Submarine-carried Seaplane (1922), 4 made.

Submarine-carried Seaplane (1922), 4 made.

The Caspar U.1 (in some publications Caspar-Heinkel U.1) was a 1922 German patrol seaplane tailored for use on board a submarine.

It was the world’s first of its kind, tailor designed by Ernst Heinkel and built by Caspar-Werke.

The U.1 was indeed designed to fit inside a cylindrical container carried and then launched from a submarine to solve the issue of reconnaissance.

A U-boat standed quite low over the water and often had its visual horizon quite limited.

A seaplane was for this an excellent spotted. The idea was alredy tested in WWI on many U-Boat with a regular seaplane simply carried on deck and launched when needed.

To fit stringent requirements, the Caspar U1 was a really small aircraft, unarmed and compact enough, when dismounted, to fit inside a 1.70 m diameter tube. Tests were performed at the a time the Reichsmarine was forbidden to have submarines.

The USN was interested as it looked for its own cruiser submarine to have up to seven seaplanes, and they were tested as NAS Anacostia in 1922.

Overall, the concept was not resurrected by the Kriegsmarine, but tested by UK, France and in particular Japan, which developed a whole family around the idea in the interwar and WW2.

U-Boats however in #WW2 had a more practical Fa 330 kite, used by U-177, U-181, and U-852. https://naval-encyclopedia.com/naval-aviation/ww2/germany/caspar-u1.php #caspar #heinkel #floatplane #reichsmarine

U1 tested by the USN

Development

In 1920, despite the new Reichsmarine was forbidden to have submarines, nothing prevented the development of aviation (if unarmed) or ships. Many in the naval staff were sure that one day the Versailles treaty would be amended or abrogated, and already planned for future submarines. Not to loose any skills, a clandestine design bureau was established in the Netherlands, producing designs to be built by other nations, and keeping its engineering skills while preparing the first generation of 1930s submersibles. With the mostly positive experience of cruiser submarines (“U-Kreuzer”), with a trans-oceanic range and heavy guns, it was planned to at least test the feasability of a submarine-carried observation seaplane. Heinkel was entrusted this project and started working in 1921.

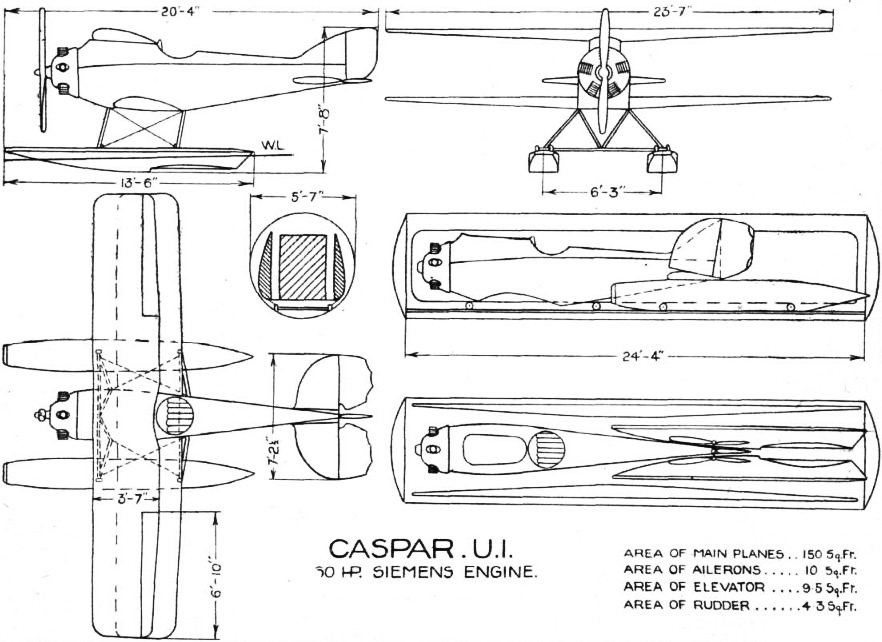

The U.1 was designed to meet a stringen requirement, to fit inside a cylindrical container no more 7.40 metres (24.3 ft) long for a diameter of 1.70 m (5 ft 7 in), for a short man to barely stand inside. It was believed such container was not to create too much water resistance and still allow a reaslitically viable aircraft to be assembled and flown, with floats to land at sea when its mission was completed, dismounted and fit inside the container. Nothing in the Versailles treaty forbade such tests, albeit they were not adverstised.

The assembly was to be performed by a small company out of scrutiny by the allied commission, Caspar, a relatively unknown workshop. Karl Caspar founded his first company, “Zentrale für Aviatik” back in 1911, and so gained valuable experience. His company manufactured aircraft from Etrich and Rumpler under license as well as parts. In the First World War, it ceased operations, was “buried” and re-established by 1921 in Travemünde under the name “Hanseatische Flugzeugwerke Karl Caspar AG”. It was changed later to Caspar-Werke AG in 1924. Officially it was manufacturing parts for others companies, all unarmed aircraft.

At the time, the company’s chief designer was no less than a young Ernst Heinkel (1888–1958). In WWI he co-developed with Robert Thelen the B.II for Albatros in 1914. Albatros was one of the most prominent German aircraft manufacturer of the time with Fokker. The B.II was used notably by the Kaiserliche Marine. He however left Albatros, and joined Hansa-Brandenburg by late 1914 and started working on seaplanes. He stayed with the company until 1918. In 1921 he was back in business, appointed as head designer of Caspar-Werke. He worked on the U.1 but soon left after a dispute over ownership of a design and by 1922 established Heinkel-Flugzeugwerke at Warnemünde, specialized in civilian seaplane designs licence-built in Sweden as well as catapult-launched seaplanes for the IJN. One ended on the ocean liner Bremen, for launching mail planes.

Back to 1921 and Caspar AG. The company manufactured small series of civilian sport planes for rich amateurs: The CC15 and CST18 remained projects, but the C24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 33 and 35 all received a few orders. The last, the C.28 Priwall was a single engine transport biplane. None reach true production and they remained confidential. The C32 (4 built) was for example an agricultural biplane. The C30 was a reconnaissance model never adopted as the C27, a training seaplane. All but the C32 were prototype aircraft. But all the way back after the company was created, Heinkel’s first project became the the single-seat reconnaissance floatplane Caspar U.1 (or Caspar-Heinkel U.1 to separate it from later designs). It was made very small for its intended role.

Design

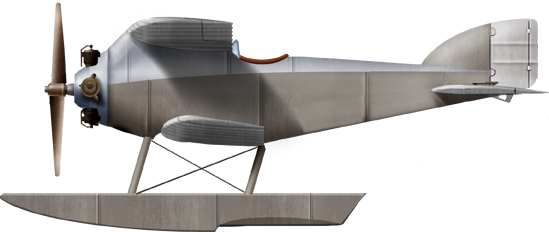

Heinkel signed with this model, the sole he made for Caspar, a very odd-looking and very small aircraft, yet very practical. The most striking aspects were the placement of the wings and their connection: To reduce the time to launch the aircraft, it was built as a “cantilever biplane”, remove rigging and struts or wires to assemble. The upper wing was attached to the wooden fuselage with the pilot seated behind. He had a small windshield and could see above the wing, but visbility below was mediocre at best. The wings were indeed staggered, with the low wing a bit further aft.

Heinkel signed with this model, the sole he made for Caspar, a very odd-looking and very small aircraft, yet very practical. The most striking aspects were the placement of the wings and their connection: To reduce the time to launch the aircraft, it was built as a “cantilever biplane”, remove rigging and struts or wires to assemble. The upper wing was attached to the wooden fuselage with the pilot seated behind. He had a small windshield and could see above the wing, but visbility below was mediocre at best. The wings were indeed staggered, with the low wing a bit further aft.

It was not overly compact at 6.20 m overall, some civilian models were smaller, and the wingspan was appropriated to its engine for reasonable lift and endurance at 7.80 m (25 ft 7 in). The ratio however still favored agility and speed over altitude. Notably given its small engine, it had less drag than conventional aircraft with struts and wires, apart for the two single-step floats, attached by folding W style strut assemblies, locked in place when unfolded. The wings were rectangular, unclutched from the fuselage and folded along the sides when dismounted. The tail unit had a classic style with low-mounted rounded tail surfaces that folded on themselves in a way not to create too much height.

The engine was a front-mounted 55-horsepower (41 kW) Siemens Sh4 radial piston engine. It was at the time used by civilian models, sport planes, but unfir for militar service (1918 fighter had 150+ hp engines. The cylinders were air-cooled, protruding from a conical metallic nose. There was of course a fixed-pitch wooden two-bladed propeller, also dismounted. Thes wings used classic wooden framing construction wrapped in doped fabric, with metal longerons and internal beams, but othrwise not much is known about details of the construction. The floats were also likely wooden made, as their struts, with internal steel beams. Having no struts not bracing between wings, the way the wings were locked on the upper fuselage was the obkect of much strenghtening as well as fastening the wings together.

Specifications Caspar U-1 |

|

| Crew: | 1 pilot |

| Lenght | 6.20 m (20 ft 4 in) |

| Wingspan | 7.80 m (25 ft 7 in) |

| Height | 2.34 m (7 ft 8 in) |

| Wing area | 14 m2 (150 sq ft) |

| Empty weight | 360 kg (794 lb) |

| Max TO Weight | 510 kg (1,124 lb) |

| Propulsion | Siemens 5-cyl. radial: 37 kW (50 hp) |

| Propeller | 2-bladed fixed pitch wooden |

| Top speed | 145 km/h (90 mph, 78 kn) |

| Cruise speed | 121 km/h (75 mph, 65 kn) |

| Service ceiling | 3000 m |

| Rate of climb | 7 mins to 1,000 m (3,300 ft) |

| Range | 360 km |

| Landing speed | 75 km/h (47 mph; 40 kn) |

| Armament | None |

The Caspar U2

The Caspar U 2 was an improved model, slightly shorter at 6.18 m, more compact for its wingspan at 7.20 m but a bit taller at 2.59 m. Its Empty weight was 345 kg, so less than the U1, for a useful payload of 41 kg in addition ro the pilot and gasoline. Its takeoff was “only” of 510 kg and its speed, given the engine was the same, was the same, 145 km/h near the ground. In general performances it was capable of 142 km/h at 1000 m altitude, 138 km/h at 2 km and 134 km/h at 3 km with a cruise speed of 130 km/h.

As for the previous model the landing speed is unknown. Climb time was slightly better at 6 min to 1000 m. It also took up to 15:34 min to 2000 m and 34:52 min to 3000 m.

Range was inferior though, at 250 km with a service ceiling of 3000 m. Powered, instead of the Siemens & Halske Sh 4 air-cooled seven-cylinder radial rotary engine by the more common Oberursel U 0 (a clone of the French Gnome). Rated power was better for the even more compactness at 62 hp (46 kW) and it even developed 84 hp (62 kW) on the ground.

Fate

The U.1 (id D-293) was designed over a few months in 1921 and built covertly. To avoid scutiny, components were indeed built in different locations in Germany, then smuggled abroad and assembled at the former Fokker assembly site now occupied by Caspar at Travemunde and at the Swedish Svenska Aero, established by Heinlel and Brickner at Lidingo in 1921. There were built the rudders and pontoons. Final assembly was performed at Caspar werke.

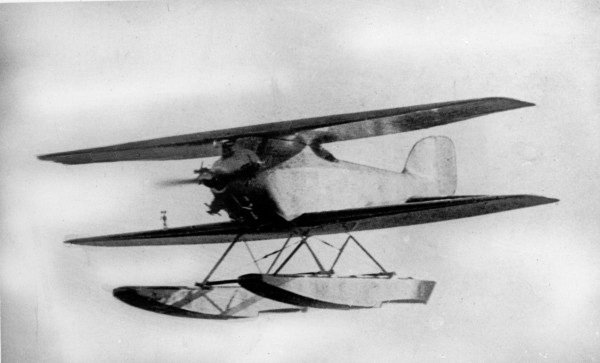

The U.1 eventually made its maiden flight in 1922, effectively becoming the first ever military aircraft developed by Germany after the capitulation in World War I, in addition of being a model officially for submarines. The model was showcased to a few officials retired from the Navy as the Reichsmarine was still not created at the time. It showed it could be easily disassembled and folded into the designated container. During testing, it was also mounted by just four men in a few minutes after removing it from the container.

The audience appreciated the concept, but since the Versailles treaty forbidden submarines, this went no further, no official order was of course given, but at least the idea was tested. It was not perfect though. It was estimated it took too long, not to mount and launch in just 1 minute 3 seconds*, but to dismount and fit it in the container in case of an encounter with enemy ASW vessels. In that case it was theorized to just save the pilot and ditch the plane to submerge.

*this time was in fact inferior to the diving time of a large “U-Kreuzer”.

These tests were reported however in Germany by Christiansen, which followed Heinkel, and forwarded his tests and ideas to the USN staff. Indeed, on the other side of the Atlantic, there were serious projects of cruiser submarines, just as negociations for a disarmament treaty (the future Washington treaty) started. Having no use for the Caspar U.1, approval for export to the US was granted at a tilme there was still no strict regulations in place (albeit the Armistice and Peace Treaty provisions prevented this on paper), and the two prototypes, A6434 and A6435 were sold to the US Navy at the end of 1922, to be tested from NAS Anacostia until 1923.

Meanwhile the model met success in Sweden, with the Swedish Navy placed orders for the Caspar S.1, later known as the Heinkel He.1 with Heinkel leeaving Caspar as seen above and assembling its models at the Swedish Naval Dockyards at Gashaga. Eventually the Caspar U.1 and S.1 were exhibited at the Gothenburg Exhibition in 1923 with the U.1 described as “designed for stowage on a submarine.” Unfortunately Sweden did not considered building cruiser submarines of its own.

Back at Caspar, a further development became he U.2 project, powered with the more powerful Oberursel U0 engine (Copy of the Gnome). Here sources differs. Some states only one was made, but most agreed there were two, sold to Japan, becoming the basis for the Yokosho Navy Type 1. Unlike the US, the IJN ran with the idea and developed several dedicated models for submarines. They even becale an integral part of their submarine warfare doctrine.

Meawnhile at Naval Air Station Anacostia, Washington, District of Columbia, in 1923, one was damaged beyond repair whilst mounted on a truck for a parade, catching trees on its way. The USN concluded the idea has merits, a fact confirmed by tests performed in Britain with M.3 and the French building the Surcouf, laid down just before the Washington treaty was adopted, banning large cruiser submarines for good. No US submarine was ever tailored to carry a seaplane. Instead focus was placed on more practical long range flying boats for Pacific operations, and a network of bases and tenders. Nevertheless, the Caspar U.1 remained an interesting footnote in both aviation and naval history, and a now largely forgotten aircraft.

Gallery

Author’s illustration

Sources

Treadwell, Terry (February 1983). “Submarine Aviation”. Naval Aviation News. 65 (2). Washington, DC: Naval Air Systems Command.

The Caspar sport seaplane”. Flight. XV (24): 315–6. 14 June 1923.

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982-1985). Orbis Publishing.

Herris, Jack (2020). German Aircraft of Minor Manufacturers in WWI: A Centennial Perspective on Great War Airplanes. Gret War Aviation Centennial Series (49). Vol. 1. Aeronaut Books.

Passingham, Malcolm (February 2000). “Les hydravions embarqués sur sous-marins” [Submarine-carried Seaplanes]. Toute l’aéronautique et son histoire (83)

Wagner, R. and Nowarra, H., German Combat Planes, Doubleday Si Co., NY, 1971

Treadwell, Terry (February 1983). “Submarine Aviation”. Naval Aviation News. 65 (2). Washington, DC: Naval Air Systems Command

Helmut Stützer. Die deutschen Militärflugzeuge 1919–1934

Flight 1923-08-02. The Caspar U.I cantilever biplane

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982-1985). Orbis Publishing.

Herris, Jack (2020). German Aircraft of Minor Manufacturers in WWI: A Centennial Perspective. Great War Aviation Centennial Series 49. Aeronaut Books.

L’Ala d’Italia 1923-05. Caspar U.I

Histaviation.com. Caspar U 1

Avions 83. Malcolm Passingham. Les hydravions embarques sur Sous-marins

Flieger Revue extra 21. Lennart Andersson. Der Starkste Uberlebt

1000aircraftphotos.com. No. 8300. Caspar U 1

airwar.ru

flyingmachines.ru

aviadejavu.ru

armedconflicts.com

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caspar_U.1

1000aircraftphotos.com

flightglobal.com archives

secretprojects.co.uk

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign