Germany: SM U9, U10, U11, U12 (1910-1911)

Germany: SM U9, U10, U11, U12 (1910-1911)WW1 German U-Boats

Brandtaucher | Forelle | U-1 | U-2 | U-3 class | U-5 class | U-9 class | U-13 class | U-17 class | U-19 class | U-23 class | U-43 class | U-57 class | U-63 class | U-87 class | U-93 class | U-139 class | U-142 class | UA | UB-I class | UB-II class | UB-III class | UC-I class | UC-II class | UC-III | Deutschland | UE-I class | UE-II class | U-Projects

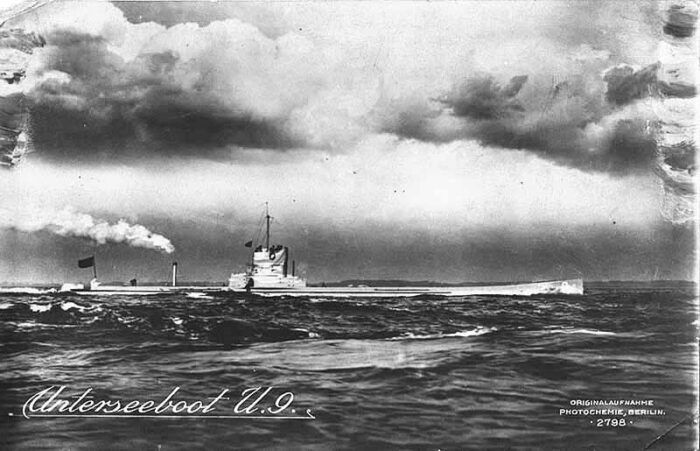

The U9 was the first in a series of four submersibles built at Danzig and closely derived from the U5. Their length was unchanged, but their width was increased by 40 cm while their draft was 50 cm lower. Their surface speed was increased from 13.4 to 14.2 knots, while their underwater speed was 8 knots.

Their engine power was greater, but their fuel oil supply was reduced by two tons and their autonomy, with a superior displacement, regained 100 nautical miles on the surface. These four units were heavily committed in action, only U9 surviving the war. The U10 hit on a mine in May 1916, U11 on December 9, 1914, and U12 was rammed by HMS Ariel on March 10, 1915.

Development

U-9 was a double-hulled boat designed as ocean-going vessel in official papers, and for these, the torpedo inspectorate planned a minimum surface speed of 15 knots and a submerged speed of 10.5 knots, which were never achieved. After the U5 class they were yet another attempt to gradually improved their characteristics and looked more appealing for fleet operations. The Torpedo Inspectorate also asked for a range of at least 2,000 nautical miles. The goal was in case of war to exit the Skagerrak or joint any point around the British isles and mid-atlantic. They had a fixed-pitch propeller as well as large-surface batteries, plus an air purification system, the first to be installed.

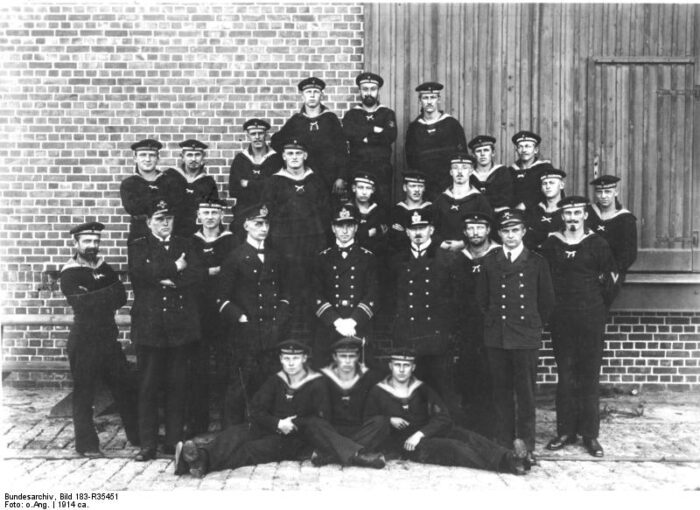

U-9 was commissioned as the first boat in class by July 15, 1908, with her keel laid at the Imperial Shipyard in Danzig. Commissioned on April 18, 1910, she had two famous commanders. The first was Lieutenant Commander Waldemar Kophamel, a future well known WW2 U-Boat ace. On 16 July 1914, her crew made an underwater torpedo reloading, the first time ever on a German submarine. This open the possibility of more torpedoes in reserve and prolongated operations. To compare, the U5 class also six torpedo total, but their spares were located at a point which forbade anything but calm seas for a surface reloading.

So in size, range, speed and capabilities in general, the U9 class (U9 to U12) were a great step forward. Their successors, U13 and U16 classes were derived from the U9.

Design of Project 13

Hull and general design

U-9 and her siblings had an overall length of 57.38 m (188 ft 3 in). The pressure hull was 48 m (157 ft 6 in) long. Their beam was 6 m (19 ft 8 in) (o/a) and the the pressure hull diameter was 3.65 m (12 ft). Draught was 3.13 m (10 ft 3 in) and total height 7.05 m (23 ft 2 in). Displacement was greater than the U9 class at 493 t (485 long tons) surfaced and 611 t (601 long tons) submerged. Their complement comprised 4 officers and 31 enlisted.

Powerplant

U-9 was given the same arrangement as previous boats, only more capable. There were two Körting 8-cylinder and two Körting 6-cylinder two-stroke petrol engines which combined, produced a total of 1,000 metric horsepower (735 kW; 986 bhp) for surface-running. U9 and sisters also could dive within 50–90 seconds.

Underwater, these boats depended on two Siemens-Schuckert double-acting electric motors and two electric motors for a total of 1,160 PS (853 kW; 1,144 shp). This power was passed onto two shafts via a gearbox and clutches, and the propeller measured 1.45 m (4.8 ft) in in diameter for a top surface speed of 14.2 knots (26.3 km/h; 16.3 mph).

Underwater they were still capable of 8.1 knots (15.0 km/h; 9.3 mph). These were remarkable performances for the time. Many WW2 submarines were no better. Cruising range was 1,800 nautical miles (3,300 km; 2,100 mi) which was also far more generous than previous boats, at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) surfaced and still 80 nmi (150 km; 92 mi) at 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph) underwater. They could dive below 50 m (164 ft 1 in) which seemed sufficient for the time.

Armament

The U9 class came armed with four 50 cm (20 in) torpedo tubes, with two in the bow and two in the stern, all reloadable in the pressure hull. With them came 6 torpedoes, including four pre-loaded and two spare in the forward torpedo room. The initial deck armament only comprised a machine gun, but they were equipped with a 3.7 cm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss gun in 1914. In 1915, they were fitted with an additional 5 cm (2.0 in) gun. U-9 from 1916 had two mine-laying rails installed for tests to convert these old boas into minelayers, but this was not a success and the rails were removed.

Torpedo Tubes

The four 450 mm (17.7 inches) torpedo tubes could be reloaded from above via the larger hatches described above, and these were the 45 cm (17.7″) C/06 of 1907, 1,704 lbs. (773 kg) for 222 in (5.650 m) in lenght, carrying a warhead of 270 lbs. (122.6 kg) TNT to 1,640 yards (1,500 m) at 34.5 knots or 3,380 yards (3,000 m) at 26 knots due to her Brotherhood system. More on navweaps

3.7cm/27 L/30 Hotchkiss Gun

Originally thes eboats had a 7.9mm/79 Maxim machine gun installed on a pintle aft of the CT until 1914.

The new Hotchkiss L/30 was installed by late 1914.

It was manufactured under licence by the Gruson company, named ‘3.7 cm Revolver Kanone Hotchkiss – Gruson’.

Weight 571 kg, 32.20mm (total tube length), 20 rifled part, 12x grooves 6 degrees angle

Projectile weight: 0.63 kg HE or 0.64 kg shrapnel, mv 494 m/s

Fire rate 32-50 rpm, range 2000 m HE, +18 degrees elevation.

5cm/37 SK L/40 C/92 Gun

Installed on U9 to U12 from 1915.

Designed in 1892 but produced as the 5 cm SK L/40 (2 inches) first and replaced by the 5 cm Tbts KL/40 in 1913.

It weight 240 kg (530 lb), for 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long, 1.83 m (6 ft) barrel.

It fired a Fixed QF 52 x 333R 1.75 kg (3.9 lb) HE shell at 656 m/s (2,150 ft/s)

The Breech was of the Horizontal sliding-wedge type for a rate of fire of 10 rpm

Elevation was -5° to +20°, traverse 360° with a single gunner, and two loaders.

Maximum firing range was 6.2 km (3.9 mi) at +20°. This was considered a defensive gun only, as the round had little power.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 505t surfaced, 636t submerged |

| Dimensions | 57.30 x 5.60 x 3.55 m (188 ft x 18 ft 4 in x 11 ft 8 in) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Körting 6-cyl. 2 stroke kerosene, 900 PS, 2× EM 1,030 shp |

| Speed | 13.4 kts surfaced/10.2 knots submerged |

| Range | 3,300 nmi (6,100 km; 3,800 mi)/9 kts/55 nmi at 4.5 kts |

| Armament | 4× TTs (2 bow, 2 stern), 6x 45 cm (18 in) torpedoes, 3.7 cm (2 in) SK L/40 gun |

| Max depth | 30 m (98 ft) |

| Crew | 4 officers + 24 men |

Career of the U3 class

U9

U9

U9 was ordered on 15 July 1908, laid down at Kaiserliche Werft, Danzig and was launched on 22 February 1910, commissioned on 18 April 1910. U9 became instantly in Germany the best U-Boat of the war interms of military kills. She undertook seven patrols, sank five warships for a total tonnage of 44,173 tons and 13 merchant ships with 8,636 GRT. Other sources gives 20 patrols, 13 ships for 8,636 GRT.

On 20 September 1914 she left Heligoland for a reconnaissance mission and on the 22th under command of Lieutenant Commander Otto Weddigen, she spotted and famously sank three British armored cruisers, HMS Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy one after the other, 50 km north of Hook of Holland. Each cruiser stopped to come to the rescue of the one hit, not believing it could be a submarine, offering superbly static targets. Weddingten became a national hero and this became a national tragedy in Britain which put everyone still skeptical of submarines, painfully aware of their potential. As far as submarine warfare goes, this event was pivotal in history at large. On her next patrol, she still sank under Weddingen the British protected cruiser Hawke off Aberdeen, on October 15.

On 20 September 1914 she left Heligoland for a reconnaissance mission and on the 22th under command of Lieutenant Commander Otto Weddigen, she spotted and famously sank three British armored cruisers, HMS Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy one after the other, 50 km north of Hook of Holland. Each cruiser stopped to come to the rescue of the one hit, not believing it could be a submarine, offering superbly static targets. Weddingten became a national hero and this became a national tragedy in Britain which put everyone still skeptical of submarines, painfully aware of their potential. As far as submarine warfare goes, this event was pivotal in history at large. On her next patrol, she still sank under Weddingen the British protected cruiser Hawke off Aberdeen, on October 15.

On January 12, 1915, it’s former First Watch Officer Johannes Spieß that succeeded to Weddigen as commander. She also sank six British fishing trawlers and the British transport Queen Wilhelmina (3,590 GRT) in 1915. His boat was transferred to the Baltic and converted into a minelayer for a time. On August 16 she sank the British steamer Serbino near Worms island. On November 5 she sank a Russian minesweeper. Spieß remained in command until April 19, 1916, and U9 was used for training in Kiel until Nov. 1918. On the 26th she was delivered to Great Britain, scrapped in Morecambe, Lancashire, in 1919.

Sunk Ships (Selection). Thanks to Weddigen and his crew, U9 was given for the first time the right to display the Iron Cross on its conning tower. Apart from her, only SMS Emden received this honor in WWI. Iron crosses painted on the CT however became more common in WW2.

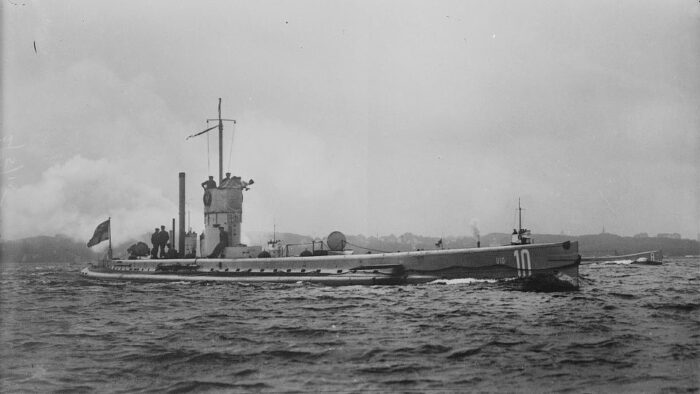

U10

U10

U-10 was launched on 24 January 1911 at the Imperial Shipyard in Danzig, commissioned on 31 August 1911 under command of Lieutenant Fritz Stuhr. For her six combat patrols, she sank 1,625 GRT. On March 31, 1915, she sank the Norwegian sailing ship Nor. On April 1, 5, and 28, 1915, she sank the British fishing boats Gloxinia, Jason, Acantha, and Lilydale. On November 6, 1915, she sank the Finnish passenger steamer and transport Birgit. By May 27, 1916, under Lt. Cdr Fritz Stuhr, she left Libau for the north of Gotland and her trace is lost afterward. She was reported overdue, never heard of again. It is presumed now that all 29 crew members were lost in the Gulf of Finland in June 1916, either due to a collision with a mine or human error or technical issue. The wreck remained undiscovered.

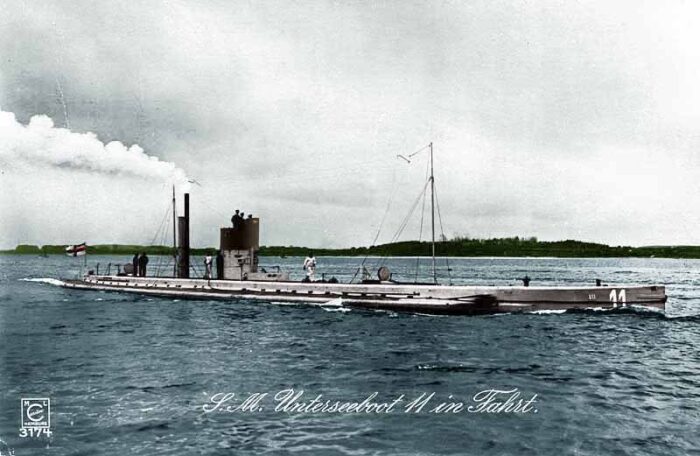

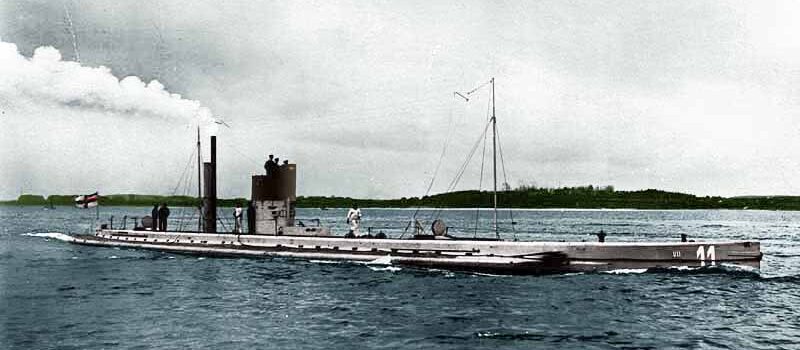

U11

U11

U-11 was launched on April 2, 1910, at the Imperial Shipyard in Danzig, commissioned on September 21, 1910, under first commander, Lieutenant Walter Forstmann. She carried out only two combat patrols and no ships were sunk. On December 9, 1914, U 11 departed Zeebrugge on a patrol in the channel and North Sea. Her whereabouts after this are unknown. She was reported overdue. Probable cause today is likely a collision with a mine from a British barrage, with 29 crew members, including the commander, Kapitänleutnant Ferdinand von Suchodoletz. The wreck was later found in the Strait of Dover, studied but not raised. The cause of the loss remains murky.

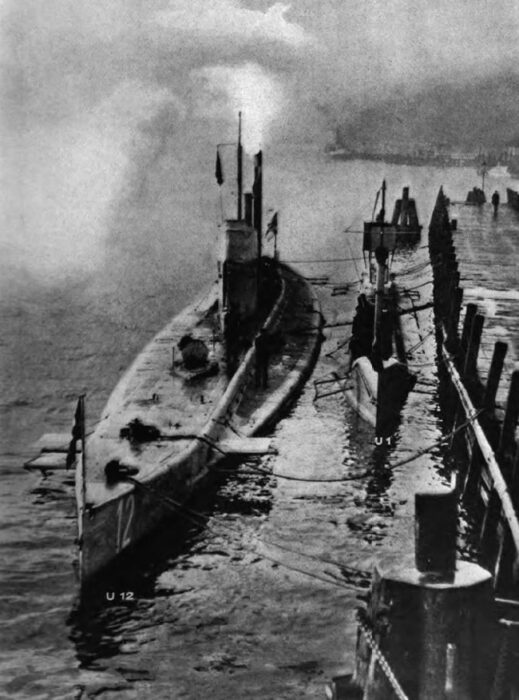

U12

U12

U 12 was launched on May 6, 1910, at the Imperial Shipyard in Danzig, commissioned on August 13, 1911, under Lieutenant Commander Claus Rücker. She carried out four patrols in 1914 and 1915, sinking two ships for a total of 1,815 GRT. According to other sources, two patrols with a merchant ship of 3,738 GRT and a warship of 820 tons: The British minesweeper Niger on November 11, 1914. On March 9, 1915, she sank the British steamship Aberdon (1,009 GRT).

On March 4, 1915, U-12 departed Heligoland for her last patrol, along the British east coast.

During her time, she was used for an experiment to supply and carry on the surface a Friedrichshafen F33 seaplane as an “on board” reconnaissance asset. This was found unpractical and not repeated.

During her time, she was used for an experiment to supply and carry on the surface a Friedrichshafen F33 seaplane as an “on board” reconnaissance asset. This was found unpractical and not repeated.

On the morning of March 10, she was spotted by a British fishing vessel, near the Fife Ness lighthouse (Crail, Scotland). The fishermen called for help and three British destroyers, HMS Acheron, Ariel, and Attack were on site after an hour, spotted and fired on the U-boat. Lieutenant Kratzsch immediately ordered a dive, but Ariel was faster, ramming her at the conning tower, already damaged by at least one hit. With a downpour of seawater from the fracture CT, Kratzsch ordered to pump air into the ballasts and surface. Making his way in the Conning Tower he was immediately killed by a direct hit, while the crew armed time-delayed explosives. It seems the timing was too short for some crew members, still aboard when they detonated. Just two officers and 9 NCO and crew made it alive on 30 men, rescued by the British. The wreck of U-12 was rediscovered by Scottish divers on 13 January 2008, under 50 m, 42.5 km off Eyemouth.

Read More/Src

Books

Johannes Spieß: Sechs Jahre U-Bootfahrten. R. Hobbing, Berlin 1925.

Johannes Spieß: U-Boot-Abenteuer. 6 Jahre U-Boot-Fahrten. Verlag Tradition Kolk, Berlin 1932 Kriegsabenteuer eines U-Boot-Offiziers. Berlin 1938.

Bodo Herzog, Günter Schomaekers: Ritter der Tiefe, graue Wölfe. Die erfolgreichsten U-Bootkommandanten der Welt. 2.

Gröner, Erich; Jung, Dieter; Maass, Martin (1991). U-boats and Mine Warfare Vessels. German Warships 1815–1945. Vol. 2. Conway Maritime Press.

Rössler, Eberhard (1985). The German Submarines and Their Shipyards: Submarine Construction Until the End of the First World War. Bernard & Graefe.

Werner von Langsdorff: U-Boote am Feind. 45 deutsche U-Boot-Fahrer erzählen. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1937.

Carl Ludwig Panknin: Unterseeboot „U. 3“. Verlagshaus für Volksliteratur und Kunst, Berlin 1911

Unterseeboot „U. 9“. Schiffe Menschen Schicksale.

Bodo Herzog: Deutsche U-Boote 1906–1966. Erlangen: Karl Müller Verlag, 1993

Eberhard Möller/Werner Brack: Enzyklopädie deutscher U-Boote Von 1904 bis zur Gegenwart, Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2002

Ulf Kaack: Die deutschen U-Boote Die komplette Geschichte, GeraMond Verlag GmbH, München 2020

Robert Hutchinson: Kampf unter Wasser – Unterseeboote von 1776 bis heute, Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2006

Links

en.wikipedia.org SM_U-9

uboat.net/ types U9

uboat.net/ commanders PLM Weddingen

uboat.net commanders/ PLM Speis

worldwar1.co.uk/cressy.htm

uboat.net/ successes u9

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign