Category: Chinese warships

Fu Po class transport sloops (1870)

Fu Po class cruisers (1870) Imperial Ming Navy – Transport Gunboats Fu Po was the lead ship of six armed…

Ning hai class cruisers (1931)

Ning Hai class cruisers (1931) Chinese Republic – Ning Hai, Ping Hai The Last Chinese Cruisers The Ning Hai class…

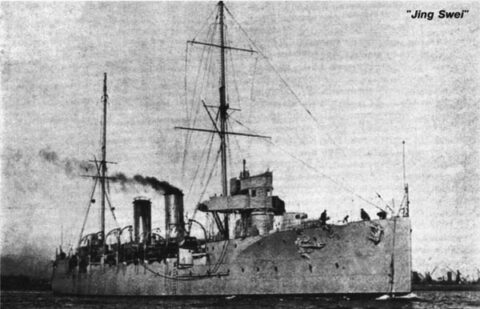

Chao Ho class cruisers

Chao Ho class cruisers (1911) Chinese Empire – Chao Ho, Ying Swei, Fei Hung Training cruisers to Brit-US Yards The…

Chao Yung (Chaoyong) class protected cruisers (1880)

Chao Yung (Chaoyong) class protected cruisers (1880) Chinese Empire – Chao Yung, Yang Wei The oldest Chinese protected cruisers –…

Hai Tien class protected cruisers (1898)

Hai Tien class protected cruisers (1898) Chinese Empire/Republic – Hai Tien, Hai Chi (1898) The largest Chinese cruisers in 1900…

Hai Yung class protected cruisers (1897)

Hai Yung class protected cruisers (1897) Chinese Beiyang Fleet – Hai Yung, Hai Chou, Hai Chen The Chinese German-built cruisers…

Dingyuan class ironclads (1881)

Dingyuan class ironclads (1881) Chinese Beiyang Fleet The first and last Chinese battleships The present ironclads had many names, in…

Pao Min (1885)

Pao Min (1885) Chinese Nanyang Fleet One of the forgotten gunboat-size Chinese cruisers – In 1880 the concept of cruiser…

dbodesign

dbodesign