the cake, they were among the first cruisers entirely designed and built in Japan, at the newly established Yokosuka Naval Arsenal. They had longer careers, ending in 1928-1930. https://naval-encyclopedia.com/ww1/japan/suma-class-cruisers.php #ww1 #ijn #imperialjapanesenavy #japaneships #cruiser #russojapwar #revoltboxer #suma #akashi

Development

Before even the first Sino-Japanese war in 1894, the Imperial Japanese Navy was launched in a purchasing and building spree for new ships. Since 1885, French influence was considerable on Japanese naval matters, with French engineer Emile Bertin staying for years in Japan to establish its first naval yard and arsenal (Yokosuka) and naval academy. But this came also with a somewhat poisoned gift, ideas of the “young school” about asymetric warfare using armoured cruisers and torpedo boats. Prior to the war with China, Japan aqcuired the three 4,700-ton Matsushima and Itsukushima cruisers made in France, the third, Hashidate, built in Yokosuka, three coastal warships of 4,278 tons, two small cruisers (Chiyoda, 2,439 tons UK, Yaeyama, 1,800 tons, Yokosuka), the light cruiser Chishima, built in France, a 1600 tonnes frigate at Yokosuka and acquired 16 54-ton torpedo boats built in France by Creusot in 1888, but assembled in Japan.

The Yokosuka Naval Arsenal had experience with Hashidate and Akitsushima, albeit with assistance from French naval engineers and imported components but the loss of IJN Unebi, by december 1886 during her initial voyage from Bordeaux to Japan, sinking likely due to stability problems, somewhat revised the naval staff opinion about this influence. These concerns were definitely entrenched after the relatively poor result of the war with China, despite the victory. IJN Suma was partly revised because of battle reports during construction.

But before it came to this, the admiralty wanted to test the ability of Yokosuka to deliver a truly Japanese design, with limited French influence and parts: These were the two modest Suma class cruisers. Despite the feat achieved, Suma still took four years of construction, and still had questionable stability and seaworthiness. But they were entirely conceived at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, to get rid gradually of foreign powers assistance for modern warships, and were the first serious test of an all-Japanese design with all-Japanese materials. Her construction gave Japanese designers valuable experience, applied to her sister Akashi and later, larger and more powerful cruisers. Dependence on battleships (purchased from Great Britain) would linger however until a few years before WWI, but this was a more complex endeavour overall.

IJN Suma in the end was ordered in 1891, launched 9 March 1895, completed 12 December 1896, and her sister Akashi was ordered in 1893, launched 18 December 1897 and completed 30 March 1899 but she developed engines issues. Nevertheless, both were considered successful enough for a domestic design and had long careers.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

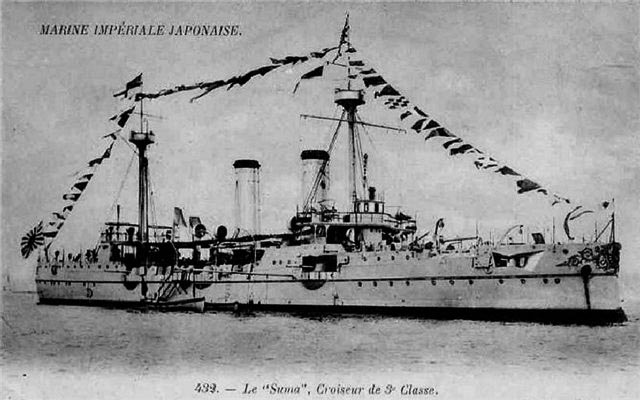

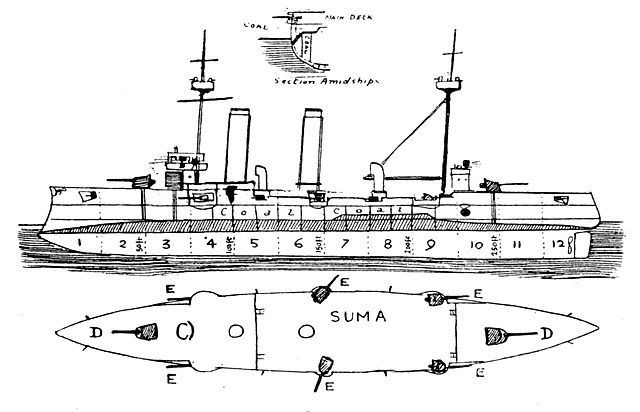

Both in size and layout as well as for their armaments, the Suma-class cruisers were a near repeat of IJN Akitsushima. As a result the ships were still relatively small at 2,657 long tons (2,700 t) displacement for 93.5 m (306 ft 9 in) long overall, with a bow and pointed stern, a forecastle and aft deck, and a beam of 12.3 m (40 ft 4 in), limited draught of 4.6 m (15 ft 1 in). Their metacentric height was thus low. Being smaller than Akitsushima, armament was reduced due to stability concerns already but it was not sufficient and they rolled badly.

Akashi differed by her relocated torpedo launch tubes to the stern, high foremast with radio antenna, no fighting top, making it her appearing sleeker.

They looked like also as average British Vickers export cruisers with their two tall funnels and balanced, symmetrical hull.

Protection

They had an all-steel, double-bottomed hull and an armored deck at the waterline, which was subdivided below by many watertight bulkheads. The armor used the latest Harvey steel which process was adopted at Yokosuka, and as most protected cruisers it only covered vital areas, boilers, magazines, steering and VTE engines. The armoured, “turtleback” deck was protected by 50 mm (2 in) on its slopes and 25 mm (1 in) on its flat section, but the gun shield for the main gun had 115 mm (4.5 in) in thickness.

Powerplant

They had two vertical triple steam reciprocating engines fed by a total of eight cylindrical boilers on Suma, nine single-ended boilers on Akashi for a total of 8,500 hp (6,300 kW) and a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h), a range of 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) based on 544 tons of coal in normal peacetime load. Most underwater void spaces below the waterline used for compartimentation could be filled as well.

Armament

This was a mix of British and French Armament:

Main: 2x QF 6 inch /40 naval guns

Main battery was two QF 6 inch /40 naval guns, one on the forecastle, one in the stern. Range up to 9,100 metres (4.9 nmi), nominal firing rate of 5.7 shots/minute.

Secondary: 6 × QF 4.7 inch Gun Mk I–IV

The six QF 4.7 inch Gun Mk I–IV were mounted in sponsons on the upper deck. Protection was poor. Range was up to 9,000 metres (9,800 yd) with a nominal firing rate of 12 shots/minute so theyr complemented well the main guns. Gunners were drilled to work in concert, secnndaries concentrating on destroying the enemy’s armament and superstructure with HE, while the two main guns concentrated on the vitals with AP rounds.

Tertiary

The ten QF 3 pounder Hotchkiss guns (range of up to 6,000 metres/6,600 yd, nominal firing rate 20 shots/minute) were mounted, four on the upper deck, two on the poop, two on the after bridge, one each on bow and stern casemates.

They also came initially with four 1-inch Nordenfelt guns. But they were later replaced by four 7.62 mm Maxim machine guns.

Torpedo tubes

The two 356 mm (14.0 in) torpedoes were mounted on deck. On Akashi, they were relocated at the poop.

Although this armament looked reasonable on paper, we have to look at the low draught, beam and relatively tall hull to appreciate how this design remained top-heavy, which created issues with seaworthiness and stability. The obvious choice as to relocate the secondary battery one deck lower to improve the center of gravity but this was not enough, and replacing their heavy guns for 4.7-in ones would have certainly cure part of the problem.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 2,657 long tons (2,700 t) |

| Dimensions | 93.5 x 12.3 x 4.6m (306 ft 9 in x 40 ft 4 in x 15 ft 1 in) |

| Propulsion | 2-shaft VTE, 8 boilers; 8,500 hp (6,300 kW) |

| Speed | 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h) |

| Range | 11,000 nmi (20,000 km) at 10 kn (19 km/h) |

| Armament | 2× QF 6 in/40, 6× QF 4.7 in, 10× QF 6 pdr H, 4× QF 3pdr H, 4× Maxim MG, 2× 15 in TTs |

| Protection | 1-in flat, 2 in slope, Gun shield 4.5 in |

| Crew | 256 |

IJN Suma

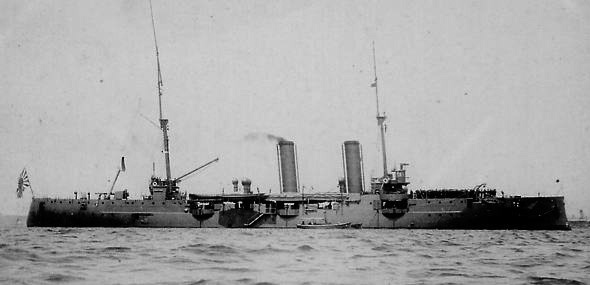

IJN Suma

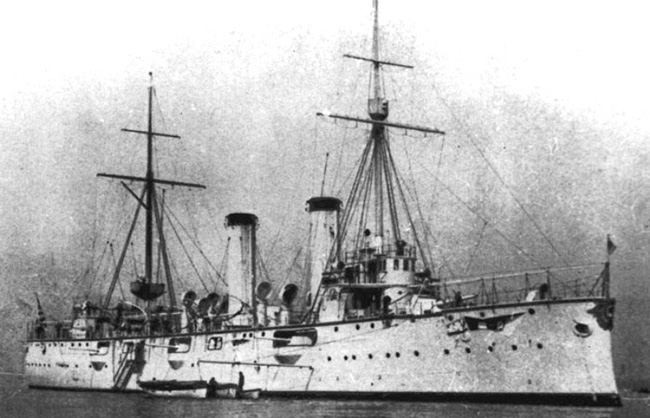

Suma in 1897

IJN Suma was Completed too late for the First Sino-Japanese War, and she was sent first to to Manila, Philippines as an bervser and to saveguard Japan interests and citizens there during the Spanish–American War. From June to July 1900 under captain Shimamura Hayao she supported the Japanese landing to Tianjin, northern China during the Boxer Rebellion, in the Eight-Nation Alliance.

At the start of the Russo-Japanese War, Suma was in the Takeshiki Guard District, Tsushima island. From there she patrolled the Korea Strait hoping to intercept the Russian cruiser squadron based in Vladivostok trying to reinforce Port Arthur.

On 18 February 1904 she was ordered by Admiral Itō Sukeyuki to Shanghai with Akitsushima to survey the disarmament of the Russian gunboat Mandzhur under neutrality, laws, until she was properly scuttled on 31 March.

In early May 1904, Suma covered landings of the Japanese Second Army in Manchuria and on 15 May assisted the rescue of survivors from Hatsuse and Yashima (hitting naval), then joined the blockade of of Port Arthur. On 7 June, Suma, Akashi, a gunboat and destroyers entered the Gulf of Bohai, covering landings of the Second Army, shelling shore installations and the railway line to prevent reinforcements.

She was to take part in the Battle of the Yellow Sea but experience scores of mechanical failures, until ordered to withdraw and join the 5th Division with the old Matsushima, Hashidate and Saiyen on the nort line of battle. But as the Russian squadron turned back she became fac to face to the Askold and Novik. They exchanged fire, with at least one or more hits, but she could not prevent their escape and later returned to the Japanese repair station in the Elliott Islands. Once fixes were made she joined back the blockade of Port Arthur.

In February 1905, she escoted transports in the Sea of Japan, notably covered much needed artillery and reinforcements for the IJA.

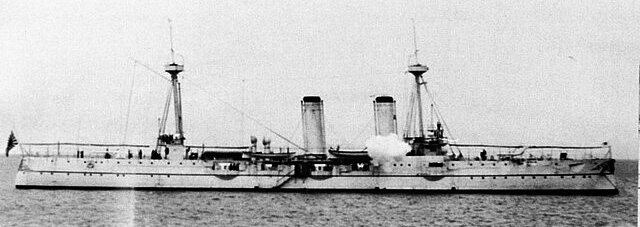

Suma in 1905

The Battle of Tsushima on 27 May 1905 saw her flagship of the 6th Division (Rear Admiral Tōgō Masamichi) and with IJN Chiyoda she started shadowing the incoming second Russian Pacific fleet towards the Tsushima Strait. Suma and Chiyoda attacked their left flank and captured two transports and the hospital ships Orel and Kostroma. Later in the day, they went for blood, duelling with the cruisers Oleg, Aurora, as well as the antiquated Vladimir Monomakh and Dmitrii Donskoi. They made numerous hits and also completed the destroction of the already crippled battleship Knyaz Suvorov and repair ship Kamchatka. Suma took a single hit and many nea rmisses, plus shrapnel but only reported three injured. On 28 May she reported the surrender of Rear Admiral Nikolai Nebogatov and tried to catch, but failed to join the cruiser Zhemchug.

Afterwards, Suma was sent to cover landings of the 13th Division on sevral points and secure lighthouses and port facilities to prevent later any reinorcement from Vladisvostok. In August, she patrolled the southern coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula and Kommandorski Islands. She was sent to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky in order to rescue retired Lieutenant Shigetada Gunji arrested by Russian authorities and later the United States-flagged steamer Australia for war contraband.

Postwar in Yokohama she took part in the victory naval review and was overhauled in 1908, her cylindrical boilers replaced with Miyabara water-tube boilers.

On 28 August 1912, she became a 2nd class cruiser.

In 1916, she was based at Manila, patrolling sea lanes in the South China Sea/Sulu Sea, from Borneo to the Malacca Straits, looking for German commerce raiders and U-boats. She ended in Singapore with Yahagi, Niitaka and Tsushima with destroyers and later was sent to protect Australia and New Zealand, her contribution to both the entente and Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

She became a 2nd-class coastal defense vessel from September 1921. With the Washington Naval Treaty she was demilitarized due t tonnage issues, and became an utility vessel on 4 April 1923, striken from the list and used as such as guard ship at Sasebo until sold for BU on 1928.

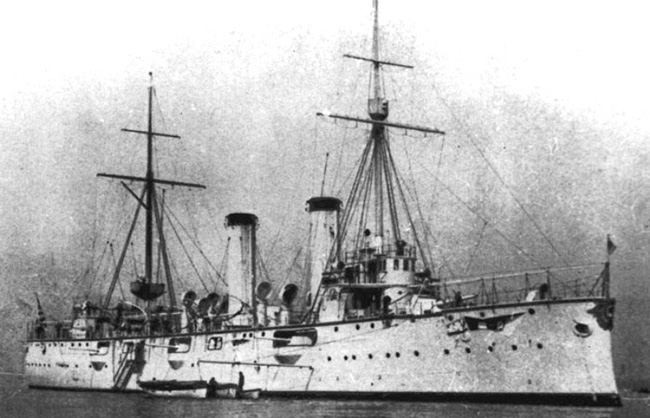

IJN Akashi

IJN Akashi

From March 1899, Akashi multiplied fixes for her numerous mechanical problems at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal until January 1900, and in May, or to Sasebo by July 1900. She sailed out from July to November 1900, to support the assault on Tianjin during the Boxer Rebellion. Just arrived back she had her boilers repaired at Kure. From April to October 1901, she patrolled southern China, before more fixes in Kure. From February 1902 she retruned to China but soon back again as three of her boilers could not hold pressure, she slowed to 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph). She was back May, but back in June. In August 1902 the admiralty declared her “unfit for front-line service” so she was transferred to the reserve fleet.

From March 1899, Akashi multiplied fixes for her numerous mechanical problems at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal until January 1900, and in May, or to Sasebo by July 1900. She sailed out from July to November 1900, to support the assault on Tianjin during the Boxer Rebellion. Just arrived back she had her boilers repaired at Kure. From April to October 1901, she patrolled southern China, before more fixes in Kure. From February 1902 she retruned to China but soon back again as three of her boilers could not hold pressure, she slowed to 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph). She was back May, but back in June. In August 1902 the admiralty declared her “unfit for front-line service” so she was transferred to the reserve fleet.

It was decided to have her completely overhauled at Kure from March 1903, and she became a training vessel with instructors and cadets from the Imperial Naval Engineering Academy, cruising off China and Korea and stopping at Fuzhou, Shanghai, Yantai, Inchon, Busan and Wonsan and back to Sasebo in September 1903. By October-November 1903 she took part in IJN combat maneuvers and then escorted Japanese cable laying vessels for the first submarine telegraph cable between Sasebo and Incheon, Korea on 8–17 January 1904. After her speed trials by January 1904, she reached 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h; 22.4 mph), her designed speed.

Akashi was in the Chinkai Guard District, Korea when the Russo-Japanese War commenced. She was stationed off the southeastern coast of the Korean Peninsula, operating at telegraphic relay station but still was detached to take part in the Battle of Chemulpo Bay in the line of battle behind IJN Takachiho, destroying by gunfire the cruiser Varyag and gunboat Korietz. She was not hit.

In April-May, she escorted transports of the Second Army to Manchuria and destroyer squadrons from Japan. On 15 May she assisted the rescue of Hatsuse and Yashima and joined the blockade of Port Arthur.

On 16 May, Akashi, Akitsushima and Chiyoda shelled Russian troops and installation from the Bohai Gulf but it was stopped due to dense fog on 17 May, seeing the collision of the gunboats Ōshima and Akagi. On 7 June, Akashi, Suma, the gunboat Uji, and destroyers entered the Gulf of Bohai again, to assist the Second Army landing and shell fortifications as well as the railway line. On 10 August, she took part in the later Battle of the Yellow Sea in pursuit of Askold and Novik, but they escaped.

On 10 December, she hit a naval mine off Port Arthur, which flooded several compartments, and she listed to starboard, with a dufficult rescue attempt due to ice and fog. Her crew orked wonders, stabilized her, and she could sail to Dalian escorted by Itsukushima and Hashidate. There she was patched up.

She took part in the Battle of Tsushima on 27 May 1905 as part of the 4th Combat Detachment under Rear Admiral Uryu Sotokichi with Naniwa, Takachiho, and her sister Suma. She took part in gunnery duels with Oleg, Aurora, Vladimir Monomakh and Dmitrii Donskoi and finished off Knyaz Suvorov and Kamchatka. Unlike her sister which remained unscavedn she took five rounds, destroying her smokestack, killing three crewmen, injuring seven. She joined in the search and took part in finishing off Dmitrii Donskoi and Svetlana. She also boarded and captured the Russian destroyer Biedovy, sent to Sasebo on 30 May.

On 14 June she was back to the Takeshiki Guard District, patrolling the Korea Strait. She had a short overhaul at Kure Naval Arsenal in 4–29 July. On 10 October she intercepted the German-flagged steamer M Struve smuggleing rice, salt, bread and flour to Vladivostok, sent as prize to Sasebo. In Yokohama she took par tin the victory naval review.

In 1912 she was re-boilered again with nine Niclausse boilers.

In World War I she joined the 2nd Fleet at the Battle of Tsingtao. In 1916, she patrolled sea lanes in searhc of German commerce raiders, based at Singapore.

She was then sent to the Mediterrenan via the Suez canal, and arrived at Malta. She served in 2nd Special Squadron as flagship (Rear-Admiral Kōzō Satō) leading the 10th and 11th Destroyer Units in Malta from 13 April 1917. Later the 15th Destroyer squadron arrived on 1 June 1917 and she spent the rest of her time in escort duties, relieved by the cruiser Izumo to rejoin Japan, seeing little activity until the end of the war.

Postwar she became a 2nd class coastal defense vessel (1 September 1921) but was stricken on 1 April 1928 and ended as target ship for early Japanese dive bombers south of Izu Ōshima, on 3 August 1930. Her main mast can be seen at the Japan Maritime Self Defense Academy at Etajima, Hiroshima, used to raise the flag for ceremonies.

Read More/Src

Books

Chesneau, Roger (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

Evans DC, Peattie MR (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

Howarth, Stephen (1983). The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun: The Drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895-1945. Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11402-8.

Jane, Fred T. (1904). The Imperial Japanese Navy. Thacker, Spink & Co.

Jentsura, Hansgeorg (1976). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869-1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

Roberts, John (ed). (1983). ‘Warships of the world from 1860 to 1905 – Volume 2: United States, Japan and Russia. Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Koblenz. ISBN 3-7637-5403-2.

Schencking, J. Charles (2005). Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, And The Emergence Of The Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868-1922. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4977-9.

Links

https://archive.org/details/cu31924030895795

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suma-class_cruiser

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign