The Upholder class submarines, also “Type 2400” due to their displacement, were the last class of diesel-electric submarines built for the Royal Navy, after the arrival of HMS Dreadnought in 1960. They succeeded to the Oberons, and were designed as a cheap alternative to supplement nuclear submarines in the Royal Navy.

The resurrected the WW2 “U class” by name and concentrate the best tech of the time, in a completely new hull compared to the Oberons, two decades older. They however had a short service life. Completed in 1990-93, they were paid off in 1994 and resold to Canada, in the new context of post-cold war budget restrictions. This came after unsuccessful bid to transfer these to the Pakistan. Modernized, they are still active in the Canadian Navy today as the Victoria class (future post). They initially suffered from serious electrical problems and operational incidents, later overcome until full operational capability.

The Upholder class submarines are a class of diesel-electric patrol submarines originally built for the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Known for their quiet operation and effective armament, these submarines were intended to supplement the Royal Navy’s existing fleet by providing a smaller, more versatile submarine capable of coastal patrol and anti-submarine warfare (ASW). However, the Upholder class had a relatively short service life with the UK, as the Royal Navy transitioned to an all-nuclear submarine fleet, resulting in these submarines being sold to Canada in the late 1990s.

Four Upholder-class submarines were built, designed to operate in the North Atlantic, these submarines were quieter and smaller than nuclear-powered submarines, ideal for operations closer to shorelines. However, they were phased out due to budget constraints and the Royal Navy’s shift to an all-nuclear fleet.

Comparison between the Victoria class and Russian Kilo class

Development

In the late 1970s the British MoD proposed a diesel-electric submarine design as a logical replacement for the Oberon class. They needed to be more cost-effective and now the policy long shifted from an “east of suez” capable force, the new focus was in homle waters. These subs were to procure essentially training in peacetime for SSNs and coastal defence in wartime. The announcement for this new design was done September 1979. Five designs were considered, and the MoD selected an 1,960-ton design. However as the prospect for potential export was there, the displacement was rose to 2,400 tons in order to give more flexibility both for machinery and systems, tailoring for clients. Vickers Shipbuilding & Engineering Ltd. (VSEL) was put in charge.

The plan initially called for twelve submarines to be built but formal approval was given in 1981 for nine only, so not a one-per-on replacement basis. These nine submarines were constructed in three stages:

Stage 1 was the prototype submarine

Stage 2 was the construction of three follow-ons

Stage 3 the construction of five more with updated systems.

R&D benefited greatly from the programme carried out for the nuclear-powered Fleet Submarines. The hull form came from extensive hydrodynamic testings done for these SSNs and made the best of the classic diesel electric powerplant. They also benefited from all their sound-proofing measures (see later). The two high-speed diesel engines coupled to a 1.4 MW generator, plus the double-armature main motor, were a novelty also compared to the Oberons. The generators could be flexibly use to reload batteries or drive the main shaft though the electric engine. Efforrst were made early on to reduce vibrations as well. The powerplant would accept an AIP system in the future, but it’s not the common plan for the RCAN today. But in case of war, this cheaper alternative can be produced en masse and updated with such system.

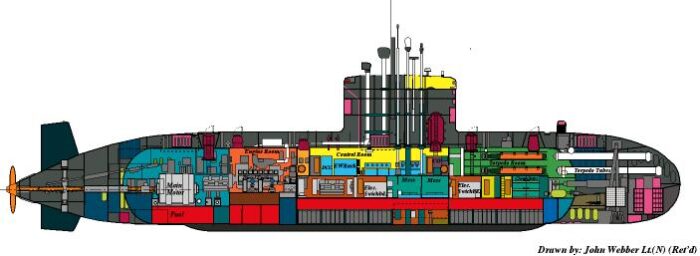

Design of the class

Hull and general design

The class was named at thuis point the Type 2400 diesel-electric patrol submarine. Final displacement was setup between 2,168 and 2,220 tons surfaced, 2,400–2,455 tons submerged for 230 feet 7 inches (70.28 m) long overall and 25 feet (7.6 m) in diameter, for a draught of 17 feet 8 inches (5.38 m). The crew was estimated between 44 and 47. They had a single-skinned hull but a teardrop-shape for the first time (at least for conventional UK boats) and construction used NQ1 high tensile steel for better resistance. This hull was also fitted with elastomeric acoustic tiles to reduce is signature, like recent British SSNs. The reported dive depth was to be over 650 feet (200 m) for extra safety, possible thanks to the new steel used for the hull.

The fin or main sail both houses a five-man lockout chamber but its escape and rescue system was upgraded with additional stowage space for stores for the Victoria class in service and early on, an underwater telephone install to meet Canadian Maritime Force requirements. The crew of 48, all having individual berthing thanks to the three decks, could be augmented by 5 extra personnel acting as commander staff, or a spec ops team in wartime or occasions, and trainees the rest of time.

Powerplant

The Upholder class submarines had a single-shaft diesel-electric system, unlike previous Oberons, powered by a pair of Paxman Valenta 1600 RPS SZ diesel engines. Each in turn drove a 1.4-megawatt (1,900 hp) GEC electric alternator.

In complement are installed two 120-cell Chloride batteries for underwater autonomy. These batteries has a 90-hour endurance (9000-ampere-hour) at 3 knots (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph).

What drove the propeller is a 4.028-megawatt (5,402 hp) GEC dual armature electric motor.

The propeller is seven-bladed, fixed pitch.

Top speed is 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) surfaced, but 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) submerged. To compare, this was 17 knots on the Oberons, so in large part due to the teardrop shape.

Diesel fuel capacity was 200 tons, so making for a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph), 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) when snorting underwater. This was less than the Oberons (10,350 nautical miles surfaced) but quite good for a “coastal” sub. This placed them into the range of the Carribean and back for example and the Mediterranean-Black sea and back. But not the Falklands, unless they had a refuelling underway.

They were limited to 30-60 minutes of snorkling per day for a full reload, and at 8 knot (15 km/h) in transit some 30% of the time. Top speed matched all SSK class of their time, a top speed that could be sustained for some 90 minutes at a noise level way below its Russian equivalent, like the Kilo class (early type) against it’s often compared.

However trials revealed some flaws: Miscalculations were made for the main-motor control circuitry and on HMS Upholder in emergency reversal (“crash back”) there was a flash-over incident and eventally a complete loss of power. The investigation highlighted a fault in the control circuitry design, creating a discharge-to-earth current of 60,000 amp. This was rectified (thats what prototypes are for) and the modifications ported in the next three boats while firring out. The diesels were originally from locomotives, not intended to be rapidly stopped or started. Shutting them down quickly was necessary when coming out after snorting or in emergecy, and this led to many failures. The motor-generators ended also operating at full longer than expected and were quickly worn out. Their brush (not specific to the Upholders) were changed often as a result and this never was fixed.

Acoustic Protection

The Oberons were already lauded for their quietness, as the British invented a concept of rafting which was improved over the years and came to perfection in the 1980s. This consisted in placing all powerplant elements, the generators, diesels, and electric engine as the transmission elements on “rafts” only connected to the hull via rubberized joints and intermediate links, so that the vibrations, if any, were “lost” in the space between these and the hull. This went further in the design of many elements as well and acoustic tests were performed long before the assembly was complete, and further modifications afterwards.

The second step was to drastically reduce the time required to recharge the batteries, thanks to the new propulsion arrangement and snortelling device.

The third step, more recent than rafting, was to cover all external surfaces by 22,000 elastomeric acoustic tiles. Made of a rubber-like compound, their goal was to simply absorb sonar waves, rather than just reflecting those in a more stealthy way. It is said that their acoustic sgnature underwater is the same as the SSN, nearly undetectable on passive sonar, and comparable to SSNs when snorting.

Armament

The class like the previous Oberons had six 21-inch (533 mm) bow torpedo tubes, with a weapons room large enough to accomodate 18 weapons. The primary system was the Marconi Mk 24 Tigerfish Mod 2 torpedoes. There was a complement of four UGM-84 Sub-Harpoon missiles. Minees also could be carried, at a 2 for 1 base.

The core of the system is the DCC Action Information Organisation and Fire Control System (AIS/FC) from DCA/DCB systems, same as UK SSNs. Calculations depended from two Ferranti FM1600E computers with digital data bus, 3 dual-purpose consoles. It is capable of tracking up to 35 targets with automatic guidance for guiding four torpedoes against separate targets simultaneously.

In Canadian service, the Sub-Harpoon and mine capabilities were removed and instead a Lockheed Martin Librascope Submarine fire-control system (SFCS) was installed. In fact, part of the former Oberon-class FCS were installed, so they could fire the US Gould Mk 48 Mod 4 torpedo.

Mark 24 Tigerfish (1970):

Despite many issues, the 1950 program initially setup to deliver an operational model in 1969 was too ambitious and technically complex to meet its original target. This 55-knot (102 km/h; 63 mph), deep-diving torpedo was driven by an internal combustion engine using high pressure oxygen as oxidant. It was guided by a wire system developed from the Mackle project in 1952. It used data transmitted from the firing submarine sonars during its wired run, until detached and completed its race to the target after acquisition using an autonomous active/passive sonar developed from the abandoned 1950s UK PENTANE torpedo project. This was also known as Project ONGAR and engineers were so confident in its superiority it was described as “…the end of the line for torpedo development”. The Mk 24 Tigerfish entered service in 1970, followed in the 1990s by the Spearfish.

⚙ Specifications Mark 24 Tigerfish

Weight: 1,550 kg (3,417 lb)

Dimensions: 6.5 m (21 ft) x 533 mm (21 in)

Power unit: Electrical, chloride silver-zinc oxide batteries 35-knot

Maximum range: 39 km (43,000 yd) at low speed, 13 km (14,000 yd) at 35 kts

Warhead: 134 to 340 kg (295 to 750 lb) Torpex

Guidance: Wire-guided to point, passive sonar target acquisition/terminal homing.

Next torpedo to cover: The Spearfish (Swiftsure class).

RGM-84B Sub-Harpoon:

The cancellation of the Undersea Guided Weapon programme led to purchase instead the Sub-Harpoon to give SSNs a long range capability strike. Normal provision was six of them, replacing torpedoes. Trials started in October 1981. This purchase was followed by the selection of the latest surface version, the RGM-84C, as the successor to the Exocet.

In short: Size 4.63 m x 0.343 m, 683 kg, Teledyne J402-CA-400 turbojet + booster, Mach 0.9, range 130 km.

Payload 221 kg WDU-18/B penetrating HE-fragmentation with delayed impact fuse.

Guidance: Initial phase Inertial navigation, final Active radar homing, sea skimming.

Stonefish and Sea Urchin mines:

Two could fit and take the place in the tube of a torpedo, they had the same diameter.

Stonefish mine: Developed by BAE for the RAN initially it had a warshot with incremental payload, generally with an aluminised PBX warhead base. It existed in four variants. Src

Sea Urchin mine: It was also developed by BAE (British Aerospace) in the early 1980s with a variety of warhead (250 kg, 500kg, and 750 kg) and common sensing, fuzing, and arming system combining acoustic, magnetic, and pressure sensors. It seemed to have been tested but never purchased.

Gould Mk 48 Mod 4 torpedo (1988):

ADCAP, Mark 48 Advanced Capability (ADCAP) variant, heavyweight submarine-launched torpedo designed to sink deep-diving nuclear-powered submarines, high-performance surface ships.

Top speed: 40 knots (74 km/h) for the initial batch. Range: 50 kilometres (31 mi).

Torpedo range ADCAP: 38 kilometres (24 mi) at up to 55 knots (102 km/h). Active and passive homing.

Gould Mk 48 Mod 7AT (mode 7 CBASS):

In 2014, the Government of Canada purchased 12 upgrade kits that will allow the submarines to fire the Mk 48 Mod 7AT torpedo. Presumably the MK 48 Mod 7 CBASS or Common Broadband Advanced Sonar System (CBASS) Heavyweight Torpedo. Initially developed for AUKUS and proposed to Canada. Development was completed in November 2004, operational testing in November 2005. Initial operational capability in 2006 after upgrades. Fired by HMAS Waller at RIMPAC 08 in July.

Specs:

Dimensions: 5.8m x 53cm, weight 1,676kg.

Warhead: 292.5kg.

Propulsion: Otto Fuel II Piston engine, 28kt+ (classified), range of 5 miles+ (same)

Can reach maximum depth of 1,200ft.

Active and passive homing guidance: Common Broadband Advanced Sonar System): Can detect and engage low-Doppler shallow submarines, fast deep diving submarines, high-performance surface ships.

Fire-and-forget operation, wire-guide capability option.

Sensors

Command and Control

For the first time into a conventional submarines in UK, a local area network was built to support most of the sensors and fire-control systems. This included also remote viewing through the periscopes by low-light television, infrared, unmanned helm or direct control of the powerplant elements from the CC under the sail. The combat team comprised just four in the sonar room, eight in the adjacent CC. Fire-suppression systems in unmanned compartments were remotely launched, watch-keeping logs automatically recorded. In port, they could be electronically linked together so that a single duty watchstander could monitor all fur at once if needed.

Navigation: Kelvin Hughes Type 1007 I-band radar

Sonar suite:

Type 2040 Thompson Sintra ARGONAUTE (bow). Upgrade to Type 2075 cancelled in 1991.

Type 2026 GEC Avionics passive towed array.

Type 2019 Thompson Sintra PARIS passive sonar.

Type 2041 passive ranging sonar

Type 2004 expendable bathythermograph.

Coms: Type 2008 underwater telephone.

1994 Refit:

BAE Type 2007 array, Type 2046 towed array added.

Canadian Towed Array Sonar (CANTASS) integrated in refit.

-CK035 electro-optical search periscope

-CH085 optronic attack periscope (Pilkington Optronics)

Post refit: Canadian communication equipment and electronic support measures, with two SSE decoy launchers and AR 900 ESM.

CK 35 search periscope, Barr &Stroud CH 85 attack optronic periscope from Thales Optronics were kept. The CK35 incorporates a binocular optical system with optical target ranging system.

The CH85 incorporates a monocular optical system with infrared system for surveillance and attacks on surface targets. Both periscopes uses range-estimating devices.

The Thales Underwater Systems Type 2007 is a very capable flank array sonar and the Type 2046 towed array sonar operating in passive mode, low frequency, for long range detection and location. The Canadian Towed Array Sonar (CANTASS). The latter is an AN/SQR-19 hydrophone array with a powerful AN/UYS-501 “dry end” signal processor from Litton Systems Canada Ltd. Two or more CANTASS spaced a distance apart can triangulate bearings to pinpoint the source of the submarine noise.

It is Common to the Annapolis-class, Halifax-class, Oberon and Victoria-class.

On 06 March 2018, HMCS Windsor received the Lockheed Martin AN/BQQ-10 (V)7 sonar processing suite, with an upgrade of the passive ranging sonar fit, bow sonar system upgrade, and high-frequency active sonar.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 2,455 t (2,416 long tons) |

| Dimensions | 70.26 x 7.2 x 7.6m (230 ft 6 in x 23 ft 7 in x 24 ft 11 in) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft 2× Paxman Valenta 2,035 hp (1.517 MW) diesels, 1 GEC electric motor 5 MW |

| Speed | 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) surfaced, 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) submerged |

| Range | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 8 kn, 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) snorkelling |

| Armament | 6 x 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes (18 Mark 48 torpedoes) |

| Test depth | 656.17 ft (200 m) |

| Sensors | CN/BQQ-10, Type 2040, 2041 micropuffs, 2007 flank, 2046/CANTASS MOD, 2019 active |

| Crew | 53 |

Career of the Upholder class

While HMS Upholder was completed on 9 June 1990, Unseen was on 20 July 1991, Ursula on 8 May 1992 and Unicorn on 25 June 1993. So they were part of the park designed back in the cold war (some would say at the peak of it) and completed afterwards in a context of massive budget restrictions.

Indeed in 1992, the Defence Review announced the MoD to direct all expenditure to nuclear-powered submarines only. In 1994, the Royal Navy officially abandoned the Type 2400 program after phase 2. The five improved boats of Stage 3 were never ordered. More so, just a few years into service, the Upholder class were declared surplus in 1994, and HMS Unseen was paid off on 6 April 1994, Upholder on 29 April, Ursula on 16 June, Unicorn on 16 October. This was the shortest career of any British submarine ever.

Sea trials and sensors trials went on however, not weapons trials as initially they had a critical torpedo tube issue, and its automation process needed to be fixed first. Refits were performed in 1992 and 1993 at a cost of £9 million. For the short time they operating in 1993-94, they were based from HMS Dolphin (Gosport). The dedicated base was deemed uneconomic so they were transferred to Devonport Naval Base. They operated in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean and UK waters however, making the best of their short active time.

HMS Upholder (1986)

HMS Upholder (1986)

The MoD placed an order with VSEL for Stage on 2 November 1983 and HMS Upholder was laid down at Barrow-in-Furness NyD the same month, launched on 2 December 1986. She was the protoype. Order for Stage 2 was placed on 2 January 1986 and a contract for the next three awarded to Cammell Laird, a subsidiary of VSEL. The cost was £620 million without long-terms expenditures.

HMS Unseen

HMS Unseen

HMS Unseen was laid down at Cammell Laird, Birkenhead on 12 August 1987, launched on 14 November 1989, completed on 20 July 1991 and in refit by 1992 after sea and sensors trials. She was deployed agai by late 1992 and all 1993 in the Mediterranean, but was laid first up 6 April 1994.

Ursula

Ursula

Ursula was laid down on 25 August 1987 and launched on 22 February 1991, she was refitted in 1993, based from Gosport she made a single long term deployment across home waters and the Mediterranean. She was laid up on 16 June 1994.

Unicorn

Unicorn

Unicorn was laid down on 13 March 1989 and launched on 16 April 1992. HMS Unicorn after refit completed a 6-month deployment east of Suez, however, Mediterranean, Gulf of Oman, Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf. She was laid up on 16 October 1994, seeing service for most of this year as she was in refit for more of 1992.

In 1992, two years before they were laid up, the British Gvt. learned about the desire of Pakistan to acquire submarines from France under the Sharif administration. The types were either diesel-electric or AIP (air-independent) and its research team visited Sweden, China, France, and the UK. Initially it leaned towards Sweden but later British Upholders or French Agosta class were recommended. Admiral Saeed Khan, Chief of Naval Staff strongly suggested the Upholder class. However the Bhutto administration chose instead French Agostas. In 1994 the Upholders were left without future, apart a long time in reserve and scrapping, but there was hope given the success of previous subs at export.

Canadian Navy Service (1998–Present): The Victoria class

Negciations indeed started already in 1993 by Canada. Following the cancellation of the Canadian nuclear-powered submarine program after budget cuts resulting from the end of the cold war, the Gvt. fell back to conventionally-powered submarines as stated in the Defence White Paper of 1994. Stressing the replacement of earlier Oberons, the purchase of Upholder class felt logical, but faced opposition notabl for the cost of $1 billion demanded. Cabinet of Canada was not greenlight yet. Meanwhile, attempts were made to sell these were to Portugal and Chile, which also looked to replace their own park. In 1996, Canada reslaunched the acquisition but it stopped again. The RN meanwhile had to keep maintaining the submarines.

In April 1998, the Canadian government, after another negociation round, announced the acquisition with a published cost at $750 million, divided into the subs themselves and related expenses.

On 3 July 1998 it was ratified, two contracts signed with a 8-year interest-free lease-to-purchase agreement as well as 5 training simulators and assorted training/data packages. This included the leas to Canadian Forces of the British bases Wainwright, Suffield, and Goose Bay. VSEL also had to provide refits to reactivate the class and made some Canadian adaptations as well as new batteries and spare parts. Still opposition in Canada denounced the deal, asking UK cover further costs, as many thought the Upholders deteriorated while in storage. Reclassified as the Victoria class, and after extensive refitting and upgrades, they were eventually renamed as HMCS Victoria, Windsor, Corner Brook, Chicoutimi. Although they faced initial technical issues and refit delays, they are now the deterrent core of the Royal Canadian Navy, remaining operational today albeit with discussions about a replacement, notably by French shortfin Barracudas as of 2025.

In 2008, Babcock Canada was awarded the support the Victoria class up to 2023 under CAD $3.6 billion, plus mounting a supply chain in Canada and a program of refit updates every 6-9 years in Extended Docking Work Period (EDWP) (maintenance, repair, overhaul, upgrading of 200 systems). Eight Submarine Command Team Trainers were moved from the UK to Canada and setup by CAE, Computing Devices Canada, General Dynamics Canada and Irving Shipbuilding. This inludes simulators and other training systems and the Canadian Submarine Escape Trainer, attached to a real submarine escape hatch. The initial goal was to maintain the submarine operational by 2000, including 18-month systems check, 6-month Canadian Work Period (CWP) with new Canadian communications and fire control systems installed. Canada announced plans for a major life extensio on 7 April 2015, FY2020 at an estimated cost of $1.5 and $2 billion CAN.

HMCS Victoria

HMCS Victoria

On 6 October, HMS Unseen was accepted by Canada at Barrow-in-Furness, renamed Victoria, proceeding to Canada and arrived on 23 October 2000, commissioned into Maritime Command on 2 December. She then underwent her CWP and on 29 June 2003, was transferred to the west coast, at Esquimalt on 24 August. She had several sea trials and training plus her major refit EDWP on 27 June 2005, emerging from it at the end of 2011. She was declared fully operational in March 2012 to take part in RIMPAC, sinking ex-USNS Concord with torpedoes and participated in Operation Caribbe in 2013. More logs to come.

HMCS Windsor

HMCS Windsor

HMS Unicorn was accepted by Canada, renamed Windsor on 5 July 2001, left Faslane on 8 October, to Halifax on 19 October. While in sea trials suffered minor flooding while submerged and started her CWP, commissioned into Maritime Command on 4 October 2003. She became the first active in class by June 2005. She then took parft in several international naval exercises and on 15 January 2007 she started her EDWP refit at Halifax, until 30 November 2012. She was in drydock by March 2014 to replace a defective diesel. In 2015 she performed a 105-day training cruise, longest deployment of a Victoria-class, including training exercises with NATO in the North Atlantic, tracking undetecting 5 submarines from other nations. More logs to come.

HMCS Corner Brook

HMCS Corner Brook

HMS Ursula was accepted, renamed HMCS Corner Brook on 21 February 2003, departing Faslane on 25 February, arrived on 10 March, commissioned at her namesake city on 29 June, followed by her CWP from 2004 to 2005, sea trials on 24 October 2006. By August 2007, she took part in Operation Nanook in the Arctic and NATO naval exercise “Joint Warrior” in European waters. By March 2008, she took part in Operation Caribbe in the Caribbean Sea. In August 2009 she was at Operation Nanook. On 30 January 2011 she departed Halifax to transfer to the west coast for Operation Caribbe via Esquimalt on 5 May 2011. On 4 June while diving off British Columbia she hit the seabed at 45 metres (148 ft) at 5.9 knots. Two sailors were injured and damage included 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) hole in the bow, two torpedo tube doors torn off. She surfaced and returned to port, the commander later court martialled and stipped from command. She was in repairs until 2018. More logs to come.

HMCS Chicoutimi

HMCS Chicoutimi

The crew of Onondaga, last Canadian Oberon, transferred to Upholder by July 2000 and started training in UK until the sub was accepted by Canada on 2 October 2004 at Faslane, as HMCS Chicoutimi, leaving on 4 October 2004. While underway the following day, surfaced, she passed through a gale, with 6-metre (20 ft) seas and during a watch change at 03:00, as partially flooded, but water was stopped by the lower hatch. However the drain failed to operate. It was necessary to protecte systems in the CC, open the hatch and water was pumped overboard, the incident being noted. Drain valves were repaired before diving. At some point the lower hatch was reopened as a large wave passed over the sail, swallowing 2,300 L of sea water, followed by electrical explosions and fire, spreading quickly. All systems aboard were shut down, leaving her dead in the water. Attempting to restore auxiliary power caused another fire and at 19:12, attempts to remove smoke by using an oxygen generator caused another fire in which 9 sailors were injured, three seriously. She was assisted first by Irish patrol vessel LÉ Róisín, but she was forced to return to port due to the weather being worsened. Then the frigate HMS Montrose arrived the following day, three were evacuated by her helicopter, flown directly to Sligo in Ireland for internsive care. One died of his injuries anyway. Chicoutimi was towed on 7 October back at Faslane on 9 October. After repairs, she was transported to Halifax aboard the heavy-lift vessel Eide Transporter and made it on 1 February 2005. After assessment she was sent to Esquimalt on the Tern, and started a major refit on 29 April 2009. She was only commissioned by 3 September 2015, at Esquimalt but restricted to shallow-water. By October she took part in joint exercises with the USN.

Chicoutimi and Victoria were deactivated in 2016 after hundreds of welds were found defective. Docked at Esquimalt for months, Chicoutimi was repaired first, then Victoria. Victoria was used for training purposes until repairs were done and by September 2017, Chicoutimi patrol in Asian waters, first ever Canadian sub to visit Japan by a Canadian submarine since 1968, back on 21 March 2018 after a record 197 days at sea.

Life extension and replacement

Under the Trudeau administration and defence policy paper, was decided a DELEX in 2017 adding an additional eight years service, up to 2025. But by 2020 no decision for replacement was taken, whereas the subs were approaching 30 years. Analysis by the Naval Association of Canada indicated high technical challenges and costs, which delayed the decision. John Ivison assessed six submarines types as potential replacement, the French conventional Shortfin Barracuda, German Type 212CD, Japanese Taigei, Korean KSS-III, Spanish Isaac Peral, Swedish Blekinge class. On 10 July 2024, the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project (CPSP) was announced and expanded to 12 submarines while an RFI was issued by Public Services and Procurement Canada in September 2024 and on 21 November, excluded the Taigei class. Total cost estimated $100 billion, and entry into service FY2037 as of 2025.

Read More/Src

Books

Cocker, Maurice (2008). Royal Navy Submarines: 1901 to the Present Day. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Books.

Gardiner, Robert; Chumbley, Stephen; Budzbon, Przemysław, eds. (1995). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1947–1995.

Macpherson, Ken; Barrie, Ron (2002). The Ships of Canada’s Naval Forces 1910–2002 (Third ed.). Vanwell Publishing

Milner, Marc (2010). Canada’s Navy: The First Century (Second ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.3.

Perkins, J. David (2000). The Canadian Submarine Service in Review. Vanwell Publishing Limited.

Saunders, Stephen, ed. (2004). Jane’s Fighting Ships 2004–2005. Jane’s Information Group.

Darman, Peter, ed. (2004). 21 Cent. Submarines and Warships. Military Handbooks. Rochester: Grange Books.

Miller, David; Jordan, John (1987). Modern Submarine Warfare. New York: Military Press.

Miller, David (1989). Modern Submarines. Combat Arms. New York: Prentice Hall Press.

Links

On rnsubs.co.uk

jproc.ca/rrp/victoria.html

seaforces.org/

en.wikipedia.org/ Upholder Victoria-class_submarine

naval-technology.com mk-48-mod-7 Torpedo

web.archive.org/ navypedia.org/

navy.forces.gc.ca victoria/

hazegray.org/ canada/ upholder/

paxmanhistory.org.uk paxsubs.htm

commons.wikimedia.org/ Upholder/Victoria_class_submarines

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign