Category: War of 1898

USS Charleston (1888)

Protected Cruiser (1888) USS Charleston (C-2) was the second British-designed cruiser (after Baltimore) in the early years of the “new…

Emperador Carlos V

Armada (1895-1932) Emperador Carlos V was an armored cruiser of the Armada (Spanish Navy) in service from 1898 to 1933….

USS Iowa (1896)

USA (1893): Pre-dreadnought Battleship BB-4 1895-1923 USS Iowa marked an improvement over the previous Indiana-class with better seaworthiness due to…

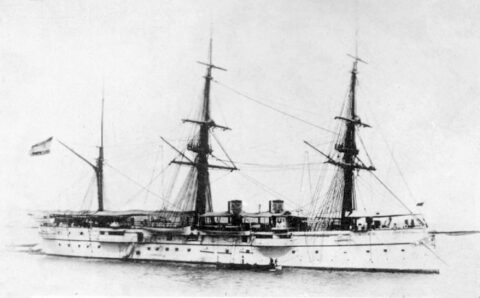

Velasco class cruisers

Armada (1880-1927): Velasco, Gravina, Infanta Isabel, Isabel II, Cristóbal Colón, Don Juan de Austria, Don Antonio de Ulloa, Conde del…

Aragon class cruisers (1879)

Armada (1880-1905): Aragón, Navarra, Castilla The Aragon class were three unprotected wooden-built cruisers between 1869 and 1882 for the Spanish…

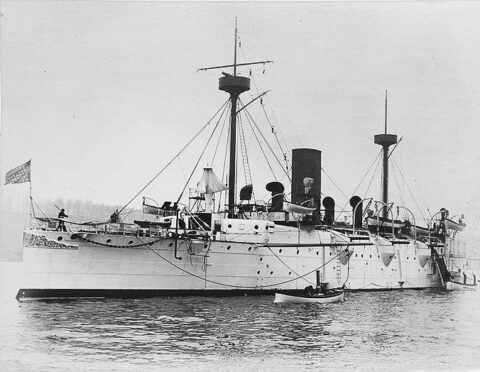

USS Maine (1889)

USA – Armoured Cruiser 1888-1898 USS Maine was the first USN armoured cruiser made famous by the war she indirectly…

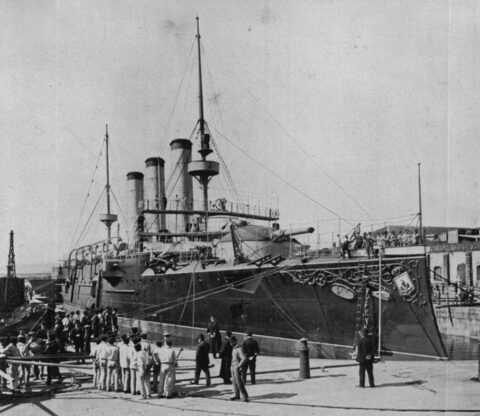

Infanta Maria Teresa class cruisers (1890)

Spanish Armada (1888-1898): Armoured Cruisers Infanta Maria Teresa, Vizcaya, Almirante Oquendo If it is a dubious privilege to have three…

Cristóbal Colón (1896)

Cristóbal Colón (1896) Spanish Armada (1894-1898): Armoured Cruiser The Spanish armored cruiser Cristóbal Colón was a warship that was built…

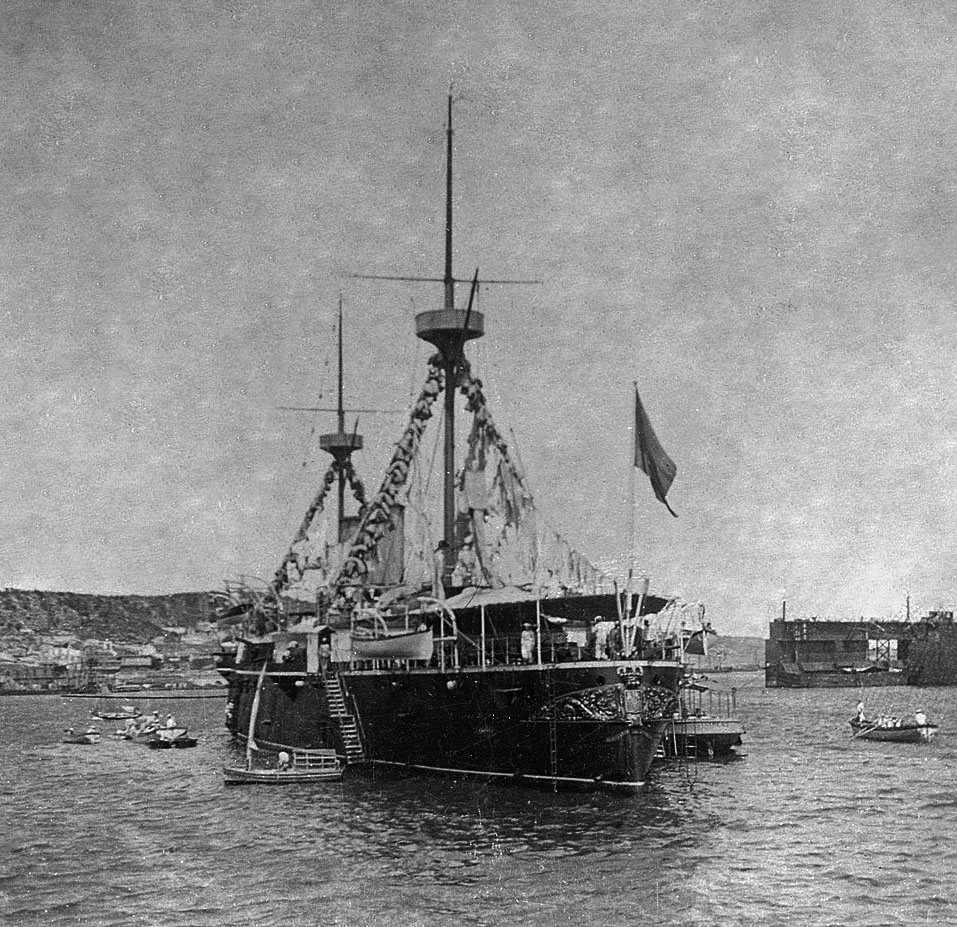

Pelayo (1887)

Spanish pre-dreadnought Battleship (1885-1929) Pelayo was a French-built Battleship, first modern one in service with the Armada. A fitting subject…

USS Olympia

US Protected Cruiser, 1890 – today Introduction: The birth of the “new navy” When the first Cleveland Administration took office…

dbodesign

dbodesign