The Royal navy Turret Fighter

The use of turret fighters was proper to Britain. No other nation trusted this concept rather than the more classical approach of a gun-armed (fixed) wing and fuselage armament, aimed by the pilot for a fighter. It’s the trust in Boulton-Paul’s turret design that really made the aair ministry believing this was an efficient alternative for a fighter in 1935.

The story of the Roc started with the 31 December 1935 Specification O.30/35. It sought a carrier-based turret-armed fighter for the Fleet Air Arm (FAA), which had no say in the matter. Manufacturers were contacted and both Blakburn and Boulton Paul passed the initial commission proposal stage.

Blackburn’s design team headed by G. E. Petty proposed a derivative of the new Skua (two prototypes already ordered earlier) but with a widened fuselage mid-section to accommodate the turret. This saved a considerable design time and afforded all the advantages of the already accepted Skua (see later).

Rival Boulton Paul proposed the P.85, essentially a carrier-capable version of the land-based P.82 turret fighter created for Specification F.9/35, and later mass-produced prewar as the “Defiant”. The main difference was that instead of an inline engine, it was fitted with a Bristol Hercules radial engine alternative to a Rolls-Royce Merlin. Called the “Sea Defiant” it was expected to be 85 mph (137 km/h) faster than rival Roc, but the Air Ministry decided to select Blackburn’s model anyway, probably based on its trust into the company for products tailored for sea use. Boulton-Paul rarely designed models for the Navy until then.

The B-25 Roc was a modified copy of the Skua and even retained its wing-mounted dive brakes, but its mainplane was redesigned, with a slight dihedral to obviate the upturned wingtips.

On 28 April 1937, the Air Ministry placed an order for 136 Rocs, before any prototype flew. Indeed Blackburn was fully involved in biolding the Skua and Botha torpedo bomber so the air ministry decided simply to assign production to the rival Boulton Paul, at Wolverhampton, which some author’s saw as a “sanction” for the delays in delivery of the Defiant. No doubt the loosing time was not happy with it as it provoked even more complication to have the Defiant delivered on time.

Design specifics

General conception

The general construction of the Roc was a retake of the Skua, standard but innovative by 1935. The fuslage’s construction in fact long derived from the Blackburn Shark notably with typical Blakburn’s flush-rivetted Alclad. It was indeed a low-wing cantilever monoplane of all-metal construction. The framed structure was wrapped in duralumin, whereas wood and canvas was still used by many British manufacturers of the time. Wings had a slight dihedral, with straight edges, rounded tips, elliptic tail as the ailerons. The glass cockpit was the most distinctive feature, short, offering good visibility but with a front section (forward windshield) with very low slope, looking little arodynamic.

Internally this fuselage, like for the Skua, was divided into two water-tight compartments under the crew for extra floatability and buoyancy. The crew compartments was fully watertight on both sides of the cockpit also. The general construction was sturdy enough for catapult launched but also rough carrier arrested landings. There were even a hydraulic dampening device in the hook’s arm. The whole structure and wings cover were made of Alclad, cut into three separate units.

The twin-spar, heavy centre section was bolted beneath the fuselage and also acted as watertight compartment’s bottom.

-The outer wing panels had detachable upswept tips. They were completely sealed between the main spars and recesses in the lower wing surface accommodated modified Zap flaps.

-The balanced ailerons had inset hinges, mass balance assistance.

-The retractable undercarriage system and folding wings were also specific to the company, manufactured as Blackburn Airedale facility.

-The elevators were situated 60% aft of the end of the tail, in both the Skua and Roc.

-The wings folded around an inclined hinge housed within the wing. It enabled a twist, to nicely fit and rest against the fuselage, then all secured by latch pins. Into the wings, were located the waterproof bulkhead for extra buoyancy and various extra watertight bulkheads. Combined to the low weight of the engine and whole structure, this enabled to contain enough air inside to keep the plane afloat indefinitely, ensuring the survival of the stranded crew.

-The main undercarriage folding process was engine-driven using an hydraulic pump.

-The tail wheel unit had a Dowty self-centering shock absorber strut for damping it out.

-The arrester hook ended before the main tail whiched ended with the prominent ventral fin aft fairing where the tailwheel rectracted.

-Tailplane and fin were metal-clad. They were bolted directly onto the fuselage’s rear frames.

-The Roc had controllable trim tabs and a horn-balanced rudder for emergency spin recovery.

-Just the rear portion of the tailplane was fabric-covered and there was an elevator positioned behind its trailing edge.

-The wheeltrain was composed by dunlop tires fixed to a single oleo leg, which was damped by a folding rear arm. It’s inner face was covered by the oleo-leg fairing and its lower part was foldable when landing, fully retracted into the wings in flight between the mainwheel wells after an automatic 90° turn.

-It seems the Zap-type air brakes/flaps were not omitted from the design (they were used by the Skua for dive bombing), as they were found useful to break speed when landing.

Cockpit

The main cockpit comprised seatings for the pilot, while the rear gunner was lodged into the trademark turret of the model. This canopy was the most distinctive part of the design: It had the low-angle windshield for good visibility, but much drag. The pilot’s canopy slided to the rear for exit, but there was still the inherent danger or hurting the tail section. He had an enveloping chair, with harness and adjustment lever. His head was protected by an unarmoured crash turnover pylon. Her had a reflector sight, much simpler since he had not forward-firing armament and no need for a dive bomb run.

The gunner’s own canopy however was completely different than the Skua, just as the center section. Behind the pilot’s sea the canopy indeed was sloped back to to ensure the best forward arc for the turret behind. There was an extra section built above it that can be removed as shown in photos. The whole concept behind the Roc was driven by this (paper) faith into the revolving quad turret. On paper, the armament was more powerful than the Skua and could face any foe, at any angle. It was considered better than a classic rear flexible mounted MG configuration of most navy models. More on this later.

The turret was followed by a folding down section of the fuselage, which was the other peculiarity of the Roc’s design. Indeed, this section was raised to enable better aerodynamic qualities of the air flow towards the tail, but it hampered the turret’s revolving motion and thus, was folded down into the fuselage in “alert mode”. This feature, unique to the Roc, obliged to revise the aft fuselage configuration entirely. Inside the lower fuselage section was also placed the collapsible dinghy, along with rations and a survival kit.

Behind or in and around the cokpit were located the first aid store box, while the bulkhead frame was kept, as well as the two upper fuel tanks (twice 282 Liters of imperial gallon), the oxygen reserve for high altitude fying. The forward fuselage section had extra space behind the engine, short and compact. The air radiator cooler and ducting were located in this section, as well as the alcohol tank for winter de-icing, compressor air reservoir, and starter housing. The cowling itself comprised 13 adjustable cooling grilles.

The secondary reservoir was located in front of the pilot with 39 imperial gallons (177 liters) capacity.

The oil tank was located above, with an external filler cap, 10 imperial gallons capacity (45.5 liters).

Engine

The Roc depended on the Bristol Perseus XII nine-cylinder air-cooled sleeve-valve radial piston engine, more powerful than the one of the earlier Skua. It developed 890 hp (660 kW). No better engine was fitted as the production run was short. The Bristol Perseus was first invented in 1932, as the first production sleeve valve aero engine. It met considerable success, bith domestic and abroad, being fitted with many models, including for the Navy, the Skua and Roc, the Gloster Goring floatplane and Short Empire flying boat. Sufficient in 1936, by 1940 it was obsolete and superseded by much more powerful engines.

Performances of the Roc were not stellar, even less than the Skua due to the bad aerodynamic profile of the dorsal section, between the canopy, and both forward and aft sectins around the bulky turret, causing excessive drag. Air flow when the aft part was retracted caused even more air flow disturbances.

The engine drive a 3-bladed variable-pitch propeller. With a gross weight of 3.6 tons, performances were as follows:

-Maximum speed: 194 kn (223 mph, 359 km/h) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

-Cruise speed: 117 kn (135 mph, 217 km/h)

-Range: 700 nmi (810 mi, 1,300 km) with 70 imp gal (320 L; 84 US gal) long-range tank

-Service ceiling: 18,000 ft (5,500 m)

-Rate of climb: 1,500 ft/min (7.6 m/s)

The performances were one reason of the whole concept failure. At 350 kph at best, 300 in normal conditions or far less when cruising, the speed gap with the Messerschmitt Me 109 was enormous. The latter could approach so fast the gunner had not time to correctly aim and fire, and the German fighter’s main gun could do short work of the gunner. When done, the Roc was not more than a target practice, having no armament backup and poor performances. The Me 109 could circle around and chose its moment to pounce.

Armament

The centerpiece and main concept around the Roc was it’s turret. The configuration was imposed by the air ministry, but saw with doubt by the Navy (rightfully). By 1940 the FAA counted on the brand new Fairey Fulmar for its air defence, fault of a better model like the Hurricane or Spitfire, but not the Roc.

It was composed of an upper glassed section under a spider type metal canopy frame, internal attachements for the four .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns. The turret could rotate in any direction, without stops at some angles to avoid hitting the tail for example. There was however integrated automatic interruption to prevent this, or hitting the propeller. The gun mount elevated to 85 degrees to even shoot down overhead planes, and the motion was achieved via a control column.

The turret was hydraulically using an electrically-driven pump. The Browning guns were fired electrically with a remote single trigger for the pilot.

Test on the ground showed the turret’s fast traverse and elevation were more than a match for any model at the time.

It is also fogotten, but the Roc, like the Skua, had provisions to act as bomber if needed: Two 250 lb (110 kg) bombs and eight practice bombs could indeed be carried upon bomb racks under each wing as shown in photos. The wings could accept also a provision for a droppable close-fitting 70-gallon external fuel tank on the underside of the central fuselage.

Production

A large proportion of the work was subcontracted to Boulton Paul, which at the time, hope to sell a naval version of their own turret fighter, the Boulton Paul Defiant. The latter funded great hopes by the RAF before the war, but was not alone as a concept. Indeed the forerunner has been the Turret Demon, a late variant of the Hawker Demon, heavy two-seat fighter derived from the Fury, of which 59 were built in 1935 (plus 10 in 1937) and here again, Boulton Paul was of course responsible for the turret.

Boulton-Paul was founded in 1918 and started production other models like the Sopwith Camel, before swapping on enclosed defensive machine gun turrets for bombers. Whole bombers were also proposed like the Sidestrand or the very innovative Overstrand, metal cladded and fully enclosed with turrets, but for this, it licensed a French design of an electro-hydraulic four-gun turret which became the bedrock of its future production. The installation on fighters was never anticipated but the Roc’s primary armament was exactly the same Type A power-operated gun turret as on the Defiant.

It is easy to imagine the company, forced to manufacture the winning design over it’s own product, and somewhat dragging its feets.

Nevertheless, on 23 December 1938 (the initial specification dated back 1935) the prototype performed its maiden flight at Blackburn’s test track, at the hands of company test pilot H. J. Wilson. Contractor’s trials were performed at Brough in March 1939 and it was delivered to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) located at RAF Martlesham Heath, notably for final armaments trials.

Early modifications included the new new De Havilland propellers and testing revealed a surprisingly better handling than the Skua; although certainly not on aerobatic level. It showed the same sturdiness and precision in steep dives but also poor performance in top speed 223 mph. This could only be corrected after the adoption of a new engine and considerable fuselage design revisions, and thus, as the model was already delayed, some pushed for its production nonetheless.

Some officials were worried (rightfully so, notably in the FAA) about its inadequate performances for a fighter, but by October 1938 Fifth Sea Lord Alexander Ramsay recommended that further development be abandoned. Production nevertheless had been already greenlighted to Bouton Paul and was authorized to go on, not to cause too much disruption for Boulton Paul… It was soon plan to adapt the aircraft as a target towing model or for other secondary duties. At that stage in early 1939, the Roc (as the Defiant for some in the RAF) was seen already as a failure. At least the saving grace of the Defiant was its better performnces, due to better aerondynamics in general and inline engine. This was not enough though. The whole concept collapsed during the battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. The poor performances also convinced the FAA to sideline the ROC as well.

Production at Boulton Paul of the Roc ceased by August 1940. The Air Minustry instead granted the FAA demand for more Fairey Fulmars and access to the Hawker Sea Hurricane.

The floatplane prototype.

Still, the Air Ministry attributed the Rocs ordered as carrier-based fighter. But also examined its reconversion as a floatplane, for an always useful fighter floatplane (which did not existed in British inventory at the time). A conversion kit was designed with two floats from a Blackburn Shark, largely composed of Alclad and fitted with pneumatically-actuated water rudders, connected directly with the aircraft’s conventional braking system. This enabling an unprecedented level of cushion when landing, and a mcuch softened, dampened ride when taking off. The tail wheel was replaced by a mooring ring.

Testing in later 1939 showed instability and by December the prototype crashed at Helensburgh Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment. Testing went on with the other conversion, with great effort to correct its stability with an enlarged ventral fin but the float’s drag was still too much, reducing top speed to a miserable 193 mph (168 kn; 311 km/h). This hattered any hopes to constitute a floatplane fighter squadron.

In 1942, the Roc floatplane was evaluated to be used as a target tug for the fleet, replacing the obsolete Blackburn Shark floatplanes using as such. But this was rejected as the FAA wanted its target tugs being landplanes, notably the Miles Martinet.

Specifications B24 Skua Mk.II |

|

| Crew: | 2: Pilot, Rear Gunner/Observer |

| Dimensions: | 35 ft 7 in x 46 ft 2 in x 12 ft 6 in (10.85 m x 14.07 m x 3.81 m) |

| Wing area: | 319 sq ft (29.6 m2) |

| Airfoil: | Root NACA 2416, tip NACA 2409 |

| Weight: Light/Gross | 5,496 lb (2,493 kg)/8,228 lb (3,732 kg) |

| Propulsion: | Bristol Perseus XII 9-cyl AC radial sleeve-valve piston engine, 890 hp (660 kW) |

| Propeller: | 3-bladed variable-pitch propeller |

| Performances: | Top speed: 225 mph (362 km/h, 196 kn) at 6,500 ft (1,981 m) |

| Performances: | Cruise speed: 187 mph (301 km/h, 162 kn) [32] |

| Service ceiling: | 20,200 ft (6,200 m) |

| Rate of climb: | 1,580 ft/min (8.0 m/s) |

| Range: | 760 mi (1,220 km, 660 nmi) |

| Armament – MGs | 4× 0.303 in (7.7 mm) FWD Browning (600 rds), 1x Lewis/Vickers K MG aft |

| Armament – Bombs | 1x 500 lb (230 kg) SAP or 8×30 ib (14 kgs) under wings |

Royal Navy service

By April 1939, the FAA prepared for the arrival of the first batches of Rocs as the 5th production model was delivered to the Central Flying School. Deliveries started to fill the Skua-equipped 800 and 803 Naval Air Squadrons, as a complement and escort of 3-4 each. 803 Squadron was lated sent to RAF Wick (northern Scotland) top defend Scapa Flow against Luftwaffe’s incursion, but there, the Rocs proved ineffective during various alert flights, unable to catch up with the fast Dorniers and Heinkels. The squadron’s commanding officer even reported them being a “constant hindrance” and asked for additional Skuas instead.

The Roc was also sent in the Allied campaign in Norway, the organic fighters of the 800 and 801 Naval Air Squadrons, brought by HMS Ark Royal. 803 Squadron got rid of these Rocs and swapped on all-Skuass in between. The Rocs performed combat air patrols over the fleet but when incoming Luftwaffe aircraft were signalled, they just failed to keep up and failed to perform any interception.

Both Skuas and Rocs also were used in the English Channel by the summer of 1940, and covered allied troops evacuation of Operation Dynamo and Operation Aerial. Miraculously, the one and only aerial victory ever reported for the Roc occurred on 28 May 1940. A Roc from 806 Naval Air Squadron (pilot Midshipman A. G. Day) escorting two Skuas, intercepted five Junkers Ju 88s attacking a convoy off Ostend in Belgium. The Roc flew underneath these Junkers (which were on paper much faster, but evolved at cruis speed) and as the Skuas attacked from above, Roc managed to fire its Browning into one Ju 88’s belly. It was reported missing later and confirmed as a kill.

On 12 June, Rocs and Skuas (801 Naval Air Squadron) attacked German E-boats in Boulogne harbour, causing damage to several E-boats.

On 20 June, Skuas and Rocs again attacked gun emplacements at Cap Gris Nez. It’s likely the attached Roc used their Brownings for side strafing fire in “gunship” mode.

The Roc however was hopeless in its initial role and relegated to air sea rescue and target-towing, sent in various locations. The last coming from the production line went directly to second-line squadrons, and no carrier had any aboard. It was replaced since months by the Skua.

16 Rocs were for example sent to No. 2 Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit at Gosport, repacing its Sharks by June 1940.

On 26 September 1940, Pilot Officer D. H. Clarke and gunner Sergeant Hunt while in SAR mission spotted and engaged a slow Heinkel He 59 seaplane while the latter was attempting to “rescue” a British pilot (for interrogation and custody), and the Heinkel fired first on the approaching Roc. The duel between the two went on until they reached the coast and the Roc broke off due to the FLAK. The Heinkel survived, but badly damaged.

Some Rocs were sent to distant and “cushy” locations such as Bermuda. The very last Rocs were withdrawn by June 1943 and four were still stationed at HMS Daedalus, Gosport by late 1944 not in flying conditions but to use their turrets for local AA defence.

General assessment

Doomed by a both delayed design and production (1935 to 1939-40), a too slow platform to make a good fighter, and a bad concept (the turret fighter), the Roc was certaonly one of the worst fighter ever and certainly the worst naval fighter of the FAA. It was adopted over the head of the FAA itself which wanted to cancel the program, and reluctantly accepted as an organic “escort fighter” for the Skua, but proved inept when carrier-deployed, notably in Norway. Sidelined, cast off from any carrier use, the Roc while still in production was sidelined to secondary roles where it proved some usefulness in 1941-42 to gradually fade up in obscurity. Meanwhile the Fulmar, Sea Gliadiator and Sea Hurricane all proved lightyears better.

The Roc was however a relatively good plane that can have been useful if reconverted as a Skua dive bomber, which could be done relatively quickly. But in 1940 it was a waste of time and money as the base Skua was already obsolete.

It’s worth to note that the FAA had a far worse model in service (or nearly so), the appealing lend-leased Brewster Bermuda, infamously scrapped out of the crates.

Sources/read more

Links

on britishaircraft.co.uk/

on dingeraviation.net/

on classicwarbirds.co.uk

on militaryfactory.com

on artsandculture.google.com/

militarymatters.online/

destinationsjourney.com

aviastar.org/

2aircraft.net/

Gallery

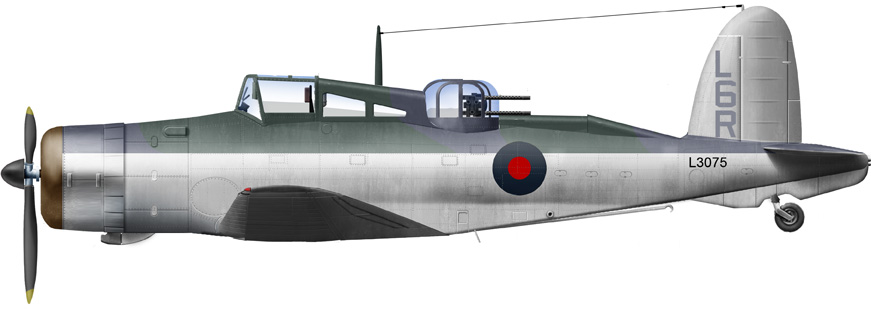

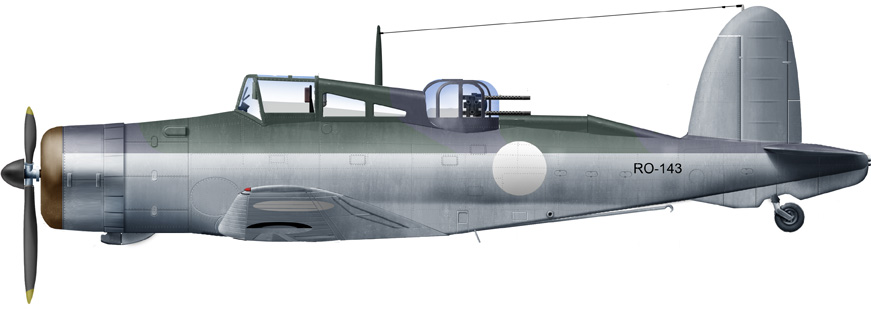

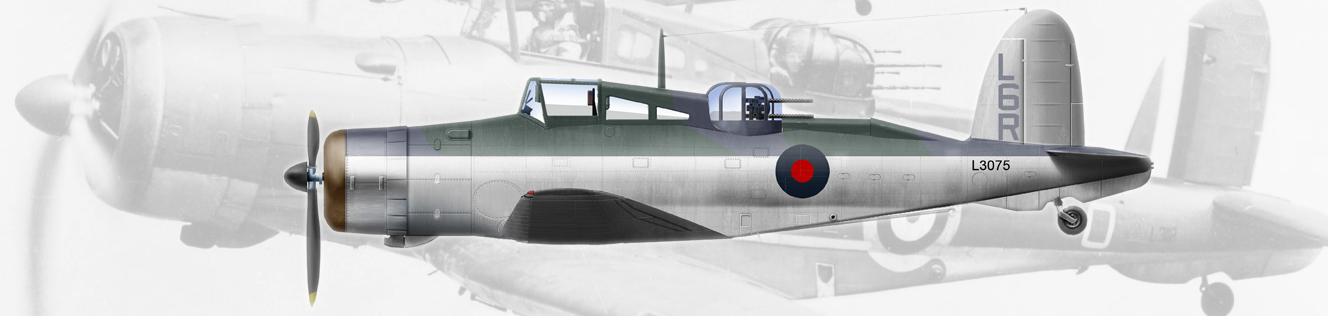

Author’s illustrations: Types and liveries

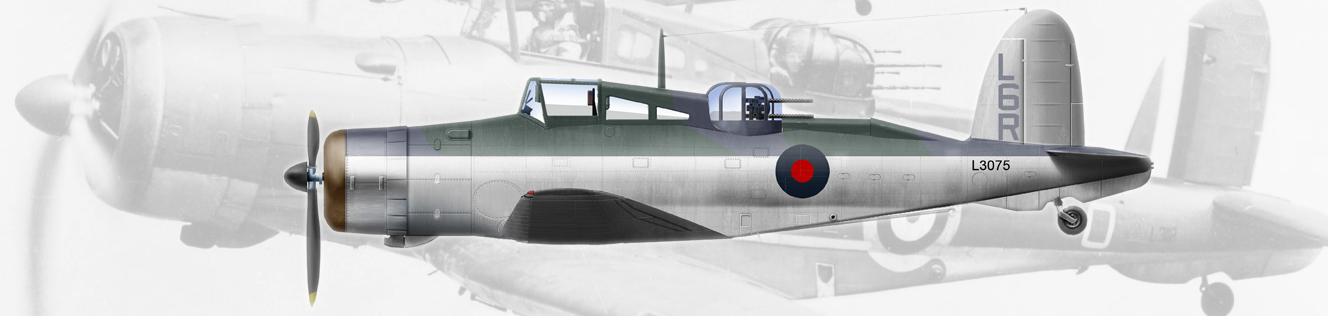

Roc I from 759 Naval Air Squadron, Donibristle Listopad, 1939

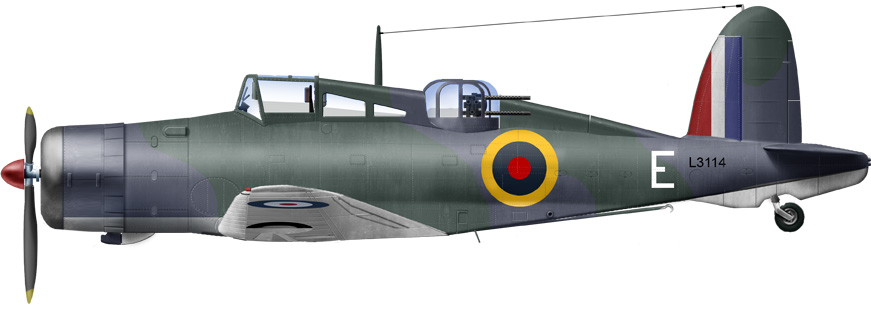

Blackburn Roc Mark I, 778 NAS, Lee-on-Solent May 1940

Marck I 806 NAS Haston Airbase Orkney, April 1940

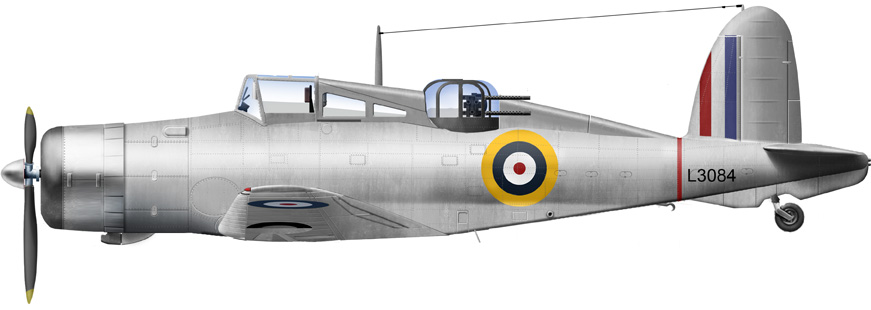

Roc I, Dyce Air Base, Scotland 1940

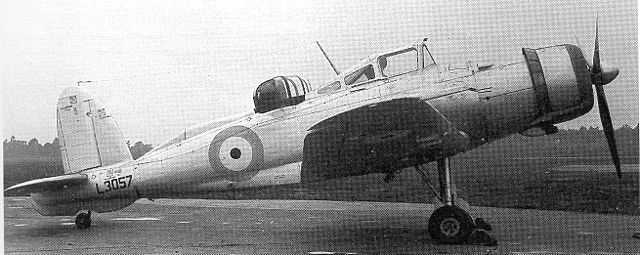

Additional photos

Videos

Ed Nash take on the Roc

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign